Development of Quality Control Requirements for Improving the Quality of Architectural Design Based on BIM

Abstract

1. Introduction

- The applied design phase was defined by analyzing the work and output information for each stage in the design process.

- Quality check targets were deduced through advanced practices (e.g., guidelines, software) and domestic regulations.

- Quality check requirements consisting of a space check, design check, and construction check were developed by categorizing the subject of the quality control according to the object and purpose of the works. Regulation checking is included in the design check criteria.

- A process of definition and development of element technologies was suggested for applying quality control to architectural design based on BIM. The results of quality checks were validated using rule-based quality checking software.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Overview of BIM-Based Quality Control

- It is difficult to define the information to be delivered to each subsequent stage in the design phase and to utilize the delivered information at the next stage; due to the lack of definition of the work and requirements for each design stage [17].

- The lack of requirements and guidelines related to BIM degrades design quality. Although some BIM guidelines include quality control requirements, there is a lack of detailed requirements for quality control in such guidelines. Further, there are limitations with the guidelines to be adopted in quality control work practices [4,9,20].

2.2. The Status of Guidelines for Quality Control

2.3. The Status of Quality Control Software

2.4. Case Applications of Quality Control

2.5. Summary

3. Design Quality in Design Processes Based on BIM

4. Development of Design Quality Check Criteria Based on BIM

4.1. Review of Quality Check Targets Based on BIM

4.2. Development of Quality Check Criteria Based on BIM

4.2.1. Space Check Criteria

4.2.2. Design Check Criteria

4.2.3. Construction Check Criteria

4.3. Development of Quality Check Checklists

5. Application of Design Quality Checks Based on BIM

5.1. Suggested Quality Checking Process

- (1)

- The architect and designer produce a design plan with quality check criteria using BIM software. In this case, it is necessary to define the building object’s properties according to BIM guidelines for the quality check.

- (2)

- The BIM created using the BIM software is exported in the IFC format [36].

- (3)

- The BIM data are checked according to the quality checking criteria using quality check software. The architect and designer continually revise and review the design until the design requirements are properly reflected in the BIM data through the quality checking criteria.

- (4)

- The quality checking results can be reported.

5.2. BIM Data

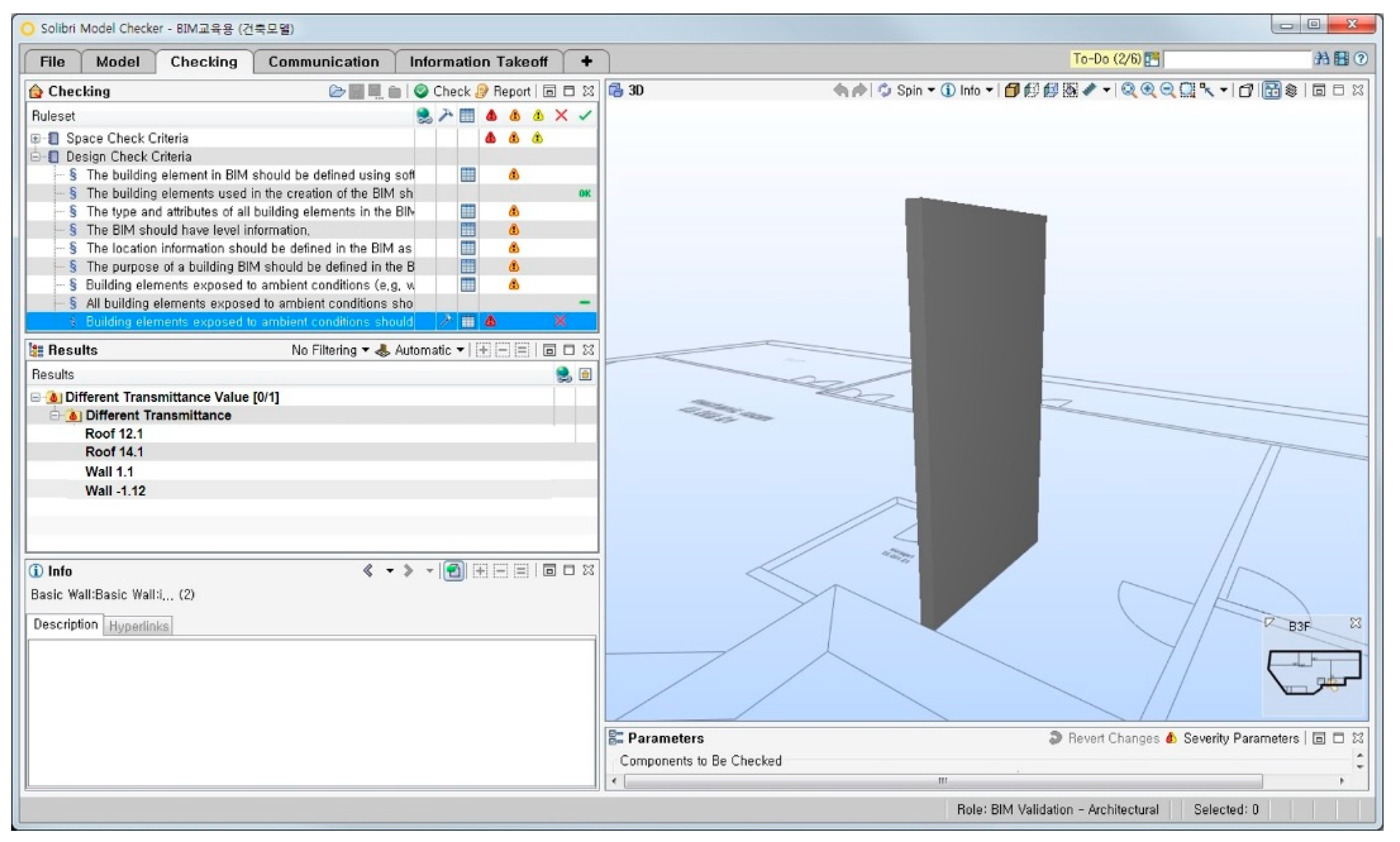

5.3. Application of Rule-Based Quality Checking Software

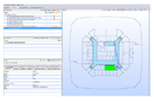

5.3.1. Quality Checking Using SMC (Modification and Addition of Rule Sets)

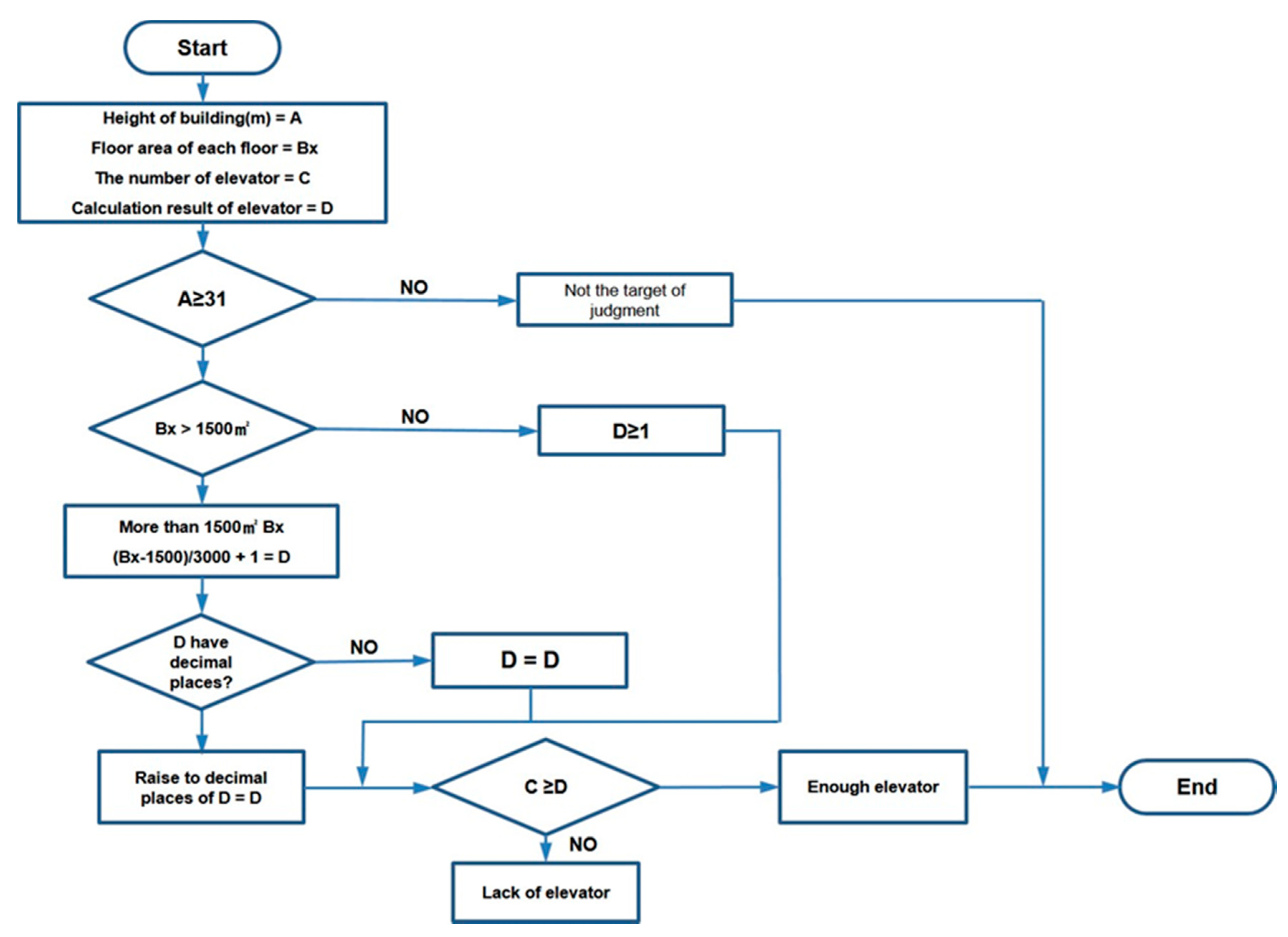

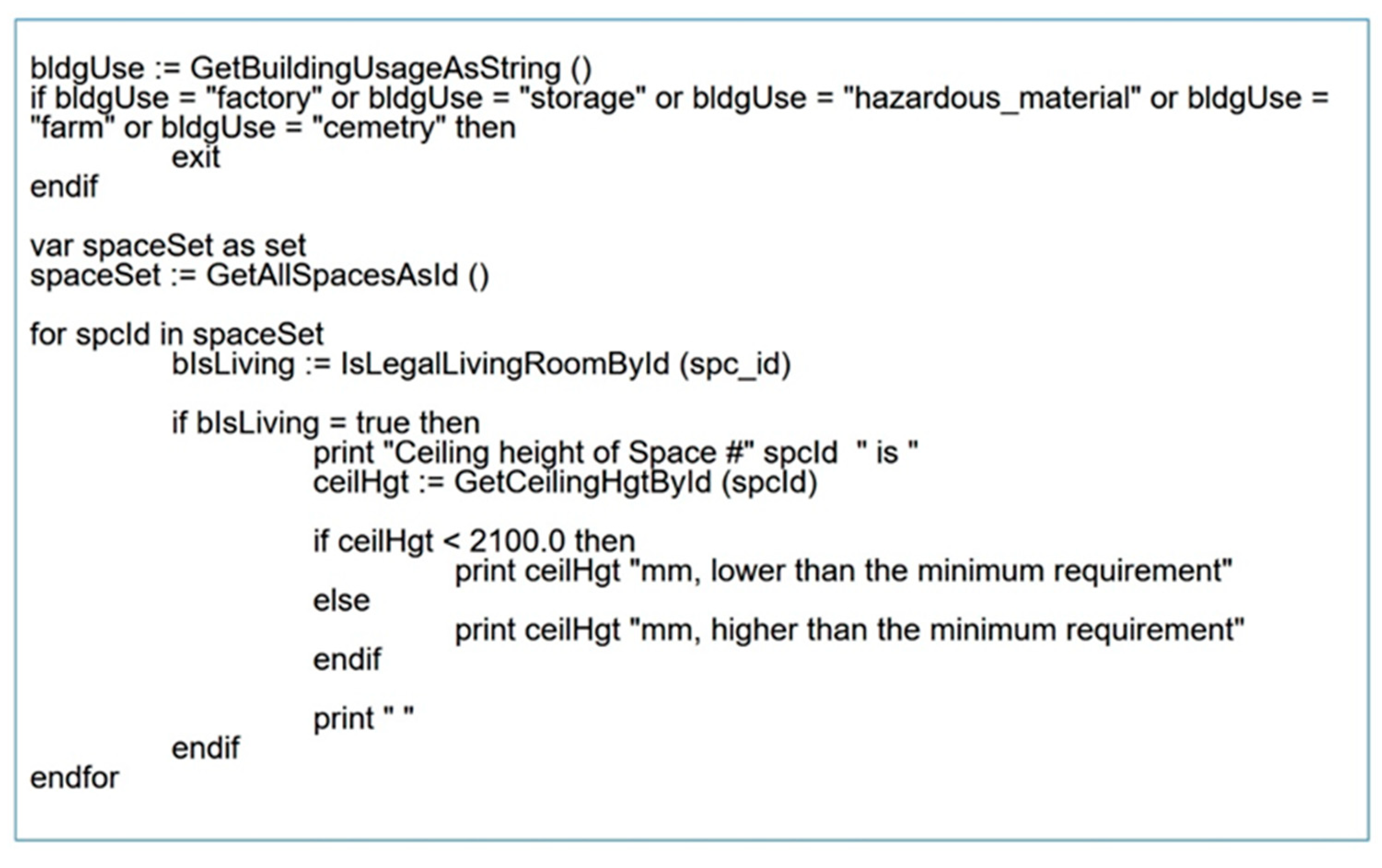

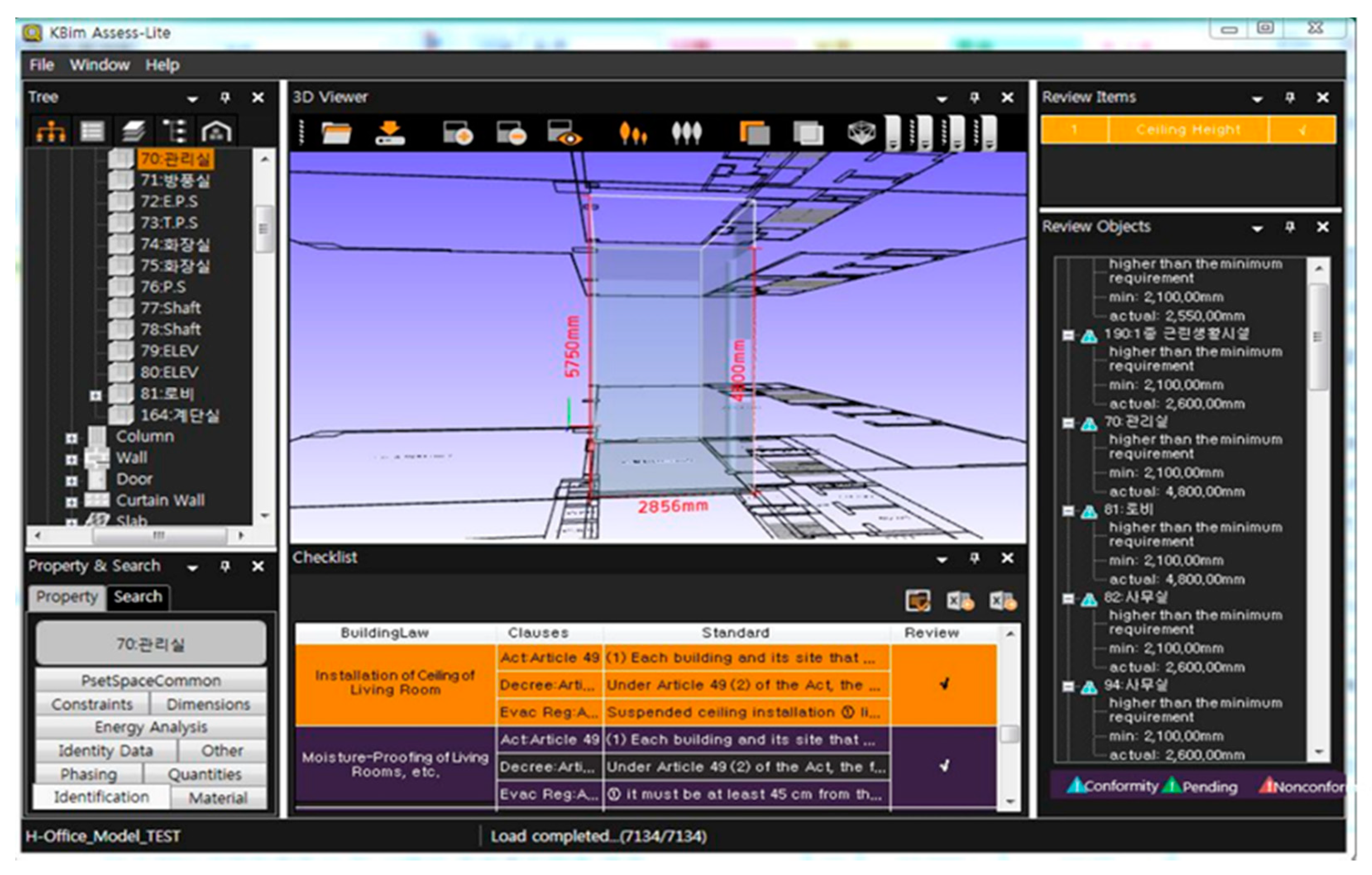

5.3.2. Development of Rule-Based Quality Check Software

- A: Surface area

- ∆T: Temperature difference (T1, T2)

6. Usage and Verification of Proposed Quality Checking Requirements

6.1. Overview

6.2. Results of the Applied Criteria

6.2.1. Space Check Criteria

6.2.2. Design Check Criteria

6.2.3. Construction Check Criteria

6.3. Analysis of the Results and Achievement

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kim, I.; Lee, S. Development of an interoperability model for different construction drawing standards based on ISO 10303 STEP. Autom. Constr. 2005, 14, 633–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eastman, C.; Teicholz, Y.; Sacks, R.; Liston, K. BIM Handbook, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, J.; Choi, J.; Kim, I. Development of BIM-based Evacuation Regulation Checking System for High-rise and Complex Buildings. Autom. Constr. 2014, 46, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J. Open BIM & Design Information Quality Control; Goomi Book: Seoul, Korea, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Luo, H. A BIM-based construction quality management model and its applications. Autom. Constr. 2014, 46, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Kim, I. Development of an Open BIM-based Legality System for Building Administration Permission Services. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2015, 14, 577–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malsane, S.; Matthews, J.; Lockley, S.; Love, P.; Greenwood, D. Development of an object model for automated compliance checking. Autom. Constr. 2015, 49, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, S.; Corry, E.; O’Donnell, J. Requirements for a BIM-Based Life-Cycle Performance Evaluation Framework to Enable Optimum Building Operation. In Proceedings of the 32th CIB W78 Conference 2015, Eindhoven, The Netherlands, 27–29 October 2015; CIB: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, I. Quality Assurance, 7th Buildingsmart Korea Workshop; Kyung Hee University: Yongin-si, Korea, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Eastman, C.; Lee, J.; Jeong, Y.; Lee, J. Automatic rule-based checking of building designs. Autom. Constr. Rev. 2009, 18, 1011–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. Automated Checking of Building Requirements on Circulation Over A Range of Design Phases. Ph.D. Thesis, Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta, GA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Sijie, Z.; Kristiina, S.; Markku, K.; Ilkka, R.; Eastman, C.; Jochen, T. BIM-based fall hazard identification and prevention in construction safety planning. Saf. Sci. 2015, 72, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NIBS. Overview Building Information Models; NIBS: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2006; Available online: https://www.nibs.org/page/nbgo (accessed on 9 October 2019).

- Choi, J.; Kim, H.; Kim, I. Open BIM-based Quantity Take-off System for Schematic Estimation of Building Frame in Early Design Stage. J. Comput. Des. Eng. 2015, 2, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azhar, S.; Nadeem, A.; Mok, J.; Leung, B. Building Information Modeling (BIM): A New Paradigm for Visual Interactive Modeling and Simulation for Construction Projects. In Proceedings of the First International Conference on Construction in Developing Countries (ICCIDC–I), Karachi, Pakistan, 4–5 August 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, J.; Kim, I. Interoperability Tests of IFC Property Information for Open BIM based Quality Assurance. Trans. Soc. CAD/CAM Eng. 2011, 16, 92–103. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, I.; Park, C.; Park, J.; Jung, J.; Choo, S. BIM in Architecture: Design and Engineering; Kimoondang: Seoul, Korea, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T. Integrating Building Code Compliance Checking into a 3D CAD System. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computing in Civil Engineering, Cancun, Mexico, 12–15 July 2005; American Society of Civil Engineers: Reston, VA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassileva, S. An approach of construction integrated client/server framework for operative checking of building code. In Proceedings of the CIB W78 workshop, Reykjavik, Iceland, 28–30 June 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Georgia Tech. Georgia Tech BIM Requirements & Guidelines for Architects, Engineers and Contractors; Version 1.5; Georgia Tech: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kulusjarvi, H. COBIM Common BIM Requirements 2012; Series 6: Quality Assurance; BuildingSMART Finland: Helsinki, Finland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bips. 3D CAD Manual 2006; Bips: Lyngby, Denmark, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- GSA. 3D-4D Building Information Modeling; BIM Guide Series; GSA: Washington, DC, USA, 2007.

- USACE. Building Information Modeling (BIM)—A Road Map for Implementation to Support MILCON Transformation and Civil Works Projects within the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers; USACE: Washington, DC, USA, 2006.

- Statsbygg. Statsbygg Building Information Modelling Manual Version 1.2; Statsbygg: Oslo, Norway, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Land Transport and Maritime Affairs (MLTM). BIM Guide of Ministry of Land Transport and Maritime Affairs; MLTM: Sejong, Korea, 2010.

- Open BIM, BuildingSmart. Available online: http://www.buildingsmart.org/openbim/ (accessed on 31 July 2020).

- KPX. Korea Power Exchange Headquarters Building Construction Design Competition Guideline; KPX: Naju, Korea, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- PPS. BIM Guide of Public Procurement Service v1.3; PPS: Daejeon, Korea, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- CADLearning. Autodesk Navisworks Training & Tutorials; CADLearning: Concord, NH, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, I. Open BIM based Design Guidelines & Design Quality Evaluation in Korea. In BIM Expert Seminar; Kyung Hee University: Yongin-si, Korea, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Building and Construction Authority (BCA). Code on Accessibility in the Built Environment 2013; BCA: Singapore, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- SEUMTER, Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport (MOLIT). Available online: https://cloud.eais.go.kr/ (accessed on 11 September 2020).

- Karjalainen, A. Senate Properties BIM; Senate Properties: Helsinki, Finland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Karlsheoj, J. Digital Construction in Denmark from an Engineering Company’s Point of View; The BIM; SMART KOREA: Seoul, Korea, 2009; pp. 49–52. [Google Scholar]

- IFC. BuildingSmart. Available online: https://www.buildingsmart.org/standards/bsi-standards/industry-foundation-classes/ (accessed on 31 July 2020).

- Napier, B. Wisconsin Leads by Example; Matrix Group Publishing: Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2008; pp. 30–31. [Google Scholar]

- Kvarsvik, K. National Museum at Vestbanen Architect Competition BIM Requirements and Results; PowerPoint PPT Presentation; Kristian Kvarsvik: Oslo, Norway, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- IPD. Available online: https://forums.autodesk.com/t5/revit-architecture-forum/revit-2020-export-to-previous-version-possible/td-p/8820562 (accessed on 31 July 2020).

- KIA. KIA Architectural Design Work Handbook; KIA: Seoul, Korea, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- AIA. Integrated Project Delivery: A Guide; AIA: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Henttinen, T. COBIM Common BIM Requirements 2012 Series 1: General Part; Henttinen: Helsinki, Finland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- CIC Research Group. BIM Project Execution Planning Guide Version 2.0; CIC Research Group: State College, PA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- AIA. AIA BIM Protocol (E202); AIA: Washington, DC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- IAI. IFC 2x Extension Modeling Guide; IAI: Hertfordshire, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- McCune, M. Compliance Checking Using IFC Schema & Solibri. CollectiveBIM. 2015. Available online: https://collectivebim.com/2015/04/20/compliance-checking-using-ifc-schema-solibri/ (accessed on 10 October 2019).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

| Classification | Description |

|---|---|

| Physical information quality |

|

| Logical information quality |

|

| Data quality |

|

| Guidelines | Purpose | Main Content |

|---|---|---|

| Common BIM requirements 2012 (Finland) [21] |

|

|

| 3D CAD manual 2006 (Denmark) [22] |

|

|

| U.S. General Services Administration (GSA) BIM guide series (USA) [23] |

|

|

| US Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) BIM roadmap (USA) [24] |

|

|

| Statsbygg BIM manual (Norway) [25] |

|

|

| BIM application guide in construction sector (Korea) [26] |

|

|

| Design competition guidelines for power exchange headquarters project (Korea) [28] |

|

|

| BIM guidelines for the Public Procurement Service (PPS) (Korea) [29] |

|

|

| Project Name | Overview/Purpose | Development Organization | Quality Control Requirements | Content |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| US GSA BIM-enabled design guide automation [10] |

| GSA, Georgia Tech design computing lab | US courts design guide |

|

| Finland music concert project [34] |

| Senate properties | BIM requirements 2007 |

|

| Denmark Rambøll headquarters [35] |

| Rambøll | 3D CAD manual 2006 |

|

| USA Wisconsin-13 BIM pilot projects [37] |

| Wisconsin State | Wisconsin (BIM) guidelines |

|

| Norway National Museum design competition [38] |

| StatsbyggJotne EPM technology | Statsbygg General Guidelines for Building Information Modeling v1.1 |

|

| Power Exchange headquarters building construction design competition [28] |

| Korea Power Exchange | Power Exchange headquarters building construction design competition guidelines |

|

| Singapore iGrant [32] |

| BCA | Code on accessibility in the built environment 2013 |

|

| Case | Korea KIA (Architecture Design Work Procedures) [40] | US AIA (IPD) [39,41] | Finland Senate Properties (BIM Requirements) [42] | USA CIC (BIM Project Execution Planning Guide) [43] | Quality Control Targets | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IPD Stage [39] | ||||||

| Conceptualization (expanded programming) |

|

|

|

|

| |

| Criteria design (expanded schematic design) |

|

|

|

|

| |

| Detailed design (expanded design development) |

|

|

|

| ||

| Implementation documents (construction documents) |

|

|

| |||

| Classification | Targets |

|---|---|

| Physical information quality | Windows and doors fixed at the opening |

| Required interval between objects | |

| Clash, structure, MEP elements | |

| Cross-check between equal elements (architecture/architecture, structure/structure, service/service) | |

| Cross-check among other elements (architecture/architecture, structure/structure, service/service) | |

| Connections between space and componentsPosition of the components | |

| Headroom height | |

| Absence of space or object | |

| Incorrectly modelled component | |

| Logical information quality | Evacuation facilities |

| Building coverage ratio, floor area ratio | |

| Height restrictions | |

| Elevator installation | |

| Prevention of heat loss | |

| Regulation of space area | |

| Parking lot installation | |

| Exit route planning | |

| Structural standards | |

| Ceiling installation | |

| Manoeuvring spaces | |

| Data quality | The required property, depending on the level of detail |

| Space name, group name | |

| Type of space and each component | |

| Skin property (wall, slab, door, window) | |

| Height of space | |

| Whether spatial area matches with space program | |

| Whether each floor space area matches with total area | |

| Definition of spatial location | |

| Review all space groups (spatial groups), including the type | |

| Space number | |

| Obstruction checking of space consisting of external wall | |

| Door, window, slab area calculation | |

| Total area checking | |

| The properties of accessible |

| Classification | Checking target | Cases | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Space check criteria | Space component area and quantity check |  |

|

| Space number and name check |  |

| |

| Design check criteria | The absence of the component type in the BIM data |  |

|

| Building envelope/Thermal transmittance property check |  |

| |

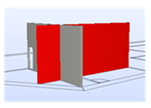

| Exit route check |  |

| |

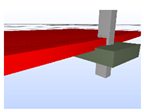

| Construction check criteria | Clash check (different kinds of objects) |  |

|

| Overlap check (same kinds of objects) |  |

|

| Date/Time: | |

| Reviewer: | |

| Project name: | |

| Checklist for design check criteria | Check content (suitability/incongruity/pending) |

| Design quality basic (common) contents | |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| KPX headquarters competition contents | |

| |

| |

| |

| Heat loss prevention criteria | |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| ... | |

| Signature: |

| Image | Description | |

|---|---|---|

| Case 1 |  |

|

| Case 2 |  |

|

| Case 3 |  |

|

| Case 4 |  |

|

| Space Check Criteria Checklist | Error | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Case 4 | |

| Space objects, which are located in all planned space, should be defined. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Space objects should be defined using non-duplicated space number (facility number) as the attribute, according to the list in the space program. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Space objects should be defined using non-duplicated space name as the attribute, according to the list in the space program. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| The BIM should consider space objects, which are defined in the space program. | 22 | 1 | 19 | 0 |

| Space objects should be categorized into zones according to the purpose of the space. | 21 | 29 | 34 | 21 |

| The total area of floor space objects on each floor of the building should be within the error range specified in the spatial plan for the planning area | 0 | 23 | 22 | 0 |

| The quantity of floor space objects on each floor of the building should be in accordance with the number of objects specified in the spatial plan | 10 | 72 | 5 | 3 |

| The area of spatial objects should be within the error range specified in the spatial plan for the planning area. | 24 | 2 | 59 | 0 |

| The quantity of spatial objects should be in accordance with the number of objects specified in the spatial plan. | 73 | 4 | 2 | 0 |

| Spatial objects with minimum height conditions defined in the spatial plan must meet the corresponding condition. | 5 | 8 | 6 | 5 |

| Space objects should not interfere with each other. | 135 | 287 | 202 | 19 |

| Section | Problems and Solutions | |

|---|---|---|

| User input error |

| |

| System error | Error in planning space program (Excel-based program) |

|

| Error in quality check on SMC |

| |

| Error of quality check criteria |

| |

| Design Check Criteria Checklist | Error | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Case 4 | |

| The building element in BIM should be defined using software during the initial creation (e.g., a wall should be created using the wall tool). | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| The building elements used in the creation of the BIM should be constructed. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| The type and attributes of all building elements in the BIM should be defined. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| The BIM should have level information. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| The location information should be defined in the BIM as a value of the property. | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| The purpose of a building BIM should be defined in the BIM as a value of the property. | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Building elements exposed to ambient conditions (e.g., wall, slab) should have property information about the envelope. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| All building elements exposed to ambient conditions should have thermal transmittance as a value of the property. | 15 | 20 | 26 | 24 |

| Building elements exposed to ambient conditions should have thermal transmittance according to legal criteria. | 15 | 16 | 23 | 6 |

| Section | Problems and Solutions | |

|---|---|---|

| User input error |

| |

| System error | Error of BIM software (IFC export/import) [36] |

|

| Error of quality check in SMC | - | |

| Error in quality check criteria |

| |

| Construction Check Criteria Checklist | Error | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Case 4 | |

| There should be no clash or interference between the building elements in the BIM. | 753 | 20 | 42 | 16 |

| There should be no interference between the same building elements in the BIM. | 395 | 23 | 2 | 11 |

| There is no duplicated preparation of building elements in the BIM. | 17 | 13 | 8 | 20 |

| The upper and lower elements of the building should be drawn as encountered. | 111 | 26 | 30 | 7 |

| Section | Problems and Solutions | |

|---|---|---|

| User input error |

| |

| System error | Errors in BIM software (IFC export/import) [36] |

|

| Errors in quality checks in SMC |

| |

| Error in quality check criteria |

| |

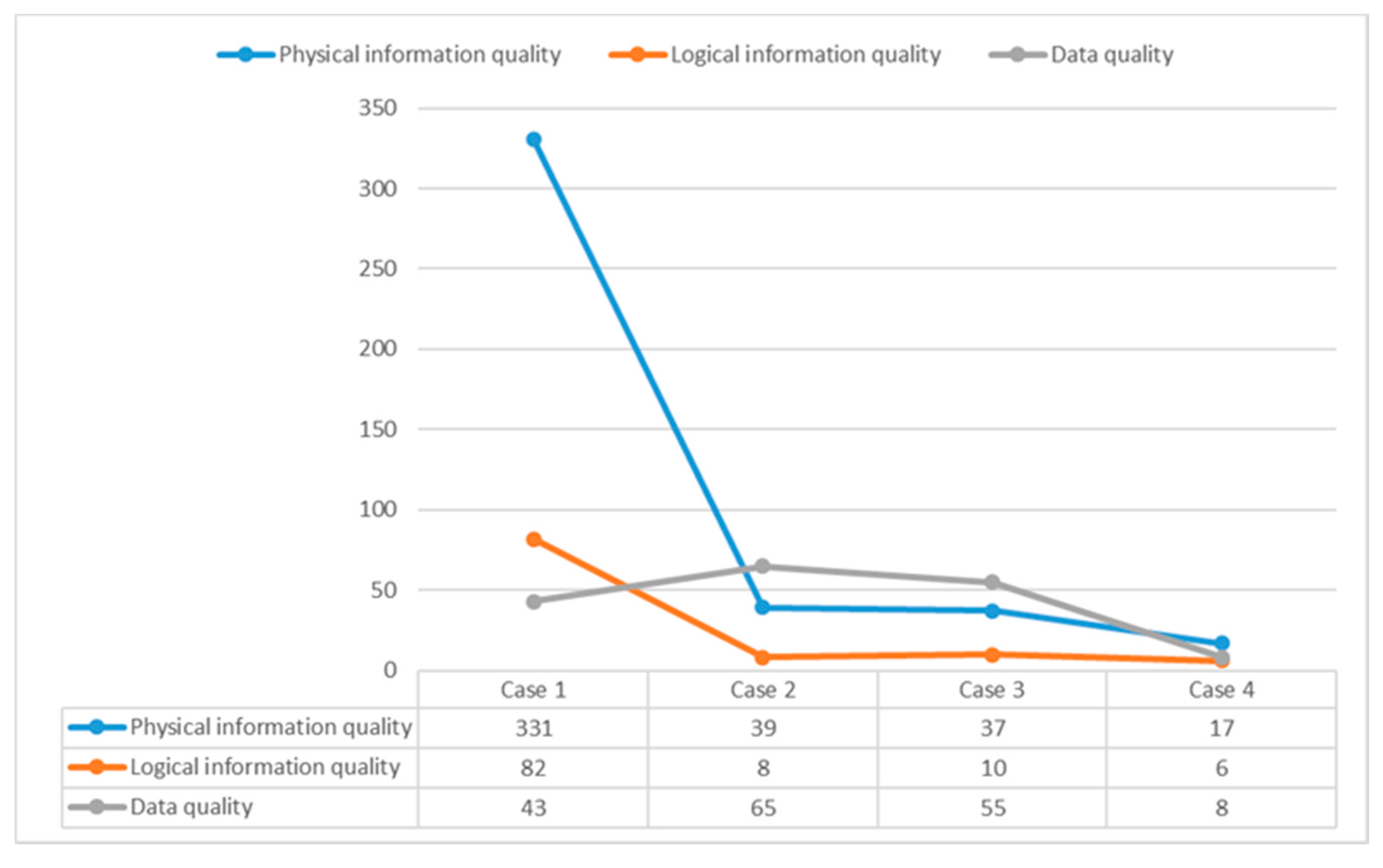

| Criteria | Space Check | Design Check | Construction Check |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reflectivity (%) | 30 | 30 | 40 |

| Quality Check target | Physical information quality Data quality | Physical information quality Logical information quality Data quality | Physical information quality Logical information quality |

| Average value | 26 | 3 | 319 |

| Expected average value | 50 | 50 | 80 |

| Quality Check Target | Space Check | Design Check | Construction Check | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical information quality | 10 | 2 | 319 | 331 |

| Logical information quality | 0 | 2 | 80 | 82 |

| Data quality | 42 | 2 | 0 | 43 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Choi, J.; Lee, S.; Kim, I. Development of Quality Control Requirements for Improving the Quality of Architectural Design Based on BIM. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 7074. https://doi.org/10.3390/app10207074

Choi J, Lee S, Kim I. Development of Quality Control Requirements for Improving the Quality of Architectural Design Based on BIM. Applied Sciences. 2020; 10(20):7074. https://doi.org/10.3390/app10207074

Chicago/Turabian StyleChoi, Jungsik, Sejin Lee, and Inhan Kim. 2020. "Development of Quality Control Requirements for Improving the Quality of Architectural Design Based on BIM" Applied Sciences 10, no. 20: 7074. https://doi.org/10.3390/app10207074

APA StyleChoi, J., Lee, S., & Kim, I. (2020). Development of Quality Control Requirements for Improving the Quality of Architectural Design Based on BIM. Applied Sciences, 10(20), 7074. https://doi.org/10.3390/app10207074