Abstract

This article is concerned with the implications of casual, non-permanent forms of employment that have become a common cultural practice in higher education. It proposes that contractual terms of employment have important implications for women and leadership in higher education, since to pursue leadership, usually one must first gain permanency in an organization, in contractual terms. Based on an autoethnographic study by a female academic in a UK higher education institution, the article illustrates that temporary forms of employment, should they be protracted, can stifle leadership aspirations due to lack of career progression opportunities and lead to a sense of alienation from the target community of practice, and even to personal difficulties, such as feelings of isolation and poor self-esteem. The article discusses theoretical and practical implications for women’s leadership arising from the findings and makes recommendations for improvements in practice in the higher education sector. The findings and recommendations from this study will also be relevant to other organizational contexts where casual or temporary, fixed term, zero-hours non-permanent forms of employment are common.

Keywords:

autoethnography; higher education; women; leadership; identity; habitus; communities of practice 1. Introduction

This autoethnographic study reflects on the challenges which can be associated with short-term or non-permanent contracts of employment that have become an all-too common cultural practice in the world of higher education (HE). These contracts, which are often referred to in the UK as “sessional” (for a specified number of hours over a specified number of weeks), or “zero-hours” (guaranteeing no specific hours work at all) are casual, non-permanent forms of employment, which are typically renewable on a termly or yearly basis. Despite being one of the most highly skilled and prestigious professions, research suggests that currently more than half (54%) of all academic staff and 49% of teaching staff in UK universities are employed on some form of insecure, non-permanent contract, 48% of whom are women [1].

This situation is worse in some of the UK’s highest ranking universities. In fact, up to 70% of teaching staff in the UK’s most prestigious “Russell Group” universities are employed in this way (see Appendix A) [2]. It is not possible to determine the proportion that are women as gender-aggregated data are not publicly available. Contractual terms of employment have important implications for women and leadership in HE, since to pursue leadership, usually one must first gain permanency in contractual terms. Therefore, temporary forms of employment, should they be protracted, can lead to a lack of career progression opportunities and a sense of alienation from the target community of practice, and even to personal difficulties, such as feelings of isolation and poor self-esteem [3].

In striking contrast, there is compelling evidence that “smooth” career progression is what best facilitates the path to leadership through a temporal and processual learning process, born of social interaction and personal reflection within the context of the workplace [4]. Kempster [4] explores the details of this process by drawing on an eclectic mix of social and cognitive theories drawn from the fields of sociology and psychology. He focuses particularly on Bandura’s [5] social cognitive learning theory and the socially situated theory of Lave and Wenger [6] and Bourdieu’s theory of habitus [7]. Mead’s theory of interactionism is also of importance [8]. This theory, later re-labelled “symbolic interactionism”, explores in intricate detail the intrapersonal and interpersonal mechanism through which situated or “sociocultural” learning takes place, “sociocultural” being a term used by Aubrey and Riley [9] (p. 172), to refer to situated learning taking place within any specific context.

As Lave and Wenger [6] show though their theory of legitimate peripheral participation (LPP), learning is synonymous with gradually becoming a member of the workplace; career pathways are structured both by observation, modelling [5] and gradual participation in normalized workplace activities [6]. Employees’ habitus is also of importance in this process; that is, their “schemes of perception, thought and action” [7] (p. 14), which have been naturally absorbed through a person’s upbringing and educational experience. An employee’s “familiar world” [7] (p. 18) therefore forms their baseline when entering a new workplace; it influences behavior patterns which are under constant negotiation and adaptation in line with their developing perspective of the new social space. Put simply, perspectives of the social space are subject to change depending on the positioning of the employee: “points of view are grasped as such and related to the positions they occupy in the structure of agents under consideration” [7] (p. 15). As employees participate from their peripheral outposts, gradually moving towards the center of the community of practice, they begin to interact with, absorb and embody the prevailing culture at a deeper level, reinforcing and reproducing its social structures as they go along [7]. To those who are less fortunate, an alternative construction of reality may apply.

It seems logical therefore that if the required sociocultural affordances are not in place, career development opportunities will not naturally occur. This is especially the case in HE institutions due to the precarious contractual terms through which many academics are employed. The discriminatory legacy of prolonged periods of poor contractual conditions can negatively impact on an affected individual’s access to leadership roles. Such a situation can also ultimately lead to a desire to dis-identify with the target community of practice, willfully rejecting, in fact, a sociocultural infrastructure which is of crucial importance for generating career opportunities.

This paper explores the lived experience of one female academic at a UK HE institution through autoethnography. Autoethnographers, by drawing on ‘the “lived realities” of their own organizations’ offer insights into ‘what “really” goes on in organizations’ [10] (pp. 167–168). In this way, an insider can articulate her own personal and lived experiences, analyzing them in the light of their perceived social and theoretical context both to make greater sense of herself and to add value to the theoretical understanding of the social world under investigation [11]. Burnier [12] (p. 414) argues that “autoethnographic writing is both personal and scholarly, both evocative and analytical, and it is both descriptive and theoretical when it is done well”. This paper will bring to life the consequences of losing an expected career trajectory because of repeated, long-term non-permanent (sessional) contracts and the gradual process of learning to lead in a context where permanency, stability and belonging seem like a distant dream. The paper seeks to contribute to a small but growing body of literature on women and leadership in HE by highlighting the implications of poor contractual terms of employment. Its secondary aim is to reach out to women and men for whom this situation may resonate and help them to make sense of their own lived experience. It is also hoped that this will contribute in some way to an awakening of HE decision-makers to the implications of current contractual practices.

The theoretical framework for the paper is drawn from Kempster’s [4] theories of leadership learning as situated practice, which is underpinned by Lave and Wenger’s [6] theories of peripheral and legitimate participation in communities of practice and Bourdieu’s [7] theories of habitus, field, and symbolic power. The linkages between these theories and how they inform us of leadership learning is discussed in the literature review that follows. Next, we expand on the autoethnographic approach, before sharing that narration, then we discuss further insights that have arisen through sharing this autoethnography with a senior manager of the autoethnographer. This is followed by a discussion and conclusions concerning the theoretical and practice implications of the article.

2. Theoretical Framework

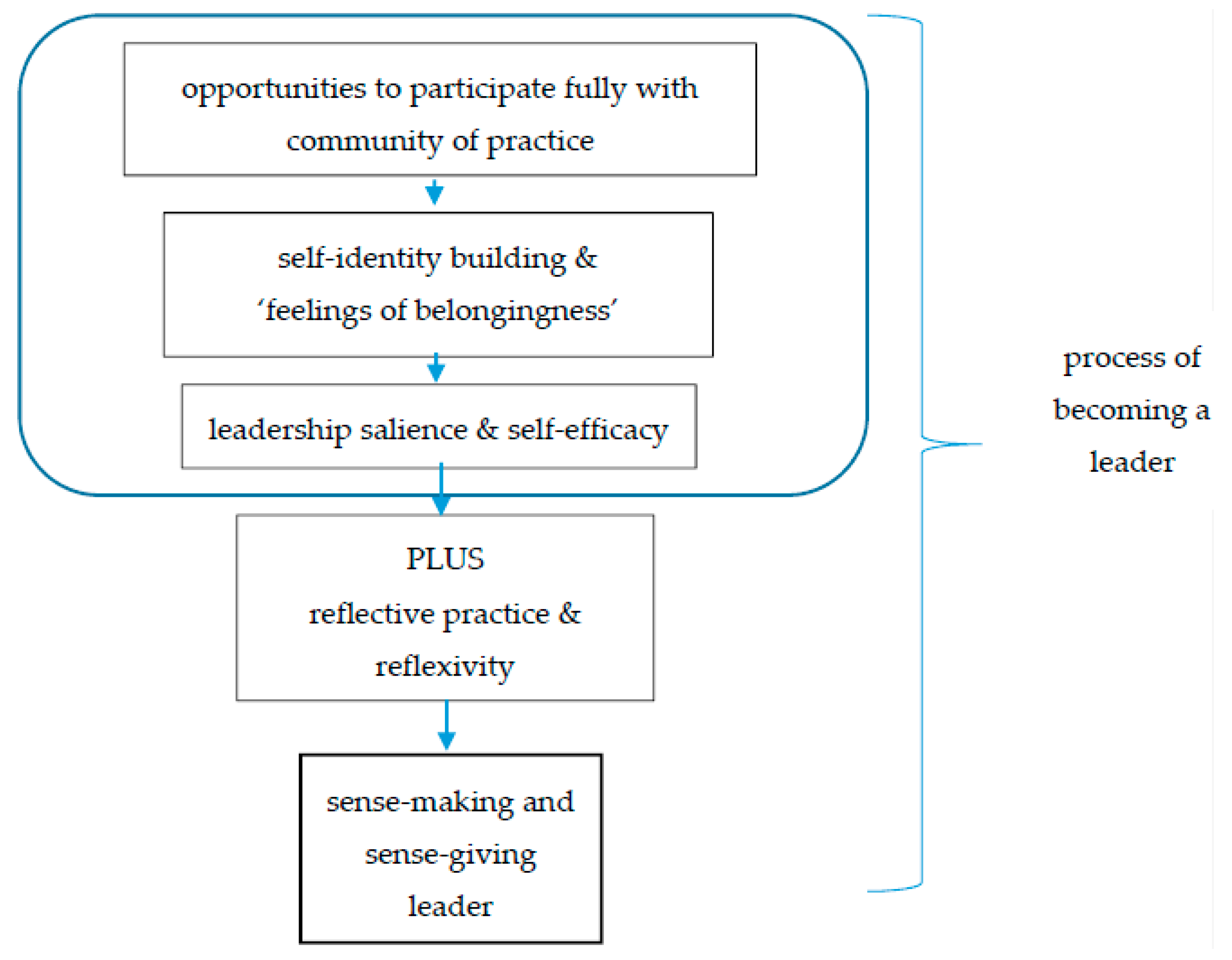

Kempster’s [4] view of how employees learn to lead is represented in outline form in Figure 1 above. The following discussion explores in greater detail the three prominent theories (briefly outlined previously), that interlink and underpin this model of leadership learning. First, Lave and Wenger’s [6] theory of legitimate peripheral participation posits that as newcomers on the periphery of a community are encouraged to participate in work-place activities, they undergo an ontological transformation; a person gradually develops work identities through a process of “becoming”, synonymous with moving to a place of full participation within the community [13] (p. 154). This “smooth” transformation can only take place if there is no persistent disconnect between what the employee does and how she perceives herself to be located in relation to others within her community [3] (p. 273). This means that successful career progression within an organization relies on “feelings of belongingness” which promote opportunities for personal success and growth in self-confidence. Such successful participation increases levels of leadership salience and self-efficacy, which are both prerequisites for a successful “sense-making” and “sense-giving” leader [4] (p. 30).

Figure 1.

Process of becoming a leader (adapted from Kempster [4]).

2.1. Learning Through the Workplace Context

Second, Kempster’s [4] promotion of Bandura’s [5] social learning theory—that employees learn through leadership experiences via the modelling process must also be viewed within the context of LPP. Lave and Wenger [6] (p. 95) point out that ‘LPP provides [learners] with more than just an “observational” lookout post: it crucially involves participation as a way of learning’. Through the process of participation, actors observe the behavior of salient others within the social context and imitate this behavior as desired and as the opportunity presents itself. This process is promoted through the opportunity to observe a variety of notable people, and through having a career-structured pathway which enables the enactment of different behavior patterns and the receiving of feedback.

Third, there is Bourdieu’s [7] (p. 17) notion of habitus as “a structuring structure, which organizes practices and the perception of practices”. Although this undoubtedly helps an individual to form a sense of self, it may also imply a certain level of situational determinism, which Bandura [5] rejects. He believes that “people possess the capacity to manage their own thought processes…people can regulate what they think, they can influence how they feel and behave.” [5] (p. 145). His theory therefore bears similarities with symbolic interactionism: a person can view her “self” as an object, as if through the eyes of others, and make decisions about how to react to others’ actions on the basis of the interpretation given to them [14] (p. 79). In this way, the actor has the power to exert cognitive control over the process of social learning. She has the freedom to make decisions stemming from her modelling practice according to her own self-identity. Such self-identity can be explained as a combination of self-concept and social identity [15]; “self-concept” being a “fairly stable picture we have of ourselves” [14] (p. 82), and “social identity” referring to the afore-mentioned ability to judge our positionality through the eyes of others within a particular social context [14] (p. 82).

Through this account of learning to lead through the workplace context, it can be intuitively understood that if participatory opportunities are perceived as permanently presenting themselves only in a haphazard way, leading to a view of role-modelling as a sterile practice, employees (typically female on non-permanent contracts) may begin to distrust workplace culture, and forge an independent track in order to build their identity in another way. Another possible outcome is that of persistence in building an identity which submits, at least publicly, to the norms of the workplace culture, until such time as new opportunities open up later in life. Lack of opportunity to become a full member of a community of practice due to ongoing short-term contracts must be one of the crucial elements in understanding why women do not progress as they might have expected in their careers, and are indeed consistently under-represented at HE management and leadership level [16].

2.2. Understanding the Workplace Context

According to Kempster [4], an engagement with “context and social structures” lies at heart of career progression practice. Such “structures” are embedded practices of a workplace [4] (p. 189), which have been historically set up and are further developed by humans. Bourdieu [7] believes that social practice within an organization is often viewed objectively but that it can also be viewed subjectively. For example, an updated health and safety rule book can be viewed both as a social object, and as a body of work that an administrator, tacitly colluding with the socio-cultural context, has produced, thereby choosing to preserve and reinforce current practice; in other words, the habitus of the administrator publicly acknowledges that this task is appropriate for her, so she undertakes it accordingly. She knows that her ongoing membership of the community of practice relies on “ongoing engagement with the dominant traditions” [3] (p. 283). Privately, however, her sense of self may tell her that her abilities lie far beyond this particular task, and she may resent carrying this out, but her awareness of her social identity precludes any refusal. This accounts for why an employee of low social status is less likely to challenge a particular socio-cultural norm than an employee with higher social status, who in her turn is more likely to uphold the status quo due to the influence of those agents who have invested power in her [17]. An employee who persistently works on a short-term contract does not give objective voice to her subjective thoughts; complaint may risk non-renewal of such a contract. In this way, a workplace norm is embodied within the human experience; social order is maintained and cultural practice is reproduced.

2.3. The Role of Reflection

As has been shown in Section 2.1, identity development requires both tacit and self-conscious iterative reflection; everyday social objects may indeed be subconsciously accepted and morphed into routines [4,17], or they may lead to more conscious reflective behavior [4]. Bennis and Thomas [18] point out that this is more likely to occur when social objects are particularly emotional or novel, such as good and bad boss experiences. They term such memories as crucibles, which often lead to a high level of intrapersonal reflection and a renewal of self-identity. In such cases, the self is an object to “act back on” [14] (p. 93); the thinking process is carried out in a more self-conscious, reflective fashion. Such incidents may even promote periods of reflexivity—the process of deeply reviewing and reflecting on one’s own deeply-engrained habitus. In this way, new and existing employees interact with the intra- and inter-personal environment to effectively decide on their position [14]. This process can prompt an individual to ask questions of themselves such as: Who am I? Why aren’t I being who I want to be? How can I be happy in the working world? These uncomfortable and unsettling questions ultimately equip an individual with the personal resources that promote a sense of self-concept and self-knowledge, self-concordance (the development of goals consistent with the self-concept), and person-role merger, which promotes a sense of authenticity [19].

Women typically are more likely to interrogate the value of an identity as an HE manager or leader than men [16]. This may be because HE socio-cultural practice is currently motivated by educational capitalism; universities need to become competitive, profit-making institutions with leaders who collude with “new managerialist” principles; they need to be competitive, entrepreneurialist and aware of their self-image [20]. New managerialist approaches may also include the requirement to implement unpopular re-structuring and redundancy policies in the interests of efficiency or to monitor their employees more closely. While such new managerial posts offered are not gender-specific, Deem [16] concludes that women are more interested in roles which seek to improve the student experience and quality of staff/student interaction whereas men are more inclined to see their roles as generating income and guaranteeing research excellence. The fact that men and women tend to have “gender-differentiated criteria for success and failure” [16] (p. 255) rather suggests that women may not even regard it as desirable to operate within a managerial or leadership culture which is at variance with their own concept of self.

3. Materials and Methods

This paper is based on a qualitative study—an autoethnography written by the first author of the paper. Put simply, autoethnography involves insider research into a context in which the researcher has “natural access” and is an active participant [10] (p. 174). Autoethnography is grounded in postmodern philosophy, and it has gained prominence among researchers in recent years. Predominantly, this rise in interest in autoethnography is related to a growing debate about reflexivity and voice in social research [21]. As Burnier [12] notes, autoethnography, along with other alternative forms of ethnographic research has gained prominence in response to a critique and “crisis” of how people, places, and practices come to be “represented” in qualitative research (p. 410). Although autoethnography has been criticized for lacking rigor, theoretical and analytical quality and for being too aesthetic, emotional, and therapeutic [22,23], Alvesson [10] argues that autoethnography (or self-ethnography as he calls it), is an ambitious and legitimate alternative to solely or mainly relying on interviews with respondents. It offers researchers a flexible and fluid form of academic writing [24] and, importantly, it can be emancipatory, especially for researchers who have lesser power and/or are a minority group in their field or practice context [21]. It has proved fruitful in contributing to organizational research [25], including university settings [26].

Autoethnography can take many forms; most relevant to this study is analytic autoethnography, which is comprised of three features, according to Anderson [11]. The researcher is (1) a full member in the research group or setting, (2) visible as such a member in published texts, and (3) committed to developing theoretical understandings of broader social phenomena. This autoethnography meets that criteria since it is written in the form of a personal narrative by the first author of this article, and it seeks to make both theoretical and practical contributions. In line with more general guidelines for authoethnography, this article attempts to present a highly personalized [21], evocative, engaging piece of writing that uses both the conventions of storytelling such as character, scene, and plot development [27], as well as reflections that produce new perspectives [28,29]. The narrative also aims to capture and provide “thick descriptions” of the cultural context [30] (p. 10) and make links to existing literature [31,32].

Ellis et al. [33] provide a detailed account of autoethnography; we draw on this to describe in more detail the methods and materials in our study. In keeping with most autoethnography research our method combines the characteristics of autobiography and ethnography. The autobiographical element involved retroactively and selectively writing about past experiences. A biographical timeline was produced as an aide memoir, following an approach used by Kempster [4]. The time line was populated with significant experiences and notable people. The researcher reflected on this time line to help focus her writing on epiphanies or significant experiences that she perceived to have impacted significantly on her trajectory and life [28,34,35]. This process enabled her to produce detailed written material about aspects of her personal and work life, explored through the normally private prism of accompanying thoughts and emotions. The ethnographic element involved the study of cultural and relational practices, common values and beliefs, and shared experiences for the purpose of helping insiders (cultural members) and outsiders (or cultural strangers) gain an understanding of that culture [36]. Precisely because the researcher was, and remains, an active participant in the study context, she was able to concentrate on her own past and present experience [37] to describe the cultural setting and use her experience and knowledge for research purposes [10]. In consequence, the material for this study came from the researcher drawing on autobiography and ethnography, retrospectively and selectively, to write about epiphanies related to culture and the particular culture and cultural identity of the institutional setting [33]. The method was iterative, and involved moving back and forth between reflection, writing, and the research literature. The method, therefore, involved much more than just story-telling, as Ellis et al. [33] explains:

Autoethnographers must not only use their methodological tools and research literature to analyze experience, but also must consider ways others may experience similar epiphanies; they must use personal experience to illustrate facets of cultural experience, and, in so doing, make characteristics of a culture familiar for insiders and outsiders [online].

3.1. Ethics

It is of note that autoethnographic writing raises unusual ethical considerations [38]. The study upon which this paper is based received full ethical approval of the HE institution. From the onset, following guidelines for autoethnographers [38], both authors of this paper considered and followed ethical guidance, paying particular attention to the vulnerability of the researcher writing the autoethnography and other people who may be implicated through association with the autoethnographer, her department and/or the HE institution, which could result in researcher self-harm. In addition, because most autoethnographers focus on themselves primarily, this may give the impression that conventional ethical issues concerning human participants are not relevant. However, we were mindful of Chang’s [39] (p. 68) argument that this assumption is incorrect:

Whichever format you may take, you still need to keep in mind that other people are always present in self-narratives, either as active participants in the story or as associates in the background.

Even though no other individuals are named in this article, we acknowledge that individuals in the HE institution could be implicated, even though the article is referring predominantly to historical events in the past, and changes in staffing, organizational practices and culture have occurred since that time. Nevertheless, we have worked on the assumption that those people could read the paper [40]; therefore, care has been taken not publish anything we would not show to people referred to in the text [41]. In addition, “process consent” [42] (p. 23) was sought from a senior manager within the department in which the first researcher (the autoethnographer) is located, and that person has read and agreed to the publication of this article.

4. The Autoethnography

4.1. Introduction

I now realize that my working life between 1996 and 2005 involved the same increasing sense of disconnect with my community of practice as has been outlined in Section 2.1 above. My ongoing poor contractual terms, over a time period of nine years, resulted in a feeling that I did not belong; as a result, my participation never felt as if it was important. I was not a member, I did not undergo any desirable ontological transformation, nor was I able to absorb and truly identify with the prevailing socio-cultural context. As Linehan and McCarthy [43] warn, an employee who finds that the access route to a community of practice is blocked often find another way to re-invent their identities; indeed, through my reading of Hodges [3], I have become aware that this was exactly what I did. Since 1996, I have become “a person [who]…reject[ed] the identity connected with the practice and yet…reconstruct[ed] an identification within the context of conflict and exclusion” [3] (p. 273).

In order to explore this notion of dis-identification and reconstruction, my personal story will be uncovered as it relates to salient literature in the field. I will own this process by re-examining past events from varying perspectives, learning more about a particularly challenging period in my practice and continuing to work on resolutions. These biographical snatches will be reflexive; I will query my own personal beliefs and values as a teacher and note how these have affected and been affected by their surrounding context [44]. In this way, I can explore my own educational leadership and management journey and use reflective practice to “explain, justify and make sense of [… myself] in relation to others, and to the world at large” [44] (p. 311).

4.2. Habitus

It seems clear to me that I am comfortable with my habitus, that is, the self-identity built during my years of primary and secondary socialization. Role models within my community of practice were important to me; my parents clearly both valued education and they were both totally undiscriminating towards their children in terms of gender and educational aspirations; the school staff at my girls’ school were overwhelmingly female with high ambitions for their pupils. I used to adore French and hero-worshipped my French teacher. It was during these years that my conviction grew that I would be a French teacher too. I never doubted that I would go to university to study French and then have a fulfilling and “important” job as an academic or a teacher. I was determined to speak French as much as possible, so I used to organize pen-friend exchanges for myself in the holidays, and undertook a variety of voluntary work in France, Germany and Italy in order to speak those languages that I enjoyed studying. I now realize that I was finding ways to legitimately and peripherally participate in new “life-worlds” in order to improve my languages, using them as a device to trial and develop new social identities. After my first degree, I set out on my personal journey to make sense of the world through my self-identity as a languages teacher or academic, “within the structural constraints of my own internalized reality” [7] (p. 18). After further studies and much deliberation, I decided to become a modern languages teacher and gained my first job in a local secondary school.

4.3. Dis-Identification with the Identity Connected with the Practice 1996–2005

Pupil resistance to secondary school language learning through, presumably, an oppositional stance to it learned through their primary socialization [45], and a lack of effective disciplinary support measures within the school resulted in a new lifestyle choice. I chose a teaching path that would be less stressful and allow me to juggle motherhood with a new career identity. I moved into teaching modern foreign languages part-time within the adult education sector, and then in the mid-1990s, when the marketization of higher education had begun to take hold, increasing competition for student fees led to a new climate of organizational change within universities [46]. I gained a further Master’s degree in Teaching English while being employed as an hourly-paid, sessional tutor on an English for Academic Purposes (EAP) program at an HE institution within in the UK. While I was delighted with this new teaching context because of the new experiential opportunities and personal flexibility it afforded, I gradually found that such a temporary and part-time contractual status seemed to consign me to the periphery of the community.

Over these years, the full-time permanent staff became the “master practitioners” of the program [6] (p. 111). Through their various committees and management meetings, to which, as a temporary employee, I was never invited, my perception grew that they were privileged to knowledge-making which set me apart, and they took the program forward, establishing their own identities as central. Condemned to my identity as a perpetual peripheral member of the community, I felt vulnerable with no permanent work contract, taking on new project opportunities that I imagined I had only obtained because others had not found them appealing, teetering between an attitude of “submissive imitation” [6] (p. 116), and naïve acceptance, hoping that my hard work would eventually encourage ever closer involvement with the community of practice. However, I always felt that as a part-time, temporary teacher, I was considered too light-weight to be taken seriously. Over the next nine years, the increasingly corporate culture began to infiltrate my professional identity, which was gradually eroded. I felt infantilized; meetings seemed to be a sounding-board for those in power; I felt that my contributions were worthless, embarrassing and wrong; I felt paralyzed to act according to my own professional judgement. When I read Gabriel’s [47] account of how contemporary corporate and marketized organizations can exert insidious emotional control over their staff, I was stunned to realize that this represented an exact account of what I had lived through.

Even if an individual has nothing to confess, the transformation of the workplace into a confessional, with the implicit acceptance that there are right and wrong attitudes, appropriate and inappropriate behaviors, measurable performances, etc., and that the individual must continuously monitor him/herself against such standards, created pliable, self-policing, self-disciplining individuals, who lack the words (or discursive resources) to oppose or shake off the invasive tyranny of power/knowledge[47] (p. 187).

Such controls did not just lower my sense of self-esteem, but they eroded my very sense of self, together with my other personal identities. My cultural life at my place at work excluded me from its heritage—symbols of inclusion passed me by [6]; for example, I was overlooked in the distribution of circulars advertising future conferences, I was ineligible for annual performance reviews, I was not considered to be at a high enough grade for a personal business card, nor was I entitled to an individual post tray in the staff room.

I remember that I often used to think when I came home from work: “how can I possibly be a responsible wife and mother when I am obviously such an incapable and hopeless individual?”. On one occasion, which turned out to be a crucible moment in my decision to leave, I remember that a manager had asked me to help to clear out a book cupboard, and I just managed to stop myself from asking the banal question “how would you like me to clear the books off the shelf?”

Needless to say, I felt excluded from this community of practice, but I desperately wanted to belong. This process of marginalization finally resulted in a dis-identification with this community of practitioners; I became increasingly resentful and hostile as two unsuccessful applications for a full-time post at my HE institution came and went. I took this as a sign. I made the decision to leave the program, and indeed the institution, to take up a job abroad. If I needed any further confirmation that I was not considered part of the community of practice, the last one finally came when there was no customary “leaving party”, presumably because I did not have a “proper” post to leave behind! My new post involved teaching, setting up courses, developing in-service training sessions and supporting and observing teachers. After one year, my self-esteem finally re-surfacing, I returned home to the UK, keen to find a new working context which better suited my new, more comfortable concept of self.

With hindsight, I am now able to contemplate these difficulties and try to make further sense of them. According to Bourdieu and Wacquant [48], the EAP Program had been a social field, where participants struggled either to ensure that their position in the field remained exclusive, or alternatively as an outsider, to develop an acceptable position within it. The prevailing doxa, that is the unwritten rules of the field, had been developed by a hegemony; their chosen social structures becoming “instruments of domination” [48] (p. 14). Full-time workers had economic capital due to their permanent posts, cultural capital in that they were privy to the inner workings of the program, and social capital, as their positions enabled the development of self-serving relationships, leading to ever more influential positions as they rose up through the ranks. As a result, they had high symbolic capital, which they were able to maintain through their hegemonic practice. As a constantly temporarily-working “mother”, I felt that I had low economic capital in terms of my low earnings and inexistent terms and conditions, little cultural capital (being excluded from day-to-day organizational practices), low social capital as I had few legitimate participatory opportunities at the heart of the hierarchy, and probable low symbolic capital as a woman [16]. In short, the “academic staff” (as they were termed) seemed to enjoy much higher symbolic capital than myself, who was in fact in contrast constantly referred to as a “sessional”. This “symbolic violence” [7] (p. 21) was exercised over me, due to my vulnerability within the field, and I succumbed to this for years, accepting my position (albeit unwillingly), through a need to earn money and an inability to change the cultural context. My self-identity was clearly too strong to accept the social identity that my colleagues were positing for me; it was at variance with my self-concept, and I had to take action. “Resistance through physical distance” became my solution [47] (p. 192). As Spitzer [49] (p. 16) points out, “a fixed mindset”, (which, on reflection, I had unwittingly acquired through my habitus) “tends to be self-evaluative: I’m smart or dumb, creative or unimaginative, a success or a failure”. My earlier academic success had taught me that I was special, that I deserved to succeed, and somehow this painful experience had re-defined me as a failure.

While simultaneously criticizing myself for my “fixed” mindset, rather than viewing such challenges as opportunities for growth [50], my self-destructive experience with trying to move in a centripetal direction accords with other research into the role of women as leaders in HE. Morley [51] (p. 119) shows how many women ultimately view leadership in terms of a “loss”, and Kempster’s [4] research shows how women’s domestic identities prejudice their opportunities for career challenge, leading to a lack of confidence. Kempster [4] (p. 153) notes in his research: “Only the women made explicit the connection of the role of confidence and the activities to maintain confidence. This does not mean that men were never unconfident—simply that they did not emphasize or highlight this issue” [4] (p. 153). Might this be because men’s typical career trajectories do not tend to challenge a fixed mindset, whereas women’s do? Is it likely that some women are not supported in breaking through their fixed mindset, never learning that “failure […] doesn’t define you. It’s a problem to be faced, dealt with, and learned from” [50] (p. 33)?

4.4. Reconstructing an Identity within the Context of Conflict and Exclusion (Post-2005)

On returning home, I was again offered hourly-paid work at the same institution, within a different EAP Program. The program I had left represented a need for conformity, requiring a consistent approach to course design and delivery in order to ensure the students attending all received an equal opportunity in the high stakes assessment required for them to progress to their chosen degree programs. Now appointed to a different program, which was still being established and not such high stakes for the students, there was more flexibility in course design and delivery, and indeed specificity at course level was encouraged. In these early years, all the staff were hourly paid, the socio-cultural context was welcoming, relaxed but hard-working—we jointly had opportunities to set up new courses, manage them and develop materials. In this way, power was equally distributed between us, despite our poor contractual conditions. I was struck by the respect we had for each other, conducting our own meetings without “game playing, politicking […] clashing of antlers, proliferation and waffling” (Female HoD, cited in Deem [16] (p. 251)).

In 2010, our language center became subject to new HR regulations, and all those who had been working for more than three years on a sessional, temporary contract were offered permanent posts with full rights. I was offered a permanent part-time contract with certain middle-management responsibilities. I had “arrived” at the age of 55! Being finally content at work, I made a conscious decision to not aspire to any higher management positions; I rejected more senior positions as a career possibility, partly to avoid further loss of self-esteem should I be unsuccessful, and partly because I needed at all costs to create space for myself to prioritize my own values [52]. I have now realized it was my perceived lack of membership of the community which had alienated me, and that this had been due to prevailing HE cultural practice rather than to individual behavior choices; the notion of leadership as an inclusive “sense-making” process Kempster [4] (p. 30) only prevails when community participants all truly belong. I have learned to be content with being a full member of my current community of practice. I now view leadership in terms of “loss”; that is, “loss of independence, research time, health and well-being” [51] (p. 119), and as “a normative fantasy about what constitutes success” [51] (p. 125).

4.5. Working on Resolutions

In preparing this material for publication, I felt troubled by the fact that it was certainly not my intention to secretively expose the management practices of any particular persons. I currently owe a great deal to my place of work in terms of self-fulfillment: I feel passionate about my current role; I am a full member of my current community of practice. I also have the freedom to engage in scholarship to the extent that it improves and develops our current courses. My intention, in fact, is to give voice to a phenomenon that is, for understandable reasons, rarely discussed. Not wanting to appear deceitful, I therefore took the seemingly reckless step of revealing the years of private turmoil that I had lived through to a senior manager who had been present throughout those years in my workplace. After sharing a copy of the paper with them, I arranged for us to meet face to face; the resulting discussion astonished me. With full permission and encouragement, I now present their perspective on my story. I have chosen to use the plural “they” to refer to the senior manager in order to protect anonymity.

The years between 1996 and 2005 had made seminal contribution to the gradually emerging identity of the field of EAP within the HE sector. From a management perspective, raising the EAP profile within the institution to secure understanding of the value of the work for international students and the resource to develop and expand its programs had been difficult and protracted. During this period of growth and development, new staff were employed on temporary contracts. The senior manager had always ensured that my contract was re-issued annually without any breaks between contracts in order to mitigate the disadvantages associated with variable working hours and lack of permanent status. Furthermore, significant experiences discussed herein were viewed from a strikingly different perspective to mine. It transpires that I had always been viewed as a permanent, valued member of staff within my department, even though my contract had been renewable and my working hours had varied from term to term. I was told that I had not been offered a traditional leaving party at the start of my year of my absence because the senior manager had taken the view that I was happily taking a year out to enjoy an overseas opportunity and was expected to be returning to my job! She had no memory of the lack of participation in the symbols of inclusion mentioned previously, simply asking why I had not been to discuss my concerns with them at the time. My reply that I had felt too vulnerable in my position seemed to amaze them; they felt we had had a good working relationship and that I could easily have approached them. They had never considered me as “temporary”—sessional staff members were relied on to enable the department to grow and were important for developing the business to a point where permanent contracts could be offered more widely. They explained that I had not been invited to certain decision-making meetings and committees as I did not manage staff or other departmental resources, and this was viewed as a simple fact of university life—not everyone can attend higher-level meetings. Moreover, they pointed out that at such meetings consensus is rare, as individuals do not necessarily agree on management decisions; not everyone’s view can be acted upon, and compromises have to be made. They pointed out that other staff in a similar position to me at that time had appeared less daunted by this situation and had pushed through with their onwards career trajectory, a point which was in fact true.

These differing accounts of the same event reveal the pertinence of Bourdieu’s statement, previously discussed, but worth repeating to allow for further consideration: “points of view are grasped as such and related to the positions they occupy in the structure of agents under consideration” [7] (p. 15). The senior manager’s perspective and my own view of the socio-cultural context were colored by our own positions in the structure within which we operated; through our unfortunate lack of discussion, neither of us was in fact party to the fuller picture, and both of us had objectified our own view of the world as we saw it. We jointly realized that we could draw thoughtful conclusions from our stories which may be pertinent for both employees and their managers/leaders in HE.

5. Findings

This autoethnographic study set out to reflect on the challenges of short term or non-permanent contracts of employment in HE. Although the findings are based solely on the experience of one woman, we propose, from a theoretical perspective, that the findings tentatively extend Kempster’s [4] own research results. Kempster [4,53] has shown that the salience of a leadership identity and its accompanying self-efficacy typically increase through privileged access to notable people and opportunities to practice leadership within communities of practice. The findings of this paper confirm what Kempster [53] has speculated—the salience of leadership diminishes in environments that fail to provide pathways for participation in leadership.

Further, the findings exemplify that participation-in-practice is associated with “becoming” part of a social world [6]. Through the use of autoethnography, this article highlights that employees who would like permanent status but are employed on temporary contracts may feel disconnected from their community of practice [6], to the extent that an employee can become vulnerable and marginalized. As a result, their subjective, emotional reaction may preclude a measured consideration of the social structures of the workplace; their objective view of the workplace may gradually harden over the years, particularly if their mindset is fixed [50], a notion explored in this paper. Limited opportunities for participation can therefore cause an individual to dis-identify with the community of practice and over time they may adopt a workplace habitus which secretly resents the prevailing social culture. Such experiences can stifle an individual’s aspirations to become a leader and their self-efficacy beliefs, resulting in the rejection of a leader identity and/or leadership positions.

6. Conclusions

It is to be hoped that the theoretical insights and reflexive approach afforded by this autoethnography and its final discussion will help both temporary employees and their managers to better understand how the context of their workplace can seem to disadvantage a temporary worker, whose workplace behavior may belie their inner concept of self. It is important to acknowledge that men, not just women, may reject managerialist values, and indeed there are many women in leadership who may even espouse them. For myself, I have discovered the truth of Wall’s belief [21], previously highlighted in Section 3, that an autoethnographic approach can be emancipatory; lifting the lid on this rather frustrating period of my life has been a therapeutic process; both my own research and subsequent frank discussions have finally laid to rest a cycle of lack of confidence and low self-esteem.

Since this study is based on one woman’s experience, we recognize its limitations and we hope this paper will inspire others in similar situations to analyze and tell their stories, individually or though collaborative autoethnography, both to search for personal resolutions and to help to influence future directions of HE working practices, which should be more forward-looking, creative, less wasteful of potential talent and more representative of the diverse nature of a changing society.

7. Recommendations

We propose practical recommendations based on the findings of this study:

Firstly, the level of vulnerability that I had felt over the years had for me precluded frank discussion, but the senior manager had not in fact regarded my position as vulnerable at all; in her mind, there was no doubt that I would be re-employed year on year. Managers should not therefore underestimate the “otherness” feelings that can be created by temporary contract working; such employees may not give voice to their feelings, either because they sense that no-one is really interested, or because expressing an adverse opinion may risk their job.

Second, HE organizations, which aim to be vibrant, forward-looking centers of learning, striving for positive change in the world, should carefully consider their current workplace culture, policies and practices; managers should be aware of the symbols of inclusion, however apparently small, that may serve to mark out temporary employees as different [6]. With this in mind, temporary employees should be included in performance development reviews despite their low symbolic status; they should be encouraged to routinely and confidentially discuss their career aspirations as do permanent staff; they should be able to give feedback on the performance of their line manager; someone should take responsibility for ensuring that they are always updated with relevant information and included in the variety of opportunities open to permanent staff. In addition, there should be a budget for paying temporary staff to allow them to attend in-service training sessions without the assumption that they will give their own unpaid time for the privilege of joining in. Socialization into the community of practice [6] could also be facilitated by mentoring or sponsorship schemes, particularly in terms of encouraging women to consider crossing the divide into senior managerial roles which, as discussed in Section 2.3, they may not otherwise instantly find appealing.

Third, further consideration should be given to the fact that working women who may be juggling family and work life have a valuable role to play in the HE sector, and that some may lack confidence after a career break [4]. In consequence, return-to-work support structures should be more widely available, and job shares at a higher level of responsibility should be more positively encouraged, as should the distribution of permanent part-time contracts.

Author Contributions

Karen Jones and Anne Vicary conceived and designed the study; Anne Vicary performed the autoethnography; Karen Jones devised the methods and materials section; Anne Vicary and Karen Jones wrote the remainder of the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Russell Group universities consist of 24 research-intensive, world-class universities based in the UK. These universities are “committed to maintaining the very best research, an outstanding teaching and learning experience and unrivalled links with business and the public sector [54].”

References

- HESA. Staff at Higher Education Providers in the United Kingdom 2015/16. Available online: https://www.hesa.ac.uk/news/19-01-2017/sfr243-staff (accessed on 30 April 2017).

- UCU. Precarious Work in Higher Education: A Snapshot of Insecure Contracts and Institutional Attitudes. Available online: www.ucu_precariouscontract_hereport_apr16.pdf (accessed on 30 April 2017).

- Hodges, D.C. 1998. Participation as dis-identification with/in a community of practice. Mind Cult. Act. 5: 272–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempster, S. 2009. How Managers Have Learnt to Lead: Exploring the Development of Leadership Practice. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. 1997. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control. New York, NY, USA: W.H. Freeman. [Google Scholar]

- Lave, J., and E. Wenger. 1991. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. 1989. Social space and symbolic power. Sociol. Theory 7: 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mead, G.H. 1934. Mind, Self and Society. Chicago, IL, USA: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Aubrey, K., and A. Riley. 2016. Underst anding and Using Educational Theories. Los Angeles, CA, USA: London, UK: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Alvesson, M. 2003. Methodology for close up studies—Struggling with closeness and closure. High. Educ. 46: 167–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, L. 2006. Analytic autoethnography. J. Contemp. Ethnogr. 35: 373–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnier, D. 2006. Encounters with the self in social science research: A political scientist looks at autoethnography. J. Contemp. Ethnogr. 35: 410–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenger, E. 1998. Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Charon, J.M. 1998. Symbolic Interactionism. Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA: Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Ball, D. 1972. Self and identity in the context of deviance: The case of criminal abortion. In Theoretical Perspectives on Deviance. Edited by R.A. Scott and J.D. Douglas. New York, NY, USA: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Deem, R. 2003. Gender, organizational cultures and the practice of manager-academics in UK universities. Gend. Work Organ. 10: 239–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prus, R.C. 1999. Beyond the Power Mystique: Power as Intersubjective Accomplishment. Albany, NY, USA: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bennis, W.G., and R.J. Thomas. 2002. Crucibles of leadership. Harv. Bus. Rev. 80: 39–45. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shamir, B., and G. Eilam. 2005. “What’s your story?” a life-stories approach to authentic leadership development. Leadersh. Q. 16: 395–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackinnon, A., and A. Brooks. 2001. Introduction: Globalisation, academia and change. In Gender and the Restructured University. Edited by A. Brooks and A. Mackinnon. Buckingham, UK: Open University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wall, S. 2006. An autoethnography on learning about autoethnography. Int. J. Qual. Methods 5: 146–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, C. 2009. Revision: Autoethnographic Reflections on Life and Work. Walnut Creek, CA, USA: Left Coast Press. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, E.F. 1995. Reflections on Gender and Science. New Haven, CT, USA: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, C. 2004. The Ethnographic I : A Methodological Novel about Autoethnography. Walnut Creek, CA, USA: AltaMira Press. [Google Scholar]

- Boyle, M., and K. Parry. 2007. Telling the whole story: The case for organizational autoethnography. Cult. Organ. 13: 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, F., J.M. Sancho, A. Creus, and A. Montané. 2010. Becoming university scholars: Inside professional autoethnographies. J. Res. Pract. 6: 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, C., and L. Ellingson. 2000. Qualitative methods. In Encyclopedia of Sociology. Edited by E. Borgatta and R. Montgomery. New York, NY, USA: Macmillan, pp. 2287–2296. [Google Scholar]

- Couser, G.T. 1997. Recovering Bodies: Illness, Disability, and Life-Writing. Madison, WI, USA: University of Wisconsin Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goodall, H.L., Jr. 2000. Writing the New Ethnography. Lanham, MD, USA: AltaMira Press. [Google Scholar]

- Geertz, C. 1973. The Interpretation of Cultures. New York, NY, USA: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Ronai, C.R. 1995. Multiple reflections of child sex abuse: An argument for a layered account. J. Contemp. Ethnogr. 23: 395–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronai, C.R. 1996. My mother is mentally retarded. In Composing Ethnography: Alternative Forms of Qualitative Writing. Edited by C. Ellis and A.P. Bochner. Walnut Creek, CA, USA: Alta Mira, pp. 109–131. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, C., T.E. Adams, and A.P. Bochner. 2011. Autoethnography: An overview. Forum Qual. Soc. Res. 12: 10. Available online: http://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/article/view/1589/3095 (accessed on 30 April 2017).

- Bochner, A.P., and C. Ellis. 2002. Ethnographically Speaking: Autoethnography, Literature, and Aesthetics. Walnut Creek, CA, USA: Oxford, UK: AltaMira. [Google Scholar]

- Denzin, N.K. 1989. Interpretive Biography. Newbury Park, CA, USA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Maso, I. 2001. Phenomenology and ethnography. In Handbook of Ethnography. Edited by P. Atkinson, A. Coffey, S. Delamont, J.L. Lofland and L. Lofland. Thousand Oaks, CA, USA: Sage, pp. 136–144. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz, K. 2006. The power of names. J. Contemp. Ethnogr. 35: 396–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolich, M. 2010. A critique of current practice: Ten foundational guidelines for autoethnographers. Qual. Health Res. 20: 1599–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, H. 2008. Autoethnography as Method. Walnut Creek, CA, USA: Left Coast Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, C. 1995. Emotional and ethical quagmires in returning to the field. J. Contemp. Ethnogr. 24: 68–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medford, K. 2006. Caught with a fake ID: Ethical questions about slippage in autoethnography. Qual. Inq. 12: 853–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, C. 2007. Telling secrets, revealing lives: Relational ethics in research with intimate others. Qual. Inq. 13: 3–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linehan, C., and J. McCarthy. 2000. Positioning in practice: Understanding participation in the social world. J. Theory Soc. Behav. 30: 435–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maclure, M. 1993. Arguing for yourself: Identity as an organising principle in teachers’ jobs and lives. Br. Educ. Res. J. 19: 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, P. 1977. Learning to Labour: How Working Class Kids Get Working Class Jobs. Farnborough, UK: Saxon House. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, R. 2015. The marketisation of higher education: Issues and ironies. New Vistas 1: 4–9. [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel, Y. 1999. Beyond happy families: A critical reevaluation of the control-resistance-identity triangle. Hum. Relat. 52: 179–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P., and L.J.D. Wacquant. 1992. An Invitation to Reflexive Sociology. London, UK: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer, R. 2013. Lighting the fire of innovation: How to foster creativity in the workplace. J. Qual. Particip. 36: 15–18. [Google Scholar]

- Dweck, C. 2016. Self-Theories: Their Role in Motivation, Personality and Development (Essays in Social Psychology). Abingdon, UK: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Morley, L. 2014. Lost leaders: Women in the global academy. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 33: 114–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, P., and B. Jeffrey. 2002. The reconstruction of primary teachers’ identities. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 23: 89–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempster, S. 2009. Observing the invisible. J. Manag. Dev. 28: 439–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell Group. Our Universities. Available online: http://russellgroup.ac.uk/about/our-universities/ (accessed on 30 April 2017).

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).