Abstract

The study of structural masonry joined to geohydrological hazards in cultural heritage represents a multidisciplinary theme, which requires consideration of several aspects, among them the characterization of the materials used. In this paper, a first complete chemical, minero-petrographic, and physico-mechanical characterization of core samples taken from the masonry of two Florence riverbanks (Lungarno degli Acciaiuoli and Lungarno delle Grazie) is performed in order to identify the raw materials, technologies, and state of conservation and to support the planning of maintenance and restoration interventions. The physico-mechanical characterization of the riverbanks allows their stability to be determined. Such investigations allow identification of the level of compactness and cohesion of masonry; this information is useful for planning emergency interventions and for supporting planned restoration activities. The results provide valid support for the design of riverbank safety projects, to mitigate the risk of their collapse and to decrease the flood risk in the historic center of Florence.

1. Introduction

Conservation of historical masonry building needs a thorough understanding of the physico-mechanical features and the sources of decay and vulnerability to preserve heritage integrity [1,2,3,4,5]. The study of historical masonry of riverbanks represents a multidisciplinary theme, which requires consideration of several aspects, among them the characterization of used materials, such as the mortars. The mortars influence the structural behavior of masonry, and their characterization is important to improve the knowledge of mechanical properties of civil architectural heritage walls. Several studies highlighted the relevance of these materials to acquire detailed information on the physico-mechanical behavior of the structure [6,7,8,9,10,11] and to select the most suitable maintenance and restoration programs [12,13,14,15].

The historic center of Florence (Italy), crossed by the Arno River, has suffered many geohydrological disasters during history, due to floods, landslides, and riverbank failures [16,17]. The current riverbank morphology of Florence is the result of urbanization, typical of centuries-old cities, which have been mainly developed along the river, and resources for many activities. On the other hand, the river may represent a threat. Indeed, the Arno River floods have damaged and destroyed millions of art masterpieces, rare books, and several monuments along the riverbanks area (named Lungarni). To mitigate the impact of geohydrological hazards on cultural heritage and avoid the collapse of riverbanks, it is important to improve the knowledge of the properties of their constituent materials. In particular, evaluation of the physical and mechanical parameters of the building materials is necessary to assess their durability, degradation phenomena, and service life. The analysis of historical masonry walls is a complex task in terms of information about the inner core of the structural elements and for characterization of mechanical properties of the used materials and also due to their large variability. The different types of used mortars affect the masonry performance, allowing some degree of movement from creep or thermal effects without cracking. The mortar must be also sufficiently strong to develop an adequate adhesion to the elements [18] and to preserve the characteristic in time, especially in this case, in conditions of high humidity or even in an underwater environment.

Chemical, mineralogical, and petrographic methodologies are often applied in order to obtain useful data for a complete characterization of binder, aggregate, and possible additives of mortars used in archaeological and architectonic heritage, but a few papers contain data on physico-mechanical characteristics [8,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26]. Due to the difficulty of obtaining test samples of a suitable size for application of standardized physico-mechanical tests, in situ micro invasive methods are preferred [6,27,28,29].

In this study, for the first time, a complete chemical, mineralogical, petrographic, and physico-mechanical characterization of the masonry of two Florence riverbanks (Lungarno degli Acciaiuoli and Lungarno delle Grazie) is performed. The analyzed mortars belong to different portions of masonry of the riverbanks. The sampling was carried out to identify similarities or differences among phases, improving the knowledge of building technologies and raw materials used at different times. In fact, this methodology made it possible to identify four layers of masonry in the stratigraphy of the walls; two historical layers and two modern layers, post 1966, were discovered. Particular attention was paid to historical masonry that composes the lower portion of the riverbanks, a part that is subjected more to the extreme condition of complete saturation. Furthermore, the final aim of this research is to determine the masonry quality, on a physico-mechanical level, useful information for the engineers and technicians in charge of preserving and restoring the site and providing advice to manage the risk.

2. Florence Riverbanks

Lungarno degli Acciaiuoli and Lungarno delle Grazie are located on the hydrographical right side of the Arno River in Florence, between Ponte Vecchio and Ponte Santa Trinita and Ponte San Niccolò and Ponte alle Grazie, respectively (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Lungarno degli Acciaiuoli riverbank: currently (a) and after flood of 1966 (Alinari archive), the embankment viewed from Ponte Vecchio of collapse of riverbank (b); Lungarno delle Grazie riverbank: currently (c) and after flood of 1966 (Alinari archive) (d).

The Lungarno degli Acciaiuoli, whose name comes from the magnificent Palace of the Acciaiuoli family, is mentioned in official documents for the first time in 1246. In 1823–1824 it was amplified, during the demolition of a wing of the Spini Palace. The “Operation Feuerzauber” or “Magic Fire” in 1944 during the Second World War, which destroyed all the bridges in and near Florence, except Ponte Vecchio, did not damage Lungarno degli Acciaiuoli although the riverbank was close to Ponte Vecchio (Figure 1a) [30,31,32].

The Lungarno delle Grazie, whose name comes from the Oratory of Santa Maria delle Grazie, was built most likely in the 13th century. The definition of the route of Lungarno delle Grazie, indeed, is closely linked to the construction of the homonymous bridge in 1236 (Figure 1c) [30,31,32]. Both riverbanks were severely damaged during the flood in Florence in 1966 and subsequently restored (Figure 1b,d).

The construction method is rubble masonry, and the wall was realized with an outer layer and an internal core. A detailed examination of masonry shows a cortical wall made with squared stone (sandstone) and an inner part filled with a coarse aggregate (mainly stone elements and, in some levels, also bricks) and mortars. Some areas present a plaster coating; while most of these in Lungarno alle Grazie are missing, on the Lungarno degli Acciaiuoli they are reasonably well preserved. The two embankments have a different shape: the Lungarno degli Acciaiuoli wall is straight until the quay, while Lungarno delle Grazie is characterized by a massive scarp wall.

The masonry performs the function of retaining wall, which was built in a vertical sequence to protect the city from high flood currents and to sustain the levee wall. In order to keep the features of these important structures, the Tuscany Region Civil Engineers has developed a project aimed at the adaptation of flood containment structures in the town of Florence. This study is part of the project.

3. Macroscopic Description

During the first survey, 14 masonry cores were collected from riverbanks using a wet core drilling system executed perpendicular to the face of the masonry; only one core was extracted with an incline of 45° (C2bis). C1, C2, C2b, C3, C4, C5, and C6 core samples belong to Lungarno degli Acciaiuoli, and C7, C8, C9, C10, C11, C12, and C13 were sampled from Lungarno delle Grazie. The position of core sampling was selected from previous geophysical investigation that characterized complete areas of Lungarni. Some anomalies and voids in the riverbanks were observed: in these points the masonry cores were sampled. Particular attention was paid to historical masonry that conducts the function of a load-bearing wall and is submitted to extreme conditions of complete saturation.

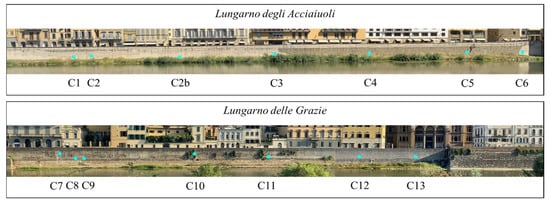

In Figure 2 the position of coring is reported. The core samples are composed by fine mortar and coarse aggregates. These materials were investigated through a preliminary macroscopic observation, and on some selected samples a complete mineralogical, petrographic, and physico-mechanical characterization was carried out.

Figure 2.

Position of core sampling: 14 masonry cores (light-blue dots) were extracted (7 core samples from Lungarno degli Acciaiuoli and 7 from Lungarno delle Grazie).

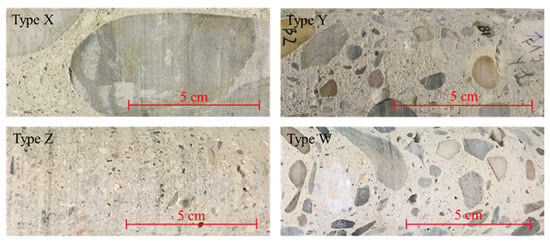

A macroscopic description was performed on site using an endoscopic and optometric survey to identify macroscopic features of the masonry and in the laboratory using a Zeiss optical stereomicroscope up to 200 magnifications. The combination of the techniques allowed identification of 4 typologies of mortar, which are named X, Y, W, and Z. In Figure 3, the macroscopic aspect of these types are reported: historic mortar with decimeter-sized coarse aggregates (type X), historic mortar with centimeter-sized coarse aggregates (type Y), modern mortar with millimeter-sized coarse aggregates (type Z), and modern mortar with centimeter-sized coarse aggregates (type W). The term historic mortar is used to indicate a mixture of a traditional binder, fine aggregates, water, and possible additives used in riverbanks as filling of the nucleus of the masonry, while the term modern mortar is used to identify modern hydraulic binder and fine aggregates mixed with water and additives. The coarse aggregates are largely composed of stone fragments, such as Pietraforte, Pietra Serena, and Pietra Alberese. Pietraforte and Pietra Serena are the most used sandstones in Florentine architecture [33,34], while Pietra Alberese is a marly limestone that in Florence was mainly used for lime production [35].

Figure 3.

Macroscopic aspect of the four different macroscopic types of core samples.

Table 1 summarizes the descriptions of each core, the position on riverbanks and the assigned macroscopic type. To carry out an initial assessment of the quality of the cores a standardized geotechnical method, the RQD index, was used [36] (Table 1). This index gives the qualitative and quantitative assessment of rock quality and degree of jointing and fracturing in a rock mass as the percentage of intact drill core pieces longer than 10 cm recovered. The quality classification based on the RQD index is divided into five classes: 0–25% (very poor quality), 25–50% (poor quality), 50–75% (fair quality), 75–90% good (quality), and 90–100% (very good quality). In this work, the RQD index has been applied considering that the extracted carrots are composed of aggregates of dimensions from about 1 cm to 10 cm. In addition, cohesion between the binder and such aggregates is considered.

Table 1.

Macroscopic descriptions of cores and RQD values.

The study of the masonry carried out through macroscopic description, identification of the mortar types and their distribution in the core samples in the masonry, allows identification of the most representative portion for the characterization of masonry cores. The representative samples of the various mortar types present in the core samples were selected for comprehensive diagnostic investigation.

4. Analytical Methods

4.1. Chemical, Minero-Petrographic Characterization

The chemical, mineralogical, and petrographic characterization was performed on 2samples for each masonry type, only considering the historic and modern mortar portions (Table 2), using the following analytical methodologies:

Table 2.

Selected samples for the multi-analytical characterization.

- -

- Petrographic investigation of thin sections (30 µm thickness) was carried out through observation in transmitted light with an optical microscope (OM). In the case of mortars, the petrographic approach permits accurate characterization of binder, aggregate, lump, and inorganic additives and admixtures [33,37,38,39,40,41]. In some cases, the observation of lumps in the thin section, as reported by several contributers, allows recognition of the type of carbonate rock burnt in the kiln. Lumps, indeed, can be due to binder not being well mixed in the paste, to under-burnt fragments (remnants of under-burnt limestone), to overburnt fragments of limestone, or to hydrated and carbonated overburnt fragments after the setting reaction of the mortar [33,40,42,43,44]. A Zeiss Axioscope A.1 microscope with a camera to obtain images and dedicated software for image elaboration and measuring of main characteristics of materials (AxioVision, Carl Zeiss Microscopy, LLC, White Plains, NY, USA) was used.

- -

- X-ray diffractometry (XRD) using a Philips X’Pert PRO on powders was employed to determine the mineralogical composition using Cu anticathode (l = 1.54 Å), under the following conditions: current intensity of 30 mA, voltage 40 kV, explored 2ϴ range between 3 and 70°, step size 0.02°, and time to step 50 s. The XRD analyses were performed on powder bulk samples and on selected lumps.

- -

- Thermo-gravimetric analysis (TGA) was employed for binder characterization of mortars. Some fragments of each sample were disaggregated using a porcelain pestle, and the fraction passing through a sieve with 63 µm openings (ISO R 565 Series) was considered as a binder-enriched specimen. TGA was used to evaluate the presence and the amount of volatile compounds (essentially H2O, CO2) in the samples. TGA was conducted in the range 110–1000 °C on about 5 mg of sample, dried (silica gel as drying agent) at room temperature for at least a week under the following experimental conditions: open alumina crucibles, heating rate of 10 °C/min, and 30 mL/min nitrogen gas flow. TGA was used for classifying the studied samples as non-hydraulic mortars or hydraulic ones as suggested by most authors [20,44,45]. TGA analyses were performed using a Perkin Elmer Pyris 6 system on historic mortar samples.

- -

- Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) was employed for the determination of the composition of selected lumps through a Bruker spectrometer equipped with an ATR system. The spectra obtained from the analysis of the powdered sample were acquired and processed using OPUS 7.2 software (Bruker Optics GmbH, Ettlingen, Germany). The acquisition was carried out in the spectral range between 4000 and 400 cm−1, with a resolution of 4 cm−1 for 24 scans.

4.2. Physico-Mechanical Characterization

The effective porosity (Pw%), density (ρ), and total imbibition coefficient (IC%) were determined on 2 × 2 × 2 cm test samples, representative of historic and modern mortar portions (Table 2), using a Mettler Toledo hydrostatic balance [46].

The capillary water absorption coefficient (Aw) was determined on cylindric test samples with a height of 2 cm and a diameter of 5 cm, following the UNI EN 15801:2010 [47].

The ultrasonic velocity (UV) test was carried out on cylindrical test samples with a height/diameter ratio of 1:1 (5 × 5 cm); the same samples were used for the uniaxial compression (UC) test, to correlate the results. All the cylindric test samples are representative of the complete masonry types (Table 2).

The UV were realized through an IMG 5200 CSD ultrasonic instrument characterized by two 50 kHz transducers, to identify the presence of internal defects and inhomogeneities, which depends on the contribution of the individual constituents of the wall structure itself. The measurements were carried out with the direct transmission method: the transmitter/receiver transducers pair are placed on two opposite faces of the cylindrical sample (along the central axis). Furthermore, the direct transmission test is the one that offers results of a certain reliability (accuracy of ±1%). The calculated parameter is the velocity of the first wave able to travel through the material (Vp).

The UC was performed using a press machine with a 60 kN loading cell. Tests were performed in displacement control by imposing a load constant stress rate of 0.3 MPa/s, to obtain a compressive strength (s).

In order to identify the contribution of the various components (mortar, coarse aggregates, and voids) on the mechanical test results, the cylindrical samples used for UV and UC tests were characterized through an innovative approach, in accordance with the following procedure:

- -

- photogrammetric processing of the samples, delivering an orthophoto of each surface;

- -

- 1:1 scale reproduction of the image;

- -

- area calculation of mortar, coarse aggregates, and voids;

- -

- calculation of the percentage values of each component with respect to the total area.

Starting from this method, the percentages of coarse aggregate, mortar, and voids present with respect to the total area of the samples were obtained.

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Chemical, Minero-Petrographic Results

The main mineralogical and petrographic characteristics of the analysed samples are summarized in Tables S1 and S2, respectively. The minero-petrographic data carried out on the finer portions (mortar) of the samples extracted from cores of Lungarno degli Acciaiuoli and Lungarno delle Grazie show similarities and differences.

Mineralogical analysis indicates the presence of calcite (CaCO3) referred to the binder and aggregate fractions; this is due to the presence, in the aggregate, of carbonate fragments of rocks and single calcite crystals. Other minerals present in the aggregate are quartz (SiO2), plagioclase ((Na,Ca)(Si,Al)4O8), micas (muscovite), and clay minerals (clinochlore and montmorillonite). K feldspars are present only in the samples C5-W and C10-Y. A calcium aluminium silicate (tobermorite, Ca5Si6O16 (OH)2·4(H2O)) was recorded in cores C11-X and C13-X. Tobermorite was also present in the lumps extracted from cores C2b-Y L2, C3-X L, C7-X L, and C13-X L. Vaterite, a polymorph of calcium carbonate, was identified in C7-X and the lumps extracted from C2b-Y and C13-X samples. Tobermorite and vaterite can be found in natural hydraulic lime [38,48,49] and pozzolanic ancient roman mortars [50,51].

Gypsum (CaSO4∙2H2O) was registered in samples C5-Z and C5-W and in the lumps of samples C2b-Y, C3-X, and C13-X. Ettringite (Ca6Al2(SO4)3(OH)12·26(H2O)) was detected in sample C5-Z and can be ascribed to the rection between cement phases and water [52].

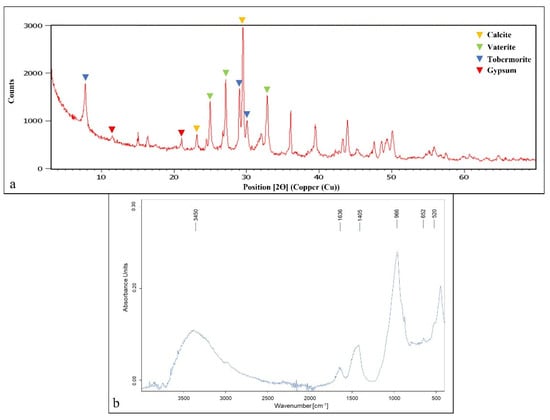

In Figure 4a, a representative diffractometric pattern of a lump extracted from the core of the C2-X sample is shown; calcite, vaterite, tobermorite and gypsum were identified. Moreover, analyzing the lump via FTIR analyses concerning the wavenumber from 4000 to 400 cm−1 (Figure 4b), the XRD composition was confirmed; in fact, the presence of tobermorite is highlighted in the spectra.

Figure 4.

XRD pattern of sample C2-X lump. The most intense peaks for calcite, vaterite, tobermorite and gypsum are indicated (a). FTIR spectra of sample C2-X lump. The vibrational bands of tobermorite are highlighted (b).

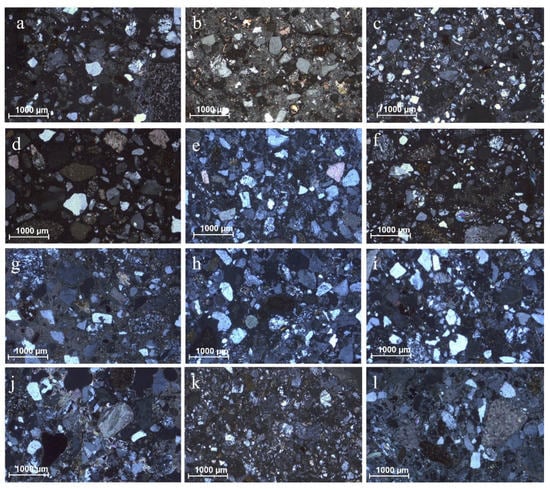

The petrographic observation performed on Lungarno degli Acciaiuoli samples reveals a binder for samples C2-X, C2b-Y, C3-X, and C6-Y with heterogeneous structure and micritic/microsparitic texture (Figure 5a–c,f). Some areas with low birefringence color were also identified.

Figure 5.

Thin section microphotographs (XPL) of some selected samples: C2-X (a), C2b-Y (b), C3-X (c), C5-Z (d), C5-W (e), C6-Y (f), C7-X (g), C7-Y (h), C10-X (i), C10-Y (j), C11-X (k), and C13-X (l).

Lumps are present as remnants both of not well mixed binder and of overburnt limestone fragments in samples C2-X, C2b-Y, and C3-X. The aggregate is very abundant, not well selected, with a heterogeneous grain size distribution, and composed of quartz (mono and polycrystalline), plagioclases, K feldspar, calcite, arenaceous rock fragments, siltstones, and marly limestone fragments.

The sample C5-Z was obtained mixing a hydraulic binder with abundant aggregate (B/A 1/3) and has a very heterogenous composition (Figure 5d). Remains of unhydrated clinker grains have been identified. Quartz (mono and polycrystalline), plagioclases, K feldspar, arenaceous and carbonate rock fragments, siltstones, and magmatic and metamorphic rock fragments were identified under an optical microscope. The grain size distribution varies in the range of 1–2 mm for rock fragments and 100–800 µm for monocrystals. The shape is sub angular/sub rounded. A low macroporosity, due to microcracks and pores of irregular and rounded shape, was observed.

The C6-Y sample also contains few fragments of magmatic rocks (Figure 5f). The rock fragments have a pluri-millimetric size, while the monocrystalline portion ranges from 100 to 500 µm, shaped from sub-angular to sub-rounded. The macroporosity is of medium/high amount due to microcracks and pores of irregular and rounded shape.

The samples C7-X and C7-Y, belonging to Lungarno delle Grazie, were realized with a natural hydraulic binder, in which numerous lumps referred to not well mixed binder and remnants of overburnt marly limestone, identified as the local Alberese limestone, were observed. However, they show some differences: the binder of the C7-X portion has a micritic texture, while the binder of C7-Y varies from micritic/microsparitic to opaque for the presence of areas with low birefringence color (Figure 5g,h). In the first portion the aggregate has a heterogeneous grain size distribution in the range 1–2 mm to 300 µm; in the second one a homogeneous grain size distribution was observed (grain size 800–100 µm).

For samples C10-X and C10-Y and C11-X and C13-X a binder realized with natural hydraulic lime with a heterogeneous structure and micritic/microsparitic texture and with an area with low birefringence color was observed (Figure 5i–l). Some differences have been registered in grain size distribution and composition also for the same mortar type.

In the case of binder, some portions of sample C10-Y are characterized by a relevant recrystallization, while with respect to aggregate, a different amount of carbonate rock fragments was registered with respect to the C10-X portion.

The presence, in some examined samples, of lumps showing Alberese limestone (Figure 5a,b,g,i,l) suggests the use of this stone to produce lime. It is in fact known as the Alberese limestone which has been widely used for the production of lime in the Florentine territory [35,38,41,53]. These stones have a variable amount of clay minerals (from 7 to 26%) and the binder produced by burning the stone with a higher amount of clay minerals develops, after setting, calcite, hydrated calcium silicates, amorphous carbonate, and vaterite able to confer to the mortar good performance and durability.

The results of TGA analyses allow better identification of the hydraulic characteristics of the mortar samples. The temperature range and the relative weight loss represent the most significant parameters for identifying the type of binder making up the mortar mixture. The presence of hydraulic components is registered in the weight loss in the 200–600 °C temperature range; these data refer to hydraulic water (weight loss expressed in %). High values, ranging from 5.20% to 14.10%, were obtained. The decomposition of CO2 is observed in weight loss in the 600–900 °C temperature range; the analyzed samples have relatively low CO2 values between 16.86% and 26.45%, resulting in a material with hydraulic behavior.

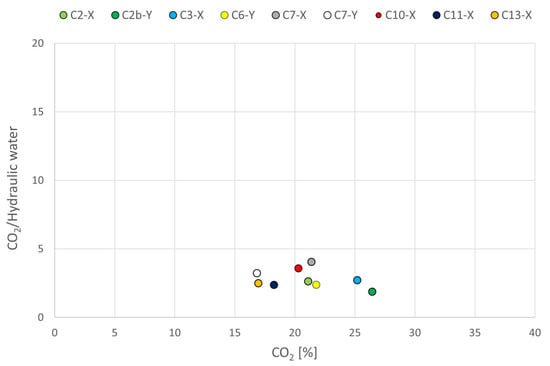

Figure 6 shows a plot of the CO2/H2O ratio versus CO2%; TGA results show that the samples fall in the typical cluster of hydraulic mortars and are characterized by a rather homogeneous hydraulicity.

Figure 6.

Diagram of CO2/H2O vs. CO2 measured on the enriched binders.

All samples present hydraulic water over 7.00%, indicating more condensed and higher strength mortars (in Figure 6 such values are highlighted via TGA results that are concentrated in the lower area of the plot). While the samples C7-X and C7-Y and C10-X, considering that they have a lower hydraulic water value (equal to 5.00%), are slightly away from the others in the plot. These cores come from a portion of the riverbank wall higher than others; a similar hydraulic character is identified.

There are small differences among samples selected at different depths, e.g., C7-X and C7-Y present different values, suggesting that there is variation of hydraulic behavior in depth.

The TGA results combined with the presence of tobermorite in the lump confirm the hydraulic character of the binder.

5.2. Physico-Mechanical Results

Physical and mechanical characterization was performed in order to identify internal defects and inhomogeneities and to assess the resistance and durability of the tested materials [54,55].

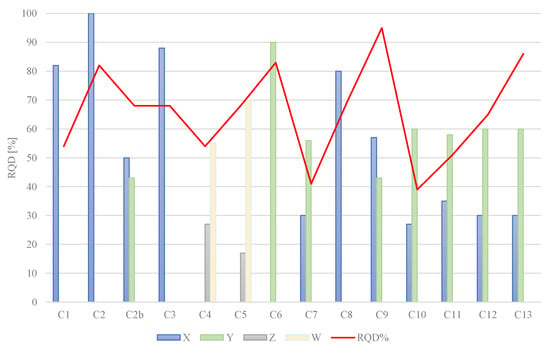

The first macroscopic description of the core samples, taken from the two Lungarni, allowed the identification of 4 different types of mortars; in this way, selection of samples to be analyzed through a complete minero-petrographic and physico-mechanical approach was addressed.

A first mechanical consideration concerns the relationship between the type of mortar and the RQD values. Although a clear correlation between the types of masonry and the RQD cannot be identified, the core samples made of a single type have good and mean RQD values (Figure 7), while the core samples constituted by two types of masonry have lower values, except for C9 and C13, which appear to be the most cohesive. Only C7 and C10 show poor characteristics: these cores come from a portion of the riverbank wall higher than the others and they are characterized by the same binder composition and hydraulic behavior.

Figure 7.

RQD index of core samples, correlated with types of masonry (X, Y, Z, and W).

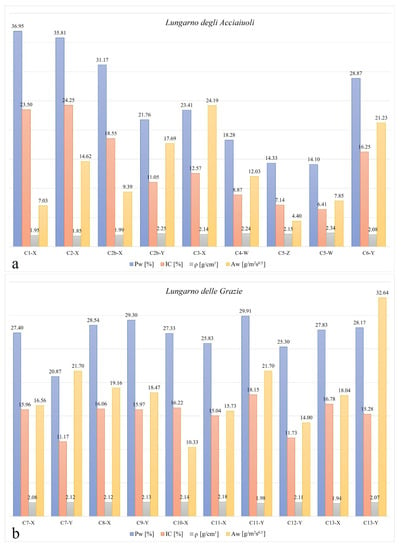

Figure 8 shows the values of effective porosity (Pw%, porosity accessible to water), of the total imbibition coefficient (IC%) and of the density (ρ). The samples were grouped by type of masonry, selected on the basis of macroscopic observation. The effective porosity of Lungarno degli Acciaiuoli samples ranges from the minimum value of 14.10% (C5-W) to the maximum value of 36.95% (C1-X), while in Lungarno delle Grazie samples this value ranges from 20.87% (C7-Y) to 29.91% (C11-Y). The IC% has a similar trend varying from 6.41% to 24.25% (Lungarno degli Acciaiuoli) and from 11.17% to 18.15% (Lungarno delle Grazie). The density is slightly variable, from 1.94 g/cm3 to 2.34 g/cm3, with typical values of mortars [12]. The values of Pw, IC, and ρ, obtained from cores belonging to Lungarno degli Acciaiuoli, are more variable, while the values of Lungarno delle Grazie cores are similar for all the samples.

Figure 8.

Results of physical analyses of test samples of Lungarno degli Acciaiuoli (a) and Lungarno delle Grazie (b). The values reported are effective porosity (Pw%, or porosity accessible to the water), total imbibition coefficient (IC%), density (ρ), and capillary water absorption coefficient (Aw).

In Lungarno degli Acciaiuoli the X type, defined as “mortar with decimetric-sized coarse aggregates”, show Pw values that vary from a minimum of 23.41% to 36.95% and are much greater than the Z and W type samples. In these specimens the effective porosity values vary between 14.10% and 18.28%. IC values have a similar trend of porosity: X and Y type samples have higher IC, while the W and Z type samples show lower values.

In the samples of the Lungarno delle Grazie, for the X type the Pw value varies from 25.83% to 28.54%. These values are similar to those of the Y type. The same behavior is observed for the IC values.

The results of the capillary water absorption test (Figure 8) show that all the specimens have absorption coefficients typical of mortars [18,56]. In general, all the samples show a very rapid imbibition in the initial stages of the test, since the largest porosities are immediately saturated by contact. The Aw values of Lungarno degli Acciaiuoli samples range from a minimum value of 4.40% (C5-Z) to the maximum value of 24.19% (C3-X), while for Lungarno delle Grazie this value ranges from 10.33% (C10-X) to 32.64% (C13-Y). A clear distinction can be observed between the values obtained from the specimens of Z and W samples compared to those of X and Y. The masonry type X has on average slightly lower capillary absorption coefficient values than the Y type, with an average of 13.86 g/m2s0.5 and 19.13 g/m2s0.5, respectively. In the average values, C3-X and C13-Y samples are not included, due to abnormal capillary absorption values. For the sample C3-X, this is due to the presence of a creep that clearly separates it into two portions, so representing an easy access route to water; while for the sample C13-Y, the mortar texture appears to be characterized by a detachment of single grains, due to sample preparation.

In Table 3, the data obtained from UV is reported. The ultrasonic velocity (Vp) of a rubble masonry depends on: the quality of mortar, the type and size of coarse aggregate, and the filling and cohesion properties between mortar and aggregate. The Vp ranges from the maximum value of 3512 m/s to the minimum value of 2420 m/s. This wide range is due to the heterogeneity of the investigated samples, which are composed of coarse aggregate, void, and mortar; in fact, while the stone can be characterized by Vp values of about 4500 m/s [54,55], the mortar can be represented by lower velocity. To estimate the contribution of these stones with respect to the whole mortar and voids, the ratios between stone fragments and mortar were calculated for each investigated sample (Table 3). The Vp values, in general, indicate a good degree of cohesion of the material with few voids and a rather high adhesion between the mortar and the coarse aggregate.

Table 3.

Results of mechanical analyses of test samples.

The average Vp values of the different types of mortar identified in the macroscopic classification are similar: the X and Y types present a similar velocity (3011 m/s and 3040 m/s), while Vp values of the Z and W types are similar (3379 and 3449 m/s). On average, the Vp values of the Lungarno degli Acciaiuoli samples (3217 m/s) are greater than that of the Lungarno delle Grazie (2952 m/s).

In addition, the UC results depend on the quality of the mortar and the quantity of the coarse aggregate. The average values of the mechanical parameters are summarized in Table 3. Concerning the compressive strength (σ), the average values of the Lungarno degli Acciaiuoli samples vary from 40 MPa to 15 MPa, and that of Lungarno delle Grazie samples from 29 MPa to 10 MPa: the strength of the Lungarno degli Acciaiuoli mortars is 15% greater than that of the other Lungarno mortars. This result highlights that the minor values of compressive strength are derived from historical mortars, while the major values depend on the contribution of modern mortars present in Lungarno degli Acciaiuoli, in particular C4 and C5 cores. Considering the different types of mortars, the type X and Y show a different compressive strength (24 MPa and 20 MPa), values rather lower than the other types, Z and W, which show the same strength of 37 MPa.

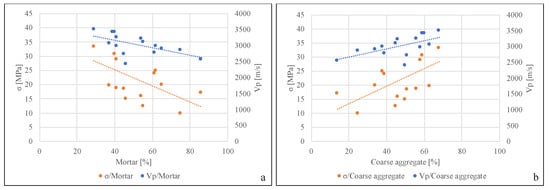

If the mechanical parameters of the samples are compared with the percentages of fine mortar and coarse aggregates, the following correlations are obtained: the quantity of mortar and the mechanical parameters are inversely proportional (Figure 9a), while the quantity of coarse aggregate and the mechanical parameters are directly correlated (Figure 9b). For example, the sample C2b-X shows high values of Vp and σ; indeed, it is composed of 68% of coarse aggregate and only 29% of mortar. On the contrary, the C13-Y sample, consisting of 25% of coarse aggregate and 75% of mortar, shows lower Vp and σ values. The amount of voids is always less than 5%, so they do not significantly affect the results of the mechanical tests.

Figure 9.

Diagram of correlation between σ, Vp, and % of fine portion of core samples (a); σ, Vp, and % of coarse aggregate (b).

5.3. Final Remarks

Previous studies on Florentine riverbanks are focused on the stabilization of walls following collapse events and on the geophysical survey and geotechnical characterization [16,17], providing a reconstruction of the lithological sequence and defining the geotechnical characteristics of the materials involved in the failure. Other studies conducted on historic riverbanks in Italy, aimed at providing guidelines for conservation, propose a combination of on-site and laboratory investigations [57]. However, the minero-petrographical aspects are little deepened. Otherwise, in this study, we characterized the masonry of the Florentine riverbanks, deepening the minero-petrographic features, to evaluate the total properties and to estimate internal defects and inhomogeneities of the masonry.

To summarize the minero-petrographic and physico-mechanical results, the following observations for each masonry type are reported:

- -

- Type X (historic mortar with decametric-sized coarse aggregates) is located both in the Lungarno degli Acciaiuoli and in the Lungarno delle Grazie. The mortar consists of a natural hydraulic lime binder produced through traditional technologies, suggesting a historical origin. The last documented interventions on the riverbanks of Lungarno degli Acciaiuoli and Lungarno delle Grazie date back to the 13th century, but probably some restoration works were realized in the past. The hydraulic characteristics allow hardening and preservation in time in conditions of high humidity or in an underwater environment.

The riverbanks built with this masonry type are defined as “core” structures or rubble masonry. In general, the X samples are characterized by a natural hydraulic lime mixed with an aggregate with variable composition. The macroporosity is medium/high due to pores of irregular shape. From the physical tests carried out on the samples, it is observed that the effective porosity and the total imbibition coefficient are quite high (29.36% and 17.66%, respectively) as well as the capillary water absorption, which is medium-high (13.86 g/m2s0.5). Ultrasonic investigations return values compatible with materials characterized by good coherence and toughness. The amount of coarse aggregate estimated of this masonry type is medium/high (X has an average of 60% of coarse aggregate). The presence of decimetric-sized coarse aggregates does not represent a weakness of the material, since there is a good adhesion between the fine mortar fraction and the stone fragments. The mechanical strength average value obtained from the compression tests is about σ = 24 MPa, confirming the level of cohesion shown by the results of the ultrasonic tests. The physico-mechanical characteristics are suitable for carrying out the riverbank structural function. Although filling material is submitted when completely saturated, for the physical properties, the characterization results demonstrate masonry stability.

- -

- Type Y (historic mortar with centimetric-sized coarse aggregates) is located both in the Lungarno degli Acciaiuoli and in the Lungarno delle Grazie; as in the X type, the mortar has natural hydraulic lime binder (obtained burning Pietra Alberese, identified by under-burnt fragments) and historical origin. The core samples, which come from the higher portion of the riverbank wall, probably were built successively. High masonry was more probably destroyed during the floods.

The minero-petrographic, effective porosity, and total imbibition coefficient results show for both types, X and Y, the same characteristics, so all masonry with type Y was composed of historical mortar. In fact, in the samples, lumps referring to Alberese limestone were observed. These tests were carried out on a fine fraction of mortar samples; therefore, most likely the embankment walls are built with the same mortar and differ only by macroscopical aspects, as type X has decimetric aggregates and type Y centimetric. There is a slight difference in the capillary water absorption results, which are higher (19.13 g/m2s0.5) for the Y type, probably due to the greater amount of mortar present in the samples. The samples used for the mechanical tests are representative of both macroscopic components, and the percentage of coarse aggregate is lower than type X (on average 40%). This composition affects the compressive strength, which is σ = 20 MPa. However, ultrasonic test results show that strong cohesion between the mortar and coarse aggregate is present, confirming the good properties of masonry. The hydraulic behavior observed by TGA results verified such properties.

- -

- Types Z and W (modern mortar with millimeter-sized coarse aggregates and modern mortar with centimeter-sized coarse aggregates) are only present in the C4 and C5 cores of the Lungarno degli Acciaiuoli, corresponding to the portion of the embankment restored after the destruction of 1966 (Figure 1b). For types Z and W, the petrographic analysis shows a binder with heterogeneous structure and micritic/microsparitic texture and remains of unhydrated clinker; the aggregate composition is similar, the B/A is 1/3, and the macroporosity is low. These types have been produced through modern cement technology. The physical analyses show similar results between Z and W; therefore, the effective porosity, the total imbibition coefficient, and the capillary water absorption are much lower than types X and Y. Furthermore, the mechanical test results are equal for both types, but are higher compared to X and Y. These results confirm that the Z and W types are produced with modern and standard technologies, as the analyzed samples have a similar performance.

6. Conclusions

This paper presents the results of an integrated study performed to typify the property of riverbanks, through characterization of masonry composed of coarse aggregates and mortars. The opportunity to take core samples from different masonry of Lungarno delle Grazie and Lungarno degli Acciaiuoli allowed us to characterize raw materials and technologies used for the preparation of the mortars and to highlight similarities or differences among samples belonging to different riverbanks. Particular attention was paid for historical masonry that conduct the function of a load-bearing wall and are submitted to the extreme condition of complete saturation. Moreover, the presence of internal defects and inhomogeneities in the masonry was evaluated. Rubble masonry is internally composed of mortar; a complete mineralogical, petrographic, and physico-mechanical characterization was carried out, using multi-analytical methods. The macroscopic analysis identified at least four main types of masonry present in the various portions of the riverbanks of Lungarno delle Grazie and Lungarno degli Acciaiuoli, in particular: mortar with decimeter-sized coarse aggregates (type X), mortar with centimeter-sized coarse aggregates (type Y), modern mortar with millimeter-sized coarse aggregates (type Z), and modern mortar with centimeter-sized coarse aggregates (type W).

The mortars of the Lungarno delle Grazie consist of a natural hydraulic lime binder, obtained burning a marly limestone and identified by underburnt fragments of a marly limestone, known in the Florentine area as Pietra Alberese (Monte Morello Formation). The aggregate is abundant, its composition is heterogeneous, and it varies from silicate to carbonate. Type X and Y were identified via macroscopic description on the basis of the different grain size distribution of coarse aggregate, but the composition of fine portions (mortars) is almost equal.

Compressive strength and ultrasonic results of X and Y types show results compatible with materials characterized by good compactness and a high level of cohesion. The porosimetric results show rather high values. This aspect must be considered in planning interventions of maintenance and restoration.

In Lungarno degli Acciaiuoli, with the exception of the C4 and C5 samples, which are made from modern hydraulic binder, the other cores extracted appear to be made starting from a natural hydraulic binder that is obtained by cooking marly limestone with the addition of an aggregate of predominantly silicate composition and is well selected and with variable particle size from sample to sample. In this riverbank, the X and Y types of mortars are observed, while the W and Z types are found in cores C4 and C5.

The cores C4 and C5 were obtained from different raw materials, and such compositions develop different technological characteristics: higher values of compressive strength and ultrasonic values and lower porosity values. These samples come from the Lungarno degli Acciaiuoli, which was destroyed during the 1966 flood and later rebuilt. Furthermore, the results of the investigation allow identification of different construction phases, which are compatible with the construction age previous to or after the flood of 1966.

The results demonstrate a good compactness and a high level of cohesion of masonry; such information is useful for planning emergency interventions and for supporting planned restoration activities. This methodology has made it possible for good correlation of multi-analytical techniques, obtaining consistent and useful results for the evaluation of the properties of masonry. Such methodology could be extended to the other riverbanks of Florence or other historic riverbanks in other sites.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/app12105200/s1, Table S1: Mineralogical composition (semiquantitative data) of mortars and selected lumps (L); Table S2: Petrographic description of core samples.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.C., E.C., T.S., I.C. and C.A.G.; methodology, S.C., E.C. and T.S.; validation, S.C., E.C., T.S. and I.C.; investigation, S.C., E.C., T.S., I.C. and C.A.G.; data curation, S.C., T.S. and I.C.; writing—original draft preparation, S.C., T.S., I.C. and E.C.; writing—review and editing, S.C.; visualization, S.C. and T.S.; supervision, E.C. and C.A.G.; funding acquisition, E.C. and C.A.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

This work comes from the collaboration between the Department of Earth Science of the University of Florence, the National Research Council of Italy, and Upper Valdarno Civil Engineering of Tuscany Region. The authors would like to thank the technicians of Upper Valdarno Civil Engineering for the support and collaboration during the collection of core samples.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders agree to publish the results.

References

- Rovero, L.; Fratini, F. The Medina of Chefchaouen (Morocco): A survey on morphological and mechanical features of the masonries. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 47, 465–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovero, L.; Alecci, V.; Mechelli, J.; Tonietti, U.; De Stefano, M. Masonry walls with irregular texture of L’Aquila (Italy) seismic area: Validation of a method for the evaluation of masonry quality. Mater. Struct. 2016, 49, 2297–2314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akcay, C.; Sayin, B.; Yildizlar, B. The conservation and repair of historical masonry ruins based on laboratory analyses. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 132, 383–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sýkora, M.; Diamantidis, D.; Holický, M.; Marková, J.; Rózsás, Á. Assessment of compressive strength of historic masonry using non-destructive and destructive techniques. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 193, 196–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boschi, S.; Galano, L.; Vignoli, A. Mechanical characterisation of Tuscany masonry typologies by in situ tests. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 2019, 17, 413–438. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10518-018-0451-4 (accessed on 18 August 2018). [CrossRef]

- Drdácký, M.; Fratini, F.; Frankeová, D.; Slížková, Z. The Roman mortars used in the construction of the Ponte di Augusto (Narni, Italy)—A comprehensive assessment. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 38, 1117–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borri, A.; Corradi, M.; Castori, G.; De Maria, A. A method for the analysis and classification of historic masonry. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 2015, 13, 2647–2665. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10518-015-9731-4 (accessed on 6 February 2015). [CrossRef]

- Franzini, M.; Leoni, L.; Lezzerini, M.; Sartori, F. The mortar of the “Leaning Tower” of Pisa: The product of a medieval technique for preparing high-strength mortars. Eur. J. Mineral. 2000, 12, 1151–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanas, J.; Sirera, R.; Alvarez, J.I. Study of the mechanical behavior of masonry repair lime-based mortars cured and exposed under different conditions. Cem. Concr. Res. 2006, 36, 961–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Papayianni, I. The longevity of old mortars. Appl. Phys. A Mater. Sci. Process. 2006, 83, 685–688. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00339-006-3523-2 (accessed on 4 April 2006). [CrossRef]

- Ponce-Anton, G.; Arizzi, A.; Zuluaga, M.C.; Cultrone, G.; Ortega, L.A.; Mauleon, J.A. Mineralogical, textural and physical characterization to determine deterioration susceptibility of Irulegi Castle lime mortars (Navarre, Spain). Materials 2019, 12, 584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Moropoulou, A.; Bakolas, P.; Moundoulas, E.; Aggelakopoulou, E. Reverse engineering: A proper methodology for compatible restoration of mortars. In Proceedings of the Workshop on Repair Mortars for Historic Masonries, RILEM Technical Committee, Delft, The Netherlands, 26–28 January 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Moropoulou, A.; Labropoulos, K.C.; Delegou, E.T.; Karoglou, M.; Bakolas, A. Non-destructive techniques as a tool for the protection of built cultural heritage. Constr. Buil. Mater. 2013, 48, 1222–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolopoulou, M.; Aggelakopoulou, E.; Bakolas, A.; Moropoulou, A. Compatible mortars for the sustainable conservation of stone in masonries. In Advanced Materials for the Conservation of Stone, 1st ed.; Hosseini, M., Karapanagiotis, I., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 97–123. [Google Scholar]

- Lugli, S.; Caroselli, M.; Marchetti Dori, S.; Vandelli, V.; Marzani, G.; Segattini, R.; Bianchi, C.; Weber, J. Building materials and degradation phenomena of the Finale Emilia Town Hall (Modena): An archaeometric study for the restoration project after the 2012 earthquake. Period. Di Mineral. 2016, 85, 59–67. [Google Scholar]

- Pazzi, V.; Lotti, A.; Chiara, P.; Lombardi, L.; Nocentini, M.; Casagli, N. Monitoring of the vibration induced on the Arno masonry embankment wall by the conservation works after the 25 May 2016 riverbank landslide. Geoenviron. Disasters 2017, 4, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Morelli, S.; Pazzi, V. Characterization and geotechnical investigations of a riverbank failure in Florence, Italy, an UNESCO World Heritage Site. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. 2020, 146, 05020009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragon, G.; Aragon, A.; Santamaria, A.; Esteban, A.; Fiol, F. Physical and mechanical characterization of a commercial rendering mortar using destructive and non-destructive techniques. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 224, 835–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsen, J. Microscopy of historic mortars—A review. Cem. Concr. Res. 2006, 36, 1416–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moropoulou, A.; Bakolas, A.; Bisbikou, K. Characterization of ancient, byzantine and later historic mortars by thermal and X-ray diffraction techniques. Thermochim. Acta 1995, 269, 779–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miriello, D.; Antonelli, F.; Apollaro, C.; Bloise, A.; Bruno, N.; Catalano, M.; Columbu, S.; Crisci, G.M.; De Luca, R.; Lezzerini, M.; et al. A petro-chemical study of ancient mortars from the archaeological site of Kyme (Turkey). Per. Miner. 2015, 84, 497–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miriello, D.; Bloise, A.; Crisci, G.M.; De Luca, R.; De Nigris, B.; Martellone, A.; Osanna, M.; Pace, R.; Pecci, A.; Ruggieri, N. New compositional data on ancient mortars and plasters from Pompeii (Campania—Southern Italy): Archaeometric results and considerations about their time evolution. Mater. Charact. 2018, 146, 189–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccardi, M.P.; Lezzerini, M.; Carò, F.; Franzini, M.; Messiga, B. Microtextural and microchemical studies of hydraulic ancient mortars: Two analytical approaches to understand pre-industrial technology processes. J. Cult. Herit. 2007, 8, 350–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rampazzi, L.; Colombini, M.P.; Conti, C.; Corti, C.; Lluveras-Tenorio, A.; Sansonetti, A.; Zanaboni, M. Technology of medieval mortars: An investigation into the use of organic additives. Archaeometry 2016, 58, 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, I.; Macedo, M.F.; Vermeulen, F.; Corsi, C.; Santos Silva, A.; Rosado, L.; Candeias, A.; Mirao, J. A Multidisciplinary approach to the study of archaeological mortars from the Town of Ammaia in the Roman Province of Lusitania (Portugal): Archaeological mortars from the Roman town of Ammaia (Lusitania; Portugal). Archaeometry 2014, 56, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Secco, M.; Previato, C.; Addis, A.; Zago, G.; Kamsteeg, A.; Dilaria, S.; Canovaro, C.; Artioli, G.; Bonetto, J. Mineralogical clustering of the structural mortars from the Sarno Baths, Pompeii: A tool to interpret construction techniques and relative chronologies. J. Cult. Herit. 2019, 40, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Monte, E.; Boschi, S.; Vignoli, A. Prediction of compression strength of ancient mortars through in situ drilling resistance technique. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 237, 117563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yang, S.; Gu, R.; Cao, S. New local compression test to estimate in situ compressive strength of masonry mortar. J. Test. Eval. 2016, 44, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelà, L.; Roca, P.; Aprile, A. Combined in-situ and laboratory minor destructive testing of historical mortars. Int. J. Archit. Herit. 2018, 12, 334–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanelli, G. Firenze, Architettura e Città. Atlante; Vallecchi: Florence, Italy, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Balzanetti Steiner, G. Tra Città e Fiume i Lungarni di Firenze; Alinea: Florence, Italy, 1989; p. 142. [Google Scholar]

- Villani, G. Cronica di Giovanni Villani: A Miglior Lezione Ridotta, 1st ed.; Sansoni: Florence, Italy, 1537. [Google Scholar]

- Pecchioni, E.; Fratini, F.; Pandeli, E.; Cantisani, E.; Vettori, S. Pietraforte, the Florentine building material from the Middle Ages to contemporary architecture. Episodes 2021, 44, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fratini, F.; Pecchioni, E.; Cantisani, E.; Rescic, S.; Vettori, S. Pietra Serena: The stone of the Renaissance. Geolog. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 2014, 407, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fratini, F.; Cantisani, E.; Pecchioni, E.; Pandeli, E.; Vettori, S. Pietra Alberese: Building material and stone for lime in the Florentine Territory (Tuscany, Italy). Heritage 2020, 3, 1520–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deere, D.U.; Deere, D.W. Rock Quality Designation (RQD) after Twenty Years; Rocky Mountain Consultants, Inc.: Longmont, CO, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Pecchioni, E.; Fratini, F.; Cantisani, E. Atlas of the Ancient Mortars in Thin Section under Optical Microscope, 2nd ed.; Nardini: Florence, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Cantisani, E.; Calandra, S.; Barone, S.; Caciagli, S.; Fedi, M.; Garzonio, C.A.; Liccioli, L.; Salvadori, B.; Salvatici, T.; Vettori, S. The mortars of Giotto’s Bell Tower (Florence, Italy): Raw materials and technologies. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 267, 120801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arizzi, A.; Cultrone, G. Mortars and plasters—How to characterise hydraulic mortars. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 2021, 13, 1–22. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12520-021-01404-2 (accessed on 6 August 2021). [CrossRef]

- Cantisani, E.; Fratini, F.; Pecchioni, E. Optical and Electronic Microscope for Minero-Petrographic and Microchemical Studies of Lime Binders of Ancient Mortars. Minerals 2022, 12, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calandra, S.; Cantisani, E.; Vettori, S.; Ricci, M.; Agostini, B.; Garzonio, C.A. The San Giovanni Baptistery in Florence (Italy): Assessment of the State of Conservation of Surfaces and Characterization of Stone Materials. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 4050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruni, S.; Cariati, F.; Fermo, P.; Cairati, P.; Alessandrini, G.; Toniolo, L. White lumps in fifth- to seventeenth-century A.D. mortars from Northern Italy. Archaeometry 1997, 39, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, J.; Leslie, A.B.; Callebaut, K. The petrography of lime inclusions of historic lime based mortars. In Proceedings of the 8th Euroseminar on Microscopy Applied to Building Materials, Annales Geologiques des Pays Helleniques, Athens, Greece, 4–7 September 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bakolas, A.; Biscontin, G.; Contardi, V.; Franceschi, E.; Moropoulou, A.; Palazzi, D.; Zendri, E. Thermoanalytical research on traditional mortars in Venice. Thermochim. Acta 1995, 269, 817–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maravelaki-Kalaitzaki, P.; Bakolas, A.; Moropoulou, A. Physico-chemical study of Cretan ancient mortars. Cem. Concr. Res. 2003, 33, 651–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNI EN 1936. Natural Stone Test Methods—Determination of the Real and Apparent Density and of the Total and Open Porosity; Ente Nazionale Italiano di Normazione: Milano, Italy, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- UNI EN 15801. Conservation of Cultural Property—Test Methods—Determination of Water Absorption by Capillarity; Ente Nazionale Italiano di Normazione: Milano, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Forster, A.M. How Hydraulic Lime Binders Work. Hydraulicity for Beginners and the Hydraulic Lime Family; Scottish Lime Center: Edinburgh, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lezzerini, M.; Ramacciotti, M.; Cantini, F.; Fatighenti, B.; Antonelli, F.; Pecchioni, E.; Fratini, F.; Cantisani, E.; Giamello, M. Archaeometric study of natural hydraulic mortars: The case of the Late Roman Villa dell’Oratorio (Florence, Italy). Archaeol. Anthrop. Sci. 2017, 9, 603–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, M.D.; Moon, J.; Gotti, E.; Taylor, R.; Chae, S.R.; Kunz, M.; Emwas, A.H.; Meral, C.; Guttmann, P.; Levitz, P.; et al. Material and elastic properties of Al-tobermorite in ancient roman seawater concrete. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2013, 96, 2598–2606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, M.D.; Mulcahy, S.R.; Chen, H.; Li, Y.; Li, Q.; Cappelletti, P.; Wenk, H.R. Phillipsite and Al-tobermorite mineral cements produced through low-temperature water-rock reactions in Roman marine concrete. Am. Mineral. 2017, 102, 1435–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Collepardi, M. Ettringite formation and sulfate attack on concrete. J. Am. Concr. Inst. 2001, 200, 21–38. [Google Scholar]

- Cantisani, E.; Falabella, A.; Fratini, F.; Pecchioni, E.; Vettori, S.; Antonelli, F.; Giamello, M.; Lezzerini, M. Production of the Roman Cement in Italy: Characterization of a raw material used in Tuscany between 19th and 20th century and its comparison with a commercialized French stone material. Int. J. Archit. Herit. 2018, 12, 1038–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvatici, T.; Calandra, S.; Centauro, I.; Pecchioni, E.; Intrieri, E.; Garzonio, C.A. Monitoring and Evaluation of Sandstone Decay Adopting Non-Destructive Techniques: On-Site Application on Building Stones. Heritage 2020, 3, 1287–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centauro, I.; Vitale, J.G.; Calandra, S.; Salvatici, T.; Natali, C.; Coppola, M.; Intrieri, E.; Garzonio, C.A. A Multidisciplinary Methodology for Technological Knowledge, Characterization and Diagnostics: Sandstone Facades in Florentine Architectural Heritage. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 4266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veiga, R.; Velosa, A.; Magalhaes, A. Experimental applications of mortars with pozzolanic additions: Characterization and performance evaluation. Constr. Build. Mater. 2009, 23, 318–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boriani, M.; Bortolotto, S.; Giambruno, M.; Binda, L.; Tedeschi, C. The Naviglio Grande in Milan: A study to provide guidelines for conservation. Wit Trans. Built Environ. 2005, 83, 631–641. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).