Abstract

Ethical leadership is crucial for cultivating a committed and engaged workforce, but the specific psychological processes behind this link are not fully understood. Drawing on social learning and relational identity theories, we propose a multi-stage model where ethical leadership boosts employee engagement by first increasing supervisor–employee value congruence and then strengthening organizational identification. Using data from 444 employees and 375 supervisors, we found that ethical leadership indirectly influences employee engagement through this sequential process. This study confirms that ethical leadership fosters shared values between supervisors and employees, which in turn enhances an employee’s sense of belonging to the organization. This value congruence was found to be a full mediator between ethical leadership and organizational identification. This research contributes to leadership theory by detailing the psychological path from ethical leadership to employee engagement. Our findings also offer practical insights for organizations, emphasizing the need to focus on value alignment and leadership development to create a highly engaged workforce.

1. Introduction

In today’s hyper-competitive landscape, organizations rely heavily on a productive workforce to maintain and enhance their competitive edge. Yet, in the evolving knowledge economy, measuring productivity poses significant challenges. As Drucker (1999) famously noted, “the most important contribution management needs to make in the 21st century is to increase the productivity of knowledge work and knowledge workers.” Given these difficulties in quantifying outputs in knowledge-based roles, employee engagement has emerged as a reliable, measurable proxy that not only captures the energy and dedication employees bring to their work but also correlates with tangible performance outcomes.

Despite the established positive relationship between ethical leadership and employee engagement, several critical gaps remain in our understanding. First, existing research predominantly relies on single-stage mediation models that oversimplify the complex psychological mechanisms through which ethical leadership operates (Avolio et al., 2009). This approach fails to capture the nuanced, sequential processes that may better explain how ethical leadership translates into employee outcomes. Second, while organizational identification has been identified as a mediator, most studies assume a direct relationship between ethical leadership and organizational identification, overlooking the inherently interpersonal nature of ethical leadership delivery. Third, the role of value congruence as a critical precursor to organizational identification has been largely neglected, despite theoretical arguments suggesting that supervisor–employee value alignment may be fundamental to how employees come to identify with their organization.

This study addresses these gaps by proposing and testing a multi-stage mediation model that explicates the sequential psychological pathways through which ethical leadership influences employee engagement. Specifically, we argue that ethical leadership first creates value congruence between supervisors and employees, which then enhances organizational identification, ultimately leading to increased employee engagement.

An influential antecedent of employee engagement is ethical leadership (EL). Defined by Brown et al. (2005) as “the demonstration of normatively appropriate conduct through personal actions and interpersonal relationships, and the promotion of such conduct to followers through two-way communication, reinforcement, and decision-making,” ethical leadership has been shown to be among the most effective leadership styles for driving higher levels of employee commitment and engagement (Ng & Feldman, 2015). The principle of “doing the right thing” gains credibility when a leader’s actions align with their words, thereby establishing a foundation of trust. Such alignment not only directly impacts employee engagement but also exerts secondary effects on other critical organizational variables.

A significant body of research has explored how organizational identification (OI), which is an employee’s sense of oneness with their organization, mediates the relationship between ethical leadership and positive employee outcomes (Walumbwa et al., 2011). Nonetheless, the bulk of these studies treat the link between ethical leadership and organizational identification as largely direct. This overlooks the inherently interpersonal nature of ethical leadership, which suggests that deeper relational mechanisms may shape how employees come to identify with the organization. Consistent with social learning theory, which posits that individuals learn behaviors by observing and imitating role models, ethical leaders, as demonstrated by Santiago-Torner et al. (2024), may also mitigate negative employee states like emotional exhaustion by modeling resilience and fostering a supportive, ethical environment.

To address this gap, we propose that value congruence, the alignment of values between supervisor and employee, is a critical missing link in this process. Drawing on social learning theory and relational identity perspectives, we argue that ethical leadership fosters value congruence, which in turn strengthens organizational identification, ultimately leading to enhanced employee engagement.

Our study thus investigates this multi-stage mediation model to shed light on how ethical leadership influences employee engagement through the sequential mediating effects of value congruence and organizational identification. By emphasizing supervisor–employee relationships, we aim to provide richer insights into the mechanisms that underpin ethical leadership’s impact on engagement. These findings have important practical implications, including fostering stronger communication and emphasizing value alignment in the supervisor–employee dyad. Ultimately, a clearer understanding of these pathways can equip organizations with the tools to enhance employee engagement and, by extension, improve productivity and outperform competitors in today’s demanding marketplace.

This article is organized into six main sections. The Theoretical Framework section examines the theoretical foundations and develops our hypotheses. The Materials and Methods section details our research design, sample, and analytical procedures. The Results section presents empirical findings and hypothesis testing. The Discussion section interprets findings, explores implications, and acknowledges limitations. Finally, the Conclusion synthesizes key contributions and discusses the social value of our findings. This structure provides a comprehensive examination of how ethical leadership influences employee engagement through the sequential mediation of value congruence and organizational identification.

2. Theoretical Framework

Ethical leadership has garnered significant attention in organizational behavior and management studies due to its profound impact on employee attitudes and organizational outcomes. The historical development of ethical leadership is rooted in earlier leadership theories that emphasized the moral and ethical dimensions of leadership behavior. Bandura’s (1986) social learning theory provides a foundational framework for understanding ethical leadership. According to this theory, individuals learn behaviors by observing and imitating others, especially those in positions of authority or those they consider role models. In organizational settings, leaders are highly visible figures whose actions set the tone for acceptable behavior within the organization.

Building on this, Bass (1985) introduced the concept of idealized influence within his transformational leadership theory. Idealized influence refers to leaders who act as role models with high ethical standards, earning the trust and respect of their followers. These leaders demonstrate conviction and take stands based on their values and beliefs, which inspires followers to emulate their behavior.

Treviño et al. (2003) further expanded on the importance of ethical leadership by exploring perceptions of executive ethical leadership both inside and outside the executive suite. Their qualitative investigation revealed that ethical leaders are characterized not only by their personal integrity but also by their proactive efforts to promote ethical conduct among their followers. This involves the clear communication of ethical standards, reinforcement of ethical behavior, and consistent ethical decision-making.

While ethical leadership shares similarities with transformational and authentic leadership, it is distinct in its explicit focus on moral management. In fact, research shows that certain leader personality traits, particularly conscientiousness and agreeableness, serve as important dispositional antecedents of ethical leadership behaviors (Kalshoven et al., 2011). Transformational leadership, as described by Bass (1985), emphasizes inspiring and motivating followers to achieve extraordinary outcomes but does not necessarily prioritize ethical considerations in decision-making or behavior promotion.

Brown and Treviño (2006) highlight that ethical leadership uniquely combines being a moral person and a moral manager. Ethical leaders not only model ethical behavior themselves but also actively manage ethics within the organization by setting clear ethical standards, using rewards and punishments to reinforce those standards, and promoting open dialog about ethical issues. This active promotion of ethical conduct differentiates ethical leadership from other leadership styles that may implicitly assume ethical behavior without directly addressing it.

Ethical leadership has been empirically linked to various positive organizational outcomes, notably employee engagement. Employee engagement is defined as “a positive attitude held by the employee towards the organization and its values” (Markos & Sridevi, 2010, p. 89). It reflects the extent to which employees are emotionally and cognitively invested in their work, leading to higher levels of performance and organizational citizenship behaviors.

Several studies have demonstrated the positive impact of ethical leadership on employee engagement. Engelbrecht et al. (2017) found that ethical leadership significantly influences work engagement, with trust serving as a mediating variable. Ethical leaders build trust by consistently demonstrating integrity and fairness, which enhances employees’ willingness to fully engage in their work. Men (2015) explored the role of ethical leadership behaviors in internal communication, revealing that these positively affect employee engagement by improving communication symmetry and leader credibility. Ethical leaders foster transparent and open communication, making employees feel valued and informed, which boosts engagement.

Ethical leadership drives employee engagement through several mechanisms. First, employees observe and emulate the ethical behavior of their leaders (Bandura, 1986). When leaders act ethically, they set a standard for acceptable behavior, encouraging employees to internalize these values and engage more deeply with their work. Second, ethical leaders establish clear ethical norms and expectations, reducing ambiguity and creating a sense of security. This clarity allows employees to focus their energy on their tasks, increasing engagement. Third, ethical leaders are perceived as trustworthy and fair (Brown & Treviño, 2006). This perception fosters a positive organizational climate where employees feel respected and valued, leading to higher engagement levels. Lastly, by encouraging open dialog and listening to employees’ concerns, ethical leaders make employees feel heard and appreciated (Men, 2015). This inclusivity enhances employees’ emotional connection to the organization.

Neubert et al. (2009) demonstrated that ethical leadership behavior can influence the perceptions of an ethical climate, which subsequently positively affects organizational members’ flourishing, as measured by job satisfaction and affective commitment to the organization. Rich et al. (2010) showed that job engagement mediates the relationship between various job characteristics and job performance. Ethical leadership contributes to positive job characteristics by creating a supportive and ethical work environment, thus enhancing employee engagement and, subsequently, performance. Furthermore, Ng and Feldman (2015) conducted a meta-analysis confirming that ethical leadership is positively related to employee job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and reduced turnover intentions, factors closely associated with higher levels of employee engagement. Ng and Feldman also examined various moderators of the relationship between ethical leadership and outcomes, including organizational identification and value congruence.

Organizational identification (OI) refers to the perception of oneness with or belongingness to an organization (Ashforth & Mael, 1989). It represents the extent to which an individual defines themselves regarding their membership in a particular organization. The concept of organizational identification has its roots in social identity theory and has been extensively studied in organizational behavior research. As a moderator for ethical leadership, organizational identification plays a significant role. Employees who strongly identify with their organization are more likely to be influenced by ethical leadership and to engage in behaviors that benefit the organization. He et al. (2014) showed that a link between higher employee organizational identification and enhanced employee engagement exists.

Value congruence (VC) in a supervisor–employee dyad is understood as the extent to which the supervisor and subordinate share similar fundamental values and beliefs. This shared value system can facilitate better communication, mutual trust, and a higher-quality leader–member exchange, which in turn positively impacts performance and satisfaction (Kristof-Brown et al., 2005). Empirical research supports this theoretical perspective. Meglino et al. (1989) explored how value congruence between employees and their supervisors affects individual outcomes such as job satisfaction and organizational commitment. Their findings revealed that higher levels of value congruence are significantly associated with increased job satisfaction and commitment. By sharing similar values with their supervisors, employees are more likely to internalize the organization’s values as part of their own identity. This deepens their emotional and psychological attachment to the organization, leading to heightened commitment, enhanced engagement, and a willingness to go above and beyond in their roles. Treviño et al. (2003) explored the perceptions of executive ethical leadership from both inside and outside the executive suite. Their findings suggest that value congruence between leaders and followers plays a crucial role in the effectiveness of ethical leadership.

A critical gap in the current literature is that most studies examining the effects of ethical leadership and its potential mediators such as value congruence and organizational identification have relied on single-stage mediation models. Recent scholarly calls (Avolio et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2012) emphasize the need for multi-stage mediation frameworks to unravel the complex mechanisms by which leadership impacts employee outcomes. Avolio et al. (2009) advocate for more sophisticated models to capture the multifaceted nature of leadership, arguing that such models can reveal indirect effects that simpler, single-stage approaches may overlook. Similarly, Zhang et al. (2012) contend that multi-stage mediation models provide a more nuanced understanding of the pathways through which various leadership styles influence employees.

This issue is particularly pertinent for organizational identification. While ethical leadership is often experienced in a highly personal manner, existing research tends to assume a direct link between ethical leadership and organizational identification, thereby neglecting the critical role of the supervisor, the individual who delivers and embodies the ethical message. We propose that ethical leadership functions by first fostering value congruence between supervisors and employees. This alignment of core values then enhances organizational identification, which subsequently leads to improved employee engagement.

By elucidating the sequential processes that connect ethical leadership to employee engagement, our study seeks to offer deeper insights into the mechanisms through which leaders can effectively enhance organizational outcomes.

The relationship between value congruence and organizational identification can be explained through the lens of relational identity theory. The theoretical foundation of relational identity builds upon and extends social identity theory by highlighting the fundamental role of interpersonal relationships in shaping an individual’s self-concept (Sluss & Ashforth, 2007). Within organizational contexts, employees partially construct their self-definition through meaningful workplace relationships, particularly those with supervisors. This relational perspective serves as a critical intermediary in understanding organizational identification processes, as it acts as a ‘linchpin’ connecting individual identity to broader organizational attachments. When employees experience value congruence with their supervisors, the organization’s identity becomes more salient and attractive, thereby strengthening their organizational identification. This dynamic reflects how workplace relationships, nested within the organizational structure, function as conduits through which individuals experience and interpret their organizational environment (Sluss & Ashforth, 2008). This conceptualization aligns with dual-identity model research, which suggests that role relationships can bridge individual and organizational identities, potentially mitigating intergroup conflicts. Notably, the subordinate’s identification with the subordinate–manager relationship tends to align with their broader organizational identification, emphasizing the interconnected nature of relational and organizational identities in workplace settings.

The alignment of values at the interpersonal level provides a foundation for employees to forge a deeper connection with the organization, with the supervisor serving as a bridge between the individual and the broader organizational identity. Supporting this, Houston et al. (2024) found that value congruence not only amplifies the positive impact of ethical leadership on employee engagement but also reduces deviant behaviors. Van Gils et al. (2015) demonstrated that followers who are highly attuned to their leader’s ethical (and unethical) behaviors exhibit significantly lower levels of organizational deviance. Moreover, Babalola et al. (2019) showed that when subordinates perceive their leader’s ethical conviction as low, the beneficial effects of ethical leadership on discretionary behaviors are markedly weakened. Taken together, these findings underscore the critical role of supervisors in embodying and championing organizational values to enhance both employee engagement and organizational identification.

In conclusion, the literature reveals a complex interplay between ethical leadership, value congruence, and organizational identification. Ethical leadership lays the groundwork for positive organizational outcomes, while value congruence and organizational identification function as key mediating and moderating variables. The following hypotheses are developed to capture these relationships.

Hypotheses

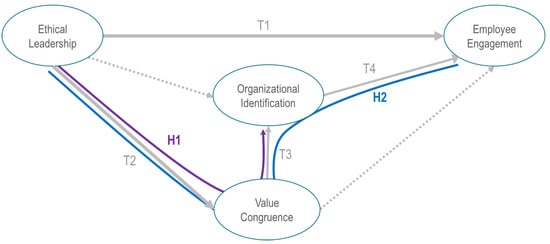

Our theoretical framework integrates social learning theory, relational identity theory, and social identity theory to explain how ethical leadership influences employee engagement through multiple pathways. We propose a multi-stage mediation model where ethical leadership’s effects flow through value congruence and organizational identification to ultimately enhance employee engagement (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Theorized model.

Building on relational identity theory, we propose that value congruence serves as a crucial mechanism translating ethical leadership into organizational identification. When ethical leaders create strong value alignment with employees, this congruence acts as a bridge connecting individual identity to organizational identity. This suggests the following:

Hypothesis 1:

Value congruence mediates the relationship between ethical leadership and organizational identification.

Finally, integrating our previous arguments, we propose a sequential mediation model where ethical leadership’s influence on employee engagement flows through both value congruence and organizational identification. This multi-stage process explains how leader–employee relationships ultimately translate into organizational-level outcomes, leading to the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2:

The relationship between ethical leadership and employee engagement is sequentially mediated by value congruence and organizational identification.

To ensure the validity of our model and data, we conducted four tests based on theoretical relationships that have been well established in prior research. Ethical leadership has consistently demonstrated positive effects on employee engagement across various organizational contexts. Recent research by Wibawa and Takahashi (2021) also demonstrated a positive and significant direct effect of ethical leadership on work engagement, reinforcing its role as a crucial antecedent in fostering employee dedication and vigor. When leaders demonstrate strong ethical principles and encourage ethical conduct, employees develop greater trust in leadership and the organization, leading to enhanced work engagement (Engelbrecht et al., 2017). Therefore, we propose the following test:

T1:

Ethical leadership is positively associated with employee engagement.

Drawing on social learning theory (Bandura, 1986) and the concept of idealized influence (Bass, 1985), we argue that ethical leaders serve as powerful role models who demonstrate and reinforce organizational values through their actions and decisions. Through consistent ethical behavior and two-way communication, leaders help employees internalize these values, leading to stronger value alignment between supervisor and employee. This process is particularly salient in direct supervisor–employee relationships, where daily interactions provide numerous opportunities for value transmission and reinforcement. Thus, we propose the following test:

T2:

Ethical leadership is positively associated with supervisor–employee value congruence.

Relational identity theory provides a robust framework for understanding how supervisor-level value congruence translates into organizational identification. According to Sluss and Ashforth (2007), employees partially construct their self-definition through workplace relationships, particularly with supervisors. When employees experience strong value alignment with their supervisor, they are more likely to internalize organizational values and develop a stronger sense of organizational identification. This occurs because of the following:

Supervisors serve as organizational representatives, making their values proxy for organizational values.

- Value congruence creates positive relational experiences that employees associate with the broader organization.

- Shared values with supervisors make organizational identity more salient and attractive.

- Empirical research supports this perspective, with studies showing that supervisor–employee value congruence significantly predicts organizational identification (Meglino et al., 1989). Therefore, we propose the following test:

T3:

Supervisor–employee value congruence is positively associated with organizational identification.

When employees strongly identify with their organization, they are more likely to invest energy and enthusiasm in their work roles. This occurs because organizational identification creates a psychological merger between self and organization, making organizational success personally meaningful (Ashforth & Mael, 1989). Strong organizational identification leads employees to view their work as more meaningful and worthwhile, enhancing engagement. Thus, we propose the following test:

T4:

Organizational identification is positively associated with employee engagement.

The hypotheses and validity tests outlined above lead directly into our research design. The subsequent methodology section explains how we operationalized these concepts and tested the proposed model.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sample Selection and Data Collection

The survey data is based on secondary data sources. It was provided for free via openICPSR, a service of the Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research (ICPSR). OpenICPSR is a self-publishing repository for social, behavioral, and health sciences research data. Lawrence Houston, Rutgers University, provided the data from his ethical leadership study. He provided two distinct files, study 1 and study 2. This paper uses the data from study 2 exclusively. The data collected was used in the article “Does Value Similarity Matter? Influence of Ethical Leadership on Employee Engagement and Deviance,” published in the Group & Organization Management (GOM) journal on 9 September 2022. The author’s main goal was to explore deviance and ethical leadership. This paper uses the collected data of the control variables to explore the stated hypothesis. The following description of the survey is based on the published article by Houston (2021), the primary collectors of the data. The original data collection followed institutional review board guidelines at the collecting university. The participants provided informed consent, and anonymity was maintained through coding procedures that separated identifying information from survey responses. All participation was voluntary.

3.2. Sample Characteristics

The participants were recruited from a part-time MBA program at a large university in the southeastern United States. Five hundred and fifty-one students who were working full time were invited to participate in this study. This sampling method enhanced the generalizability of the findings by including participants from a variety of industries (e.g., retail, healthcare, education, technology, and entertainment). The survey participants provided the personal email addresses of their supervisors, who were then sent a survey invitation, allowing us to collect multi-source data at two time points, time 1 (follower survey) and time 2 (leader survey). Surveys were collected at three time points (each separated by 2 weeks) to temporally lag the collection of our exogenous and endogenous variables and, thus, reduce the likelihood of method bias (Mitchell & James, 2001; Podsakoff et al., 2003). A total of 1804 employees completed the first survey; 1318 completed the second survey (73% retention rate), which asked participants to provide demographic information and their supervisors’ contact information. In instances where two or more participants had the same supervisor, the supervisor was asked to complete separate surveys for each participant. Overall, we had 444 employee surveys matched with complimentary surveys from 375 different supervisors. In our sample (N = 444), approximately 60% of the employees were women and 60% identified as Caucasian, with an average tenure on the job of 5.96 years (SD = 6.92). The average age of employees was 33.75 (SD = 12.48). Approximately 43% of their supervisors were women and 74% identified as Caucasian, and their average organizational tenure was 11 years (SD = 8.63). The average age of supervisors was 41.89 (SD = 11.08).

3.3. Measures and Factor Analysis Confirmation

The study variables were assessed through a reliability analysis and a confirmatory factor analysis. Ethical leadership (EL) was measured using the 10-item Ethical Leadership Scale (Brown et al., 2005). The scale demonstrated excellent internal consistency reliability (Cronbach’s α = 0.94), exceeding the recommended 0.70 cutoff. All items exhibited high item–total correlations.

Value congruence (VC) was assessed using the four-item scale by Becker et al. (1996), which included statements such as “The reason I prefer my leader to others is because of what he or she stands for, that is, his/her values. This scale exhibited good reliability (α = 0.85), with high item–total correlations.

Organizational identification (OI) was measured using Mael and Ashforth’s (1992) six-item measure of organizational identification, which included statements such as “When someone criticizes my organization, it feels like a personal insult.” Reliability was good (α = 0.84), with high item–total correlations.

Work engagement (WE) was assessed using the 18-item scale by Rich et al. (2010), based on Kahn’s (1990) conceptualization. This scale exhibited high reliability (α = 0.96) and high item–total correlations. Sample items included “I am proud of my job” (i.e., emotional engagement), “I exert my full effort to my job” (i.e., physical engagement), and “At work, I am absorbed by my job” (i.e., cognitive engagement). Appendix A lists all items for each variable used.

3.4. Analytical Methods

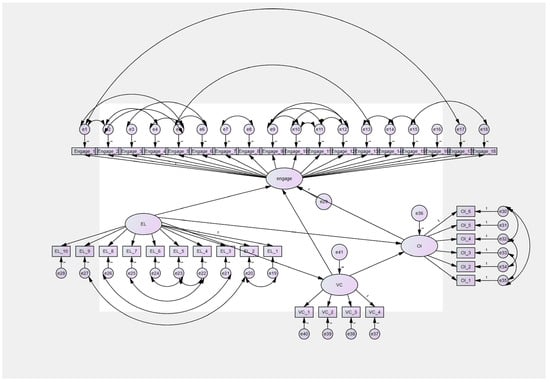

Using SPSS AMOS 29 for structural equation modeling, we investigated all model paths and correlations to assess the robustness of the model fit and analyze significant relationships between the latent variables using the established factors (Figure 2). The theoretical model demonstrated a good fit to the data: χ2(630) = 1503, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.94, and RMSEA = 0.058. Multiple significant paths emerged between the latent variables.

Figure 2.

Illustration of the total model.

4. Results

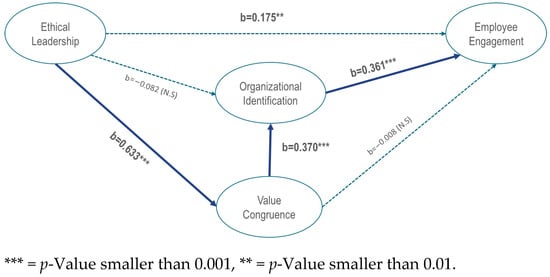

Hypothesis 1 was supported. As can be seen in Table 1, ethical leadership was associated with higher value congruence (b = 0.633, p < 0.01), which in turn was associated with higher organizational identification (b = 0.377, p < 0.001). The path from ethical leadership to organizational identification was mediated by value congruence, b = 0.24, p < 0.01; CI 95% = (0.167, 0.360). The remaining direct effect of ethical leadership on organizational identification was not significant (b = 0.008, n.s.).

Table 1.

Standardized path coefficients.

Hypothesis 2 was supported. Ethical leadership was associated with higher value congruence (b = 0.633, p < 0.01), which in turn was associated with higher organizational identification (b = 0.377, p < 0.001) which in turn was associated with higher employee work engagement (b = 0.361, p < 0.001). The bootstrap method was employed 2000 (times) to investigate the indirect effect of ethical leadership on work engagement. That relationship was significant, b = 0.127, p < 0.01; CI 95% = (0.029, 0.225). The remaining direct effect of ethical leadership on employee work engagement was significant (b = 0.175, p = 0.005).

To further strengthen the robustness of our results, we compared different models and assessed their fit indices. Model 1 represents the theoretical model used in this study, including ethical leadership (EL), value congruence (VC), organizational identification (OI), and employee engagement (WE) (Figure 3). Model 2 is identical to Model 1 but omits value congruence from the analysis. Model 3 is the same as Model 1 but excludes organizational identification to explore all potentials.

Figure 3.

Standardized coefficients of the SEM model.

All three models demonstrate acceptable fit metrics; however, Model 1 exhibits the strongest fit indices and the highest explanatory power, supporting the full mediation effect of organizational identification by value congruence. Specifically, Model 1 yielded fit indices of χ2 (p < 0.001), CFI = 0.94, RMSEA = 0.057, and CMIN/DF = 2.387. In contrast, Model 2 showed a similar fit with χ2 (p < 0.001), CFI = 0.94, RMSEA = 0.068, and CMIN/DF = 2.681, but the direct relationship between EL and OI remained significant (b = 0.331, p < 0.01). Model 3 exhibited a slightly poorer fit (χ2 (p < 0.001), CFI = 0.88, RMSEA = 0.078, and CMIN/DF = 3.527), and the relationship between value congruence and employee engagement remained non-significant, as in Model 1.

These comparisons indicate that including both value congruence and organizational identification in the model provides a better fit to the data and supports the proposed sequential mediation effect.

Validity Tests

All four tests were confirmed, suggesting that the model is robust and theoretically sound. Test 1 was supported, as ethical leadership significantly positively affected employee engagement (b = 0.175, p = 0.005). This finding aligns with previous research (e.g., Ng & Feldman, 2015) demonstrating the beneficial impact of ethical leadership on employee engagement. Test 2 was supported, as ethical leadership significantly positively affected value congruence (b = 0.663, p < 0.001). Test 3 was supported, with value congruence positively affecting organizational identification (b = 0.377, p < 0.001). Test 4 was supported, with organizational identification positively and significantly predicting employee engagement (b = 0.361, p < 0.001).

5. Discussion

This study investigated the complex relationships between ethical leadership, value congruence, organizational identification, and employee engagement using a multi-stage mediation model. Our primary contribution lies in revealing the true psychological pathways through which ethical leadership operates, challenging the fundamental assumptions in existing research about direct effects.

The most significant finding of our study is the full mediation of the ethical leadership–organizational identification relationship through value congruence. This finding has profound theoretical implications that extend beyond our specific sample or context. Full mediation indicates that value congruence is the actual psychological mechanism through which ethical leadership creates organizational identification, not merely one pathway among many, but the fundamental process itself.

Full mediation indicates that the assumed direct link between the predictor and the outcome is actually misleading. In this context, ethical leadership does not directly foster organizational identification; instead, it influences it indirectly through establishing value alignment between supervisors and employees. This suggests that value congruence is a crucial prerequisite; without it, ethical leadership alone cannot produce the psychological unity between individual and organizational identity that constitutes organizational identification. This finding directly challenges numerous studies that report significant direct effects between ethical leadership and organizational identification. Studies such as Walumbwa et al. (2011) and Mayer et al. (2009) have found significant direct relationships between these constructs. However, our full mediation finding suggests that these studies may have obtained distorted results by failing to account for the critical mediating mechanism of value congruence.

When research models do not measure or include value congruence or similar concepts, the statistical link between ethical leadership and organizational identification appears straightforward. However, the actual influence of value congruence between the employee and the manager always exists. Consequently, what seems like a direct effect is really the combined result of two sequential connections: first, ethical leadership fostering value congruence (β = 0.633 in our study), and second, value congruence promoting organizational identification (β = 0.377). Studies that omit value congruence suffer from model misspecification. They observe a relationship between ethical leadership and organizational identification and conclude it is direct, when in reality, they are observing the total effect that operates through the unmeasured mediator of value congruence. This model misspecification has led the field to fundamentally misunderstand how ethical leadership operates, resulting in potentially ineffective leadership development programs that focus on behaviors rather than value alignment processes. This is analogous to studying the relationship between education and income while ignoring skills acquisition—the observed relationship exists, but the mechanism is misunderstood.

Our validity tests further support these findings, confirming the expected positive relationships between ethical leadership and employee engagement (T1), ethical leadership and value congruence (T2), value congruence and organizational identification (T3), and organizational identification and employee engagement (T4). These tests demonstrate the robustness of our theoretical model and provide additional evidence for the proposed mechanisms.

5.1. Practical Implications for Managers

Enhancing value congruence within an organization involves personalized communication that reinforces the alignment between managers and employees. Supervisors can hold individual alignment sessions, such as one-on-one or team meetings, to discuss how each employee’s role and personal values align with the team’s values. This approach reinforces a shared sense of purpose and demonstrates that leaders are relatable and committed to the same principles. For example, a leader might say, “I am making this decision because of our shared value of integrity,” highlighting that decisions are grounded in common beliefs and that the manager shares the same values as the employee.

Involving employees in refining and updating the group’s values further strengthens this alignment. Soliciting subordinates’ input on values can increase buy-in and ensure that the values resonate with the workforce. This participative process makes employees feel valued and heard, enhancing their connection to their manager. When employees see their contributions reflected in the team’s values, it reinforces the idea that everyone is working towards the same goals guided by the same principles.

Managers should consistently model the team’s values in their actions and decisions, openly communicating how these choices reflect shared values. This transparency builds trust and reinforces that supervisors and employees are united in their commitment to the organization’s mission. Focusing on communication that emphasizes shared values and fostering value congruence, managers can enhance the positive impact of their ethical leadership on employee work engagement.

5.2. Methodological Contributions and Model Comparison

Our model comparison analysis strengthens the confidence in our findings. When we omitted value congruence (Model 2), the direct relationship between ethical leadership and organizational identification became significant (β = 0.331, p < 0.01), demonstrating exactly the pattern that previous research has observed. This provides empirical evidence that studies omitting value congruence will observe apparent direct effects that disappear when the true mediating mechanism is properly specified. Our sequential mediation model (EL → VC → OI → WE) explained variance more effectively than alternative configurations, supporting the theoretical argument that value alignment must precede organizational identification rather than operating in parallel. This temporal ordering has important practical implications for leadership development interventions.

While our model explains 20% of the variance in employee engagement—a medium effect size by Cohen’s (1988) standards and comparable to other leadership studies—this figure should be interpreted in the context of our primary theoretical contribution. The R2 value, while meaningful, is secondary to the discovery of the true causal pathway. Understanding the correct mechanism through which ethical leadership operates is more valuable than maximizing explained variance through model complexity.

5.3. Integration with Contemporary Research

Recent developments in ethical leadership research support our multi-stage mediation approach. Kalra et al. (2025) found enhanced effects when combining ethical leadership with individual-level factors, suggesting that multiple mediating mechanisms may operate simultaneously. This aligns with our finding that understanding the complete mediational pathway is crucial for maximizing ethical leadership effectiveness.

The increasing prevalence of remote and hybrid work arrangements makes our focus on supervisor–employee value congruence particularly relevant. Traditional ethical leadership behaviors may be less visible in virtual environments, making the value alignment process even more critical for maintaining organizational identification and engagement. This becomes particularly critical as traditional face-to-face interactions that facilitate value transmission are reduced, requiring leaders to be more intentional about value alignment processes through virtual communications.

While some studies have identified alternative mediators such as trust (Engelbrecht et al., 2017) or leader–member exchange (Walumbwa et al., 2011), our findings suggest that these mechanisms may themselves operate through or alongside value congruence rather than replacing it as the fundamental pathway. Future research should examine how these various mechanisms interact within the broader value congruence framework we have identified.

Recent meta-analytic evidence further supports the cultural contingency of our findings. Amory et al. (2024) conducted a comprehensive cross-temporal and cross-cultural meta-analysis examining ethical leadership across 15 years and multiple cultural contexts. Their findings reveal significant cross-cultural variability in both the manifestation of ethical leadership behaviors and their relationships with follower outcomes. This meta-analytic evidence reinforces our concern that the value congruence mechanism we identified may be particularly pronounced in individualistic cultures where personal value alignment is culturally emphasized. The findings from Amory et al. (2024) suggest that the strength of ethical leadership effects varies substantially across cultural contexts, lending support to our argument that the 60% Caucasian composition of our sample may limit generalizability. Their work demonstrates that ethical leadership research has predominantly focused on Western samples, creating a knowledge gap about how ethical leadership operates in collectivistic cultures—exactly the limitation we acknowledge in our study.

5.4. Limitations and Future Research

Despite the valuable insights provided by this study, several limitations warrant discussion. First, the cross-sectional nature of the data limits the ability to draw definitive causal inferences. Although the multi-wave design helps mitigate some common method biases, future studies should employ longitudinal or experimental designs to more robustly establish the causality among ethical leadership, value congruence, organizational identification, and employee engagement. Second, the data were drawn from a specific cultural and organizational context, which may restrict the generalizability of the findings. Resick et al. (2006) compared EL perceptions in U.S. and Taiwanese samples, highlighting that cultural norms influence the ‘idealized influence’ and ‘moral management’ facets of ethical leadership. Future research should replicate the model in diverse cultural settings and industries to examine the universality of the proposed relationships and to identify any context-specific dynamics. Third, while this study focused on the direct dyadic relationship between supervisors and employees, it did not consider the potential influence of broader organizational factors such as executive leadership styles or organizational culture. Future research could extend the current model by incorporating these higher-level variables, thereby offering a more comprehensive view of how ethical leadership cascades through multiple organizational layers. Fourth, the cultural composition of our sample (60% Caucasian, predominantly Western cultural background) may limit the generalizability of our findings across diverse cultural contexts. Our value congruence mechanism may be particularly salient in individualistic cultures where personal value alignment with supervisors is highly emphasized. In collectivistic cultures, organizational identification might develop more directly from ethical leadership through alternative pathways such as respect for authority or group-level value processes, potentially altering the sequential mediation pattern we identified. The strength of the relationships in our model may also reflect cultural predispositions toward individualistic value alignment processes. Future cross-cultural research is needed to establish the universality of our findings and identify cultural boundary conditions for the ethical leadership–value congruence–organizational identification pathway.

Additionally, our study did not account for the role of trust, which meta-analytic evidence suggests is a critical mediator in leadership–performance relationships. Legood et al. (2020) demonstrated through a meta-analysis that trust serves as a key mechanism linking leadership behaviors to follower outcomes across various leadership styles. While our focus on value congruence reveals an important pathway, the omission of trust as a potential competing or complementary mediator represents a limitation that future research should address. It remains unclear whether value congruence operates independently of trust or whether these mechanisms interact in more complex ways within the ethical leadership process.

6. Conclusions

This study advances our understanding of ethical leadership’s influence on employee engagement by demonstrating that this relationship operates through a sequential mediation process involving supervisor–employee value congruence and organizational identification. Our findings provide both theoretical insights and practical guidance for organizations seeking to enhance employee engagement through ethical leadership practices.

Our multi-stage mediation model explains 20% of the variance in employee engagement, which represents a meaningful effect size in organizational behavior research. According to Cohen’s (1988) conventions, this falls within the medium effect size range and is comparable to other leadership studies in the field. The model demonstrated good fit indices (χ2 = 1503, CFI = 0.94, RMSEA = 0.058, and CMIN/DF = 2.387), indicating that our theoretical framework adequately represents the data structure.

By integrating social learning and relational identity theories, we demonstrate that ethical leadership’s effects are more nuanced than previously understood. Crucially, the full mediation of the ethical leadership–organizational identification relationship through value congruence reveals a fundamental truth about the underlying psychological process: value congruence is the actual source of organizational identification, not ethical leadership per se. This full mediation indicates that ethical leadership only influences organizational identification to the extent that it creates value alignment between supervisors and employees.

This finding has profound implications for existing research. Previous studies that assume or report direct relationships between ethical leadership and organizational identification (e.g., Walumbwa et al., 2011; Mayer et al., 2009) may have obtained distorted or incomplete results by omitting the critical mediating mechanism of value congruence. When value congruence is not measured or included in the model, the statistical relationship between ethical leadership and organizational identification appears direct, but this represents a misspecification of the true underlying process. Our full mediation finding suggests that this apparent direct effect is actually a spurious relationship that disappears when the true mediating mechanism is properly specified.

This theoretical revelation means that value congruence operates as a necessary condition for ethical leadership to generate organizational identification. Without value alignment, ethical leadership behaviors alone are insufficient to create the psychological merger between individual and organizational identity that defines organizational identification. This challenges the field to reconceptualize how ethical leadership operates and suggests that many previous studies may have oversimplified this complex process by failing to account for the relational value alignment mechanism that actually drives the relationship.

The sequential nature of our mediation model offers specific guidance for leadership development programs. Rather than treating value congruence and organizational identification as independent outcomes, our results suggest that leaders must first establish value alignment before expecting enhanced organizational identification and subsequent engagement. This sequential understanding provides a roadmap for implementing ethical leadership initiatives that maximize employee engagement outcomes.

6.1. Study Limitations and Quality Assessment

Although our model is theoretically sound and practically relevant, it has limitations. Value congruence and organizational identification are key pathways, but they capture only part of the complex effects of ethical leadership. The cross-sectional nature of our data limits our ability to establish definitive causal relationships, despite the multi-wave design that helps mitigate common method bias concerns. Additionally, our sample, drawn from part-time MBA students in the southeastern United States, may limit the generalizability across different cultural contexts, educational backgrounds, and geographical regions. The reliance on self-reported measures, even when supplemented by supervisor ratings, introduces potential response bias that future research should address through objective performance metrics or observational methods.

6.2. Relevance to Current Organizational Trends

These findings are particularly relevant in today’s rapidly evolving workplace environment. As organizations navigate increasing diversity, remote work arrangements, and heightened expectations for ethical behavior, understanding how ethical leadership creates value alignment becomes crucial for maintaining engaged workforces. The COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent shifts to hybrid work models have made supervisor–employee relationships more critical yet more challenging to maintain, making our focus on value congruence especially timely.

Furthermore, growing generational diversity in the workplace, with millennials and Generation Z placing greater emphasis on value-driven organizations, makes the value congruence mechanism increasingly important for employee retention and engagement. Our findings suggest that ethical leaders who can effectively communicate organizational values and create alignment with diverse employee value systems will be better positioned to lead engaged, high-performing teams.

6.3. Future Research Directions

Our study opens several avenues for future investigation. First, longitudinal research designs could better establish the causal ordering of our proposed relationships and examine how value congruence develops over time within supervisor–employee dyads. Such studies could reveal whether value alignment occurs gradually through repeated interactions or emerges more rapidly through specific pivotal experiences.

Second, cross-cultural research is needed to examine whether our findings generalize across different national and organizational cultures. Given that ethical leadership perceptions vary across cultures (Resick et al., 2006), the mechanisms through which ethical leadership operates may also be culturally contingent. Future studies should explore how cultural values moderate the relationships in our model.

Third, researchers should investigate additional mediating mechanisms that might work alongside or instead of value congruence, such as trust, psychological safety, leader–member exchange quality, or communication effectiveness. These variables might help explain additional variance in the ethical leadership–employee engagement relationship and provide a more comprehensive understanding of the process.

Fourth, the role of organizational context deserves further attention. Factors such as organizational size, industry characteristics, hierarchical structure, and organizational climate may moderate the strength of the relationships in our model. Understanding these boundary conditions would help organizations determine when and how to implement value alignment initiatives most effectively.

6.4. Social Value and Broader Implications

This research offers substantial social value by addressing the key challenges prevalent in contemporary society. Amid declining institutional trust, rising workplace inequality, and heightened concerns regarding corporate responsibility, examining the role of ethical leadership in cultivating engaged workforces holds significant societal ramifications beyond organizational contexts. The findings indicate that ethical leadership, when enacted through value congruence, contributes to the development of more inclusive workplaces. Leaders who intentionally align organizational values with those of diverse employees promote a sense of belonging and mitigate marginalization. This approach is particularly vital for addressing systemic inequities, as value alignment can bridge cultural, generational, and socioeconomic gaps that often hinder full participation within organizations. By elucidating how value congruence mediates the impact of ethical leadership, this study outlines strategic pathways for organizations to enhance their social responsibility. Engagement fostered by aligned ethical values supports the maintenance of high ethical standards, reduces the likelihood of corporate misconduct, and encourages positive contributions to surrounding communities, thereby creating a multiplier effect that extends the influence of ethical leadership throughout society.

6.5. Concluding Remarks

This research demonstrates that ethical leadership’s influence on employee engagement operates through a sophisticated, sequential process rather than through simple direct effects. By highlighting the pivotal role of supervisor–employee value congruence as a precursor to organizational identification, we provide both theoretical advancement and practical guidance for organizations seeking to enhance employee engagement through ethical leadership development.

The finding that value congruence fully mediates the relationship between ethical leadership and organizational identification fundamentally changes how we understand the ethical leadership process. It suggests that the “what” of ethical leadership (the behaviors and decisions) must be accompanied by careful attention to the “how” of value communication and alignment. This insight offers actionable guidance for leadership development programs and provides a clear pathway for organizations to enhance employee engagement through deliberate value alignment initiatives.

Beyond organizational boundaries, this research contributes to addressing critical societal challenges including workplace inequality, corporate responsibility, mental health, economic resilience, and democratic governance. By providing evidence-based approaches to creating engaged workforces through ethical means, our findings support building more equitable, sustainable, and democratic organizations that serve not only businesses’ interests but broader social good.

As organizations continue to face unprecedented ethical challenges and evolving workforce expectations, these findings underscore that effective ethical leadership requires more than good intentions and appropriate behaviors—it demands a sophisticated understanding of how values are communicated, shared, and internalized within supervisor–employee relationships. Organizations that master this value alignment process will be better positioned to cultivate the engaged, committed workforce necessary for a sustained competitive advantage while simultaneously contributing to a more ethical, inclusive, and prosperous society.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This paper is based on secondary data and discovers novel insight on results that previously have not been published. The original data collection complied with all ethical codes for human subjects.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable since it is based on secondary data.

Data Availability Statement

The data set is available over OpenICPRS and is free to use for research as long it is properly cited. (Houston, 2021) Houston, Lawrence. Ethical Leadership Study 2 Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor], 17 February 2021. https://doi.org/10.3886/E132621V1. Links to an external site. https://www.openicpsr.org/openicpsr/project/132621/version/V1/view;jsessionid=03829561AD8CF3E093DC0859A247B3D1 (accessed on 10 July 2024).

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the author used Copilot (v1.99) and Claude 4.1 for the purposes of helping with generating text. The author has reviewed and edited the output and takes full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

| EL_1 | Please rate the extent to which you agree with the following statements. My leader…—Conducts his/her personal life in an ethical manner |

| EL_2 | Please rate the extent to which you agree with the following statements. My leader…—Defines success not just by results but also the way that they are obtained |

| EL_3 | Please rate the extent to which you agree with the following statements. My leader…—Listens to what employees have to say |

| EL_4 | Please rate the extent to which you agree with the following statements. My leader…—Disciplines employees who violate ethical standards |

| EL_5 | Please rate the extent to which you agree with the following statements. My leader…—Makes fair and balanced decisions |

| EL_6 | Please rate the extent to which you agree with the following statements. My leader…—Can be trusted |

| EL_7 | Please rate the extent to which you agree with the following statements. My leader…—Discusses business ethics or values with employees |

| EL_8 | Please rate the extent to which you agree with the following statements. My leader…—Sets an example of how to do things the right way in terms of ethics |

| EL_9 | Please rate the extent to which you agree with the following statements. My leader…—Has the best interests of employees in mind |

| EL_10 | Please rate the extent to which you agree with the following statements. My leader…—When making decisions, asks “what is the right thing to do?” |

| Engage_1 | Please indicate your agreement with the following statements.—I work with intensity on my job |

| Engage_2 | Please indicate your agreement with the following statements.—I exert my full effort to my job |

| Engage_3 | Please indicate your agreement with the following statements.—I devote a lot of energy to my job |

| Engage_4 | Please indicate your agreement with the following statements.—I try my hardest to perform well on my job |

| Engage_5 | Please indicate your agreement with the following statements.—I strive as hard as I can to complete my job |

| Engage_6 | Please indicate your agreement with the following statements.—I exert a lot of energy on my job |

| Engage_7 | Please indicate your agreement with the following statements.—I am enthusiastic in my job |

| Engage_9 | Please indicate your agreement with the following statements.—I am interested in my job |

| Engage_10 | Please indicate your agreement with the following statements.—I am proud of my job |

| Engage_11 | Please indicate your agreement with the following statements.—I feel positive about my job |

| Engage_12 | Please indicate your agreement with the following statements.—I am excited about my job |

| Engage_13 | Please indicate your agreement with the following statements.—At work, my mind is focused on my job |

| Engage_14 | Please indicate your agreement with the following statements.—At work, I pay a lot of attention to my job |

| Engage_15 | Please indicate your agreement with the following statements.—At work, I focus a great deal of attention on my job |

| Engage_16 | Please indicate your agreement with the following statements.—At work, I am absorbed by my job |

| Engage_17 | Please indicate your agreement with the following statements.—At work, I concentrate on my job |

| Engage_18 | Please indicate your agreement with the following statements.—At work, I devote a lot of attention to my job |

| OI_1 | Please rate the extent to which you agree with the following statements.—When someone criticizes my organization, it feels like a personal insult. |

| OI_2 | Please rate the extent to which you agree with the following statements.—I am very interested in what others think about my organization. |

| OI_3 | Please rate the extent to which you agree with the following statements.—When I talk about my organization, I usually say ‘we’ rather than ‘they’. |

| OI_4 | Please rate the extent to which you agree with the following statements.—My organization’s successes are my successes. |

| OI_5 | Please rate the extent to which you agree with the following statements.—When someone praises my organization, it feels like a personal compliment. |

| OI_6 | Please rate the extent to which you agree with the following statements.—If a story in the media criticized my organization, I would feel embarrassed. |

| VC_1 | Please indicate your agreement with the following statements.—If the values of my manager were different, I would not be as attached to him/her. |

| VC_2 | Please indicate your agreement with the following statements.—Since starting this job, my personal values and those of my manager have become more similar. |

| VC_3 | Please indicate your agreement with the following statements.—The reason I prefer my manager to others is because of what he or she stands for, that is, his/her values. |

| VC_4 | Please indicate your agreement with the following statements.—My attachment to my manager is primarily based on the similarity of my values and those represented by him/her. |

References

- Amory, J., Wille, B., Wiernik, B. M., & Dupré, S. (2024). Ethical leadership on the rise? A cross-temporal and cross-cultural meta-analysis of its means, variability, and relationships with follower outcomes across 15 years. Journal of Business Ethics, 194(2), 455–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashforth, B. E., & Mael, F. (1989). Social identity theory and the organization. Academy of Management Review, 14(1), 20–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avolio, B. J., Walumbwa, F. O., & Weber, T. J. (2009). Leadership: Current theories, research, and future directions. Annual Review of Psychology, 60, 421–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babalola, M. T., Stouten, J., Camps, J., & Euwema, M. (2019). When do ethical leaders become less effective? The moderating role of perceived leader ethical conviction on employee discretionary reactions to ethical leadership. Journal of Business Ethics, 154, 85–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Bass, B. M. (1985). Leadership and performance beyond expectations. Free Press Collier Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, T. E., Billings, R. S., Eveleth, D. M., & Gilbert, N. L. (1996). Focus and bases of employee commitment: Implications for job performance. Academy of Management Journal, 39(2), 464–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M. E., & Treviño, L. K. (2006). Ethical leadership: A review and future direction. The Leadership Quarterly, 17, 595–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M. E., Treviño, L. K., & Harrison, D. A. (2005). Ethical leadership: A social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 97(2), 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drucker, P. F. (1999). Knowledge-worker productivity: The biggest challenge. California Management Review, 41(2), 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelbrecht, A. S., Heine, G., & Mahembe, B. (2017). Integrity, ethical leadership, trust and work engagement. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 38(3), 368–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H., Zhu, W., & Zheng, X. (2014). Procedural justice and employee engagement: Roles of organizational identification and moral identity centrality. Journal of Business Ethics, 122, 681–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houston, L. (2021, February 17). Ethical leadership study 2. Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research [Distributor]. Available online: https://www.openicpsr.org/openicpsr/project/132621/version/V1/view;jsessionid=03829561AD8CF3E093DC0859A247B3D1 (accessed on 10 July 2024).

- Houston, L., Ferris, D. L., & Crossley, C. (2024). Does value similarity matter? Influence of ethical leadership on employee engagement and deviance. Group & Organization Management, 49(4), 943–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, W. A. (1990). Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Academy of Management Journal, 33(4), 692–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalra, A., Singh, R., Badrinarayanan, V., & Gupta, A. (2025). How ethical leadership and ethical self-leadership enhance the effects of idiosyncratic deals on salesperson work engagement and performance. Journal of Business Ethics, 196, 169–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalshoven, K., Hartog, D. N. D., & De Hoogh, A. H. B. (2011). Ethical leader behavior and big five factors of personality. Journal of Business Ethics, 100(2), 349–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristof-Brown, A. L., Zimmerman, R. D., & Johnson, E. C. (2005). Consequences of individuals’ fit at work: A meta-analysis of person–job, person–organization, person–group, and person–supervisor fit. Personnel Psychology, 58(2), 281–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legood, A., van der Werff, L., Lee, A., & Den Hartog, D. (2020). A meta-analysis of the role of trust in the leadership-performance relationship. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 30(1), 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mael, F., & Ashforth, B. E. (1992). Alumni and their alma mater: A partial test of the reformulated model of organizational identification. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 13(2), 103–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markos, S., & Sridevi, M. S. (2010). Employee engagement: The key to improving performance. International Journal of Business and Management, 5(12), 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, D. M., Kuenzi, M., Greenbaum, R. L., Bardes, M., & Salvador, R. B. (2009). How low does ethical leadership flow? Test of a trickle-down model. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 108(1), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meglino, B. M., Ravlin, E. C., & Adkins, C. L. (1989). A work values approach to corporate culture: A field test of the value congruence process and its relationship to individual outcomes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 74(3), 424–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Men, L. R. (2015). The role of ethical leadership in internal communication: Influences on communication symmetry, leader credibility, and employee engagement. Public Relations Review, 41(5), 610–624. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, T. R., & James, L. R. (2001). Building better theory: Time and the specification of when things happen. Academy of Management Review, 26(4), 530–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neubert, M. J., Carlson, D. S., Kacmar, K. M., Roberts, J. A., & Chonko, L. B. (2009). The virtuous influence of ethical leadership behavior: Evidence from the field. Journal of Business Ethics, 90, 157–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, T. W. H., & Feldman, D. C. (2015). Ethical leadership: Meta-analytics evidence of criterion-related and incremental validity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(3), 948–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resick, C. J., Hanges, P. J., Dickson, M. W., & Mitchelson, J. K. (2006). A cross-cultural examination of the endorsement of ethical leadership. Journal of Business Ethics, 63, 345–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rich, B. L., Lepine, J. A., & Crawford, E. R. (2010). Job engagement: Antecedents and effects on job performance. Academy of Management Journal, 53(3), 617–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Torner, C., González-Carrasco, M., & Miranda Ayala, R. A. (2024). Ethical leadership and emotional exhaustion: The impact of moral intensity and affective commitment. Administrative Sciences, 14(9), 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sluss, D. M., & Ashforth, B. E. (2007). Relational identity and identification: Defining ourselves through work relationships. Academy of Management Review, 32(1), 9–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sluss, D. M., & Ashforth, B. E. (2008). How relational and organizational identification converge: Processes and conditions. Organization Science, 19(6), 807–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treviño, L. K., Brown, M. E., & Hartman, L. P. (2003). A qualitative investigation of perceived executive ethical leadership: Perceptions from inside and outside the executive suite. Human Relations, 56(1), 5–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Gils, S., Van Quaquebeke, N., van Knippenberg, D., van Dijke, M., & De Cremer, D. (2015). Ethical leadership and follower organizational deviance: The moderating role of follower moral attentiveness. The Leadership Quarterly, 26(2), 190–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walumbwa, F. O., Mayer, D. M., Wang, P., Wang, H., Workman, K., & Christensen, A. L. (2011). Linking ethical leadership to employee performance: The roles of leader–member exchange, self-efficacy, and organizational identification. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 115(2), 204–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wibawa, W. M. S., & Takahashi, Y. (2021). The effect of ethical leadership on work engagement and workaholism: Examining self-efficacy as a moderator. Administrative Sciences, 11(2), 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z., Wang, M., & Shi, J. (2012). Leader–follower congruence in proactive personality and work outcomes: The mediating role of leader–member exchange. Academy of Management Journal, 55(1), 111–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).