Positive Disposition in the Prediction of Strategic Independence among Millennials

Abstract

:1. Introduction

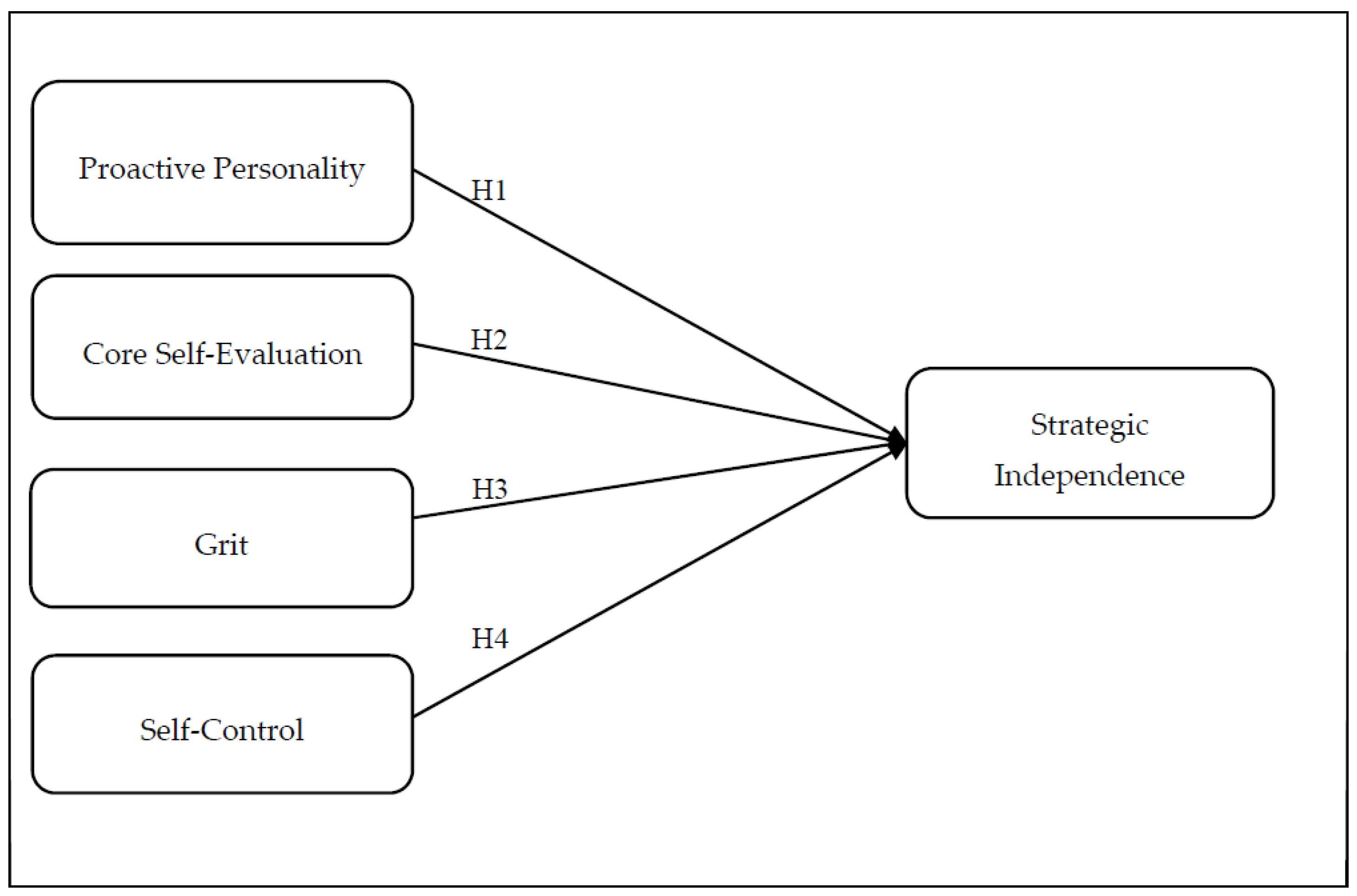

2. Nomological Network

3. Conceptual Foundation and Hypotheses

3.1. Strategic Independence

3.2. Predictor Variables

4. Research Methods

4.1. Procedure and Sample Participants

4.2. Measures

4.3. Data Analysis

5. Results

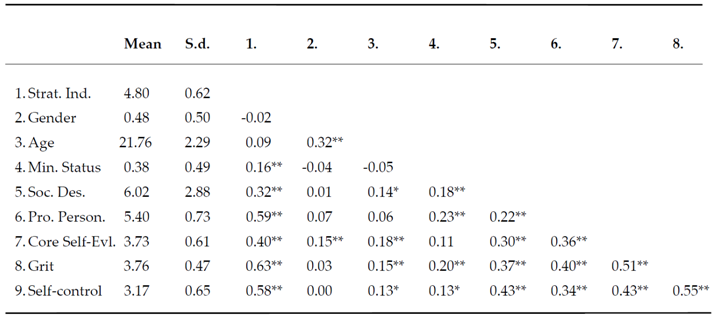

5.1. Correlations

5.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

5.3. Hierarchical Regression Analysis

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abuhassan, Abedrahman, and Timothy C. Bates. 2015. Distinguishing effortful persistence from conscientiousness. Journal of Individual Differences 36: 205–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett, Jeffrey Jensen. 2007. Suffering, selfish, slackers? Myths and reality about emerging adults. Journal of Youth Adolescence 36: 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrick, Murray R., and Michael K. Mount. 1991. The Big Five personality dimensions and job performance: A meta-analysis. Personnel Psychology 44: 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartnick, L. W., M. M. Kappelman, J. H. Berger, and Bernice Sigman. 1985. The value of the California Psychological Inventory in predicting medical-students career choice. Medical Education 19: 143–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bateman, Thomas S., and J. Michael Crant. 1993. The proactive component of organizational behavior: A measure and correlates. Journal of Organizational Behavior 14: 103–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binning, John F., and Gerald V. Barrett. 1989. Validity of personnel decisions: A conceptual analysis of the inferential and evidential bases. Journal of Applied Psychology 74: 478–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, Nicholas A., Patrick L. Hill, Nida Denson, and Ryan Bronkema. 2015. Keep on truckin’ or stay the course? Exploring grit dimensions as differential predictors of educational achievement, satisfaction, and intentions. Social Psychological and Personality Science 6: 639–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, Michael W., and Robert Cudeck. 1993. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In Testing Structural Equation Models. Edited by Kenneth A. Bollen and J. Scott Long. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Douglas J., Richard T. Cober, Kevin Kane, Paul E. Levy, and Jarrett Shalhoop. 2006. Proactive personality and the successful job search: A field investigation with college graduates. Journal of Applied Psychology 91: 717–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burnette, Jeni L., Ernest H. O’boyle, Eric M. VanEpps, Jeffrey M. Pollack, and Eli J. Finkel. 2013. Mindsets matter: A meta-analytic review of implicit theories and self-regulation. Psychological Bulletin 139: 655–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byrne, Zinta S., Brian K. Miller, and Virginia E. Pitts. 2010. Trait entitlement and perceived favorability of human resources management practices in the prediction of job satisfaction. Journal of Business Psychology 25: 451–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Chu-Hsiang, D. Lance Ferris, Russell E. Johnson, Christopher C. Rosen, and James A. Tan. 2012. Core self-evaluations: A review and evaluation of the literature. Journal of Management 38: 81–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronbach, Lee J., and Paul E. Meehl. 1955. Construct validity in psychological tests. Psychological Bulletin 52: 281–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Converse, Patrick D., Jaya Pathak, Anne Marie DePaul-Haddock, Tomer Gotlib, and Matthew Merbedone. 2012. Controlling your environment and yourself: Implications for career success. Journal of Vocational Behavior 80: 148–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, Paul T., and Robert R. McCrae. 1992. Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R) and NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI) Professional Manual. Odessa: Psychological Assessment Resources. [Google Scholar]

- Crisp, Gloria, and Irene Cruz. 2009. Mentoring college students: A critical review of the literature between 1990 and 2007. Research in Higher Education 50: 525–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duckworth, A. L. 2015. Research Statement, The Duckworth Lab. Available online: http://sites/sas/upenn.edu/duckworth (accessed on 31 March 2016).

- Duckworth, Angela Lee, and Kelly M. Allred. 2012. Temperament in the classroom. In Handbook of Temperament. Edited by Rebecca L. Shiner and Marcel Zentner. New York: Guilford Press, pp. 627–44. [Google Scholar]

- Duckworth, Angela, and James J. Gross. 2014. Self-control and grit: Related but separable determinants of success. Current Directions in Psychological Science 23: 319–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duckworth, Angela L., Christopher Peterson, Michael D. Matthews, and Dennis R. Kelly. 2007. Grit: Perseverance and passion for long-term goals. Personality Processes and Individual Differences 92: 1087–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eby, Lillian T., Tammy D. Allen, Sarah C. Evans, Thomas Ng, and David L. DuBois. 2008. Does mentoring matter? A multidisciplinary meta-analysis comparing mentored and non-mentored individuals. Journal of Vocational Behavior 72: 254–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fein, Erich C., and Howard J. Klein. 2011. Personality predictors of behavioral self-regulation: Linking behavioral self-regulation to five-factor model factors, facets, and a compound trait. International Journal of Selection and Assessment 19: 132–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, Sunny. 2013. Millennials’ Job Struggles: A Sign of Delayed Adulthood in the New Economic Reality. Huffington Post. May 21. Available online: http://www.huffingtonpost.ca/2013/05/21/millennials-job-struggles_n_3312042.html (accessed on 18 November 2018).

- Fuller, Bryan, and Laura E. Marler. 2009. Change driven by nature: A meta-analytic review of the proactive personality. Journal of Vocational Behavior 75: 329–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gough, Harrison G. 1985. A work orientation scale for the California Psychological Inventory. Journal of Applied Psychology 70: 505–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gough, Harrison G. 1995. Career Assessment and the California Psychological Inventory. Journal of Career Assessment 3: 101–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gough, Harrison G. 1996. CPI Manual: Third Edition. Pal Alto: Consulting Psychologists Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gough, Harrison G., and Kevin Lanning. 1986. Predicting grades in college from the California Psychological Inventory. Educational and Psychological Measurement 46: 205–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, Joseph F., William C. Black, Rolph E. Anderson, and Ronald L. Tatham. 1995. Multivariate Data Analysis, 4th ed. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, Nathan C. 2012. Life in transition: A motivational perspective. Canadian Psychology 53: 63–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckhausen, Jutta, Carsten Wrosch, and Richard Schulz. 2010. A Motivational Theory of Life-Span Development. Psychological Review 117: 32–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haynie, Jeffrey Joseph, C. Brian Flynn, and Shawn Mauldin. 2017. Proactive personality, core self-evaluations, and engagement: The role of negative emotions. Management Decision 55: 450–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, J. M. 2014. Where Have All the Grownups Gone? Why ‘Adulthood’ as We Know It Is Dead. Forbes. September 22. Available online: http://www.forbes.com (accessed on 18 November 2018).

- Hu, Li-tze, and Peter M. Bentler. 1999. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 6: 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, Baek-Kyoo, Huh-Jung Hahn, and Shari L. Peterson. 2015. Turnover intentions: The effects of core self-evaluations, proactive personality, perceived organizational support, developmental feedback, and job complexity. Human Resource Development International 18: 116–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jöreskog, Karl G., and Dag Sörbom. 2006. LISREL 8.80 for Windows [Computer Software]. Lincolnwood: Scientific Software International, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Judge, Timothy A., and Robert D. Bretz. 1994. Political influence behavior and career success. Journal of Management 20: 43–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, Timothy A., and Charlice Hurst. 2007. Capitalizing on one’s advantages: Role of core self-evaluations. Journal of Applied Psychology 92: 1212–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Judge, Timothy A., Amir Erez, Joyce E. Bono, and Carl J. Thoresen. 2003. The core self-evaluations scale: Development of a measure. Personnel Psychology 56: 303–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, Maureen E., David L. Blustein, Richard F. Haase, Janice Jackson, and Justin C. Perry. 2006. Setting the stage: Career development and the student engagement process. Journal of Counseling Psychology 53: 272–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirby, Eric G., Robert Konopaske, and Susan L. Kirby. 2016. The impact of strategic independence and mentoring on entrepreneurial orientation: Exploring the propensity of Millennials to transition into full adulthood. International Review of Entrepreneurship 14: 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, Paul. 2000. Handbook of Psychological Testing, 2nd ed. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kram, Kathy E., and Lynn A. Isabella. 1985. Mentoring alternatives: The role of peer relationships in career development. Academy of Management Journal 28: 110–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapan, Richard T. 2004. Career Development across the K–16 Years: Bridging the Present to Satisfying and Successful Futures. Alexandria: American Counseling Association. [Google Scholar]

- Long, James Scott. 1983. Covariance Structure Models: An Introduction to LISREL. Beverly Hills: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Lyons, Sean, and Lisa Kuron. 2014. Generational differences in the workplace: A review of the evidence and directions for future research. Journal of Organizational Behavior 35: 139–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinova, Sophia V., Henry Moon, and Dishan Kamdar. 2013. Getting ahead or getting along? The two-facet conceptualization of conscientiousness and leadership emergence. Organization Science 24: 1257–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNall, Laurel A., and Jesse S. Michel. 2011. A dispositional approach to work-school conflict and enrichment. Journal of Business Psychology 26: 397–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mechler, Heather, and Brian Bourke. 2011. Millennial college students and moral judgment: Current trends in moral development indices. Journal of Organizational Moral Psychology 2: 27–38. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, Brian K., and Robert Konopaske. 2014. Dispositional correlates of perceived work entitlement. Journal of Managerial Psychology 29: 808–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, Henry. 2001. The two faces of conscientiousness: Duty and achievement striving in escalation of commitment dilemmas. Journal of Applied Psychology 86: 533–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paulus, Delroy L. 1986. Self-deception and impression management in test responses. In Personality Assessment via Questionnaire. Edited by A. Angleitner and J. S. Wiggins. New York: Springler-Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, Philip M., Scott B. MacKenzie, and Nathan P. Podsakoff. 2012. Sources of method biases in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology 63: 539–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renn, Robert W., Robert Steinbauer, Robert Taylor, and Daniel Detwiler. 2014. School-to-work transition: Mentor career support and student career planning, job search intentions, and self-defeating job search behavior. Journal of Vocational Behavior 85: 422–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, William M. 1982. Development of reliable and valid short forms of the Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale. Journal of Clinical Psychology 38: 119–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seibert, Scott E., Maria L. Kraimer, and J. Michael Crant. 2001. What do proactive people do? A longitudinal model linking proactive personality and career success. Personnel Psychology 54: 845–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D. Brent, and Jill E. Ellingson. 2002. Substance versus style: A new look at social desirability in motivating contexts. Journal of Applied Psychology 87: 211–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stafford, Z. 2015. We Millennials lack a roadmap to adulthood. The Guardian. March 30. Available online: http://www.theguardian.com (accessed on 18 November 2018).

- Tangney, June P., Roy F. Baumeister, and Angie Luzio Boone. 2004. High self-control predicts good adjustment, less pathology, better grades, and interpersonal success. Journal of Personality 72: 271–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomason, Stephanie J., Michael Weeks, H. John Bernardin, and Jeffrey Kane. 2011. The differential focus of supervisors and peers in evaluations of managerial potential. International Journal of Selection and Assessment 19: 82–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tough, Paul. 2013. How Children Succeed: Grit, Curiosity, and the Hidden Power of Character. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. [Google Scholar]

- Twenge, Jean M., and Stacy M. Campbell. 2008. Generational differences in psychological traits and their impact on the workplace. Journal of Managerial Psychology 23: 862–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanberg, Connie R., and Joseph T. Banas. 2000. Predictors and outcomes of openness to changes in a reorganizing workplace. Journal of Applied Psychology 85: 132–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- West, Stephen G., John F. Finch, and Patrick J. Curran. 1995. Structural equation models with non-normal variables: Problems and remedies. In Structural Equation Modeling: Concepts, Issues, and Applications. Edited by Rick Hoyle. Thousand Oaks: Sage, pp. 56–75. [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler, Matthias, Maximilian Knogler, and Markus Bühner. 2009. Conscientiousness, achievement striving, and intelligence as performance predictors in a sample of German psychology students: Always a linear relationship? Learning and Individual Differences 19: 288–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Step 1 (Controls) | Step 2 (Independents) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | S.E. | β | B | S.E. | β | |

| Constant | 4.01 | 0.33 | 0.79 | 0.29 | ||

| Gender | −0.04 | 0.07 | −0.04 | −0.06 | 0.05 | −0.05 |

| Age | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| Minority status | 0.14 | 0.07 | 0.11 * | −0.04 | 0.05 | −0.03 |

| Socially desirable responses | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.30 ** | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Proactive personality | 0.32 | 0.04 | 0.38 ** | |||

| Core self-evaluation | −0.03 | 0.05 | −0.03 | |||

| Grit | 0.47 | 0.07 | 0.35 ** | |||

| Self-control | 0.27 | 0.04 | 0.28 ** | |||

| F-score (df1, df2) | 10.42 (4, 306) ** | 88.46 (8, 302) ** | ||||

| Δ F-score | 10.42 ** | 78.04 ** | ||||

| R2 | 0.12 | 0.60 | ||||

| Δ R2 | 0.12 | 0.48 | ||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.11 | 0.58 | ||||

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Konopaske, R.; Kirby, E.G.; Kirby, S.L. Positive Disposition in the Prediction of Strategic Independence among Millennials. Adm. Sci. 2017, 7, 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci7040038

Konopaske R, Kirby EG, Kirby SL. Positive Disposition in the Prediction of Strategic Independence among Millennials. Administrative Sciences. 2017; 7(4):38. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci7040038

Chicago/Turabian StyleKonopaske, Robert, Eric G. Kirby, and Susan L. Kirby. 2017. "Positive Disposition in the Prediction of Strategic Independence among Millennials" Administrative Sciences 7, no. 4: 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci7040038

APA StyleKonopaske, R., Kirby, E. G., & Kirby, S. L. (2017). Positive Disposition in the Prediction of Strategic Independence among Millennials. Administrative Sciences, 7(4), 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci7040038