Abstract

Understanding radicalization pathways, drivers, and factors is essential for the effective design of prevention and counter-radicalization programs. Traditionally, the primary methods used by social scientists to detect these drivers and factors include literature reviews, qualitative interviews, focus groups, and quantitative methods based on surveys. This article proposes to complement social science approaches with computational methods to detect these factors automatically by analyzing the language signals expressed in social networks. To this end, the article categorizes radicalization drivers and factors following the micro, meso, and macro levels used in the social sciences. It identifies the corresponding language signals and available language resources. Then, a computational system is developed to monitor these language signals. In addition, this article proposes semantic technologies since they offer unique exploration, query, and discovery capabilities. The system was evaluated based on a set of competency questions that show the benefits of this approach.

1. Introduction

Our society has become more polarized in recent years, with sources of division being political, economic, and religious. Polarization threatens social cohesion and can be the source of radicalization and violent extremism. Thus, many countries and international organizations have developed counter-radicalization programs and strategies for radicalization prevention, deradicalization, and disengagement [1].

This research work aims to contribute to counter-radicalization efforts. It has been developed within the R&D project PARTICIPATION [2], whose purpose is to prevent extremism, radicalization, and polarization that can lead to violence through more effective social and education policies and interventions. The design of these policies will be based on a participatory approach, where radicalization drivers are taken into account to prevent the radicalization process.

Understanding radicalization pathways, drivers, and factors is essential for the effective design of prevention and counter-radicalization programs. Traditionally, the primary methods used by social scientists to detect these drivers and factors include literature reviews, qualitative interviews, focus groups, and quantitative methods based on surveys. This article studies the perspective of complementing social science approaches with computational methods to detect these factors automatically by analyzing the language patterns expressed in social networks. In particular, we aimed to develop a computational system that helps social scientists understand different types of radicalization. For this purpose, three research questions were defined to guide us through the research process:

- RQ1

- What are the main linguistic signals that reveal radicalization factors?

- RQ2

- How can we computationally operate radicalization factors to monitor radicalization?

- RQ3

- How can semantic technology provide fine-grained query capabilities to social scientists to get insights from radicalization processes?

In this way, the contributions of this paper are threefold. First, we present a detailed study of the process that takes current analysis systems from considering radicalization drivers to radicalization signals. Such a step is of paramount importance for the field, since radicalization drivers (e.g., social, psychological, and emotional factors) need to be modeled appropriately from a computational perspective, thereby obtaining radicalization signals. Second, to enhance the data enrichment, the second main contribution of this work is the generation of four novel semantic vocabularies that allow us and the system to model several radicalization and extremism phenomena from a semantic perspective. Finally, to concretely enhance the radicalization signals studied, the third contribution of this work is an intelligent end-to-end engine that monitors radicalization and extreme language on social media using appropriate Natural Language Processing (NLP) methods in the field of radicalization analysis.

The remainder of this article is organized as follows. First, in Section 2, we review the literature to understand the linguistic signals used to detect radicalization drivers and factors (RQ1). In Section 3, the linked data concepts and vocabularies employed to model the data semantically in this work are summarized (RQ3). Then, in Section 4, we present the software methods and architecture designed to provide social scientists with a dashboard for monitoring radicalization (RQ2 and RQ3). Section 4 also presents the results of the developed software component and the developed dashboard (RQ2). In Section 5, we present an evaluation of the query capabilities of the proposed semantic technology (RQ3). Section 5 includes a discussion comparing the proposed approach with other similar works. Finally, the conclusions of the research done and new perspectives for research are given in Section 6.

2. From Radicalization Drivers to Radicalization Signals

Social signals [3] are “communicative or informative signals which, directly or indirectly, provide information about social facts, that is, about social interactions, social attitudes, social relations, and social emotions.” Humans produce social signals in diverse modalities [3], such as words, acoustic features, gestures, posture, head movements, facial expression, gaze, proxemics, touch, physical contact, and spacial behavior. In this work, we are explicitly interested in social signals, which can be derived from the texts posted on social networks and social interactions (e.g., reply, retweet, like, and so on). These signals are known as the social context, which be defined as “the collection of users, content, relations, and interactions which describe the environment in which social activity takes place” [4].

When it comes to detecting radicalization signals in texts posted on social networks, many works have focused on analyzing, detecting, and predicting radicalization [5,6]. Online radicalization analysis aims at improving security agencies’ decision processes by providing insights about the network structure (e.g., leaders and communities) and the posted contents (e.g., authorship identification and stylometric and affect analysis) [5]. Detection works [7] focus on detecting radicalization activity. For example, Nouth et al. [8] proposed a system that classifies tweets as Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) supporters or not. For this purpose, they combined micro and macroanalysis using textual and social network features. The microanalysis consists of stylistic signals (extracted from the Dabiq magazine) and psychological, personality, and emotional signals, extracted with the Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count (LIWC) [9] dictionary. Meso analysis evaluates user activity, followers/following ratio, and the influence of users extracted from the mentioned interaction graph. Fernández et al. [6] analyzed the three roots of radicalization (micro, meso, and macro) to understand the radicalization pathway through the analysis of ISIS supporters’ antecedents. First, they characterized the micro and meso levels as the posts created and shared by users. Second, they analyzed the shared web addresses in the posts at the macro level. Third, they proposed computing the influence of each level by calculating the similarity of these posts (created or shared) with lexicons of radical language. Finally, Araque et al. [10] concluded that emotional signals are adequate for characterizing radical language.

However, most works address analysis, detection, and prediction as a binary classification task that classifies individuals into radicals and not radicals. Instead, in this work, we are interested in identifying radicalization factors.

Van Brunt et al. [11] suggested that radicalism and extremism can be considered a continuum. Based on the research desk, the authors provided a taxonomy of risk, protective, and mobilization factors. Risk factors are thoughts or behaviors that have been present in radicalization pathways. Most of them are considered radicalization drivers, such as hardened points of view, marginalization, perceived discrimination, and connection to extremists. In contrast, protective factors are those that reduce the impacts of risk factors and should be targeted in counter-radicalization policies. They include social connection, pluralistic inclusivity, resilience, emotional stability, and professional engagement. Finally, mobilization factors are those present when an individual transitions from a planned radicalization toward implementation. These factors are a direct threat, escalation to action, increased group pressure, and leakage.

Several models have been defined to describe, identify, and counter the pathway to violent extremism [12], such as the Pathway to Violence Model [13] and the Warning Behaviors Model [14].

The Pathway to Violence Model was developed by the United States Secret Service (USSS) through the analysis of assassins and school shooters. The model proposes six stages in the radicalization process: grievance, ideation, research and planning, preparation, breach, and attack. In addition, some works [15,16] have applied psycholinguistic analysis of mass shooters’ communications to identify recurrent topics of nihilism, ego survival, revenge fantasy, alienation, entitlement, and envy.

The Warning Behaviors Model was developed by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and proposes patterns of conduct (warning behaviors) that can help law enforcement agencies to focus their investigations. The model includes eight behaviors: pathway, fixation, identification, novel aggression, energy bust leakage, last resort, and directly communicated threats. From these behaviors, the application of linguistic analysis has been successful in the identification of leakage, fixation, and identification warning behaviors [17,18]. Leakage is the communication to a third party to harm a target, including the planning, research, or implementation of an attack [14,17]. Fixation is any behavior that indicates that someone is increasingly preoccupied with a person or cause and is usually accompanied by deterioration in relationships or occupational performance [14]. Identification is the psychological desire to be a “pseudocommando” or have a “warrior mentality”. This includes associations with weapons and military paraphernalia and identification with previous attackers or assassins.

Cohen et al. [17] identified linguistic markers for these warning behaviors. In particular, they proposed the use of a dictionary of violent words expanded with Wordnet [19] for terms such as massacre to detect leakage. Instead, for fixation, they proposed identifying the targets of this fixation by calculating the relative frequency of entities in the text. Finally, for identification, they proposed to identify positive adjectives when mentioning ingroup and negative emotions when mentioning out-group, using software such as LIWC [9]. Grover et al. [18] analyzed the alt-right political movement on the social network Reddit. This ideological movement is a far-right group concerned with preserving white identity. They proposed three signals for identifying fixation: increasing perseveration on the person or cause, increased negative account of object fixation, and increasingly strident opinions and angry emotional undertones. The first signal was identified using term frequency and term frequency-inverse document frequency (TF-IDF) to identify the main topics discussed in the forums (i.e., WhiteEthno, JewOrBlack, OtherRacial, and RacialSlang). As a result, they created a dictionary of terms associated with racial words. The second and third signals analyze the presence of negative emotions, anger, sadness, anxiety, the emotional tone, and texts classified as hate speech or offensive language. For this purpose, they used the LIWC [9] dictionary and the software HateSonar [20]. Finally, they proposed to characterize the warning behavior group identification with the proportion of first-person plural words, third-person plural words, and the ratio of first-person plural and third-person plural words to first-person singular words.

The same categories proposed by Grover et al. were analyzed by Torregrosa et al. [21] to analyze the alternative right far-right political group on Twitter, commonly known as the “alt-right”. In this case, they proposed a mesoanalysis based on social network metrics to study whether there are correlations between centrality measures and linguistic analysis. They concluded that user relevance is related to linguistic patterns of extremist discourse. Moreover, super-spreader users use more words related to far-right dictionaries. This work used the LIWC [9] dictionary and the software Vader [22] for analyzing linguistic properties and tone.

Smith et al. [23] researched the detection of psychological within-person changes through mobilizing interactions in social media. For this purpose, they conducted a pilot with a sample of Hong Kong residents during the violent protests of 2019. The detection of mobilizing interactions was based on the analysis of short texts written by the participants describing the political situation to detect collective action intentions (e.g., “I intend to encourage the family to sign a petition to stand up for the cause”). The driver of this radicalization is a socially grounded grievance that urges us to change the unjust situation via collective actions. To detect this grievance feeling, the authors detected emotional reactions. In particular, they used the LIWC dictionary [9] to detect anger and the Moral Foundations Theory (MFT) [24] dictionary to detect harm. Their results conclude that communication, including harm, threat, and anger, was mobilizing and increasing support for the undertaking of collective actions. Based on these results, they conducted a significant study to research engaging online interactions on Twitter to support the extremist group Daesh. They detected 65 features associated with expressing support for Daesh. In addition to LIWC and MFT, they use a vernacular Daesh dictionary since the use of ingroup jargon is a relevant sign of group identity. In order to understand the radicalization process whose signal is within-person changes in linguistic style, they carried out a mesoanalysis considering aspects such as the number of sequential LIWC accounts, followers, and following. They concluded that changes in the linguistic style and vernacular word use are associated with engaging in mobilizing interactions. This enables the detection of radicalization processes. Nevertheless, they did not disclose the feature set or annotated datasets with narratives for ethical reasons, since there is not yet a gold standard to evaluate its generality.

Torregrosa et al. [25] analyzed the difference in the language used between pro-ISIS users and random users. Their findings are that ISIS supporters use more third-person plural pronouns and fewer first and second-person pronouns. In addition, they use more words related to death, certainty, and anger. They use the LIWC [9] dictionary.

Alizadeh et al. [26] analyzed if psychological and moral variables exist that correlate with political orientation and extremity. For this purpose, they analyzed Twitter accounts of both neo-Nazis as right-wing extremists and Antifa as left-wing extremists. Their study included a validation of the LIWC [9] and MFT [24] dictionaries for extremist-written tweets. They concluded that left-wing extremists express some language indicating anxiety between the four political groups (liberals, conservatives, left-extremists, and right-extremists). In addition, right-wing extremists express more positive emotions and fewer negative emotions than left-wing extremists. Regarding the MFT, right-wing extremists use language more indicative of obedience to authority and purity and more language indicative of fairness and harm avoidance than left-wing extremists.

Lara-Cabrera et al. [27] proposed identifying several vulnerability factors based on text analysis. They analyzed two personality factors, frustration and introversion, and three attitudes and beliefs towards the Muslim religion and Western society. The detection of frustration was based on swear words and sentences with a negative connotation. Regarding introversion, the proposal was to leverage the sentence length and the use of ellipses. Finally, they used keywords to count the perception of being discriminated against for being Muslim, negative opinions about Western society, and positive ideas about jihadism.

Several recent language resources provide new possibilities for understanding better extremist language. The Grievance Dictionary [28] is a psycholinguistic dictionary for grievance-fueled threat assessment. The dictionary defines the following categories: planning, violence, weaponry, help-seeking, hate, frustration, suicide, threat, grievance, fixation, desperation, deadline, murder, relationship, loneliness, surveillance, soldier, honor, impostor, jealousy, god, and paranoia. Most categories are correlated to related LIWC categories, as expected. ExtremeSentiLex [29] is a lexicon to detect extreme sentiments based on SentiWordNet [30] and SenticNet [31]. It has detected 29% and 33% of extreme positive posts in the extremist religious forums Ansar1 [32] and TurnToIslam [33], respectively, in contrast with only 2% and 4% of extreme negative posts.

While radicalization signals are adequate for understanding radicalization better and its use in surveillance tasks, data processing is not enough. Visualization techniques [34] allow humans to search for patterns more effectively. In addition, visualization techniques can be an excellent tool for dissemination and awareness.

Several works have been particularly relevant for the monitoring of hate speech. Contro l’odio [35] is a web platform for monitoring immigrants’ discrimination and hate speech in Italy. It provides the results of linguistic analysis in interactive maps. It has been used in educational courses for high school students and citizens with the aim of the deconstruction of negative stereotypes. HateMeter [36] is a European project for monitoring, analyzing, and fighting anti-Muslim hatred online. It has been used to help Non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and social science research analyze and prevent hate speech use [37].

Regarding the linguistic analysis of radicalism, the project Trivalent H2020 [38] developed a dashboard to monitor social media targeted at Law Enforcement Agencies. In the same way, Beheshti et al. [39] developed a dashboard to enable social network analysts to understand patterns of behavioral disorders over time.

Finally, Table 1 summarizes the review presented in this section, including the level type (i.e., micro, meso, macro), the radicalization drivers and factors, the language signals, the data resources, and the references to the literature related to them.

Table 1.

Summary of literature survey regarding language signals for monitoring radicalization.

3. Semantic Modeling

By leveraging the linked data principles, any operator or program can consult the published information, make sense of it, enrich it by combining it with other semantic sources, and even reason about it using the ontologies provided. The benefits of linked data have been extensively discussed, especially in the field of linguistics [40,41]. Multiple projects have leveraged linked data for knowledge generation, interoperability, and publication of results [42,43].

Discussing the full breadth of benefits of semantic modeling and linked data is beyond the scope of this work. For the purpose of this paper, two things should be noted. First, a semantic endpoint will be capable of responding to arbitrary but semantically meaningful queries. One such example might be: “where was #example hashtag twitted from on January 1st?” In contrast with other technologies, which would be based on strict schemas (e.g., SQL) or limited query languages (e.g., ElasticSearch or MongoDB), the linked data endpoints: (1) represent information as knowledge graphs (the RDF model), and (2) enable information access and manipulation through a set of standard web technologies (HTTP and SPARQL). Second, domain knowledge (i.e., what information can be expressed, and how it is represented in the graph) is provided by semantic vocabularies or ontologies. This section focuses on the specific vocabularies that have been used in this work. The aim is twofold: (1) to allow other researchers to better understand and query the information published; and (2) to propose a comprehensive and cohesive model for representation for this specific domain, most of which could be later reused or improved upon by researchers working in the same field.

In the spirit of the linked data principles, existing vocabularies have been used when possible. For instance, the fields in a tweet are mainly modeled using the Semantically-Interlinked Online Communities (SIOC) Core Ontology, supported by some properties from Schema.org and Dublin Core Metadata Initiative (DCMI). In particular, we have reused SIOC [44] to model social media content, DCMI [45] for metadata, DBpedia [46] for linking entities mentioned in tweets, NLP Interchange Format (NIF) [47] for text annotation, Onyx [41] for emotion annotation, and Marl [48] for sentiment annotation.

We have also reviewed other vocabularies, such as the radicalization ontology [49]. This ontology includes a central class Message that represents social media messages. This class is linked to the user of the social network, radicalization indicators (introversion, frustration and negative feelings, negative ideas about western society, etc.), the focus (jihadism, discrimination, Islamism, West), mentions (i.e., weapons, tactics, and terrorist organizations), and intention towards a topic, which details positive and negative emotions and negative actions. In future work, this ontology could be combined with the ontologies proposed in this article to provide a fine-grained ontology of radicalization. In fact, the ontologies proposed in this article provide a first step in the semantic characterization of psycho-social indicators and moral values.

In addition to that, there were several specific types of annotations that are not modeled in any of the publicly available vocabularies to the extent of our knowledge. Therefore, this work has required the creation of new vocabulary. Once again, instead of creating a single vocabulary with all the missing elements, these pieces have been separated into smaller individual vocabularies to foster reusability. The following vocabularies have been defined:

- Semantic LIWC (SLIWC) vocabulary [50] is a semantic taxonomy and vocabulary for annotations using the LIWC dictionary.

- MFT vocabulary [51], a vocabulary to model annotations in accordance with the MFT.

- Narrative vocabulary [52] contains the concepts necessary to annotate NIF or SIOC elements with a narrative component.

Each vocabulary will be explained in further detail in Section 3.1, Section 3.2 and Section 3.3, respectively. Moreover, their usage combined with The Senpy Ontology (SENPY) vocabulary [53], a vocabulary to annotate a NIF Context, is exemplified in Section 3.4.

3.1. Semantic Vocabulary for LIWC (SLIWC)

The widespread use of LIWC for social-psychological analysis has established its psychometric properties as a de facto standard, both in industry and in academia. LIWC annotations can be separated into two distinct parts: the annotation model and the specific dimensions (and sub-dimensions) used in each specific version of the LIWC dictionary. LIWC’s popularity has led several projects to adapt its annotation model when publishing their own LIWC-aligned lexicons, as will be seen in Section 3.2. Hence, our goal is to provide not only a vocabulary that models LIWC annotations, but a model that can be reused and extended by other vocabularies that model LIWC-aligned vocabularies. The result is the SLIWC [50], which covers both the annotation model and the dimensions in different versions of LIWC.

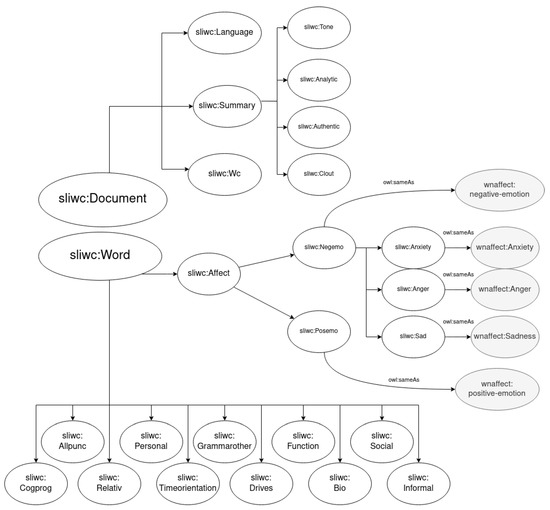

The problem of annotations is hardly limited to LIWC. In fact, there are multiple competing vocabularies in the space (e.g., NIF). Unfortunately, none of the existing vocabularies is a perfect fit in this case due to the restrictions imposed by the use of JSON-LD in several parts of the system and the need for a clean JSON schema. Hence, we decided to design a very minimal annotation model, which can both be integrated with NIF and generate a friendlier JSON schema. The model has been inspired by previous experience with Onyx [41]. Most notably, it is also aligned with the provenance ontology [54], which allows for annotations to be linked to the process and/or agent that generated them. This is especially useful when dealing with multiple NIF services, all of which may add their own annotations to a piece of content. A summary of the result is shown in Figure 1. The main elements are: the annotation activity (AnnotationActivity), the annotation set (ASet), the annotation (Annotation), and the category (Category).

Figure 1.

Main concepts related to annotation in the SLIWC vocabulary.

When a piece of content is annotated, either manually or through an automatic process, one or more annotation sets will be generated, linking both to the original piece of content and to the activity that generated the annotation. Each annotation set will contain one or more annotations. When an annotation set contains more than one annotation, they should be considered as related and processed together. For instance, an activity may generate an annotation set with a count of positive and negative words within some piece of content. If we were to process them individually, we might reach an ambiguous conclusion that the content is both positive and negative. By including them inside the same annotation set, we are signaling that neither of them should be considered individually, and we allow for other activities to produce further annotation sets that aggregate existing multi-annotation sets into simpler sets with a single annotation. In our example, a new activity might add a new annotation set that produces the net count, subtracting the negative words from the positive ones. An annotation will have a category, depending on the type of dictionary used and multiple properties. Depending on the type of activity, the annotation may express how many occurrences (typically, words) were found of the given category in the content (count) and the ratio of occurrences of that category over the total (ratio). More generally, annotation can provide a normalized score (score).

The second part of the vocabulary consists of a taxonomy of all the annotation dimensions and labels in LIWC. The list of dimensions and labels were extracted from the LIWC website [55]. Furthermore, the dimensions are structured in a hierarchical manner. Hence, the dimensions in the vocabulary have been expressed as a Simple Knowledge Organization System (SKOS) taxonomy [56].

The main dimensions categories measured by LIWC for our work are grouped in sets depending on the psychological process they are describing. Four of them were taken into account for this analysis: drives, affective, personal concerns, and social. The Drives set gives insight into the motivations of the person behind the text. It measures five parameters, which are affiliation, achievement, power, reward, and risk. Feelings such as anxiety, anger, sadness, and positive and negative emotions are part of the Affective Process set. The Personal Concerns set measures how text expresses different life issues such as work, leisure, home, money, religion, and death. Drives, affective concerns, and personal concerns are considered the three main psychological variables and have been used as a reference to analyze radical discourses [57]. The Social Process set was also included to provide some more information about references to family, friends, and female and male authority figures.

A total of 110 dimensions categories were identified. Some of the dimensions are simply hierarchical and cannot be used for annotation (e.g., Summary Variable), some are only annotation labels (e.g., 1st pers singular), and some serve both purposes (e.g., Function Word). However, a specific branch in the taxonomy should be mentioned, sliwc:Affect, under the Word annotation concept. This dimension is dedicated to affective information. As of this writing, there are two main sub-dimensions, one for positive emotion and another one for negative emotion. The second one is further split into three dimensions: sad, anxiety, and anger. In addition to adding these dimensions, we have aligned them with existing affective ontologies. More specifically, they have been mapped to WordNet-Affect [58], using the existing semantic taxonomy [41]. The equivalencies are also shown in Figure 2: wnaffect :positive-emotion, wnaffect:negative-emotion, wnaffect:sadness, wnaffect:anxiety, and wnaffect:anger. A summary of the dimensions in the SLIWC vocabulary, which are more relevant for this work, can be seen in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

SLIWC taxonomy, simplified, focusing on its connection to WordNet-Affect. Dimensions are represented in different font sizes to emphasize their hierarchical relation.

3.2. Vocabulary for the Moral Foundation Theory (MFT)

The popularity of LIWC has led to several LIWC-like dictionaries. One of such dictionaries is the Moral Foundations Dictionary (MFD) [59], which includes new annotations for morality. MFT [60] identifies six universal moral foundations that exist across cultures. Each foundation can be considered a vice or a virtue from a moral point of view. The six foundations (virtue/vice) that describe political views are:

- Fairness, equality, or reciprocity/cheating: notions of rights and justice.

- Care/harm: compassion, protection of community members.

- Loyalty or ingroup/betrayal: respect for the norms of the group, patriotism, and sacrifice for the group.

- Authority or respect/subversion: obedience to authority figures and hierarchical structures.

- Purity or sanctity/degradation: promotion of sacred values, chastity, control of one’s desires.

- Liberty/oppression: feelings of reactance and resentment people feel toward those who dominate them and restrict their liberty.

Moral dimensions are usually classified into individualizing and binding foundations [24]. Individualizing foundations (e.g., care/harm and fairness/cheating) deal with the roles of individuals within social groups. Binding foundations (e.g., loyalty/betrayal, authority/subversion, purity/degradation, and liberty/oppression) are related to the formation and maintenance of social groups.

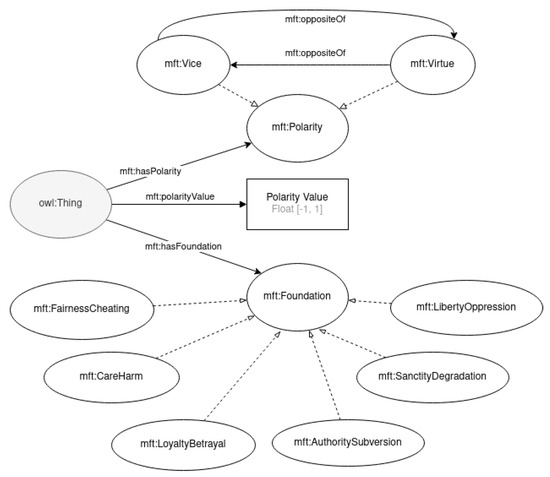

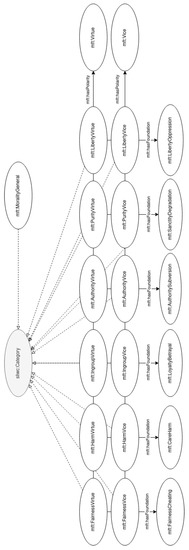

This article presents a proposal of a semantic vocabulary for morality annotations [51] which is composed of two main classes: Foundation, which represents an MFT foundation; and Polarity, to represent a polarity within a given foundation. Six entities of type Foundation have been defined: FairnessCheating, CareHarm, LoyaltyBetrayal, AuthoritySubversion, SanctityDegradation, and LibertyOppression. Polarity has two extremes, vice (Vice) and virtue (Virtue), although other classifications are possible through the use of the Polarity class. The two polarities are defined as opposites of each other, using the oppositeOf property in both instances. Moreover, a numeric value can be assigned to express this intensity (polarityValue). Positive values are typically associated with a virtue class, and negative values correspond to a vice. To tie these two concepts together, the vocabulary also includes the concept of a MoralValue, which is associated with a foundation (annotated through hasFoundation) and a polarity (through hasPolarity). The main elements of the vocabulary can be seen in Figure 3, and the annotation categories are detailed in Figure 4. An example of its use for the annotation of a text is shown in Section 3.4.

Figure 3.

The morality ontology.

Figure 4.

The annotation categories for MFT.

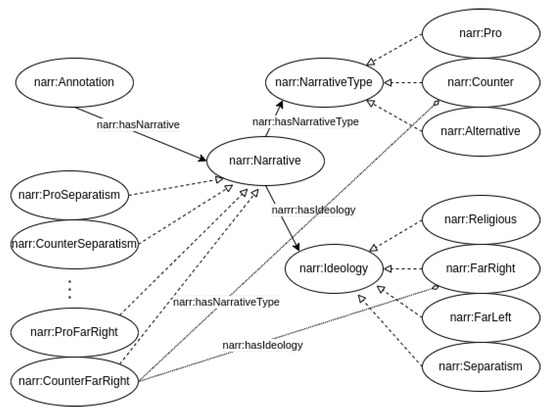

3.3. Vocabulary for Narrative

Lastly, in this work we require the annotation of the narrative of the tweet, described by the annotation type narr:Annotation. The ideologies and narratives present in a tweet are represented using the concepts defined in the narrative ontology [52], specifically created for this project and shown in Figure 5. The property narr:hasNarrative is used in this case to point to the narrative to which the text of the tweet refers. Narratives are represented with the narr:Narrative class. Several narrative types are included in the ontology as individuals, such as narr:ProReligion, and CounterSeparatism. Each narrative is connected to an ideology (through narr:hasIdeology), such as Religion, FarRight, FarLeft, or Separatism. The way in which the narrative type relates to the ideology is also modeled through the narr:hasNarrativeType property, which can take the values: Pro (radical narrative supporting radicalism), Counter (counter narrative that directly dispute and reject narratives), and Alternative (providing a different and positive story from combating the radical one).

Figure 5.

The narrative ontology. For clarity, only the relationships of one narr:Narrative (narr:CounterFarRight) with narr:NarrativeType and narr:Ideology are shown.

3.4. Examples of Semantic Annotation

To better explain how these ontologies interact, let us consider two examples of annotation: one for a corpus and another for a lexicon.

Corpora in this work are composed mainly of text messages with different labels, which are the results of different types of analysis (sentiment, emotion, etc.). Tweets were annotated using the same model as TweetsKB [61] (a public RDF corpus of anonymized data for a large collection of annotated tweets). Namely, tweets are represented with the sioc:Post class, and the SIOC Core Ontology, Schema.org, and DCMI ontologies can then be used to provide properties and attributes for most of the relevant fields in a tweet. For instance, the sioc:content attribute is used to provide the text content, sioc:has_creator for the author user, schema:inLanguage for the language it is written in, schema:mentions for its hashtags, dc:created for the creation date, and schema:locationCreated for the location it was posted from.

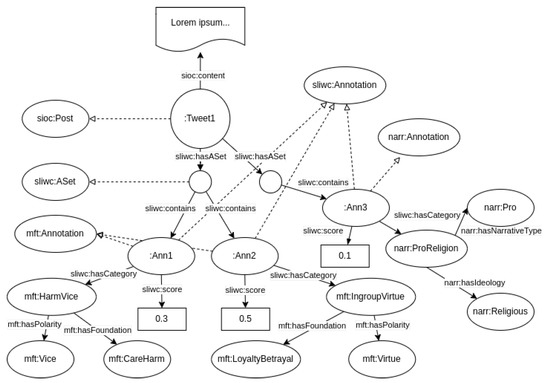

By combining that model with the ontologies mentioned above, the result for a given fully-annotated tweet would look similar to the diagram shown in Figure 6, which is further extended in Listing 1.

Figure 6.

Example of LIWC-aligned annotations of a Tweet using the morality and narrative ontologies.

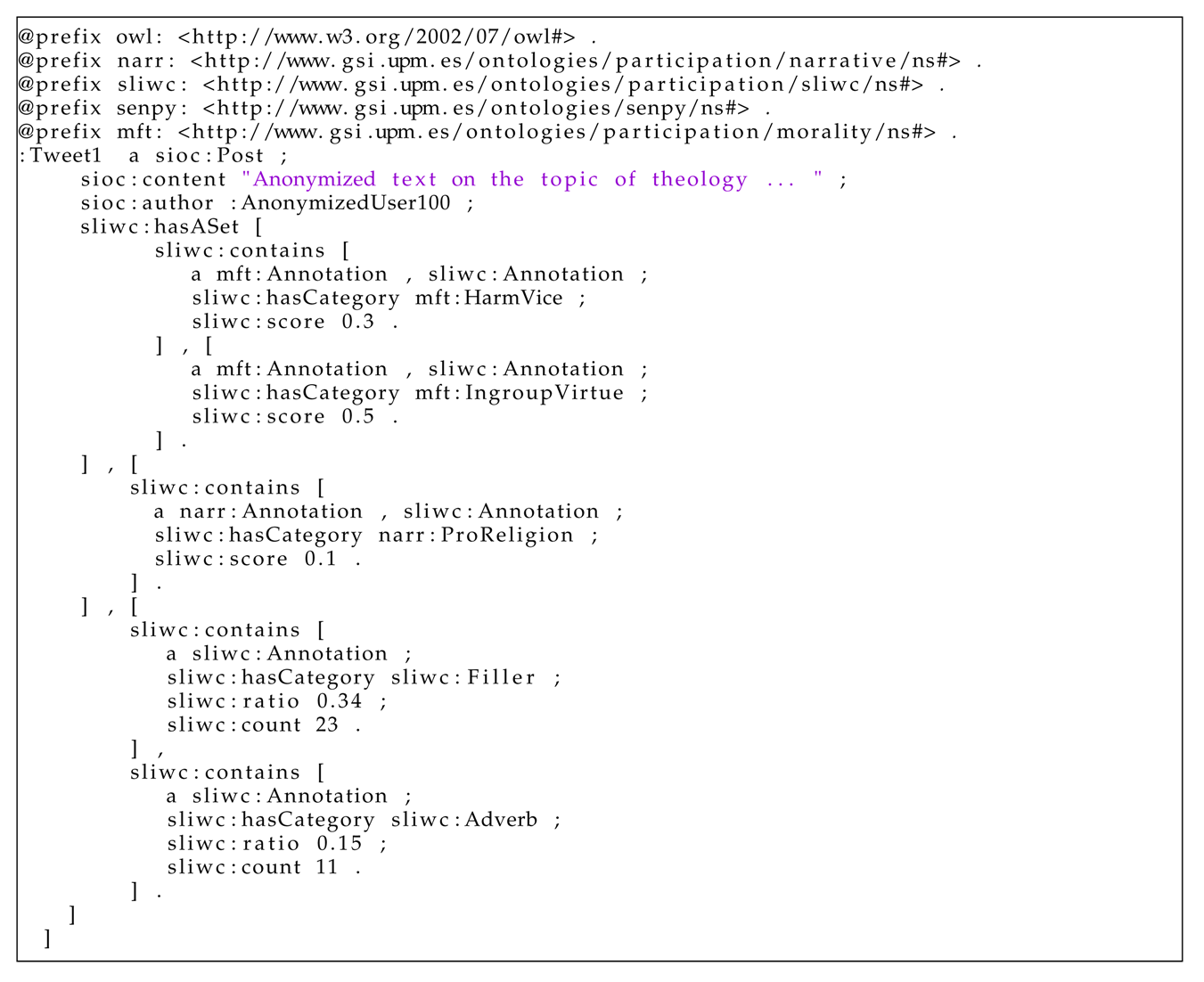

| Listing 1. Example of a tweet annotation. |

|

As shown in this example, the annotation of the tweet makes use of the morality ontology for annotating that the tweet contains the moral values ingroup virtue (mft:IngroupVirtue) and harm vice (mft:HarmVice). In addition, the narrative ontology used for annotating that the text was a religious narrative (narr:ProReligion). Finally, the SLIWC ontology annotates socio-psychological aspects. In particular, it has been used for annotating a linguistic dimension, the usage of adverbs (sliwc:Adverb), and a spoken or conversational dimension—the use of fillers (blah, you know, I mean, wow, etc.). The reader can observe that these semantic annotations can be seamlessly combined for fine-grained annotation.

The annotation of a lexicon is very similar to that of a tweet. In this case, the difference is that lexical entries are represented using the lemon ontology [62]. An example annotation of a lexicon can be observed in Listing 2.

| Listing 2. Annotation of lexical entry. |

|

4. Methods

To computationally capture and monitor the radicalization signals summarized in Table 1, this work proposes an intelligent engine that obtains data from social media, identifies political messages that could be considered radical, and analyzes them to extract useful information that provides insight into the feelings and motivations of people who spread such messages. Firstly, the general architecture of the intelligent engine is described (Section 4.1). Secondly, the source of data and the capturing methodology are explained in detail (Section 4.2). Then, the NLP technologies used for text processing and analysis are introduced (Section 4.3). Finally, the visualization dashboard is presented (Section 4.4).

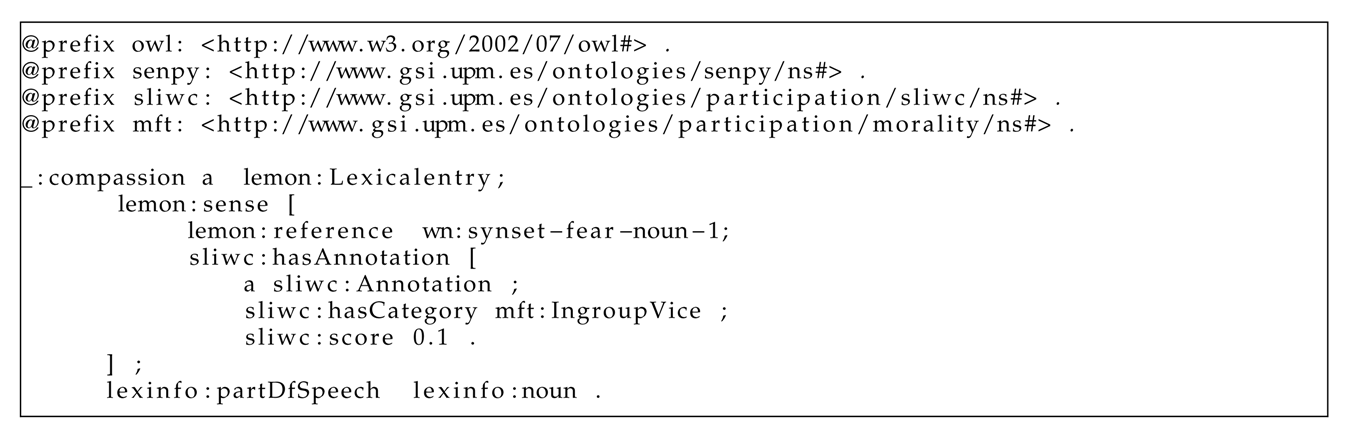

4.1. Software Architecture and Components

The implemented solution is based on a data pipeline that defines a workflow for processing messages from social networks. The pipeline is formed by a number of sequential tasks; each task can be executed by a different component. This section presents a modular toolkit for processing big linked data, encouraging scalability and reusability. The high-level architecture of this toolkit is depicted in Figure 7. It integrates existing open-source tools with others explicitly built for the toolkit.

Figure 7.

Tasks of the data pipeline.

The presented system is based on the big data reference architecture NIST Big Data Reference Architecture (NBDRA) [63] proposed by NIST. The NBDRA reference architecture has achieved consensus from academia and industry, being developed by a working group launched in 2013 with over six hundred participants from industry, academia, and government. It provides a vendor-neutral, technology, and infrastructure agnostic conceptual model of a big data architecture. It is intended to support data engineers, data scientists, data architects, software developers, and decision-makers to develop interoperable big data solutions. In this paper, the pipeline follows the NBDRA data processing steps: collection, preparation, analytics, visualization, and access.

Following this schema, the main modules of the architecture are orchestration, data ingestion, pre-processing, analysis, storage, and visualization, which are described below. In addition, an access facility is provided for processing semantic queries through a SPARQL Protocol and RDF Query Language (SPARQL) endpoint [64]. Please note that the whole system is implemented using Python.

The Orchestration module is responsible for managing the interactions of the rest modules by automating complex data pipelines and handling failures. This module enables reusability at the data pipeline level. In addition, it enables scalability, since every task of the workflow can be executed in a big data platform, via a Hadoop job [65], a Spark job [66], or a Hive query [67], to name a few. Finally, this module helps to recover from failures gracefully and rerun only the uncompleted task dependencies in the case of a failure. We have implemented the orchestration module with Luigi [68], which is used to orchestrate the different tasks across modules.

The Data Ingestion module involves obtaining data from the structured and unstructured data sources and transforming these data into linked data formats, using scraping techniques and APIs, respectively. The objective of this module is to extract the information from external sources and map it to linked data formats for its processing and storage. The use of linked data enables reusability of ingestion modules and interoperability and provides a uniform schema for processing data. The ingestion is implemented using GSICrawler [69], the module responsible for retrieving data. GSICrawler contains scraping modules based on Scrapy [70] and other modules that connect to external APIs. At the time of writing, there are modules for extracting data from Twitter, Facebook, Reddit, TripAdvisor, Amazon, RSS Feeds, and several specific sites, including some journals in PDF format.

The system captures data from Twitter through the selection and use of keywords to discover target messages, as is described in Section 4.2. In addition, GSICrawler also leverages the Twitter Application Programming Interface (API) through the Twint package [71], which obtains the data by parsing the HTML from Twitter’s browser version. In this way, GSICrawler has been configured to allow the selection of the preferred extraction method.

The Processing and Analysis module collects the different analysis tasks that enrich the incoming data, such as psychology analysis and moral value estimation through LIWC and MFT, respectively. The analysis is based on the NIF recommendation, extended for multimodal data sources. Each analysis task has been modeled as a plugin of SENPY. In this way, analysis modules can be easily reused.

This module also encompasses data preprocessing, which includes the necessary normalization and adaptation operations over the captured data. It performs two main processes: (i) NLP pre-processing and (ii) geolocation of social network posts. The pre-processing steps are implemented using the gsitk [72] library, which provides functionalities to parse and pre-process different types of texts, including Twitter posts. Regarding the geolocation of messages, the Google Geocode API [73] translates the location information to its geographic coordinates. Even though Twitter provides this type of information if the user permits them to do so, in practice, about 2% of the total tweets have their geographic coordinates publicly available [74]. It is more common for Twitter users to provide a fixed location in their user profiles. Although this is not an accurate measure for every tweet, this location information helps estimate which ideologies are more active in a specific region.

Analyzing the extracted textual data to enrich it, gain further insights, and discover patterns is crucial for the presented intelligent system. To achieve such analysis, the presented system uses Senpy [53], a framework to develop, integrate, and evaluate web services for text analysis. The text analyses performed in this module extracted emotional, psychological, and moral information from the text (for a detailed explanation of these linguistic analyses, please consult Section 4.3). For extracting such annotations, we use the (i) LIWC dictionary and the (ii) Moral Foundations Dictionary (MFD). This module implements these processes using Senpy plugins, which are modular software additions that can be inserted into the system to enhance its functionality.

The representation of these data is done using semantic annotations, as discussed in Section 3. Once the analysis scores are computed in each text, the data are aggregated by ideology and narrative, although the system retains the original measures.

The Storage module is responsible for storing data in a NoSQL database. We have selected ElasticSearch [75], since it provides scalability, text search, and a RESTful server based on a Query DSL language. We use a subset (or dialect) of JSON, JSON-LD [76], which adds a semantic annotation to plain JSON objects to retain semantics. The system also stores the semantic data into Fuseki’s SPARQL endpoint [77]. As a SPARQL endpoint, Fuseki can be accessed using semantic queries.

The Visualization module enables building dashboards and executing semantic queries. Visualization is based on Kibana [78], on top of which, an array of components have been configured to enable faceted search. The dashboard provides an interface where users can apply filters and understand the analysis. It has different filtering and visualization functionalities. For example, users can use filters or click on elements within a visualization to display charts with particular inputs. In addition, the Apache Fuseki [77] interface is exploited to allow users to perform SPARQL queries, thereby enabling complex searches.

4.2. Data Source Selection

Previous works describe counter and alternative narratives and their impacts on preventing radicalization [79,80,81]. Extremist groups disseminate their ideas and reach a broad audience using social media [82]. Due to this, a clear focus for the proposed intelligent engine is Twitter [83] messages.

The text of Twitter messages can include keywords (hashtags) that aid in their thematic classification. We leveraged hashtags to retrieve tweets that support target ideologies and narratives in this system. Additionally, the presented system considers other characteristics, such as creation date, author profile, the language of the text, and location. From a general view, the presented intelligent engine uses all this information, enriching and contextualizing the original content.

To center our use cases, we defined a schema that categorizes messages into the following ideologies: religious, separatist, far-right, and far-left. In addition, we consider three possible narratives for each ideology: pro, counter, and alternative. The system uses hashtags as a guide to capturing messages that belong to these ideologies and narratives. Table 2 presents the list of hashtags used to retrieve Twitter messages. Said list has been compiled based on previous works [36].

Table 2.

Hashtags are used to capture messages organized by ideology and narrative.

4.3. Linguistic Processing

A thorough linguistic study was performed on the captured data as a relevant part of the developed intelligent engine. In this way, the original data were enriched using a linguistic analysis that contextualized and offered valuable insights. One of the most relevant processes involves using two relevant linguistic frameworks intimately related to radicalization and its presence in text: the (i) Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count (LIWC) [84] resource and the (ii) Moral Foundations Theory (MFT) [24]. This selection of resources followed previous works, as described in Section 2 (see Table 1).

Once each tweet was selected and tagged by ideology and narrative based on its hashtags, it was pre-processed and analyzed, thereby enriching its original information, using the semantic models shown in Section 3. Consequently, the geographical location was extracted from all tweets, which could aid in determining the evolution of the studied ideologies by country. Indeed, as mentioned above, the text was thoroughly analyzed by automatic means, which could give insight into the psychological factors of the text, and the motivations and ideologies of the author.

For the psychological traits, we assessed the analysis provided by the Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count (LIWC) resource [84]. LIWCwas used in previous words to study the radicalization phenomena. As an exciting example, it was used to analyze political posts on Twitter to find a relation between them and the results of a political election [85]. Additionally, Hall et al. [86] studied the quality of the LIWC annotations for ISIS-related messages, obtaining promising results.

The LIWC algorithm performs a word count that elicits emotions, psychological meanings, or social concerns in a text. Thus, the process leverages a dictionary that compiles an exhaustive list of words and their possible inflections, classifying them (e.g., anxiety, anger, family, religion). Consequently, every category present in the text is given a score corresponding to the number of words found that belong to that category. As an example, if a sentence contains the word “father,” which is classified by the dictionary as “family” and “male reference,” then both of these categories will have a resulting score of one. Alternatively, if the word “cousin,” which is also a reference to “family,” also appears in the text, then the “family” category would obtain a score of two.

The categories measured by LIWC are grouped in sets depending on the psychological process they are describing. Four of them are taken into account for this analysis: drives, affective, personal concerns, and social. The “Drives” set gives insight into the motivations of the person behind the text. It measures five parameters: affiliation, achievement, power, reward, and risk. Feelings such as anxiety, anger, sadness, or positive and negative emotions are part of the “Affective Process” set. The “Personal Concerns” set measures how worried the person behind the text is about different life issues, such as work, leisure, home, money, religion, and death. Drives, affective concerns, and personal concerns are considered the three main psychological variables and have been used as a reference to analyze radical discourses before [57]. The “Social Process” set was also included to provide some more information about references to family, friends, and and female and male authority figures.

The LIWC dictionary is composed of 2290 words and word stems [9]. Each word or word-stem defines one or more word category or subdictionary. The LIWC categories are arranged hierarchically. For example, by definition, all anger words will be categorized as negative emotion and overall emotion words. The obtained result enriches and contextualizes the input textual data, offering a detailed analysis covering emotions, thinking styles, social concerns, and personal drivers.

Following, the Moral Foundations Theory (MFT) [24] was modeled and included in the intelligent engine, allowing users to study such a complex phenomenon automatically. The MFT expresses the psychological basis of morality in terms of innate intuitions, defining the following five foundations [60,87]. Although recent, MFT is the most established theory in psychology and the social sciences [88]. It is also widely adopted in computational social science. It defines a clear taxonomy of values and a dictionary of terms, the Moral Foundations Dictionary (MFD) [24], an essential resource for NLP applications.

In this task, we adopted the use of the MFD, analyzing the text messages and extracting their expressed moral values. The MFD is used through the LIWC tool, which facilitates text processing. In this way, we process the moral value annotations similarly as described above.

The MFD was developed to operationalize moral values in the text. This dictionary provides information on the proportions of virtue and vice words for each moral foundation on a corpus of text [24]. It comprises 336 words and word stems categorized in the five moral dimensions. All moral dimensions were extracted from text, and their results were aggregated to compose a unified view of the data.

For this paper, the intelligent engine aggregated the scores obtained for all the relevant categories and presented the results according to the corresponding ideology and narrative. The message’s scores were normalized using the total number of words. In order to aggregate the multiple messages collected, the arithmetic mean was calculated for all the LIWC values of the same category for every ideology and narrative. For a given message, the final score was computed using the following expression:

with C being the set of possible categories, an element of C, the number of words in the message, and the score given to the words that belong to .

4.4. Dashboard

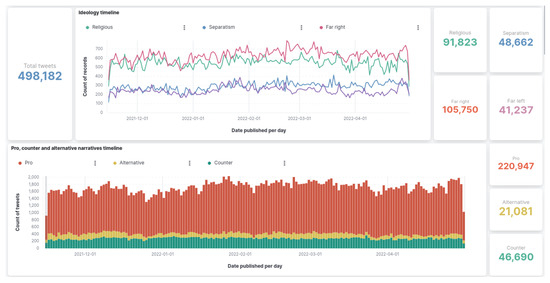

To illustrate the visualization of results in the developed dashboard, an overview is presented in the following figures. The complete dashboard is available online [89]. Figure 8 shows that the temporal charts comparing the tweets collected per ideology and narrative in the same graph, which allows users to visualize temporal patterns. As in the rest of the dashboard, these data can be filtered using a simple interface to study particular subselections.

Figure 8.

Overview of the interface. Part I. Time series.

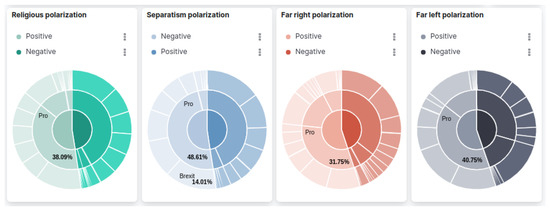

Additionally, the graphs shown in Figure 9 and Figure 10 are separated into a column for each monitored ideology. This design decision was made to contrast the analysis results in a compact dashboard. Figure 9 shows a visualization that summarizes how the polarity of the messages is distributed by ideologies (separated in columns), narratives (second level of the colored wheels), and hashtags (outer level of the wheels). Clicking in any of these elements will filter the data, thereby detailing the visualization.

Figure 9.

Overview of the interface. Part II. Pie charts.

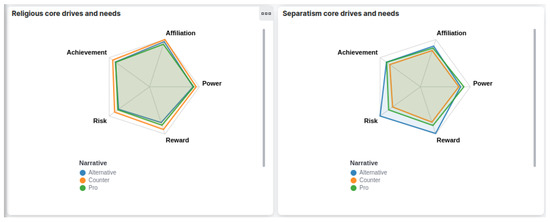

Figure 10.

Overview of the interface. Part III. Spider charts.

Similarly, Figure 10 shows an alternative visualization that summarizes LIWC’s core drives and needs present in the religious and separatism ideologies. The measures are separated by narrative and are used to explore differences among ideologies and narratives. Concretely, this kind of chart allows users to detect spikes in code drives and needs, thereby complementing the rest of the dashboard.

5. Results and Evaluation

This section describes the outcomes of the implemented solution. The toolkit has been developed to analyze and compare the radical and extremist narratives of the selected ideologies. Therefore, we provide a SPARQL endpoint to perform complex semantic queries and a dashboard to visualize the results. First, a set of semantic queries are introduced. Then, the results are analyzed to narrate the findings and provide a direction to the discussion of the research work. Finally, we present a discussion where we compare the presented work with previous literature.

5.1. Analysis of Results

Data analytics requires complex processes for gaining insight into hidden patterns and correlations in datasets. Typically, a large dataset is required to reveal such patterns. In this regard, to demonstrate the possibilities of the intelligent engine and its associated data, we show some statistics that may aid in obtaining a further understanding of the underlying patterns in the data. Therefore, we have captured and analyzed the tweets listed in Table 3. This table shows the distribution of tweets according to the ideology and narrative. It is noticeable in the distribution that there is a difference in the sizes of the extracted data. The reasons are that some narratives have more variety of hashtags associated with them, and specific hashtags are more popular than others.

Table 3.

Tweets are captured by ideology and narrative.

On the other hand, geographic data indicate that 76.89% of the total tweets had a location field. As we used the MFT and LIWC dictionaries in English and German, tweets that are not in those languages were filtered out.

5.2. Evaluation

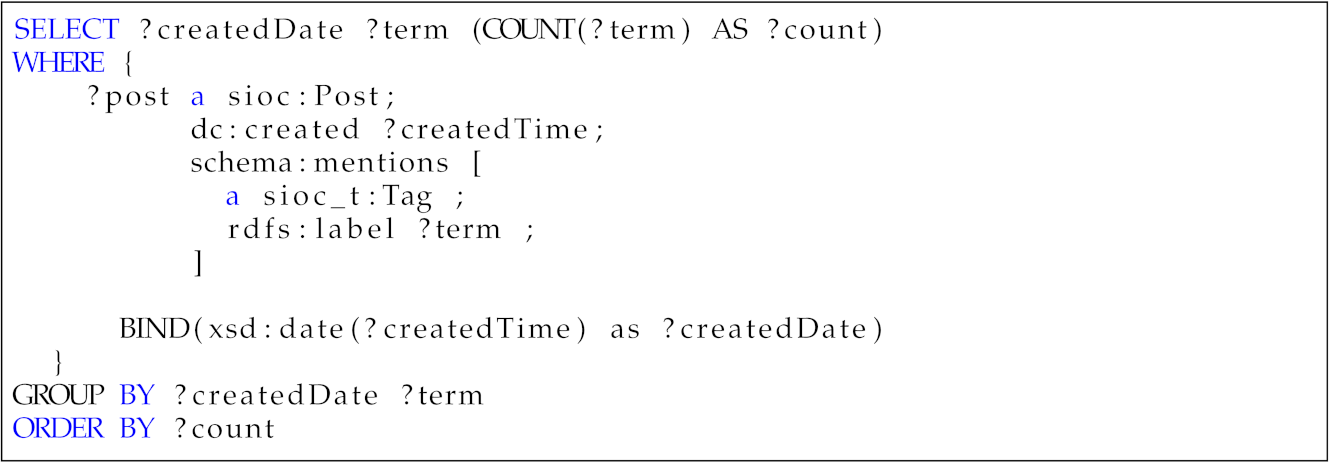

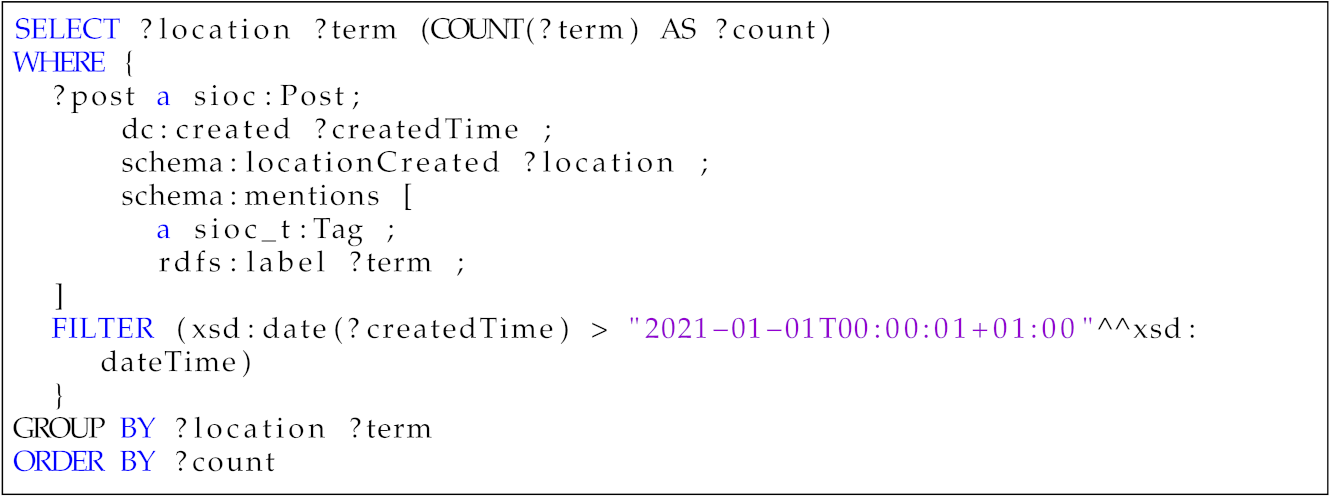

In order to evaluate the monitoring system, a set of competency questions was defined to check its query capabilities. Ontology questions are a widely-usage method to define and evaluate an ontology’s requirements in the form of questions the ontology must be able to answer [90]. Table 4, Table 5, Table 6 and Table 7 show these queries, their formulations based on SPARQL queries, and the obtained results. The queries were designed by a multidisciplinary team based on the central questions a social scientist is interested in:

- 1.

- Which is the most popular term in two different moments in time? A relevant insight into a community is the topics its addresses. Generally, online discussions can vary between different topics over time. This question was designed to uncover temporal trends of the topics discussed in the data. Moreover, we could also be interested in monitoring the temporal evolution of certain topics.

Table 4. Competency question—Q1.Table 4. Competency question—Q1.

Table 4. Competency question—Q1.Table 4. Competency question—Q1.SPARQL Query Results Which is the most popular term in two different moments in time?

?createdDate ?term ?count 26-02-2022 Ukraine 23,010 03-02-2022 USA 19,926 - 2.

- Which are the leading core drivers in a given area? Core drivers are psychological traits that the proposed system can extract from the analyzed text. Since we studied geolocated content, it was possible to study specific areas and how they address personal and ingroup narratives. The study of how a community expresses its core drives can aid in describing the said community.

Table 5. Competency question—Q2.Table 5. Competency question—Q2.

Table 5. Competency question—Q2.Table 5. Competency question—Q2.Which are the leading personal concerns in a given area?

?location ?term ?count Berlin, Germany Risk 8923 Hamburg, Germany Achievement 7332 Washington, DC Affiliation 2349 - 3.

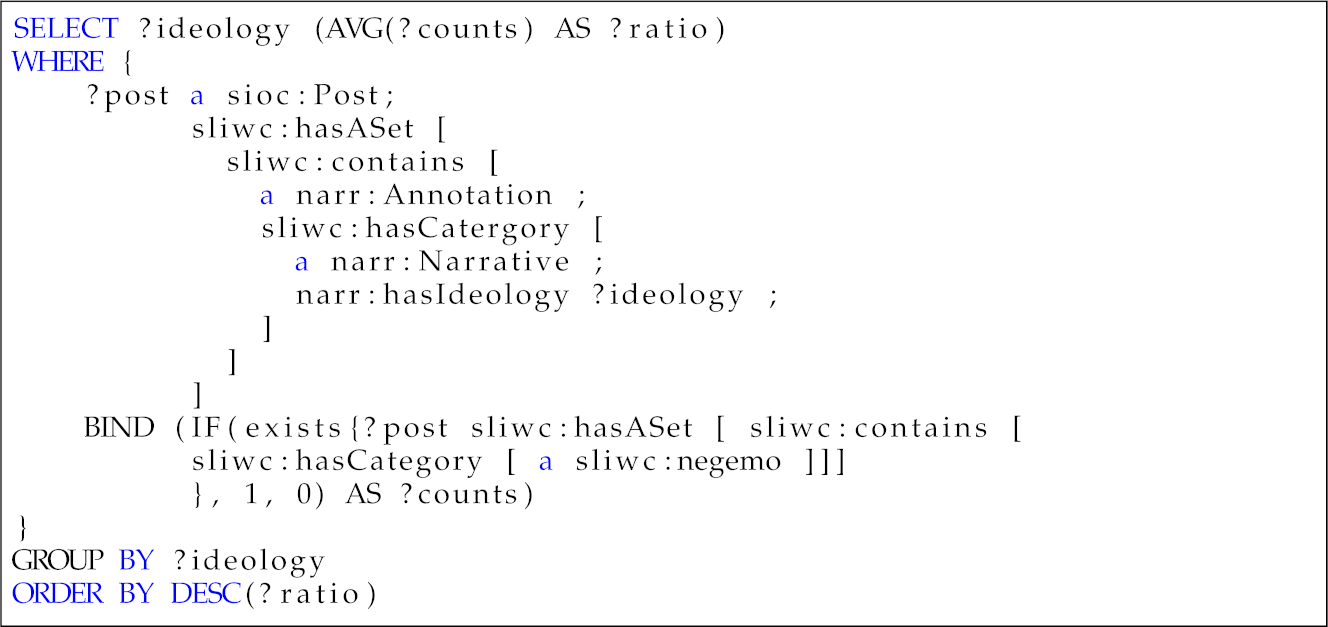

- Which is the ideology with a higher percentage of polarized content? Polarization in extremist or propagandistic content is a common trait. Thus, it is an interesting characteristic to study. This question is oriented to characterizing the language of each ideology, profiling the percentage of negative polarization overall.

Table 6. Competency question—Q3.Table 6. Competency question—Q3.

Table 6. Competency question—Q3.Table 6. Competency question—Q3.Which is the ideology with a higher percentage of polarized content?

?ideology ?ratio Separatism 0.5232 Religious 0.4745 Far-left 0.4476 Far-right 0.4463 - 4.

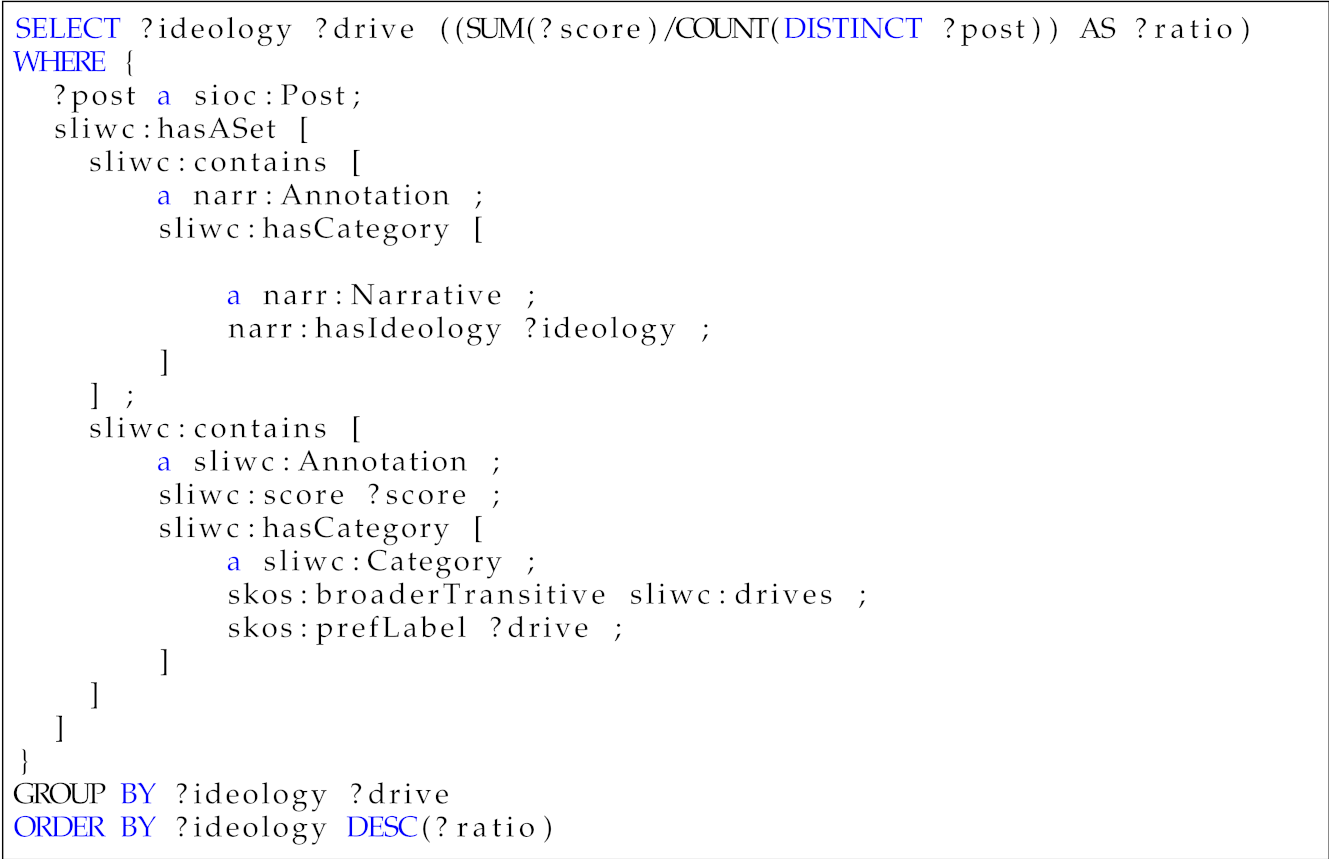

- Which core drive is the most prevalent in each ideology? As mentioned, core drives are an effective way of profiling language use. This question was aimed at profiling the most important core drivers among the different ideologies considered. This offers an insight into the motivation of the language used in the messages of each ideology.

Table 7. Competency question—Q4.Table 7. Competency question—Q4.

Table 7. Competency question—Q4.Table 7. Competency question—Q4.Which core drive is the most prevalent in each ideology?

?ideology ?drive ?ratio Religious Affiliation 0.35 Separatism Achievement 0.35 Far right Power 0.32 Far left Power 0.33

5.3. Discussion

The previous evaluation showed the utility of the presented system and the framework it enables. In this way, we have demonstrated how the semantic modeling combined with a complete NLP and data processing pipeline allows for discovering complex patterns in relation to radicalization and extremism in social media. It is this semantic modeling that allows users to define ad hoc queries that can adapt to complicated necessities from social science actors.

Attending to the previous literature, the Hatemeter system [91] stands as a complete system that monitors anti-Muslim content in social networks. Hatemeter made use of an Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) network to perform text classification in the domain of anti-Muslim content. Additionally, Hatemeter has a network-oriented interface, exploring the relations between monitored users. In comparison, the system presented in this paper is language-oriented, as it explores patterns in the linguistic data. Additionally, our system makes use of popular lexical resources (LIWC, MFT) to analyze language, offering a domain-agnostic view of the language and its use.

Another relevant system for monitoring social media is Contro L’Odio [35], which monitors and contrasts discrimination and hate speech in Italy. This platform also has several visualizations that allow a user to reduce the complexity of the data. As in our system, Contro L’Odio offers a geographical visualization that relates locations and their own language trends.

The platform of the project Trivalent [38] was designed for law enforcement agencies to monitor social media in the context of jihadist extremism. While Trivalent’s platform monitors news and online magazines, the presented system has a focus on social media. Additionally, our system has complete language analysis that, as described, includes several lexical resources.

As described in Section 4.1, the proposed intelligent engine has a modular architecture that has been implemented using a micro-services fashion. This, of course, would allow us to extend the original functionalities with additional modules that can be added to the data model through the presented semantic modeling. An interesting example will be to extend the presented system with text classification capabilities, such as radicalization or extremism detection. In this line of work, previous studies have used deep learning models, such as word embeddings [10,92] and several neural architectures [93,94]. Recent advances in NLP learning methods have used the transformer architecture [95], which has been applied to hate speech and similar content [96]. These mentioned approaches can be easily added to the intelligent engine due to the presented architecture and its corresponding semantic modeling.

6. Conclusions

This paper presents the work to develop an intelligent engine to detect radicalization in youth. Such efforts revolve around the following objectives: (i) the development of an orchestrated intelligent platform that captures, processes, and stores data from social networks; (ii) the development of several text analysis methods for contextualizing and enriching the captured data; (iii) the generation of several semantic vocabularies that allow the semantic modeling of the captured data and their corresponding analyses; and (iv) the development of a visualization dashboard that allows users to gain insights into the produced data, follow trends in the data, and perform complex queries. The efforts in this work have produced a complete big data system that exploits several linguistic analysis methods and the full potential of semantic modeling, offering users a complete yet straightforward graphical interface for interacting with the data.

The mentioned intelligent platform has been developed and deployed for its use in future work. For example, it can monitor recruitment and propaganda campaigns. Interoperability and extensibility are fundamental principles followed during the development phase. Such a design enables third parties to use the data extracted by our tools rapidly.

Several efforts have been made concerning modeling the data, its analyses, and visual representations. These novel advances have brought the semantic modeling of a known resource in the NLP context: the LIWC dictionary. Such representations can be used jointly with other annotations, thereby facilitating their replication. In addition, in this task, the MFT concepts have also been modeled using semantic representations. The advances in visualization and querying technologies allow domain experts to quickly detect patterns in the captured data using standard web technologies, facilitating their use.

It is of particular relevance to the work done in relation to RQ1 (What are the main linguistic signals that reveal radicalization factors?). As detailed in Section 2, a large number of studies on radicalization drivers have been addressed as computational radicalization signals. The proposed system covers a number of these approaches, showing its utility in a real-world scenario.

Additionally, this work presented several novel semantic vocabularies used throughout the presented system. More concretely, this paper presented the (i) Senpy Ontology vocabulary (SENPY), (ii) Semantic LIWC (SLIWC) vocabulary, (iii) Morality vocabulary, and (iv) Narrative vocabulary. In this way, our system is able to semantically model radicalization and extremist processes with a focus on language.

This work aims at providing a pathway between traditional and computational social science. Traditionally, the primary data sources for radicalization analysis are focus groups and interviews with experts, police forces, or convicted terrorists and extremists. As a result, the sample size is usually small. In contrast, social data analysis allows the analysis of large quantities of messages and interactions. This work can help social scientists to complement their studies in several ways. First, our system can be used for analyzing a specific event in a specific region, which can complement the analysis of specific cases. In addition, an interesting aspect that can be analyzed is the temporal evolution in the radicalization processes. Understanding this evolution can help with designing better counter-radicalization strategies. Finally, automated text analytics can help gain insights into radicalism’s drivers and roots. To this end, this work provides complementary text analytics, such as sentiment and emotion analysis, social-psychological analysis, and moral foundations analysis. Social scientists can benefit from these analyses to better understand the processes and interactions of radicalization factors.

Regarding future work, we believe that adding new sources of information (e.g., Reddit and Facebook) would be an interesting path which would allow users to compare linguistic patterns across different social media. Additionally, the platform could be extended to perform radicalization or propaganda detection, thereby further contextualizing the captured text. We believe that the presented platform, taking into account its semantic characteristics, will foster research for social sciences.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.Á.I. and Ó.A.; Methodology C.Á.I., Ó.A., J.F.S.-R. and Á.C.; Software, G.G.-G., J.T. and J.F.S.-R.; Validation, G.G.-G., J.T., J.F.S.-R. and Á.C.; Investigation, C.Á.I., Ó.A., J.F.S.-R. and Á.C.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, C.Á.I., Ó.A., J.F.S.-R. and Á.C.; Writing—Review and Editing, C.Á.I., Ó.A., J.F.S.-R. Á.C., F.A. and S.M.; Project Administration, C.Á.I., Ó.A., F.A. and S.M.; Funding Acquisition, F.A., S.M. and C.Á.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under grant agreement 962547; this research was part of the project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| API | Application Programming Interface |

| DCMI | Dublin Core Metadata Initiative |

| FBI | Federal Bureau of Investigation |

| ISIS | Islamic State of Iraq and Syria |

| JSON | JavaScript Object Notation |

| JSON-LD | JavaScript Object Notation (JSON) for Linked Data |

| LIWC | Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count |

| MFD | Moral Foundations Dictionary |

| NBDRA | NIST Big Data Reference Architecture |

| NGO | Non-governmental organization |

| MFD | Moral Foundations Dictionary |

| MFT | Moral Foundations Theory |

| NIF | NLP Interchange Format |

| NLP | Natural Language Processing |

| RDF | Resource Description Framework |

| RDFS | Resource Description Framework Schema |

| SENPY | The Senpy Ontology |

| SIOC | Semantically-Interlinked Online Communities |

| SKOS | Simple Knowledge Organization System |

| SLIWC | Semantic LIWC |

| SPARQL | SPARQL Protocol and RDF Query Language |

| TF-IDF | term frequency-inverse document frequency |

| USSS | United States Secret Service |

References

- Vidino, L. Countering Radicalization in America Lessons from Europe; Technical report; US Institute of Peace: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- H2020 PARTICIPATION Project. Available online: https://participation-in.eu/ (accessed on 13 July 2022).

- Poggi, I.; D’Errico, F. Social signals: A psychological perspective. In Computer Analysis of Human Behavior; Springer: London, UK, 2011; pp. 185–225. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Rada, J.F.; Iglesias, C.A. Social context in sentiment analysis: Formal definition, overview of current trends and framework for comparison. Inf. Fusion 2019, 52, 344–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa, D.; Sureka, A. Solutions to detect and analyze online radicalization: A survey. arXiv 2013, arXiv:1301.4916. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez, M.; Asif, M.; Alani, H. Understanding the Roots of Radicalisation on Twitter. In Proceedings of the 10th ACM Conference on Web Science (WebSci ’18), Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 27–30 May 2018; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Saif, H.; Dickinson, T.; Kastler, L.; Fernandez, M.; Alani, H. A semantic graph-based approach for radicalisation detection on social media. In Proceedings of the European Semantic Web Conference, Portorož, Slovenia, 28 May–1 June 2017; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 571–587. [Google Scholar]

- Nouh, M.; Nurse, J.R.; Goldsmith, M. Understanding the radical mind: Identifying signals to detect extremist content on twitter. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Intelligence and Security Informatics (ISI), Shenzhen, China, 1–3 July 2019; pp. 98–103. [Google Scholar]

- Tausczik, Y.R.; Pennebaker, J.W. The Psychological Meaning of Words: LIWC and Computerized Text Analysis Methods. J. Lang. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 29, 24–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araque, O.; Iglesias, C.A. An approach for radicalization detection based on emotion signals and semantic similarity. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 17877–17891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Brunt, B.; Murphy, A.; Zedginidze, A. An exploration of the risk, protective, and mobilization factors related to violent extremism in college populations. Violence Gend. 2017, 4, 81–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, M. Mass Shooters and Murderers: Motives and Paths; NetCE: Mount Laurel, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Simons, A.; Meloy, J.R. Foundations of threat assessment and management. In Handbook of Behavioral Criminology; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 627–644. [Google Scholar]

- Meloy, J.R. Identifying warning behaviors of the individual terrorist. FBI Law Enforc. Bull. 2016, 85, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Hamlett, L.E. Common Psycholinguistic Themes in Mass Murderer Manifestos. Ph.D. Thesis, Walden University, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Knoll, J.L. The “pseudocommando” mass murderer: Part II, the language of revenge. J. Am. Acad. Psychiatry Law Online 2010, 38, 263–272. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, K.; Johansson, F.; Kaati, L.; Mork, J.C. Detecting linguistic markers for radical violence in social media. Terror. Political Violence 2014, 26, 246–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grover, T.; Mark, G. Detecting potential warning behaviors of ideological radicalization in an alt-right subreddit. In Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, Münich, Germany, 11–14 June 2019; Volume 13, pp. 193–204. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, G.A. WordNet: A lexical database for English. Commun. ACM 1995, 38, 39–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakayama, H. Hatesonar. Hate Speech Detection Library for Python. 2020. Available online: https://pypi.org/project/hatesonar/ (accessed on 13 July 2021).

- Torregrosa, J.; Panizo-Lledot, Á.; Bello-Orgaz, G.; Camacho, D. Analyzing the relationship between relevance and extremist discourse in an alt-right network on Twitter. Soc. Netw. Anal. Min. 2020, 10, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutto, C.; Gilbert, E. Vader: A parsimonious rule-based model for sentiment analysis of social media text. In Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1–4 June 2014; Volume 8. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, L.G.; Wakeford, L.; Cribbin, T.F.; Barnett, J.; Hou, W.K. Detecting psychological change through mobilizing interactions and changes in extremist linguistic style. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 108, 106298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, J.; Haidt, J.; Nosek, B.A. Liberals and conservatives rely on different sets of moral foundations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 96, 1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torregrosa, J.; Thorburn, J.; Lara-Cabrera, R.; Camacho, D.; Trujillo, H.M. Linguistic analysis of pro-isis users on twitter. Behav. Sci. Terror. Political Aggress. 2020, 12, 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh, M.; Weber, I.; Cioffi-Revilla, C.; Fortunato, S.; Macy, M. Psychology and morality of political extremists: Evidence from Twitter language analysis of alt-right and Antifa. EPJ Data Sci. 2019, 8, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara-Cabrera, R.; Pardo, A.G.; Benouaret, K.; Faci, N.; Benslimane, D.; Camacho, D. Measuring the radicalisation risk in social networks. IEEE Access 2017, 5, 10892–10900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Vegt, I.; Mozes, M.; Kleinberg, B.; Gill, P. The Grievance Dictionary: Understanding threatening language use. Behav. Res. Methods 2021, 53, 2105–2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pais, S.; Tanoli, I.; Albardeiro, M.; Cordeiro, J. A Lexicon Based Approach to Detect Extreme Sentiments. In Proceedings of the ICIMP 2020, the Fifteenth International Conference on Internet Monitoring and Protection; Pais, S., Tanoli, I.K., Eds.; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Baccianella, S.; Esuli, A.; Sebastiani, F. Sentiwordnet 3.0: An enhanced lexical resource for sentiment analysis and opinion mining. In Proceedings of the Lrec, Valletta, Malta, 17–23 May 2010; Volume 10, pp. 2200–2204. [Google Scholar]

- Cambria, E.; Li, Y.; Xing, F.Z.; Poria, S.; Kwok, K. SenticNet 6: Ensemble application of symbolic and subsymbolic AI for sentiment analysis. In Proceedings of the 29th ACM International Conference on Information & Knowledge Management, Galway, Ireland, 19–23 October 2020; pp. 105–114. [Google Scholar]

- Artificial Intelligence Lab, Management Information Systems Department, University of Arizona. Ansar1 Forum Dataset. Dataset of the Dark Web Project on the Study of International Jihadi Social Media and Movement. 2010. Available online: https://www.azsecure-data.org/dark-web-forums.html (accessed on 13 July 2021).

- Artificial Intelligence Lab, Management Information Systems Department, University of Arizona. Turn to Islam Forum Dataset. Dataset of the English Language Forum with the Goal of “Correcting the Common Misconceptions about Islam”. Radical Participants May Occasionally Display Their Support for Fundamentalist Militant Groups. 2013. Available online: https://www.azsecure-data.org/dark-web-forums.html (accessed on 13 July 2021).

- Wahyuningsih, T. Problems, Challenges, and Opportunities Visualization on Big Data. J. Appl. Data Sci. 2020, 1, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capozzi, A.T.; Lai, M.; Basile, V.; Poletto, F.; Sanguinetti, M.; Bosco, C.; Patti, V.; Ruffo, G.; Musto, C.; Polignano, M.; et al. “Contro L’Odio”: A Platform for Detecting, Monitoring and Visualizing Hate Speech against Immigrants in Italian Social Media. IJCoL Ital. J. Comput. Linguist. 2020, 6, 77–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Nicola, A.; Andreatta, D.; Martini, E.; Antonopoulos, G.; Baratto, G.; Bonino, S.; Bressan, S.; Burke, S.; Cesarotti, F.; Diba, P.; et al. HATEMETER: Hate Speech Tool for Monitoring, Analysing and Tackling Anti-Muslim Hatred Online. eCrime; Technical Report; Commissioning bodyEuropean Union’s Rights, Equality and Citizenship Programme: Trento, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Laurent, M. Project Hatemeter: Helping NGOs and Social Science researchers to analyze and prevent anti-Muslim hate speech on social media. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2020, 176, 2143–2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H2020 Trivalent Project. Terrorism pReventIon Via rAdicaLisation countEr-NarraTive. Available online: http://trivalentproject.eu/ (accessed on 13 July 2022).

- Beheshti, A.; Moraveji-Hashemi, V.; Yakhchi, S.; Motahari-Nezhad, H.R.; Ghafari, S.M.; Yang, J. personality2vec: Enabling the analysis of behavioral disorders in social networks. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining, Houston TX, USA, 3–7 February 2020; pp. 825–828. [Google Scholar]

- Chiarcos, C.; McCrae, J.; Cimiano, P.; Fellbaum, C. Towards open data for linguistics: Linguistic linked data. In New Trends of Research in Ontologies and Lexical Resources; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 7–25. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Rada, J.F.; Iglesias, C.A. Onyx: A Linked Data Approach to Emotion Representation. Inf. Process. Manag. 2016, 52, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auer, S.; Bryl, V.; Tramp, S. Linked Open Data–Creating Knowledge Out of Interlinked Data: Results of the LOD2 Project; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; Volume 8661. [Google Scholar]

- Buitelaar, P.; Wood, I.D.; Negi, S.; Arcan, M.; McCrae, J.P.; Abele, A.; Robin, C.; Andryushechkin, V.; Ziad, H.; Sagha, H.; et al. Mixedemotions: An open-source toolbox for multimodal emotion analysis. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2018, 20, 2454–2465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breslin, J.G.; Decker, S.; Harth, A.; Bojars, U. SIOC: An approach to connect web-based communities. Int. J. Web Based Communities 2006, 2, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dublin Core Metadata Initiative. Dublin Core Metadata Element Set, Version 1.1; Technical report; Dublin Core Metadata Initiative: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Auer, S.; Bizer, C.; Kobilarov, G.; Lehmann, J.; Cyganiak, R.; Ives, Z. Dbpedia: A Nucleus for a Web of Open Data. In The Semantic Web; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2007; pp. 722–735. [Google Scholar]

- Hellmann, S.; Lehmann, J.; Auer, S.; Brümmer, M. Integrating NLP Using Linked Data. In Proceedings of the International Semantic Web Conference, Sydney, Australia, 21–25 October 2013; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 98–113. [Google Scholar]

- Westerski, A.; Iglesias, C.A.; Rico, F.T. Linked Opinions: Describing Sentiments on the Structured Web of Data. In Proceedings of the SDoW@ ISWC, Bonn, Germany, 23–27 October 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Barhamgi, M.; Masmoudi, A.; Lara-Cabrera, R.; Camacho, D. Social networks data analysis with semantics: Application to the radicalization problem. J. Ambient. Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 2018, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SLIWC. Semantic LIWC vocabulary. Available online: https://www.gsi.upm.es/ontologies/participation/sliwc/ (accessed on 13 July 2022).

- Morality Vocabulary. Available online: https://www.gsi.upm.es/ontologies/participation/morality/ (accessed on 13 July 2022).

- Narrative Vocabulary. Available online: https://www.gsi.upm.es/ontologies/participation/narrative/ (accessed on 13 July 2022).

- Sánchez-Rada, J.F.; Araque, O.; Iglesias, C.A. Senpy: A Framework for Semantic Sentiment and Emotion Analysis Services. Knowl. Based Syst. 2020, 190, 105193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebo, T.; Sahoo, S.; McGuinness, D.; Belhajjame, K.; Cheney, J.; Corsar, D.; Garijo, D.; Soiland-Reyes, S.; Zednik, S.; Zhao, J. PROV-O: The PROV Ontology; W3C Recommendation, World Wide Web Consortium: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pennebaker Conglomerates, I. Comparing LIWC2015 and LIWC2007. 2021. Available online: http://liwc.wpengine.com/compare-dictionaries/ (accessed on 7 October 2021).