1. Introduction

Women represent over 54% of the total workforce in the Higher Education (HE) sector in the whole of the UK yet [

1], only 20% of them are in Vice-Chancellor and Principal roles. Only 19% of all HE governing bodies in UK institutions are chaired by women [

2]. This lack of women in leadership roles in HE is not just an issue for the UK but one shared across Europe, where only 15% of rectors (equivalent to vice-chancellor) are women [

3] and indeed across the world [

4]. Lack of gender diversity at the top of Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) has been publicly questioned and the 2015 grant letter from the UK government [

5] stressed the need for the sector to do more to close the gender gap, highlighting that: “

…currently only one Vice-Chancellor in five is female, and we believe the sector should go much further to seek out and harness the diverse talent available”. Moreover, the HEFCE 2015–2020 [

6] business plan has set an aspirational target of 40% women’s representation on universities’ governing bodies to be achieved by 2020 and Scottish universities are aiming to achieve a similar target by 2018 [

7].

In order to achieve these outcomes, HE needs to tackle the “invisible barriers” which prevent women from progressing into senior roles. These include a gendered construction of leadership [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16], the impact of cognitive bias, which results in women being constantly judged less favourably than men [

17,

18,

19] and accumulate disadvantage throughout their career [

20]. Cognitive bias is further reinforced by a persistent male-dominated culture which renders universities” an endemically homosocial gentlemen’s club” [

21] where, by and large, men are most comfortable to work with other men [

22]. These issues are compounded by a gendered division of labour in the academy with women likely to have greater teaching, administrative and pastoral responsibilities, which tend to be less valued than research [

23] and by “gendered academic rules”, for example about evaluation criteria and authorships conventions [

24]. All these factors can lead to what has been described as a “gendered construction of academic excellence” which can “contribute, albeit inadvertently, to institutionalised sexism” [

25].

In this context, it is not surprising that research about the career trajectories of men and women in senior leadership roles in HE in the UK [

26] (p. 13) found that women were more likely to have experienced sex discrimination and gender bias in their careers compared to their male colleagues. Several women reported more recent and subtle examples of gender-bias relating to appointment processes as they tried to move, successfully or unsuccessfully, into more senior leadership roles. For example, some talked about “

huge gender barriers” that still exist in HE, including colleagues and decision makers not seeing them as suited for senior roles and that the very concept of leadership in HEIs is “

too narrowly defined”; failing to acknowledge that there are different models and styles of leadership.

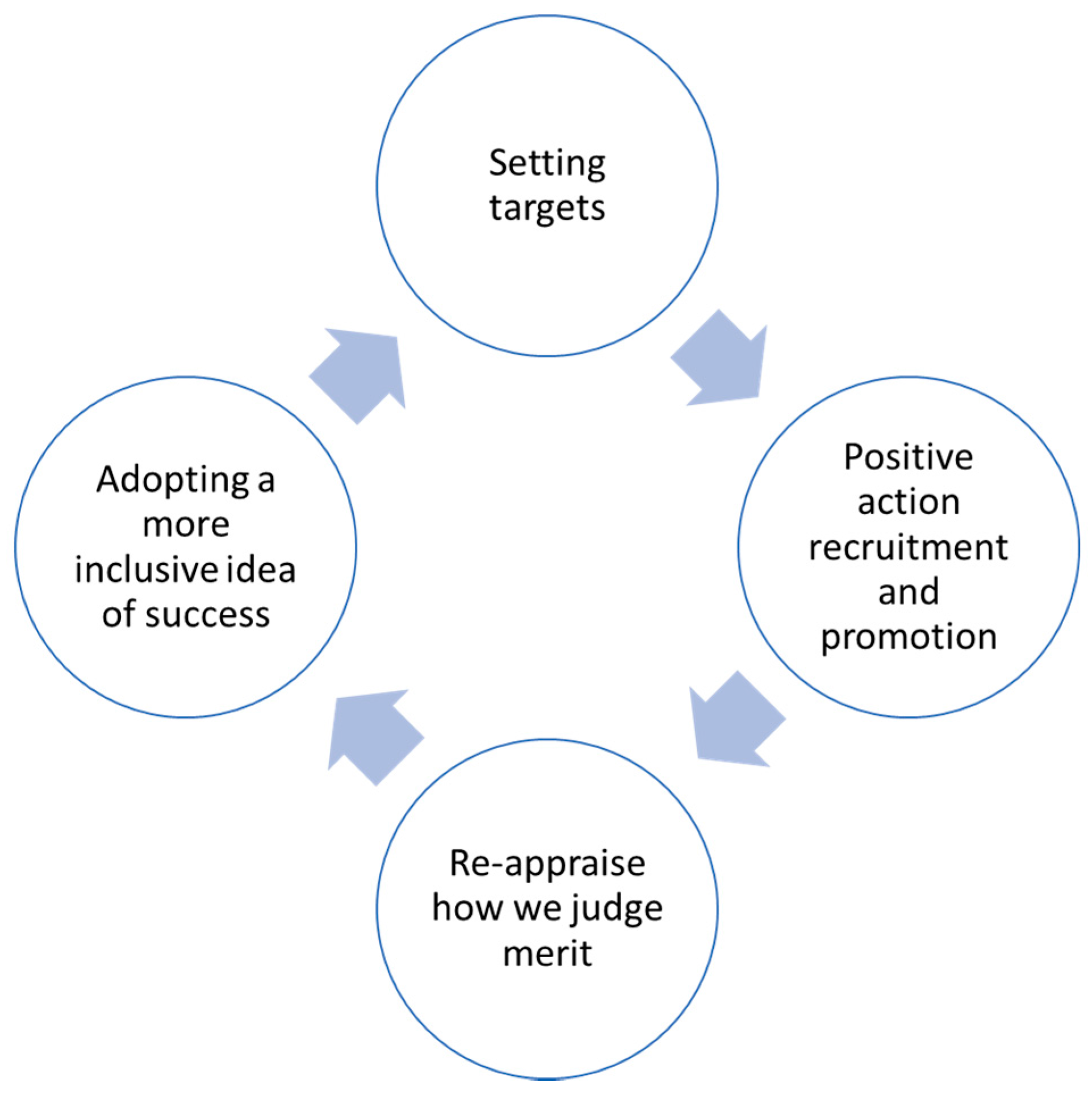

Academic institutions often defend their poor record on gender diversity in senior roles by arguing that appointments are strictly made on the basis of candidates’ merit. This, however, takes us to the very core of the problem about the meaning of merit as this is not a ”value-neutral” concept but one that can be measured according to different parameters [

27]. As seen above, the literature on women’s careers in HE clearly points to a gendered construction of merit and, therefore, there is a need to re-assess merit and unpack gender stereotypes and the norms developed on men’s career experiences which can influence how merit is defined. This article argues that HEIs should adopt positive action in recruitment and promotion as permitted by s. 159 of the UK Equality Act 2010 as a tool to re-assess merit and re-address the gender balance in senior leadership roles. However, positive action legislation in recruitment and promotion that, in a tie-break situation, allows employers to give preference to a candidate from an under-represented group, is poorly understood by decision makers and often considered to be a form of reverse discrimination. As such, it has been too often rejected by both decision makers and the women themselves who could benefit from it.

In what follows, this article draws from literature theorising policy approaches to equality, legal theory on equality and positive action, empirical research about employers’ perceptions of positive action in recruitment and promotion and case law developed by the European Court of Justice to gain a better understanding about the content of this measure and its practical application. It then identifies five objections which are commonly raised against the use of positive action in a tie-break situation and not only seeks to challenge them but also to generate counter-arguments to justify the need for adopting positive action in recruitment and promotion. It concludes by suggesting that there is a compelling case for HEIs to start using this measure and it proposes a model for its application in practice.

2. Positive Action Provisions in the UK Equality Act 2010

The UK Equality Act 2010 contains provisions which allow employers to adopt positive action measures to achieve greater equality. Section 158 provides for general types of positive action measures such as training initiatives to encourage under-represented groups to apply for jobs or promotion. Section 159 instead permits employers to take into account a legally protected characteristic, including gender, when making decisions about recruitment or promotion where the person with the protected characteristic belongs to a disadvantaged or under-represented group. This applies to a tie-break situation in the final stages of the hiring process where remaining candidates are “as qualified as each other”. In this instance, the candidate from the under-represented group may be chosen unless there are objective reasons which would tilt the balance in favour of the other candidate. This type of measure, however, is often seen as a form of reverse discrimination rather than positive action and, as such, it remains controversial.

This raises the question as to whether, in spite of being defined as positive action, s. 159 is in fact reverse discrimination. In order to shed light on this point, Johns et al. [

28] have considered the nature of this provision through the lenses of the theoretical model about policy approaches to equality developed by Forbes [

29]. This distinguishes three key approaches to equality: the formal approach, the liberal and the radical one. The formal approach is predicated onto the Aristotelian proposition that likes should be treated alike and promotes a symmetrical concept of equal treatment. The liberal approach recognises the existence of obstacles that can disadvantage certain groups and aims to remove them, in order to create a level playing field. It is within this liberal framework that the concept of positive action has emerged. The liberal approach that seeks to achieve equality by ensuring equal opportunities among different groups has been most influential in the UK as it sits comfortably with liberal political ideals grounded on the rights of individuals [

30] and also with the free market ideology [

31]. Section 158 on general positive action measures can be located within this approach. However, as highlighted by Johns et al. [

28], s. 159 does not quite fit the liberal approach as this provision is designed to achieve equality of outcomes rather than equality of opportunities. Neither does it fit with the radical approach which aims to achieve equality of outcomes but through radical interventions such as reverse discrimination and the use of quotas. This makes it more difficult for employers to understand the nature of s. 159 and how to use it correctly without risking legal challenges. Although practical guidance has been produced by the UK Government Equalities Office [

32], there is little empirical evidence about the use of positive action in recruitment and selection by employers. A small exploratory study undertaken by Davies [

33] with 26 employers, including some in the HE sector, found that most of them did not envisage making use of this provision. A significant majority, however, expressed personal support for a more interventionist approach to remedy persistent inequalities. Other research focusing on recruitment processes at the senior level in HE [

34] (p. 28) found that, in spite of concerns about women’s under-representation in senior roles, most directors of human resources in universities were against the use of positive action in recruitment and selection. The most common reasons cited by this group were that, in practice, there is always a clear winner or that it overlooks the complexities of choosing a candidate. This is in contrast to the views expressed by a number of Chairs of Universities Councils with experience of working in other sectors, who appeared to be much more open to the idea of using this provision with a few of them having actually used it in the private sector. These findings, although based on small samples of participants and, therefore, not generalisible, nonetheless suggest that senior decision makers have mixed views about the application of this provision and that it may be dismissed by some because it is poorly understood.

Noon [

27] has identified a number of objections which are frequently raised against preferential treatment of under-represented groups in recruitment and selection. This article builds on Noon’s arguments which contest these objections and extends them to develop a compelling argument in favour of this provision.

Five key objections are identified (including those previously highlighted by Noon) which often feature in debates relating to the use of interventions such as that provided by s. 159. These are:

Objection one: That it is trying to remedy to women’s under-representation by using reverse discrimination against men, but “two wrongs” do not make a right;

Objection two: That it undermines meritocracy as decisions about recruitment and promotions have to be made strictly in favour of the best candidate;

Objection three: That the application of positive action in selection and recruitment in practice would be difficult and it could make institutions vulnerable to legal challenges;

Objection four: Women or other under-represented groups want to be appointed to a job because of their merits and not because of positive action

Objection five: That changing the numbers by increasing women’s representation does not guarantee a change in the organisational culture.

These objections will be challenged in turn but prior to this, in order to gain a better understanding of positive action in recruitment and promotion, it is essential to consider the principles that underpin s. 159.

3. Legal Boundaries around the Application of Positive Action in Recruitment and Promotion

Section 159 was introduced to bring UK law in line with European legal developments in relation to the use of positive action measures [

35]. At present, the legal boundaries that define the use of positive action in recruitment and promotion in the UK reflect the parameters developed through the jurisprudence of the European Court of Justice. Although the UK has chosen to exit the European Union, it is still worth considering these parameters, not only because for the time being they still apply, but also because they are well embedded into national legislation. Once the UK has exited the EU and is no longer bound by European law, it could choose to adopt a more radical US style approach to positive action than that currently permitted under European Law. This, however, is an unlikely scenario as it would sit uncomfortably with the UK liberal legal tradition, as discussed earlier. Of course, any UK government could, as with any other legislation, decide to abolish this provision altogether at any time, but this would not be related to the exit from the EU since this provision does not stem from a European Directive. Therefore, there is still merit in discussing the European roots of s. 159.

European Member States are not required to adopt positive action measures but they are allowed to use them to address inequalities if they wish, as stated by Article 157(4) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) which provides that:

“With a view to ensuring full equality in practice between men and women in working life, the principle of equal treatment shall not prevent any Member States from maintaining or adopting measures providing for specific advantages in order to make it easier for the under-represented sex to pursue a vocational activity or to prevent or compensate for disadvantages in professional careers”.

This recognises the limits of anti-discrimination legislation, based on the principle of equal treatment especially in tackling structural forms of discrimination [

36,

37,

38,

39]. This may not be sufficient to tackle what has been described as the second generation of discrimination which, unlike overt discrimination, is caused by cognitive bias, patterns of interaction among different groups in the workplace and power relations which result in more subtle forms of discrimination [

40]. Thus, positive action measures in this respect can be seen as complementary legislative tools to tackle subtle forms of discrimination and to help identify practices which, although on the face it appears to be neutral, in practice can disproportionally disadvantage certain groups and result in indirect discrimination.

In practice, the boundaries of such measures, which represent a derogation from the principle of equal treatment which is enshrined in EU law, have been defined through a series of cases brought before the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU). In these judgments, the Court has established a set of key principles which govern the use of positive action.

The first principle, established in the case of

Kalanke v Freie Hansestadt Bremen [

41], is that the application of an automatic and unconditional measure in recruitment or promotion, which would give preference to a candidate from the under-represented sex in a tie-break situation, would contravene the principle of equal treatment and, therefore, it would not be permitted. In the subsequent case of

Marschall v Land NordrheinWestfalen [

42], however, the Court ruled that it would not be incompatible with the principle of equal treatment to afford preference to a candidate from the under-represented sex in a tie-break situation, provided that both candidates are equally qualified and that all candidates are subject to an individual assessment which would take into account specific circumstances that may tilt the balance in favour of the male candidate.

Two further key principles can be identified from the decision in the case of Marschall: First, while it reinforces the principle already established in Kalanke, that a candidate could not be given preference simply because it belongs to the under-represented sex, it also establishes that if the candidates are equally qualified in relation to the requirements of the job in question, the candidate from the under-represented sex may be given preference. Second it stresses that there must be an individual assessment of both candidates to respect the principle for individual merit. Consequently, preference may not be given to the candidate from the under-represented sex if there are circumstances which tilt the balance in favour of the candidate of the opposite sex. Prima facia these two principles seem to contradict one another, as it could be argued that if two candidates, a man and a woman, appear to be as qualified as each other but there are actual circumstances which tilt the balance in favour of the male candidate, then we would no longer have a tie-break situation, as one candidate would have proven to be more meritorious than the other. This apparent contradiction, however, reflects a tension between, on the one hand, the need to recognise the limits of the principle of equal treatment in achieving gender equality and, on the other hand, the need to preserve the principle of individual merit.

In an attempt to overcome this tension, the CJEU case law has highlighted the need in the application of positive action measures for striking a balance between the aim of achieving greater gender equality and the need to have a process that allows for recognition of individual merit. A key element for this balancing act is the principle of proportionality. This means that a positive action measure should be applied only when this is appropriate and necessary in order to achieve greater representation of people from the under-represented sex, but also that it should be implemented in a way that minimises the disadvantage which would result to people of the opposite sex. For example, in the case

Abrahamsson and Anderson v Fogelqvist [

43], the Swedish government, in order to remedy to women’s under-representation in professorial posts within universities, introduced a rule that gave preference to female candidates. This rule provided that female candidates who had sufficient qualifications for the post would be given preference, even if they were less well qualified compared to candidates of the opposite sex, provided that the difference was not so great that it would compromise objectivity in the making of these appointments. The CJEU ruled that this measure was unlawful because, although increasing women’s numbers in professorial posts where they were significantly under-represented was a legitimate aim, the application of the rule was nonetheless disproportionate in that it infringed the principle of individual merit as it did not provide for any room for an individual assessment of each candidate’s circumstances to take place.

Having examined the legal boundaries around the use of positive action measures established by the CJEU, we now consider more closely the content of s. 159 of the UK 2010 Equality Act.

5. Five Reasons Why Positive Action in Recruitment and Promotion Should Be Used

As outlined earlier, five main objections can be identified which are commonly raised against the use of any form of preferential treatment to increase gender equality in leadership roles and these are discussed and challenged in turn.

Objection one: That it is trying to remedy to women’s under-representation by using reverse discrimination against men, but “two wrongs” do not make a right.

This logic is based on a model of formal equality that understands “equality as sameness” which operates in a symmetrical way by treating like cases alike [

45], as seen earlier. However, the shortcomings of such an approach have been recognised by several legal scholars, including the difficulty of identifying when likes are indeed alike [

45,

46]. Thus, the meaning and purpose of equality has been the subject of extensive debate [

38,

46,

47] which has shifted from a formal understanding of equality to a more substantive one, that “rejects an abstract view of justice and instead insists that justice is only meaningful in its interaction with society” [

48] (p. 235). It is not within the scope of this article to examine all different constructs of substantive equality. However, for the purpose of contesting this objection, it is helpful to focus on a more substantive model of equality which is underpinned by the idea of social inclusion. This model encompasses both the idea that equality should be seen as a means of breaking the cycle of disadvantage suffered by some groups, as well as the idea that all groups in society should be given opportunities to participate in various aspects of civic life, including work [

45,

49]. This focus on social inclusion, as highlighted by Vickers [

50], provides the best theoretical underpinning for a more pro-active approach to equality and to positive action. Therefore, if s. 159 is considered from the perspective of equality and inclusion, the possibility of giving priority to a candidate from an under-represented group in a tie-break situation should be seen both as a way of breaking the cycle of disadvantage as well as a way of ensuring fair participation from different groups. Thus, it is suggested that the use of positive action, far from trying to remedy an injustice with another injustice, should be seen as a tool to correct existing injustice and to ensure that, in the interest of society as a whole, all groups are fairly represented within the different organisational layers of an institution.

Objection two: Positive action measures in recruitment and promotion would undermine meritocracy.

One of the most common objections to the use of positive action in recruitment and promotion is that it would undermine meritocracy and the key principle of appointing the best candidate, regardless of their gender or other characteristics. This kind of objection is underpinned by powerful arguments as exemplified by Pojman [

51] (p. 112) who highlighted that “by giving people what they deserve as individuals rather than as members of groups, we show respect for their inherent worth” and that society can be “better off” if the best people are employed. Most people would agree with these ideas and it is the intention of this article to argue that far from undermining meritocracy the type of positive action measure in question would ensure that meritocracy is truly implemented and that people are given what they deserve and do not miss out because they are members of a disadvantaged group.

First of all, it is important to recognise that meritocracy as a concept has two meanings: a general one and a relative one. The general meaning of meritocracy is informed by the principles of justice and equity which require that everybody should be rewarded according to their talent and achievements which, as highlighted by Pojman, shows respect for an individual’s inherent worth. The second meaning of meritocracy, however, is relative to a particular context and is defined by the way in which the principle that everybody should be rewarded according to their talent and achievements is applied in practice within a particular working context. These are two distinctive meanings which conceptually tend to be conflated. The principles that underpin the general concept of meritocracy are unlikely to be disputed but we ought to recognise that the persistent underrepresentation of women in senior leadership roles, in spite of being employed in large numbers in the HE sector, suggests that either women are not sufficiently talented to progress into leadership roles or that in practice the application of the principle of meritocracy is dysfunctional. The first hypothesis is clearly flawed since, if nothing else, it would run counter to the fact that talent is randomly distributed among men and women. Therefore, the second hypothesis which suggests that the construction and application of the principle of meritocracy in practice is dysfunctional, is more likely to be valid. There are several reasons that can explain such dysfunctionality and they will be examined in turn.

First of all, it is important to note that the definition of merit is not “value neutral” [

27] (p. 743) since it can be measured according to different parameters such as “talent and ability” or “effort and achievements”. Therefore, depending on the parameters which are used and how these relate to prevailing norms of a particular organisation, one person may appear more meritorious than another. Moreover, Thorton [

52] suggests that there are two aspects to the construction of merit: an objective one and a subjective one. The objective aspect relates to verifiable factors such as qualifications, skills, work experience and so on. While the subjective one refers to the actual interpretation of these factors given by decision makers, involved in the recruitment and selection or promotion process. The difficulties with the subjective dimension relating to the interpretation of the actual criteria are well illustrated by a study about professorial promotion practices in HE [

53] (p. 1473). This found that the interpretation of the criteria is “often characterised by confusion and contradiction” and that it can end up being “the perfect breeding grounds” for institutional micropolitics where “manipulation” may occur “in order to filter out or favour certain candidates”. In organisations where senior leadership roles have been occupied predominantly by men, as is the case with HE, merit is likely to be constructed in masculine terms which have become the norm [

13]. Therefore, notions of merit which present themselves as neutral are actually the product of masculine norms. Thus “merit” may become a new form of sexism [

54] which denies that women are being discriminated in senior appointments and this ultimately, as highlighted by McNamee and Miller [

55], can reinforce the status quo and “help those in power to perpetuate their privilege”. Moreover, empirical research by Castilla and Benard [

56] (p. 543) shows that organisational culture which promotes meritocracy paradoxically can result in greater bias in favour of men.

As seen earlier, women with experience of applying for senior leadership roles in the HE sector talked about leadership being “too narrowly defined” and that they felt that those responsible for recruitment or promotion would not see them in a leadership role. All this points to the risk that, perversely, the concept of meritocracy may end up being used to reward those who are members of the same group as those who are already in power rather than rewarding genuinely deserving individuals and “show respect for their inherent worth”.

A further line of criticism that can be levelled against the “myth of meritocracy” is that it is based on a flawed assumption that we make fully rational decisions which seek to optimise outcomes; that, for example, in a recruitment situation those responsible for making an appointment will be guided by their rationality to optimise the process’ outcomes and appoint the best possible candidate. Whilst optimising decisions and appointing the best candidate may be the intention, this may not happen in practice because our decision-making process is limited by our “bounded rationality” [

57]. This theory stresses the complexity of reality which involves a multiplicity of options that go well beyond an individual’s ability to process all the available information. Therefore, in order to manage this complexity in our decision-making process we use mental short-cuts (known as heuristics) which are shaped by the environment we live in and the kind of experiences we are exposed to. These short-cuts direct our brain to look for familiar patterns and this can explain why some women felt that people could not see them in senior leadership roles which are usually occupied by men. These are the kind of mental processes that can create cognitive biases [

58] and are responsible for erecting

invisible barriers against those candidates, such as women or BMEs, who do not look like the “

familiar type” of leader. Conversely, for those candidates who, instead, look like the “

familiar type” of leader, these kinds of mental processes can result in preferential treatment in their favour with some men being appointed not because they are the “best” but simply because they look “good enough” to fill the role. The question then is to what extent can we control and overcome these mental processes?

Many HE institutions offer or even require people who are likely to be part of senior appointment panels to undertake unconscious bias training and to become aware of heuristics and how these can influence their decisions. However, unconscious bias training, although undoubtedly helpful in raising awareness about these mental processes, is not a panacea and may not be sufficient to counter cognitive bias in practice, nor to challenge a notion of merit which has been constructed in masculine terms and is seen as the norm.

Therefore, it is argued that positive action, as permitted by s. 159, could be a useful tool to correct the bias which may occur in the construction of merit in two main ways. First of all, it would induce decision makers to undertake a more careful assessment of job applicants of different genders in order to establish whether they are “as qualified as each other”. This would help them to be vigilant about their heuristics, avoid being drawn by candidates who look like the “familiar type” of leader, most likely to be men, and push the boundaries of their rationality to engage with alternative career paths and meaning of success which, although unfamiliar, may prove to be equally meritorious if not even more deserving. Thus, far from undermining the elusive concept of meritocracy, the use of positive action in recruitment and promotion could actually improve the decision-making process and genuinely lead to the appointment of the best candidate as opposed to the “good enough” one.

Another point worth considering is that tie-break situations are not unusual and when they do happen, in order to differentiate between two candidates who appear to be equally appointable, recruiters are likely to resort to the notion of “best fit” and select the candidate who presents more similarities with the existing groups and current organisational culture. Once again, regardless of individual merit, this is likely to favour those who are more likely to fit the existing organisational demographic rather than those who belong to under-represented groups. Noon [

27] (p. 733) suggests that if “diversity” is a stated strategic objective, as it would be in the case of Higher Education Institutions, then in a tie-break situation it would be appropriate to adopt as an additional criterion “the organisational context and needs” to achieve greater diversity and use this criterion to make a final decision between two candidates who are equally appointable. This argument is strengthened by Lady Hale’s comments, currently the only female judge in the UK Supreme Court, who believes that “diversity is an indispensable feature of democracy”that, for example, would justify the adoption of positive action measures [

59] in the judiciary. Thus, from this perspective, diversity becomes an important additional criterion. In the specific case of HE, this can be a very compelling argument on at least on two counts: firstly because women represent more than half of the student population (56%) [

60] as well as of the whole of the workforce (54%) [

1] in the sector and, therefore, these levels of representation must be fairly reflected in senior posts; secondly, because HE plays a key role in shaping societal values and, unless the sector moves into a position where it can lead by example with regard to gender equality, it still lacks legitimacy.

Objection three: To judge whether two candidates are as qualified as each other is too difficult and who wrote the law has no experience of selection and recruitment processes.

As discussed earlier, research suggests [

34] that HR directors in the sector are reticent about the use of positive action in a tie-break situation. Some feel that there is always a best candidate, that two candidates are never the same, while others do not see the measure as an easy one to implement in practice. In order to challenge this objection, it may be useful to draw a parallel with equal pay legislation. Initially, equal pay legislation only applied to men and women who were doing the same or broadly similar work. However, this broadly symmetrical approach did not help to address the systematic undervaluing of some predominantly female occupations such as care work, education and health where gender occupational segregation was left unchallenged. It was only when the principle of equal pay for work of equal value was introduced by legislation that “stereotypical classifications [of work] came under fire” [

61] (p. 242). It has been highlighted that the right to claim equal pay for work of equal value had “a revolutionary potential because it asserts the right to override the determination of ‘value’ by the employer, and merely to undermine the male norm”.

The concept of work of “equal value” was put to the test for the first time in the UK in the case of

Hayward v Cammell Laird [

62] and in the subsequent landmark case of

Enderby v Frenchay Health Authority [

63]. In this case, the work of a speech therapist employed by the NHS was deemed to be of equal value to that of hospital pharmacists, a predominantly male occupation, who received a higher rate of pay than speech therapists. As cases such as this demonstrate, the concept of “equal value” required employers and trade unions to re-appraise what jobs, predominantly done by women, actually entailed and “remove the inherent bias towards men in existing job evaluation systems”[

61] (p. 243). Thus, it was possible to compare completely different jobs in order to ascertain whether the kind of expertise and skills required for different types of work could be comparable in terms of actual value and therefore, deserve the same amount of pay.

The notion of equal pay for work of equal value is now a well tried and tested concept which is regularly applied by HEIs as well as by other organisations through the use of job evaluation schemes, in order to ensure that male and female employees are paid fairly and to avoid or reduce the incidence of possible equal pay claims. Thus, although the assessment of “equal value” may be a complex exercise in practice, requiring the comparison of different sets of skills, qualifications and expertise to ensure that these are equitably remunerated, it is in fact a well-established practice among human resource practitioners. Therefore, there is no reason why HEIs which have dedicated human resource (HR) management departments should not draw on the expertise of their own HR practitioners to develop criteria to help assess when candidates can be deemed to be “as qualified as each other”. This, for example, could become part of the training for staff involved in recruitment and selection.

Moreover, there are already examples relating to selection and recruitment practices where the assessment of applicants’ skills, qualification and expertise are made on the basis of a more substantive evaluation, rather than on a formal one. For example, it is not uncommon for job specifications relating to administrative jobs in HE to require certain qualifications such as a degree or an “equivalent”. The proviso of “an equivalent” is intended to avoid overlooking potential applicants, who may be perfectly capable of doing the job, but do not hold certain types of qualifications. The proviso ensures that such candidates are not excluded from the selection process due to their lack of formal qualifications. This is particularly important given that some people belonging to older generations, when fewer people attended university, may not have a university degree but this fact is compensated by their work experience. Similarly, it is not uncommon for some people to join academia later in life, having worked in a professional capacity in sectors like Education, Law or Health. People with a professional background are less likely to hold a doctorate, which would be normally required for an academic role yet they bring equally valuable practical expertise to an academic role. In both of these examples, the lack of formal qualifications would be compensated by experience and expertise acquired in practice. Thus, in these examples the proviso for an “equivalent” to a particular qualification prevents some job applicants from being indirectly disadvantaged either because of their age group or their professional background and ensures that talented people are not overlooked. It can be seen how provisions designed to encourage the adoption of a more substantive and less formal approach to assess job applicants can lead to a fairer selection process, can overcome structural barriers and ensure better outcomes for employers.

Therefore, it is argued that useful lessons can be learned from the equal pay legislation and, in particular, from the application of the concept of work of “equal value” to counter the objection that having to assess whether two candidates are “as qualified as each other” would be too complicated. It would certainly be of some complexity as the experience around the equal pay legislation indicates, but equally, as that experience shows, it could help recruiters to unpack gender stereotypes and challenge the “male norm” which, as discussed earlier, often underpins the way in which the very concept of leadership is constructed. Having to consider whether two candidates are “as qualified as each other” and thus of equal merit, would start a process of evaluation that would make institutions have to re-appraise what is valued in leadership roles and how merit is assessed. This process could have a “revolutionary potential” in helping to override a gendered construction of merit.

Objection four: Women or other under-represented groups want to be appointed to a job because of their merits and not because of positive action.

Concerns by women and other disadvantaged groups about the possibility of being appointed to a job as a result of some form of preferential treatment rather than for their abilities is well documented [

64,

65]. However, such concerns would be understandable if they were given an automatic preference simply because of their gender. As we have seen earlier, the use of positive action in a tie-break situation presupposes that applicants have the appropriate qualifications and experience to be included in the recruitment and selection process in the first place. Therefore, if a female candidate is given preference on the basis that she is deemed to be of equal merit to a male candidate, she would have to be a serious contender and have demonstrated through the process that she is appointable to the role. The CJEU has clearly highlighted, as discussed above, the need for ensuring that when positive action measures are applied, the process allows for an individual assessment of the merit of all the candidates involved. Thus, women candidates would need to demonstrate their ability to do the job and decision makers would need to have carefully considered all the candidates on their own individual merits, regardless of their gender.

Objection five: That changing the numbers by increasing women’s representation does not guarantee a change in the organisational culture.

In the case of

Kalanke, referred to earlier, the Advocate General Tesuaro commented that: “Formal numerical equality is an objective which may salve some consciences but it will remain illusionary…” (p. 665). The fact that changing the numbers is not enough to achieve substantial change in organisations is often used as an argument against the use of interventions to increase gender diversity. However, although creating a critical mass of women in senior posts may not be sufficient to achieve wholescale change, it is nonetheless a necessary starting point to achieve change. Some may argue that a greater presence of women in leadership roles does not guarantee that these women will articulate the interests of other women and pro-actively promote greater gender equality. However, even if we accept that this may be the case, greater women’s presence in these roles is still likely to be beneficial as it will bring different perspectives in the decision-making process and “cast light on assumptions that the dominant group perceive as universal and, enhance the store of ‘social knowledge’” [

48] (p. 266). This can help to avoid the pitfalls of group thinking and improve the quality of the decision-making process within organisations. Critical mass is also necessary to overcome tokenism and to establish a “self-correcting mechanism” [

48] (p. 268). These arguments relate to the internal dynamics of organisations and how these may be changed by having a critical mass of women. An additional argument relates to the importance of having role models to encourage other women to aim for leadership roles and to counter the implicit assumptions existing in society which associate men with leadership roles. Thus, although it may not be enough to increase the numbers of women in roles where they are currently under-represented, these arguments demonstrate that if progress is to be made, it is nonetheless necessary to have a critical mass of women in these roles.