Abstract

The occurrence of bleeding following dental extraction is a relatively common complication. A history of therapy with oral anticoagulants represents a major favoring factor, both in patients treated with vitamin K-antagonists (especially warfarin) and with direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs). Several local hemostatic measures can be applied to limit the bleeding risk in these patients. The aim of this systematic review is to evaluate what measures can be adopted to limit the bleeding risk following dental extractions in patients treated with oral anticoagulants. A literature search was performed, and 116 articles were retrieved. Titles and abstract analyses excluded 91 articles, and three more articles were excluded following full-text analysis. The systematic review was performed on 22 articles. Among the included articles, 20 studies reported on patients treated with warfarin, and two studies on patients treated with DOACs. The agents employed included local intra-alveolar agents, tranexamic acid, and PRF. The included studies were all at moderate/high risk of bias. Moreover, limited evidence is available on hemostasis in patients treated with DOACs. The available evidence hinders stating the superiority of one agent over the others. Further research is advised to increase the level of evidence of the application of hemostatic agents in patients treated with oral anticoagulants.

1. Introduction

Dental extractions are the most common procedures performed in routine dental practice. Bleeding and oozing from the surgical wound are frequently encountered, and mostly self-limiting, complications [1]. However, in patients treated with vitamin K antagonists or direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs), additional measures may be required to manage and limit the risk of post-operative bleeding [1].

Vitamin K antagonists include coumarin and its derivatives such as warfarin. Their mechanism of action is based on the inhibition of prothrombin and clotting factors formation. Dose adjustments are often required in order to maintain the target International Normalized Ratio (INR) of 2.5 (therapeutic range 2–3) [2]. To date, warfarin is the most prescribed oral anticoagulant for the management of thromboembolic disorders, despite its narrow therapeutic index and the high variability in clinical response [3,4].

DOACs have been introduced in recent years for the management of several cardiovascular conditions, including treatment of venous thromboembolism, stroke prevention in non-valvular atrial fibrillation, and for thromboprophylaxis following orthopedic surgery [5]. The DOACs category includes four anticoagulants which directly inhibit the coagulation cascade. Dabigatran is a direct thrombin inhibitor, while apixaban, rivaroxaban, and edoxaban exert their pharmacological activity by inhibiting factor Xa [5]. DOACs are becoming increasingly used with respect to vitamin K antagonists due to their efficacy and safety [6]. It appears that a reduced risk of bleeding can be observed in patients treated with DOACs compared with warfarin as a therapeutic regimen, although in some cases monitoring is still advised [7].

Patients under oral anticoagulant therapy are more prone to bleeding complications and hematoma formation following dental procedures. Tooth extractions are the most frequently performed oral surgical procedures, and bleeding or oozing are frequently occurring complications [8,9]. The surgical trauma on both hard and soft tissues can be related to the development of post-extraction bleeding, although inflammation and/or infection of the extraction site can be concurrent factors [10]. In patients treated with oral anticoagulants, the bleeding risk is enhanced; therefore, different recommendations have been proposed, including anticoagulant therapy modulation through reduction, suspension, or bridging [11]. However, it has also been suggested that therapy discontinuation may expose the patient to a higher risk of thromboembolism against a modest risk of hemorrhage in patients with an INR within the therapeutic range [12].

At present, several hemostatic agents find application for the management of post-extractive bleeding in patients treated with oral anticoagulants. The aim of the present systematic review was to analyze the hemostatic agents employed to manage the bleeding risk associated with dental extraction procedures in patients undergoing oral anticoagulant therapy with vitamin K antagonists and DOACs.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Protocol and Eligibility Criteria

The study protocol was prepared following the Preferred Reporting Items Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses Statement [13,14,15] and registered in PROSPERO (Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews).

The focused question of the present review was: “What are the hemostatic measures adopted in cases of bleeding following dental extractions in patients treated with oral anticoagulants?”

The following PICO (Patient, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome) was established for article inclusion:

- (P) Type of participants: patients treated with oral anticoagulants

- (I) Type of interventions: dental extraction, either single or multiple

- (C) Comparison between interventions: any type of hemostatic measure compared with other treatments/placebo/no treatment

- (O) Type of outcome measures: bleeding control following dental extraction.

The inclusion criteria were:

- Patients treated with oral anticoagulants

- Patients undergoing dental extractions

- One of the following study designs: observational studies, case-control studies, randomized controlled trials and interventional studies

- A minimum number of 10 participants in the study

- English language.

The exclusion criteria were:

- Patients not treated with oral anticoagulants

- Patients undergoing oral surgical interventions other than tooth extraction

- One of the following study designs: systematic reviews and review articles, case reports and case series

- Less than 10 participants in the study

- Articles not written in English.

No time limitations were set.

2.2. Literature Search

The electronic search was performed in PubMed and Scopus (SG) up to June 2022. The search strategy included a combination of MeSH terms and free text words:

((“Hemostatics” [Mesh] OR “Hemostatics/Pharmacological Action” [Mesh]) AND (“Tooth extraction” [Mesh] OR “Tooth Extraction/complications” [Mesh]) AND (“Anticoagulants” [Mesh] OR “Warfarin” [Mesh] OR “Phenprocoumon” [Mesh] OR “Acenocoumarol” [Mesh] OR “Factor Xa Inhibitors” [Mesh] OR “Rivaroxaban” OR “Apixaban” OR “Dabigatran”) AND (“Oral Surgical Procedures/complications” [Mesh] OR “Hemorrhage” [Mesh])).

The search was performed in dental journals. A hand search was performed to retrieve additional studies. Bibliographies of relevant papers were also checked. Trials databases such as clinicaltrial.gov were also searched.

2.3. Study Selection and Data Collection

Eligibility assessment was performed by two calibrated reviewers (RI and MN, κ-score > 0.8) for possible inclusion in the review in August 2022. Titles and abstracts were screened to retrieve the articles to be included in the full text analysis. In cases of unclear abstracts, full text analysis was performed to avoid exclusion of any potentially relevant article. The studies deemed suitable for inclusion following full text analysis underwent data extraction through an ad hoc extraction sheet.

2.4. Quality Analysis and Risk of Bias Assessment

Quality analysis was performed by three calibrated reviewers (RI, MN, SG). Risk of bias was assessed following the Cochrane Reviewers’ Handbook [16]. The following domains were classified as adequate, inadequate, or unclear:

- Random sequence generation

- Allocation concealment

- Blinding of participants, personnel, and outcome assessors

- Incomplete outcome data handling

- Selective outcome reporting.

2.5. Synthesis of the Results

Data were presented in evidence tables reporting study characteristics and main conclusions.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

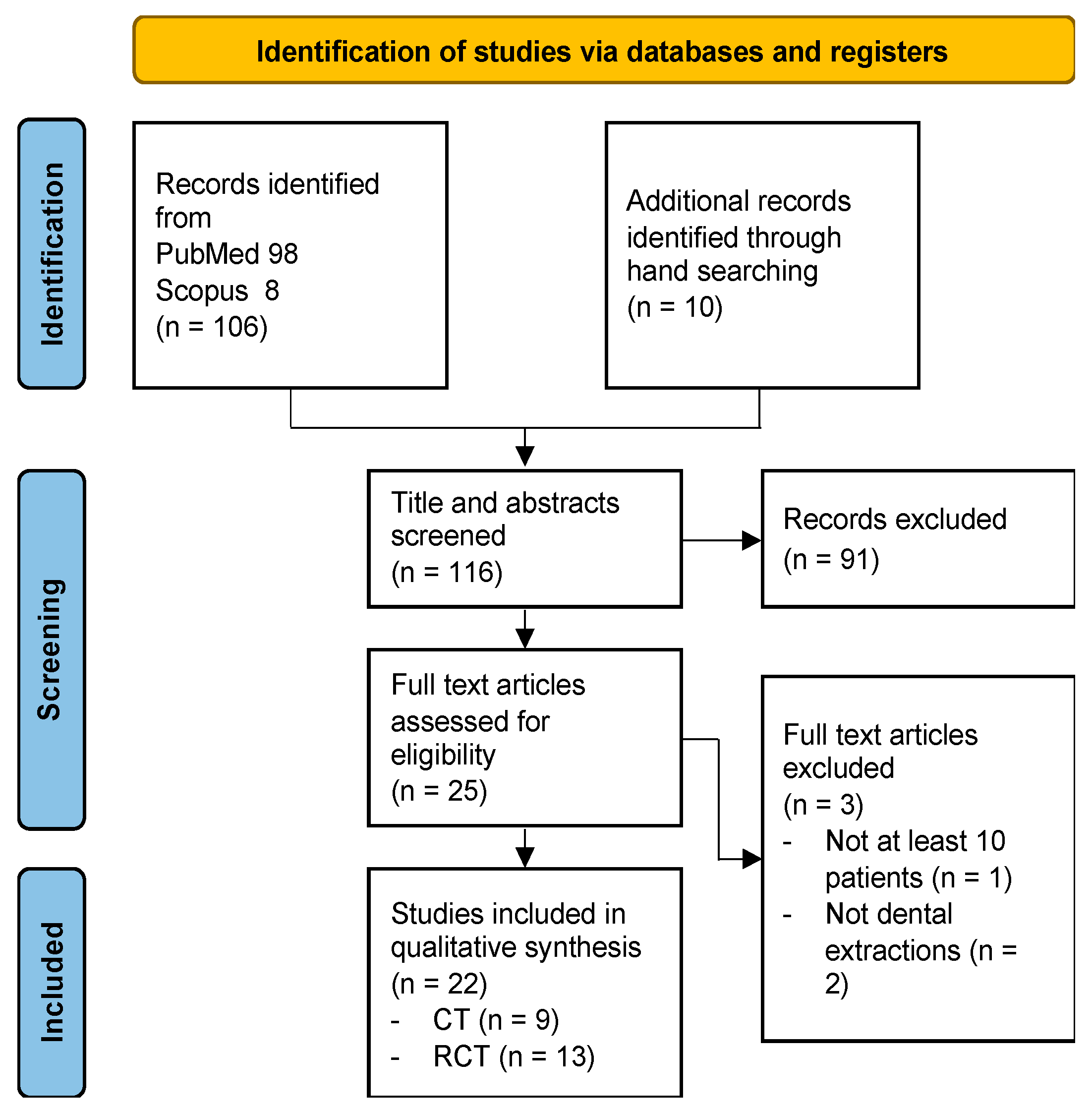

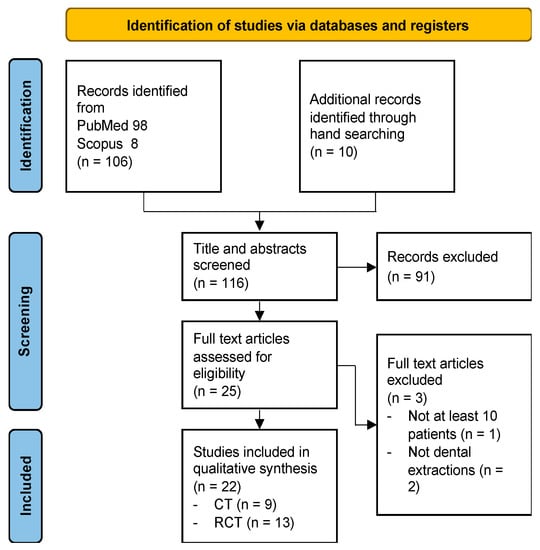

A total of 116 articles were retrieved from literature search, 106 through electronic database searching and 10 through hand searching. Following title and abstract analysis, 91 articles were excluded. The remaining 25 articles underwent full text analysis, which further excluded three articles. A final assessment was carried out on 22 articles (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Literature search flowchart according to PRISMA guidelines.

3.2. Study Characteristics

The study population consisted of 1276 subjects (43.8% females), with a mean age of 58.6 years (SD ± 11.9). The follow-up period varied from a minimum of one day to a maximum of 10 days. Twenty studies evaluated patients treated with Warfarin [17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36], and two studies involved patients treated with DOACs [37,38]. Nine articles evaluated the application of intra-alveolar agents [17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24]. Three articles employed tranexamic acid mouthwashes [25,26,38]. Three articles employed Platelet-Rich Fibrin (PRF) [27,28,37]. Seven articles compared different agents and administration methods [29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36]. Results are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of main results.

3.3. Patients Treated with Warfarin

3.3.1. Intra-Alveolar Agents

Bajkin et al. [17] compared the application of gelatin sponge without suture versus suture and gauze compression in patients treated with warfarin in the therapeutic range. Of 90 patients enrolled in total, bleeding was observed in five patients and local hemostatic measures were sufficient in cases of hemorrhage. No differences between the treatment groups were noted. Çakarer et al. [18] evaluated the effectiveness of Ankaferd blood stopper (ABS) compared with gauze compression (control group). A significant difference between the groups was reported in terms of bleeding time, which was statistically lower in the ABS group (≤1 min). Halfpenny et al. [19] compared two hemostatic intra-alveolar agents, oxidized regenerated cellulose (Surgicel), and fibrin adhesive (Beriplast P). No differences in post-operative bleeding were noted. The Surgicel group experienced higher levels of pain. Kumar et al. [20] compared HemCon dental dressing (HDD) with gauze compression. HDD presented significantly lower bleeding time and improved wound healing. Another study by Malmquist et al. [21] evaluated HDD effectiveness versus no treatment. In cases of treatment with HDD, hemostasis was achieved significantly sooner. HDD treated wounds achieved significantly improved healing. Okamoto et al. [22] investigated the application of (i) blue-violet LED irradiation, (ii) blue-violet LED irradiation and hemostatic gelatin sponge, and (iii) hemostatic gelatin sponge. The authors found a significantly higher percentage of hemostasis in the LED irradiation and hemostatic gelatin sponge group when compared with the hemostatic gelatin sponge group. No other significant differences were detected. Scarano et al. [23] evaluated the intra-alveolar application of calcium sulphate compared with obliterative suture. Bleeding frequency was significantly lower in the calcium sulphate group at days one and three post-op. No differences in healing were observed at five and seven days follow-up. Svensson et al. [24] employed absorbable hemostatic gelatin sponges or collagen fleece and sutures in patients with an INR ≤ 3.5. Of the 124 patients enrolled, five patients (4%) experienced post-op bleeding.

3.3.2. Tranexamic Acid Mouthwashes

Carter & Goss [25] compared two administration protocols of 4.8% tranexamic acid mouthwash, which was prescribed for either two or five days post-op. No statistically significant difference was observed between groups in post-op bleeding depending on the duration of tranexamic acid mouthwash treatment. Queiroz et al. [26] performed alveolar irrigation following dental extraction with either 250 mg/5 mL tranexamic acid or saline. In the tranexamic acid group, hemostasis was obtained in a significantly shorter time compared with the saline group.

3.3.3. Platelet-Rich Fibrin

Harfoush et al. [27] compared the application of PRF in the post-extractive socket versus no treatment (control group). Patients treated with PRF experienced mild (20%) or moderate (80%) bleeding, while patients in the control group showed moderate (28%) or severe (72%) bleeding. Sammartino et al. [28] employed Leukocyte- and Platelet-Rich Fibrin (L-PRF). The authors encountered hemorrhagic complications in 4% of cases, while 20% of patients showed mild post-op bleeding. The bleeding episodes were limited to the first two h post-op, in the lack of delayed bleeding episodes.

3.3.4. Comparison Studies

Al-Belasy et al. [29] compared the hemostatic effects of n-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate glue and gelatin sponge (control group). The occurrence of post-op spontaneous bleeding requiring treatment was significantly higher in the control group. No differences in wound healing were detected at 10 days follow-up. Blinder et al. [30] compared three different protocols, specifically (i) gelatin sponge and sutures, (ii) gelatin sponge, sutures, and tranexamic acid mouthwash, and (iii) fibrin glue, gelatin sponge, and sutures. Post-operative bleeding was observed in 8.6% of cases. The authors concluded that local hemostasis with resorbable gelatin sponge and sutures was sufficient in managing the bleeding risk in patients treated with oral anticoagulants. Carter et al. [31] compared the prescription of 10 mL rinse with a 4.8% tranexamic acid solution four times a day for seven days postoperatively versus intraoperative application of autologous fibrin glue. No statistically significant difference was found between the groups in terms of post-op bleeding. da Silva et al. [32] assessed the effectiveness of epsilon-aminocaproic acid administration, either as an intra-alveolar agent or as a mouthwash to be employed in the post-op period. No statistically significant difference in late bleeding was observed between the groups. Eldibany et al. [33] compared the application of intra-alveolar PRF and HDD. No statistically significant difference was found between the groups in terms of post-op bleeding. The PRF group experienced minimal pain and accelerated healing, while the HDD group presented moderate/severe pain in the first few days post-op and retarded healing. In the HDD group, the occurrence of some cases of alveolar osteitis was registered. Oberti et al. [34] evaluated the intra-alveolar application of calcium sulphate versus compression with a gauze soaked in tranexamic acid (control group). Post-operative bleeding at one-day post-op was significantly higher in the control group. At seven days post-op, there were no differences between the two groups. Pippi et al. [35] employed either HDD or hemostatic sponge as intra-alveolar agents. No statistically significant differences in bleeding time were observed between the groups. Postoperative pain was significantly lower in the HDD group than in the hemostatic sponge group. Improved healing was obtained in the HDD group in 85% of cases. Soares et al. [36] compared eight min compression with a gauze soaked in 4.8% tranexamic acid, intra-alveolar application of a fibrin sponge, and eight min compression with a dry gauze. No difference in bleeding events was observed among the groups.

3.4. Patients Treated with DOACs

3.4.1. Tranexamic Acid

Ockerman et al. [38] performed a placebo-controlled trial on the use of 10% tranexamic acid mouthwash 3-times-a-day for 3 days in patients treated with DOACs (Rivaroxaban, Apixaban, Edoxaban, Dabigatran). No differences were found between the groups in terms of post-extraction bleeding, number of bleeding events, and procedural bleeding score. Delayed bleeding and bleeding after multiple extractions showed lower occurrence in the tranexamic acid group.

3.4.2. PRF

de Almeida Barros Mourão et al. [37] employed PRF as hemostatic agents in patients treated with Rivaroxaban or Apixaban. In all cases post-op bleeding was successfully arrested by PRF in all patients. No bleeding complications were observed at 24 and 48 h post-op. No alveolar infection was detected at 7-days post-op, and favorable wound healing was observed in all patients at 10 days follow-up.

3.5. Risk of Bias in Interventional Studies

Results of risk of bias analysis are reported in Table 2. Four studies [26,35,36,38] were judged at moderate risk of bias. Eighteen studies were assigned a high risk of bias [17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,37]. None of the studies included was deemed at low risk of bias for all domains.

Table 2.

Quality analysis of the included studies. Color coding: WHITE: not applicable; YELLOW: unclear; GREEN: adequate; RED: inadequate.

4. Discussion

The issue of post-operative bleeding is gaining importance due to the high number of patients treated with oral anticoagulants. Although DOACs are becoming widely prescribed, there is still limited evidence on the hemostatic measures which could be applied in these patients. Conversely, the management of patients treated with warfarin has been extensively explored, with the adoption of various protocols for the limitation of bleeding risks.

Intra-alveolar agents appear the most effective measure for post-op bleeding prevention. In all of the studies reporting on intra-alveolar agents [17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,29,30,32,34,35], adequate hemostasis was observed, although in most cases in the absence of a statistically significant difference with control groups. This finding agrees with the recent systematic review by Moreno Drada et al. [39], as the authors concluded that no superiority could be determined for one hemostatic agent over the others. In particular, the authors highlighted that due to a high risk of bias, the certainty of the evidence was low. Moreover, no differences in terms of bleeding events and bleeding time were detected when comparing different hemostatic interventions [39]. Importantly, it should be noted that the present evidence was exclusively based on patients treated with warfarin.

The application of tranexamic acid was reported in six studies, with different administration protocols [25,26,31,34,36,38]. In all of the described cases, the application of tranexamic acid reduced the bleeding time. However, most of the studies were performed on patients treated with warfarin, and only one study [38] was performed in patients treated with DOACs. As reported in the systematic review by Engelen et al. [40], local application of tranexamic acid may prevent oral bleeding in patients treated with warfarin undergoing minor oral surgery or dental extractions. In fact, the authors found that tranexamic acid mouthwash reduced the bleeding rate following dental extractions by 25% if compared with the placebo, but there were no significant differences when compared with gauze compression or suture [40]. Consistent with previous literature, our study highlights a lack of evidence in patients treated with DOACs. Therefore, definitive conclusions could not be drawn either on the actual efficacy of antifibrinolytic therapy or the beneficial effects on patients treated with DOACs.

PRF application was reported in two studies conducted on patients taking warfarin 24, 25 and in one study on patients treated with DOACs [37]. In all of the studies, the available evidence supported the application of PRF in limiting the bleeding complications in the early post-op period, in the absence of episodes of delayed bleeding. This finding appears in contrast with the evidence from a recent systematic review by Filho et al. [41], where the authors concluded that hemorrhagic complications after dental extractions cannot be prevented with the application of PRF in patients on oral anticoagulant therapy. Moreover, no effects on pain reduction or on postoperative alveolitis development were detected in anticoagulated individuals [41].

The present study has some limitations. First, the paucity of studies evaluating patients treated with DOACs hindered the drawing of firm conclusions on this increasingly employed class of anticoagulants. Secondly, the heterogeneity in the methodologies reported in the included studies did not allow the performance of meta-analyses. Similarly, the presence of different comparative groups could also be a confounding factor. Finally, the included studies were all at moderate/high risk of bias, thus affecting reliability of the analysis.

Although the superiority of one hemostatic measure above the other cannot to date be stated in patients taking oral anticoagulants, it should be noted that such measures require further investigation even in the presence of other systemic conditions affecting coagulation capacity. Considering medication induced bleeding risk, some studies addressed the issue of antiplatelet therapy in the dental setting. Although this topic falls beyond the scope of the present review, it is important to mention how antiplatelet drugs, used alone (single antiplatelet therapy, SAPT), or in combination (dual antiplatelet therapy, DAPT) may affect clotting formation, leading to prolonged post-extraction bleeding and hemorrhagic complications [42]. Current literature reports that the use of local hemostatic agents may be sufficient in managing the bleeding risk without changing the algorithm of antiplatelet therapy [43]. From this perspective, the performance of randomized clinical trials to further assess the role of hemostatic agents following dental surgery is advised, taking into account a broader variety of systemic conditions.

5. Conclusions

The current evidence on the effectiveness of hemostatic measures appears to be still limited. Indeed, the presence of studies at moderate/high risk of bias and the paucity of studies regarding hemostasis in patients treated with DOACs hinder the possibility of drawing firm conclusions. Further research is advised to increase the level of evidence of the application of hemostatic agents in patients treated with oral anticoagulants.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.I. and M.N.; methodology, S.G. and E.C.; software, S.G.; validation, R.I., M.N. and S.G.; formal analysis, E.C. and F.G.; investigation, M.N.; resources, M.N. and S.G.; data curation, S.G.; writing—original draft preparation, M.N, E.C., S.G, F.G. and R.I.; writing—review and editing, M.N., S.G. and R.I.; visualization, F.G.; supervision, M.N., S.G. and R.I.; project administration, M.N., S.G. and R.I.; funding acquisition, M.N., S.G. and R.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Nagraj, S.K.; Prashanti, E.; Aggarwal, H.; Lingappa, A.; Muthu, M.S.; Krishanappa, S.K.K.; Hassan, H. Interventions for treating post-extraction bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 3, CD011930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeling, D.; Baglin, T.; Tait, C.; Watson, H.; Perry, D.; Baglin, C.; Kitchen, S.; Makris, M.; British Committee for Standards in Haematology. Guidelines on oral anticoagulation with warfarin—Fourth edition. Br. J. Haematol. 2011, 154, 311–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asiimwe, I.G.; Zhang, E.J.; Osanlou, R.; Jorgensen, A.L.; Pirmohamed, M. Warfarin dosing algorithms: A systematic review. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2021, 87, 1717–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.A.; Caudle, K.E.; Gong, L.; Whirl-Carrillo, M.; Stein, C.M.; Scott, S.A.; Lee, M.T.; Gage, B.F.; Kimmel, S.E.; Perera, M.A.; et al. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) guideline for pharmacogenetics-guided warfarin dosing: 2017 update. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2017, 102, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Julia, S.; James, U. Direct oral anticoagulants: A quick guide. Eur. Cardiol. 2017, 12, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almas, T.; Musheer, A.; Ejaz, A.; Niaz Shaikh, F.; Awais Paracha, A.; Raza, F.; Sarwar Khan, M.; Masood, F.; Siddiqui, F.; Raza, S.; et al. Efficacy and safety of direct oral anticoagulants with and without aspirin: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Cardiol. Heart Vasc. 2022, 40, 101016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-López, J.A.; Sterne, J.; Thom, H.; Higgins, J.; Hingorani, A.D.; Okoli, G.N.; Davies, P.A.; Bodalia, P.N.; Bryden, P.A.; Welton, N.J.; et al. Oral anticoagulants for prevention of stroke in atrial fibrillation: Systematic review, network meta-analysis, and cost effectiveness analysis. BMJ 2017, 359, j5058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Galen, K.P.; Engelen, E.T.; Mauser-Bunschoten, E.P.; van Es, R.J.; Schutgens, R.E. Antifibrinolytic therapy for preventing oral bleeding in patients with haemophilia or Von Willebrand disease undergoing minor oral surgery or dental extractions. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 12, CD011385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormick, N.J.; Moore, U.J.; Meechan, J.G.; Norouzi, M. Haemostasis. Part 2: Medications that affect haemostasis. Dent. Update 2014, 41, 395–396, 399–402, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amer, M.Z.; Mourad, S.I.; Salem, A.S.; Abdelfadil, E. Correlation between international normalized ratio values and sufficiency of two different local hemostatic measures in anticoagulated patients. Eur. J. Dent. 2014, 8, 475–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kämmerer, P.W.; Frerich, B.; Liese, J.; Schiegnitz, E.; Al-Nawas, B. Oral surgery during therapy with anticoagulants-a systematic review. Clin. Oral Investig. 2015, 19, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward, B.B.; Smith, M.H. Dentoalveolar procedures for the anticoagulated patient: Literature recommendations versus current practice. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2007, 65, 1454–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: Explanation and elaboration. BMJ 2009, 339, b2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutton, B.; Salanti, G.; Caldwell, D.M.; Chaimani, A.; Schmid, C.H.; Cameron, C.; Ioannidis, J.P.; Straus, S.; Thorlund, K.; Jansen, J.P.; et al. The PRISMA extension statement for reporting of systematic reviews incorporating network meta-analyses of health care interventions: Checklist and explanations. Ann. Intern. Med. 2015, 162, 777–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Altman, D.G.; Sterne, J.A. Assessing risk of bias in included studies. In Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Review of Interventions; Higgins, J.P., Greens, S., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009; pp. 187–235. [Google Scholar]

- Bajkin, B.V.; Selaković, S.D.; Mirković, S.M.; Šarčev, I.N.; Tadič, A.J.; Milekič, B.R. Comparison of efficacy of local hemostatic modalities in anticoagulated patients undergoing tooth extractions. Vojnosanit. Pregl. 2014, 71, 1097–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çakarer, S.; Eyüpoğlu, E.; Günes, Ç.Ö.; Küseoğlu, B.G.; Berberoğlu, H.K.; Keskin, C. Evaluation of the hemostatic effects of Ankaferd blood stopper during dental extractions in patients on antithrombotic therapy. Clin. Appl. Thromb. Hemost. 2013, 19, 96–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halfpenny, W.; Fraser, J.S.; Adlam, D.M. Comparison of 2 hemostatic agents for the prevention of postextraction hemorrhage in patients on anticoagulants. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod. 2001, 92, 257–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.R.; Kumar, J.; Sarvagna, J.; Gadde, P.; Chikkaboriah, S. Hemostasis and post-operative care of oral surgical wounds by HemCon dental dressing in patients on oral anticoagulant therapy: A split mouth randomized controlled clinical trial. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2016, 10, ZC37–ZC40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malmquist, J.P.; Clemens, S.C.; Oien, H.J.; Wilson, S.L. Hemostasis of oral surgery wounds with the HemCon dental dressing. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2008, 66, 1177–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamoto, T.; Ishikawa, I.; Kumasaka, A.; Morita, S.; Katagiri, S.; Okano, T.; Ando, T. Blue-violet light-emitting diode irradiation in combination with hemostatic gelatin sponge (Spongel) application ameliorates immediate socket bleeding in patients taking warfarin. Oral. Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2014, 117, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scarano, A.; Sinjari, B.; Murmura, G.; Mijiritsky, E.; Iaculli, F.; Mortellaro, C.; Tetè, S. Hemostasis control in dental extractions in patients receiving oral anticoagulant therapy: An approach with calcium sulfate. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2014, 25, 843–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svensson, R.; Hallmer, F.; Englesson, C.S.; Svensson, P.J.; Becktor, J.P. Treatment with local hemostatic agents and primary closure after tooth extraction in warfarin treated patients. Swed. Dent. J. 2013, 37, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Carter, G.; Goss, A. Tranexamic acid mouthwash—A prospective randomized study of a 2-day regimen vs. 5-day regimen to prevent postoperative bleeding in anticoagulated patients requiring dental extractions. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2003, 32, 504–507. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Queiroz, S.I.M.L.; Silvestre, V.D.; Soares, R.M.; Campos, G.B.P.; Germano, A.R.; da Silva, J.S.P. Tranexamic acid as a local hemostasis method after dental extraction in patients on warfarin: A randomized controlled clinical study. Clin. Oral Investig. 2018, 22, 2281–2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harfoush, M.; Boutros, E.; Al-Nashar, A. Evaluation of topical application of platelet rich fibrin (PRF) in homeostasis of the bleeding after teeth extraction in patients taking warfarin. Int. Dent. J. Stud. Res. 2016, 4, 144–147. [Google Scholar]

- Sammartino, G.; Dohan Ehrenfest, D.M.; Carile, F.; Tia, M.; Bucci, P. Prevention of hemorrhagic complications after dental extractions into open heart surgery patients under anticoagulant therapy: The use of leukocyte- and platelet-rich fibrin. J. Oral Implantol. 2011, 37, 681–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Belasy, F.A.; Amer, M.Z. Hemostatic effect of n-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate (histoacryl) glue in warfarin-treated patients undergoing oral surgery. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2003, 61, 1405–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blinder, D.; Manor, Y.; Martinowitz, U.; Taicher, S.; Hashomer, T. Dental extractions in patients maintained on continued oral anticoagulant: Comparison of local hemostatic modalities. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod. 1999, 88, 137–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, G.; Goss, A.; Lloyd, J.; Tocchetti, R. Tranexamic acid mouthwash versus autologous fibrin glue in patients taking warfarin undergoing dental extractions: A randomized prospective clinical study. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2003, 61, 1432–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, R.V.; Gadelha, T.B.; Luiz, R.R.; Torres, S.R. Intra-alveolar epsilon-aminocaproic acid for the control of post-extraction bleeding in anticoagulated patients: Randomized clinical trial. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2018, 47, 1138–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eldibany, R.M. Platelet rich fibrin versus Hemcon dental dressing following dental extraction in patients under anticoagulant therapy. Tanta Dent. J. 2014, 11, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberti, L.; Piva, A.; Beltramini, G.; Candotto, V. Calcium sulphate for control of bleeding after oral surgery in anticoagulant therapy patients. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2020, 34 (Suppl. 1), 109–113. [Google Scholar]

- Pippi, R.; Santoro, M.; Cafolla, A. The effectiveness of a new method using an extra-alveolar hemostatic agent after dental extractions in older patients on oral anticoagulation treatment: An intrapatient study. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2015, 120, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, E.C.; Costa, F.W.; Bezerra, T.P.; Nogueira, C.B.; de Barros Silva, P.G.; Batista, S.H.; Sousa, F.B.; Sá Roriz Fonteles, C. Postoperative hemostatic efficacy of gauze soaked in tranexamic acid, fibrin sponge, and dry gauze compression following dental extractions in anticoagulated patients with cardiovascular disease: A prospective, randomized study. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2015, 19, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Almeida Barros Mourão, C.F.; Miron, R.J.; de Mello Machado, R.C.; Ghanaati, S.; Alves, G.G.; Calasans-Maia, M.D. Usefulness of platelet-rich fibrin as a hemostatic agent after dental extractions in patients receiving anticoagulant therapy with factor Xa inhibitors: A case series. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2019, 23, 381–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ockerman, A.; Miclotte, I.; Vanhaverbeke, M.; Vanassche, T.; Belmans, A.; Vanhove, J.; Meyns, J.; Nadjmi, N.; Van Hemelen, G.; Winderickx, P.; et al. Tranexamic acid and bleeding in patients treated with non-vitamin K oral anticoagulants undergoing dental extraction: The EXTRACT-NOAC randomized clinical trial. PLoS Med. 2021, 18, e1003601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Drada, J.A.; Abreu, L.G.; Lino, P.A.; Parreiras Martins, M.A.; Pordeus, I.A.; de Abreu, M.H.N.G. Effectiveness of local hemostatic to prevent bleeding in dental patients on anticoagulation: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. J. Craniomaxillofac. Surg. 2021, 49, 570–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelen, E.T.; Schutgens, R.E.; Mauser-Bunschoten, E.P.; van Es, R.J.; van Galen, K.P. Antifibrinolytic therapy for preventing oral bleeding in people on anticoagulants undergoing minor oral surgery or dental extractions. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 7, CD012293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filho, E.L.C.; Franco, J.M.P.L.; Ribeiro, T.R.; Silva, P.G.B.; Costa, F.W.G. Does platelet-rich fibrin prevent hemorrhagic complications after dental extractions in patients using oral anticoagulant therapy? J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2021, 79, 2215–2226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowski, B.; Myszka, A.; Migut, M.; Czenczek-Lewandowska, E.; Brodowski, R. Analysing the effectiveness of topical bleeding care following tooth extraction in patients receiving dual antiplatelet therapy-retrospective observational study. BMC Oral Health 2021, 21, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Napeñas, J.J.; Oost, F.C.; DeGroot, A.; Loven, B.; Hong, C.H.; Brennan, M.T.; Lockhart, P.B.; van Diermen, D.E. Review of postoperative bleeding risk in dental patients on antiplatelet therapy. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2013, 115, 491–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).