Abstract

Entrepreneurial intention research requires further examination of systemic relationships between constructs of comprehensive models that will more closely approximate the ontological realities of individuals. This research jointly examines relationships among basic individual values and constructs from the theory of planned behavior, entrepreneurial orientation, and entrepreneurial intention while accounting for multiple contextual factors. Situational factors are accounted for by random determination of mediators, examination of 23 model configurations, and use of quasi-random samples (e.g., respondents with different demographic factors from different organizations, industries, and regions) from two culturally and economically contrasting countries, the United States and India. Models were analyzed using PLS-SEM. Contrary to the “common view”—the idea that Western countries are individualistic and Asian and Latin American countries are collectivistic—individual personal focus values and passion relationships were stronger for India’s sample than for the United States. Contrary results were found for basic individual social focus values and subjective norms relationships. Results show a lack of stark disparities between the two country samples. Hence, it seems that between-country differences have been overemphasized, while more attention to context and to within-country variability is required. This study expands the entrepreneurial orientation nomological network by jointly considering basic individual values and TPB’s and EO’s constructs anteceding entrepreneurial intention and examining a large set of model configurations while accounting for multiple situational factors in two culturally and economically contrasting countries.

1. Introduction

Entrepreneurial activities play a crucial role in driving economic growth, fostering job creation, promoting innovation, and improving the socio-economic conditions of both individuals and societies (Audretsch & Moog, 2022). Fundamental to this discussion is the concept of entrepreneurial intention (EI), encompassing the willingness to initiate, innovate, and manage a business. A complex interplay of many factors, including societal influences, dominant narratives, values, institutions, and everyday experiences, shapes entrepreneurial inclination by influencing individuals’ perceptions, motivations (Carraher et al., 2010), expectations, cognitions, and actions (Bourdieu, 1998; Kahneman & Tversky, 2013). Among these factors, values are critical determinants, shaping individuals’ mindsets and behaviors and influencing their inclination toward entrepreneurial activities (Gorgievski et al., 2018; Schwartz, 1992). Likewise, context entails different hierarchies of values (Schwartz et al., 2012). Additionally, key explanatory constructs for understanding EI are provided by the theory of planned behavior (TPB): attitudes toward entrepreneurship, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control (Ajzen, 1991), and entrepreneurial orientation (EO): innovativeness, risk-taking, proactiveness, perseverance, and passion (Covin & Lumpkin, 2011).

Most studies examine only specific influences among particular basic individual values and or different components of TPB or EO on entrepreneurial intention and often use simplified models, thereby neglecting crucial construct relationships (Gorgievski et al., 2018; Kruse et al., 2019). Hence, simplistic models can lead to erroneous conclusions (Takano & Osaka, 1999). To address this shortcoming, the integration of theories and scientific fields has been called for (Steers et al., 2004). In this regard, (Bagozzi, 1992) noted that TPB may need to account for intentions more adequately. Hence, furthering entrepreneurial intention understanding and producing more realistic, practical findings require more complicated models (e.g., adding constructs to existing models or examining new models).

Different starting points and evolutions may produce differences among organizations, industries, regions, and countries. Furthermore, variations in the number and type of relationships studied may contribute to research findings’ variability. Likewise, constructs may function, depending on the research question, as antecedents, mediators, moderators, or outcomes, potentially producing inconsistent results between diverse subsets of relationships (Anderson et al., 2022; Bae et al., 2014). Contextual factors, such as economic, cultural, regional, and organizational influences, may also impact the relationships between basic individual values, TPB, EO, and entrepreneurial intention (Ahadi & Kasraie, 2020). Thus, examining data from diverse organizations, states, regions, and countries and using multiple sets of plausible models may increase understanding of EI and produce more realistic findings.

This study pursues a twofold objective. Firstly, it aims to jointly examine relationships among basic individual values, TPB constructs, EO constructs, and entrepreneurial intention. This comprehensive approach expands the scope of previous research and models’ explanatory power by jointly considering a large and diverse set of construct relationships. For example, EO adds cognition, commitment, emotions, and effort elements in addition to TPB’s shared social meaning and perspective-taking (Bagozzi, 1992). Secondly, this study accounts for contextual factors by (a) minimizing the effects of some confounding variables through random determination of mediators, (b) examining 23 model configurations, (c) using quasi-random samples (e.g., respondents with different demographic factors from different organizations, industries, and regions), and (d) using samples from two culturally and economically contrasting countries, the United States and India.

This study makes four contributions. First, it examines different model configurations among the set of 19 basic individual values grouped into personal and social focus values proposed by (Schwartz et al., 2012): the three constructs of the theory of planned behavior (Ajzen, 1991), five entrepreneurial orientation’s constructs (Covin & Lumpkin, 2011), and entrepreneurial intention (Liñán & Chen, 2009). Thus, the different perspectives examined originate from two sources: (1) diverse plausible construct sets originating from the joint considerations of basic personal values and TPB and EO constructs and (2) the diversity of model configurations between and within each of the three-model series researched (see Method). Although research has investigated several relationships between basic individual values, TPB constructs, or EO dimensions as anteceding EI (Kruse et al., 2019; Schwartz et al., 2012; Awang et al., 2016; Covin & Lumpkin, 2011; Newman et al., 2021), a comprehensive model that integrates all three as antecedents remains largely unexamined. This large and varied set of model relationships expands the EI antecedents’ boundary conditions previously examined, thereby increasing model explanatory power and understanding of entrepreneurial intention. Second, partly adjusting for contextual factors, the large set of models examined, the random assignment of mediators, and the use of quasi-random samples, in two sharply different countries, generate more realistic results that contribute to closing the gap between theory and practice. Third, not infrequently, entrepreneurship studies focus on personal values; this research examines both personal and social focus values. Fourth, results showing mixed influences of the entrepreneurial intention’s antecedents examined suggest that caution shall be exercised in generalizing within countries.

Subsequent sections delve into the literature review and hypotheses, methodology, results, discussion, limitations, and suggestions for future research.

2. Literature Synthesis and Hypotheses

The theoretical underpinnings of entrepreneurial intention draw from various perspectives, including the resource-based view (Barney, 1991), institutional theory (Scott, 1987), the theory of action (Bourdieu, 1998), distal proximate theory (Kirk & Brown, 2003), complexity theory (Damanpour, 1996), the theory of planned behavior (Ajzen, 1991), expectancy–value theory (Wabba & House, 1974), prospect theory (Kahneman & Tversky, 2013), Bird’s model (Bird & Jelinek, 1989), and the entrepreneurial event model (Krueger, 1993). The overall rationale is that an individual perceives, based on values, attitudes, and dispositions, having access to specific resources (e.g., financial, social, cultural, knowledge, and the ability to spot business opportunities as well as the capabilities to seize such opportunities) in a context (field) shaped by other agents (e.g., degrees of uniqueness and competition) and institutions (e.g., laws, regulations, social norms, and incentives and rewards), which the individual somehow integrates in assessing and determining her/his/their willingness to start, innovate, and/or operate a business based on her/his/their perceived likelihood of success.

Individuals’ entrepreneurial intention, a fundamental precursor of entrepreneurial behavior, is driven by basic individual values (Ruiz-Alba et al., 2021), personal traits (Ruiz-Alba et al., 2021), individuals’ cognitions (Choi & Shepherd, 2004), circumstances (Churchill et al., 1987), and broader environmental factors (Beliaeva et al., 2017; Chatterjee et al., 2024).

Basic individual values may impact attitudes, decision-making (Schwartz, 1992), individuals’ perceptions of societal pressure and expectations (Igwe et al., 2020), and perceptions of behavioral control (Bourdieu, 1998), indicating that the social context deeply intertwines with individual values, thereby impacting entrepreneurial outcomes.

Schwartz et al. (2012) categorize 19 individual values into four groups: self-enhancement, openness-to-change, conservation, and self-transcendence, further grouped into personal focus and social focus values. The former encompasses self-enhancement and openness to change values, and the latter includes conservation and self-transcendence values. Self-enhancement values emphasize the pursuit of individual interests. Openness to change values refers to an individual’s inclination toward embracing novel ideas, concepts, and behaviors. Thus, personal focus on individual values may concern individuals’ financial success, personal achievement, autonomy (Schwartz et al., 2012), and opportunity creation and exploitation (Thompson & Bolton, 2013). Social focus values entail social concerns. Although EI has by and large been researched focusing on personal focus values, values ranging from personal achievement to societal impact play a crucial role in shaping entrepreneurial inclination.

2.1. Relationships Among Constructs of the Theory of Planned Behavior and Entrepreneurial Orientation

TPB and EO constructs may mediate the relationship between individual values and entrepreneurial intention (Gorgievski et al., 2018). Other people’s expectations, such as common beliefs or consensuses (Ajzen, 1991), influence individuals’ behavioral orientation. Individuals’ ways of thinking about entrepreneurship, the feelings they may have about it, and the degree to which entrepreneurial activities may be seen as desirable are influenced by collective beliefs (Thompson & Bolton, 2013). Individual subjective norms (Ajzen, 1991), shaped by basic individual values, may influence an individual’s entrepreneurial proclivity (Thompson & Bolton, 2013). Likewise, facing and successfully overcoming external pressure shapes individuals’ subjective norms (Kwon et al., 2021). In turn, individuals’ perceived behavioral control may affect individual entrepreneurial orientation (Ajzen, 1991; Olarewaju et al., 2023). Likewise, the separate and/or joint influences of attitudes toward entrepreneurship and subjective norms may impact individuals’ perceived behavioral control (Ferreira et al., 2012). Risk-taking (Zahra, 2005), innovativeness (Mueller & Thomas, 2001), proactiveness (Kreiser et al., 2010; Shin & Kim, 2015), perseverance (Hoang & Gimeno, 2010), and passion (Newman et al., 2021) have been positively associated with attitudes towards entrepreneurship. Similarly, risk-taking (Quintal et al., 2010), innovativeness (Zellweger et al., 2011), proactiveness (Awang et al., 2016), perseverance (Etcheverry et al., 2008), and passion (Thorgren et al., 2014) positively associate with subjective norms. Likewise, risk-taking (Quintal et al., 2010), innovativeness (Zellweger et al., 2011), proactiveness (Cop et al., 2020), perseverance (Ajzen, 1991), and passion (Karimi, 2020) are positively associated with perceived behavioral control.

2.2. Relationships Between Entrepreneurial Orientation and Entrepreneurial Intention Constructs

EO positively influences entrepreneurial intention (Santos et al., 2020). Likewise, risk-takers have a strong entrepreneurial intention (Yukongdi & Lopa, 2017). Similarly, entrepreneurs’ desire to create distinctive and differentiated offerings positively influences their entrepreneurial intention (Lumpkin & Dess, 1996).

Strong proactive entrepreneurs are more likely to recognize and seize opportunities (Baron & Ensley, 2006), demonstrate resourcefulness (Chen & Huang, 2009), and implement business plans (Mair & Marti, 2006). Similarly, perseverance (Luthans, 2002) and passion (Al Halbusi et al., 2024; Foo, 2011) positively contribute to entrepreneurial intent.

2.3. Cultural and Economic Contrasts Between the United States and India

Research shows that cultural and economic conditions may influence entrepreneurial intent (Achim et al., 2021; Yin et al., 2021). The United States and India contrast economically and culturally. For example, in 2022, the per capita gross domestic product in the United States was USD 76,399, whereas that for India was USD 2389 (World Bank, 2021). In addition to substantial economic differences, which suggest resource availability differences, these two countries may differ in cultural dimensions. For instance, individualism and uncertainty avoidance scores were 91, 46, 48, and 40 for the United States and India, respectively (Hofstede, 2001). Likewise, the United States had lower scores than India for institutional collectivism (4.20 vs. 4.38), in-group collectivism (4.25 vs. 5.92), and humane orientation (4.17 vs. 4.57) (House et al., 2004; Chhokar, 2008; Hoppe & Bhagat, 2008). It may be noted that the United States and India’s values for uncertainty avoidance and institutional collectivism are contrary to “common” expectations, suggesting a higher degree of variability than commonly assumed. In contrast, the assertiveness (Neelankavil et al., 2000) and competitiveness (World Economic Forum, 2019) of the United States are higher than those of India.

We expect positive relationships among societal systems’ components (e.g., culture, institutions, resource access, opportunities, and rewards) in general and between basic individual values, TPB and EO constituents, and entrepreneurial intention.

Considering the economic and cultural differences between the United States and India, exploring how these variations may interact with basic individual values, TPB and EO constructs, and entrepreneurial intention is essential. The economic disparities and distinct cultural dimensions suggest differential relationships in both countries. Due to differences in the long-term evolution and the current state of countries’ macro-economic environments, we expect stronger synergies among country socio-economic conditions, basic personal values, TPB constructs, and EO constructs on EI in the United States than in India.

Based on the prior discussion and the “common view”—the belief that Western countries are individualistic and Asian and Latin American countries are collectivistic—(Takano & Osaka, 1999), we posit the following:

Hypothesis 1.

In both the United States and India, basic individual personal-focus values have stronger positive relationships with attitudes toward entrepreneurship, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, proactiveness, risk-taking, passion, perseverance, innovativeness, and entrepreneurial intention than those with basic individual social focus values.

Hypothesis 2.

The positive relationships among basic individual personal focus values, basic individual social focus values, attitudes toward entrepreneurship, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, proactiveness, risk-taking, passion, perseverance, innovativeness, and entrepreneurial intention will be stronger for the United States than for India.

Hypotheses 1 and 2 are “higher order” hypotheses encompassing multiple relationships. As shown above, prior research has supported relationships involving two or a few constructs. We test whether such relationships hold in more complicated models in which the total set of relationships is jointly tested.

3. Development of Model

Our methodological approach addresses two objectives. Firstly, it relates basic individual values, both personal and social focused to two of the most widely researched models in entrepreneurship, namely, the theory of planned behavior (TPB) and entrepreneurial orientation (EO), in a diverse set of relationships as antecedents of entrepreneurial intention. All constructs are measured at the individual level and are distinct but interrelated and complementary. Thus, there is conceptual and measurement fit (Blalock, 1979). Similarly, all relationships studied are plausible. The joint consideration of basic personal- and social-focused individual values and TPB and EO constructs as anteceding EI encompassed the examination of 474 relationships per country (United States and India) involving (a) traditionally studied relationships particularly within TPB and EO constructs, (b) relationships less frequently studied like those including basic personal values, and (c) new relationships pertaining to those deriving from the different interplays among the constructs of the three models researched (e.g., basic personal values–TPB–EO). In addition, the total set of constructs examined and the diverse set of model configurations studied included a large number of indirect effects. Secondly, this study seeks to account for a rich set of contexts in terms of diverse sets of direct and indirect effects by (a) randomly assigning mediators in 23 model configurations, (b) using quasi-random samples of respondents from different organizations, industries, and regions from two economically and culturally contrasting countries, and (c) controlling for the effects of age, gender, educational level, marital status, and industry.

The foundational relationship is between basic individual values with entrepreneurial intention as mediated by different configurations of TPB and EO constructs.

Three distinct model configurations are employed across the United States and India to achieve the research objectives.

3.1. Model 1 Series

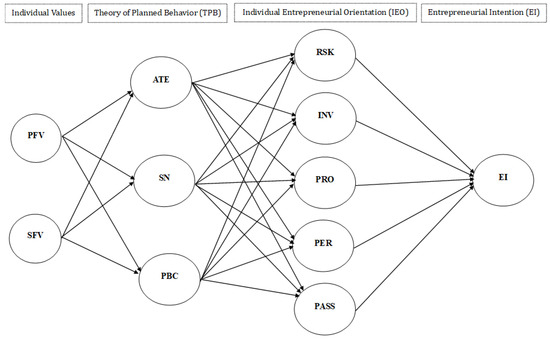

Two models examine the relationships among basic individual values > TPB > EO > entrepreneurial intention sequence (for an example, see Model A in Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Model 1 Series example Model A. Source: the authors. Note: PFV = personal-focused individual values; SFV = social-focused individual values; ATE = attitude towards entrepreneurship; SN = subjective norms; PBC = perceived behavioral control; INV = innovativeness; RSK = risk taking; PRO = proactiveness; PER = perseverance; PASS = passion; EI = entrepreneurial intention; N = 500, N = 511 for the United States and India, respectively.

3.2. Model 2 Series

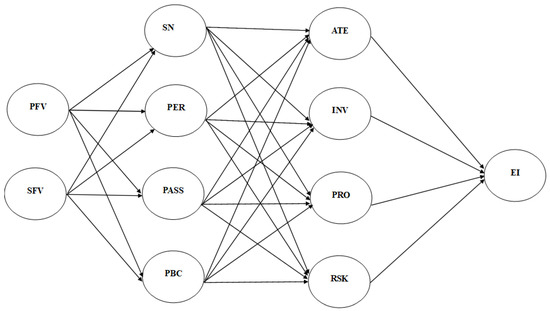

It includes six models of randomly selected relationships among the eight TPB and EO constructs. Figure 2 Model F below shows a model example. These models assume that any relationship between TPB and EO constructs is plausible since different organizations have different starting points and develop differently. Similarly, randomly selected relationships in Models 2 and 3 series assume that a given respondent at a point in time may reflect past (sedimented/internalized direct and indirect effects), present, and future considerations in assigning values to items.

Figure 2.

Model 2 Series example Model F. Source: the authors. Note: PFV = personal-focused individual values; SFV = social-focused individual values; ATE = attitude towards entrepreneurship; SN = subjective norms; PBC = perceived behavioral control; INV = innovativeness; RSK = risk taking; PRO = proactiveness; PER = perseverance; PASS = passion; EI = entrepreneurial intention; N = 500, N = 511 for the United States and India, respectively.

3.3. Model 3 Series

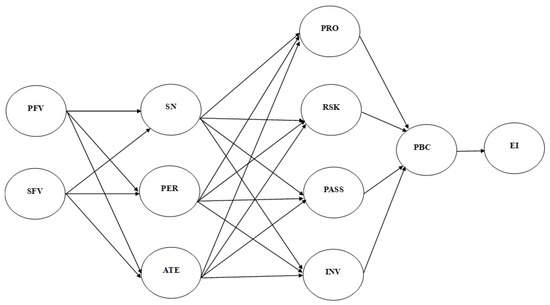

Seeking to further examine the centrality of perceived behavioral control on entrepreneurial intention and drawing from distal proximate theory (Kirk & Brown, 2003) and the theory of action (Bourdieu, 1998), we examine perceived behavioral control as an immediate antecedent of entrepreneurial intention. We use a set of 15 models of randomly selected relationships among a joint set of seven TPB and EO components anteceding perceived behavioral control, which in turn antecedes entrepreneurial intention. Figure 3 Model R below shows a model example.

Figure 3.

Model 3 Series example Model R. Source: the authors. Note: PFV = personal-focused individual values; SFV = social-focused individual values; ATE = attitude towards entrepreneurship; SN = subjective norms; PBC = perceived behavioral control; INV = innovativeness; RSK = risk taking; PRO = proactiveness; PER = perseverance; PASS = passion; EI = entrepreneurial intention; N = 500, N = 511 for the United States and India, respectively.

We run 23 models but due to space limitations, we only provide a selected set of figures and results. Figures and results for the complete set of models studied are available in the Supplementary Materials.

4. Data, Measures, and Method

4.1. Data

Data were obtained from United States and Indian adult workers employing Amazon MTurk platform. Data was collected from 30 May 2023 to 3 June 2023. Respondents were from different organizations, industries, states, and regions in both countries. As a result, the samples are quasi-random. The representativeness of this type of sample may be greater than that drawn from one or a few organizations or from organizations located in only a region or a few regions (Buhrmester et al., 2011; Peer et al., 2014).

Several design measures were implemented to ensure the quality and reliability of the collected data. Firstly, survey items were randomized to minimize response bias. Two attention check questions (e.g., please respond “Strongly disagree”) were strategically inserted to ensure that participants carefully read and consider each item. A minimum average response time of six seconds per item was enforced to guarantee that participants devoted a reasonable effort to comprehend and respond thoughtfully to the survey questions. Furthermore, responses were examined for undesirable patterns. Participants responding with a high frequency of a given number on the scale were discarded.

After necessary “cleaning,” initial samples of 1015 and 1058 resulted in useful samples of 511 and 500 respondents from India and the United States, respectively.

4.2. Measures

Below are definitions of constructs, scales used to measure them, and item examples.

Values. Drawing from Schwartz et al.’s (2012) theory of individual values, we use 19 basic individual values. These values are classified into two higher-order constructs: personal focus individual values and social focus individual values. The former focuses on individual outcomes, while the latter concerns societal elements. The personal focus individual value constructs include self-direction–thought, self-direction–action, stimulation, hedonism, achievement, power–dominance, power–resources, face, and security–personal (Schwartz et al., 2012). The social focus individual value construct includes universalism–tolerance, universalism–nature, universalism–concern, benevolence–dependability, benevolence–caring, humility, conformity–interpersonal, conformity–rules, tradition, and security–societal (Schwartz et al., 2012). To measure each of the 19 values, we used three items. Thus, 57 items Schwartz et al. (2012) developed were used to measure values. Examples of basic individual personal focus values are, “It is important for me to form my views independently,” “I want people to admire my achievements,” and “I avoid anything that might endanger my safety.” Example items of the social focus individual value are, “Having order and stability in society is important to me,” “ It is important to me to maintain traditional values or beliefs,” and “I believe I should always do what people in authority say.” Six items Munir et al. (2019) developed were used to measure attitudes toward entrepreneurship. An example item is, “Being an entrepreneur implies more advantages than disadvantages to me.” Subjective norms are measured by four items developed by Madden et al. (1992). An example item is, “I believe that people think I should pursue a career as an entrepreneur” (Madden et al., 1992). Perceived behavioral control is measured using five items Munir et al. (2019) developed. An example item is, “To start a firm and keep it working would be easy for me” (Munir et al., 2019). Entrepreneurial orientation is measured by five different latent variables: innovation, proactiveness, risk-taking, passion, and perseverance. Innovation is measured by four items developed by Santos et al. (2020). An example item is, “I often like to try new and unusual activities.” Proactiveness is measured by four items developed by Lumpkin and Dess (1996) and Santos et al. (2020). An example item is, “I usually act in anticipation of future problems, needs, or changes.” Risk-taking is measured by four items developed by Santos et al. (2020). An example item is, “I like to venture into the unknown and make risky decisions.” Passion is measured by four items developed by Santos et al. (2020). An example item is, “I have a passion for finding good business opportunities, developing new products or services, exploring business applications, and creating new solutions for existing problems and needs.” Perseverance is measured by five items that Santos et al. (2020) developed. An example item is, “I have achieved goals that took me some time to reach. Entrepreneurial intention is measured with six items from the scale developed by Liñán and Chen (2009). An example item is, “I will make every effort to start and run my own firm.”

Constructs were measured with scales with proven psychometric properties.

4.3. Method

Scores for the 19 values were computed by taking the means of the items corresponding to respective constructs (Schwartz, 1992; Schwartz et al., 2012). The models were analyzed using PLS-SEM. PLS-SEM deals with complex models including a large number of relationships examining direct and mediation effects as well as multiple levels (Schumacker & Lomax, 1996; Hair et al., 2017). Model relationships were adjusted by age, gender, educational level, industry, and marital status. A multi-group analysis was conducted between the Indian and the US samples to assess path coefficient differences. Table 1 shows mean, standard deviation, and correlation between variables.

Table 1.

Construct means, standard deviations, and correlations.

Item loadings were greater than 0.5 (Hair et al., 1998). Construct reliability assessments in both the United States and India yielded acceptable results, with Cronbach’s alpha, reliability rho_a, and composite reliability, for most constructs, equal to or greater than 0.70, their acceptable threshold value (Dijkstra & Henseler, 2015). A few EO constructs had Cronbach’s alpha and reliability rho slightly lower than 0.70. However, Cronbach’s alpha of 0.60 may be acceptable (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994). Furthermore, the three reliability estimates comprehensively support the constructs’ consistency. Cross-loadings were minimal. In addition, the heterotrait–monotrait (HTMT) ratio criterion was used to measure discriminant validity. All HTMT values were below the threshold of 0.90 (Henseler et al., 2015). The Harman test shows that one factor explains 25.11% of the variance, which is below the 50% threshold (Podsakoff et al., 2003).

The design measures taken (e.g., among others, item randomization, attention check questions, item response time, respondents from different organizations, industries, states, regions, and countries) reflected in item loadings and cross-loadings, and constructs’ reliability and validity suggest that all constructs are reliable and valid. While some of the measures followed aimed to minimize common method bias, we acknowledge, in agreement with (Chin et al., 2012; Williams & McGonagle, 2016), that no statistical procedure used ex-post data collection can effectively and accurately identify and disentangle the effects of common method bias, other sources of noise, and omitted variables.

Table 2 shows average path coefficients, average adjusted determination coefficients, average full collinearity VIF, Tenenhaus goodness of fit index, and standardized root mean squared residual (SRMR) for the 23 models studied. All these measures were within the acceptable values/thresholds for all models for the two countries (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Overall, all models are acceptable.

Table 2.

Model fit and quality indices.

5. Results

5.1. Sample Demographics

A total of 55 and 28 percent of United States respondents were between 30 and 39 and 21 and 29 years old, respectively. India’s sample included 34 and 21 percent of respondents between 30 and 39 and 21 and 29 years old. The United States sample comprised 60 percent men and 40 percent women, whereas the Indian respondent group comprised 70 percent men and 30 percent women. Regarding the education level of Indian respondents, 63 percent had a bachelor’s degree, 29 percent had a graduate degree, 2 percent had an associate degree, and 1 percent had some college education but no degree. On the other hand, 82 percent of the United States respondents had a bachelor’s degree, 12 percent had a graduate degree, 2 percent had an associate degree, and 1 percent had a college education but no degree. Indian respondents comprised 84 percent married, 13 percent unmarried, and 3 percent with another marital status. In contrast, in the US, the respondents of married, unmarried, and other marital statuses were 93 percent, 5 percent, and 5 percent, respectively. Furthermore, the United States sample exhibited the highest representation from the education, professional, and scientific services sectors. Conversely, the Indian sample demonstrated the greatest prevalence in the banking and financial services sectors.

5.2. Results Range from Generalizations to Specific Outcomes

Model 1 Series. TPB and EO’s constructs as mediators of the basic individual values–entrepreneurial intention relationship.

Table 3 presents the path coefficients, 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals, effect sizes, and total effects for Model A. Model B results are not shown here but will be provided upon request.

Table 3.

Model 1 Series (Model A) path coefficients, confidence intervals (C.I.), effect size, and total effects.

Most path coefficients were highly significant. Unexpectedly, most path coefficients of personal focus values’ relationships were stronger for India than for the United States sample. Also, unexpectedly, path coefficients of social focus values’ relationships were stronger for the United States than for India. In line with such findings, five out of seven path coefficients involving subjective norms were more robust for the USA than for India.

Twenty-six relationships in Model A (see Table 3) and 41 in Model B—not shown—were examined, showing subtle model and country distinctions.

Subjective norms relationships were weak or nonsignificant for India. Similarly, EO construct relationships were weak or insignificant for both countries.

Given the diversity and the small magnitude of path coefficient differences, there are no notorious practical differences between the United States and India other than those of basic individual values and subjective norms referred to above.

Model 2 Series. Randomly selected relationships among eight TPB and EO constructs as mediators of the basic individual values–entrepreneurial intention relationship.

Table 4 presents the path coefficients, 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals, effect sizes, and total effects for a randomly selected model of the Model 2 Series, Model F. Results for the remainder of Series 2 models will be provided upon request.

Table 4.

Model 2 Series (Model F) path coefficients, confidence intervals (C.I.), effect size, and total effects.

In contrast to the “common view” and consistent with findings from Model A in Model 1 Series, our Model 2 Series results indicate that personal focus values exhibit stronger relationships in India compared to the United States. Surprisingly, and consistent with the results of the Model 1 Series, social focus values show slightly stronger relationships in the United States. Similarly, subjective norms demonstrate stronger relationships for the United States over India. Conversely, attitudes toward entrepreneurship relationships are slightly more robust in India. Regarding perceived behavioral control, relationships favor the United States. Results for relationships involving EO constructs vary, with the United States showing slightly stronger path coefficients for risk-taking, perseverance, and innovativeness. Passion-related relationships, however, favor India.

Perceived behavioral control exhibits stronger relationships with personal focus values, attitudes toward entrepreneurship, risk-taking, and entrepreneurial intention in India compared to the United States. Conversely, perceived behavioral control shows stronger relationships with social focus values, innovativeness, proactiveness, perseverance, and passion in the United States. The weakest relationships involve subjective norms and risk-taking.

Personal focus and social focus values show the strongest relationships, while those involving entrepreneurial intention are the weakest. Comparing India and the United States, personal focus values and passion-related relationships are stronger in India. In contrast, social focus values and subjective norms relationships are stronger in the United States.

Beyond the result patterns referred above, infrequent, insignificant, or weak relationships, whether common or unique to each country, contribute to the diverse spectrum of results observed across the multiple sets of models.

Model 3 Series. Perceived behavioral control as immediately anteceding entrepreneurial intention.

Table 5 presents path coefficients, 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals, total effects, and effect sizes for a randomly selected model of the Model 3 Series, Model R. Results for the remainder set of models of Series 3 will be provided upon request.

Table 5.

Model 3 Series (Model R) path coefficients, confidence intervals (C.I.), effect size, and total effects.

Personal focus values’ relationships with TPB and EO constructs were stronger in India, except for the relationship personal focus values > perseverance, for which the United States showed greater strength. Conversely, social focus values had stronger relationships with TPB and EO constructs in the United States, except for the social focus values > perseverance relationship, which was more robust in India. In India’s sample, many social focus values relationships were relatively weak.

In examining attitudes toward entrepreneurship, relationships with subjective norms and perceived behavioral control were stronger in India. In contrast, attitudes’ relationships with EO constructs were generally more robust in the United States, except for attitudes toward entrepreneurship > passion (a constituent of Model K—not shown here), which showed greater strength in India. Subjective norms relationships were stronger in the United States.

Relationships involving EO constructs varied. Risk-taking, innovativeness, and passion relationships were slightly stronger in India, whereas proactiveness relationships were stronger in the United States.

It may be noted that findings showing high perseverance and passion influences in India suggest that such behaviors are crucial under circumstances with limited resources.

Model R, shown in Figure 1, was randomly selected from 14 models in the Model 3 Series, and its full version was analyzed. It appears in Supplementary Materials. The full version adds 54 relationships to Model R. Overall, the findings align with trends observed in the Model 2 Series. However, in some cases, path coefficients decrease as the number of relationships increases.

5.3. The Three-Model Series Together

Table 6 summarizes all 23 models’ average path coefficients, their ranges, relationships’ frequency, and significance. Overall, personal focus values and passion relationships are stronger in India’s sample, whereas social focus values and subjective norms relationships are stronger in the United States sample. These findings are by and large unexpected—contrary to the “common view”. Other than the country distinctions discussed, no stark differences exist between the samples from India and the United States. For instance, relationships of attitudes with subjective norms, risk, innovativeness, proactiveness, perseverance, passion, and entrepreneurial intention are moderate to strong in the United States sample and weak, moderate, and strong in India. Furthermore, relationships of subjective norms with attitudes, risk, proactiveness, perseverance, passion, and entrepreneurial intention are stronger for the United States than for India. The relationship between subjective norms with innovativeness was weak and about the same for both countries.

Table 6.

Frequencies, averages, and ranges of path coefficients.

The relationships between personal focus values with perceived behavioral control were moderate for the United States and strong for India, whereas relationships between social focus values with perceived behavioral control were strong for the United States and weak for India. The impacts of attitudes towards entrepreneurship on perceived behavioral control were stronger in the Indian sample, and those of subjective norms on perceived behavioral control were stronger in the United States. The effects of risk on perceived behavioral control were weak to moderate in both countries. The impacts of employee innovativeness, proactiveness, and perseverance on perceived behavioral control were weak for both countries. The impacts of passion on perceived behavioral control were weak to strong in both countries.

6. Discussion

6.1. Discussion of Results

The purpose of this research was to conjointly study relationships among basic individual values, TPB constructs, EO constructs, and entrepreneurial intention and to consider contextual factors using a quasi-random sample with respondents from different organizations and industries from two economically and culturally contrasting countries, the United States and India, in 23 different model configurations. The construct set makes conceptual sense since constructs are interrelated and complementary but distinct (Blalock, 1979). The examination of this diverse set of models shows that entrepreneurship relationships within countries may be more varied and complicated than usually assumed.

Our findings illustrate some interplays between the general and the specific, which involve specific construct relationships or “subsets” of construct relationships. These results may question strongly and widely accepted and used generalizations, such as the “common view”, suggesting the need to increase research granularity and jointly consider what may be common and different. This type of study, with larger samples representative at the country level, may be viewed as an alternative, or complimentary, to meta-analysis because in undertaking the latter; it may not be possible, it may be questionable, or difficult to properly adjust for the most important contextual factors involved in studying a specific research question in order to produce a reasonable common metric (effect size).

The three-model series yields comparable overall results. Individual social focus values and subjective norms’ relationships are stronger in the United States. Conversely, personal focus values and passion relationships are stronger in India. These findings resonate with Takano and Osaka’s (1999) critique of the “common view,” challenging the notion that most Asian and Latin American countries are collectivistic while the United States is individualistic. All effects of perceived behavioral control on entrepreneurial intention were very strong both in the United States and India’s samples. Other construct relationships show subtle differences. As expected, path coefficients may decrease as the number of model relationships increases, except for basic individual values that remain strong antecedents.

Regarding basic individual values, as indicated by Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6 results, the United States exhibited stronger personal focus values relationships in 19 instances and stronger social focus values relationships in 53 occurrences. In contrast, India demonstrated a predominance of stronger personal focus values relationships, with 63 instances and only nine instances in which social focus relationships were stronger. Overall, only India’s results support H1, contradicting the “common view”. Strong personal focus values relationships for India may be explained as follows: (1) a strong collectivistic society producing a strong drive and sense of personal responsibility to better the economic situation of families, (2) high expectations for individuals in certain societal groups, like those of India’s sample, to engage in entrepreneurial economic activities, (3) education promoting entrepreneurial activities together with high levels of unemployment and underemployment increasing the focus on entrepreneurial activities as a possible way to succeed economically, and (4) young, urban, resource endowed individuals influenced by their exposure to Western values and lifestyles via the media and education (see sample demographics) may express more individualistic values including, among others, autonomy, individual decision-making, independence, individual achievement, and self-reliance. In this study, some of these explanations may be supported by considering that 92 percent of India’s respondents had a bachelor’s degree or higher education. However, there were a few exceptions. For instance, contrary results for perseverance suggest that societal pressures in India stemming from family and community values (Xheneti et al., 2021), religious expectations (Efferin & Hartono, 2015), and cultural traditions emphasizing individual sacrifice (Dees, 2012) may play a significant role.

Conversely, in the United States, there are extensive social safety nets and government support (Allen, 1999), which exhibit a dynamic different than India’s. Since situational factors shape these relationships in complex ways, some relationships may be rationalized one way (e.g., under the “common view”). In contrast, others may be rationalized differently (e.g., using specific situational factors). As in this study, most internationally focused studies’ findings apply to the specific sample analyzed (e.g., mostly managers, reasonably educated individuals, and respondents from certain companies or industries), and care should be exercised in generalizing at the country level.

Divergence in cultural and economic factors between the two countries shapes the relationships between basic individual values, the TPB and EO constructs, and those with entrepreneurial intentions differently. However, individual variability within each country is multiple times larger than among countries. Schwartz et al. (2012) refer to similar findings for several countries.

The mix of anticipated, unexpected, and subtle findings suggests the need to account for situational factors. Overall, the numerous relationships among basic individual values, TPB and EO constructs, and entrepreneurial intention are only slightly stronger in the United States than in India, thereby supporting Hypothesis 2. However, the results are varied. Given the intricacy and diversity inherent in the scrutinized relationships, it becomes necessary to adopt a paradoxical viewpoint. The United States, on an overarching scale, might be identified as more individualistic and entrepreneurial than India (Schwartz, 1994; Triandis, 1995; Hofstede, 2001; Oyserman et al., 2002; Markus & Kitayama, 1991; Chhokar, 2008; Hoppe & Bhagat, 2008), but this characterization necessitates delving into micro and meso levels. Various factors, including cultural, environmental, economic, and population group distinctions within and between countries, emphasize the significance of specificity for researchers and practitioners. Acknowledging the importance of both the general and the specific is crucial. An exclusive focus on the general overlooks the intricacies of the particular and vice versa. Moreover, a comprehensive consideration of both realms aligns more realistically with the complexities at play and enhances the likelihood of achieving practical success and value. The challenge lies in devising dependable metrics for relationships characterized by multidimensionality and multiperspectivity and jointly considering the general and the specific.

The three-model series examined offers a richer, more realistic perspective than those based on simple models. It unveils unexpected outcomes and provides a more robust identification of patterns than studies relying on a limited set of relationships. This approach encourages a more holistic understanding of the interplay between basic individual values, TPB and EO constructs, and entrepreneurial intention.

6.2. Theoretical Implications

The joint consideration of multiple configurations of a large set of constructs relating personal individual values, TPB, and EO effects on EI provides a more integrated understanding of entrepreneurship than the more frequently researched, linear, simplified models. The comprehensiveness of the models studied entails a higher degree of ontological correspondence with the contextual and practical variations of entrepreneurial realities. The examination of personal values enhances understanding of the beliefs, dispositions, and motivations that impact entrepreneurial intention. Likewise, researching personal- and social-focused individual values sheds light on their effects on attitudes, perceived behavioral control, and subjective norms, as well as on EO constructs that ultimately impact EI. Thus, this study sheds light on how individual values serve as the foundations of TPB, EO, and EI.

Furthermore, this integrated model offers the potential to disentangle the direct and indirect effects of specific values on EI. Additionally, studying the relationships between the EO and TPB constructs helps clarify how EO impacts TPB and how TPB, in turn, influences EO. For instance, higher EO may increase perceived behavioral control. Overall, a complex model, like the one examined in this study, is more realistic, has greater predictive power, and offers more room for maneuver for both research and practice.

The effects of considering different theoretical models require further study in terms of their implications, consistency, and validity, particularly when examining them jointly and potentially at different levels of granularity. Furthermore, this study suggests that results from simplified models may not hold when the same relationships are examined in more comprehensive models. Hence, future studies may investigate within-country variability regarding regions and social groups. In addition, future research may examine national differences in terms of country-level explicit and implicit incentive systems, which may help explain degrees and types of entrepreneurial activities.

6.3. Practical Implications

The closer the approximation to reality, the closer the gap between theory and practice. Thus, the higher the degree of integration of concepts, processes, and mechanisms involved in shaping EI, the higher the likelihood that policymakers will be able to design more effective programs geared toward increasing entrepreneurship, and the greater the room for maneuver both theoretically and practically. For instance, practitioners may target strengthening targeted values, enhance desirable construct synergies, decrease undesirable interactions, and be aware of and act upon constructs that cancel out their effects, thereby encouraging and supporting entrepreneurial activity. By giving primacy to country-level findings, regional and group differences within countries have been somewhat overlooked. Further understanding such differences will make research results more meaningful and useful for practitioners. Additionally, practitioners may be aware that results for specific relationships from simplified models may not be held when the same relationships are constitutive of more complex, and realistic, models.

6.4. Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the cross-sectional data precludes accounting for constructs’ patterns and changes over time. Second, this study’s sample, while exceeding the required size for a power of 0.95 for both countries, needs more complete representativeness for both the United States and India. Acknowledging this limitation is necessary for contextualizing the findings appropriately. Third, the samples studied include respondents younger and more educated than the general population of the countries studied. For example, 92 and 94 percent of respondents had a bachelor’s degree or higher in India and the United States, respectively. Likewise, 83 and 55 percent of respondents vs. 30 and 31 percent in the general population were between 20 and 40 years old in the United States and India’s samples, respectively. Younger and more educated individuals tend to be better informed, have more resources, and more confidence; consequently, they may tend to be more entrepreneurially oriented. Fourth, one of this study’s aims is to generalize insights across different organizations, industries, regions, states, and countries, which clashes with pursuing knowledge specific to particular organizational, industrial, or regional contexts. Despite adjusting results for demographic and other factors, the quasi-random sample introduces biases that need to be acknowledged. For example, making the sample per state proportional to the working population in each state. Fifth, this study’s divergence from the prevailing “common view” might challenge comprehension and acceptance. Simultaneously, entertaining conventional and alternative perspectives requires careful navigation and may be met with a lack of understanding and resistance. These limitations suggest the necessity for examining more complicated models and for exercising caution in interpretating and generalizing research findings.

6.5. Future Research

Enhancing the sample representativeness of countries under study requires augmenting efforts. Stratified and larger samples will not only bolster the representativeness of countries but also pave the way for subtle analyses at organizational, industry, and regional levels. Such a goal may be achieved through collaborative research networks fostering synergy and resource-sharing.

Future research may embrace increasing sophistication, augmenting research’s realism and practical applicability. Leveraging technological advances will facilitate a heightened degree of interplay within and between analysis levels. For instance, exploring the complicated interplay between individual-level values and broader national-level values and cultural dimensions may be an interesting avenue for inquiry. At the micro-level, interactions between personal traits, psychological constructs, and basic individual values and their influences on entrepreneurial intention can illuminate the complex multiplicity of factors shaping entrepreneurial intentions.

7. Concluding Remarks

In integrating the interactions among basic individual values, TPB and EO constructs, and their influences on entrepreneurial intention across a diverse spectrum of 23 model configurations, this study challenges the “common view.”

Contrary to prevailing expectations, the relationships involving basic individual personal focus values exhibited greater strength in India’s sample compared to the United States. Conversely, the United States manifested stronger relationships concerning basic individual social focus values and subjective norms. Although the relationships examined were stronger overall in the United States, this study shows a lack of stark disparities between the samples from India and the United States. Findings suggest variability within countries questions the dominant narrative characterizing Western and Asian countries as individualistic and collectivistic, respectively. The expansive model set examined in this study illustrates the variability inherent in relationships, spanning generalizable and context-specific realms. Results suggest the existence, within countries, of diverse sets of plausible model arrangements encompassing different degrees of both personal and socially focused constructs, which makes it difficult to generalize between countries. The crux of entrepreneurship research lies in the delicate balance between the pursuit of generalizability and the appreciation of specificity-rendering, making it more realistic and imbuing it with heightened practical value. The simultaneous and strategic embrace of both facets becomes imperative for enriching our understanding of the complex mechanisms underpinning entrepreneurial phenomena.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/admsci15080293/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.P.; M.R.I., and M.F.T.; methodology, L.P. and M.R.I.; software, M.R.I.; validation, L.P.; M.R.I., and M.F.T.; formal analysis, L.P.; M.R.I., and M.F.T.; investigation, L.P.; M.R.I., and M.F.T.; resources, L.P.; M.R.I., and M.F.T.; data curation, L.P.; M.R.I., and M.F.T.; writing—original draft preparation, L.P.; M.R.I., and M.F.T.; writing—review and editing, L.P.; M.R.I., and M.F.T.; visualization, L.P.; M.R.I., and M.F.T.; supervision, L.P.; project administration, L.P.; M.R.I., and M.F.T.; funding acquisition, L.P.; M.R.I., and M.F.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the approval from the Institutional Review Board at Texas A&M International University (#2023-02-28, 21 March 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

Data can be found in the following data repository: https://dataverse.tdl.org/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.18738/T8/LLRKEQ.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Achim, M. V., Borlea, S. N., & Văidean, V. L. (2021). Culture, entrepreneurship and economic development. An empirical approach. Entrepreneurship Research Journal, 11(1), 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahadi, S., & Kasraie, S. (2020). Contextual factors of entrepreneurship intention in manufacturing SMEs: The case study of Iran. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 27(4), 633–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Halbusi, H., Soto-Acosta, P., & Popa, S. (2024). Entrepreneurial passion, role models and self-perceived creativity as antecedents of e-entrepreneurial intention in an emerging Asian economy: The moderating effect of social media. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 41, 1253–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, P. (1999). Reweaving the food security safety net: Mediating entitlement and entrepreneurship. Agriculture and Human values, 16, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, B. S., Schueler, J., Baum, M., Wales, W. J., & Gupta, V. K. (2022). The chicken or the egg? Causal inference in entrepreneurial orientation–performance research. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 46(6), 1569–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audretsch, D. B., & Moog, P. (2022). Democracy and entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 46(2), 368–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awang, A., Amran, S., Nor, M. N. M., Ibrahim, I. I., & Razali, M. F. M. (2016). Individual entrepreneurial orientation impact on entrepreneurial intention: Intervening effect of PBC and subjective norm. Journal of Entrepreneurship, Business and Economics, 4(2), 94–129. [Google Scholar]

- Bae, T. J., Qian, S., Miao, C., & Fiet, J. O. (2014). The relationship between entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intentions: A meta–analytic review. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 38(2), 217–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R. P. (1992). The self-regulation of attitudes, intentions, and behavior. Social Psychology Quarterly, 55(2), 178–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R. A., & Ensley, M. D. (2006). Opportunity recognition as the detection of meaningful patterns: Evidence from comparisons of novice and experienced entrepreneurs. Management Science, 52(9), 1331–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beliaeva, T., Laskovaia, A., & Shirokova, G. (2017). Entrepreneurial learning and entrepreneurial intentions: A cross-cultural study of university students. European Journal of International Management, 11(5), 606–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, B., & Jelinek, M. (1989). The operation of entrepreneurial intentions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 13(2), 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blalock, H. M. (1979). The presidential address: Measurement and conceptualization problems: The major obstacle to integrating theory and research. American Sociological Review, 44(6), 881–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P. (1998). Practical reason: On the theory of action. Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Buhrmester, M., Kwang, T., & Gosling, S. D. (2011). Amazon’s Mechanical Turk: A new source of inexpensive, yet high-quality, data? Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6(1), 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carraher, S. M., Buchanan, J. K., & Puia, G. (2010). Entrepreneurial need for achievement in China, Latvia, and the USA. Baltic Journal of Management, 5(3), 378–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S., Chaudhuri, R., & Vrontis, D. (2024). Antecedents and consequence of frugal and responsible innovation in Asia: Through the lens of organization capabilities and culture. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 41(3), 979–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-J., & Huang, J.-W. (2009). Strategic human resource practices and innovation performance—The mediating role of knowledge management capacity. Journal of Business Research, 62(1), 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhokar, J. S. (2008). India: Diversity and complexity in action. In J. S. Chhokar, F. C. Brodbeck, & R. J. House (Eds.), Culture and leadership across the world. The GLOBE book of in-depth studies of 25 societies (pp. 971–1020). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, W. W., Thatcher, J. B., & Wright, R. T. (2012). Assessing common method bias: Problems with the ULMC technique. MIS Quarterly, 36, 1003–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y. R., & Shepherd, D. A. (2004). Entrepreneurs’ decisions to exploit opportunities. Journal of Management, 30(3), 377–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churchill, N. C., Carsrud, A. L., Gaglio, C. M., & Olm, K. W. (1987). Entrepreneurs—Mentors, networks, and successful new venture development: An exploratory study. American Journal of Small Business, 12(2), 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cop, S., Alola, U. V., & Alola, A. A. (2020). Perceived behavioral control as a mediator of hotels’ green training, environmental commitment, and organizational citizenship behavior: A sustainable environmental practice. Business Strategy and the Environment, 29(8), 3495–3508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covin, J. G., & Lumpkin, G. T. (2011). Entrepreneurial orientation theory and research: Reflections on a needed construct. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 35(5), 855–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damanpour, F. (1996). Organizational complexity and innovation: Developing and testing multiple contingency models. Management Science, 42(5), 693–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dees, J. G. (2012). A tale of two cultures: Charity, problem solving, and the future of social entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Ethics, 111, 321–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, T. K., & Henseler, J. (2015). Consistent partial least squares path modeling. MIS Quarterly, 39(2), 297–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efferin, S., & Hartono, M. S. (2015). Management control and leadership styles in family business: An Indonesian case study. Journal of Accounting & Organizational Change, 11(1), 130–159. [Google Scholar]

- Etcheverry, P. E., Le, B., & Charania, M. R. (2008). Perceived versus reported social referent approval and romantic relationship commitment and persistence. Personal Relationships, 15(3), 281–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J. J., Raposo, M. L., Gouveia Rodrigues, R., Dinis, A., & Do Paco, A. (2012). A model of entrepreneurial intention: An application of the psychological and behavioral approaches. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 19(3), 424–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foo, M.-D. (2011). Emotions and entrepreneurial opportunity evaluation. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 35(2), 375–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorgievski, M. J., Stephan, U., Laguna, M., & Moriano, J. A. (2018). Predicting entrepreneurial career intentions: Values and the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Career Assessment, 26(3), 457–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., & Tatham, R. L. (1998). Multivariate data analysis (5th ed., Vol. 5, pp. 207–219). Upper Saddle River. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J. F., Jr., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (2nd ed.). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, H., & Gimeno, J. (2010). Becoming a founder: How founder role identity affects entrepreneurial transitions and persistence in founding. Journal of Business Venturing, 25(1), 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions, and organizations across nations. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Hoppe, M. H., & Bhagat, R. S. (2008). Leadership in the United States of America: The leader as cultural hero. In J. S. Chhokar, F. C. Brodbeck, & R. J. House (Eds.), Culture and leadership across the world. The GLOBE book of in-depth studies of 25 societies (pp. 475–543). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

- House, R. J., Hanges, P. J., Javidan, M., Dorfman, P. W., & Gupta, V. (2004). Culture, leadership, and organizations: The GLOBE study of 62 societies. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.-T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igwe, A., Ogbo, A., Agbaeze, E., Abugu, J., Ezenwakwelu, C., & Okwo, H. (2020). Self-efficacy and subjective norms as moderators in the networking competence–social entrepreneurial intentions link. SAGE Open, 10(3), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (2013). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. In Handbook of the fundamentals of financial decision making: Part I (pp. 99–127). World Scientific. [Google Scholar]

- Karimi, S. (2020). The role of entrepreneurial passion in the formation of students’ entrepreneurial intentions. Applied Economics, 52(3), 331–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, A. K., & Brown, D. F. (2003). Latent constructs of proximal and distal motivation predicting performance under maximum test conditions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(1), 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreiser, P. M., Marino, L. D., Dickson, P., & Weaver, K. M. (2010). Cultural influences on entrepreneurial orientation: The impact of national culture on risk taking and proactiveness in SMEs. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 34(5), 959–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, N. (1993). The impact of prior entrepreneurial exposure on perceptions of new venture feasibility and desirability. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 18(1), 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruse, P., Wach, D., Costa, S., & Moriano, J. A. (2019). Values matter, Don’t They?–combining theory of planned behavior and personal values as predictors of social entrepreneurial intention. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, 10(1), 55–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, W.-S., Woo, H., Sadachar, A., & Huang, X. (2021). External pressure or internal culture? An innovation diffusion theory account of small retail businesses’ social media use. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 62, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liñán, F., & Chen, Y.-W. (2009). Development and cross–cultural application of a specific instrument to measure entrepreneurial intentions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(3), 593–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumpkin, G. T., & Dess, G. G. (1996). Clarifying the entrepreneurial orientation construct and linking it to performance. Academy of Management Review, 21(1), 135–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F. (2002). Positive organizational behavior: Developing and managing psychological strengths. Academy of Management Perspectives, 16(1), 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madden, T. J., Ellen, P. S., & Ajzen, I. (1992). A comparison of the theory of planned behavior and the theory of reasoned action. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 18(1), 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, J., & Marti, I. (2006). Social entrepreneurship research: A source of explanation, prediction, and delight. Journal of World Business, 41(1), 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (1991). Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review, 98(2), 224–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, S. L., & Thomas, A. S. (2001). Culture and entrepreneurial potential: A nine country study of locus of control and innovativeness. Journal of Business Venturing, 16(1), 51–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munir, H., Jianfeng, C., & Ramzan, S. (2019). Personality traits and theory of planned behavior comparison of entrepreneurial intentions between an emerging economy and a developing country. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 25, 554–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neelankavil, J. P., Mathur, A., & Zhang, Y. (2000). Determinants of managerial performance: A cross-cultural comparison of the perceptions of middle-level managers in four countries. Journal of International Business Studies, 31, 121–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, A., Obschonka, M., Moeller, J., & Chandan, G. G. (2021). Entrepreneurial passion: A review, synthesis, and agenda for future research. Applied Psychology, 70(2), 816–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J. C., & Bernstein, I. H. (1994). Psychometric theory New York. McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Olarewaju, A. D., Gonzalez-Tamayo, L. A., Maheshwari, G., & Ortiz-Riaga, M. C. (2023). Student entrepreneurial intentions in emerging economies: Institutional influences and individual motivations. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 30(3), 475–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyserman, D., Coon, H. M., & Kemmelmeier, M. (2002). Rethinking individualism and collectivism: Evaluation of theoretical assumptions and meta-analyses. Psychological Bulletin, 128(1), 3–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peer, E., Vosgerau, J., & Acquisti, A. (2014). Reputation as a sufficient condition for data quality on Amazon mechanical turk. Behavior Research Methods, 46(4), 1023–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintal, V. A., Lee, J. A., & Soutar, G. N. (2010). Risk, uncertainty and the theory of planned behavior: A tourism example. Tourism Management, 31(6), 797–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Alba, J. L., Guzman-Parra, V. F., Vila Oblitas, J. R., & Morales Mediano, J. (2021). Entrepreneurial intentions: A bibliometric analysis. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 28(1), 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, G., Marques, C. S., & Ferreira, J. J. M. (2020). Passion and perseverance as two new dimensions of an Individual entrepreneurial orientation scale. Journal of Business Research, 112, 190–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacker, R. E., & Lomax, R. G. (1996). A beginner’s guide to structural equation modeling. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, S. H. (1992). Universals in the content and structure of values: Theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries. In Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 25, pp. 1–65). Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, S. H. (1994). Beyond individualism/collectivism: New cultural dimensions of values. In U. Kim, H. C. Triandis, C. Kagitcibasi, S. C. Choi, & G. Yoon (Eds.), Individualism and collectivism: Theory, method, and applications. Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, S. H., Cieciuch, J., Vecchione, M., Davidov, E., Fischer, R., Beierlein, C., Ramos, A., Verkasalo, M., Lönnqvist, J.-E., & Demirutku, K. (2012). Refining the theory of basic individual values. Journal of Personality and Social psychology, 103(4), 663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, W. R. (1987). The adolescence of institutional theory. Administrative Science Quarterly, 32, 493–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y., & Kim, M.-J. (2015). Antecedents and mediating mechanisms of proactive behavior: Application of the theory of planned behavior. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 32(1), 289–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steers, R. M., Mowday, R. T., & Shapiro, D. L. (2004). The future of work motivation theory. The Academy of Management Review, 29, 379–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Takano, Y., & Osaka, E. (1999). An unsupported common view: Comparing Japan and the US on individualism/collectivism. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 2(3), 311–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J., & Bolton, B. (2013). Entrepreneurs: Talent, temperament and opportunity. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Thorgren, S., Nordström, C., & Wincent, J. (2014). Hybrid entrepreneurship: The importance of passion. Baltic Journal of Management, 9(3), 314–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triandis, H. C. (1995). Individualism & collectivism. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Wabba, M. A., & House, R. J. (1974). Expectancy theory in work and motivation: Some logical and methodological issues. Human Relations, 27(2), 121–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, L. J., & McGonagle, A. K. (2016). Four research designs and a comprehensive analysis strategy for investigating common method variance with self-report measures using latent variables. Journal of Business and Psychology, 31, 339–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. (2021, December 31). World Bank national account data. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/ (accessed on 20 April 2023).

- World Economic Forum. (2019). The global competitiveness report 2019. World Economic Forum. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/publications/global-competitiveness-report-2019/ (accessed on 15 March 2023).

- Xheneti, M., Karki, S. T., & Madden, A. (2021). Negotiating business and family demands within a patriarchal society—The case of women entrepreneurs in the Nepalese context. In Understanding women’s entrepreneurship in a gendered context (pp. 93–112). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, M., Hughes, M., & Hu, Q. (2021). Entrepreneurial orientation and new venture resource acquisition: Why context matters. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 38, 1369–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yukongdi, V., & Lopa, N. Z. (2017). Entrepreneurial intention: A study of individual, situational and gender differences. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 24(2), 333–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S. A. (2005). Entrepreneurial risk taking in family firms. Family Business Review, 18(1), 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zellweger, T., Sieger, P., & Halter, F. (2011). Should I stay or should I go? Career choice intentions of students with family business background. Journal of Business Venturing, 26(5), 521–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).