1. Introduction

Investments in culture represent one of the main drivers for the development of a country due to the positive externalities related to citizen participation in these activities (

Benhamou and Amici 2001;

Palmi et al. 2016).

However, the management of cultural institutions by government is very often criticised (

Venturelli 2012a). This is related to the divergence between financial performance, heritage asset value, and the value perceived by the citizen. Moreover, as in other sectors, the behaviour of public managers is negatively influenced by the high degree of bureaucratization and by the lack of market incentives related to financial performance (

Meneguzzo 2007).

The management of public museums (PM) represents a typical example of this phenomenon. In fact, the profit of a PM is not related to the value of the heritage assets due to several barriers that impact their attractiveness, which is influenced by context-related factors, such as geographical localization and seasonality. Moreover, asymmetric information between PMs and visitors is a further limitation, caused by the difficulty of evaluating the value of the heritage assets. Furthermore, the differences between museum visitors in terms of behaviour and exigence represent another criticism of the effective organization of the entities (

Vecco and Srakar 2018).

These problems are more complex in contexts where a higher number of public entities operate in the cultural sector. In this sense, Italy plays a central role due to its large number of heritage assets (

UNESCO 2019). However, despite the lack of financial resources, the Italian government has focussed on this area, and the Department of Culture (MiBACT) has introduced a new form of managerial tool in order to achieve the highest degree of effectiveness.

More specifically, the collaboration between MiBACT, Civis. and the Boston Consulting Group has favoured the introduction of a new form of financial reporting in the public museum sector (PM), known as the Integrated Economic Report (IER) (

Fissi et al. 2018). This does not replace the traditional form of financial reporting but represents a complementary form of managerial reporting. The main aims of this new regulation are linked to the need to increase the overall degree of transparency and to favour the identification of new strategies. This has resulted from the difficulty of understanding the real performance of an entity in the traditional balance sheets.

Based on this evidence, the aim of this paper is to evaluate the benefits related to the introduction of a new form of accountability in PM through multiple case studies (

Stake 2013). To this end, we will evaluate the IER provided by the Pinacoteca di Brera, the Galleria Borghese, Galleria Estense, Polo Museale dell’Umbria, and Polo Museale della Puglia. We have also analysed the IER published in 2017 due to the unavailability of IERs published after that date.

Our results will provide some insights for public sector entities to provide further information to stakeholders about their outcomes (

Borgonovi et al. 2018).

2. Literature Review

2.1. The New Public Management (NPM) in the Cultural Sector

The need to introduce managerial practices in the cultural public sector began in the 1990s due to progressive disinvestment by European governments. Since then, academics have started to analyse new forms of paradigms in order to provide policy makers with the possible tools to manage criticisms related to the lack of resources (

Mandel 2016).

The introduction of managerial practices by governments in the cultural sector followed, as demonstrated in previous studies on the new public management (NPM) paradigm (

Rosenstein 2010). The NPM approach consists of a set of principles that require public sector entities to adopt new operational paradigms inspired by virtuous principles, such as transparency, flexibility, and effectiveness (

Reichard 1998). In this sense, public sector firms began to act as dynamic institutions in order to adapt their business model to their new needs (

Milone 2004).

However, the achievement of these targets by cultural institutions is more complex due to several limitations related to the divergences between the value of heritage goods and revenues (

Caserta and Russo 2002). In fact, the demand for heritage services is influenced by external factors, e.g., infrastructures, the characteristics of the destination, and synergy with other institutions (

Siano et al. 2010).

Therefore, given the impact of these multidimensional factors, it becomes difficult for cultural institutions to accrue more revenue than the costs incurred. As highlighted by

Venturelli et al. (

2015), the performance of a heritage firm is characterised by the coexistence of several dimensions of analysis related to economic, social, and cultural items. In this sense, a real understanding of financial performance could not be separated from the social and cultural dimensions that characterise each cultural firm (

Bollo and Zhang 2017).

However, the current scenario is characterised by the different degrees of information about non-financial performance achieved by the firms that operate in the public sector (

Liguori et al. 2012;

Pizzi et al. 2019). The lack of non-financial information negatively impacts the possibility to act in accordance with the NPM paradigms due to the absence of qualitative information about the firms’ performances (

Jackson and Lapsley 2003;

Caputo and Di Cagno 2010).

2.2. The Concept of Accountability in NPM

The public sector is characterised by the limited use of managerial accounting tools which, in turn, is related to the high degree of bureaucracy that characterises the public sector (

Panozzo 2000). In this sense, prior studies have highlighted how the accounting framework adopted by the Italian Public Sector does not provide adequate information on the organization dynamics that characterise the entities (

Caputo and Di Cagno 2010). Furthermore, the current debate about public sector firms highlights the need to provide more information about the outcomes of entities (

Borgonovi et al. 2018).

For years, the issue of accountability in public institutions has been the subject of particular attention due to the gradual emergence of corporate processes which aim to introduce managerial strategies in order to achieve effectiveness and efficiency in line with the principles of new public management (

Goddard 2005;

Timoshenko 2018). Accountability, in the case of either public or private institutions, is now considered a real obligation towards external and internal stakeholders (

Freeman 1984).

The term ‘accountability’, widely used in business studies, does not yet have a singular meaning because it varies according to the different nature of the stakeholders, the different measure of the obligation of the subjects who, with diversified activities, must give an account of their work (

Botes et al. 2013). Of Anglo-Saxon origin, the term ‘accountability’ stems from the verb “to account for” and the noun “ability” (

Monteduro 2012). A literal translation, often adopted in different national contexts, identifies “responsibility” or “reporting” as some of the more common definitions which, when taken individually, do not appear sufficiently appropriate to justify the use of the original term.

2.3. Accountability in the Museum Sector

The significant changes that have characterized museum institutions have revealed the need to adopt suitable information tools in order to give an idea of the socio-cultural objectives and the economic and financial results achieved (

Legget 2018). This need derives from the progressive introduction of the managerial philosophy, with the use of more suitable methodologies and communication tools, to overcome the crystallization that has distinguished them (

Milone 2004;

Venturelli 2007).

In particular, it has become essential to activate information and accounting systems to demonstrate, document, and justify to the various stakeholders in the activity carried out, the procedures followed, and the effects generated in a transparent and truthful way. Relations with stakeholders are necessary to acquire the legitimacy that, differently from that of the past, must persist over time and increase in the reference context as an indispensable element for the development of the institution (

Moreno-Luzon et al. 2018).

Accountability puts considerable pressure on those who, at different levels, must work in the structure and report to the various stakeholders on the use of the resources acquired and the results achieved, in qualitative and quantitative terms and congruent with the institutional aims (

Dal Maso et al. 2018). In this sense, the aim of the IER is to carry out an adequate reporting process that demonstrates, with the necessary documentation and in a transparent manner, the activity carried out, the means employed, and the effects on the community that, if it sees its own expectations satisfied, supports the museum institution and promotes its raison d’être.

Ultimately, the governing bodies of museums must be able to have a clear and comprehensive accounting report of the activity carried out, and the results achieved with the overall resources acquired, which is indispensable for formulating a reliable judgment on their commitment and demonstrated capacities (

Alexius and Örnberg 2015). At the same time, with an effective external communication strategy, stakeholders can be encouraged to participate in future actions in which they have already expressed an interest, and in which they may be prepared to invest (

Low and Cowton 2004).

3. From the Traditional Financial Reporting to the Integrated Economic Report (IER)

The increasing attention paid by governments and stakeholders alike to the financial stability of public institutions has favoured the introduction of new reporting tools in order to increase the overall degree of knowledge about the economic performance achieved by museums.

The aim of these reports is not merely the identification of differences between revenues and costs, but it is extended to further perspectives such as the consolidation of the reputation of museum institution (

Sanesi 2014). The provision of alternative forms of financial reporting tools represents an effective strategy to provide to governing bodies and stakeholders with details about the non-financial aspects related to the managerial activities developed during the period observed. Furthermore, the accountability of these information systems could be perceived by citizens as a signal of transparency and interest them to engage in an effective way with stakeholders (

Venturelli 2012b)

However, the financial analysis of the performance of a public museum represents a complex activity due to the coexistence of several criticisms in terms of financial valuation. In fact, an adequate analysis of a public museum cannot be limited to the evaluation of the assets, because a large part of its economic performance could be related to intangible items such as the reputation, localization, and synergies with other entities. In this sense, public managers need adequate information to understand the internal and the external dynamics related to the institutions.

According to this evidence, during recent decades, the MIBACT has started to develop new form of regulation to sustain the development of the Museum Institution through managerial approaches inspired by the NPM paradigms.

The first approach to the topics has been reported in the guidance act (

MiBACT 2001). The guidance act states that an autonomous museum’s resources should be represented in the operating budgets in compliance with current legislation. Furthermore, it requires the control of the financial information reported. A second initiative has been represented by the D.M. of 23.12.2003 n.240 that identified a set of common rules about financial reporting disclosure. However, the initiative was limited by the absence of consolidated reporting standards provided by the international standard setters.

Furthermore, these initiatives have been conducted during a period characterized by the central role covered by the financial resources provided by the Italian government to sustain public museums (

Fissi et al. 2018). Furthermore, private stakeholders such as philanthropic institutions and cultural organizations were not satisfied about the degree of transparency.

According to the scientific debate activated by academics (

García-Sánchez et al. 2013;

Ferrarese 2016) and practitioners (

CNDCEC 2002), the Italian Government has introduced the IER in 2014. The main aim of the IER has been to engage in a more effective way with stakeholders. It was first implemented in 2016 after a preliminary assessment made by MiBACT, Civicum, and the Boston Consulting Group. The aim of the preliminary assessment was to identify a new reporting standard for the Soprintendenza di Milano and Pinacoteca di Brera. However, during these consultations, the research groups extended the IER application to other museums in order to evaluate their effectiveness in more depth.

In 2017, MiBACT introduced the final reporting standard to be applied by three museums (Galleria Borghese, Pinacoteca di Brera e Gallerie Estensi) and two regional museum centres (Polo Museale della Puglia; Polo Museale dell’Umbria). The IER was extended to regional museum centres due to the need to test the framework within a context characterised by a higher degree of complexity. In fact, the analysis of financial performance achieved by museum centre branches was difficult due to the absence of some data. In this sense, the impact of the IER has been more relevant in museum centres because the financial reports they prepared were not characterised by this complexity.

The IER is based on IPSAB (international public sector accounting standard board) principles. Specifically, it is inspired by the accrual-based principle, which requires the preparation of records of income items when they are earned, and records of deductions when expenses are incurred (

Anessi-Pessina et al. 2008;

Manes-Rossi et al. 2014).

To achieve a higher degree of transparency in museum financial performance was not the only target for MiBACT. It assigned a further function to the IER related to the need to invest public resources in more effective ways. In this sense, for the first time, the IER introduced the opportunity to assign public resources through the adoption of a meritocratic approach. Definitively, the IER could represent a tool useful to:

clearly inform the managers of the overall performance of the museum;

verify the efficiency and effectiveness of individual resources in the use of resources acquired with the identification, for this purpose, of useful best practices;

realize concrete accountability, ensuring transparency, determining the resources needed to maintain and, if possible, improve the level of activity achieved;

determine the interventions to be implemented in the future, taking into account the specifications situations of each museum reality;

make appropriate comparisons with other similar institutions;

take decisions based on the predictable results and consequent effects on the various stakeholders;

present an easy report to the citizens that is understandable and allows for, among other things, control over the costs of the services rendered to them;

constitute the basis for public financing to be disbursed, considering the performance of each museum.

4. Methodology

The aim is to understand the strategic implications related to the provision of managerial reports within PMs. This is a two-fold analysis, the first relating to the analysis of costs and the second to revenues. The choice to analyse these two financial aspects separately is related to the absence of orientation towards profits by PMs. In this sense, a traditional analysis based on a financial ratio could be negatively influenced by this evidence. Furthermore, the financial analysis will not consider all the multidimensional factors that impact PM performances (

Zan 2000;

Venturelli 2008).

Therefore, our research protocol comprises multiple case studies (

Stake 2013) performed on a sample of PMs that have adopted the IER. The multiple case studies constitute “a special effort to examine something with lots of cases, parts, or members”. Moreover, as suggested by the authors, the adoption of this research protocol favours a deeper understanding of the single dynamics: “One small collection of people, activities, policies, strengths, problems, or relationships is studied in detail. Each case to be studied has its own problems and relationships. The cases have their stories to tell, and some of them are included in the multicase report, but the official interest is in the collection of these cases or in the phenomenon exhibited”. In this sense, IER adoption by different types of museums required the adoption of this method in order to understand the difference between and within cases. In particular, for our purposes, we will evaluate the differences between the fiscal years 2016 and 2017.

Case selection was conducted through a documental analysis (

Bowen 2009) performed on 30 PM websites by two researchers in order to exclude possible bias caused by the complexity of this activity. The selection of the sample has been conducted through the normative analysis of the Franceschini reform (2014–2016) that gave special autonomy to 30 Italian Museums (

Zan et al. 2018). On completion of the research, we identified 5 freely available IERs that represent 16% of our sample. Moreover, as evidenced in

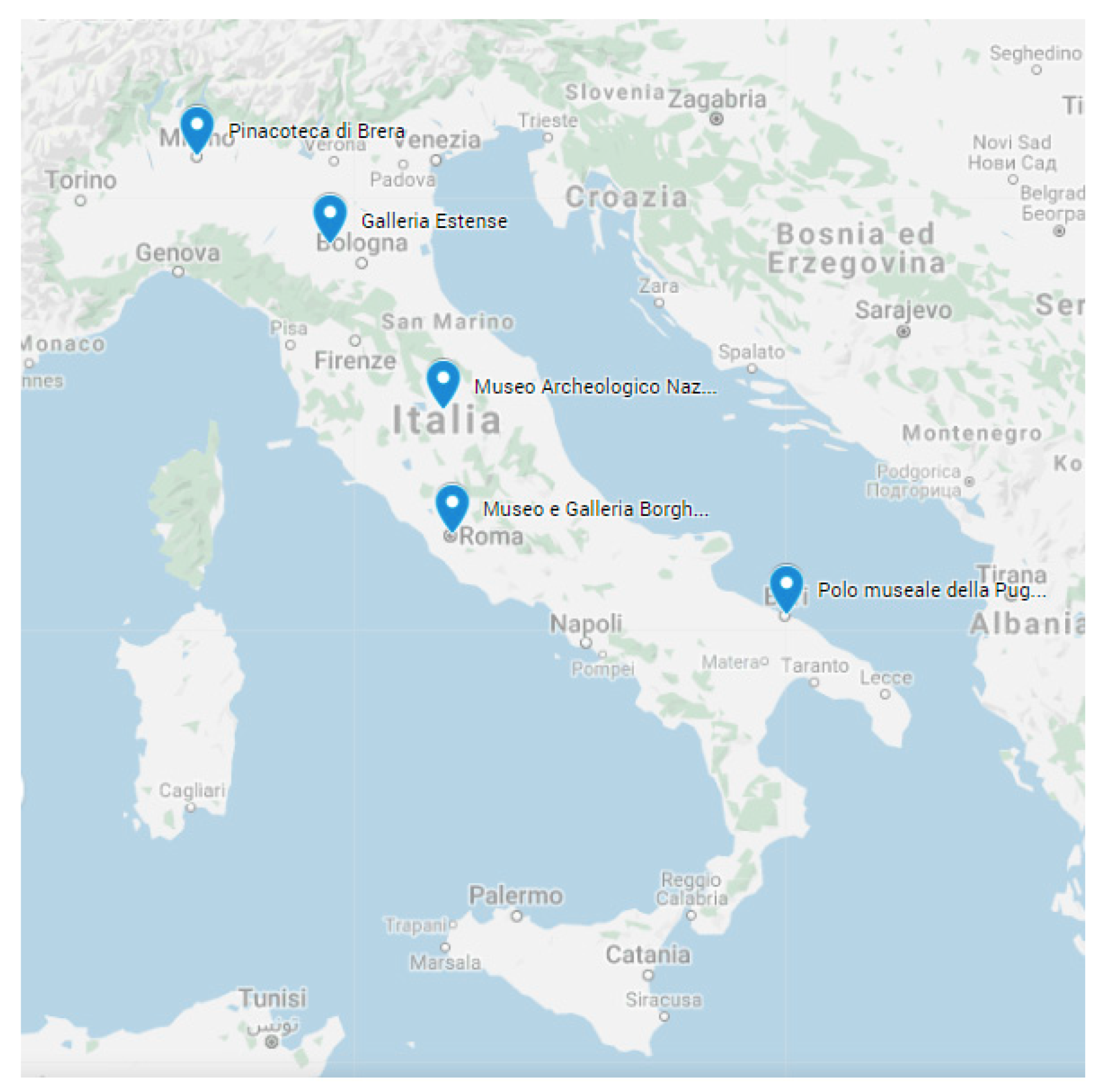

Figure 1, our sample is made up of 3 museums (Galleria Borghese, Pinacoteca di Brera and Gallerie Estensi) and 2 museum centres (Polo Museale della Puglia and Polo Museale dell’Umbria).

The sample is composed of 5 institutions that have agree to the pilot phase (

Table 1). In this sense, the other institutions have not provided voluntarily the IER on their official websites. However, according to

Stake (

2013, p. 22), our sample is adequate to perform a multiple case study analysis because it is larger than 3 and fewer than 14. Furthermore, it is characterised by a high degree of heterogeneity caused by the different characteristics of the 5 PMs (

Boston Consulting Group 2017). In this sense, we respected the methodological protocol of

Stake (

2013, p. 23) that required samples characterised for relevance, diversity and complexity.

5. Case Studies

5.1. Galleria Borghese

The Galleria Borghese is a permanent non-profit institution open to the public, at the service of society and its cultural development. The museum preserves and enhances the Renaissance and Baroque archaeological collections, including through philological and scientific exhibitions. Among the most important initiatives is the establishment of the International Research Centre on Caravaggio.

In 2016, it was the ninth Italian state museum in terms of the number of visitors (525K visitors) with an average age of 50–70 years, and the third Roman museum in terms of affluence.

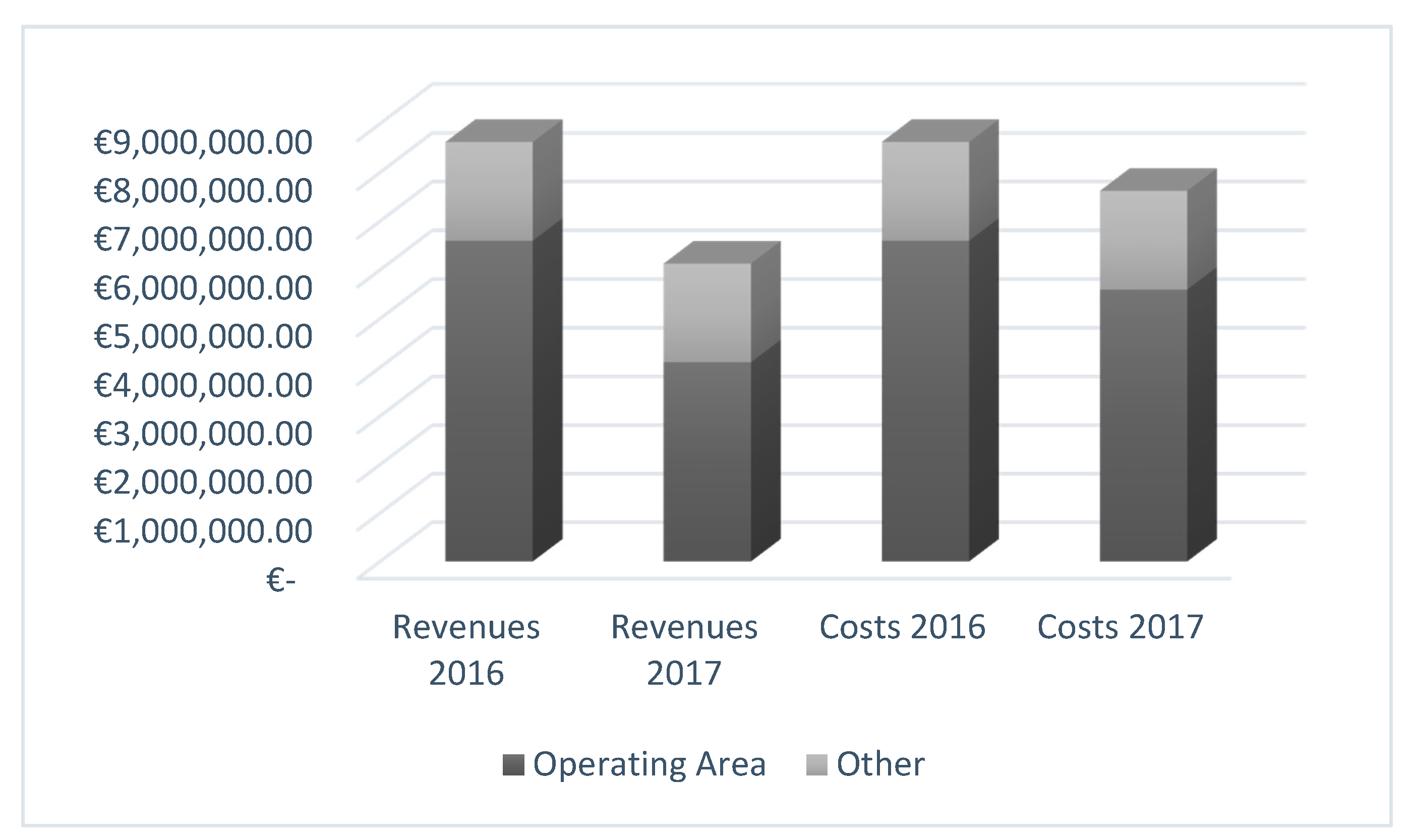

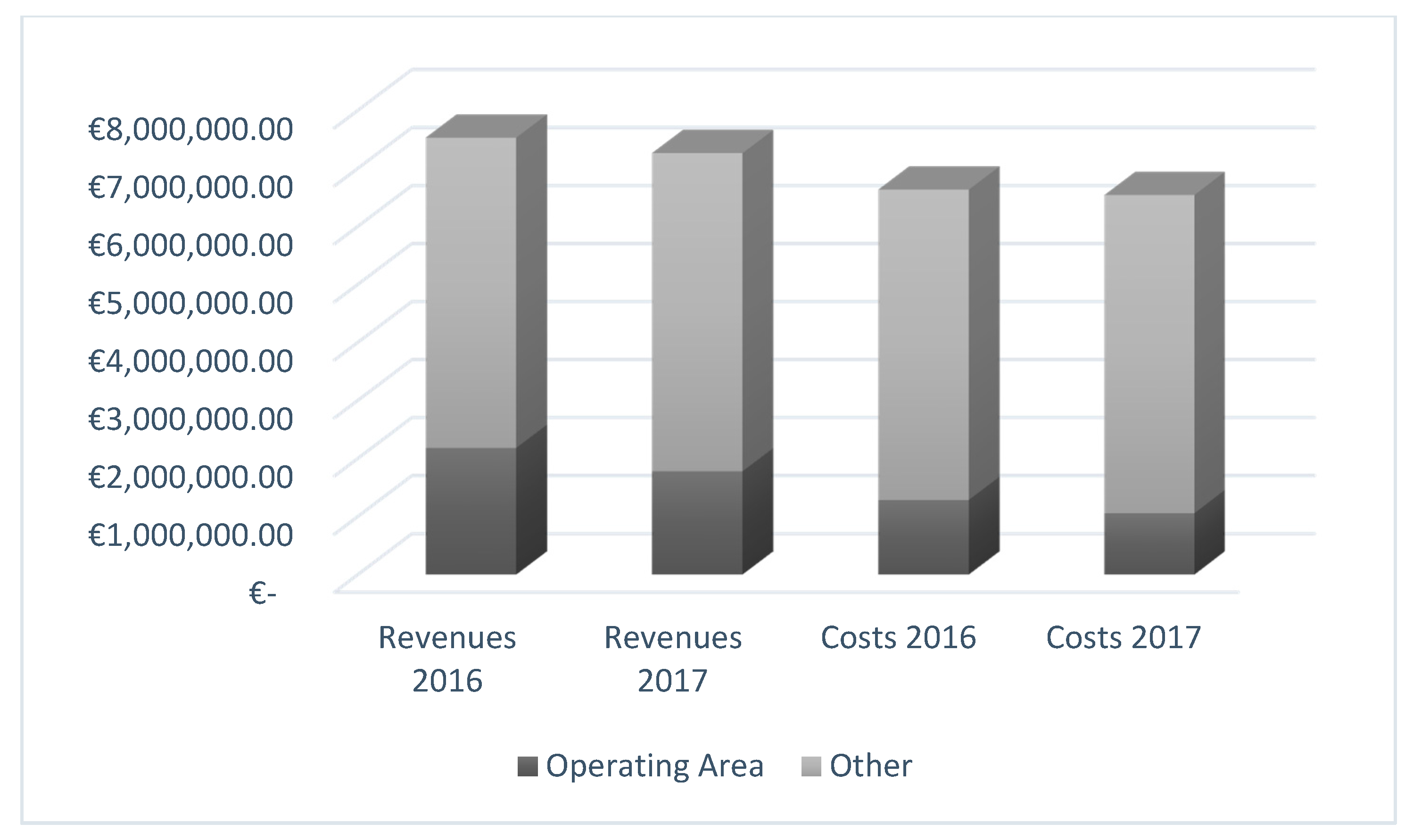

Revenues in 2016 were around €8.6 million (

Figure 2). The 52.2% from internal revenues which included revenues from ticket sales, additional services, and concession fees. Further, 47.1% from public transfers were transfers from the general directorates of the MiBACT, from the expenses incurred by the general management based on the costs generated by the museum activity, and by transfers from other public administrations. A further 0.6% of revenues were contributions from individuals that included donations and sponsorships. With reference to the itemisation of costs of approximately €8.6M, 77.2% were structural costs, which included maintenance, utilities, the purchase of consumer goods and personnel, and 13.8% are costs for institutional activities: costs for teaching, cataloguing, promotion, organization of exhibitions and events, installations and restorations. The remaining 9% is made up of transfers to the state, which include the portion of the ticket income destined for the support fund of the institutions and places of state culture.

Regarding the year 2017, the preparers have estimated a negative managerial result caused by an overall revenue decrease of 37.80%. Specifically, this contraction is due to the absence of financial contributions from public institutions other than MiBACT. However, according to the prudential principles, the managers have reduced some costs in their budget, in particular, those related to the provisions of the fund.

5.2. Pinacoteca di Brera

The Pinacoteca di Brera is a state museum that welcomed over 370,000 visitors in 2017, an increase of 8.7% compared to the previous year, and an average annual growth rate of 10.6%. In 2015, thanks to the EXPO, an international fair held in Milan, this reached 21%, however, in absolute terms compared to 2013, there were over 120,000 more visitors to the museum. In 2017, it welcomed around 1000 visitors a day on average.

In the year examined, the number of paid full and reduced entrance tickets increased by 13%, and free entry tickets increased by 16%. Evening openings and free sunday entry have certainly contributed to the increase in the number of visitors.

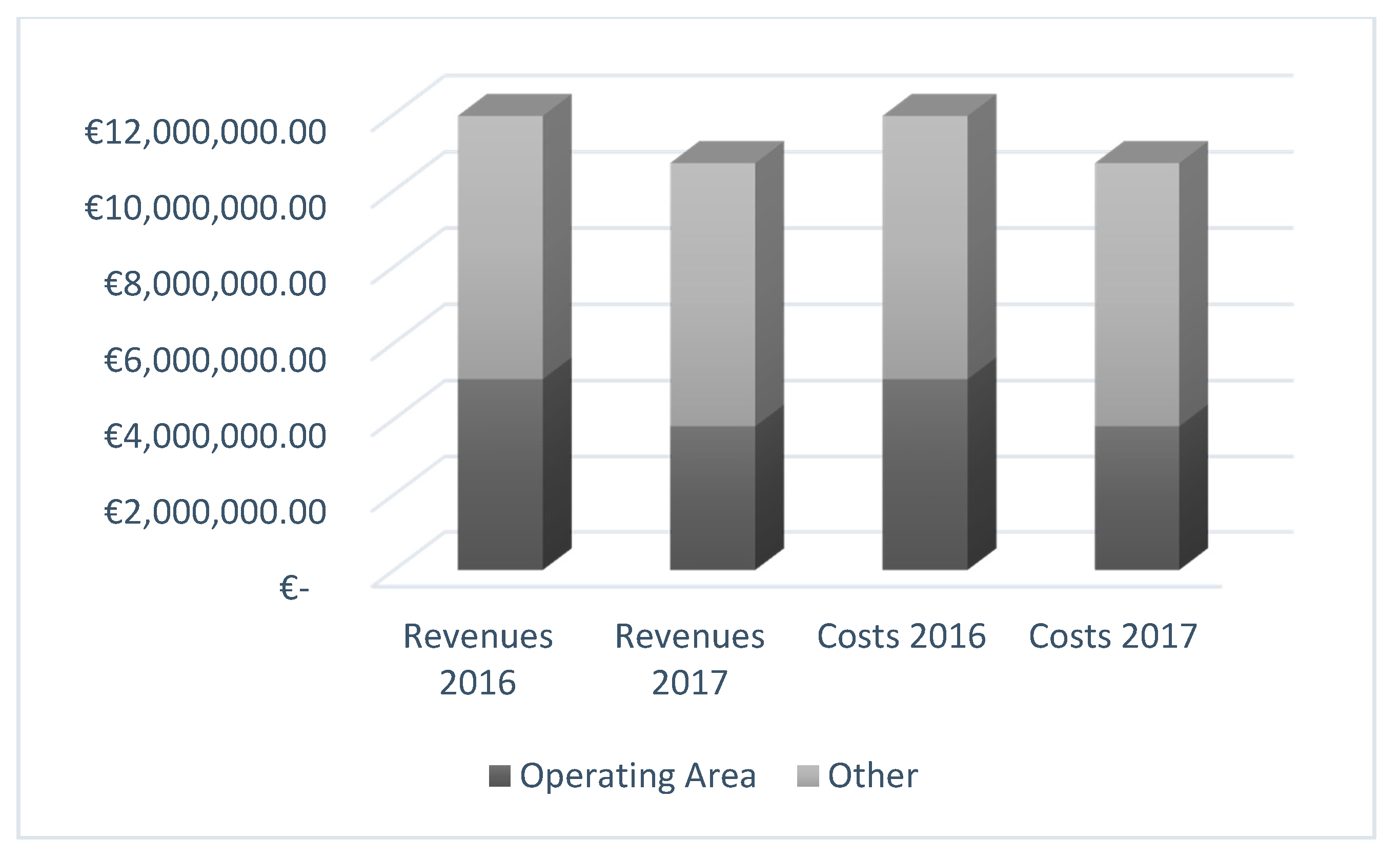

In 2016, there were 343,000 visitors. Revenues of around €12 million were derived from 78.6% public transfers, 16.1% from internal revenues, and 5.3% from private contributions. Costs amounted to around €12 million, and consisted of 88.8% in structural costs, 9.5% of costs for institutional activities, and 1.8% of transfers to the state (

Figure 3).

In 2017, the strategic approach employed by the managers of the Pinacoteca di Brera achieved an adequate performance despite the fact that MiBACT reduced its contribution by 46.05%. This loss was covered by an increase in ticket sales of 15.82%. Therefore, due to its strategic approach, the Pinacoteca di Brera achieved the highest degree of independence from MiBACT.

5.3. Gallerie Estensi

The Gallerie Estensi preserves the history and culture of a vast geographical area. The museum represents a territorial network with a diversified cultural offering. Created from the amalgamation of various institutes, the museum has gone beyond geographical and administrative constraints to become the unique and purposeful spokesperson for a shared cultural identity.

The galleries are, therefore, a place of socialization, training, and exchange between the cities of Ferrara, Modena, and Sassuolo, but also a centre for research and the dissemination of knowledge through the organization of exhibitions, events, and conferences that provide a great attraction for the public. The networking of resources and the use of digital humanities has facilitated revenues of 95.9% from public transfers, 1.6% from internal revenues, and 2.5% from private contributions. The costs amounted to approximately €8.1 million and included 89% in structural costs, 10.6% in institutional activities, and 0.4% in transfers to the State.

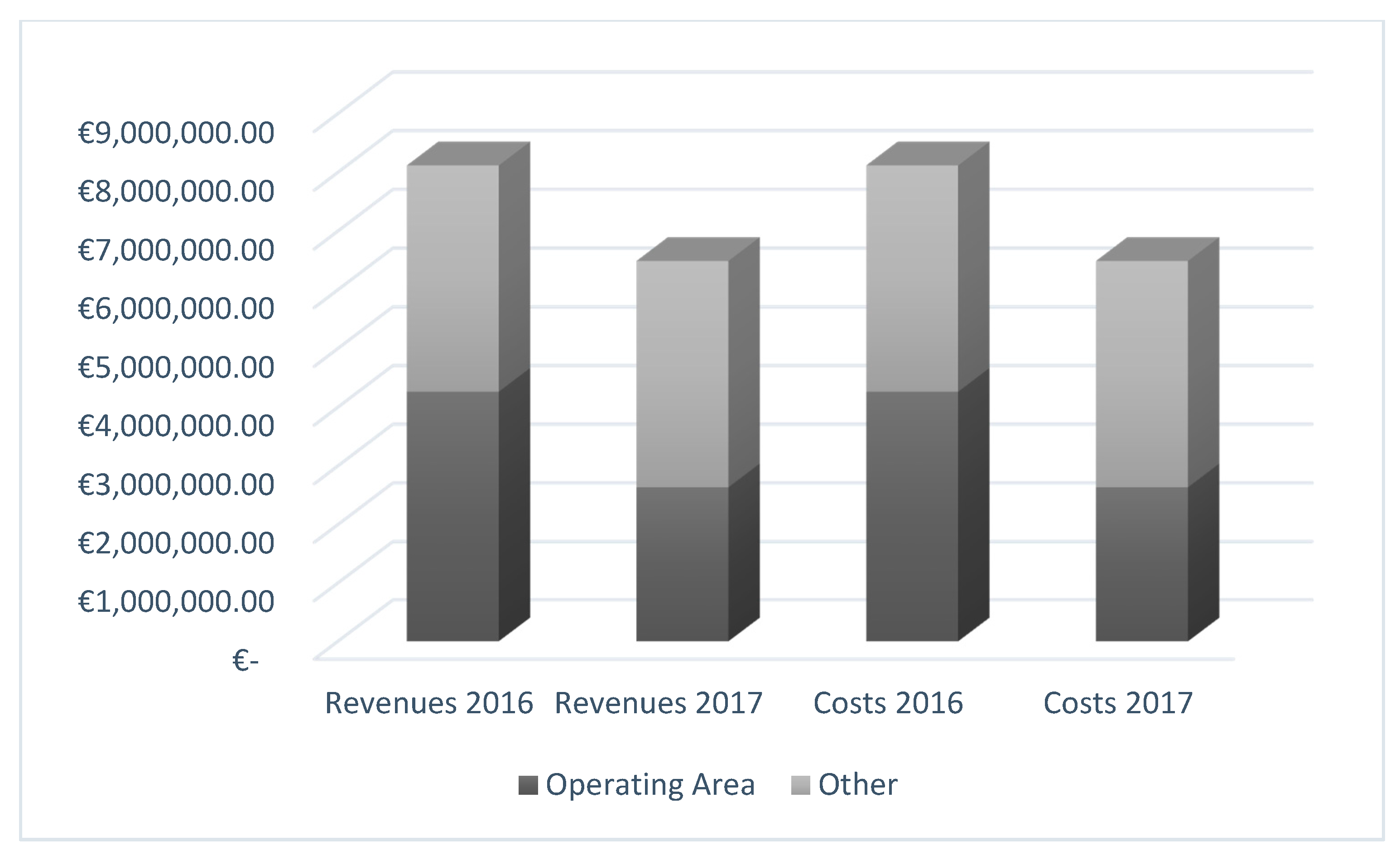

In 2016, there were 110,000 visitors. Revenues of around €8.1 million consisted of 95.9% from public transfers, 1.6% from internal revenues, and 2.5% from private contributions. The costs amounted to approximately €8.1 million and included 89% of structural costs, 10.6% in costs for institutional activities, and 0.4% in transfers to the State.

In 2017, the preparers estimated an operating revenue reduction of 38.12%. This contraction was due to the absence of donations from private contributors and by fewer contributions from MiBACT (

Figure 4). On the other hand, the museum reduced it’s costs related to general expenses. The IER analysis reveals how managers adapted their behaviour to the new scenario. Moreover, in that period, the Gallerie Estensi invested €250,000 in cultural heritage. In this sense, despite the lack of resources, the museum defended the value of its heritage assets.

5.4. Polo Museale della Puglia

The Polo Museale della Puglia, a peripheral organ of the Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Activities, operates in the regional territory with the aim of enhancing and making museums, monuments, and state works accessible to the public. It facilitates a continuous dialogue between state and local authorities, between different public and private museums in the area, promoting the establishment of the regional museum system, and ensuring an integrated offering of high cultural quality, working to define the strategies and common goals for valorisation.

It consists of several museums, namely the National Archaeological Museum of Altamura, the Swabian Castle in Bari, the National Gallery in Puglia, “Girolamo and Rosaria Devanna” in Bitonto, the National Archaeological Museum of Gioia del Colle, the National Jatta Museum of Ruvo di Puglia, the National Archaeological Museum ‘Giuseppe Andreassi’ and the Archaeological Park of Egnazia, the Castel del Monte in Andria, the Palazzo Sinesi in Canosa di Puglia, the Swabian Castle in Trani, the National Archaeological Museum of Manfredonia, the Angevin Castle inCopertino, and the Church of San Francesco della Scarpa in Bari.

In 2016, the Polo was visited by 530,000 visitors. Revenues of around €7.5 million consisted in 87.1% from public transfers and 12.9% from internal revenues (

Figure 5). The costs, on the other hand, amounted to approximately €6.6 million, of which 97.3% were structural costs and 2.7% transfers to the state. The managerial result has been positive with a net increase of €896,489.

The approach followed for the year 2017 was similar. The revenues equalled €7.2 million and the costs were approximately €5.84 million. In this sense, despite a reduction, the managerial result has been positive and equal to €721,000.

5.5. Polo Museale dell’Umbria

The Polo Museale dell’Umbria ensures a synergy between the regional cultural institutes and places of interest. Its aim is to promote defining strategies and common objectives in relation to the territorial area of competence, as well as the integration of cultural activities and, in conjunction with the regional secretary, of cultural tourist itineraries.

The Polo is made up of the National Archaeological Museum of Umbria, the National Archaeological Museum and the Roman Theatre in Spoleto, the National Archaeological Museum of Orvieto, the National Museum of the Duchy of Spoleto and Rocca Albornoziana, the Tempietto sul Clitunno, the Palazzo Ducale in Gubbio, the Bufalini Castle and the Villa del Colle del Cardinale.

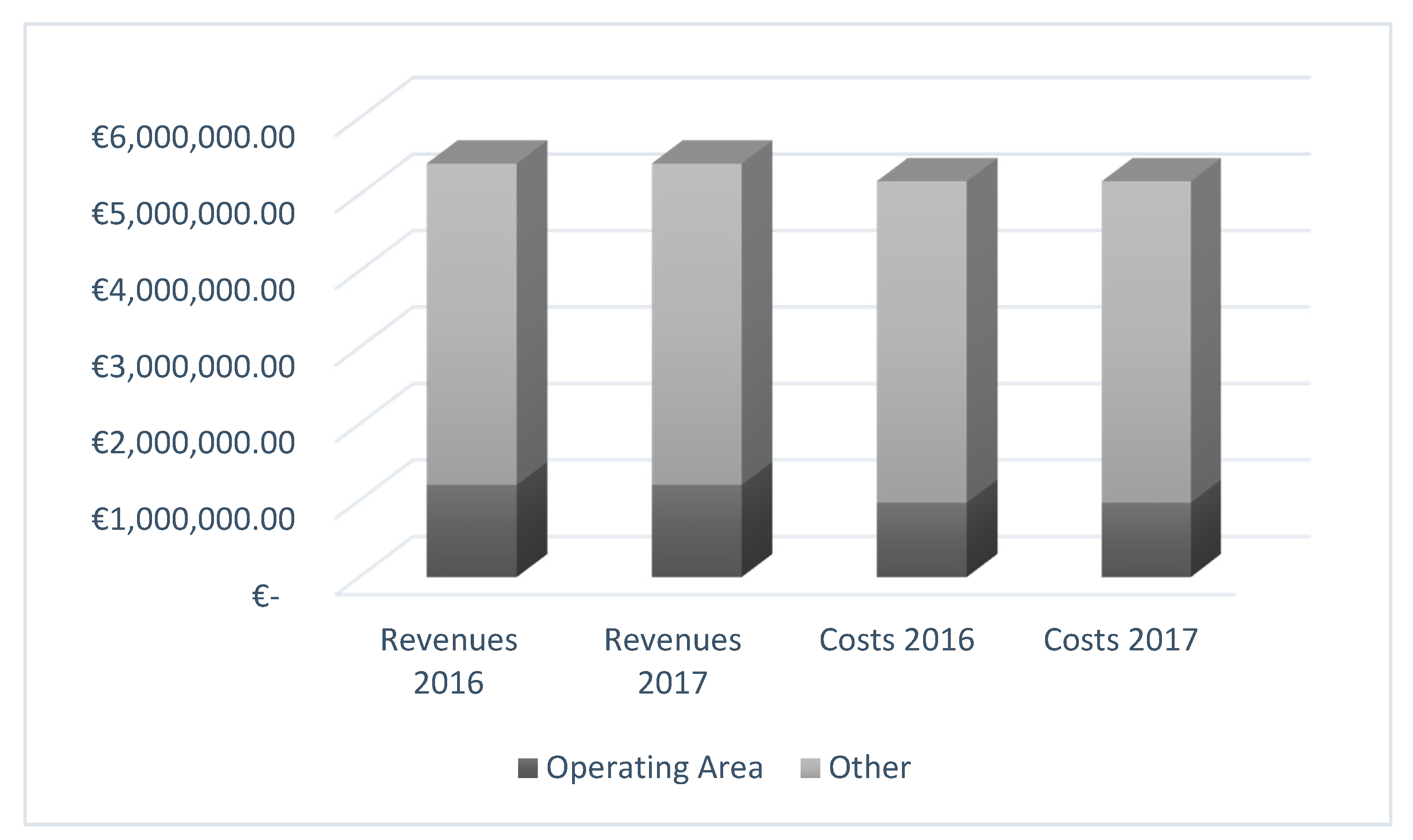

In 2016 there were 144,000 visitors. Revenues amounted to approximately €5.2 million, 95.9% of which was from public transfers and 4.1% from internal revenue (

Figure 6). The costs were approximately €5 million, of which 98.6% were structural costs, 0.5% were costs for institutional activities, and 0.8% were transfers to the state.

For the year 2017, the preparers estimated the same results. In this sense, the fact that there were no differences between the two periods studied revealed the adoption of a prudential approach by preparers.

6. Discussion

The documental analysis revealed several useful insights for policy makers to evaluate a possible evolution inspired by the need to increase the degree of managerialism within the Italian Museums.

The analysis performed on the three museums (Galleria Borghese, Pinacoteca di Brera and Galleria Estense) revealed several differences between these institutions.

The main difference observed was in the negative managerial results expected for Galleria Borghese in 2017. More specifically, IER analysis revealed how the result was due to the lack of contributions from public sector institutions. Moreover, the analysis performed on the costs revealed an increase in expenses for promotional activity and administrative costs equal to 108.81% and 119.55%, respectively. This demonstrated how the adoption of the IER contributed to understanding the phenomenon.

On the other hand, the Pinacoteca di Brera and the Galleria Estense were characterised by an adequate degree of revenue in both periods. Furthermore, the IER analysis revealed how the Pinacoteca di Brera reduced the impact of the negative effects related to the lower contribution from MiBACT by increasing the revenue from tickets. In this sense, the Pinacoteca di Brera demonstrated better managerial ability during the period observed.

The results related to the two museum complexes revealed how the institutions achieved positive managerial results during the two periods observed. However, the IER analysis provided an interesting insight into the institutions.

The Polo Museale della Puglia demonstrated positive managerial results both in 2016 and 2017. Moreover, the comparison between 2016 and 2017 revealed how the Polo Museale della Puglia compensated for the lower contribution from MiBACT through ticket sales. Furthermore, analysis of the costs revealed how the institutions decreased the costs related to staff and consumer goods. On the other hand, it increased the transfer to MiBACT, and the costs related to taxes. In this sense, the Polo Museale della Puglia activated a virtuous process of alignment to managerial principles.

However, the documental analysis revealed some criticisms related to the IER of the Polo Museale della Puglia. In fact, the preparers highlighted the difficulty in estimating some values due to the absence of analytical information about the market operation performed by the subsidiaries.

Finally, the analysis of the Polo Museale dell’Umbria has highlighted how preparers have substantially transposed the estimation of the value for 2016 to 2017. In this sense, this evidence confirms how the management processes that characterise public entities show a high degree of heterogeneity between institutions.

7. Conclusions

In Italian museums a profound evolution is underway that has led to some radical changes. From static entities, they have become dynamic institutions characterized by an independent juridical form in terms of scientific and administrative activity (

Milone 2004;

Venturelli 2007). Furthermore, the prior evidence collected about Italian Museums has highlighted the existence of several differences between visitors (

Vecco and Srakar 2018). In this sense, managing the complexity represents one the of the main criticism for public managers.

The evolutionary path is essentially due to the inescapable need to provide adequate answers to the different and growing needs expressed by the governing bodies, stakeholders, and legislators (

Herguner 2015). In particular, appropriate regulatory measures have been issued in recent years. Thanks to these, and in contrast to the past, PMs are now characterised by a high degree of managerial knowledge. This organizational change has favoured the use of business strategies and methodologies that, with best practices, aim to pursue the optimal use of the cultural heritage.

The IER represents an innovative tool, with internal implications for the monitoring and timely evaluation of activities and results for each museum, stimulating the staff who work there with different levels of responsibility. At the same time, it is believed that appropriate external communication with various stakeholders will induce them to consciously consider their interventions, possibly to increase them and make valid comparisons with similar institutions.

The policy implication related to our study is represented by the opportunity to introduce new forms of regulation in order to define more effective strategies within the public sector (

Rosenstein 2010). As demonstrated by our results, each museum is characterised by its own peculiarities in terms of costs and revenues. The mandatory adoption of IER for PM could drive the introduction of new strategies inspired by the need to achieve the highest degree of financial sustainability. Moreover, the IER could fill the informative gaps caused by the adoption of traditional financial reports. In fact, as evidenced, the traditional accounting form does not provide specific information about the real performance of the institutions due to the central role covered by the financial contribution provided by the state (

Fissi et al. 2018). In this sense, the IER describes with a high degree of accuracy the origin of each revenue and cost related to the museum. In fact, traditional financial reports do not provide any specific information about the causes and the consequences related to the adoption of new strategies. According to this evidence, managers could perform a joint analysis incorporating museum performance and external factors such as the environment and tourist flow (

Vecco et al. 2017). Furthermore, the comparability of the IER could favour the comprehension of economic dynamics over the time.

The managerial implications of our study are represented by the possibility for private museums to adopt reporting systems similar to the IER. Specifically, the adoption of similar reporting systems will help us to understand the differences between the private and public sectors. Moreover, analysis of the performance achieved by PMs that operate in the same context could represent a benchmark for entrepreneurs interested in investing in heritage enterprises.

The limitation of our study is the short period of analysis. Future research could fill this gap by extending the period of analysis. Furthermore, the adoption of quantitative methods in order to understand the effectiveness of the IER could represent a useful tool to understand the financial dynamics related to its adoption.