Abstract

This study investigates the nature of the energy policy making process and policy priorities within the OECD in order to identify opportunities for improvement in these processes and to improve sustainability outcomes. The Qualitative Content Analysis methodology is used, investigating governance and energy policy making alongside energy policy goals and priorities within eight OECD nations. A congruous energy policy making process (policy cycle) is discovered across the assessed nations, including the responsible bodies for each stage of the policy cycle and the current energy policy priorities. A key weakness was identified as a disconnect between the early stages of the policy cycle, issue identification and policy tool formulation, and the latter stages of implementation and evaluation. This weakness has meant that the social aspects of sustainability goals have been less developed than environmental and economic aspects and a heavy burden has been placed on the evaluation phase, risking a break down in the policy cycle. An additional “policy design” stage is proposed including a sustainability evaluation process prior to decision making and implementation, in order to remedy these identified shortcomings.

1. Introduction

This paper focuses on energy policy: specifically, the addressing of the effects of climate change and the associated transition to a larger share of renewable energy (RE) based generation. This is an important challenge being faced by many governments around the world, and has been labeled by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) as one of the most significant being addressed by the international community [1].

The OECD incorporates 34 nations from around the world, from emerging countries through to the most advanced, with the mission of promoting policies that will improve the economic and social well-being of people and the goal of building a stronger, cleaner and fairer world. The OECD provides a forum in which governments can work together to share experiences and seek solutions to common problems in order to understand what drives economic, social and environmental change [2].

This grouping of OECD nations with common policy goals and a desire to develop policy which can be sustainable, incorporating the three sustainability pillars of economy, society and environment provides a suitable basis for research, comparison and ultimately improvement of energy policy making processes leading to better sustainability outcomes. This is an important endeavor, as OECD nations account for approximately 41% of the world’s greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions as a result of energy use, with a GHG intensity per capita approximately 2.5 times that of the rest of the world [3].

OECD nations facing the challenges of climate change have adopted a broad range of energy policies and policy tools in order to shift to a more sustainable energy system and to reduce climate change impacts. The policy tools in place across the OECD in order to meet energy policy targets include feed-in tariffs (FiT), RE or Green Certificates (REC), tax concessions and a number of other market-based instruments. Energy policy targets themselves have changed over time, often with a change of government, and a general inconsistency in energy policy approach is apparent in the OECD, evidenced by the large number of strategic policies and tools which have been employed over time within member nations [4,5,6].

This inconsistency may be due (at least in part) to shortcomings or unsuitable approaches to energy policy making within the OECD [7,8,9], which may have led to the implementation of energy policies that were underdeveloped or poorly designed. Policy weaknesses are identified, and remediation begun post-evaluation, at the beginning of a new policy cycle. These approaches have led to less than optimal policy outcomes, not only in terms of the economy and environment but also with regard to the third pillar of sustainability: societal considerations. This is evidenced by the high level of income inequality in the OECD, and the fact that inequality has been prioritized as a social issue requiring improvement within OECD nations [2].

The aim of this research is to investigate and address these issues by: (1) identifying the nature of the energy policy making process and national sustainability priorities within the OECD; and (2) to identify any weaknesses with regard to sustainability outcomes inherent in these processes. Additionally, these findings will be adapted in order to propose a more robust energy policy making process which prioritizes policy design in order to smoothen the energy policy cycle and promote more sustainable outcomes.

In order to achieve these aims, eight OECD nations, consisting of four constitutional monarchies (Australia, The United Kingdom (UK), Canada and Japan) and four republics (the United States of America (USA), Greece, Chile and Mexico), are compared using a Qualitative Content Assessment (QCA, outlined in Section 3) process considering governance, the policy cycle steps and policy sustainability priorities. These nations are chosen because of their comparatively high income inequality (evidenced by their respective GINI coefficients) levels, suggesting that the social aspects of sustainability within their policy portfolios require additional attention in order to redress this issue.

Within this group of OECD nations, the hypotheses that the current energy policy development process lacks robustness and that policy mechanisms are poorly developed in order to achieve policy priorities is investigated utilizing QCA, seeking to identify firstly whether or not the policy development process is consistent within the OECD, and secondly, how energy policy tools are formulated, implemented and evaluated within this cycle, and how well this process contributes to sustainable energy policy outcomes.

2. Policy Making Theory

The description of a “policy cycle” dates back to 1956, initially proposed by Harold Laswell, incorporating the seven stages of intelligence, promotion, prescription, invocation, application, termination and appraisal [10]. These stages have largely stood the test of time in public policy theory, however is now generally agreed that appraisal follows application and that the overall process is cyclical and therefore excludes a “termination” phase. This may be because new policies are being developed in an already crowded policy environment, leading to policy succession rather than a wholesale replacement of policies already in place [11]. Additionally, the policy cycle is deliberately iterative, in that evolving policy issues are addressed by a prescribed set of tools and activities over a period of time [12].

Establishing that the policy making process is indeed cyclical and iterative, and includes discrete stages involving different actors and institutions in order to undertake deliberate problem solving [13], the order and nature of these discrete policy making stages requires investigation. There is general agreement across the available literature that the policy process begins with agenda setting (also called problem or issue identification) and ends with evaluation before beginning anew [10,13,14]. The steps undertaken in between usually only vary in their nomenclature or level of separation. Table 1 gives a general overview these steps and how they vary slightly dependent on the assessor’s choice of terms. A summary of approaches is given later in this study in Section 3.1, further reaffirming this commonality of steps and variety of granularity of nomenclature used across different nations.

Table 1.

Selected overview of policy cycle stages.

Each of the stages identified in Table 1 can subsequently be broken down into their constituent parts or sub-processes as follows.

Agenda setting or problem identification is the initial policy making step, and assumes the recognition of a policy problem. Although this stage of policy making is inherently political and not in the direct control of any single actor [10], it can occur in a bottom-up or top-down fashion, although it is unclear how successfully public opinion influences policy identification [15]. As there is limited capacity within society and political institutions to address all possible policy responses to identified policy problems, actors actively promote policy issues important to them in order to have them promoted to the policy agenda, and to remain prominent within the political debate [16].

Policy formulation, incorporating issue analysis includes the identification of policy proposals in order to resolve identified issues. This process occurs within government ministries, interest groups, legislative committees, special commissions and policy think tanks [15]. The policy formulation process precedes decision making, and is undertaken by policy experts who assess potential solutions and prepare them to be codified into legislation or regulation, along with initial analysis of feasibility, including but not limited to political acceptability and costs and benefits [17]. Policy experts are also responsible interacting with wider society, their policy networks and other social actors undertaking consultation in order to further shape policy proposals. Once a policy proposal (or proposals) has been formulated, it is presented to decision makers, usually cabinet, ministers and Parliament, for consideration prior to implementation [10].

Implementation is the phase at which all of the preceding planning activity is put into practice [14]. Resources are allocated, departmental responsibilities are assigned and often rules and regulations are developed by the bureaucracy in order to create new agencies with the role of translating laws into operational procedures [15]. The implementation phase is a technical process, whereby the “street-level” bureaucrats need to interpret guidance from central authorities whilst providing everyday problem solving strategies in order to ensure a successful implementation structure [18].

Evaluation is the final stage of the iterative policy cycle, and policy outcomes are tested against intended objectives and impacts. In addition, an evaluation is made to determine any unintended consequences of policies, in order to establish whether a policy should be terminated or redesigned according to shifting policy goals or newly identified issues [10]. The evaluation is undertaken by both governmental and societal actors in order to influence a reconceptualization of policy problems and solutions. This evaluation can be administrative (managerial and budgetary performance), judicial (judicial review and administrative discretion), or political (elections, think tanks, inquiries and legislative oversight), or a combination of the three in order to influence the direction and content of further iterations of the policy cycle [14].

Although we can establish a consensus on the requisite stages of the policy making process, through this review of policy making theory literature, it is important to recognize that in some cases, policy cycle stages may be compressed or skipped, or enacted out of order [14] and that deviations may occur within the proposed models [19]. This paper attempts to be responsive to the fluid nature of the policy cycle by formulating research questions broadly across the policy cycle stages and using an analysis method which thoroughly describes each stage, as well as responsible bodies, capturing similarities between nations and also accounting for outliers or any irregularities between nations and their policy practices and priorities—specific to the energy policy making process.

3. Methodology

The methodology chosen in this study to evaluate policy making processes and priorities in a sample of OECD countries is Qualitative Content Analysis (QCA), as it allows for an organized, systematic analysis of text in order to reveal common elements, themes and patterns within procedures, and to interpret and make observations of assessed, relevant data. QCA can assess a variety of social phenomena, and in the past has been used to assess economic growth [20], education [21], nursing research [22,23] and aesthetics [24], among others, suggesting its applicability to the investigation of energy policy.

In this study, QCA is used to assess governance systems, policy processes and priorities across 8 OECD nations. As data are readily available in the form of energy policy reports, academic papers and government publications, a deductive content analysis process is used [25] in order to assess key commonalities in the OECD policy development process and to discover any national peculiarities within these processes utilizing 12 focused research questions investigating governance, policy processes and policy priorities.

3.1. QCA Process Flow

In order to make a comparative analysis of governance, policy processes and priorities in the assessed nations, energy policy documentation (including policy targets, the development, implementation and review process) in the form of government documents and reports, third party and academic analysis is first collected and sorted by nation and type. In order to organize the data assessed and to identify similarities and any outliers, a structured categorization matrix is developed according to the key research questions to be clarified by this research.

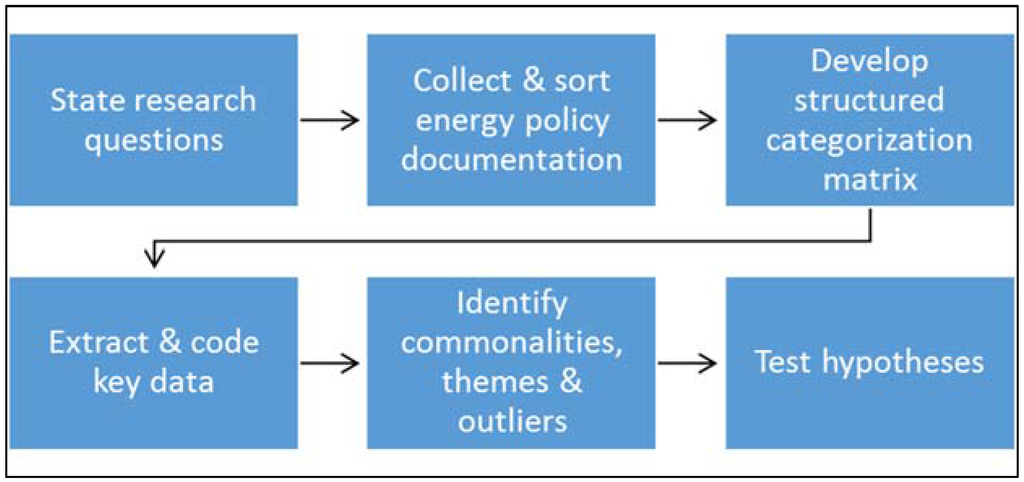

Data extracted in response to the research questions from the sorted energy policy documentation are then incorporated into the categorization matrix, from which data can then be coded and summarized, identifying common and outlying themes in order to test the hypotheses stated in the Introduction. This is often an iterative process as new themes can also be identified throughout the data extraction process [23]. A visual representation of the QCA process flow for this study is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

QCA Process Flow.

3.2. Research Questions

The key aim of the QCA process is to elicit the key factors of each evaluated nation’s policy making processes and governance structure and to identify policy priorities. These factors will be investigated through a series of research questions which are structured in order to derive conclusions which can assist in the development of a conceptual model of OECD governance, energy policy making processes and priorities. The questions are divided into two streams, the first of which assesses governance and policy making structures, and the second investigates the energy policy goals and sustainability priorities (across environmental, economic and social equity factors) within each nation.

3.2.1. Governance and Energy Policy Making

The first set of questions (Governance and energy policy making) aim to elicit the energy policy making processes and responsible national government bodies in each jurisdiction.

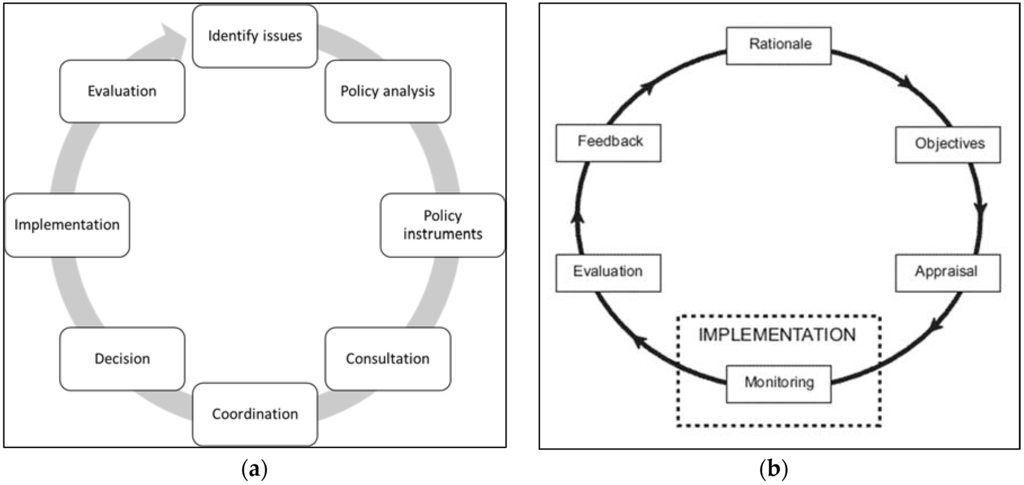

The questions are framed to identify the key national level governmental bodies which are responsible for the policy development process, and to elicit the key stages of policy making and how these are undertaken. The research questions identified in Table 2 are derived from theoretical approaches to policy making (discussed in detail in Section 2), which are broadly reflected in Australian, United Kingdom, United States and Provincial Canadian Policy Cycles, as shown in Figure 2.

Table 2.

Governance and energy policy making questions.

Figure 2.

Policy Cycles: (a) Australia [19]; (b) United Kingdom [26]; (c) United Stated of America [27]; and (d) Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada [28].

In each of these policy cycles there are key stages of policy development. Research Questions 1 to 6 seek to clarify each nations approach to policy making through a review of each of these steps in the RE policy making process. In order to capture data from non-identical policy cycles, terms for each of the steps (as described in Table 1 and Figure 2) are used interchangeably for each nation based on their individual cycles.

3.2.2. Energy Policy Goals and Priorities

The next set of questions (Energy policy goals and priorities) aims to elicit key energy policy goals across the nations and to assess policy implementation priorities, see Table 3.

Table 3.

Policy goal and priority questions.

The questions are framed in order to capture not only the stated energy policy goals in each nation, but also to understand how these goals are set and what mechanisms are enacted in order to achieve policy success. Alongside quantitative policy targets, the consideration and priority given to the environmental, economic and social equity aspects of energy policy sustainability are also assessed.

3.3. Evidence Assessed

The evidence assessed in order to answer the research questions is summarized in Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6 and comes from 3 sources: Government documentation, third party energy policy analysis and academic energy policy review papers.

Table 4.

Assessed government and supporting documents.

Table 5.

Third party legislation, policy and policy measure analysis documents.

Table 6.

Academic RE policy review papers.

3.3.1. Government Documents

For each of the eight nations, the RE legislation (Acts and laws), policy manuals and supporting Government based evidence is reviewed as summarized in Table 4.

3.3.2. Third Party Analysis

Three comprehensive, international publications were selected in order to evaluate each nation’s policies, legislation and policy measures on an even playing field, see Table 5.

3.3.3. Academic Papers

Academic policy review papers were selected based on their comprehensive analysis of national RE legislation and for the provision of a contrast of domestic and foreign RE policy approaches, not to introduce any new content, but in order to supplement and provide a check and balance for identified issues in the Government and third party analyses, where necessary, see Table 6.

In order to answer each research question comprehensively, documents are added according to identified need throughout the QCA process. Documents are given a reference number in order to streamline the referencing process in the categorization matrices. The method of data extraction varies from question to question but involves comprehensive literature review, keyword mining and examination of energy policy documents and iterations. No specialized computer programs are utilized, however some basic word search functions specific to proposed questions are used within electronic documents in order to assist the manual QCA and data extraction process. Official English translations of non-English evidence documents are used wherever possible, however, in some cases translations from external sources are used.

4. Results

4.1. Structured Categorization Matrices

Structured categorization matrices are developed, organizing the research questions being asked and the responses extracted from the sources considered for each of the eight OECD nations. The categorization matrices are populated according to the evidence reviewed across government, third party and academic literature for each nation. This manual process is time consuming and assesses copious amounts of literature, leading to large tables requiring summarizing and coding in order to be applied to the hypothesis and intended purpose of the study. The categorization matrices raw data are provided in Appendices A–D. Section 4.2 summarizes the results of this process and draws out key themes, similarities and identifies outliers.

4.2. Summary of Results

In order to condense the data identified in response to each of the research questions posed and to identify key themes, similarities and outlying factors, a secondary critical review of the data for each question is undertaken. The summary of the coding process (bringing together commonly occurring responses) outcomes are presented below for each research question in the form of key commonalities, outliers and a summary statement for each research question which considers all nations assessed. The results are separated into the two streams of governance and policy making in Table 7 and energy policy goals and considered factors in Table 8.

Table 7.

Governance and policy making QCA data summary.

Table 8.

Energy policy goals and considered factors QCA data summary.

4.2.1. Governance and Energy Policy Making Summary

In summary, with regard to governance, strong similarities were found throughout, firstly in the parliamentary and congress style systems, with a bill first introduced, followed by debate, approval and then assent by either a monarch or a president (usually a formality). In the case of the USA, presidential veto powers exist, however there is a check and balance for this veto power, in that a two-thirds majority of both houses can overturn it. In all nations but Chile, bills are introduced to the houses by members, usually from both parties. Only in Chile does the President have the sole authority to introduce bills and set the legislative agenda.

With regard to the identification of energy policy goals, in addition to each nation being a member of the OECD, they are also all members of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), participating in Conference of Party (COP) sessions. These memberships influence high level policy goals, however national policy goals are identified by the national Government party in power according to their priorities and enacted at both a national and state level. Only in the case of the USA and Canada are there no dedicated national level climate change or RE legislations and the states provide their own.

Energy policy tools are developed in the same way as goals, by the Government of the day, often within in the Cabinet or responsible ministries, enacted through national strategic plans and administered by responsible departments or in some cases statutory bodies. In the case of the USA and Canada, similar to goal setting, the federal and state level governments either share or separate responsibility.

The consultation step is similar in all cases. As each nation is a member of the UNFCCC and OECD, there is both international and national and state Government consultation. In addition, national Governments prescribe department or committee based stakeholder engagement and consultation responsibilities.

Responsibility for implementation of policies, including the application of laws and meeting of targets is usually the responsibility of federal ministries and departments (except in the USA and Canada where these are shared between federal and state departments and ministries). The administration of market instruments is the responsibility of regulators and independent bodies.

The evaluation of energy policy is undertaken following implementation in all cases, either through departmental monitoring, reporting or status report and official review based reporting. Each nation’s timeline for evaluation varies, with the most regular occurring annually, the most irregular every four years, with others falling somewhere in between or using non-specific evaluation timelines.

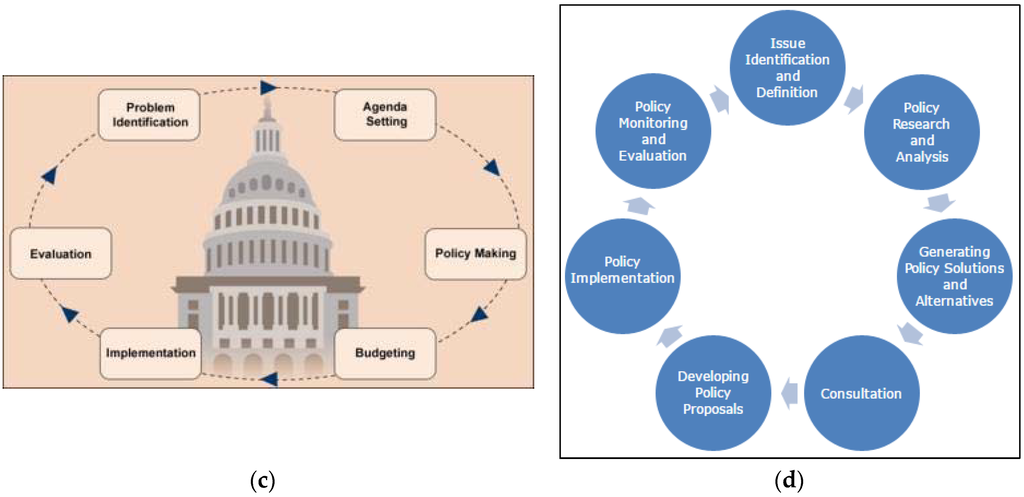

The QCA process has identified some key commonalities among the assessed nations, as well as some notable outliers. Figure 3 codifies the findings for the policy making process with governance and policy making step commonalities and outliers labeled throughout.

Figure 3.

OECD governance and policy making process (sub-steps in parentheses).

Generally speaking, the process is congruous throughout the assessed nations with some minor differences, particularly the lack of federal direction for the USA and Canada at the issue identification stage and shared state and federal responsibility for policy formulation (including tool development) and implementation. Evaluation timelines vary from nation to nation but in all cases occurs post-implementation. The policy making approach is similar in all cases assessed, and therefore each assessed nation can benefit from an improved process which can address any identified weaknesses.

4.2.2. Energy Policy Goals and Priorities Summary

Across all nations assessed (the states in the case of the USA and Canada), the current energy policy goals are an increase in RE based electricity generation and a reduction in GHG emissions. Japan is a special case, specifically mentioning increased energy self-sufficiency as an energy policy goal. In order to achieve these goals, some nations favor specific technologies at various scales.

Although each nation is unique in their approach to setting energy policy goals, generally speaking the federal Government sets the overall targets through parliamentary/congress based debate or at a party (or presidential) platform level. Goals are formalized through different documents including strategies, action plans, Acts and laws or transnational agreements. State based targets are often in line with national level targets (aspirational or concrete).

The tools in place to achieve energy policy goals are in all cases economically based, including FiTs, incentive payments, a form of REC or Renewable Portfolio Standard (RPS), tax or depreciation concessions and monetary non-compliance penalties. Some nations administer carbon markets or cap and trade type systems. Each of the assessed nation uses a different combination of these economic tools.

With regard to an assessment of the sustainability priorities of energy policies across the assessed nations, it is clear that environmental considerations are recognized and incorporated above all others into policy goals. All nations recognize the environmental issue of climate change (to varying degrees) and clearly identify the need for a reduction in greenhouse gases and a transition to RE sources. In the case of economic considerations, economic development is specifically identified as a central tenet of energy policy goals and nations describe the encouragement of investment in RE as a priority, through a variety of market instruments and in some cases selective prioritization of certain RE sources. Sustainable economic growth, energy security and low or reduced energy prices are identified as priorities. In line with the economic goals, social equity is also considered broadly by all nations. The nature of this consideration varies vastly from nation to nation, ranging from a general consideration of social issues when developing energy policy, up to specific identification of disadvantaged groups and the need for targeted support. Intergenerational equity and the need to reduce public and future burden were particularly prominent among the nations assessed.

Bringing together all aspects of the energy policy QCA undertaken in this study, Table 9 summarizes the discovered OECD policy cycle stages from Figure 3, along with the identified key governance bodies and the priorities expressed at each stage of the energy making policy cycle.

Table 9.

Summary of policy cycle, governance, priorities and sustainability factor priority.

5. Discussion—Identified Issues and Implications for Policy Making

Through an assessment of energy policy development and the process followed in eight OECD nations, some inconsistencies are brought to the fore. The most striking of these inconsistencies is the apparent misalignment of energy policy tools with energy policy goals, particularly with regard to the social aspects of sustainability. From the summary of the QCA process undertaken, provided in Table 9, there is a clear disconnect between issue identification, policy formulation (tool selection and target setting) and the latter steps through to evaluation. The qualitative targets proposed are all based on an increase in the share of RE generation and environmental improvement, with no quantitative targets in place to address the social implications of energy policies in any of the nations assessed. The policy tools used reinforce this issue, with only economic tools specified, rewarding only the RE generators who are not bound in any way to reduce potential impacts on society. Although energy policy documents qualitatively mention ideals with regard to society and fairness, no check, balance or policy tool is in place to realize these aspirational goals in any of the nations assessed. The QCA process also identified that the social factors of sustainability are prioritized below environmental and economic considerations at all stages of the energy policy making cycle.

As all nations assessed are members of the OECD, the fact that income inequality is at its highest level for the past half century [2], provides a platform for the prioritization of this issue. Indeed, the OECD specifically encourages member nations to design policy packages to tackle high inequality and promote opportunities for all, and warns that high wealth concentration limits investment opportunities [59]—linking the social and economic aspects of sustainability within policy making and priority setting.

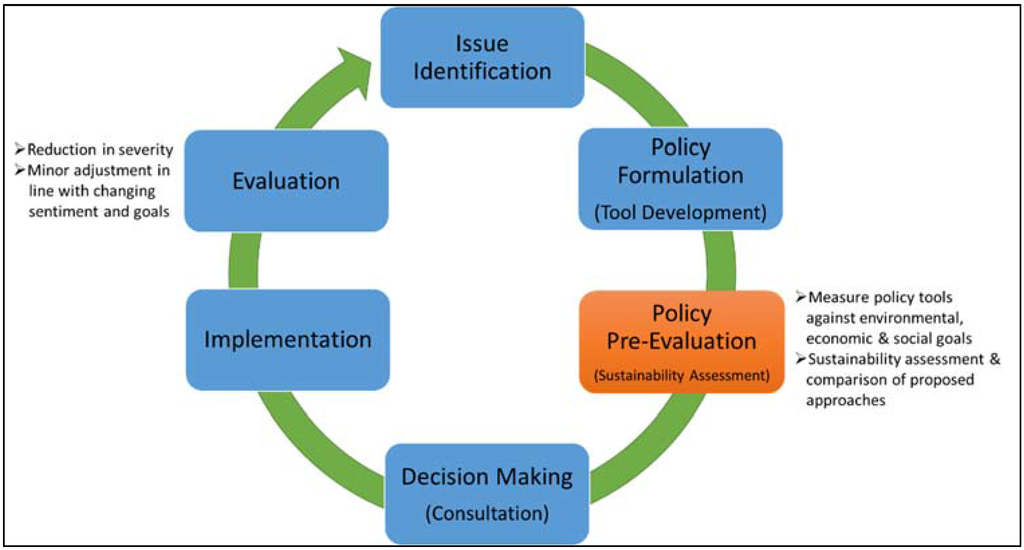

In order to improve the policy making process and to align policy goals with policy tools and desired sustainability outcomes, the QCA evaluation of policy making in this study has identified the opportunity for the introduction of a “policy pre-evaluation” phase, in which different policy tools can be measured against not only environmental and economic goals but also from a social impact point of view. A specific sub step of this phase would be the introduction of a “sustainability evaluation” in order that economic, environmental and social equity impacts of a given policy (or several alternatives) can be measured against nationally desirable targets in order to achieve the economic and environmental goals and to meaningfully incorporate the identified social equity ideals specific to each nation. This early, pre-implementation evaluation phase will enable policies to meet sustainability goals to a higher degree than is currently experienced, and will also improve the policy making process such that post-implementation evaluation can be reduced in severity, and to avoid policy termination in preference for radically different policy approaches, allowing the final evaluation to focus on balance, in order to re-align energy policies with changing national level goals or shifting national sentiment and to maintain energy policy sustainability.

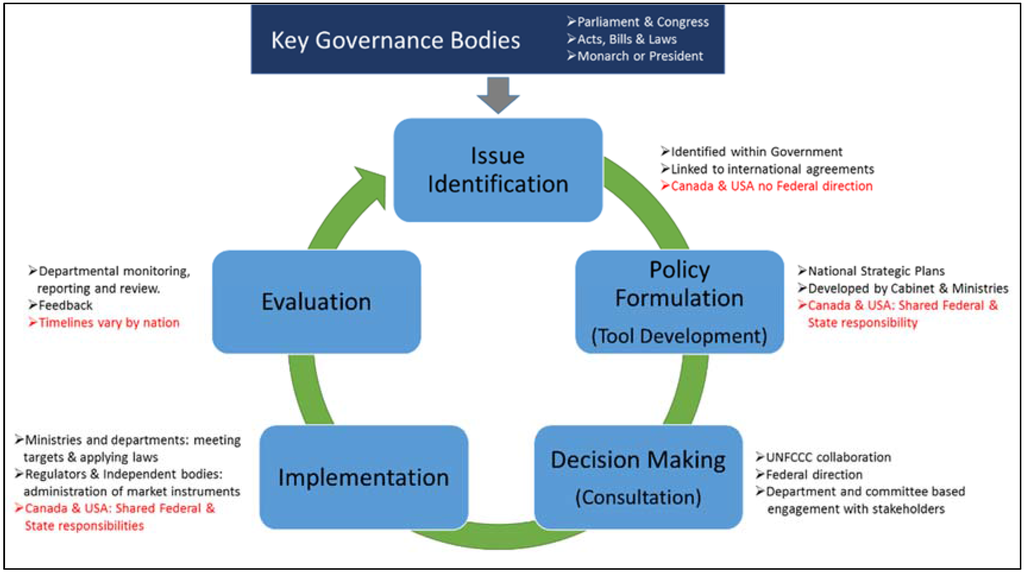

Figure 4 outlines this proposed refinement to the existing process, specific to energy policy making within the assessed nations.

Figure 4.

Revised energy policy making process.

An additional stage entitled policy pre-evaluation is added to the energy policy cycle, in which a sustainability assessment of policy tools considering national environmental, economic and social goals is made, prior to decision making. This assessment prioritizes energy policy sustainability, and allows current economic approaches and prioritized technologies within the energy system to be tested against the abovementioned sustainability factors in order to derive policies that can best achieve goals in the most sustainable way.

The reason for the introduction of a separate step is twofold: firstly, the separation of policy formulation and policy design draws attention to the need for sustainability evaluation prior to decision making and implementation. Secondly, by introducing a distinct policy design step in the policy cycle, specific expertise can be allocated to it, if this expertise cannot be found within the current bureaucracy.

6. Conclusions

In this study, eight unique nations, representative of constitutional monarchies, republics, parliamentary and congress style governance systems and each with high income equality within the OECD were evaluated through a QCA process assessing governance, policy processes, goals and sustainability priorities.

The hypotheses proposed by this research asked two questions: (1) whether the energy policy development process is consistent across the eight nations assessed within the OECD; and (2) whether this policy making process lacked robustness, and policy mechanisms are poorly designed in order to achieve sustainability goals.

Through the evaluation conducted, both hypotheses were shown to be true for the 8 OECD nations investigated, a fundamentally congruous “OECD policy making process” was identified, in both the nature of the policy cycle, policy goals and the variety of (exclusively) economic tools used to achieve them, as outlined in Section 4.2 and summarized in Figure 3. Secondly, building on these findings, it was further identified that policy processes in all assessed nations showed similar weaknesses. These were identified as the misalignment of policy tools and policy goals from a sustainability point of view, and a lack of policy focus on OECD identified important social issues such as inequality, in spite of the income disparity found in the assessed nations.

Based on the findings of this study, a proposed remedy is suggested: the addition of a discrete “policy pre-evaluation” phase in the newly identified OECD policy cycle, as shown in Figure 4. This proposed revision is an important one because it not only addresses the identified shortcomings of current practice, but provides an evidence base for the improvement of policy making within the OECD through better policy design and improved sustainability outcomes resultant from energy policy implementation, particularly with regard to the social aspects of sustainability, and the incorporation of non-economically based policy mechanisms.

This study has sought to build on existing policy making theory and to apply it to an analysis of energy policy making processes, for the purpose of improving sustainability outcomes from an economic, environmental and the largely overlooked or undervalued social point of view. Future challenges for sustainable energy policy development within the OECD include the establishment of a policy design specific sustainability evaluation process which can help to guide the development of sustainable energy policy in a user friendly manner for the policy maker, and to assess its impact on the energy policy cycle and the effectiveness of this process in addressing identified OECD social issues and sustainability goals.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at http://www.mdpi.com/2076-3387/6/3/9/s1.

Author Contributions

The research was designed by all authors. The analysis and writing of the paper was undertaken by the main author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- OECD. Aligning Policies for a Low-Carbon Economy; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Inequality: Inequality and Income, about the OECD: Our Mission. 2016. Available online: http://www.oecd.org (accessed on 3 February 2016).

- IEA. CO2 Emissions from Fuel Combustion 2012; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- IEA; IRENA. Global Renewable Energy. IEA/IRENA Joint Policies and Measures Database. 2016. Available online: http://www.iea.org/policiesandmeasures/renewableenergy (accessed on 29 April 2016).

- London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE). 2015 Global Climate Legislation Study. 2015. Available online: http://www.lse.ac.uk/GranthamInstitute/publication/2015-global-climate-legislation-study (accessed on 29 April 2016).

- IEA. Energy Policies of IEA Countries. 2012–2015. Available online: http://www.iea.org/publications/countryreviews (accessed on 29 April 2016).

- Chapman, A.; McLellan, B.; Tezuka, T. Residential solar PV policy: An analysis of impacts, successes and failures in the Australian case. Renew. Energy 2016, 86, 1265–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mundaca, T. Climate change and energy policy in Chile: Up in smoke? Energy Policy 2013, 52, 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, W.; Lunnan, A. The Role of Governments in Renewable Energy: The Importance of Policy Consistency. Biomass Bioenergy 2013, 57, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jann, W.; Wegrich, K. Theories of the Policy Cycle. In Handbook of Public Policy Analysis: Theory, Politics, and Methods; Fischer, F., Miller, G.J., Sidney, M.S., Eds.; CRC Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 43–62. [Google Scholar]

- Hogwood, B.; Peters, G.B. Policy Dynamics; Wheatsheaf Books: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, B. Revisiting the Policy Cycle; Association of Tertiary Education Management, Developing Policy in Tertiary Institutions, Northern Metropolitan Institute of TAFE: Melbourne, Australia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, C. The policy cycle: A model of post-Machiavellian policy making? Aust. J. Public Adm. 2005, 64, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howlett, M.; Ramesh, M. Studying Public Policy: Policy Cycles and Policy Subsystems, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: Don Mills, ON, Canada, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Dye, T. Understanding Public Policy, 12th ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Birkland, T. Agenda Setting in Public Policy. In Handbook of Public Policy Analysis: Theory, Politics, and Methods; Fischer, F., Miller, G.J., Sidney, M.S., Eds.; CRC Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 63–78. [Google Scholar]

- Sidney, M. Policy Formulation: Design and Tools. In Handbook of Public Policy Analysis: Theory, Politics, and Methods; Fischer, F., Miller, G.J., Sidney, M.S., Eds.; CRC Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 89–107. [Google Scholar]

- Pulzl, H.; Treib, O. Implementing Public Policy. In Handbook of Public Policy Analysis: Theory, Politics, and Methods; Fischer, F., Miller, G.J., Sidney, M.S., Eds.; CRC Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 79–87. [Google Scholar]

- Althaus, C.; Bridgman, P.; Davis, G. The Australian Policy Handbook, 5th ed.; Allen & Unwin: Sydney, Australia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Haapanen, L.; Tapio, P. Economic growth as phenomenon, institution and ideology: A qualitative content analysis of the 21st century growth critique. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 3492–3503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerbic, P.; Stacey, E. A purposive approach to content analysis: Designing analytical frameworks. Internet High. Educ. 2005, 8, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graneheim, U.; Lundman, B. A purposive approach to content analysis: Designing analytical frameworks. Nurse Educ. Today 2004, 24, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elo, S.; Kyngas, H. The qualitative content analysis process. J. Adv. Nurs. 2007, 62, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, J.Y.; Lee, E. Reducing Confusion about Grounded Theory and Qualitative Content Analysis: Similarities and Differences. Qual. Rep. 2014, 19, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, C.; Rossman, G. Designing Qualitative Research; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- HM Treasury. The Green Book: Appraisal and Evaluation in Central Government; HM Government Printer: London, UK, 2011.

- The University of Texas at Austin. The Public Policy Process. 2016. Available online: http://www.laits.utexas.edu/gov310/PEP/policy/index.html (accessed on 2 April 2016). [Google Scholar]

- Government of Newfoundland and Labrador. The Policy Cycle. In PolicyNL; 2016. Available online: http://www.policynl.ca/policydevelopment/policycycle.html (accessed on 3 April 2016). [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. National Action Plans. United Kingdom and Greece. 2016. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/energy/en/topics/renewable-energy/national-action-plans (accessed on 4 April 2016).

- The National Archives, HM Government. Energy Act 2013. 2013. Available online: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2013/32/pdfs/ukpga_20130032_en.pdf (accessed on 4 April 2016). [Google Scholar]

- HM Government. The Coalition: Our Programme for Government; Cabinet Office: London, UK, 2010.

- Australian Government. Federal Register of Legislation: Renewable Energy (Electricity) Act 2000; Australian Government: Canberra, Australia, 2016.

- Australian Government, Department of the Environment. The Renewable Energy Target (RET) Scheme. 2016. Available online: https://www.environment.gov.au/climate-change/renewable-energy-target-scheme (accessed on 5 April 2016). [Google Scholar]

- Australian Government, Department of Industry and Science. 2015 Energy White Paper; Commonwealth of Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2015.

- Australian Government, Clean Energy Regulator. Renewable Energy Target: How the Scheme Works, History of the Scheme. 2015. Available online: http://www.cleanenergyregulator.gov.au/RET/About-the-Renewable-Energy-Target/How-the-scheme-works (accessed on 5 April 2016). [Google Scholar]

- British Columbian Government. Clean Energy Act 2010; Queen’s Printer: Victoria, BC, Canada, 2013.

- Independent Electricity System Operator. Ontario FIT Program. 2009. Available online: http://fit.powerauthority.on.ca (accessed on 4 April 2016).

- Government of Quebec. Quebec and Climate Change. A Challenge for the Future; 2016–2012 Action Plan; Bibliotheque Nationale du Quebec: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2008.

- Japanese Government, Ministry of Economy Trade and Industry. Strategic Energy Plan. April 2014. Available online: http://www.enecho.meti.go.jp/en/category/others/basic_plan/pdf/4th_strategic_energy_plan.pdf (accessed on 13 April 2016). [Google Scholar]

- Japanese Government, Ministry of Economy Trade and Industry. Long-Term Energy Supply and Demand Outlook. July 2015. Available online: http://www.meti.go.jp/english/press/2015/pdf/0716_01a.pdf (accessed on 13 April 2016). [Google Scholar]

- The Library of Congress. Energy Policy Act of 1992—Title XII—Renewable Energy. 2016. Available online: http://thomas.loc.gov (accessed on 24 April 2016). [Google Scholar]

- Executive Office of the President. The Presidents Climate Action Plan; The White House: Washington, DC, USA, 2013.

- Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Clean Power Plan. 2015. Available online: http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2015-10-23/pdf/2015-22842.pdf (accessed on 23 April 2016). [Google Scholar]

- Mexican Government. Official Journal of the Federation: Energy Transition Law 2015. Available online: http://dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=5421295 (accessed on 17 April 2016).

- Bloomberg. Mexico Passes Law Encouraging Renewables Investment. International Environment Reporter. 15 December 2015. Available online: http://www.bna.com/mexico-passes-law-n57982065128 (accessed on 17 April 2016).

- Brookings Institution. Mexico’s Energy Reforms Become Law. 2014. Available online: www.brookings.edu/research/articles/2014/08/14-mexico-energy-law-negroponte (accessed on 17 April 2016).

- Government of Chile, Ministry of Energy. Law No. 20.257 on Non-Conventional Renewable Energies. 2016. Available online: http://antiguo.minenergia.cl/minwww/opencms/08_Normativas/02_energias/renovables.html (accessed on 1 May 2016). [Google Scholar]

- Government of Chile, National Energy Commission. Non-Conventional Renewable Energy in the Chilean Electricity Market; ByB Impresores: Santiago, Chile, 2009.

- Government of Chile, Library of Congress. Law No. 20.571 Regulating the Payment of Electricity Tariffs of Residential Generators. 2012. Available online: http://www.leychile.cl/Navegar?idNorma=1038211 (accessed on 1 May 2016). [Google Scholar]

- Government of Chile, Ministry of Energy. National Energy Strategy 2012–2030. 2012. Available online: http://www.centralenergia.cl/uploads/2012/06/National-Energy-Strategy-Chile.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2016). [Google Scholar]

- IRENA. Renewable Energy in Latin America 2015: An Overview of Policies; IRENA: Abu Dhabi, UAE, 2015.

- Government of Greece, Ministry of Environment and Energy. Law 3851/2020: Accelerating the development of Renewable Energy Sources to Deal with Climate Change and Other Regulations Addressing Issues under the Authority of the Ministry of Environment, Energy and Climate Change. 2010. Available online: http://www.ypeka.gr/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=qtiW90JJLYs%3D&tabid=37 (accessed on 23 March 2016). [Google Scholar]

- Keay, M. UK energy policy—Stuck in ideological limbo? Energy Policy 2016, 94, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, G.; Clifton, J. Picking winners and policy uncertainty: Stakeholder perceptions of Australia’s Renewable Energy Target. Renew. Energy 2014, 67, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEEJ. Special Article—Inside Japan’s Long-Term Energy Policy. 2015. Available online: http://eneken.ieej.or.jp/data/6291.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2016).

- Elliott, E.D. Why the United States Does Not Have a Renewable Energy Policy. Environ. Law Rep. 2013, 43, 10095–10101. [Google Scholar]

- Alemán-Nava, G.; Casiano-Flores, V.; Cárdenas-Chávez, D.; Díaz-Chavez, R.; Scarlat, N.; Mahlknecht, J.; Parra, R. Renewable energy research progress in Mexico: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 32, 140–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondol, J.; Koumpetsos, N. Overview of challenges, prospects, environmental impacts and policies for renewable energy and sustainable development in Greece. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 23, 431–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. In It Together: Why Less Inequality Benefits All (Summary); OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).