Residual-Attention UNet++: A Nested Residual-Attention U-Net for Medical Image Segmentation

Abstract

:1. Introduction

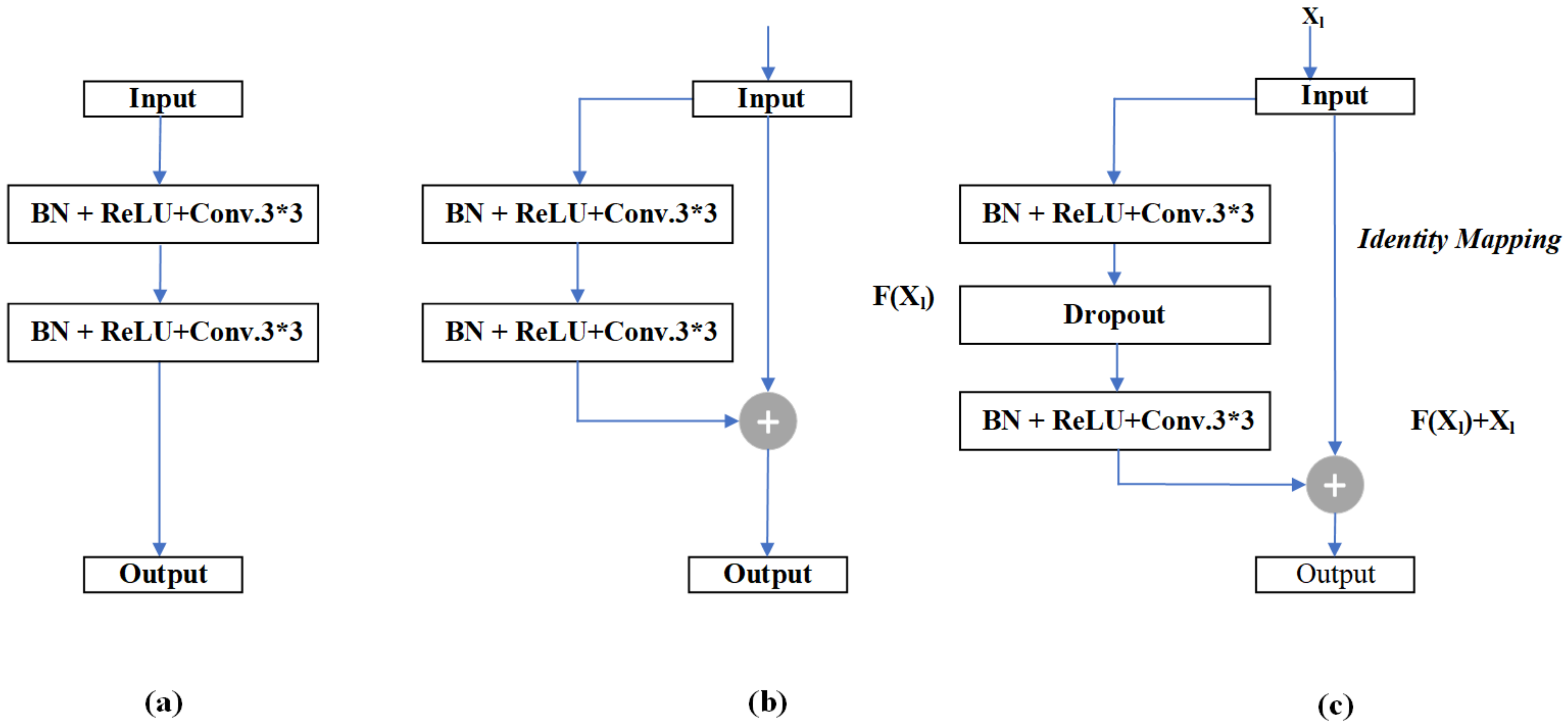

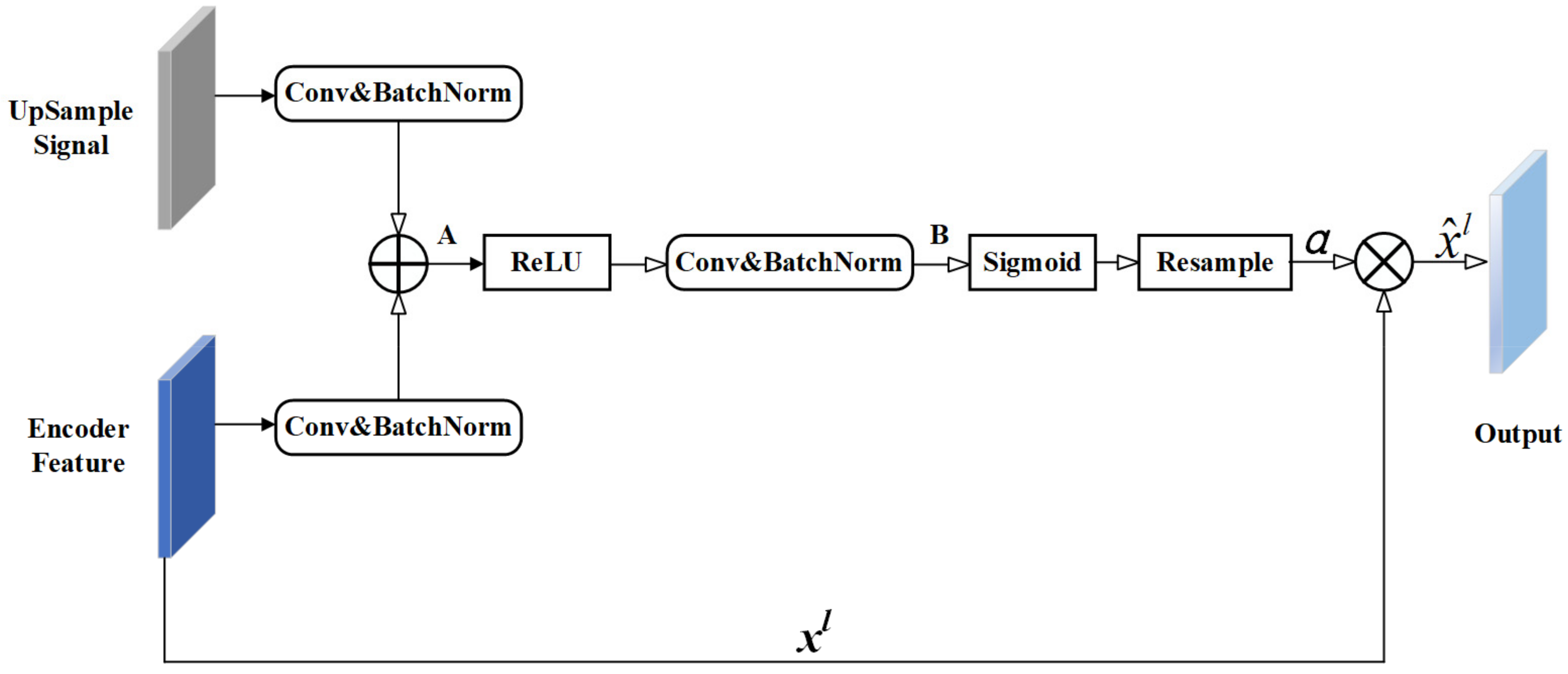

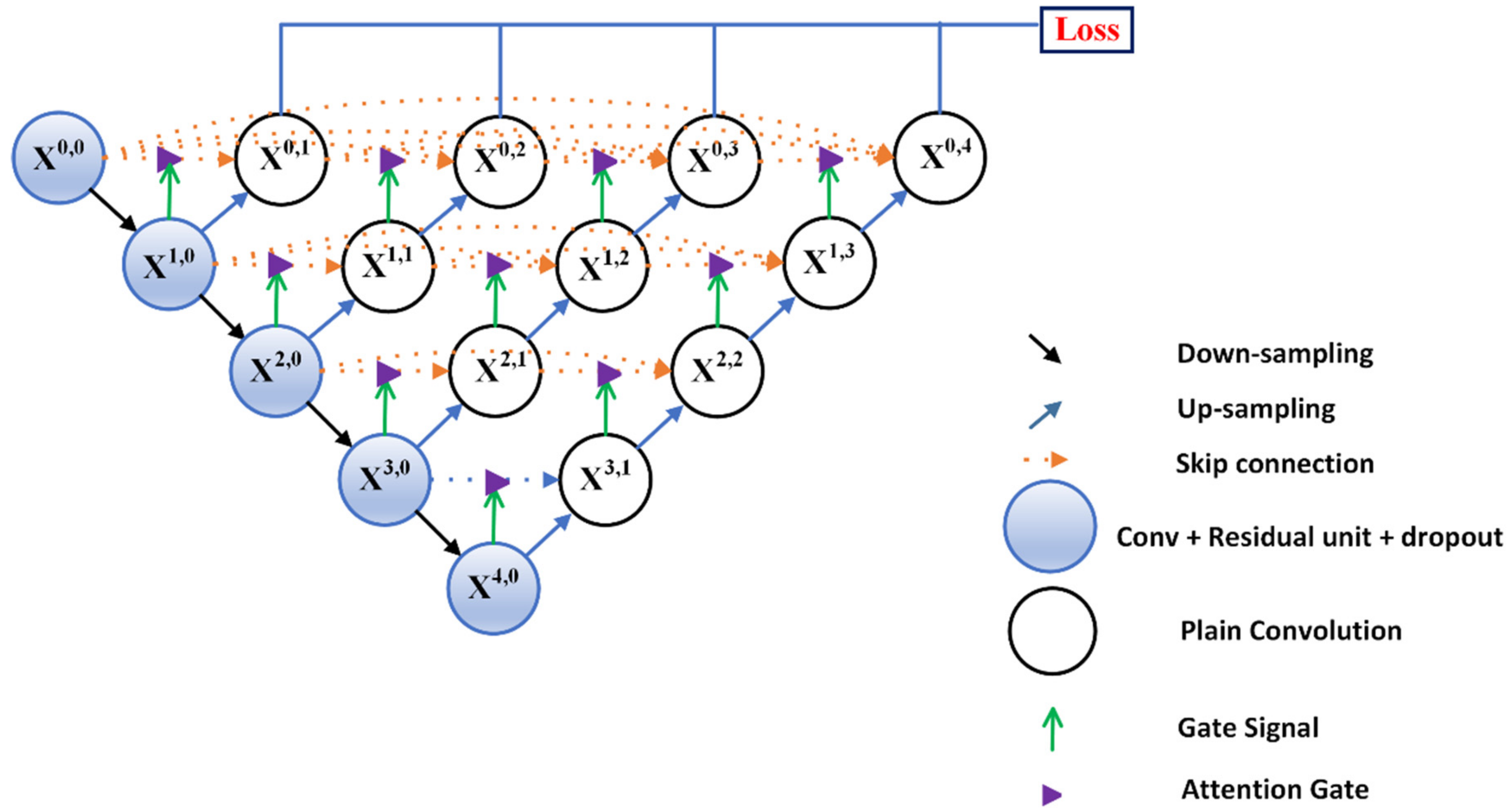

- The residual unit and attention mechanism were introduced to UNet++ to increase the weight of target areas and to solve the degradation problem.

- The proposed model Residual-Attention UNet++ was introduced for medical image segmentation.

- The experiments conducted on three medical imaging datasets demonstrated better performance in segmentation tasks compared with existing methods.

- Residual-Attention UNet++ could increase the weight of the target area and suppress the background area irrelevant to the segmentation task.

- Comparison against some UNet-based methods showed superior performance.

- The pruned Residual-Attention UNet++ enabled faster inference at the cost of minimal performance degradation.

2. Related Work

3. Methodology

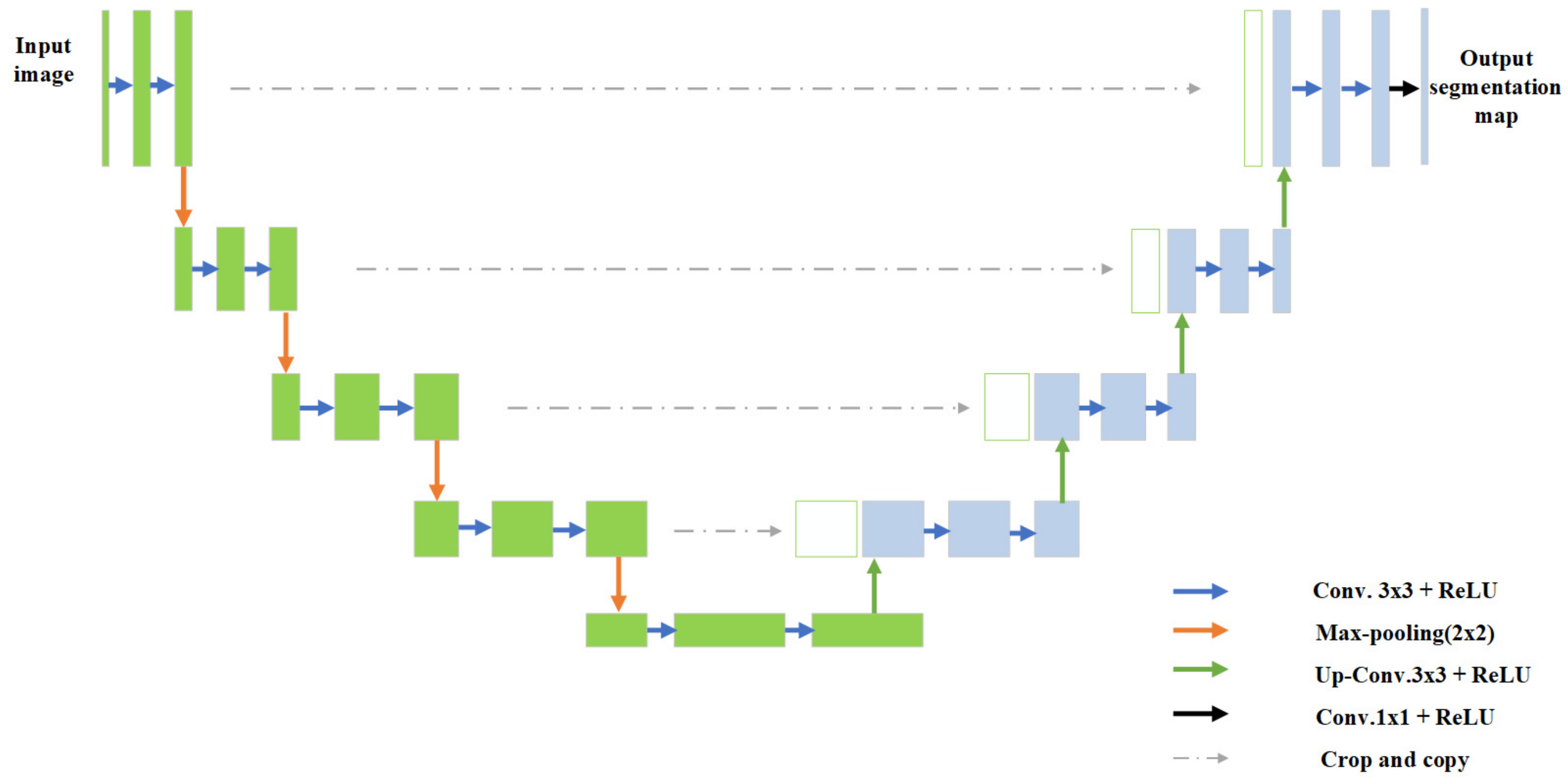

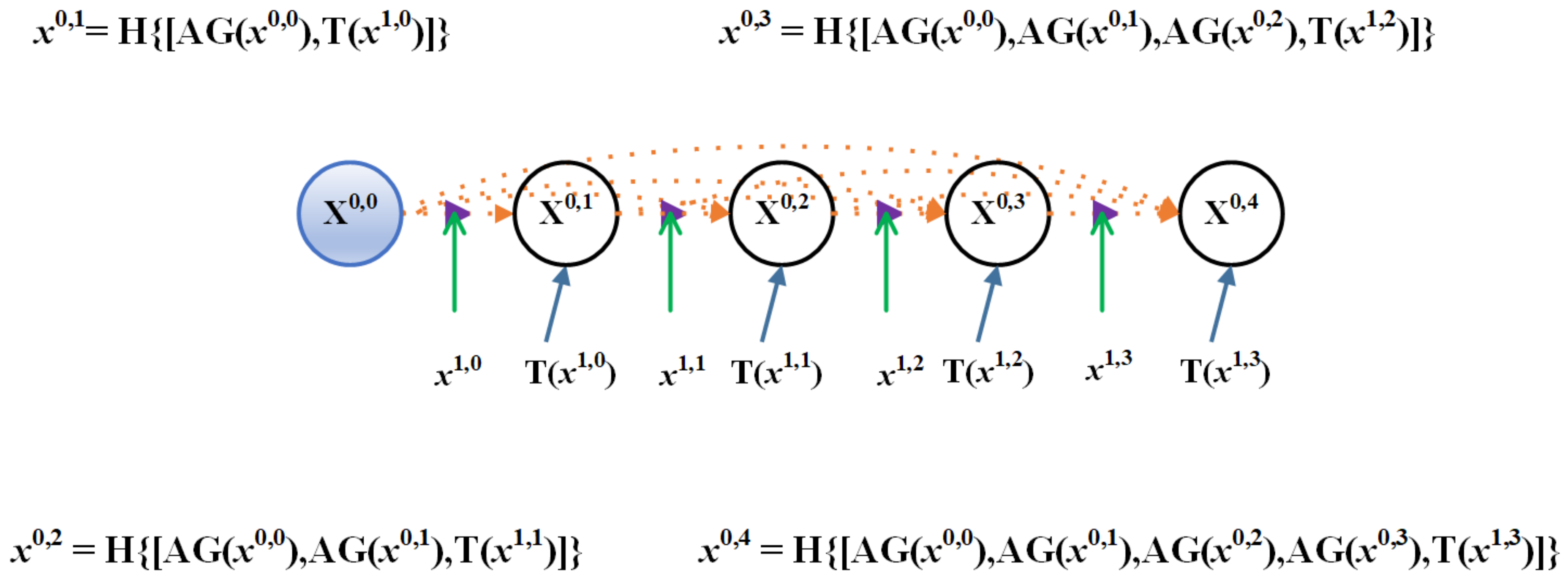

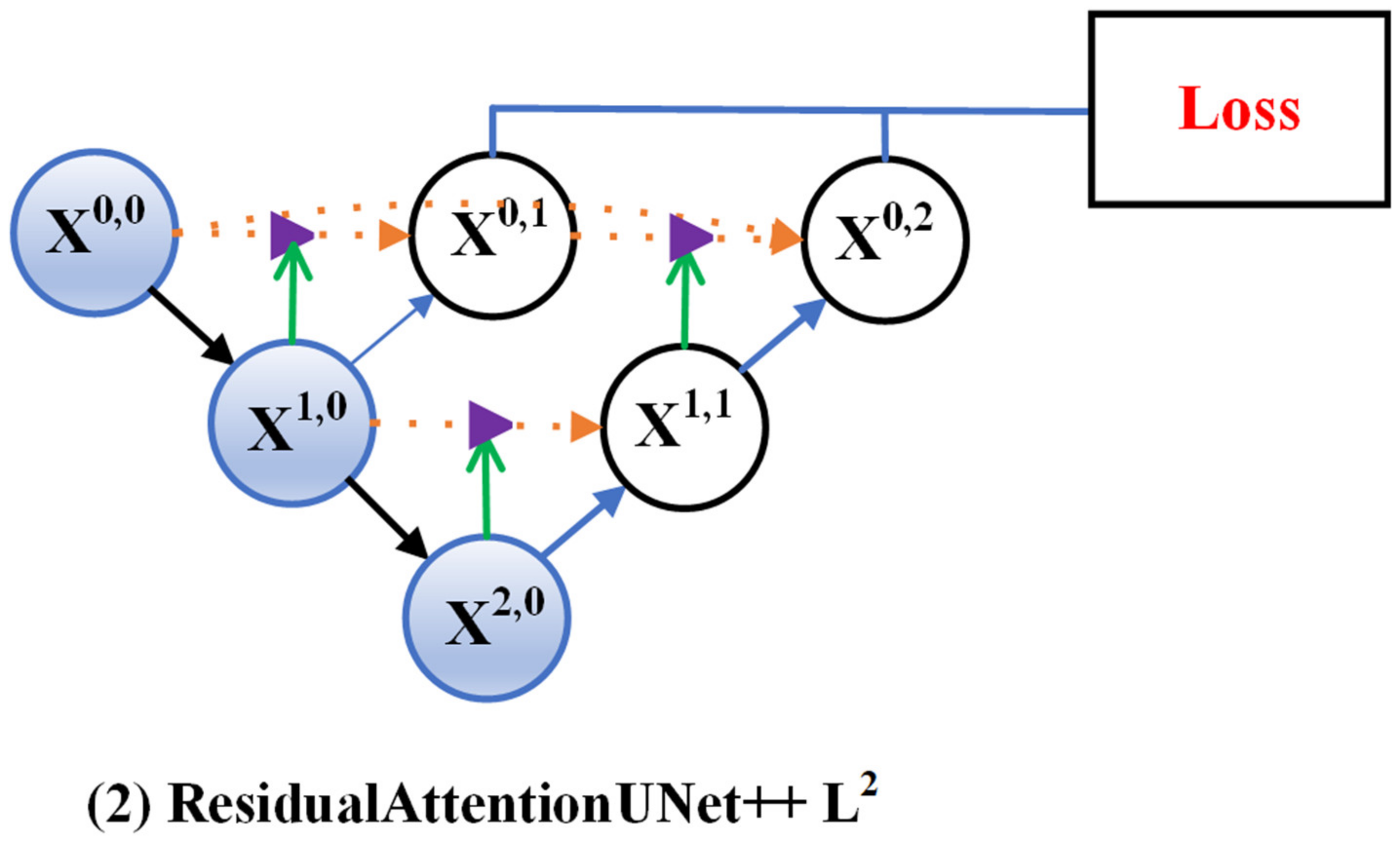

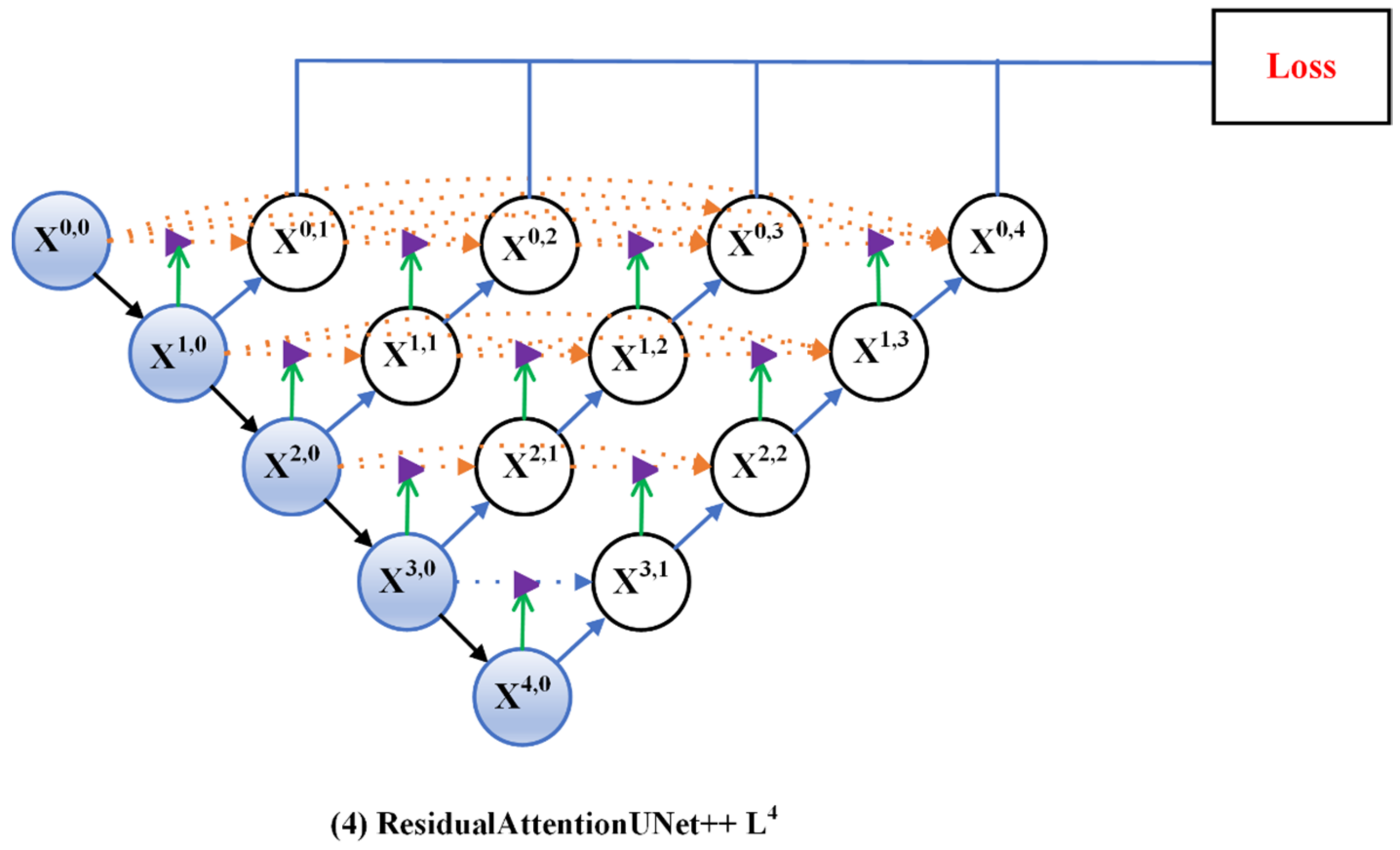

3.1. Residual-Attention UNet++

3.2. Deep Supervision

3.3. Model Pruning

4. Experiments and Results

4.1. Dataset

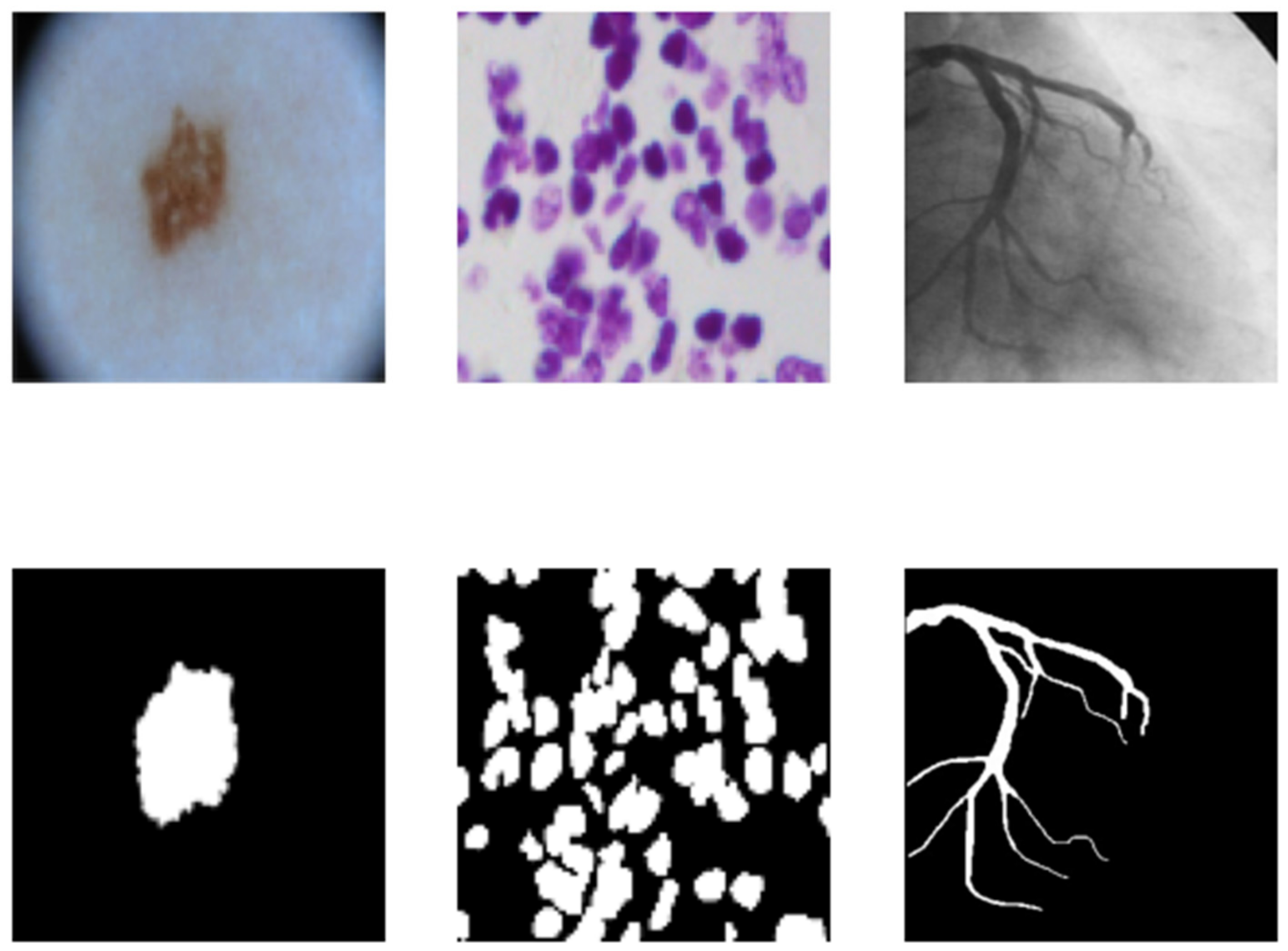

4.1.1. Skin Cancer Segmentation

4.1.2. Cell Nuclei Segmentation

4.1.3. Coronary Artery in Angiography Segmentation

4.2. Evaluation Metrics

4.3. Results

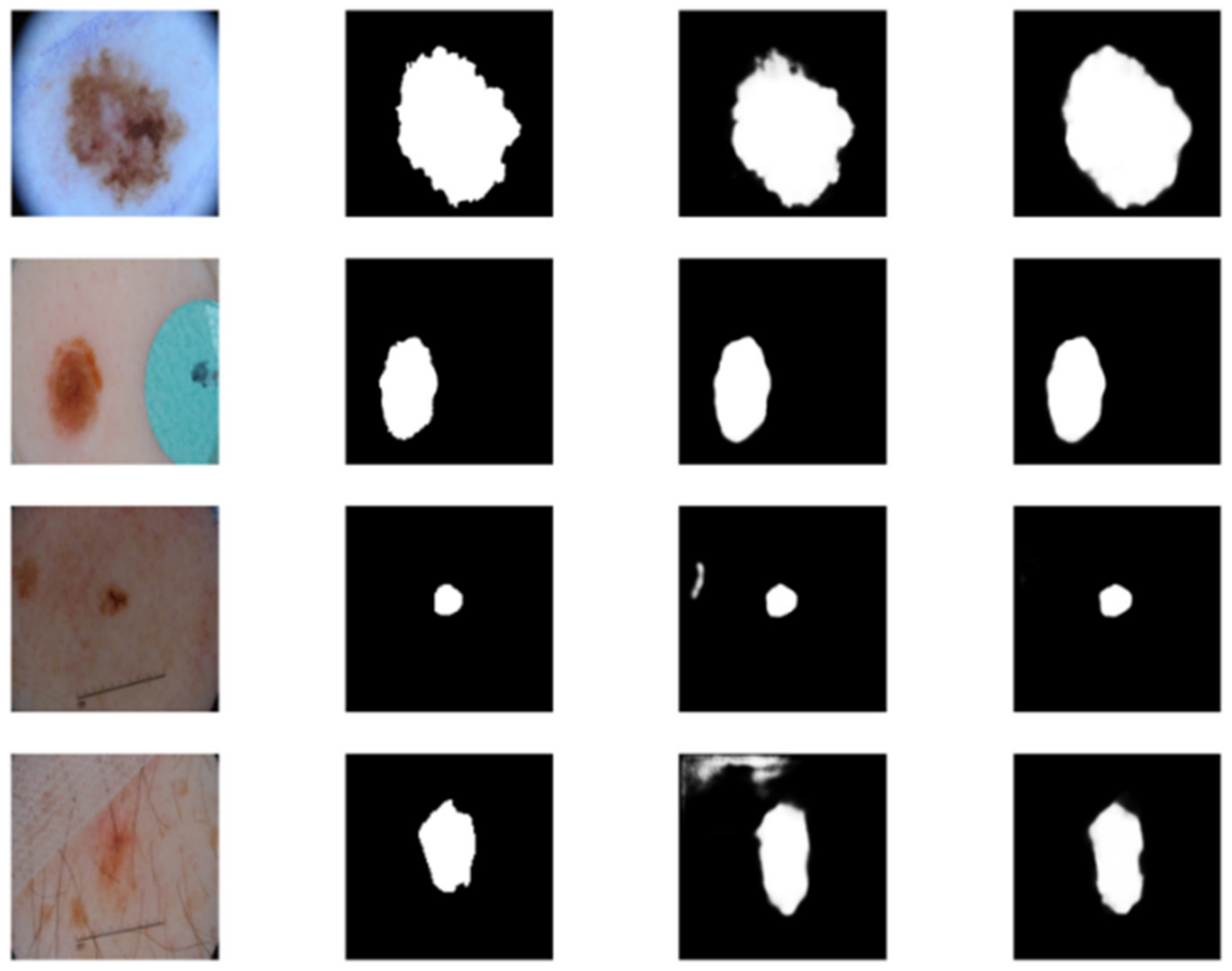

4.3.1. Skin Cancer Segmentation

4.3.2. Cell Nuclei Segmentation

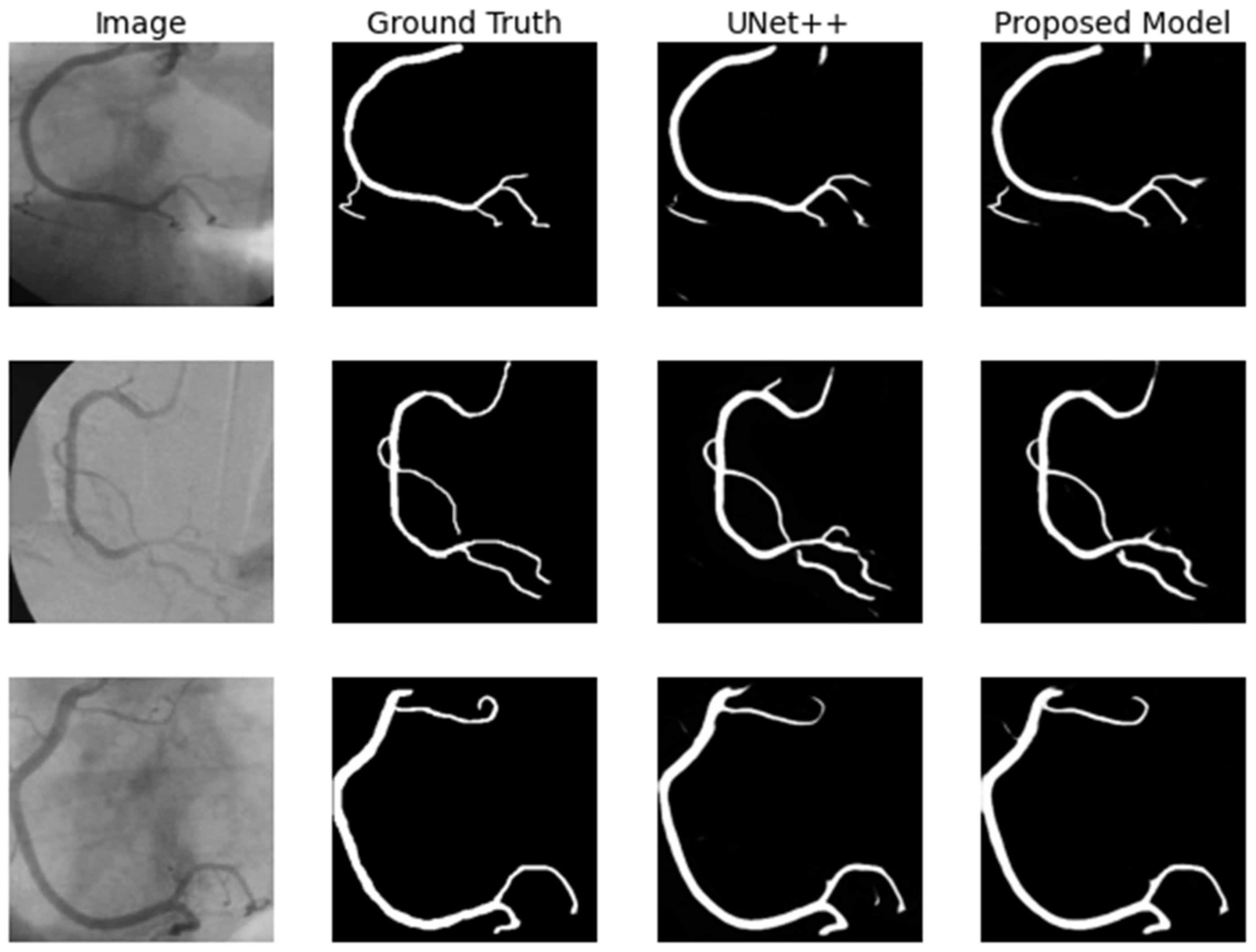

4.3.3. Coronary Artery in Angiography Segmentation

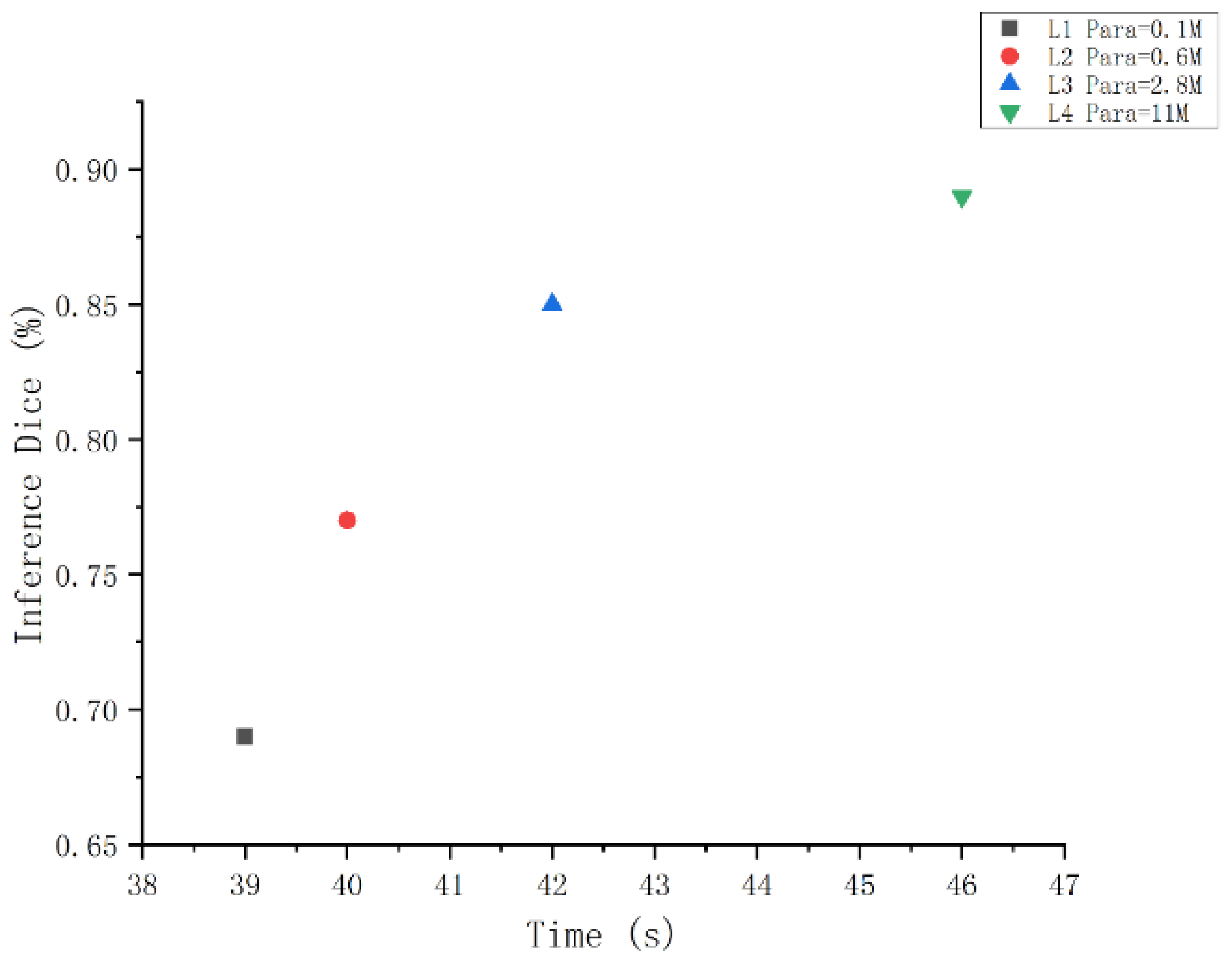

4.4. Model Pruning

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Young, K.D.; Utkin, V.I.; Ozguner, U. A Control Engineer’s Guide to Sliding Mode Control. IEEE Trans. Control. Syst. Technol. 1999, 7, 328–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rother, C. GrabCut: Interactive foreground extraction using iterated graph cut. ACM Trans. Graph. 2004, 23, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, L.S.; Rosenfeld, A.; Weszka, J.S. Region Extraction by Averaging and Thresholding. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. 1975, 3, 383–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senthilkumaran, N.; Rajesh, R. Edge Detection Techniques for Image Segmentation—A Survey of Soft Computing Approaches. In Proceedings of the 2009 International Conference on Advances in Recent Technologies in Communication and Computing, Kottayam, India, 27–28 October 2009; pp. 844–846. [Google Scholar]

- Nowozin, S.; Lampert, C.H. Structured Learning and Prediction in Computer Vision. Found. Trends® Comput. Graph. Vis. 2011, 6, 185–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sulaiman, S.N.; Isa, N.M. Adaptive fuzzy-K-means clustering algorithm for image segmentation. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electr. 2010, 56, 2661–2668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostu, N.; Nobuyuki, O.; Otsu, N. A thresholding selection method from gray level histogram. IEEE SMC-8 1979, 9, 62–66. [Google Scholar]

- Alom, M.Z.; Hasan, M.; Yakopcic, C.; Taha, T.M.; Asari, V.K. Recurrent Residual Convolutional Neural Network based on U-Net (R2U-Net) for Medical Image Segmentation. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1802.06955. [Google Scholar]

- Xi, H.; Chen, J.; Chen, L.; Liang, H.; Wang, Q. Pyramid Residual Convolutional Neural Network based on an end-to-end model. In Proceedings of the 2020 13th International Conference on Intelligent Computation Technology and Automation (ICICTA), Xi’an, China, 24–25 October 2020; pp. 154–158. [Google Scholar]

- Long, J.; Shelhamer, E.; Darrell, T. Fully Convolutional Networks for Semantic Segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Boston, MA, USA, 7–12 June 2015; Volume 39, pp. 3431–3440. [Google Scholar]

- Song, W.; Zhong, B.; Sun, X. Building Corner Detection in Aerial Images with Fully Convolutional Networks. Sensors 2019, 19, 1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, L.C.; Papandreou, G.; Kokkinos, I.; Murphy, K.; Yuille, A.L. Semantic Image Segmentation with Deep Convolutional Nets and Fully Connected CRFs. Comput. Sci. 2014, 357–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krähenbühl, P.K.V. Efficient Inference in Fully Connected CRFs with Gaussian Edge Potentials. Adv. Neural Inf. Processing Syst. 2011, 24, 109–117. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.C.; Papandreou, G.; Kokkinos, I.; Murphy, K.; Yuille, A.L. DeepLab: Semantic Image Segmentation with Deep Convolutional Nets, Atrous Convolution, and Fully Connected CRFs. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. 2017, 40, 834–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Liu, X.; Song, L.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Y. A Review of Deep-Learning-Based Medical Image Segmentation Methods. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.C.; Papandreou, G.; Schroff, F.; Adam, H. Rethinking Atrous Convolution for Semantic Image Segmentation. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1706.05587. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.C.; Zhu, Y.; Papandreou, G.; Schroff, F.; Adam, H. Encoder-Decoder with Atrous Separable Convolution for Semantic Image Segmentation. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 801–818. [Google Scholar]

- Badrinarayanan, V.; Kendall, A.; Cipolla, R. SegNet: A Deep Convolutional Encoder-Decoder Architecture for Image Segmentation. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2017, 39, 2481–2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-Net: Convolutional Networks for Biomedical Image Segmentation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention, Munich, Germany, 5–9 October 2015; pp. 234–241. [Google Scholar]

- Özgün, Ç.; Abdulkadir, A.; Lienkamp, S.S.; Brox, T.; Ronneberger, O. 3D U-Net: Learning Dense Volumetric Segmentation from Sparse Annotation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention, Athens, Greece, 17–21 October 2016; pp. 424–432. [Google Scholar]

- Milletari, F.; Navab, N.; Ahmadi, S.A. V-Net: Fully Convolutional Neural Networks for Volumetric Medical Image Segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2016 Fourth International Conference on 3D Vision (3DV), Stanford, CA, USA, 25–28 October 2016; pp. 565–571. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Delving Deep into Rectifiers: Surpassing Human-Level Performance on ImageNet Classification. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Santiago, Chile, 7–13 December 2015; pp. 1026–1034. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Chen, H.; Qi, X.; Dou, Q.; Fu, C.W.; Heng, P.A. H-DenseUNet: Hybrid Densely Connected UNet for Liver and Tumor Segmentation From CT Volumes. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2018, 37, 2663–2674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Oktay, O.; Schlemper, J.; Folgoc, L.L.; Lee, M.; Heinrich, M.; Misawa, K.; Mori, K.; Mcdonagh, S.; Hammerla, N.Y.; Kainz, B. Attention U-Net: Learning Where to Look for the Pancreas. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1804.03999. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, J.; Wang, X.; Cai, J.; Qin, Q.; Yang, H.; Wang, Q.; Cheng, Y.; Gan, T.; Jiang, H.; Deng, J.; et al. Medical image segmentation model based on triple gate MultiLayer perceptron. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Siddiquee, M.; Tajbakhsh, N.; Liang, J. UNet++: A Nested U-Net Architecture for Medical Image Segmentation. In Deep Learning in Medical Image Analysis and Multimodal Learning for Clinical Decision Support; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava, N.; Hinton, G.; Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Salakhutdinov, R. Dropout: A Simple Way to Prevent Neural Networks from Overfitting. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2014, 15, 1929–1958. [Google Scholar]

- Zagoruyko, S.; Komodakis, N. Wide Residual Networks. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1605.07146. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Girshick, R.; Gupta, A.; He, K. Non-local Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 7794–7803. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Tan, Y.; Chen, W.; Luo, X.; Li, F. ANU-Net: Attention-based Nested U-Net to exploit full resolution features for medical image segmentation. Comput. Graph. 2020, 90, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.Y.; Xie, S.; Gallagher, P.; Zhang, Z.; Tu, Z. Deeply-Supervised Nets. In Proceedings of the Artificial Intelligence and Statistics, San Diego, CA, USA, 9–12 May 2015; pp. 562–570. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.; Siddiquee, M.; Tajbakhsh, N.; Liang, J. UNet++: Redesigning Skip Connections to Exploit Multiscale Features in Image Segmentation. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2020, 39, 1856–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- ISIC 2017 Challenge. Available online: https://challenge2017.isic-archive.com (accessed on 11 July 2021).

- Data Science Bowl 2018. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/c/data-science-bowl-2018 (accessed on 14 June 2021).

- Cervantes-Sanchez, F.; Cruz-Aceves, I.; Hernandez-Aguirre, A.; Hernandez-Gonzalez, M.A.; Solorio-Meza, S.E. Automatic Segmentation of Coronary Arteries in X-ray Angiograms using Multiscale Analysis and Artificial Neural Networks. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 5507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dice, L.R. Measures of the Amount of Ecologic Association Between Species. Ecology 1945, 26, 297–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Methods | F1-Score | SE | IoU (%) | DC (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FCN | 0.8671 | 0.8748 | 81.45 | 86.58 |

| SegNet | 0.8862 | 0.8801 | 81.58 | 87.81 |

| U-Net | 0.8880 | 0.8884 | 81.49 | 87.79 |

| Attention UNet | 0.8866 | 0.8965 | 81.46 | 87.81 |

| UNet++ | 0.8896 | 0.8991 | 81.79 | 87.93 |

| Attention UNet++ | 0.8938 | 0.8942 | 82.21 | 88.54 |

| Residual Attention UNet++ | 0.8955 | 0.9112 | 82.32 | 88.59 |

| Hyperparameter | |

|---|---|

| Batch size | 64, 32, 16, 8, 4 |

| Learning rate | 0.0001, 0.0003 |

| Optimizer | Adam, SGD |

| Lr scheduler | ExponentialLR, StepLR |

| Methods | F1-Score | SE | IoU (%) | DC (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FCN | 0.6260 | 0.7008 | 50.80 | 62.65 |

| SegNet | 0.8407 | 0.9051 | 77.59 | 81.26 |

| U-Net | 0.8773 | 0.9381 | 83.84 | 82.17 |

| Attention UNet | 0.8719 | 0.9362 | 83.51 | 76.49 |

| UNet++ | 0.8609 | 0.9367 | 81.54 | 73.51 |

| Attention UNet++ | 0.8771 | 0.9344 | 84.40 | 81.17 |

| Residual Attention UNet++ | 0.8831 | 0.9493 | 87.74 | 85.91 |

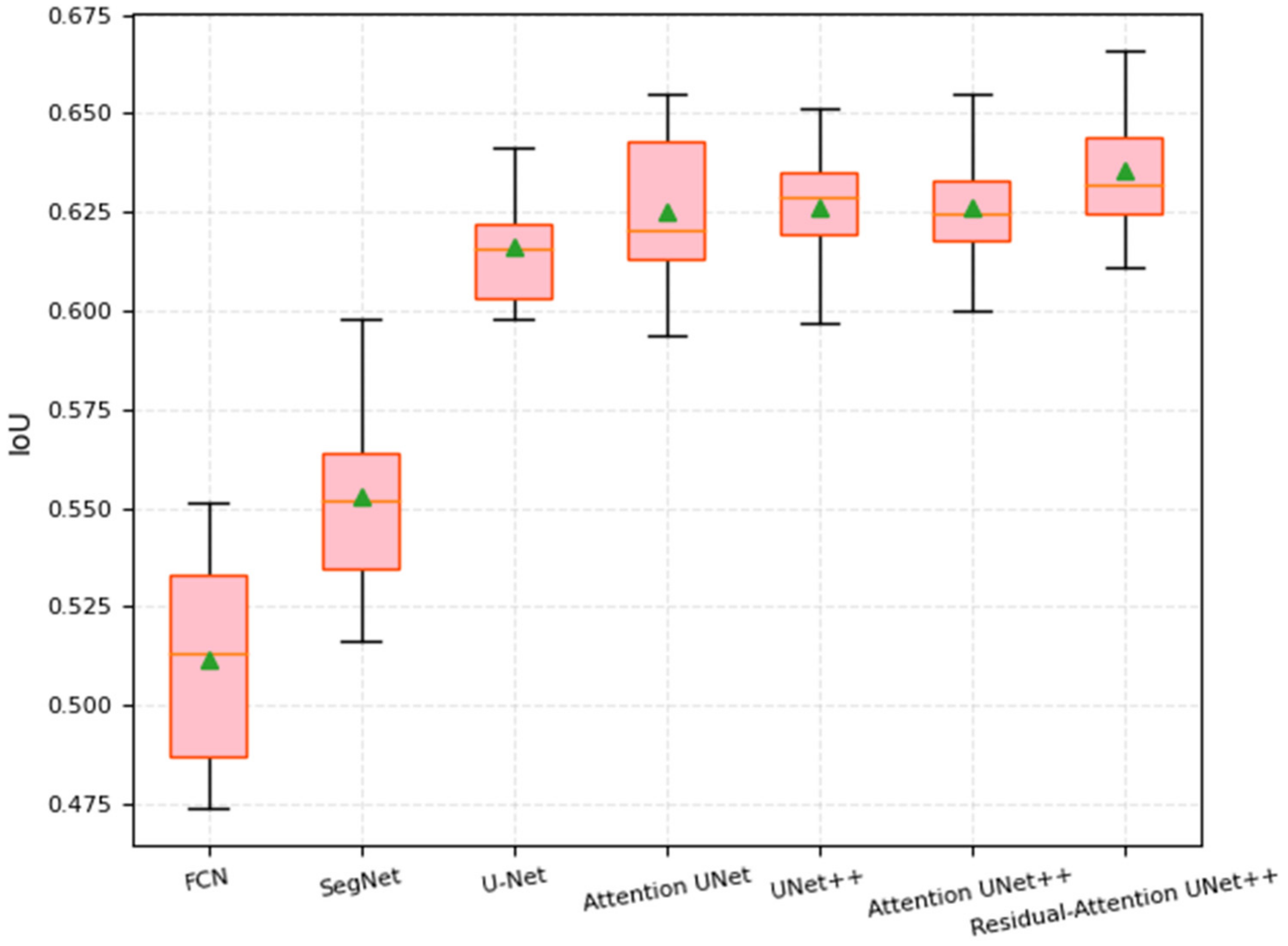

| Methods | F1-Score | SE | IoU (%) | DC (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FCN | 0.5330 | 0.7250 | 55.12 | 68.34 |

| SegNet | 0.5631 | 0.7506 | 59.81 | 69.40 |

| U-Net | 0.5841 | 0.7865 | 64.15 | 69.17 |

| Attention UNet | 0.5904 | 0.8034 | 65.48 | 69.84 |

| UNet++ | 0.5907 | 0.8119 | 65.11 | 70.02 |

| Attention UNet++ | 0.5901 | 0.8135 | 65.51 | 70.47 |

| Residual Attention UNet++ | 0.6110 | 0.8335 | 66.57 | 72.48 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, Z.; Zhang, H.; Li, Z.; Ren, Z. Residual-Attention UNet++: A Nested Residual-Attention U-Net for Medical Image Segmentation. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 7149. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12147149

Li Z, Zhang H, Li Z, Ren Z. Residual-Attention UNet++: A Nested Residual-Attention U-Net for Medical Image Segmentation. Applied Sciences. 2022; 12(14):7149. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12147149

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Zan, Hong Zhang, Zhengzhen Li, and Zuyue Ren. 2022. "Residual-Attention UNet++: A Nested Residual-Attention U-Net for Medical Image Segmentation" Applied Sciences 12, no. 14: 7149. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12147149

APA StyleLi, Z., Zhang, H., Li, Z., & Ren, Z. (2022). Residual-Attention UNet++: A Nested Residual-Attention U-Net for Medical Image Segmentation. Applied Sciences, 12(14), 7149. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12147149