Abstract

This study empirically investigated how small and medium-sized Chinese apparel enterprises (SME) formed their strategy as a response to the characteristics of business environment in order to achieve competitive business performance. An environment-strategy-performance model was proposed and tested. Using primary data gathered by a questionnaire survey of the Chinese apparel industry, factor analysis and structural equation modeling (SEM) were conducted for measurement and structural model analysis and hypothesis testing. Results show the proposed model met parsimonious statistical criteria. The differences in strategy responses to environment between high- and low-performing firms were striking. Confronting an increasingly turbulent business environment, high performers emphasized differentiation strategy through higher quality, better delivery performance, and greater flexibility than cost reduction. In contrast, low performers prioritized low cost while quality and flexibility were given certain weights. The lack of clear focus on strategies could result in a relatively lower performance. While the process of government-led industrial upgrading continues, forward-looking firms have proactively shifted their strategic focus from solely or mainly cost reduction to a variety of differentiating factors which bring in added value and are less imitable by competitors.

1. Introduction

In the past three decades, the Chinese apparel industry has achieved spectacular growth, capturing a significant share of global production and trade. By the end of 2012, the industry including textile sector accounted for some 18 percent of China’s manufacturing employment, 12 percent of China’s GDP, 14 percent of its manufacturing value added, and 17 percent of its total exports [1]. China has become the largest producer and supplier of fibers, yarns, fabrics, and apparel in both volume and value terms. Today, it supplies approximately 33 percent of textiles and 40 percent of apparel by value in the global market [2].

In moving from a self-sufficiency-based, centrally-planned system towards a commercially-driven, export oriented sector, the Chinese apparel industry experienced far-reaching changes. These profoundly affected the consumer needs, the product mix and distribution channels, and firm strategy and skill development [3]. As a result of these changes, Chinese firms have faced a dramatic escalation in the level of turbulence within their business environment. Against this backdrop, state-owned enterprises (SOEs), which were in the monopoly position, have radically declined. Meanwhile, the rise of private sector has fundamentally reshaped the contour of the industry and overtaken most output and export. Some estimates put the total number of private firms in the Chinese apparel industry at approximately 100,000. Of these, more than 80 percent are small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) [1]. Nowadays, the competitiveness of SMEs largely determines the growth of Chinese apparel industry [4]. The continued advancement of managerial skills and knowledge among SMEs plays a crucial role in achieving the national industry upgrading goal through transiting from original-equipment-manufacturer (OEM) which mainly competes on low cost to original-brand-manufacturer (OBM) and/or original-design-manufacturer (ODM) which focus on differentiation and added value.

Recognizing the increasing importance of SMEs in the national economy, China’s central government has implemented a variety of new laws recently to promote and foster the development of SMEs, such as the Detailed Procedures to Financing SMEs on International Market Expansion and Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Promotion of SMEs. Meanwhile, in the management literature, the scholarly works devoted to exploring the Chinese SMEs related subjects have been burgeoning [5,6,7]. However, most prior studies in the field are cross-industry analysis [7], and those textile and apparel specific studies are more qualitative in nature or mainly focus on trade or global sourcing issues [3,8]. There is very little empirically-based research developed to understanding strategic management issues in the industry, particularly for the SMEs [7], although it is stated that effective strategic management determines a firm’s long-term viability and competitiveness [5,9].

In an effort to address this gap in the literature, utilizing the primary data gathered from a questionnaire survey of Chinese apparel manufacturers, this paper aimed to fulfill the following objectives. First, based on literature review, an environment-strategy-performance conceptual model is proposed and the corresponding survey instrument is developed. Second, the environmental characteristics, as business contingency facing Chinese apparel SMEs, are statistically measured. Third, the strategy responses (reflected by competitive priorities) to the business environment among Chinese apparel SMEs are quantitatively determined. The differences between relatively high- and low-performing firms are revealed. Finally, through identifying the optimum match of strategy to environment, Chinese apparel SMEs may detect problems and adjust or redesign their strategic focus so as to achieve competitive performance, or perhaps, just to survive in today’s business environment.

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

Firms are in constant exchange with the environment in which they operate [10]. Business contingency literature suggests that high performing firms better fit their environment than those that showed relatively lower performance, and maximized the benefits of exchanges with the environment [10,11,12,13,14]. Although both business environment and strategy have been extensively researched as determinants of other managerial arrangements and consequences, given their ever-changing nature, there is continuous demand on theoretical advancement and empirical validation regarding the optimum configurations of firm strategies to a variety of environmental characteristics. Particularly, it is urged to extend the geographic coverage of environment-strategy-performance study to emerging economies such as China, India, and Brazil [13,15].

2.1. Business Contingency

The importance of understanding environmental characteristics as business contingency facing a firm has been evident in the management literature [10,13,16,17,18]. González-Benitoa et al. [13] stressed that consideration of environmental characteristics should be virtually built into all research designs in strategic and operations management. In general terms, business environment consists of the myriad of forces that are beyond the control of management in the short run, and thus pose threats as well as opportunities to firms [18,19,20].

Environmental dimensions are the underlying patterns recognized to evaluate and understand the concept of business environment in a systematic manner [15]. Mintzberg [21] proposed four dimensions that characterize the overall state of business environment: degree of diversity, complexity, dynamism, and munificence. Dess and Beard [22] used empirical methods and archival data, based primarily on transactions between firms and their environments to define three primary environmental dimensions as munificence, dynamism, and complexity. Sharfman and Dean [23] developed a comprehensive literature review and concluded there was a convergence in the literature supporting Mintzberg’s [21] and Dess and Beard’s [22] dimensional classification of environmental characteristics. The accountability and applicability of these dimensions have been further proven by a great number of empirical studies [12,13,14,17,24,25,26].

The degrees of complexity, diversity, dynamism, and munificence collectively measure the characteristics of business environment facing firms. They are held to be the most critical dimensions of business environment with respect to firm strategic decision-making [13,15,17,18]. Environmental complexity refers to the extent that firms are required to have a great deal of sophisticated knowledge about products, customers, or any others. Environmental diversity is reflected by the degree to which a firm is faced with homogenous or diffuse conditions [26]. Environmental dynamism is the rate of instability or turbulence in the environment, stemming from changes in technology, demand, competitive moves and so on [17,19]. Environmental munificence is the degree to which an environment supports the growth of firms within it, which relates to the level of competitive pressures in the environment as exemplified by the intensity of competition and the bargaining leverage applied on firms by buyers and suppliers. Munificence is often measured in a reverse scale as environmental hostility [14]. Chi [12] indicated that changes in environmental characteristics should be monitored by firms and reflected by effective adjustment in their strategy responses.

Business environment has been studied in terms of its perceived or objective states. Ward and Duray [20] argued that the objective reality of environment is relatively less important than the perceived environmental characteristics in the studies of strategic management. Even though the environment confronting firms within the same industry is generally similar, the environmental characteristics may be perceived dramatically differently from individual to individual [12,17,26]. Since firms’ responses are largely dictated by their perceptions of environment, these perceptions should be thoroughly studied and understood in order to determine and explain adaptive patterns across firms [20].

2.2. Strategy Responses

The acceptance and application of strategic approaches to manage manufacturing firms have experienced a continued growth. Since Skinner’s [27] early work in the field, a common thread in the management literature has been the need of firms for choosing among and achieving one or multiple key capabilities [20]. Consistent with the mainstream literature, the term competitive priority has been broadly used to describe firms’ choice of these competitive capabilities [9]. The preference of competitive priorities reflects the strategic orientation of a firm [28]. In spite of the differences in terminology [9,20,29,30,31], there is a general agreement in the literature that competitive priorities for manufacturing firms can be expressed in terms of low cost, quality, delivery performance (speed and reliability), and flexibility.

Although all manufacturers are concerned to some degree with cost, most do not compete solely or even primarily on low cost. Firms that emphasize cost as a competitive priority usually focus on lowering production costs, improving productivity, maximizing capacity utilization, and reducing inventories [20]. Manufacturing’s traditional observance of quality control reflects a focus on the conformance dimension of quality such as providing high performance design, offer consistent and reliable quality, and conformance to product design specification [31]. Delivery performance requires both reliability and speed [30]. Delivery reliability refers to the ability to deliver according to a promised schedule. Firms may not have the least costly or the highest quality product, but is able to compete on the basis of reliably delivering products as promised [9]. For some customers, delivery reliability alone is not good enough, delivery speed is also essential to win and retain the order. This is particularly evident among suppliers for fast fashion brands [32]. Although delivery reliability and speed are separable, long-run success requires that promises of speedy delivery be kept with a high degree of reliability [33]. Flexibility in manufacturing firms has traditionally been achieved at a high cost by using generic purpose machinery instead of more efficient special purpose-built machinery and by deploying more highly skilled workers than would otherwise be needed [20]. Advanced manufacturing technologies, when properly implemented, can reduce the cost of achieving flexibility. Each of these four competitive priorities must be given a weight by a firm that reflects the degree of emphasis required to achieve the overall goals at a corporate level [9]. The weights associated with each priority provide a broad measure of what a firm deems important at a particular time.

In an empirical study, Ward et al. [14] found that a quality, delivery performance, and/or flexibility emphasis aimed at building capabilities for product or service differentiation while a cost emphasis was not. It is consistent with the standpoint of Porter [34]. Porter [34] contended that a firm can achieve profitability over its competitors in some fundamentally different approaches to strategy, namely differentiation strategy, cost leadership strategy, and focus strategy. Differentiation strategy offers customers unique products or services that are differentiated in such a way that customers are willing to pay a price premium that exceeds the additional cost of the differentiation. In contrast, cost leadership strategy aims to provide an identical product or service at a lower cost. For focus strategy, it concentrates on a narrow segment and within that segment attempts to achieve either a cost advantage or differentiation. Furthermore, Porter [34] argued that a firm pursuing cost leadership and differentiation strategies simultaneously may be stuck in the middle, which almost guarantees low profitability. Notwithstanding Porter’s typology which has been widely applied by previous studies as generic strategies adopted by firms, it has been challenged by mixed empirical evidence. Some scholars highly embraced its applicability and accountability [20,35], while others claimed that the generic strategies are not necessary to be mutually exclusive and differentiation can lead to cost effectiveness [36,37]. In this study, competitive priorities expand Porter’s generic strategies into four constructs to better capture the content of a firm’s strategies.

As there is no single strategy that is applicable to all types of circumstances, the effectiveness of a strategy is contingent upon business environmental characteristics [31]. Ward et al. [14] found that higher environmental dynamism drives firms to put more emphasis on delivery performance, flexibility, and quality competitive priorities. Ward and Duray [20] revealed that successful manufacturing firms facing greater perceived environmental dynamism and hostility responded with a greater focus on delivery performance and flexibility to further differentiate their products rather than emphasize on cost reduction. Amoako-Gyampaha and Boye [38] demonstrated that greater complexity and hostility in business environment cause firms’ emphasis more on low cost, quality, flexibility, and delivery dependability strategies. This finding contradicts many other studies in firms’ positive responses of both low cost and differentiation strategies to more complex and hostile environments. More recently, Anand and Ward [24] indicated that a flexibility strategy is commonly chosen by firms in a more dynamic business environment. The empirical findings of Chi [9] showed that a quality strategy is important in any type of environment while flexibility and delivery performance strategies should be emphasized more in a turbulent environment, and a low cost strategy is more effective in a steady and predictable environment. Therefore, in this study, environmental turbulence (i.e., degrees of diversity, complexity, dynamism, and hostility) is considered as a precursor variable causally related to firm’s strategic choices. Hypotheses 1, 2, 3 and 4 are proposed to test the relationships between environmental characteristics and firm’s competitive priorities in the context of Chinese apparel SMEs.

H1:

There is a negative relationship between environmental turbulence and firm low cost strategy.

H2:

There is a positive relationship between environmental turbulence and firm quality strategy.

H3:

There is a positive relationship between environmental turbulence and firm delivery performance strategy.

H4:

There is a positive relationship between environmental turbulence and firm flexibility strategy.

2.3. Firm Business Performance

Although complete and accurate measurement of a firm’s business performance is still viewed as one of the challenges in the management research [39], largely, firm business performance is measured by financial metrics [13,20]. The commonly applied measures include return on asset (ROA, shows how profitable a company’s assets are in generating revenue), return on investment (ROI, shows how profitable a company’s capital investment is in generating revenue), market share, profit margin, and sales growth [12,14,20,30,40]. Due to lack of availability of published financial reports from the surveyed Chinese apparel SMEs, this study collected performance data based on senior executives’ perceptions of their firms’ performance in comparison to that of major competitors. Prior studies have showed that self-perceived firm performance by senior executives is effective in reflecting the performance of a firm [41], allows for assessment against competitors [42], and permits assessment of lagged effects of firm strategy or action [43].

Building on prior research, in this study, business performance of Chinese apparel SMEs is measured by the survey respondent’s perception of performance in relation to its competitors. The measures used include market share, sales growth, profit margin, ROI and ROA. Five-point Likert scales (from 1 = significantly lower to 5 = significantly higher) are employed. Previous empirical findings revealed there are links between environment, firm competitive priorities, and business performance and proved that as a foundation for strategic management research the choice of competitive priorities significantly affects firm business performance [9,13,14,17,26]. It is postulated when confronting the similar environment high performing firms respond differently strategically compared to low performers to achieve a better match of strategy to environment. Therefore, hypothesis 5 is proposed as follows.

H5:

The strategy responses to business environment between high and low performers are significantly different.

3. Conceptual Model and Survey Instrument Development

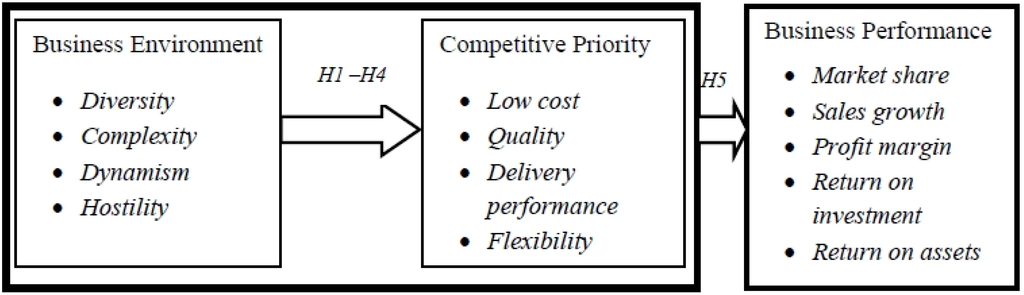

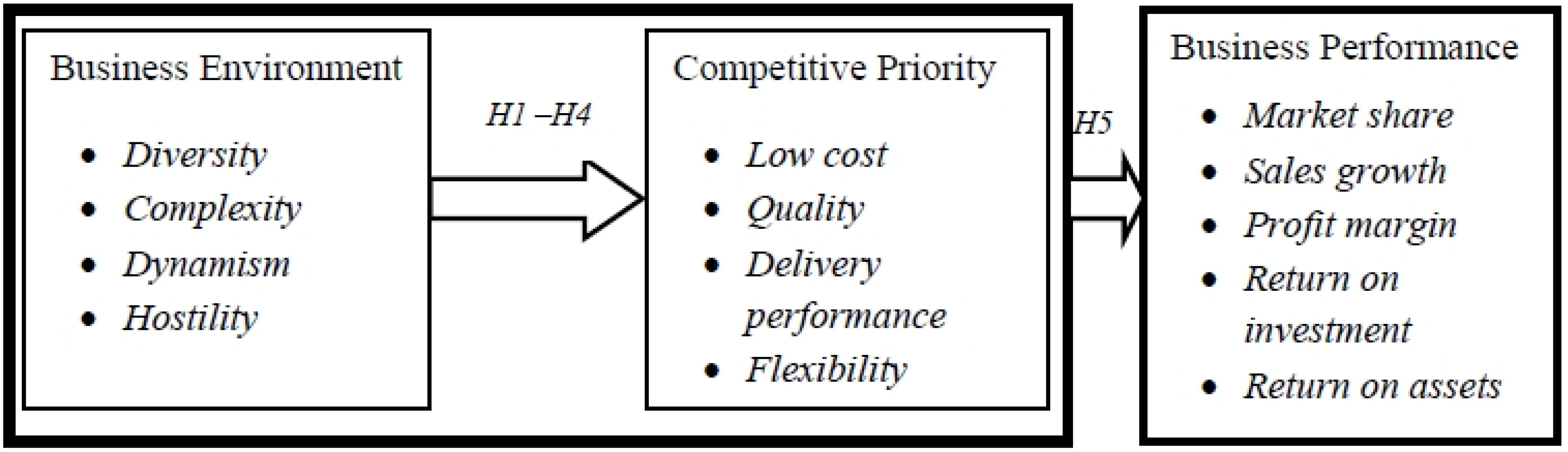

Based on the review of literature, an environment-strategy-performance conceptual model is proposed and illustrated in Figure 1. It represents the proposed relationships (hypotheses) between the latent constructs—business environment, competitive priority, and firm business performance.

Figure 1.

Proposed environment-strategy-performance model.

Figure 1.

Proposed environment-strategy-performance model.

The characteristics of business environment are captured by four first-order latent constructs: diversity, complexity, dynamism and hostility. Competitive priorities are represented by four first-order latent constructs: low cost, quality, delivery performance and flexibility. Each of these first-order latent constructs is measured by multiple measures. Firm business performance is a first-order latent construct measured by the aforementioned five measures. Table 1 lists all 16 possible strategy responses to each dimension of business environment. These relationships were statistically tested and determined in the context of Chinese apparel SMEs.

Table 1.

Tested relationships between environmental dimensions and strategy responses.

| Path | From | To | Path | From | To |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Diversity | Low cost | 9 | Dynamism | Low cost |

| 2 | Diversity | Quality | 10 | Dynamism | Quality |

| 3 | Diversity | Delivery performance | 11 | Dynamism | Delivery performance |

| 4 | Diversity | Flexibility | 12 | Dynamism | Flexibility |

| 5 | Complexity | Low cost | 13 | Hostility | Low cost |

| 6 | Complexity | Quality | 14 | Hostility | Quality |

| 7 | Complexity | Delivery performance | 15 | Hostility | Delivery performance |

| 8 | Complexity | Flexibility | 16 | Hostility | Flexibility |

The measures and corresponding scales for the constructs of business environment and competitive priority are summarized in Appendix 1. They were adapted from previous empirical studies including Chi [12], Ward and Duray [20], Ward et al. [14], and Yu and Ramanathan [26] and further examined by academic and industrial experts to provide the proof of content validity [44].

In order to determine the effect of the match between strategy and business environment on firm business performance, the survey responses were divided into two sub-samples in terms of performance. The 316 responses were sorted in descending order in terms of their mean scores of five performance measures. The first half of the responses were designated as relatively high performers and the second half were designated as relatively low performers. This method has been successfully applied in various prior studies [12,14,17,20,45]. In this study, the statistical analysis was conducted for high and low performer sub-samples, respectively, to determine their strategy responses to the business environment. The significance of the differences was further statistically tested. The test requires pooling both high and low performer data sets and including a dummy variable for performance (i.e., low performer = 0 and high performer = 1) on each possible path (see Table 1). The test results on the coefficients of performance dummy variable indicate which paths are significantly different between high and low performers.

4. Methodology

4.1. Research Subjects and Data Collection

Primary data were gathered by a questionnaire survey of Chinese apparel manufacturers. A random sample of 3000 small- and medium-sized apparel manufacturing firms (with annual sales revenue no more than $10 million and employees no more than 1000 [4]), which located in five major apparel production and export provinces (i.e., Zhejiang, Jiangsu, Shandong, Fujian, and Guangdong), was prepared using major firm databases in the Chinese apparel industry (i.e., firm directories from China’s National Garment Association, Chinese Texnet and Global Texnet). The firms located in these regions have been vanguard of China’s economic reform process and are currently confronting the pressure and challenges of industrial upgrading process [4,8]. The survey targeted senior executives with an overview of the firm’s business operations and strategies to ensure they had knowledge of the issues the survey addressed.

The developed survey instrument was pre-tested through eight interviews with senior executives of apparel SMEs in Zhejiang and Jiangsu provinces. The instrument was thus slightly refined with regard to arrangement, wording accuracy, and relevance. This procedure helped make the final survey instrument more valid and clearer. All 3000 firms in the sample were initially contacted by telephone and email and were solicited to participate in the survey. The web-based questionnaire was hosted on a professional online survey server and was available freely for contacted firms. There were two follow-up email reminders to the firms in the third and sixth weeks after the initial contact. The final eligible survey returns were 316 at 10.5% response rate, which was satisfactory compared to the rates in previous industrial studies [46,47,48], particularly in light of the challenging condition facing the Chinese apparel industry.

Table 2 profiles the participated Chinese apparel SMEs. A majority of SMEs have been in the business longer than 10 years. A wide range of apparel businesses was covered. Most respondents were firm owners or high-ranking executives and had the essential knowledge to provide dependable answers.

Table 2.

Profile of the participating Chinese apparel SMEs in the survey.

| Product Category | % | Gross Sales Revenue (unit: mn US$) | % | Respondent Position | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men/boys coats, trousers, shirts, underwear etc., woven | 49 | ≤2 | 18 | Owner, President, CEO | 75 |

| Men/boys shirts, underwear etc., knit | 22 | >2, ≤4 | 22 | Senior vice president, Vice president | 14 |

| Women/girl trousers, blouse, under/nightwear, etc., woven | 60 | >4, ≤ 6 | 30 | General manager, Directing manager | 6 |

| Women/girls under/nightwear, etc. knit | 15 | >6, ≤8 | 18 | Chairman | 3 |

| Jerseys, pullovers, etc., knit | 44 | >8, ≤10 | 12 | Others | 2 |

| Number of years in business | % | Geographic location | % | Number of employees | % |

| ≤3 | 4 | Zhejiang | 28 | ≤200 | 14 |

| >3, ≤5 | 8 | Jiangsu | 25 | >200, ≤400 | 24 |

| >5, ≤10 | 9 | Shandong | 18 | >400, ≤600 | 23 |

| > 10, ≤15 | 47 | Fujian | 13 | >600, ≤800 | 26 |

| >15 | 32 | Guangdong | 16 | >800, ≤1000 | 13 |

Note: The total number of SMEs is 316. Some firms indicated they produced apparel in multiple categories.

4.2. Statistical Method

Non-response bias was first evaluated using the t-test on demographic variables. As a convention, the responses of early and late groups of returned surveys were compared to provide support of non-response bias [49]. Furthermore, factor analysis using varimax rotation method (SPSS software) was utilized to reduce a larger number of variables to a smaller set of summary variables (i.e., factors) [50].

Two steps to the structural equation modeling (SEM) approach were employed in this study. Step one was to establish the adequacy for each measurement model (i.e., individual latent constructs). This was examined in terms of model-to-data fit and parameter estimates. The unidimensionality, reliability, and construct validity (including both convergent validity and discriminant validity) of each latent construct were assessed. Thereafter, step two determined the full SEM model adequacy and tested the proposed hypotheses between the constructs [51]. The significant paths between paired constructs in the model imply the simultaneous existence of relationships and a corresponding set of strategy responses to perceived business environment. LISREL software was utilized for the SEM analysis.

5. Results and Discussion

As the measures for business performance showed unidimensionality, a single set of composite scores of these measures was used to represent the construct [14]. The 316 responses were sorted in descending order in terms of their mean scores of five performance measures. The first half of the responses were designated as relatively high performers and the second half were designated as relatively low performers. The results of non-response bias test on firm demographic factors (i.e., gross sales revenue, respondent position, number of years in business, number of employees, and product type) showed there were no significant differences between early and late groups of returned surveys. Factor analysis helped reduce the measures which showed high cross loading and/or low factor loading.

5.1. Measurement Model Test Results

The test results of measurement models for both high and low performer sub-samples are summarized in Appendix 2. The results indicated all measurement models met the model-to-data fit requirements for both sub-samples. The standardized loadings comparisons for each latent construct individually modeled and that construct in the context of the structural model showed little or no difference in value, which established the evidences of unidimensionality [52]. For both sub-samples, Cronbach’s coefficient alphas of all latent constructs were above 0.70, indicating reliability was rigorously established [53]. All measures’ loadings were significantly high (loadings > 0.50) and all of the goodness of fit indices exceeded the criterion values. In addition, the average variance extracted (AVE) scores for all constructs in both sub-samples were above the desired threshold of 0.5. These results suggested convergent validity was established [54]. None of confidence intervals of two standard errors around the correlations between each respective pair of constructs captured 1.0. Thus, the criterion of discriminant validity was met for both sub-samples [55].

5.2. Structural Model Test Results

Once unidimensionality, reliability, and construct validity for the measurement models were demonstrated for both high and low performer sub-samples, the structural model fits for both sub-samples were tested. The results including both absolute fit indices (i.e., Normed Chi-square (χ2), the root mean squared approximation of error (RMSEA) and goodness-of-fit index (GFI)) and relative fit indices (The Normed Fit Index (NFI) and the Non-Normed Fit Index (NNFI)) in Table 3 show that the structural model fit was adequate.

Table 3.

Results of structural model goodness-of-fit indices.

| Sub-Sample | Normed Chi-Square | RMSEA | GFI | NFI | NNFI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High performers | 1.61 | 0.04 | 0.94 | 0.96 | 0.95 |

| Low performers | 1.73 | 0.05 | 0.93 | 0.95 | 0.94 |

| Criterion values | ≤2 | ≤0.08 | ≥0.90 | ≥0.90 | ≥0.90 |

The model was then tested separately for high performers and low performers to determine path coefficients, and also to reveal the differences in the strategy responses between high and low performers when facing a similar business environment. Table 4 presents the statistically significant relationships in the structural model for high and low performer sub-samples, respectively, and the test results on the coefficients of performance dummy variable for each path. Significant coefficients of performance dummy variable indicate there are significant differences in strategy response to environment between high and low performers.

Table 4.

Results of SEM analysis for the structural model.

| Path | High Performers | Low Performers | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Path Coefficient | t-Value | Path Coefficient | t-Value | |

| Environmental Diversity | ||||

| Low cost ** | −0.29 | −0.88 | 0.83 | 2.52 * |

| Quality ** | −0.72 | −2.53 * | −0.41 | −1.38 |

| Delivery performance | 0.35 | 0.61 | 0.29 | 0.73 |

| Flexibility | −0.08 | −0.48 | −0.11 | −0.62 |

| Environmental Complexity | ||||

| Low cost ** | −0.54 | −2.46 * | 0.78 | 2.66 * |

| Quality | 0.28 | 1.42 | 0.46 | 1.61 |

| Delivery performance | 0.31 | 1.59 | 0.39 | 1.47 |

| Flexibility ** | 0.53 | 2.58 * | −0.42 | −1.64 |

| Environmental Dynamism | ||||

| Low cost ** | −0.36 | −1.34 | 0.74 | 2.88 * |

| Quality | 0.64 | 2.57 * | 0.68 | 2.71 * |

| Delivery performance ** | 0.49 | 2.43 * | 0.32 | 1.02 |

| Flexibility ** | 0.42 | 2.38 * | 0.37 | 1.59 |

| Environmental Hostility | ||||

| Low cost ** | −0.11 | −0.56 | 1.08 | 3.38 * |

| Quality ** | 1.17 | 4.78 * | 0.36 | 1.21 |

| Delivery performance ** | 0.82 | 3.93 * | 0.33 | 1.05 |

| Flexibility | 0.73 | 2.77 * | 0.87 | 2.65 * |

Notes: * The path coefficient is significant at 0.05 level for high and low performers respectively; ** The coefficient of performance dummy variable is significant at 0.05 level between high and low performers.

5.3. Discussion

As shown in Table 4, for high performing firms, among four environmental dimensions, dynamism and hostility showed more prominent effects on the formation of firm strategies. Dynamic and hostile environment had positive and statistically significant impacts on the firm strategy responses in quality, delivery performance, and flexibility, but negative and non-significant influence on low cost. The results mesh with the previous findings [9,14,17,20], that differentiation through emphasizing quality, delivery performance, and flexibility is a more effective strategy response in a more dynamic and hostile business environment. In contrast, only quality strategy is significantly affected by environmental diversity in a reverse direction. This indicates that, with the increasingly diversified numbers of end-use markets, foreign markets, and/or operations processes, high performers were prone to emphasize quality less. Environmental complexity significantly affects low cost strategy in a reverse direction but flexibility strategy in a positive way. Incremental complexity in knowledge required to meet customer needs, make segmentation within major end-use markets, and manage supply chain resulted in higher cost of doing business and need of greater flexibility. These empirical evidences corroborate the previous findings [3,8] that Chinese apparel firms are facing rising challenges in quality assurance, quick response, and global supply chain management when they experience fast sales growth and market expansion. In recent years, cost advantage which was held by Chinese apparel firms, has been eroded gradually by emerging competitors from lower income countries such as Vietnam, Bangladesh, and Indonesia. Today, low cost is no longer a market-winning strategy for Chinese apparel firms but a qualifying factor to stay in the business [4]. While the process of government-led industrial upgrading continues, forward-looking Chinese apparel SMEs have proactively shifted their strategic focus from solely or mainly cost reduction to a variety of differentiating factors which bring in more added value and are less imitable by competitors.

For low performing firms, environmental diversity and complexity only significantly affected low cost strategy. The more diverse and complex the environment facing a firm is, the more emphasis low performers gives to cost reduction. Environmental dynamism significantly affected both low cost and quality strategies in a positive way; and the paths from environmental hostility to low cost and flexibility were positive and statistically significant. The low performers’ strategy responses to environment were quite contrary to those of high performers. When confronting escalating dynamic and hostile environment, low performers always prioritized low cost as a key strategy although quality and flexibility were also given certain weights. The simultaneous emphasis of both cost leadership and differentiation by low performing Chinese apparel SMEs can be the phenomenon called “stuck in the middle” by Porter [34]. This has been observed by some researchers [3,8]. In recent years, with intensifying competition in the global apparel market and climbing labor cost and tightening worker and environment protection laws in China, the transition of many Chinese apparel SMEs has not been either smooth or joyful [4]. On the one hand, the importance of cost advantage has been deeply rooted in the mindsets of those senior executives through their decadal successes. On the other hand, the rapidly deteriorating profit margin has forced them to explore alternative strategies which can help them survive and grow. However, the lack of sufficient capital and human resources has been the major constraint preventing SMEs from achieving competitive advantages in both cost leadership and differentiation at the same time.

In sum, the test results show that the expected relationships (hypotheses 1, 2, 3, and 4) between environmental characteristics and firm strategy responses did exist for high performing firms but were not supported by low performing firms. Moreover, the test results on the coefficients of performance dummy variable show the strategy responses to business environment between high and low performers are significantly different. High and low performers responded to environmental diversity differently in low cost and quality, to complexity differently in low cost and flexibility, to dynamism differently in low cost, delivery performance, and flexibility, and to hostility differently in low cost, quality and delivery performance. These results support hypothesis 5. Furthermore, the total variance of competitive priorities (R2) for the high performers’ sub-sample was 0.71, which indicates 71 percent of the variance of their strategy formation can be accounted for by the changes in business environment. In contrast, R2 for low performers was only 0.39, which means that the strategies formed by low performers to build competitive capabilities were comparatively less responsive to the environment in which they operate.

6. Conclusions and Implications

This study lends support to the notion that strategy formation is to some extent a response to the perceived business environment. In recent years, Chinese apparel SMEs have been facing increasing environmental turbulence. The industry-wide upgrading and escalating global competition have forced a great number of SMEs to fundamentally redesign their strategies as well as management system in order to thrive or just survive. The transition from original-equipment-manufacturer (OEM) to original-brand-manufacturer (OBM) and/or original-design-manufacturer (ODM) is neither smooth nor uniform in the industry. The differences in strategy responses to environment between high and low performers were striking.

Overall, this study contributes to the management literature in five ways. First, although a conceptual model linking business environment, firm strategy, and business performance is solidly grounded on the extant theoretical literature, a simultaneous empirical investigation of all relationships between paired constructs has been lacking, particularly in the context of emerging economies. This paper addressed the deficiency and applied the proposed environment-strategy-performance model to the Chinese apparel industry that has experienced extraordinary growth in the past several decades. Second, this research developed a reliable and valid survey instrument for measuring all constructs in the proposed model. The business environment confronting Chinese apparel SMEs was investigated in all four dimensions. In comparison, many previous studies only covered one or two of these dimensions such as dynamism or hostility [14,17]. Third, by conducting SEM analysis, the study provided a systemic and complete understanding of all possible strategy responses to individual environmental dimensions and the effects of matching between strategy and environment on firm business performance. The appropriate strategies given specific environmental characteristics were discovered, while the consequence of mismatch was revealed. Fourth, because the proposed model shows sound and stable psychometric properties while the parsimonious statistical criteria and indices are also well met by all constructs, it offers a valid and reliable tool to investigate environment-strategy-performance relationships in other emerging economies. Finally, this research demonstrated the universality of strategy and environment constructs which are generally restricted in application to mature economies by showing their applicability in China. The transition happening in the Chinese apparel industry is an epitome of the entire Chinese manufacturing industry and possibly other emerging economies [8,55]. The identified strategy to environment optimum configurations among Chinese apparel SMEs may be codified and the methodology may be transferred to studies targeting other industrial sectors in China or counterparts in other emerging economies.

This study also generates some findings that impact managerial practices. For industrial practitioners in China and other emerging economies which are facing a similar transition, as they continue to experience intensifying international and domestic competition, rapidly changing market needs, and continued technological advancement, business environment is likely to be even more turbulent in the near future. Cost leadership which was the market-winning strategy for majority of Chinese apparel manufacturers and many manufacturers from other emerging economies has become a more market-qualifying factor in many aspects. In today’s Chinese apparel industry, superior business performance is hardly achieved through unidimensional low cost strategy but is more likely to be the outcome of effective differentiation strategy. Quality, delivery performance, and flexibility are the areas which were underdeveloped or to some extent neglected by Chinese firms but now demand greater attention and investment. The recent noticeable shift of foreign buyers from China to other lower cost developing countries such as Vietnam, Bangladesh, and Cambodia has been signaling the urgency for Chinese firms to adapt more proactively to the changed environment. In sum, firms in any economy need to be constantly aware of the business environment for ongoing and possible shifts in order to make timely and appropriate adjustments in their strategies. Inaction or slower action by a firm in a turbulent environment can lead to an escalating erosion of market share and profit margin and eventually business failure.

7. Limitations and Future Studies

This study overcame some drawbacks experienced in the previous research. However, there are still several limitations that need to be pointed out and also can be considered as possible directions for future research. First of all, the data analyzed in this study is based on respondents’ self-perceptive answers. Although the respondents were senior executives and the questions were articulated, bias, arising from respondent subjectivity and possible misunderstanding, could not be completely eliminated. In future studies, some objective measures based on secondary evidence may be incorporated as complementary information. Second, this study presents an analysis of relationships at a single point of time. Since the business environment is ever changing, follow-up studies can be developed to identify the changes and to examine whether and how these investigated relationships have changed. Third, the impacts of law and regulation changes on the development of Chinese apparel SMEs may be further explored, given the transition nature of the country as well as the industry. Finally, since the relationships of environment-strategy-performance have been relatively less investigated in the context of emerging economies, a cross-country comparison study can be developed in the future.

Appendix 1. Measures and Scales of Business Environment and Competitive Priority Constructs

Table A1.

Latent Constructs and Corresponding Measures.

| Latent Constructs | Measures |

|---|---|

| Environmental diversity | The number of major end-use markets |

| The number of foreign markets | |

| The number of operations processes embraced within the company | |

| Environmental complexity | The complexity of knowledge required to meet customer needs |

| The degree of segmentation within major end-use markets | |

| The complexity of supply chain | |

| Environmental dynamism | Rate at which products and services become outdated |

| Rate of innovation of new operations processes | |

| Rate of change in customer needs in your industry | |

| Rate of emergence of new challenges from competitors | |

| Rate of information diffusion | |

| Environmental hostility | Importance of producing to the customers’ quality requirement |

| Importance of unreliable supplier quality | |

| Importance of rising business costs | |

| Intensity of competition in market | |

| Profit margins | |

| Low cost | Achieve/maintain lowest production cost |

| Increase labor productivity | |

| Increase capacity utilization | |

| Achieve/maintain lowest inventory | |

| Quality | Provide high performance design |

| Offer consistent and reliable quality | |

| Conformance to product design specification | |

| Delivery performance | Provide fast delivery |

| Delivery on time | |

| Reduce production lead time | |

| Flexibility | Make rapid volume changes |

| Make rapid design changes | |

| Adjust capacity quickly | |

| Offer a large number of product features | |

| Offer a broad product variety | |

| Adjust product mix quickly |

Note: Source: Mintzberg [4], Chi [9,12], Ward et al. [14], Ward and Duray [20], Dess and Beard [22], and Yu and Ramanathan [26]. For business environment constructs, scales are 1 = very low, 2 = low, 3 = moderate, 4 = high, and 5 = very high; For competitive priority constructs, scales are 1 = no emphasis, 2 = little emphasis, 3 = moderate emphasis, 4 = strong emphasis, and 5 = extreme emphasis.

Appendix 2. Test Results of Measurement Models.

Table A2.

Goodness-of-Fit Indices for the Measurement Models.

| Constructs | Normed Chi-Square | RMSEA | GFI | NFI | NNFI | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H | L | H | L | H | L | H | L | H | L | |

| Diversity | 1.28 | 1.45 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.96 |

| Complexity | 1.53 | 1.68 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.95 |

| Dynamism | 1.74 | 1.59 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.94 | 0.93 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.96 | 0.98 |

| Hostility | 1.43 | 1.38 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.95 | 0.96 | 0.97 | 0.98 | 0.96 | 0.97 |

| Low cost | 1.66 | 1.68 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.94 | 0.92 | 0.94 | 0.97 | 0.94 | 0.95 |

| Quality | 1.61 | 1.73 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.97 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.97 |

| Delivery performance | 1.17 | 1.26 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.94 | 0.93 | 0.96 | 0.95 | 0.96 | 0.97 |

| Flexibility | 1.41 | 1.47 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.95 | 0.96 | 0.94 | 0.95 | 0.91 | 0.93 |

| Criteria | ≤2 | ≤0.08 | ≥0.90 | ≥0.90 | ≥0.90 | |||||

Notes: H means high performer sub-sample; L means low performer sub-sample.

Table A3.

Reliability and Convergent Validity Assessment.

| Constructs | Cronbach’s Coefficient Alpha (H) | Cronbach’s Coefficient Alpha (L) | AVE (H) | AVE (L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diversity | 0.735 | 0.758 | 0.613 | 0.634 |

| Complexity | 0.811 | 0.769 | 0.682 | 0.655 |

| Dynamism | 0.849 | 0.926 | 0.726 | 0.806 |

| Hostility | 0.882 | 0.842 | 0.767 | 0.723 |

| Low cost | 0.894 | 0.918 | 0.787 | 0.787 |

| Quality | 0.863 | 0.883 | 0.738 | 0.759 |

| Delivery performance | 0.858 | 0.706 | 0.743 | 0.688 |

| Flexibility | 0.764 | 0.823 | 0.681 | 0.702 |

Notes: H means high performer sub-sample; L means low performer sub-sample.

Table A4.

Discriminant Validity Assessment.

| Constructs | Confidence Interval (H) | Confidence Interval (L) |

|---|---|---|

| Diversity—Complexity | (0.34, 0.68) | (0.16, 0.56) |

| Diversity—Dynamism | (0.08, 0.52) | (0.04, 0.40) |

| Diversity—Hostility | (0.14, 0.48) | (0.08, 0.46) |

| Diversity—Low cost | (−0.20, 0.12) | (0.16, 0.58) |

| Diversity—Quality | (−0.26, 0.10) | (−0.24, 0.12) |

| Diversity—Delivery performance | (0.10, 0.42) | (0.06,0.52) |

| Diversity—Flexibility | (0.08, 0.52) | (−0.17, 0.13) |

| Complexity—Dynamism | (0.24, 0.62) | (0.14, 0.50) |

| Complexity—Hostility | (0.12, 0.58) | (0.30, 0.70) |

| Complexity—Low cost | (−0.30, 0.14) | (0.18, 0.50) |

| Complexity—Quality | (0.20, 0.64) | (0.10, 0.40) |

| Complexity—Delivery performance | (0.25, 0.66) | (0.08, 032) |

| Complexity—Flexibility | (0.08, 0.52) | (−0.26, 0.14) |

| Dynamism—Hostility | (−0.10, 0.36) | (−0.26, 0.18) |

| Dynamism—Low cost | (−0.32, 0.16) | (0.20, 0.56) |

| Dynamism—Quality | (0.28, 0.66) | (0.16, 0.48) |

| Dynamism—Delivery performance | (0.21, 0.65) | (0.10, 0.42) |

| Dynamism—Flexibility | (0.12, 0.54) | (0.36, 0.58) |

| Hostility—Low cost | (−0.21 0.13) | (0.24, 0.60) |

| Hostility—Quality | (0.48, 0.72) | (0.19, 0.45) |

| Hostility—Delivery performance | (0.50, 0.78) | (0.15, 0.43) |

| Hostility—Flexibility | (0.18, 0.64) | (0.21, 0.57) |

| Low cost—Quality | (−0.10, 0.28) | (0.14, 0.66) |

| Low cost—Delivery performance | (−0.14, 0.42) | (0.12, 0.42) |

| Low cost—Flexibility | (−0.32, 0.18) | (0.04, 0.38) |

| Quality—Delivery performance | (0.23, 0.69) | (0.23, 0.55) |

| Quality—Flexibility | (0.28, 0.64) | (0.06, 0.38) |

| Delivery performance—Flexibility | (0.16, 0.56) | (0.10, 0.42) |

Notes: H means high performers sub-sample; L means low performers sub-sample.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- China National Textile and Apparel Council (CNTAC). China Textile Industry Development Report 2011/2012; China Textile Press: Beijing, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations (UN) Comtrade Database. UN Comtrade Database SITC Rev. 4. Available online: http://comtrade.un.org/db/dqBasicQuery.aspx (accessed on 10 March 2014).

- Chi, T.; Kilduff, P. An assessment of trends in China’s comparative advantages in textile machinery, man-made fibers, textiles and apparel. J. Text. I 2006, 97, 173–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, T. Building a sustainable supply chain: An analysis of corporate social responsibility practices in the Chinese textile and apparel industry. J. Text. I 2011, 102, 837–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J. Development of Chinese small and medium-sized enterprises. J. Sma. Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2006, 13, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, C.M.; Busenitz, L.W. Growth intentions of entrepreneurs in a transitional economy: The People’s Republic of China. Entrep. Theory Pract.. 2001, 26, 5–20. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Tan, J.; Liu, Y. Moderating effects of entrepreneurial orientation on market orientation-performance linkage: Evidence from Chinese small firms. J. Sma. Bus. Manag. 2008, 46, 113–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Hathcote, J.M. Factors influencing apparel imports from China. Cloth. Text. Res. J. 2008, 26, 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, T. Corporate competitive strategies in a transitional manufacturing industry: An empirical study. Manag. Dec. 2010, 48, 976–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, R.J.; Lemak, D.J.; Reed, R.; Kendall, K.W. A question of fit: The links among environment, strategy formulation, and performance. J. Bus. Manag. 2004, 10, 15–39. [Google Scholar]

- Chi, T. Measurement of business environment characteristics in the US technical textile industry: An empirical study. J. Text. I 2009, 100, 545–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Benitoa, J.; da Rochab, D.; Queiruga, D. The environment as a determining factor of purchasing and supply strategy: An empirical analysis of Brazilian firms. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2010, 124, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, P.T.; Duray, R.; Leong, G.K.; Sum, C. Business environment, operations strategy, and performance: An empirical study of Singapore manufacturers. J. Oper. Manag. 1995, 13, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, M.; Filatotchev, L.; Hoskisson, R.E.; Peng, M.W. Strategy in emerging economies: Challenging the conventional wisdom. J. Manag. Stud. 2005, 42, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, M.L. What is the right supply chain for your product? Harv. Bus. Rev. 1997, 75, 105–116. [Google Scholar]

- Randall, T.; Morgan, R.M.; Morton, A.R. Efficient versus responsive supply chain choice: An empirical examination of influential factors. J. Prod. Innovat. Manag. 2003, 20, 430–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raut, R.D.; Bhasin, H.V.; Kamble, S.S. Analysing the effect of uncertain environmental factors on supplier-buyer strategic partnership (SBSP) by using structural equation model (SEM). Int. J. Proce. Manag. 2012, 5, 202–228. [Google Scholar]

- Mintzberg, H.; Ahlstrand, B.; Lampel, J. Strategy Safari: A Guided Tour through the Wilds of Strategic Management; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, P.T.; Duray, R. Manufacturing strategy in context: Environment, competitive strategy and manufacturing strategy. J. Oper. Manag. 2000, 18, 123–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mintzberg, H. The Structuring of Organizations; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Dess, G.G.; Beard, D.W. Dimensions of organizational task environments. Admin. Sci. Quart. 1984, 29, 52–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharfman, M.P.; Dean, J.W., Jr. Conceptualizing and measuring the organizational environment: A multi-dimensional approach. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 681–700. [Google Scholar]

- Anand, G.; Ward, P.T. Fit, flexibility and performance in manufacturing: Coping with dynamic environments. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2004, 13, 369–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourgeois, L.J. Performance and consensus. Strategic Manag. J. 1980, 1, 227–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Ramanathan, R. Effects of firm characteristics on the link between business environment and operations strategy: Evidence from China’s retail sector. Int. J. Ser. Oper. Manag. 2001, 9, 330–364. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner, W. Manufacturing—Missing link in corporate strategy. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1969, 47, 136–145. [Google Scholar]

- Boyer, K.K.; Lewis, M.W. Competitive priorities: Investigating the need for trade-offs in operations strategy. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2002, 11, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parnell, J.A.; Lester, D.L.; Menefee, M.L. Strategy as a response to organizational uncertainty: An alternative perspective on the strategy-performance relationship. Manag. Dec. 2000, 38, 520–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roh, J.; Hong, P.; Min, H. Implementation of a responsive supply chain strategy in global complexity: The case of manufacturing firms. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2014, 147, 198–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodoroua, P.; Florou, G. Manufacturing strategies and financial performance—The effect of advanced information technology: CAD/CAM systems. Omega 2008, 36, 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cachon, G.P.; Swinney, R. The value of fast fashion: Quick response, enhanced design, and strategic consumer behavior. Manag. Sci. 2001, 57, 778–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyer, K.K.; Pagell, M. Measurement issues in empirical research: Improving measures of operations strategy and advanced manufacturing technology. J. Oper. Manag. 2000, 18, 361–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E. Competitive Strategy. In Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Competitors; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Dess, G.G.; Davis, P. Porter’s (1980) generic strategies as determinants of strategic groups membership and organizational performance. Acad. Manag. J. 1984, 27, 467–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotha, S.; Vadlamani, B.L. Assessing generic strategies: An empirical investigation of two competing typologies in discrete manufacturing industries. Strateg. Manag. J. 1995, 16, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solberg, C.; Durrieu, F. Strategy development in international markets: A two tier approach. Int. J. Mark. Rev. 2008, 25, 520–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoako-Gyampah, K.; Boye, S.S. Operations strategy in an emerging economy: The case of the Ghanaian manufacturing industry. J. Oper. Manag. 2001, 19, 59–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancioni, R.A.; Smith, M.F.; Oliva, T.A. The role of the internet in supply chain management. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2000, 29, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morash, E.A.; Dröge, C.L.M.; Vickery, S.K. Strategic logistics capabilities for competitive advantage and firm success. J. Bus. Logist. 1996, 17, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Stock, G.N.; Greis, N.P.; Kasarda, J.D. Enterprise logistics and supply chain structure: The role of fit. J. Oper. Manag. 2000, 18, 531–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooley, G.J.; Cox, A.J.; Fahy, J.; Beracs, J.; Fonfara, K.; Snoj, B. Marketing capabilities and firm performance: A hierarchical model. J. Market-Focused Manag. 1999, 4, 259–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaworski, B.J.; Kohli, A.K. Market orientation: Antecedents and consequences. J. Mark. 1993, 57, 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swink, M.; Narasimhan, R.; Kim, S.W. Manufacturing practices and strategy integration: Effects on cost efficiency, flexibility, and market-based performance. Dec. Sci. 2005, 36, 427–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambrick, D.C. Taxonomic approaches to studying strategy: Some conceptual and methodological issues. J. Manag. 1984, 10, 27–41. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, K.C.; Lyman, S.B.; Wisner, J.D. Supply chain management: A strategic perspective. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2002, 22, 614–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracey, M.; Tan, C.L. Empirical analysis of supplier selection and involvement, customer satisfaction and firm performance. Sup. Chain Manag. Int. J. 2001, 6, 174–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vonderembse, M.A.; Tracey, M. The impact of supplier selection criteria and supplier involvement on manufacturing performance. J. Sup. Chain Manag. 1999, 35, 33–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, D.M.; Harrington, T.C. Measuring non-response bias in customer service mail surveys. J. Bus. Logist. 1990, 11, 5–25. [Google Scholar]

- Comrey, A.L. A First Course in Factor Analysis; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, B. Structural Equation Modeling with LISREL, PRELIS, & SIMPLIS: Basic Concepts, Applications, & Programming; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ping, R. On assuring valid measures for theoretical models using survey data. J. Bus. Res. 2004, 57, 125–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, T.; Sun, Y. Development of firm export market oriented behavior: Evidence from an emerging economy. Int. Bus. Rev. 2013, 22, 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2015 by the author; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).