Automatic Classification of Crack Severity from Cross-Section Image of Timber Using Simple Convolutional Neural Network

Abstract

Featured Application

Abstract

1. Introduction

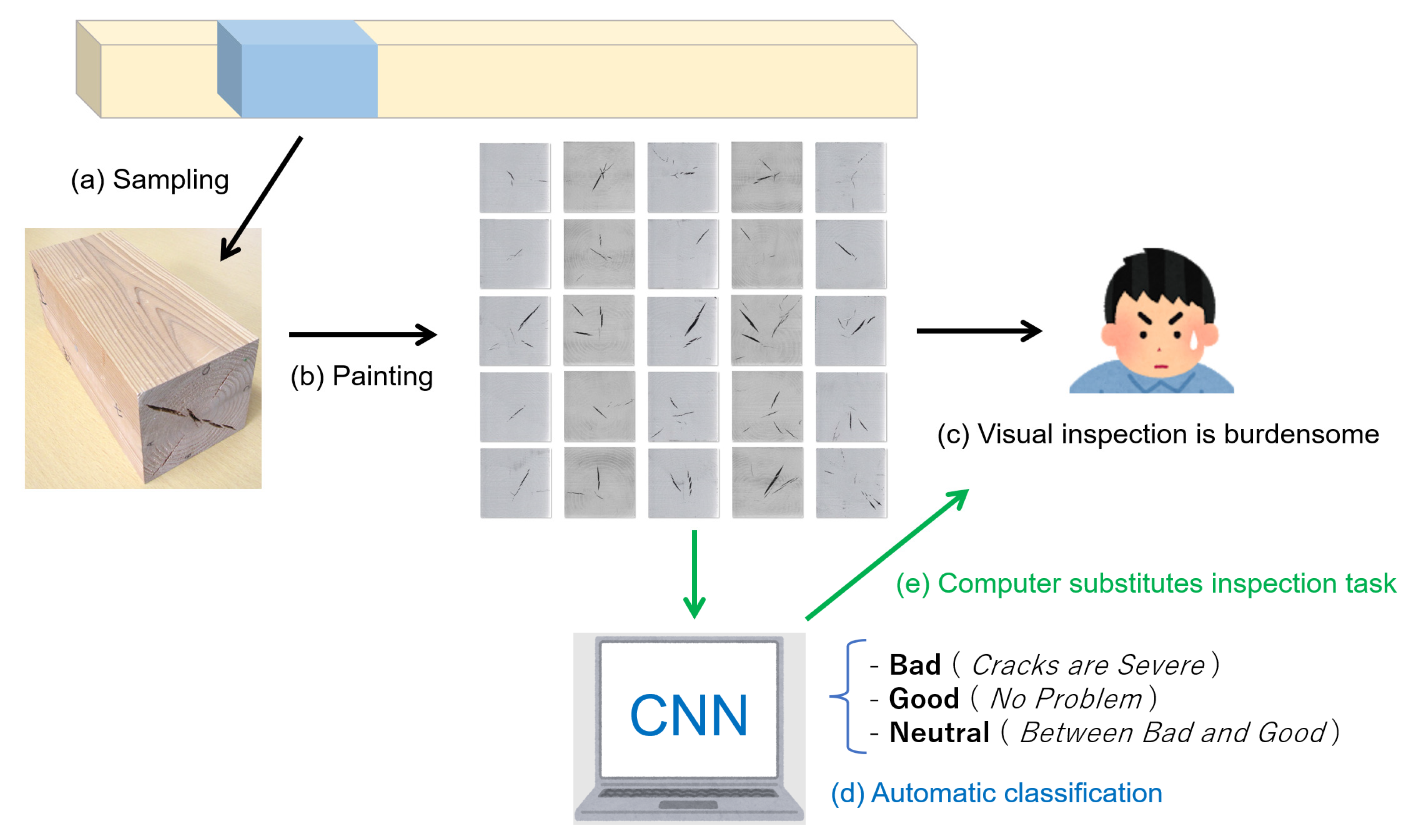

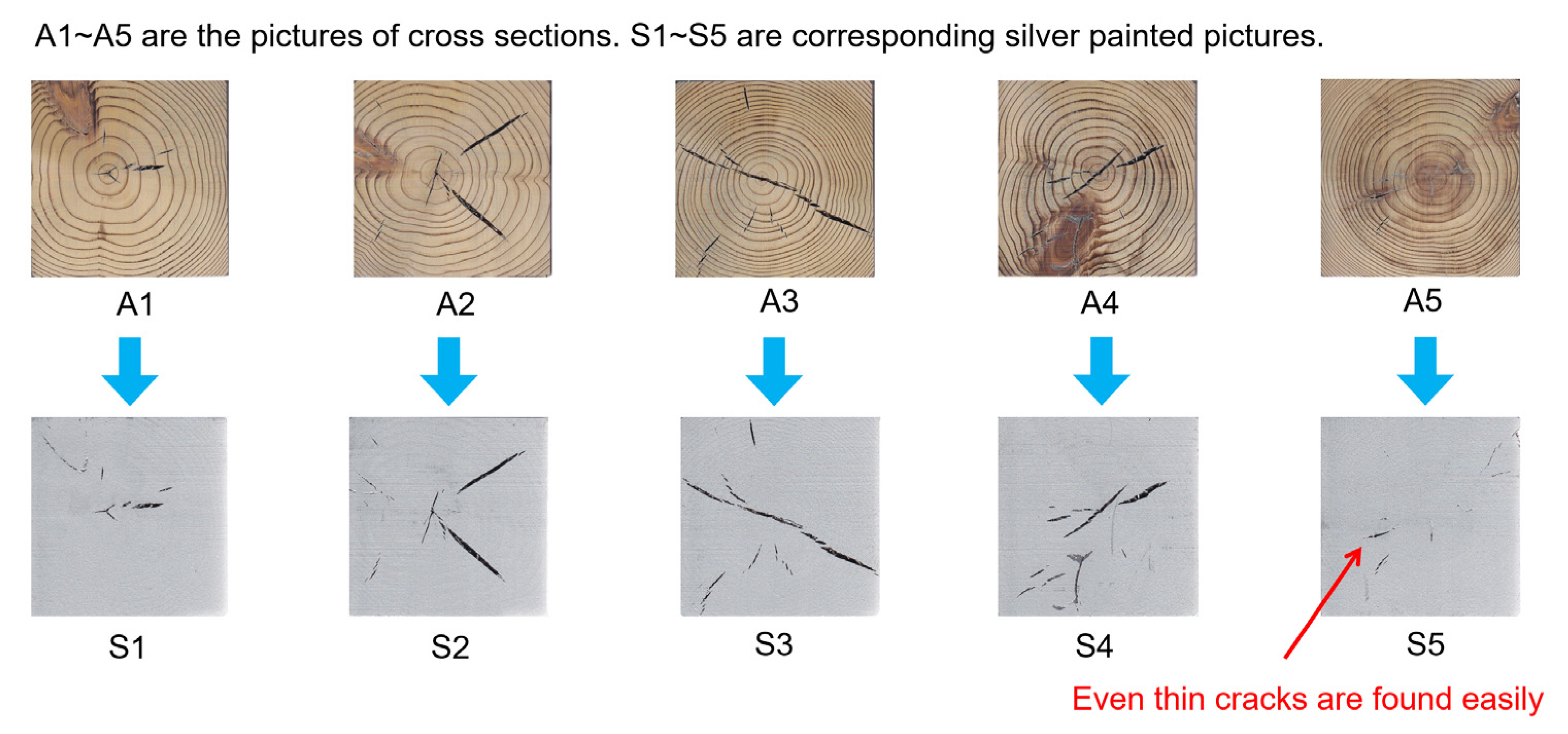

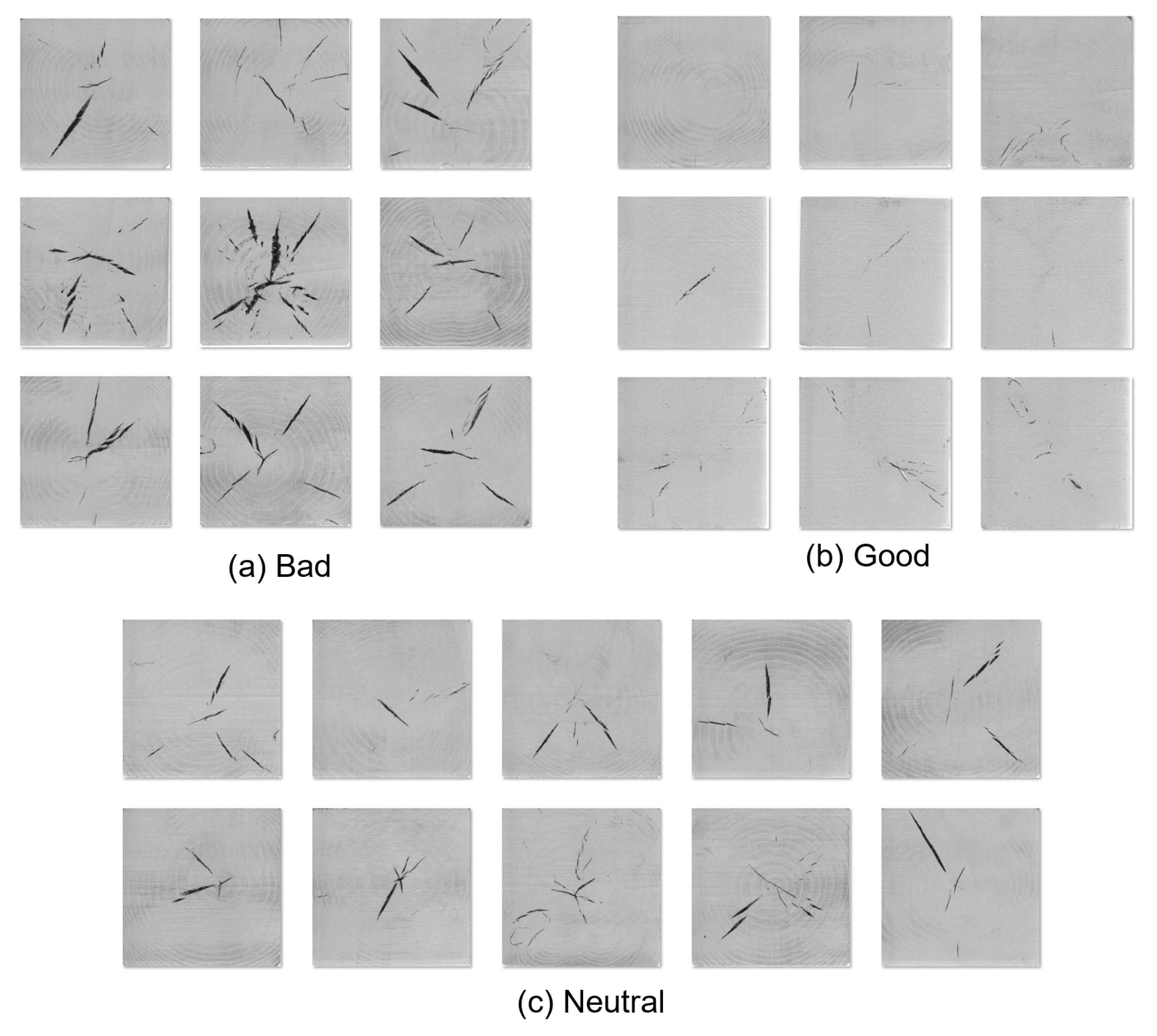

2. Preparation of Timber Cross-Section Image

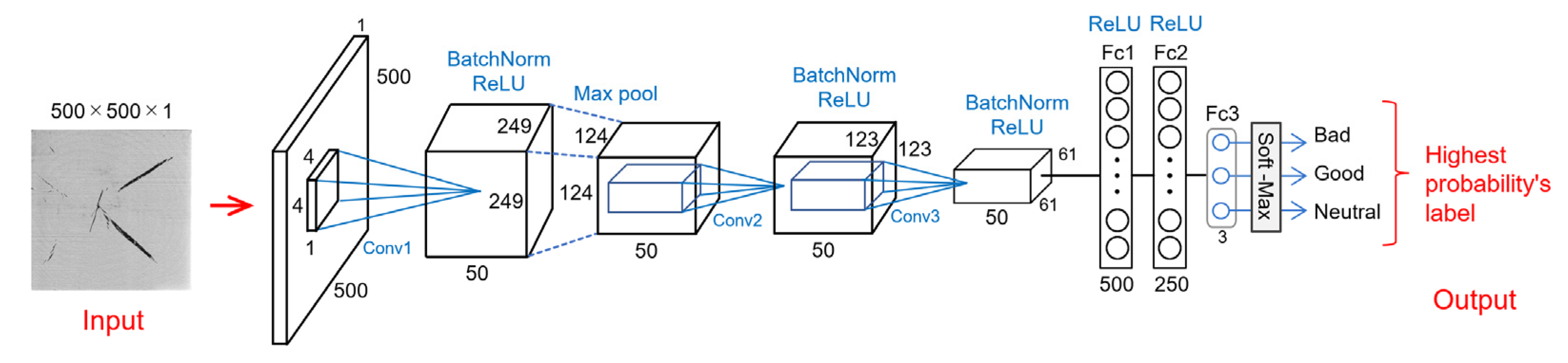

3. Simple CNN Configuration

4. Validation of the Proposed Simple CNN

4.1. Training of CNN

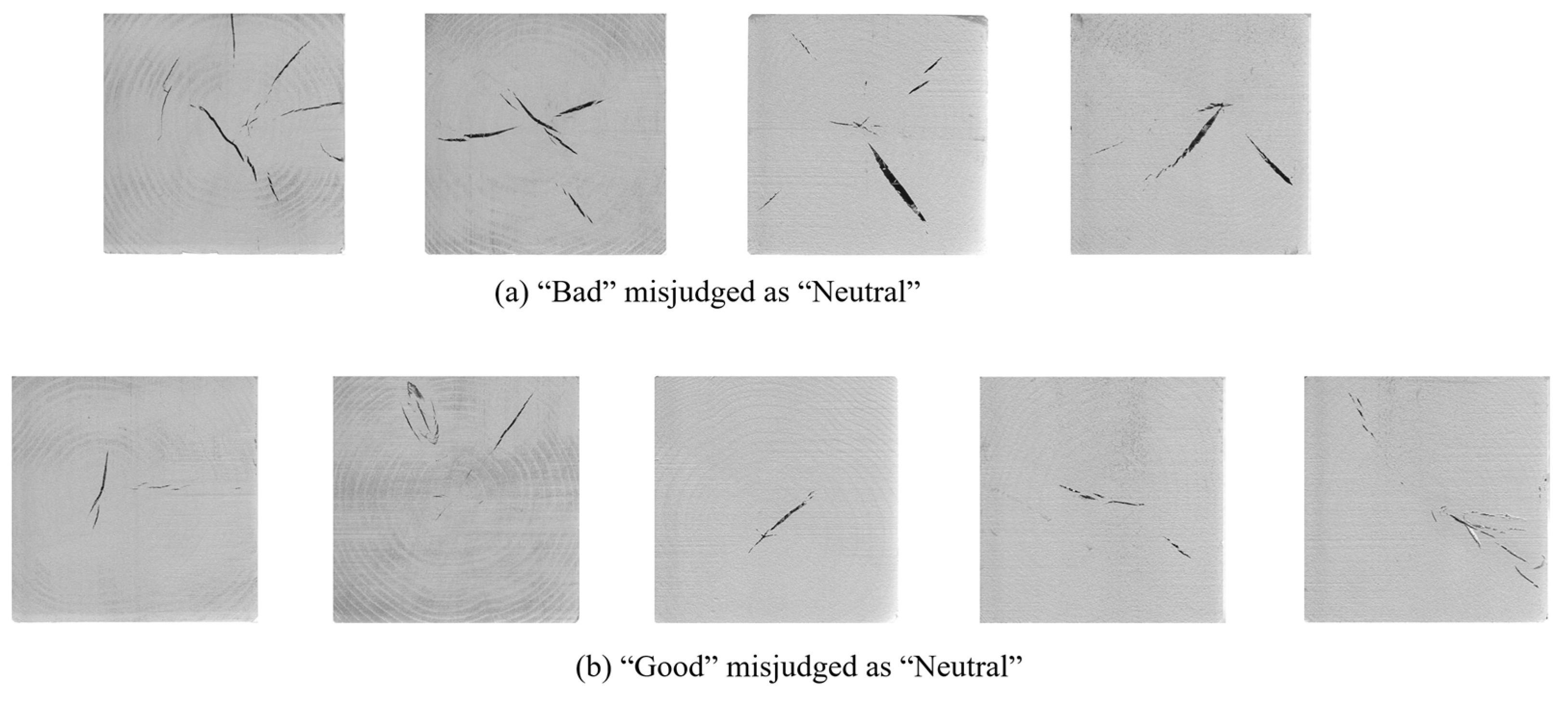

4.2. Testing the CNN

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bergman, R. Drying and Control of Moisture Content and Dimensional Changes. In Wood Handbook, Wood as an Engineering Material; USDA: Washington, DC, USA, 2021; Chapter 13; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita, K.; Hirakawa, Y.; Saito, S.; Ikeda, M.; Ohta, M. Internal-Check Variation in Boxed-Heart Square Timber of sugi (Cryptomeria japonica) Cultivars Dried by High-Temperature Kiln Drying. J. Wood Sci. 2012, 58, 375–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomita, M. Effects of Internal Checks Caused by High-Temperature Drying on Mechanical Properties of Sugi Squared Sawn Timbers: Bending Strength of Beam and Resistance of Bolted Wood-Joints. Wood Ind. 2009, 64, 416–422. [Google Scholar]

- Tonosaki, M.; Saito, S.; Miyamoto, K. Evaluation of Internal Checks in High Temperature Dried Sugi Boxed Heart Square Sawn Timber by Dynamic Shear Modulus. Mokuzai Gakkaishi 2010, 56, 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Teranishi, Y.; Kaimoto, H.; Matsumoto, H. Steam-Heated/Radio-Frequency Hybrid Drying for Sugi Boxed-Heart Timbers(1)Effect of High Temperature Setting Time on Internal Checks. Wood Ind. 2016, 72, 52–57. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, Q.; Liu, H.-H. Drying Stress and Strain of Wood: A Review. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 5023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeCun, Y.; Bottou, L.; Bengio, Y.; Haffner, P. Gradient-Based Learning Applied to Document Recognition. Proc. IEEE 1998, 86, 2278–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, S.; Wada, N.; Shiogai, K.; Tamaki, T. Evaluation of the Crack Severity in Squared Timber Using CNN. In Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems, Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Advanced Information Networking and Applications, Sydney, Australia, 13–15 April 2022; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 3, pp. 441–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakayama, S. Evaluation of Internal Checks on Boxed-Heart Structural Timber of Sugi and Hinoki Using Stress-Wave Propagation I. Effects of Moisture Content, Timber Temperature, Knots, and the Internal Check Form. J. For. Biomass Util. Soc. 2012, 7, 51–58. [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama, S.; Matsumoto, H.; Teranishi, Y.; Kato, H.; Shibata, H.; Shibata, N. Evaluation of Internal Checks on Boxed-Heart Structural Timber of Sugi and Hinoki Using Stress-Wave Propagation II. Evaluating Internal Checks of Full-Sized Timber. J. For. Biomass Util. Soc. 2013, 8, 21–27. [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama, S.; Matsumoto, H.; Teranishi, Y.; Kato, H.; Shibata, H.; Shibata, N. Evaluation of Internal Checks on Boxed-Heart Structural Timber of Sugi and Hinoki Using Stress-Wave Propagation (III) Estimation of the Length of Internal Checks in Boxed-Heart Square Timber of sugi. J. For. Biomass Util. Soc. 2013, 8, 61–65. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Hou, M.; Li, A.; Dong, Y.; Xie, L.; Ji, Y. Automatic Detection of Timber-Cracks in Wooden Architectural Heritage Using Yolov3 Algorithm. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2020, XLIII–B2, 1471–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, T.; Liu, Y.; Yu, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Hu, Z. Application of Deep Convolutional Neural Network on Feature Extraction and Detection of Wood Defects. Measurement 2020, 152, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, L.; Rogulin, R.; Kondrashev, S. Artificial Neural Network for Defect Detection in CT Images of Wood. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2021, 187, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioffe, S.; Szegedy, C. Batch Normalization: Accelerating Deep Network Training by Reducing Internal Covariate Shift. Int. Conf. Mach. Learn. 2015. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/1502.03167 (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, G.; Liu, Z.; van der Maaten, L.; Weinberger, K.Q. Densely Connected Convolutional Networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 4700–4708. [Google Scholar]

- Nair, V.; Hinton, G. Rectified Linear Units Improve Restricted Boltzmann Machines. In Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML-10), Haifa, Israel, 21–24 June 2010; pp. 807–814. [Google Scholar]

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Geoffrey, E.H. ImageNet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2012, 25, 1097–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very Deep Convolutional Networks for Large-Scale Image Recognition. arXiv 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szegedy, C.; Liu, W.; Jia, Y.; Sermanet, P.; Reed, S.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Vanhoucke, V.; Rabinovich, A. Going Deeper with Convolutions. arXiv 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzeo, P.L.; Argentieri, A.; de Luca, F.; Spagnolo, P.; Distante, C.; Leo, M.; Carcagni, P. Convolutional neural networks for recognition and segmentation of aluminum profiles, Proc. SPIE 11059. Multimodal Sens. Technol. Appl. 2019, 11059, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priddy, K.L.; Keller, P.E. Dealing with Limited Amounts of Data. In Artificial Neural Networks—An Introduction; SPIE Press: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2005; Chapter 11; pp. 101–105. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop, C.M. Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Zadeh, L.A. Fuzzy sets. Inf. Control. 1965, 8, 338–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Layer | Operation | Filters’ Set Num | Filter Size | Stride | Output |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Input | - | - | - | - | 500 × 500 × 1 |

| Conv1 | Conv->BatchNorm->ReLU | 50 | 4 × 4 × 1 | 2 × 2 | 249 × 249 × 50 |

| Max pool | Max pooling | - | 3 × 3 | 2 × 2 | 124 × 124 × 50 |

| Conv2 | Conv->BatchNorm->ReLU | 50 | 2 × 2 × 50 | 1 × 1 | 123 × 123 × 50 |

| Conv3 | Conv->BatchNorm->ReLU | 50 | 3 × 3 × 50 | 2 × 2 | 61 × 61 × 50 |

| Fc1 | Affine->ReLU | - | - | - | 500 |

| Fc2 | Affine->ReLU | - | - | - | 250 |

| Fc3 | Affine->Soft-Max | - | - | - | 3 |

| First Half | Last Half | |

|---|---|---|

| Solver | SGDM (Stochastic Gradient Descent with Momentum) | |

| Learn Rate | 10−3 | |

| Total Epochs/Iterations | 300 | 50 |

| Mini batch Size | 256 | 100 |

| Augmentation | Random Left–Right Reflection (50%), Random Top-Down Reflection (50%) | |

| Random rotation ranged in [0, 360] degree | No rotation | |

| CPU | Intel core i9 10980XE | |

| Main Memory | 98 GB | |

| OS | Windows 10 64 bit | |

| Development Language | MathWorks, MATLAB (R2022a) | |

| GPU | Nvidia RTX A6000 (VRAM 48 GB, 10752 cuda cores) | |

| Trial | Bad Image IDs for Test | Good Image IDs for Test | Neutral Image IDs for Test | Accuracy | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5 | 16 | 21 | 28 | 31 | 17 | 19 | 20 | 24 | 29 | 2 | 21 | 41 | 42 | 45 | 0.8000 |

| 2 | 22 | 32 | 33 | 42 | 45 | 5 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 17 | 6 | 18 | 19 | 30 | 46 | 1.0000 |

| 3 | 14 | 16 | 34 | 42 | 47 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 12 | 17 | 3 | 19 | 40 | 42 | 46 | 0.7333 |

| 4 | 7 | 18 | 19 | 44 | 48 | 8 | 16 | 19 | 21 | 31 | 6 | 19 | 23 | 27 | 38 | 0.8667 |

| 5 | 2 | 12 | 29 | 35 | 41 | 1 | 6 | 14 | 28 | 29 | 7 | 10 | 14 | 23 | 43 | 0.8667 |

| 6 | 4 | 9 | 13 | 16 | 49 | 7 | 12 | 27 | 31 | 33 | 3 | 5 | 27 | 28 | 41 | 1.0000 |

| 7 | 2 | 5 | 6 | 20 | 33 | 7 | 9 | 15 | 27 | 30 | 1 | 7 | 20 | 22 | 26 | 0.8000 |

| 8 | 7 | 24 | 32 | 36 | 42 | 1 | 6 | 14 | 15 | 24 | 1 | 8 | 22 | 41 | 43 | 0.9333 |

| 9 | 4 | 27 | 35 | 37 | 47 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 16 | 29 | 1 | 2 | 9 | 10 | 17 | 0.8667 |

| 10 | 30 | 33 | 39 | 43 | 48 | 5 | 7 | 8 | 13 | 14 | 3 | 8 | 11 | 21 | 30 | 0.8000 |

| 11 | 7 | 9 | 18 | 32 | 47 | 3 | 6 | 17 | 25 | 27 | 7 | 12 | 19 | 37 | 44 | 0.9333 |

| 12 | 15 | 24 | 26 | 33 | 36 | 2 | 3 | 14 | 19 | 27 | 10 | 15 | 20 | 25 | 27 | 0.9333 |

| 13 | 18 | 34 | 36 | 39 | 45 | 4 | 16 | 17 | 21 | 22 | 1 | 17 | 31 | 39 | 42 | 0.8667 |

| 14 | 25 | 26 | 29 | 39 | 48 | 2 | 5 | 6 | 15 | 18 | 3 | 4 | 12 | 31 | 37 | 0.8667 |

| 15 | 12 | 16 | 23 | 27 | 42 | 2 | 9 | 20 | 25 | 26 | 4 | 25 | 36 | 42 | 45 | 0.7333 |

| 16 | 17 | 21 | 40 | 41 | 49 | 1 | 6 | 11 | 20 | 22 | 2 | 6 | 18 | 24 | 44 | 0.8000 |

| 17 | 2 | 8 | 16 | 23 | 44 | 19 | 20 | 28 | 29 | 32 | 8 | 14 | 24 | 29 | 32 | 0.8000 |

| 18 | 17 | 18 | 21 | 32 | 40 | 18 | 23 | 30 | 32 | 33 | 10 | 20 | 22 | 26 | 33 | 0.8667 |

| 19 | 12 | 15 | 35 | 39 | 47 | 2 | 3 | 7 | 13 | 33 | 9 | 12 | 15 | 42 | 44 | 0.8667 |

| 20 | 25 | 32 | 36 | 39 | 46 | 3 | 7 | 16 | 22 | 25 | 4 | 16 | 20 | 22 | 27 | 0.8000 |

| – | – | – | – | Average: 0.8567 Std: 0.0758 | ||||||||||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kato, S.; Wada, N.; Shiogai, K.; Tamaki, T.; Kagawa, T.; Toyosaki, R.; Nobuhara, H. Automatic Classification of Crack Severity from Cross-Section Image of Timber Using Simple Convolutional Neural Network. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 8250. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12168250

Kato S, Wada N, Shiogai K, Tamaki T, Kagawa T, Toyosaki R, Nobuhara H. Automatic Classification of Crack Severity from Cross-Section Image of Timber Using Simple Convolutional Neural Network. Applied Sciences. 2022; 12(16):8250. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12168250

Chicago/Turabian StyleKato, Shigeru, Naoki Wada, Kazuki Shiogai, Takashi Tamaki, Tomomichi Kagawa, Renon Toyosaki, and Hajime Nobuhara. 2022. "Automatic Classification of Crack Severity from Cross-Section Image of Timber Using Simple Convolutional Neural Network" Applied Sciences 12, no. 16: 8250. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12168250

APA StyleKato, S., Wada, N., Shiogai, K., Tamaki, T., Kagawa, T., Toyosaki, R., & Nobuhara, H. (2022). Automatic Classification of Crack Severity from Cross-Section Image of Timber Using Simple Convolutional Neural Network. Applied Sciences, 12(16), 8250. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12168250