In Search of Employee Perspective: Understanding How Lithuanian Companies Use Employees Representatives in the Adoption of Company’s Decisions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Participation of Employee Representatives in the Adoption of Company’s Decisions: Notions and Access to Researches

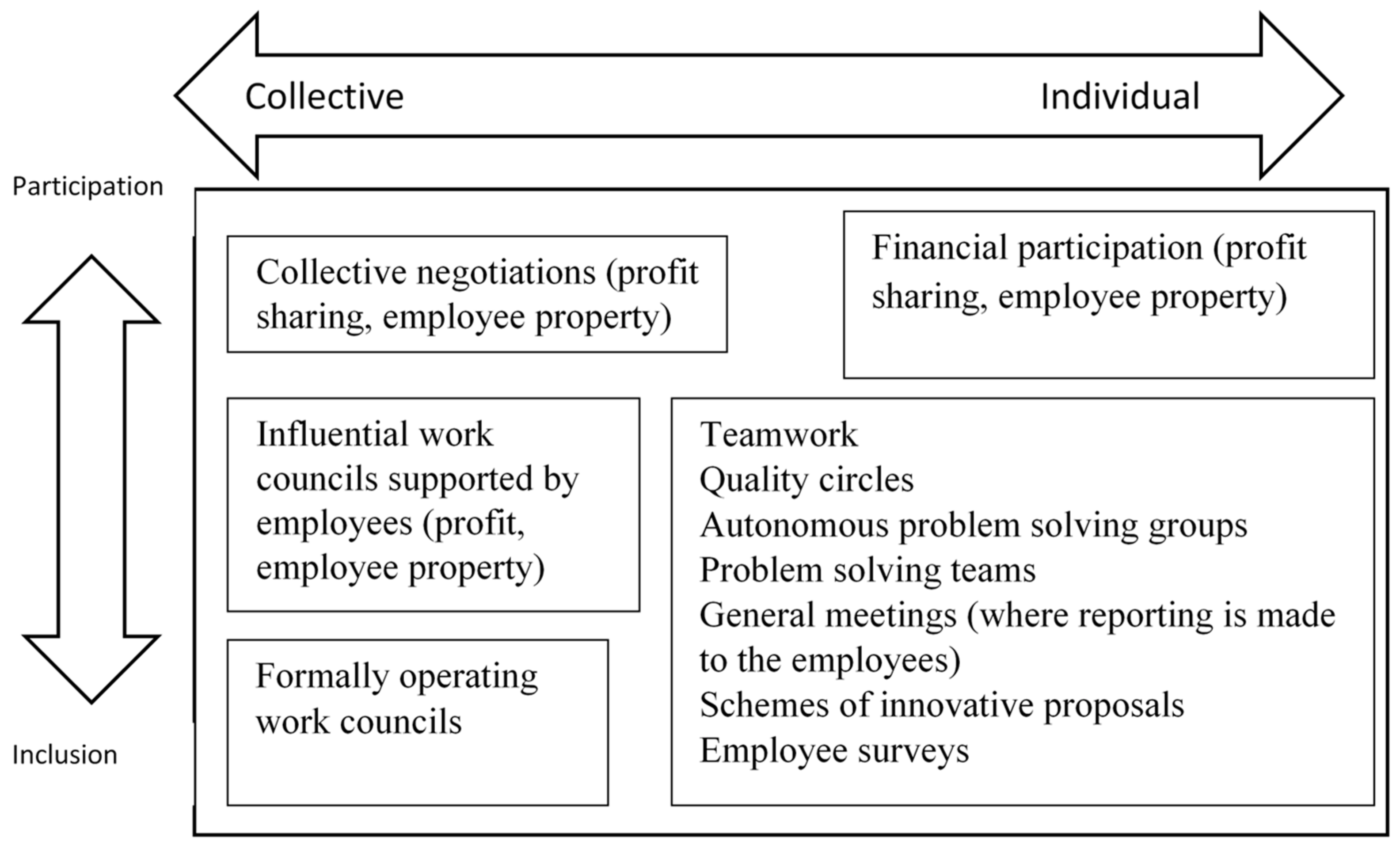

3. The Forms of Employee Participation in the Decision Adoption of the Company: Direct and Indirect Participation

4. Collective Indirect Forms of Employee Participation

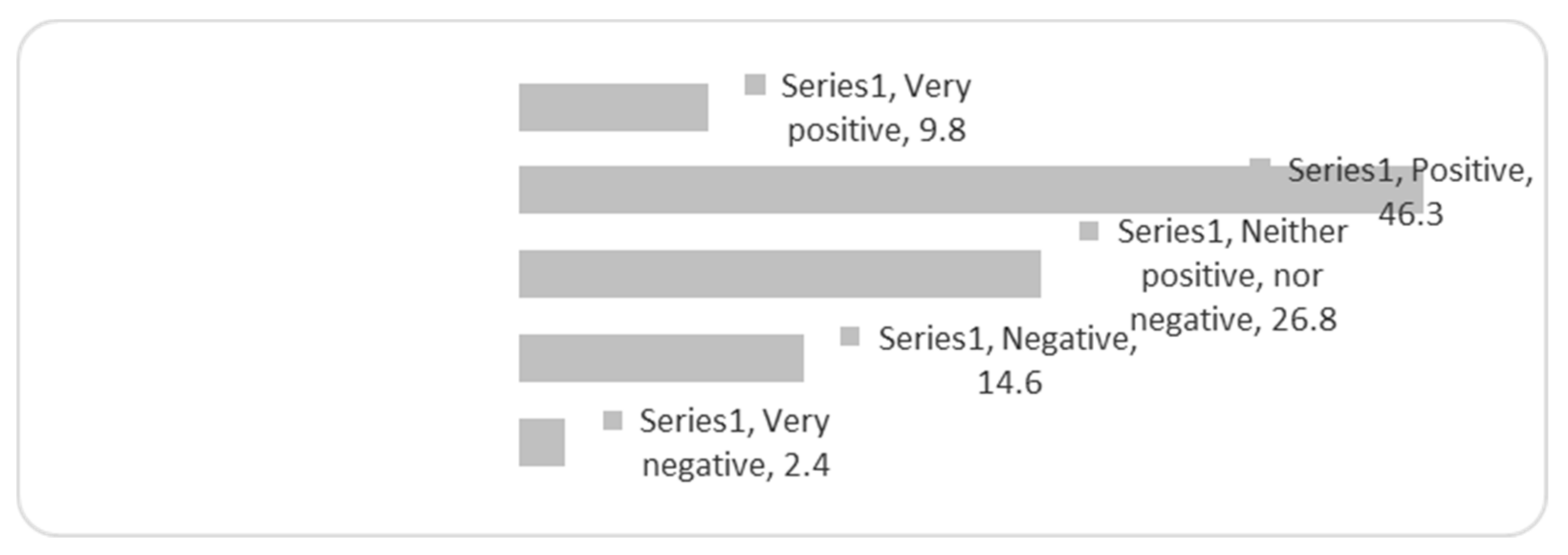

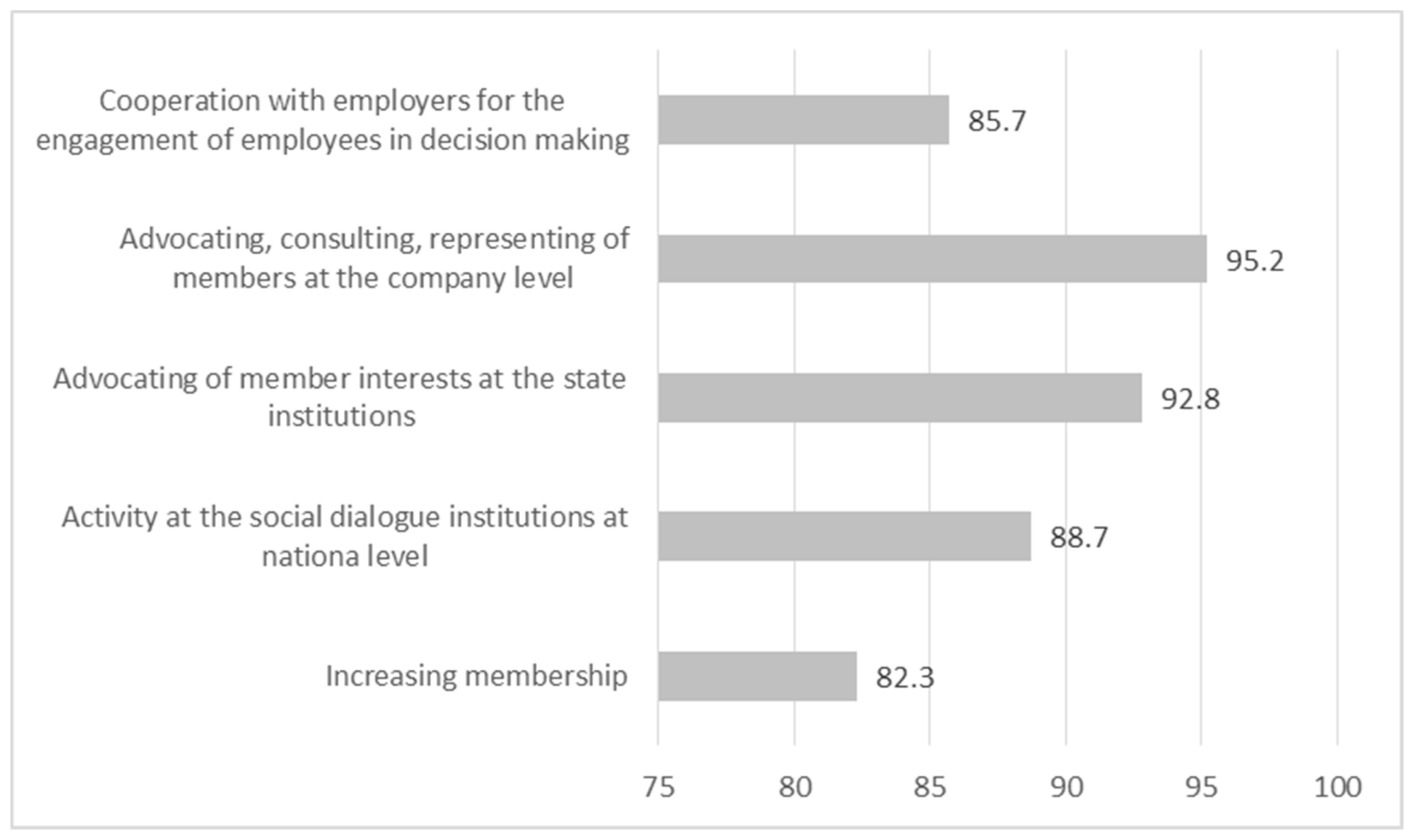

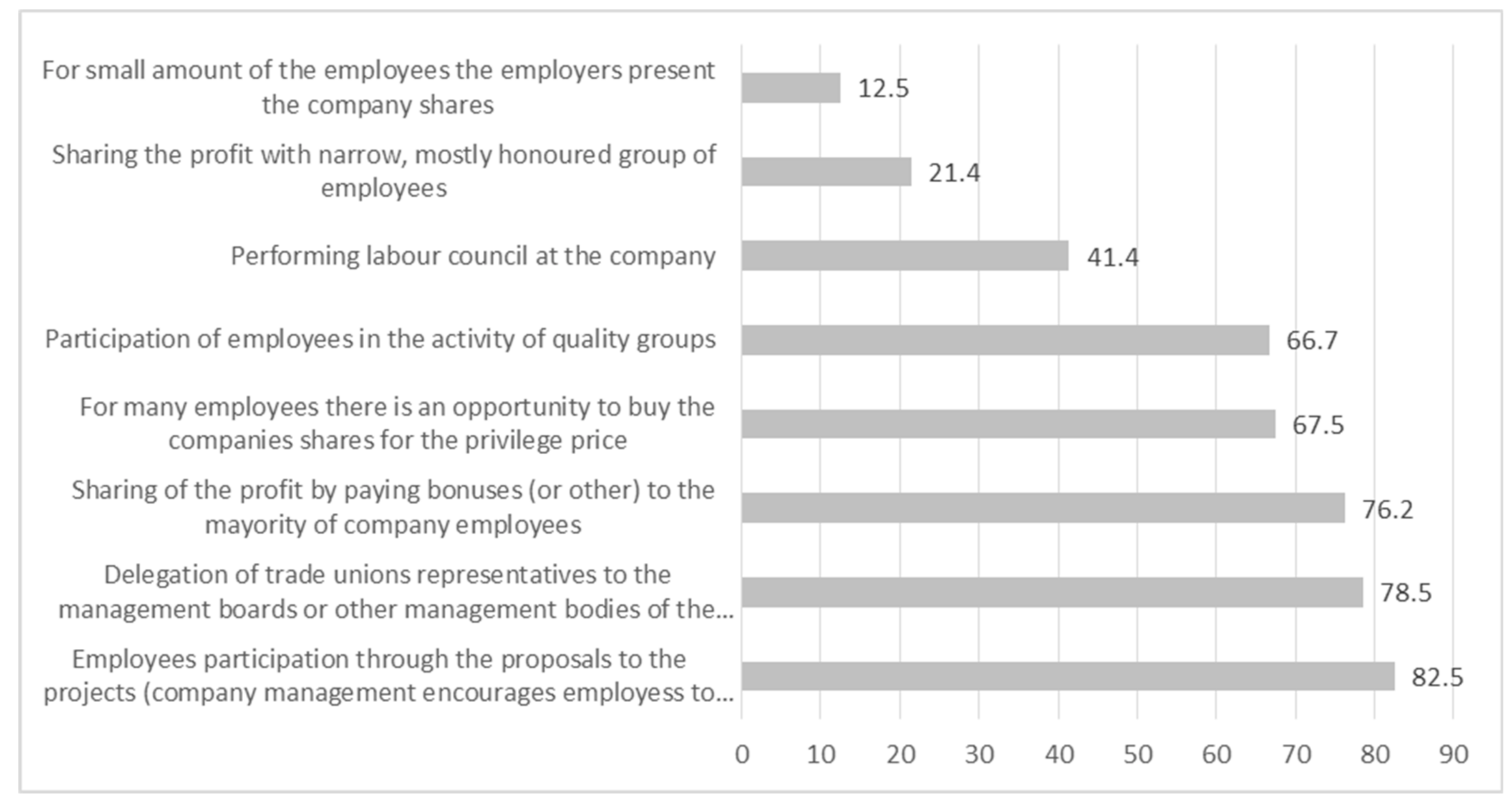

5. The Methods and Procedures

6. The Points of View of Employee Representatives towards the Employee Participation in the Adoption of Companies’ Decisions

6.1. The Marginalization, Avoidance or Effective Supplementation of Employee Agencies

Talking and cooperation is needed. As I understand, the employers fear the trade unions, while the trade unions see the employer as a potential villain. However, of course, decisions exist. Talking is needed. There are many examples and variants. Most of them are bad, but there are good examples as well. I have them. For example, there is a logistics company “Transtira” [company case was offered]. There, the trade union works with the employer based on the principle of mediation. All of the issues are forwarded to the trade union and it refines them to real ones, not emotional ones. Later on, there are tries to solve them with the manager.(interview with NAC4)

If the collective agreement exists, then its result is financial participation, allocation of profits and shares. If everything would go through the collective agreement, everything would be splendid. However, if they there… they share as profit anything. Never will a capitalist employer share their profits, if the said employer will not be forced to do this. The employer is big altruist. Here, exceptional cases are possible. Maybe, I’m not saying. Maybe one or couple of employers are different.(interview with NAC5)

They look to a trade union with white eyes [talking about the points of view of a part of employers towards cooperation]. They do not understand, pre-conditions that the trade unions is a conflict is valid for them. Maybe, this is coming from TV, media, maybe from a tradition. They do not understand what a dialogue is.(interview with ŠAK2)

Rarely there is information about financial success. There are few employers, who understand that this is teamwork; it won’t be another way. There are few practices of this kind. They do exist, but they are few. Well…As I’ve said, negotiations regarding wage, size of it…it is the most complex question. Even though, now, the issue of wage is supposed to be a part of the collective agreement. However, this is very hard to achieve. For example, today, we had two negotiations and they all went really difficult. Believe me. These are negotiations with international companies, and when negotiations are needed to be had with local companies… Believe me, negotiations are foreign language to them. An international company has its own standards, code of ethics and the collective agreements must be signed in accordance to those documents. […] Yeah, yeah, they must act more respectably and less aggressively.(interview with ŠAK1)

Where there is foreign capital, they bring it with them. They do not want to lose their positions. Their parent companies with their own policy exist. These companies look at it a bit differently. I remember being at “Elemenhorster”. The manager says that we give the employees this and this. Nevertheless, this was the chairperson’s issue. This I can tell. There was a stubbornness of the trade union’s chairperson; he simply said how it’s going to be and it was all over. Another matter is in the furniture sector. There talking and giving exist. There good conditions and nourishment, work safety and a part of teamwork exist. Nevertheless, here everything comes from the West. Those companies implement their own culture. For our people, as I’ve mentioned…Those with “full stomach” are good [talking about Lithuanian capital companies, which are entrenched in the market and are financially stable]. Those, who do not need to catch-on, those, who have branches in foreign countries. Those look at the issue more simply and you understand that then you can talk about the so-called social aspect. You cannot talk with those small ones, who work during weekends and pay wages under the table.(interview with ŠAK2)

6.2. The Provisions Regarding the Inclusion of Employees into Teamwork and Collective Consulting

“Within “Lietuvos Energija” this is indeed done, but not imitated. The culture in electrical companies is a bit higher than in industrial ones. Maybe, people that are more intellectual work here…I do not know precisely why that is. Nevertheless, there are talks with the employees of the lowest tier. Well, this is done. […] I very much support this, if this is done honestly and there is feedback. The process must be two-fold; if this is done sincerely, then the result is splendid. The atmosphere of the collective itself is good. The employees know that an employee after talking with a higher-level manager may solve the problem. In “Lietuvos Energija” it became some sort of a manic thing for employees to propose how to solve certain problems. They offer many solutions; at first, this seemed like a game, but now it became a constant practice. The employee must propose a couple of novelties on how to enhance the process in order for to expedite it. They think things up and really do save money for the company. This is beneficial in a financial sense as well. Maybe, this can be applied not for all companies, but there are examples in the company “Lietuvos energijos skirstymo operatorius”, where 2.5 thousand of employees’ work. They generate benefit in Lithuania. They [the companies] even publicly announce how many ideas were implemented and accepted in order to turn them in to reality. […] Well, somehow there were tries [talking about the inclusion of questions associated with employment relations in to this kind of participation form], but it failed…[laughs] We have a niche and are closer to employees. The managers, who are smarter and cannier, and want to know about the employees, cooperate with us.[interview with NAC5]

“These are issue solving teams shaped in our company. They meet every month and discuss the issues of manufacture and sales. There, they in a bit different angle discuss that, which we talk about on Monday meetings. […] Some proposals find their way with great difficulty. For example, regarding the electronic catalogue of the company for the suppliers. Many times, the managers went to the director… and the head of the marketing proposed. […] No, there, the questions of employees are not the most important. Maybe, a couple of times they were discussed. Most often, the employees go to their managers, direct managers or general manager for negotiations. Discussions were during annual evaluation. […] Yes, teamwork regarding sustainability were organized. The corporation [the name is mentioned] implements the sustainable philosophy and laid down from above the requirements for daughter companies. We had discussions with the invited expert. I do not know, mostly about environmental safety, unused raw materials and…While sitting in those meetings I was simply nervous. Complete waste of time.(interview with DT1)

“Somehow, this is done. We have quarterly meetings. There, everything is discussed on where everything is delivered, but the employees cannot ask questions. As if everyone lacks the time. We have boxes in our company where the proposals are incited to be submitted and they are evaluated. I do not know how they evaluate them […] I had to conduct a survey. We’ve conducted it a couple of years in a row. The employees and their issues are not solved. Moreover, they petitioned… There is a procedure that you may address the direct manager, if he/she does not solve the issue, then you can address the higher manager. However, the employees are deeply chagrined, because their issues are not solved directly. […] Simply we’ve discussed the problems via survey. We try to accumulate as many problems as we can and then we address the managers of the company. […] The manager of the factory has recently started to convene the meetings with the workers of sub-divisions, shifts and lines [there are talks that these meetings were decided to be convened due to negative audit results of the corporation regarding inappropriate climate. The audit results were submitted with comparative results of the indicators of all “daughter” companies. The audit was conducted after the employees were questioned]. In truth, I have yet to participate in such a meeting. I don’t know how it will be. Of course, there will be people, who are afraid to express themselves. In addition, there are talkative people. Nevertheless, somehow, the results are not really seen. […] I would want a more active inclusion. Every time when you find-out about the meeting you have ask to be let it as a chairperson. Well… this is how it is done. About a third of employees are trade union members. Such is the point of view when the minority of trade union (a third) participates. The rest do not need the trade union nor do they support it. As if, a mediator is not necessary. This is felt […] What I don’t like the most is that there are unilateral decisions regarding inclusion. They do what is mandatory, but everything else it is difficult for them. They decide and propose. I would want some sort of a mutual link, a dialogue.(interview with ĮM1)

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References and Note

- Barry, Michael, and Adrian Wilkinson. 2016. Pro-social or pro-management? A critique of the conception of employee voice as a pro-social behaviour within organizational behaviour. British Journal of Industrial Relations 54: 261–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blažienė, Inga, and Boguslavas Gruževskis. 2017. Lithuanian Trade Unions: From Survival Skills to Innovative Solutions. In Innovative Union Practices in Central-Eastern Europe. Edited by Magdalena Bernaciak and Marta Kahancová. Brussels: European Trade Union Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Blyton, Paul, and Peter J. Turnbull. 1998. The Dynamics of Employee Relations. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Brewster, Chris, Richard Croucher, Geoff Wood, and Michael Brookes. 2007. Collective and individual voice: convergence in Europe? The International Journal of Human Resource Management 18: 1246–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Civinskas, Remigijus, and Jaroslav Dvorak. 2017. New social cooperation model in service oriented economy: the case of employee financial participation in the Baltic states. Engineering Management in Production and Services 9: 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crouch, Colin. 2017. Membership density and trade union power. Transfer: European Review of Labour and Research 23: 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Torre, Edoardo. 2018. Collective voice mechanisms, HRM practices and organizational performance in Italian manufacturing firms. European Management Journal 37: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Detert, James R., and Linda Klebe Treviño. 2010. Speaking up to higher-ups: How supervisors and skip-level leaders influence employee voice. Organization Science 21: 249–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dvorak, Jaroslav, Raita Karnite, and Arvydas Guogis. 2018. The Characteristic Features of Social Dialogue in the Baltics. Socialinė Teorija, Empirija, Politika ir Praktika 16: 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurofound. 2015. Third European Company Survey: Direct and Indirect Employee Participation. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar]

- Eurofound. 2016. Mapping Key Dimensions of Industrial Relations. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar]

- Eurofound. 2018. Measuring Varieties of Industrial Relations in Europe: A Quantitative Analysis. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. 2002. Report of the High-Level Group on Industrial Relations and Change in the European Union. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. 2017. Commission Recommendation Establishing the European Pillar of Social Rights. Brussels: European Commission, April 26. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. 2018. COMMISSION STAFF WORKING DOCUMENT IMPACT ASSESSMENT Accompanying the document Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council amending Directive (EU) 2017/1132 as regards the use of digital tools and processes in company law and Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council amending Directive (EU) 2017/1132 as regards cross-border conversions, mergers and divisions. Brussels: European Commission, p. 63. [Google Scholar]

- European Parliament and Council. 2002. Directive 2002/14/EC 11 March 2002 establishing a general framework for informing and consulting employees in the European Community. Official Journal L080: 29–33. [Google Scholar]

- Gollan, Paul J. 2010. Employer Strategies towards Non-Union Collective Voice. In The Oxford Handbook of Participation in Organizations. Edited by Adrian Wilkinson, Paul J. Gollan, Mick Marchington and David Lewin. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gollan, Paul J., and Ying Xu. 2015. Re-engagement with the employee participation debate: Beyond the case of contested and captured terrain. Work, Employment and Society 29: NP1–NP13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heery, Edmund James. 2015. Frames of reference and worker participation. In Finding A Voice at Work?: New Perspectives on Employment Relations. Edited by Stewart Johnstone and Peter Ackers. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hyman, R. 2018. What future for industrial relations in Europe? Employee Relations 40: 569–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnstone, Stewart, and Adrian Wilkinson. 2016. Developing Positive Employment Relations: International Experiences of Labour–Management Partnership. In Developing Positive Employment Relations. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman, Bruce E. 2015. Theorizing determinants of employee voice: An integrative model across disciplines and levels of analysis. Human Resource Management Journal 25: 19–40. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Jaewon, John Paul MacDuffie, and Frits K. Pil. 2010. Employee voice and organizational performance: Team versus representative influence. Human Relations 63: 371–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozłowski, Maciej. 2014. The Relationship between Workers’ Financial Participation in Companies and Economic Results. Comparative Economic Research 17: 167–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurėnas, Vaidutis. 2017. Spartėjančios visuomenės politinis režimas. Klaipėda: Klaipėdos universiteto leidykla. [Google Scholar]

- Lulle, Aija. 2013. Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania—Labour relations and social dialogue. In Regional Project on Labour Relations and Social Dialogue. Stockholm: Confederation of Swedish Enterprise. [Google Scholar]

- Machado, Ricardo B. 2016. The determinants of employee ownership plan implementation in EU countries–the quest for economic democracy: A first look at the evidence. Organizacija 49: 94–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mailand, Mikkel, and Jesper Due. 2004. Social dialogue in Central and Eastern Europe: present state and future development. European Journal of Industrial Relations 10: 179–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchington, Mick, and Adrian Wilkinson. 2005. Direct participation and involvement. In Managing Human resources: Personnel Management in Transition. Maiden, Oxford and Carlton: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Marchington, Mick, and Jane Suter. 2013. Where informality really matters: Patterns of employee involvement and participation (EIP) in a non-union firm. Industrial Relations: A Journal of Economy and Society 52: 306–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marginson, Paul. 2017. European Industrial Relations: An increasingly fractured landscape? Warwick Papers in Industrial Relations 106: 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Markey, Raymond, and Herman Knudsen. 2014. Employee participation and quality of work environment: Denmark and New Zealand. International Journal of Comparative Labour Law and Industrial Relations 30: 105–26. [Google Scholar]

- Markey, Raymond, and Keith Townsend. 2013. Contemporary trends in employee involvement and participation. Journal of Industrial Relations 55: 475–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowbray, Paula K., Adrian Wilkinson, and Herman HM Tse. 2015. An integrative review of employee voice: Identifying a common conceptualization and research agenda. International Journal of Management Reviews 17: 382–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. 2018. Trade union density. Organization for economic co-operation and development. Available online: https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=TUD (accessed on 4 October 2019).

- Pateman, Carole. 1970. Participation and Democratic Theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pučetaitė, R., V Jurėnienė., and A. Novelskaitė. 2014. Lithuania: CRS on a wish list. In Corporate Social Responsibility and Trade Unions: Perspectives across Europe. Edited by Lutz Preuss, Michael Gold and Chris Rees. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Shpak, Nestor Omelyanovych, Natalia Stepanivna Stanasiuk, Oleh Volodymyrovych Hlushko, and Włodzimierz Sroka. 2018. Assessment of the social and labor components of industrial potential in the context of corporate social responsibility. Polish Journal of Management Studies 17: 209–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sippola, Markku. 2017. Ideological underpinnings of the development of social dialogue and industrial relations in the Baltic States. Available online: http://www.lpsk.lt/lpsk-web/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/Baltic-IR-development-Sippola-2017-02-23.pdf (accessed on 4 October 2019).

- Šimanskienė, Ligita, and Erika Župerkienė. 2013. Darnus vadovavimas. Klaipėda: Klaipėdos universiteto leidykla. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, Adrian, and Tony Dundon. 2010. Direct Employee Participation. In The Oxford Handbook of Participation in Organizations. Edited by Adrian Wilkinson, Paul J. Gollan, Mick Marchington and David Lewin. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, Adrian, Tony Dundon, and Mick Marchington. 2013. Employee Involvement and Voice. In Managing Human Resources-Human Resource Management in Transition. Edited by Stephen Bach and Martin Edwards. West Sussex: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | In a broader sense, the industrial democracy is an area of agreements, which encompasses the involvement of employees into the adoption of decisions when sharing responsibilities and authorities at the workplaces (Webb, Sidney, and Beatrice Webb. Industrial democracy. Vol. 1. Longmans, green, and Company, 1897). |

| 2 | Some metaphors have essential shortfalls. For example, the notion of “the voice of the employee” envisages that the employees may only “express” their position. Whereas, the term of “participation” holds more power, because it can also encompass the effect on the adoption of decisions. |

| 3 | Here, influential work councils are understood as those, who are acting in accordance to the lawful and legal basis and can influence the decisions adopted by the representatives of the employers. For example, they can elect or assign their own representatives into the boards. |

| 4 | These trade unions participated in the research: Lithuanian Trade Union “Solidarumas”, Lithuanian Confederation of Trade Unions, Lithuanian Trade Union of Carriers, Lithuanian Trade Union Alliance, Lithuanian Trade Union of Food Producers, Lithuanian Trade Union of Service Field Workers, Lithuanian Industry Trade Union’s Confederation, Lithuanian Energetics Sector Workers Trade Union’s Federation and Lithuanian Work Federation. |

| 5 | During the interview, it was failed to record a pure critical or Unitarian position of trade union representatives. Only one informant representing the work council expressed an unitarian point of view. In his opinion: “The Employers and employee representatives can always find an agreement. I can say this about my job. If need be, we go to our manager to talk without looking for very sharp angles but expressing our opinions” (interview with DT1). |

| 6 | From the contextual information submitted during the interview, it could have been understood that the respondent was talking about small-medium sized wholesale company, in which more than 50 employees work. |

| 7 | Other informants mentioned these often-encountered practices. In truth, they supplemented this by saying that such manipulation with consulting is especially often case in companies acting in smaller towns and in medium sized companies. A couple of reasons explained such practical phenomenon—conservative attitude of managers, the intention of direct or middle management to not disclose the issues of employees to the company’s management and the well-established closed non-inclusion culture. |

| No. | Participant | Code |

|---|---|---|

| Individual interviews | ||

| 1 | Chairperson of national trade union | NAC1 |

| 2 | Chairperson of national trade union | NAC2 |

| 3 | Chairperson of national trade union | NAC3 |

| 4 | Deputy of the chairperson of national trade union | NAC4 |

| 5 | Deputy of the chairperson of national trade union | NAC5 |

| 6 | General secretary of national trade union | NAC6 |

| 7 | Management member of national trade union | NAC7 |

| 8 | Head of branch trade union (transport sector) | ŠAK1 |

| 9 | Head of branch trade union (food industry) | ŠAK2 |

| 10 | Head of branch trade union (service sector) | ŠAK3 |

| 11 | Head of the company’s trade union (food industry, the company belongs to an international corporation) | ĮM1 |

| 12 | Head of the company’s trade union (transport sector’s company) | ĮM2 |

| 13 | Member of work council (food industry, the company belongs to an international corporation) | DT1 |

| 14 | Member of work council (food industry sector’s company) | DT2 |

| 15 | Expert, the manager of the project of social responsibility of the companies | EK1 |

| 16 | Expert, the head of Lithuanian Responsible Business Association | EK2 |

| Participants of focus group | ||

| 11 | Head of national trade union | |

| 12 | Management member of branch trade union | |

| 13 | Member of branch trade union (jurist) | |

| 14 | Head of company’s trade union | |

| 15 | Member of company’s trade union | |

| 16 | NGO expert, trade unions’ training, activity development area | |

| 17 | NGO expert, trade unions’ training, trainings, activity development area | |

| 18 | NGO expert, sustainable development specialist | |

| 19 | NGO expert | |

| Status of Respondents | Number of Respondents | Percentage of Respondents |

|---|---|---|

| Trade union acting at a company‘s level | 16 | 38.1 |

| National trade union | 3 | 7.1 |

| Work council | 4 | 9.5 |

| Branch trade union | 6 | 14.3 |

| NGO acting in the area of industrial relations | 1 | 2.4 |

| Expert in the area of industrial relations | 12 | 28.6 |

| N= | 42 | 100 |

| Know about | Don’t know about | Neither know about, nor don’t know about | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Financial participation of employees | 42.6 | 12.1 | 45.2 |

| Cooperation between the employees and managers (collective reporting to employees, consulting), democratic and cooperative management style | 90.4 | 0 | 9.5 |

| Teamwork, quality circles and other forms | 76.1 | 4.8 | 19.0 |

| Creation of cooperation climate, organizational culture | 90.5 | 2.4 | 17.1 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Civinskas, R.; Dvorak, J. In Search of Employee Perspective: Understanding How Lithuanian Companies Use Employees Representatives in the Adoption of Company’s Decisions. Adm. Sci. 2019, 9, 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci9040078

Civinskas R, Dvorak J. In Search of Employee Perspective: Understanding How Lithuanian Companies Use Employees Representatives in the Adoption of Company’s Decisions. Administrative Sciences. 2019; 9(4):78. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci9040078

Chicago/Turabian StyleCivinskas, Remigijus, and Jaroslav Dvorak. 2019. "In Search of Employee Perspective: Understanding How Lithuanian Companies Use Employees Representatives in the Adoption of Company’s Decisions" Administrative Sciences 9, no. 4: 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci9040078

APA StyleCivinskas, R., & Dvorak, J. (2019). In Search of Employee Perspective: Understanding How Lithuanian Companies Use Employees Representatives in the Adoption of Company’s Decisions. Administrative Sciences, 9(4), 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci9040078