Abstract

The most recent developments of Fused Deposition Modelling (FDM) techniques are moving the application of Additive Manufacturing (AM) technologies toward new areas of investigation such as the biomedical, aerospace, and marine engineering in addition to the more consolidated industrial and civil fields. Some specific characteristics are required for the components designed for peculiar applications, such as complex geometries, lightweight, and high strength as well as breathability and aesthetic appearance specifically in the biomedical field. All these design specifications could be potentially satisfied by manufacturing with 3D printing techniques. Moreover, the development of purpose-dedicated filaments can be considered a key factor to successfully meet all the requirements. In this paper, fabrication and applications of five new thermoplastic materials with fillers are described and analyzed. They are organic bio-plastic compounds made of polylactic acid (PLA) and organic by-products. The growing interest in these new composite materials reinforced with organic by-products is due to the reduction of production management costs and their low environmental impact. In this study, the production workflow has been set up and described in detail. The main properties of these new thermoplastic materials have been analyzed with a major emphasis on strength, lightweight, and surface finish. The analysis showed that these materials can be particularly suitable for biomedical applications. Therefore, two different biomedical devices were selected and relative prototypes were manufactured with one of the analyzed thermoplastic materials. The feasibility, benefits, and performance of the thermoplastic material considered for these applications were successfully assessed.

1. Introduction

Chemurgy was discussed for the first time in the 1930s in the United States. As is known, it is a branch of industry and applied chemistry that studies the integration of agricultural and natural biomasses (renewable resources), given as input to the secondary industry for the production of fuels, chemical compounds, or materials [1]. It is worth mentioning that this “industrial symbiosis” model involves the integration of specific properties of selected biologic materials to eliminate the use of petrochemical modifying agents, which leads to the creation of plastic materials with improved ecological properties. The environmental benefit of this production paradigm is confirmed by its adherence to some of the principles set out in the ‘European strategy for plastic in the circular economy’ (European Commission, 2018) [2,3]. The biomass fillers do not only allow us to completely replace the toxic additives, but they are also able to improve materials performance. In fact, while additives are usually added in small percentage parts, biomasses are added in much higher percentages, ranging from 15% to 60%, which leads to significant savings of the plastic material. In this way, two objectives are embraced simultaneously: the reduction of dangerous substances in materials and raw materials replacing them with wastes from production cycles (this allows us to meet the waste framework directive [4] ‘reuse before recycling’ indications).

With reference to the first objective, the environmental impact of plastics, at various levels, is well-known [5]. One of the worst effects is produced by the microplastics. These are plastic particles ranging between 5 and 330 μm and, due to their size, can reach any terrestrial environment. Recent studies have demonstrated that they can travel hundreds of kilometers, carried by the wind, clouds and rain [6]. They can even reach living organisms so that a human could assume up to 5 g (the equivalent of a credit card) per week in the worst perspective (UN News, 2017). The impact caused by microplastics is mostly attributable directly to the additives contained within them. In fact, the small plastic particles act as a simple vector while additives release their toxicity to the environment where microplastics deposit and accumulate [7,8]. The secondary microplastics differ from the primary ones for the size in which they are directly produced. This is the case of plastic particles used in cosmetic products or those making up fibers for clothes. They separate from plastic objects consequently to mechanical, thermal, or chemical deterioration.

After this premise, it can be said that the new paradigm exposed so far could be an excellent preventive solution to the secondary microplastics since the additives-core problem due to their intrinsic toxicity-are replaced by a completely non-toxic and biodegradable material.

The paradigm of circular economy is generally applicable to manufactured parts including multi material components [9] and parts obtained by means of Additive Manufacturing (AM) [10], which can be implemented in different manufacturing processes [11].

In this work, five new organic bio-composite filaments, HEMP, WEED, TOMATO, CAROB, and PRUNED made of polylactic acid (PLA) filled with organic by-products [12] are described along with two examples of application to the biomedical field by using Additive Manufacturing. The five bio-plastic compounds have different physical, mechanical, and visual properties. They are all obtained by recycling wastes from the processing of five different agricultural supply chains (by-products). Each natural agricultural additive has different mechanical/physical properties such as tensile strength, elasticity, density, and porosity (which is linked to the breathability) as well as a strong visual and tactile identity. These new ‘eco’ plastics are completely biodegradable and biocompatible, which makes them more suitable for the products’ manufacturing in sectors such as biomedical, food, pharmaceutical, and cosmetics. In the biomedical field, these materials are particularly recommended for the realization of objects intended to come into contact with the human body, such as orthoses. Most of these applications constitute for the authors the reason for using bio-plastic compounds in the form of filaments, suitable for AM, since this manufacturing method allows great versatility in design and efficiency if an appropriate design framework is provided [13]. For instance, devices like orthoses require a patient-specific approach where the customization undoubtedly gives an added value: the preoperative planning more often is finalized to the realization of 3D-printed models [14], patient-specific instruments [15], customized orthopaedic devices [16], and customized dental implant systems [17]. In all these applications, AM has also the advantage of one single customized item being produced at affordable prices. Always with reference to the biomedical field, and particularly to scaffolds for tissue engineering [18], which have a highlight of interest, AM enables the production of complex geometries, which were previously difficult or impossible to be manufactured [19]. The reported biomedical applications have a purpose to outline the versatility of the manufacturing method.

The product derived from these new organic bio-plastic compounds bears some main advantages over classical competitors due to limited management and production costs, reduced environmental impact, recyclability, and optimized disposal. However, all these advantages are not achieved at the expense of performance. On the contrary, as outlined in the present paper, performance can get even better with respect to standard thermoplastic materials, thanks to improved mechanical properties and weight reduction coming from the specific filler being used. On the whole, the secondary sectors, such as thermoplastic industries, take advantage of new inputs from agricultural wastes with the added value of complying with European standards that require 20% bio-based inputs [4].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bio-Plastic Compounds Fabrication

The new bio-plastic compounds can be essentially defined as composite materials. These can be described as materials constituted by two or more different phases with a distinct interface: (i) the matrix or continuous phase and (ii) the filler/reinforcement phase, surrounded by matrix material [20,21]. Although preserving the individual phases for their own features in the final product, when combined, the resulting composite material displays enhanced mechanical/physical characteristics when compared to pristine components [22,23]. Composite materials can show remarkable anisotropy, according to fibres’ arrangement, namely, their properties change considerably in different directions, but also nearly isotropic configurations can be obtained [24]. Generally, in artificial and industrial uses, the matrix phase is based on synthetic thermosetting or thermoplastic polymers, depending on manufacturing processes and final technological applications. On the other hand, the filler phase can be based on inorganic fibers or particulates (e.g., glass, carbon, etc.) in order to ensure strength and stiffness to the resulting composite material [22].

When compared to common composite materials, these compounds are entirely natural-based. The matrix consists of Polylactic Acid (PLA), a 100% bio-based plastics (purchased from Ingeo Biopolymer 3D450 by NatureWorks), and the reinforcements are based on different particles (more than 20% in weight) from agricultural waste, which makes these products into particulate bio-composite materials.

In particular, the by-product particles used as filler have been standardized, by controlling the respective humidity values, spherical shape, and caliber, as illustrated in Table 1.

Table 1.

Main characteristics of the particles used as a filler phase from agricultural waste.

The different filaments are made with fillers, which are randomly dispersed in a PLA matrix. Thus, they can be considered as composites with short fibres (such as short fiber thermoplastics, which are well-known) that can be treated as nearly isotropic. This assumption is also enforced by the shape of the fillers, which was characterized by an adimensional parameter of sphericity. It was found that this parameter ranged between 0.8 and 1.2, where the value 1 corresponds to a perfect sphere. Sphericity also promotes the homogeneity of the material since it improves the adhesion between the filler and the matrix minimizing the presence of micro-voids, which could produce microcracks and internal stresses.

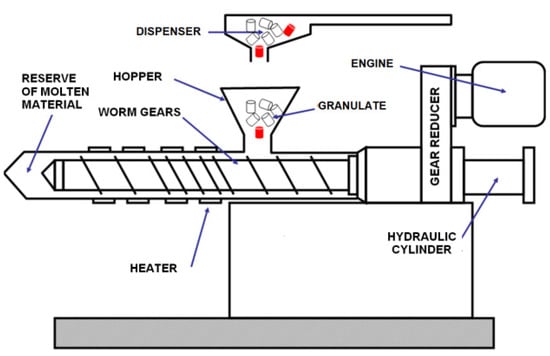

The production process begins with the selection of industrial plant by-products, which are selected for their particle size and chemical properties. In detail, the standardized particles, illustrated in Table 1, are joined to the thermoplastic PLA matrix in a two-screw extruder (Figure 1) while acting as a mixer/compounder in the temperature range of the PLA melting point. Moreover, before being inserted into the hopper, the organic by-products are pretreated by means of a micronizer and a dehumidifier in order to maximize the compatibility between the matrix and the filler. The injection parameters used by the two-screw extruder are shown in Table 2. The final product is a biodegradable thermoplastic polymer. Upon leaving the mixer/compounder, the compound is placed in a granulator for the production of granules or in an extruder in order to produce filaments for 3D-printing.

Figure 1.

Workflow to produce bio-composites particulate based on polylactic acid (PLA) and natural waste.

Table 2.

Injection parameters.

The five different bio-plastic compounds filaments, obtained by varying the organic by-product fillers used, are:

(1) HEMP (Figure 2a): filament of natural and compostable origin containing hemp (ranging from 15% to 25%).

Figure 2.

Thermoplastic bio-composite filaments: (a) HEMP, (b) WEED, (c) TOMATO, (d) CAROB, and (e) PRUNED.

(2) WEED (Figure 2b): filament of natural and compostable origin, containing waste powder from hemp leaf (ranging from 10% to 15%).

(3) TOMATO (Figure 2c): filament of natural and compostable origin containing scraps from the agricultural production of Sicilian cherry tomatoes (ranging from 15% to 25%).

(4) CAROB (Figure 2d): filament of natural and compostable origin, containing discarded carob flour (ranging from 10% to 20%). Carob flour is a product that contains more than 30% of sugars.

(5) PRUNED (Figure 2e): filament of natural origin, compostable, containing exclusively orange pruning waste (ranging from 10% to 20%). This waste is mainly composed of orange wood sawdust with a good percentage of fruit peel waste.

It is worth noting that the bio-plastic compound filaments illustrated in Figure 2a–e are at a prototypal stage, excluding the HEMP filament, which has been patented. Therefore, the respective characterization is still ongoing and liable to further investigations. The diameter of the produced filaments described here is 1.75 mm.

2.2. Performance Evaluation

The following properties have been considered and tested on the new bio-plastic compound filaments.

- Manufacturing capability: this property was evaluated considering melting temperatures, filament surface roughness, density, and retraction behaviour, considered as longitudinal moulding shrinkage. In all the bio-composite materials, the melting temperature was evaluated by Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC), according to standard ISO 11357. The density was estimated at 23 °C, according to standard ISO 1183. The longitudinal moulding shrinkage was measured at 23 °C, according to standard ASTM D 995.

- Roughness: the average value of this characteristic was measured for an object printed with these new bio-composite materials and compared it with that of an object printed with pristine PLA and with Acrilonitrile-butadiene-stirene (ABS).

- Mechanical properties: the elastic modulus, the yield strength, the yield elongation, the ultimate stress, and the ultimate elongation were evaluated. The elastic modulus was evaluated at 23 °C by using a dynamic mechanical analyzer (DMA Q800, TA Instruments), according to standard ISO 527. The yield and elongation strength together with the ultimate stress and elongation were estimated by a static mechanical machine (Instron 5569), setting a displacement rate equal to 10 mm/min. All mechanical properties were tested at 23 °C, according to standard ISO 527.

All experimental tests were carried out at SUPERLAB S.r.l. Salvaterra (Italy). Further details on the equipment used for characterization can be found in Reference [24].

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Manufacturing Capability

Bio-plastic compound filaments are as printable as PLA since they can be extruded at even lower temperatures. Extruding at up to about −13% temperatures implies significant energy savings. In addition, filled PLA has generally shown a shrinkage, which makes printing more accurate, without the need for further processing being necessary [25,26]. Table 3 summarizes the main manufacturing capability properties of the new bio-plastic compound filaments.

Table 3.

Main manufacturing capability of new bio-plastic compounds in comparison with pristine polylactic acid (PLA) filament.

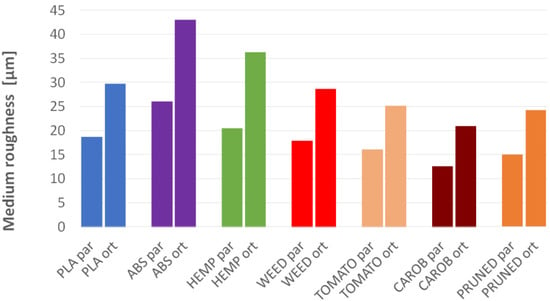

3.2. Roughness

Using a “NANOVEA” Optical Profilometer mod. PS50 (Sensibility 2 µm, height range 25 mm, sampling length 2.5 mm, measuring speed of 0.5 mm/s), experimental measurements were carried out to evaluate average roughness (Ra) of Bio-plastic compounds. The average roughness of Bio-plastic compounds was evaluated in flat surfaces (without taking into account “staircase” or “stair-stepping” problems) printed parallel (par) to the printing area while printed orthogonal (ort) to the printing area in flat surfaces. The printing parameters used are shown in Table 4. Bio-plastic compounds result in a better surface finishing compared to both ABS and PLA (Figure 3).

Table 4.

Printing parameters.

Figure 3.

Ra of new composites in comparison with pristine polylactic acid (PLA) and acrilonitrile-butadiene-stirene (ABS).

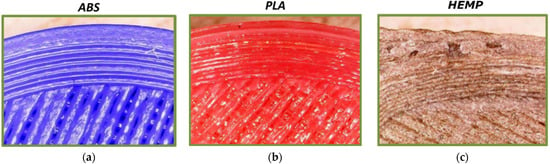

HEMP bio-plastic compounds was the roughest of the “new materials” with a value very close to that of pristine PLA. The others Bio-plastic compounds have better finishes than both the Acrilonitrile-butadiene-stirene (ABS), and Polylactic acid (PLA) (Figure 4). Differently, the CAROB has a better finishing value.

Figure 4.

Surface finish compared to traditional materials: (a) Acrilonitrile-butadiene-stirene—ABS, (b) Polylactic acid—PLA, and (c) Polylactic acid filled with 20% hemp—HEMP.

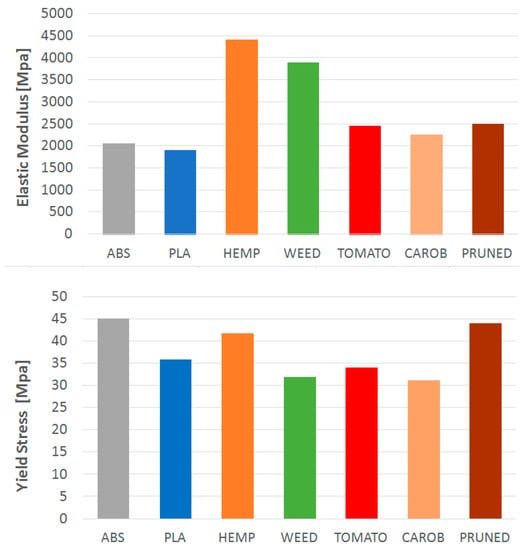

3.3. Mechanical Properties

Each filler produces some specific benefits from the point-of-view of the mechanical properties. The measurements of the mechanical properties (Table 5 and Figure 5) were carried out, as reported in Section 2.2, using the printing parameters reported in Table 4.

Table 5.

Main mechanical properties of new composites in comparison with acrilonitrile-butadiene-stirene (ABS) and pristine polylactic acid (PLA).

Figure 5.

Elastic modulus (up) and Yield stress (down) for PLA and filled materials.

Moreover, in Table 5, we also report the main mechanical properties of ABS, which constitutes a traditional synthetic polymer commonly used for Fused Deposition Modelling (FDM) 3D-printing [27,28] in comparison with bio-based ones, such as PLA and our composite materials.

More details on the results are given in the following.

- HEMP (Hempt fillers 20%): this material has excellent tensile strength, thanks to the high presence of silicon contained in the hemp shives. This is a result not obtainable even with hemp fiber or wood sawdust. The elastic modulus is more than double if compared to ABS (+115%) and PLA (+133%). Moreover, the yield strength remains almost constant in comparison with ABS, but it increases significantly when compared to PLA (+16%) (see Figure 5).

- WEED (Powder from hemp leaf fillers 20%): again, it results in a relevant increment of the elastic modulus. However, both yield stress and ultimate stress are smaller than ABS and PLA. In addition, this material undergoes a very high plastic deformation. This is due to cannabinoids, which give much plasticity to the material. The starting ABS or PLA have a percentage of elongation at break equal to about 3% [25]. Adding 20% of hemp leaf powder, this percentage reaches about 9%.

- TOMATO (Cherry tomatoes fillers 20%): the performances in terms of ultimate stress and ultimate elongation are very similar to pristine PLA and ABS. However, the TOMATO elastic modulus is about +20% higher than ABS and PLA. Moreover, ABS shows a higher yield stress (about +30%) compared to the TOMATO composite.

- CAROB (Carob flour fillers 20%): due to the high temperatures of the die, contained sugar becomes caramel, which gives the final material a noticeable elongation approaching the yield point. In fact, although most of its mechanical properties are similar to ABS and PLA, CAROB has a percentage of elongation at break which reaches more than a 20% value due to the addition of carob flour.

- PRUNED (Orange pruning fillers 20%): material has shown excellent resistance to plastic deformation and failure compared to PLA (+25% and +42%, respectively) while the elastic modulus is similar. In this case, its mechanical properties are very comparable to ABS with the exception of yield elongation that is closer to PLA values.

With reference to the visual/outer appearance, each filler produces peculiar characteristics.

- HEMP: filler gives excellent surface touch properties, breathability, and wood effect (Figure 4c).

- WEED: this material has a characteristic natural green colour, which makes it very suitable for the production of domestic objects.

- TOMATO filler gives a vivid red colour.

- CAROB filler gives a characteristic reddish/brownish colour and a shiny appearance.

- PRUNED: this material has a characteristic brownish colour.

4. Applications to Biomedical Devices

Antibacterial properties of hemp shives [29] with the breathability, good aesthetics characteristics, stiffness, and touch pleasant made HEMP bio-plastic compound material the most appropriate material for the design of biomedical prototypes. According to these findings, two different biomedical prototypes, which includes a neck orthosis and a laryngoscope, were manufactured using Printer D300 Technology® equipped with a 0.6-mm nozzle. These two devices were considered to be particularly suitable for highlighting the characteristics of the HEMP material, including specifications of lightness, breathability, good aesthetics, and stiffness. In addition, these are objects large enough to significantly benefit from the shrinkage of the HEMP bio-plastic compound. The printing parameters used to manufacture these prototypes are those shown in Table 4. Both applications have highlighted how the process parameters are the most important issues for the final characteristics of a manufactured part [30,31].

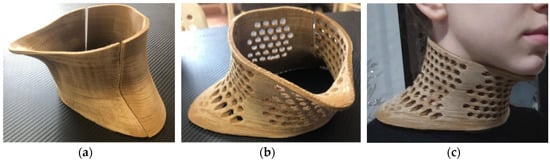

4.1. Neck Orthosis

A neck orthosis is an external medical device that has to support, prevent deformity, or correct the spine. It is used in treating specific pathologies. Rigid cervical collars available on the market are generally made of hard polyethylene covered by a soft pad. However, it is known that the use of these collars can be uncomfortable, restrictive, and poorly tolerated. Customization of the device together with appropriate material selection and geometry, realizable by 3D-printing usage, can help improve the performance of these devices mainly in terms of comfort.

The customized orthosis was designed starting from the Computer Tomography (CT) scan of the neck of a volunteer subject. The final prototype was designed by introducing a pattern of voids in order to improve the breathability and decrease the overall weight.

As a first step, a void-free neck collar was manufactured in order to assess the feasibility to reproduce the complex geometry of the model (Figure 6a). In a later step, a honeycomb pattern of voids was designed and a lighter collar was manufactured (Figure 6b,c). More details on the design of the model are available in Reference [16].

Figure 6.

3D-printed neck orthosis with Hemp filament: (a) full model and (b) (c) model with a pattern of voids.

The accuracy obtained for this model depends on the value of layer height. Excellent accuracy values (≤0.1 mm) are obtained with a layer height of ≤0.25 mm. The superficial roughness values are related to the orientation of the orthosis with respect to the print bed. The best internal and external surface finish was obtained by printing the orthosis parallel to the printing bed. Lastly, the presence of numerous holes that guarantee the necessary breathability prevents the adoption of infill ratios higher than 50%.

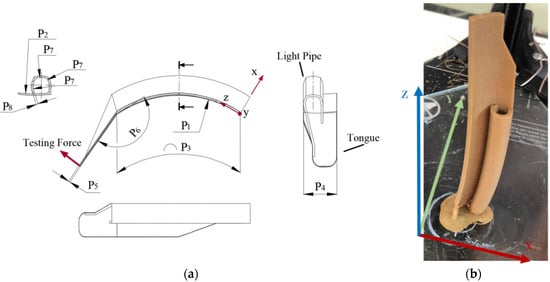

4.2. Laryngoscope

Laryngoscope is used as a diagnostic device for throat inspection or as an aid to intubation. Laryngoscope’s blades can be made of metal (stainless steel) or plastic (high impact grade ABS) material. Plastic blades represent a cost-effective alternative to reusable and single-use metal blades. These advantages, along with design flexibility of AM techniques, make the analysis of suitable materials for plastic laryngoscopes application much more important.

In particular, its blade must be geometrically compatible with patient’s anatomy to provide a good view to doctors with minimal discomfort to patients. For this reason, when laryngoscope blades are designed in the parametric way and are produced with materials that may be pleasant to the touch, the advantage is remarkable. The customizable blade model was developed by following a feature-based approach with eight morphological parameters (Figure 7a). The thickness of such a blade was determined through numerical simulations of ISO (International Organization for Standardization) certification tests. The model was built from the chosen parameters. The blade was tested in silico. Lastly, the blade was produced with Hemp bio-plastic compounds.

Figure 7.

(a) Geometric blade parametrization. (b) Laryngoscope manufactured with Hemp filament.

In this case, as in neck orthosis, the best orientation of the object, in order to obtain the best accuracy, was parallel to the printing bed (Figure 7b). The authors employed a layer height of 0.25 mm, which varied the filling density and speed of deposition by discovering that the surface roughness ranged between 2.46 µm and 22.48 µm. It is necessary to use infill ratios higher than 50% to guarantee the necessary stiffness and breathability.

5. Conclusions

In this work, innovative organic bio-plastic materials for additive manufacturing applications have been analyzed. The organic nature of these materials represents a unique opportunity for moving the production of 3D-printed devices to obtain lower production costs and environmental impact. Mechanical and manufacturing properties have been analyzed and compared with those of classical PLA and higher or comparable performances have been pointed out. Moreover, the paper demonstrates the advantages related to the use of these materials for meeting strict requirements on final products coming from final consumers through their application to two biomedical devices. Two prototypes of a neck orthosis and a laryngoscope have been designed and printed with the HEMP material. Additionally, specifications of lightness, breathability, good aesthetics, and stiffness have been evaluated.

The paradigm described in this case represents a unique opportunity of symbiosis between the primary and secondary industries. The integration between resorbable PLA and agricultural wastes is somehow trivial or innate, when considering the similitude from the physical and chemical points-of-views. Not only is the final product an appropriate answer to the necessity of reducing and minimizing additive toxicity, but it can also have better manufacturing capability, superior mechanical properties, and added benefits. Future research will be devoted to the analysis of other fillers, setting up models able to foresee the respective performances in terms of manufacturing capability, visual/outer appearance, and mechanical properties.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.C.; Data curation, M.C., G.P., M.G., G.M. and R.A.; Formal analysis, G.M. and R.A.; Investigation, M.C., G.M. and R.A.; Methodology, M.C.; Visualization, G.P.; Writing—original draft, M.C., G.P., R.A. and M.G.; Technological process, M.C. and G.M.; Experimental tests, M.C. and G.M.; Neck collar design, R.A. and M.C.; Laryngoscope design. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The fund for the athenaeum research in Catania, research programme 2019/2021, supported this research.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the following companies: Agricultural farms (Molino Crisafulli, Boniser, South Hemp Tecno), which have provided their production wastes, Tecco Spa for biomass standardization, Lati Spa for compound production, Filoalfa for 3D filament production, and Dott. Carlo Canalini and staff of Superlab S.r.l. Salvaterra (Italy) for carrying out the characterization tests on the new filaments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Othmer, K. Encyclopedia of CHEMICAL Technology, Carbon and Graphite Fibers to Chlorocarbons and Chlorohydrocarbons-CSUB 1/SUB; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Kirchherr, J.; Piscicelli, L.; Bour, R.; Kostense-Smit, E.; Muller, J.; Huibrechtse-Truijens, A.; Hekkert, M. Barriers to the Circular Economy: Evidence From the European Union (EU). Ecol. Econ. 2018, 150, 264–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. A European Strategy for Plastics in a Circular Economy; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Directive 2008/98/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 19 November 2008 on Waste and Repealing Certain Directives; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lavers, J.L.; Bond, A.L. Exceptional and rapid accumulation of anthropogenic debris on one of the world’s most remote and pristine islands. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 6052–6055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon, S.; Burdfield-Steel, E. Avoiding Attack: The Evolutionary Ecology of Crypsis, Warning Signals and Mimicry. In Basic and Applied Ecology, 2nd ed.; Ruxton, G.D., Allen, W.L., Sherratt, T.N., Speed, M.P., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2004; pp. 54–55. [Google Scholar]

- Teuten, E.L.; Saquing, J.M.; Knappe, D.R.U.; Barlaz, M.A.; Jonsson, S.; Björn, A.; Rowland, S.J.; Thompson, R.C.; Galloway, T.S.; Yamashita, R.; et al. Transport and release of chemicals from plastics to the environment and to wildlife. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2009, 364, 2027–2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hahladakis, J.N.; Velis, C.A.; Weber, R.; Iacovidou, E.; Purnell, P. An overview of chemical additives present in plastics: Migration, release, fate and environmental impact during their use, disposal and recycling. J. Hazard. Mater. 2018, 344, 179–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stavropoulos, P.; Spetsieris, A.; Papacharalampopoulos, A. A Circular Economy based Decision Support System for the Assembly/Disassembly of Multi-Material Components. Procedia CIRP 2019, 85, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauerwein, M.; Doubrovski, E.L.; Balkenende, R.; Bakker, C.; Doubrovski, Z. Exploring the potential of additive manufacturing for product design in a circular economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 226, 1138–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikas, H.; Stavropoulos, P.; Chryssolouris, G. Additive manufacturing methods and modelling approaches: A critical review. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2015, 83, 389–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Ghataura, A.; Takagi, H.; Haroosh, H.J.; Nakagaito, A.N.; Lau, K.-T. Polylactic acid (PLA) biocomposites reinforced with coir fibres: Evaluation of mechanical performance and multifunctional properties. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2014, 63, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikas, H.; Lianos, A.K.; Stavropoulos, P. A design framework for additive manufacturing. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2019, 103, 3769–3783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speranza, D.; Citro, D.; Padula, F.; Motyl, B.; Marcolin, F.; Cali, M.; Martorelli, M. Additive Manufacturing Techniques for the Reconstruction of 3D Fetal Faces. Appl. Bionics Biomech. 2017, 2017, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, K.; Kumta, S.M.; Sze, K.; Wong, C. Use of a patient-specific CAD/CAM surgical jig in extremity bone tumor resection and custom prosthetic reconstruction. Comput. Aided Surg. 2012, 17, 284–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambu, R.; Motta, A.; Calì, M. Design of a Customized Neck Orthosis for FDM Manufacturing with a New Sustainable Bio-composite. In Lecture Notes in Mechanical Engineering; Springer Science and Business Media LLC: Berlin, Germany, 2019; pp. 707–718. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, T.T.; Dos Reis, A.C. Fabrication of dental implants by the additive manufacturing method: A systematic review. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2019, 122, 270–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambu, R.; Morabito, A. Porous Scaffold Design Based on Minimal Surfaces: Development and Assessment of Variable Architectures. Symmetry 2018, 10, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabort, E.; Barba, D.; Reed, R.C. Design of metallic bone by additive manufacturing. Scr. Mater. 2019, 164, 110–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Işmal, Ö.E.; Paul, R. Composite Textiles in High-Performance Apparel. In High-Performance Apparel; Elsevier BV: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 377–420. [Google Scholar]

- Kato, A.; Ikeda, Y.; Kohjiya, S. Carbon Black-Filled Natural Rubber Composites: Physical Chemistry and Reinforcing Mechanism. In Polymer Composites; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012; pp. 515–543. [Google Scholar]

- Clyne, T.W.; Hull, D. An Introduction to Composite Materials; Cambridge University Press (CUP): Cambridge, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gazzo, S.; Cuomo, M.; Boutin, C.; Contrafatto, L. Directional properties of fibre network materials evaluated by means of discrete homogenization. Eur. J. Mech.-A/Solids 2020, 82, 104009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Superlab. Available online: http://www.superlab.it/laboratorio/caratterizzazioni-meccaniche/ (accessed on 17 August 2020).

- Bledzki, A.K.; Jaszkiewicz, A.; Scherzer, D. Mechanical properties of PLA composites with man-made cellulose and abaca fibres. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2009, 40, 404–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corapi, D.; Morettini, G.; Pascoletti, G.; Zitelli, C. Characterization of a Polylactic acid (PLA) produced by Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) technology. Procedia Struct. Integr. 2019, 24, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salim, M.A.; Termiti, Z.H.; Saad, A.M. Mechanical Properties on ABS/PLA Materials for Geospatial Imaging Printed Product using 3D Printer Technology. Ref. Modul. Mater. Sci. Mater. Eng. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Geng, P.; Li, G.; Zhao, D.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, J. Influence of Layer Thickness and Raster Angle on the Mechanical Properties of 3D-Printed PEEK and a Comparative Mechanical Study between PEEK and ABS. Materials 2015, 8, 5834–5846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, B.A.; Warner, P.; Wang, H. Antibacterial Properties of Hemp and Other Natural Fibre Plants: A Review. BioResources 2014, 9, 3642–3659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lanzotti, V.; Grasso, M.; Staiano, G.; Martorelli, M. The impact of process parameters on mechanical properties of parts fabricated in PLA with an open-source 3-D printer. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2015, 21, 604–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanetti, E.M.; Aldieri, A.; Terzini, M.; Cali, M.; Franceschini, G.; Bignardi, C. Additively Manufactured Custom Load-Bearing Implantable Devices. Australas. Med. J. 2017, 10, 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).