Abstract

The design of a virtual reality (VR) cultural application is aimed at supporting the steps of the learning process-like concrete experimentation, reflection and abstraction—which are generally difficult to induce when looking at ruins and artifacts that bring back to the past. With the use of virtual technologies (e.g., holographic surfaces, head-mounted displays, motion—cation sensors) those steps are surely supported thanks to the immersiveness and natural interaction granted by such devices. VR can indeed help to symbolically recreate the context of life of cultural objects, presenting them in their original place of belonging, while they were used for example, increasing awareness and understanding of history. The ArkaeVision VR application takes advantages of storytelling and user experience design to tell the story of artifacts and sites of an important cultural heritage site of Italy, Paestum, creating a dramaturgy around them and relying upon historical and artistic content revised by experts. Visitors will virtually travel into the temple dedicated to Hera II of Paestum, in the first half of the fifth century BC, wearing an immersive viewer–HTC Vive; here, they will interact with the priestess Ariadne, a digital actor, who will guide them on a virtual tour presenting the beliefs, the values and habits of an ancient population of the Magna Graecia city. In the immersive VR application, the memory is indeed influenced by the visitors’ ability to proceed with the exploratory activity. Two evaluation sessions were planned and conducted to understand the effectiveness of the immersive experience, usability of the virtual device and the learnability of the digital storytelling. Results revealed that certainly the realism of the virtual reconstructions, the atmosphere and the “sense of the past” that pervades the whole VR cultural experience, characterize the positive feedback of visitors, their emotional engagement and their interest to proceed with the exploration.

1. Introduction. User Experience Research in cultural heritage

Working on cultural heritage (CH) through virtual technologies allows us to establish a more intimate and profound “dialog” with visitors, given the potentialities of such devices to virtually recreate ancient scenarios of life, where artifacts, landscapes, environments and characters (re)live together in a coherent combination. Visitors, always more, look for interactivity and immersiveness during their cultural experience [1,2,3]; they want to get in contact with the past, with all their senses, by direct experiencing places and objects through everyday gestures and behaviors (natural interaction) as well as by feeling that they are embodied in the augmented reality mainly through the sight (sense of immersion). Multi-projection systems, holographic applications, immersive viewers, Augmented reality (AR) systems support the virtual immersion into reconstructed scenarios of the past at different levels [4]:

- -

- See-through and monitor-based AR displays provide users the illusion of admiring no more visible elements of the past, for example columns or colors, directly on the archaeological remains through the juxtaposition of the virtual model on the visible item by means of a device (tablet or a semi-transparent display). In case of holograms, the virtual contents are displayed thanks to an illusory technique better known as Pepper’s Ghost which uses a game of reflections to project virtual elements (images or videos) from a display on a transparent glass, Plexiglas or other plastic film to give the illusion that these elements appear inside environments and interact with objects or physical persons. In addition, the HoloLens technology is based on this approach: this wearable device indeed offers stereoscopic fruition while maintaining an overview on the real word. In case of AR displays using tablets, the system works applying superimposition or juxtaposition of virtual images and real ones framed by the camera of the device [5].

- -

- Multi-projections allow the superimposition of virtual elements (lights, images or videos) directly on real surfaces and physical structures, through projections mapping techniques and letting them coincide. Users are here at the center of a visual show which, in some cases, gives them the impression of being surrounded by ancient elements like architectures of a Greek temple or a Basilica at 1:1 scale, as they would have appeared in origin; alternatively, users can participate to a digital storytelling taking place around them on a very big surfaces, generally supported by open-air soundscape.

- -

- Head-mounted displays (HMD) are the most powerful in terms of immersion into virtual worlds, thanks to a total visual occlusion of users while wearing such devices, as well as a complete sound isolation due to the incorporated earphones; virtual scenes happen in front of users’ eyes, but at a greater level of embodiment: they can see their bodies transposed into the 3D scene and they can directly interact with the digital elements as in real life–by touching, manipulating and moving them using hand devices, as well as walking.

Every technology has thus its own level of immersion into digitally replicated cultural environments, according to the used device–tablet, wearable tool or projections. Each one involves users on a different perceptive levels: AR and holograms have an impact on the sight on a limited field of view, ensuring the spatial contiguity’s principle; HMDs involve the sight a 360° and sometimes also hearing and body gestures (hands’ movement and walking), providing a full body experience; multi-projections work on “contextual” stimuli which users can grab with the sight and the hearing—also absorbing surrounding noises (crowd, noises of the city’s activities…) and physical obstacles (dimensions of the wall projection, any occlusion point, architectural inaccessibility…).

The cognitive process-attention, motor & action, visual–spatial perception, language and memory–is therefore relevant to understand how people experience CH through digital technologies–like the ones above mentioned. Perception is surely of our interest; it refers to a process of sensory stimulation and significance that our mind activates once in front of something. Visual perception and proprioception represent the prime cognitive faculties, since with our eyes and body that we know the world around us. In addition, in virtual reality (VR) this is still a prime way to explore and live the three-dimensional spaces. Sensations and perceptions are thus involved in the experience and in the learning processes, as it is presented in David Kolb’s experiential learning model (ELM) [6] and in Bloom’s taxonomy of cognition and social context [7,8,9].

Cognition and emotions are strictly related and depending one to another: the former is the mental process of knowledge acquisition and understanding by senses, thoughts and live experiences [10,11]; it generates attention, memorization and comprehension, generally processes that use existing knowledge to generate new knowledge. That is also what usually happens when we interact with a VR environment: the use of a device to access cultural information recalls the memory of something already familiar to the user (like quotidian gestures and movements). Social transmission and the cultural growth, therefore, take into account the reusability of our past experiences, the lessons learned and the emotions felt. In contrast, emotions work as indicators of the “quality” of such experiences and, together with reasoning, push us in a direction or another, making this or that choice.

Virtual technologies that enter museums and cultural places, can therefore increase both the concrete meanings of heritage, as well as the personal meanings emerged by the direct experience of users [12,13]. Exploiting thus the potential offered by the virtual can surely improve the communication of cultural heritage making the cultural offer more attractive to different user groups. Not only. The focus is improving the User eXperience (UX) of the cultural object or site they are living, so to transform that moment into an “augmented”, and even customizable story—a new piece of memory [4,14].

Indicators such as the usability of the virtual applications, the visibility of the elements that set up the graphic interfaces, the different user’s perception related to the ergonomics and handling of digital devices, as well as the level of emotional involvement with the story of such applications, the satisfaction generated by the use and the vision of virtual objects and environments, the levels of comprehensibility and memorization of the cultural contents, are just some of the records that are crucial for the design of new user experiences and for the success of any cultural communication project [15]. All these features have a deep impact on the (cultural) knowledge acquisition and retention; the latter can vary, on one hand, according to the absorptive mental faculty of individuals, their disseminative capacity and social perspectives; on the other hand, they can depend on the communicative models, channels and mechanisms employed as well as the languages and the storytelling techniques [16,17,18,19].

Several studies on museum visitors using virtual technologies, allowed indeed researchers to identify which aspects of the UX influence knowledge acquisition and retention and under which conditions [4,5,20,21]. What came out is that the users’ visit path inside cultural venues, the time spent using digital applications, the users’ behavior towards the museum items (active or passive visitors, in a group or alone) largely affect the content understanding and memorization. The same cultural information delivered through VR depends on the structure, the language and the style chosen by authors–even if it is not always easy to relate the content style to the chosen technology The above mentioned studies revealed also that a prevalent part of the visitors is usually very intrigued by virtual technologies, at the very beginning, and they want to try them quite immediately. However, once the surprise and discovery effects are ended, visitors’ attention tends to decline very quickly if any attractive, meaningful content is not presented. In order to maintain a high level of attention and motivation, working on content is thus essential: experimentation on narratives, representation and dramatization forms and new storytelling techniques are advisable in the cultural heritage field and they affect the choice of technology that can be done from time to time.

On a wider perspective, users’ digital fruition needs to be considered at 360 degrees when designing UX inside museums or archaeological sites. This is the challenge of this contribution: how to introduce elements of virtual spectacularization during the experience of a museum and the archaeological site? How to support the activation of curiosity, attention and interest in visitors to let the learning process to take place? How do we develop new forms of narration at the museum through emotions? How do we create a digital product capable of expanding the museum supply, enhancing its visibility and promoting interactive dynamics?

We present an immersive VR application, ArkaeVision Archeo, which stands as an experiential journey through time and space from the modern city of Paestum, located in the south of Italy, to its ancient Poseidonia back to the fifth century BC. We try to address the above-mentioned research questions considering the relevance of the design of UX in cultural contexts.

In the following sections we discuss how cultural experience can be addressed, shaped and evaluated in order to understand if VR technology can “substitute” the human cognition to let individuals feel, see and finally relive the past. We tackle the notions of emotion, memorization and learning referring to CH experience, explaining how these are connected and how emotions affect the way users feel and see the reality and the virtual world, and, consequently, the way they learn and foster the cultural information; (Section 1.1); we then focus the attention on how digital technologies influence such notions (Section 1.2) especially Immersive VR (Section 1.2) and its capability to make users feel embodied with the virtual world, emotionally and cognitively. The social and historical background of Paestum–Poseidonia will be shortly introduced in order to make clear the context we wanted to provide for the VR experience (Section 2.1); values, behaviors and social activities will be chosen ready to be transposed in the VR application (Section 2.2). The ArkaeVision experience and its design will be then presented (Section 3) as well as the centrality of users and their choices in such VR experience. In order to support and validate the work done by designers and computer scientists, as well as archaeologists and UX researchers, two evaluations during public events will reveal if ArkaeVision worked in terms of learnability and sense of involvement in the ancient Poseidonia, but also usability and general appreciation (Section 4 and Section 5). It will close the contribution a discussion section on the importance of the role of users’ emotions in approaching CH, the role of VR technology into museums and cultural venues and how the UX design can support and enhance future research projects (Section 5 and Section 6).

1.1. See, Feel, Remember the Past: Which Connection?

Users’ interaction with places, objects and other people generates stories, those that cultural objects are witnesses of in museums or archaeological sites. Nevertheless, most of the time these stories do not emerge in exhibit contexts; they are not made evident because artifacts and sites are reduced to simple labels or panels explaining very poor information like materials, age, provenance and dimensions. Such data are often for experts’ readability and do not reveal or explicit units of information useful for the general audience to understand how that object or site were in origin. Moreover, the fragmentation and the essentiality of most of museum objects or archaeological traces, make difficult to see the original shapes and the colors, for example, or the grandiosity of the architectures, their volumes and disposition. All these aspects do not emerge very often when visiting cultural venues. Hence, users’ readability of the past is influenced by the visibility–ascribable to the state of conservation of objects and sites.

Nevertheless, with the aid of virtual technologies, imagining the past can be supported. Technology makes “visible” images, concepts and meanings immediately on a device or directly on the real objects or sites [22,23]. The aesthetic features of a vase, for example, the provenance, the materials used to melt it and the ergonomics, tell a lot of that artifact and help users to mentally assign it to a time period, to a specific function or recognize its preciousness. But not exclusively. Information like the owners of that vase, what it contained, the conditions of its discovery, the context of use, and anecdotes coming from its “daily life” support the reestablishment of the object’s story and its social and cultural environment. This story is what intrigue visitors [24,25]; it involves them from an emotional point of view and allow them to almost feel the moment when the vase was used. Moreover, being so involved in the story-telling, support visitors to keep memory of what just heard once they come back home [22].

Relations between emotions and memorization find evidence in multiple researches. A study of the cognitive psychologist Donald MacKay, who conducted an “emotional Stroop test” (2004) [26], highlighted the connection between emotive state of users and their information retention. Different words were presented to users and each word had different color; users were then called to name the color as well as the words after a while. MacKay discovered that prohibited words, which were provided to obtain an emotional effect, were recalled more than others. The results of the experiment—and other ones conducted by his team—suggest that the emotional status in which we are when we do/listen to/watch at a subject can positively influence the registration of information into the short (or even long-term) memory.

Two academics in the fields of neuroscience and behavioral science, Arne Öhman and Susan Mineka, after several studies affirmed that while emotions emerge beyond our conscious control, their instinctiveness warn us of any threat or danger it may occur in our surrounding environment. For example, the feeling of happiness produced by a secure context, like our home, may influence us to choose lower risking behaviors—due also to lower defense barriers.

Other studies suggest that the brain focuses more easily on emotive stirrings. This was proved by the psychologist Harald Schupp [27,28,29] and his team, who experimented how different set of images and pictures may stimulate an emotional response in users. Schupp discovered the latter’s attention increased when emotional images were presented to them, pointing out that our attention is instinctively pulled to emotive subjects.

In another experiment, the psychologist Stephen D. Smith [30] proved that participants’ ability to remember neutral information was limited due to emotive stimuli presented very shortly beforehand. Hence, the phenomenon of the attentional blink—which generally occur when switching the attention from one subject to another–was somehow influenced by an emotional component. Smith and his team drawn down to the conclusion that we may not fully remember a subject if we focus our attention on something emotionally involving immediately before.

Some researchers pushed their studies foreword trying to understand which type of information memory recalls and how these are related to emotions. The social scientist W. Richard Walker [31] studied the memory recall of hundreds of users; he discovered that positive memories were easily remembered of the ones with negative significance. As a result, we can say that positive memories generally provoke emotional responses which are stronger than the ones provoked by negative memories [32].

While a positive approach to the users’ interaction with the surrounding environment (real and virtual) activate the emotional component, which is a powerful “tool” for storing and recalling information; it is also important that the acquired information is actively connected to the knowledge already present in our memory. How is this possible? For example, by making connections with one’s own experience, exchanging impressions and opinions with other visitors, finding oneself deeply projected, reflected and motivated within the physical and virtual world that is being traveled through, etc. [33,34]. Knowledge acquisition and retention are therefore not linear processes but moved by our emotions and the quality of our experiences.

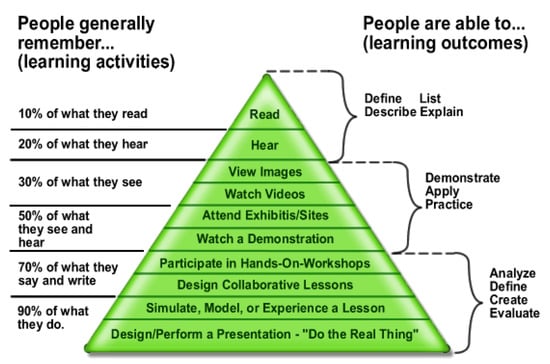

The American pedagogist Edgar Dale (1900, Minnesota; 1985, Ohio) found early in 1969 that our memory is more influenced by our multisensory experiences [35,36,37]. The more these experiences are special, full of emotions, the more we will remember them easily even after some time. From Dale’s studies the famous “learning cone” or “cone of experience” was born (Figure 1), which saw many re-modulations and adaptions according to the field of appliance in which it was took as reference.

Figure 1.

cone of experience (Source: This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0.) deducted by E. Dale.

Dale’s cone of experience tries to put in a progressive sequence the learning experiences and “the gradual loss of sensory information” as individuals moves from the bottom to the top [38]. In its original formulation, the cone was not meant to depict a value judgment of experiences, as Dale stated; it was mainly designed as a visual support to try to position the various types of audio-visual materials in the learning process.

Despite being a guide, rather than an effective model, the cone suggests which stimuli and channels were functional to soliciting attention, memorization and understanding in individuals; the concept was to practically involve all senses in the learning process and return the individual an active proponent of content. Dale explained indeed that our sensory organs needed to be awakening for retention and understanding to take place, taking advantages of multiple learning models. The latter were classified into two broad categories:

- -

- passive learning

- -

- active learning

Passive learning (reading and listening) may lead to lower memorization percentages while active learning (say and do) to the highest ones. Active learning is often based on concrete and contextual experience (so-called Experiential learning or learn-by-doing) [39]. This process takes place through the enactment of actions, behaviors and tasks in which users find themselves fielding their abilities and mental faculties for the elaboration and/or reorganization of new pieces of notion. Experiential learning allows users to handle new situations by developing adaptive behaviors and, at the same time, improving the ability to manage emotions [6,40,41]. Nevertheless, we understand not only through doing; the active role of users is not enough and must be accompanied by reflections and emotions, otherwise only mechanical actions would be memorized [42]. It is necessary to reflect, think, acquire awareness of the actions and feel their relevance for our life.

Both categories of learning take advantage of the sight which is the most developed sense [43,44,45,46]; it is a typical feature of the human being (and few other animals) which uses visual stimuli to explore, analyze and understand the surrounding space. About 80% of information that the human brain receives comes from the eyes. Not exclusively images, but also sensations and emotions have a relationship with the vision and the hearing. Indeed, the importance of sound information, combined with visual information, also emerges from Dale’s cone. Sound is capable of arousing an emotional reaction even more immediately than an image; the fusion of the two reaches the maximum of effectiveness [47]. Therefore, it is fundamental that the visual and auditory systems are effective as possible given their centrality for the influence on individuals’ behavior [48].

This apply also today to virtual technologies which exploit at the maximum the perceptive channel of the sight. Immersive VR excludes indeed the vision of the external reality from the users’ field of view by replacing the virtual one [49]. The progressive separation from real to virtual requires a cognitive effort for users who need to re-contextualize their actions and re-perceive their own bodies. This active process made by users allow them to feel included and “be present” in the virtual environment, abandoning the exact awareness of the real space in which they are set into. Moreover, the chance to use body gestures and physically move into the VR (thanks to hand devices or tracking tools) contribute to stimulate the sense of immersion.

Speaking about HMDs, their visual potential highly depends on the accuracy of virtual content. Such a precision is intended as the “degree to which the virtual environment simulates the real world” [50,51]. It can refer to (a) the physical-sensory accuracy, i.e., visual, acoustic and tactile; (b) the psychological accuracy with which the VR system replicate the psychological mechanisms experienced in reality; (c) the functional accuracy related to the operating principle of the elements in the virtual scene. As much as the visual aspect of VR environments and interactions simulate the ordinary world and behaviors, users feel the continuity from real to virtual, and consequentiality tend to experience the 3D reconstructed scenario. In general, what most influence the immersive VR, from the user’s point of view, are:

- -

- Point of interest. Users can be free to watch anywhere within the virtual scene. It is very important for researchers to study how to structure the simulated space and how to attract the users’ attention to certain spots. Recently, experimentations on sound recognition and visual cues are exploiting new modalities to address users’ eyes and make them move along a predetermined pathway.

- -

- Orientation in virtual space. It is necessary to provide users information that allow them to orient in VR by defining static and dynamic elements in the scene.

Therefore, the realism of the three-dimensional graphic representation enhances the users’ sense of presence within the virtual world because it is connected with the degree of awakening of sensory organs, especially the sight and the hearing. For this reason, the cone of experience of Dale can be still a valid framework to refer to when designing any virtual experience as immersive learning environments.

Dale’s cone of experience can be associated with Howard Gardner’s theory of multiple intelligences, developed in the 1980s [52,53]. According to academics, there are three general categories representing the ways we know and understand the world: visually, auditory and kinesthetically. Beyond these, there are other styles of learning which help awaken the sensory organs of each of us and help achieve self-education. Such styles were codified by Gardner as “intelligences” (linguistic, logical-mathematical, spatial, bodily kinesthetic, musical, interpersonal, intrapersonal, naturalist intelligence). Despite some criticisms in missing a supporting empirical research on the subject, the theory of multiple intelligences suggests eight possible ways to learn. It basically supports the same Dale’s concept of exploiting all human senses to experience the reality, but also virtual scenarios, in order to grab and assimilate information, sensing the context in which we are included and finally remembering what just experienced.

1.2. Digital Technologies and (New) Experiences of CH

Digital technologies allow to address cultural content to different user groups, providing new communicative strategies according to the devices at disposal. Three-dimensional environments can be enjoyed through a desktop-based tool (PC, tablet, smartphone) whose interaction can take place with a mouse, a joystick, a touch surface or through other peripherals (data gloves, motion sensors, etc.). Content can be organized like an interactive storytelling or a simple movie (following the criteria and the rules of cinema-like products). virtual applications can also be experienced into delimited physical spaces where users can walk into the defined area. Moreover, users’ position and orientation can be detected thanks to trackers and sensors. In this case, contents can be distributed in the space and they can appear on multiple levels of synchronicity and with different scales, pushing users to watch them in different directions and distances. Another device is surely the HMD: this solution, equipped with a stereoscopic viewer, offers a three-dimensional perception of the scenarios; it allows the perfect correspondence between the movements of the users’ head carried out in the physical space and those in the virtual one, thanks to a tracking system; the interaction with the environment and the virtual objects can be possible using a controller, like joypads, positional controllers or through interactions based on pupillary tracking.

All the above-mentioned technologies differ one to another, according to the following features [1,3]:

- the structural and ergonomic aspect of the technological solution, therefore relating to its physical accessibility (Can it be used by all users?), its technical components, its size (e.g., tablet vs. holographic showcase) and its location in physical space (e.g., desktop-based system vs. projections);

- the content of the technological solution, the language used, as well as its level of science and style;

- the interface design of the technological solution, its visual aspect, the recognizable elements (e.g., icons, written texts, images, visual effects), their position, size and logical coherence in order to be appealing and attractive to the final users;

- the possibility of interaction, the models of usage of the technological solution, the logic that underlies the accessibility of contents, their relationship, the possibility of having single or multiple interactions creating participatory experiences also with other users.

These features, according to how they are combined together from time to time, highly influence the UX of any CH object or site [4]. In order to design effective and meaningful experiences, we need to start from the analysis of the content, the core of our communicative project, rather than the selection of the technology. The latter is a mere technical support used to strengthen certain communication paradigms [4,5].

Specifically referring to immersive VR technology–applied to the ArkaeVision project–users can benefit at the maximum from the visual experience because of the way the content is modulated: a sort of perceptive storytelling can be applied, allowing users to follow a storyline through the sight and the hearing, but also making intentional choices after emotional stimuli are provided by the VR environment. We can say that a synesthesia [5] takes place when using immersive virtual technology: our senses are called to do their part in the process of meaning-making of the cultural experience. VR indeed allows to “travel through space and time without stepping out of the museum building. The potential to transcend the physical location of the built environment [...] has led museums to consider virtual reality as a necessary component in the arsenal of tools to educate, entertain and dazzle” [54]. Users can experience VR according to their level of technological alphabetization; they can decide to be active in the exploration and interaction or passive users; they can stay at home or use VR directly on the cultural site; they can deepen the content according to their interests and curiosities; they can experience VR as much as they want according to the time at their disposal. The possibility to visit ancient locations, approach ruins and statues no longer existing, interact with typical characters, makes visitors feel involved in the exploration, be careful to details (as it is not always possible in physical cultural visits) and be decision-makers of any action and interaction—indirectly enhancing their knowledge [55].

Unfortunately, not all the users can take advantage of VR technology. People with visual disabilities (blind, visually impaired…), cognitive limitations (epilepsy, schizophrenia…) or, simply, disturbs connected to the body’s equilibrium, cannot experience tridimensional immersive products. Another issue can be the motion sickness(dizziness, nausea, disorientation) which is typical of viewers and it related to the well-known conflict between the vestibular system and the visual system; such a discomfort does not prevent users to experience the immersive VR, but, in some cases, they prefer not to try it for precaution or may feel bad afterward. Research on this topic has shown that the sensory conflict mainly depends on the interaction models, how the 3D experience is set, which are the requested movements rather than by technology in itself [56]. As a consequence, a rich variety of locomotion techniques has been developed [57,58] to comfortably explore the virtual environments.

To an end, in the field of digital cultural heritage (DCH), VR technologies should allow to see and feel cultural artifacts and landscapes at 360 degrees. Experiencing the objects of material culture means indeed to involve emotions arisen from all human senses. The sight can help to see and appreciate a statue or a place which have undergone modifications along ages; the touch can help to feel shapes, forms, textures and even the temperature of some artifacts trying to figure out how they could be in the moment of their maximum splendor; the hearing can provide imagination with details about the past, generating emotions.

2. Experience of the Past and the Present through Gamified Perceptive Storytelling

The modern reflection on the past represents a key element in VR applications for DCH, both from the points of view of the plot and the characters. These differ in the construction (a) by the complexity of events and interactional dynamics and (b) by the plausibility of facts and subjects [59,60]. The setup of all these elements makes the storytelling and the game-based environments favorable for educational activities [61], gradually shifting the quality of VR applications from the purely playful to the educational level.

The elements of mystery, exploration and recall of ancient worlds have always been crucial factors for planning any immersive narrative environment, like ArkaeVision VR application, as well as for shaping up the protagonists and their adventures through gamified solutions [62,63]. Addressing the digital narrative structure poses some crucial issues connected to the storytelling strategies and to the rules set up by the serious-game domain [64]. First of all, it is a matter of designing a VR application with a high level of immersiveness and with reliable elements of user interaction-not easy to realize in the virtual, given the complexity of human movements and behaviors. Second, the narrative plot—on which the user’s personal adventure is set upon—is not linear since it must adapt at the user’s choices into the VR experience. Moreover, the aim of an interactive VR experience is generally to provide engagement and learning effects too. Such a goal forces researchers, developers and graphics to harmonize the entertaining and the scientific aspects of the representation of the past. As a matter of fact, the activity of dissemination, done by archaeologists and historians, follows different ways and criteria in comparison with the same activity performed by artists and entertainment operators. Dealing with the reconstruction of costumes, music, environments and every item linked to a particular historical context, imposes indeed two different perspectives: scientists tend to rely on documents and archaeological records, in order to create an environmental setting as close as possible to the historical truth; whereas, artists and storytellers do not pursue the historical “reality”, but the chance to make the public closer to their “imaginary” of that Past, as to recreate the “taste” of the epoch they are representing. For instance, our feelings about some movie genres are associated with music styles which have marked the history of cinema (e.g., western or peplum soundtracks) and which provide us a strong sensory immersion; nevertheless, such music was not played at that time. The same goes for the scenographic style of movies: Spielberg’s “Schindler’s list” was produced in black-and-white as to recall the feeling of video documents from the 40 s, i.e., a powerful incentive for our emotion, but certainly does not resemble the way reality looked like [60]. It is not easy therefore to harmonize these two perspectives. The paradoxical effect of the convergence of multiple professionals and points of view on the virtual reconstructions of the past is that a VR application may become in itself a sort of artwork—a new outreach for VR applied to CH. Acting on the basis of individual capability to evoke the atmospheres of an ancient world and using existing emotional “placeholders” may thus produce a stronger impact, empowered by the user’s consciousness of the scientificness of narration [65,66].

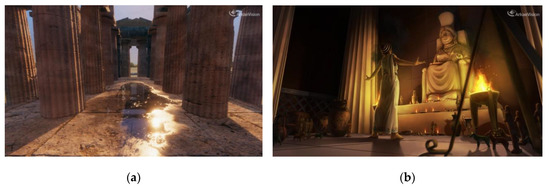

In the ArkaeVision VR application, the experience of the Present and the past relates to the city of Paestum, located in the south of Italy, Campania region. Its long lasting tradition [67,68,69,70] and the multiplicity of the historical events that characterized the city have been the fertile ground to develop a gamified perceptive storytelling about the Etruscan funerary rituals and celebration habits, the civilization conflicts, the features of classic deities, the priestesses’ profile, etc. Paestum, since the Greek colony of Poseidonia (fifth century BC), through the Lucan age, the Roman empire, up to modern time, in the framework of the Bourbon reign as protagonist of the Grand Tour epoch, will be enjoyed by visitors on a deep emotional level. The inspiration to the vedutismo pictorial style of 3D reconstructions, the warm colors of scenes, the natural soundscape and the intimate social interactions are choices made on purpose by authors (Figure 2). Thanks to storytelling and evocative effects, in the ArkaeVision project, objects and places turn into means to create contextual historical dramas on specific themes, built on data previously checked by scientists and experts in CH and DCH [5].

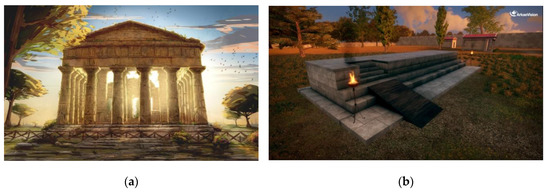

Figure 2.

Screenshots taken from the virtual reality (VR) application of ArkaeVision Archeo: (a) exterior of the naos in the present day and (b) interior of the naos in the fifth century BC with the priestess Ariadne. Copyright © Digitalcomoedia.

In the next paragraph, the historical background of the city of Paestum will highlight the importance of some archaeological structures, still traceable and today accessible, that will be used as natural setup for the VR application. Sacred artifacts, everyday-life objects, costumes and rituals will be described and reused for the virtual storytelling as well as characters and voices will be presented and then transposed in the virtual Poseidonia.

2.1. Historical Background: The Temple of Hera II and the Poseidonia’s Landscape

The original name of Paestum was Poseidonia; it was a Greek colony founded on the west coast of Italy, 80 km south of Naples. It was a very important trade center, first conquered by the Lucanians and then, in the III century BC, the city became an important Roman colony with the Latin name Paestum. Today, it is one of the most important archaeological sites due to its preserved Greek temples [71].

According to Strabo [72], Poseidonia was founded by Greek colonists coming from Sibari; the date of Poseidonia’s founding is not given by ancient sources, but the archaeological evidence: approximately the 600 BC [73]. The colonists built fortifications on the coast before moving inland to build their city. Between the VI and V centuries BC, the city was planned out in a precise grid pattern and surrounded by walls. In the central part of the city, in a space of about 10 hectares, a large agora was built—the political heart of the city. Inside it, the most representative public monuments could be found: the heroon, dated around 520–510 BC, dedicated to Poseidon, the mythical founder of the city, the ekklesiasterion, built around 480–470 BC for political assemblies and the temple of Zeus Agoraios (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Aerial view of Paestum, looking northwest; two Hera Temples in foreground, Athena Temple in background, the modern museum on right. Copyright © V. Alfano (Source: Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=21788866).

The colony prospered so that by the VI century BC there was an important sanctuary [74] in the countryside (locality of Foce del Sele) as well as and monumental temples [71]. In the southern sanctuary two Doric temples were erected, the oldest one, the Temple of Hera I of the 550 BC, named by archaeologists in the 18th century “the Basilica” because someone mistakenly believed it to be a Roman building and the Temple of Hera II, also known as the Temple of Neptune (it also is possible that the temple originally was dedicated to both Hera and Poseidon), built around 460 BC [75]. On the highest point of the town, far away from the Hera Temples going north way, the Temple of Athena can be found. It was built around 500 BC, and it was incorrectly associated with Ceres.

In the late fifth century BC, Poseidonia was attacked by the Lucanians, a population of Samnite warriors, coming from the hinterland. The conquerors, who changed the name of the city to Paistom, respected spaces and functions of the places of the Greek city [76].

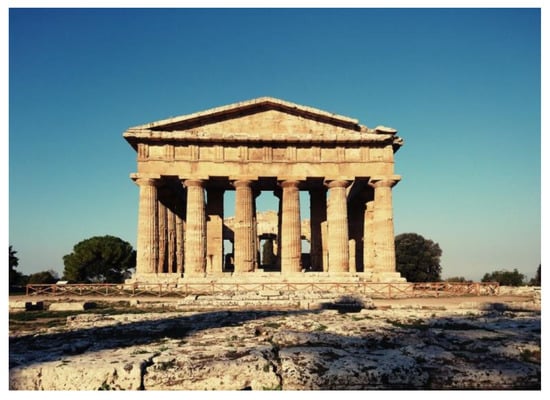

The monumental and best preserved of temples at Paestum is the so-called Temple of Neptune, built in the Doric order around 460–450 BC, though it was almost certainly dedicated to Hera [77] –the subject of ArkaeVision Archeo reconstructed environment. The frontal view of the temple shows that the entablature is complete. However, no traces of suitable statues have been found anywhere at Paestum and it is clear that the pediment was not carved (Figure 4). However, it may have been painted, and would have given a rather different impression from its gaunt seriousness today (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

The view of the temple from the east side: the front façade. Copyright © V. Di Marco (Source: Own work CC BY-SA 4.0. Link: https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=71188205).

Figure 5.

Chromatic reconstruction created for the exhibition “Colori nell’antica Paestum. Vita dei colori e colori della vita”. Archaeological Museum of Paestum (Link at the video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=11&v=JlCdr5hYb0Q). Copyright © Archaeological Museum of Paestum.

The temple, built with local limestone, stands on a crepidine of three steps and has a cell with pronaos and opisthodomos, both in antis (sort of gates to access the temple) [78]. It is a Doric temple with six columns along its shorter sides and fourteen columns along its longer sides. The huge cella, accessed by four steps, was divided longitudinally into three naves, of which the larger central one, by two orders of seven overlapping columns. The entablature was formed by a smooth architrave and a frieze, made of sandstone, with un sculpted triglyphs and metopes. The whole structure had to be plastered and painted. The roof of the temple was supported by wooden beams and was decorated with polychrome terracotta.

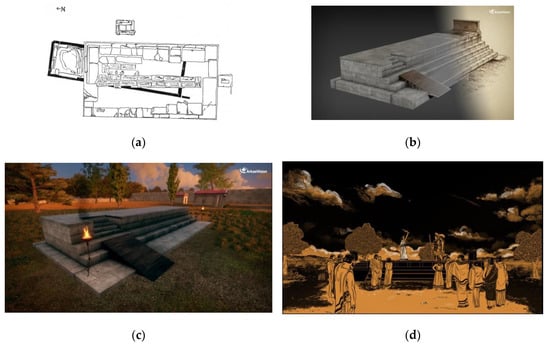

It was probably dedicated to Hera, the bride of Zeus and main deity venerated in Poseidonia [79]. In front of the main (east) front of the temple there are the remains of two altars: one large, contemporary to the construction of the temple, and one smaller, i.e., a Roman addition (I century BC). Such altars are where ArkaeVision Archeo storytelling take place; for this reason, we studied their structure and dimensions (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

The I century altar BC in front of the “Temple of Neptune” or “Hera II” in different images: (a) (Source: Cipriani M., 1997. Il ruolo di Hera nel santuario meridionale di Poseidonia. In “Héra. Images, espaces, cultes. Actes du Colloque International de Lille (1993), (Coll. CJB, 15)”, Napoli, pp. 211–225, ISBN: 9782918887201. doi:10.4000/books.pcjb.950) archaeological excavation, (b) digital drawing, (c) VR animation and (d) digital fiction. Copyright © Digitalcomoedia.

The altar was generally built in front of the main entrance of the temple; people looked at it from the outside of the temple and, for this reason, its shape was usually beautiful. Altars were made in such a way that the greatest number of people could attend the rituals.

The offerings and sacrifices were made on the altar; part of the offering in nature was burned on it, accompanied by libations. Sacred pits welcomed offerings and sacrifices for deities. Everything could potentially be sacrificed or dedicated to the god; some animals, such as the piglet and the horse, were reserved for the chthonic deities and Poseidon, while for others there was no strict distinction. Particularly solemn sacrifices of dozens of animals (hecatombs), generally oxen, were made on important occasions or to propitiate the divinity and the meats distributed among the citizens. The bloody offer was often replaced by fruits, bread or fruits with symbolic meaning (pomegranates, ears of wheat) [80].

Not only altars, but also sanctuaries. Objects of intrinsic or symbolic value were dedicated to the divinity, which present a considerable variety in the typology; the dedications could be public or private. The precious artifacts were kept inside the temple or in special buildings, the most modest probably under stoài or outdoors [81]. Votive objects were used by the ancient Greeks to thank the gods for granting them a wish. They could be of wood or textiles through simple statuettes of clay, marble or bronze statues, till arriving at the construction of entire buildings.

Some of these votive objects are used to characterize the VR environment of ArkaeVision Archeo.

2.2. Sacredness, Devotion, Surrealism

In the temple of Hera there was presumably a big statue of the Goddess whose care was in charge to a priestess—the only one admitted into the sacred area.

Both figures are reused as characters (active or passive) of the VR application with the function of revealing pieces of knowledge to users.

2.2.1. Goddess Hera

The cell of the temple was the house of the cult of the goddess Hera. Although we do not know the iconography, comparisons can be made with the votive statues and the testimonies on the cult of Hera in other locations [79,82]. Images from the first quarter of the fifth century B.C. represent her as majestic and solemn, often enthroned and crowned with the polos (a high cylindrical crown worn by several of the Great Goddesses); Hera may hold a pomegranate in her hand, symbol of fertile blood and death (Figure 7a).

Figure 7.

(a) Hera on the throne, with phiale on the right and pomegranate on the left (fifth century BC). Copyright © Archaeological Museum of Paestum. (b) Attic red-figure kylix of 440–430 BC. Work of the Painter of Kodros, depicting the goddess Themis, second holder of the oracle of Delphi according to Aeschylus. Copyright © Antikensammlung in Berlin.

Hera is generally considered the goddess of women, marriage, family and childbirth in ancient Greek religion; she is one of the Twelve Olympians and the sister-wife of Zeus. A matronly figure, Hera was the protector of married women and weddings. One of Hera’s main features is jealousy and her vengeful nature against Zeus’ numerous lovers. It is therefore not surprising that in her cult, men were often present during the sacrifices [83].

2.2.2. Priestess of the Temple

The young women consecrated to the custody of the cult, in ancient Greece, represent a phenomenon widely investigated by the history of religions; the priestess is mainly linked to the figure of the Pythia of the Oracle of Apollo, in Delphi (Figure 7b).

Greek priests and priestesses did not necessarily control the sacred knowledge of cults and rituals, but administered the places dedicated to these sacred actions. In this way, they also watched over the communication between men and gods, as mediators. Women were meant to serve the female gods and virginity was sometimes required of them. However, priests underwent certain rules for the duration of their office (e.g., chastity, food prescriptions) and were required to wear specific clothing according to the priesthood. There was no real priestly caste, but there were only priests of a specific divinity within a specific sanctuary.

There was a long debate, and still it is, about whether women were permitted to sacrifice or not [84]. It would seem that women were only able to conduct slaughtering of sacrificial animals in specific ritual contexts such as Thesmophoria [84]. In the Greek world, on the basis of iconographic evidence, two of the most important communicative tasks, guarding the temple and making the bloody sacrifice, were assigned exclusively to priests. The priestesses, as custodians of the divine house, in order to enable communication to take place, allowed then to enter the sanctuary while priests maintained a more active role in the ritual context with bloody sacrifice.

For ArkaeVision Archeo, having a leading female role who accompanies users along their journey is appropriate for the historical period and the solemnity of her relevant role.

3. Virtual into Real. The ArkaeVision Project

ArkaeVision is born out of a three-year project financed by the MISE, “Research and Development” actions, thanks to the Fund for Sustainable Growth—“Horizon 2020 Call”. It was designed and developed by Digitalcomoedia, a company active on advanced digital content, together with the National Research Council (CNR), Institute for Technologies Applied to cultural heritage and Beyond Tech., an innovative startup expert in gamification.

ArkaeVision, in its broadest vision, is an integrated digital experiential platform that provides different ways of enjoying cultural heritage. It is composed by (a) an online portal, accessible from any mobile device (smartphone or tablet) and desktop-based system, (b) an immersive VR application (ArkaeVision Archeo, subject of this contribution) and (c) an AR application (ArkaeVision Art)—soon available at the Archaeological Museum of Paestum [85].

In general, the ArkaeVision experiential platform aims at:

- introducing elements of spectacularization during the immersive VR experience recalling the attention of users on the archaeological sites and the objects exposed at Paestum;

- developing new forms of enculturation based on the stimulation of intimate feelings and emotions, which will presumably help users see, feel and, finally, relive the past.

- creating an infrastructure capable of expanding the museum supply, enhancing its visibility, putting in connection places with artifacts while promoting participatory and social dynamics.

In (b) ArkaeVision Archeo, the experience is designed to involve users in a circular and iterative way. It starts when they first consult the project’s web portal and the pages dedicated to the archaeological site and/or the museum. ArkaeVision Archeo can be used once the users arrive at the museum, after having booked an explorative session (Since the web portal has not been optimized yet, the VR experience can be booked directly at the Archaeological Museum of Paestum - updated April 2020). Users can virtually visit the temple dedicated to Hera II of Paestum, in the first half of the fifth century BC, wearing the HTC Vive and using hand controllers; here they can interact with a digital actor, the priestess Ariadne, who will guide them virtual tour presenting the beliefs, the values and the ancient of ancient population of the Magna Graecia city (Figure 8). The experience is completed when they conclude the VR experience; users are profiled thanks to an automatic monitoring of their actions during VR exploration. The data collected allows the UX to be adapted to their needs and interests for future occasions, unlocking new contents or accessing hidden objects and places.

Figure 8.

A visitor wearing the HTC Vive to virtually explore the temple of Hera II. Copyright © Digitalcomoedia.

Users can take advantage of two explorative modalities: an emotional and semi-guided visit, where events and facts evolve in the storyline catching their attention and pushing them to follow the visit; in this phase, they can do some actions, like walking in VR, watching around, choose what to explore, but always guided in the experiential pathway by the digital actor; a didactic and free exploration, where the users can choose which information to deepen, accessing specific points of interest or 3D assets, plan what to do and where to go in VR exploration; here they are alone with no guide.

The gamified perceptive storytelling of ArkaeVision Archeo takes place in the area referable to the temple of Hera II, located (in reality) on the occidental side of the archaeological park of Paestum. The temple rebuilt in 3D, the surrounding landscape, vegetation elements and nearby architectures are depicted following the vedutismo pictorial style of the IX century.

The playable area corresponds to the interior of the temple’s naos, specifically the frontal and side colonnade and a modest external section; then, the exterior of temple, including a sacrificial altar and a lateral structure called donari. Inside the temple a digital character guides the users for the entire duration of the experience, interacting with them and making them a protagonist of the narrative (Figure 9). During this story, the users have the opportunity to deepen the myth of Hera, know the problems of the attribution of the temple and understand its ancient uses through the observation of a ritual performed on the external altar.

Figure 9.

Screenshots taken from the VR application of ArkaeVision Archeo: (a) interior of the naos in 500 BC with the priestess Ariadne and (b) sacrificial altar in front of the temple. Copyright © Digitalcomoedia.

ArkaeVision Archeo requires users to wear the HTC Vive viewer to live a transition from the current scenario of contemporary Paestum’s archaeological site to 3D reconstruction of the ancient Poseidonia. Users are also asked to use hand controllers to guide the experience.

Scenography, art and traditional filmic direction were integrated for the digital reproduction to represent the atmosphere of Poseidonia in the fifth century BC. An experience in History cannot be separated from truthfulness and for this reason a referencing study on architectures, characters and lifestyle was done to faithfully reproduce the atmosphere of the past. In addition to the scenography and to the architecture of the archaeological site, characters have a great relevance too. In ArkaeVision Archeo, the main character is Ariadne, the priestess of the temple of Hera who drives visitors to the discovery of places and objects of the fifth century BC. These aspects are further deepened in Section 3.3.

3.1. ArkaeVision Archeo: Game-Oriented Components

The main components of ArkaeVision VR application relate to the interactive exploration set upon a precise storytelling and to the game-based activities that users can accomplish during the VR experience [86,87]. It is important to explain that ArkaeVision is not properly a serious-game and it does not fully exploit the features of the gamification; yet, it is intended to influence people’s natural attitude towards the socialization, learning, achievement, self-expression and fun; moreover, it partially follows game design elements. Nevertheless, authors refer to the framework “learning mechanics–game mechanics (LM-GM)” [88] which considers serious games as an agglomeration of two types of mechanics, namely those related to learning (LM) and those related to gaming (GM). They also take advantage of another framework “activity theory-based model for serious games (ATMSG) which can be considered an evolution of the LM-GM model [88].

Relying upon these assumptions, ArkaeVision Archeo can be described through its (a) game-oriented mechanism, which allow users to get to know the VR context and explore it; the game-oriented strategies that users can take advantage of, to know more about the historical period, environment, rituals and beliefs; the game-oriented objectives with the purpose of entertaining users, but especially educate them (experiential learning—see Section 1.1).

Deepening on the general infrastructure of ArkaeVision Archeo can be read in [85].

3.1.1. Mechanism

The exploration of the ArkaeVision VR environment mainly refers to the mechanism of information accessing [62]: ask/answer questions, see/listen to/read information. Users can listen to the guiding voice, meet the guiding character and follow her along the explorative path; moreover, they can access extra information, reading them in superimposition in the immersive visualization or deciding to skip them, by clicking on the hand controllers provided with the viewer. Content is also diversified by type of user (user profiling at a time prior to VR exploration—children, expert, common visitor—when a person books the experience on the web portal) and by style of narration (folk tale, in-depth narration, general narration). In ArkaeVision Archeo the story is overwhelming, appealing and captivating.

3.1.2. Strategies

The virtual exploration of ArkaeVision Archeo relies upon a series of game-oriented strategies which help users to follow the storyline that unfolds dynamically, depending on their choices, but still univocal (the ending is the same for all users). These strategies are:

- -

- Help. Digital actor’s assistance, tips, initial tutorial, warning messages are presented in order to assist users during VR exploration and make feel them as autonomous as possible.

- -

- Storytelling. Cut scenes, leading stories, parallel stories, deepening and visual metadata are presented in order to support users’ comprehension of what they see, feel and “touch” in the VR environment.

- -

- Measuring goals. Achievements, performance records, score, success levels, timing are recorded by the system and visualized by users during VR exploration, in order to motivate them to proceed with the story. Such goals are useful in the further phase of ArkaeVision Archeo experience, when users access the web portal: they can consult the explored VR areas, the listened stories and see what they have missed [85].

- -

- Scoring. Quizzes can be found during VR exploration; they positively influence the information retention, “forcing” users to recall at their attention data just acquired and elaborate them so to answer the quizzes [89], by using the head controllers. These quizzes are set in some points of VR exploration to stimulate users’ attention and memorability; related scores can be consulted when users access the ArkaeVision web portal and they can be useful to measure the level of deepness of the experience done, and the quantity and quality of information collected.

3.1.3. Objectives

In ArkaeVision Archeo, the exploratory experience [90] allows users to follow the storytelling divided into progressive steps and guiding them till the end. The latter brings the users back to the starting view of VR exploration—a sign that they have finished the story and accomplished all the required tasks. The time passing from the start to the end of the exploration allows users to get a score in a ranking scale, which can be consulted in the ArkaeVision web portal, which somehow identifies users’ ability (Did they perform as good/agile/fast/correctly by answering to the questions of VR exploration?).

Hence, two goals of the immersive exploration of ArkaeVision Archeo relate to:

- -

- Narration. Completion of a narrative-based challenge, create/discover a narrative node, know the story and reach the end of the VR experience.

- -

- Interaction. Users follow the narration thanks to the guide, the priestess Ariadne, who poses questions, quizzes and push them to specific areas of the VR environment. Users can do what they are require to, by addressing the gaze in the right direction or using the hand controllers (point-and-click technique).

3.2. ArkaeVision: Design of the Immersive Virtual Experience

The ArkaeVision Archeo experience is limited to 15 min and users are free to take off the viewer whenever they want. However, the storyline flow, conveyed by Ariadne’s verbal interaction with the users, is purposefully conceived to stimulate them in completing the exploration. The experience is designed to be done by one person at a time.

More in detail, ArkaeVision Archeo takes advantage of some gamification elements both in the storyline (by means of artifacts to be found like in an adventure game) and for the interaction modalities (similar to those of role-playing games) as a combined approach to maximize users’ involvement and to actively stimulate them to deepen the knowledge [64,91].

Users can play either the aforementioned experiences, in sequence or just one by one. Before the experience begins, indeed, it is possible to configure the system to enable both options either by means of the museum personnel or even automatically, based on the information previously provided by users.

3.3. ArkaeVision: Aesthetics and Visual 3D Modeling

ArkaeVision Archeo is designed to provide a strongly visual-oriented experience; consequently, both VR environment and characters was developed with the utmost attention to visual realism and verisimilitude to the aesthetics of ancient Poseidonia–Paestum. This challenge involved the usage of advanced visual and programming techniques optimized to run on the chosen hardware platform.

3.3.1. D Modeling

The 3D modeling process behind ArkaeVision Archeo is based on a complex pipeline of work well consolidated in the CG industry [92]; the actual polygonal modeling follows the creation of visual references made by means of hand drawing performed by graphic artists.

After a number of reviews aimed at refining the drawings to better capturing and describing the essence of the environment and of the main character, polygonal modeling with subdivision surfaces was used for translating the drawings into corresponding 3D models compliant with the platform requirements (in terms of polygonal budget assigned to each entity as well as to the entire virtual environment) [93]. In the prototype creation stage, the first visual proposal for both the Ariadne character and the general appearance of Paestum’s surroundings (Figure 10) was sketched by hand and progressively refined until they matched the desired visual mood.

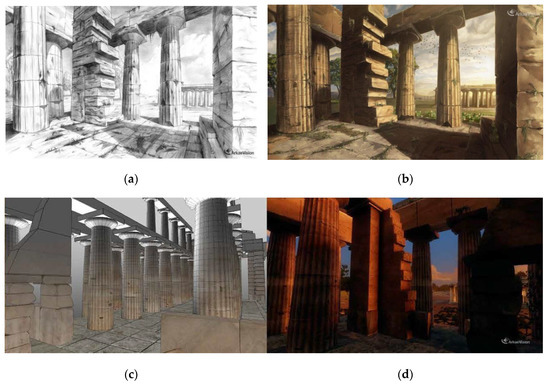

Figure 10.

Shots aimed to study how to reproduce the atmosphere of the past: (a) first a black and white drawing, (b) a colored version, then (c) a digital canvas till arriving at (d) the 3D model. Copyright © Digitalcomoedia.

This first approximation was therefore the starting point for the 3D modeling stage which was also characterized by a set of requirements such as:

- -

- the exclusive usage of polygonal modeling techniques instead of other more CAD oriented methods exploiting parametric surfaces (e.g., NURBS/Spline modeling);

- -

- no subdivision surfaces used to increase the polygonal resolution;

- -

- no more than 64,000 vertices allowed for each single component;

- -

- UV coordinates ranging between 0 and 1 (no UDIM UV Mapping supported);

- -

- low textures number with atlas-based texture management approach;

- -

- hierarchically linked meshes according to topological components arrangement, enabling visually realistic motion through kinematic chains;

- -

- compliance to conventions regarding labeling of local axes and their positive direction.

The resulting models underwent an accurate rigging and skinning stage, aimed at achieving the most realistic and lifelike behavior of character’s joints and facial motion. In particular, angle-based joints shaping allowed to optimize the aspect of critical joints such as clavicles and elbows (which are naked in the Ariadne model) when approaching high angular values. A final step of 3D paint-based vertices deformability has also been performed to further refine the dynamic aspect of the character.

3.3.2. Characters

The production phase of the digital character exploited the most modern techniques made available to the CG artists [94]—as highly detailed 3D sculpting, high dynamic range images, particle systems, motion capture, just to name a few—to achieve a reliable result and with a well-defined visual personality.

Starting from the pre-production artworks, a digital sculpting version of Ariadne was created, which was subsequently retopologized (which means redefining the mesh of the 3D models at a lower resolution) and optimized in terms of their topology and polygons count for real time rendering. Even the dress was generated through software fabric simulation, to achieve high levels of realism.

To create the digital character, motion capture and lip-sync cinematographic techniques were used. Through a dedicated hardware, the movements and the acting of the performer who played Ariadne were captured. Performance capture has allowed to adequately convey the acting and the director’s intentions to the digital character.

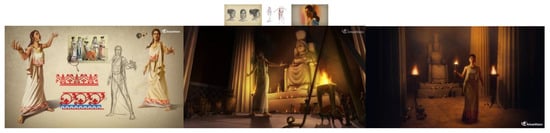

The realization of Ariadne, went indeed through three phases (Figure 11):

Figure 11.

Sequence of images of the performance capture phases. Copyright © Digitalcomoedia.

- -

- Philological analysis phase: the development of digital actor representing Ariadne required an accurate research and study’s phases to characterize a well-defined personality with an identifiable behavior in the historical era.

- -

- Pre-production phase: creatives and developers studied the features of the character, aimed at accurately identifying the aesthetic characteristics of the digital actor from an ethnic/anatomic point of view as well as for what was related to its aesthetic details (dress, jewelry, hairstyle).

- -

- Acting and directing phase: last phase was the Ariadne’s characterization from the acting point of view. Phrases, movements and expressiveness were minutely analyzed and appropriately interpreted by the actress who played the part, subsequently transferred, through Performance Capture techniques, to the CGI character.

Here below some visual examples of the pipeline of work done for ArkaeVision Archeo, especially for the Priestess Ariadne (Figure 12).

Figure 12.

Sequence of images showing how creatives and developers conceptualized the character of the Priestess Ariadne from scratch to real-time 3D models. Copyright © Digitalcomoedia.

3.4. ArkaeVision: Learning Analytics

The theoretical framework, on which ArkaeVision Archeo is based is presented in Section 1 and Section 1.1 of this contribution. In general, the main research questions relate to how supporting the activation of curiosity in users and how to maintain attention and interest in order to let the learning processes to take place; moreover, authors want also to understand how to use emotions to develop new forms of narration at the museum and help users remember them more easily.

The experiential model of Kolb and Freitas [6] stays at the basis of the VR application (Figure 13), useful to investigate (a) the level of abstraction reachable through a technological-mediated immersive experience. Such a level of abstract may help users to feel immersed into the virtual world of ancient Poseidonia thus enabling the meaning-making process to happen.

Figure 13.

Elaboration of the experiential model of Kolb and Freitas (Source: Arnab S. et al., 2015. Mapping learning and game mechanics for serious games analysis, 2015).

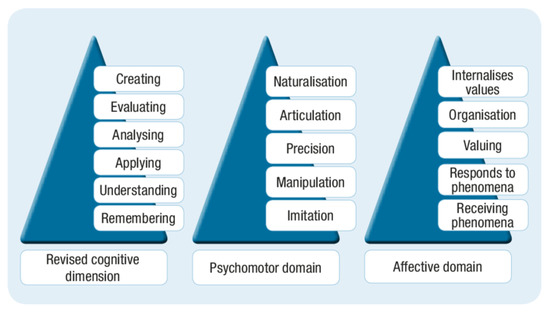

Bloom’s Taxonomy is taken as reference too [7,8,9,95]; it generally defines the steps of any learning process and, for ArkaeVision Archeo, it serves to evaluate (b) the learnability and (c) memorability of the gamified perceptive storytelling. Following the domains in which Bloom subdivides the experience—cognitive, affective and psychomotor—we have specifically studied (Figure 14):

Figure 14.

Bloom’s taxonomy: cognitive, psychomotor and affective domains (Source: Pouliou A., 2019. Cedefop (2017). Defining, writing and applying learning outcomes: A European handbook. Luxembourg: Publications Office. 10.2801/566770).

- -

- The level of users’ attention, memorization and elaboration [8,96]; these three, at the end of the project, should lead to a clearer vision of the potential inherent in the immersive VR application regarding:

- knowledge acquisition (understanding and learning)

- acquisition of certain skills based on newly acquired knowledge (experience)

- knowledge retention (storage and processing)

- -

- The receptivity of users, i.e., the faculty to perceive and beware of specific visual inputs, verbal suggestions and, etc., scenario after scenario, along the VR exploration [7].

- -

- The users’ emotional response, i.e., the reaction to environmental stimuli, so to respond in a condescending or spontaneous way [7].

- -

- Finally, on a psychomotor level [97], the basic movements that users perform are considered significant as well as the dexterity of the movements, i.e., the ability to adapt to a virtual or alternative scenario.

Referring to learning analytics, authors have carefully selected mechanisms, actions and tools as it follows.

3.4.1. Learning Mechanism

In ArkaeVision Archeo, users ideally follow a path of gradual discovery of the cultural environment (the temple of Hera II and the city of Poseidonia); they approach the sequence of events with their actions and choices to obtain a “reward”: an understanding of the effects of their narrative choices on the general storyline and the continuation of the narration up to the epilogue of the story. The users must carry out limited actions during their exploration, like reflective and motor’s decision-making.

The mechanism (or paradigm) here employed is therefore, Action/task: one or more specific task that users perform in the VR world in order to continue the story and/or get a reward. A task could be a problem to be solved, an exercise to be carried out or even a physical activity or mental process to be undertaken. In ArkaeVision Archeo, for example, users are asked to choose a votive object to be offered to the Goddess Hera, selecting the right one, in order to do not incur in Hera’s curse.

3.4.2. Learning Actions

The memory of each individual is influenced by multiple factors and produces a plastic record that can change depending on the positive or negative experience that generated it and from the time elapsed from when we experienced it to when we recalled it.

In the case of ArkaeVision Archeo, the memory of the VR experience is indeed influenced by the users’ ability to understand, analyze and evaluate the environmental conditions and, consequently, decide and act, how to proceed with the exploratory activity. The memory, contextual and a posteriori, passes necessarily from the understanding of what the users are experiencing, from the storage of the emotions and the readability of the proposed contents.

Examples of learning actions in the VR application are when users are asked to imitate the Priestess Ariadne to extend their greetings to the Goddess in a proper manner; or, to recite the Pray to the Stars as Ariadne does. Moreover, users have to select some votive objects to be gifted to Hera in the donari by distinguishing the correct ones among a bunch of items; or, users have to deduce that they cannot go closer to the Goddess’ statue through the words of Ariadne and the “physical” limits that the system poses.

3.4.3. Learning Tools

ArkaeVision Archeo uses various learning tools:

- -

- Information graphics—art, graphics, illustrations, drawings, 3D effects;

- -

- Textual information—metadata of 3D elements (age, provenance, dimensions,), analogies, definitions, historical facts, list of activities to be carried out;

- -

- Multimedia—animation, cinema, speeches, videos, 3D models, evocations;

- -

- Problem-solving—narrative nodes and crossroads, puzzles, challenges.

These are located throughout the experiential arc of the VR exploration and they are related to graphics (360 panoramas, pictorial style of 3D modeling, etc.), animations (motion capture of the virtual guide Ariadne in order to make her appear “natural”) and information units.

Some examples are the visual aspect of the Temple of Hera, reconstructed in the fifth century B.C.–users may make comparison between what is left today and this ancient view; 3D objects like vases and small votive statues are supplied with information set aside of the visualization (so called “3D spatialized metadata”); changes in the pictorial style of images can be seen to differentiate the main storytelling from the side stories.

4. UX Evaluations

In order to probe and test the research questions of ArkaeVision Archeo, it was necessary to conduct User eXperience Evaluations (UXEs).

Two occasions were selected to carry out such analytic activity. A first UXE was planned in November 2018, when ArkaeVision Archeo was first released to public in its demo version. The occasion was the Archeovirtual exhibition (www.archeovirtual.it), organized by the CNR at the Archaeological Museum of Paestum. A second UXE took place in February 2019 during the TourismA festival (https://www.tourisma.it) in Florence and the VR application was in its final stage of development.

The two occasions had some points in common, but also differences which brought authors to adjust the UXEs in terms of conduction and logistics. Nevertheless, given the importance of having comparable data and similar methodology, evaluations fulfilled a precise scheduling and evaluative tools.

In Paestum there were mainly a young target such as schools, universities, families and young tourists, given the type of the event (more didactic and formative); in Florence there were professionals, experts in the field of CH and DCH, private companies and families due to conferences, workshops and exhibition areas planned in the festival. For such a reason, targets were different, and results could be unbalanced. To overcome such issues, the evaluative tools (see Section 4.1) were studied and compiled with the assistance of cognitivists and pedagogists of CNR in order to have precise questions, specific tasks to accomplish and, at the same time, a quite large grid of reference for evaluating the data collected according to ages, cultural background and technological alphabetization.

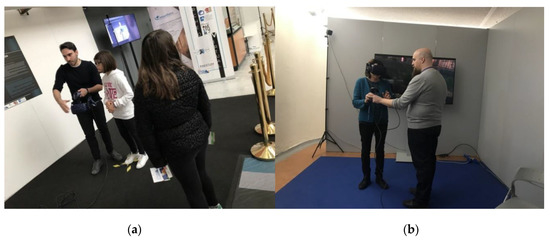

Both in Paestum and in Florence there was enough space to live the experience quite comfortably; the dedicated area was indeed of about 6 × 6 m with the following equipment (Figure 15):

Figure 15.

Pictures of two evaluative sessions: (a) during Archeovirtual exhibition, Paestum and (b) during TourismA, Florence. Copyright © CNR ISPC.

- -

- An interactive area of about 3 × 4 m where users can physically move, indicated by a PVC black/blue carpet, a web tensioner, tables and chairs;

- -

- A workstation dedicated to ArkaeVision Archeo with PC, Monitor 55 inches, HTC Vive viewer and trackers;

- -

- A remote station for assistant/technician useful to guide users throughout the experience with PC and Monitor—27 inches.

The affluence of people was quite the same on both occasions and a high number of data were collected.

4.1. Goals and Methodology

The reasons for evaluating ArkaeVision Archeo are largely presented in Section 1.1. and Section 3.4. They refer to three main goals:

- A.

- The effectiveness of the way of experiencing the content—by means of an immersive viewer and hand controllers. The authors want to understand if the system is usable and the quality of users’ interaction—as immediately and natural as possible.

- B.

- The emotional component of VR interactive exploration. Emotions in ArkaeVision Archeo should help the learning process to be activated [98,99] by analyzing the narrative nodes and how they were stimulated, how long users listened to them and which one they have selected. This information may lead authors to understand any correlation between time spent with the VR application and emotive state of users, level of emotional involvement and quality of information remembered, type of actions performed, and type of information remembered.

- C.

- The involvement of users through a gamified perceptive storytelling. It is true that to increase the user’s engagement gaming-like techniques are advisable: choose a goal to be reached within the virtual exploration, such as moving to the next level of the story; unlock some narrative nodes; meet a virtual character like Ariadne in the temple… these cause a strong motivation in the users, who are very effective in focusing and concentrating on completing a task and bringing self-confidence. Such kind of experience in ArkaeVision Archeo should therefore encourage users’ content understanding.

As a methodology, the multi-partitioned analysis was followed—as a proved valid framework for conducting evaluation in the field of technology applied to CH [100]. It is generally made up of three assessment tools used according to a predetermined schedule and a specific operating method. These tools allow to get a more in-depth view of user profiling and experience. For ArkaeVision Archeo only two of these was used, because of the state of-the-art in the development at the moment of the public exposition. The evaluative tools were:

- -

- Observation: it is one of the most used at the beginning of each evaluative activity, although it is not always easy to conduct [101]; it is extremely useful as it provides fertile ground for the first considerations on users and technologies and for constructing the conceptual map for the investigative comparison of the results obtained by direct survey tools. Observations are not used only at the beginning of the evaluation, but also during the user experience.

- -

- Questionnaire: it is essential to probe the basic knowledge of each user to identify the needs and expectations, recognize the attitudes, gestures, movements and comments [102]. The questionnaire is widely used in research and it is built upon the goal to be pursued (type of questions, modulation of sentences, language’s level), and the function it must have in the context of the project to be evaluated (usability test or demographic interest, customer satisfaction or cognitive learning, etc.); users can fill in the questionnaire independently, with a certain margin of expression.

In ArkaeVision Archeo, the UXEs involved therefore two types of research, quantitative and qualitative, different both in the operating methods and for the used tools.

In quantitative research, the reflection on collected information is based on a large number of questionnaires; the percentage calculation of the answers returns a general image of the trends linked to the investigated topic [10,100]. Quantitative research is indeed presented through charts and graphs; it can be used to establish generalizable facts about a topic. In our case study, data collected were:

- -

- Demographics. Age, gender, provenance, educational background, technological alphabetization, profession; preferences on the type of cultural visit (alone or in group; for working reason or with families); preferences on the type of technological device used; time spent with such a device; reasons to visit cultural site; average amount of budget assigned to cultural experiences.

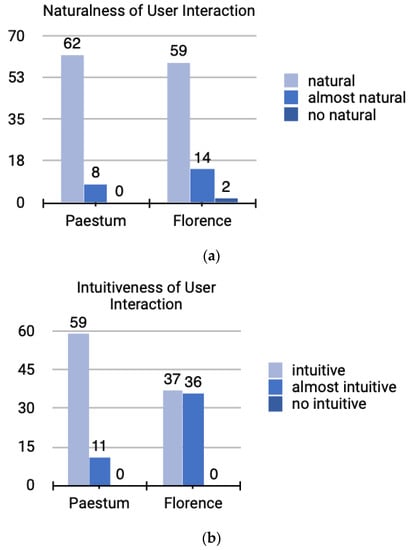

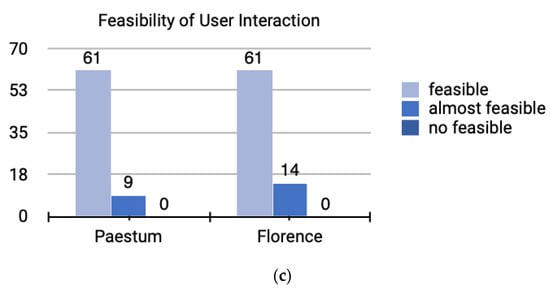

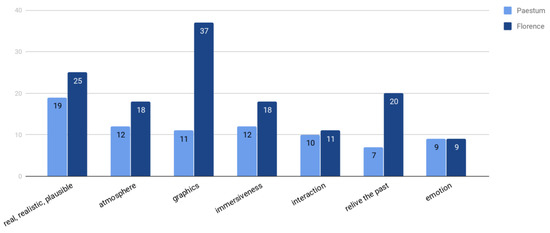

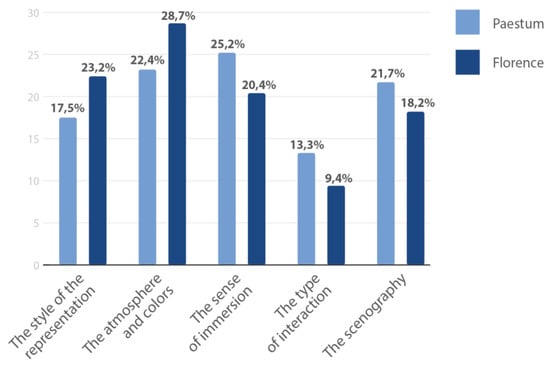

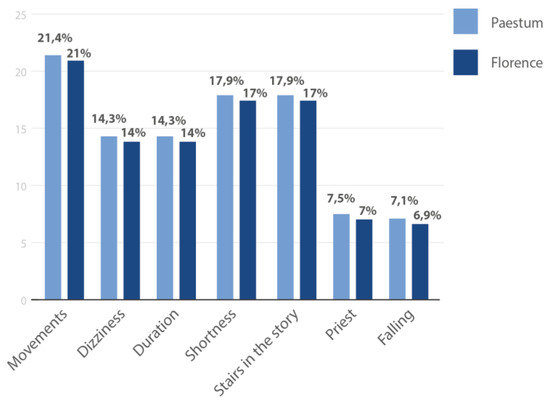

- -