1. Introduction

Numerous articles have recently been published in different countries describing atypical lesions of the jaw bones related to treatment with medications based on phosphorus or analogs of its compounds, particularly bisphosphonates (BP) [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6].

According to various authors, the number of medication-related osteonecrosis cases has increased from single clinical cases to a 27% occurrence in the practice of dentistry when using so-called bisphosphonate therapy [

7,

8].

It has been found that, in addition to bisphosphonates, some other classes of drugs (cytostatics, hormones, etc.) are also able to induce specific changes in the bones of the jaw, which often manifest clinically as osteonecrosis. Thus, a more general, separate condition was formulated: medication-related osteonecrosis. Medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw is characterized by pathognomonic symptoms that distinguish it from other inflammatory, dystrophic, and iatrogenic diseases of the orofacial area; therefore, it is reasonable to separate it as an independent nosology that requires comprehensive study.

The definitive pathophysiology of drug-associated osteonecrosis is not clear yet. However, up-to-date articles examine modern theories of the pathogenesis of this nosology. The pathophysiology of the osteonecrotic process in bone tissue is associated with patterns of metabolism and the effects of bisphosphonate drugs prescribed for osteoporosis or bone metastasis. In our article, we examined patients with various types of cancer. Changes in the jaws can occur due to impaired bone remodeling or increased suppression of bone resorption, inhibition of angiogenesis, persistent microtrauma, and the toxic effects of bisphosphonates on soft tissues. From the circulatory system, 20 to 80% of bisphosphonates are absorbed by the bone tissue, and the remainder is rapidly excreted in the urine. The level of bone remodeling of the jaw tissue is quite high; as a result, there is a greater accumulation of bisphosphonates in jaws, especially in the tissues of the lower jaw.

Often, patients who are indicated for radical surgery are classified as AAOMS stage 3, and one of the most common complaints is numbness in the affected area. For example, a study by Fortunato et al., 2018, found that Numb Chin Syndrome (NCS) is a consequence of drug therapy in patients with MRONJ. The results obtained indicate that numbness is a sign of necrosis; therefore, attention should be paid to this complaint, since this indicates a direct relationship between numbness as a diagnostic complaint and osteonecrosis. Numb chin syndrome (NCS) or mental neuropathy (MN) may be the first sign of malignant neoplasm, but also a prodromal sign of MRONJ. Patients belonging to the main group in our study, also complained frequently of numbness in the affected area, which persisted before and after surgery. All of them were previously diagnosed with MRONJ stage 2 or 3 according to AAOMS.

Up-to-date articles, including the studies of Schiodt et al., Giovannacci et al., 2016; Troeltzsch et al., 2016, show that odontogenic infection, as well as peri-implantitis, is a clear risk factor for the development of MRONJ.

It is worth noting that dental practitioners are not sufficiently aware of the risk of osteonecrosis of the jaw in patients treated with BP following oral interventions, which leads to errors in diagnosis and treatment. In particular, the exposure of bone tissue after removal is regarded as exostosis, a sharp edge of the socket, etc. Attempts to eliminate this condition using traditional methods of surgical treatment can aggravate the course of osteonecrosis, leading to an acceleration in its spread, a deterioration in the patient’s quality of life, and a deterioration in the prognosis of the disease [

9,

10].

A specialist diagnosing medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (MRONJ) should first rule out neoplastic bone infiltration and osteomyelitis within the framework of differential diagnosis. For the clinical diagnosis of osteonecrosis of the jaw, the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons recommends [

11] that patients meet several key criteria that distinguish this diagnosis from other inflammatory diseases. These include the absence of radiation therapy, a history of bisphosphonate treatment, and an area of necrotic bone tissue in the oral cavity or a fistula probed to the bone that persists for eight weeks or more [

12].

The prevalence of MRONJ varies in different countries, but it is reliably known that 1–10% of patients with cancer who receive intravenous bisphosphonates acquire it within a few months after the start of treatment, with two-thirds of cases involving the lower jaw. During surgery, areas of bone necrosis are resected, along with some surrounding normal tissue, to eliminate the spread of the pathological process; however, it should be remembered that radical surgery leads to a change in the quality of life of patients in the postoperative period.

Goal: To conduct a comparative analysis of the quality of life after radical surgery of the jaw in patients with medication-related osteonecrosis.

2. Materials and Methods

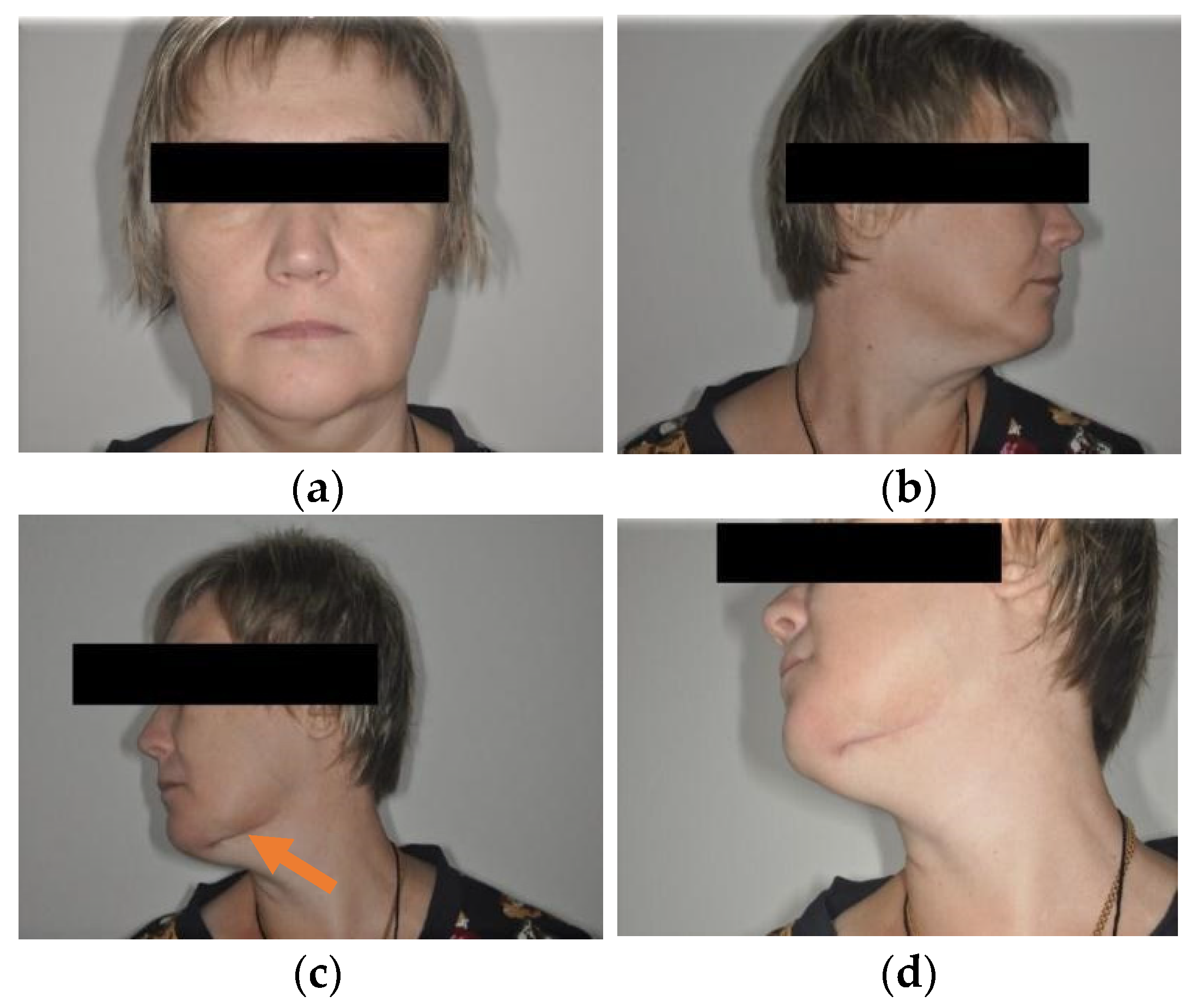

In total, 82 patients were interviewed of which 39 (47.6%) patients were in the control group and the main group included 43 patients who (52.4%) underwent radical surgical treatment (

Figure 1a–d). The mean age of the patients in both groups was 66.8 ± 10.03 years. As regards the localization of the primary site of cancer, patients with a history of malignant neoplasm (MN) of the prostate prevailed, followed by MN of the breast (

Table 1 and

Table 2).

Due to the presence of bone metastases, patients received intravenous bisphosphonates monthly (every 28 days) for an average of 3.5 ± 1 years.

The treatment of patients in the control group was carried out according to a conventional conservative scheme, which included the treatment of wounds in the oral cavity with 0.05% chlorhexidine solution one to two times a day, antibacterial therapy (clindamycin—150 mg, four times a day), and analgesic therapy (nimesulide).

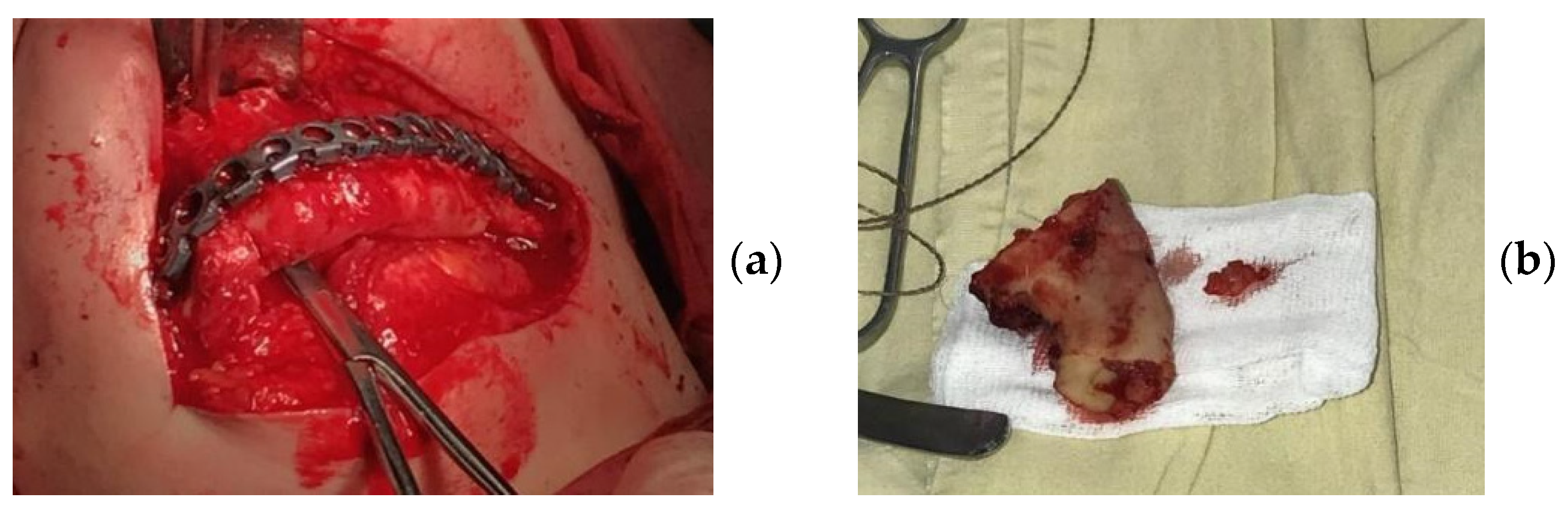

The patients in the main group (43 subjects) underwent segmental resection of the jaw after preoperative preparation (

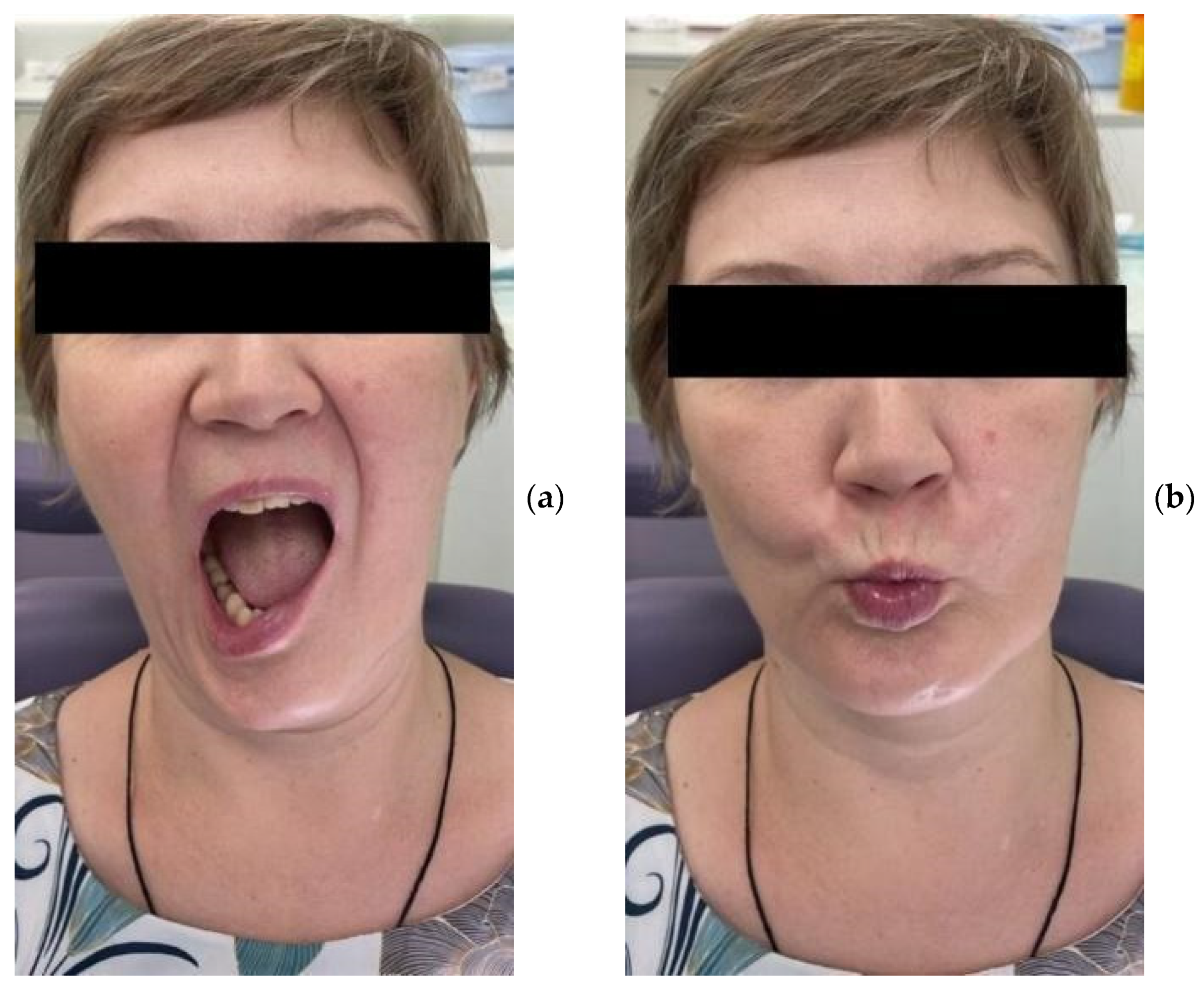

Figure 2 and

Figure 3a,b).

After 30 days, and then six months after the treatment, patients were asked to assess the intensity of pain using a numerical scale (where 0 = no pain, 5 = moderate pain, and 10 = the most severe pain imaginable) and to fill in the SF-36 Quality of Life Questionnaire.

The Numerical Pain Rating Scale is a numerical analogue of the Visual Analog Scale for Pain method for the assessment of pain intensity based on a point system.

The SF-36 Health Survey measures the physical, emotional, and social components of quality of life. It contains 36 items that are grouped into eight domains: Physical Functioning (PF), Role—Physical Functioning (RP), Bodily Pain (BoP), General Health (GH), Vitality (VT), Social Functioning (SF), Role—Emotional (RE), and Mental Health (MH). The scores on each scale range between 0 and 100, with 100 representing total health. The results are presented in the form of scores on eight scales, designed in such a way that a higher score indicates a higher level of quality of life. All scales yield two summary measures related to the mental and physical components of health, which are calculated based on the number of points:

0–20% = low quality of life;

21–40% = reduced quality of life;

41–60% = moderate quality of life;

61–80% = increased quality of life;

81–100% = high quality of life.

For statistical processing of the data, we used the SPSS Statistics software package version 17.0 (Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) [

13].

3. Results

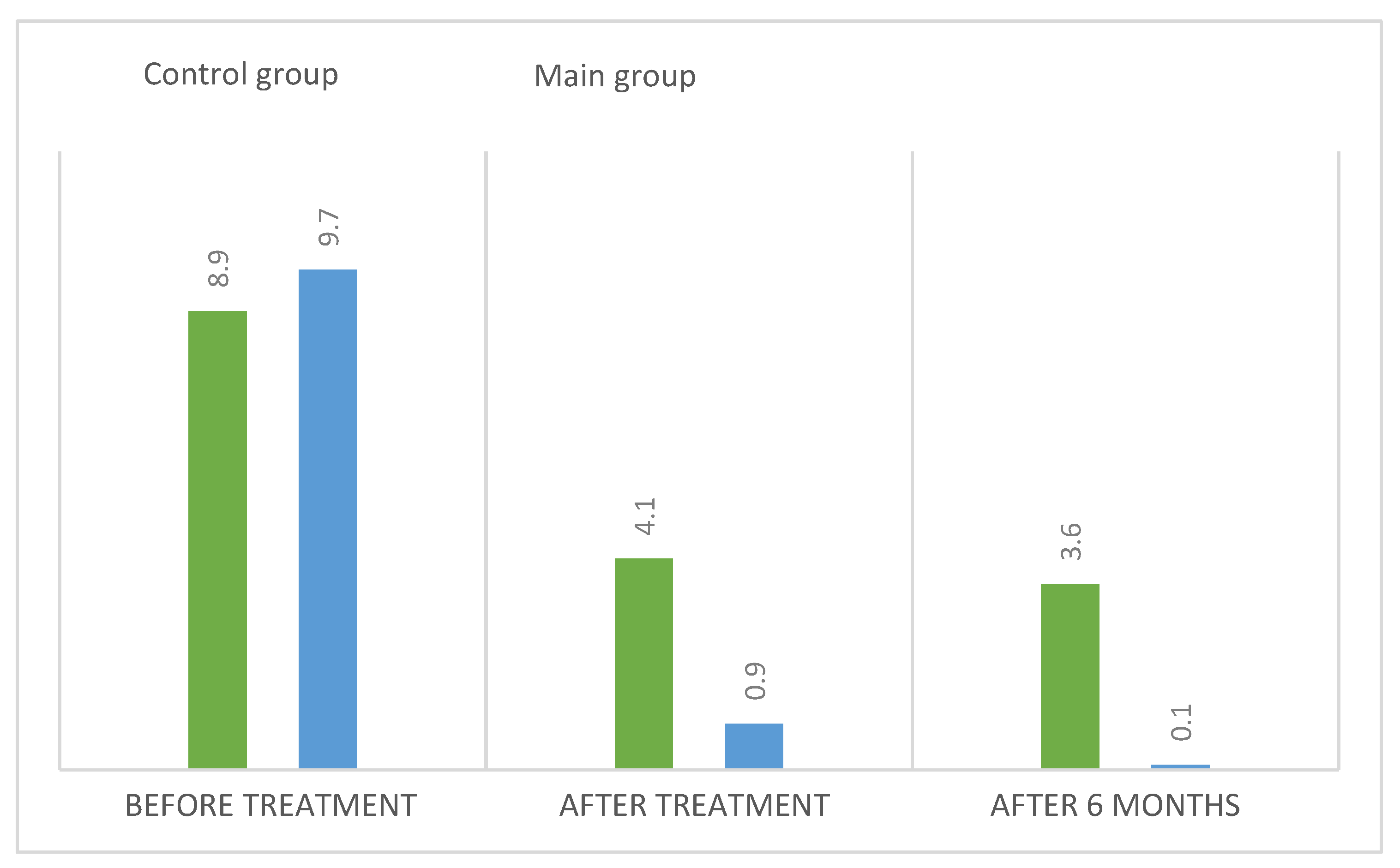

An analysis of the results obtained from the Numeric Pain Rating Scale demonstrated that the mean pain intensity before treatment was 8.9 points in the control group, and 9.7 in the main group (

Figure 4). These values are indicative of “unbearable pain.” After treatment (30 days), the pain score in the control group decreased and amounted to 4.1; this is evidence of the persistence of “moderate pain” in the patients. In patients who underwent segmental jaw resection (

Figure 5a,b and

Figure 6), the mean pain intensity was 0.5. There was no relationship with gender, but there was a direct relationship between the intensity of the pain and the stage of the process (CI = 95%).

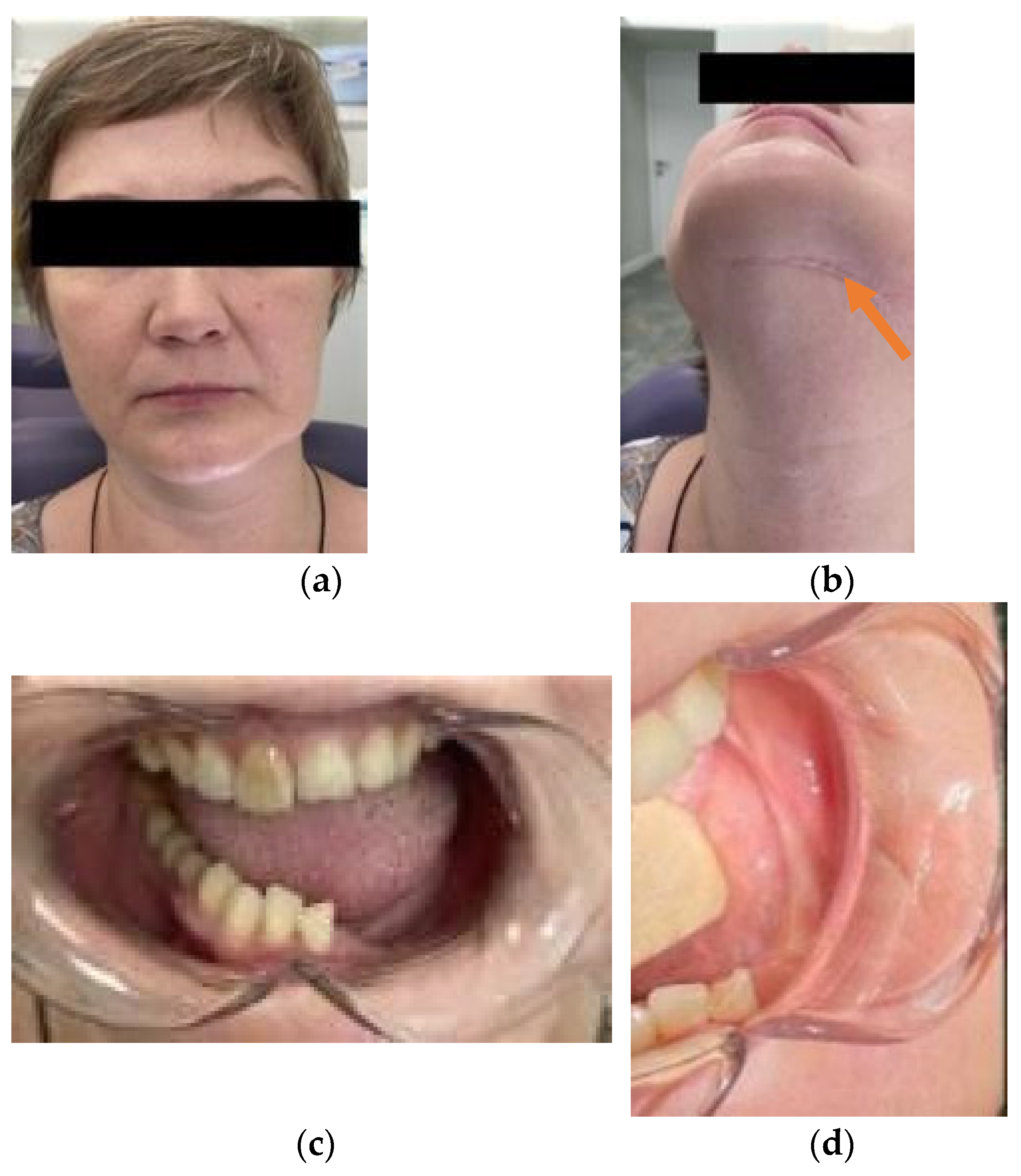

Table 3 presents the results obtained with the Visual Analog Scale in patients with MRONJ after six months, which make it possible to assess changes in this parameter over time. After treatment, this parameter value was 3.6 in the control group and 0.1 in the main group (

Figure 7a–d).

In the patients in the main and control groups, the pain intensity index values before treatment approached similar values. After surgery, the pain intensity index in the main group was close to normal values. In the control group, 30 days after conservative treatment, there was a tendency for the parameter to decrease; however, after six months, it did not reach the “no pain” mark (

Figure 8 and

Figure 9a,b).

In the patients in the main group after six months, the pain intensity score was 36 times lower than that of patients in the control group. Clinically, 10 patients in the control group had a relapse of the disease, which indicates the need for surgical intervention.

There was no relationship between pain and gender, but there was a direct relationship between the intensity of the pain and the stage of the process.

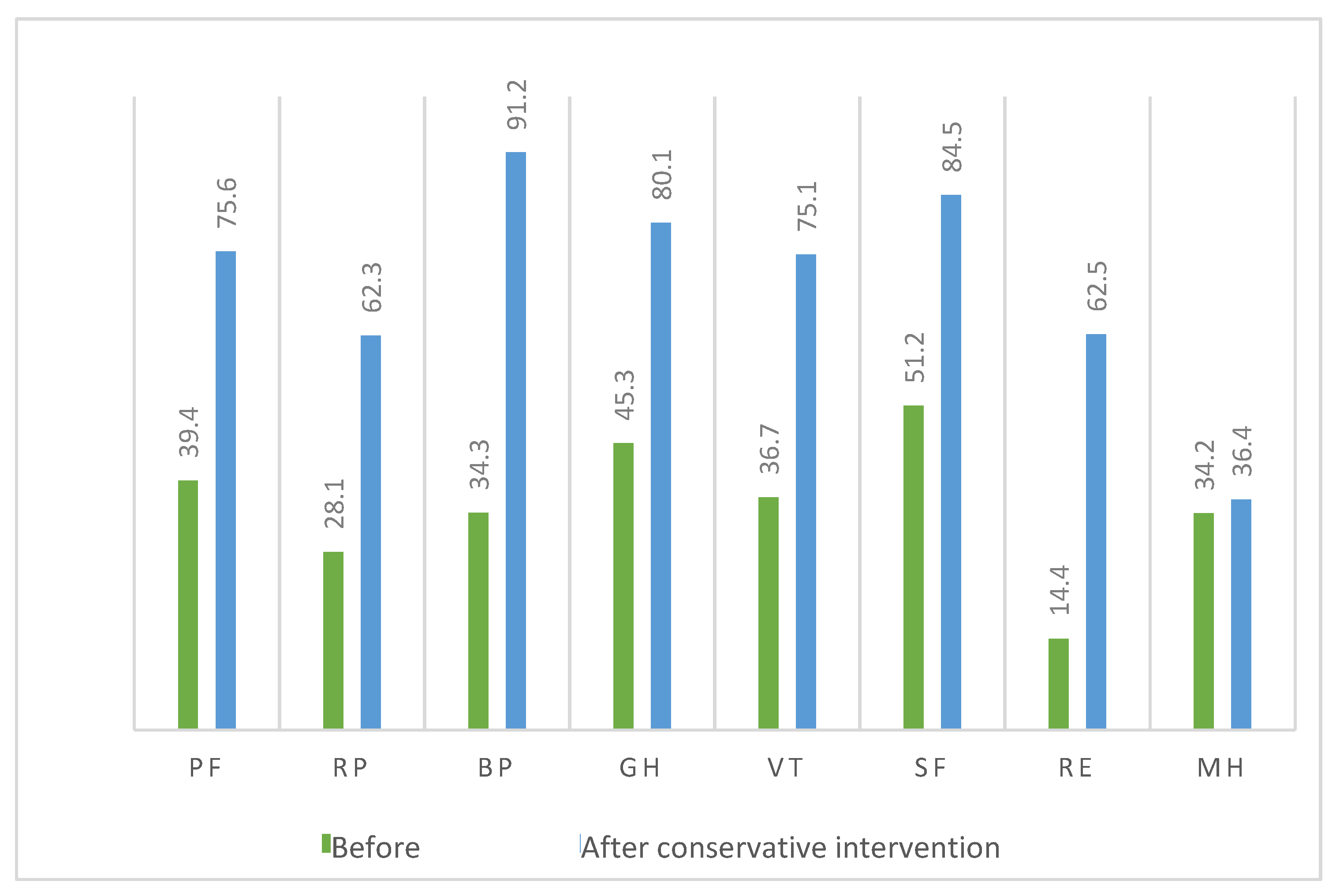

The SF-36 Quality of Life Questionnaire showed that in the control group who were treated conservatively, bodily pain before therapy had a score of 91.2 (CI = 95%) (

Figure 10). After a combination of antibacterial and anti-inflammatory therapy, this score decreased to 34.3. The mental health score of the patients with bisphosphonate osteonecrosis was 34.2 before treatment and 36.3 after treatment. The difference was 2.1 points, which indicates the persistence of discomfort. The remaining parameters improved after treatment, but no complete recovery was achieved.

Before conservative treatment, this group of patients had a reduced quality of life, and after conservative intervention, they achieved a score of 53.2%, which corresponds to a “moderate” quality of life (

Figure 11). This suggests the existence of a positive trend. In regard to the mental component after conservative treatment, the quality of life increased (69.1).

Before radical surgery, the main group of patients also had a high level of bodily pain (95.2), but after surgery this decreased to 12.4. The remaining parameters also showed a significant difference before and after radical surgery, indicating a positive trend (

Figure 12).

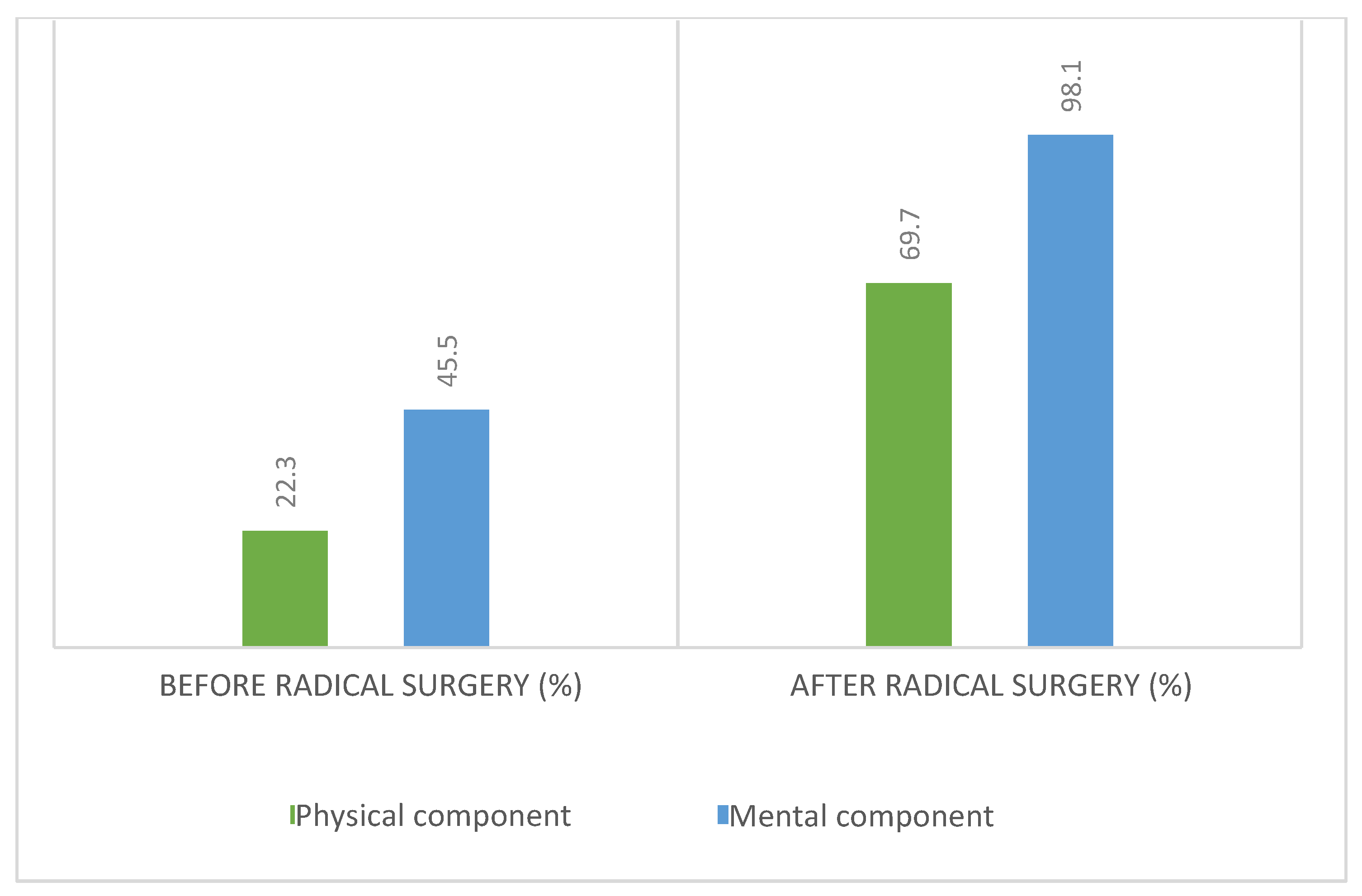

The physical component scores in the patients of the main group before and after surgical treatment were 22.3% and 69.7%, respectively, indicating an increased quality of life after segmental resection (

Figure 13).

4. Discussion

The systematic review by Ottesen et al., 2020, showed that most of the clinical cases of MRONJ described in the literature occurred after tooth extraction, that is, in about 50–70% of cases [

14,

15,

16]. However, the infectious process leading to the extraction of teeth is primary, just like the infection that develops around the implants. It should be noted that tooth extraction is not required for the manifestation of MRONJ; however, it has been suggested that tooth extraction may be a trigger. Chronic infections that lead to tooth extraction can be a factor in the development of MRONJ. Discontinuation of antiresorptive therapy (drug holiday) is an issue that requires careful discussion because bisphosphonates persist in the bone for a long time, while there are clear indications for tooth extraction. The study showed that the best results with complete healing of the mucous membrane and minimal damage to the bone were achieved only with a combination of antibiotic prophylaxis, smoothening of the sharp edges of bones, thorough wound closure, and drug holidays (6 weeks before surgery and 8 weeks after surgery). It should be noted that all preventive measures are regarded as well-proven clinical methods to avoid local infections after tooth extraction [

17,

18].

Additionally, one of the challenges for surgeons who deal with medication-related osteonecrosis is the difficulty of defining the correct margins for bone resection [

19,

20]. The autofluorescence method is well known, but as different studies show, it does not appear to be superior to conventional surgical techniques. In our ongoing work, we use CT for planning and intraoperative confirmation of the margins of the resection, while verifying the results by histopathology.

The issue of preventing the onset and further spread of osteonecrosis in unaffected areas remains relevant. In addition to a traumatic tooth removal and a drug holiday, there is the question of the use of autologous platelet concentrates (APC) for the prevention and treatment of MRONJ [

21,

22,

23]. A review of the literature in the PubMed, Scopus and Web of Science databases using search queries related to “platelet concentrate” and “osteonecrosis” showed that there were no significant differences in terms of prognosis for the disease. The results obtained are insufficient to establish the effectiveness of APC in the prevention and treatment of MRONJ. We did not use APC in our study.

The results obtained with the Numeric Pain Rating Scale demonstrated that the scores for both groups approached “unbearable pain.” After treatment (conservative treatment in the control group and surgical treatment in the main group), the pain decreased to “moderate pain” in the control group and “no pain” in the main group, which is evidence of positive changes [

24,

25,

26]. There was no relationship between pain and gender.

Signs of anxiety were observed in all patients undergoing treatment with a diagnosis of “medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw.” The frequency of anxiety in women was no different to that in men. A direct relationship was found between the duration of the disease, the intensity of the pain, and the level of anxiety. A correlation between the level of physical functioning and the level of bodily pain was also identified. Mental health scores were half of the maximum possible score [

27,

28,

29,

30].

5. Conclusions

The study of the quality of life during the progression of oncological processes and the sequalae of antiresorptive therapy in the body plays an important role in clinical practice. The methodology for studying the quality of life makes it possible to accurately describe a complex system of multifaceted and diverse disorders that occur in cancer patients during the progression of the disease and its treatment.

Radical surgery allows us to improve the quality of life of patients, thereby confirming that surgical volume is a secondary aspect if there is no relapse after the treatment.

Author Contributions

The concept and methodology were proposed and carried out by K.A.P. The ideas, the formulation of the goals and objectives of the study, and the development of the methodology are also attributed to him. Formal analysis, research, and obtaining of resources, the use of statistical methods for the analysis of this study, the conduct of the study, and the collection of patient data were carried out by S.V.P., L.S.S. was involved in data curation and writing and preparing the original draft, as well as reviewing and editing, as was T.P.I. Visualization, field supervision, and project administration were carried out by P.S.P., S.Y.I. was responsible for the management and coordination of research planning and execution. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of I.M. Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University, protocol code 03-12, date of approval 28 November 2012.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent was obtained from the patients to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to unwillingness of the majority of subjects in Informed Consent.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to express their appreciation to the rector of the I.M. Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University (Sechenov University), Petr Vitalievich Glybochko.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Voss, P.J.; Steybe, D.; Poxleitner, P.; Schmelzeisen, R.; Munzenmayer, C.; Fuellgraf, H.; Stricker, A.; Semper-Hogg, W. Osteonecrosis of the jaw in patients transitioning from bisphosphonates to denosumab treatment for osteoporosis. Odontology 2018, 106, 469–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.Y.; Qin, J.; Huang, J.; Wang, F.; Xu, G.P.; Lv, Y.T.; Zhang, J.B.; Shen, L.M. Zoledronic acid inhibits infiltration of tumor-associated macrophages and angiogenesis following transcatheter arterial chemoembolization in rat hepatocellular carcinoma models. Oncol. Lett. 2017, 14, 4078–4084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Silveira, F.M.; Etges, A.; Correa, M.B.; Vasconcelos, A.C.U. Microscopic evaluation of the effect of oral microbiota on the development of bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the Jaws in Rats. J. Oral Maxillofac. Res. 2016, 7, 2–3. [Google Scholar]

- Curra, C.; Cardoso, C.L.; Ferreira, O.; Curi, M.M.; Matsumoto, M.A.; Cavenago, B.C.; Santos, P.L.D.; Santiago, J.F. Medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw. Introduction of a new modified experimental model1. Acta Cir. Bras. 2016, 31, 308–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oteri, G.; Trifirò, G.; Peditto, M.; Presti, L.L.; Marcianò, I.; Giorgianni, F.; Sultana, J.; Marcianò, A. Treatment of medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw and its impact on a patient’s quality of life: A single-center, 10-year experience from southern Italy. Drug Saf. 2018, 41, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, X.; Wang, Z.; Wu, K.; Wang, Y.; Shan, L. Zoledronate inhibits the differentiation potential of adipose-derived stem cells into osteoblasts in repairing jaw necrosis. Mol. Cell. Probes 2020, 51, 101525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilyas, Z.; Camacho, P.M. Rare adverse effects of bisphosphonate therapy. Curr. Opin. Endocrinol. Diabetes Obes. 2019, 26, 335–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuroshima, S.; Sasaki, M.; Sawase, T. Medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: A literature review. J. Oral Biosci. 2019, 61, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGowan, K. Insufficient evidence to compare the efficacy of treatments for medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaws. J. Evid. Based Dent. Pract. 2018, 18, 70–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, K.G.V.; Garza, N.E.; Silva, J.Y.G.; Ruiz, R.R.; Romero, A.D.S.; Cepeda, M.A.A.N.; Solis-Soto, J.M. Osteonecrosis of the jaw: An update. Int. J. Appl. Dent. Sci. 2021, 7, 173–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolatou-Galitis, O.; Schiødt, M.; Mendes, R.A.; Ripamonti, C.; Hope, S.; Drudge-Coates, L.; Niepel, D.; Van den Wyngaert, T. Medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: Definition and best practice for prevention, diagnosis, and treatment. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2019, 127, 117–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kawahara, M.; Kuroshima, S.; Sawase, T. Clinical considerations for medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: A comprehensive literature review. Int. J. Implant Dent. 2021, 7, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, M.H.A.; Puteh, F. Quantitative data analysis: Choosing between SPSS, PLS, and AMOS in social science research. Int. Interdiscip. J. Sci. Res. 2017, 3, 14–25. [Google Scholar]

- Van Poznak, C.H.; Unger, J.M.; Darke, A.K.; Moinpour, C.; Bagramian, R.A.; Schubert, M.M.; Hansen, L.K.; Floyd, J.D.; Dakhil, S.R.; Lew, D.L. Association of osteonecrosis of the jaw with zoledronic acid treatment for bone metastases in patients with cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2021, 7, 246–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggiero, S.L.; Dodson, T.B. American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons position paper on medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaws-2014 update. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2014, 72, 2381–2383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlRahabi, M.K.; Ghabbani, H.M. Clinical impact of bisphosphonates in root canal therapy. Saudi Med. J. 2018, 39, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey, E.; Genta, R.; Noemi, P.S. MRONJ: Stage 3, the Best Moment to Develop Surgery Techniques. J. Oral Med. Dent. Res. 2020, 1, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Lorusso, L.; Pieruzzi, L.; Gabriele, M.; Nisi, M.; Viola, D.; Molinaro, E.; Bottici, V.; Elisei, R.; Agate, L. Osteonecrosis of the jaw: A rare but possible side effect in thyroid cancer patients treated with tyrosine-kinase inhibitors and bisphosphonates. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2021, 44, 2557–2566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zebic, L.; Patel, V. Preventing medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw. Bmj 2019, 365, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mânea, H.C.; Urechescu, H.C.; Balica, N.C.; Pricop, M.O.; Baderca, F.; Poenaru, M.; Horhat, I.D.; Jifcu, E.M.; Cloşca, R.M.; Sarău, C.A. Bisphosphonates-induced osteonecrosis of the jaw-epidemiological, clinical and histopathological aspects. Rom. J. Morphol. Embryol. 2018, 59, 825–831. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, S.H.; Park, S.J.; Kim, M.K. The effect of bisphosphonate discontinuation on the incidence of postoperative medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw after tooth extraction. J. Korean Assoc. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2020, 46, 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- AlDhalaan, N.A.; BaQais, A.; Al-Omar, A. Medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: A review. Cureus 2020, 12, 3–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fausto, S.; Di Carlo Marco, C.M.; Sonia, F.; Alessandro, C.; Marwin, G. The impact of different rheumatic diseases on health-related quality of life: A comparison with a selected sample of healthy individuals using SF-36 questionnaire, EQ-5D and SF-6D utility values. Acta Bio Med. Atenei Parm. 2018, 89, 541. [Google Scholar]

- Bagan, L.; Jiménez, Y.; Leopoldo, M.; Murillo-Cortes, J.; Bagan, J. Exposed necrotic bone in 183 patients with bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: Associated clinical characteristics. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Y Cir. Buccal 2017, 22, e582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, N.A.; Chatelain, S.; Alfonsi, F.; Mortellaro, C.; Barone, A. Medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: The use of leukocyte-platelet-rich fibrin as an adjunct in the treatment. J. Craniofacial Surg. 2019, 30, 1095–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, V.; Mansi, J.; Ghosh, S.; Kwok, J.; Burke, M.; Reilly, D.; Nizarali, N.; Sproat, C.; Chia, K. MRONJ risk of adjuvant bisphosphonates in early-stage breast cancer. Br. Dent. J. 2018, 224, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolette, A.; Lecloux, G.; Rompen, E.; Albert, A.; Kerckhofs, G.; Lambert, F. Influence of induced infection in medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw development after tooth extraction: A study in rats. J. Cranio-Maxillofac. Surg. 2019, 47, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basin, E.; Medvedev, Y.; Polyakov, K. Medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw. Vrach 2015, 3, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Holtmann, H.; Lommen, J.; Kübler, N.R.; Sproll, C.; Rana, M.; Karschuck, P.; Depprich, R. Pathogenesis of medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: A comparative study of in vivo and in vitro trials. J. Int. Med. Res. 2018, 46, 4277–4296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Di Fede, O.; Canepa, F.; Panzarella, V.; Mauceri, R.; Del Gaizo, C.; Bedogni, A.; Fusco, V.; Tozzo, P.; Pizzo, G.; Campisi, G. The Treatment of Medication-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaw (MRONJ): A Systematic Review with a Pooled Analysis of Only Surgery versus Combined Protocols. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).