An Inspection Robot for Belt Conveyor Maintenance in Underground Mine—Infrared Thermography for Overheated Idlers Detection

Abstract

1. Introduction

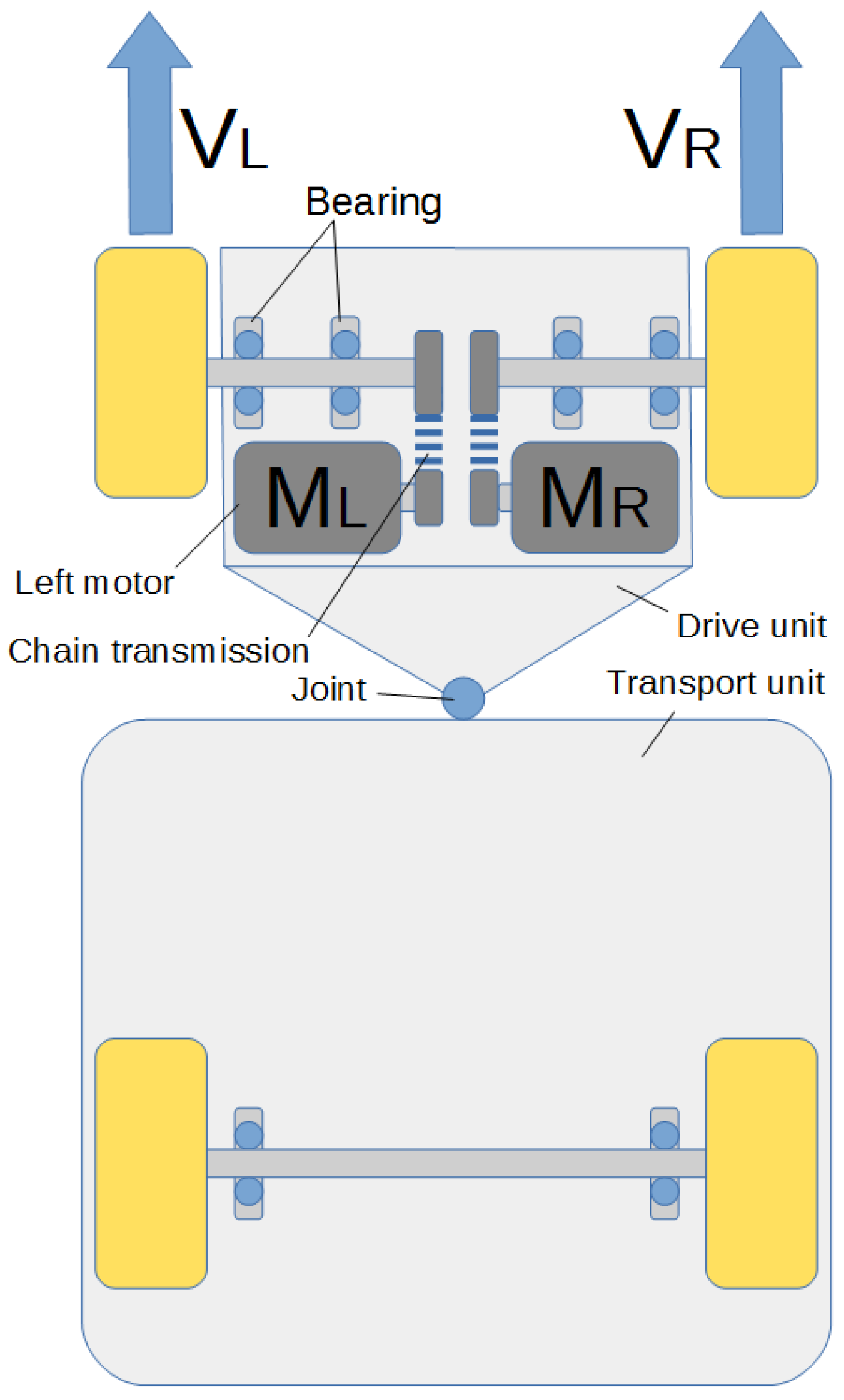

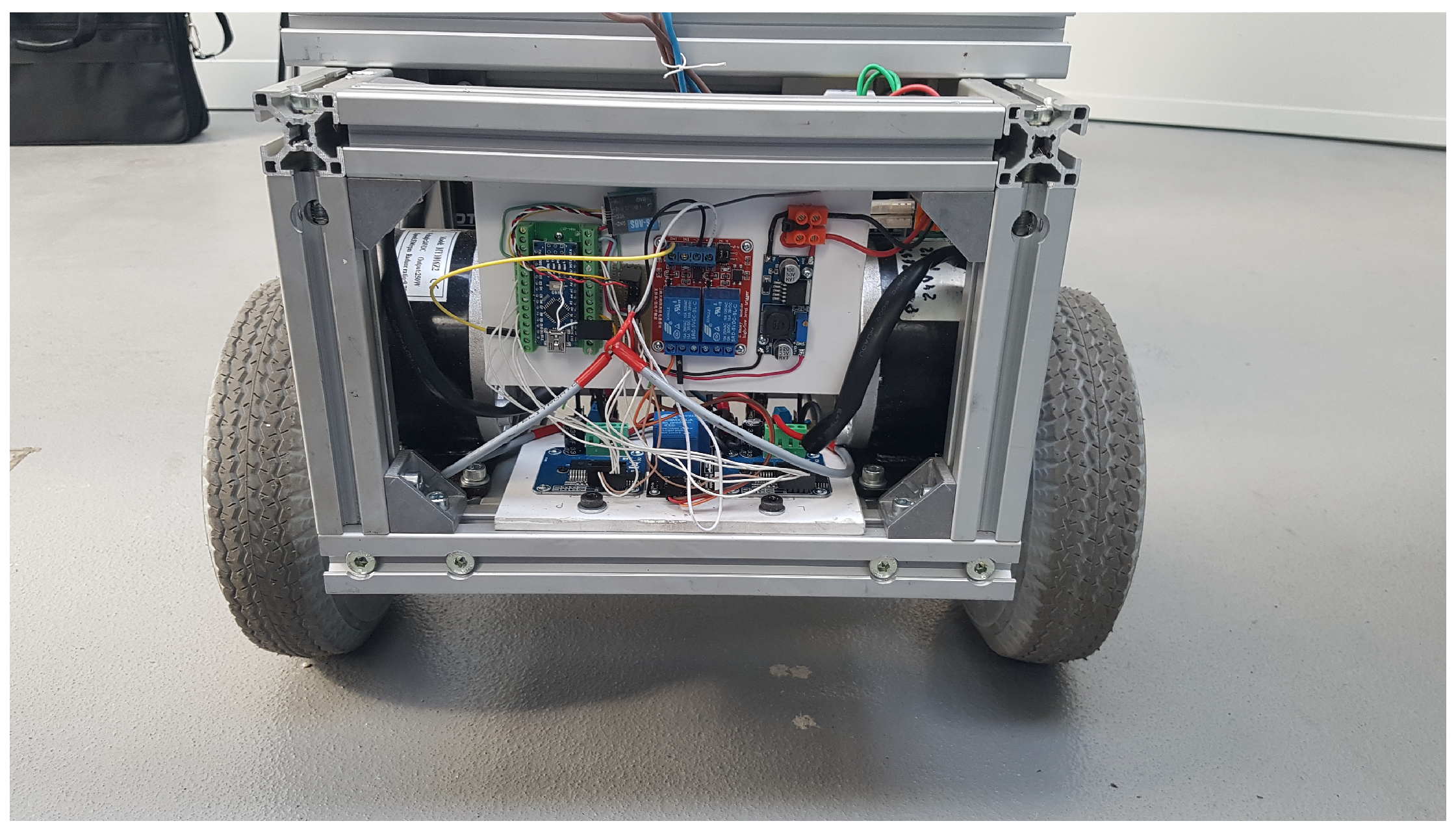

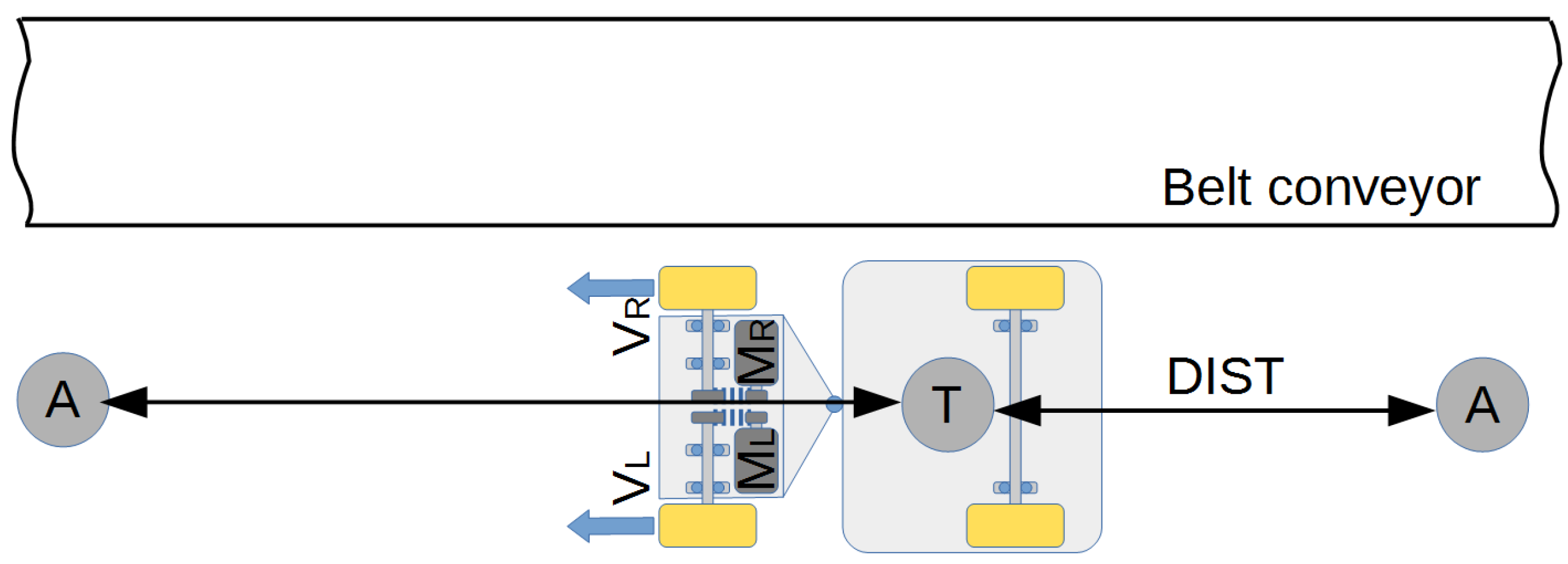

2. A UGV Platform

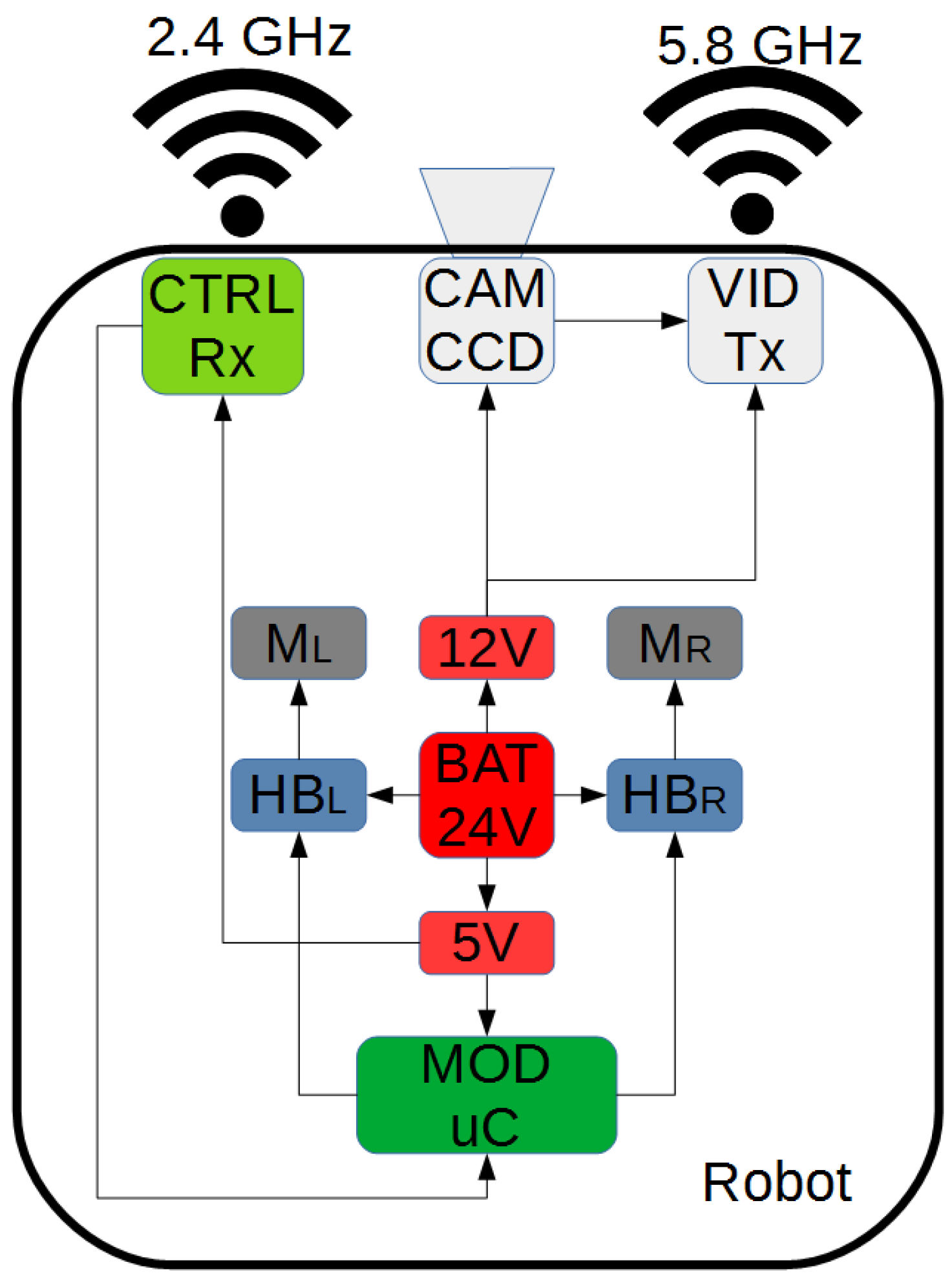

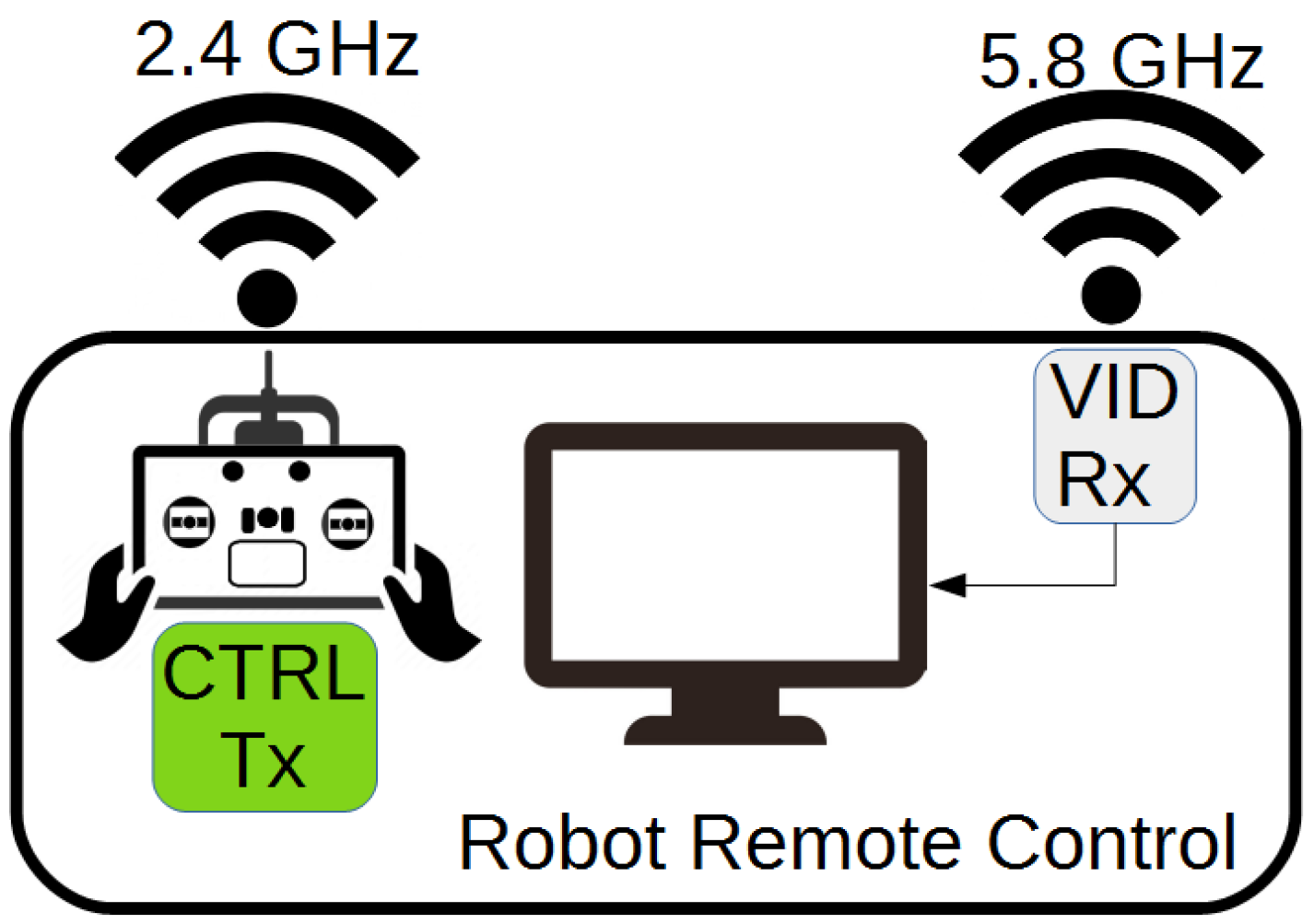

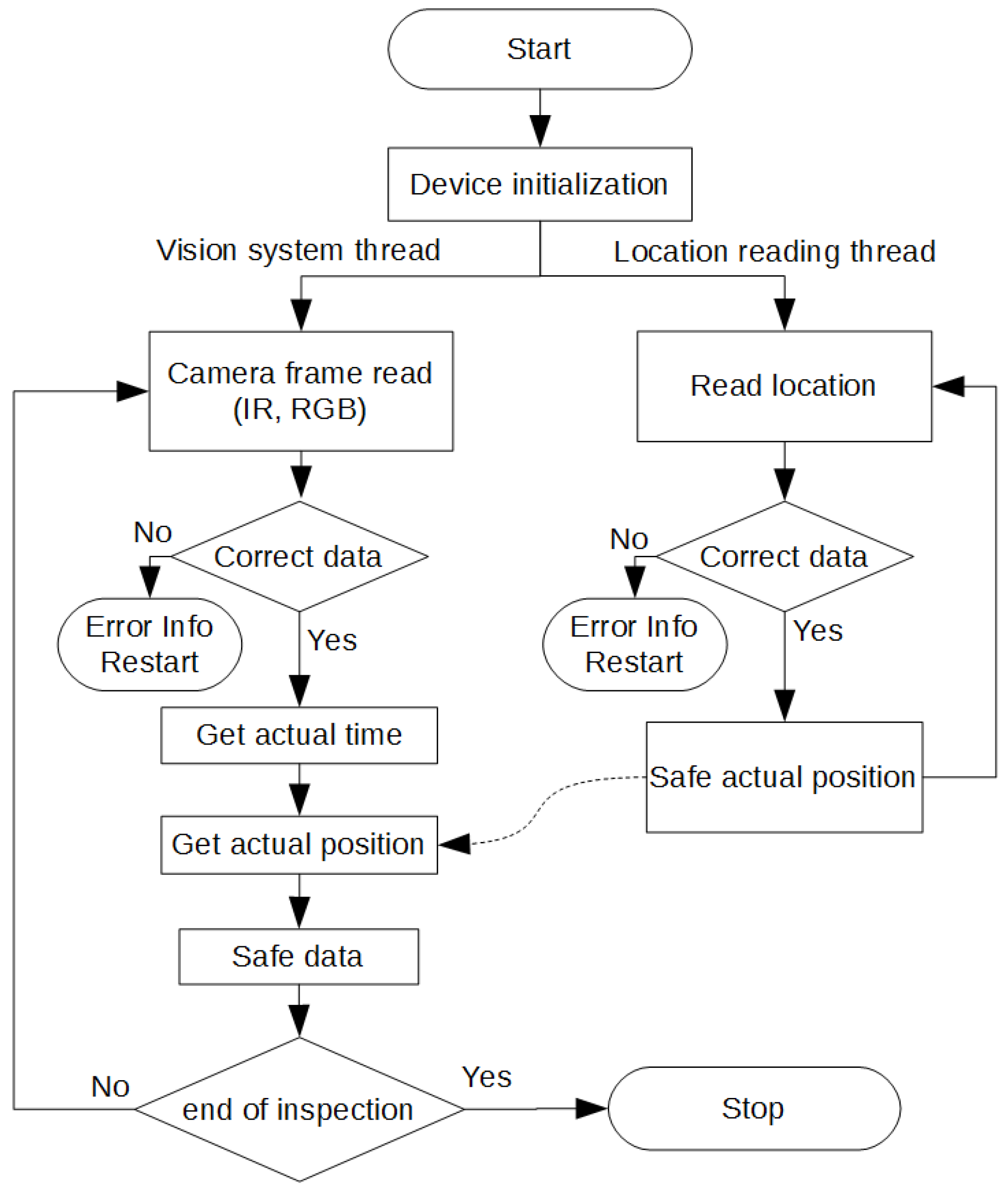

2.1. Control System of the Mobile Platform

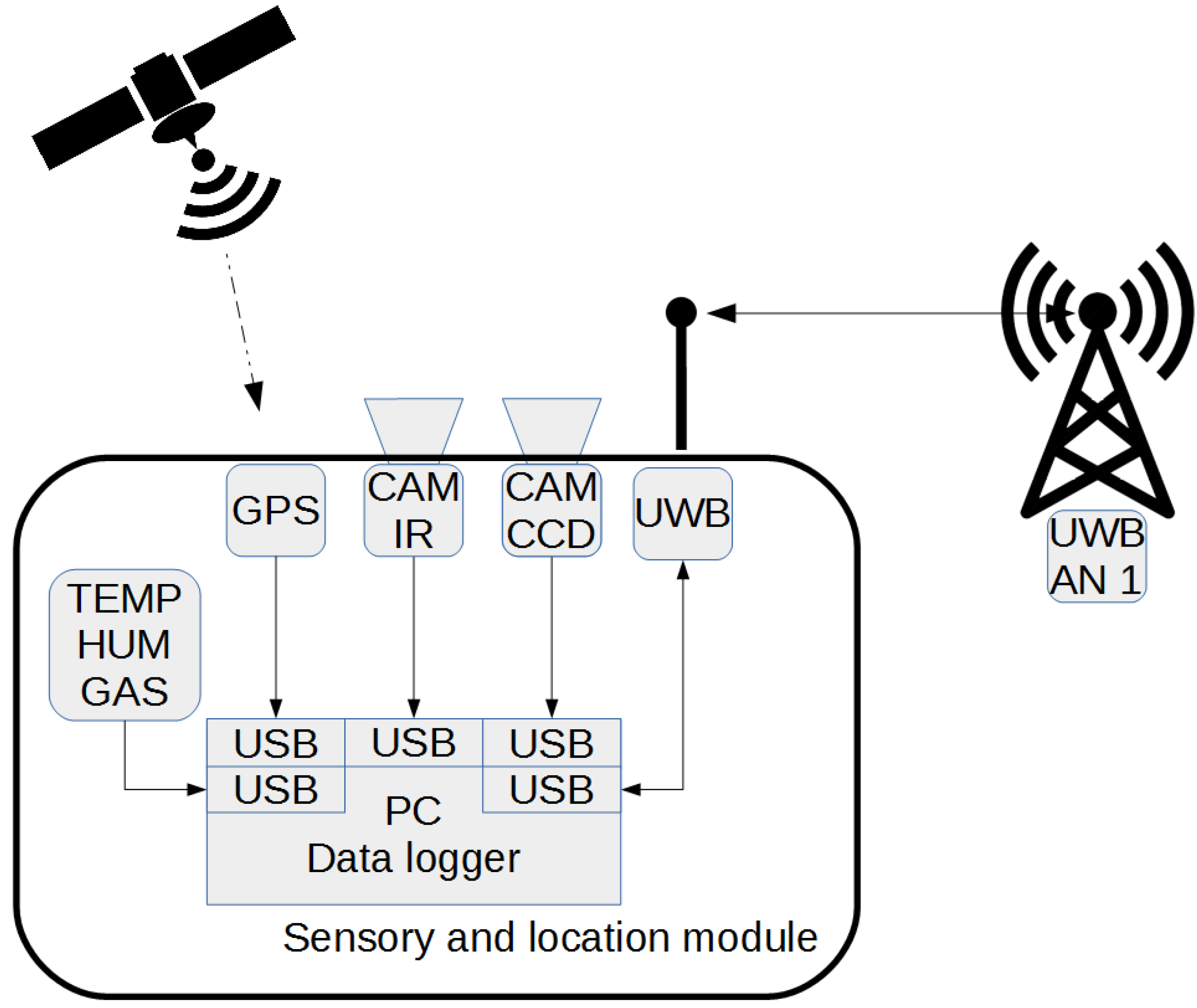

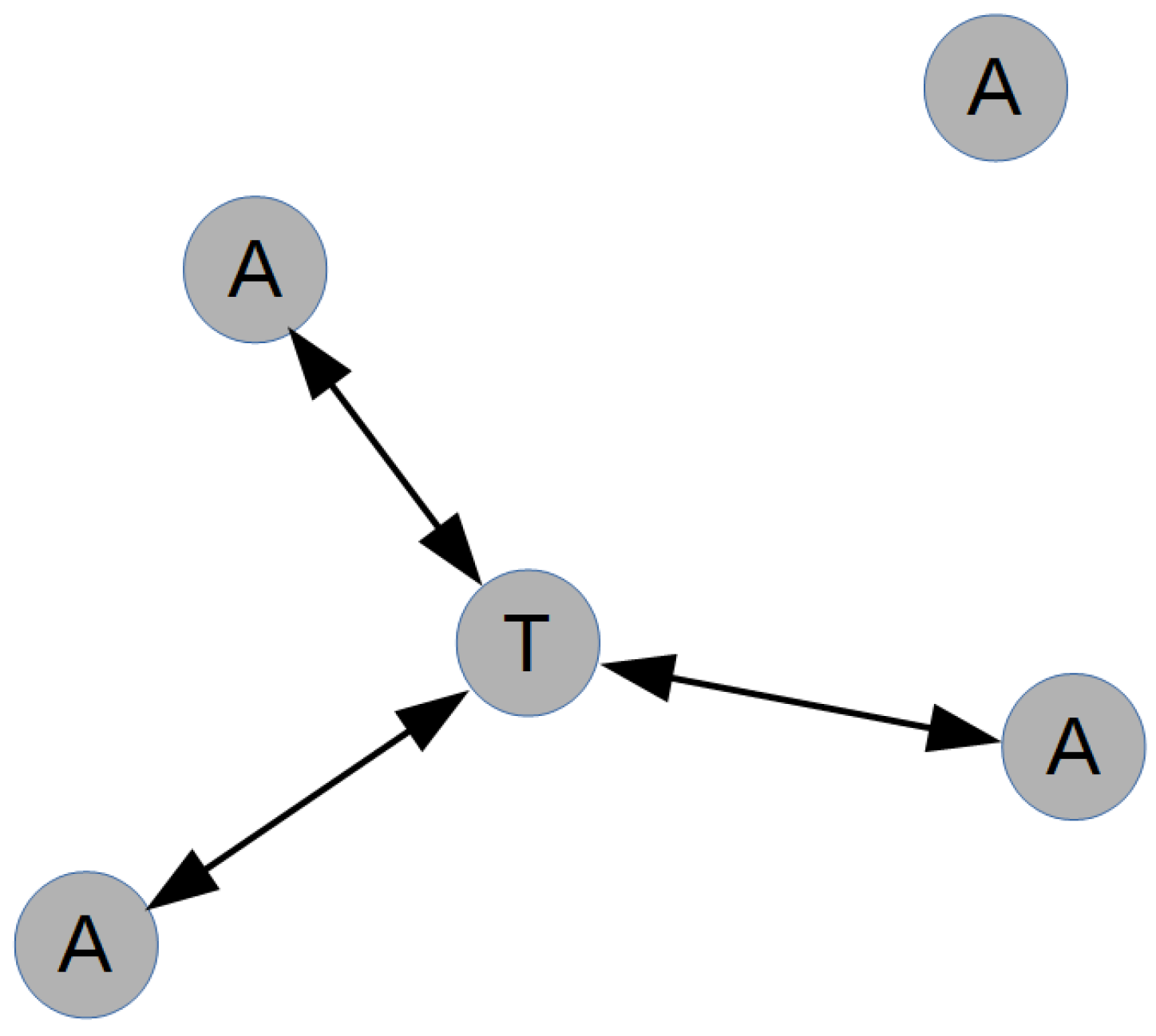

2.2. Robot Localization System

2.3. Onboard Sensors

2.4. Inspection Data Analysis Module

2.5. Data Transmission and Recording

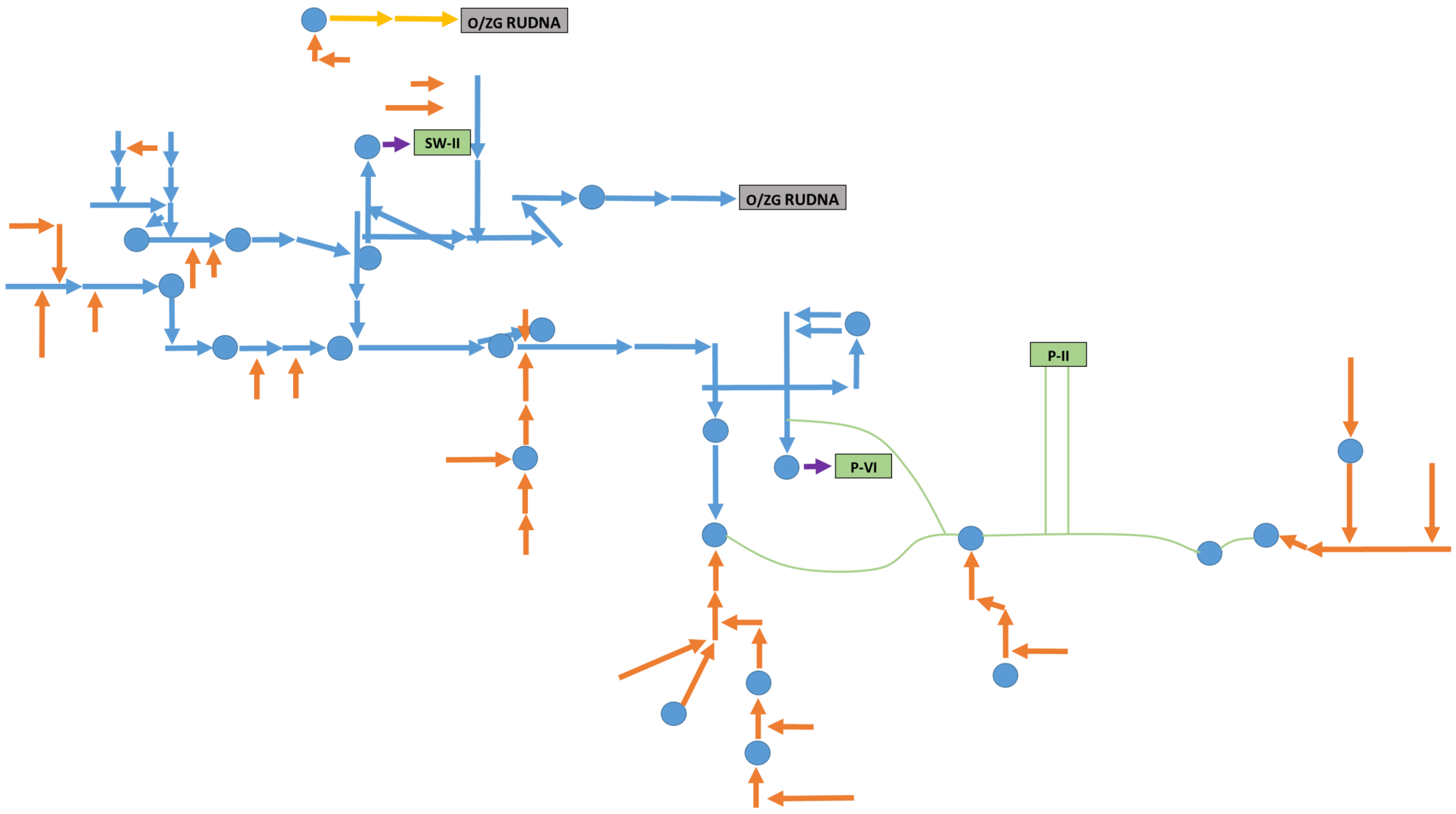

3. The Use Case Description

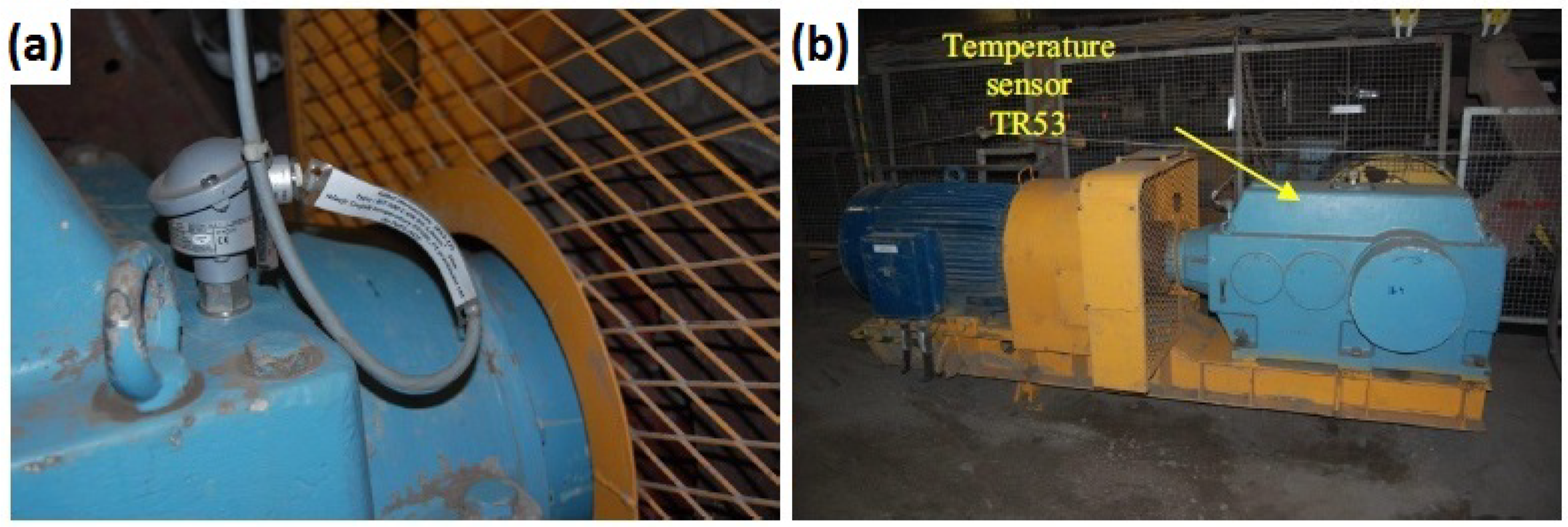

3.1. A Belt Conveyor Test Rig

3.2. Plan of the Experiment

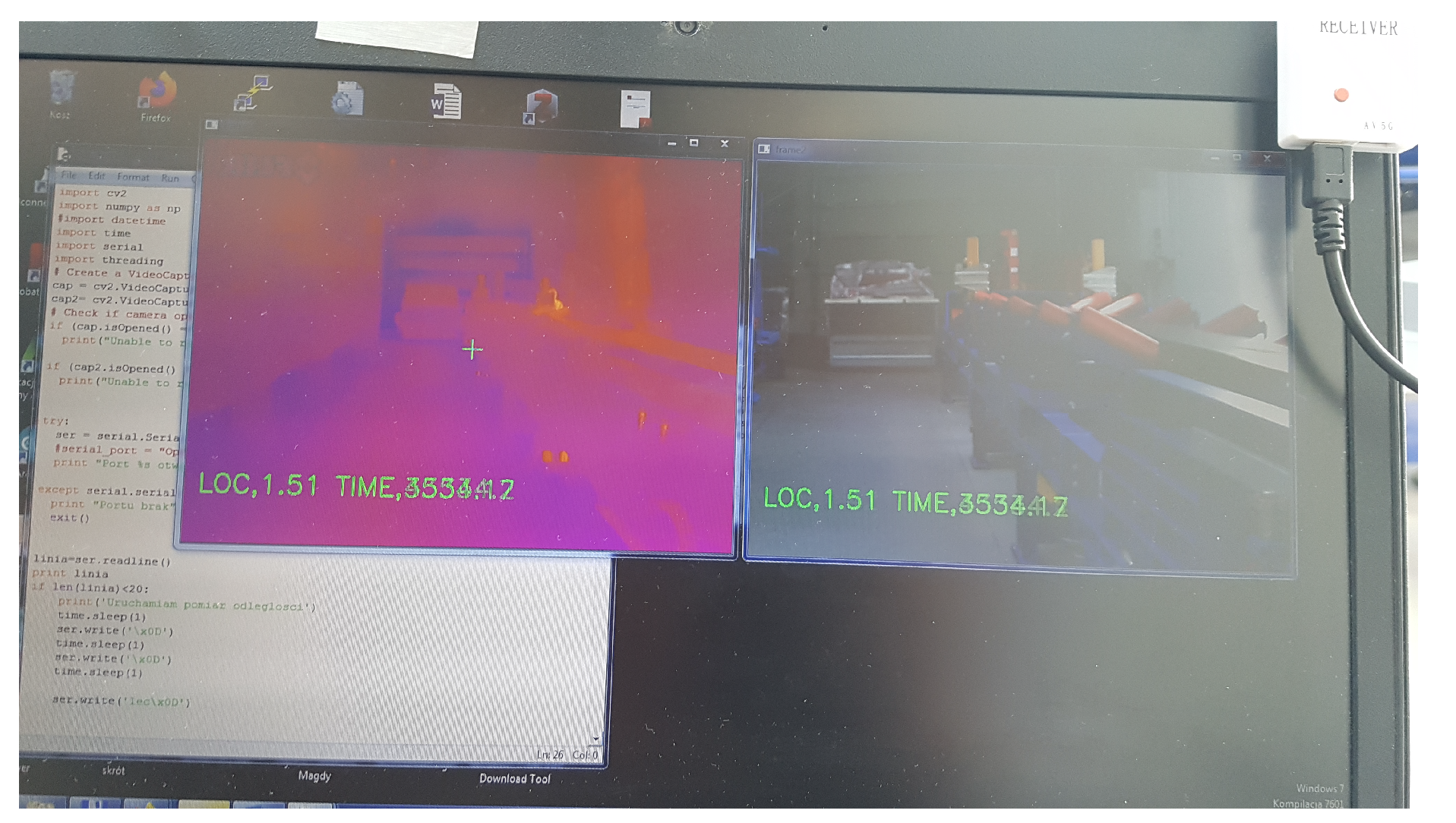

3.3. Results

4. The Inspection Data Processing—Methods and Results

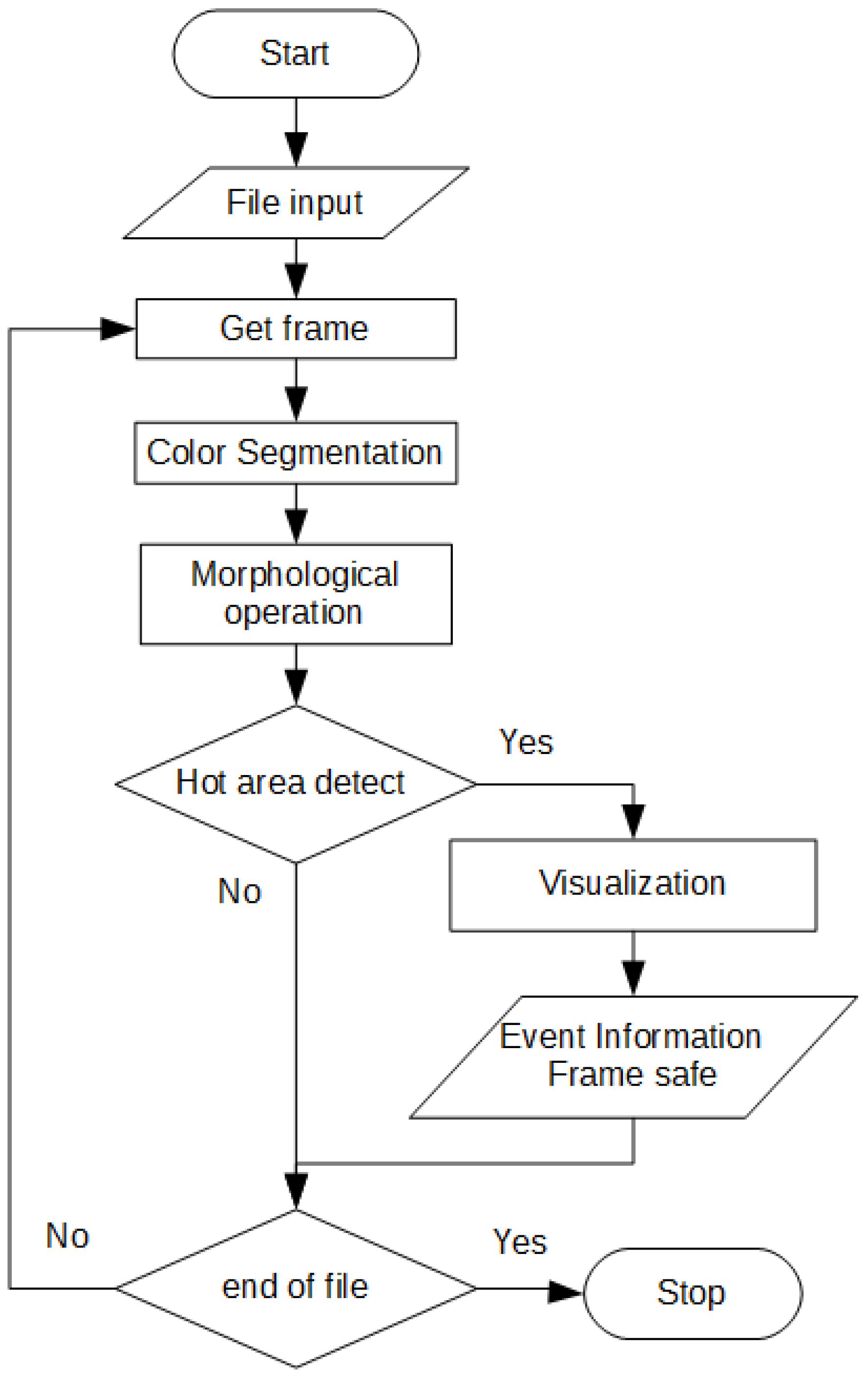

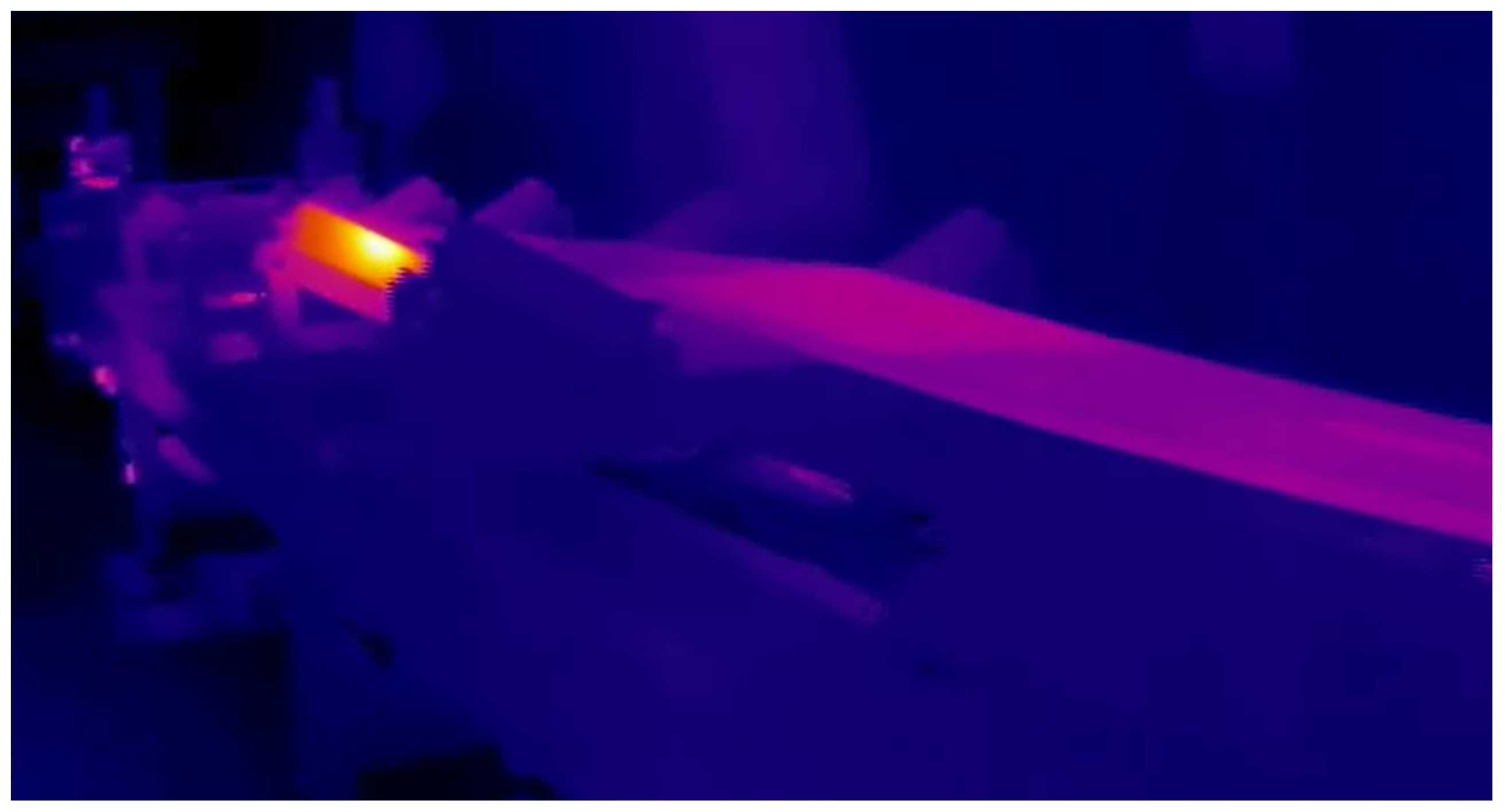

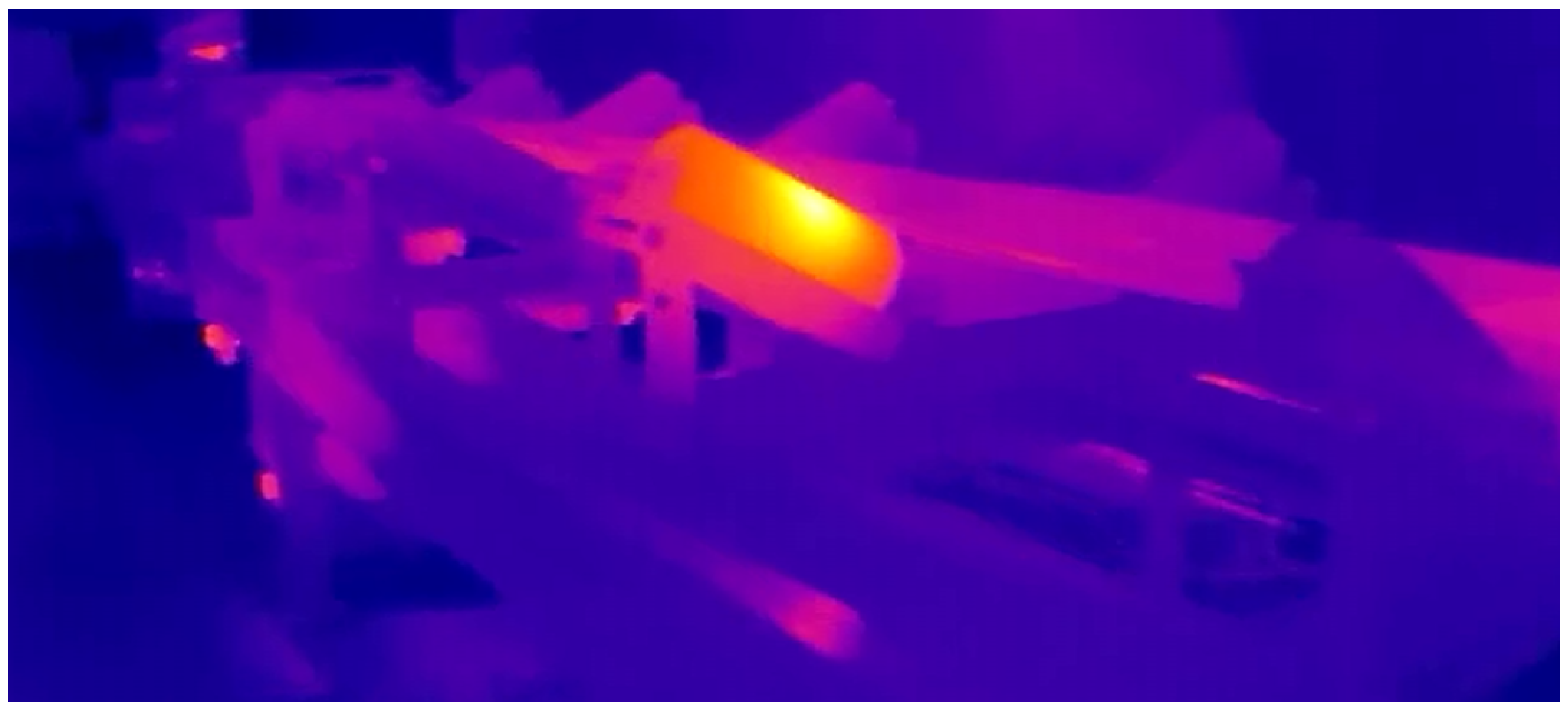

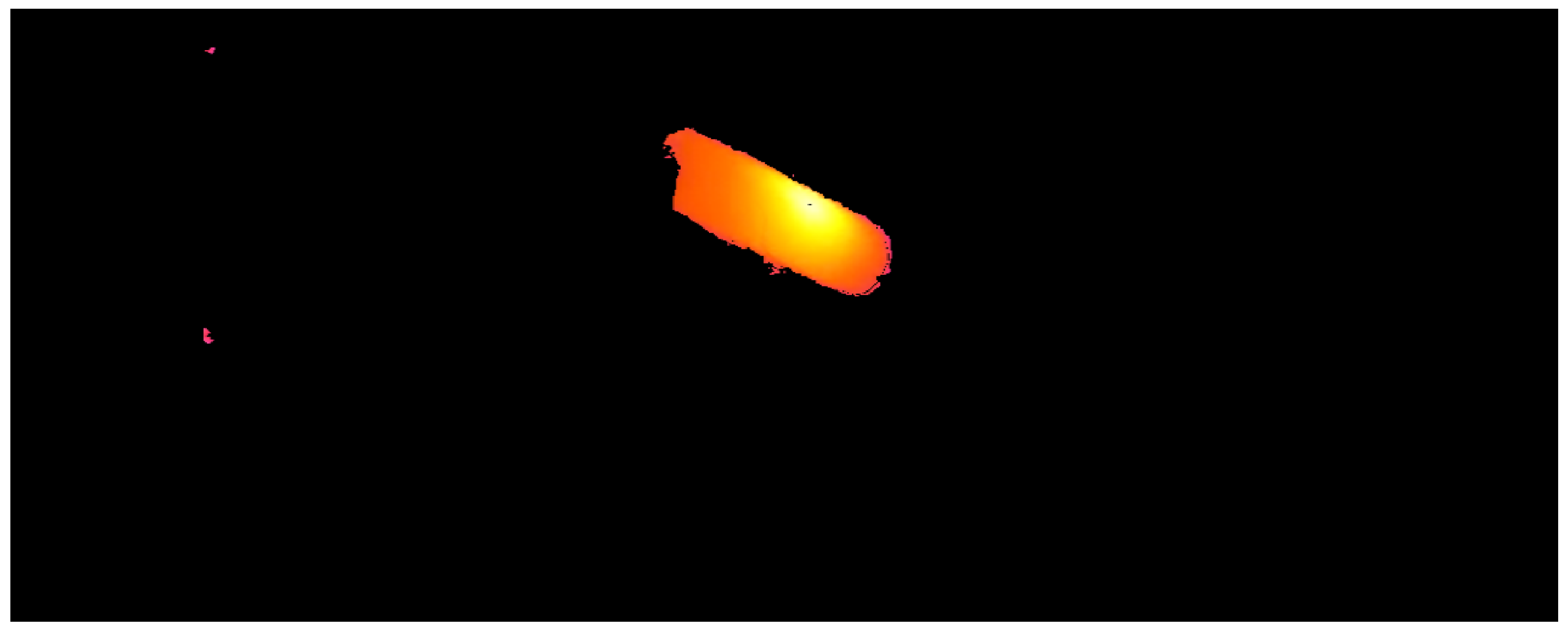

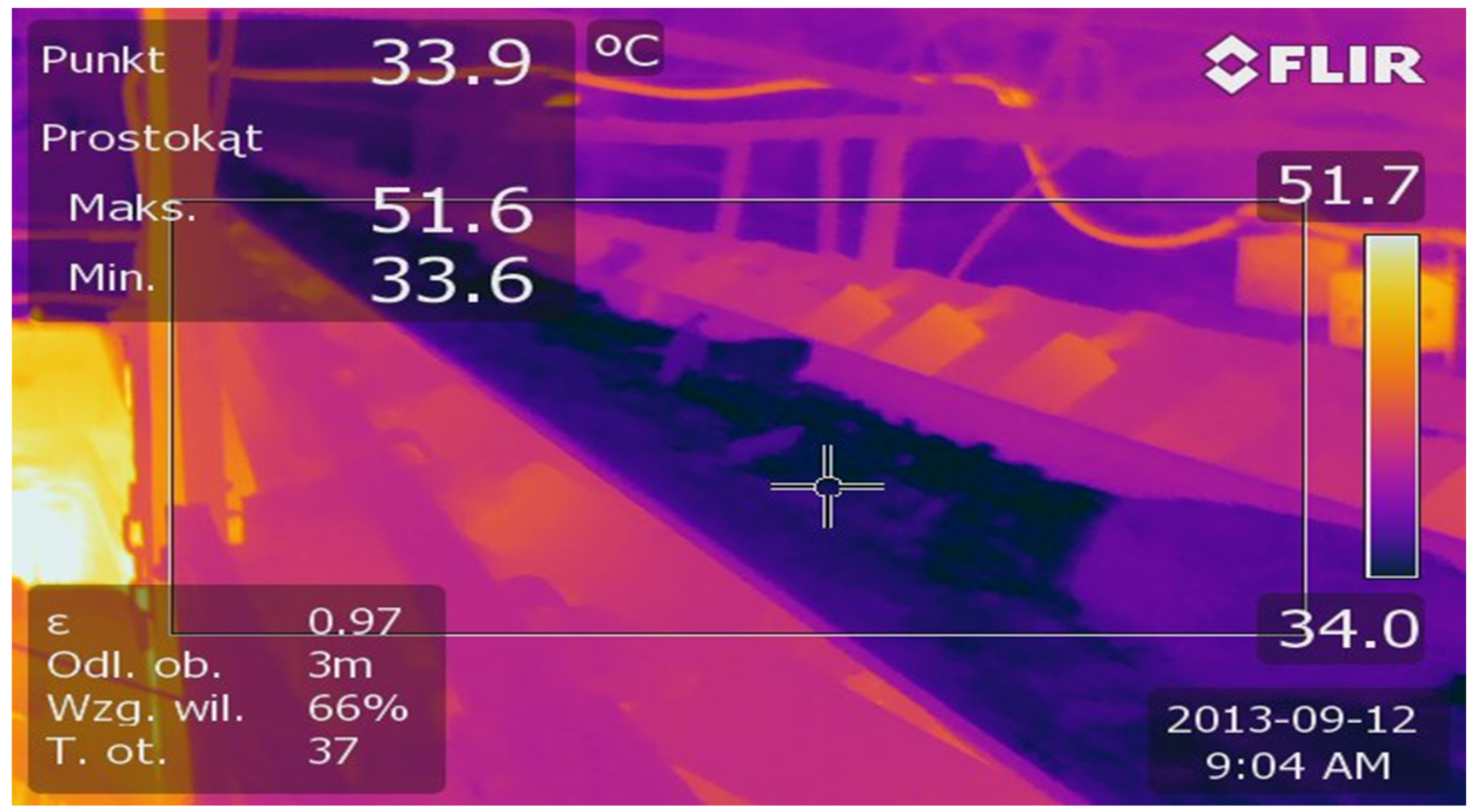

4.1. IR Data Processing for Hot Spot Detection

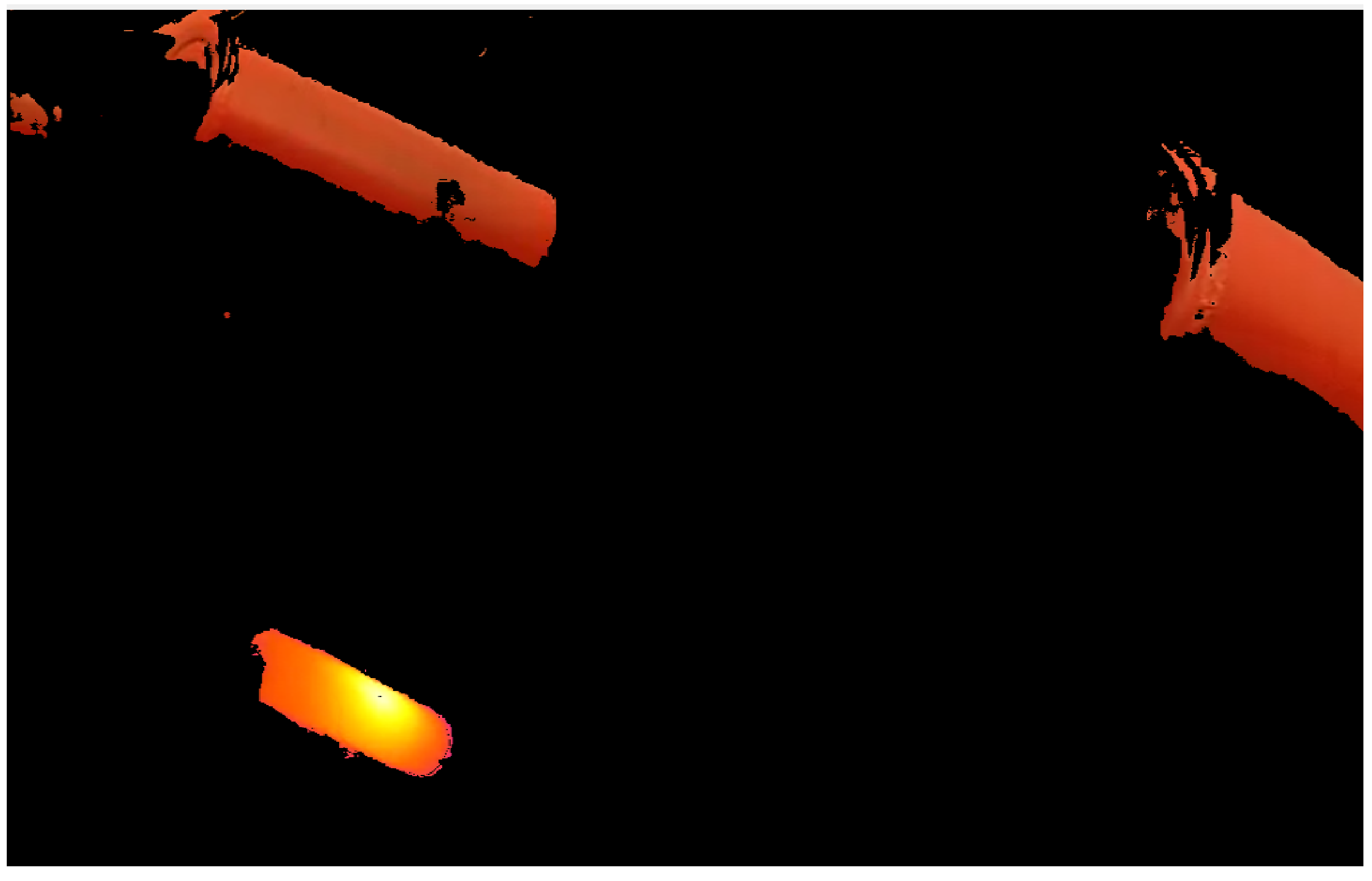

4.2. RGB Image Data Processing for Idler Detection

4.3. The Fusion of RGB Image and IR Data Processing for Hot Idler Detection

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ten Technologies with the Power to Transform Mining. MINE Mag. 2014. Available online: https://www.mining-technology.com/features/featureten-technologies-with-the-power-to-transform-mining4211240/ (accessed on 14 May 2020).

- Liu, X.; Pang, Y.; Lodewijks, G.; He, D. Experimental research on condition monitoring of belt conveyor idlers. Measurement 2018, 127, 277–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Król, R.; Kisielewski, W. Research of loading carrying idlers used in belt conveyor—Practical applications. Diagnostyka 2014, 15, 67–73. [Google Scholar]

- Król, R.; Kisielewski, W. The influence of idlers on energy consumption of belt conveyor. Min. Sci. 2014, 21, 61–72. [Google Scholar]

- Cunha, F.; Youcef-Toumi, K. Ultra-Wideband Radar for Robust Inspection Drone in Underground Coal Mines. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Brisbane, Australia, 21–25 May 2018; pp. 86–92. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, Z.; Fei, J.; Zhang, G.; Jiang, W. Research on the Monitoring System of Belt Conveyor Based on Suspension Inspection Robot. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Real-time Computing and Robotics (RCAR), Kandima, Maldives, 1–5 August 2018; pp. 657–661. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, F.; Moore, W.; Antolovich, M.; Gao, J. Robot learning by a mining tunnel inspection robot. In Proceedings of the 2012 9th International Conference on Ubiquitous Robots and Ambient Intelligence (URAI), Daejeon, South, 26–28 November 2012; pp. 200–204. [Google Scholar]

- Roh, S.G.; Ryew, S.M.; Yang, J.H.; Choi, H.R. Actively steerable in-pipe inspection robots for underground urban gas pipelines. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (Cat. No.01CH37164), Seoul, Korea, 21–26 May 2001; Volume 1, pp. 761–766. [Google Scholar]

- Bing, J.; Sample, A.P.; Wistort, R.M.; Mamishev, A.V. Autonomous robotic monitoring of underground cable systems. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Advanced Robotics, Seattle, WA, USA, 17–20 July 2005; pp. 673–679. [Google Scholar]

- Zimroz, R.; Hutter, M.; Mistry, M.; Stefaniak, P.; Walas, K.; Wodecki, J. Why Should Inspection Robots be used in Deep Underground Mines? In Proceedings of the 27th International Symposium on Mine Planning and Equipment Selection—MPES 2018; Widzyk-Capehart, E., Hekmat, A., Singhal, R., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 497–507. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Savkin, A.V.; Vucetic, B. Autonomous Area Exploration and Mapping in Underground Mine Environments by Unmanned Aerial Vehicles. Robotica 2020, 38, 442–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, I.D.; Cladera, F.; Cowley, A.; Shivakumar, S.S.; Lee, E.S.; Jarin-Lipschitz, L.; Bhat, A.; Rodrigues, N.; Zhou, A.; Cohen, A.; et al. Mine Tunnel Exploration Using Multiple Quadrupedal Robots. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2020, 5, 2840–2847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papachristos, C.; Khattak, S.; Mascarich, F.; Alexis, K. Autonomous Navigation and Mapping in Underground Mines Using Aerial Robots. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Aerospace Conference, Big Sky, MO, USA, 2–9 March 2019; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Thrun, S.; Thayer, S.; Whittaker, W.; Baker, C.; Burgard, W.; Ferguson, D.; Hahnel, D.; Montemerlo, D.; Morris, A.; Omohundro, Z.; et al. Autonomous exploration and mapping of abandoned mines. IEEE Robot. Autom. Mag. 2004, 11, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grehl, S.; Sastuba, M.; Donner, M.; Ferber, M.; Schreiter, F.; Mischo, H.; Jung, B. Towards virtualization of underground mines using mobile robots—From 3D scans to virtual mines. In Proceedings of the 23rd International Symposium on Mine Planning & Equipment Selection, Johannesburg, South Africa, 9–11 November 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Maity, A.; Majumder, S.; Ray, D.N. Amphibian subterranean robot for mine exploration. In Proceedings of the 2013 International Conference on Robotics, Biomimetics, Intelligent Computational Systems, Jogjakarta, Indonesia, 25–27 November 2013; pp. 242–246. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, R.R.; Kravitz, J.; Stover, S.L.; Shoureshi, R. Mobile robots in mine rescue and recovery. IEEE Robot. Autom. Mag. 2009, 16, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Gao, J.; Li, K.; Lin, W.; Bi, S. Embedded control system design for coal mine detect and rescue robot. In Proceedings of the 2010 3rd International Conference on Computer Science and Information Technology, Chengdu, China, 9–11 July 2010; Volume 6, pp. 64–68. [Google Scholar]

- Green, J. Mine rescue robots requirements Outcomes from an industry workshop. In Proceedings of the 2013 6th Robotics and Mechatronics Conference (RobMech), KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, 30–31 October 2013; pp. 111–116. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, G.; Zhu, L.; Han, Z.; Zhao, J. Distribution and communication of multi-robot system for detection in the underground mine disasters. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Biomimetics (ROBIO), Guilin, China, 18–22 December 2009; pp. 1439–1444. [Google Scholar]

- Szrek, J.; Arent, K. Measurement system for ground reaction forces in skid-steering mobile platform rex. In Proceedings of the 2015 20th International Conference on Methods and Models in Automation and Robotics (MMAR), Międzyzdroje, Poland, 24–27 August 2015; pp. 756–760. [Google Scholar]

- Szrek, J.; Wojtowicz, P. Idea of wheel-legged robot and its control system design. Bull. Pol. Acad. Sci. Technol. Sci. 2010, 58, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DWM1001 Module Documentation. Available online: https://www.decawave.com/product/dwm1001-module/ (accessed on 14 May 2020).

- OpenCV Documentation: Changing Colorspaces. Available online: https://docs.opencv.org/trunk/df/d9d/tutorial_py_colorspaces.html (accessed on 13 May 2020).

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Szrek, J.; Wodecki, J.; Błażej, R.; Zimroz, R. An Inspection Robot for Belt Conveyor Maintenance in Underground Mine—Infrared Thermography for Overheated Idlers Detection. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 4984. https://doi.org/10.3390/app10144984

Szrek J, Wodecki J, Błażej R, Zimroz R. An Inspection Robot for Belt Conveyor Maintenance in Underground Mine—Infrared Thermography for Overheated Idlers Detection. Applied Sciences. 2020; 10(14):4984. https://doi.org/10.3390/app10144984

Chicago/Turabian StyleSzrek, Jarosław, Jacek Wodecki, Ryszard Błażej, and Radoslaw Zimroz. 2020. "An Inspection Robot for Belt Conveyor Maintenance in Underground Mine—Infrared Thermography for Overheated Idlers Detection" Applied Sciences 10, no. 14: 4984. https://doi.org/10.3390/app10144984

APA StyleSzrek, J., Wodecki, J., Błażej, R., & Zimroz, R. (2020). An Inspection Robot for Belt Conveyor Maintenance in Underground Mine—Infrared Thermography for Overheated Idlers Detection. Applied Sciences, 10(14), 4984. https://doi.org/10.3390/app10144984