3D Printing of Objects with Continuous Spatial Paths by a Multi-Axis Robotic FFF Platform

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Related Work

2.1. Multi-DOF 3D Printing

2.2. Toolpath Planning

3. Methodology

3.1. Overview

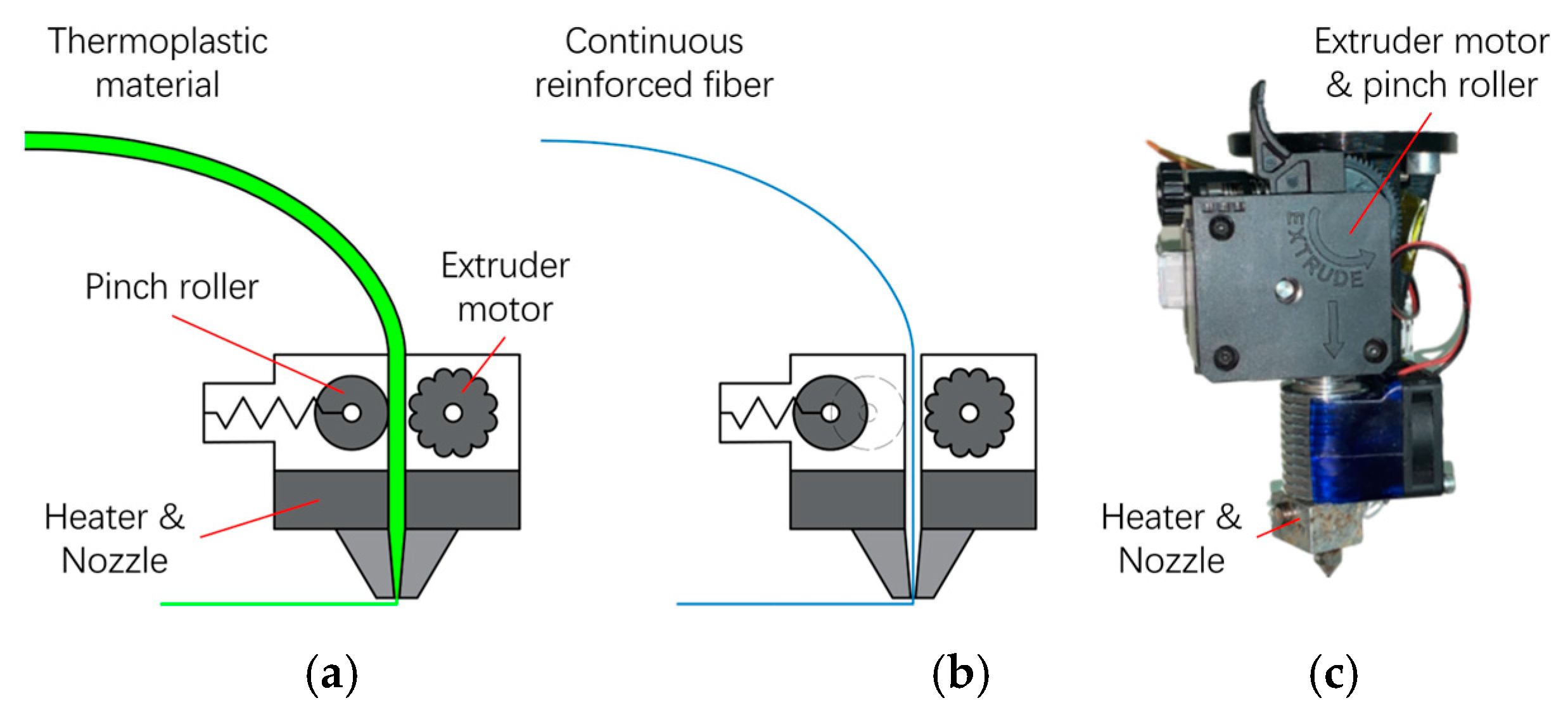

3.1.1. Hardware Platform

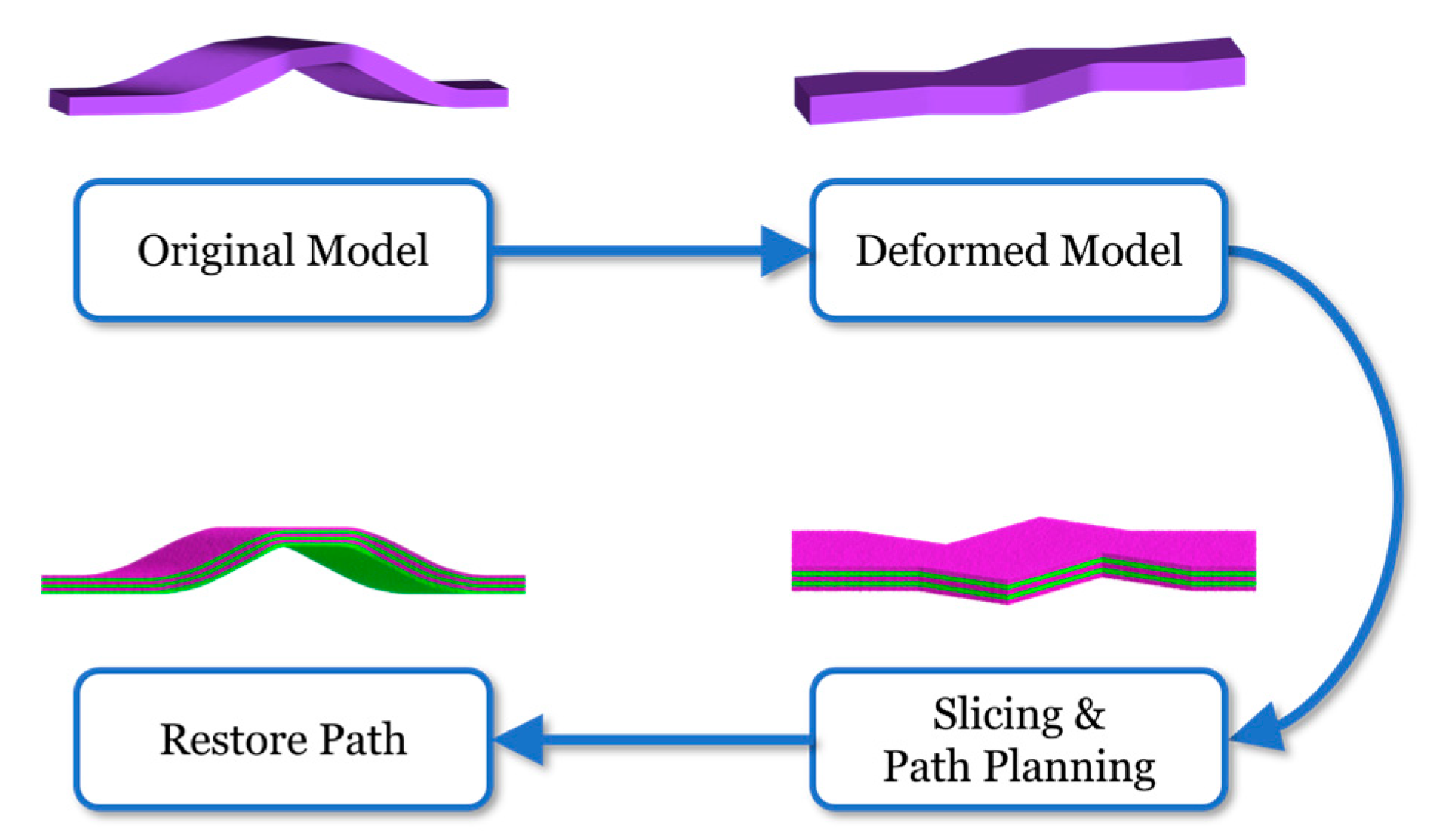

3.1.2. Multi-Axis Printing Toolpath Planning

3.1.3. Process Controlling

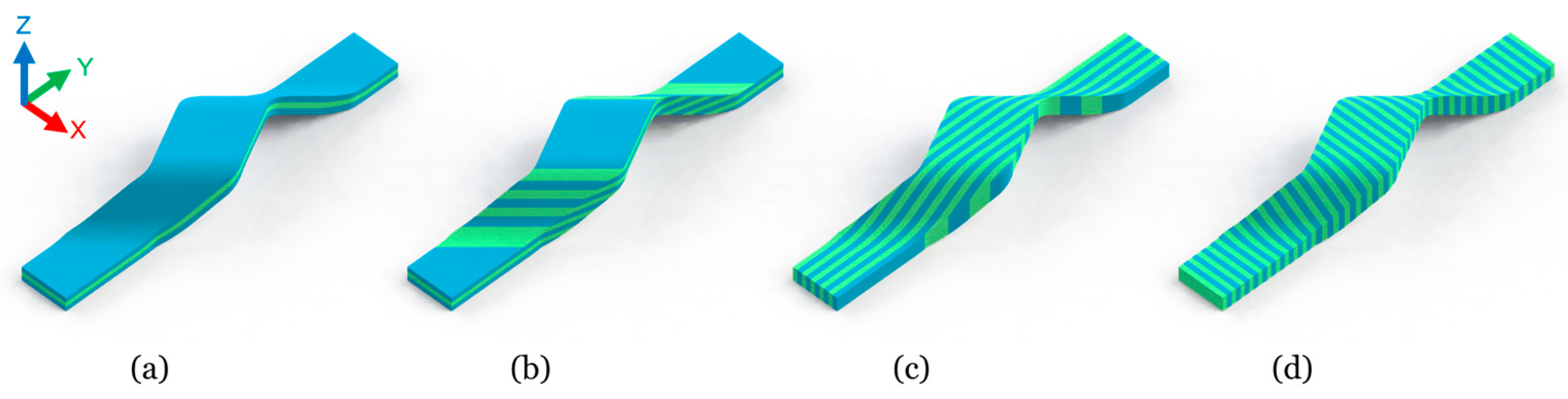

3.2. Multi-Axis Toolpath Planning

3.2.1. Curve Slicing

3.2.2. Global Continuous Toolpath Planning

| Algorithm 1 Spatial printing sequence generation |

| 1: Spatial Printing Sequence (D) |

| 2: R ← ∅ |

| 3: rk,i ← D.Get End () |

| 4: while D is not empty do |

| 5: R.Append (rk,i) |

| 6: D.Remove Item (rk,i) |

| 7: if Not Interfere (rk,i) then |

| 8: rk,i ← D.Find Upper Region (rk+1,i) |

| 9: if rj,k = ∅ then |

| 10: rj,k ← D.Get End () |

| 11: end if |

| 12: else |

| 13: rk,i ← D.Get End () |

| 14: end if |

| 15: end while |

| 16: return r |

3.2.3. Printing with Support

3.3. Process Controlling Algorithm

3.3.1. Material Extrusion Synchronization

3.3.2. End Effector Pose Controlling

- (1)

- For each point in the path, connect the next point to form a line segment .

- (2)

- Create a vertical plane perpendicular to the hotbed and through the , using the as a constraint.

- (3)

- The nozzle’s orient at should be parallel to and point to the negative direction of the z-axis.

- (4)

- also needs to be perpendicular to the .

- (5)

- Boundary condition: If the angle between and the z-axis exceeds the safe range, will be limited within the range.

- (6)

- Use cubic splines to smooth the to ensure stable printing.

- (7)

- Append the to corresponding and the integrated print toolpath is .

4. Experiments and Discussion

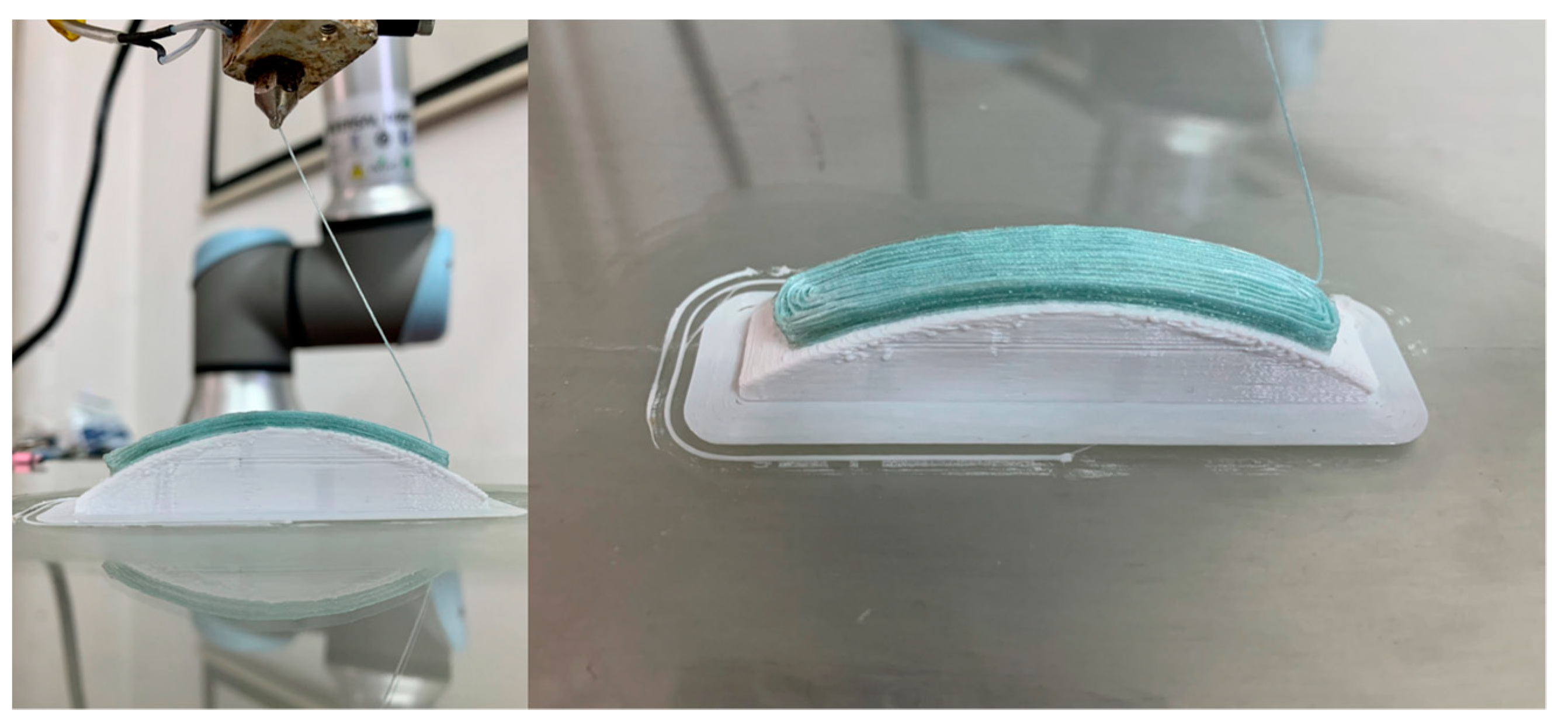

4.1. Model Printing

4.2. Mechanical Test

4.3. Result and Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ngo, T.D.; Kashani, A.; Imbalzano, G.; Nguyen, K.T.Q.; Hui, D. Additive manufacturing (3D printing): A review of materials, methods, applications and challenges. Compos. Part B Eng. 2018, 143, 172–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.D.; Oh, Y.T. A benchmark study on rapid prototyping processes and machines: Quantitative comparisons of mechanical properties, accuracy, roughness, speed, and material cost. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part B J. Eng. Manuf. 2008, 222, 201–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urhal, P.; Weightman, A.; Diver, C.; Bartolo, P. Robot assisted additive manufacturing: A review. Robot. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2019, 59, 335–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chenming, W.; Chengkai, D.; Changling, W.; Yongjin, L. Recent Progress on Multi-DOFs 3D Printing: A Survey. Chin. J. Comput. 2019, 9, 1918–1938. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, W.C.; Wei, C.C.; Chung, S.C. Development of a hybrid rapid prototyping system using low-cost fused deposition modeling and five-axis machining. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2014, 214, 2366–2374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Yu, M.; Gao, Y.; Yan, D.M. Multi-DOF 3D Printing with Visual Surveillance. In Proceedings of the SIGGRAPH Asia 2017, Bangkok, Thailand, 27–30 November 2017; pp. 3–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keating, S.; Oxman, N. Compound fabrication: A multi-functional robotic platform for digital design and fabrication. Robot. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2013, 29, 439–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, P.F.; Meng, H.; Yu, L.; Zhang, L. Robotic Fabrication in Architecture, Art and Design 2016. Robot. Multi-Dimens. Print. Based Struct. Perform. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ding, Y.; Dwivedi, R.; Kovacevic, R. Process planning for 8-axis robotized laser-based direct metal deposition system: A case on building revolved part. Robot. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2017, 44, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, C.; Wang, C.C.L.; Wu, C.; Lefebvre, S.; Fang, G.; Liu, Y.J. Support-free volume printing by multi-axis motion. ACM Trans. Graph. 2018, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- de Backer, W.; van Tooren, M.J.L.; Bergs, A.P. Multi-axis multi-material fused filament fabrication with continuous fiber reinforcement. In Proceedings of the 2018 AIAA/ASCE/AHS/ASC Structures, Structural Dynamics and Materials Conference, Kissimmee, FL, USA, 8–12 January 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mueller, S.; Im, S.; Gurevich, S.; Teibrich, A.; Guimbretière, F.; Baudisch, P. WirePrint: Fast 3D Printed Previews. In Proceedings of the 27th Annual ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology, Honolulu, HI, USA, 5–8 October 2014; pp. 273–280. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, R.; Peng, H.; Guimbretière, F.; Marschner, S. Printing arbitrary meshes with a 5DOF wireframe printer. ACM Trans. Graph. 2016, 35, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Hu, X.; Song, G.; Liu, Z.; Yu, L.; Liu, L. FrameFab: Robotic Fabrication of Frame Shapes. ACM Trans. Graph. 2016, 35, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dörfler, K.; Hack, N.; Sandy, T.; Giftthaler, M.; Lussi, M.; Walzer, A.N.; Buchli, J.; Gramazio, F.; Kohler, M. Mobile robotic fabrication beyond factory conditions: Case study Mesh Mould wall of the DFAB HOUSE. Constr. Robot. 2019, 3, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chakraborty, D.; Aneesh Reddy, B.; Roy Choudhury, A. Extruder path generation for Curved Layer Fused Deposition Modeling. CAD Comput. Aided Des. 2008, 40, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yerazunis, W.S.; Barnwell, J.C., III; Nikovski, D.N. Strengthening ABS, nylon, and polyester 3D printed parts by stress tensor aligned deposition paths and five-axis printing. In Proceedings of the Solid Freeform Fabrication Symposium, Austin, TX, USA, 8–10 August 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Singamneni, S.; Roychoudhury, A.; Diegel, O.; Huang, B. Modeling and evaluation of curved layer fused deposition. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2012, 212, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahlers, D.; Wasserfall, F.; Hendrich, N.; Zhang, J. 3D printing of nonplanar layers for smooth surface generation. IEEE Int. Conf. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2019, 2019, 1737–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.C.; Ray, N.; Sokolov, D.; Lefebvre, S. Anti-aliasing for fused filament deposition. CAD Comput. Aided Des. 2017, 89, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ezair, B.; Fuhrmann, S.; Elber, G. Volumetric covering print-paths for additive manufacturing of 3D models. CAD Comput. Aided Des. 2018, 100, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etienne, J.; Ray, N.; Panozzo, D.; Hornus, S.; Wang, C.C.L.; Martínez, J.; McMains, S.; Alexa, M.; Wyvill, B.; Lefebvre, S. Curvislicer: Slightly curved slicing for 3-axis printers. ACM Trans. Graph. 2019, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Steuben, J.C.; Iliopoulos, A.P.; Michopoulos, J.G. Implicit slicing for functionally tailored additive manufacturing. CAD Comput. Aided Des. 2016, 77, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, G.; Zhang, T.; Zhong, S.; Chen, X.; Zhong, Z.; Wang, C.C.L. Reinforced FDM: Multi-axis filament alignment with controlled anisotropic strength. ACM Trans. Graph. 2020, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Gao, X.; Jacobson, A.; Zorin, D.; Panozzo, D. Tetrahedral meshing in the wild. ACM Trans. Graph. 2018, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMains, S.; Smith, J.; Wang, J.; Séquin, C. Layered Manufacturing of Thin-Walled Parts. In Proceedings of the International Design Engineering Technical Conferences and Computers and Information in Engineering Conference. American Society of Mechanical Engineers, Baltimore, MD, USA, 10–13 September 2000; pp. 379–387. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths, J.G. Toolpath based on Hilbert’s curve. Comput. Des. 1994, 26, 839–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Yao, Y.; Jiang, Y. A 3D Continuous Path Generation Method and Evaluation for Fused Deposition Manufacturing in Tissue Engineering. J. Biomater. Tissue Eng. 2019, 9, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Gu, F.; Huang, Q.-X.; Garcia, J.; Chen, Y.; Tu, C.; Benes, B.; Zhang, H.; Cohen-Or, D.; Chen, B. Connected Fermat Spirals for Layered Fabrication. ACM Trans. Graph. 2016, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Li, M.; Lackner, M.; Herfried, L. A continuous fiber-reinforced additive manufacturing processing based on PET fiber and PLA. Materials 2020, 13, 3044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Slice Type | Max Load (N) | Max Deformation (mm) |

|---|---|---|

| Curve slicing | 750.47 | 4.934 |

| Z-direction | 420.66 | 3.905 |

| X-direction | 614.61 | 4.594 |

| Y-direction | 280.89 | 2.552 |

| Slice Type | Max Load (N) | Max Deflection (mm) |

|---|---|---|

| Curve slicing | 135.70 | 5.825 |

| Z-direction | 119.70 | 6.103 |

| X-direction | 140.66 | 7.172 |

| Y-direction | 102.27 | 5.215 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Aburaia, M.; Lackner, M. 3D Printing of Objects with Continuous Spatial Paths by a Multi-Axis Robotic FFF Platform. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 4825. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11114825

Yao Y, Zhang Y, Aburaia M, Lackner M. 3D Printing of Objects with Continuous Spatial Paths by a Multi-Axis Robotic FFF Platform. Applied Sciences. 2021; 11(11):4825. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11114825

Chicago/Turabian StyleYao, Yuan, Yichi Zhang, Mohamed Aburaia, and Maximilian Lackner. 2021. "3D Printing of Objects with Continuous Spatial Paths by a Multi-Axis Robotic FFF Platform" Applied Sciences 11, no. 11: 4825. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11114825

APA StyleYao, Y., Zhang, Y., Aburaia, M., & Lackner, M. (2021). 3D Printing of Objects with Continuous Spatial Paths by a Multi-Axis Robotic FFF Platform. Applied Sciences, 11(11), 4825. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11114825