Abstract

Servant leadership has been researched internationally and various types of favourable individual, team, and organisational outcomes have been linked to the construct. Different servant leadership measures have been validated to date and a clear distinction has been made between the theory of servant leadership and other leadership theories. However, it seems that research on the implementation of servant leadership within an organisation is still in need. The main functions of a servant leader are not yet conceptualised in the literature to help researchers or practitioners to implement servant leadership successfully within organisations. After conducting a systematic literature review, the main functions of a servant leader were identified. These functions were clustered into strategic servant leadership and operational servant leadership and supported by servant leadership characteristics and competencies as defined by current literature. The results of this study might help practitioners to develop servant leaders more effectively and assist organisations to cultivate a servant leadership culture within companies. Limitations and future research needs are discussed.

1. Introduction

For the past four decades, servant leadership has evolved as a reputable leadership theory and construct. Characteristics and measures of servant leadership are well described in the literature and empirical research has started more recently to show the positive impact of servant leadership in individuals, teams, and organisations.

Servant leadership offers a multidimensional leadership theory that encompasses all aspects of leadership, including ethical, relational, and outcome based dimensions [1,2]. It is similar to but also different from current leadership theories and proposes a more meaningful way of leadership to ensure sustainable results for individuals, organizations, and societies. Servant leadership includes practices known to sustain high performing organisations such as (a) establishing a higher purpose vision and strategy; (b) developing standardised and simplified procedures; (c) cultivating customer orientation; (d) ensuring continuous growth and development; (e) sharing power and information; and (f) having a quality workforce [3,4,5]. In addition, servant leadership showed to produce favourable individual and organisational outcomes such as enhanced corporate citizenship behaviour [6,7], work engagement [8,9,10], organisational commitment [7,11,12], sales performance [13] and reduced turnover intention [14,15].

Servant leadership can be defined as a multidimensional leadership theory that starts with a desire to serve [16], followed by an intent to lead and develop others [17], to ultimately achieve a higher purpose objective to the benefit of individuals, organisations, and societies [18]. Although servant leadership was coined by Greenleaf [16], its original principles can be found in the Bible. For example, in Mark 10: 42–45 (New International Version), Jesus said: “You know that those who are regarded as rulers of the Gentiles lord it over them, and their high officials exercise authority over them. Not so with you. Instead, whoever wants to become great among you must be your servant, and whoever wants to be first must be a slave to all. For even the Son of Man did not come to be served, but to serve, and to give His life as a ransom for many”.

Servant leadership cuts across a variety of leadership theories, but is unique in the sense of its philanthropic characteristics, leadership intent and focus, and multi-dimensional leadership attributes. It focusses on serving people first [19], aims to achieve an extraordinary vision that creates value for the community [20], and includes situational, transformational, as well as personal trait dimensions of leadership. For example, the servant leadership theory shares similarities with transformational leadership in the way it focusses on people and results, but is different because it focusses firstly on people and applies a different leadership intent [19]. It also differentiates itself from transactional leadership in the serving practices it applies to achieve results [21]. Servant leadership also includes the relational aspects of leader-member exchange (LMX) to build relationships [22], uses the principles of situational leadership to develop people [21], applies the authentic attributes of authentic leadership, supports the collaboration aspects of enterprise leadership [23], includes some of the components of level 5 leadership [18], and shares the spirituality traits of spiritual leadership [24]. However servant leadership is much more comprehensive and include other important dimensions of leadership that are missing from these leadership theories [18].

Although the construct of servant leadership is well conceptualised in the literature and seems to provide favourable individual, team, and organisational results, research on the effective implementation thereof is still in need [8,25]. The application of servant leadership remains a challenge for researchers and managers [25] as the roles and functions of a servant leader are not yet clarified meaningfully in current literature. Researchers as well as practitioners call for more clarity on ways to apply servant leadership effectively within the organisational context [14].

A framework that summarises the functions of a servant leader could assist researchers, practitioners, and managers to implement servant leadership systematically and consistently within organisations. Such a framework will be valuable if it is based on the characteristics, competencies, and outcomes of servant leadership as defined by current servant leadership literature. The overall purpose of this study was to conceptualise such a framework.

Research Objectives

The general aim of this study was to establish a framework that summarises the functions of a servant leader in a meaningful way after reviewing servant leadership literature. More specifically, this study focused on defining the characteristics, competencies, measures, and outcomes of servant leadership as recently described in the literature. These characteristics, competencies, measures, and outcomes of servant leadership were used to conceptualise a framework to make servant leadership practical within organisations.

2. Research Method

2.1. Research Approach

A systematic literature review was conducted to answer four research questions. The five step procedure proposed by Khan, Kunz, Kleijnen, and Antes [26] was used to conduct a systematic literature review, namely (1) framing the question; (2) identifying relevant publications; (3) assessing study quality; (4) summarising the evidence; and (5) interpreting the finding in a meaningful way.

2.2. Research Procedure

In step one of this systematic literature review, four research questions were used, namely:

- What are the characteristics of a servant leader?

- What are the competencies of a servant leader?

- How is servant leadership measured?

- What organisational outcomes are linked to servant leadership?

In step two, inclusion and exclusion criteria were developed to identify relevant publications. Academic articles were searched on the university library databases that included the words “servant leadership” in the article title. The results were filtered to peer-reviewed articles that were published in scientific journals between the year 2000 and 2015. The full text option was activated in the search method. The inclusion and exclusion criteria were then used to screen articles.. This produced a list of relevant articles. Duplicate articles were removed and a final list of articles was recorded and coded.

In the third step, the quality of the articles was evaluated using three different quality review forms. The same evaluation criteria that Parris and Peachey [25] used in their systematic literature review were used in this study to evaluate quantitative and qualitative studies. A combination of both quantitative and qualitative evaluation questions were used to evaluate mixed method type studies. The evaluation criteria of Pyrczak [27] were used to evaluate literature review type studies. A summary of the evaluation criteria used for each type of study is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of evaluation criteria.

In the fourth step, the evidence was summarised in four evidence tables describing firstly the characteristics of a servant leader, secondly the competencies of a servant leader, thirdly the instruments used to measure servant leadership, and lastly the outcomes of servant leadership.

In the final step, the findings were interpreted in a meaningful way by means of conceptualising a framework to operationalise servant leadership in an organisation using the evidence tables from step four.

2.3. Sample Framework

Initially 114 articles were found with the keywords “servant leadership” in the title of the article that were published in scientific, peer-reviewed articles between the years 2000 and 2015. Twelve duplicates were removed. An additional 26 key-referenced articles were added to the list. After a second review of the articles using the exclusion criteria, 41 articles were removed from the list. The final number of articles that met the requirements was 87.

Of the 87 articles, 28% (n = 24) were literature type studies, 63% (n = 55) were quantitative studies, 6% (n = 5) were qualitative studies, and 3% (n = 3) were mixed method studies. Studies included were conducted in South Africa (n = 3), Australia (n = 3), China (n = 10), India (n = 2), Italy (n = 1), Kenya (n = 1), Korea (n = 1), Malaysia (n = 1), the Netherlands (n = 2), United Kingdom (n = 1), New Zealand (n = 1), Pakistan (n = 2), Portugal (n = 1), Spain (n = 2), Argentina (n = 1), Mexico (n = 2), Sweden (n = 1), Taiwan (n = 2), Turkey (n = 1), Ukraine (n = 1), the United States of America (n = 16), and within other unknown countries (n = 8).

2.4. Data Collection Method

Articles were retrieved from several databases in the university library. The following databases were searched: EBSCO host, McGraw Hill, Cambridge journals, Emerald, JSTOR, Oxford journals online, SAGE journals online, Springerlink, Taylor and Francis online, and Wiley online library. A search was conducted within the following disciplines: Business studies, entrepreneurship, human resources, humanities, management, multidisciplinary, and psychology.

A wide inclusion criterion was used to ensure a comprehensive literature search. The articles that were included were (a) published in English; (b) had the words “servant leadership” in its title; (c) published in a peer-reviewed scientific journal; (d) published between the year 2000 and 2015; (e) used a sample from the primary; secondary; and tertiary sector; and (f) were a qualitative, quantitative or literature review type study. Inclusion decisions were made after reading the title and abstract of each article.

After a more in-depth evaluation of each article, articles were excluded that were (a) published in a language other than English; (b) did not study servant leadership as the main topic; (c) published in a non-scientific journal; (d) published before the year 2000 or after the year 2015; (e) used a sample from the quaternary sector; and (f) were literature from sources other than qualitative studies, quantitative studies or literature reviews (i.e., grey literature, books, book reviews, magazine articles, conference papers, and white papers).

The inclusion and exclusion criteria used in this study are summarised in Table 2 below.

Table 2.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

2.5. Data Analysis

The quality of included articles was evaluated using quality review forms. For each study type, a different quality review form was used.

Quantitative studies were evaluated using eight quality evaluation questions adopted from the Institute for Public Health Sciences [28] namely (1) Was the study clearly focussed? (2) Was sufficient background provided; (3) Was the study well planned? (4) Was the method used appropriate? (5) Was the measures used validated? (6) Was the number of participants adequate and applicable? (7) Was adequate statistical methods used? and (8) Was the findings clearly stated?

Qualitative studies were evaluated using a critical review form [29] that consisted of eight quality questions, namely (1) Was the purpose of the study clearly stated? (2) Was relevant background literature provided? (3) Was the research design appropriate? (4) Was theoretical or philosophical perspectives identified? (5) Was the selection and context of participants well described and relevant? (6) Was procedural rigour evident in the data collection and analysis? (7) Was there evidence of the four components of trustworthiness (credibility, transferability, dependability, and conformability)? and (8) Was the results comprehensive and well described? Both quantitative and qualitative review forms were used for mixed method studies.

Literature review type studies were evaluated using seven quality review questions. Four questions were adopted from Pyrczak [27] namely (1) Was the literature review extensive on a topic? (2) Was the literature review critical? (3) Was current research cited? (4) Has the researcher distinguished between research, theory, and opinion? The following three questions were added: (4) Was the literature focussed? (5) Was the literature review well organised? and (7) Were quality literature sources used?

Articles were appraised individually using the abovementioned quality review forms. If an evaluation criterion was met, a score of 1 was allocated. A total score and percentage was then calculated for each article. Thereafter articles were categorised into high quality, medium quality, and low quality. A list of the final articles used is available in Appendix A, Table A1.

After evaluation, the research questions were used to extract data from the articles. The results were themed and summarised into four evidence tables. The quality rating of the articles was used to classify the strength of evidence supporting a theme. Three evidence classifications were made, namely (a) strong evidence; (b) moderate evidence; and (c) insufficient evidence [25]. A strong evidence classification was assigned when two or more high quality articles or one high and two medium quality articles supported a theme. A moderate evidence classification was assigned when one high and one medium quality article or two medium quality articles supported a theme. An insufficient evidence classification was assigned if a theme was not supported by either strong or moderate evidence.

The results of the data analysis are described in the next section.

3. Results

In general, the findings indicated that servant leadership is researched internationally, measured by different instruments, and are linked to favourable individual, team, and organisational outcomes. The findings showed that no consensus has been reached to date by researchers on the characteristics, competencies, and measurement of servant leadership. However, servant leadership has shown to be a reputable leadership theory distinguishable from other current leadership theories.

In this study sample, servant leadership was researched in 21 different countries and consisted of 5 qualitative studies, 55 quantitative studies, 3 mixed method studies, and 24 literature reviews. 2 (40%) qualitative studies were rated as high quality, 1 (20%) as medium quality and 2 (40%) as low quality. In terms of quantitative studies, 48 (87%) were rated as high quality, 5 (9%) as medium quality, and 2 (4%) as low quality. 2 (67%) mixed method studies were of high quality and 1 (33%) of low quality. 12 (50%) literature review type studies were rated as high quality, 8 (33%) as medium quality and 4 (17%) as low quality.

The themes that emerged from the data are discussed in the next section in accordance with the research questions.

3.1. The Characteristics of Servant Leadership

This systematic literature review identified eight characteristics of a servant leader, namely:

- (1)

- Authenticity

- (2)

- Humility

- (3)

- Compassion

- (4)

- Accountability

- (5)

- Courage

- (6)

- Altruism

- (7)

- Integrity

- (8)

- Listening

Strong evidence was found for all the abovementioned servant leader characteristics.

Authenticity was described in the literature as showing one’s true identify, intentions, and motivations [30], adhering to strong moral principles [31], and being true to oneself [32]. It was also seen as being open to learn from criticism [33] and having consistent behaviour. Authenticity was mentioned in 17 different articles as a characteristic of a servant leader.

Humility was defined as being stable and modest with a high self-awareness of one’s strengths and development areas [9,34], having a humble attitude [7], being open to new learning opportunities [18], and perceiving one’s talent and achievements in the right perspective [34]. Humility was not described as a self-depreciating attribute (thinking less of oneself), but rather as a characteristic that focusses more on others (thinking of oneself less) [18,23,35,36]. Humility seems to be the opposite of prideful or egocentric behaviour [36,37]. Humble leaders value and activate the talent of others, enjoy helping others succeed, and give credit to others when a task was completed successfully [18,38]. Humility was also described as a virtuous attitude that uses positional power to the advancement of others [36]. Humility was cited in 27 different articles as a characteristic of servant leadership.

Compassion was perceived in the literature as having empathy [17,39,40,41,42,43], caring for others, being kind, [17,20,44,45] forgiving others for mistakes [46], accepting and appreciating others for who they are [18,31,37], and showing unconditional love (agape love) towards others [36,38,44]. Additional keywords referenced in the literature to describe compassion were to value people, serve others, putting others first, and being good to others [18,25,45,47,48,49,50,51,52]. Emotional healing also seems to be closely related to compassion. It was described as helping others recover from hardships or difficulties [41], having a concern for the professional healthcare of others [44], being sensitive towards others [43], assisting in healing relationships [17], and healing oneself and others to become whole [42]. Compassion was referenced by 42 different articles as a characteristic of servant leadership.

Accountability was described in the literature as being responsible [18], ensuring transparent practices [53], holding others accountable, monitoring performance [18], and setting clear expectations in accordance with an individual’s capability [10]. It was mentioned in 7 different articles as being a characteristic of servant leadership.

Courage was cited in 6 different articles as one of the characteristics of servant leadership. It was defined as being open to take calculated risks, standing up for what is morally right, despite negative adversary [31,46], and having high ethical conduct [13].

Altruism was described as being others orientated, selfless [37,47,50], and having the desire to positively influence and helping others become better in life by serving their needs consistently [36,41]. This behaviour is extended to make a positive difference, not only in people, but also in organisations and in society [41,50]. This servant leadership characteristic was mentioned in 17 different articles.

The keywords referenced to describe integrity in the literature were: being honest, fair [31], having strong moral principles [32,50,53], behaving ethically, and creating an ethical work climate [32,43,50]. Integrity was cited in 30 different articles as a characteristic of a servant leader.

Listening was described as a deep commitment of a leader to listen actively and respectfully [17,41,54], by asking questions to create knowledge [54,55], providing time for reflection and silence [17], and being conscious of what is unsaid [17,52]. Listening was referenced as a servant leadership characteristic in 20 different articles.

3.2. The Competencies of Servant Leadership

This study made a distinction between the characteristics and competencies of a servant leader. A characteristic was perceived as a personality trait that regulates the way a person think, feel, and behave [56]. Competency, on the other hand, was understood as a combination of cognitive and technical knowledge, skills, traits, and habits applied systematically to achieve a specific standardised outcome [57,58].

Strong evidence was found for the following four servant leadership competencies:

- (1)

- Empowerment

- (2)

- Stewardship

- (3)

- Building relationships

- (4)

- Compelling vision

Empowerment was mentioned in 54 of the sampled articles as an undertaking of a servant leader. Empowerment was defined by researchers as a commitment to the process of:

- Developing others to prosper personally, professionally, and spiritually [17,18,39,40,42,49,59,60],

- Having a transformational influence on followers [24],

- Transferring responsibility and authority to followers [7],

- Providing clear directions and boundaries [43],

- Aligning and activating individual talent [7,35,36,54,61],

- Sharing information and encourage independent problem solving [17,43],

- Providing the necessary coaching, mentoring, and support according to the need of an individual [62],

- Creating an effective work environment [63],

- Building self-confidence, wellbeing, and proactive follower behaviour [9,46,55,63], and

- Helping followers mature emotionally, intellectually, and ethically [33].

Stewardship was defined in the literature as the process to take accountability [10,64] for the common interest of a society, an organisation, and individuals [6,10,36,41,50,65], and to leave a positive legacy [66], with an attitude of not being the owner, but rather a caretaker [6,10,35,36,41,50,61,67]. Stewardship was referenced by 37 different articles as a servant leadership practice.

Building relationships was cited by 54 articles as a fundamental role of a servant leader. It was defined by literature as the process to:

- Build trustful relationships with individuals, customers, and the community [13,18,19,24,32,36,43,45,46,47,53,54,55,68,69],

- Create an environment of care, support, encouragement, and acknowledgement [18,37,46],

- Communicate effectively [17] by spending quality time with followers [24] to share and create knowledge [54,55],

- Understand the needs, aspirations, potential, and mental model of others [18,32,43,54,55,59], and

- Work in collaboration [17,18,24] and having common values [32].

Setting a compelling vision was described as the ability to conceptualise a higher vision [17,18,36], to link past events and current trends with potential future scenarios [6,17,18,39,50,65], and to create value for a community. These keywords related to this servant leader role were mentioned in 31 articles.

3.3. Measurement of Servant Leadership

The sampled literature indicated 10 different servant leadership measures. The first instrument, called the Organisational Leadership Assessment (OLA), was developed by Laub [70] and measures servant leadership as a six factor construct. The factors included in this instrument were authenticity, shares leadership, valuing people, developing people, builds community, and providing leadership. It was used in one high quality study in the sample and was cited in another six high quality articles.

The second servant leadership questionnaire was developed by Page and Wong [71] and measures 12 servant leadership attributes, namely humility, caring for others, servant-hood, integrity, empowering others, developing others, leading, modelling, team-building, shared decision-making, visioning, and goal setting. Two high quality studies within the sample used this instrument and another seven high quality articles referenced it.

A third instrument was developed by Dennis and Bocarnea [72] and measures humility, agape love, empowerment, trust, and vision as servant leadership characteristics. This measure was used by one high quality study in the sampled literature and cited by another six high quality articles.

A fourth servant leadership questionnaire evaluates seven servant leadership attributes, namely putting subordinates first, behaving ethically, empowering subordinates, helping subordinates grow and succeed, forming relationships with subordinates, conceptualising skills, and creating value for the community [73]. Thirteen high quality studies within the sample used this instrument to measure servant leadership. It was also mentioned in another five high quality studies as a suitable measure for servant leadership.

The servant leadership questionnaire (SLQ) of Barbuto and Wheeler [41] was another instrument referenced. This instrument consists of five servant leadership dimensions, namely emotional healing, altruistic calling, organisational stewardship, persuasive mapping, and wisdom. The SLQ was used by 8 studies (5 high quality, 2 medium quality, 1 low quality) within the sample and cited by another 9 high quality articles.

Hale and Fields [48] also developed a servant leadership questionnaire that measures three servant leader attributes, namely humility, service, and vision. This questionnaire was cited by one high quality article. No studies within the sample used this instrument.

A seventh servant leadership measure was developed by Wong and Davey [74] that measures servant leadership as a six factor construct. The factors are modelling authenticity, humility and selflessness, modelling integrity, serving and developing others, and inspiring and influencing others. It was referenced by one high quality article. None of the sampled articles used this instrument.

Liden, Wayne, Zhao, and Henderson [43] combined items of three previously developed questionnaires of Barbuto and Wheeler [41,71,73] to develop a seven factor servant leadership questionnaire (SLQ). This servant leadership questionnaire measures the following attributes: emotional healing, putting subordinates first, behaving ethically, helping subordinates grow and succeed, conceptualising skills, and creating value for the community. It was used by 9 high quality research studies in the sample and cited by another 9 high quality articles.

An additional scale, named the servant leadership behaviour scale (SLBS), was validated by Sendjaya, Sarros, and Santora [24] and measures six servant leader characteristics, namely authentic self, conventional relationship, voluntary subordination, transforming influence, responsible morality, and transcendental spirituality. This instrument was used by four research studies of high quality and referenced by an additional eight high quality articles.

The latest survey validated was the servant leadership survey (SLS) of van Dierendonk and Nuijten [46]. It measures eight servant leadership attributes, namely authenticity, humility, forgiveness, accountability, courage, standing back, empowerment, and stewardship. It was used by four high quality studies in the sample and referenced by another eight high quality articles.

3.4. Outcomes of Servant Leadership

The outcomes linked to servant leadership were divided into three categories, namely:

- (1)

- Individual outcomes

- (2)

- Team outcomes

- (3)

- Organisational outcomes

Literature type studies were excluded in this section as findings related to outcomes were based on empirical evidence (quantitative, qualitative, and mixed-method studies). The findings are discussed in line with the themes emerged from the results that produced strong evidence.

3.4.1. Individual Outcomes

Servant leadership was positively related to work engagement, organisational citizenship behaviour, innovative behaviour, organisational commitment, trust, self-efficacy, job satisfaction, person-job fit, person-organisational fit, leader-member exchange, and work-life balance in the sampled studies. Furthermore, it was negatively related to burnout and turnover intention.

In terms of work engagement, four high quality studies indicated that servant leadership enhances work engagement [8,9,10,59]. Goal congruence and social interaction moderated the relationship between servant leadership and work engagement [8]. In another study, organisational identification and psychological empowerment mediated the relationship between these two variables [9]. Servant leadership was also negatively correlated with disengagement [14].

Seven high quality studies indicated that servant leadership enhanced organisational citizenship behaviour on an individual level. Five studies showed a positive relationship between servant leadership and organisational citizenship behaviour [6,7,75,76,77]. One study reported a positive relationship between servant leadership and service-orientated organizational citizenship behaviour, mediated by leader-member exchange [78]. Another study reported a positive link between servant leadership and customer-orientated organizational citizenship behaviour [79]. Positive psychological capital mediated the relationship between these two variables. Other factors that mediated the relationship between servant leadership and organisational citizenship behaviour were leader-member exchange [75], psychological contract [76], commitment to supervisor, self-efficacy, procedural justice climate, and service climate [77].

Innovative behaviour was positively related to servant leadership by three high quality studies. The first study showed that servant leadership was positively linked to serving culture which in return enhanced creative behaviour [23]. The second study reported that servant leadership increased creative behaviour mediated by promotion focus [52]. The third study indicated that psychological contract mediated the relationship between servant leadership and innovative behaviour [76].

The relationship between servant leadership and organisational commitment was confirmed by four high quality studies and one medium quality study. Three studies showed that servant leadership had a direct impact on organisational commitment [7,11,12]. One study indicated that organisational support mediated the relationship between servant leadership and affective commitment [80]. In another study, servant leadership enhanced both affective and normative commitment in which organisational support mediated the relationship between servant leadership and affective commitment [81].

Trust was positively influenced by servant leadership in four different studies. The first study found a positive relationship between servant leadership and interpersonal trust [68]. The second study reported a positive relationship with employee trust [11]. The third study showed that servant leadership enhanced affective trust [81]. The fourth study reported that trust developed and grew as a result of servant leadership [45].

Five studies (4 high quality, 1 low quality) confirmed that servant leadership increased the job satisfaction level of employees [6,45,49,82,83]. This relationship was mediated by procedural justice [82] and psychological climate [6].

In terms of work-life balance, one high quality study indicated that servant leadership positively influenced work-family positive spill-over and negatively influenced work-family conflict [84]. Another study showed that organisational identification mediated the relationship between servant leadership and work-to-family enrichment [85].

Other findings reported that servant leadership enhanced self-efficacy [46,86], person-job fit [59], person-organisational fit [12], and leader-member exchange [22,75,79].

3.4.2. Team Outcomes

Servant leadership was positively related to four team or group outcomes, namely (1) group organisational citizenship behaviour; (2) group identification; (3) service climate and culture; and (4) procedural justice climate.

The sampled articles reported that servant leadership enhanced organisational citizenship behaviour, not only on an individual level, but also on a group or team level. In one high quality study dyadic communication style agreement mediated the relationship between servant leadership and group organisational citizenship behaviour [87]. Another study indicated that servant leadership influenced team potency positively which in return enhanced team organisational citizenship behaviour [60].

Three high quality studies indicated that servant leadership enhanced group identification. The first study showed a direct positive relationship with group identification [86]. A second study reported that a serving culture mediated the relationship between servant leadership and employee identification [23]. A third related study indicated that servant leadership enhances organisational identification [85].

Other findings stated that servant leadership increased serving culture [23], serving climate [77], and procedural justice [77,82] within organisations.

3.4.3. Organisational Outcomes

Two major organisational outcomes emerged from the data, namely (1) customer service and (2) sales performance.

Seven high quality articles indicated that servant leadership influenced customer service positively in different ways. Servant leadership was positively related to customer service performance [86], service-orientated organisational citizenship behaviour, customer value co-creation [78], customer trust in the firm, customer satisfaction [64], customer orientation [12], customer serving behaviour [23], and value enhancing behaviour [88]. Servant leadership was also negatively related to customer turnover [45]. Mediating variables in the aforementioned relationships were social identity [86], positive psychological capital, service-orientated organisational citizenship behaviour [78], employee trust [64], and a caring ethical climate [88].

Servant leadership also affected sales performance in various ways. In the study of Schwepker and Schultz [88], servant leadership increased sales performance directly. Another study indicated that ethical climate mediated the relationship between servant leadership and sales performance [13]. Servant leadership was also positively related to a serving culture which in return enhanced organisational performance [23]. Customer orientation was also positively influenced by servant leadership which produced higher outcome performance [12].

In conclusion, servant leadership positively influenced individuals, teams, and organisations in various ways. A summary of the results is provided in Table 3.

Table 3.

Summary of results.

4. Discussion

The final stage of this systematic literature review was to interpret the findings in a meaningful way. This section consolidates the findings in terms of the characteristics, competencies, and outcomes of a servant leader into two main performance areas of a servant leader, namely (1) strategic servant leadership and (2) operational servant leadership.

4.1. Strategic Servant Leadership

Strategic servant leadership is divided into two main functions, namely (1) to set, translate and execute a higher purpose vision and (2) to become a role model and ambassador. These two functions are described in accordance with the study results.

4.1.1. Function 1: Set, translate, and Execute a Higher Purpose Vision

One of the servant leadership competencies identified by the results was to set a compelling vision for an organisation. This competency was described in the literature as conceptualising a higher vision, linking past events and current trends with potential future scenarios, and creating value for the community. It is important to note that this vision consists of three major components, namely (1) a higher purpose; (2) value creation for the community; and (3) linking the past, present and the future.

A higher purpose vision is worthless without translating and executing it. It is vital for a servant leader to translate the vision into workable goals that is clearly understood by followers [70]. This process involves translating the vision into a mission, strategy, and practical goals. It also includes designing the capacity and capability frameworks as well as processes, policies, and systems to support the vision, mission, and strategy. A capacity structure refers to the type and number of positions required to execute the strategy, whereas the capability framework means the skills, knowledge and attributes (competencies) required to achieve the strategy. Processes refer to the business procedures and value chains of each function within the organisation. Policies are the organisational policies or standards that govern organisational practices while systems are the information or technological systems required to achieve the vision, mission, and strategy.

This process of developing the capability and capacity frameworks and supporting it with relevant processes, policies, and systems relate well to the factors of a high performing organisation such as (a) establishing and communicating a clear vision, mission, and strategy; (b) being customer orientated; (c) having simple; standardised; and innovative processes and systems; (d) ensuring continuous learning and development; and (e) sustaining a quality workforce [3,4,89,90]. It also relates well to the Mckinsey’s 7-S model that suggest an integration of seven factors to enhance organisational effectiveness, namely (1) strategy; (2) style; (3) skills; (4) systems; (5) structure; (6) staff; and (7) shared values [91,92,93]. In this process of developing capacity and capability frameworks to support the higher purpose vision, a servant leader prepares the organisation to serve customers and employees effectively. After translating the vision into a mission, strategy, and goals and developing the capability and capacity frameworks as well as the policies, processes, and systems to support that vision, a servant leader continuously strives to achieve it by serving employees [53] and by aligning them to the capacity and capability frameworks as well as the policies, processes, and systems. This is different from the transformational approach to only encourage employees to achieve organisational goals [41].

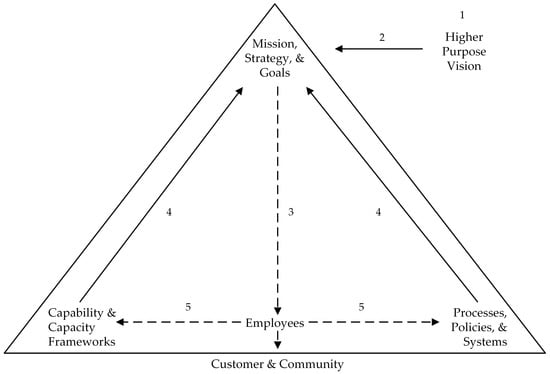

A systematic display of this function is provided in Figure 1 below. It illustrates how a servant leader first sets a higher purpose vision and then translates it into a mission, strategy, and goals. The mission, strategy, and goals focus primarily on the customer and secondarily on employees because employees are closest to the customer [4]. Thereafter the capability and capacity frameworks are developed and processes, policies, and systems are designed to support the strategy. The skills and knowledge of employees are then aligned to the capability and capacity frameworks and with the designed processes, policies, and systems. The outcomes linked to servant leadership indicated that a servant leader enhances customer service and sales performance. This could be achieved with this function by focusing the mission, strategy, and goals on the customer first (creating a serving culture) and then putting the infrastructure in place to enable employees to meet customer needs and to sell authentically [4].

Figure 1.

Process to set, translate, and execute a higher purpose vision.

Two servant leader characteristics identified by the results were altruism and courage. Altruism was described in the literature as being others orientated, selfless, having the desire to help others become better in life, and making a positive difference in the organisation and society. For a servant leader to set, translate, and execute a higher purpose vision effectively he or she needs to put the interest of others above his or her own and diligently serve others to become better individuals, organisations, and societies [70]. The desire to serve others and make a positive difference is engrained in a servant leader’s character [16,18]. Without this characteristic, leaders may set an egocentric or selfish vision focusing on self-advancement instead of creating value for the community [21]. Hence, a higher purpose vision can only be set when a leader has altruism. Courage, on the other hand, was described by the results as being open to take calculated risks, standing up for what is morally right, and having high ethical conduct. A willingness to take calculated risks may become apparent when linking past events and present trends with future scenarios while creating a compelling vision. Portraying ethical conduct and standing up for the interest of others also become important when serving the needs of others (employees, customers, and community). Without the courage to stand up for what is right and aim to do things ethically to the best interest of others, employees or a community might become victims of destructive outcomes caused by selfish leaders [94]. Courage is therefore a necessary trait to set, translate, and execute a compelling vision.

In summary, a servant leader applies courage and altruism to set, translate, and execute a compelling vision to the benefit of employees, the organization, and society.

4.1.2. Function 2: Become a Role Model and Ambassador

The literature also identified authenticity and humility as servant leadership characteristics. Authenticity was described by the results as showing one’s true identify, intentions, and motivations, being open to learn from criticism, and having consistent behaviour. Humility, on the other hand, was defined by the results as stability, modesty, high self-awareness, openness to learn, and viewing one’s own talent appropriately. Four general principles or practices are described in these definitions, namely:

- (1)

- Self-knowledge

- (2)

- Self-management

- (3)

- Self-improvement

- (4)

- Self-revealing

Self-knowledge is about truthfully discovering one’s own strengths and weaknesses in terms of values, personality, abilities, and talents. Before a servant leader can show his true identity, intentions, or motivations (authenticity), he first needs to know and understand what it is. The same is true in terms of individual talents. Before a servant leader can view his own talents in perspective (humility), he needs to know which talents he possesses. When a servant leader becomes aware of his own strengths and weaknesses in terms of values, personality, abilities, and talents, he can become more authentic by showing his true identity, intentions, and motivations and become more humble by putting his talents in perspective. Self-knowledge also enables a servant leader to build on his strengths by aligning it with specific job requirements and to develop his weaknesses by means of personal development or delegating those responsibilities to someone else more talented in that area.

Self-management is about managing oneself mentally, emotionally, and physically that fosters optimal wellbeing and personal effectiveness. Servant leaders should manage themselves well to show stable, modest, and consistent behaviour. Stable and modest behaviour (humility) is possible when servant leaders are in the right mental and emotional state and consistent behaviour (authenticity) is furthermore possible when a servant leader is physical, mentally, and emotionally well. Self-management can therefore be divided into three categories, namely (1) managing the mind; (2) managing emotions; and (3) managing physical health. Managing the mind refers to managing one’s thoughts and cognitive activity to form new habits to ultimately enhance personal effectiveness. Neuroplasticity is a good example of how thinking patterns can improve behaviour [95] as well as personal effectiveness [96]. Servant leaders need to apply these mental techniques to ensure they are in the optimal state to serve others. Managing emotions refer to emotional intelligence and emotional maturity. Emotional intelligence is a set of emotional and social skills to perceive and express oneself well, to build good relationships with others, to cope with difficult circumstances, and to use emotions effectively [97]. Emotional maturity is considered as being selfless, exercising self-control, and not being easily offended [21]. Servant leaders appraise and express emotions effectively, use emotions to improve cognitive processes and decision-making, and successfully regulate emotions by means of regular reflection [98]. Barbuto, Gottfredson, and Searle [20] found significant correlations between emotional intelligence and five servant leadership attributes, namely altruistic calling, emotional healing, wisdom, and organizational stewardship. Chathury [21] also noted that emotional self-regulation plays an important role in being an effective servant leader. A servant leader therefore portrays high levels of emotional intelligence and maturity and manages his emotions well to lead and serve others. The third principle of managing self is to manage one’s physical wellbeing. Managing physical wellbeing means to improve one’s physical state to enhance personal effectiveness by sustaining high levels of human energy, ensuring work-life balance, and practicing healthy physical habits. Without physical wellbeing, servant leaders could find it difficult to serve others effectively.

Self-improvement refers to continuous personal development to enhance personal effectiveness and relevance. This systematic literature review revealed that both authenticity and humility had an openness to learn as part of its definition. Servant leaders are humble and authentic enough to know they need to continuously learn and develop, not only to stay relevant in a changing world, but also to have the capability to develop and promote others [2,16,21]. Servant leaders are aware of the fact that they cannot empower others if they are not competent themselves.

Self-revealing refers to being transparent, showing one’s own true self, and living the values set to support a higher purpose vision. This is part of being authentic [99]. Servant leaders align their behaviour with the vision and values of the organisation [53] and role model the necessary behaviour in an authentic way to achieve a higher purpose vision.

Another servant leadership characteristic highlighted by the results was integrity. Integrity was described as being honest, fair, and ethical, having strong moral principles, and creating an ethical work climate. Servant leaders do things legitimately [100], treat others fairly, and portray high levels of honesty [31]. A servant leader should role model these behaviours and should influence followers accordingly. Hence, another objective of a servant leader can be to “stay within the rules” which relates to being ethical and portraying high levels of integrity.

After setting a higher purpose vision, mission, and strategy, servant leaders must first lead themselves well before they can lead others [101]. Leading and managing self means to enhance personal capability in terms of personal effectiveness, high productivity, continuous development, excellence, high individual performance, and adhering to organisational values [102]. Personal leadership also includes the understanding of own talents, abilities, strengths, and weaknesses and how to activate these in the best possible way to serve others [101]. When servant leaders lead themselves well, they become role models for followers. Followers might then in return emulate their leader’s behaviour and become servant leaders themselves by applying the same behavioural principles [23,103]. This would ultimately contribute towards achieving the higher purpose vision. A competency of personal capability can thus be added to this function. Personal capability can be defined as leading and developing oneself towards enhanced personal effectiveness, wellbeing, and optimal functioning.

In summary, servant leaders use the characteristics of authenticity, humility, and integrity as well as the competency of personal capability and apply the principles of self-knowledge, self-management, self-improvement, self-revealing, and staying within the rules to become role models and ambassadors for followers in line with a higher purpose vision.

Once servant leaders provided strategic servant leadership by setting and translating a higher purpose vision and becoming role models for that higher vision, they start to apply the functions of operational servant leadership.

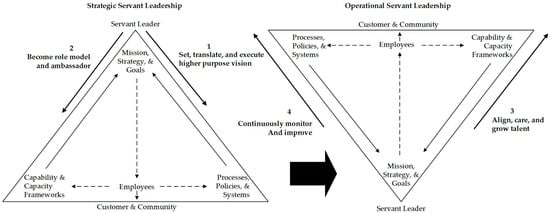

4.2. Operational Servant Leadership

In the strategic servant leadership functions, a higher purpose vision was set and the leader’s own behaviour was aligned accordingly to become a role model and ambassador to followers. In operational leadership the hierarchy is flipped upside-down, in which the servant leader then serves and empowers employees to achieve the higher purpose vision [101]. In this way employees do not serve the leader in the expense of the customer, but employees are served and empowered by the leader to render exceptional customer service in line with the set vision [4] and to help followers become servant leaders themselves [16]. Servant leaders also apply monitoring and improvement mechanisms to ensure continuous growth. In Figure 2, the process to “flip-the-hierarchy” is displayed.

Figure 2.

Process to “flip-the-hierarchy”.

Operational servant leadership aims to achieve two main functions, namely to (1) align, care, and grow talent and to (2) continuously monitor and improve. These two functions are described in accordance with the study results.

4.2.1. Function 3: Align, Care, and Grow Talent

Building relationships and empowerment emerged as servant leadership competencies from the systematic literature review. Building relationships were defined by the results as the method to (a) understand the needs, aspirations, potential, and mental model of others; (b) create an environment of care, support, encouragement, and acknowledgement; and (c) build trustful relationships with individuals, customers, and the community. Empowerment, on the other hand, was defined by the results as the process to (a) align and activate talent; (b) create an effective work environment; (c) develop others; (d) transform followers; (e) transfer responsibility; (f) share information; (g) coach, mentor, and support followers individually; (h) build self-confidence; wellbeing and proactive follower behaviour; and (i) help followers to mature emotionally, intellectually, and ethically.

One element of building trustful relationships was described as understanding the needs, aspirations, potential, and mental model of others. Similarly, one element of empowerment included the process of aligning and activating talent. A primary objective of a servant leader might therefore be to understand individual talent, passion, and purpose and to align it with the requirements of a position as well as the purpose of the organisation. In this way a servant leader releases individual talent in accordance with the organisational vision [44]. The capability and capacity frameworks developed in the strategic servant leadership functions might be useful to identify and align individual talent. After identifying and aligning individual talent, another role of a servant leader can be to create an effective working climate to activate and release individual talent.

Creating an effective work environment of care, support, encouragement, and acknowledgement were part of both definitions of building relationships and empowerment. This is closely linked to the concepts of the job demands-resources model [104]. This model suggests that a balance between job demands and job resources will enhance work engagement, decrease burnout, and in return improve organisational outcomes [105,106] such as high organisational commitment and low turnover intention [106,107,108]. Job resources refer to resources such as supervisory support, job clarity, information, communication, participation in decision-making, and growth opportunities [109]. This is similar to the responsibilities of a servant leader to provide the support [18,37,46], job clarity [43], information [17,43], communication [17], participation [17,18,24], and growth opportunities [17,18,39,40,42,49,59,60]. The outcomes of servant leadership, identified by the results, were also similar to that of the job demands-resources theory. Servant leadership was positively related to organisational outcomes such as higher organisational commitment [7,11,12] and lower employee turnover intention [14,15]. Servant leadership was also positively related to work engagement [8,9,10,59] and negatively related to burnout [110]. Taking these perspectives into consideration, the second objective of a servant leader might be to care and protect followers. To care for followers might include creating an effective working climate by providing the necessary job resources to enhance work engagement that ultimately results in favourable individual and organisational outcomes. Servant leaders also protect the wellbeing of followers by providing more job resources and by managing the job demands of followers to decrease burnout that causes ill health [107].

A third objective of a servant leader can be to grow followers. Empowerment was defined by the results as developing others, transforming followers, transferring responsibility, sharing information, coaching, mentoring, and supporting followers individually, building self-confidence, wellbeing and proactive follower behaviour, and helping followers to mature emotionally, intellectually, and ethically. All of these empowerment practices relate to growing and developing followers. Empowerment and building trustful relationships is interlinked in a way that without a trustful relationship, it could be difficult to empower others. Both these competencies are a necessity to ensure continuous individual growth. Empowerment not only focusses on vocational growth, but also emotional, intellectual, and ethical maturity [33] and aim to release individual potential [69]. This is emphasised as one of the fundamental goals of servant leaders to make followers servant leaders themselves [16]. In other words, a servant leader grows and development others and activates and releases individual talent towards a greater good.

In terms of servant leadership characteristics, the traits of listening and compassion could also form part of this function. Compassion was described by the results as having empathy, caring for others, being kind, forgiving others, appreciating others, and showing unconditional love. Listening was defined by the results as a commitment to listen actively and respectfully, by asking questions to create knowledge, providing time for reflection, and being conscious of what is unsaid. These two traits would enable a servant leader to build trustful relationships with others and to understand the needs of followers to create an effective working climate and culture and to grow and release individual talent. A servant leader should therefore listen first to understand individual needs before applying compassion to provide the necessary support to activate individual talent. Both listening and compassion might be helpful to identify and align talent, to care for and protect followers, and to grow talent effectively.

In summary, servant leaders apply listening and compassion to build trustful relationships and to empower followers. This is done by firstly aligning individual talent with the requirements of a position, and secondly to care and protect followers by creating an effective working climate that activate individual talent. Thereafter a servant leader continuously grows and empowers followers to release individual talent.

4.2.2. Function 4: Continuously Monitor and Improve

The last servant leader competency identified by the results was stewardship. Stewardship was defined as the process to leave a positive legacy by means of taking accountability for the common interest of society, the organisation, and individuals, with a perspective of being a “caretaker” and not an “owner”. Servant leaders are good stewards or managers of finances, assets, resources, and positions [21,100]. They act as trustees [21,100] that continuously monitor performance [46], practice good governance [53], and track progress towards the achievement of a higher purpose vision, mission, and strategy of the organisation [100]. Servant leaders continuously implement positive change interventions [35] and modify systems and procedures to enhance customer and employee satisfaction [21]. Long lasting legacies can be created for individuals, organisations, and societies when servant leaders practice good stewardship.

A final characteristic identified by this systematic literature review was accountability. Accountability was defined by the results as being responsible, ensuring transparent practices, holding others accountable, and monitoring performance. Without the attribute of accountability, it would be difficult to apply good stewardship. It therefore falls well within the scope of this function.

In short, servant leaders apply accountability to become good stewards of the finances, assets, resources, and positions entrusted with and continuously monitor performance and improve systems, policies, and procedures to leave a positive legacy in people, organisations, and societies.

Table 4 presents a summary of the four functions of a servant leader with its respective objectives, characteristics, and competencies as described by the results. It suggests that a servant leader firstly provides strategic servant leadership by setting, translating, and executing a higher purpose vision and by becoming a role model and ambassador. Thereafter a servant leader provides operational servant leadership by “flipping-the-hierarchy” upside-down and by aligning, caring, and growing talent, continuously monitoring progress, and improving policies, processes, systems, products, and services.

Table 4.

Functions of a servant leader.

5. Conclusions

The purpose of this study was to discover the characteristics, competencies, measures, and outcomes of servant leadership by means of a systematic literature review. The results highlighted eight servant leadership characteristics, namely authenticity, humility, integrity, listening, compassion, accountability, courage, and altruism. The servant leadership competencies were identified as building relationships, empowerment, stewardship, and compelling vision. The systematic literature review also indicated ten measures of servant leadership. The outcomes related to servant leadership were clustered into individual outcomes, team outcomes, and organisational outcomes. On an individual level servant leadership positively influenced work engagement, organisational citizenship behaviour, creativity and innovation, organisational commitment, trust, self-efficacy, job satisfaction, person-job fit or person-organisational fit, leader-member exchange, and work-life balance. In addition, servant leadership was negatively related to burnout and turnover intention. On a team or group level, group organisational citizenship behaviour, group identification, service culture or climate, and the procedural justice climate were positively influenced by servant leadership. Finally, on an organisational level, servant leadership was positively related with customer service and sales performance.

The results were used to identify four general functions of a servant leader clustered into strategic servant leadership and operational servant leadership. Each function was supported by competencies and characteristics of a servant leader as defined in current literature.

This study made a theoretical and practical contribution to the body of knowledge related to servant leadership.

5.1. Implications for Management

The results of this study provide managers and practitioners with a possible outline to develop servant leaders within organisations. For example, the functions, objectives, characteristics, and competencies provided in this study can be used to design curriculums for servant leadership development programmes. Management consultants and organisational development practitioners might also use the results to cultivate a servant leadership culture within an organisation. The performance areas and functions of a servant leader provided by this study can be incorporated within recruitment, performance management, and remuneration systems of a company to select, review, and reward leaders. In return, management and other stakeholders could expect favourable individual, team, or organisational outcomes that servant leadership produces.

5.2. Limitations

Normally a systematic literature review is done by at least two researchers, especially the evaluation of the quality of articles [111]. In this study, however, only one researcher evaluated the quality of studies.

Another limitation was the scope of this literature review. It excluded grey literature, books, book reviews, magazine articles, conference presentations, and white papers. It also excluded studies done before the year 2000 and after 2015 as well as research done in the quaternary sector. Literature from these sources, however was used to support the findings in the discussion section, but was not used in the actual review.

5.3. Future Research Suggestions

The relationship between the job demands-resources model and the functions of a servant leader could be an interesting future study. This could highlight how a servant leader can create an effective working climate and culture within an organisation.

Another future study might be to design a leadership development programme based on functions and performance areas mentioned in this study and to test its effectiveness to enhance servant leadership attributes. Experimental type studies might be valuable in this regard.

The functions and performance areas of a servant leader may also help to create serving organisations, organisations that leave behind legacies in individuals and the community throughout its existence. Action research and case studies might validate this possibility.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at www.mdpi.com/2076-3387/7/1/5/s1, Table S1: Results: Servant leadership characteristics, Table S2: Results: Servant leadership competencies, Table S3: Results: Servant leadership measures, Table S4: Results: Servant leadership outcomes.

Author Contributions

Michiel Frederick Coetzer conceived and designed the review, performed the systematic literature review, and wrote the paper. Mark Bussin contributed to the design and writing of the paper. Madelyn Geldenhuys contributed to the design and writing of the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

List of final articles.

| Article Code | Article | Reference no. | Article Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| LIT01 | Bambale, A.J. Relationship between servant leadership and organizational citizenship behaviors: Review of literature and future research directions. J. Mark. Manag. 2014, 5, 1–16. | [69] | Literature review |

| LIT02 | Berger, T.A. Servant leadership 2.0: A call for strong theory. Sociol. Viewpoints 2014, 30, 146–167. | [39] | Literature review |

| LIT03 | Crippen, C. Servant-leadership as an effective model for educational leadership and management: First to serve, then to lead. Manag. Educ. 2004, 18, 11–17. | [40] | Literature review |

| LIT04 | Duff, A.J. Performance management coaching: Servant leadership and gender implications. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2013, 34, 204–221. | [112] | Literature review |

| LIT05 | Edwards, T. A content and contextual comparison of contemporary leadership approaches with specific reference to ethical and servant leadership: An imperative for service delivery and good governance. J. Christ. Scholarsh. 2010, 93–109. | [53] | Literature review |

| LIT06 | Eicher-Catt, D. The myth of servant-leadership: A feminist perspective. Women Lang. 2005, 28, 17–25. | [113] | Literature review |

| LIT07 | Finley, S. Servant leadership: A literature review. Rev. Manag. Innov. Creat. 2012, 5, 135–144. | [44] | Literature review |

| LIT08 | Flint, B.; Grayce, M. Servant leadership: History, a conceptual model, multicultural fit, and the servant leadership solution for continuous improvement. Collect. Effic. Interdiscip. Perspect. Int. Leadersh. 2013, 20, 59–72. | [35] | Literature review |

| LIT09 | Gupta, S. Serving the bottom of pyramid: A servant leadership perspective. J. Leadership, Account. Ethics 2013, 10, 98–107. | [114] | Literature review |

| LIT11 | Kincaid, M. Building corporate social responsibility through servant-leadership. Int. J. Leadersh. Stud. 2012, 7, 151–171. | [42] | Literature review |

| LIT12 | Parris, D.L.; Peachey, J.W. A systematic literature review of servant leadership theory in organizational contexts. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 113, 377–393. | [25] | Literature review |

| LIT13 | Rai, R.; Prakash, A.A relationship perspective to knowledge creation: Role of servant leadership. J. Leadersh. Stud. 2012, 6, 61–85. | [55] | Literature review |

| LIT14 | Ruíz, P.; Martínez, R.; Rodrigo, J. Intra-organizational social capital in business organizations: A theoretical model with a focus on servant leadership as antecedent. Ramon Llull J. Appl. Ethics 2010, 43–59. | [115] | Literature review |

| LIT15 | Russell, R.F.; Stone, A.G. A review of servant leadership attributes: Developing a practical model. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2002, 23, 145–157. | [31] | Literature review |

| LIT16 | Russell, R.F. The role of values in servant leadership. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2001, 22, 76–83. | [51] | Literature review |

| LIT17 | Searle, T.P.; Barbuto, J.E. Servant leadership, hope, and organizational virtuousness: A framework exploring positive micro and macro behaviors and performance impact. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2011, 18, 107–117. | [67] | Literature review |

| LIT18 | Sendjaya, S.; Sarros, J.C. Servant leadership: Its origin, development, and application in organizations. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2002, 9, 57–64. | [61] | Literature review |

| LIT19 | Spears, L.C. Character and servant leadership: Ten characteristics of effective, caring leaders. J. Virtues Leadersh. 2010, 1, 25–30. | [17] | Literature review |

| LIT20 | Stone, A.G.; Russell, R.F.; Patterson, K. Transformational versus servant leadership: A difference in leader focus. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2004, 25, 349–361. | [19] | Literature review |

| LIT21 | Sun, P.Y.T. The servant identity: Influences on the cognition and behavior of servant leaders. Leadersh. Q. 2013, 24, 544–557. | [38] | Literature review |

| LIT22 | Van Dierendonck, D. Servant leadership: A review and synthesis. J. Manage. 2011, 37, 1228–1261. | [18] | Literature review |

| LIT23 | Van Dierendonck, D.; Patterson, K. Compassionate love as a cornerstone of servant leadership: An integration of previous theorizing and research. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 128, 119–131. | [36] | Literature review |

| LIT24 | Waterman, H. Principles of servant leadership and how they can enhance practice. Nurs. Manage. 2011, 17, 24–26. | [116] | Literature review |

| LIT25 | Weinstein, R.B. Servant leadership and public administration: Solving the public sector financial problems through service. J. Manag. Policy Pract. 2013, 14, 84–92. | [117] | Literature review |

| MIXED01 | Beck, C.D. Antecedents of servant leadership: A mixed methods study. Communication 2014, 21, 144. | [47] | Mixed-method |

| MIXED02 | Melchar, D.E.; Bosco, S.M. Achieving high organization performance through servant leadership. J. Bus. 2010, 9, 74–88. | [50] | Mixed-method |

| MIXED03 | Sendjaya, S.; Sarros, J.C.; Santora, J.C. Defining and measuring servant leadership behaviour in organizations. J. Manag. Stud. 2008, 45, 402–424. | [24] | Mixed-method |

| QAL01 | Carter, D.; Baghurst, T. The influence of servant leadership on restaurant employee engagement. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 124, 453–464. | [59] | Qualitative |

| QAL02 | Jones, D. Does servant leadership lead to greater customer focus and employee satisfaction? Bus. Stud. J. 2012, 4, 21–36. | [45] | Qualitative |

| QAL04 | Savage-Austin, A.R.; Honeycutt, A. Servant leadership: A phenomenological study of practices, experiences, organizational effectiveness, and barriers. J. Bus. Econ. Res. 2011, 9, 49–54. | [66] | Qualitative |

| QAL05 | Sturm, B.A. Principles of servant-leadership in community health nursing. Home Heal. Care Manag. Pract. 2009, 21, 82–89. | [83] | Qualitative |

| QAL07 | Humphreys, H.J. Contextual implications for transformational and servant leadership: A historical investigation. Manag. Decis. 2005, 43, 1410–1431. | [54] | Qualitative |

| QNT01 | Babakus, E.; Yavas, U.; Ashill, N. Service worker burnout and turnover intentions: Roles of person-job fit, servant leadership, and customer orientation. Serv. Mark. Q. 2011, 32, 17–31. | [110] | Quantitative |

| QNT02 | Bakar, H.A.; McCann, R.M. The mediating effect of leader–member dyadic communication style agreement on the relationship between servant leadership and group-level organizational citizenship behavior. Manag. Commun. Q. 2015, 1–27. | [87] | Quantitative |

| QNT03 | Barbuto, J.E.; Gottfredson, R.K.; Searle, T.P. An examination of emotional intelligence as an antecedent of servant leadership. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2014, 21, 315–323. | [20] | Quantitative |

| QNT04 | Barbuto, J.E.; Wheeler, D.W. Scale development and construct clarification of servant leadership. Gr. Organ. Manag. 2006, 31, 300–326. | [41] | Quantitative |

| QNT05 | Bobbio, A.; van Dierendonck, D.; Manganelli, A.M. Servant leadership in Italy and its relation to organizational variables. Leadership 2012, 8, 229–243. | [7] | Quantitative |

| QNT06 | Chatbury, A.; Beaty, D.; Kriek, H.S. Servant leadership, trust and implications for the base-of-the-pyramid segment in South Africa. South African J. Bus. Manag. 2011, 42, 57–62. | [68] | Quantitative |

| QNT07 | Chen, C.; Chen, C.V.; Li, C. The Influence of leader’s spiritual values of servant leadership on employee motivational autonomy and eudaemonic well-Being. J. Relig. Health 2013, 52, 418–438. | [118] | Quantitative |

| QNT08 | Chen, Z.; Zhu, J.; Zhou, M. How does a servant leader fuel the service fire? A multilevel model of servant leadership, individual self identity, group competition climate, and customer service performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2015, 100, 511–521. | [86] | Quantitative |

| QNT09 | Chinomona, R.; Mashiloane, M.; Pooe, M.M.D. The influence of servant leadership on employee trust in a leader and commitment to the organization. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2013, 4, 405–414. | [11] | Quantitative |

| QNT10 | Choudhary, A.I.; Akhta, S.A.; Zaheer, A. Impact of transformational and servant leadership on organizational performance: A comparative analysis. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 116, 433–440. | [119] | Quantitative |

| QNT11 | Chung, J.Y.; Jung, C.S.; Kyle, G.T.; Petrick, J.F. Servant leadership and procedural justice in the U.S. national park service: The antecedents of job satisfaction. J. Park Recreat. Adm. 2010, 28, 1–15. | [82] | Quantitative |

| QNT12 | Dannhauser, Z.; Boshoff, A.B. Structural equivalence of the Barbuto and Wheeler (2006) servant leadership questionnaire on North American and South African samples. Int. J. Leadersh. Stud. 2007, 2, 148–168. | [120] | Quantitative |

| QNT13 | de Clercq, D.; Bouckenooghe, D.; Raja, U.; Matsyborska, G. Servant leadership and work engagement: the contigency effects of leader-follower social capital. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 2014, 25, 183–212. | [8] | Quantitative |

| QNT14 | de Sousa, M.J.C.; van Dierendonck, D. Servant leadership and engagement in a merge process under high uncertainty. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 2014, 27, 877–899. | [9] | Quantitative |

| QNT15 | Sousa, M.; van Dierendonck, D. Servant leadership and the effect of the interaction between humility, action, and hierarchical power on follower engagement. J. Bus. Ethics 2015. | [10] | Quantitative |

| QNT16 | de Waal, A.; Sivro, M. The relation between servant leadership, organizational performance, and the high-performance organization framework. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2012, 19, 173–190. | [121] | Quantitative |

| QNT17 | Garber, J.S.; Madigan, E.A.; Click, E.R.; Fitzpatrick, J.J. Attitudes towards collaboration and servant leadership among nurses, physicians and residents. J. Interprof. Care 2009, 23, 331–340. | [122] | Quantitative |

| QNT18 | Hale, J.R.; Fields, D.L. Exploring servant leadership across cultures: a study of followers in ghana and the USA. Leadership 2007, 3, 397–417. | [48] | Quantitative |

| QNT19 | Hanse, J.J.; Harlin, U.; Jarebrant, C.; Ulin, K.; Winkel, J. The impact of servant leadership dimensions on leader-member exchange among health care professionals. J. Nurs. Manag. 2015, 1–7. | [22] | Quantitative |

| QNT20 | Hsiao, C.; Lee, Y.; Chen, W. The effect of servant leadership on customer value co-creation: A cross-level analysis of key mediating roles. Tour. Manag. 2015, 49, 45–57. | [78] | Quantitative |

| QNT21 | Hu, J.; Liden, R.C. Antecedents of team potency and team effectiveness: An examination of goal and process clarity and servant leadership. J. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 96, 851–862. | [60] | Quantitative |

| QNT22 | Hunter, E.M.; Neubert, M.J.; Perry, S.J.; Witt, L.A.; Penney, L.M.; Weinberger, E. Servant leaders inspire servant followers: Antecedents and outcomes for employees and the organization. Leadersh. Q. 2013, 24, 316–331. | [14] | Quantitative |

| QNT23 | Hwang, H.J.; Kang, M.; Youn, M. The influence of a leader’s servant leadership on employees’ perception of customers’ satisfaction with the service and employees’ perception of customers’ trust in the service firm: The moderating role of employees’ trust in the leader. J. Glob. Sch. Mark. Sci. 2014, 24, 65–76. | [64] | Quantitative |

| QNT24 | Jaramillo, F.; Bande, B.; Varela, J. Servant leadership and ethics: A dyadic examination of supervisor behaviors and salesperson perceptions. J. Pers. Sell. Sales Manag. 2015, 35, 108–124. | [13] | Quantitative |

| QNT25 | Jaramillo, F.; Grisaffe, D.B.; Chonko, L.B.; Roberts, J.A. Examining the impact of servant leadership on sales force performance. J. Pers. Sell. Sales Manag. 2009, 29, 257–275. | [12] | Quantitative |

| QNT26 | Jaramillo, F.; Grisaffe, D.B.; Chonko, L.B.; Roberts, J.A. Examining the impact of servant leadership on salesperson’s turnover intention. J. Pers. Sell. Sales Manag. 2009, 29, 351–366. | [123] | Quantitative |

| QNT27 | Kashyap, V.; Rangnekar, S. Servant leadership, employer brand perception, trust in leaders and turnover intentions: A sequential mediation model. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2014. | [15] | Quantitative |

| QNT28 | Khan, K.E.; Khan, S.E.; Chaudhry, A.G. Impact of servant leadership on workplace spirituality: Moderating role of onvolvement culture. Pak. J. Sci. 2015, 67, 109–113. | [124] | Quantitative |

| QNT29 | Liden, R.C.; Wayne, S.J.; Zhao, H.; Henderson, D. Servant leadership: Development of a multidimensional measure and multi-level assessment. Leadersh. Q. 2008, 19, 161–177. | [43] | Quantitative |

| QNT30 | Liden, R.C.; Wayne, S.J.; Liao, C.; Meuser, J.D. Servant leadership and serving culture: Influence on individual and unit performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2014, 57, 1434–1452. | [23] | Quantitative |

| QNT31 | Liu, B.; Hu, W.; Cheng, Y. From the west to the east: Validating servant leadership in the Chinese public sector. Public Pers. Manage. 2015, 44, 25–45. | [125] | Quantitative |

| QNT32 | Mehta, S.; Pillay, R. Revisiting servant leadership: An empirical in Indian context. J. Contemp. Manag. Res. 2011, 5, 24–41. | [49] | Quantitative |

| QNT33 | Mertel, T.; Brill, C. What every leader ought to know about becoming a servant leader. Ind. Commer. Train. 2015, 47, 228–235. | [37] | Quantitative |

| QNT34 | Miao, Q.; Newman, A.; Schwarz, G.; Xu, L. Servant leadership, trust, and the organizational commitment of public sector employees in China. Public Adm. 2014, 92, 727–743. | [81] | Quantitative |

| QNT35 | Mittal, R.; Dorfman, P.W. Servant leadership across cultures. J. World Bus. 2012, 47, 555–570. | [63] | Quantitative |

| QNT36 | Neubert, M.J.; Kacmar, K.M.; Carlson, D.S.; Chonko, L.B.; Roberts, J.A. Regulatory focus as a mediator of the influence of initiating structure and servant leadership on employee behavior. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 1220–1233. | [52] | Quantitative |

| QNT37 | Newman, A.; Schwarz, G.; Cooper, B.; Sendjaya, S. How servant leadership influences organizational citizenship behavior: The roles of LMX, empowerment, and proactive personality. J. Bus. Ethics 2015. | [75] | Quantitative |

| QNT38 | Ozyilmaz, A.; Cicek, S.S. How does servant leadership affect employee attitudes, behaviors, and psychological climates in a for-profit organizational context? J. Manag. Organ. 2015, 21, 263–290. | [6] | Quantitative |

| QNT39 | Panaccio, A.; Henderson, D.J.; Liden, R.C.; Wayne, S.J.; Cao, X. Toward an understanding of when and why wervant leadership accounts for employee extra-role behaviors. J. Bus. Psychol. 2014. | [76] | Quantitative |

| QNT40 | Pekerti, A.A.; Sendjaya, S. Exploring servant leadership across cultures: Comparative study in Australia and Indonesia. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2010, 21, 754–780. | [32] | Quantitative |

| QNT41 | Peterson, S.J.; Galvin, B.M.; Lange, D. CEO servant leadership: Exploring executive characteristics and firm performance. Pers. Psychol. 2012, 65, 565–596. | [126] | Quantitative |

| QNT42 | Rodríguez-Carvajal, R.; De Rivas, S.; Herrero, M.; Moreno-Jiménez, B.; Van Dierendonck, D. Leading people positively: Cross-cultural validation of the Servant Leadership Survey (SLS). Span. J. Psychol. 2014, 17, 1–13. | [127] | Quantitative |