Abstract

Albert and Whetten defined organizational identity (OI) as the central, distinctive and enduring characteristics of an organization. Scholars found OI to be a difficult construct to apply to organizations and, over time, they defined it from functionalist, social constructionist, postmodernist and psychodynamic perspectives. All of these perspectives made great theoretical contributions to the field, but they were largely unable to integrate practice and theory in a way that could benefit organizations. Hatch and Schultz’s work is exceptional in this regard: they provided a theory that has the promise of practical implications for organizations in regard to organizational continuity. They perceived organizational continuity as existing in the balanced/responsible behavior of an organization’s members, among themselves and with key external stakeholders. They provided an effective model in this regard, but they overlooked how individuals’ political interests overshadow balanced behavior. Politics that arise as a result of individuals’ identity are generally considered to be psychological in origin and link OI to organizational learning (OL) as a co-evolving process. The present research hence operationalizes Hatch and Schultz’s model by reference to a Winnicottian framework to understand how OI is socially constructed and psychologically understood in the political interests of the management and employees, among themselves and with key external stakeholders. In doing so it explores the political implications of OI for OL, as perceived in an organization’s continuity. The context of the research is the Pakistani police.

1. Introduction

Albert and Whetten (1985) defined organizational identity (OI) as the central, distinctive and enduring characteristics of an organization. Scholars were fascinated by the construct but found it too complex to apply to organizations. In order to cut through this complexity, over time OI was defined from functionalist, social constructionist, postmodernist and psychodynamic perspectives (He and Brown 2013). All of these perspectives made great theoretical contributions to the field, but practical application was largely missing. That does not mean that practical work has not been done in the field, but, as compared to the theoretical contribution, it is sparse. Moreover, there also seems to be a lack of integration between theory and practice. In other words, the theoretical side has largely worked independent of the practice side, and vice versa. In this sense, there are very few theories that inform the practice side in ways that are beneficial for actual organizations. However, Hatch and Schultz’s (2002) work is an exception in this regard: they provided a theory with a great promise of practical implications for organizations, in regard to continuity and progress.

Hatch and Schultz (2002) defined OI by reference to Mead’s social constructionist framework, which refers to “…the internal–external dialectic of identification as the process whereby all identities—individual and collective—are constituted” (Hatch and Schultz 2002, pp. 993–94, quoting Jenkins 1996, p. 20, emphasis in original). They perceived a deeper understanding of OI through a Freudian perspective. From a psychodynamic perspective, they argued that an organization’s excessive internal focus or excessive external focus could lead to organizational dysfunctions, and hence lead to the organization’s failure. They showed that an organization’s health (as manifested in its continuity and progress) depends on the balanced behavior of its members, both among themselves and also with external stakeholders. This balanced behavior is implicit in an organization’s members’ sense of responsibility toward each other and toward external stakeholders.

Hatch and Schultz (2002) provided an impressive model; however, the present research argues that their model has two issues that need addressing, as follows: (1) They framed their model in a Mead-ian and Freudian perspective, and found it difficult to operationalize. The present research understands that the operationalization issue could be addressed through the relational paradigm of psychodynamics. (2) They did not bring into the equation the fact that responsible behavior is intrinsically linked to individuals’ political interests, which result from unequal power relations both within and outside the organization. The present research observes that this issue of political understanding in Hatch and Schultz’s (2002) model can be addressed by reference to certain strands of organizational learning (OL) scholarship.

In OL scholarship it has always been a popular belief among scholars that “…learning inside the organization must be equal to or greater than change outside the organization or the organization will not survive” (Schwandt and Marquardt 2000, p. 3). OL scholarship has made a tremendous contribution to both theory and practice. However, OL scholarship, by and large, does not link management and employees in a relationship of interdependence (e.g., Stacey 2003); and it finds politics and emotions to be persistent problems for OL. Nevertheless, noteworthy exceptions to this rule can be seen in the work of Argyris and Schön (1974, 1978) and Vince (2001, 2002).

Argyris and Schön contributed to the rational tradition of OL. Argyris (1992) argued that an organization’s management and employees, while working in a relationship of interdependence, are linked in a dilemma of “autonomy versus control” whereby both play politics and shape a way of working that is comfortable for both and that is also progressive, i.e., it leads to organization’s continuity. However, over time, this way of working reflects “organizational defensive routines” that are followed by all, unreflectively. In this sense, Argyris and Schön (1978) implicitly linked OL to the theory of institutionalization (Berger and Luckmann 1966) or structuration (Giddens 1984), whereby individuals shape a structure and are in turn shaped by it. Argyris and Schön did acknowledge the deeper roots of politics, which reside in human psychology. However, they tried to find a solution to organizational defensive routines in individuals’ cognitive potential and, therefore, found it difficult to resolve the issue of psychological politics within organizations. Scholars suggest that any solution to emotions need to be understood in psychodynamics (e.g., Diamond 1986; Antonacoupolou and Gabriel 2001).

In regard to psychodynamics, Vince (2001, 2002) argued that management and employees are linked in an unequal power relationship in relatedness, and that this makes OL a political process. Management and employees mitigate politics by forming an “internal establishment” (Hoggett 1992) that creates familiarity and ensures both management and employees work together to achieve the organizational goals. However, this internal establishment also reflects a way of working that, over time, becomes institutionalized in organizational systems, policies, strategy and so on. In this sense, Vince also implicitly perceived the formation of “internal establishment” as involving agency and structure dialectics, whereby individuals form a social structure and are in turn formed by it. Thus, “organizational defensive routines” and “internal establishment” represent one and the same thing: both are political structures and both reflect the deeper roots of politics, which lie in human psychology.

Dialectics, in the psychological understanding, links management and employees in a ‘dilemma of mutual recognition’ (Benjamin 1990). Mutual recognition, in Hegelian dialectics (Hegel 1807), depicts two essential but conflicting positions: management wants to work according to their own logic and employees want to work according to their own logic. This instigates a psychological politics between the two: ‘I refuse to recognize you unless you recognize me’ (Benjamin 1988, p. 38).

The politics that is played out between these two actors is not aimed at defeating the other but at “…maintaining a state of continuous difference and provocation” (Cooper and Burrell 1988, p. 99): i.e., “…if we fully negate the other, that is, if we assume complete control over him and destroy his identity and will, then we have negated ourselves as well. For then there is no one there to recognize us, no one there for us to desire” (Benjamin 1988, p. 39). Within organizations, management and employees mitigate psychological politics by shaping a way of working that is comfortable and progressive. Over time, this way of working becomes the commonsense reality. In OL scholarship, Argyris and Schön identified this commonsense reality as “organizational defensive routines”, and Vince identified it as an “internal establishment”. Since politics arises from the distinctive identities of the management and the employees, in the dialectical interplay it seems that “organizational defensive routines” or the “internal establishment” reflect OI: that is, it is “the way we do things here”.

The above discussion shows that scholarship in the field of both OL and OI appreciates that, in a psychological sense, OI is constructed in a dialectical tension. OI scholarship frames dialectics in the responsible/balanced behavior of individuals that lead to organization’s progress and continuity. OL scholarship frames dialectics in the political behavior of individuals that stand in the way of an organization’s progress and continuity. From a psychological perspective, it seems that political and responsible behavior, which are the dialectical outcomes of unequal relationship, reflect two sides of the same coin. This shows that OL and OI are intrinsically linked and could benefit from being viewed through the relational paradigm of psychodynamics.

The relational paradigm ‘departs from instinctual models of motivation to relational model; where importance is placed on the role of personal agency, conscious motives, relational experience, and social involvement in conceptions of personality development’ (Borden 2000, p. 356). There is no dearth of scholars who have made valuable contributions to our understanding of the relational paradigm of psychodynamics. One such scholar is Winnicott. Since OL and OI are intrinsically linked the present research uses the Winnicottian model, as Winnicott also sees individual identity as being intrinsically linked with the individual potential of learning. Moreover, Winnicott perceives the process of individual identity construction as involving Hegelian dialectic, and his work in dialectical framing has a social application. Lastly, Winnicott sees responsible/balanced behavior as taking place in a “holding environment” of trust and understanding. The present research, hence, seeks to operationalize Hatch and Schultz’s (2002) model through applying a Winnicottian understanding, by seeing how OI is socially constructed and psychologically understood through the political interests of the management and employees, among themselves and with key external stakeholders. In doing so it explores the political implications of OI for OL, as perceived in an organization’s continuity and progress. The following sections discuss OL, OI, power scholarship, the Winnicott model and the conceptual framework. This is followed by a discussion of the context of the Pakistani police, the research methodology, an analysis of the data, discussion, and an assessment of the contributions and the limitations of the research.

2. Literature Review

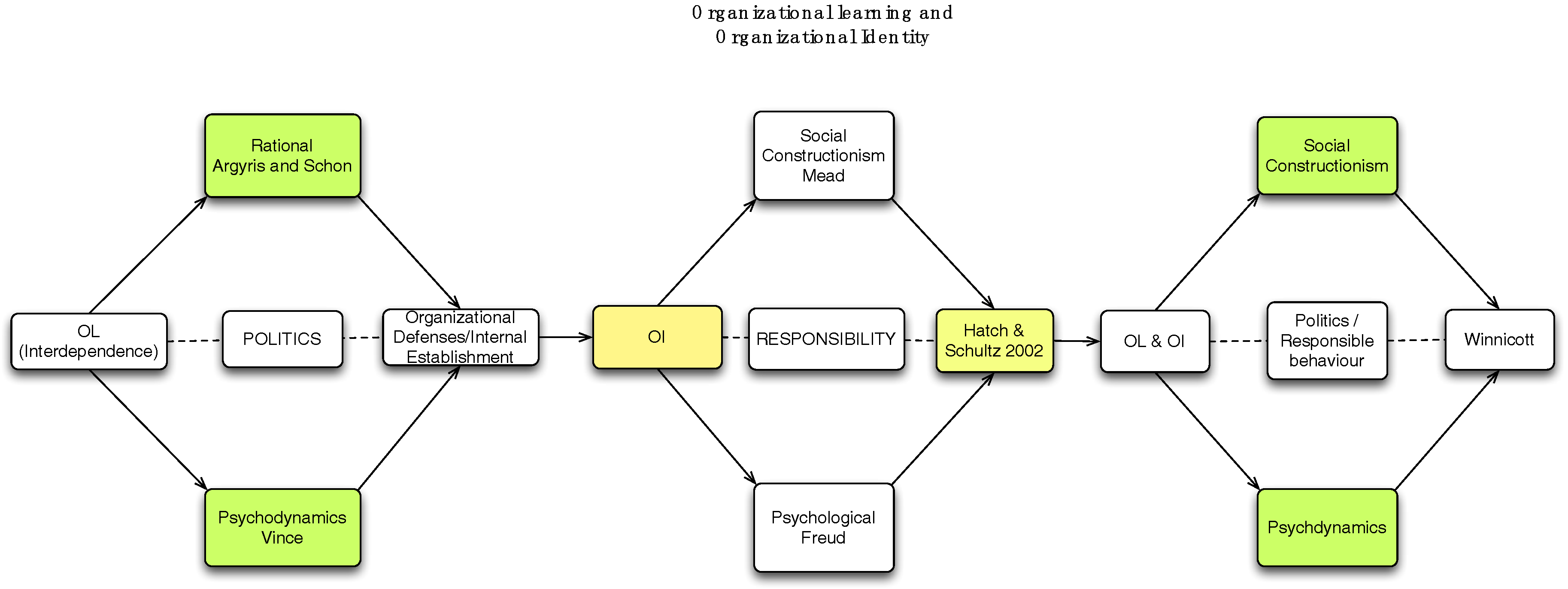

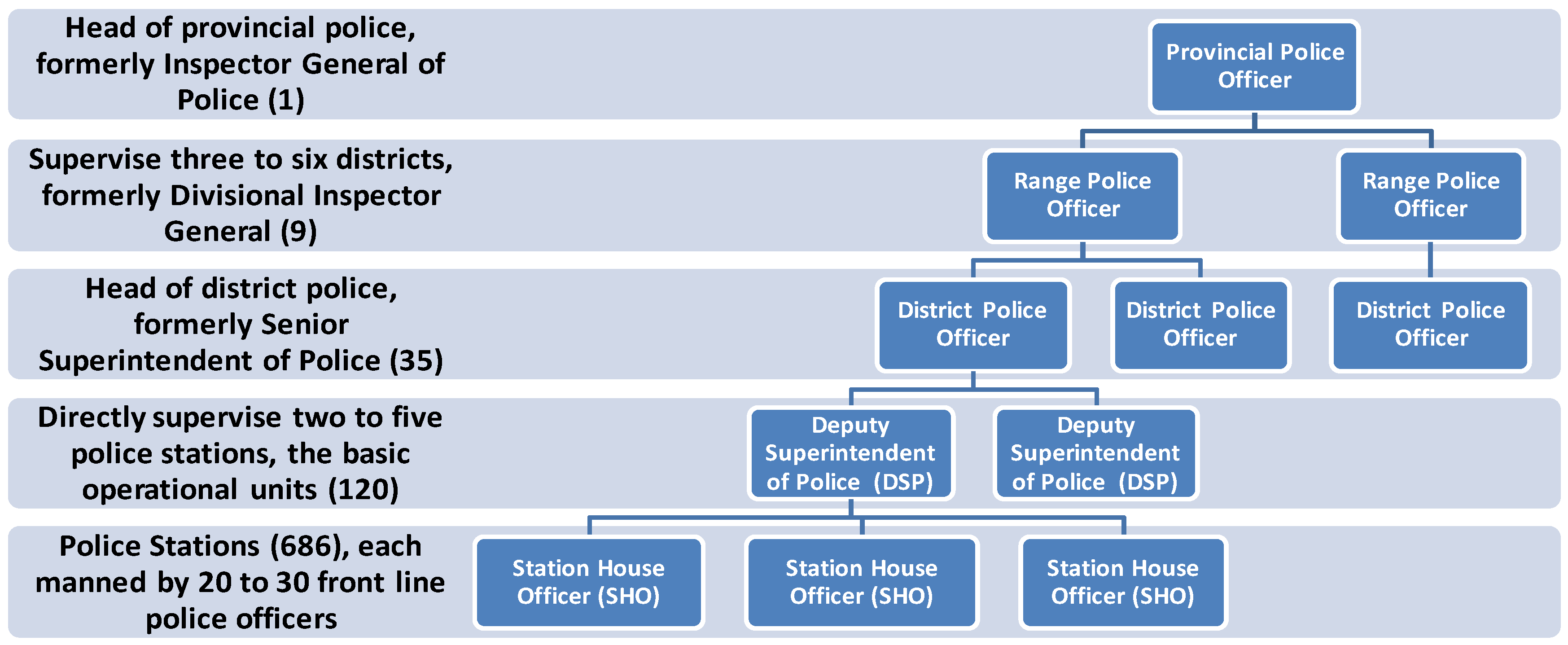

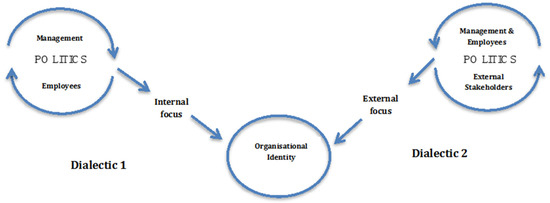

The present research takes a broad view of OL and OI scholarship. Both these broad views converge to two most important understandings of organizational behavior, as seen through the lens of identity: politics and responsibility. It is these two constructs (politics and responsibility) that link the scholarships of OL and OI to Winnicottian perspective. However, in a dialectical relationship the key to operationalizing OL and OI is power. The paper now discusses OL and OI scholarships, followed by a section on power. It then introduces the Winnicott model, along with the conceptual framework of the present paper. The roadmap of literature review is shown in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1.

Roadmap of Literature Review.

2.1. OL

The idea of OL was introduced in organizational studies scholarship in the early 1960s, with a focus on how to steer an organization toward progress and development by keeping it aligned to constantly changing requirements over time (e.g., Schwandt and Marquardt 2000; Butcher and Clarke 2002). The biggest dilemma that scholars in this field have faced from the outset has been the politics that arises between the management and employees while working in a relationship of interdependence.“In spite of its popularity and consolidation, the OL debate has not progressed much beyond conceptualization of learning as an integral part of organizing” (Antonacoupolou and Chiva 2007, p. 277). OL is seen to be divided into two main traditions: rational and psychodynamics (Vince 2001, 2002; Brown and Starkey 2000; Antonacoupolou and Gabriel 2001). The rational tradition is the dominant framework of OL and focuses on technical and social perspectives (Easterby-Smith and Araujo 1999). These perspectives have also been termed cognitive and social (Cook and Yanow 1993), functional and interpretive (Huysman 1999) and structural and cultural (Moynihan and Landuyt 2009). The psychodynamic tradition’s focus is on unconscious emotions.

The technical perspective perceives OL as existing in individuals’ cognitive potential, and in the most commonsense understanding defines it as “the process of improving actions through better knowledge and understanding” (Fiol and Lyles 1985, p. 803). This perspective considers OL to be deterministic and top-down, facilitated only through the formal role of management, and hence finds politics to be a persistent problem. The social perspective, on the other hand, considers OL to be informal and bottom-up, emphasizing the central role of employees. In the social perspective, OL can be observed in a culture: it represents “a pattern of shared basic assumptions that the group learned as it solved its problems of external adaptation and internal integration, and which has worked well enough to be taught to new members as the correct way to perceive, think and feel in relation to these problems” (Schein 1992, p. 12).

The social perspective considers politics to be an inherent part of social life (Easterby-Smith and Araujo 1999): according to this perspective, within a culture there is no identity and power differential, and the politics between colleagues is constructive. In this sense, the cultural lens overlooks politics, at the interplay of management and employees. Therefore, when the underlying assumptions of a culture are challenged, the politics—hidden in the ‘existing order of things’ (Foucault 1977)—between management and employees comes to the forefront. Thus, the social perspective also finds politics at the interface of management and employees to be a consistent problem.

The psychodynamic tradition’s focus is the unconscious emotions that are linked to individuals’ well-being. A key insight from this perspective is that OL challenges individuals’ and organizational identities/self-concepts, which results in anxiety (Brown and Starkey 2000). To overcome anxiety, individuals and organizations deploy social defenses to preserve their existing self-concepts/identity (e.g., Jaques 1955; Menzies Lyth 1959; Bain 1998; Brown and Starkey 2000). Brown and Starkey (2000) were the first to recognize the explicit link between OL and OI, and suggested that ‘critical reflection’ and ‘wise dialogue’ could overcome social defenses. However, Brown and Starkey (2000) did not see the origins of social defenses as lying in the immediate social context, and they overlooked the point that this social context instigates politics between management and employees, and that this makes OI inherently political. It is in this sense that OI acts as a constant barrier to OL. In short, OL scholarship, in both the rational and psychodynamic traditions, by and large takes management and employees as a mutually exclusive pair, not linked in a relationship of interdependence (e.g., Huysman 1999; Stacey 2003), and finds politics to be a persistent problem. However, an exception to this rule can be found in the work of Argyris and Schön, and Vince.

2.1.1. Argyris and Schön

Argyris (e.g., 1973, 1992), very early on, identified that management and employees, while working in a relationship of interdependence, are linked in an age-old dilemma of “autonomy versus control”. In this dilemma, management wants to work in their own espoused way and employees want to work in theirs. This tension reflects a dilemma of mutual recognition between the two. Mutual recognition, in Hegelian dialectics, instigates a psychological politics (I refuse to recognize you unless you recognize me), i.e., a “formal authority requires a willingness on the part of the participants to accept the influence of the authority” (Argyris 1973, p. 255, quoting Simon 1957).

To mitigate the potential danger of these psychological politics, both management and employees unknowingly establish a way of working that is comfortable for both, and that is also progressive and leads to continuity. Over time, this way of working exercises a control over both management and employees, through its familiarity and “recursivity” (Giddens 1984). Argyris (1986) called this regressive way of working “organizational defensive routines”. In this sense, OL appears to be linked to the process of institutionalization or structuration, whereby “organizational defensive routine” become the everyday reality of the organization: newcomers also follow these routines unreflectively. These routines hence reflect an inertia, which lowers the potential of OL (Easterby-Smith and Araujo 1999).

Argyris (1992, pp. xiii–xiv) states: “An organizational defense is a policy, practice, or action that prevents the participants (at any level of any organization) from experiencing embarrassment or threat, and at the same time, prevents them from discovering the causes of the embarrassment or threat. Organizational defenses (which include groups, intergroups, and interpersonal relationships) are therefore anti—learning and overprotective.” In this sense Argyris perceives defenses to be psychological in origin. Argyris and Schön (1978) postulated theories and models to help individuals overcome “organizational defensive routines” through the use of individuals’ cognitive abilities. However, they came to realize that overcoming organizational defensive routines is not as easy as they had at first thought. Diamond (1986) argues that both of these scholars tried to find an answer to these defenses in the cognitive potential of individuals, but that any answer to the psychological/emotional regression needs to be found in a psychodynamics paradigm.

2.1.2. Vince

Vince (2001, 2002), researching in psychodynamics, observed that a relationship of interdependence exists between an organization’s management and employees, in a relatedness, which “implies a range of emotional levels of connection across the boundaries of person, role and organization, which emphasize the relational nature of organizing” (Vince 2001, pp. 1332–33). This relatedness, which exists within the context of power inequality, links management and employees in a paradoxical tension, where both groups (management and employees) want to work according to their own logic. However, due to the power inequality, management and employees are linked in a dilemma of mutual recognition that gives rise to psychological politics (I refuse to recognize you unless you recognize me). Vince implicitly perceives this dilemma of mutual recognition as coming about because individuals are “creatures of each other” (Hinshelwood 1998), and sees that this involves “…a mutual process of becoming that obscures the notion of a separate self” (Vince 2001, p. 1332).

By this, Vince means that management and employees shape a social reality (organization), such that “…organizations are in a continuous process of becoming, rather than a stable state” (Vince 2002, pp. 1191–92). In this sense, Vince implicitly captures the Hegelian dialectics whereby management and employees are two essential parts of an organization, i.e., without management or without the employees the organization would not exist. However, the relationship between the two is also essentially conflicting: psychological politics is played out throughout the organization. The management and employees unknowingly mitigate the psychological politics by forming a way of working that reflects the “internal establishment” (Hoggett 1992). The internal establishment hence creates familiarity and ensures that both management and employees work together to achieve the organizational goals. However, it also reflects a way of working that, over time, becomes institutionalized in organizational systems, policies, strategy and so on.

Vince’s work, in this way, also implicitly perceives OL as involving agency and structure dialectics, as seen in the process of institutionalization/structuration (e.g., Berger and Luckmann 1966; Giddens 1984). Vince hence argues that OL can be seen “as both a progressive and a regressive idea. Indeed, the tension between these two possibilities constitutes a critical perspective on organizational learning and thereby helps to sustain the value of the concept” (Vince 2001, p. 1330 quoting Vince and Broussine 1996). Vince (2001) perceives this progressive and regressive potential of OL in Bion’s theorization of a container–contained relationship that “provides the basis for a dialectic of knowledge” (Bion 1962; Hoggett 1992, p. 67). Since Vince identifies relatedness in the unequal power relationship between management and employees, he therefore sees politics in this process of institutionalization as being hidden in the ‘existing order of things’ in Foucauldian understanding. Vince, however, identifies the roots of politics as lying in the psychological well-being of individuals (i.e., management and employees).

Internal establishment, in this sense, parallels Argyris and Schön’s understanding of “organizational defensive routines”. Thus, both “organizational defensive routines” and “internal establishment” are cauldrons of politics and emotions, reflecting inertia—and this inertia results in barriers to OL. However, in the rational tradition, Argyris and Schön focus on the cognitive side of learning and believe OL takes place either as a defense or in pursuit of espoused meanings. However, Vince perceives that there is interplay between the conscious (espoused) and unconscious (defenses) motivations, whereby any solution to defenses could be sorted in human emotions: after all it is the emotions that act political (2001). Moreover, Argyris and Schön focus on internal politics that is played out between the management and employees, and overlook the similar politics that are played out between them and key external stakeholders. Vince, however, sees politics both internally and externally, in the larger social domain.

The present research argues that Argyris and Schön’s, and Vince’s, work, when looked at through the lens of identity, shows that they implicitly link OL to OI (specifically to OI’s organizational defensive routines/internal establishment). However, Argyris and Schön’s exclusive focus on cognition meant they put identity and emotions in the background. At the same time, Vince’s exclusive focus on emotion and cognition meant that he too put identity in the background. However, through their psychological underpinning, OL and OI are intrinsically intertwined, and thus this research argues that both could benefit from an understanding of the process by which OI is constructed.

2.2. OI

Albert and Whetten (1985) defined OI as existing in the central, distinctive and enduring characteristics of an organization. They understood this centrality as residing in the organization’s core attributes and distinctiveness in relation to the organization’s competitors: “organizations maintain identity through interaction with other organizations by a process of interorganizational comparison over time” (Gioia 1998, p. 21). Finally, they understood these enduring characteristics as residing in the organization’s continuity over time (Corley et al. 2006). Scholars working in the field of OI found OI a difficult concept to apply to organizations. This resulted in many debates within OI scholarship and, over time, OI was defined from functional, social constructionist, postmodernist and psychodynamic perspectives (He and Brown 2013).

The functional perspective perceives OI as the “essence” of the organization, which all members of the organization have to follow blindly. “Certainly, we can observe that organizational leaders frequently invoke a collective identity as a means of imputing or maintaining the sense of organizational coherence and cooperativeness” (Gioia 1998, pp. 20, 21). In practice, OI is not followed blindly—rather, OI depends on the meanings assigned to it by members of an organization. This has led scholars to understand OI from a social constructionist perspective that relates to the cognitive abilities of an organization’s members in regard to understanding “who we are” as an organization (Corley et al. 2006; He and Brown 2013). However, organizations do not operate in a vacuum and their behavior has a bearing on a society. In this sense, organizational members also understand OI as referring to “how others see us” (Corley et al. 2006). The social construction perspective thus bifurcates OI into two focuses: internal, seen in an organization’s culture, and external, seen in the organizational image. This resulted in many debates among scholars as regards understanding whether OI, culture and image are the same thing, or whether they are different from one another? (ibid.) However, the main issue in the social constructionist framework is how to gauge the politics that take place at the interface of management and employees, where there is an unequal power distribution. This takes us to the postmodernist perspective of OI.

The postmodernist perspective argues that an organization can be viewed as a form of Bentham’s panopticon, where individuals are made to work in a way that is contrary to their desires, beliefs or regimes of truth (Brown 2001). In this sense, scholars have considered OI to be a discursive and linguistic construct, underpinned by various political interests. “In the postmodern view, organization is less the expression of planned thought and calculative action and a more defensive reaction to forces intrinsic to the social body which constantly threaten the stability of organized life” (Cooper and Burrell 1988, p. 91, emphasis added). This moves the focus to psychodynamics. Psychodynamics show how unconscious emotions act as individuals’ defense mechanisms and can be writ large at a collective level (e.g., Jaques 1955; Menzies Lyth 1959). Diamond (1993) analyzed OI as a defensive structure as it poses a threat to individuals’ identity. Brown and Starkey (2000) looked at OI as adjusting collective self-esteem, which has negative implications for OL. However, OI is a relational construct and the psychodynamic perspective, both in OI and OL scholarship, is based on a Freudian logic: it thus overlooks the political dimension of defenses, as seen in an immediate social context.

The above discussion shows that all of the perspectives that have been brought to bear on OI have made a valuable theoretical contribution to the field but they have largely overlooked the practical side: the theoretical and practice sides have worked independently of each other. In other words, there are very few theories that align with the practical side to show the combined benefit to an organization of the theory and the practice. Hatch and Schultz’s (2002) work is exceptional in this regard, as explained below.

Hatch and Schultz (2002)

Hatch and Schultz (2002) conceptualized OI as reflecting a dialectical interplay between organizational members and key external stakeholders. They perceived OI as existing in a social context, drawing on Mead’s framework (Mead 1934). In Mead’s perspective, individual identity consists of “I” and “me”: both are in a constant interplay. That is, “me” is how society sees the person and “I” is how the person wants to behave in relation to the expectations of society: i.e., “The ‘I’ is the response of the organism to the attitudes of the others; the ‘me’ is the organized set of attitudes of others which one himself assumes. The attitudes of the others constitute the organized ‘me’, and then one reacts toward that as an ‘I’” (Mead 1934, p. 175). Following Mead’s conceptualization, Hatch and Schultz (2002) perceived that the members of an organization shape the internal focus—”I” (“who am I?”)—reflecting the organization’s culture. Moreover, the way members of the organization interact with key external stakeholders shapes an organization’s external focus—”me” (how others see us)—reflecting the organizational image. They showed that “organizational culture” and “organizational image” both constitute OI and are linked in a constant dialectical interplay.

Hatch and Schultz (2002) highlighted the practical application of OI, in a psychological sense, as was originally advocated by Albert and Whetten (1985): organizations need to create a balance between their internal focus (management and employees) and their external focus (key external stakeholders). “The greater the discrepancy between the ways an organization views itself and the way outsiders view it…, the more the ‘health’ of the organization will be impaired (i.e., lowered effectiveness)” (Albert and Whetten 1985, p. 269).

In this sense, Hatch and Schultz (2002) argued that if organizations focus only internally and ignore external stakeholders they indulge in narcissism. Similarly, if organizations are tilted toward external stakeholders and ignore internal stakeholders they indulge in hyper-adaptation. Both narcissism and hyper-adaptation represent organizational dysfunctions that, if not corrected, could lead to organizational failure. Hatch and Schultz (2002) provided an effective model but they overlooked how responsibility is intrinsically intertwined with individuals’ political interests, which exist in unequal power structures. Hatch and Schultz (2002) concede “…although we cannot explicitly model the effects of power due to their variety and complexity, we mark the existence of these influences for those who want to apply our work” (Hatch and Schultz 2002, p. 1005).

Moreover, by framing their model in a Mead-ian and Freudian perspective they found it difficult to operationalize it. The present research maintains that in this dialectical interplay, power is key to operationalizing OI.

2.3. Understanding Power

Power is a complex phenomenon, and is difficult to explain (Haugaard 2002). However, two main strands of power have been discussed in relation to organizations: episodic and systemic (Lawrence et al. 2005). Episodic power is coercive and manipulative, and systemic power is dominating and normative (Fleming and Spicer 2014). Episodic and systemic power can also be seen through Lukes’s (1974) four-dimensional view of power. The first of these four dimensions of power is coercive. This is seen in decision-making agendas, where there are overtones of patronizing: as, for example, parents’ control over children. In decision-making agendas, “[t]he base of an actor’s power consists of all the resources—opportunities, acts, objects, etc.—that he can exploit in order to affect the behaviour of another” (Dahl 1957, p. 203).

The second dimension of power focuses on structural inequalities and takes the form of manipulation (Fleming and Spicer 2014). Within an organization, the second dimension of power brings to the center the management’s interests, in the way they take a preferred position to promote and defend their vested interests. This power attempts to ensure that action and discussions occur within accepted boundaries (Fleming and Spicer 2014). A systemic perspective is seen embedded in a social structure whereby it is used to control the thought processes of the subjects and can be seen as both dominating (third dimension) and normative (fourth dimension). The systemic perspective in a third-dimensional view within an organization reflects the dominant ideology of the management, in the ways the management shape the souls and minds of the employees (Fleming and Spicer 2014). In contrast, the fourth dimension of power is normative power, which is seen in a Foucauldian perspective (ibid.). It is Foucauldian power that is most relevant to the conceptualization of power and politics in the identity construction process. This is discussed in the next paragraphs.

Foucauldian Power and Identity Framework

According to Foucault, through power–knowledge discourses individuals shape a social structure in varied discursive and non-discursive practices. Over time, these practices become institutionalized in the system, processes and policies, such that structures act as the instruments of power. Structure, in this sense, acts as Bentham’s panopticon: it shapes individuals’ identity in their regimes of truth through mechanisms of governmentalization and discipline (Digeser 1992). The governmentalization has a totalizing effect: a homogenized society is generated that works for common goals, for the betterment of the society (ibid.). However, there are always rebels and these are brought back to the “normal” state through the disciplining mechanism of a panopticon gaze (e.g., Faubion and Rabinow 1994). Disciplining thus has an individualizing effect (Digeser 1992). The governmentalization and disciplining nature of the structure provides a code of behavior that individuals unknowingly internalize. It is this code of behavior that shapes individuals’ identities in their regimes of truth. These regimes, in turn, act as an “inner panopticon” (Jackson et al. 2006) that is used to ensure self-discipline on the part of the individuals. Foucault, hence, centralizes the individual as an active agent, who can think, feel and decide for him/herself, independent of any pressure or coercion.

Thus, power can only be exercised on a free subject, i.e., a subject who is “thoroughly recognized and maintained... as a person who acts” (Foucault 1982, p. 220). Foucault perceives that individuals’ regimes of truth become the basis of political struggles. Politics occurs when inequality is felt in relation to human suffering and human beings’ existentialist desires (Newton 1998): i.e., individuals have a need for independent existence—to be free and responsible for their own development. Existentialism links individuals in the dilemma of ‘mutual recognition’ or what Foucault appreciates as the ‘paradox of difference’: “Difference is thus a unity which is at the same time divided from itself, and, since it is that which actually constitutes human discourse…,it is intrinsic to all social forms” (Cooper and Burrell 1988, p. 98). In this sense, inequality, as underpinned in existentialism, brings to the surface deep emotions, which become the basis of political struggles and also of transformation: in other words, “the inventions of new forms is shown to be shaped by and dependent on old meanings, and the interplay of resistance and determination produces practices and understandings that are simultaneously [representative] of an existing order and a re-imagining of it” (Mahoney and Yngvesson 1992, p. 63). Scholars who have this understanding identify psychological overtones in Foucault’s conceptualization of power and politics, which arise from individuals’ identities in their regimes of truth (e.g., Newton 1998; Mahoney and Yngvesson 1992).

According to Clegg et al. (2006), the Foucauldian understanding of power in identity dynamics encompasses all the other dimensions of power. “To argue that identity and interests are related within the framework of a dimensional view, and that the identity shaping mechanisms are a fourth dimension, can only mean that this fourth dimension somehow shapes the identities of the other dimensions” (Clegg et al. 2006, p. 218). Clegg et al. (2006) hence argue that Foucault’s power, as perceived in the fourth dimension, is analytically underdeveloped (e.g., Garratt 2013). In regard to OL scholarship, Vince (2001) sees power in a Foucauldian perspective, and argues that it is the emotions that act politically. The present research also takes the view that Foucault’s work is underdeveloped in its psychological understanding. It argues that Foucault’s work finds its parallel, in terms of psychological understanding, in Winnicott’s perception of power and identity. This is discussed below.

2.4. Winnicott’s Model

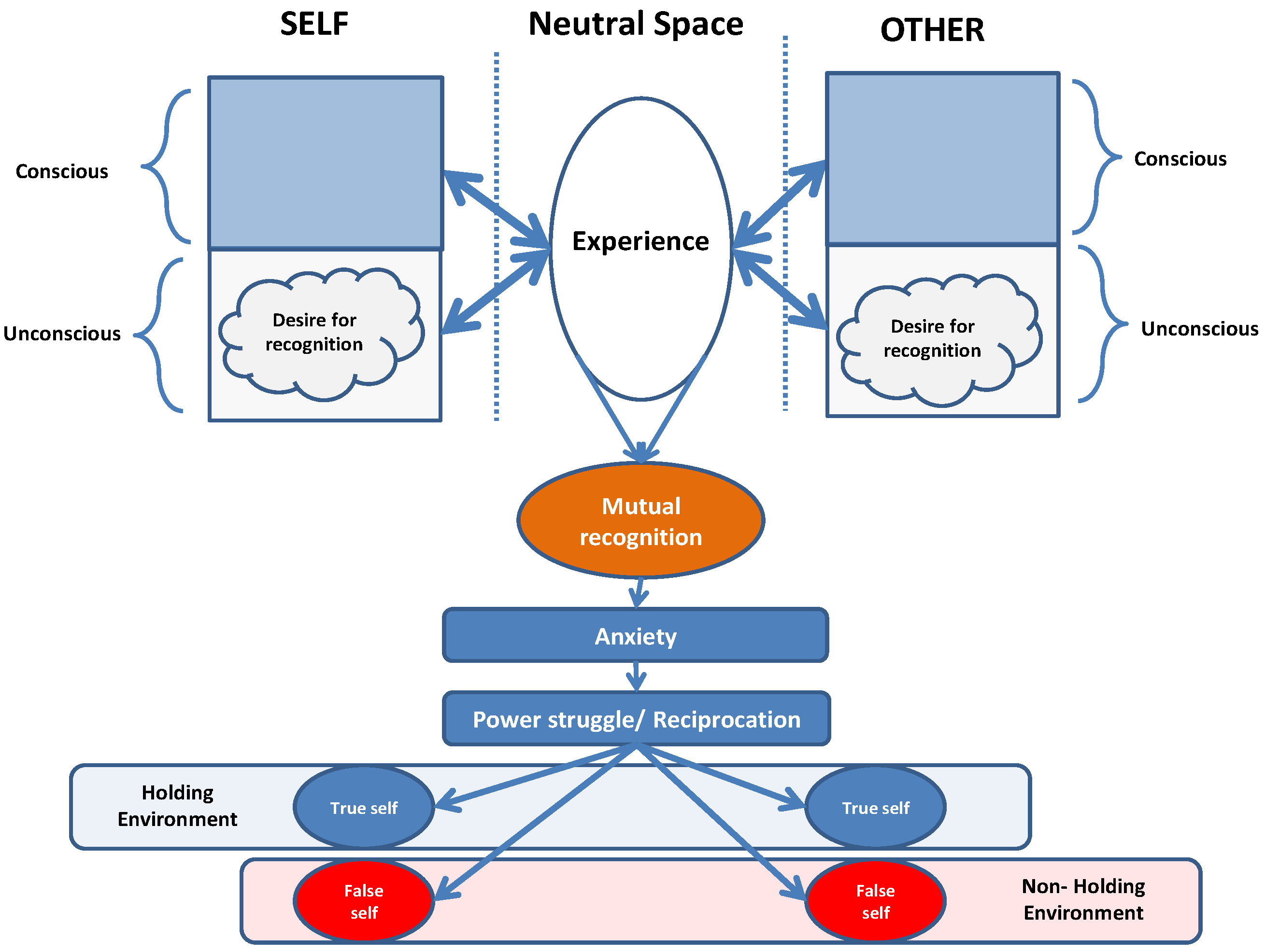

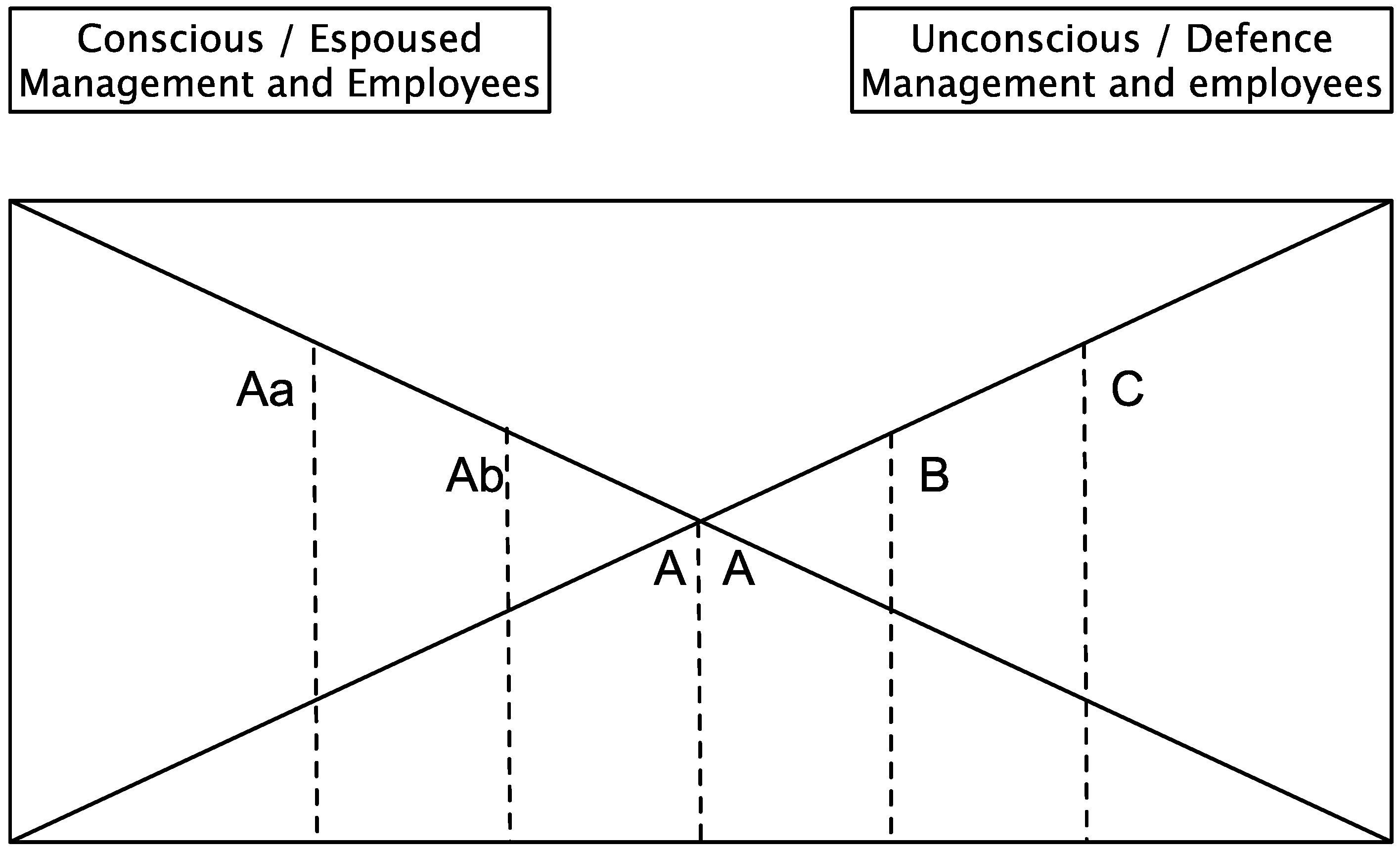

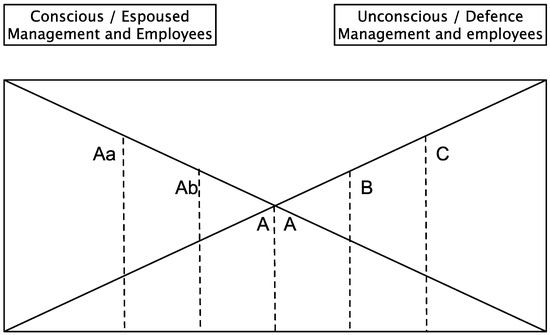

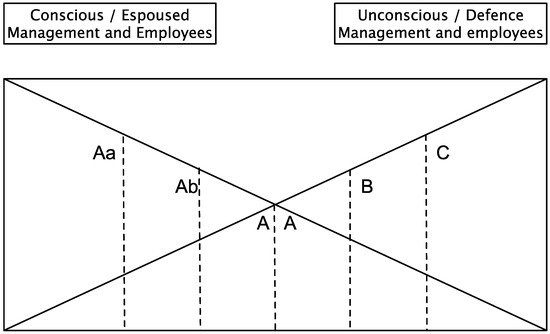

According to Winnicott (1971), identity is the product of an inner reality (self) that is understood as existing in an intra-psychic space where there is an interplay of conscious and unconscious. The outer reality (other) is understood as involving the interplay between the “self” and “other”, while experience is deciphered in the inter-psychic (relational) space. The experience “… is an area that is not challenged, because no claim is made on its behalf except that it shall exist as a resting-place for the individual engaged in the perpetual human task of keeping inner and outer reality separate yet interrelated” (Winnicott 1971, p. 3). This means the self is independent of the other, but this independence is only realized through dependence on the other. Thus, identity construction depends on the quality of the experience that takes place between the “self” and the “other”, as shown in the schematic diagram below (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Winnicott’s Model.

Winnicott (1971) argues that we are born and we live within unequal power structures. However, as independent thinking beings we cannot simply submit to these power structures: rather, we require recognition of our independence by those who hold positions of power within these structures. In power asymmetry, this recognition is not automatic and results in politics between the “self” and the “other”. The roots of politics are hidden in mutual recognition, which involves emotions of anxiety in the face of (perceived) existential threats. The ideas of existentialism are premised on the fact that human beings desire to live independently, but in order to live independently they are dependent on the other. That is, the “…self’s wish for absolute independence conflicts with the self’s need for recognition” (Benjamin 1990, p. 39). This implies that the self is created through the other: however, we do not want to defeat the other but rather to maintain a state of difference and provocation that enables our own continuity (Cooper and Burrell 1988).

In this political struggle, sometimes the more powerful actor in the relationship does not give recognition to the other. This results in a heightened anxiety. To lower this anxiety the individual (not recognized by the actor who occupies the more powerful position) creates a false self, or a political self. This false self is a facade that is created in order to allow them to stay in a relation vis á vis the other. However, in the process this false self overshadows the individual’s potential as regards their true self, which is a creative self (Winnicott 1971). According to Ogden (1986, p. 144, quoting Ogden 1976) “[f]unctioning in this [false self] mode can frequently lead to academic, vocational, and social success, but over time the person increasingly experiences himself as bored, “going through the motions,” detached, mechanical, and lacking spontaneity.” The false self is, therefore, a state of fantasy (a defensive mechanism) and reflects inertia. This inertia maintains a status quo.

Winnicott perceives individual identity in relations to human beings’ potential of learning. He observes identity construction and learning both to be a mental activity. In this sense, Winnicott understands that our cognitive or conscious side harbors fantasies and aspirations, which cause us to engage in a form of play. He links these fantasies to our potential for learning and creativity. However, our potential for learning is intertwined with our identity, in a social space, in a dilemma of mutual recognition: i.e., our identity needs recognition by the other in order to be able to add to the process of creative endeavor. However, he argues that there is a constant interplay between our conscious (reality) and unconscious (fantasy) whereby identity is constructed either as a true self or a false self. The catalyst between the true and false self is the holding environment of trust and understanding. Winnicott therefore argues that learning takes place in this interplay and not at the poles.

This interplay essentially means that human beings cannot live in a perpetual state of consciousness, as it is too exhausting. Moreover, in a social space unconscious manages the level of anxieties through individuals’ defenses that act as a protection mechanism. If individuals do not have these defenses as a healing mechanism, it could lead to a psychological collapse. These defenses are used by all of us to some degree to manage the situations that threaten the ego or our self-esteem (Vince and Broussine 1996). However, if these defenses are not checked we lose our sense of responsibility towards ourselves, towards others and also towards a society as a whole.

Winnicott (1971), in this sense perceives the resolution of these defenses (politics) as occurring in a holding environment of trust and understanding. It is this holding environment that helps an individual to develop a true self that has the potential for learning/transformation. The true self is therefore the responsible self. This makes the “holding environment” an ontological position (Ogden 2004): in this mutual space, creativity and human progress are realized in human beings’ responsible behavior toward each other. This shows that there is no such thing as unlimited freedom: rather, there is only a freedom that is imbued in humanism (a sense of responsibility)—”Man is the future of man” (Sartre 1948, p. 38), where “…the first effect of existentialism is that it puts every man in possession of himself as he is, and places the entire responsibility for his existence squarely upon his own shoulders. And, when we say that man is responsible for himself, we do not mean that he is responsible only for his own individuality, but that he is responsible for all men”(Sartre 1948, p. 31)

In its focus on dialectic, Winnicott’s work chimes with the Foucauldian circular argument of power. The thrust of Foucault and Winnicott’s works lies in bringing to the center the inequality that becomes the basis of human suffering, which leads to political struggles. Human suffering, as perceived in existentialism, shows that regimes of truth reflect deep unconscious desires to live an independent existence. Existentialism thus posits that dependence is a necessary condition for independence, while inequality is a necessary condition for resistance (Mahoney and Yngvesson 1992). Foucault, in this sense, perceives power to be enabling as well as disabling, and sees political struggles as perpetual and central for human continuity—a continuity that involves new configurations and meanings (ibid.). However, in a psychological understanding, inequality does not lead to a new configuration without being addressed in a “holding environment”. Thus, the holding environment is an ontological position: it provides a space for social justice, where human beings’ responsible behavior is realized.

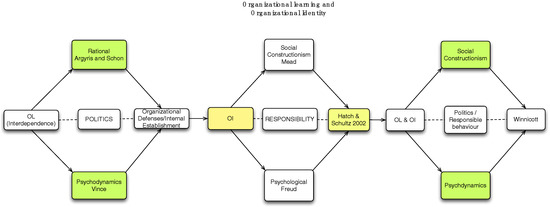

3. Conceptual Framework

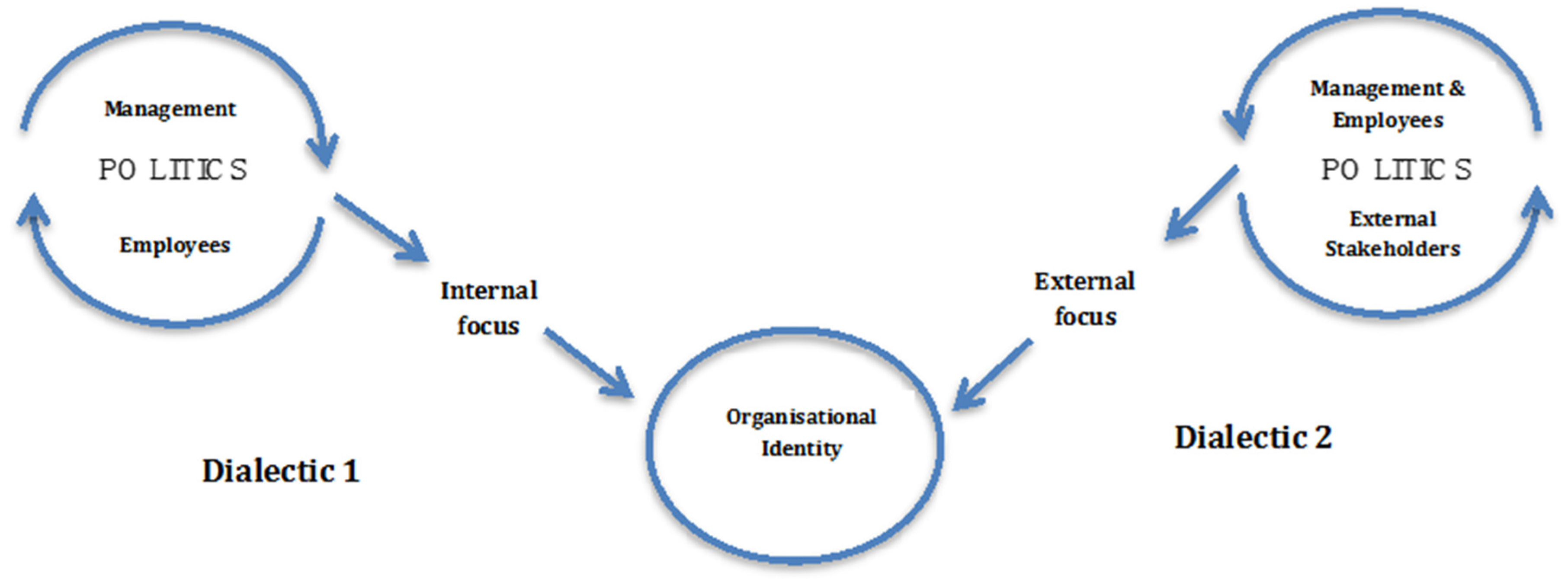

Winnicott’s model consists of two parts: identity and learning. The identity part finds a parallel in the Hatch and Schultz model and the learning part finds a parallel in Argyris and Schön’s, and Vince’s, conceptualization. The present research operationalizes Hatch and Schultz’s (2002) model in Winnicott’s understanding, as demonstrated in the following schematic diagram (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

OI’s Political Framework.

In a power asymmetry, management and employees are linked in a dilemma of mutual recognition, among themselves and also with their key external stakeholders. Therefore, the present research explores two sides of OI: the internal focus between management and employees, and the external focus, as seen between management and employees and key external stakeholders. The present research refers to the politics played out in the dilemma of mutual recognition as ‘psychological politics’. In the Winnicottian framework there are two sides to identity formation: a balanced/responsible or true self, and a political or narcissistic false self. In this sense, Winnicott’s work does not accommodate the hyper-adaptability side of Hatch and Schultz’s (2002) model. Argyris (1992) also argues that in his more than 40 years of research experience, the common tilt of an organization overtime is toward narcissism (organizational defensive routines). However, the human mind is very complex and the present research concedes that there could be numerous permutations and combinations of defenses. However, taking Winnicott’s model as the guiding framework, the present research focus is on a true or balanced/responsible self and a false/narcissist political self.

In this sense, psychological politics are seen as narcissistic, reflecting the false self of the organization. By contrast, learning is only possible when it involves a mature responsible self that is a true self. Winnicott perceives identity to be intertwined with learning, and in this sense his model also adds the angle of learning to Hatch and Schultz’s (2002) model of OI. In the present research, OI can hence be defined as “cognitive” and “emotional” understanding of “self” and “other”, as perceived in the dilemma of a mutual recognition. In the present research OI is operationalized through social constructionist and psychodynamics frameworks. The operationalization of social constructionist framework is further informed by a Foucauldian understanding of power and politics: by exploring how politics are played out in unequal power relationships between the management and employees in the dominant discourses and discursive practices of the organization. For psychodynamic analysis, the present research uses Winnicott’s model of identity construction and learning. The research is operationalized through the following sub-questions.

3.1. OI

- OI internal focus: How are politics played out in a dilemma of mutual recognition between the management and employees?

- OI external focus: How are politics played out in a dilemma of mutual recognition between the management and employees with the key external stakeholders?

3.2. OL

The research also seeks to understand the political implications of OI for OL, as perceived in the dilemma of mutual recognition. In this regard it seeks to understand: How is OL affected by the politics played out in a dilemma of mutual recognition between the management and employees and the key external stakeholders?

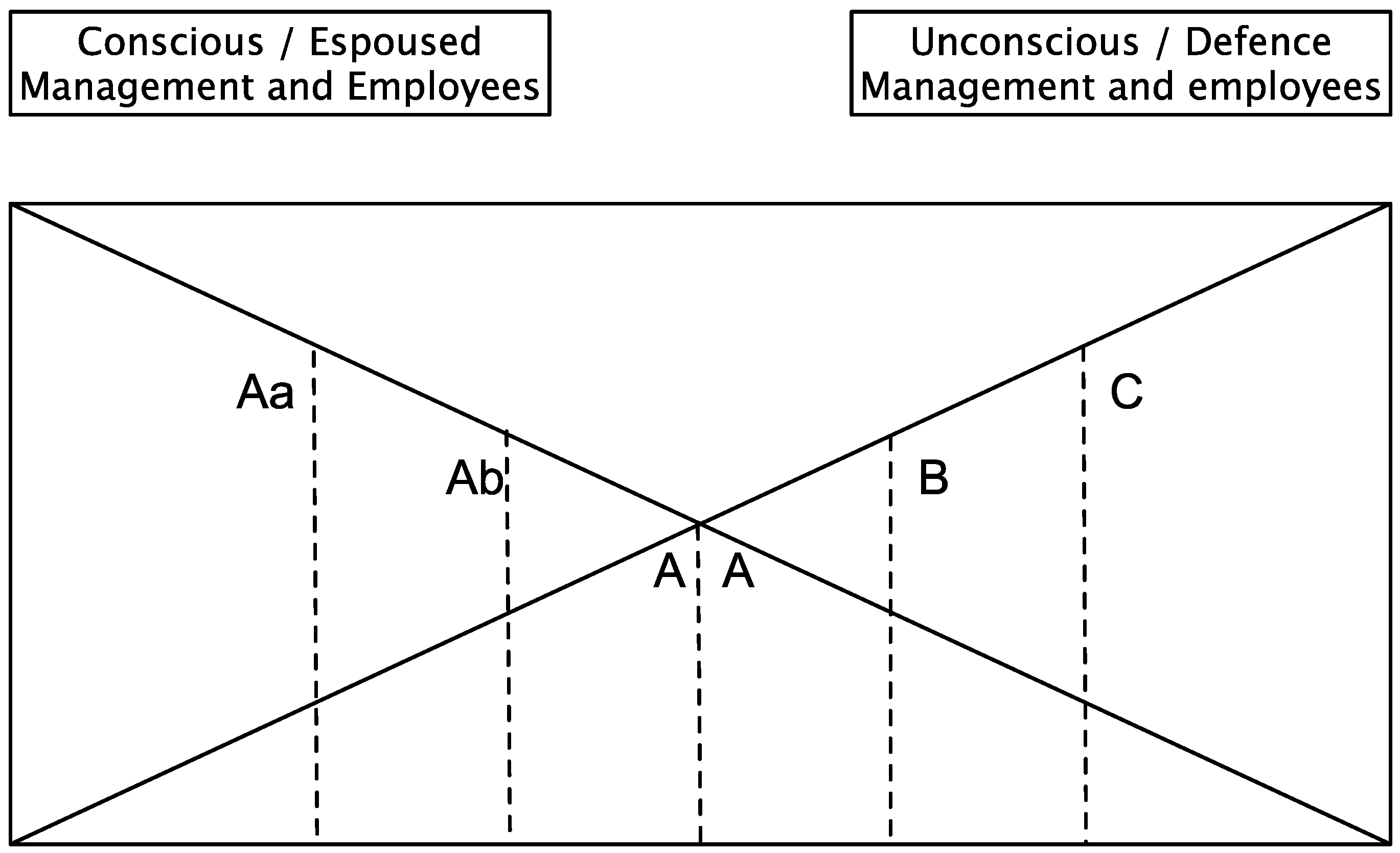

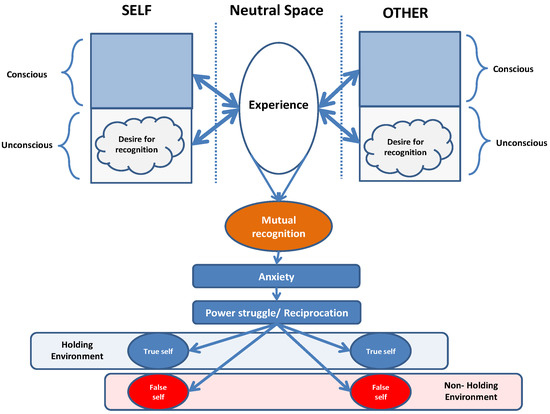

Winnicott’s model, for the first time in OL scholarship, theoretically shows that learning takes place in an interplay between conscious and unconscious, realized in a holding environment. The present research shows this using the schematic diagram below. Note that the intention here is to make this point of interplay explicit, rather than claiming that the human mind could ever be explained in a stationary diagram (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

OI intertwined with OL.

In this diagram, management and employees, in their motivational fantasies or what Argyris calls espoused meanings, are shown on the left side of the diagram, which represents the conscious side of the mind. Similarly, management and employees, in their defensive mode, are shown to the right side, depicting the unconscious side of the mind. The diagram shows that OL is not possible at the poles (either total conscious or total unconscious) but takes place in the interplay between conscious and unconscious. The point of integration (between self and other) could be assumed to be approximately Aa, Ab or A, where all organizations strive to be (though they are usually more to the right, at point B, which is more tilted toward a defensive mode, though still in interplay). This point B approximates with Argyris and Schön’s (1978) consistent observation that OL, is usually hampered by a defensive behavior. Hence, going from B to point C shows that OL has gone a step further back. It is crucial for organizations to remain toward the conscious side of learning. This requires organizations to construct an OI, which represents a responsible true self. However, this interplay also shows that, within organizations, all is not necessarily bad—in other words, there are shades of responsible behaviors that keep an organization in this interplay. If this interplay collapses the organization is bound to fail.

4. Context of the Research

This research was conducted in the context of the Pakistani Police. However, before explaining this context, the present research first of all introduces policing in the pre-colonial, colonial and post-colonial periods. In pre-colonial times, the Mughals exercised their authority in civil matters through an elaborate system of policing. While a basic informal system operated in villages, cities had more elaborate structures, where Kotwals (city police officers), not only maintained law and order and controlled crime but also dealt with all sorts of administrative and regulatory functions, like checking weights and measures, regulating the movement of people into and out of cities, and other civic functions. The Mughal system placed a heavy responsibility on Kotwals: for instance, in the case of non-detection of stolen property, they would face the penalty of paying compensation to the victim. In practice, this was a rare occurrence, as a Kotwal using his unchecked powers could coerce the victim into silence and a retraction of the complaint. The relationship between a Kotwal and his subordinates was strictly hierarchical and the treatment of citizens was not strictly rule based, with citizens often the victim of Kotwal unchecked powers. The effectiveness of enforcement was variable between districts. The concept of the rule of law was weak and the only factor in determining the quality of policing was fear of the king, with all of the physical limitations this implies.

With the British takeover of the subcontinent from the East India Company after the revolt of 1857, a formal policing system was established under the Police Act 1861. This laid the foundations of modern policing in the subcontinent. Police powers were defined under a legal framework and the hitherto unchecked police powers were placed under the supervisory control of a civilian District Magistrate (DM), who also exercised basic judicial functions and tried minor crimes, in addition to his role as general administrator of the district. The police, under a Superintendent of Police (SP), were responsible for crime control and also assisted the DM in the maintenance of general law and order. This largely introduced the rule of law, with criminal matters ending up in, and being decided in, a formal system of courts that dispensed criminal and civil justice. However, in matters that were of interest to the British Raj, the police acted as an instrument of the perpetuation of British colonial rule. The key features of the British police system were, (i) a duality of control whereby in addition to the SP’s operational control over police, the DM also exercised somewhat intrusive control over their operational matters, and held them to account for their performance; and (ii) the concentration of authority in the police hierarchy, whereby from the Station House Officer (SHO) to the SP, all functions, like watch and ward, traffic and investigation were exercised by the same individuals.

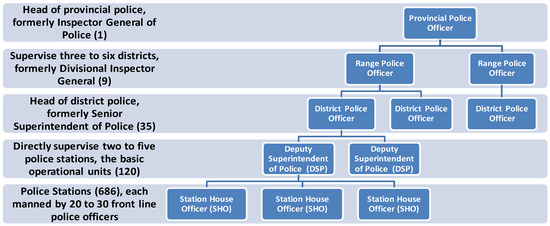

The post-colonial policing did not differ much from the colonial period, especially in terms of the operating laws and rules. The internal organizational hierarchy and the external relationships remained unchanged. The key changes, observed over a period of time, were a decline in the quality of policing and discipline, and an increase in corruption. A key departure from the pre-colonial tradition was a steep jump in political interference and the influence of feudal elites in the affairs of the police. With the passage of time, the citizens’ trust in the police was significantly eroded, and the performance of the police sharply declined. All of this happened in tandem with an erosion in the performance of other institutions of the state. The relationship between the SP and the DM continued, albeit somewhat strained, with the DM retaining the overall—but gradually declining—primacy. The current structure of the Pakistani police is given in Figure 5 below. It also indicates the former structure: Inspector General (IG) is now called Provincial Police Officer (PPO); Deputy Inspector General (DIG), is now the Range Police Officer (RPO); and Superintendent of Police (SP) is now the District Police Officer (DPO). Apart from the change in nomenclature, there has been no change in hierarchy or their responsibilities.

Figure 5.

Pakistani Police Organizational Chart.

In 2002 the military government introduced reforms of the police, under the Police Order 2002. The Police Order 2002 aimed to reform the police force: the thrust of the Police Order 2002 was to create a people-friendly police force that was more aligned with the democratic needs of the country. Efforts to change the old model, as defined in the Police Act of 1861, had started soon after the partition, or the independence of Pakistan, from 1947 onwards. However, the political platform for making real change was finally provided in 2002 by the advent of army rule: the army wanted to legitimize its rule by showing democratic shades, through various reforms. The Police Order 2002 was one of these reforms. The main agenda of the Police Order 2002 was to abolish the office of the DM as holding a dual control with the police, by shifting the accountability of the police from the DM’s office to the Public Safety Commission (PSC), which comprises retired or in-service honorable members of the society. This involved introducing specialization in the operating level, by separating the police’s function of watch and ward from that of investigation. The main aim was to make the system fair, and also to make crime control and investigation services more effective.

5. Data Collection

The present research is based on an interpretive paradigm and operationalizes OI in a social constructionist framework. Its application of power is informed by a Foucauldian perspective, as seen in the discursive and non-discursive practices of the Pakistani police. The deeper meanings are deciphered in the Winnicottian framework of psychodynamics, as perceived in a dilemma of mutual recognition. The present research uses narratives to connect the social constructionist and psychodynamic perspectives. For the research, 25 semi-structured narrative interviews were conducted: 15 with police officials and 10 with key external stakeholders. The police force interviews were conducted during a tense period during which the police were the main targets of terrorist attacks. Therefore the interview venue often changed and the interviews were sometimes rescheduled. I carried out eight interviews with the senior police management and seven with the operational tiers. The external stakeholders consisted of five DMs, two legal professionals, one development consultant and two ordinary citizens. The interviews lasted for 45 to 60 minutes. The interviews were recorded by taking consent from the interviewees. Eight interviews were conducted using Skype and the rest were carried out face to face in police stations, senior management offices, and government rest houses. Due to the tense situation within the country and the very busy schedules of both police officers and DMs the samples were selected through network connections, depending on who was available at the time.

The interviews were open-ended and probing questions were asked when necessary. The focus of the questions was on “how” and not on “why”, as why questions imply a value judgment and put the interviewee in an uncomfortable position. Moreover, for a psychodynamics study “why” questions would make analysis difficult as this may raise the interviewee’s defenses and hence block meanings and open interactions. The main questions stayed around the theme of reforms, trying to understand the reasons behind the reforms and also trying to decipher the reason for their failure. “A narrative, in its most basic form, requires at least three elements: an original state of affairs, an action or an event, and the consequent state of affairs” (Czarniawska 1998, p. 2).

The interviews were conducted in three main languages: Pushto, Urdu and English. Pushto and Urdu interviews were first translated and then transcribed. In transcriptions attention was paid to the smallest details, like the sound of a person coughing or a lowering of the voice, in order to record the emotions that are the main framework of the present study. The research was supplemented by the observational method of maintaining a reflexive diary, as well as by relevant secondary sources. Observing and reflecting is second nature to human beings. Reflexivity kept me engaged with the feeling of “doubt’” (Locke et al. 2008), which made me engage in critical self-reflection by exploring my own interpretations of empirical material (e.g., Alvesson and Skoldberg 2000). I observed that my network connection often initially put the lower tiers in an uncomfortable position, and I found that building trust between the interviewer and interviewee was key to getting a valid and reliable account of the events being studied.

The reflexive diary also helped me make notes of the various discursive and non-discursive practices of the police. For example, I noted the difference between the luxurious air-conditioned offices of the senior management and the open verandas where the public have to wait to see the senior officers on hot summer days. This made me reflect on how the management espoused a form of friendly policing, but they were not concerned about the conditions that the public faced in meeting them. The luxurious offices of the officers showed the police’s non-discursive practices, which seemed to follow the setup of the colonial times. This led me to consider the question: was the colonial system of policing really as uncomfortable for the police as the senior management suggested it was throughout the interviews?

The secondary data consisted of organization reports, international donor reports, Transparency International reports, crime statistics, minutes of meetings, press releases, websites that I visited, media reporting that I followed, and archival data, as well as reports from bilateral and multilateral development agencies and rights groups.

6. Data Analysis

The objective of analyzing data is to produce a coherent, intelligible and valid account (Dey 1993). The analysis requires breaking the data into smaller bits so that the data can be classified. However, there is no set of rules or specific recipe for analyzing data that will provide the best results (Boulton and Hamersley 2006). Qualitative data requires a degree of interpretation and creativity, which can account for why different researchers produce different analyses for the same data (ibid). Hence, qualitative data collection and analysis is often considered more subjective than the analysis of quantitative data (Neuman 2011). However, Kirk and Miller (1986) argue that qualitative social science research can still be evaluated in terms of its objectivity, by way of the reliability and validity of its observations.

I received help from a colleague who worked on the data independently. It was encouraging to me that he saw similar themes to those I identified, although his labelling was different. Group data in itself brings some authenticity through the common voices of the group; e.g., common management themes were their aspirations, and the problems that came in their ways; and for employees it was predominantly the practical difficulties encountered in adopting these reforms. However, the exercise is not straightforward and is also not done in one go. Rather, the analysis involves reading and re-reading transcripts, repeatedly listening to audio recordings, grouping or clustering the data for interpretation and to identify relationships, and questioning, checking and verifying transcripts to ensure the validity of findings (Janesick 1994). I also started the initial phase of the data analysis by listening to the recordings while checking the accuracy of the transcripts. This gave me the opportunity to re-familiarize myself with the data and to go through the field-notes that I made during the interviews.

The data was analyzed using Riessman’s (2008) narrative methodology. Narrative methods were specifically selected to engage with the emotions of the police officials, especially as seen in the unequal structure of the social setup both within and outside the organization. In this way the present research used all three of Riessman’s narrative analysis techniques: i.e., content, context and performance. Content techniques focus on what is said and help decode themes in a general understanding, without going into context. However, the narrative is always articulated in a context that brings dialectic to the center, whereby individual talks of both the personal and collective (institutional) discourse (Ybema et al. 2009). Dialectics bring to the center the political nature of the narratives: i.e., “It is impossible to understand human conduct by ignoring its intentions, and it is impossible to understand human intentions by ignoring the settings in which they make sense” (Czarniawska 1998, p. 4; quoting, Schütz 1973). Thus, in an unequal distribution of power, politics are central to narratives, and narratives are underpinned in emotions. In this sense, the performance analysis helps understand the narrative in its deeper emotions, as seen in stresses, repeated words, and what is said and not said. The “… dialogic/performative approach asks “who” an utterance may be directed to, “when,” and “why,” that is, for what purposes?” (Riessman 2008, p. 105).

To start the analysis of the interviews the questions were first removed to help improve the understanding of the narratives. Since the questions were open-ended, with probing questions added in between, by removing the questions the narratives appeared in a continuous way. In this sense, attention was paid to “… the whole data and paying attention to links and contradictions within that whole” (Hollway and Jefferson 2000, p. 5). By this the present research means that the social and psychological context were focused together, by looking at the stresses, repeated words, justifications, rationalizations, projections onto others to see how narratives expressed the self-interests of the narrator/interviewee. The present research did not utilize any software, as the focus was on the psychological dimension of politics. In a psychological sense, it is possible that the same words might not provide the same meanings each time they are used, and the researcher needs “to do justice to the complexity of [their] subjects” (Hollway and Jefferson 2000, p. 3).

The research’s prime focus was the police; therefore, police narratives were used as the main framework to identify the patterns and relationships, in order to locate the issues in the reform agenda. The DMs and legal professionals’ interviews were used to understand the issues identified by the police, as these individuals work in parallel with the police. However, here also, patterns were located to understand the words, stresses and linkages in which they gauged the issues that were identified in the police narratives. The other external stakeholders were generally asked questions about the police’s image, to understand the police and community interface. In this way, the present research engaged with the data relating to the police.

Initially, the data was loosely categorized into as many clusters as was necessary, and only when this was achieved were the clusters with similar ideas grouped together. The clusters were formed based on the use of repeated words, which brought three broad themes into focus: police history, police performance and police autonomy/power vis á vis the other. The process of identifying the broad themes seemed to be aligned with the Riessman content analysis, which allowed me to understand “what was told” and not “how it was told”. The telling part required Riessman’s context analysis.

For context analysis, a spreadsheet was prepared and the broad themes were put at the top. The name and role of each police official (management and employees) was put on the side, to understand how they perceived these three broad themes in the wider social context. While understanding police narratives in the social context, the “self /other” perspective came to the center, where the interviewees would narrate the stories conveying the meanings beneficial to the self (e.g., Riessman 2008; Bruner 1991). The stories capture “self /other” talk in the politics played out in the blame games. The political games were seen in rationalizations, projections on others, justifications and at times frustrations of the interviewees on the current political situation of the country. The narratives of the police management and employees were somewhat similar in the blame games but essentially both had two different focuses. Police management interviewee (PMI) narratives were evaluated with respect to the PMIs’ aspirations: they blamed the “others” throughout their interviews in order to rationalize a need for change/reforms. This ‘blame game’ started in the historic period and extended to all those who stood in the police’s way in regard to developing an effective police system for Pakistan. The employees’ narratives were based on the practical side of their jobs: they blamed “others” to show how inappropriate the reforms were, from a practical point of view.

Politics, as seen in these blame games, were loaded with emotions, for example involving anger, stresses and repeated words in relation to the “others”. Riessman (2008) argues that the order of an analysis is not important. Therefore, I merged performance with the context, and thus disregarded the order, to better understand who the significant “other” was that was blamed the most. In this sense, to understand the context of the present research, the data was understood by reference to the social constructionist and psychodynamic frameworks. The social constructionist and psychodynamic frameworks stress the “need to posit research subjects whose inner worlds cannot be understood without knowledge of their experiences in the world, and whose experiences of the world cannot be understood without knowledge of the way in which their inner worlds allow them to experience the outer world” (Hollway and Jefferson 2000, p. 4).

In the performative analysis, the meanings were gauged in the way police officials emotionally framed the significant ‘other’ in the blame game. The PMI narratives showed that the reforms agenda was predicated on their need for “autonomy” and employees’ narratives showed that the reforms were seen as an attack on their “autonomy”. This allowed me to see that the reforms were articulated in the overarching theme of “autonomy versus control”, with reference to the significant “others”. However, the police management interviews made it difficult to locate the significant other, as PMIs were not direct in their accusations and blame. It was their stresses, concealment games and what was not said that led me to believe that their aspiration was independence from the DMs, to strengthen their control over employees and to make the police an effective organization for Pakistan. The employees, on the other hand, were loud, clear and accusatory in their blame game, and tones of anger were used. For them, the significant other was the community, which they perceived wished to take away their autonomy (through citizen oversight bodies).

The interplay of autonomy versus control brought to the surface the politics between the two. This showed that the PMIs were embroiled in psychological politics in a dilemma of mutual recognition with the DMs; and the employees on their part were engaged in a dilemma of mutual recognition with the community. In my research, four themes appeared to stand out, each with its own explanation in a dilemma of mutual recognition: (1) the repressive origins of policing, (2) the duality of control, (3) the police oversight and (4) the forgotten (operational-level) employees. I sum up the analysis of the interviews with Pakistani police in Table 1 below.

Table 1.

Narrative Analysis.

6.1. The Repressive Origins

The theme of the historic period was central to all the interviews that were conducted with the police. The Pakistani PMIs made the colonial police system the premise for introducing reforms in 2002, with the stated aim being to improve police performance. However, my deeper analysis shows that the seductiveness of power continued, whereby the PMIs actively supported the efforts to abolish the oversight and control of the DMs. The operating level of the police, on the other hand, seemed to carry the historic narrative forward as a ritual, as they had no problems with the British Act of 1861: in fact, they were the beneficiaries of the Act, under which the SHO enjoyed unlimited powers.

In colonial times, the British/Europeans held the positions of DMs and Superintendent of Police (SPs): the natives only worked at the operating levels, as constables, inspectors and so on. One of the DMs, in an interview, revealed that a few letters were found in archival documents that showed a very strong tussle between the DMs and the SPs even in the colonial times: i.e., among the British/Europeans.

India and Pakistan both inherited the British system of police and while doing my research I also came across a news story on the tussle between the Indian DMs and SPs, which was widely circulated in Indian newspapers. The gist of the news story was captured in the following words: “‘It all began after SP Mohit Gupta ordered transfer of a few police station in-charges, replacing them with other officers at some of the police stations in Sidharthnagar. As per the practice, the SP office issued the transfer posting orders and dispatched a copy to the DM office for information sake,’ said the source. ‘Things began to turn ugly when the DM took strong exception to the orders of the SP “without her prior approval”. As a result, the DM not only cancelled the orders issued by the SP but went ahead to announce that no police officer would be posted as the police station in-charge unless and until he is interviewed by her to decide if he was capable of shouldering the responsibility’” (Siddiqui 2012). This shows that politics were intrinsic in the dual control of the DMs/DPOs, which finally resulted in the termination of the DM’s role in the affairs of the police in Pakistan. In a narrative analysis, the politics could be detected in the ways the PMIs made the Police Act 1861 an excuse to remove the dual position that they had held with the DMs for more than a century. PMI 1.2 said: “The Police Act 1861 and the Police Rules of 1934 were used to subjugate the masses…it was these rules that adversely affected our performance.”

However, in the narratives of the PMIs resentment was visible in regard to the dual control with DMs. PMI 1.1 said: “The responsibility for law and order was primarily with the DM, who was the head of the district, head of the revenue and head of the police...he was a sort of mini-governor…the DM headed 40 different functions and his connection with the police was only because of his being DM”. This interview captures the PMI’s emotional stresses in words like “mini-governor” and “40 different functions”, and shows that the main problem for PMIs was not the outdated British model, but the dual control with the DMs: the PMIs felt frustrated that the DMs had a higher status in terms of power and image within the society, compared to the police.

This psychological politics seems to have motivated the top leadership of the police to fully support the reforms initiated by the military government, without necessarily mirroring any public demand. PMI 1.3 said: “These [three senior police officers] were the three main architects, as far as I know, of this entire law. They did consult police. I am not sure whether that consultation was very...uh...deep in its nature”. This point seemed important as I noticed a similar debate on an Indian TV program, where the anchor person asked a senior police officer the following question: ‘as police leadership you know the internal issues; why don’t you bring about change?’ The senior police officer conceded: “Why would we, who are in power, change the system as we are its biggest beneficiaries? Change has to come from outside; it has to be in response to public demand” (Khan 2012). Interestingly, the senior management of the Pakistani police got an opportunity to shape the reform and they actually used it in their favor. DMs historically were a bone of contention for the police management, and in the case of the Pakistani police this became the main reason for the overwhelming support of senior police management for introducing the reforms of 2002, which largely focused on doing away with the control of the DMs over the police.

6.2. The Dual Control

As discussed above the PMIs targeted the Police Act 1861 that introduced the concept of a dual position with the DMs. The DMs were, therefore, the sore spot, to which senior police never referred directly, and which I captured by identifying the emotions that came to the surface—they never uttered a single word against the DMs: in the interviews they exhibited concealment, avoidance, and uncomfortable twisting in the chair, or saying with visible under-confidence, “you know the DMs used to work with us”. These games were revealed in various tones and stresses that showed their psychological politics with the DMs. This led me think of the DMs in the PMIs’ interviews as the “invisible intruders.”

In games of concealment the PMIs blamed everything on historic times, not once quoting specific examples of what happened in the present time that made the police relationship uncomfortable with the DMs. For example, PMI 1.1 stated: “the DM would tell the police to ‘catch him and bring him, lock him up for this long’ or ‘thrash him’ and the police officers working under him would do it. There was no [internal] accountability [to senior police], rather a lot of confusion, and shifting of blame”. PM1.1 was never direct in referring to modern DM intrusion, instead making reference to the historic period. He never gave any example to show that such practices took place in the present time.

To check the practices involving DMs and the police, from a DM’s perspective, I refer to the interviews with DMs. DM 3.2 stated: “...[The] Deputy Commissioner (DC/DM) had been given quite a lot of powers, as prescribed in the law, but they were not exercising those. For example, the Law of 1861 required that the SP would seek the DC’s [DM’s] approval for the transfer of a SHO. I cannot recall even a single incident where this was being done. The police were fairly independent in their decision-making...So I don’t think the issue of autonomy was there, or [that] they were [under] control of the executive magistrates”.

The DM’s reference to autonomy clearly shows the dilemma of mutual recognition between the police management and DMs. In his interview, the DM insisted that they never interfered in regular police practices. They were two independent groups serving the community. The DM in the interview clarified further that, as district heads, they made the police accountable for their performance in the district and also took decisions at difficult times; otherwise, both worked independently. DMs were required to use their coercive power in a legal functional capacity during the exercise of their judicial authority, the exercise of which was also subject to subsequent judicial review in higher courts. Since the DMs and police routinely worked in two different organizations, there was no chance for the DMs to exercise any dominating power that would shape the thoughts of police employees or the police culture. On the other hand, however, according to one DM, the magistracy provided a buffer for the operational-level police in their encounters with a protesting public, and had an overall tempering effect on crowd emotions, due to their perceived neutrality—or the fact that they were seen as not being part of the police.