Vocal Synchrony of Robots Boosts Positive Affective Empathy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

2.1. Imitating a Strategy of Human-Human Communication

2.2. Synchrony and Affective Empathy

2.3. Affective Empathy between Humans and Robots

2.4. Research Questions and Hypotheses

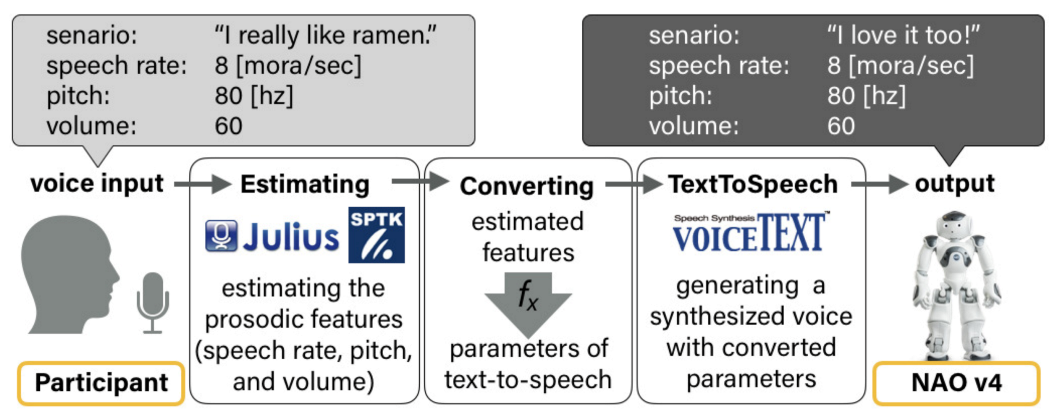

3. Implementation of the Vocal Synchrony

3.1. Details of the Estimation Methods for Prosodic Features

- あらゆる現実をすべて自分のほうへねじまげたのだ / I twisted all the reality toward myself. (Arayuru genjitsu wo subete jibun no hou e nejimageta noda)

- テレビゲームやパソコンでゲームをして遊ぶ / I play video games and games on my computer. (Terebi ge-mu ya pasokon de ge-mu wo shite asobu)

- 救急車が十分に動けず救助作業が遅れている / Ambulance is not moving enough, and rescue work is delayed. (Kyuukyuusha ga jyubun ni ugokezu kyuujyosagyou ga okureteiru)

- 老人ホームの場合は健康器具やひざ掛けだ / In case of a nursing home, it is a health appliance or a rug. (Roujin ho-mu no baai wa kenkoukigu ya hizakake da)

- 嬉しいはずがゆっくり寝てもいられない / I should be happy, but I can’t sleep slowly. (Ureshii hazuga yukkuri netemo irarenai)

- (i)

- The corresponding voice synthesis parameter of VoiceText is set to 50 (speech speed is 70) and outputs synthesized speech. At this time, the parameters other than those used for deriving the calibration formula are fixed to 100.

- (ii)

- The synthesized speech output from the Nao humanoid robot’s speaker is input using a microphone, and the prosodic features are then estimated. At this time, the volume setting of Nao is fixed at 65%.

- (iii)

- The estimated prosodic features and the speech synthesis parameters are recorded.

- (iv)

- Steps (i–iii) are repeated three times for each of the five sentences.

- (v)

- The corresponding speech synthesis parameters are changed by 10, and steps (i–iv) are conducted.

- (vi)

- Steps (i–v) are repeated until the parameter is 200 and the speech rate is 150.

3.2. System Flow of Vocal Synchrony

4. Experimental Conditions

4.1. Participants

4.2. Experimental Design

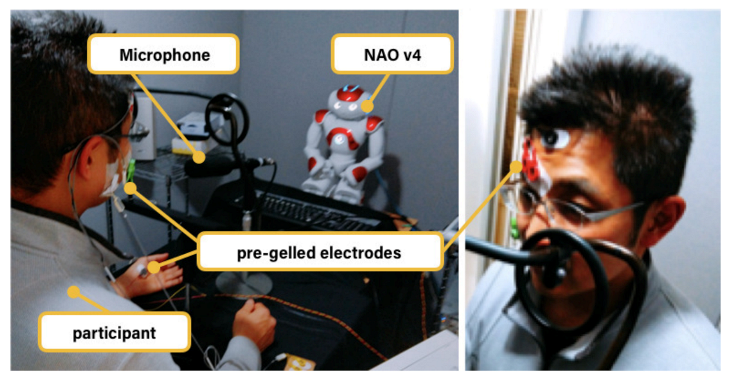

4.3. Apparatus

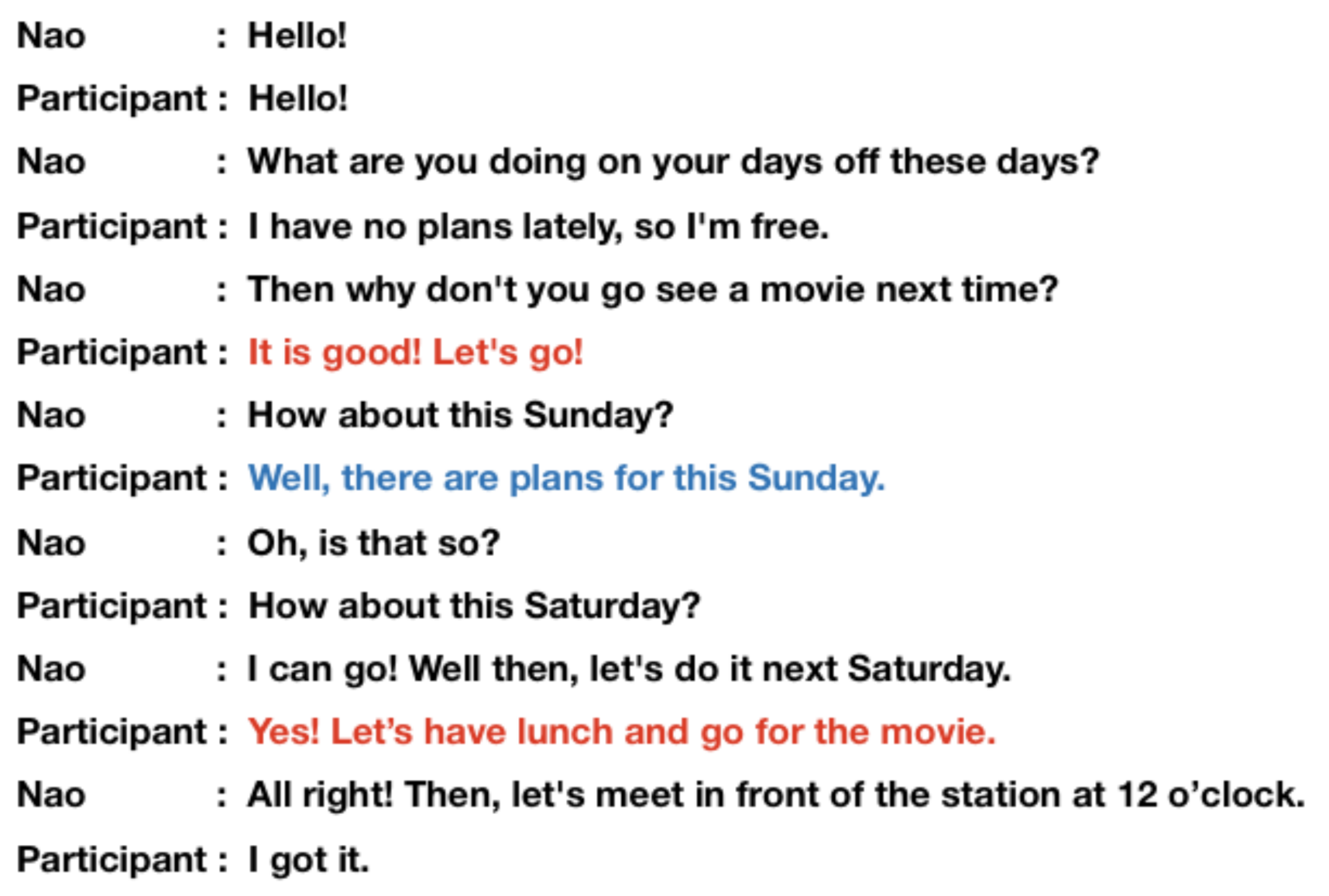

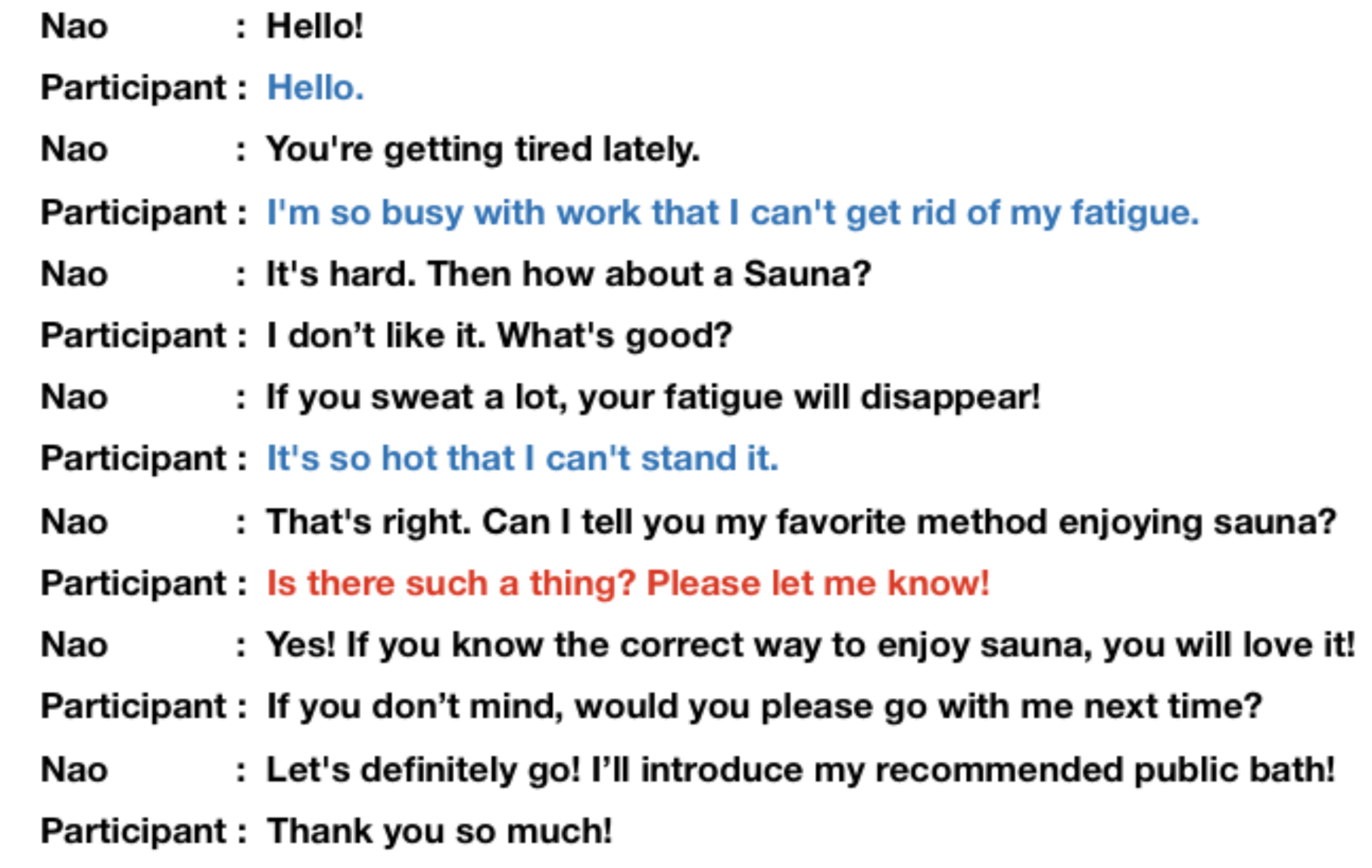

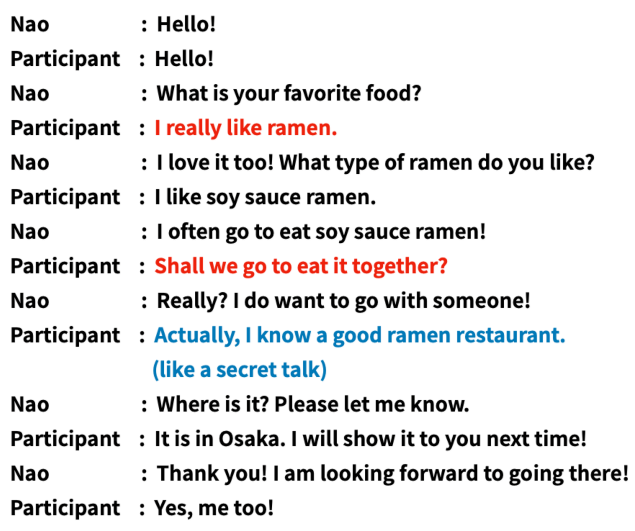

4.4. Dialog Scenario

4.5. Procedure

4.6. Questionnaire

- Did you feel friendliness?

- Did you feel fun?

- Did you feel that the robot was listening to you?

- Did you feel an emotional connection?

- Did you feel the motivation to use?

- Did you feel synchrony?

- Which robot did you like (after finishing each scenario)?

4.7. Data Analysis

4.7.1. Preprocessing

4.7.2. Statistical Analysis

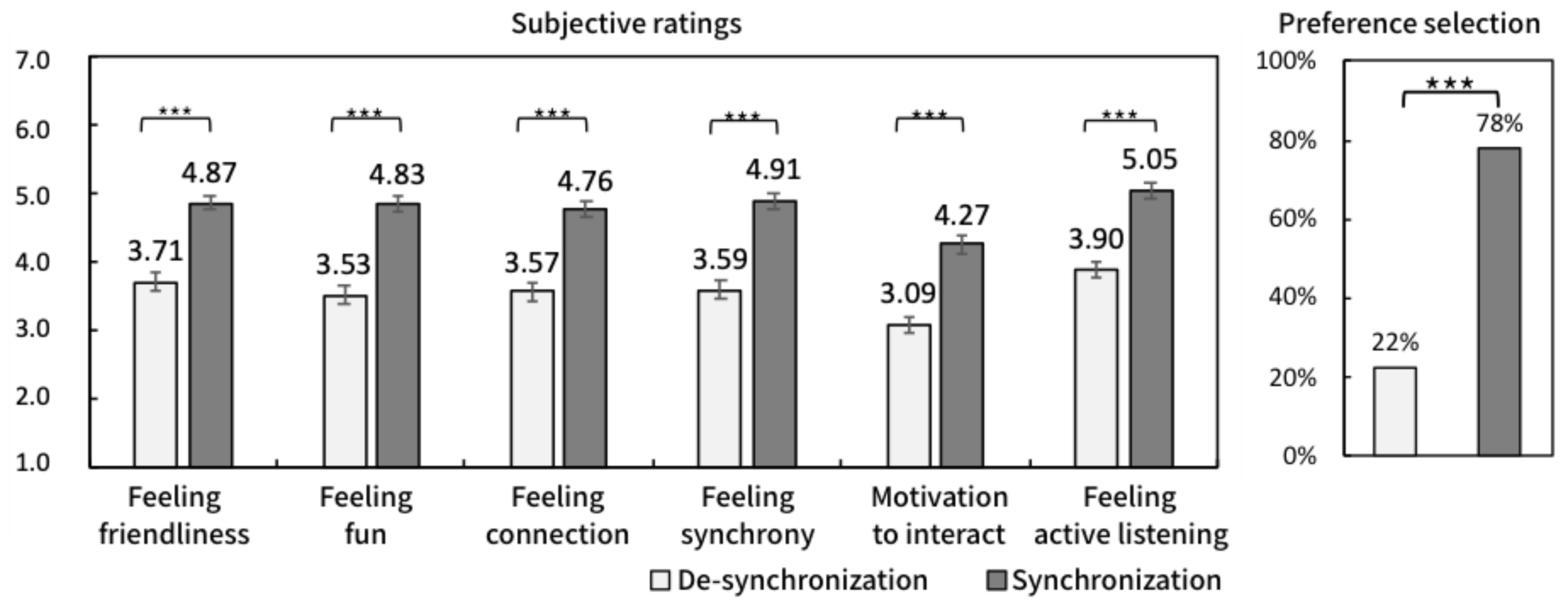

5. Results

5.1. Subjective Responses

5.2. Physiological Responses

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Content of Scenarios

- Scenario set 1:

- self-introduction, favorite food, and movie invitation

- Scenario set 2:

- self-catering, dinner invitation, and lack of sleep

- Scenario set 3:

- favorite sports, summer vacation events, and sauna

- Scenario set 4:

- part-time job, long vacation, and lost wallet

Appendix B. Accuracy of Vocal Synchrony

- An experimenter recorded the voices of seven humans with various prosodic features (i.e., fast, slow, high, low, large, small, neutral). The content of the utterance was “あらゆる現実をすべて自分のほうへねじまげたのだ / I twisted all the reality toward myself.”

- Each voice was estimated using the prosodic parameters (i.e., speech rate, pitch, and volume).

- Trials 1 and 2 were repeated five times each, and the average value for each voice was used as the prosodic feature of a human in each voice.

- Based on the prosodic features of a human, seven types of synthesized voices of robots were generated using VoiceText.

- Similar to that for the human voice, the average of five trials was used as the prosodic feature of the robot.

| Sample | Speaker | Speech Rate | Pitch | Volume | Cosine Similarity | Correlation Coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fast | HUMAN | 124.24 | 98.16 | 101.02 | 0.9999 | 0.9954 |

| ROBOT | 125.00 | 98.05 | 103.59 | |||

| slow | HUMAN | 83.43 | 98.74 | 100.53 | 0.9997 | 0.9944 |

| ROBOT | 81.11 | 98.93 | 103.68 | |||

| high | HUMAN | 98.53 | 123.85 | 102.76 | 0.9998 | 0.9799 |

| ROBOT | 97.30 | 123.96 | 106.77 | |||

| low | HUMAN | 102.03 | 79.13 | 98.75 | 0.9999 | 0.9969 |

| ROBOT | 98.53 | 78.95 | 97.33 | |||

| large | HUMAN | 101.58 | 98.78 | 124.22 | 0.9994 | 0.9905 |

| ROBOT | 97.71 | 99.06 | 129.51 | |||

| small | HUMAN | 101.58 | 98.81 | 73.82 | 0.9998 | 0.9936 |

| ROBOT | 98.53 | 99.14 | 75.46 | |||

| neutral | HUMAN | 97.71 | 99.33 | 99.97 | 0.9999 | 0.8868 |

| ROBOT | 97.71 | 99.03 | 102.18 |

References

- Leite, I.; Martinho, C.; Paiva, A. Social robots for long-term interaction: A survey. Int. J. Soc. Robot. 2013, 5, 291–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breazeal, C. A motivational system for regulating human-robot interaction. In Proceedings of the 15th National Conference on Artificial Intellilgence, Madison, WI, USA, 26–30 July 1998; pp. 54–61. [Google Scholar]

- Gockley, R.; Bruce, A.; Forlizzi, J.; Michalowski, M.; Mundell, A.; Rosenthal, S.; Sellner, B.; Simmons, R.; Snipes, K.; Schultz, A.C.; et al. Designing robots for long-term social interaction. In Proceedings of the 2005 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Edmonton, AB, Canada, 2–6 August 2005; pp. 1338–1343. [Google Scholar]

- De Vignemont, F.; Singer, T. The empathic brain: How, when and why? Trends Cogn. Sci. 2006, 10, 435–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, J.A.; Schwartz, R. Empathy present and future. J. Soc. Psychol. 2019, 159, 225–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krämer, N.; Rosenthal-von der Pütten, A.M.; Eimler, S. Human-Agent and Human-Robot Interaction Theory: Similarities to and Differences from Human-Human Interaction. Stud. Comput. Intell. 2012, 396, 215–240. [Google Scholar]

- Cassell, J.; Sullivan, J.; Churchill, E.; Prevost, S. Embodied Conversational Agents; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Edlund, J.; Gustafson, J.; Heldner, M.; Hjalmarsson, A. Towards human-like spoken dialogue systems. Speech Commun. 2008, 50, 630–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nass, C.I.; Brave, S. Wired for Speech: How Voice Activates and Advances the Human-Computer Relationship; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Delaherche, E.; Chetouani, M.; Mahdhaoui, A.; Saint-Georges, C.; Viaux, S.; Cohen, D. Interpersonal synchrony: A survey of evaluation methods across disciplines. IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput. 2012, 3, 349–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chartrand, T.L.; Lakin, J.L. The antecedents and consequences of human behavioral mimicry. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2013, 64, 285–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cirelli, L.K. How interpersonal synchrony facilitates early prosocial behavior. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2018, 20, 35–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chartrand, T.L.; Bargh, J.A. The chameleon effect: The perception—Behavior link and social interaction. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 76, 893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hove, M.J.; Risen, J.L. It’s all in the timing: Interpersonal synchrony increases affiliation. Soc. Cogn. 2009, 27, 949–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Baaren, R.B.; Holland, R.W.; Kawakami, K.; Van Knippenberg, A. Mimicry and prosocial behavior. Psychol. Sci. 2004, 15, 71–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revel, A.; Andry, P. Emergence of structured interactions: From a theoretical model to pragmatic robotics. Neural Netw. 2009, 22, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andry, P.; Blanchard, A.; Gaussier, P. Using the rhythm of nonverbal human—Robot interaction as a signal for learning. IEEE Trans. Auton. Ment. Dev. 2010, 3, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaherche, E.; Boucenna, S.; Karp, K.; Michelet, S.; Achard, C.; Chetouani, M. Social coordination assessment: Distinguishing between shape and timing. In IAPR Workshop on Multimodal Pattern Recognition of Social Signals in Human-Computer Interaction; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 9–18. [Google Scholar]

- Boucenna, S.; Gaussier, P.; Andry, P.; Hafemeister, L. A robot learns the facial expressions recognition and face/non-face discrimination through an imitation game. Int. J. Soc. Robot. 2014, 6, 633–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minoru, A. Towards artificial empathy. Int. J. Soc. Robot. 2015, 7, 19–33. [Google Scholar]

- Nadel, J.; Simon, M.; Canet, P.; Soussignan, R.; Blancard, P.; Canamero, L.; Gaussier, P. Human responses to an expressive robot. In Procs of the Sixth International Workshop on Epigenetic Robotics; Lund University: Lund, Sweden, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura, S.; Kimata, D.; Sato, W.; Kanbara, M.; Fujimoto, Y.; Kato, H.; Hagita, N. Positive Emotion Amplification by Representing Excitement Scene with TV Chat Agents. Sensors 2020, 7, 7330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prepin, K.; Pelachaud, C. Shared understanding and synchrony emergence synchrony as an indice of the exchange of meaning between dialog partners. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence, Rome, Italy, 28–30 January 2011; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Riek, L.D.; Paul, P.C.; Robinson, P. When my robot smiles at me: Enabling human-robot rapport via real-time head gesture mimicry. J. Multimodal User Interfaces 2010, 3, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imel, Z.E.; Barco, J.S.; Brown, H.J.; Baucom, B.R.; Baer, J.S.; Kircher, J.C.; Atkins, D.C. The association of therapist empathy and synchrony in vocally encoded arousal. J. Couns. Psychol. 2014, 61, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, B.; Georgiou, P.G.; Imel, Z.E.; Atkins, D.C.; Narayanan, S.S. Modeling therapist empathy and vocal entrainment in drug addiction counseling. In INTERSPEECH; ISCA: Lyon, France, 2013; pp. 2861–2865. [Google Scholar]

- Lord, S.P.; Sheng, E.; Imel, Z.E.; Baer, J.; Atkins, D.C. More than reflections: Empathy in motivational interviewing includes language style synchrony between therapist and client. Behav. Ther. 2015, 46, 296–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurer, R.E.; Tindall, J.H. Effect of postural congruence on client’s perception of counselor empathy. J. Couns. Psychol. 1983, 30, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutinho, J.F.; Silva, P.O.; Decety, J. Neurosciences, empathy, and healthy interpersonal relationships: Recent findings and implications for counseling psychology. J. Couns. Psychol. 2014, 61, 541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadoughi, N.; Pereira, A.; Jain, R.; Leite, I.; Lehman, J.F. Creating prosodic synchrony for a robot co-player in a speech-controlled game for children. In Proceedings of the 2017 ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction, Vienna, Austria, 6–9 March 2017; pp. 91–99. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, N.; Takeuchi, Y.; Ishii, K.; Okada, M. Effects of echoic mimicry using hummed sounds on human–computer interaction. Speech Commun. 2003, 40, 559–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orne, M.T. On the social psychology of the psychological experiment: With particular reference to demand characteristics and their implications. Am. Psychol. 1962, 17, 776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Scott, N.; Walters, G. Current and potential methods for measuring emotion in tourism experiences: A review. Curr. Issues Tour. 2015, 18, 805–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacioppo, J.T.; Berntson, G.G.; Klein, D.J. What is an emotion? The role of somatovisceral afference, with special emphasis on somatovisceral “illusions.” Rev. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1992, 14, 63–98. [Google Scholar]

- Lang, P.J.; Bradley, M.M.; Cuthbert, B.N. Emotion, motivation, and anxiety: Brain mechanisms and psychophysiology. Biol. Psychiatry 1998, 44, 1248–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassell, J.; Bickmore, T. Negotiated collusion: Modeling social language and its relationship effects in intelligent agents. User Modeling User-Adapt. Interact. 2003, 13, 89–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaFrance, M. Posture mirroring and rapport. Interact. Rhythm. Period. Commun. Behav. 1982, 279298, 279–298. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, X.; Nijholt, A. Multimodal embodied mimicry in interaction. In Analysis of Verbal and Nonverbal Communication and Enactment. The Processing Issues; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 147–153. [Google Scholar]

- Ramseyer, F.; Tschacher, W. Nonverbal synchrony in psychotherapy: Coordinated body movement reflects relationship quality and outcome. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2011, 79, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anzalone, S.M.; Boucenna, S.; Ivaldi, S.; Chetouani, M. Evaluating the engagement with social robots. Int. J. Soc. Robot. 2015, 7, 465–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaspari, T.; Lehman, J.F. An Acoustic Analysis of Child-Child and Child-Robot Interactions for Understanding Engagement during Speech-Controlled Computer Games. In Proceedings of the Interspeech 2016, 17th Annual Conference of the International Speech Communication Association, San Francisco, CA, USA, 8–12 September 2016; pp. 595–599. [Google Scholar]

- Street, R.L., Jr. Speech convergence and speech evaluation in fact-finding interviews. Hum. Commun. Res. 1984, 11, 139–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaherche, E.; Chetouani, M. Multimodal coordination: Exploring relevant features and measures. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Workshop on Social Signal Processing, Florence, Italy, 29 October 2010; pp. 47–52. [Google Scholar]

- Giles, H. Accent mobility: A model and some data. Anthropol. Linguist. 1973, 15, 87–105. [Google Scholar]

- Bourhis, R.Y.; Giles, H. The language of intergroup distinctiveness. Lang. Ethn. Intergroup Relat. 1977, 13, 119. [Google Scholar]

- Bilous, F.R.; Krauss, R.M. Dominance and accommodation in the conversational behaviours of same-and mixed-gender dyads. Lang. Commun. 1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappella, J.N.; Planalp, S. Talk and silence sequences in informal conversations III: Interspeaker influence. Hum. Commun. Res. 1981, 7, 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.; Kawahara, T. Recent development of open-source speech recognition engine julius. In Proceedings of the APSIPA ASC 2009: Asia-Pacific Signal and Information Processing Association, 2009 Annual Summit and Conference. Asia-Pacific Signal and Information Processing Association, 2009 Annual Summit and Conference, Sapporo, Japan, 4–7 October 2009; pp. 131–137. [Google Scholar]

- SPTK Working Group. Examples for Using Speech Signal Processing Toolkit Ver. 3.9; SourceForge: San Diego, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- HOYA Corporation. Speech Sythesis voiceText Web API. Available online: http://voicetext.jp/products/vt-webapi/ (accessed on 11 March 2021).

- Masanobu, K.; Takeo, K.; Hiroko, K.; Seiji, N. “Mora method” for objective evaluation of severity of spasmodic dysphonia. Jpn. J. Logop. Phoniatr. 1997, 38, 176–181. [Google Scholar]

- Kurematsu, A.; Takeda, K.; Sagisaka, Y.; Katagiri, S.; Kuwabara, H.; Shikano, K. ATR Japanese speech database as a tool of speech recognition and synthesis. Speech Commun. 1990, 9, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.G.; Buchner, A. G* Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gouaillier, D.; Hugel, V.; Blazevic, P.; Kilner, C.; Monceaux, J.; Lafourcade, P.; Marnier, B.; Serre, J.; Maisonnier, B. The nao humanoid: A combination of performance and affordability. arXiv 2008, arXiv:0807.3223. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, J.A.; Weiss, A.; Mendelsohn, G.A. Affect grid: A single-item scale of pleasure and arousal. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 57, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakii, T. Characteristics of multimedia counseling: A study of an interactive TV system. Shinrigaku Kenkyu Jpn. J. Psychol. 1997, 68, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Tarr, B.; Launay, J.; Dunbar, R.I. Silent disco: Dancing in synchrony leads to elevated pain thresholds and social closeness. Evol. Hum. Behav. 2016, 37, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J. GrandChair: Conversational Collection of Family Stories. Master’s Thesis, MIT Media Arts & Sciences, Cambridge, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Schumann, N.P.; Bongers, K.; Guntinas-Lichius, O.; Scholle, H.C. Facial muscle activation patterns in healthy male humans: A multi-channel surface EMG study. J. Neurosci. Methods 2010, 187, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, W.; Fujimura, T.; Suzuki, N. Enhanced facial EMG activity in response to dynamic facial expressions. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2008, 70, 70–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soderberg, G.L. Selected Topics in Surface Electromyography for Use in the Occupational Setting: Expert Perspectives; US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health: Washington, DC, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Hummel, T.J.; Sligo, J.R. Empirical comparison of univariate and multivariate analysis of variance procedures. Psychol. Bull. 1971, 76, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiske, A.; Henningsen, P.; Buyx, A. Your robot therapist will see you now: Ethical implications of embodied artificial intelligence in psychiatry, psychology, and psychotherapy. J. Med. Internet. Res. 2019, 21, e13216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reich, C.M.; Berman, J.S.; Dale, R.; Levitt, H.M. Vocal synchrony in psychotherapy. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2014, 33, 481–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koole, S.L.; Tschacher, W. Synchrony in psychotherapy: A review and an integrative framework for the therapeutic alliance. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Voice Model | ||

|---|---|---|

| Takeru: Male Model () | Hikari: Female Model () | |

| Speech rate | (0.91) | |

| Pitch | (0.99) | (0.99) |

| Volume | (0.98) | (0.95) |

| Measure | Statistic | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Feeling friendliness | 7.02 | 1.36 | |

| Feeling fun | 8.43 | 1.38 | |

| Feeling connection | 7.35 | 1.30 | |

| Feeling synchrony | 7.40 | 1.43 | |

| Motivation to interact | 7.53 | 1.24 | |

| Feeling active listening | 6.99 | 1.28 | |

| Preference selection | 6.91 | 1.88 | |

| Measure | Statistic | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Corrugator supercilii EMG | 2.02 | 0.027 | 0.54 |

| Zygomatic major EMG | 1.73 | 0.047 | 0.28 |

| SCL | 1.72 | 0.049 | 0.48 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nishimura, S.; Nakamura, T.; Sato, W.; Kanbara, M.; Fujimoto, Y.; Kato, H.; Hagita, N. Vocal Synchrony of Robots Boosts Positive Affective Empathy. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 2502. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11062502

Nishimura S, Nakamura T, Sato W, Kanbara M, Fujimoto Y, Kato H, Hagita N. Vocal Synchrony of Robots Boosts Positive Affective Empathy. Applied Sciences. 2021; 11(6):2502. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11062502

Chicago/Turabian StyleNishimura, Shogo, Takuya Nakamura, Wataru Sato, Masayuki Kanbara, Yuichiro Fujimoto, Hirokazu Kato, and Norihiro Hagita. 2021. "Vocal Synchrony of Robots Boosts Positive Affective Empathy" Applied Sciences 11, no. 6: 2502. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11062502

APA StyleNishimura, S., Nakamura, T., Sato, W., Kanbara, M., Fujimoto, Y., Kato, H., & Hagita, N. (2021). Vocal Synchrony of Robots Boosts Positive Affective Empathy. Applied Sciences, 11(6), 2502. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11062502