1. Introduction

Local government decision-making is a long lasting and iterative process involving much more than the actual moment of taking the decision. The task of a political leader in a local government organization is multi-faceted and demanding. Politics entails at a minimum problem solving, inspiring others, managing conflicting interests and values, cooperating, making decisions and following up the implementation of the decisions. A central feature in the duties of an elected political leader is interacting with public administrators, other political leaders and municipal residents.

However, in practice people have different ways of communicating with each other and they may consider some tasks more difficult than others. They also have different working habits and prefer some ways of working over others. These habits meet in the decision-making process. Additionally, the elected political leaders come from different backgrounds and represent different interests; their common task is to work for the best interests of the municipality and its residents (

Local Government Act 519/2007, §32;

Local Government Act 410/2015, §69).

In today’s organizations political leaders in local government face multiple challenges such as globalization, Europeanization, urbanization, continuous reforms and requests for services, effective service production and direct participation are a part of the decision-making environment. Another challenge on a more personal level is the exacting requirements for decision-making quality and the time used for duties of an elected official (

Piipponen 2015;

Sandberg 2016). Capacities for self and co-governance and for more communicative and interactive ways of acting are required from the political leaders to cope with the fast-paced operational environment (

Bang 2004). The political leaders’ work also challenges the rest of their lives, from family and friends to their careers (

Copus 2016, p. vii).

Political decision-making and the process related to it is one of the most crucial features of local government organizations. Local democracy gives the residents an opportunity to participate in local decision-making and elections are the way to ascertain what the electorate wants as well as to ensure political accountability (

Egner et al. 2013b, p. 257;

Overeem 2012, pp. 74–77). In their positions local councilors, political leaders, face a lot of misunderstanding and criticism. This may come from the media, the public or the government. For example, reducing the number of councilors is often discussed, but the likely consequences of that for democracy and self-government are discussed more seldom (

Copus 2016, p. vii).

The Finnish Local Government Act (

Local Government Act 519/2007, §32; amended in

410/2015, §69) is unequivocal on the task of all elected officials in a municipality; it is to make decisions in a manner conducive to promoting the interests of the municipality and its residents and to act with dignity in their positions of trust in a manner befitting the task. Thus, the political leaders determine the will of the municipality and are responsible for this to the municipal residents (

Egner et al. 2013a, p. 14;

Majoinen and Kurikka 2013, p. 142).

The public sector is complex in nature. Firstly, the roles of political leaders, public administrators, and residents create a specific operating environment (

Niiranen and Joensuu 2014;

Joyce 2015, p. 4). Secondly, contemporary features of the context, administrative history, culture and traditions influence strategic management in the public sector (

Meneguzzo 2007). Thirdly, public value, the logic of managing public money and prioritizing in a democratic process is characteristic of the public sector (see e.g.,

Hartley et al. 2018). Thus, the effectiveness of strategic planning and management in the public sector depends on the emphasis on context, stakeholders, politics, alternative future scenarios, decision making and implementation (

Bryson 2018;

Joyce 2015).

In Finland, as in most Western societies, the dualistic model is as such an important context factor in local government strategic management and decision-making (

Ring and Perry 1985) and the classical ideal type model of bureaucracy was used in designing the management system of public organizations (

Overeem 2012, pp. 74–77). However, structural change influences the operations, models and interaction in local government (

Bækgaard 2011) and Finland is known for long lasting reform processes (

Kettunen 2015).

At the end of the 2010s Finland is still undergoing a major public sector structural reform launched in 2006 (

Government Proposal 155/2006) to increase the size of the municipalities and thereby to create stronger municipalities. In general, there are three major categories of anticipated consequences of municipal mergers: Economic efficiency; managerial impacts and democratic outcomes. The results observed vary, but mostly the mergers have impaired the quality of local democracy (

Tavares 2018). The discussion on municipal mergers and larger entities was intense ten years ago, at the end of the 2000s, and some similarities to today’s situation are discernible (see e.g.,

Saarimaa and Tukiainen 2018).

3. Research Data

The quantitative research data were gathered by a questionnaire from political leaders (

N = 166) in six

1 Finnish local government organizations in 2011 and 2012. Qualitative interview data (

N = 27) was used as material for the quantitative research together with earlier research results on local government. We conducted 18 interviews with the chairpersons of municipal councils, executive boards, the committees responsible for social and health-care services and with members of the boards of directors responsible for producing social and health care services, and nine interviews with strategic-level leaders or middle management in the central administration of social and health-care services. The interviews were transcribed and examined using theory-dependent content analysis (

Molina-Azorin 2012) and the findings were classified into themes using an analytical framework. Thereafter a questionnaire was developed based on the themes extracted from the interview data. The questionnaire was pre-tested for content validity among a group of political leaders not belonging to the actual group of respondents. After pre-testing, minor modifications were made to improve the clarity of the questionnaire. The respondents to the questionnaires were political leaders in the case organizations (

Niiranen et al. 2013).

The six organizations from which the data were gathered represent a cross-section of Finnish municipalities. They are of different sizes, located around the country, and they have organized their social and health-care services in different ways. Due to its extensive responsibilities, Finnish local government provides a platform for studying the interaction between political leaders and public administrators in reforming organizations. Four of the municipalities are fairly large by Finnish standards, one is middle-sized, and one is a co-operation district (see e.g.,

Kettunen 2015, p. 56) formed by combining three small municipalities. Most inhabitants in the four largest local government organizations live in densely populated areas, but the smaller local government organizations are in rural areas. In Finland, large and small municipalities are tasked with the same responsibilities (

Local Government Act 519/20072;

Kettunen 2015). All participating organizations have carried out some type of major reforms during the five years before data collection in order to facilitate the organization of the municipal services. Both municipal mergers and other kinds of organizational reforms were implemented, which aptly reflects the situation in the Finnish municipalities at the time of data collection.

The questionnaire for political leaders was sent to the municipal councils, executive boards and committees responsible for social and healthcare in the six case organizations (

N = 459). The response rate after four reminders was 36.2% (

N = 166) and all questionnaires returned were usable. Unit non-response was analyzed regarding the organization, political affiliation and gender of the respondent. The response rate between organizations varied from 32 percent to 38 percent. The respondents’ political affiliations compared to the political affiliations in the target group were nearly equal, and the respondents accurately represent the political map of the organizations. The gender balance of the respondents reflects the gender balance of the political leaders to whom the questionnaire was sent. Item non-response was analyzed question by question, and the largest non-response was encountered in the open-ended questions. In the questions analyzed for this article, item non-response was at largest 1.8%. We considered that the respondents represent the target group sufficiently well, but a higher response rate would have been desirable (

Baruch and Holtom 2008;

Niiranen et al. 2013, pp. 50–52).

4. Analysis

In an earlier article (

Joensuu and Niiranen 2018), two sets of questions from the questionnaire to political leaders were used to form three groups of political leaders according to how much the issues mentioned influenced the decision-making processes in their respective municipalities. These groups are used in the analysis in this article.

We conducted an exploratory factor analysis with principal axis factoring and oblique rotation on the political leaders’ opinions on the municipal decision-making process to find the underlying structure in the dataset (

Hair et al. 2014, p. 97;

Field 2013, pp. 665–719). We accepted a solution with five factors even if one of the factors had an eigenvalue just under 1 as we considered that, after reviewing the eigenvalues, the number of non-trivial factors and experimenting with the proposed solutions, this was the simplest factor solution. The extraction sums of squared loadings accounted for 59.3 percent of the explained variance, which can be considered satisfactory as the factors correlate with each other (

Hair et al. 2014, pp. 107–8). The statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS data package.

The five factors lack of trust (three variables), municipal residents (three variables), prejudice (three variables), information process (three variables) and strategic soundness (six variables) represent the dimensions influencing the local government decision-making process. The initiative clusters were created using Ward’s method and the analysis was amplified using k-means clustering (

Hair et al. 2014, pp. 446–48). A three-cluster solution was chosen and the groups were named according to the dimensions they represented by studying the means and mean centered values of the grouping dimensions.

The first group was named trustful, as the group members were more trusting and positive in their attitudes towards the issues measured by the grouping variables. The municipal residents variable was the only exception as in that there is no difference between the three groups. Considering the nature of the respondents’ position as local government political leaders this is logical. The second group was named middle-of-the-road and included about half of the respondents. The group members were middle range on all clustering dimensions. The third group was labeled as critical. The group members had more negative attitudes towards the issues measured by the grouping variables than the middle-of-the-road group. The differences between the groups are statistically significant (

p < 0.001) on all the grouping variables other than municipal residents. (

Joensuu and Niiranen 2018). In this article three more sets of questions and some background data from the questionnaire to political leaders were analyzed using these groupings as the basis for the analysis. We used simple contingency tables to explore the similarities and differences between the three groups.

5. Results

5.1. Demographics of the Trustful, the Middle-of-the-Road and the Critical

To better understand the demographics of the three groups of political leaders, we explored a few background factors concerning the political leaders in the groups. We also explored the political leaders’ roles in the decision-making process.

In two of the case organizations the critical group was larger than the trustful group and in four organizations the trustful group was larger. In all six organizations the middle-of-the-road group included approximately half of the respondents.

The gender balance of the critical group was slightly different from that of the other two groups. In the critical group 53% were women whereas in the two other groups the respective shares were 44% and 42% (

Table 1). The number of those over 65 years old was slightly larger in the middle-of-the-road group (27%) than in either trustful (20%) or critical (19%) groups.

The members of the trustful group lived slightly more often (43%) in the inner city or municipal center than the members of the two other groups (34% and 28%). The members of the critical group (41%) lived slightly more often in the countryside than the members of the two other groups.

The political leaders in the critical group had slightly more often only secondary education (69%) compared to the other two groups in which the share of political leaders who held at least a bachelor’s degree from university or university of applied sciences was greater. The professional backgrounds also slightly varied between the groups. The trustful were most often either officials, workers, retired or in a managerial position whereas the critical were most often either retired, entrepreneurs, specialists, workers or outside the workforce. The middle-of-the-road group were most often retired, upper- or lower-level employees, workers or specialists. The critical group members (39%) worked more often in the same municipal organization in which they were elected political leaders than the members of trustful group (25%) and middle-of-the-road group (26%).

At the time of data collection, the trustful group members were more often members of a municipal board (46%) than were the members of two other groups (

Table 2). More members of the critical group (90%) were members of the municipal council (in Finland committee members do not necessarily need to be council members) than were members of the two other groups. The middle-of-the-road group (26%) was least represented in municipally owned companies or municipal enterprises. The critical group (36%) was slightly more often represented in joint municipal authorities than the other groups, but the difference was minuscule. In other positions (for example school boards or other organs) there was no difference between the groups.

The political leaders were also asked if they had been in various elected positions (municipal board, council, committee, municipal enterprise/municipally owned company, joint municipal authority or other) and, if so, for how long. The trustful group had typically held 3–5 different elected positions, the middle-of-the-road group 2–4 and the critical group 3–4 positions. Almost 60% of the trustful group had been on a municipal council for over 11 years. For the critical group and the middle-of-the-road group, the share was 47%. The trustful group had the largest share (17%) of those who had never been on a municipal council. In the critical group this was 7% and in the middle-of-the-road group 8%. Considering the municipal boards, the trustful group had the largest share (15%) of those who had served for more than 11 years and the critical group had the largest share of those who had never been in the municipal board (53%). Similarly, in municipal committees the trustful group had the largest share (48%) of those who had served for more than 11 years. For the middle-of-the-road group the share was 26% and for the critical group 23%. The middle-of-the-road group (16%) and the critical group (17%) had the largest share of those who had not been on committees. For the trustful group the share was 7%. Interestingly, 52% of the middle-of-the-road group had not been in elected positions in joint municipal authorities. For the trustful group the share was 35% and for the critical group 47%.

5.2. Political Leaders’ Views on Trust and Appreciation in Their Work

In much of the research on political leaders and public administrators, trust has been considered important for interaction quality and cooperation. To assess these dimensions, we asked a series of questions on the quality of discussion, mutual appreciation, valuing different opinions, and providing reliable information (

Table 3), which could be considered to enhance mutual trust and cooperation. We asked the respondents to assess how often the issues mentioned were apparent in their respective political organs. In all the questions, the differences between the three groups were statistically significant and the strengths of the relationships measured with Cramer’s V

3 were moderate for all five questions.

Two thirds of all respondents considered the discussion in the council, board or committee to be frequently frank and sincere. Respondents in the trustful group were very strongly of that opinion (85%), while the respondents in the critical group had more varying opinions on the issue, the percentages of responses rarely (35%) and frequently (39%) were very similar. Considering valuing different opinions in the council, board or committee, the respondents in the trustful group again firmly agreed on (65%) that this was frequently the case. However, almost half of the respondents (47%) in the critical group were of the opposite opinion and considered that the discussion was rarely frank and sincere.

We asked two questions about political leaders’ appreciation for the work of public administrators and about public administrators’ appreciation for the work of political leaders. In both questions, the respondents in the trustful group were emphatically of the opinion that this was frequently the case (78% and 63%). Meanwhile, nearly one third of the respondents in the critical group considered that political leaders rarely appreciated the work of public administrators. A little over half (54%) of the respondents in the critical group were also of the opinion that public administrators rarely appreciated the work of political leaders.

While analyzing the interview data, we found that the public administrators thought that the political leaders mostly used the information they provided on the agenda in the decision-making process. However, the political leaders considered the information to be a process that included both the agenda and collecting other information from written sources as well as in interaction with the municipal residents (

Niiranen et al. 2013). In this set of questions, we asked the respondents about the reliability of the data provided by the public administrators. In this respect, the respondents in the trustful group were decidedly (83%) of the opinion that the information provided was frequently reliable, while the respondents in the critical group had more varying opinions on the issue and one third of them (32%) considered the information to be only seldom reliable. Even in this case, 39% of the respondents in this group considered the information to be frequently reliable.

5.3. Discussions in the Decision-Making Process

Discussions between actors, both official and unofficial, are an essential part of the local government decision-making process. We asked five questions directly related to the time used for discussions and preparation. Two questions then addressed unofficial discussions and personal communication between the political leaders and public administrators (

Table 4).

Most of the respondents in the critical group (70%) considered that there was rarely enough time for preparatory discussion before decision-making. However, 60% of the political leaders in the trustful group considered that there was frequently enough time for preparatory discussion. The distribution on the second question resembles that on the first one. In the critical group, 65% of the respondents were of the opinion that there was rarely enough time for the decision-making discussion, whereas in the trustful group 72% of the respondents reported that there was frequently enough time for the decision-making discussion. In both questions the connections between the variables were moderate.

In the following two questions, the political leaders assessed how often the public administrators had time to discuss with them and how often the political leaders themselves had time to discuss with public administrators. In the critical group, 62% of the respondents were of the opinion that the public administrators rarely had time to discuss with them. This contrasts with the results of the other two groups. In the trustful group, 59% and in the middle group 45% of the respondents were of the opinion that the public administrators frequently had time for discussion with the political leaders. In their self-assessment, half of the political leaders in the trustful and middle groups (52% and 51%) reported that they frequently had time for discussion with public administrators. However, half (50%) of the respondents in the critical group were of different opinion and considered that they rarely had time for discussion with public administrators.

Agenda issues in decision-making and issues arising from the operating environment are not simple, and thorough preparation is essential to ensure quality in the decision-making process. For this reason, we asked the political leaders how often they considered the schedule for preparing the agenda issues to be too tight. The political leaders in all groups considered often (40%) that, at least occasionally, the schedule for preparing agenda issues was too tight. The middle group and the critical group felt even more that this was frequently the case (42% and 53%), while 26% of the trustful group considered the schedule to be only rarely too tight.

Unofficial discussion outside of official functions was considered rare by 40% of the respondents in the critical group. In the trustful group 43% considered it to be evident frequently. On personal communication on agenda issues between political leaders and public administrators, almost half (48%) of all respondents reported that this was occasionally apparent.

5.4. Objectives and Commitment

Setting objectives is an integral part of local government strategic management. In the third set of questions, we asked the political leaders how often political leaders and public administrators had different opinions on objectives (

Table 5). More than half (57%) of the critical group considered this to be the case frequently whereas the share for the trustful group was 6%.

The political leaders were also asked to assess how often the elected political leaders were dedicated to their duties. Most of the trustful and middle groups considered this to be frequently the case (85% and 70%), but the critical group was strongly polarized: Only 47% of the respondents answered frequently whereas 41% answered rarely.

Political leaders and public administrators have different bases for their tasks and thus, different kinds of professional expertise. We wanted to know how often it was evident that public administrators and political leaders compete on expertise. Most of the trustful group (74%) and almost half of the middle group (46%) considered this to be frequently the case, but the critical group was again polarized: 47% of the respondents answered frequently, whereas 37% answered rarely.

Finally, we asked the political leaders to assess how often the party-political objectives of the public administrators were evident in the work of their local government organs. Here, too, the polarization between the trustful and the critical groups was obvious. When 65% of the trustful group reported that the party-political objectives of public administrators were rarely apparent, 55% of the critical group was of the opinion that they were frequently obvious. The responses to all four questions were statistically significant with moderate connections between the variables.

5.5. Most Difficult Issues as a Political Leader Explored by Group

In the questionnaire we also asked the political leaders to choose a maximum of three issues they had encountered as political leaders and considered to be the most difficult. The results for all the respondents showed that for the political leaders the most difficult issues seemed to be strategic in nature (economic resources, disparity between decision-making concentrating on the fiscal period and long-term effects of decisions and scheduling) whereas for the public administrators the most difficult things seem to be related to the political leaders’ personal characteristics (

Niiranen et al. 2013). However, the variation within the group of political leaders raises questions.

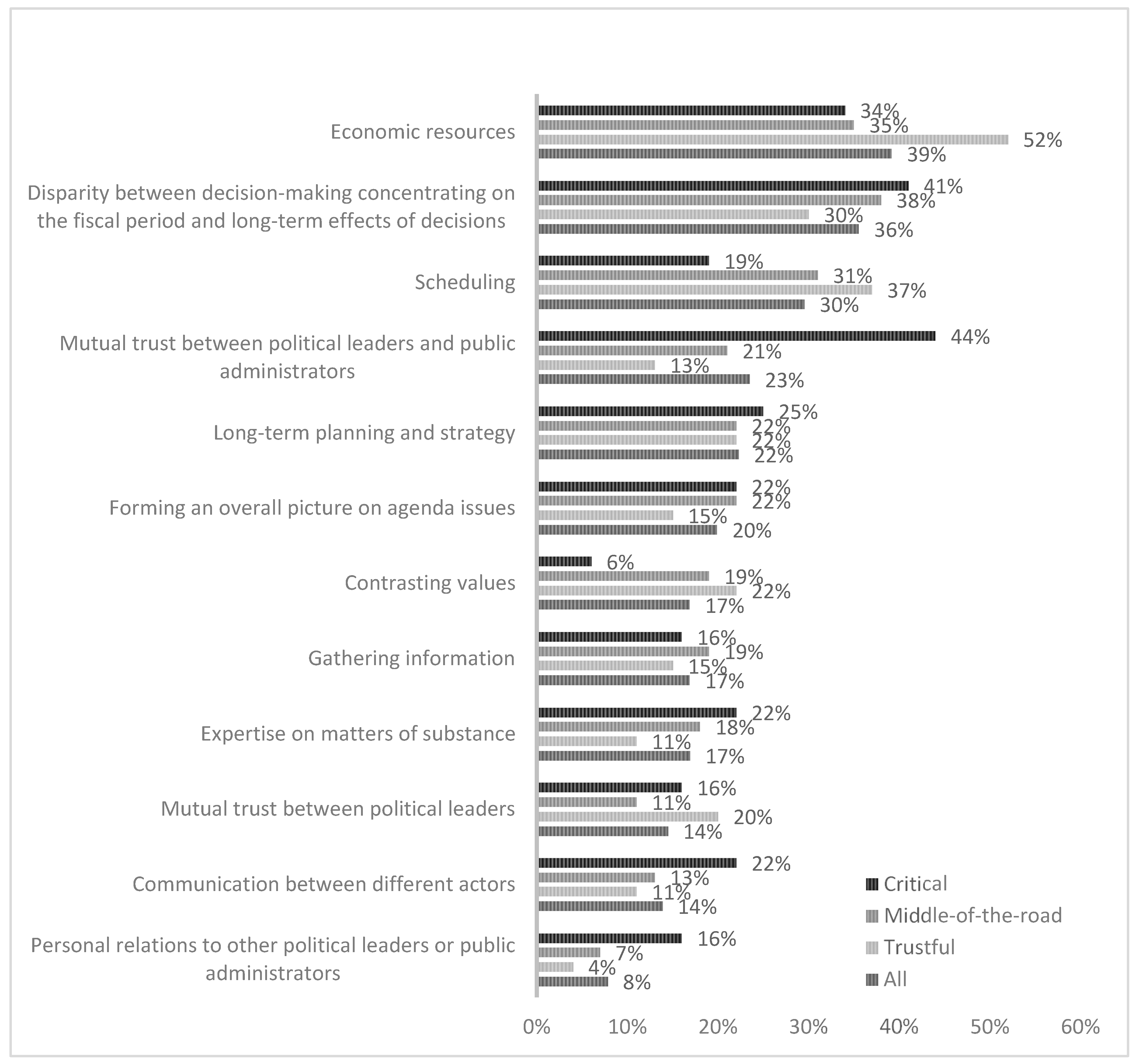

The three groups, trustful, middle-of-the-road and critical, differ somewhat with regard to what they consider most difficult (

Figure 1). For the critical group the three most difficult things were (1) mutual trust between political leaders and public administrators (44%), (2) disparity between decision-making concentrating on the fiscal period and long-term effects of decisions (41%) and (3) economic resources (34%). Interestingly, the other two groups considered the issue of mutual trust a lot less difficult: 13% (trustful) and 22% (middle) of the responses. The critical group did not consider disparate values to be difficult to encounter; only 6% of the respondents mentioned it as one of the most difficult issues. For the trustful group it was in the fifth place (22%) on the list.

For the middle-of-the-road group the most difficult issues were (1) disparity between decision-making concentrating on the fiscal period and long-term effects of decisions (38%), (2) economic resources (35%) and (3) scheduling (31%). The trustful group mentioned the same issues, but in a different order. For them the most difficult issues were (1) economic resources (52%), (2) scheduling (37%) and (3) disparity between decision-making concentrating on the fiscal period and long-term effects of decisions (30%). Of these three issues, a much smaller part of the critical group considered scheduling to be one of the most difficult things (19%) than in the other two groups.

5.6. Time Allocated for Municipal Elected Positions and Interaction, and Interaction Frequency

To ascertain if the different groups acted differently, we examined how much time they allocated to different tasks. Additionally, we looked for differences in how often the political leaders interacted with other actors.

Most commonly the political leaders used less than three working days for their elected positions (

Table 6). In both the trustful (20%) and critical (19%) groups the share of those who used more than six working days was greater than in the middle-of-the-road group.

The political leaders in the three groups allocated their time slightly differently. Additionally, we asked the political leaders to roughly estimate how much time they used weekly for different tasks (under 1 h, 1–4 h and more than 5 h). In all groups most of the political leaders (70%) used 1–4 h to read the paperwork, agendas and other material. The share of those who used more than 5 h for searching background material and clarifications was largest in the critical group (16%). In the critical and middle-of-the-road groups there were slightly more of those who did not use any time for meetings with public administrators (28%) than in the trustful group 20%. The share of those who used 1–4 h in a week was in all groups approximately 30%.

Most commonly in all groups 1–4 h/week was used for discussions within one’s own political party group. Both the trustful and critical groups used slightly more time for discussions and meetings with the municipal administrators and employees other than the presenting

4 public administrator than did the middle-of-the-road group. Half of all respondents used less than one hour a week for discussions and meetings with municipal residents. The members of the critical group used slightly more time for this than did the two other groups. Additionally, the share of those, who used more than 5 h for discussions with municipal residents was much lower in the middle-of-the-road group (6%) than in the two other groups (13% trustful and 16% critical).

Almost all members of the trustful group had weekly contact with the presenting public administrators (98%). In the two other groups the share was 90%. The members of the trustful group had weekly contact with the neighboring municipalities more often (46%) than the two other groups (approximately 30%). The trustful (87%) and the middle-of-the-road group (85%) had more often weekly contact with municipal residents than the critical group (69%).

Both critical and trustful groups had more frequent interaction with the regional organs and joint municipal authorities than did the middle group. However, the share of those being in contact with joint municipal authorities only once in a quarter year or less was greatest in the critical group (21% and in the other groups 13%).

The critical group (48%) had weekly contact with private business more often than the trustful (33%) and middle-of-the-road groups (35%). They also had weekly contact with members of Parliament more often (66%) than did the trustful (56%) and the middle-of-the-road groups (48%). Similarly, they had weekly contact with the media (70%) more often than did the trustful (57%) and the middle-of-the-road groups (48%).

6. Discussion

6.1. Similarities and Differences Between the Three Groups

The three groups were in many aspects similar to each other, but there were also differences in the way they consider the phenomena and how they actually act as political leaders.

Table 7 illustrates the main differences between the three groups.

The data suggest that the critical and trustful groups were slightly more active than the middle-of-the-road group, but they targeted different issues and allocated their time somewhat differently. The size of the groups also varied between organizations. This may indicate, that the critical and trustful groups are a source of the tension that creates opportunities for discussion both on the committees, boards and councils, and between political leaders and public administrators. Additionally, the contextual, structural elements may have an effect on the way the political leaders act in their duties. Unfortunately, the data did not afford a better understanding of whether the differences in group sizes depended on who were voted in the positions as elected political leaders or if the differences were in other ways dependent on the situation prevailing in the municipal organization (for example tight economic situation or major reforms).

It is theoretically interesting, if the different balance of the groups of actors leads to different cultures in the strategic decision-making processes and if the processes ultimately lead to differently shaped structures. The political leaders in the three different groups reflecting their personal styles and attitudes perceived parts of the local government work in very different ways.

6.2. Experiences of the Functioning of the Governing Bodies

The administrative culture is part of formulating the strategy and implementing it, which makes it an important factor in public strategic management (

Smith and Vecchio 1993). There were clear differences between the groups with regard to experiences of the functioning of their respective governing bodies. When we explored the political leaders’ views on trust, appreciation, discussions, objectives and commitment, the critical group more rarely felt able to trust the information and other actors than did the other groups. At the same time, they felt less often appreciated and valued. They also wanted more time for discussions. These results lead us to think that it is possible that the critical people feel that they cannot utilize their full potential in their tasks. They are willing to stand up for their values, but at the same time they may feel that they are left somewhat outside the core of the interaction. The critical group was not only critical of the public administrators, but also of their fellow political leaders and, for example, their commitment. They also thought that political leaders and public administrators often have different opinions on objectives. It is easy to assume that the political leaders belonging to the critical group would experience their duties as important but demanding.

The trustful group was the one most satisfied with the time allocated for the discussions, the contacts with public administrators and the frequency of such contacts. They also very seldom felt that the discussion in the decision-making body was less than frank and sincere. Thus, their experience of local government work was very different from that of the critical group. The middle-of-the-road group was the largest group and possibly had a balancing role.

6.3. Differences in What Is Considered Difficult

The task of the political leaders is to make decisions. The decisions are based on judging the value of actions and then prioritizing resources in budget based on the values. The implementation of reforms in particular requires a lot of interaction between strategic decision-makers, central government and local government to implement strategies and to make the functions more effective (

Joyce 2015, p. 286). The process requires a good deal of cooperation and value conflicts cannot always be avoided.

We asked the political leaders about the most difficult aspects of their work things in their duty as political leaders. The differences between the three groups were thought provoking. The results for all the respondents showed that for the political leaders the most difficult things seemed to be strategic in nature (economic resources, disparity between decision-making concentrating on the fiscal period and long-term effects of decisions and scheduling). However, the critical group was very different from the other two groups in three ways: For them the most difficult issue was a more personal issue, trust between political leaders and public administrators. The critical group did not consider contrasting values difficult in any way, and communication between different actors was mentioned more often than by the other two groups. Possibly these political leaders were used to value differences and ready to defend their own values. For some reason they simultaneously considered both mutual trust, personal relations with other political leaders or public administrators and communication to be more difficult issues than they did the other groups.

The trustful group considered economic resources and scheduling to be clearly more problematic for them than did the respondents in the other two groups. Unfortunately, the results do not reveal more explanations for this than the personal style of interaction. These differences may indicate fundamental differences in the way the political leaders in these groups conceived of the organization and other actors involved in the decision-making processes.

6.4. Limitations of the Study

This study was explorative in nature and had some limitations. The research data was rather small and it was gathered in the period 2011–2012. However, the response rate for the questionnaire was moderate and the results were well aligned with the qualitative data we collected from the same organizations.

All the local government organizations in this study had either implemented or been implementing reform projects at the time of data collection or shortly before it. These reform processes are often structural in nature, but they also affect the interaction between actors in the organizations. For this reason, the data from 2011–2012 is still interesting.

Certainly, some things have changed during the past eight years, but much remains the same. The municipalities participating in the research project were active in developing their council, board, and committee work. Some of the working habits, like seminars, workshops and professional guests, have currently become more common. The discussion on mergers remains valid, but it has partly shifted towards a discussion on some form of regional government. However, the original plans ceased to be implemented in March 2019.

The questionnaire was based on earlier research on the topic and on qualitative data collection to ensure its quality. The municipalities participating in the study represent the full range of Finnish municipalities, which was considered important when designing the study. The time of data collection was towards the end of an electoral period. This was mainly a positive thing, as the political leaders in their first term in office had had some time to develop their relations with both the other political leaders and public administrators.

To test and develop the validity of the grouping methodology, new, larger data from local government organizations should be collected. It would also be very interesting to see the possible changes in the results. A larger dataset would also make it possible to explore more closely, for example, the length of terms of the respondents or other additional variables.

7. Conclusions

The foundation of the Nordic local government is that each municipality is a community of residents, arranges services for residents in a way that is financially, socially and environmentally sustainable, and promotes the well-being of residents and the vitality of their respective areas. Municipalities are a core element of the democratic system and form the basis of local government.

Moreover, polyphony is an essential part of the Nordic democracy. This is articulated through representatives in the elected bodies at both national and local level. The case of strategic management in Finnish local government is interesting because the interplay between agency, structure and culture (

Archer 1995,

1996) is present in many ways. The elected bodies and public administrators act in close cooperation in local government. The logics of politics and administration are partly different and an outcome of historical tradition. Similarly, the organizational features have multiple layers as a legacy of past and present reforms. The differences between the groups of political leaders examined in this article can be placed in the cultural realm, which includes ideas and beliefs (

Archer 1995,

1996). Over and above political ideas, the views on interaction are another essential part of the culture.

All three groups seemed to play an important role in the local government decision-making processes. The critical and trustful groups were more active, but their activity was channeled in slightly different directions. The critical seemed to be more willing to connect with the world outside the municipal domain (i.e., media, members of parliament and business) and the trustful had more often positions, for example, on a municipal board. Similarly, this indicated that political leaders understood the importance of networking in the course of their duties, but the networks were partly different. However, if we revert to the task of political leaders, the different networks meeting in the strategic decision-making processes may lead to optimal outcomes and the most comprehensive understanding of the issue. The prerequisite for this is that the interaction between the three different groups functions well.

The middle-of-the-road group was the largest and is possibly a balancing factor between the two other groups. Some of the differences in modes of interaction may also be due to the different professional backgrounds represented in the groups. Interestingly, the age structure of both the critical and the trustful groups was very similar. Divisions between political parties are not the only ones present in modern local government decision-making processes and strategic management processes.

The practical implications of these results for public administrators working with political leaders may be that it is important to consider how newly elected political leaders integrate into their respective political groups and the group of political leaders. There is a need to understand that the political leaders should not be treated as one group or only be grouped according to their political affiliations. There are more fundamental differences between the groups of political leaders in their thoughts, for example, about interaction, trust and strategic issues. The role and position in local politics is dependent on both personal attitudes, working habits and interests and the formal structure. These results suggest that a better understanding of different types of interaction can help to reinforce the abilities of individual political leaders and thus lead to a stronger local political culture and a stronger local democracy. However, it could still be possible to develop and strengthen the participative approaches in local government decision-making (see e.g.,

Joyce 2015). Local structures are a product of local action and context factors. Similarly, local action is a product of local structures and contextual factors. Maintenance of polyphony in the strategic decision-making and interaction processes is essential to democracy.