1. Introduction

Happiness at work (HAW) has become an increasingly central theme in organizational research, reflecting a broader shift in focus toward affective experiences that influence employee well-being, motivation, and performance (

Al-Shami et al., 2023;

El-Sharkawy et al., 2023;

Farooq et al., 2024;

Fröhlich et al., 2025;

Salas-Vallina & Fernandez, 2017). Despite this growing interest, the conceptualization of HAW remains fragmented and contested. There is still no agreement on whether happiness at work should be understood as a transient emotional state, a stable personality trait, or a multidimensional construct integrating affective, cognitive, and behavioral components (

Farooq et al., 2024). This lack of definitional clarity hinders theoretical integration and limits the development of effective measurement instruments and interventions.

Much of the existing literature on work happiness is divided between models that emphasize job satisfaction and evaluative judgments, and those that focus on momentary affective experiences or emotional vitality. For example,

Fisher (

2010) conceptualizes HAW as a composite of satisfaction, engagement, and commitment—blending hedonic and eudaimonic perspectives. In contrast, affective models foreground emotions such as joy, pride, or gratitude (

Fredrickson, 2013;

Elfenbein, 2023), and philosophical frameworks distinguish between happiness as life evaluation (

Kahneman & Riis, 2005;

Goldman, 2017) and happiness as an emotional response to specific contexts (

Perrotta et al., 2023;

Ravina-Ripoll et al., 2024).

Building on these debates, this study responds to recent calls to move beyond top-down models that impose predefined categories and instead explore how employees themselves experience and describe happiness at work (

Singh & Aggarwal, 2018;

Villanueva et al., 2021). While existing research has often conflated antecedents and outcomes—treating work happiness as either the presence of autonomy, the absence of stress, or the presence of satisfaction—this study argues for conceptual separation. Drawing on means–goal theory (

Glaser, 1978;

Asante Boadi et al., 2020), I propose a dual-structure model in which organizational and interpersonal factors serve as sources (means), and discrete emotions serve as psychological outcomes (goals). This distinction aims to address the unfulfilled conceptual promise of HAW research by providing a more precise, testable framework.

The theoretical foundation of this study integrates three main perspectives. First, self-determination theory (

Deci & Ryan, 2008) provides a motivational lens, highlighting the importance of autonomy, competence, and relatedness as basic psychological needs that contribute to well-being. Second, theories of emotion—including appraisal theory (

Clore & Ortony, 2008;

Frijda, 2009) and sociocultural perspectives (

Goodwin et al., 2001;

Gordon, 1990)—clarify how emotional responses are shaped by situational triggers and institutional environments. Third, the Perrotta Human Emotions Model (PHEM-2) contributes an analytic framework that traces how emotions arise from stimuli and unfold through reactions, feelings, and adaptive responses (

Perrotta et al., 2023). PHEM-2 informs the study’s distinction between organizational sources and emotional experiences, offering a bridge between contextual inputs and psychological outcomes.

To address the gap between theory and lived experience, this study adopts an inductive, mixed-methods design. In the first stage, qualitative data are used to identify employee-generated categories of happiness through thematic analysis. In the second stage, an exploratory factor analysis is used to derive and validate a measurement scale based on those categories. This empirical strategy offers both conceptual depth and psychometric structure, helping to clarify how work happiness is experienced and how it might be meaningfully assessed.

Moreover, this study contributes to the growing body of cross-disciplinary and context-sensitive research on emotions at work. Prior studies have highlighted the importance of recognizing the cultural and organizational specificity of emotional norms and expressions (

Schroeder & Schroeder, 2014;

Fröhlich et al., 2025). In line with this, the study’s Norwegian setting—characterized by high levels of job autonomy and egalitarianism—offers a unique opportunity to explore how work happiness emerges in low-hierarchy, high-trust environments.

To summarize, this article offers three interrelated contributions to the literature on work happiness. First, it provides theoretical refinement by clarifying the distinction between contextual sources and emotional outcomes, thus advancing a dual-structure model of HAW. Second, it introduces an empirically grounded measurement approach based on employee narratives and inductive analysis. Third, it enhances practical relevance by offering organizations a framework to assess and foster happiness through emotionally meaningful interventions. These contributions are guided by two central research questions: What are the primary sources of happiness at work, and what emotional experiences are associated with these sources?

2. Theory

2.1. Sources, Emotional Experiences, Feelings and Adaptive Responses

To advance conceptual clarity on the construct of happiness at work (HAW), this study focuses on two under-theorized yet foundational dimensions: (1) the sources or antecedents that elicit positive work-related emotions, and (2) the emotional experiences and adaptive responses that constitute workplace happiness. Unlike traditional models that subsume emotions under attitudinal outcomes like job satisfaction or engagement (

Fisher, 2010), this framework emphasizes the distinctive and mediating role of emotions that, according to related theories, shape work motivation, well-being, and adaptive functioning (

Fredrickson, 2013;

Elfenbein, 2023).

Workplaces are inherently emotional environments—socially structured and affectively charged (

Elfenbein, 2023). Emotional experiences (

Singh & Aggarwal, 2018;

Villanueva et al., 2021;

Weiss & Cropanzano, 1996) arise not only from interpersonal relationships but also from systemic conditions such as fairness, recognition, and leadership (

Ravina-Ripoll et al., 2024). These sources, sometimes conceptualized as part of the “emotional wage” (

Ravina-Ripoll et al., 2024), act as triggers for discrete emotional responses. As

Clore and Ortony (

2008, p. 632) put it, emotions are “affect-laden reactions to different situational structures.” Emotions, in this view, are not only reactions but also mechanisms that inform and regulate behavior, driving adaptive responses to one’s environment (

Shuman & Scherer, 2014).

From a psychological perspective, emotions are complex phenomena encompassing physiological arousal, cognitive appraisal, behavioral intentions, and expressive components (

Frijda, 2009;

Gross, 2008). Positive emotions, in particular, are theorized to broaden thought-action repertoires and foster enduring psychological resources such as resilience, optimism, and social connectedness (

Fredrickson, 2013;

Cohn et al., 2009). This has been empirically demonstrated in workplace studies linking mindfulness and resilience to emotional well-being and work happiness (

Le et al., 2024;

Coo & Salanova, 2017).

To model these sequences more explicitly, this study draws on the revised Perrotta Human Emotions Model (PHEM-2) (

Perrotta et al., 2023), which traces emotions from their eliciting sources (e.g., autonomy, recognition) to intermediate affective states (e.g., joy, cheerfulness), and finally to adaptive responses (e.g., creativity, perseverance, workplace happiness). This layered conceptualization aligns with psychotherapeutic and evolutionary approaches, viewing emotions as tools for psychological adaptation and social signaling (

Fredrickson et al., 2008;

Shuman & Scherer, 2014). For example, workplace recognition may elicit pride or joy, which in turn fosters feelings of cheerfulness and ultimately leads to behaviors such as generosity, humor, or increased engagement. This sequential framing mirrors findings in the field of transformational leadership and emotional wage, where emotionally attuned environments promote not only job satisfaction but also deeper experiences of belonging, loyalty, and meaning (

Al-Hadrawi et al., 2023;

Ravina-Ripoll et al., 2024).

Recent organizational studies similarly stress the dynamic role of emotions as both outcomes and mediators. For example, mindfulness and resilience have been shown to mediate the relationship between work–life conflict and happiness (

Le et al., 2024), while internal factors like emotional wage and perceived justice contribute to emotional well-being and organizational commitment (

Ravina-Ripoll et al., 2024;

Gulyani & Sharma, 2018). These findings reinforce the importance of including emotional dimensions when theorizing about work happiness—not merely as endpoints but as mechanistic pathways linking environmental triggers and long-term employee outcomes (

Al-Hadrawi et al., 2023).

Additionally, the cultural variability of emotional responses underscores the value of qualitative and exploratory approaches. Emotions are socially constructed to a degree, with meaning and expression varying across professional roles, leadership climates, and organizational cultures (

Shuman & Scherer, 2014;

Elfenbein, 2023).

In sum, by conceptualizing happiness at work as a dual-structured construct—comprising both emotional experiences, outcomes and their eliciting sources, this study responds to calls for more nuanced, multidimensional models of workplace well-being (

De Simone & Franco, 2023;

Fisher, 2010). Drawing on theory and evidence from positive psychology, emotion theory, and organizational behavior, it frames emotional experiences not only as indicators of work happiness but as core constituents of how workplace experiences are internalized and acted upon.

2.2. Happiness at Work, Well-Being, and Measurements

Despite the proliferation of studies on happiness and well-being, definitional and conceptual ambiguity persists—particularly in organizational research. Happiness is variably treated as a transient affective state, a stable trait, or a cognitive evaluation of life satisfaction, depending on the disciplinary lens employed (

Ravina-Ripoll et al., 2024;

Fisher, 2010). This diversity in conceptualization is especially pronounced in workplace settings, where happiness is often conflated with related constructs such as job satisfaction, work engagement, and commitment (

Al-Hadrawi et al., 2023). As

Goldman (

2017) argues, the lack of terminological clarity impedes both theoretical development and empirical measurement.

To move beyond these limitations, this study adopts a multidimensional and emotionally grounded perspective on happiness at work (HAW). I distinguish between the sources of happiness (e.g., autonomy, recognition, support) and the emotional responses they elicit (e.g., joy, serenity, interest), following a growing recognition that happiness at work is not a monolithic state but an emergent outcome of affective episodes embedded in social contexts (

Fredrickson, 2013;

Elfenbein, 2023;

Ravina-Ripoll et al., 2024). In contrast to cumulative satisfaction models, I conceptualize work happiness as a dynamic process shaped by contextual triggers and mediated by emotional, psychological, and behavioral mechanisms.

This approach aligns with the engine model of well-being proposed by

Jayawickreme et al. (

2012), which conceptualizes well-being as a function of input factors (e.g., work conditions), cognitive-affective processes (e.g., emotion regulation), and outcome states (e.g., thriving, performance). Within this framework, happiness is both a determinant and an outcome of well-being, mediated by positive emotions, adaptive functioning, and social connectivity (

Alexander et al., 2021). Organizational research has similarly emphasized the value of positive affect as a driver of engagement, innovation, and resilience (

Le et al., 2024;

Coo & Salanova, 2017).

Crucially, this layered structure allows for a more granular measurement strategy. Instead of treating HAW as a latent, monolithic variable, I explore how specific sources (e.g., interpersonal climate, autonomy) are associated with discrete emotional reactions (e.g., joy, contentment, gratitude). This distinction helps address a common shortcoming in the field—namely, the tendency to aggregate affective, cognitive, and behavioral indicators into composite scales without examining their distinct trajectories or interrelations (

Gulyani & Sharma, 2018;

Singh & Aggarwal, 2018).

Indeed, recent calls for more context-sensitive, inductive approaches to work happiness (e.g.,

Singh & Aggarwal, 2018;

Ravina-Ripoll et al., 2024) emphasize the importance of aligning measurement instruments with the lived emotional realities of workers. The study responds to this need by generating scale items from qualitative data and grounding them in emotion theory and adaptive behavior models. This inductive strategy facilitates a closer alignment between conceptual dimensions and their psychometric indicators—thereby improving construct validity.

Moreover, existing measures of HAW—such as those informed by

Fisher’s (

2010) tripartite model—tend to emphasize stable attitudes and overlook the episodic and context-dependent nature of happiness (

Salas-Vallina & Alegre, 2021;

Kassim et al., 2013). While useful for capturing general affective tone, such instruments are less suited for analyzing how specific work experiences give rise to emotional states that influence well-being and performance. By focusing on emotional episodes and their antecedents, this approach is more aligned with emerging paradigms in positive organizational scholarship and transformative service research (

Le et al., 2024).

In sum, this study contributes to the evolving literature on work happiness by proposing a model that:

Separates emotional experiences from their contextual sources,

Accounts for adaptive behavioral outcomes, and

Suggest inductively derived, theoretically grounded measurement strategies.

3. Materials and Methods

This exploratory inductive mixed-method study on work happiness adopted a research design comprising a preliminary investigation and a primary study, utilizing both qualitative and quantitative methodologies (

Patton, 2014;

Yauch & Steudel, 2003). Qualitative data pertaining to the sources and emotional experiences associated with work happiness were derived from written statements and descriptions provided by adult students, which were then subjected to analysis (

Baxter & Jack, 2008). Applied thematic analysis is valuable as documents are stable, and they may cover a wide range of topics (

Yin, 2013). The application of thematic analysis to the submissions proved valuable in providing researchers with insights into the sources of work happiness as described by respondents and the corresponding emotional experiences (

Pitney & Parker, 2009).

Furthermore, enhancing the credibility and dependability dimensions, discussions with students were incorporated after the thematic analysis (

Golafshani, 2003;

Morrow, 2005). The study adhered to an exploratory sequential design (

Creswell & Creswell, 2017), utilizing an inductive method (

Boateng et al., 2018). In the subsequent quantitative main study, it was decided to incorporate a few hundred regular employees, not exclusively union representatives (albeit Parat members). In challenging existing original research that underlies work happiness measurement scales, I collected and analyzed qualitative data regarding the sources and emotional experiences of work happiness. Subsequently, potential variables were identified during the pre-study phase. In the main study, an Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was applied, following the steps outlined by

Boateng et al. (

2018), to identify and suggest factors representing sources and emotional experiences of work happiness. The sections delineating the preliminary and main studies present the procedural elements, data collection processes, analyses, and findings.

3.1. Data Collection Approach of Initial Study

In the initial qualitative inquiry, 23 part-time adult students from Norway’s public and private sectors participated in a 12-week course on work happiness, leadership, and self-leadership during spring 2023. All participants were experienced union representatives and employees, selected through a collaboration with Parat—a politically independent labor union with approximately 41,000 members across diverse sectors including aviation, media, healthcare, police, and the armed forces. Parat is affiliated with the Norwegian Confederation of Vocational Unions and comprises nine sub-associations, including Parat Media, Norwegian Pharmacy Association, National Dental Assistant Association, Norwegian Association of the Chiefs of Police, Parat Army, Parat Cabin Staff Association, and Norwegian Pilot Union. Participants in this study represented seven of the nine sub-associations, offering broad insights into different professions and organizational roles.

As part of this collaboration, the course participants acted as informants for the initial study, contributing to the exploration of sources and emotional experiences during the item generation phase (

Boateng et al., 2018). Before enrolling in the course, potential participants received information about the research project and gave written consent to participate as anonymous informants. Prior to the course commencement and syllabus distribution, they submitted individual written reflections as part of a portfolio assignment. In this task, they were asked to describe a specific instance in which they had experienced work happiness, and to recall and reflect on the emotional experiences they had experienced during that situation. Instructions, tasks, and submissions were managed via the Canvas learning platform. Submission and thematic analyses were completed in two rounds.

3.2. Sample

The sample included employees from seven of Parat’s nine sub-associations, representing diverse sectors and a wide range of professions, job roles, and organizational types across the public and private sectors. These full-time working, part-time students, functioning as both employees and union representatives, may be argued to represent both groups. The informants comprised approximately 60% women and 40% men, aged between 35 and 65, with most being experienced union representatives. Although the use of part-time adult students (working full time) in a professional course qualifies as a convenience sample (

Peterson & Merunka, 2014), the dual roles of participants as employees and union representatives from diverse sectors added breadth and credibility to the findings.

3.3. Analysis

The initial round of thematic analysis was based on individually written reflections submitted by participants prior to the start of the course, to minimize potential influence from course content. An inductive approach to extract key experiences of work happiness grounded in their own language was applied (

Creswell & Creswell, 2017;

Braun et al., 2016). Narrative fragments were treated as data-rich micro-stories, in line with

Elliott’s (

2005) emphasis on the power of narrative to reveal subjective meaning and situated emotion. Following the principle of ecological validity (

Barthes, 1977), particularly relevant in textual research, vivid statements with emotional and contextual clarity were retained verbatim as potential survey items.

To increase narrative saturation and trustworthiness, a second qualitative round was conducted during the participants’ first classroom session. Randomly assigned to triads, participants peer-reviewed each other’s narratives, co-constructed short vignettes based on shared experiences, and revised their reflections accordingly. This dialogical method, emphasizing collaborative sensemaking, aligns with

Glaser’s (

2008) view of qualitative analysis as a continuous comparative process where data are enriched through interaction. A second thematic coding process was then conducted to refine the emerging structure, validate initial categories, and enhance content validity (

Boateng et al., 2018).

Item selection from qualitative material was governed by several criteria. First, quotes had to be thematically aligned with one of the emerging categories. Second, expressions needed to occur in at least five distinct individual accounts to ensure relevance and recurrence. Third, quotes were compared for linguistic clarity and conceptual uniqueness; redundant or overlapping expressions were excluded to avoid construct contamination (

Spiggle, 1994). Fourth, items were only retained if they clearly reflected a psychological construct rather than a behavioral intention or generic appraisal (e.g., “I get in a good mood” was preserved as a representation of affective tone, not as a fleeting state).

Two independent coders developed the codes and conducted item screening, using both open and axial coding to reduce individual bias (

Glaser, 2008). The process yielded five preliminary themes: (1) Specific situations, (2) Work task and meaning, (3) Autonomy, (4) Recognition, and (5) Emotional experiences.

The final mapping of codes to items was guided by

Glaser’s (

1978) “means–goal” coding family, which frames contextual factors (means) as enablers of desirable emotional outcomes (goals). In addition, Perrotta’s Human Emotions Model (PHEM-2) helped differentiate the types of emotions referenced (basic, complex, and self-conscious), while Fredrickson’s broaden-and-build theory (2001) offered a framework for interpreting how frequent emotional states might accrue into longer-term well-being. This multi-layered approach ensured theoretical grounding, contextual sensitivity, and emotional specificity in the item pool construction.

3.4. Results of Initial Study

The initial qualitative study generated a rich and diverse set of narrative reflections on what happiness at work means to employees. Through thematic analysis of these submissions, a structured item pool was developed to reflect the emotional and contextual nuances expressed in participants’ own words. A total of 49 candidate survey items were extracted from the data (see

Table 1), carefully selected based on their theoretical relevance, recurrence across responses, and vividness of expression. This process ensured that each item retained a high degree of ecological validity, as originally conceptualized by

Barthes (

1977), and allowed participants’ voices to shape the operationalization of the construct.

Rather than relying on predefined categories, the analysis surfaced a range of emotionally salient situations, personal values, and interpersonal dynamics that employees linked to their experience of happiness at work. Several of these expressions were incorporated directly into the measurement instrument to preserve their authenticity and theoretical grounding. These participant-derived statements, exemplified under the overarching themes below, reflect the dual nature of work happiness—as both situationally triggered and emotionally enduring—aligning with

Fisher’s (

2010) view that happiness arises from the interplay between events and organizational structures.

Participants often referred to concrete episodes that triggered positive emotions at work. These situations typically involved successful completion of tasks or receiving feedback from others.

“We received good feedback from a customer.”

“I managed to solve a task I found difficult.”

Such events were described as emotionally uplifting, providing a sense of pride, mastery, or relief. They illustrate how even brief episodes can serve as meaningful sources of happiness.

Happiness at work was closely associated with performing meaningful tasks. Participants emphasized the value of helping others, using their skills, and working in ways aligned with personal values.

“When I get to help others, I feel good.”

“When I can use my skills, I am happy.”

“I find the task meaningful.”

These reflections highlight the intrinsic motivation and sense of purpose that emerge from meaningful work, often leading to emotions such as joy, satisfaction, and pride.

A recurring theme was the importance of autonomy—being able to influence one’s own work, organize the workday, and make independent decisions.

“I can influence my work.”

“I get to plan my workday.”

“I have freedom at work.”

Participants linked autonomy to feelings of motivation, calm, and engagement. It was seen as a stabilizing force and a key contributor to daily well-being.

Recognition from leaders, colleagues, or clients was repeatedly mentioned as a vital source of happiness. Being acknowledged—formally or informally—was tied to emotional validation and belonging.

“I feel seen.”

“I get praise.”

“I am appreciated by colleagues or leader.”

These statements were associated with emotions like pride, gratitude, and increased self-worth, suggesting that recognition serves both relational and emotional functions in the workplace.

Participants also described the emotional outcomes of positive work experiences in simple yet powerful terms, reflecting both transient moods and sustained affective orientations.

“I feel inner peace.”

“I’m in a good mood.”

“I look forward to going to work.”

These responses illuminate how happiness is experienced as both momentary and enduring emotional states, ranging from calm and cheerfulness to motivational anticipation.

3.5. Discussion of Initial Study

This study explored the multifaceted nature of happiness at work by inductively identifying five empirically grounded themes from qualitative narratives: specific situations, work task and meaning, autonomy, recognition, and emotional experiences. These themes represent both structural conditions and lived experiences that employees associate with happiness in the workplace. The findings contribute to ongoing theoretical debates by offering a context-sensitive and ecologically valid model of how work happiness is perceived and emotionally experienced by employees.

The results align closely with emotion theory, particularly the framework proposed by

Clore and Ortony (

2008), who argue that emotions arise from individuals’ appraisals of situational structures. In the present study, participants described moments such as receiving feedback, solving a complex task, or being appreciated by a leader—all examples of emotionally charged situations that triggered feelings of pride, calm, or joy. Similarly,

Gordon (

1990) and

Goodwin et al. (

2001) maintain that emotions are not isolated reactions but are embedded in institutional and organizational life. This supports the notion that work happiness is shaped by situational triggers that are socially and structurally mediated.

The emotional outcomes described by participants are consistent with

Perrotta et al.’s (

2023) argument that emotions such as joy, frustration, or guilt generate feelings like trust, dissatisfaction, or cheerfulness, which in turn influence adaptive reactions (e.g., humor) and responses (e.g., happiness). This sequential process—from stimulus to emotion, feeling, and response—mirrors the logic of the thematic structure uncovered in this study. It also supports the interpretation that emotional experiences such as “feeling inner peace” or “looking forward to going to work” are not isolated states but emergent outcomes of meaningful, appraised work-based experiences.

In line with

Goldman’s (

2017) assertion that happiness can itself be considered an emotion, the qualitative findings in this study suggest that emotional experiences—such as cheerfulness, calm, and positive anticipation—are not only outcomes of workplace events but may constitute work happiness itself. The 14 preliminary items under the emotional experiences theme reflect this nuanced view, emphasizing both momentary moods and more enduring affective states.

The theme of autonomy, in particular, resonates with self-determination theory, where autonomy is identified as a basic psychological need essential to eudaimonic well-being (

Ryan et al., 2008). Autonomy in this study was expressed through items such as “I can influence my work” and “I get to plan my workday,” reflecting both perceived control and intrinsic motivation. Relatedness and competence—self-determination theory’s two additional needs—were also evident in participants’ narratives. For example, the statement “There is good humor among us who work together” reflects relatedness, while “I am strengthening my knowledge” links to competence. This alignment supports the broader theoretical claim that satisfaction of psychological needs is fundamental to experiencing happiness at work.

The findings regarding work task and meaning and recognition are supported by recent quantitative research by

Charles-Leija et al. (

2023), which documented that meaningful work and feeling appreciated by colleagues significantly enhance happiness at work. Participants in this study similarly emphasized the satisfaction derived from helping others, using their skills, and receiving praise or gratitude. These expressions reflect both hedonic and eudaimonic dimensions of well-being, reinforcing the idea that work happiness arises not only from pleasure or comfort, but also from purpose and social affirmation.

Finally, the category of emotional experiences is itself supported by theories that emphasize the role of emotion in workplace dynamics.

Clore and Ortony (

2008) describe how emotions emerge from appraisals of situations, while

Gulyani and Sharma (

2018) and

Ravina-Ripoll et al. (

2024) argue that emotional experiences can be categorized, measured, and linked to well-being outcomes. The present study’s use of expressions such as “good mood,” “inner peace,” and “look forward to going to work” provides empirical grounding for this theoretical position and supports their inclusion as emotional outcomes of specific work conditions.

Taken together, the qualitative results and theoretical insights suggest that specific workplace features—such as autonomy, recognition, and meaningful tasks—act as antecedents to emotional experiences that employees describe as happiness. These results support a dynamic model of work happiness as an interaction between structural sources and affective responses. By identifying these themes inductively from employee narratives, this study contributes to a more grounded and experientially valid understanding of how happiness is created and sustained in organizational contexts.

4. Materials and Methods of Main Study

4.1. Scale Development

The quantitative phase of this mixed-method study aimed to explore scales for measuring sources and emotions of work happiness, based on the themes and items identified during the preliminary qualitative inquiry. This phase followed an exploratory sequential design (

Creswell & Creswell, 2017), combining inductive item development with empirical scale exploration. To address face and content validity, a panel of six expert practitioners and researchers in the fields of psychology, HR, and organizational development independently reviewed the initial 49 items for clarity, relevance, and representativeness. In addition, six employees at Parat’s central office conducted a pre-test of the survey instrument, offering feedback on language and ambiguity. Based on this feedback, minor revisions were made to improve wording and alignment with intended constructs (

Boateng et al., 2018).

The final survey included 35 items measuring sources of work happiness and 14 items measuring emotional experiences of work happiness, grounded in both theory and participant-generated expressions. All items were rated using a seven-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree). Demographic variables such as gender, age, educational background, employment sector, occupation, and union role were also collected to allow for subgroup analyses and external validation.

4.2. Data Collection, Sample and Respondent Characteristics

In June 2023, the questionnaire was distributed by the central administration of Parat to approximately 4000 members, including around 1000 individuals who were regular employees and not serving as union representatives. The survey remained open for ten working days and yielded 630 responses, of which 615 were retained after excluding incomplete submissions and conducting quality control checks.

Of the final sample, 64.5% identified as women and 35.5% as men. Approximately 70% were union representatives, while the remaining 30% were non-representatives. Sectoral affiliation included 44% from the private sector and 56% from the public sector. Respondents ranged in age from 22 to 70, offering a wide age distribution. Educational attainment varied: 9% held a master’s degree, 21% had a bachelor’s degree, and 45% had completed 12 years of formal education. The sample included individuals from diverse occupational backgrounds such as aviation, healthcare, policing, education, and media.

While this diversity supports variation in experience and enhances exploratory validity, the dual identity of the qualitative respondents—as both employees and union representatives—warrants reflection. Participants were enrolled in a leadership course explicitly centered on work happiness and self-leadership, which may have influenced their articulation of valued work sources and emotional expressions. Classroom discussions and peer feedback used to revise individual narratives may also have introduced framing effects or social desirability tendencies. These epistemic implications are discussed further in the limitations section. Nevertheless, the sample provided valuable insight into the lived experiences of employees engaged in both work and organizational advocacy roles.

4.3. Exploratory Factor Analysis

To assess the psychometric properties of the proposed scales measuring work happiness, an Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was conducted following established best practices in scale development (

Howard, 2016;

Boateng et al., 2018). Prior to the EFA, the suitability of the data was confirmed using Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity (χ

2 = 42,792.79, df = 4753,

p < 0.001), indicating that correlations between items were sufficiently large for factor analysis. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy was 0.955, far exceeding the recommended minimum of 0.50 (

Williams et al., 2010), and confirming excellent conditions for factor extraction. The sample size of 615 also met the threshold for robustness and reliability in EFA (

Hair et al., 2015). I applied Maximum Likelihood as the extraction method, combined with Oblimin rotation and Kaiser Normalization (

Osborne et al., 2008). Items with factor loadings below 0.40, or with high cross-loadings, were systematically removed to ensure convergent and discriminant validity (

Hair et al., 2015). This process resulted in a seven-factor solution that was both interpretable and theoretically coherent, reflecting the dimensions identified in the qualitative phase: togetherness toward goals, harmonious employee relations, meaning at work, self-development, autonomy, recognition, and emotional experiences of work happiness (see

Table 2 for factor loadings, internal consistency, and descriptive statistics).

Each construct demonstrated strong internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alpha values ranging from 0.80 to 0.86 and McDonald’s Omega values from 0.81 to 0.87, thereby confirming reliability (

Hair et al., 2015). Inter-item correlations between constructs ranged from 0.33 to 0.68, well within the accepted range of 0.30 to 0.80 (

Diamantopoulos et al., 2012), except for a low correlation of 0.10 between autonomy and harmonious employee relations, which reflects their conceptual distinctiveness rather than measurement error. Multicollinearity diagnostics yielded Tolerance values between 0.49 and 0.77, and Variance Inflation Factors (VIFs) from 1.3 to 2.0, further confirming the absence of problematic multicollinearity. The eigenvalues and explained variance for the extracted factors were: 27.8/30.2%, 8.3/9.0%, 3.1/3.4%, 3.0/3.2%, 2.6/2.8%, 2.0/2.2%, and 1.8/1.9%. Together, the seven factors explained a substantial proportion of variance in the data, reinforcing the multidimensional nature of the work happiness construct.

To ensure construct validity, I examined whether item clusters aligned with existing theoretical definitions from the fields of positive psychology, organizational behavior, and emotion theory (

Fisher, 2010;

Fredrickson, 2001;

Perrotta et al., 2023). All retained items reflected conceptually coherent groupings—such as autonomy (“I can influence my own work”) or emotional well-being (“I look forward to going to work”)—indicating that the factor structure mirrored theoretically grounded constructs. Taken together, the EFA results, reliability indicators, and validity assessments provide strong evidence that the newly developed scales are psychometrically sound, theoretically valid, and suitable for further use in regression models of work happiness.

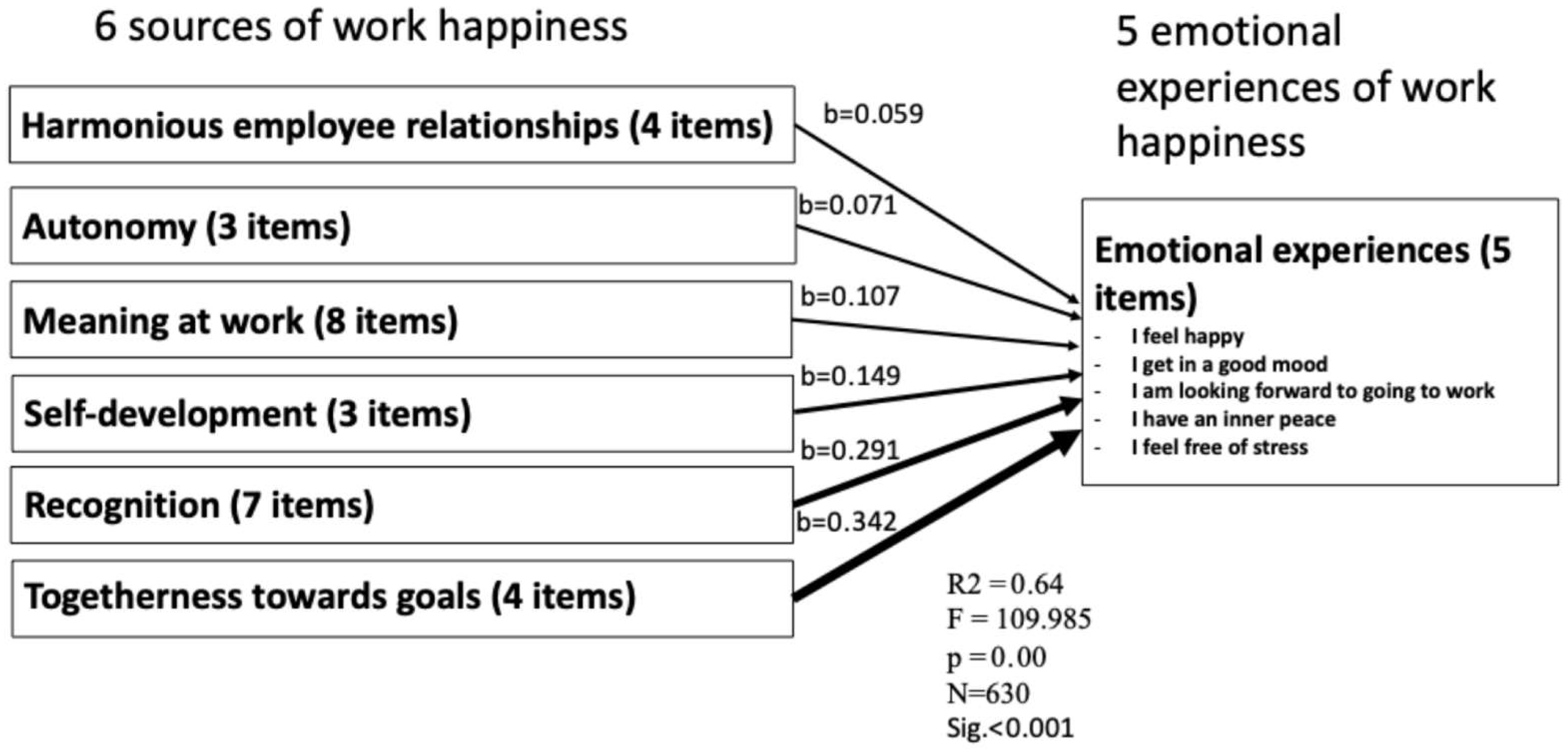

5. Results

I explored whether the argued relationships between the identified sources of work happiness and emotional experiences of work happiness were supported empirically. Drawing on means–goal theory (

Glaser, 1978), which posits that contextual factors (means) give rise to desirable psychological outcomes (goals), I conducted a multiple regression analysis. The dependent variable was emotional experiences of experienced work happiness, and the six independent variables were the identified dimensions from the factor analysis: togetherness towards goals, harmonious employee relations, meaning at work, self-development, recognition, and autonomy (see

Table 2 for factor structure and descriptive statistics). The regression model was statistically significant (R

2 = 0.64, F = 109.99,

p < 0.001), indicating a substantial proportion of variance in emotional experiences of work happiness explained by the proposed sources. All six independent variables had a positive and significant effect on the dependent variable (see

Table 3). Specifically, ranked according to the strength of the β.

Among the six independent variables, togetherness towards goals had the strongest standardized regression coefficient (β = 0.342, p < 0.001), suggesting that perceptions of social cohesion and shared responsibility are strongly associated with emotional experiences of work happiness. Recognition also demonstrated a substantial effect (β = 0.291, p < 0.001), emphasizing the emotional significance of being valued and appreciated in the workplace. Self-development showed a moderate association (β = 0.149, p < 0.001), reflecting the importance of opportunities for growth and learning. Likewise, meaning at work was significantly related to emotional experiences (β = 0.107, p < 0.001), indicating that feelings of purpose and contribution play a meaningful role in employees’ affective well-being. Autonomy (β = 0.071, p = 0.02) also showed a statistically significant but smaller effect, pointing to the relevance of having influence over one’s own work. Finally, harmonious employee relations (β = 0.059, p = 0.03) contributed modestly, yet significantly, to emotional experiences of work happiness, underlining the value of pleasant interpersonal dynamics. Harmonious employee relations (β = 0.059, p = 0.03) show the importance of pleasant social and employee relations.

To ensure the robustness of the model, I also included control variables such as age, gender, education, and union status (whether the respondent was a union representative or a regular member). None of these demographic variables had a significant impact on the dependent variable, suggesting that the emotional outcomes of work happiness were not systematically influenced by demographic characteristics (see

Table 3 for regression summary). These results suggest a measurement model and support the underlying theoretical assumption that emotional experiences of work happiness are associated by distinct and measurable organizational and interpersonal sources. The strong explanatory power of the model (R

2 = 0.64) provides compelling evidence for the conceptual distinction between sources and emotional experiences and suggests their inclusion as separate constructs in the study of work happiness.

6. Discussion

This study set out to explore the multifaceted nature of work happiness by moving beyond traditional, top-down models and instead adopting a two-stage inductive and exploratory approach. Drawing from theories of emotion, positive psychology, and organizational behavior, the study contributes to the ongoing clarification of the work happiness construct—both conceptually and empirically (

Farooq et al., 2024;

Fisher, 2010;

Singh & Aggarwal, 2018;

Salas-Vallina & Alegre, 2021).

The initial qualitative study provided rich, grounded insights into how employees describe and experience happiness at work. Thematic analysis revealed five core categories: specific situations, work task and meaning, autonomy, recognition, and emotional experiences. These categories reflected recurring expressions of affective reactions to daily events, interpersonal dynamics, and job characteristics—findings that resonate with the notion that emotions in the workplace are tied to situational appraisals and embedded in social and institutional contexts (

Clore & Ortony, 2008;

Goodwin et al., 2001;

Gordon, 1990). Using vivid participant narratives, the analysis also generated 49 preliminary items that reflect this experiential structure of happiness, offering the basis for scale development.

The quantitative phase then subjected these items to exploratory factor analysis and revealed a six-dimensional structure of work happiness sources: togetherness towards goals, harmonious employee relations, meaning at work, self-development, recognition, and autonomy. These factors capture a broad but differentiated view of the organizational conditions associated with happiness at work. The dimension “togetherness towards goals” elaborated and extended the preliminary category “specific situations” by emphasizing team-oriented processes and social belonging rather than episodic events. Similarly, “harmonious employee relations” refined interpersonal aspects implicit in both emotional expressions and group dynamics from the qualitative phase. While the initial qualitative study yielded five overarching themes, the exploratory factor analysis refined and extended these into six distinct dimensions. For instance, the qualitative theme ‘specific situations’ was further differentiated into ‘togetherness towards goals’ and ‘harmonious employee relations’, highlighting more nuanced social aspects of workplace experiences. The factor “harmonious employee relations,” which emerged from the exploratory factor analysis, captures a distinct set of interpersonal qualities related to affective safety, mutual appreciation, and emotionally supportive work climates. While conceptually adjacent to constructs such as team climate and social support (

Chiaburu & Harrison, 2008), this factor is better understood as describing the everyday relational dynamics that foster ease, mutual attunement, and informal affective exchanges such as shared humor or emotional uplift.

These features are echoed in

Bjerke’s (

2024) qualitative study of executive MBA students, where emotionally meaningful relationships and interpersonal connectedness were related to well-being, calm, and motivation (see

Table 3). Participants emphasized the role of mutual care, respect, and low-threshold social contact in maintaining emotional balance—factors that go beyond formalized team support structures. As such, the present construct of harmonious employee relations may be seen as a more affectively embedded and relationally nuanced concept, grounded in the lived experience of workplace happiness rather than only its functional or instrumental dimensions.

Multiple regression analysis confirmed that all six identified sources were significantly and positively associated with emotional experiences of work happiness. Notably, “togetherness towards goals” emerged as the strongest predictor, followed by recognition and self-development. These findings support emotion theories that conceptualize happiness not only as a transient affective state but because of repeated emotional episodes embedded in meaningful workplace interactions (

Fredrickson et al., 2008;

Weiss & Cropanzano, 1996). Furthermore, they align with research showing that social connection, appreciation, and personal growth are central to emotional well-being at work (

Charles-Leija et al., 2023;

Deci & Ryan, 2008).

Self-determination theory provides a particularly strong theoretical foundation for interpreting the results. The dimensions of autonomy, self-development, and togetherness towards goals map closely onto the three universal psychological needs of autonomy, competence, and relatedness (

Deci & Ryan, 2008). Recognition and meaning at work also reflect motivational affordances that satisfy these needs, thereby fostering sustainable forms of work happiness. The association between interpersonal themes (e.g., harmonious relations) and positive emotions further reflects how workplace emotions are shaped by both individual perceptions and collective dynamics (

Shuman & Scherer, 2014;

Gulyani & Sharma, 2018).

Taken together, the results suggest that work happiness can be understood as a dynamic interplay between organizational conditions (sources) and emotional experiences (outcomes).

Perrotta et al. (

2023) emphasize that emotional stimuli in social environments give rise to reactions, feelings, and adaptive responses—a theoretical model supported here by the empirical link between work structures and reported affective states. These findings reaffirm that happiness at work is not reducible to job satisfaction or mood alone, but rather emerges through a contextualized process involving meaning, recognition, agency, and social connection.

However, these insights must be interpreted considering certain limitations. The qualitative phase drew on a relatively small and bounded sample of union representatives, potentially introducing selection bias and priming effects. The exploratory nature of the study precludes definitive conclusions about causality, and no confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted to validate the factor structure in an independent sample. Some categories, particularly “togetherness towards goals,” may also encompass several subdimensions that warrant future disaggregation and refinement. Moreover, cultural specificity remains a concern, given the Norwegian context characterized by egalitarian work structures and high autonomy.

Despite these limitations, the study provides a novel and ecologically valid contribution to the work happiness literature by integrating grounded employee perspectives with theory-driven empirical modeling. It supports a more nuanced view of work happiness—one that is emotionally rich, socially embedded, and responsive to organizational conditions. Future research should validate this model across different cultural settings, extend it through longitudinal designs, and explore how specific interventions targeting these sources may promote sustainable emotional well-being in the workplace.

7. Theoretical Implications

This study contributes to the field of work happiness by offering a more differentiated and empirically grounded understanding of the construct. Through an exploratory and inductive methodology, I identified six distinct sources—togetherness towards goals, harmonious employee relations, meaning at work, self-development, recognition, and autonomy—and five emotional experiences—happiness, good mood, looking forward to work, inner peace, and freedom from stress (see

Figure 1). This approach challenges dominant conceptualizations of work happiness as an umbrella construct encompassing job satisfaction, work engagement, and affective organizational commitment (

Fisher, 2010;

Salas-Vallina et al., 2017;

Salas-Vallina & Alegre, 2021), and instead advances a more granular, multi-dimensional perspective rooted in lived experiences. This six-dimensional structure also provides a more differentiated and empirically testable framework for future scale validation and theory development, as clarified in the discussion of how the qualitative categories were refined

By separating sources and emotional experiences of work happiness, the study supports calls for inductive and constructivist approaches in happiness-at-work (HAW) research (

Singh & Aggarwal, 2018). This distinction aligns with emotion theory suggesting that emotional states are responses to environmental stimuli and social interactions (

Goodwin et al., 2001;

Gordon, 1990). Specifically, it corroborates

Fredrickson et al.’s (

2008) conceptualization of emotions as multi-component response tendencies shaped by interactions with one’s social and physical environment. The findings also reinforce theories highlighting that emotions emerge from subjective appraisals of experience, including within the workplace (

Frijda, 2016;

Niedenthal, 2008).

The contribution also extends the discourse within positive psychology. Rather than viewing happiness solely as a stable trait or outcome, the findings support the understanding of happiness as an emotional experience that is episodic, context-dependent, and socially constructed (

Fredrickson, 2001). This stands in contrast to the psychotherapeutic perspective that views happiness primarily as an adaptive behavioral reaction (

Perrotta et al., 2023). Importantly, the study confirms that positive emotional experiences such as “getting in a good mood,” “feeling inner peace,” and “looking forward to work” are associated with environmental and relational conditions at work, thereby reinforcing the importance of contextual and social factors in generating emotional well-being (

Shuman & Scherer, 2014;

Alexander et al., 2021).

Furthermore, the results echo

Goldman’s (

2017) proposition that happiness can be seen either as the predominance of positive emotions or as a reflective evaluation of one’s life circumstances. The emotional indicators identified in this study reflect both experiential and evaluative dimensions of happiness as proposed by

Kahneman and Riis (

2005). This dual framing adds conceptual depth to the study of work happiness by bridging momentary emotional experiences with longer-term assessments of one’s work life. Finally, the study contributes to the literature on basic psychological needs by reaffirming autonomy as a significant predictor of work-related emotional well-being. In line with self-determination theory (

Devine et al., 2008), the findings emphasize that the opportunity to influence one’s work and make meaningful decisions not only fulfills a core human need but also contributes directly to affective experiences of happiness in the workplace. This strengthens the theoretical linkage between autonomy and eudaimonic well-being in organizational contexts.

While the final model in this study integrates both individualistic (e.g., autonomy, self-development) and collectivistic (e.g., togetherness, recognition) sources of work happiness, this duality is not merely additive but points to a deeper dialectical structure of work happiness. As

Eytan (

2024) argues in his critique of positive psychology’s second wave, true psychological flourishing often arises from the tension and integration between opposing forces—autonomy versus belonging, challenge versus safety, or individual agency versus communal harmony. Similarly,

Pavlova (

2022) highlights that many high-performance work systems implicitly balance such tensions, and employees’ lived experiences often reflect a dynamic negotiation between personal growth and shared meaning. The current study’s findings reflect such dialectics in the way participants describe both solitary satisfaction from mastering tasks and joy derived from humorous, supportive team relations. This dual orientation aligns with the dialectical model of happiness proposed by

Limbasiya (

2015), where happiness is not bound to one realm (e.g., material or relational) but emerges through an interplay between different levels of experience—material, psychological, spiritual—and between self and others. Hence, the coexistence of “I” and “we” themes in the data is not a theoretical inconsistency but a hallmark of the complex, multilayered nature of work happiness.

This “I–We” dialectic has direct implications for leadership, organizational design, and cultural adaptation. Participatory and co-creative work environments, such as those described by

Bjerke (

2020), actively balance personal agency and collective wellbeing through participatory leadership and value-based cultural practices. Similarly,

Ind and Bjerke (

2007) emphasize that participatory organizational models enhance both internal engagement and external brand equity, showing how individual and collective processes reinforce one another in practice. These dynamics contrast with more hierarchical or task-centric organizations, where individualism or conformity may dominate.

Klein et al. (

2024) demonstrate that emotion regulation strategies differ across cultures along individualism–collectivism dimensions, suggesting that the balance between autonomy and togetherness is culturally contingent.

Tadesse Bogale and Debela’s (

2024) review further shows that organizational culture is neither static nor universal but shapes—and is shaped by—the relational dynamics within. Therefore, the “I–We” duality should not be interpreted as a contradiction but as a flexible orientation shaped by context, leadership, and shared meaning-making. Recognizing this dialectic allows organizations to foster work happiness in ways that are culturally sensitive, relationally rich, and structurally inclusive.

In sum, this study advances the theoretical and empirical understanding of work happiness by (1) proposing a dual-structure model of sources and emotional experiences, (2) integrating perspectives from positive psychology, emotion theory, and self-determination theory, and (3) highlighting the dialectical interplay between individual agency and collective belonging. This “I–We” orientation not only reflects the empirical structure of work happiness but also aligns with broader frameworks in participatory leadership (

Bjerke, 2020), organizational co-creation (

Ind & Bjerke, 2007), and cross-cultural psychology (

Klein et al., 2024). As organizational culture is context-sensitive and relationally shaped (

Tadesse Bogale & Debela, 2024), the study’s findings suggest that fostering work happiness requires leadership and design approaches that accommodate both autonomy and togetherness. This dual focus opens new avenues for intervention, organizational design, and culturally attuned strategies to support emotional well-being at work.

8. Practical Implications

This study offers actionable insights for leaders, HR professionals, and organizational consultants seeking to enhance employee well-being through emotionally grounded strategies. By identifying six empirically distinct sources of work happiness—autonomy, self-development, meaning at work, recognition, harmonious employee relations, and togetherness towards goals—and linking these to five specific emotional experiences—feeling happy, being in a good mood, looking forward to work, experiencing inner peace, and feeling free from stress—the study presents a dual-structured model that is both theoretically robust and practically applicable. Given the egalitarian norms and high autonomy in Norwegian work culture, the recommended interventions must be adapted to different organizational and cultural contexts.

Among the strongest predictors of positive emotional experiences were togetherness, recognition, and self-development. Recognition was frequently associated with pride, gratitude, and increased self-worth. To translate these findings into practice, organizations should move beyond generic praise and implement recognition systems that are timely, personalized, and linked to meaningful contributions. This can be achieved through digital platforms that support both leader and peer acknowledgment, storytelling practices in team meetings where colleagues highlight each other’s impact, and structured recognition rituals that emotionally resonate with employees.

- 2.

Real-time emotional tracking for leadership responsiveness

The five emotional states identified in this study are not general indicators of well-being but real-time diagnostic signals that reflect employees’ lived experiences. Organizations could develop mood-tracking tools or pulse survey instruments that assess fluctuations in statements like “I look forward to going to work” or “I feel free from stress.” Such tools would allow leaders and HR teams to detect emotional trends and take proactive steps—for instance, redistributing workload, providing individual support, or reinforcing psychological safety. Tracking emotional states longitudinally can also enhance organizational agility and responsiveness.

- 3.

Designing for autonomy and meaning to foster inner peace and engagement

To increase emotional experiences such as inner peace, motivation, and job satisfaction, organizations should embed autonomy and meaning into the design of roles and responsibilities. This may include facilitating job crafting opportunities where employees adapt their tasks to better align with personal strengths and values or initiating regular conversations between managers and employees to explore how individual contributions relate to the organization’s broader mission. Leadership styles that emphasize support, purpose alignment, and trust will further strengthen the emotional effects of perceived autonomy and meaningful work.

- 4.

Strengthening team belonging and relational happiness through structured practices

The relational dimensions of work happiness—togetherness and harmonious employee relations—were closely tied to emotional outcomes such as happiness and good mood. To support these social drivers, organizations can develop shared team rituals that build cohesion, such as regular reflective practices or celebrations of milestones. Cross-functional collaboration projects may also foster a deeper sense of interpersonal understanding and alignment. In addition, peer coaching or buddy systems can help embed continuous support and feedback into everyday working life, reinforcing relational well-being and a sense of belonging.

- 5.

Applying the “I–We” duality to organizational and cultural adaptation

Finally, the dual structure of “I” (individualistic drivers like autonomy and self-development) and “We” (collectivistic drivers like togetherness and recognition) has significant implications for intervention design. Participatory organizational environments, such as those common in Nordic countries, are likely to support flexible, co-creative approaches that balance individual agency with collective meaning-making. In contrast, hierarchical or task-centric cultures may require more formalized relational structures and carefully managed recognition systems. The use of cultural diagnostics can help organizations assess which dimension—“I” or “We”—requires emphasis, enabling interventions that are culturally sensitive and contextually responsive. Hybrid solutions that combine personal leadership development with socially embedded practices are likely to be most effective in fostering durable work happiness.

In sum, by conceptualizing work happiness as a function of distinct structural sources and subjective emotional outcomes, this study provides a highly operational and empirically grounded framework for improving workplace well-being. Rather than defaulting to generic wellness programs, organizations can target specific underdeveloped sources—such as meaning, recognition, or autonomy—to cultivate measurable and emotionally meaningful improvements. Crucially, these findings reaffirm that work happiness is not solely an individual experience, but a relational and organizational achievement.

9. Limitations and Future Directions

This study offers a novel conceptual and empirical contribution to the understanding of work happiness by differentiating between its sources and emotional outcomes. Nevertheless, several limitations should be acknowledged, and they inform the directions for future research. First, the study was conducted within a specific national and cultural context—Norwegian employees from public and private service sectors—raising questions about the generalizability of the findings. Norway’s relatively egalitarian work culture, strong welfare infrastructure, and high degree of employee autonomy may shape unique understandings and expressions of work happiness. Thus, while the findings are robust within this setting, caution should be exercised in extending them to other cultural contexts. Comparative studies across countries with differing cultural norms, work structures, and socio-economic conditions would be valuable in exploring the universality and cultural specificity of the identified sources and emotional experiences. For instance,

Alexander et al. (

2021) categorize 62 positive emotion words into eight clusters, including terms specifically labeled as “happy” (e.g., buoyant, merry, glow, glad). Future cross-cultural research could examine the linguistic and semantic variations in how employees describe work happiness and whether these variations align with distinct cultural emotion scripts.

Second, the qualitative sample was drawn from a convenience group of union representatives enrolled in a professional course on work happiness. Although the group included a range of sectors and professions, the participants’ dual identities—as employee advocates and course participants—may have introduced specific framing biases. Their union roles could make them more attuned to values such as justice, autonomy, and recognition, while the course content may have primed responses toward self-leadership and emotional well-being. These factors may have shaped both the salience of certain constructs and the affective framing of their narratives. The subsequent quantitative phase, which included a broader cross-section of employees, helps mitigate but not eliminate these concerns.

Third, the method of collecting and revising qualitative data through class-based discussions may have introduced conformity effects and social desirability bias. Participants shared, discussed, and edited their narratives in a classroom setting, potentially aligning their responses with group norms or perceived course expectations. Although this method aimed to enhance depth and reflection, future studies should consider alternative designs that reduce peer influence, such as anonymous submissions or blinded coding of responses. Comparative analyses between individually generated and group-refined data could also help assess the robustness and variability of the constructs under different conditions.

Fourth, although the study employed rigorous exploratory methods, it did not include confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) or other psychometric tests (e.g., structural equation modeling, test–retest reliability) typically required to establish the full validity of new scales. While the exploratory factor analysis (EFA) provided initial evidence of construct clarity and reliability, future research should conduct CFA in independent samples to assess the factor structure’s stability and convergent, discriminant, and nomological validity.

Fifth, the cross-sectional design limits the ability to make causal inferences. Although the regression analysis revealed significant associations between sources of work happiness and emotional outcomes, causal claims should be avoided. Longitudinal studies or experimental designs could better capture the dynamic interplay between workplace experiences and emotional states over time. For example, experience sampling or diary studies could track how daily fluctuations in autonomy, recognition, or meaningful work influence emotional well-being in real-time.

Sixth, the role of social relationships in shaping work happiness warrants deeper investigation.

Holmes and McKenzie (

2019) emphasize that social ties are dynamic and culturally embedded, influencing both the experience and expression of happiness. Similarly,

Colbert et al. (

2016) demonstrate that workplace relationships serve multiple functions—task assistance, career development, emotional support, and personal growth—all of which may contribute to feelings of happiness at work. Future studies should explore these mechanisms further, possibly integrating relational and emotional mapping methods or network analysis to identify how interpersonal dynamics generate emotional experiences.

Seventh, future research could explore how cultural orientations (e.g., individualism–collectivism) moderate these dialectics and whether the balance between them shifts across sectors, professions, or leadership models.

Eight, future research could also explore how health-promoting self-leadership (

Bjerke, 2024)—including mindfulness and resilience-building practices—serves as a personal resource linking structural sources of work happiness to emotional outcomes. Mindfulness enables individuals to stay attuned to present-moment experiences, enhancing their ability to derive meaning from autonomy, recognition, and self-development (

Coo & Salanova, 2017;

Le et al., 2024). These self-regulatory capacities may act as mediators or moderators that strengthen the connection between workplace conditions and felt happiness. Integrating self-leadership theory (

Bjerke, 2024,

2025) into future models could thus offer a more dynamic understanding of how personal agency transforms external job resources into sustained emotional well-being at work.

Lastly, this study opens the door for future research linking the sources and emotional experiences to broader organizational outcomes such as engagement, productivity, innovation, and retention. As

Salas-Vallina et al. (

2020) suggest, employee happiness can significantly impact individual performance. Future models should integrate work happiness constructs with behavioral outcomes and organizational effectiveness metrics, offering a more comprehensive understanding of how emotional well-being translates into tangible value for organizations.

In sum, while this study lays the groundwork for a refined construct of work happiness, future research should build upon it through cross-cultural validation, longitudinal exploration, advanced psychometric testing, and broader integration with organizational behavior and human resource management outcomes.

10. Conclusions

This exploratory mixed-method study contributes to the evolving understanding of work happiness by moving beyond aggregated constructs such as engagement, satisfaction, and commitment. Through a two-stage research design—combining qualitative thematic analysis with quantitative exploratory factor analysis (EFA)—the study identified six empirically grounded sources of work happiness and five corresponding emotional experiences. Together, these dimensions underscore the multifaceted nature of work happiness as both structurally embedded and emotionally lived.

A key contribution lies in the articulation of a dual-structure model that distinguishes between contextual sources—autonomy, self-development, recognition, meaning at work, harmonious employee relations, and togetherness towards goals—and emotional outcomes—feeling happy, being in a good mood, looking forward to work, experiencing inner peace, and feeling free from stress. This model adds theoretical precision to the construct of work happiness and offers a practical framework for assessing and fostering well-being in the workplace.

The study also advances a dialectical understanding of workplace happiness. Rather than treating individualistic (“I”) and collectivistic (“We”) orientations as oppositional, the findings show how these dimensions interact and reinforce one another in everyday work experiences. This duality reflects a deeper psychological and organizational reality, in which autonomy and social connection are not trade-offs but co-constitutive of emotional well-being. It aligns with recent theoretical perspectives that view flourishing as a dynamic integration of personal agency, relational belonging, and contextual meaning.

From a practical perspective, the validated items and emotional markers provide organizations with a targeted and responsive toolkit. Rather than implementing generic wellness programs, leaders and HR professionals can design interventions that activate specific happiness sources and monitor their emotional impact in real time. The emotional experiences identified here—such as feeling inner peace or looking forward to work—can serve as dynamic indicators of organizational climate and employee well-being, facilitating agile and evidence-based HR strategies.

Theoretically, the study integrates insights from positive psychology, emotion theory, and self-determination theory, while responding to recent calls for more nuanced, empirically grounded approaches to work-related emotions. By distinguishing between sources and outcomes of work happiness, and by showing how they are shaped by both cultural context and organizational design, the study contributes to a more holistic and operationally meaningful conceptualization of work happiness.

In conclusion, this research offers a novel, empirically robust, and practically actionable model for understanding and enhancing work happiness. It encourages scholars and practitioners alike to adopt a person-centered, culturally aware, and emotionally intelligent approach to fostering work happiness in organizational life.