Equine-Assisted Experiential Learning: A Literature Review of Embodied Leadership Development in Organizational Behavior

Abstract

1. Significance of the Research

2. Literature Review

2.1. Difference Between Leader Development and Leadership Development

2.2. Leadership Development Programs

2.3. Traditional vs. Experiential Approaches

2.4. The Rise of Embodied Leadership Practices

2.5. Leadership as Identity Work and Transformation

2.6. The Role of Nature and Environment in Leadership Learning

2.7. Equine-Assisted Leadership Development (EALD)

2.8. Equine-Assisted Programs as Experiential Learning

- Equine-Facilitated Psychotherapy (EFP) is a therapeutic tool helping people to develop positive behavioral and emotional well-being. Horses, as (Brandt, 2013) points out, help to develop mutual trust, affection, tenacity, firmness, and responsibility, which, when combined with traditional psychotherapeutic techniques, offer a unique improvement in the therapeutic process. The Equine-Assisted Growth and Learning Association (EAGALA) describes the differences between EAP and EAL as shown in Table 1. EAT sessions—EFP, EAP, and EFL—show the mirroring phenomenon (Sheena, 2020). Equine-assisted therapy uses a trust-building strategy in which the horse acts as a “communication arbitrator” to help the rehabilitant, the horse, and the psychotherapist build a trust bond (Burgon, 2011).

- Equine-assisted learning (EAL) lets people interact with horses to improve their learning and developmental process.

- Therapeutic Horseback Riding (THR) is riding horses to encourage relaxation and improve coordination, muscular strength, self-confidence, and general well-being for people with disabilities. This type of therapy aims to provide these therapeutic effects by means of the rider’s body’s rhythmic movement, which mimics the motion of human gait (Weiss-Dagan et al., 2022).

- Hippotherapy is a therapeutic intervention in the domains of speech and occupational therapy. Hippotherapy uses the particular movements of horses to improve the motor skills and sensory processing of people under treatment. Trained physical therapists, certified occupational therapists, or speech pathologists administer this kind of therapy (Ahmed et al., 2023).

2.9. Equine-Assisted Learning (EAL)

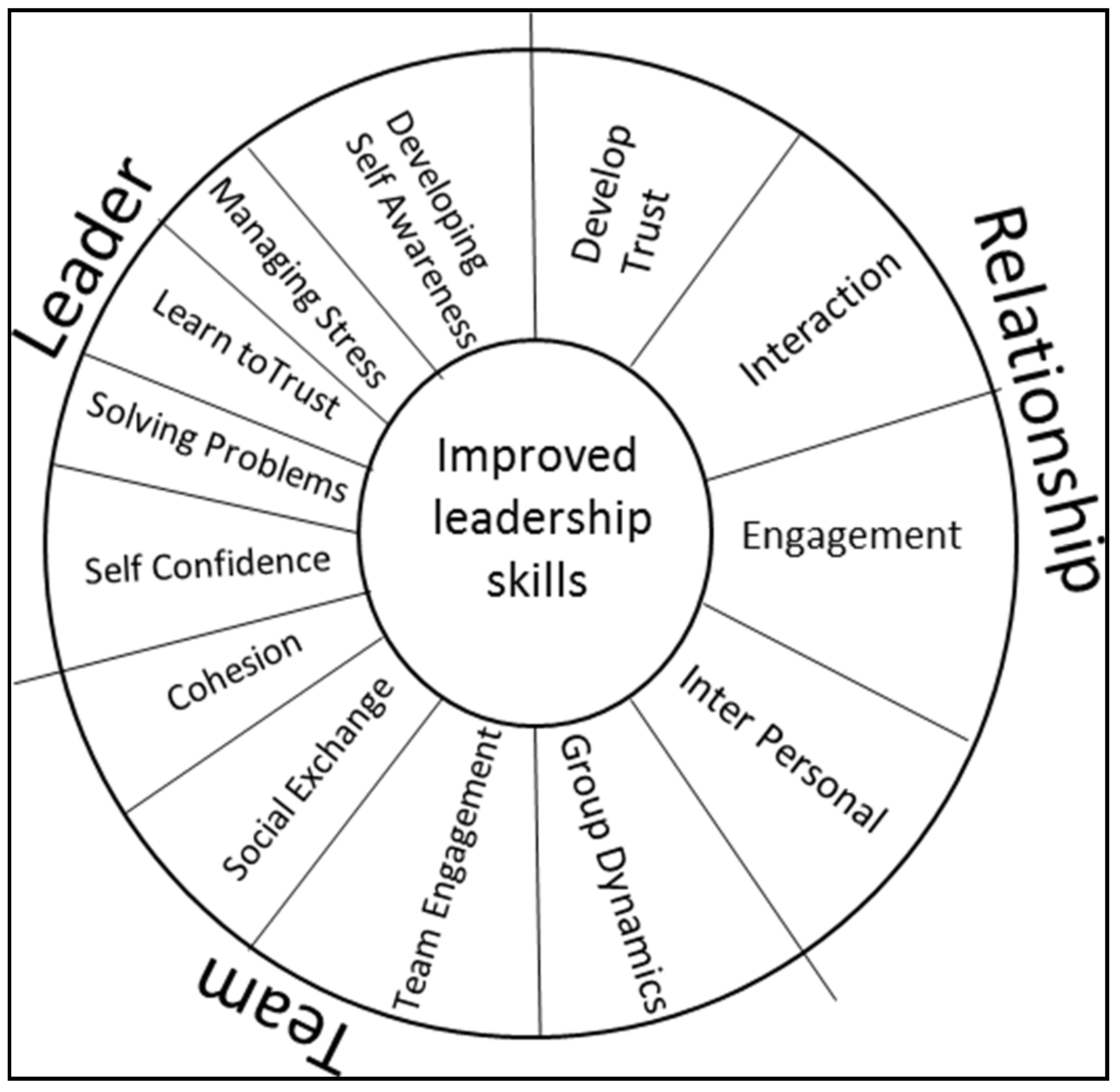

2.10. Leadership Skills and Their Alignment with Equine-Assisted Learning

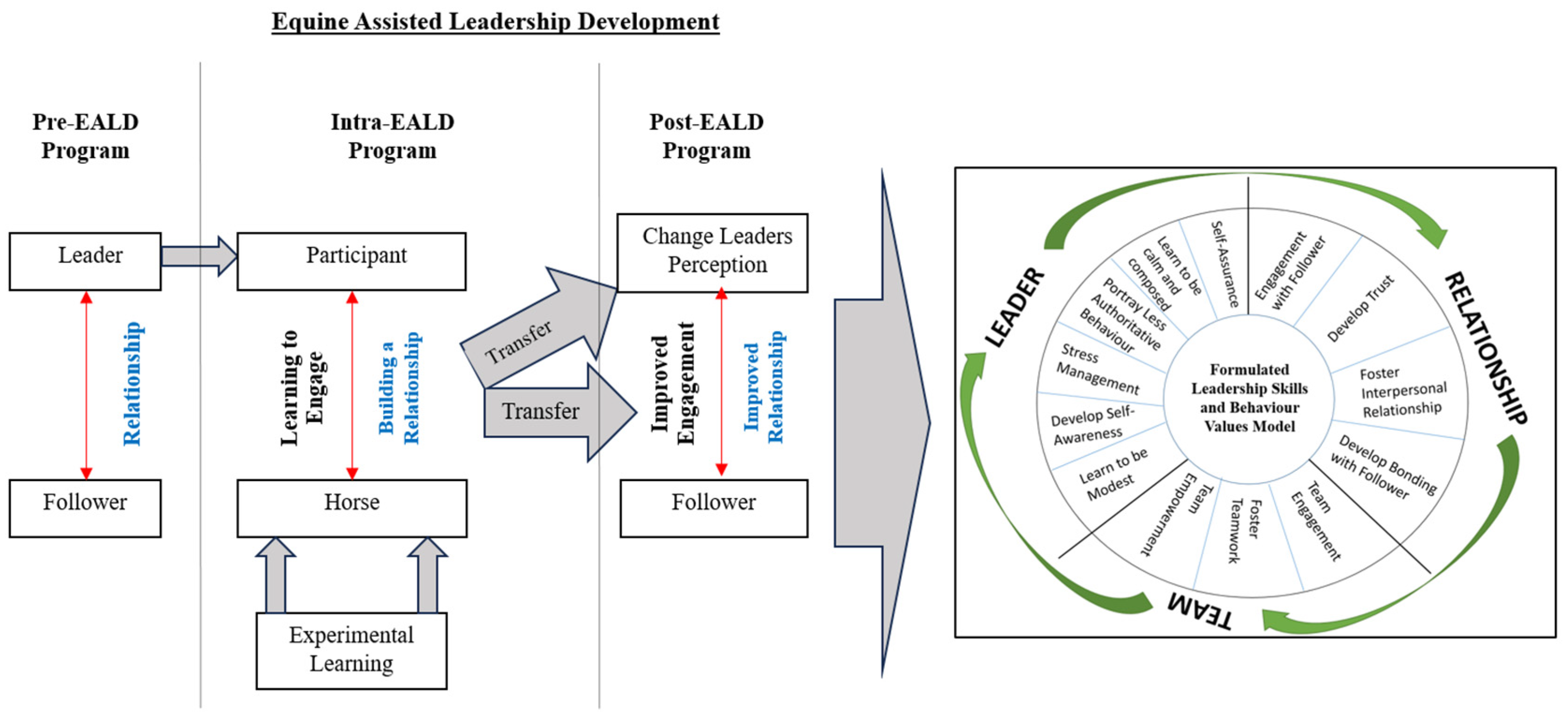

2.11. Equine-Assisted Experiential Learning Process Flow

2.12. Development of Leadership Skills Through Equine-Assisted Learning

- The leader cultivated self-awareness when engaging with horses (Almeras & Bresciani, 2023; Elif, 2021; Stock & Kolb, 2016).

- The leader learned how to handle stress and challenging situations (Earles et al., 2015; Gehrke et al., 2018; Jung et al., 2022).

- The leader acquired the ability to place trust in others (Burgon, 2011; Keaveney, 2008; Williams, 2021).

- The leader acquired the ability to address and resolve issues (Stock & Kolb, 2016; Koris et al., 2017).

- The leader observed a rise in their self-confidence (Fridén et al., 2022; Geddes, 2010; Punzo et al., 2022; Souilm, 2023).

- The leader acquired the ability to establish a trusting relationship with their followers, colleagues, and superiors (Burgon, 2011).

- The leader acquired the ability to engage effectively with peers, resulting in enhanced social relationships (Merkies & Franzin, 2021; Stock & Kolb, 2016).

- The leader acquired the skills necessary to effectively interact with their followers (Fransson, 2015; Gunter et al., 2017; Stock & Kolb, 2016).

- The leader gained important interpersonal skills needed to build productive and efficient interactions (Cartinella, 2009; Jaafar et al., 2023; Serot Almeras & Bresciani, 2021).

- With the horse’s aid, the leader became more adept at social interactions (Cartinella, 2009; Pelyva et al., 2020; Koris et al., 2017).

- The leader acquired the necessary skills to comprehend the dynamics within a group (Fransson, 2015).

- The leader acquired the skills necessary to enhance the unity and solidarity within the group (Berg & Causey, 2014; Carey, 2016).

3. Conclusions

4. Limitations and Further Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahmed, F., Al Zubayer, M. A., Akter, S., Yeasmin, M. H., Nazmul Hasan, M., Mawa, Z., & Islam, A. (2023). Physical effects of hippotherapy on balance and gross motor function of a child with cerebral palsy. Archives of Clinical and Medical Case Reports, 7(2), 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeras, H. S., & Bresciani, S. (2023). Experiential learning with horses for leadership and communication skills development: Toward a model. International Journal of Learning and Change, 16(1), 86–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashkanasy, N. M., & Humphrey, R. H. (2011). Current emotion research in organizational behavior. Emotion Review, 3(2), 214–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayala, M. D., Carrillo, A., Iniesta, P., & Ferrer, P. (2021). Pilot study of the influence of equine assisted therapy on physiological and behavioral parameters related to welfare of horses and patients. Animals, 11(12), 3527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benmira, S., & Agboola, M. (2021). Evolution of leadership theory. BMJ Leader, 5(1), 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, E. L., & Causey, A. (2014). The life-changing power of the horse: Equine-assisted activities and therapies in the U.S. Animal Frontiers, 4(3), 72–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohari, A., Wider, W., Udang, L. N., Jiang, L., Tanucan, J. C. M., & Lajuma, S. (2024). Transformational leadership’s role in shaping Education 4.0 within higher education. Journal of Infrastructure, Policy and Development, 8(8), 4900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, C. (2013). Equine-facilitated psychotherapy as a complementary treatment intervention. Practitioner Scholar: Journal of Counseling & Professional Psychology, 2(1), 23–42. Available online: http://libpublic3.library.isu.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=92621824&site=ehost-live (accessed on 13 June 2024).

- Braun, M. N., Müller-Klein, A., Sopp, M. R., Michael, T., Link-Dorner, U., & Lass-Hennemann, J. (2024). The human ability to interpret affective states in horses’ body language: The role of emotion recognition ability and previous experience with horses. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 271, 106171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgon, H. L. (2011). ‘Queen of the world’: Experiences of ‘at-risk’ young people participating in equine-assisted learning/therapy. Journal of Social Work Practice, 25, 165–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, J. (2016). Exploring the impact of equine facilitated learning on the social and emotional well-being of young people affected by educational inequality. Available online: https://doras.dcu.ie/21394/1/Jill_Carey_Thesis_8_september_2016_SUBMITTED.pdf (accessed on 13 June 2024).

- Cartinella, J. E. (2009). Social skills improvement for an adolescent engaged in equine assisted therapy: A single subject study [Doctoral dissertation, Pacific University]. [Google Scholar]

- Chandolia, E., & Anastasiou, S. (2020). Leadership and conflict management style are associated with the effectiveness of school conflict management in the region of epirus, NW Greece. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 10(1), 455–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H., Fei-Xue, R., & Ma, L. (2024). On the modern horseback archery and the awakening of Chinese national consciousness (1921–1949). Cogent Arts & Humanities, 11(1), 2335759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalakoura, A. (2010). Examining the effects of leadership development on firm performance. Journal of Leadership Studies, 4(1), 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damasio, A. R. (1994). Descartes’ error: Emotion, reason, and the human brain. Putnam. [Google Scholar]

- Day, D. V. (2000). Leadership development: A review in context. The Leadership Quarterly, 11(4), 581–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, D. V., Riggio, R. E., Tan, S. J., & Conger, J. A. (2021). Advancing the science of 21st-century leadership development: Theory, research, and practice. The Leadership Quarterly, 32(5), 101557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EAGALA. (2011). Setting global standards for equine therapy. Equine assisted growth & learning association. Available online: https://www.eagala.org/wp-content/uploads/Eagala_-Basic-Guide-to-Conducting-Research.pdf (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Earles, J. L., Vernon, L. L., & Yetz, J. P. (2015). Equine-assisted therapy for anxiety and posttraumatic stress symptoms. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 28(2), 149–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elif, B. (2021). Equine-assisted experiential learning on leadership development. International Journal of Organizational Leadership, 10, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fages, A., Hanghøj, K., Khan, N., Gaunitz, C., Seguin-Orlando, A., Leonardi, M., McCrory Constantz, C., Gamba, C., Al-Rasheid, K. A. S., Albizuri, S., Alfarhan, A. H., Allentoft, M., Alquraishi, S., Anthony, D., Baimukhanov, N., Barrett, J. H., Bayarsaikhan, J., Benecke, N., Bernáldez-Sánchez, E., … Orlando, L. (2019). Tracking five millennia of horse management with extensive ancient genome time series. Cell, 177(6), 1419–1435.e31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fijn, N. (2021). Human-horse sensory engagement through horse archery. The Australian Journal of Anthropology, 32(S1), 58–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, K., & Robbins, C. R. (2014). Embodied leadership: Moving from leader competencies to leaderful practices. Leadership, 11(3), 281–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, V., Kennedy, M., & Marlin, D. (2012). A comparison of the Monty Roberts technique with a conventional UK technique for initial training of riding horses. Anthrozoös, 25(3), 301–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fransson, J. (2015). Leadership skills developed through horse experiences and their usefulness for business leaders. Available online: https://stud.epsilon.slu.se/8544/1/Fransson_J_151007.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- Fridén, L., Hultsjö, S., Lydell, M., & Jormfeldt, H. (2022). Relatives’ experiences of an equine-assisted intervention for people with psychotic disorders. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 17(1), 2087276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galantino, M. L., Tiger, R., Brooks, J., Jang, S., & Wilson, K. (2019). Impact of somatic yoga and meditation on fall risk, function, and quality of life for chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy syndrome in cancer survivors. Integrative Cancer Therapies, 18, 1534735419850627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geddes, J. (2010). Self-efficacy and equine assisted therapy: A single subject study [Doctoral dissertation, Pacific University]. Available online: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/48848285.pdf (accessed on 18 May 2024).

- Gehrke, E. K. (2020). Developing coherent leadership in partnership with horses—A new approach to leadership training. Available online: http://www.mindfulhorsemindfulleader.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/Developing-Coherent-Leadership-In-Partnership-With-Horses-_-A-New-Approach.pdf (accessed on 22 April 2024).

- Gehrke, E. K., Noquez, A. E., Ranke, P. L., & Myers, M. P. (2018). Measuring the psychophysiological changes in combat Veterans participating in an equine therapy program. Journal of Military, Veteran and Family Health, 4(1), 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemeda, H. K., & Lee, J. (2020). Leadership styles, work engagement and outcomes among information and communications technology professionals: A cross-national study. Heliyon, 6(4), e03699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guinnefollau, L., Gee, E., Norman, E., Rogers, C., & Bolwell, C. (2020). Horses used for educational purposes in New Zealand: A descriptive analysis of their use for teaching. Animals, 10, 1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunter, J., Berardinelli, P., Blakeney, B., Cronenwett, L., & Gurvis, J. (2017). Working with horses to develop shared leadership skills for nursing executives. Organizational Dynamics, 46(1), 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoggan, C., & Hoggan-Kloubert, T. (2022). Critiques and evolutions of transformative learning theory. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 41(6), 666–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, Q., Ahmad, N. H., & Halim, H. A. (2020). How does sustainable leadership influence sustainable performance? Empirical evidence from selected ASEAN countries. Sage Open, 10(4), 2158244020969394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isham, A., Jefferies, L., Blackburn, J., Fisher, Z., & Kemp, A. H. (2025). Green healing: Ecotherapy as a transformative model of health and social care. Current Opinion in Psychology, 62, 102005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaafar, R., Mokri, S. S., Arsad, N., & Aziz, N. A. (2023). Using equine assisted learning to boost character skills and academic achievement among university students. ASEAN Journal of Teaching & Learning in Higher Education, 15(2), 239–251. [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez, M. P., Deville, N. V., Elliott, E. G., Schiff, J. E., Wilt, G. E., Hart, J. E., & James, P. (2021). Associations between nature exposure and health: A review of the evidence. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(9), 4790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, T., Park, H., Kwon, J. Y., & Sohn, S. (2022). The effect of equine assisted learning on improving stress, health, and coping among quarantine control workers in South Korea. Healthcare, 10(8), 1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keaveney, S. M. (2008). Equines and their human companions. Journal of Business Research, 61(5), 444–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, H., Rehmat, M., Butt, T. H., Farooqi, S., & Asim, J. (2020). Impact of transformational leadership on work performance, burnout and social loafing: A mediation model. Future Business Journal, 6(1), 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjellström, S., Stålne, K., & Törnblom, O. (2020). Six ways of understanding leadership development: An exploration of increasing complexity. Leadership, 16(4), 434–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, D. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. FT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, Y. (2021). The role of experiential learning on students’ motivation and classroom engagement. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 10–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koris, R., Alalauri, H.-M., & Pihlak, Ü. (2017). Learning leadership from horseback riding—More than meets the eye. Development and Learning in Organizations: An International Journal, 31(3), 11–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ljungblom, M. (2022). A comparative study between developmental leadership and lean leadership—Similarities and differencies. Management and Production Engineering Review, 3(4), 54–68. Available online: https://journals.pan.pl/Content/89296/PDF/6-ljungblom.pdf (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Loftus, L., Marks, K., Jones-McVey, R., Gonzales, J. L., & Fowler, V. L. (2016). Monty Roberts’ public demonstrations: Preliminary report on the heart rate and heart rate variability of horses undergoing training during live audience events. Animals, 6(9), 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundqvist, D., Wallo, A., Coetzer, A., & Kock, H. (2022). Leadership and learning at work: A systematic literature review of learning-oriented leadership. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 30(2), 205–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheshwari, S. K. (2022). Leadership development lessons: Contextual enablers within organisations. In H. Gray, A. Gimson, & I. Cunningham (Eds.), Developing leaders for real: Proven approaches that deliver impact (pp. 85–95). Emerald Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCauley, C. D., & Palus, C. J. (2021). Developing the theory and practice of leadership development: A relational view. The Leadership Quarterly, 32(5), 101456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNarry, G., Allen-Collinson, J., & Evans, A. B. (2020). Sensory sociological phenomenology, somatic learning and ‘lived’ temperature in competitive pool swimming. The Sociological Review, 69(1), 206–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkies, K., & Franzin, O. (2021). Enhanced understanding of horse–human interactions to optimize welfare. Animals, 11(5), 1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, G. S., & Reigstad, I. (2023). Strengthening leadership skills through embodied learning in Early Childhood Teacher Education. Nordisk Barnehageforskning, 20(1), 36–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulat, G. W., & Singh, D. P. (2023). The role of developing individual leaders to enhance organizational performance: The human capital perspective. European Journal of Business and Management Research, 8(3), 168–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, P., Chrzanowska, A., & Pisula, W. (2016). A critical comment on the Monty Roberts interpretation of equine behavior. Psychology, 7(4), 480–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oluwayemi, O. B. (2018). Organizational behaviour, management theory and organizational structure: An overview of the inter-relationship. Archives of Business Research, 6(6), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, N. C., Nimon-Peters, A. J., & Urquhart, A. (2020). Big need not be bad: A case study of experiential leadership development in different-sized classes. Journal of Management Education, 45(3), 360–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelyva, I. Z., Kresák, R., Szovák, E., & Tóth, Á. L. (2020). How equine-assisted activities affect the prosocial behavior of adolescents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(8), 2967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrie, N. (2014). Vertical leadership development—Part 1 developing leaders for a complex world. Center for Creative Leadership. Available online: https://www.ccl.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/VerticalLeadersPart1.pdf (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Petriglieri, J. L. (2011). Under threat: Response to and the consequences of threats to individuals’ identities. The Academy of Management Review, 36(4), 641–662. [Google Scholar]

- Pillay, M. (2021, July 16–18). Determining relationship between effective leadership and self-awareness among managers in South Africa. 4th International Conference on Advanced Research in Business, Management & Economics (pp. 27–38), Amsterdam, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punzo, K., Skoglund, M., Carlsson, I. M., & Jormfeldt, H. (2022). Experiences of an equine-assisted therapy intervention among children and adolescents with mental illness in Sweden—A nursing perspective. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 43(12), 1080–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuille-Dupont, S. (2021). Applications of somatic psychology: Movement and body experience in the treatment of dissociative disorders. Body, Movement and Dance in Psychotherapy, 16(2), 105–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, M. (1997). The man who listens to horses: The story of a real-life horse whisperer. Random House. [Google Scholar]

- Rueff, M., & Reese, G. (2023). Depression and anxiety: A systematic review on comparing ecotherapy with cognitive behavioral therapy. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 90, 102097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samoka, K., Oginde, D., & Kiambi, D. (2023). Leadership training of young professionals for organizational performance in the building industry in Kenya. Strategic Journal of Business & Change Management, 10(1), 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scopa, C., Greco, A., Contalbrigo, L., Fratini, E., Lanatà, A., Scilingo, E. P., & Baragli, P. (2020). Inside the interaction: Contact with familiar humans modulates heart rate variability in horses. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 7, 582759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serot Almeras, H., & Bresciani, S. (2021). Equine facilitated learning for enhancing leadership and communication skills. Academy of Management Proceedings, 2021(1), 12372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheena, T. S. (2020). Equine-facilitated psychotherapy: Harnessing the healing power of horses and neurobiology in treating adolescents. Pacifica Graduate Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair, A. (2009). Seducing leadership: Stories of leadership development. Gender, Work & Organization, 16(2), 266–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivagurunathan, R., Rahman, A., Senathirajah, B. S., Ramasamy, G., Isa, M., Haque, R., Yang, C., & Sivagurunathan, L. (2024a). A study on development of educational leadership program using equine assisted experiential learning. Eurasian Journal of Educational Research, 112, 1–14. Available online: https://ejer.com.tr/manuscript/index.php/journal/article/view/1814/467 (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Sivagurunathan, R., Rahman, A., Senathirajah, B. S., Ramasamy, G., Isa, M., Haque, R., Yang, C., & Sivagurunathan, L. (2024b). Facilitating leadership skills and behavioural values in workplace: A case of equine assisted leadership development programs. International Journal of Instructional Cases, 8(1), 330–343. [Google Scholar]

- Souilm, N. (2023). Equine-assisted therapy effectiveness in improving emotion regulation, self-efficacy, and perceived self-esteem of patients suffering from substance use disorders. BMC Complementary Medicine and Therapies, 23(1), 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stock, K. L., & Kolb, D. A. (2016). Equine-assisted experiential learning. Organization Development Practitioner, 48(2), 43–47. Available online: https://learningfromexperience.com/downloads/research-library/equine-assisted-experiential-learning.pdf (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Strozzi-Heckler, R. (2014). The art of somatic coaching: Embodying skillful action, wisdom, and compassion. North Atlantic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Trösch, M., Cuzol, F., Parias, C., Calandreau, L., Nowak, R., & Lansade, L. (2019). Horses categorize human emotions cross-modally based on facial expression and non-verbal vocalizations. Animals, 9(11), 862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trzmiel, T., Purandare, B., Michalak, M., Zasadzka, E., & Pawlaczyk, M. (2019). Equine assisted activities and therapies in children with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review and a meta-analysis. Complementary Therapies in Medicine, 42, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsyganenko, M. V. (2014). The effect of a leadership development program on behavioral and financial outcomes: Kazakhstani experience. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 124, 486–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turchin, P., Currie, T. E., & Turner, E. A. L. (2016). Mapping the spread of mounted warfare. Cliodynamics: The Journal of Quantitative History and Cultural Evolution, 7(2), 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, V. (1969). The ritual process structure and anti-structure (1st ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Uhl-Bien, M., & Arena, M. (2017). Complexity leadership: Enabling people and organizations for adaptability. Organizational Dynamics, 46(1), 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasudevan, A., Salim, I., Mohammad, S. I., Wenchang, C., Krishnasamy, H. N., Parahakaran, S., Al-Adwan, A. S., & Alshurideh, M. T. (2025). Sustainable leadership and employee performance: The role of organizational culture in Malaysia’s information science sector. Applied Mathematics and Information Sciences, 19(1), 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waite, R., McKinney, N., Smith-Glasgow, M. E., & Meloy, F. A. (2014). The embodiment of authentic leadership. Journal of Professional Nursing, 30(4), 282–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss-Dagan, S., Naim-Levi, N., & Brafman, D. (2022). Therapeutic horseback riding for at-risk adolescents in residential care. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 16(1), 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whetten, D. A., & Cameron, K. (2011). Developing managment skills. Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, H. P. (2021). Horses preparing superintendent candidates for the leadership arena. Journal of Experiential Education, 44(1), 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zargar, F., Rahafrouz, L., & Tarrahi, M. J. (2021). Effect of mindfulness-based stress reduction program on psychological symptoms, quality of life, and symptom severity in patients with somatic symptom disorder. Advanced Biomedical Research, 10(1), 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Equine-Assisted Psychotherapy (EAP) | Equine-Assisted Learning (EAL) |

|---|---|

| Focuses on the treatment objectives of the client or group. | Focuses on to the learning or educational objectives of an individual or a group. |

| The emphasis is on establishing foundational horse-related activities that necessitate the client or group to utilize specific skills outlined in their treatment plan or objectives. | The emphasis is on establishing equestrian-based ground activities aimed at acquiring particular skills or attaining educational objectives, as determined by the individual or group involved. |

| Examples: Enhanced conduct and interpersonal abilities, decreased levels of depression and anxiety, and the fostering of relationships. | Examples: Enhanced company revenue through increased product sales, developed leadership abilities within an organization, and provided resiliency training for military personnel. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sivagurunathan, R.; S Senathirajah, A.R.b.; Sivagurunathan, L.; Qazi, S.; Haque, R. Equine-Assisted Experiential Learning: A Literature Review of Embodied Leadership Development in Organizational Behavior. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 298. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15080298

Sivagurunathan R, S Senathirajah ARb, Sivagurunathan L, Qazi S, Haque R. Equine-Assisted Experiential Learning: A Literature Review of Embodied Leadership Development in Organizational Behavior. Administrative Sciences. 2025; 15(8):298. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15080298

Chicago/Turabian StyleSivagurunathan, Rubentheran, Abdul Rahman bin S Senathirajah, Linkesvaran Sivagurunathan, Sayeeduzzafar Qazi, and Rasheedul Haque. 2025. "Equine-Assisted Experiential Learning: A Literature Review of Embodied Leadership Development in Organizational Behavior" Administrative Sciences 15, no. 8: 298. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15080298

APA StyleSivagurunathan, R., S Senathirajah, A. R. b., Sivagurunathan, L., Qazi, S., & Haque, R. (2025). Equine-Assisted Experiential Learning: A Literature Review of Embodied Leadership Development in Organizational Behavior. Administrative Sciences, 15(8), 298. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15080298