Success through Trust, Control, and Learning? Contrasting the Drivers of SME Performance between Different Modes of Foreign Market Entry

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theory

2.1. SME Internationalization

2.2. Characteristics of Arab Markets

2.3. Trust, Control, and Learning

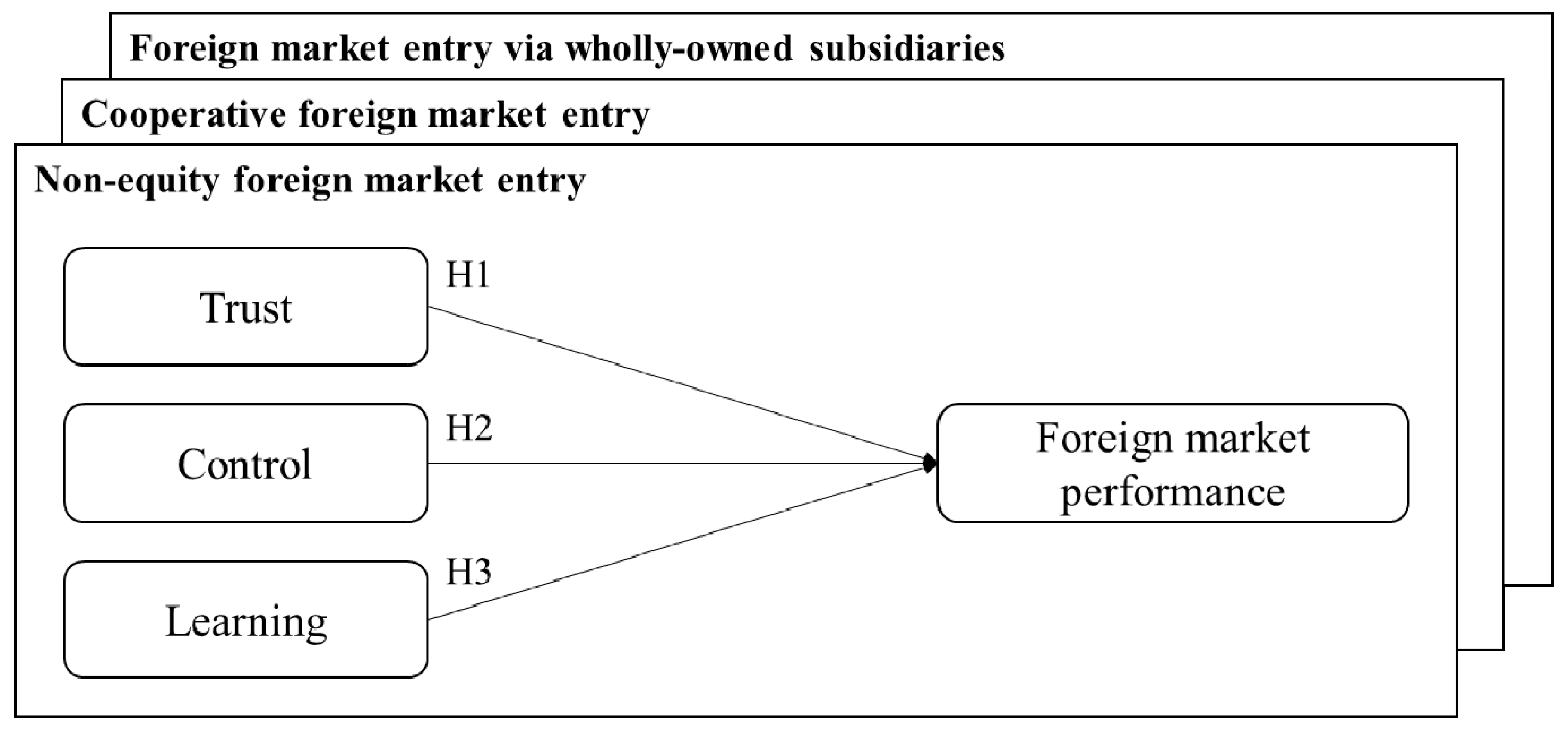

3. Hypotheses

3.1. Trust and Foreign Market Performance

3.2. Control and Foreign Market Performance

3.3. Learning and Foreign Market Performance

4. Research Methods

4.1. Sampling and Data Collection

4.2. Measures and Validation

5. Results

6. Discussion

6.1. Research Contributions

6.2. Managerial Contributions

6.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

7. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aulakh, P.S., M. Kotabe, and A. Sahay. 1996. Trust and performance in cross-border marketing partnerships: A behavioral approach. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1: 1005–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H., D. Kelley, J. Lee, and S. Lee. 2012. SME survival: The impact of internationalization, technology resources, and alliances. J. Small Bus. Manag. 50: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y., and D.K. Tse. 2000. The hierarchical model of market entry modes. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 31: 535–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morschett, D., H. Schramm-Klein, and B. Swoboda. 2010. Decades of research on market entry modes: What do we really know about external antecedents of entry mode choice? J. Int. Manag. 16: 60–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beamish, P.W., and J.C. Banks. 1987. Equity joint ventures and the theory of the multinational enterprise. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 18: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S. 1994. Socio-cultural distance and the choice of joint ventures: A contingency perspective. J. Int. Mark. 1: 63–80. [Google Scholar]

- Hennart, J.F., and J. Larimo. 1998. The impact of culture on the strategy of multinational enterprises: Does national origin affect ownership decisions? J. Int. Bus. Stud. 29: 515–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitsch, D., P. Beamish, and S. Makino. 1996. Entry mode and performance of Japanese FDI in Western Europe. Manag. Int. Rev. 1: 27–43. [Google Scholar]

- Woodcock, C.P., P.W. Beamish, and S. Makino. 1994. Ownership-based entry mode strategies and international performance. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 25: 253–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouthers, K.D., and G. Nakos. 2004. SME entry mode choice and performance: A transaction cost perspective. Entrep. Theory Pract. 28: 229–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasheed, H.S. 2005. Foreign entry mode and performance: The moderating effects of environment. J. Small Bus. Manag. 43: 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldrich, H., and E.R. Auster. 1986. Even dwarfs started small: Liabilities of age and size and their strategic implications. Res. Organ. Behav. 8: 165–186. [Google Scholar]

- Maekelburger, B., C. Schwens, and R. Kabst. 2012. Asset specificity and foreign market entry mode choice of small and medium-sized enterprises: The moderating influence of knowledge safeguards and institutional safeguards. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 43: 458–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakos, G., and K.D. Brouthers. 2002. Entry mode choice of SMEs in Central and Eastern Europe. Entrep. Theory Pract. 27: 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, P.J. 1989. Foreign direct investment by small and medium sized enterprises: The theoretical background. Small Bus. Econ. 1: 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.W., and P.W. Beamish. 2001. The internationalization and performance of SMEs. Strateg. Manag. J. 22: 565–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Child, J., and L.H. Hsieh. 2014. Decision mode, information and network attachment in the internationalization of SMEs: A configurational and contingency analysis. J World Bus. 49: 598–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laufs, K., and C. Schwens. 2014. Foreign market entry mode choice of small and medium-sized enterprises: A systematic review and future research agenda. Int. Bus. Ref. 23: 1109–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkema, H.G., J.H. Bell, and J.M. Pennings. 1996. Foreign entry, cultural barriers, and learning. Strateg. Manag. J. 17: 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inkpen, A.C., and S.C. Currall. 2004. The coevolution of trust, control, and learning in joint ventures. Organ. Sci. 15: 586–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhok, A. 1995. Revisiting multinational firms’ tolerance for joint ventures: A trust-based approach. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 26: 117–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Child, J., and D. Faulkner. 1998. Strategies of Cooperation: Managing Alliances, Networks, and Joint Ventures. Oxford, NY, USA: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C., S.T. Cavusgil, and A.S. Roath. 2003. Manufacturer governance of foreign distributor relationships: Do relational norms enhance competitiveness in the export market? J. Int. Bus. Stud. 34: 550–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtgrave, M., A.-M. Nienaber, and C. Ferreira. 2016. Untangling the trust-control nexus in international buyer-supplier exchange relationships: An investigation of the changing world regarding relationship length. Eur. Manag. J. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherer, S.A. 2003. Critical success factors for manufacturing networks as perceived by network coordinators. J. Small Bus. Manag. 41: 325–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, E.W. 2001. Internationalizing the family firm: A case study of a Chinese family business. J. Small Bus. Manag. 39: 88–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunetto, Y., and R. Farr-Wharton. 2007. The moderating role of trust in SME owner/managers’ decision-making about collaboration. J. Small Bus. Manag. 45: 362–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Street, C.T., and A.F. Cameron. 2007. External relationships and the small business: A review of small business alliance and network research. J. Small Bus. Manag. 45: 239–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, S., J. Hamill, C. Wheeler, and J. Davies. 1989. International Market Entry and Development: Strategies and Management. Hemel Hempstead, UK: Wheatsheaf. [Google Scholar]

- Armario, J.M., D.M. Ruiz, and E.M. Armario. 2008. Market orientation and internationalization in small and medium-sized enterprises. J. Small Bus. Manag. 46: 485–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camisón, C., and A. Villar-López. 2010. Effect of SMEs’ international experience on foreign intensity and economic performance: The mediating role of internationally exploitable assets and competitive strategy. J. Small Bus. Manag. 48: 116–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, W.E., and J.M. Sinkula. 1999. The synergistic effect of market orientation and learning orientation on organizational performance. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 27: 411–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, J., and A. Delios. 1997. Location specificity and the transferability of downstream assets to foreign subsidiaries. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 28: 579–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oviatt, B.M., and P.P. McDougall. 1994. Toward a Theory of International New Ventures. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 25: 45–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.C., P. Hwang, and W.P. Burgers. 1993. Multinationals’ diversification and the risk-return trade off. Strateg. Manag. J. 14: 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, J. 1995. The internationalization of small computer software firms: A further challenge to the ‘tage’ theories. Eur. J. Mark. 29: 60–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autio, E., H.J. Sapienza, and J.G. Almeida. 2000. Effects of age at entry, knowledge intensity, and imitability on international growth. Acad. Manag. J. 43: 909–923. [Google Scholar]

- Johanson, J., and L.-G. Mattsson. 1993. Internationalization in industrial systems—A network approach, strategies in global competition. In Internationalization of the Firm: A Reader. Edited by P.J. Buckley and P.N. Ghauri. London, OH, USA: Academic Press, pp. 303–322. [Google Scholar]

- Ruzzier, M., R.D. Hisrich, and B. Antoncic. 2006. SME internationalization research: Past, present, and future. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 13: 476–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johanson, J., and F. Wiedersheim-Paul. 1975. The internationalization of the firm-four Swedish cases. J. Manag. Stud. 12: 305–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johanson, J., and J.-E. Vahlne. 1977. The internationalization process of the firm—A model of knowledge development and increasing foreign market commitments. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 8: 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrader, R.C. 2001. Collaboration and performance in foreign markets: The case of young high-technology manufacturing firms. Acad. Manag. J. 44: 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S.A., R.D. Ireland, and M.A. Hitt. 2000. International expansion by new venture firms: International diversity, mode of market entry, technological learning, and performance. Acad. Manag. J. 43: 925–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.M., and M.K. Erramilli. 2004. Resource-based explanation of entry mode choice. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 1: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouthers, K.D. 1995. The influence of international risk on entry mode strategy in the computer software industry. Manag. Int. Rev. 1: 7–28. [Google Scholar]

- Root, F.R. 1987. Entry Strategies for International Markets. Lanham, MD, USA: Lexington Books. [Google Scholar]

- Brouthers, K.D. 2002. Institutional, cultural and transaction cost influences on entry mode choice and performance. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 33: 203–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H., and M.Y. Hu. 2002. An analysis of determinants of entry mode and its impact on performance. Int. Bus. Rev. 11: 193–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouthers, L.E., G. Nakos, J. Hadjimarcou, and K.D. Brouthers. 2009. Key factors for successful export performance for small firms. J. Int. Mark. 17: 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erramilli, M.K., and D.E. D’Souza. 1993. Venturing into foreign markets: The case of the small service firm. Entrep. Theory Pract. 17: 29–41. [Google Scholar]

- Erramilli, M.K., and D.E. D’Souza. 1995. Uncertainty and foreign direct investment: The role of moderators. Int. Mark. Rev. 12: 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calof, J.L. 1994. The relationship between firm size and export behavior revisited. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 25: 367–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.-L., and C.-M.J. Yu. 2008. Institutional pressures and initiation of internationalization: Evidence from Taiwanese small- and medium-sized enterprises. Int. Bus. Rev. 17: 331–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacharakis, A.L. 1997. Entrepreneurial entry into foreign markets: A transaction cost perspective. Entrep. Theory Pract. 21: 23–39. [Google Scholar]

- Kotey, B. 2005. Are performance differences between family and non-family SMEs uniform across all firm sizes? Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 11: 394–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, Z., and M.J. Nieto. 2006. Impact of ownership on the international involvement of SMEs. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 37: 340–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, S., R. Edwards, and B. Schroder. 2006. How small born-global firms use networks and alliances to overcome constraints to rapid internationalization. J. Int. Mark. 14: 33–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chetty, S., and D.B. Holm. 2000. Internationalisation of small to medium-sized manufacturing firms: A network approach. Int. Bus. Rev. 9: 77–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oparaocha, G.O. 2015. SMEs and international entrepreneurship: An institutional network perspective. Int. Bus. Rev. 24: 861–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Descotes, R.M., B. Walliser, H. Holzmüller, and X. Guo. 2011. Capturing institutional home country conditions for exporting SMEs. J. Bus. Res. 64: 1303–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narooz, R., and J. Child. 2017. Networking responses to different levels of institutional void: A comparison of internationalizing SMEs in Egypt and the UK. Int. Bus. Rev. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidani, Y., and A. Al Ariss. 2014. Institutional and corporate drivers of global talent management: Evidence from the Arab Gulf region. J. World Bus. 49: 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabasakal, H., and M. Bodur. 2002. Arabic cluster: A bridge between East and West. J. World Bus. 37: 40–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeidat, B., R. Shannak, R. Masa’deh, and I. Al-Jarrah. 2012. Toward better understanding for Arabian culture: Implications based on Hofstede’s cultural model. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. 28: 512–522. [Google Scholar]

- Brake, T., M. Walkerm, and T. Walker. 1995. Doing Business Internationally: The Guide to Cross Cultural Success. Manhattan, NY, USA: McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Schein, E. 1992. Organizational Culture and Leadership, 2nd ed. San Francisco, CA, USA: Jossey-Bass Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Kalliny, M., and L. Gentry. 1998. Cultural values reflected in Arab and American television advertising. J. Curr. Issues Res. Advert. 29: 15–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahin, A.I., and P.L. Wright. 2004. Leadership in the context of culture: An Egyptian perspective. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 25: 499–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A. 1995. Cultural discontinuity and Arab management thought. Int. Stud. Manag. Organ. 25: 7–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavoossi, M. 2000. The Globalization of Business and the Middle East: Opportunities and Constraints. Westport, CT, USA: Greenwood Publishing Group. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, A. 1999. Middle East competitiveness in the 21st century’s global market. Acad. Manag. Exec. 13: 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.S. 1998. Islam Today. London, UK: Tauris Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Rice, G. 1999. Islamic ethics and implications for business. J. Bus. Ethics 18: 345–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, G., and M. Al-Mosawi. 2002. The implications of Islam for advertising managers: The Middle Eastern context. J. Eur. Mark. 11: 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, V., P.J. Hanges, and P. Dorfman. 2002. Cultural clusters: Methodology and findings. J. World Bus. 37: 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- House, R., M. Javidan, P. Hanges, and P. Dorfman. 2002. Understanding cultures and implicit leadership theories across the globe: An introduction to project GLOBE. J. World Bus. 37: 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. 2001. Culture’s Consequences. Thousand Oaks, CA, USA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Sidani, Y.M., and J. Thornberry. 2010. The current Arab work ethic: Antecedents, implications, and potential remedies. J. Bus. Ethics 91: 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rasheed, A. 2001. Features of traditional Arab management and organization in the Jordan business environment. J. Transl. Manag. Dev. 6: 27–53. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, A.J., and R. Wahabi. 1995. Managerial value systems in Morocco. Int. Stud. Manag. Organ. 25: 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, P.N., and M.M. Hussain. 2013. Democracy’s Fourth Wave? Digital Media and the Arab Spring. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer, M., E.S. Yassin, and A. Leila. 1985. Bureaucratic flexibility and development in Egypt. Public Adm. Dev. 5: 323–337. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Yahya, K., and R. Vengroff. 2004. Human capital utilization, empowerment, and organizational effectiveness: Saudi Arabia in comparative perspective. J. Glob. Dev. Stud. 3: 51–95. [Google Scholar]

- Attiyah, H. Roots of organization and management problems in Arab countries: Cultural or otherwise? In Proceedings of the First Arab Management Conference, Bradford, UK, 6–8 July 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Ilmihal, I. 1999. Ilmihal I: Iman Ve Ibadetler. Istanbul, Turkey: Divantas. [Google Scholar]

- Topaloglu, B. 1983. Women in Islam (in Turkish). Istanbul, Turkey: Yagmur Yayinevi. [Google Scholar]

- Moghadam, V.M. 1993. Modernizing Women: Gender and Social Change in the Middle East. Boulder, CO, USA: Lynne Rienner Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Child, J., S.B. Rodrigues, and J.G. Frynas. 2009. Psychic distance, its impact and coping modes. Manag. Int. Rev. 49: 199–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puthusserry, P.N., J. Child, and S.B. Rodrigues. 2004. Psychic distance, its business impact and modes of coping: A study of British and Indian partner SMEs. Manag. Int. Rev. 54: 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulmer, C.A., and M.J. Gelfand. 2012. At what level (and in whom) we trust across multiple organizational levels. J. Manag. 38: 1167–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nienaber, A.M., M. Hofeditz, and P.D. Romeike. 2015. Vulnerability and trust in leader-follower relationships. Pers. Rev. 44: 567–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseau, D.M., S.B. Sitkin, R.S. Burt, and C. Camerer. 1998. Not so different after all: A cross-discipline view of trust. Acad. Manag. Rev. 23: 393–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosmer, L.T. 1995. Trust: The connecting link between organizational theory and philosophical ethics. Acad. Manag. Rev. 20: 379–403. [Google Scholar]

- Turker, D., and C. Altuntas. 2014. Sustainable supply chain management in the fast fashion industry: An analysis of corporate reports. Eur. Manag. J. 32: 837–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geringer, J.M., and L. Hebert. 1989. Control and performance of international joint ventures. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 20: 235–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitley, R. 1999. Firms, institutions and management control: The comparative analysis of coordination and control systems. Account. Organ. Soc. 24: 507–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vélez, M.L., J.M. Sánchez, and C. Álvarez-Dardet. 2008. Management control systems as inter-organizational trust builders in evolving relationships: Evidence from a longitudinal case study. Account. Organ. Soc. 33: 968–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, T.K., and B.S. Teng. 1998. Between trust and control: Developing confidence in partner cooperation in alliances. Acad. Manag. Rev. 23: 491–512. [Google Scholar]

- Makhija, M.V., and U. Ganesh. 1997. The relationship between control and partner learning in learning-related joint ventures. Organ. Sci. 8: 508–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deakin, S., and F. Wilkinson. 1998. Contract law and the economics of interorganizational trust. In Trust within and between Organizations. Edited by C. Lane and R. Bachmann. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, pp. 146–172. [Google Scholar]

- Das, T.K., and B.S. Teng. 2001. Trust, control, and risk in strategic alliances: An integrated framework. Organ. Stud. 22: 251–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewicki, R.J., and C. Brinsfield. 2011. Framing trust: trust as a heuristic. In Framing Matters: Perspectives on Negotiation Research and Practice in Communication. Edited by W.A. Donohue, R.G. Rogan and S. Kaufman. New York, NY, USA: Peter Lang Publishing, pp. 110–135. [Google Scholar]

- Beamish, P.W., and N.C. Lupton. 2009. Managing joint ventures. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 23: 75–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, H., and B. Antoncic. 2003. Network-based research in entrepreneurship: A critical review. J. Bus. Ventur. 18: 165–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slotte-Kock, S., and N. Coviello. 2010. Entrepreneurship research on network processes: A review and ways forward. Entrep. Theory Pract. 34: 31–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollender, L., F.B. Zapkau, and C. Schwens. 2016. SME foreign market entry mode choice and foreign venture performance: The moderating effect of international experience and product adaptation. Int. Bus. Rev. 26: 250–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doz, Y.L., and G. Hamel. 1998. Alliance Advantage: The Art of Creating Value through Partnering. Brighton, MA, USA: Harvard Business Press. [Google Scholar]

- Khanna, T., R. Gulati, and N. Nohria. 1998. The dynamics of learning alliances: Competition, cooperation, and relative scope. Strateg. Manag. J. 19: 193–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulati, R. 1995. Does familiarity breed trust? The implications of repeated ties for contractual choice in alliances. Acad. Manag. J. 38: 85–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaheer, A., B. McEvily, and V. Perrone. 1998. Does trust matter? Exploring the effects of interorganizational and interpersonal trust on performance. Organ. Sci. 9: 141–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhok, A. 2006. How much does ownership really matter? Equity and trust relations in joint venture relationships. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 37: 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, C.J., and K.G. Smith. 2006. Knowledge exchange and combination: The role of human resource practices in the performance of high-technology firms. Acad. Manag. J. 49: 544–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, D.A., D.M. McCutcheon, F.I. Stuart, and H. Kerwood. 2004. Effects of supplier trust on performance of cooperative supplier relationships. J. Oper. Manag. 22: 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.D. 2002. Contract, cooperation, and performance in international joint ventures. Strateg. Manag. J. 23: 903–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, J.B., J.L. Johnson, and T. Sakano. 1995. Japanese and local partner commitment to IJVs: Psychological consequences of outcomes and investments in the IJV relationship. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 26: 91–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, A.M., and B. Gray. 1994. Bargaining power, management control, and performance in United States-China joint ventures: A comparative case study. Acad. Manag. J. 37: 1478–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, A., and B. Gray. 2001. Antecedents and effects of parent control in international joint ventures. J. Manag. Stud. 38: 393–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyer, J.H., and W. Chu. 2003. The role of trustworthiness in reducing transaction costs and improving performance: Empirical evidence from the United States, Japan, and Korea. Organ. Sci. 14: 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, R., X. Martin, and N.G. Noorderhaven. 2006. When does trust matter to alliance performance? Acad. Manag. J. 49: 894–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puranam, P., and B.S. Vanneste. 2009. Trust and governance: Untangling a tangled web. Acad. Manag. Rev. 34: 11–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erramilli, M.K., S. Agarwal, and C.S. Dev. 2002. Choice between non-equity entry modes: An organizational capability perspective. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 33: 223–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E., and R.L. Oliver. 1987. Perspectives on behavior-based versus outcome-based salesforce control systems. J. Mark. 1: 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killing, J.P. 1982. How to make a global joint venture work. Harv. Bus. Rev. 60: 120–127. [Google Scholar]

- Aulakh, P.S., and E.F. Gencturk. 2000. International principal–agent relationships: Control, governance and performance. Ind. Mark. Manag. 29: 521–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pangarkar, N., and S. Klein. 2004. The impact of control on international joint venture performance: A contingency approach. J. Int. Mark. 12: 86–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terpend, R., and B. Ashenbaum. 2012. The intersection of power, trust and supplier network size: Implications for supplier performance. J. Supply Chain Manag. 48: 52–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calantone, R.J., S.T. Cavusgil, and Y. Zhao. 2002. Learning orientation, firm innovation capability, and firm performance. Ind. Mark. Manag. 31: 515–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coviello, N.E. 2006. The network dynamics of international new ventures. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 37: 713–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, S.F., and J.C. Narver. 1995. Market orientation and the learning organization. J. Mark. 1: 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.J. 1995. International expansion strategy of Japanese firms: Capability building through sequential entry. Acad. Manag. J. 38: 383–407. [Google Scholar]

- Hennart, J.F., and Y.R. Park. 1994. Location, governance, and strategic determinants of Japanese manufacturing investment in the United States. Strateg. Manag. J. 15: 419–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogut, B., and S.J. Chang. 1991. Technological capabilities and Japanese foreign direct investment in the United States. Rev. Econ. Stat. 1: 401–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C. 1990. The experience effect and foreign direct investment. Weltwirtsch. Arch. 126: 560–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levitt, B., and J.G. March. 1988. Organizational learning. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1: 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ring, P.S., and A.H. Van de Ven. 1992. Structuring cooperative relationships between organizations. Strateg. Manag. J. 13: 483–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdu-Jover, A.J., J.F. Llorens-Montes, and V.J. Garcia-Morales. 2005. Flexibility, fit and innovative capacity: An empirical examination. Int. J. Technol. Manag. 30: 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, J.S., and T.S. Overton. 1977. Estimating nonresponse bias in mail surveys. J. Mark. Res. 1: 396–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poppo, L., K.Z. Zhou, and S. Ryu. 2008. Alternative origins to interorganizational trust: An interdependence perspective on the shadow of the past and the shadow of the future. Organ. Sci. 19: 39–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M., S.B. MacKenzie, N.P. Podsakoff, and J.Y. Lee. 2003. The mismeasure of man (agement) and its implications for leadership research. Leadersh. Q. 14: 615–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M., and D.W. Organ. 1986. Self-reports in organizational research: Problems and prospects. J. Manag. 12: 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvis, C., S. MacKenzie, and P. Podsakoff. 2003. A critical review of construct indicators and measurement model misspecification in marketing and consumer research. J. Consum. Res. 30: 199–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E. 1990. Two firms, one frontier: On assessing joint venture performance. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 31: 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Ambrose, M., R.L. Hess, and S. Ganesan. 2007. The relationship between justice and attitudes: An examination of justice effects on event and system-related attitudes. Organ. Behav. Hum. Dec. 103: 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C., and D.F. Larcker. 1981. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1: 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P., and H. Baumgartner. 1994. The evaluation of structural equation models and hypotheses testing. In Principles of Marketing Researc. Edited by R.P. Bagozzi. Cambridge, UK: Blackwell Publishers, pp. 36–422. [Google Scholar]

- Doney, P.M., and J.P. Cannon. 1997. An examination of the nature of trust in buyer-seller relationships. J. Mark. 1: 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenney, J.F., and E.S. Keeping. 1962. Linear Regression and Correlation. In Mathematics of Statistics, Pt. 1, 3rd ed. Princeton, NJ, USA: Van Nostrand, Chapter 15. pp. 252–285. [Google Scholar]

- Ghoshal, S., and P. Moran. 1996. Bad for practice: A critique of the transaction cost theory. Acad. Manag. Rev. 21: 13–47. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, P.J., and C. Warhurst. 1998. Workplaces of the Future. Basingstoke, UK: Macmillan Business. [Google Scholar]

- Castelfranchi, C., and R. Falcone. 2000. Trust and control: A dialectic link. Appl. Artif. Intell. 14: 799–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, A.C., and K. Bijlsma-Frankema. 2007. Trust and control interrelations new perspectives on the trust—Control nexus. Group Organ. Manag. 32: 392–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fryxell, G.E., R.S. Dooley, and M. Vryza. 2002. After the ink dries: The interaction of trust and control in US-based international joint ventures. J. Manag. Stud. 39: 865–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachmann, R. 2001. Trust, power and control in trans-organizational relations. Organ. Stud. 22: 337–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mean | S.d. | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Performance | 2.07 | 0.81 | 1.00 | |||||

| 2. Trust | 1.41 | 0.52 | 0.31 ** | 1.00 | ||||

| 3. Control | 3.40 | 0.90 | 0.01 | −0.27 ** | 1.00 | |||

| 4. Learning | 1.48 | 0.57 | 0.55 ** | 0.31 ** | −0.05 | 1.00 | ||

| 5. Firm size | 4.88 | 4.10 | 0.31 ** | 0.19 * | 0.03 | 0.09 | 1.00 | |

| 6. Relationship length | 3.59 | 1.33 | 0.40 ** | 0.22 * | 0.06 | 0.23* | 0.10 | 1.00 |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Modes of Foreign Market Entry | Non-Equity Modes of Foreign Market Entry | Cooperative Modes of Foreign Market Entry | Foreign Market Entry via Wholly-Owned Subsidiaries | |

| Controls | ||||

| Firm size | 0.25 ** | 0.15 | 0.13 | 0.29 ** |

| −0.02 | −0.02 | −0.02 | −0.02 | |

| Relationship length | 0.16 * | 0.14 | 0.11 | 0.25 * |

| −0.06 | −0.08 | −0.09 | −0.08 | |

| Explanatory Variables | ||||

| Trust | 0.1 | 0.02 | 0.23 * | 0.12 |

| −0.22 | −0.26 | −0.31 | −0.26 | |

| Control | −0.03 | −0.08 | −0.29 ** | −0.16 † |

| −0.07 | −0.08 | −0.11 | −0.08 | |

| Learning | 0.44 ** | 0.52 ** | 0.24 * | 0.42 ** |

| −0.12 | −0.15 | −0.18 | −0.16 | |

| No. of observations | 280 | 109 | 83 | 88 |

| R2 | 0.43 | 0.42 | 0.47 | 0.59 |

| F | 16.78 ** | 10.63 ** | 10.41 ** | 17.93 ** |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Holtgrave, M.; Onay, M. Success through Trust, Control, and Learning? Contrasting the Drivers of SME Performance between Different Modes of Foreign Market Entry. Adm. Sci. 2017, 7, 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci7020009

Holtgrave M, Onay M. Success through Trust, Control, and Learning? Contrasting the Drivers of SME Performance between Different Modes of Foreign Market Entry. Administrative Sciences. 2017; 7(2):9. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci7020009

Chicago/Turabian StyleHoltgrave, Maximilian, and Mert Onay. 2017. "Success through Trust, Control, and Learning? Contrasting the Drivers of SME Performance between Different Modes of Foreign Market Entry" Administrative Sciences 7, no. 2: 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci7020009

APA StyleHoltgrave, M., & Onay, M. (2017). Success through Trust, Control, and Learning? Contrasting the Drivers of SME Performance between Different Modes of Foreign Market Entry. Administrative Sciences, 7(2), 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci7020009