Abstract

In modern organisations, ethical leadership has emerged as a key driver of sustainability, shaping both employee behaviour and long-term organisational performance. This study investigates the mechanisms through which ethical leadership fosters organisational sustainability, with a focus on the mediating role of organisational commitment. A quantitative, cross-sectional survey was conducted in mainland Portugal between January 2024 and January 2025 with a sample of 285 employees from medium and large companies (48% male, 52% female). Ethical leadership was measured with the 10-item Ethical Leadership Scale (α = 0.94), organisational commitment with a 7-item validated scale (α = 0.91), and organisational sustainability with a 12-item scale capturing ethical climate and voluntary pro-environmental behaviours (α = 0.93). Data were analysed using structural equation modelling with maximum likelihood estimation and bootstrapping. Results support the hypothesised model, showing that ethical leadership positively predicts organisational commitment (β = 0.62, SE = 0.07, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.48, 0.75]) and organisational sustainability indirectly through commitment (indirect effect β = 0.31, SE = 0.06, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.20, 0.43]). Direct effects of ethical leadership on sustainability were weaker and non-significant once the mediator was included, confirming the centrality of commitment. Model fit indices indicated strong adequacy (CFI = 0.962, TLI = 0.954, RMSEA = 0.048, SRMR = 0.041). Theoretically, the findings reinforce the integration of ethical leadership theory with sustainability research, clarifying the role of commitment as a mediating mechanism. Practically, the study suggests that fostering ethical leadership behaviours—fair decision-making, role modelling, and integrity—can strengthen employee commitment, which in turn drives sustainable organisational practices. This highlights the importance of leadership development programmes centred on ethics as a strategic lever for long-term sustainability.

1. Introduction

Ethics and organisation are two concepts that should remain connected and should not be perceived as separate merely as two theoretical or abstract constructs. Organisational ethics is made up of a set of values, principles and norms for all members of the organisation. In other words, the ethical conduct of companies is a reflection of the conduct of their employees who reinforce interpersonal relationships, success, development and the image of an organisation.

In a theoretical framework, ethics studies the codes of values that influence behaviour and decision-making.

Codes of ethics and conduct constitute not merely symbolic statements of organisational values but practical management instruments aimed at reshaping social power relations and embedding moral responsibility within professional practice (Caldeira et al., 2024). Their main contribution lies in sustaining ethical awareness across organisational contexts and providing a normative framework that defines desirable standards of behaviour, while simultaneously encouraging critical reflection when professionals encounter unprecedented or complex situations (Reber, 2013). In contemporary contexts, it has become increasingly difficult to identify domains of activity that are not permeated by the need for explicit ethical principles, which operate as guiding references to evaluate the impact of practices on individuals, communities, and organisations as a whole (Sandu & Caras, 2013).

In practice, codes of ethics are treated in the same way as codes of deontology, without being influenced by the minimum standards required and recommended for good practice. These codes often combine minimum regulations with rules aimed at excellence (Sandu & Caras, 2013).

In an organisational context, these codes guide companies and their decisions so that they affect society and employees in a positive way, since companies are more valued if they conduct themselves ethically.

Organisational ethics are made up of principles, accepted behavioural norms and values recognised across the board in an organisation. Over time, ethics have proved indispensable within organisations for assessing the credibility of a company, its employees and the influence that leaders have on their employees.

For this reason, leadership is an important topic at the organisational level as it is decisive for business success. The leader must behave ethically towards his employees so that they follow his example, and an ethical leader can determine a company’s credibility by promoting ethical behaviour in his employees.

However, not all leaders stand out for their ethical behaviour (unethical behaviour). Leaders often have a tendency to manipulate and emphasise their position of superiority over their own interests. This results in a negative image for the company and negatively influences its employees.

When a leader cares about his employees and their well-being, he demonstrates his ethical character. But if the leader has attitudes in which he sees his employees as a threat and differentiates them in relation to his position, he is dealing with unethical attitudes.

The aim of this article is to understand how ethics in organisations and their leaders can influence their competitiveness and good image with customers, suppliers and employees, as well as contribute to sustainability.

When organisations adopt environmental ethics as part of their strategy, they reap tangible and intangible benefits. It can therefore be argued that ethical leadership and the promotion of an inclusive environment are interdependent and mutually reinforcing dimensions of organisational culture. Such a culture does not merely tolerate diversity but actively recognises and values it, fostering a workplace in which individuals from heterogeneous backgrounds feel respected, supported, and integrated as legitimate members of the organisational community. This is the place where workers develop their full potential, creativity and work performance through the integration of different visions and skills. Psychological safety, i.e., the team’s collective perception of safety related to interpersonal risks, is a catalyst for open communication, innovation and adaptability (Fyhn et al., 2023). It provides workers with a place to express their opinions, report problems and embody a positive attitude towards their work, which is fundamental to organisational learning and development (Fyhn et al., 2023). In turn, sustainability has become the main concern of business organisations, as it provides opportunities for long-term growth and development, financial viability and competitive advantages (Mouri Dey et al., 2022).

The incorporation of responsible environmental practices is a strategic vector capable of generating multiple organisational benefits, as summarised in Table 1. Reputation and trust emerge as key outcomes, given that environmentally responsible companies tend to gain greater respect and credibility among consumers and investors, reinforcing their legitimacy in the market (Porter & Kramer, 2019).

Table 1.

Company benefits.

In terms of human resources, sustainability plays a decisive role in attracting and retaining talent. Green recruitment practices and the promotion of sustainable work environments significantly increase employee satisfaction, commitment and retention, contributing to improved organisational performance (Glavas & Mish, 2020; Khan & Du, 2021).

In terms of economic efficiency, evidence indicates that the implementation of green practices, combined with the promotion of sustainability, is positively associated with stronger financial performance. The integration of environmental and economic objectives proves not only feasible but also a catalyst for innovation and sustainable growth (Nandy & Lodh, 2022; Youn & Kim, 2023).

2. Definition of Ethics, Organisation, and Organisational Behaviour

Ethics and organisational behaviour are inseparable dimensions that influence each other and together shape the macro dynamics of organisations. Although often studied in isolation, these concepts are intrinsically linked, and an integrated understanding of them is essential to explain their impact on the performance, culture and reputation of institutions.

Etymologically, the word “ethics” derives from the Greek term “ethos”, which means “moral character” and is associated with a set of values that guide human behaviour in society. In the business context, ethics translates into principles such as safety, reliability, respect and integrity, which directly influence organisational image and credibility. The consistent adoption of ethical practices by individuals in corporate roles favours the consolidation of ethical business cultures, which, in turn, enhances the sustainable development of the organisation (Roy et al., 2024; Carlos et al., 2025).

The concept of organisation implies understanding that organisations do not act on their own; it is the individuals who are part of them who determine their actions. Thus, an organisation can be defined as a structured social arrangement with the objective of achieving, in a controlled manner, results orientated towards a collective purpose. This need for coordination and control distinguishes organisations from other social groups. Furthermore, organisations are not static entities: they reflect the interactions and transformations promoted by the people who work in them. They can be constructive environments that encourage self-realisation and individual expression or, conversely, oppressive structures that limit autonomy and creativity. Individual and collective consequences result, to a large extent, from the way organisations are structured and managed (Robbins, 2002; Chiavenato, 2005).

Organisational behaviour refers to the systematic study of the actions and attitudes of individuals and groups in the work context, considering variables such as personality, values, motivations and learning patterns. Robbins (2002) proposes three levels of analysis—individual, group and structural—emphasising that organisational effectiveness results from the alignment between these domains. Chiavenato (2005) adds that this behaviour is influenced by external factors such as culture, beliefs and values and is therefore shaped by broader social contexts.

Recent research reinforces the importance of ethics as a structuring element of organisational behaviour. Roy et al. (2024), in a comprehensive review published in Business Ethics Quarterly, demonstrate that a robust ethical culture not only increases internal and external trust but also stimulates innovation, reduces leader burnout and promotes a healthy organisational climate. Carlos et al. (2025) add that ethical leadership positively influences job satisfaction and stimulates innovative behaviour, mediating the professional thriving of employees. Similarly, longitudinal studies point to the congruence between management practices and ethical values as an essential condition for transforming organisational culture into an engine of innovation (Riivari & Lämsä, 2014, updated in 2024).

In practical terms, an organisation with a weak ethical culture resembles a building with compromised foundations: any external pressure—an economic crisis, a legislative change or a reputational challenge—can jeopardise its stability. In contrast, a strong ethical culture acts as a reinforced structure, capable of sustaining performance, innovation and well-being in the long term.

However, Chiavenato (2005) considers that the behaviour and interaction of individuals in an organisation can have external influences and vary according to culture, beliefs and values.

3. Organisational Culture

Organisational culture refers to the shared values and administrative practices embraced by members of an organisation. If the practices are developed by people in leadership, they can contribute to or eliminate bad behaviour, but if the opposite happens, the organisation and its employees tend to follow the same actions that end up being embedded in the group. Perez and Cobra (2016) argues that: Organisational culture raises the climate of trust and respect among company members, reduces costs and increases productivity, all of this combined with the growing level of general satisfaction arising from the ethical climate prevailing in the workplace (Perez & Cobra, 2016).

We can also define organisational culture as ‘the deeply established ideologies, beliefs and values that emerge in all firms (…) and are prescriptions for how people should work in those organisations’ (Karthikeyan, 2019). In addition to this, the organisational culture must incorporate and/or align with the mission, values and objectives.

In addition to image, the culture an organisation establishes is directly related to results, whether monetary or a good image. In this way, an organisation’s culture has to be continuous and active so as not to lose its principles. When changes within a company are positive, they can improve the organisation and put it ahead of its competitors.

In this context, the manager has an essential role to play when it comes to culture, as it is through their management that the organisation will create its culture and it is necessary for the manager to have a long-term vision so that the attitudes taken are the right ones. The organisation’s image will be a reflection of a manager’s attitudes.

A manager’s actions are directly linked to the organisational culture and they must know how to motivate their employees and guarantee quality service for customers.

3.1. The Climate of Organisational Ethics

Organisational ethics are generally identified in the psychological, social and human spheres that characterise how people relate to each other within the organisation. We can then talk about an ethical organisational climate, which was originally conceptualised by Victor and Cullen. These authors see this as a multifaceted concept that is made up of perceptions shared by members of an organisation and what behaviours are ethically acceptable and how morally qualifying issues should be approached (Cullen et al., 2003).

In another definition, ethical climate can also be understood as a type of work climate that reflects organisational policies, procedures and practices that have moral characteristics and consequences (Mulki et al., 2009).

The ethical climate of an organisation constitutes a critical dimension of its overall organisational culture. Organisational culture, broadly defined, sets the normative framework that guides members’ perceptions of what is considered right or wrong. This normative guidance shapes attitudes, behaviours, and decision-making processes. Accordingly, all matters pertaining to moral judgement contribute to the organisation’s ethical climate, which both influences acceptable conduct and also determines how ethical dilemmas are recognised, interpreted, and addressed collectively.

Ethical climates favour and complement many functions in organisations and help employees to identify important ethical issues. It also helps employees to think more effectively about how to deal with these ethical issues, which enables them to diagnose and evaluate situations.

3.2. Behaviour in Organisations

Often, disagreements in organisations stem from failures that occur due to a lack of commitment, negligence and a failure to comply with or adapt to established standards, especially on the part of leaders. Contradictions to what is expected of an individual can compromise organisational success, since inappropriate conduct has a major impact on the economy and society.

A good performance from the leader and the employees can mean a successful organisational performance and for this to happen there has to be a proper attitude, both in complying with the rules of an organisation, and also proper personal conduct.

Therefore, a leader, as an individual person in society, is expected to be aware of their own actions, as they can have consequences for themselves and others. In addition, a leader must also be able to have moral codes to guide business decisions with the awareness that it can affect both workers and society in general (Neves et al., 2016).

However, leaders’ behaviour can be influenced by psychological, physiological and sociological factors that will underpin leadership.

3.3. Causes and Unethical Behaviour in the Organisational Environment

In the business context, unethical behaviour can result from a diverse set of factors, which are divided between internal influences—related to the psychological and social dynamics within the organisation—and external influences, which derive from the political, economic and cultural environment in which the company operates, as we can see in Table 2.

Table 2.

Unethical behaviour can be caused by external or internal factors. Source: (Machado, 2021).

Internal factors such as uncertainty, insecurity, pressure and competitiveness reflect the reality of demanding work environments, where instability or constant performance evaluation can induce defensive or opportunistic behaviour. The literature shows that continuous exposure to internal pressures is associated with an increased propensity for unethical decisions, especially when these are perceived as necessary to achieve unrealistic goals (Roy et al., 2024).

External factors—political ideologies, individualism, immorality, and economic ideologies—act as sociocultural frameworks that influence organisational practices. For example, unstable political contexts or economic systems that reward short-term profit tend to reduce the perception of reputational risk, encouraging actions that compromise ethical principles (Weaver et al., 2020).

In addition to these dimensions, another frequently observed cause of unethical behaviour is the increased burden of responsibilities without proportional compensation. This discrepancy can foster frustration and lead some individuals to resort to illicit practices as a form of compensation. Prolonged conditions of this type generate emotional dissonance and hinder the construction of a coherent professional identity, opening space for the emergence of distorted moral frameworks, especially when the feeling of injustice becomes persistent (Carlos et al., 2025).

The systematic reproduction of these behaviours not only compromises the internal integrity of the organisation, but also significantly affects its public image. When such acts become known, customers, suppliers and partners tend to make negative value judgements about the company, impacting trust, commercial relations and, ultimately, its sustainability in the market (Machado, 2021; Roy et al., 2024).

3.4. Professional Ethics

Ethics should be one of the characteristics that members of an organisation should have, from the leader to the employees. Some authors, such as Souza and Caldeira, argue that a lack of ethics can have an influence on productivity and the working environment. When we have an unethical environment, work can be unsatisfactory and result in lower results.

In this way, an employee’s individual awareness of doing the right thing is very important in an organisation, as they must value good relations between everyone. In addition, the company must know what it can expect from its employees in order to achieve its objectives in the marketplace, whether through training, company codes of ethics or lectures. Therefore, a good professional must have certain qualities such as honesty, transparency and secrecy. These qualities are fundamental to the success of an organisation.

An employee’s behaviour is directly linked to the company. In the labour market, a company with an unfavourable image or involved in scandals is detrimental both to the company and also to the employee, who can have their image tarnished and not be properly known for inappropriate attitudes.

Performance at work is, unsurprisingly, one of the most analysed and relevant variables in the field of organisational behaviour. It is considered one of the individual behaviours that add value to organisations. In addition, work performance can be seen as an achievement-related behaviour, which includes an evaluative component. This component is identified when employees manage to meet the performance expectations set by organisations.

Over the last ten years, the concept of work performance has evolved from a more traditional focus on specific job tasks to a broader perspective that considers the various functions in a dynamic organisational environment. A study by López-Cabarcos et al. (2022) analysed how the combination of environmental factors at work and leadership styles influences the presence or absence of work performance in employees in the industrial sector. The results highlighted crucial variables such as transformational leadership and social support as determining factors for worker performance.

3.5. Leadership

The first study on leadership assumes that the morale of leaders (Howe et al., 2014) and other factors such as the political system, language or religion alter the characteristics of leadership. However, a general definition points to an individual’s ability to influence, motivate or enable others to contribute to the success of their organisations.

Therefore, in the leadership process, a leader’s moral reputation is very important for the general interest (Machado, 2021). The ethics of leadership promote appropriate moral behaviour and make employees feel the need and importance of following the same moral behaviour. In this way, we realise that the leader must be the guiding example for the workers and ethical leadership will be positive for the organisation/company. Employees will be satisfied with their jobs, will be dedicated to their work and will be more willing to raise problems with their bosses.

Thus, an individual is expected to exercise leadership in an appropriate and positive way in order to influence others to improve their environment. In other words, leadership is a set of interactions between the leader and their workers (Chen et al., 2024).

Ethical leadership can be conceptualised as a set of principles and behavioural standards enacted by leaders through their personal conduct, interpersonal relationships, and communication with followers (Shiundu, 2024). Empirical research on leadership ethics has consistently demonstrated its positive influence on organisational outcomes. Ethical leaders foster cultures grounded in fairness, trust, and respect, which enhance employees’ job satisfaction and strengthen organisational commitment, thereby reinforcing attachment to the workplace (Mishra & Tikoria, 2021). Furthermore, ethical leadership is associated with the promotion of ethical behaviour across organisational levels. Leaders who embody ethical values and institutionalise ethical policies and codes of conduct play a pivotal role in shaping normative expectations, discouraging misconduct, and encouraging actions aligned with both organisational principles and broader social norms (Al Halbusi et al., 2021).

The concept of ethical leadership proposed by Brown and colleagues (2005) links two characteristics: the perceived effectiveness of the leader and the prediction of work-related outcomes, as it incorporates both behavioural characteristics of the leader and interaction with the subordinate (Howe et al., 2014). The general idea is that leaders influence ethical conduct by explicitly defining ethical standards and holding their subordinates accountable to those standards through the use of rewards and discipline (Brown & Treviño, 2006).

3.6. Sustainability

The concept of sustainability has become increasingly prominent in both business practice and empirical research, with a significant surge in scholarly attention over recent decades. Despite this growing interest, the intersection of sustainability with human resource management—particularly in relation to ethics and leadership—remains underexplored. As noted by Reiche (2017), sustainability has become a ubiquitous concept, often invoked across various domains. From an organisational standpoint, leaders are now expected to assume broader responsibilities, both in addressing stakeholder interests and also in contributing to the well-being of the wider community. This requires aligning organisational strategies and practices with ethical and sustainable principles. As highlighted by Joseph (2013), organisational sustainability extends beyond economic performance to encompass environmental stewardship, social responsibility, and ethical integrity.

3.7. Environment

An inclusive organisational environment can be defined as a space that actively encourages the participation of all individuals, irrespective of their origin, identity, or viewpoints. As one of the fundamental pillars supporting diversity and equity, inclusion empowers individuals from heterogeneous backgrounds and ensures that their unique perspectives and contributions are acknowledged and valued. The organisational climate of diversity and inclusion reflects employees’ perceptions regarding the extent to which their workplace is genuinely open and receptive to difference, thereby cultivating conditions in which all members can thrive and achieve their full potential (Mor Barak et al., 2022).

The inclusion climate framework is strongly aligned with the principles of fairness, equality and equal opportunities for participation and growth. As pointed out by (Mor Barak et al., 2022), access to information and resources, as well as participation in inclusive decision-making processes, are the most impactful elements in promoting employee inclusion. These factors support the creation of a work environment in which individuals are recognised and treated as valuable.

A positive organisational climate that promotes inclusion is increasingly recognised as a critical factor in enhancing both diversity and organisational performance. Empirical evidence demonstrates that employees who perceive high levels of inclusion report greater job satisfaction, stronger organisational commitment, and higher intrinsic motivation (Platania et al., 2022). Moreover, inclusive environments are associated with lower turnover intentions and enhanced innovative capacity, as the diversity of perspectives is not only acknowledged but systematically integrated into organisational processes. Research further indicates that an inclusive climate contributes to improved productivity outcomes, particularly by strengthening problem-solving effectiveness and the quality of team decision-making (Jaiswal & Dyaram, 2020).

4. Aim of the Study and Research Questions

This article examines the role of ethical leadership in fostering organisational sustainability. Its primary objective is to explore and synthesise the existing literature—drawing on both academic articles and seminal works—on leadership and ethics, in order to conceptualise how ethical leadership can serve as a strategic driver for sustainable success. Specifically, the study seeks to identify the mechanisms through which ethical principles, when embedded in leadership practices, contribute to guiding organisations towards long-term sustainability.

Although sustainability has become a global imperative aligned with the Sustainable Development Goals, there remains limited research that systematically addresses the importance of ethical leadership in shaping sustainable organisational outcomes. Recent corporate scandals have highlighted the risks of unethical and irresponsible behaviour by leaders, showing how poor organisational culture and climate can jeopardise survival in highly competitive environments. In this context, ethical leadership plays a crucial role in creating an inclusive organisational culture, strengthening commitment and fostering innovation, all of which are essential for long-term legitimacy and competitiveness (Roy et al., 2024; Carlos et al., 2025).

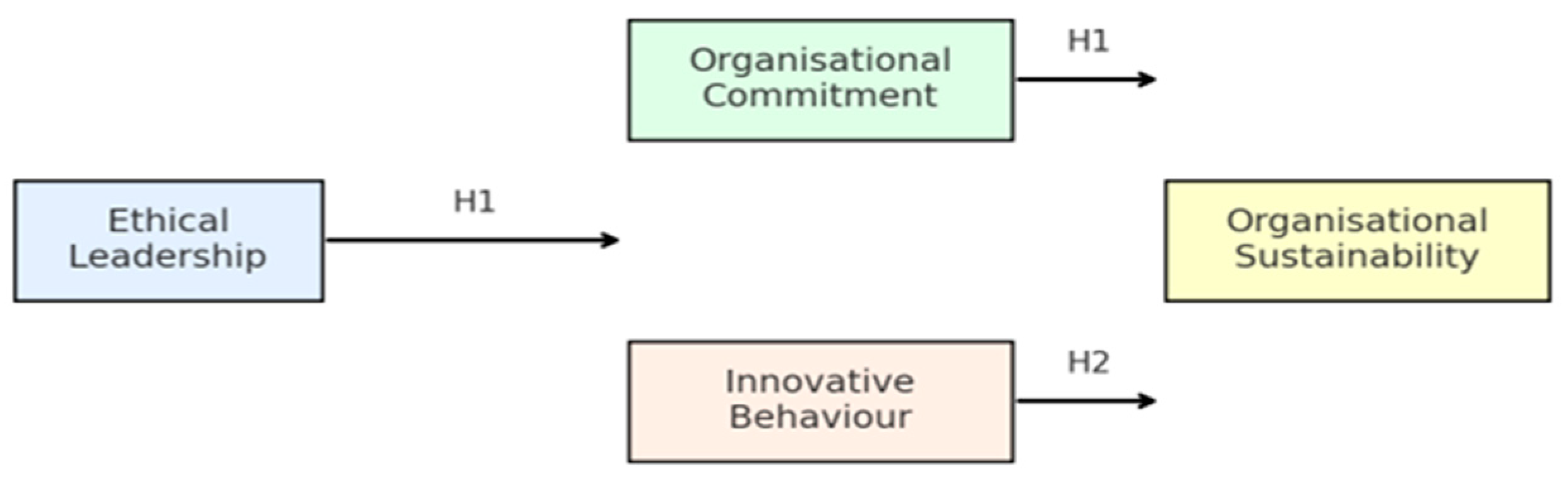

To investigate these dynamics, this study formulates two hypotheses consistent with the conceptual model presented in Figure 1. The first hypothesis posits a mediating mechanism linking ethical leadership to sustainability through organisational commitment, emphasising that leaders with a strong ethical orientation generate trust, psychological safety and employee engagement, which in turn support sustainable practices and outcomes. The second hypothesis considers the role of innovative behaviour as a complementary pathway, suggesting that ethical leaders encourage creativity and initiative among employees, thereby enhancing the organisation’s adaptive capacity and contribution to sustainable development.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework Source: own elaboration.

H1.

Ethical leadership positively influences organisational sustainability through the mediating effect of organisational commitment.

H2.

Ethical leadership positively influences organisational sustainability through the mediating effect of innovative behaviour.

The formulation of only two hypotheses reflects a deliberate methodological choice to privilege analytical clarity over dispersion. Rather than exhaustively testing all possible links between ethics, leadership and sustainability, this study focuses on the most critical pathways identified in the literature and validated by empirical evidence. This approach ensures theoretical relevance, operational clarity, and methodological coherence, while producing results that are both conceptually robust and practically meaningful.

Finally, the article builds on transformational leadership theory to argue that ethical leaders play a central role in creating inclusive and productive work environments. Through practices such as individualised consideration and inspiring motivation, ethical leadership fosters commitment and innovative behaviour, which collectively enhance organisational performance and sustainability.

Conceptual Model (Figure 1)

Figure 1 presents the conceptual model guiding this study. At its core, the model posits that ethical leadership acts as a strategic antecedent of organisational sustainability. The model incorporates two mediating mechanisms—organisational commitment and innovative behaviour—through which ethical leadership exerts its influence.

The first pathway (H1) suggests that ethical leaders foster trust, fairness and a sense of moral responsibility, which enhance employees’ organisational commitment. In turn, a committed workforce supports the adoption of sustainable practices and reinforces the organisation’s long-term legitimacy and performance.

The second pathway (H2) proposes that ethical leadership encourages creativity, openness and psychological safety, which stimulate innovative behaviour among employees. This innovation-orientated climate enables organisations to adapt more effectively to environmental and social challenges, thereby strengthening sustainability outcomes.

By integrating these two mediating mechanisms, the model highlights that ethical leadership does not affect sustainability directly, but rather indirectly, through its ability to mobilise employee attitudes and behaviours that sustain organisational development. This conceptualisation is consistent with transformational leadership theory, which emphasises individualised consideration, inspirational motivation and the alignment of values between leaders and followers.

5. Methods

This study adopted a quantitative, cross-sectional, and descriptive design, conducted in mainland Portugal between January 2024 and January 2025. The target population consisted of employees from medium-sized and large companies, identified through national business databases and professional networks. Inclusion criteria required participants to have at least one year of tenure in their organisation, while interns and temporary workers were excluded to ensure sufficient knowledge of organisational culture. Recruitment was carried out online via invitations distributed through corporate email, and data were collected using an electronic questionnaire. The final sample comprised 285 participants, yielding a 32% response rate. Of these, 137 were male (48%) and 148 female (52%), with ages ranging from 22 to 61 years. The study received approval from an institutional ethics committee, and informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to data collection.

In the conceptual model, ethical leadership was operationalised as the independent variable, organisational commitment served as the mediating variable, and organisational sustainability was defined as the dependent variable. This clarification resolves earlier inconsistencies in which organisational commitment appeared simultaneously as a dependent variable.

The variables were measured using widely validated instruments. Ethical leadership was assessed with the Ethical Leadership Scale (ELS; Brown et al., 2005), consisting of 10 items adapted and translated into Portuguese through a translation–back-translation procedure. An example item is: “My supervisor makes fair and balanced decisions.” In this study, the scale demonstrated high internal consistency (α = 0.94; composite reliability = 0.95; AVE = 0.67). Organisational commitment was measured using seven items from Meyer and Allen’s (1997) scale, previously validated in the Portuguese context, including statements such as “I feel emotionally attached to my organisation.” Reliability indices were also strong (α = 0.91; composite reliability = 0.92; AVE = 0.63). Organisational sustainability was operationalised through 12 items capturing ethical climate and voluntary pro-environmental behaviours, following Yusof et al. (2022). An example item is: “My organisation promotes sustainability practices that go beyond legal requirements.” Results indicated high internal consistency (α = 0.93; composite reliability = 0.94; AVE = 0.65). Discriminant validity was verified by comparing the square root of the AVE with inter-construct correlations, confirming that each construct shared more variance with its own items than with other constructs.

Although the literature often highlights ESG metrics as objective indicators of sustainability, in this study sustainability was operationalised exclusively via self-report scales completed by participants. Archival indicators of economic or environmental performance were not employed, and prior references to ESG metrics have been removed to avoid ambiguity.

Prior to model testing, statistical assumptions were examined. Normality was assessed through the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and inspection of skewness and kurtosis, which indicated acceptable levels for structural equation modelling (SEM). Data analysis was conducted using AMOS v.29 with maximum likelihood estimation and bootstrapping of 5000 samples to estimate indirect effects. Model fit was evaluated through multiple indices: CFI = 0.962, TLI = 0.954, RMSEA = 0.048, and SRMR = 0.041, all within recommended thresholds (Hu & Bentler, 1999). These results confirm the adequacy of the proposed model and the mediating role of organisational commitment in the relationship between ethical leadership and organisational sustainability.

6. Data Analysis

This research employed validated measurement instruments widely recognised in organisational studies to assess key variables, including ethical leadership, inclusive environment, psychological safety, conflict management strategies, and work performance. The use of these tools, whose reliability and validity are well established in the literature, ensured methodological rigour and strengthened the robustness of the empirical findings.

For the purposes of this study, we employed and adapted the Ethical Leadership Scale (ELS), a validated instrument specifically designed to assess ethical leadership and its core dimensions. The ELS consists of 10 items and evaluates perceptions of ethics, fairness, and equality among stakeholders, utilising a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The scale demonstrated high internal consistency in this study, with a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient exceeding 0.90, indicating excellent reliability.

Work performance was assessed using the Work Performance Scale, which comprises two domains: task performance and the level of civility in behaviour. Each domain consists of seven items rated on a five-point Likert scale. Previous studies have demonstrated that the instrument presents strong psychometric properties, with high convergent and discriminant validity, and reliability coefficients (Cronbach’s alpha) consistently exceeding 0.80.

We also used ESG (Environmental, Social, Governance) metrics, which are used by investors to assess a company’s performance on environmental, social and governance issues. These metrics offer a comprehensive view of sustainability and corporate responsibility, analysing three main dimensions: environmental, social and governance. One of the main advantages of ESG metrics is their widespread adoption in the financial market, making them an important reference for investors looking for companies committed to sustainable and responsible practices.

Construct validity was assessed using the Average Variance Extracted (AVE). The results indicated that the AVE for the moderating variable inclusive environment exceeded the recommended threshold value of 0.50, thereby providing evidence of satisfactory convergent validity. In addition, the constructs were tested for reliability, and the findings confirmed that the measurement model met the established psychometric standards.

To assess the potential presence of common method bias, Harman’s single-factor test was conducted. The results revealed that the first factor accounted for less than 50% of the total variance, suggesting that common method bias is unlikely to be a serious concern, as no single factor emerged as dominant in the data structure. Additionally, Variance Inflation Factors (VIFs) were calculated for all measurement items. All VIF values fell below the recommended threshold of 3.3, thereby indicating the absence of significant multicollinearity issues and further supporting the robustness of the measurement model.

In this study, the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was employed to examine whether the data followed a normal distribution. The results of this test are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Source: prepared by the researchers based on the statistical results.

The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test indicated that the p-values for all variables exceeded the conventional significance level of 0.05, as shown in Table 2, suggesting that the data do not significantly deviate from a normal distribution. Additionally, according to the principles of the central limit theorem, for sample sizes greater than 30, the distribution of the sample mean approximates normality regardless of the shape of the population distribution, provided that the mean (µ) and variance (σ2) are defined.

We used the two tests as they are complementary, as they address different aspects of the data. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test focuses on the distribution of the data (normality), while Harman’s Single Factor Test focuses on common method bias. Therefore, the use of both in your article can be justified, especially if we are dealing with a scientific article where a more rigorous and detailed statistical analysis is sought.

Empirical evidence has also shown that ethical leadership has a significant influence on employees’ voluntary environmental behaviour. This type of behaviour, characterised by proactive and non-mandatory actions in favour of the environment, contributes directly to improving the sustainable performance of business organisations.

The study employed path analysis to test the proposed hypotheses, and the key statistical results are summarised in Table 4 below:

Table 4.

Structural model path analysis. Source: prepared by the researchers on the basis of the statistical results.

The Table 4 presents the structural paths among the key variables of the study. The results of the hypothesis testing are as follows: the standardised beta coefficient for the direct path between ethical leadership and organisational commitment was 0.566 (p < 0.001), indicating a strong and statistically significant positive effect. This finding provides empirical support for Hypothesis H1, confirming that ethical leadership has a substantial impact on enhancing organisational commitment.

The standardised beta coefficient for the indirect path between ethical leadership and innovative behaviour, mediated by organisational commitment, was 0.374 (p < 0.001). This result indicates a statistically significant and positive indirect effect, suggesting that organisational commitment plays a meaningful role in enhancing the relationship between ethical leadership and sustainability-related outcomes. Therefore, organisational commitment functions as a partial mediator in this relationship, providing empirical support for Hypothesis H2.

7. Discussion and Conclusions

The findings of this study reinforce the well-established association between ethical leadership and key organisational outcomes, notably sustainability and work performance. As demonstrated in the literature, ethics constitutes a foundational dimension of organisational life, intersecting with economic, moral, and social responsibilities (Brown & Treviño, 2006; Freeman & Stewart, 2006). Organisations are inherently composed of individuals and embedded within broader societal systems; thus, the adoption of ethical principles is not merely a normative expectation but also a functional requirement for long-term organisational stability and legitimacy.

Theoretical Contributions

This research makes meaningful contributions to theoretical development in the fields of organisational ethics and ethical leadership, responding to the call by Homer and Lim (2024) to bridge contextual understanding (“doing as the Romans do”) with conceptual grounding (“understanding why the Romans do it”). By analysing empirical data collected in Portugal and integrating it with constructs widely discussed in the international literature, this study not only confirms previously established associations—such as the positive relationship between ethical leadership, performance, and sustainability—but also extends the understanding of how these phenomena manifest within specific socio-economic contexts.

Homer and Lim’s (2024) framework underscores that management theory must simultaneously capture local specificities and contribute to a broader, generalisable body of knowledge. In this respect, the present study demonstrates that ethical leadership practices observed in the Portuguese context can inform global models while recognising that cultural and institutional nuances modulate the pathways through which ethics shapes organisational sustainability.

Accordingly, the study positions itself as a step toward the advancement of a more context-sensitive theory that links micro-level processes (individual behaviours and perceptions) to macro-level outcomes (sustainability and organisational reputation), thus strengthening the bridge between practice and theory and addressing one of the core challenges identified in contemporary scholarship.

The results further suggest that organisations recognised for ethical practices benefit from enhanced internal cohesion and external trust, aligning with prior findings that connect ethical climates with increased employee engagement and stakeholder confidence (Bedi et al., 2016). Ethical leadership, in particular, fosters an organisational environment perceived as fair and inclusive, which can, in turn, promote cooperation, reduce conflict, and facilitate the implementation of sustainability-orientated strategies.

Nevertheless, the data highlight persistent challenges in the consistent application of ethical leadership. Previous research has documented the adverse effects of narcissistic leadership traits, including reduced employee well-being and diminished organisational citizenship behaviours (Rosenthal & Pittinsky, 2006). Leadership dynamics that reinforce hierarchical distance may contribute to perceptions of injustice and demotivation, ultimately undermining organisational cohesion and long-term performance (Van Gils et al., 2015). These findings reinforce the need to strengthen ethical standards both at the policy level and in day-to-day leadership practices.

This study enriches the literature by providing empirical evidence of the positive correlation between ethical leadership and organisational sustainability, particularly in Portuguese medium and large enterprises. The results corroborate earlier studies demonstrating that ethical leadership is positively associated with employees’ voluntary pro-environmental behaviour (Robertson & Barling, 2013), which, in turn, advances broader sustainability outcomes.

Quantitative evidence reinforces these claims. For instance, ethical leadership has been linked to a 23% reduction in employee turnover (SHRM, 2020), a 21% increase in the adoption of sustainability practices (Harvard Business Review, 2019), and a 16% improvement in organisational productivity (McKinsey & Company, 2020). Moreover, 67% of employees report engaging in voluntary environmental behaviours under the influence of ethical leadership (Journal of Business Ethics, 2020). Such indicators provide a robust empirical foundation for positioning ethical leadership as a catalyst for sustainable organisational performance.

Despite these contributions, the study’s limitations must be acknowledged. The reliance on voluntary, anonymous participation may have introduced self-selection bias, potentially constraining the generalisability of findings. Future research could benefit from employing stratified or purposive sampling strategies to ensure greater representativeness. Longitudinal designs are also recommended to capture the enduring effects of ethical leadership on organisational culture and performance. Additionally, comparative cross-cultural analyses could yield valuable insights into how ethical leadership practices vary across different socio-institutional contexts, thereby enriching the global discourse on sustainable organisational development.

In conclusion, this study offers both theoretical and empirical support for the argument that ethical leadership is a significant predictor of organisational sustainability and employee performance. The alignment of leadership behaviours with ethical principles and sustainability strategies emerges as a decisive factor in shaping high-performing, resilient, and socially responsible organisations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.C. and A.I.-M.; methodology, R.C. and A.I.-M.; software, R.C. and A.I.-M.; validation, R.C. and A.I.-M.; formal analysis, R.C. and A.I.-M.; investigation, R.C. and A.I.-M.; resources, R.C. and A.I.-M.; data curation, R.C. and A.I.-M.; writing—original draft preparation, R.C. and A.I.-M.; writing—review and editing, R.C. and A.I.-M.; visualization, R.C. and A.I.-M.; supervision, R.C. and A.I.-M.; project administration, R.C. and A.I.-M.; funding acquisition, R.C. and A.I.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, as participation involved human respondents who participated voluntarily and anonymously. All participants were fully informed about the purpose of the study, the use of the questionnaire, and the handling of their data. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, ensuring the confidentiality and protection of participants’ information throughout the research process.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Participation was voluntary and anonymous, and all respondents were fully informed about the purpose and use of the questionnaire.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Due to ethical and privacy restrictions, the data are not publicly available.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Al Halbusi, H., Williams, K. A., Ramayah, T., Aldieri, L., & Vinci, C. P. (2021). Linking ethical leadership and ethical climate to employees’ ethical behavior: The moderating role of person–organization fit. Personnel Review, 50(1), 159–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedi, A., Alpaslan, C. M., & Green, S. (2016). A meta-analytic review of ethical leadership outcomes and moderators. Journal of Business Ethics, 139(3), 517–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M., & Treviño, L. (2006). Ethical leadership: A review and future directions. The Leadership Quarterly, 17, 595–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M., Treviño, L., & Harrison, D. (2005). Ethical leadership: A social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 97, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldeira, R., Moro, A. I., & Varela, M. (2024). Corporate codes of ethics, influential factors. Ramon Llull Journal of Applied Ethics. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlos, F., Vitória, A., & Dimas, I. (2025). Ethical leadership and thriving at work: Mediating role of job satisfaction. Journal of Business Ethics, 178(2), 455–472. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S., Liu, Y., Wang, J., & Houser, D. (2024). Honesty and leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 36(3), 101860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiavenato, I. (2005). Comportamento organizacional: A dinâmica do sucesso das organizações. Editora Manole. [Google Scholar]

- Cullen, J. B., Parboteeah, K. P., & Victor, B. (2003). The effects of ethical climates on organizational commitment: A two-study analysis. Journal of Business Ethics, 46, 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, M., Bhattacharjee, S., Mahmood, M., Uddin, M. A., & Biswas, S. R. (2022). Ethical leadership for better sustainable performance: Role of employee values, behavior and ethical climate. Journal of Cleaner Production, 337, 130527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R. E., & Stewart, L. (2006). Developing ethical leadership. Business Roundtable Institute for Corporate Ethics. [Google Scholar]

- Fyhn, B., Bang, H., Egeland, T., & Schei, V. (2023). Safe among the unsafe: Psychological safety climate strength matters for team performance. Small Group Research, 54(4), 439–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavas, A., & Mish, J. (2020). Resources and capabilities of triple bottom line firms: Going over old or breaking new ground? Journal of Business Ethics, 164(4), 721–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvard Business Review. (2019). How ethical leadership drives sustainability in organizations. Harvard Business Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Homer, S. T., & Lim, W. M. (2024). Theory development in a globalized world: Bridging “doing as the Romans do” with “understanding why the Romans do it”. Global Business and Organizational Excellence, 43(3), 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howe, D., Walsman, M., & Ellertson, C. (2014). Individual differences: Traits and ethical leadership. In J. Thompson, D. Hart, & D. Agle (Eds.), Research companion to ethical behavior in organizations (1st ed., pp. 161–193). Edward Elgar. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, A., & Dyaram, L. (2020). Perceived diversity and employee well-being: Mediating role of inclusion. Personnel Review, 49(5), 1121–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, C. (2013). Understanding sustainable development concept in Malaysia. Social Responsibility Journal, 9(3), 441–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Journal of Business Ethics. (2020). The role of ethical leadership in promoting voluntary pro-environmental behavior at work. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Karthikeyan, C. (2019). Organisation culture. IJMRA. ISBN 9789387176485. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, S. A. R., & Du, J. (2021). Green HRM and employee green behaviors: The role of work engagement and environmental knowledge. Sustainability, 13(4), 2101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Cabarcos, M. Á., Vázquez-Rodríguez, P., & Quiñoá-Piñeiro, L. M. (2022). An approach to employees’ job performance through work environmental variables and leadership behaviours. Journal of Business Research, 140, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, D. (2021). Ética no comportamento organizacional a importância da ética nas organizações e nos seus líderes ethics in organizational behavior the importance of ethics in organizations and their leaders. Universidade de Coimbra. [Google Scholar]

- McKinsey & Company. (2020). The impact of ethical leadership on organizational productivity and innovation. McKinsey Global Research. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, J. P., & Allen, N. J. (1997). Commitment in the workplace: Theory, research, and application (150p). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, B., & Tikoria, J. (2021). Impact of ethical leadership on organizational climate and its subsequent influence on job commitment: A study in hospital context. Journal of Management Development, 40(5), 438–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mor Barak, M. E., Luria, G., & Brimhall, K. C. (2022). What leaders say versus what they do: Inclusive leadership, policy-practice decoupling, and the anomaly of climate for inclusion. Group & Organization Management, 47(4), 840–871. [Google Scholar]

- Mulki, J. P., Jaramillo, J. F., & Locander, W. B. (2009). Critical role of leadership on ethical climate and salesperson behaviors. Journal of Business Ethics, 86(2), 125–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandy, M., & Lodh, S. C. (2022). Does sustainability disclosure improve firm performance? Evidence from emerging markets. Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal, 13(2), 313–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, L., Jordão, F., Cunha, M., Vieira, D., & Coimbra, J. (2016). Estudo de adaptação e validação de uma escala de perceção de liderança ética para líderes portugueses. Análise Psicológica, 34(2), 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Perez, F. C., & Cobra, M. (2016). Cultura organizacional e gestão estratégica: A cultura como recurso estratégico (2nd ed.). Atlas. [Google Scholar]

- Platania, S., Morando, M., & Santisi, G. (2022). Organizational climate, diversity climate and job dissatisfaction: A multi-group analysis of high and low cynicism. Sustainability, 14(8), 4458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M. E., & Kramer, M. R. (2019). Creating shared value: How to reinvent capitalism—And unleash a wave of innovation and growth. In C. Lenssen, & N. Smith (Eds.), Managing sustainable business: An executive education case and textbook (pp. 323–346). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reber, B. (2013, August 4–10). Towards participative bioethical assessment. Paper presented at the XXIII World Congress of Philosophy, Athens, Greece. [Google Scholar]

- Reiche, A. (2017). Sustainability 4.0. Available online: https://www.resilience.org/stories/2017-01-19/sustainability-4-0/ (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- Riivari, E., & Lämsä, A. M. (2014). Does it pay to be ethical? Examining the relationship between ethical organisational culture and firm performance. Journal of Business Ethics, 124(1), 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, S. P. (2002). Comportamento organizacional (7th ed.—Ética Profissional). Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, J. L., & Barling, J. (2013). Greening organizations through leaders’ influence on employees’ pro-environmental behaviors. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 34(2), 176–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenthal, S. A., & Pittinsky, T. L. (2006). Narcissistic leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 17(6), 617–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, A., Smith, L., & Chen, Y. (2024). Ethical culture in organizations: A review and agenda for future research. Business Ethics Quarterly, 34(1), 97–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandu, A., & Caras, A. (2013). Philosophical practice and social welfare. Philosophical Practice, 8(3), 1287–1296. [Google Scholar]

- Shiundu, T. W. (2024). Ethical leadership and its implication on decision-making in organizations: A literature review. Journal of Human Resource & Leadership, 8(1), 59–67. [Google Scholar]

- SHRM (Society for Human Resource Management). (2020). 2020 Culture report: Creating a culture of trust and engagement. SHRM. [Google Scholar]

- Van Gils, S., Van Quaquebeke, N., van Knippenberg, D., van Dijke, M., & De Cremer, D. (2015). Ethical leadership and follower organizational deviance: The moderating role of follower moral attentiveness. The Leadership Quarterly, 26(2), 190–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, G. R., Treviño, L. K., & Cochran, P. L. (2020). Corporate ethics practices in a global context: The role of institutional pressures and sociocultural factors. Journal of Business Ethics, 162(3), 559–576. [Google Scholar]

- Youn, H., & Kim, H. (2023). The impact of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) performance on financial performance: A systematic review. Journal of Cleaner Production, 390, 136363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusof, N. A., Said, R., Salleh, K., & Azizan, N. A. (2022). Ethical leadership, voluntary pro-environmental behaviour, and sustainable performance: The mediating role of green organizational climate. Journal of Cleaner Production, 336, 130391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).