Land Governance Re-Arrangements: The One-Country One-System (OCOS) Versus One-Country Two-System (OCTS) Approach

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- What are the similarities and differences in the two cases and why is this so?

- What are the implications of these differences for land governance re-arrangements?

2. Institutional and Instrumental Approaches to Land Governance

2.1. Structuration Theory

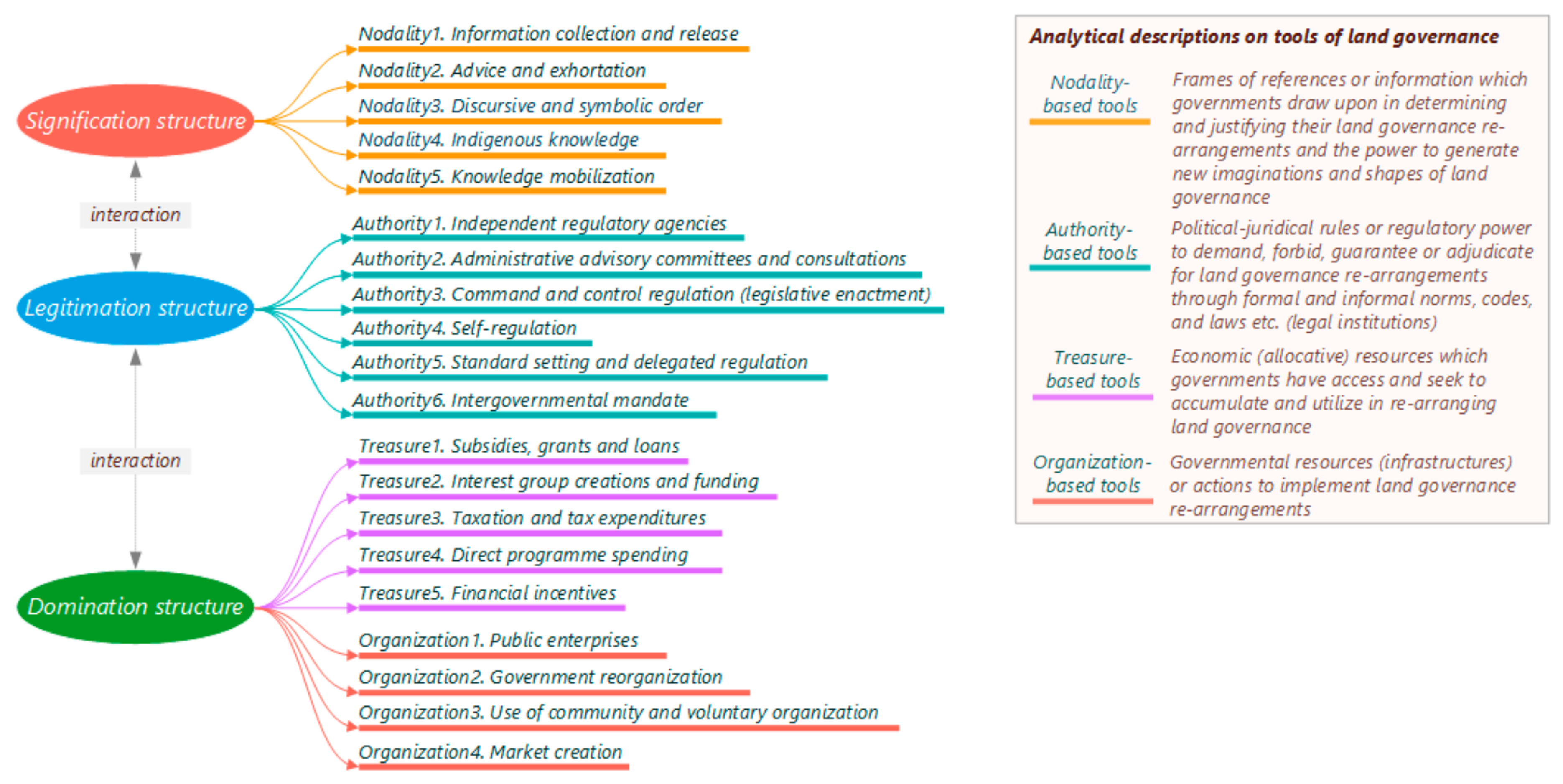

2.2. Tools of Government

2.3. Land Governance

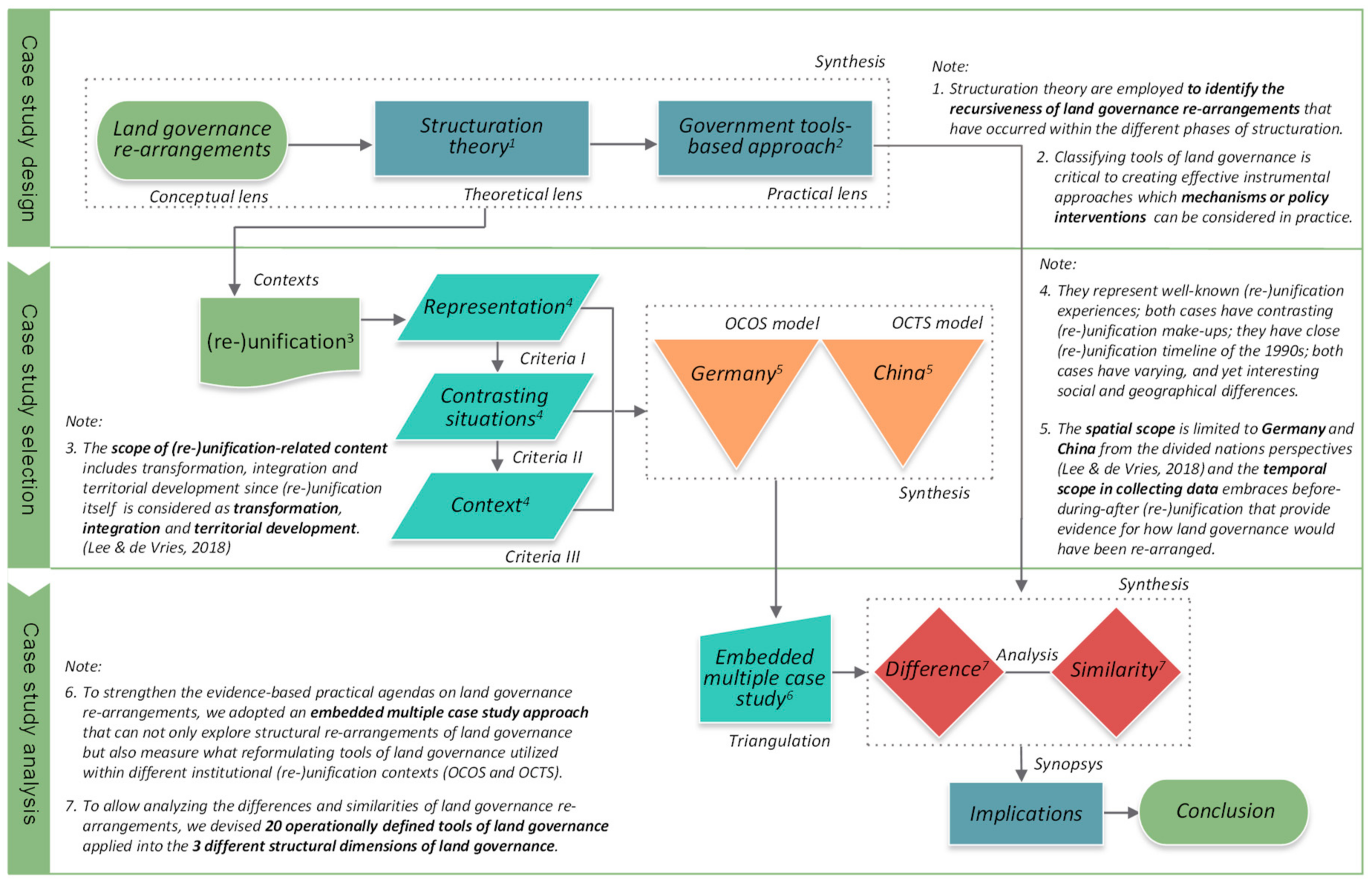

3. Methodology

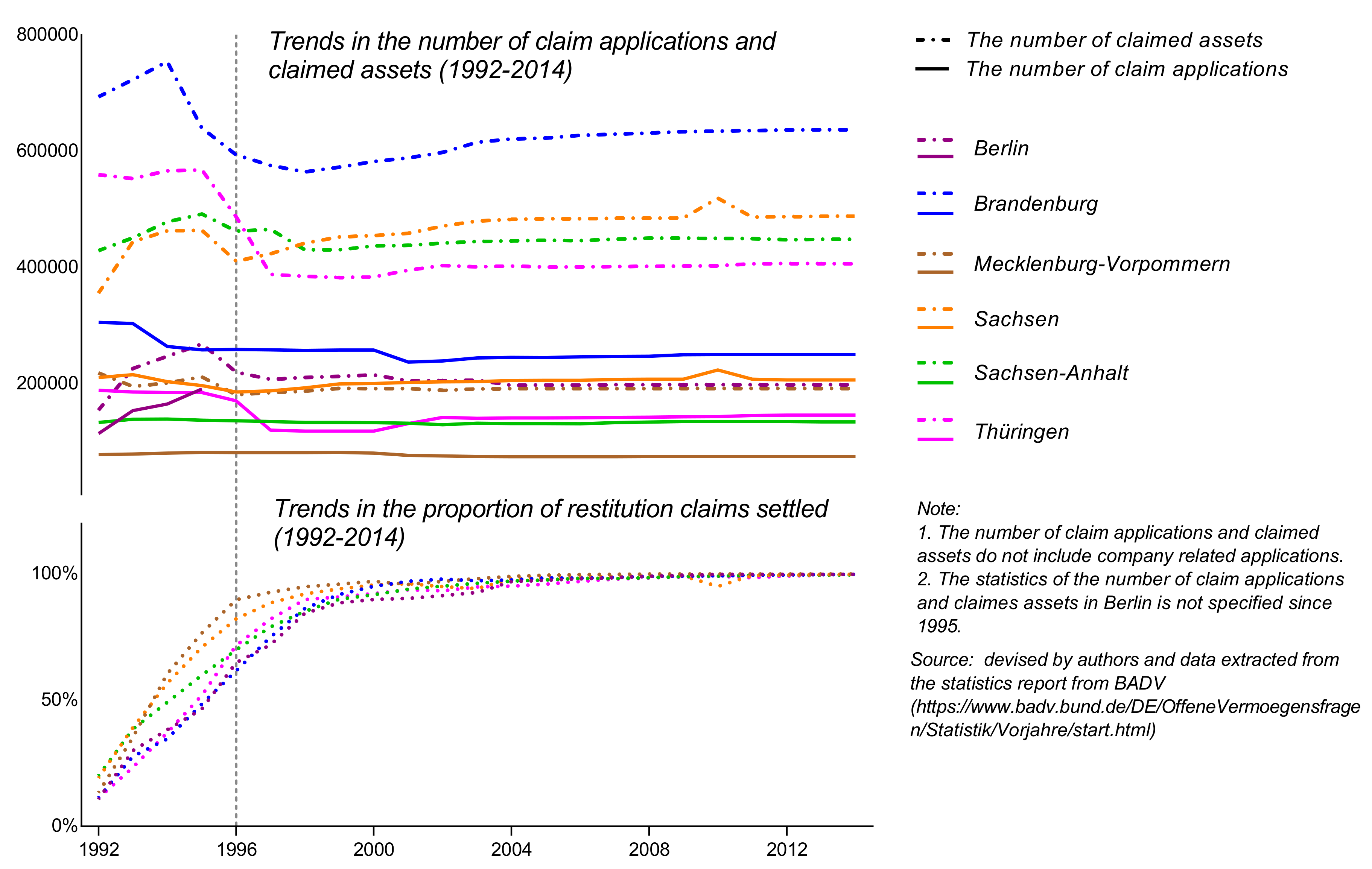

4. Case Study 1: Land Governance Re-arrangements in Germany as OCOS

4.1. Signification Structure

4.2. Legitimation Structure

4.3. Domination Structure

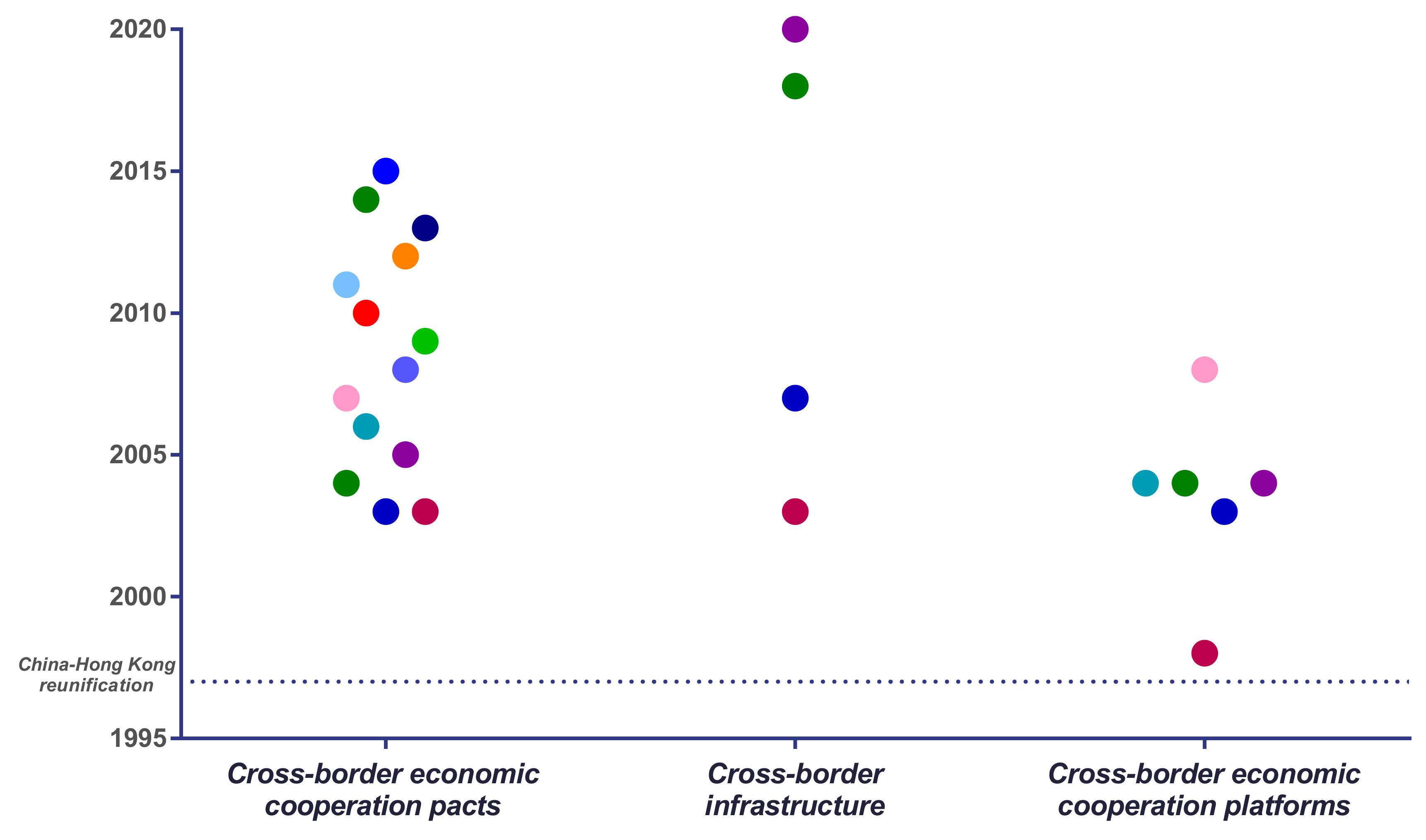

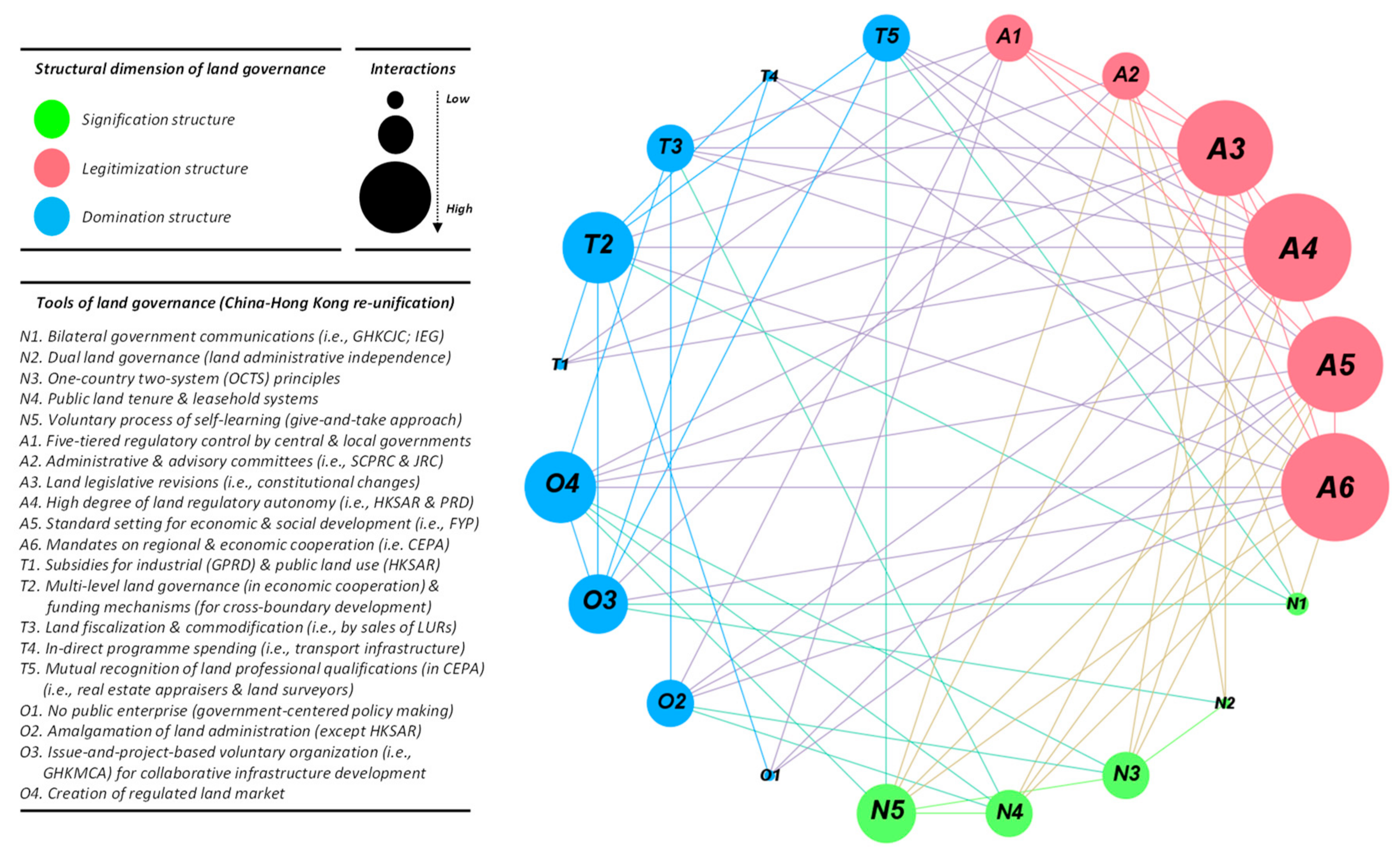

5. Case Study 2: Land Governance Re-arrangements in China-Hong Kong as OCTS

5.1. Signification Structure

5.2. Legitimation Structure

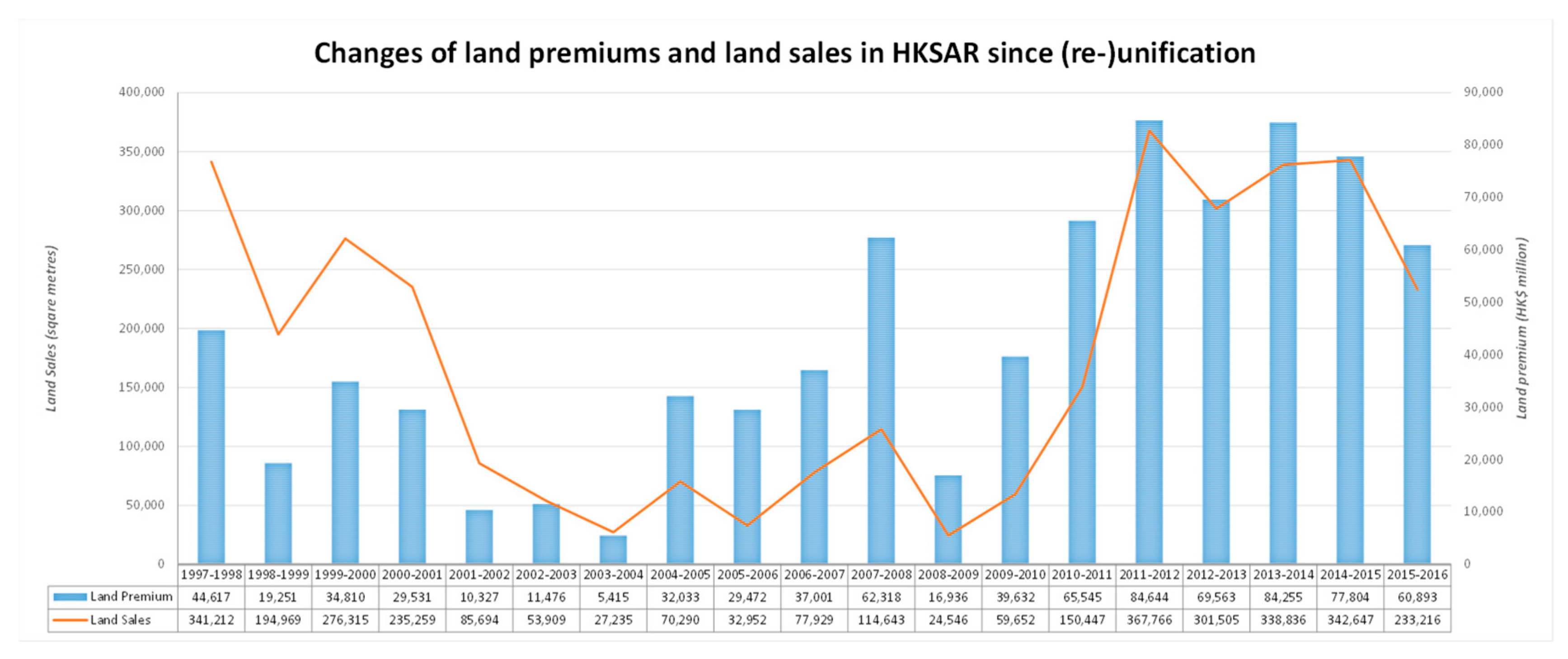

“The land and natural resources within the HKSAR shall be state property. The Government of the HKSAR shall be responsible for their management, use and development and for their lease or grant to individuals, legal persons or organizations for use or development.”

5.3. Domination Structure

6. Synopsis of Results

6.1. What Informs the Interpretation of Land Governance in the (Re-)Unification Context?

6.2. What Defines the Legitimacy of Land Governance and Which Rules Are Chosen to Rearrange Land Governance?

6.3. What Structures and Capacities Do Government Possess in Transforming Land Governance?

7. Conclusions

- When adopting adaptive land governance, governments should monitor and identify formidable obstacles in (re-)unification processes and then proactively or reactively manage them using authority-based tools in legitimation structures.

- When relying on hierarchical enforcement, legitimation structures require strong political leadership at different administrative levels, which gradually transform land governance as a long-term project.

- When adopting multi-level land governance, the government should endeavour to establish transparent land markets and land tenure security at the domination structure phase, include rural development as a priority of land governance transformation, and build multi-layer check-and-balance mechanisms through which various stakeholders can contribute.

- Adopting issue-and-project-based land governance only works when fundamentally different institutional contexts and frameworks exist prior to (re-)unification. It is important to cope with cross-boundary infrastructure and economic development before changing land governance.

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Archer, Margaret Scotford. 1995. Realist Social Theory: The Morphogenetic Approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Augustinus, C. 2009. Improving access to land and shelter: Land governance in support of the MGD: Responding to new challenges. Paper presented at the Word Bank and International Federation of Surveyors Conference, Washington, DC, USA, March 9–10. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, Rohan, Jude Wallace, and Ian Phillip Williamson. 2008. A toolbox for mapping and managing new interests over land. Survey Review 40: 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binder, Claudia R. 2007. From material flow analysis to material flow management Part II: The role of structural agent analysis. Journal of Cleaner Production 15: 1605–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blacksell, Mark, and Karl Martin Born. 2002. Rural property restitution in Germany’s New Bundesländer: The case of Bergholz. Journal of Rural Studies 18: 325–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blacksell, M., K. M. Born, and M. Bohlander. 1996. Settlement of Property Claims in Former East Germany. Geographical Review 86: 198–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BLG. 2015. Non-profit Making Land Companies in Germany. Available online: http://www.aeiar.eu/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/Landgesellschaften-deutsch_engl.pdf (accessed on 26 June 2018).

- Borras, Saturnino M., Jr., and Jennifer C. Franco. 2010. Contemporary Discourses and Contestations around Pro-Poor Land Policies and Land Governance. Journal of Agrarian Change 10: 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BVVG. 2016. BVVG auf neue Vorgaben Ausgerichtet: Struktur an gesunkenenFlächenbestand Angepasst. Berlin: BVVG. [Google Scholar]

- Carmona, Matthew. 2017. The formal and informal tools of design governance. Journal of Urban Design 22: 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartier, Carolyn L. 2001. Globalizing South China. Malden: Blackwell Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, Peter T. Y. 2014. Toward collaborative governance between Hong Kong and Mainland China. Urban Studies 52: 1915–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottrell, Jill. 1997. Legal Research: A Guide for Hong Kong Students. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Czada, R. 1996. The Treuhandanstalt and the Transition from Socialism to Capitalism. In A New German Public Sector? Reform, Adaptation and Stability. Edited by Arthur Benz and Klaus H. Goetz. London: Dartmouth Publishing Company, pp. 93–117. [Google Scholar]

- Deininger, Klaus, and Gershon Feder. 2009. Land Registration, Governance, and Development: Evidence and Implications for Policy. The World Bank Research Observer 24: 233–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dells, Katja. 2008. Management and privatisation of state-owned agricultural land. Paper presented at the FAO/CNG International Seminar on State and Public Sector Land Management, Verona, Italy, September 9–10. Case Studies from Eastern Germany and Ukraine. Lessons Learned for Countries in Transition. [Google Scholar]

- Dells, Katja. 2012. Land Market Development in Eastern Germany. Paper presented at the 2012 FAO Workshop, Budapest, Hungary, February 13–16. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, Xiaoping. 1993. Selected Works of Deng Xiaoping Volume III (Deng Xiaoping Wenxuan Disanjuan). Beijing: Renming Press. [Google Scholar]

- Enemark, Stig. 2012. Sustainable land governance: Three key demands. Paper presented at FIG Working Week 2012, Rome, Italy, May 6–10. [Google Scholar]

- Fong, Brian C. H. 2014. The Partnership between the Chinese Government and Hong Kong’s Capitalist Class: Implications for HKSAR Governance, 1997–2012. The China Quarterly 217: 195–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, Brian C. H. 2017. One Country, Two Nationalisms: Center-Periphery Relations between Mainland China and Hong Kong, 1997–2016. Modern China 43: 523–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forstner, Bernhard. 2011. Aktivitäten von Nichtlandwirtschaftlichen und Überregional Ausgerichteten Investoren auf dem Landwirtschaftlichen Bodenmarkt in Deutschland. Braunschweig: Johann Heinrich von Thünen-Institut, Bundesforschungsanstalt für Ländliche Räume, Wald und Fischerei. [Google Scholar]

- Giddens, Anthony. 1976. New Rules of Sociological Method: A Positive Critique of Interpretative Sociology. London: Hutchinson. [Google Scholar]

- Giddens, Anthony. 1979. Central Problems in Social Theory: Action, Structure, and Contradiction in Social Analysis. Oakland: Univ of California Press, vol. 241. [Google Scholar]

- Giddens, Anthony. 1984. The constitution of society. Cambridge: Polity. [Google Scholar]

- GPHURD. 2011. Regional Cooperation Plan on Building a Quality Living Area Consultation Document; Guangzhou: Guangdong Provincial Government.

- Hawerk, W. 2001. ALKIS®–Germany’s Way into a Cadastre for the 21st Century. Paper presented at the FIG Working Week, Seoul, Korea, May 6–11. [Google Scholar]

- Henstra, Daniel. 2016. The tools of climate adaptation policy: Analysing instruments and instrument selection. Climate Policy 16: 496–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herre, Roman. 2013. Land Concentration, Land Grabbing and People’s Struggles in Europe. Amsterdam: Transnational Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, Sze-mun Vivian. 2001. The Land Administration System in Hong Kong. Hong Kong: The Hong Kong Polytechnic University. [Google Scholar]

- Hood, Christopher. 1983. The Tools of Government Chatham House Publishers. Chatham: Chatham House. [Google Scholar]

- Hood, Christopher C., and Helen Z. Margetts. 2007. The Tools of Government in the Digital Age. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Howlett, Michael. 2009. Government communication as a policy tool: A framework for analysis. Canadian Political Science Review 3: 23–37. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Daquan, Yuncheng Huang, Xingshuo Zhao, and Zhen Liu. 2017. How Do Differences in Land Ownership Types in China Affect Land Development? A Case from Beijing. Sustainability 9: 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huettel, Silke, Martin Odening, Karin Kataria, and Alfons Balmann. 2013. Price Formation on Land Market Auctions in East Germany—An Empirical Analysis. Journal of International Agricultural Trade and Development 62: 99. [Google Scholar]

- Hüttel, Silke, Lutz Wildermann, and Carsten Croonenbroeck. 2016. How do institutional market players matter in farmland pricing? Land Use Policy 59: 154–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillard, Jesse F., John T. Rigsby, and Carrie Goodman. 2004. The making and remaking of organization context: Duality and the institutionalization process. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal 17: 506–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Xu, and Anthony Yeh. 2009. Decoding Urban Land Governance: State Reconstruction in Contemporary Chinese Cities. Urban Studies 46: 559–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, Matthew R., and Helena Karsten. 2008. Giddens’s Structuration Theory and Information Systems Research. MIS Quarterly 32: 127–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koester, Ulrich E., and Karen M. Brooks. 1997. Agriculture and German Reunification. Washington: World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Kresse, Stefan, Katja Dells, and Hans-Egbert von Arnim. 2004. The East German Experience—A Model for SEE/MEE/CIS Countries? Paper presented at International Workshop on Land Banking: Land Funds as an Instrument for Improved Land Management in CEEC and CIS, Tonder, Denmark, March 17–20. [Google Scholar]

- Kuchar, Detlev, and Andreas Gläsel. 2006. Addressing Good Governance in the Privatisation and Restitution of State Assets (Land and Property) during the German Reunification Process. Paper presented at the FAO SDAA Expert Meeting, Rome, Italy, September 25–27. [Google Scholar]

- Kuchar, Detlev, and Andreas Gläsel. 2007. Addressing Good Governance in the Process of Privatization and Restitution of Agricultural Land during the German Reunification Process. Roma: Reforma Agraria, Colonizacion y Cooperativas (FAO). [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, Ravinder. 2002. India: A ‘nation-state’ or ‘civilisation-state’? South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies 25: 13–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuti, Csongor. 2009. Post-Communist Restitution and the Rule of Law. Budapest: Central European University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lascoumes, Pierre, and Patrick Le Gales. 2007. Introduction: Understanding Public Policy through Its Instruments—From the Nature of Instruments to the Sociology of Public Policy Instrumentation. Governance 20: 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Layder, Derek. 2005. Understanding Social Theory. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Lebow, Richard Ned. 2007. Coercion, Cooperation, and Ethics in International Relations. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Cheonjae, and Walter Timo de Vries. 2018. A divided nation: Rethinking and rescaling land tenure in the Korean (re-)unification. Land Use Policy 75: 127–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Ling Hin. 1999. Impacts of land use rights reform on urban development in China. Review of Urban & Regional Development Studies 11: 193–205. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L. H., K. G. McKinnell, and A. Walker. 2000. Convergence of the land tenure systems of China, Hong Kong and Taiwan? Journal of Property Research 17: 339–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Pak Wai. 2015. Land Premium and Hong Kong Government Budget: Myths and Realities. IGEF Working Paper No. 19. Hong Kong: The Chinese University of Hong Kong. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macintosh, Norman B., and Robert W. Scapens. 1990. Structuration theory in management accounting. Accounting, Organizations and Society 15: 455–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonnell, Lorraine M., and Richard F. Elmore. 1987. Getting the Job Done: Alternative Policy Instruments. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 9: 133–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller-Jökel, R. 2001. German Land Readjustment-Ecological, Economic and Social Land Management. Paper presented at FIG Working Week, Seoul, Korea, May 6–11. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, Mee Kam, and Wing-Shing Tang. 1999. Land-use planning in ‘one country, two systems’: Hong Kong, Guangzhou and Shenzhen. International Planning Studies 4: 7–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nissim, Roger. 2012. Land Administration and Practice in Hong Kong, 3rd ed. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. 2010. OECD Territorial Reviews: Guangdong, China 2010. Paris: OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Orlikowski, Wanda J. 2000. Using Technology and Constituting Structures: A Practice Lens for Studying Technology in Organizations. Organization Science 11: 404–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortmann, Gerald F. 1998. Structural changes and experiences with land reform in german agriculture since unification/strukturele veranderinge en ervarings met grondhervorming in die duitse landbou sedert hereniging. Agrekon 37: 213–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, David, Szilard Fricska, and Babette Wehrmann. 2009. Towards Improved Land Governance. Nairobi: UN-HABITAT. [Google Scholar]

- Poole, Marshall Scott, and Gerardine DeSanctis. 2004. Structuration theory in information systems research: Methods and controversies. In The Handbook of Information Systems Research. Hershey: IGI Global, pp. 206–49. [Google Scholar]

- Pozzebon, Marlei, Dale Mackrell, and Susan Nielsen. 2014. Structuration bridging diffusion of innovations and gender relations theories: A case of paradigmatic pluralism in IS research. Information Systems Journal 24: 229–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rithmire, Meg Elizabeth. 2017. Land Institutions and Chinese Political Economy: Institutional Complementarities and Macroeconomic Management. Politics & Society 45: 123–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salamon, Lester M. 2000. The new governance and the tools of public action: An introduction. Fordham Urb. LJ 28: 1611. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, Anne, and Helen Ingram. 1990. Behavioral Assumptions of Policy Tools. The Journal of Politics 52: 510–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz, Roland W., and Olaf Tietje. 2002. Embedded Case Study Methods: Integrating Quantitative and Qualitative Knowledge. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- So, Alvin Y. 2011. “One Country, Two Systems” and Hong Kong-China National Integration: A Crisis-Transformation Perspective. Journal of Contemporary Asia 41: 99–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stones, Rob. 2005. Structuration Theory. London: Macmillan International Higher Education. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, Rong, Volker Beckmann, Leo van den Berg, and Futian Qu. 2009. Governing farmland conversion: Comparing China with the Netherlands and Germany. Land Use Policy 26: 961–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiel, Fabian. 2010. Property, Planning and the “Homo Cooperativus”—Land as a Natural Resource with a Strong Public Interest. ZBF-UCB Working Paper No. 7. Birkenfeld: ZBF-UCB. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, Joachim. 2006. Attempt on systematization of land consolidation approaches in Europe. Zeitschrift für Vermessungswesen 3: 156–61. [Google Scholar]

- Tommy, Cheung. 2015. “Father” of Hong Kong nationalism? A critical review of Wan Chin’s city-state theory. Asian Education and Development Studies 4: 460–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker-Mohl, Jessica, and Annette Kim. 2005. Property Rights and Transitional Justice: Restitution in Hungary and East Germany. MIT OpenCourseWare Urban Studies and Planning. Available online: http://ocw.mit.edu/NR/rdonlyres/Urban-Studies-and-Planning/11-467JSpring-2005 (accessed on 15 January 2018).

- Vabo, Signy Irene, and Asbjørn Røiseland. 2012. Conceptualizing the Tools of Government in Urban Network Governance. International Journal of Public Administration 35: 934–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vedung, Evert. 1998. Policy instruments: Typologies and theories. In Carrots, Sticks and Sermons. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers, pp. 21–58. [Google Scholar]

- Vogel, Ronald K., H. V. Savitch, Jiang Xu, Anthony G. O. Yeh, Weiping Wu, Andrew Sancton, Paul Kantor, Peter Newman, Takashi Tsukamoto, Peter T. Y. Cheung, and et al. 2010. Governing global city regions in China and the West. Progress in Planning 73: 1–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehrmann, Babette. 2010. Governance of Land Tenure in Eastern Europe and Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS). Rome: UN Food and Agriculture Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Whittington, Richard. 2015. Giddens, structuration theory and strategy as practice. In Cambridge Handbook of Strategy as Practice. Edited by Damon Golsorkhi, David Seidl, Eero Vaara and Linda Rouleau. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 145–64. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, Ian, Stig Enemark, Jude Wallace, and Abbas Rajabifard. 2010. Land Administration for Sustainable Development. Redlands: ESRI Press Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Wilsch, Harald. 2012. The German “Grundbuchordnung”: History, Principles and Future about Land Registry in Germany. Zeitschrift für Vermessungswesen 4: 224–33. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, Geoff A., and Olivia J. Wilson. 2001. German Agriculture in Transition: Society, Policies and Environment in a Changing Europe. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Wolz, Axel. 2012. The Transformation of the Agricultural Administration and Associations in East Germany Before and After Unification: Are There Lessons for the Korean Peninsula? Journal of Rural Development/Nongchon-Gyeongje 35: 19. [Google Scholar]

- Wolz, Axel. 2013. The Organisation of Agricultural Production in East Germany Since World War II: Historical Roots and Present Situation. Discussion Paper. Halle: Leibniz Institute of Agricultural Development in Central and Eastern Europe. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, Vince. 2014. Land Policy Reform in China: Dealing with Forced Expropriation and the Dual Land Tenure System. Occasional Paper 25. Hong Kong: The University of Hong Kong. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. 2014. China’s Urbanization and Land: A Framework for Reform. In Urban China: Toward Efficient, Inclusive, and Sustainable Urbanization. Washington: World Bank, pp. 263–336. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Fulong, Jiang Xu, and Anthony Gar-On Yeh. 2006. Urban Development in Post-Reform China: State, Market, and Space. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Mingtian. 2008. Spring’s Story: Shenzhen’s Entrepreneurial History: 1979–2009. Beijing: CITIC Publishing, vol. 1. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yin, Robert K. 2003. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 3rd ed. Applied Social Research Methods Series; Thousand Oaks: Sage, vol. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Zevenbergen, Jaap A. 2012. Handling Land: Innovative Tools for Land Governance and Secure Tenure. Nairobi: UN-HABITAT. [Google Scholar]

- Zevenbergen, Jaap, Walter de Vries, and Rohan Mark Bennett. 2015. Advances in Responsible Land Administration. Boca Raton: CRC Press, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Jun. 2012. From Hong Kong’s capitalist fundamentals to Singapore’s authoritarian governance: The policy mobility of neo-liberalising Shenzhen, China. Urban Studies 49: 2853–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Guobin. 2012. The composite state of China under “One Country, Multiple Systems”: Theoretical construction and methodological considerations. International Journal of Constitutional Law 10: 272–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | The North and South Korean (re-)unification quagmire is not new in the world. There are many divided countries in need of reunification and there are others that were once divided but finally became reunified. Countries like Cyprus (Turkish and Greek Cypriots), Sudan (Sudan and South Sudan), and Yemen (South and North Yemen) are some countries in need of reunification. China, Vietnam and Germany are examples of countries that were once divided and then became reunified. |

| 2 | According to Kumar (2002), a civilisation rests upon a mode of social production characterized by a specific set of social and political institutions and texture of moral values. The OCTS model mirrors the civilisation-state, which is a logical justification for the China-Hong Kong (re-)unification. It rests upon the notions that certain parts of the state, which previously had different values or systems, can retain those values if they accept the wider sovereignty of the civilization. This relationship is clear in the role that China has played in Hong Kong after (re-)unification occurred. In contrast, the nation-state rests upon a single centralized political institution. This forms the basis for the OCOS model. An example is the merger of East and West Germany in 1990. |

| Authority-Based Tools | Main Description | Focal Arenas | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| German Basic Law (Article 14) | Property and the right of inheritance shall be guaranteed. | (Private) property right | Thiel (2010) |

| Unification Treaty (Article 41 including Annex III) | States social equilibrium between the competing interests to protect the property right | Property restitution | (Blacksell et al. 1996; Blacksell and Born 2002; Kuti 2009) |

| German Civil Code (Article 233–237; Articles 585–597) | Contains rules regarding the transformation of property; stipulates legal procedures for land leasing | Property; land transaction | (Blacksell et al. 1996; Dells 2012) |

| The German Land Register Code; Act for Acceleration of Register Processes | Initiates transformation from a paper to digital land register | Land registration | (Wilsch 2012) |

| The Federal Regional Planning Act; Federal Building Code | Transform land-use planning and development and Introduce spatial planning | Land & regional development; spatial planning | (Tan et al. 2009) |

| Real Property Transaction Act; Land Lease Transaction Act; Empire Settlement Act | Supports Setting up transparent (re-)unified land market | Land market | (Dells 2012) |

| The Investment Acceleration Law; Investment Priority Law | elaborated procedures to support sales of land and encouraged new investment | Economic development; restitution | (Blacksell and Born 2002; Tucker-Mohl and Kim 2005) |

| Property Restitution Law | Highlights land and property expropriated illegally was to be returned to the former owners | Property restitution | (Blacksell and Born 2002) |

| Property Law; Allocation of Ownership Act | Set out the opening clauses by agreement for speeding up the transformation process and reducing the administrative costs | Property restitution | (Kuchar and Gläsel 2007; Thiel 2010) |

| Trusteeship Law | Stipulates establishment of the THA | Property restitution | (Ortmann 1998) |

| the Law on Adjustment of Agriculture; the Federal Land Consolidation Act | Specify rearrangement and adjustment of land in rural areas | Rural development; restitution | (Koester and Brooks 1997; Thomas 2006) |

| the Indemnification and Compensation Act; Land Purchase Implementing Regulation | Eastern German farmers were given the first chance to amplify spatial resources by obtaining previous state-owned land through special conditions | Privatization; Land purchase; rural development | (Thiel 2010) |

| The Valuation Ordinance | Determines the market value of land through standardized valuation methods | Land valuation | (Kuchar and Gläsel 2007) |

| Year | (a) | (b) | (c) | (d) | (e) | (f) | (g) | (h) | (h):(a) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1999 | 559,487 | 31,257 | 5906 | - | 3303 | - | 51,433 | 91,899 | 16.4% |

| 2000 | 640,606 | 34,896 | 6476 | - | 3532 | - | 59,558 | 104,462 | 16.3% |

| 2001 | 780,330 | 38,062 | 6615 | - | 3833 | - | 129,589 | 178,099 | 22.8% |

| 2002 | 851,500 | 46,711 | 7683 | - | 5734 | - | 241,679 | 301,807 | 35.4% |

| 2003 | 984,998 | 54,671 | 9157 | - | 3990 | - | 542,131 | 609,949 | 61.9% |

| 2004 | 1,189,337 | 66,974 | 10,623 | - | 12,008 | - | 641,218 | 730,823 | 61.4% |

| 2005 | 1,510,076 | 79,102 | 13,734 | - | 14,185 | - | 588,382 | 695,403 | 46.1% |

| 2006 | 1,830,358 | 93,343 | 93,343 | - | 17,112 | - | 807,764 | 1,011,562 | 55.3% |

| 2007 | 2,357,262 | 114,870 | 38,549 | - | 18,504 | - | 1,221,672 | 1,393,595 | 59.1% |

| 2008 | 2,864,979 | 133,630 | 81,690 | 53,743 | 31,441 | 68,034 | 1,025,980 | 1,394,518 | 48.7% |

| 2009 | 3,260,259 | 141,992 | 92,098 | 71,956 | 63,307 | 80,366 | 1,717,953 | 2,167,672 | 66.5% |

| 2010 | 4,061,304 | 173,627 | 100,401 | 127,829 | 88,864 | 89,407 | 2,746,448 | 3,326,576 | 81.9% |

| 2011 | 5,254,711 | 277,929 | 122,226 | 206,261 | 107,546 | 110,239 | 3,212,608 | 4,036,809 | 76.8% |

| 2012 | 6,107,829 | 312,563 | 154,172 | 271,906 | 162,071 | 137,249 | 2,804,228 | 3,842,189 | 62.9% |

| 2013 | 6,901,116 | 341,990 | 171,877 | 329,391 | 180,823 | 158,150 | 3,907,299 | 5,089,530 | 73.7% |

| 2014 | 7,587,658 | 364,461 | 199,262 | 391,468 | 205,905 | 185,164 | 4,038,586 | 5,384,846 | 71.0% |

| 2015 | 8,300,204 | 388,632 | 214,204 | 383,218 | 209,721 | 205,090 | 3,078,380 | 4,479,245 | 54.0% |

| 2016 | 8,485,000 | 403,360 | 225,574 | 421,219 | 202,889 | 222,091 | 3,563,969 | 5,039,102 | 59.4% |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, C.; de Vries, W.T.; Chigbu, U.E. Land Governance Re-Arrangements: The One-Country One-System (OCOS) Versus One-Country Two-System (OCTS) Approach. Adm. Sci. 2019, 9, 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci9010021

Lee C, de Vries WT, Chigbu UE. Land Governance Re-Arrangements: The One-Country One-System (OCOS) Versus One-Country Two-System (OCTS) Approach. Administrative Sciences. 2019; 9(1):21. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci9010021

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Cheonjae, Walter Timo de Vries, and Uchendu Eugene Chigbu. 2019. "Land Governance Re-Arrangements: The One-Country One-System (OCOS) Versus One-Country Two-System (OCTS) Approach" Administrative Sciences 9, no. 1: 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci9010021

APA StyleLee, C., de Vries, W. T., & Chigbu, U. E. (2019). Land Governance Re-Arrangements: The One-Country One-System (OCOS) Versus One-Country Two-System (OCTS) Approach. Administrative Sciences, 9(1), 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci9010021