1. Introduction

Implementing loyalty programmes as part of CRM practices has proven to be a successful strategy for many hotel organisations (

Grigoryeva, 2023). The rapid growth of the hotel industry, intense global competition, and its status as one of the fastest-growing markets have increased hotel organisations’ awareness of customer relationship management (CRM) practices, such as loyalty programmes. A guest loyalty programme is used as a crucial instrument for hotels to engage with, retain guests, foster strong guest loyalty, and incentivise repeat business (

Grigoryeva, 2023).

While many studies have investigated loyalty programmes from the consumer perspective, there is a noticeable lack of research examining the employees tasked with implementing these programme practices. For example,

Gubíniová et al. (

2023) explored factors shaping Chinese consumers’ perceptions of hotel loyalty programmes, particularly the reward structures that motivate participation. However, focusing solely on customers overlooks a critical component. As employees serve as the primary link between loyalty programme design and customer experience, their perceptions, knowledge, and willingness to engage directly influence programme success. This study addresses that gap by analysing hotel employees’ intentions to implement loyalty programme practices (LPP), providing insights that complement and extend existing consumer-focused research.

In this study, data was collected from frontline employees of leading chains in the hospitality industry. The study conducted by

Moller (

2024) researched Chinese hotel employees’ motivations to execute loyalty programme practices. The results indicate that the intentions of Chinese hotel employees to adopt LPP are positively influenced by both extrinsic and intrinsic motivation. Looking beyond Chinese hotel employees’ motivational factors to implement LPP, we investigate employee’s awareness, knowledge, concerns, and behaviour related to the chains’ loyalty programmes. We posit that these are essential factors for management to understand in order to effectively train and manage their staff to implement the appropriate practices for their customers.

Ajzen and Fishbein (

1980) advise that individual behaviour is most likely shaped by assumptions as well as attitudes. Several researchers also suggest that various environmental factors like awareness, knowledge, and concerns can influence an individual’s actions (

Mostafa, 2009;

Perron et al., 2006;

Kotchen & Reiling, 2000). Such factors related to the work environment affect employees’ alignment with the company’s initiatives and impact individuals’ intentions to act. This research investigates how LP awareness, LP knowledge, and LP concerns impact Chinese hotel employees’ intentions to implement loyalty programmes. In addition, this study explores how Chinese hotel employees’ pro-loyalty programme behaviours relate to the intention of implementing loyalty programme practices. Understanding why it is important to implement practices is crucial because the participation of hospitality and service employees plays a significant role in the effectiveness of a hotel’s operations. Research on loyalty programmes (LPs) and customer relationship management (CRM) in the hospitality sector has historically prioritised the consumer perspective, examining customer satisfaction, retention, and purchase behaviour (

Bolton et al., 2000;

Melnyk & Bijmolt, 2015). This customer-focused bias is particularly evident in studies on the Chinese hospitality market, where loyalty research largely explores how reward structures, cultural preferences, or perceived value influence consumers (

Gubíniová et al., 2023). In contrast, employee-related factors—especially employees’ intentions and attitudes toward implementing LP practices—remain underexplored, despite employees being the critical link between programme implementation and customer experience (

Kandampully & Suhartanto, 2000). This neglect of employee intention in the Chinese context is surprising for two reasons. First, China’s hospitality industry has expanded rapidly in the past two decades, resulting in heterogeneous workforce training levels and inconsistent loyalty programme execution (

He et al., 2012). Second, cultural and organisational dynamics unique to China, such as power distance, collectivism, and hierarchical service structures (

S. Wang & Fränti, 2022;

Wen et al., 2023), may shape employees’ motivation and willingness to adopt corporate initiatives differently from non-Chinese employees. These dynamics directly affect the success of customer relationship management (CRM) strategies and loyalty programme delivery but have rarely been examined empirically from the employees’ point of view. By critically addressing this gap, the present study contributes to a more holistic understanding of loyalty programmes in Chinese hotels. It complements the extensive consumer-focused literature by highlighting how employees’ knowledge, awareness, and concerns influence their implementation intentions—factors that ultimately affect guest experiences and programme success. The findings presented in this research can provide useful guidance for management in creating and developing effective recruitment, training, and incentives to support the crucial nature of loyalty programmes which emphasise customer relationships.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Hospitality Industry in China

Over the past decade, China’s hotel industry has experienced consistent growth in both scale and revenue (

Statista, 2024). This growth has been primarily driven by foreign investments, as major multinational hotel groups recognised China as a prime location for investment. The Chinese hotel industry is expected to reach a value of USD 128.04 billion by 2029, showing an annual growth rate (CAGR) of 8.12% (Hospitality Industry in China Size and Share Analysis—Growth Trends and Forecasts, 2024–2029). The analysis underscores the significant growth of China’s hospitality market, which is driven by political stability, economic growth, and a growing middle class.

Shi et al. (

2016) explore the relationship between star-rated hotel expansion and inbound tourism in China (Pre-COVID-19). Their results indicate a direct relationship, underscoring the importance of quality accommodations in promoting the growth of tourists. This symbiotic relationship underscores how the growth of the hotel industry contributes to the broader economic landscape by attracting international visitors. As the hotel sector expands, it catalyses economic development, showcasing its pivotal role in shaping China’s tourism sector.

The rise in this sector has led to intense competition between hotel conglomerates, underscoring the significance for hotels to set themselves apart from competitors and build a dedicated loyal guest base. With the entry of global hotel chains into the Chinese market, new management systems and marketing strategies have also been introduced. These not only set the benchmark for service higher but also greatly contributed to the quick expansion of the hospitality industry in China (

Zhang & Huang, 2019).

Jain et al. (

2023) highlight that China leads, in terms of contributing countries towards luxury hospitality research as well as having the highest number of publications on general hospitality management. This not only reflects the rapid market development but also reflects the growing interest in this topic within Chinese academic communities.

As China’s hotel industry expands, the demand for efficient CRM systems and loyalty programmes becomes essential for hotels to sustain their competitive advantage. However, the success of such initiatives depends not only on programme design but, critically, on the employees who implement them—frontline staff serve as the key interface between hotel brands and guests, directly shaping customer perceptions, satisfaction, and long-term loyalty. Thus, understanding and improving employees’ willingness and abilities to carry out loyalty programme actions is crucial for maintaining progress in China’s evolving hotel industry.

2.2. Chinese Hotel Employees

While international hotel chains prioritise maintaining their organisation’s policies, internal management strategies, and company culture, it is essential to adapt to the local culture in order to be competitive in the local and existing market (

Xu et al., 2018). Chinese hotel employees may exhibit distinct characteristics shaped by cultural, social, and economic factors (

K. Y. Wang et al., 2021). Understanding these traits is essential for effective management. Chinese employees often value workplace harmony, loyalty, and job security (

Y. T. Wong & Wong, 2013). Hospitality management in China should, therefore, focus on fostering a supportive and harmonious work environment while offering career development opportunities (

Mayes et al., 2017), and acknowledge the importance of family (

Liang et al., 2012). Moreover, recognising the influence of Chinese cultural values, such as collectivism and interpersonal relationships, is vital for effective leadership and team dynamics (

I. K. A. Wong & Gao, 2014). Tailoring training programmes on loyalty programme practises to align with Chinese hotel employees’ unique needs and expectations can enhance overall job satisfaction (

Kanapathipillai & Azam, 2020;

Hanaysha & Tahir, 2016) and performance (

Pangestuti, 2019). Management strategies must adapt to these distinctive characteristics (

Setti et al., 2022), ensuring a positive and productive work environment for Chinese hotel employees as the industry evolves. Leadership, particularly transformational leadership, is crucial in fostering service innovation (

C. H. S. Liu & Lee, 2019). Chinese hospitality managers can adopt leadership practices that encourage team creativity and adaptability. This is particularly relevant as the sector continues to evolve and compete globally (

Joint Wisdom, 2019). Employees’ behaviour towards hotel guests, such as being courteous, offering the correct products or services, fostering relationships, and showing empathy, significantly affects customer satisfaction with the provided service (

Hennig-Thurau & Klee, 1997).

Many hotel workers in China lack prior experience in the hotel or hospitality sector (

Ferreira & Alon, 2008). Hotel job openings are often filled by inexperienced young people who often need assistance and guidance from their co-workers and managers (

Stamolampros et al., 2019). Hotels need to consider that mainland Chinese employees may have limited knowledge about global hotel brands when training them on brand attributes. Research indicates that the understanding of multinational hotel groups (MHG) by Chinese hotel employees plays a crucial role in achieving successful brand-building as well as CRM behaviour.

Türkay and Şengül (

2014) focused on determining the personnel actions that greatly impact customer satisfaction and perception. Three main employee behaviours are highlighted in their study: politeness and cheerfulness, imparting a feeling of “specialness” to customers, and possessing sufficient knowledge to answer queries.

A growing number of companies in the tourism and hospitality industry have implemented internal service principles to maintain competitive advantage (

Akroush et al., 2013;

Heskett & Sasser, 2010). Chinese travellers who do not have much tourism-related experience and who are new to international hotel services may not be familiar with hotel standards or hotel loyalty programmes (

Hung, 2013). Similarly, Chinese employees in the hotel industry may also lack familiarity with the international service standards of the hotel chain. As MHGs depend on Chinese employees to uphold the companies promise of a foreign hotel brand, it becomes crucial to develop and manage the brand internally through LPs. As a result, it may be essential for MHGs to offer thorough training and development to hotel employees, focusing not only on hospitality skills but also on familiarising them with the MHG brand and loyalty programme benefits, practices, and goals. In the absence of such training and development, employees may struggle to provide a brand experience that ultimately results in customer satisfaction and retention.

Moreover, frontline workers play a crucial role in connecting companies with their clients (

Crawford et al., 2022). Numerous researchers mention the significance of frontline workers in ensuring the achievements of an organisation. Frontline staff are essential in generating customer satisfaction as well as loyalty through their service interactions, as they are tasked with upholding the organisation’s commitments (

Grönroos, 2020;

Raie et al., 2014). Various research studies have demonstrated that customer satisfaction, their evaluation of service quality, and their choice to remain loyal to or change to a different organisation within the industry, are highly influenced by the customer-centric attitudes, behaviour, and actions of contact employees (

Jarideh, 2013).

2.3. The Drivers of Employees’ Intentions

Management understands that hotel employees require additional tools, training, and acknowledgment in order to enhance their performance and achieve excellence (

Leaman, 2018). In order to propose suggestions to hotel managers and academics, three main drivers that may influence Chinese hotel employees’ intentions to implement loyalty programme practices are being investigated. It is proposed that awareness, knowledge, and concerns can influence hotel employees’ intentions to implement the chain’s loyalty programme practices. It is assumed that once employees receive more knowledge about the chain’s loyalty programme, increased awareness and concerns about the programme intentions are developed, resulting in the employee being more likely to take the initiative to implement the respective loyalty programme practices. Below, we examine the hypothesised connections between the three factors. Deciphering how behavioural intentions are formed is one of the most promising research fields in organisational psychology and cognitive neuroscience. Empirical findings showing that intention development processes are ordered hierarchically, with awareness followed by knowledge acquisition that leads to the development of concern, culminating in behavioural intention. The distinction between cognitive and affective sources of behavioural intention has already been extensively explored by the ABC (Affective-Behavioural-Cognitive) model, which provides the framework under which such parts interact to influence decision-making and action.

When the cognitive and affective channels are combined, the resulting behaviours are the strongest, especially where the practice is technical and socially sensitive.

McChesney et al. (

2025) found that performance is maximised when cognitive and affective elements are used in parallel, which results in more powerful and durable behaviour intentions. This was further backed up by Li et al. 2023, who demonstrated that a multidimensional intervention leads to lasting behavioural changes when one intervenes by a single dimension. This combination of forces is particularly visible in the healthcare, education, and hospitality industries, as these fields require specialised knowledge of procedures and the ability to respond to problems with empathy. As an illustration, training programmes based on integrating scenario-based cognitive drills and emotional storytelling (such as customer testimonials), which have been reported to be beneficial regarding compliance and service quality among hotel employees.

2.4. Employees’ Awareness

In the context of hospitality and CRM, employee awareness refers to an individual’s understanding of the organisation’s operational environment, customer needs, and service expectations, as well as the ability to recognise how these factors influence day-to-day performance. Rather than a general state of mindfulness, awareness in hotel settings is a practical, job-related competence that enables employees to respond appropriately to customer interactions and organisational objectives (

Jones et al., 2010;

Koeber et al., 2001). Research shows that employees with higher awareness of their business environment are better equipped to make decisions and solve problems effectively, leading to improved job performance (

Latham et al., 1994). In the context of loyalty programmes, this awareness includes familiarity with programme policies, benefits, and procedures, as well as an understanding of how these elements contribute to customer satisfaction and retention.

Programme awareness allows employees to integrate loyalty programme practices seamlessly into their daily routines, ensuring consistent and informed customer engagement. On the neurocognitive level, the breakthrough study by

Bidelman et al. (

2021) demonstrated that conscious awareness causes activation of specialised temporal parietal networks that are deemed fundamental in information encoding and further learning activities. Awareness induces activation among the areas linked to higher order thinking.

Awareness also influences employees’ openness to new ideas and service innovations, which are critical in competitive hospitality markets (

Shahzad et al., 2024). When employees are aware of both the operational context and the strategic goals behind loyalty programmes, they are more likely to align their behaviour with organisational objectives and contribute to service excellence (

Martínez-Córcoles & Vogus, 2020;

Gadenne et al., 2009).

Given the strategic importance of this topic, this study investigates whether employees’ awareness of loyalty programmes positively influences their intention to implement programme practices—forming the basis of the first hypothesis.

H1. Loyalty programme awareness positively leads to intentions of implementing loyalty programme practices in hotel organisations.

2.5. Employees’ Knowledge

The transition from awareness to knowledge development has been widely documented, particularly within organisational contexts.

Barari et al. (

2022), in a comprehensive meta-analysis of sharing economy platforms across diverse service industries, examined this relationship in depth. Their findings revealed that users who first developed an awareness of platform existence demonstrated a 42 percent higher retention of operational knowledge compared to control samples. This effect was most pronounced in relation to complex behavioural protocols, suggesting that awareness functions not merely as initial exposure but as a cognitive scaffold through which subsequent information can be organised and integrated.

Employees who possess a deep understanding of how their organisation operates and the competitive market in which it exists, are more likely to make successful decisions. Understanding how one’s actions affect the reputation of the company is a crucial requirement for behaving appropriately that influences the overall performance of the organisation (

Yazdani & Murad, 2015). To achieve business success, knowledge has emerged as a crucial strategic element. Knowledge management processes are increasingly becoming an important aspect of organisational operations (

Bolisani & Bratianu, 2018). These processes involve a dynamic and ongoing series of activities with the goal of recognising and also utilising the collective knowledge within the organisation in order to enhance its competitiveness (

Jiang et al., 2023;

Vihari et al., 2019).

In the hotel industry, knowledge entails possessing the required information to deliver exceptional customer service while adhering to designated operational protocols (

Yang & Wan, 2004).

Nguyen and Malik (

2022) examine the impact of knowledge sharing on employees’ service quality when considering the moderating role of artificial intelligence (AI). In this era of technological advancement, adopting knowledge-sharing practices are crucial for hotels to enhance service quality, ensuring employees stay abreast of evolving customer expectations.

Latif (

2021) investigates the relationship between Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and customer loyalty in the hotel sector. While not directly addressing employee knowledge, CSR initiatives can indirectly impact the work environment, influencing employee morale and potentially enhancing the quality of customer interactions. A research study by

K. Y. Wang et al. (

2021) focuses on perceived satisfaction and revisiting intentions during restricted service scenarios. The study offers valuable insights into customer expectations during challenging situations, highlighting the importance of hotel employees being responsive to evolving customer needs and adjusting their service delivery accordingly.

Recent research highlights the distinct yet complementary roles of cognitive and affective variables across diverse contexts, offering valuable insights for organisational behaviour and training interventions. Cognitive routines—particularly procedural knowledge and system comprehension—tend to dominate in structured settings where adherence to rules is essential.

McChesney et al. (

2025) demonstrated that cognitive engagement accounts for a substantial proportion of variance in task fulfilment, particularly in environments demanding precision in following established protocols. Similarly,

Li et al. (

2023) found that cognitive variables mediate the relationship between training and performance outcomes in technical or rule-driven roles. These findings suggest that behaviours requiring accuracy and compliance are primarily cognitively driven, with affective factors playing a secondary role. By contrast, affective drivers are more influential in contexts that demand emotional involvement, social interaction, or discretionary effort.

Lin et al. (

2024) showed that affective responses—such as emotional reactions to communication styles—independently predict behavioural outcomes beyond the influence of cognitive knowledge. This aligns with the findings of

Chi et al. (

2020) on youth data literacy, where affective interest in social media content translated into privacy-related behaviours, regardless of technical knowledge.

Continuous learning and support systems are considered important factors when equipping hotel employees with skills and knowledge to deliver exceptional service and enhance customer experience (

Luo et al., 2021). Therefore, recent research emphasises the critical role of Chinese hotel employees’ knowledge and awareness of delivering professional customer service to ensure customer retention. Hotels must invest in employee development, address turnover challenges, and adapt strategies to meet evolving customer expectations, ultimately fostering long-term customer loyalty in an industry that is dynamic and competitive. Furthermore, it is important to highlight that individuals typically avoid situations in which they lack sufficient knowledge to navigate their behaviour as well as situations that carry a high risk of uncertainty (

Kaplan, 1992).

To extend the research related to employee knowledge regarding loyalty programmes, the following hypothesis is proposed.

H2. Significant loyalty programme knowledge positively leads to intentions of implementing programme practices in hotel organisations.

2.6. Employees’ Concerns About Customer Loyalty Programmes

In this study, “concerns” refers to employees’ sense of responsibility and commitment toward the effective functioning of loyalty programmes, which is grounded in their identification with organisational goals and understanding of how programme success contributes to the organisation’s performance. This construct combines elements of organisational concerns—a willingness or devotion to support the organisation because its success is tied to one’s own well-being (

Halbesleben et al., 2010;

Grant, 2008)—and the behavioural beliefs component of the Theory of Planned Behaviour (

Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980), where positive or negative expectations about a programme influence employees’ intentions to act.

Hotel loyalty programmes play a critical role in developing guest loyalty. Still, their implementation and effects have raised several concerns from different stakeholders, such as hotel employees, management, and guests.

Koo et al. (

2020) analyse how loyalty programmes contribute to increased hotel guest loyalty by maximising switching barriers. A loyalty programme not only encourages customers to return to the hotel, but also gains their loyalty or may even entice them to try different sub-brands within the larger umbrella brand (

Bhagwat Juhi, 2020). From the standpoint of hotel management, it is essential to design loyalty programmes that effectively attract and retain guests. The research defines switching barriers, including the available point redemption options and programme flexibility, as influential factors in guest loyalty. Moreover,

Lee et al. (

2021) focus on the emotional aspects of hotel loyalty programmes and how deviations may lead from “love to hate or forgiveness”. The functional and psychological aspects of loyalty programmes also attract the attention of hotel management. This research emphasises the accountability of managing guests’ emotional reactions to programme deviations and their resultant effect on loyalty. Hotel workers must understand such emotional concerns to deal with a guest issue effectively.

According to

Lee et al. (

2021), individuals who are part of a loyalty programme tend to overlook or pardon a negative encounter or dissatisfaction with a service. This illustrates the advantageous and indirect impact of loyalty programmes on businesses and in ensuring a positive employee–customer engagement. Nonetheless,

Bolton et al. (

2000) argue that these loyalty programme members are still highly sensitive to significant service failures and are more meticulous in terms of providing feedback which may result in employees being fired. This could potentially be a threat to employees dealing with loyalty programme members. On the other hand,

J. Liu and Jo (

2020) highlight that loyal customers can show sensitive thoughts and affection, which, if managed in the right way, may lead to positive outcome.

The cognitive–affective transition from knowledge to concern represents a critical stage in the formation of intention. This relationship is strongly substantiated by the longitudinal study on workplace policy adoption conducted by

Elinor and Lisa (

2022). Their findings demonstrate that policy knowledge alone was insufficient to generate implementation intentions. Rather, employees were motivated to adopt new policies only when they could connect their knowledge of policy provisions to outcomes of personal relevance. This affective mediation effect was particularly pronounced in the context of policies requiring long-term behavioural change, as opposed to those involving one-off behavioural actions.

According to

Ajzen and Fishbein (

1980), attitudes do not have a direct impact on behaviour. Instead, they influence the intentions behind behaviour, which ultimately lead to the actual actions. Investigating further into employees’ concerns, it is vital to assess the organisational-concern motive that, according to

Halbesleben et al. (

2010), consists of two elements. Firstly, it arises from the willingness to support that ultimately assists the organisation due to a personal identification (

Jang et al., 2024;

Halbesleben et al., 2010). Secondly, it stems from the understanding that the well-being of the organisation directly impacts the well-being of the individual. Employees who possess willingness to help others, or genuinely care about the company, are willing to take risks because they prioritise the goals of their colleagues and the organisation over their own goals (

Grant, 2008). Studies show that there is a direct relationship between how much management of a company is perceived to care about its employees and how committed those employees are to the organisation (

Halbesleben et al., 2010). Employees who strongly identify with their organisation’s success are more likely to engage in behaviours that protect and promote loyalty programme objectives, even when these require extra effort or resource investment (

Mo & Shi, 2017;

Jang et al., 2024). Such commitment-driven concern differs from general anxiety or apprehension—it reflects a proactive stance toward supporting initiatives that align with both organisational and customer goals. Therefore, our proposition is that having concerns about the loyalty programme practices will make employees act in alignment with the loyalty programme and, ultimately, the hotel organisation. With this in mind, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H3. Programme concerns positively predict intentions of implementing loyalty programme practises in hotel organisations.

2.7. Intentions Leading to Behaviour to Implement Loyalty Programme Practices

The Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) (

Ajzen, 1991) posits that behavioural intention is the most immediate predictor of actual behaviour, shaped by attitudes toward the behaviour, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control. In hospitality and service contexts, research has confirmed that, while intentions are often aligned with behaviour, a gap can exist due to situational constraints, competing demands, or lack of resources (

Verma & Chandra, 2018;

C. Wong & Law, 2002). This “intention–behaviour gap” has been documented in areas such as service quality delivery (

Arasli et al., 2014), sustainable hospitality practices (

Han & Yoon, 2015), and customer service performance (

Chiang & Jang, 2008b,

2008a), suggesting that even motivated employees may not always translate intentions into consistent actions.

From a cognitive–behavioural perspective, intention functions as a mediating mechanism between antecedents (e.g., loyalty programme knowledge, awareness, and concerns) and behaviour. Knowledge and awareness influence employees’ beliefs about the expected outcomes of implementing loyalty programme practices, shaping a positive intention to act. This intention then directs attention, effort, and persistence toward the desired behaviour (

Ajzen, 1991;

Fishbein & Ajzen, 2011). Without the formation of a strong intention, even well-informed employees may fail to prioritise programme-related tasks in their daily work. Empirical studies in hospitality management highlight this mediating role. For instance,

Chen and Peng (

2014) found that hotel employees’ service attitudes influenced performance primarily through their behavioural intentions. These findings align with research in customer relationship management, where employees’ intentions to adopt specific practices were shown to be a key driver of actual behaviour (

Elidemir et al., 2020;

June & Mahmood, 2011).

Given that organisational effectiveness in hospitality is strongly dependent on the behaviour and performance of frontline staff (

Zin et al., 2012;

June & Mahmood, 2011), understanding the intention–behaviour link in the context of loyalty programme implementation is essential. This study, therefore, examines whether hotel employees’ intentions to implement loyalty programme practices predicts their actual behaviour, and whether intention mediates the relationship between programme-related drivers and behaviour.

After considering the above discussion, we hypothesise that hotel employees’ intention to implement LP practices predicts their behaviour towards loyalty programmes.

H4. Intentions to implement loyalty programme practices positively lead to loyalty programme behaviour.

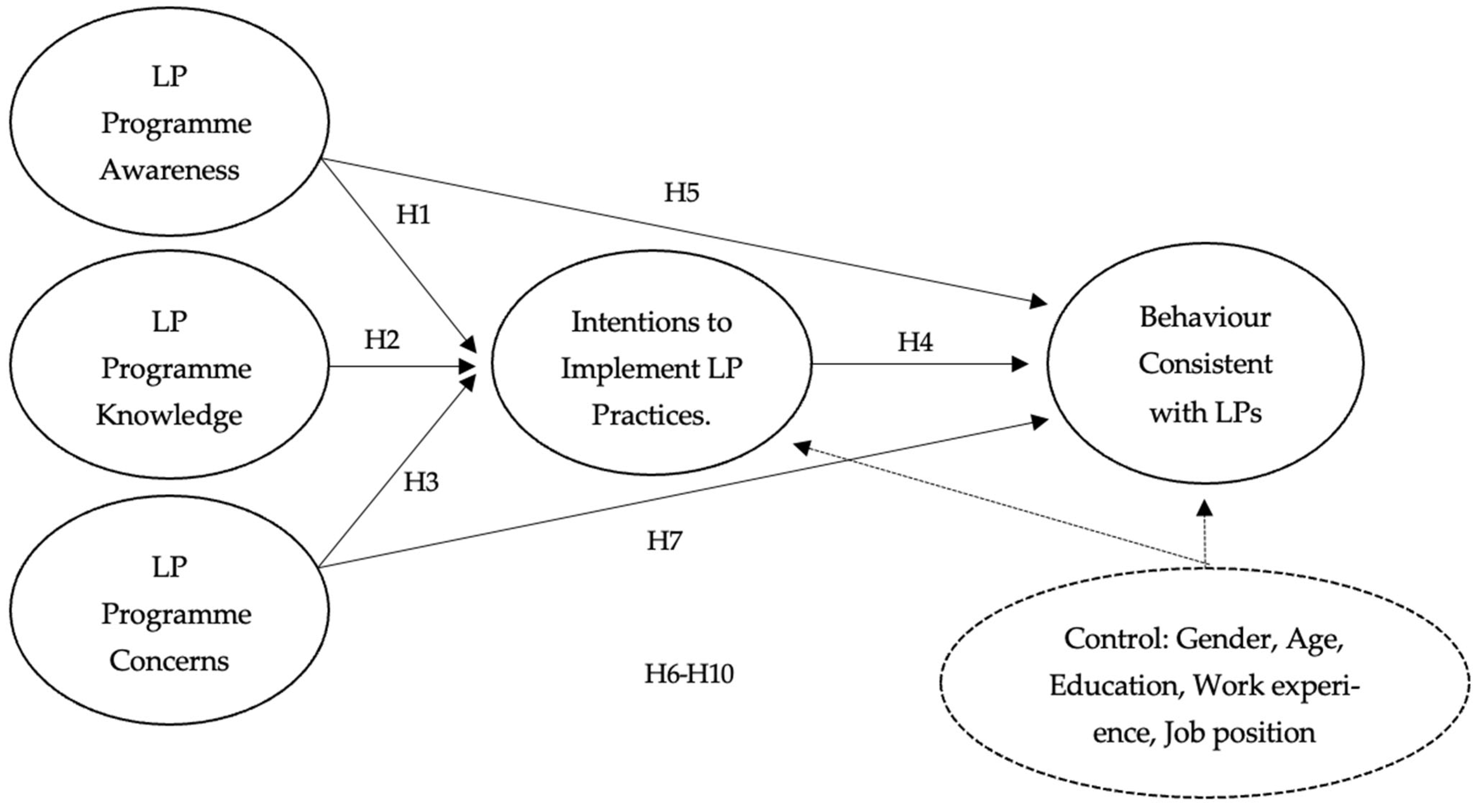

It is believed that a gradual increase in awareness of loyalty programmes, followed by gaining knowledge about the programme and showing concern for it, can predict the intention to implement loyalty programmes in a positive manner, and, in turn, predict pro-loyalty programme behaviour. The four hypotheses highlighted above (H1–H4) express a mediation effect, such that the three drivers—awareness and knowledge as well as concerns—each predict intention to implement loyalty programme practices in the hospitality industry, and, ultimately, positively influence behaviour consistent with loyalty programmes. To be more specific, intentions to implement loyalty programme practices facilitate Chinese hotel employees’ programme awareness, knowledge, and concerns. Therefore, it is expected to improve how employees engage with loyalty programmes.

For this reason, intention to implement programme practices should serve as a mediator of the three drivers’ relationship to loyalty programme behaviour. The model suggested to illustrate the hypotheses can be seen in

Figure 1.

H5. Loyalty programme awareness positively leads to hotel employees’ engagement in LP behaviour.

H6. Loyalty programme knowledge positively leads to hotel employees’ engagement in LP behaviour.

H7. Programme concerns positively leads to hotel employees’ engagement in LP behaviour.

H8. Loyalty intentions mediate the positive relationship between awareness and behaviour.

H9. Loyalty intentions mediate the positive relationship between knowledge and behaviour.

H10. Loyalty intentions mediate the positive relationship between concerns and behaviour.

3. Methodology

3.1. Questionnaire Development

A self-administered online questionnaire using a 5-point Likert scale based on the prior literature (

Carlini & Grace, 2021;

Ahmad et al., 2019;

King & So, 2015;

Battistelli et al., 2014) was adapted to the specific focus of the Chinese hotel industry. The first section measured employees’ awareness of loyalty programmes (6 items), followed by knowledge of loyalty programmes (5 items) and concerns regarding such programmes (14 items). Subsequent sections assessed programme-related behaviour (3 items) and intentions to implement loyalty programme practices (2 items). The final section gathered demographic information about the participants such as age, position, educational level, and years of work experience.

To measure hotel employees’ subjective programme awareness and knowledge of loyalty programmes, statements developed by

Carlini and Grace (

2021) and modified for this study were utilised (e.g.,

I can recognise my organisation’s loyalty programme practices; Among my colleagues, I am an “expert in knowing and understanding about loyalty programme requirements and criteria”). Statements focused on hotel employees’ programme concerns were modified to this research topic from

Battistelli et al.’s (

2014) work (e.g.,

I am concerned that the hotel will not get long-term benefits from implementing a loyalty programme). Other statements exploring hotel employees’ behaviour towards loyalty programmes were modified from

King and So’s (

2015) study (e.g.,

I demonstrate behaviours that are consistent with loyalty programme promise of the hotel that I work for). Lastly, questions focused on the employees’ intentions to implement programme practices were modified from

Ahmad et al.’s (

2019) study (e.g.,

I intend to implement loyalty programme practices in my hotel). To verify the correctness of the Chinese translation, reverse translation from Chinese to English was conducted (

Mount & Back, 1999).

3.2. Data Collection

General managers, human resource directors, and upper management of either loyalty programmes or hotel organisations in the luxury category were contacted to find appropriate participants: Chinese employees in the hospitality industry in China. According to a study from

Traveldaily (

2022), 72.9% of Chinese consumers frequently choose to book properties ranging from upscale to luxury with their family or friends as a result of their cultural emphasis on collectivism. Overall, 100 hotels supported this research by forwarding the survey link to their Chinese frontline employees working in Sales and Marketing, Reservations, Food and Beverage (F&B), Guest Relations, or Customer Service. Six categories of employees participated including those in top managerial positions (e.g., senior management level), employees in middle management (e.g., supervisor and department assistant manager), and, finally, entry-level employees. The participants volunteered to participate in the study with no monetary incentive. Frontline employees are crucial in the hotel sector and are frequently chosen as typical subjects in research when focusing on frontline staff (e.g.,

Pinto et al., 2020;

Patah et al., 2009). In addition,

Engen and Magnusson’s (

2015) study indicates that frontline employees working in hotel organisations, such as the front desk clerks who deal with guest check-ins and check-outs, have a significant ability to craft new ideas and are perceived as innovative employees overall.

3.3. Demographic Profile of Respondents

In total, 1015 questionnaires were received with 893 usable surveys (89.3% validity rate). Among the 893 employees, 450 (50.40%) were male. The majority of employees (61%) had attained less than a postgraduate education. Employees with less than three years of work experience represented 34.40%, followed by employees with work experience between six and ten years (24%).

3.4. Analytical Tools

We applied SPSS to evaluate the quality of measurement by calculating Cronbach’s α. Then, we applied Harman’s single-factor test to rule out common method biases. Finally, the collected data were analysed using path analysis with Mplus 7.4 to test the hypotheses with a bootstrap approach to estimate the confidence interval of mediation effect.

4. Results

4.1. Preliminary Analysis

Before testing the hypotheses, we conducted Harman’s single-factor test. The results showed that one factor explained 34.39% of the variance, well below the recommended threshold of 50%. These results indicate no common method biases.

Table 1 presents the descriptive analysis results, including the means, standard deviations, and, lastly, correlation of all variables.

Certain relationships between the variables examined showed statistically significant results as anticipated. Loyalty programme awareness and loyalty programme knowledge were positively related to employees’ intention to implement loyalty programme practices, whereas intention to implement loyalty programme practices was positively related to loyalty programme behaviour.

4.2. Hypothesis Test

We tested hypotheses with Mplus 7.4. Regression results are presented in

Table 2 and proposed model results in

Figure 2. Firstly, results (

b = 0.16,

SE = 0.04,

p < 0.001) show that LP Awareness positively predicts LP Intentions in hotel organisations, supporting H1. Secondly, results (

b = 0.75,

SE = 0.03,

p < 0.001) indicate LP Knowledge significantly predicts LP Intentions, supporting H2.

H3 was not supported as LP Concerns did not predict LP Intentions with results of (b = −0.01, SE = 0.03, p > 0.05). H4, and, equally, H5 suggests that LP Awareness (H4) and LP Knowledge (H5) positively relate to LP Behaviour. The results of H4 (b = 0.13, SE = 0.03, p < 0.001), and H5 (b = 0.60, SE = 0.03, p < 0.001), support the hypotheses. Furthermore, LP Knowledge significantly positively predicts LP Behaviour in hotel organisations, supporting H6 (b = 0.60, SE = 0.03, p < 0.001). H7 predicts that LP Concerns positively leads to LP Behaviour in hotel organisations. However, results indicate that LP Concerns negatively predict LP Behaviour in hotel organisations (b = −0.06, SE = 0.02, p < 0.001), not supporting H7. The results show that LP Intentions significantly mediate the positive relationship between LP Awareness and LP Behaviour (Estimate = 0.04, SE = 0.01, 95%, CI = [0.02, 0.07], did not include (0), and, therefore, supports H8. LP Knowledge is positively associated with LP Behaviour (Estimate = 0.20, SE = 0.02, 95%, CI = [0.16, 0.24], did not include (0), and, therefore, supports H9. The results show that LP Intentions do not mediate the positive relationship between LP Concerns and LP Behaviour (Estimate = −0.00, SE = 0.01, 95%, CI = [−0.02, 0.01], included (0), and, therefore, H10 is not supported.

5. Discussion

Because the Chinese hotel industry has received limited scholarly attention regarding the factors that influence employees’ intentions to engage in LP implementation, this study examined and assessed the impact of LP Awareness, LP Knowledge, LP Concerns, LP Intentions, and LP Behaviour. The results confirm that employees with higher LP awareness demonstrated significantly stronger intentions to implement related practices within the hotel organisation. The results of H1 are in line with the literature which argued that an individual’s level of awareness impacts an individual’s outlook, hence the willingness to embrace new ideas (

Shahzad et al., 2024), which, in other words, the ideas and practices that are involved when implementing loyalty programme practices. Similarly, employees who possessed higher LP Knowledge demonstrated significantly higher intentions to implement programme practices in hotel organisations. The results of H2 align with prior research showing that employees’ understanding of their business environment enhances job performance (

Latham et al., 1994); in this study, such understanding specifically improved performance in implementing loyalty programme practices. According to H2, Chinese hotel employees’ LP Knowledge positively leads to intentions of implementing loyalty programme practices in hotel organisations. H3 predicted that LP Concerns positively influence the intentions of implementing loyalty programme practises in hotel organisations. While organisational concern refers to employees’ willingness to use any means or resources to achieve organisational goals, this study found that such concern does not necessarily predict intentions to implement loyalty programme practices. A possible interpretation is that these employees may perceive loyalty programme tasks as procedural rather than at their discretion, meaning they will follow the guidelines regardless of concerns. In other words, LP implementation might be seen as a formal job requirement rather than an activity motivated by emotional attachment to the organisation. Both H4 and H5 predicted positive relationships between LP Awareness (H4), LP Knowledge (H5), and LP Behaviour. The results for H4 and H5 reinforce the importance of behavioural intention as a driver of actual behaviour, and is consistent with research emphasising the role of employees’ capabilities and behaviours in organisational performance (

Elidemir et al., 2020;

June & Mahmood, 2011). LP Awareness and LP Knowledge were both positively related to LP Behaviour, supporting the argument that cognitive readiness—knowing what the programme is and how it works—is a critical antecedent to employee compliance, overall job performance, and engagement (

Yazdani & Murad, 2015). Employees with greater LP Knowledge demonstrated significantly higher LP Behaviour in hotel organisations. The results of H6 are in accordance with the previous study where the researcher concluded that individuals typically avoid situations where there is lack of sufficient knowledge to navigate their behaviour as well as situations that carry a higher degree of risk (

Kaplan, 1992). Reviewing H1, H2, H4, H5, and H6, the research confirms the positive relationship between LP Awareness, LP Knowledge, LP Intentions, and LP Behaviour. Therefore, offering employees training to increase their awareness and knowledge should be considered.

H7 predicted that LP Concerns positively leads to LP Behaviour in hotel organisations. However, this hypothesis was not supported. When looking at the statistics, LP Concerns of employees are overall fairly moderate. This means having LP Concerns does not affect the LP Behaviour on a large scale. With respect to the mediating effects, H8 and H9 were confirmed, indicating that LP Intentions serve as a bridge between cognitive factors (awareness and knowledge) and actual behaviour. This finding underscores the psychological pathway through which training and communication efforts translate into action: first by shaping employee intentions, then by influencing observable behaviour. H8 predicted that LP Intentions mediate the positive relationship between LP Knowledge and LP Behaviour, whereas H9 predicted that LP Intentions would mediate the positive relationship between LP Awareness and LP Behaviour consistently. Results indicate that employees’ LP Intentions mediate the effects of employees’ LP Awareness (H8) and employees’ Knowledge (H9) on the LP Behaviour. These findings suggest that LP Intentions, led by LP Awareness and LP Knowledge, are a significant factor in anticipating employees’ LP Behaviour. These findings indicate that hotel employees’ performance on implementing LPP is related to management factors, as highlighted in the literature. One possible solution to enhance a hotel’s performance and reputation is to recruit individuals who possess a strong understanding of loyalty programmes, and who are aware of and exhibit behaviour that is consistent with LPP. In addition, offering training to hotel staff can also contribute to improving LPP and overall performance. Lastly, H10 was not supported which means the LP Intentions do not mediate the relationship between LP Concerns and LP Behaviour. Overall, based on the results, concerns of hotel employees regarding the loyalty programme are moderate and, therefore, do not affect intentions to implement loyalty programmes. Employees are not concerned about the loyalty programmes; therefore, implementing practices according to the guidelines will still take place. The lack of a significant relationship suggests that employees’ affective or moral concerns about the programme have little bearing on either their intentions or actual behaviour. A plausible explanation is that loyalty programme practices in hotels are highly structured and standardised; thus, implementation is largely a compliance activity, less influenced by employees’ emotional investment. This challenges the assumption that organisational concern necessarily drives voluntary engagement with LPP and instead suggests that procedural clarity and job expectations may override affective factors. The results also revealed that organisational concerns—representing employees’ affective attachment to the hotel and its goals—did not predict intentions or behaviours related to loyalty programmes. This is a noteworthy contribution because it challenges the assumption that emotional engagement is always a driver of programme compliance. In the context of hotels, loyalty programme implementation appears to function as a procedural requirement rather than a discretionary behaviour shaped by affective commitment. Employees are likely to follow LP guidelines regardless of personal concerns, suggesting that emotional attachment to the organisation is less relevant for initiatives that are clearly standardised and operationally mandated.

6. Theoretical and Practical Implications

The primary contribution of this study is to address the paucity of research on the intentions of Chinese hotel employees to implement loyalty programme practices by examining the relationship between the three previously identified drivers: LP Awareness, LP Knowledge, and LP Concerns. Another objective of this research was to create and evaluate a model designed to investigate the correlation among those drivers. In addition, the intention to put programme practices into action, serving as a link between the three drivers and employees’ behaviour consistent with the programme, has a direct impact on the shared implications. The results provide a theoretical contribution to the literature on customer relationship marketing in the Chinese hotel industry. Past research on loyalty programmes has mostly looked at Western cultures, but this study investigates the intentions of luxury hotel employees in a Chinese setting. Due to the cultural disparities between other countries and China, this research presents fresh perspectives on the work environment of Chinese hotel employees. Until now, there has been limited research on the antecedents of employees’ intentions of implementing loyalty programme practices in China, so this study’s primary contribution is to fill this research gap by testing and assessing the relationship between the three drivers highlighted previously. The research findings carry significant implications for management. The findings of this research could be utilised to create successful strategies to effectively train Chinese hotel employees to implement loyalty programme practices in their daily work routine. Management needs to focus on shaping Chinese hotel employees’ favourable attitudes towards utilising the required programme practices. In particular, hotel managers should focus on hiring employees with a greater understanding of programme knowledge as the results indicated.

Based on existing research that indicates the importance of loyalty programmes, hotel organisations in China should be rigorous when hiring and training service staff on loyalty programmes, imparting their importance to branding as well as customer relationship management, and take into account employees’ customs and practices. Better training may help, and be beneficial for, hotel employees who feel concerned or experience frustration enacting the programme.

From a practical perspective, the findings underline the importance of cognitive drivers (awareness and knowledge) over affective drivers (concerns) in predicting employees’ intentions and behaviours. This has direct implications for hotel management. Specifically, managers should design training initiatives that move beyond general orientation sessions and focus instead on developing employees’ practical knowledge and situational awareness of LP operations. For example, training could include scenario-based learning modules where employees practice responding to real-world customer inquiries or challenges related to loyalty programme use. During training and assessment, organisations should approach actual cognitive–affective necessities of various functions, prioritising transferring knowledge in compliance-demanded functions and relying on emotions in customer-driven functions. Moreover, given the growing sophistication of digital tools, hotels should consider integrating AI-based platforms or simulation-based LP training into their training strategies. AI-driven chatbots, for instance, could simulate customer interactions and allow employees to practice programme-related conversations in a low-risk environment. Similarly, adaptive e-learning platforms powered by AI could personalise training content based on employees’ current knowledge levels—ensuring that more experienced staff receive advanced modules, while new hires focus on foundational concepts. It could be useful to propose training modules differentiated according to employees’ prior loyalty programme experience and level of concerns. This targeted approach would make training more efficient and impactful.

The results of this study not only add value to research on hotel management and hotel operations but also offer a new perspective to hoteliers who may view employees’ behaviour and intentions towards loyalty programmes as a factor in the selection and recruitment of their staff. During a potential interview process, human resource managers may touch on the employees’ loyalty programme knowledge and experiences at previous organisations in order to gain better insights into their past behaviour and overall intentions in implementing programme strategies. Organisations should embed continuous upskilling mechanism such as microlearning sessions, digital badges for completed modules, or gamified progress tracking—to maintain employee engagement with LPP over time.

This research provides empirical support for the associations among the connections linking employees’ knowledge, awareness, and concerns about loyalty programmes with their engagement, and for the relationship between their behaviour and intentions to implement programme practices.

Therefore, offering training to employees concerning the importance of loyalty programmes and their practices can increase their knowledge and awareness. The results suggest that intentions to implement loyalty programme practices, often influenced by loyalty programme knowledge and programme awareness, play a major role in determining the likelihood of Chinese hotel employees’ positive behaviour consistent with loyalty programme. On the other hand, our prediction that Chinese hotel employees’ concerns regarding loyalty programmes would positively predict the intention to implement, or in other words, focus on loyalty programme practices, was not supported. With this in mind, this study demonstrates that employee concerns regarding loyalty programmes do not strongly influence intention or behaviour. This implies that hotels should prioritise clarity and procedural guidance over efforts to increase employees’ emotional investment in loyalty programmes. Structured training, transparent communication of programme goals, and AI-supported learning platforms are, therefore, likely to be more effective levers for improving implementation outcomes than attempting to shape employee emotional commitment to the programmes alone.

In sum, this study contributes theoretically by broadening loyalty programme research into the Chinese hospitality context and, practically, by offering evidence-based recommendations for more targeted, technology-enhanced training strategies. Further investigations could research the effectiveness of AI-supported upskilling interventions and explore how digital tools might help bridge gaps in awareness and knowledge among frontline employees.

7. Conclusions

Identifying the factors that influence Chinese hotel employees’ LP Intentions in response to the demand from organisational management is important to the execution of loyalty programmes in the hospitality industry. Throughout this research, we examined the impact of three drivers—LP Knowledge, LP Awareness, and LP Concerns—on employees’ LP Intentions that mediate LP Behaviour. This research provides empirical evidence suggesting that LP Intention is stimulated by the investigated drivers and actions.

Findings show that awareness and knowledge are key drivers, fostering positive intentions that lead to consistent loyalty programme behaviour. By situating the analysis in the Chinese hotel industry, this study extends loyalty programme research beyond the predominantly Western focus of prior studies. In the Chinese context, cognitive factors like awareness and knowledge proved far more influential, suggesting that in structured, compliance-oriented work environments, practical readiness may outweigh emotional investment. This nuance adds a culturally specific dimension to loyalty programme research and informs management strategies in non-Chinese hospitality settings. This study, therefore, not only builds on existing research but also refines it by showing how cultural and organisational contexts shape the drivers of employee behaviour. It offers a clearer understanding of what motivates Chinese hotel employees to implement loyalty programme practices and how this shapes their overall engagement with such programmes.

8. Limitation and Direction for Future Research

Although this research study has made clear research contributions, it is important to acknowledge the various limitations that existed for future research. The results of this study offer some distinct insights but cannot be applied to a wider population. The majority of participants were Chinese, so including a more varied sample, like focusing on different demographics, such as non-Chinese employees, could lead to alternative findings. Moreover, the sample consisted exclusively of Chinese hotel employees working in luxury hotels. This may limit generalisability to budget or mid-range hotels, where factors such as training standards, organisational resources, and customer expectations may differ substantially. Future research may include a wider variety of hotels from budget to luxury and a broader selection of hotel staff in order to be more representative.

Finally, as this study focuses on the Chinese hotel industry, future research could replicate this experiment to examine other service industries that provide loyalty programmes as customer engagement strategies. Examples include the airline industry (frequent flyer programmes), retail (supermarket and department store reward schemes), telecommunications (subscriber loyalty incentives), and financial services (credit card rewards). Investigating these industries through an employee-focused lens could reveal sector-specific drivers of LP Behaviour and inform tailored training and management strategies.

Some of the relationships or hypotheses may not have been supported due to factors such as hierarchical culture, job insecurity, or other contextual influences. Therefore, conducting cross-cultural comparisons between Chinese and non-Chinese hotels is essential to better understand and validate the findings. To further enhance research robustness, future researchers may incorporate the marker-variable and consider incorporating the unmeasured latent methods factor to clarify and to rule out common method bias. Lastly, future studies could incorporate longitudinal or experimental designs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.R.M. and E.E.T.; methodology, T.R.M.; software, T.R.M.; validation, T.R.M.; formal analysis, T.R.M. and E.E.T.; investigation, T.R.M.; resources, T.R.M.; data curation, T.R.M.; writing—original draft preparation, T.R.M. and E.E.T.; writing—review and editing, T.R.M. and E.E.T.; visualization, T.R.M. and E.E.T.; supervision, E.E.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

According to art. No 7, par. 9 of the “Directive of the Dean of Comenius University Bratislava, Faculty of Management no. 3/2023”, the Ethics Council of Comenius University Bratislava, Faculty of Management (Ethics Council of FM CUB), declares that, based on the assessment of the application under registration no. 2024-KMAR-0001, the respective research project is in compliance with ethical standards of work with human research participants. The protocol was approved on 22 July 2024.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ahmad, R., Zainol, N. A., & Abu Karim, M. H. (2019). Intention to adopt Islamic quality standard: A study of hotels in Peninsular Malaysia. Journal of KATHA, 15(1), 20–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1980). Understanding attitudes and predicting social behaviour. Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Akroush, M. N., Abu ElSamen, A. A., Samawi, G. A., & Odetallah, A. L. (2013). Internal marketing and service quality in restaurants. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 31(4), 304–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arasli, H., Daşkın, M., & Saydam, S. (2014). Polychronicity and intrinsic motivation as dispositional determinants on hotel frontline employees’ job satisfaction: Do control variables make a difference? Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 109, 1395–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barari, M., Paul, J., Ross, M., Thaichon, S., & Surachartkumtonkun, J. (2022). Relationships among actors within the sharing economy: Meta-analytics review. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 103, 103215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battistelli, A., Montani, F., Odoardi, C., Vandenberghe, C., & Picci, P. (2014). Employees’ concerns about change and commitment to change among Italian organizations: The moderating role of innovative work behavior. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 25(7), 951–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhagwat Juhi. (2020). A study on role of loyalty membership programs in hotels. Available online: http://www.mahratta.org/CurrIssue/2020_March/10_study%20on%20Role%20of%20Loyalty-%20Juhi%20Bhagawat.pdf (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- Bidelman, G. M., Pearson, C., & Harrison, A. (2021). A temporoparietal circuit drives lexical influences on categorical speech perception. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 33(5), 840–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolisani, E., & Bratianu, C. (2018). The emergence of knowledge management. In Knowledge management and organizational learning (Vol. 4, pp. 23–47). Springer Nature. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, R. N., Kannan, P. K., & Bramlett, M. D. (2000). Implications of loyalty program membership and service experiences for customer retention and value. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 28(1), 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlini, J., & Grace, D. (2021). The corporate social responsibility (CSR) internal branding model: Aligning employees’ CSR awareness, knowledge, and experience to deliver positive employee performance outcomes. Journal of Marketing Management, 37(7–8), 732–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A., & Peng, N. (2014). Examining Chinese consumers’ luxury hotel staying behavior. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 39, 53–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, Y., Jeng, W., Acker, A., & Bowler, L. (2020). Affective, Behavioural, and cognitive aspects of teen perspectives on personal data in social media: A model of youth data literacy. Transforming Digital Worlds, 442–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, C. F., & Jang, S. C. (2008a). An expectancy theory model for hotel employee motivation. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 27(2), 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, C. F., & Jang, S. C. (2008b). The antecedents and consequences of psychological empowerment: The case of Taiwan’s hotel companies. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Research, 32(1), 40–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, A. C., Newmeyer, C. E., Jung, J. H., & Arnold, T. J. (2022). Frontline employee passion: A multistudy conceptualization and scale development. Journal of Service Research, 25(2), 194–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elidemir, S. N., Ozturen, A., & Bayighomog, S. W. (2020). Innovative behaviors, employee creativity, and sustainable competitive advantage: A moderated mediation. Sustainability, 12(8), 3295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elinor, F., & Lisa, M. L. (2022). Progressive or pressuring? The signalling effects of egg freezing coverage and other work–life policies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 108(1), 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engen, M., & Magnusson, P. (2015). Exploring the role of front-line employees as innovators. Service Industries Journal, 35(6), 303–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, T., & Alon, I. (2008). Human resources challenges and opportunities in China: A case from the hospitality industry. International Journal of Business and Emerging Markets, 1(2), 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (2011). Predicting and changing behavior: The reasoned action approach. In Predicting and changing behavior: The reasoned action approach. Psychology Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadenne, D. L., Kennedy, J., & McKeiver, C. (2009). An empirical study of environmental awareness and practices in SMEs. Journal of Business Ethics, 84(1), 45–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A. M. (2008). Does intrinsic motivation fuel the prosocial fire? Motivational synergy in predicting persistence, performance, and productivity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(1), 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigoryeva, A. (2023). Development of customer loyalty programs at hospitality enterprises under digitalization. Technoeconomics, 2(1), 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grönroos, C. (2020). Viewpoint: Service marketing research priorities. Journal of Services Marketing, 34(3), 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubíniová, K., Moller, T. R., Treľová, S., & Jarossová, M. A. (2023). Loyalty programmes and their specifics in the chinese hospitality industry—Qualitative study. Administrative Sciences, 13(6), 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halbesleben, J. R. B., Bowler, W. M., Bolino, M. C., & Turnley, W. H. (2010). Organizational concern, prosocial values, or impression management? How supervisors attribute motives to organizational citizenship behavior. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 40(6), 1450–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H., & Yoon, H. J. (2015). Hotel customers’ environmentally responsible behavioral intention: Impact of key constructs on decision in green consumerism. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 45, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanaysha, J., & Tahir, P. R. (2016). Examining the effects of employee empowerment, teamwork, and employee training on job satisfaction. Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences, 219, 272–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H., Li, Y., & Harris, L. (2012). Social identity perspective on brand loyalty. Journal of Business Research, 65(5), 648–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennig-Thurau, T., & Klee, A. (1997). The impact of customer satisfaction and relationship quality on customer retention: A critical reassessment and model development. Psychology and Marketing, 14(8), 737–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heskett, J. L., & Sasser, W. E. (2010). The service profit chain (pp. 19–29). Springer Boston. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, K. (2013). Chinese hotels in the eyes of Chinese hoteliers: The most critical issues. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 18(4), 354–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, V., Wirtz, J., Salunke, P., Nunkoo, R., & Sharma, A. (2023). Luxury hospitality: A systematic literature review and research agenda. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 115, 103597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S., Stephens, A. B., & Smith, R. W. (2024). Identifying different patterns of citizenship motives: A latent profile analysis. Occupational Health Science, 8(1), 191–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarideh, N. (2013). The investigation of effect of customer orientation and staff service-oriented on quality of service, customer satisfaction and loyalty in hyperstar stores. International Journal of Science and Research, 5. Available online: www.ijsr.net (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- Jiang, Y., Ritchie, B. W., & Verreynne, M. L. (2023). Building dynamic capabilities in tourism organisations for disaster management: Enablers and barriers. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 31(4), 971–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joint Wisdom. (2019). White paper of China’s hotel accommodation industry. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 21(3), 341–355. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, D. C., Kalmi, P., & Kauhanen, A. (2010). How does employee involvement stack up? the effects of human resource management policies on performance in a retail firm. Industrial Relations, 49(1), 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- June, S., & Mahmood, R. (2011). The relationship between person-job fit and job performance: A study among the employees of the service sector SMEs in Malaysia. International Journal of Business, Humanities and Technology, 1(2), 95–105. [Google Scholar]

- Kanapathipillai, K., & Azam, S. M. F. (2020). The impact of employee training programs on job performance and job satisfaction in the telecommunication companies in Malaysia. European Journal of Human Resource Management Studies, 4(3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandampully, J., & Suhartanto, D. (2000). Customer loyalty in the hotel industry: The role of customer satisfaction and image. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 12(6), 346–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, S. (1992). Beyond rationality: Clarity-based decision making. In Environment, cognition, and action. Oxfort University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, C., & So, K. K. F. (2015). Enhancing hotel employees’ brand understanding and brand-building behavior in China. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Research, 39(4), 492–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koeber, C., Appelbaum, E., Bailey, T., Berg, P., & Kalleberg, A. L. (2001). Manufacturing advantage: Why high-performance work systems pay off. Contemporary Sociology, 30(3), 250–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, B., Yu, J., & Han, H. (2020). The role of loyalty programs in boosting hotel guest loyalty: Impact of switching barriers. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 84, 102328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotchen, M. J., & Reiling, S. D. (2000). Environmental attitudes, motivations, and contingent valuation of nonuse values: A case study involving endangered species. Ecological Economics, 32(1), 93–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latham, G. P., Winters, D. C., & Locke, E. A. (1994). Cognitive and motivational effects of participation: A mediator study. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 15(1), 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, K. F. (2021). Recipes for customer loyalty: A cross-country study of the hotel industry. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 33(5), 1892–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leaman, C. (2018). Empowering frontline employees to deliver exceptional customer experience. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbestechcouncil/2018/08/07/empowering-frontline-employees-to-deliver-exceptional-customer-experience/ (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- Lee, J. S., Kim, J., Hwang, J., & Cui, Y. (2021). Does love become hate or forgiveness after a double deviation? The case of hotel loyalty program members. Tourism Management, 84, 104279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J., Xue, E., Li, C., & He, Y. (2023). Investigating latent interactions between students’ affective cognition and learning performance: Meta-analysis of affective and cognitive factors. Behavioral Sciences, 13(7), 555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X., Marler, J. H., & Cui, Z. (2012). Strategic human resource management in China: East meets west. Academy of Management Perspectives, 26(2), 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M., Ramírez-Esparza, N., & Chen, J. M. (2024). Accent attitudes: A review through affective, behavioural, and cognitive perspectives. Psychological Reports, 55(5), 466–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C. H. S., & Lee, T. (2019). The multilevel effects of transformational leadership on entrepreneurial orientation and service innovation. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 82, 278–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J., & Jo, W. M. (2020). Value co-creation behaviors and hotel loyalty program member satisfaction based on engagement and involvement: Moderating effect of company support. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 43, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z., Ma, E., & Li, A. (2021). Driving frontline employees performance through mentorship, training, and interpersonal helping: The case of upscale hotels in China. International Journal of Tourism Research, 23(5), 846–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Córcoles, M., & Vogus, T. J. (2020). Mindful organizing for safety. In Safety science (Vol. 124). Elsevier B.V. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayes, B. T., Finney, T. G., Johnson, T. W., Shen, J., & Yi, L. (2017). The effect of human resource practices on perceived organizational support in the People’s Republic of China. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 28(9), 1261–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McChesney, E. T., Schunn, C. D., DeAngelo, L., & McGreevy, E. (2025). Where to act, when to think, and how to feel: The ABC + model of learning engagement and its relationship to the components of academic performance. International Journal of STEM Education, 12(1), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melnyk, V., & Bijmolt, T. (2015). The effects of introducing and terminating loyalty programs. European Journal of Marketing, 49(3–4), 398–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, S., & Shi, J. (2017). Linking ethical leadership to employees’ organizational citizenship behavior: Testing the multilevel mediation role of organizational concern. Journal of Business Ethics, 141(1), 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moller, T. R. (2024). Assessing Chinese hotel employee’s motivation and involvement in the context of applying loyalty programme practices in international hotel chains in China. Administrative Sciences, 14(9), 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, M. M. (2009). Shades of green: A psychographic segmentation of the green consumer in Kuwait using self-organizing maps. Expert Systems with Applications, 36(8), 11030–11038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mount, D. J., & Back, K. J. (1999). A factor-analytic study of communication satisfaction in the lodging industry. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Research, 23(4), 401–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T. M., & Malik, A. (2022). Impact of knowledge sharing on employees’ service quality: The moderating role of artificial intelligence. International Marketing Review, 39(3), 482–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pangestuti, D. C. (2019). Analisis pengalaman kerja, kompetensi, pendidikan dan pelatihan terhadap pengembangan karir dengan intervening prestasi kerja. Jurnal Riset Manajemen Dan Bisnis (JRMB) Fakultas Ekonomi UNIAT, 4(1), 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patah, M. O. R. A., Zain, R. A., Abdullah, D., & Radzi, S. M. (2009). An empirical investigation into the influences of psychological empowerment and overall job satisfaction on employee loyalty: The case of Malaysian front office receptionists. Journal of Tourism Hospitality & Culinary Arts, 1(3). [Google Scholar]

- Perron, G. M., Côté, R. P., & Duffy, J. F. (2006). Improving environmental awareness training in business. Journal of Cleaner Production, 14(6–7), 551–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, L. H., Vieira, B. P., & Fernandes, T. M. (2020). ‘Service with a piercing’: Does it (really) influence guests’ perceptions of attraction, confidence and competence of hospitality receptionists? International Journal of Hospitality Management, 86, 102365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raie, M., Khadivi, A., & Khdaie, R. (2014). The effect of employees’ customer orientation, customer’s satisfaction and commitment on customer’s sustainability. Oman Chapter of Arabian Journal of Business and Management Review, 4(1), 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setti, I., Sommovigo, V., & Argentero, P. (2022). Enhancing expatriates’ assignments success: The relationships between cultural intelligence, cross-cultural adaptation and performance. Current Psychology, 41(7), 4291–4311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, M. F., Xu, S., Lim, W. M., Hasnain, M. F., & Nusrat, S. (2024). Cryptocurrency awareness, acceptance, and adoption: The role of trust as a cornerstone. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 11(1), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, R., Ji, S., Wang, X., & Li, F. (2016). Impacts of star-rated hotel expansion on inbound tourism development: Evidence from China. Applied Economics, 48(32), 3033–3048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamolampros, P., Korfiatis, N., Chalvatzis, K., & Buhalis, D. (2019). Job satisfaction and employee turnover determinants in high contact services: Insights from Employees’Online reviews. Tourism Management, 75, 130–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. (2024). Hotel industry in China—Statistics & facts. Statista. Available online: https://www.statista.com/topics/7232/hotel-industry-in-china/ (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- Traveldaily. (2022). Traveldaily suvey (2022 report). Available online: https://hub.traveldaily.cn/report/ (accessed on 18 August 2025). (In Chinese).

- Türkay, O., & Şengül, S. (2014). Employee behaviors creating customer satisfaction: A comparative case study on service encounters at a hotel. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/312526712 (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- Verma, V. K., & Chandra, B. (2018). Intention to implement green hotel practices: Evidence from Indian hotel industry. International Journal of Management Practice, 11(1), 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vihari, N. S., Rao, M. K., & Doliya, P. (2019). Organisational learning as an innovative determinant of organisational sustainability: An evidence based approach. International Journal of Innovation Management, 23(3), 19500191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K. Y., Ma, M. L., & Yu, J. (2021). Understanding the perceived satisfaction and revisiting intentions of lodgers in a restricted service scenario: Evidence from the hotel industry in quarantine. Service Business, 15(2), 335–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S., & Fränti, P. (2022). How power distance affect motivation in cross-cultural environment: Findings from Chinese companies in Europe. STEM Education, 2(2), 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J., Huang, S. S., & Teo, S. (2023). Effect of empowering leadership on work engagement via psychological empowerment: Moderation of cultural orientation. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 54, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C., & Law, K. (2002). Wong and law emotional intelligence scale (WLEIS). APA PsycTests. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]