Reviewing the Online Tourism Value Chain

Abstract

1. Introduction

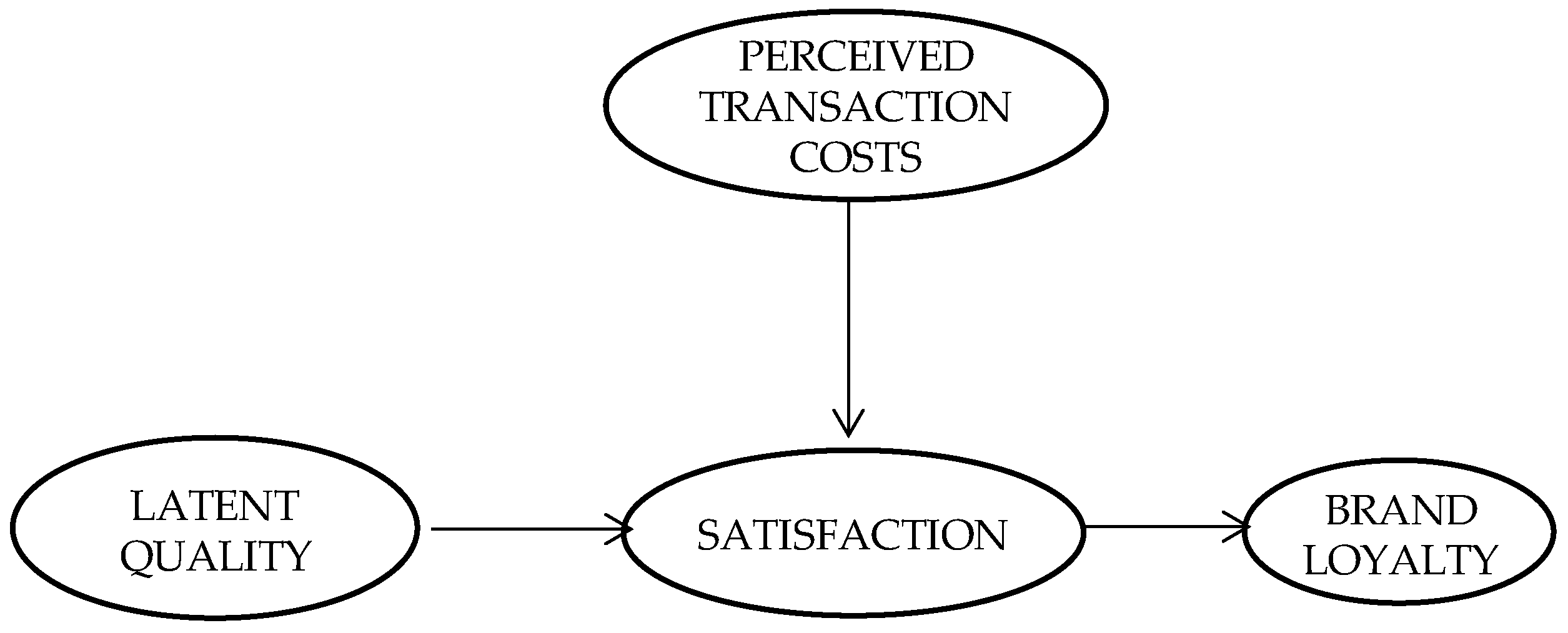

- Do the basic relationships of the quality-satisfaction-loyalty value chain validated in other contexts, work in the same way in online tourism?

- What is the role of the perceived transaction costs (relative to the customer’s participation in the co-production of the online channel tourism service) in the value chain?

2. Literature Antecedents and Theoretical Model

2.1. The Online Tourism Quality-Satisfaction-Loyalty Value Chain

2.2. The Role of Perceived Costs

3. Research Methods

3.1. Measures

3.2. Data Collection

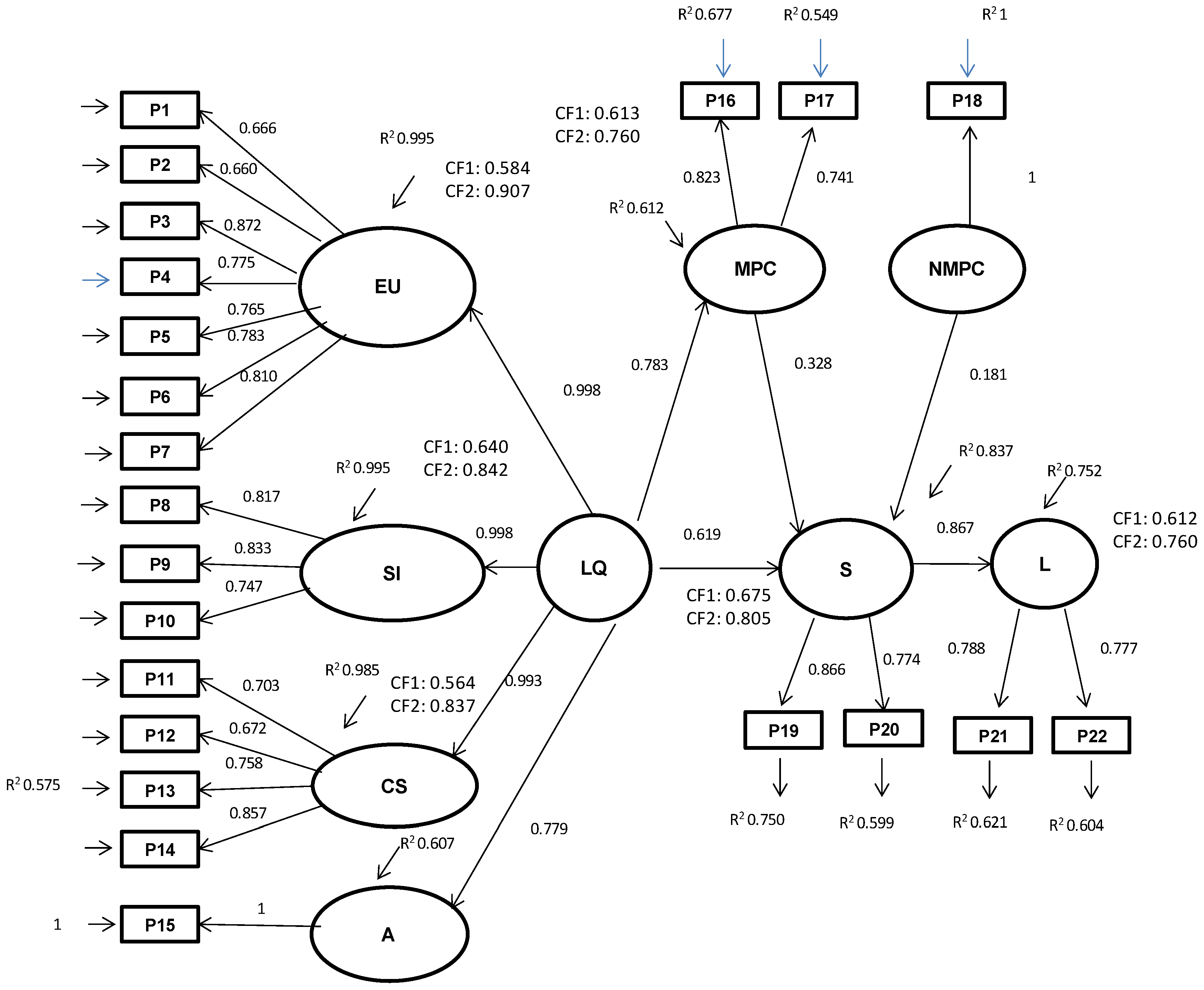

4. Results

4.1. Ease-of-Use Measurement Model

4.2. Service Information Measurement Model

4.3. Customer Service Measurement Model

4.4. Perceived Costs Measurement Model

4.5. Satisfaction and Loyalty Measurement Models

4.6. e-TPP Model

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahn, Tony, Seewon Ryu, and Ingoo Han. 2007. The impact of web quality and playfulness on user acceptance of online retailing. Information Management 44: 263–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aladwani, Adel M., and Prashant C. Palvia. 2002. Developing and validating an instrument for measuring user-perceived website quality. Information and Management 39: 467–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Faizan. 2016. Hotel website quality, perceived flow, customer satisfaction and purchase intention. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Technology 7: 213–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Faizan, Abdul Khan, and Fatin Rehman. 2012. An assessment of the service quality using gap analysis: A study conducted at Chitral, Pakistan. Interdisciplinary Journal of Contemporary Research in Business 4: 259–66. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, Faizan, Muslim Amin, and Cihan Cobanoglu. 2016. An Integrated Model of Service Experience, Emotions, Satisfaction, and Price Acceptance: An Empirical Analysis in the Chinese Hospitality Industry. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management 25: 449–75. [Google Scholar]

- Amaro, Suzzane, and Paulo Duarte. 2015. An integrative model of consumers’ intentions to purchase travel. Tourism Management 46: 64–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, Muslim, and Siti Z. Nasharuddin. 2013. Hospital service quality and its effects on patient satisfaction and behavioural intention. Clinical Governance: An International Journal 18: 238–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, Eugene W., Claes Fornell, and Donald R. Lehmann. 1994. Satisfaction, market share, and profitability: Findings from Sweden. Journal of Marketing 58: 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrondo, Elvira, Carmen Berné, José M. Múgica, and Pilar Rivera. 2002. Modelling of customer retention in multi-format retailing. The International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research 12: 281–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Billy, Rob Law, and Ivan Wen. 2008. The impact of website quality on customer satisfaction and purchase intentions: Evidence from Chinese online visitors. International Journal of Hospitality Management 27: 391–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, Stuart J., and Richard T. Vidgen. 2014. Technology socialness and website satisfaction. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 89: 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, Hans H., Tomas Falk, and Maik Hammerschmidt. 2006. eTransQual: A Transaction Process- Based Approach for Capturing Service Quality in Online Shopping. Journal of Business Research 59: 866–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berné, Carmen, José M. Múgica, and María J. Yagüe. 1996. La gestión estratégica y los conceptos de calidad percibida, satisfacción del cliente y lealtad. Economía Industrial 307: 63–74. [Google Scholar]

- Berné, Carmen, José M. Múgica, and Pilar Rivera. 2005. The managerial ability to control the varied behavior of regular customers in retailing: Interformat differences. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 12: 151–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betancourt, Rogert R., Raquel Chocarro, Monica Cortiñas, Margarita Elorz, and José M. Mugica. 2016. Channel choice in the 21st century: The hidden role of distribution services. Journal of Interactive Marketing 33: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betancourt, Rogert R., Raquel Chocarro, Monica Cortiñas, Margarita Elorz, and José M. Mugica. 2017. Private sales clubs: A 21st. Century distribution channel. Journal of Interactive Marketing 37: 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunduchi, Raluca. 2005. Business relationship in Internet-base electronic markets: The role of Goodwill trust and transaction costs. Information Systems Journal 15: 321–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Hisn H., and Su W. Chen. 2008. The impact of online store environment cues on purchase intention: Trust and perceived risk as a mediator. Online Information Review 32: 818–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chathoth, Prakash, Levent Altinay, Robert J. Harrington, Fevzi Okumus, and Eric S.W. Chan. 2013. Co-production versus co-creation: A process based continuum in the hotel service context. International Journal of Hospitality Management 32: 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Ching-Fu, and Fu-Shian Chen. 2010. Experience quality, perceived value, satisfaction and behavioral intentions for heritage tourists. Tourism Management 13: 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Ganghua, and Honggen Xiao. 2013. Motivations of repeat visits: A longitudinal study in Xiamen, China. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing 30: 350–64. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu, Chao-Min, Eric T. G. Wang, Yu-Hui Fang, and Hsin-Yi Huang. 2014. Understanding customers’repeat purchase intentions in B2C e-commerce: The roles of utilitarian value and perceived risks. Information Systems Journal 24: 85–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Yoon C., and Jerome Agrusa. 2006. Assessing use acceptance and satisfaction toward online travel agencies. Information Technology & Tourism 8: 179–95. [Google Scholar]

- Cronin, Joseph J., and Steven A. Taylor. 1992. Measuring service quality: A reexamination and extension. Journal of Marketing 56: 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronin, Joseph, Michael Brady, and Tomas Hult. 2000. Assessing the effects of quality, value and customer satisfaction on consumer behavioral intentions in service environments. Journal of Retailing 76: 193–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darsono, Licen Indahwati, and Marliana C. Junaedi. 2006. An Examination of Perceived Quality, Satisfaction, and Loyalty Relationship: Applicability of Comparative and Noncomparative Evaluation. Gadjah Mada International Journal of Business 8: 323–42. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, Wei-Jaw, Ming Lang Yeh, and M. L. Sung. 2013. A customer satisfaction index model for international tourist hotels: Integrating consumption emotions into the American customer satisfaction index. International Journal of Hospitality Management 35: 133–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donthu, Naveen. 2001. Does your web site measure up? Marketing Management 10: 29–32. [Google Scholar]

- Etgar, Michael. 2006. Co-production of services: A managerial extension. In The Service-Dominant Logic of Marketing: Dialog, Debate and Directions. Edited by Robert Lusch and Stephen Vargo. New York: Sharpe, pp. 128–38. [Google Scholar]

- Etgar, Michael. 2008. A descriptive model of the consumer co-production process. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 36: 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, Adam, Luming Wang, and Tema Frank. 2009. Attribute perceptions, customer satisfaction and intention to recommend e-services. Journal of Interactive Marketing 23: 209–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friesen, Bruce G. 2001. Co-creation: When 1 and 1 make 11. Consulting to Management 12: 28–31. [Google Scholar]

- Gallarza, Martina, Irene Gil, and Francisco Moreno. 2013. The quality-value-satisfaction-loyalty chain: Relationships and impacts. Tourism Review 68: 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesh, Jaishankar, Kristy E. Reynolds, Michael Luckett, and Nadia Pomirleanu. 2010. Online shopper motivations, and e-store attributes: An examination of online patronage behavior and shopper typologies. Journal of Retailing 86: 106–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, Franciso, and Pablo Garrido. 2013. Agencias de viaje online en España: Aplicación de un modelo de análisis de sedes web. Revista de Investigación en Turismo y Desarrollo Local 6: 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- González, María E. A., Lorenzo Comesaña, and José A. F. Brea. 2007. Assessing tourist behavioral intentions through perceived service quality and customer satisfaction. Journal of Business Research 60: 153–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewal, Dhruv, Kent B. Monroe, and Ram Krishnan. 1998. The effects of price-comparison advertising on buyer’s perceptions of acquisition value, transaction value, and behavioral intentions. Journal of Marketing 62: 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grissemann, Ursula S., and Nicola E. Stokburger-Sauer. 2012. Customer co-creation of travel services: The role of company support and customer satisfaction with the co-creation performance. Tourism Management 33: 1483–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Heesup, and Kisang Ryu. 2009. The roles of the physical environment, price perception, and customer satisfaction in determining customer loyalty in the restaurant industry. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Research 33: 487–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Heesup, and Kisang Ryu. 2012. Key factors driving customers’ word-of-mouth intentions in full-service restaurants: The moderating role of switching costs. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly 53: 96–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hann, Il-Horn, and Christian Terwiesch. 2003. Measuring the frictional costs of online transactions: The case of a name-your-own-price channel. Management Science 49: 1563–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Jing-Xing, Yan Yu, Rob Law, and Davis K. C. Fong. 2015. A genetic algorithm-based learning approach to understand customer satisfaction with OTA websites. Tourism Management 48: 231–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helgesen, Oyvind, Jon I. Havold, and Erik Nesset. 2010. Impacts of store and chain images on the “quality-satisfaction-loyalty process” in petrol retailing. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 17: 109–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heskett, James L., Thomas O. Jones, Gary W. Loveman, Earl W. Sasser, and Leonard A. Schlesinger. 2008. Putting the service-profit chain to work. Harvard Business Review 86: 118–29. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, Enoch, Elaine Principi, Charissa P. Cordon, Yavra Amenudzie, Krista Kotwa, Sarah Holt, and Maura MacPhee. 2017. The synergy tool: Making important quality gains within one healthcare organization. Administrative Sciences 7: 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, Shin-Yuan, Charlie Chen, and Ning-Hung Huang. 2014. An integrative approach to understanding customer satisfaction with e-service of online stores. Journal of Electronic Commerce Research 15: 40–57. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, Barbara B. 1985. Winning and Keeping Industrial Customers: The Dynamics of Customer Relationship. Lexington: Lexington Books. [Google Scholar]

- Jaiswal, Anand A., Rakesh Niraj, and Pingali Venugopal. 2010. Context-general and context-specific determinants of online satisfaction and loyalty for commerce and content sites. Journal of Interactive Marketing 24: 222–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, Miyoung, and Carolyn U. Lambert. 2001. Adaptation of an information quality framework to measure customers’ behavioral intentions to use lodging websites. International Journal of Hospitality Management 20: 129–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Pingjun, and Bert Rosenbloom. 2005. Customer intention to return online: Price perception, attribute-level performance, and satisfaction unfolding over time. European Journal of Marketing 39: 150–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandampully, Jan, and Dwi Suhartanto. 2000. Customer loyalty in the hotel industry: The role of customer satisfaction and image. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 12: 346–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaynama, Shohreh, and Christine Black. 2000. A proposal to assess the service quality of online travel agencies: An exploratory study. Journal of Professional Service Marketing 21: 63–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Woo G., and Hae Y. Lee. 2004. Comparison of web service quality between online travel agencies and online travel suppliers. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing 17: 105–16. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Seong-Seop, and Choong-Ki Lee. 2005. Push and pull relationships. Annals of Tourism Research 29: 257–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Lisa H., Dong J. Kim, and Jerrold K. Leong. 2005. The effect of perceived risk on purchase intention in purchasing airline tickets online. Journal of Hospitality & Leisure Marketing 13: 33–53. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Myung-Ja, Namho Chung, and Choong-Ki Lee. 2011. The effect of perceived trust on electronic commerce: Shopping online for tourism products and services in South Korea. Tourism Management 32: 256–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamurthi, Lakshman, and S. P. Raj. 1988. A Model of Brand Choice and Purchase Quantity Price Sensitivities. Marketing Science 7: 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, Kenneth S., Wong Chi-Sum, and William H. Mobley. 1998. Toward a taxonomy of multidimensional constructs. Academy of Management Review 23: 741–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, Rob, Shanshan Oi, and Dimirtios Buhalis. 2010. Progress in tourism management: A review of website evaluation in tourism research. Tourism Management 31: 297–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llach, Josep, Frederic Marimon, María M. Alonso-Almeida, and Merce Bernardo. 2013. Determinants of online booking loyalties for the purchasing of airline tickets. Tourism Management 35: 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Mary, and Chareles McMellon. 2004. Exploring the determinants of retail service quality on the Internet. Journal of Service Marketing 18: 78–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madu, Christian N., and Assumpta A. Madu. 2002. Dimensions of e-quality. International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management 19: 246–58. [Google Scholar]

- Noone, Breffni M., and Anna S. Mattila. 2009. Hotel revenue management and the Internet: The effect of price presentation strategies on customers’ willingness to book. International Journal of Hospitality Management 28: 272–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, Jum. 1978. Psychometric Methods. New York: McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, Richard L. 2010. Satisfaction: A Behavioral Perspective on the Consumer, 2nd ed. Armonk: M.E. Sharpe. [Google Scholar]

- Olsen, Svein O. 2002. Comparative evaluation and the relationship quality, satisfaction and repurchase loyalty. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 30: 240–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oskan, Jeroen, and Tjeerd Zandberg. 2016. Who will sell your rooms? Hotel distribution scenarios. Journal of Vacation Marketing 22: 265–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, Ahmet B., Anil Bilgihan, Khaldoon Nusair, and Fevzi Okumus. 2016. What keeps the mobile hotel booking users loyal? Investigating the roles of self-efficacy, compatibility, perceived ease of use, and perceived convenience. International Journal of Information Management 36: 1350–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, A., Valarie A. Zeithaml, and Arvind Malhotra. 2005. ES-QUAL a multiple-item scale for assessing electronic service quality. Journal of Service Research 7: 213–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Young A., and Ulrike Gretzel. 2007. Success factors for destination marketing web sites: A qualitative meta-analysis. Journal of Travel Research 46: 46–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Young A., Ulrike Gretzel, and Ercan Sirakaya-Turk. 2007. Measuring web site quality for online travel agencies. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing 23: 15–30. [Google Scholar]

- Petter, Stacie, Detmar Straub, and Arun Rai. 2007. Specifying formative constructs in information systems research. MIS Quarterly 31: 623–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponte, Enrique B., Elena Carvajal-Trujilo, and Tomás Escobar-Rodriguez. 2015. Influence of trust and perceived value on the intention to purchase travel online: Integrating the effects of assurance on trust antecedents. Tourism Management 47: 286–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prahalad, Coimbatore Krishna, and Venkat Ramaswamy. 2004. Co-creation experiences: The next practice in value creation. Journal of Interactive Marketing 18: 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prahalad, Coimbatore Krishna, and Venkat Ramaswamy. 2013. The Future of Competition: Co-Creating Unique Value with Customers. Boston: Harvard Business School Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Mafe, Carla, Enrique Bigne-Alcañiz, Silvia Sanz-Blas, and José Tronch. 2018. Does social climate influence positive Ewom? A study of heavy-users of online communities. BRQ Business Research Quarterly. in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, Kisang, Lee Hye-Rin, and Woo Kim. 2012. The influence of the quality of the physical environment, food, and service on restaurant image, customer perceived value, customer satisfaction, and behavioral intentions. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 24: 200–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmiento, José R. 2016. El impacto de los medios sociales en la estructura del sistema de distribución turístico: Análisis y clasificación de los nuevos proveedores de servicios turísticos en el entorno online. Cuadernos de Turismo 36: 459–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauro, Jeff. 2015. SUPR-Q: A comprehensive measure of the quality of the website user experience. Journal of Usability Studies 10: 68–86. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, Gareth, Adrian Bailey, and Allan Williams. 2011. Aspects of service-dominant logic and its implications for tourism management: Examples from the hotel industry. Tourism Management 32: 217–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seiders, Kathleen, Glenn B. Voss, Andrea L. Godfrey, and Dhruv Grewal. 2007. SERVCON: Development and Validation of a Multidimensional Service Convenience Scale. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 35: 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigala, Marianna, and Odysseas Sakellaridis. 2004. The impact of users’ cultural characteristics on e-service quality: Implications for globalizing tourism and hospitality web sites. In Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism. Edited by A. Frew. Vienna: Springer Verlag, pp. 106–17. [Google Scholar]

- Stangl, Brigitte, Alessandro Inversini, and Roland Schegg. 2016. Hotel’s dependency on online intermediaries and their chosen distribution channel portfolios: Three country insights. International Journal of Hospitality Management 16: 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockdale, Rosemary. 2007. Managing customer relationships in the self-service environment of e-tourism. Journal of Vacation Marketing 13: 205–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban, Glen, Cinda Amyx, and Antonio Lorenzon. 2009. Online trust: State of the art, new frontiers, and research potential. Journal of Interactive Marketing 23: 179–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargo, Stephen L., and Robert F. Lusch. 2004. Evolving to a new dominant logic for marketing. Journal of Marketing 68: 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargo, Stephen L., and Robert F. Lusch. 2008. Service-dominant logic: Continuing the evolution. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 36: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez, Rodolfo, Ana B. Del Río, and Leticia Suárez. 2009. Virtual travel agencies: Analysing the e-service quality and the effect on customer satisfaction. Universia Business Review 24: 122–43. [Google Scholar]

- Verhoef, Peter C., Scott A. Neslin, and Björn Vroomen. 2007. Multichannel customer management: Understanding the research-shopper phenomenon. International Journal of Research in Marketing 24: 129–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Liang, Rob Law, Basak D. Guillet, Kam Hung, and Davis K.C. Fong. 2015. Impact of hotel website quality on online booking intentions, eTrust as a mediator. International Journal of Hospitality Management 47: 108–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, Timothy. 2016. From travel agents to OTAs: How the evolution of consumer booking behaviour has affected revenue management. Journal of Revenue and Pricing Management 13: 276–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Zhilin, and Minjoon Jun. 2002. Consumer perception of e-service quality: From Internet purchaser and non-purchaser perspectives. Journal of Business Strategies 19: 19–41. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, Qiang, Rob Law, Bin Gu, and Wei Chen. 2011. The influence of user-generated content on traveler behavior: An empirical investigation on the effects of e-word-of-mouth to hotel online bookings. Computers in Human Behavior 27: 634–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yüksel, Atila, Fisun Yüksel, and Yasin Bilim. 2010. Destination attachment: Effects on customer satisfaction and cognitive, affective and conative loyalty. Tourism Management 31: 274–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, Valarie A. 1988. Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: A means-end model and synthesis of evidence. The Journal of Marketing 52: 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, Valarie A., Leonard L. Berry, and A. Parasuraman. 1996. The behavioral consequences of service quality. Journal of Marketing 60: 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Criteria, Items | Prior References * |

|---|---|

| Ease-of-use P1. Ease of access to the web page. P2. Possibility offered by the company to combine tourism products in a single order. P3. Perceived clarity (ease of identification) about the company’s products and services on its web page. P4. Preciseness (absence of ambiguity) of the definition of the products and services on the company’s web page. P5. Purchase payment modes offered through the online service.P6. Task of consumers in the event that they may have combined products in the last transaction or in other, previous transactions with the same company to get the desired combination. P7. Time used to finalise the purchase. | Kaynama and Black (2000); Donthu (2001); Jeong and Lambert (2001); Madu and Madu (2002); Kim and Lee (2004); Kim et al. (2005); Park et al. (2007); Verhoef et al. (2007, buying time); Seiders et al. (2007, accessibility); Jaiswal et al. (2010); Ganesh et al. (2010, ease of payment); Ali (2016, usability) |

| Information attributes P8. The information provided by the company, online, for making the purchase. P9…provided by the company’s web page about the characteristics of the contracted tourism service. P10. … from the web page about the variety of the online tourism products-services offered by the company. | Kaynama and Black (2000); Jeong and Lambert (2001); Madu and Madu (2002); Kim and Lee (2004); Kim et al. (2005); Park et al. (2007); Verhoef et al. (2007); Ganesh et al. (2010) (merchandise variety), Hung et al. (2014); Ali (2016, functionality) |

| Customer service P11. Confirmation procedure of the booking-purchase, discounts and/or invoices by the company. P12. … for cancelling the contracted online tourism service. P13. Customer service and/or complaints and claims system available on the company’s web page. P14. Privacy and security policy followed by the contracted online service with respect to the customer’s personal data. | Kaynama and Black (2000); Madu and Madu (2002); Kim and Lee (2004); Kim et al. (2005, security); Park et al. (2007); Jaiswal et al. (2010, privacy, security); Ali (2016, security and privacy) |

| Visual attraction P15. Attractiveness of the web page where the tourism service has been contracted. | Kaynama and Black (2000); Kim et al. (2005); Bauer et al. (2006); Urban et al. (2009); Ganesh et al. (2010); García and Garrido (2013) |

| Perceived costs P16. Prices of the service contracted online in relation to purchases in offline channels. P17. … with respect to other, similar online services. P18. Effort made in the online purchasing process versus the offline process. | Kim et al. (2011); García and Garrido (2013); Chiu et al. (2014, monetary savings); Verhoef et al. (2007, search and purchase effort) |

| Satisfaction P19. Overall satisfaction with the last purchase of tourism services contracted online (satisfaction with the last transaction). P20. Online purchasing experience over time with the last contracted company (accumulated satisfaction). | Arrondo et al. (2002); Berné et al. (2005); Finn et al. (2009, cummulative); Hung et al. (2014, cummulative); Betancourt et al. (2017, cummulative) |

| Brand/Company loyalty P21. Intention to continue using the same online tourism service. P22. Recommendation of the contracted online service. | Arrondo et al. (2002); Berné et al. (2005); Finn et al. (2009, repurchase); Chiu et al. (2014, repurchase); Betancourt et al. (2017, repurchase) |

| Sex | Male | 50.7% |

| Female | 49.3% | |

| Age | 18–30 | 28.2% |

| 31–55 | 46.6% | |

| Over 55 | 25.2% | |

| Education | Primary education | 1.5% |

| Secondary education (mandatory) | 6.6% | |

| Higher secondary education | 19.1% | |

| Uncompleted university studies | 10.5% | |

| Higher education (graduated and post-graduated) | 51.9% | |

| Vocational training (post-secondary) | 2.2% |

| d.f. | Chi-Square S-B | P | R-RMSEA | SRMR | GFI | AGFI | R-BBN | R-CFI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EU | 14 | 29.479 | 0.009 | 0.054 | 0.038 | 0.957 | 0.913 | 0.964 | 0.981 |

| SI | 2 | 0.6012 | 0.740 | 0.0001 | 0.029 | 0.996 | 0.988 | 0.998 | 0.999 |

| CS | 2 | 9.455 | 0.009 | 0.098 | 0.040 | 0.974 | 0.868 | 0.966 | 0.973 |

| PC | 2 | 23.872 | 0.0001 | 0.167 | 0.163 | 0.933 | 0.798 | 0.812 | 0.823 |

| S | 1 | 0.7593 | 0.384 | 0.0001 | 0.028 | 0.997 | 0.992 | 0.996 | 0.999 |

| L | 1 | 0.0017 | 0.967 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.999 |

| d.f. | Chi-Square S-B | P | R-RMSEA | SRMR | GFI | AGFI | R-BBN | R-CFI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| e-TPP | 202 | 412.8158 | 0.000 | 0.055 | 0.144 | 0.860 | 0.825 | 0.878 | 0.933 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Berne-Manero, C.; Gómez-Campillo, M.; Marzo-Navarro, M.; Pedraja-Iglesias, M. Reviewing the Online Tourism Value Chain. Adm. Sci. 2018, 8, 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci8030048

Berne-Manero C, Gómez-Campillo M, Marzo-Navarro M, Pedraja-Iglesias M. Reviewing the Online Tourism Value Chain. Administrative Sciences. 2018; 8(3):48. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci8030048

Chicago/Turabian StyleBerne-Manero, Carmen, Maria Gómez-Campillo, Mercedes Marzo-Navarro, and Marta Pedraja-Iglesias. 2018. "Reviewing the Online Tourism Value Chain" Administrative Sciences 8, no. 3: 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci8030048

APA StyleBerne-Manero, C., Gómez-Campillo, M., Marzo-Navarro, M., & Pedraja-Iglesias, M. (2018). Reviewing the Online Tourism Value Chain. Administrative Sciences, 8(3), 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci8030048