1. Introduction

The tourism sector represents a dynamic industry that significantly contributes to global economic growth (

Albaladejo et al., 2023). According to the World Travel & Tourism Council, in 2023 the travel and tourism sector contributed 9.1% to global GDP, corresponding to an increase of 23.2% compared to 2022 (

World Travel & Tourism Council (WTTC), 2023). To continue on a path to prosperity, the stakeholders involved in the tourism value chain need to recognize emerging hospitality trends and design appropriate strategies. Such an approach will aid in developing personalized tourism products in each region (

Harrington & Ottenbacher, 2010;

Teodorescu et al., 2015). A tourism product can be unique as it includes a variety of services offered, in which the strategic integration of local resources can contribute to the creation of a strong tourist destination brand and a region’s prosperous and recognizable identity (

Scuderi, 2018;

Niedbała et al., 2020;

Liberato et al., 2022).

More and more travelers are choosing to avoid mass tourism locations, which are often associated with high local prices and other negative characteristics (

Hou & Zhang, 2021;

Naumov, 2022;

He & Huang, 2023). These include a lack of authentic travel experiences, conflicts between the operators of tourism enterprises and local communities, and socio-cultural degradation (

Cassinger & Månsson, 2019;

Butcher, 2020). Thus, regions offering alternative forms of tourism can better satisfy new needs (

Naumov, 2022).

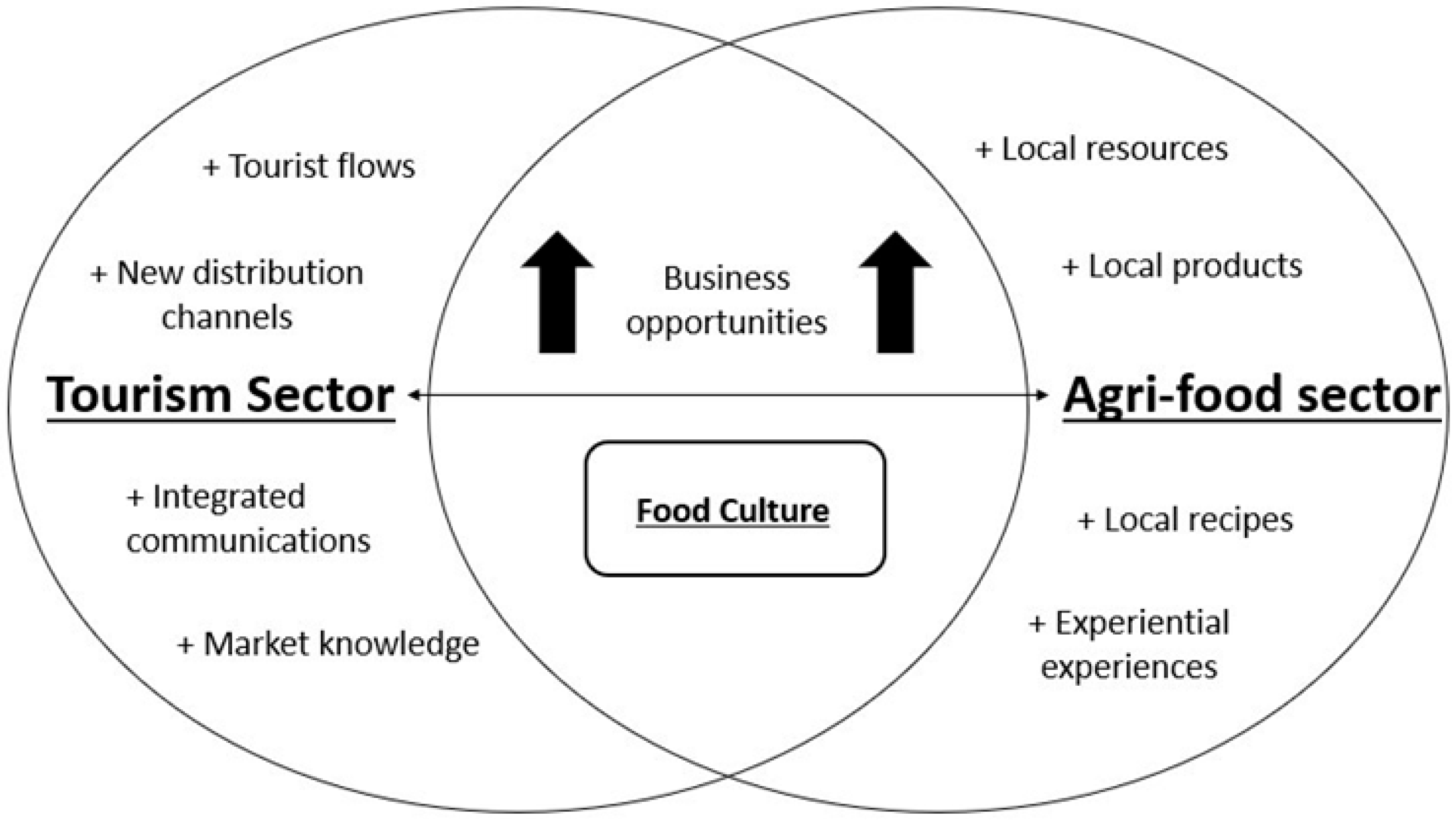

Dixit and Prayag (

2022) emphasize that strengthening relationships between tourism and local agro-food sectors can offer a gastronomic tourist experience, making destinations with these features more attractive in terms of cultural, economic, and socio-community sustainability. Travelers interested in culinary tourism prioritize food as their primary travel activity and show a preference for learning about local culture by tasting traditional agro-food products and beverages. The United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) emphasizes the importance of food culture, including beliefs, attitudes, and practices related to food production and consumption (

Herman & Matta, 2025). In this context, the organization recognizes the value of the Mediterranean diet and includes it on the List of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity (

Bonaccio et al., 2022). Food is an important tourist attraction factor in a region, as it includes several pleasurable local activities in which tourists can participate and act as carriers of culture, such as picking vegetables from open farms, bread-making processes, gastronomy trails, and visits to heritage sites such as old flour mills (

Hall & Sharples, 2004).

The agri-food sector meets visitors’ nutritional needs (

Bernal Escoto et al., 2021), ranking it as one of the leading suppliers of hotels and restaurants. It also creates the unique character of the countryside, attracts tourists of middle or high economic status interested in quality food to an area (

Hoffer et al., 2017). This will aid in enhancing the revenue stream, the incomes of the rural residents, and local economic development (

Raina et al., 2020;

Cerquetti et al., 2022). In addition to its essential contribution to the economy, tourism can provide alternative networks for the promotion and distribution of local food, creating new tourist experiences, including contact with agri-food. Thereby, there will be several opportunities for unique community expression through territorially distinct agricultural products and their production processes, cultivating cultural values (

Everett & Slocum, 2013). The development of synergies and business networks between tourism and localized agri-food systems (

Everett & Slocum, 2013;

Cerquetti et al., 2022) can act as a driver for regional development and as a source of business opportunities, stimulating local agricultural production through greater awareness of the public and private actors in matters of food culture. It may lead to creating jobs, attracting foreign investment, diversifying tourism products, and gradually building an unshakable competitive advantage for the local area (

Aydın, 2020;

Bernal Escoto et al., 2021;

Cerquetti et al., 2022).

The Peloponnese is located at the southernmost land point of Europe and is the largest peninsula in Greece. Mountain massifs dominate, but the region also has some of the most fertile plains in the country and a lengthy coastline. The Peloponnesian economy has always been based mainly on the primary sector (

Scoon, 2021). In 2021, the Peloponnese region contributed 672 million euros to the Gross Added Value of the country’s primary sector. In 2011, 50,439 people were employed in agriculture, forestry, and fishing in the Peloponnese region. The Peloponnesian vineyards are the largest in Greece (

ELSTAT, 2024). Tree crops occupied the most significant part (67%) of all holdings in 2016. The Peloponnese produces 31% of Greek olive oil worth 326.6 million euros, 17% of the country’s fruit worth 318.3 million euros, 8% of its fresh vegetables worth 134,1 million euros, and 27% of its olives worth 47.4 million euros (

Eleftheria Newspaper, 2018;

Labor Institute of GSEE, 2019). In 2016, the farmed animal population in the examined region was dominated by poultry (1,420,000 animals), followed by sheep and goats (400,000 animals). Cattle and pigs are at deficient levels in the Peloponnese region (

Labor Institute of GSEE, 2019).

The agricultural products of the Peloponnese make up a unique culinary identity, with distinctly recognizable products such as the apples of Arcadia, the olive oil of Messinia, the wine of Nemea, and the traditional recipes of Argolis (e.g., tyrolagano and pumeki) and Laconia (e.g., smoked Manis sausage and gogges) (

INSETE, 2021;

Skylakaki & Benos, 2023). This specific region comes second after Crete in terms of certified products with a Protected Designation of Origin (PDO) and first in terms of those with Protected Geographical Indication (PGI), showing the place’s close anchoring to local natural resources, tradition, history, and culture (

eAmbrosia—EU, 2024). More specifically, sixty-four local products from the Peloponnese have been certified as having a Protected Designation of Origin and a Protected Geographical Indication, such as the PDO Sfela cheese, the PDO Mainalo Vanilla Fir Honey, and the PGI Argolida Wines (

INSETE, 2021;

Skylakaki & Benos, 2023;

eAmbrosia—EU, 2024). The Peloponnese’s history begins in the late Paleolithic era, when it became a cradle of civilization. It has many archeological sites, museums, and monuments (

Scoon, 2021).

Although the Peloponnese has developed its tourism, there is still much scope for improvement. Tourism contributes most to the regional gross domestic product in the Ionian, Aegean islands, and Crete (

Pegkas, 2022). According to

INSETE (

2024), the Peloponnese region recorded the most significant percentage decrease in visits observed in 2023, moving to levels lower by 17.8% relative to 2022. It also showed an acute percentage decrease in tourist overnight stays (31.1%). Regarding travel receipts, the Peloponnese region recorded a 15.4% decrease in income (383 million euros) and a 16.2% decrease in the average length of stay, which was 7.6 nights. In 2017, 6.6% of the country’s catering businesses and leisure centers were in the Peloponnese region. The overview of those employed in the tourism sector in the region (the catering and accommodation industries in total) ranked it, in 2019, in fifth place in terms of the number of employees in the above sectors (5.45% of the country as a whole). The region has the second-highest percentage of total employment in the sector (

Skylakaki & Benos, 2023).

Karagiannis and Metaxas’s (

2020) focus on winemaking in the Peloponnese and comment on the potential business opportunities in terms of sustainability that could arise from cooperation with tourism, emphasizing the necessity of further research in this direction.

Although several studies have highlighted the relationship between tourism and gastronomy, insufficient research evidence exists to leverage the strategic triptych of food, culture, and hospitality to strengthen cooperative entrepreneurship. Thus, the aim of this study is to determine how food culture can be strategically utilized to strengthen collaborative entrepreneurship between tourism and agri-food businesses in the Peloponnese region (

Wolf, 2006;

Ottenbacher & Harrington, 2013). The Peloponnese has been chosen as a case study due to its rich historical and cultural heritage, which clearly shapes its identity. This region not only has a strong primary sector, but also offers excellent gastronomic products. Furthermore, the unique geomorphological features of the Peloponnese, which is bordered by the sea, create clearly defined boundaries similar to those of island regions, thus somewhat limiting the influence of external factors. Despite these advantages, the region has not yet fully exploited its potential for alternative tourism focused on food culture, which suggests significant opportunities for improvement in this area. The variety of agricultural products, including the renowned Messinian olive oil and the distinctive wines of Nemea, combined with the abundance of certified local foods recognized with Geographical Indication, underline a deep connection with local resources and cultural heritage. These characteristics of the Peloponnese form the basis for the implementation of strategic initiatives aimed at strengthening collaborative entrepreneurship and improving the sustainability of the agri-food and tourism sectors in the region (

Scoon, 2021;

Kougioumoutzis et al., 2022). The study’s theoretical framework is based mainly on the recent food tourism literature and the connection with local agriculture and the culture of a place, as well as regional development and strengthening entrepreneurship. The research questions examined in this study concern the exploitation of food culture in tourism activities to identify new business opportunities in the Peloponnese region. Specifically, the study seeks to ascertain the perceptions of stakeholders in the agri-food and tourism sectors regarding food culture and its potential for business exploitation. Furthermore, the objective of this survey is to identify actions that could be developed to enable the successful integration of food culture in tourism activities, especially from the perspective of collaborative entrepreneurship within the region.

The article uses primary and secondary data from an in-depth literature review and field research. The present paper provides preliminary findings that may be useful for future, more comprehensive research. The study comprises five sections: introduction, theoretical framework, methodology and data, results and discussion, and conclusions—strategic proposals and policies.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Aim and Objectives

The research aim was to examine the role of food culture during its strategic integration into the tourism industry’s actions in terms of exploiting business opportunities for the cooperating enterprises involved, emphasizing family-owned, small-, and medium-sized businesses.

The objectives of the study are as follows:

Recording public and private sector managers’ perceptions regarding the relationship between implementing tourism activities, including elements of food culture, and creating business opportunities for the collaborative network of the agri-food sector and the hospitality industry.

Investigating the degree of recognition of food culture as a source of creating business opportunities among the main stakeholders, distinguishing them into public and private agencies.

Identifying challenges and opportunities that influence the decision-making of the interested parties for the business exploitation of food culture.

3.2. Sample

Primary data collection took place in June, July, and September 2024. The study authors initiated contact with the sample organizations by telephone and then distributed the questionnaire via email. In the case of questions related to the questionnaire, the researchers provided clarifications, ensuring that participants understood the purpose and significance of the study. At the same time, the accuracy of the responses improved. The average time taken to complete the questionnaire was one hour. The survey population consisted of 116 individuals from public and private tourism and agri-food organizations in the Peloponnese region. In order to obtain a representative sample, a stratified sampling methodology was applied. Despite the limitations to the sample size resulting from time and financial constraints, this approach ensures that each subgroup or stratum is adequately represented in the overall sample. This study incorporated a wide range of organizations from both the public and private sectors in the Peloponnese, thus providing a comprehensive understanding of the dynamics of the food culture of the region. Specifically, the strata consisted of 69 public and 47 private organizations.

The sample included 59 organizations that successfully participated, representing more than half of the total sample. This group involved 35 public organizations, which included municipalities and various public services, as well as 24 private organizations. This diversity reflects the dual aspects of the tourism and agri-food sectors in the region. By ensuring adequate representation from both sectors, the study facilitates the exploration of possible differences in perceptions based on the type of organization, thus strengthening the overall validity of the findings. The study involved a wide range of associations, including hotel and accommodation federations, restaurant associations and organizations representing agricultural cooperatives located in the mountainous, semi-mountainous, and coastal areas of the Peloponnese. This integrated approach sought to identify variations in perspectives that may arise based on the geographical context of the areas under study. The primary objective was to include organizations from different geographical locations within the Peloponnese. This strategic choice enhances the understanding of how geographical disparities influence views on the challenges and opportunities related to the advancement of food culture.

The incorporation of geographical, organizational, and methodological parameters into our selection criteria significantly enhances the representativeness of our sample. However, despite the inclusion of a diverse range of entities, caution is necessary when generalizing the results, given the limited sample size and regional focus. The population of public entities includes 38 municipalities and 31 additional public services within the Peloponnese region. In contrast, the private sector includes 29 associations, composed of federations of hotels and lodgings, 8 associations representing restaurateurs and related professions, and 10 associations representing agricultural cooperatives.

Analysis of the dataset identified a maximum of five missing values, representing 8.9% of the participants for a single variable, which is close to the acceptable threshold of 5%. The remaining variables had less than two missing observations each. Given the minimal frequency of missing values, it was decided that imputation was not necessary. Regarding the demographics of the participants, the gender distribution was recorded as 53.4% male and 46.6% female. In terms of age, 70.7% of the participants were in the age group of 46 to 55 years, 13.8% were between 56 and 65 years, 8.6% were aged 36 to 45 years, and 6.9% were over 65 years. In terms of educational qualifications, 46.6% of the participants had a university degree, 22.4% had a master’s degree, 20.7% had completed technical school, 8.6% had a doctorate, and 1.7% had a high school diploma.

In addition, 52.5% of the participants reported having more than 25 years of experience in their current field, 25.4% had less than 10 years of experience, and the remaining 22.0% had between 11 and 20 years of experience. Finally, the average size of the organizations represented in this study was 301.4 members (SD = 572.6), with the largest organization comprising 3000 members and the smallest consisting of just 2.

3.3. Research Questionnaire

A structured questionnaire was used as a research tool consisting of a total of 22 main questions (not including the subscales), which were divided into four sections:

- (1)

Demographics (6 closed-ended questions and 2 open-ended questions);

- (2)

Interconnection of agri-food and tourism sector (4 closed-ended questions) (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.723, N = 31 items);

- (3)

Role of food culture in interdisciplinary cooperation (4 closed-ended questions) (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.647, N = 3 items);

- (4)

Food culture and business opportunities creation (6 closed-ended questions) (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.799, N = 31 items).

Assessment of the degree of food culture integration into organizations was conducted based on their responses to targeted questions in the questionnaire. This evaluation took into account their participation in various activities, such as attending relevant seminars or participating in networks related to business activities in the two sectors under consideration, etc. Participants were given the opportunity to express their opinions in text form for each question, if they wished. Qualitative responses were used as indicative feedback. However, no systematic analysis was performed, given that the primary objective of the article is quantitative in nature.

The content of the questions emerged after a thorough literature review (

Thomas-Francois et al., 2018;

Pratt et al., 2018;

Aydın, 2020), brainstorming, and small-scale pilot research with experts in the fields under consideration commenting on the appropriateness of the questionnaire. The validity of the instrument was rigorously assessed by field experts, ensuring its ability to accurately capture the perceptions of the research participants. In cases where inconsistencies were found within the questionnaire, appropriate revisions were made to enhance both clarity and validity. The reliability of the questionnaire was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, indicating a generally acceptable level of internal consistency. Specifically, a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient above 0.70 is considered acceptable, while values above 0.60 may indicate moderate reliability. In the section on food culture and the development of business opportunities, the highest value of this coefficient is noted.

3.4. Statistical Analysis

The statistical analysis conducted in this study included both descriptive statistics (including means, standard deviations, frequencies, and percentages) and inferential statistics (specifically, Mann–Whitney and Chi-square tests). Non-parametric tests were used due to the ordinal nature of the research data and the sample size. Significance levels were set at p < 0.05 and p < 0.01, adhering to standard confidence levels (alpha). The analyses were performed using SPSS software, version 22.0.

4. Results

The acceptable threshold for missing values in this analysis is 5% of the sample, which corresponds to a threshold of 56. In this case, only two questions were slightly below this threshold: the number of members in the organization (54) and the number of times the organization has organized or participated in food culture events, such as local food festivals, experiential cooking classes, farm visits, wine or cheese tours, and tasting evenings (55). Consequently, we consider the risk of bias in the results to be minimal.

Schafer (

1999) argued that a missingness rate of 5% or less is insignificant, while

Bennett (

2001) suggested that statistical analyses can be biased if more than 10% of the data is missing. Furthermore, there was no discernible pattern in the missing values, which supports the hypothesis that the omissions were random.

4.1. Interconnection Between the Agri-Food and Tourism Sectors

Regarding the identification of factors that play an essential role in integrating local agri-food products into the tourism industry, a significant majority of survey participants (84.8%) consider food quality to be a critical factor. Additionally, 84.7% emphasized the importance of establishing a collaborative network with enterprises in the primary or secondary sector. Furthermore, 81.3% recognized the importance of supporting the local and national economy, while 76.2% acknowledged the contribution of agricultural products to sustainable development. Finally, 59.3% of respondents consider attracting high-income tourists who want to try quality agri-food products to be an important factor.

Examining cooperation obstacles between the agri-food and tourism sectors, a significant proportion of the participants (71.2%) identified collaboration with local agri-food product suppliers as difficult. Additionally, 58.6% of the respondents believe that inadequate local food distribution network is a barrier. Lastly, 40.7% of the participants acknowledge that local agri-food products may not always be attractive due to their unstable appearance.

In the evaluation of agricultural product prices, a significant majority of the participants (89.9%) considered the prices of beverages to be expensive, followed by 81.0% for fish and seafood and 79.7% expressed similar concerns for dairy products and cold cuts. Furthermore, 76.3% considered the prices of dried foods to be high. Furthermore, 66.1% of the respondents consider the prices of fats and oils expensive, while 62.7% consider the prices of sweets and pastries expensive. Fresh fruit and vegetable prices were considered high by 55.9% of the survey participants and 53.5% commented in the same way on the prices of meat and poultry. A total of 48.3% of the participants considered the prices of frozen foods to be expensive, while 43.1% viewed the prices of herbs and spices as high. Additionally, 36.2% expressed a similar perception regarding the prices of pasta and legumes.

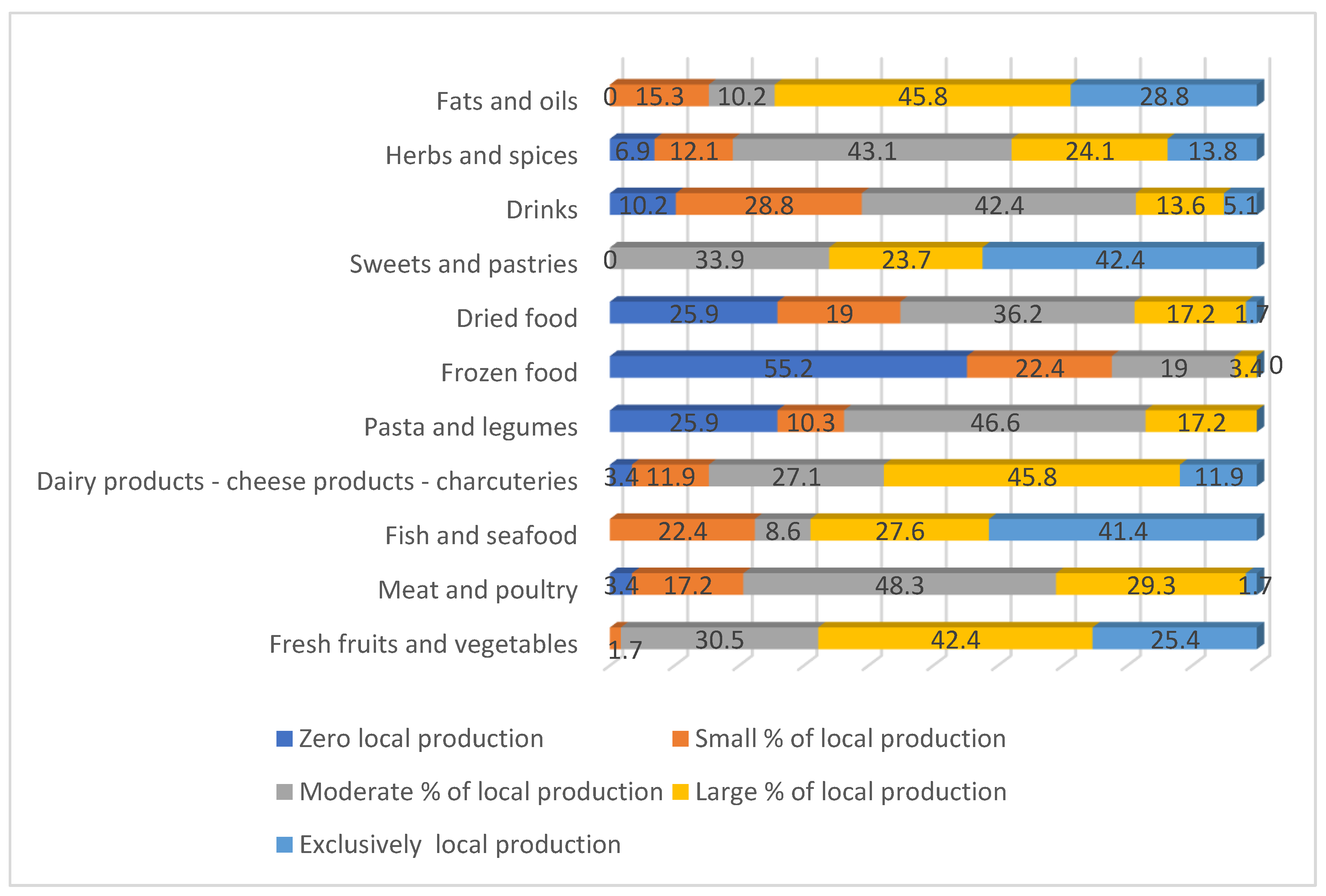

According to

Figure 2, 74.6% of the participants consider fats and oils to have successfully integrated into tourism activities, while 69.0% of the respondents have the same opinion regarding fish and sea food. In the Peloponnese, there are famous olive groves, such as in the prefecture of Messinia, where Kalamata olive oil is produced. Therefore, it is logical that fats and oils have been successfully integrated into tourism businesses. Fresh fruits and vegetables are considered integral by 67.8% of the respondents. Sweets and pastries are considered to have been sufficiently integrated into the tourism sector by 66.1 of the participants. Additionally, 57.7% of the participants consider dairy products to have been satisfactorily incorporated. Furthermore, 37.9% of the respondents recognize the integration of herbs and spices, while 31.0% held this opinion regarding meat and poultry. In contrast, only 18.9% of the participants consider the integration of dried foods into tourism to be sufficient. Beverages are considered to be integrated by 18.7% and pasta and legumes by 17.2% of the participants. Finally, only 3.4% of the respondents consider frozen foods to be satisfactorily integrated into tourism.

4.2. The Role of Food Culture in Interdisciplinary Cooperation

A total of 45.8% of the participants believe that food culture is a key factor when deciding on a travel destination. Furthermore, 52.5% of the respondents are neutral on this matter, while 1.7% of the participants disagreed.

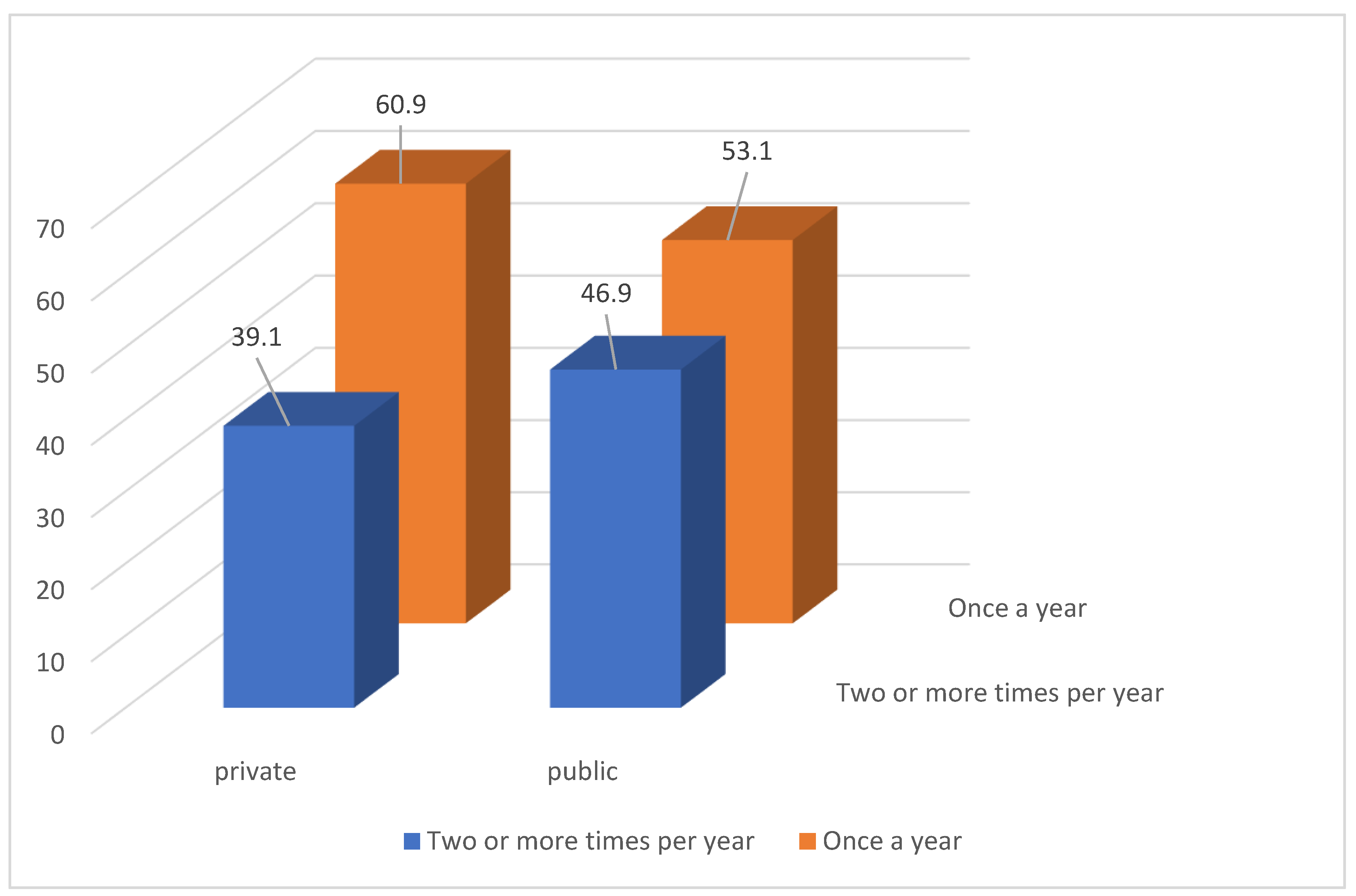

According to

Table 1, 51.4% of the participants believe that their organization is likely to implement an action on food culture within the next year. Furthermore, 24.6% of the respondents regarded it as quite likely, while the remaining 14% considered such an action unlikely. Regarding the frequency with which the organization has organized or participated in food culture-related events—such as local agri-food product festivals, experiential cooking classes, farm visits, wine or cheese routes, and tasting nights—participants were asked to report their experience. A total of 52.5% stated that the organization had engaged in such activities only once. In contrast, 40.7% of the respondents claimed that these events occurred two or more times per year, while 6.8% stated that they had never participated in any related activity.

Regarding the willingness to develop a cultural food experience in the area, including local agri-food products, recipes, and related customs, a substantial 76.3% of the participants stated their propensity to participate in such an initiative. Conversely, 10.2% of the participants remain uncertain, while 13.6% are reluctant to participate in the creation of a gastronomic cultural experience in the region. One of the participants in our research stated: ‘The entrepreneur must first of all realize the value of food culture in tourism and the benefits it can offer’.

4.3. Food Culture and Business Opportunities

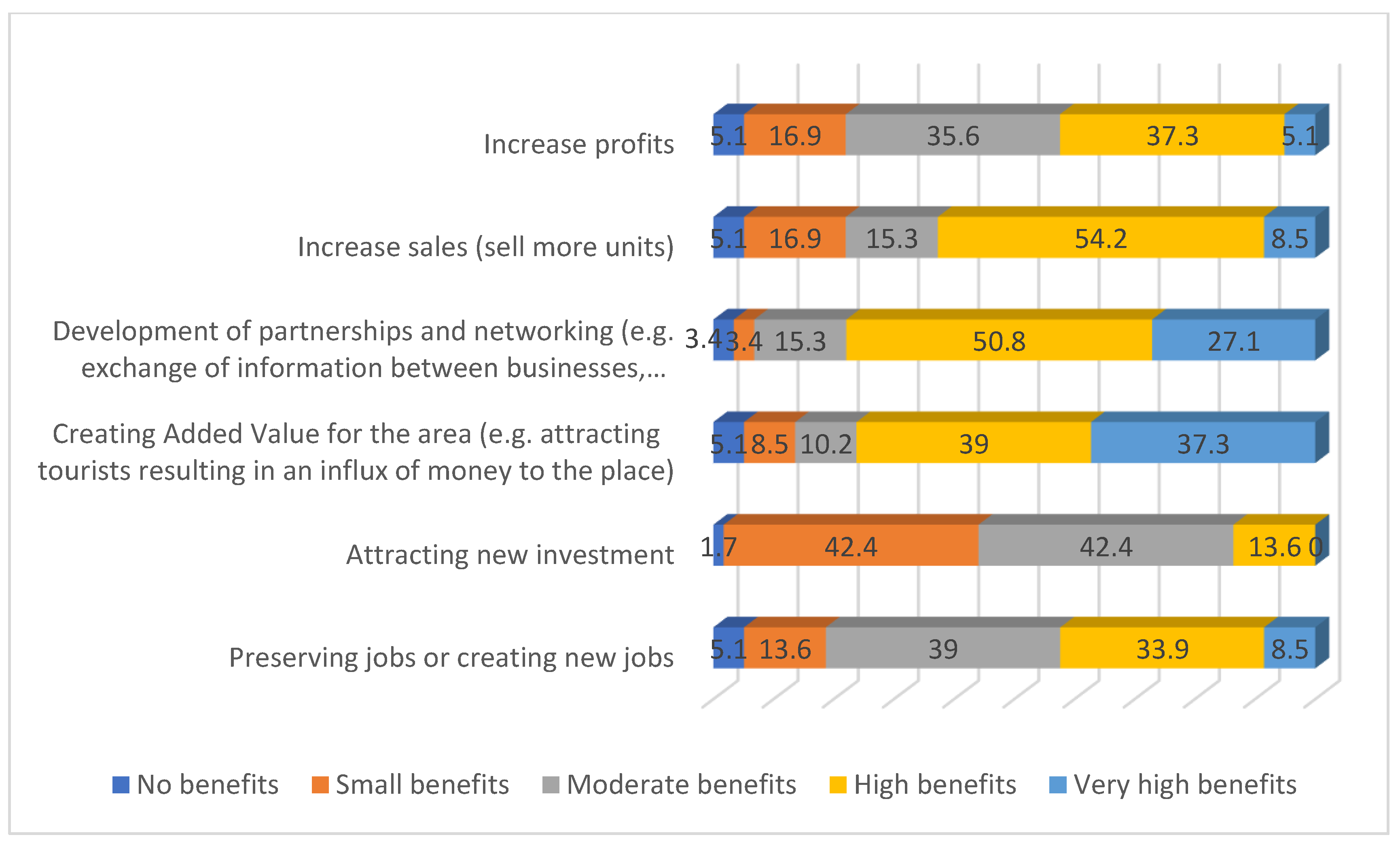

According to

Figure 3, 77.9% of the survey respondents recognize the development of partnerships and networking as a significant benefit of participating in initiatives related to food culture and tourism. Furthermore, 76.3% of the participants identify the creation of added value in the region as a significant advantage. Furthermore, 62.7% perceive sales enhancement as a benefit of such activities, while 42.4% recognize the positive impact on profit margins and the maintenance or creation of jobs. Finally, 13.2% of the participants consider the attraction of new investments to be a notable benefit.

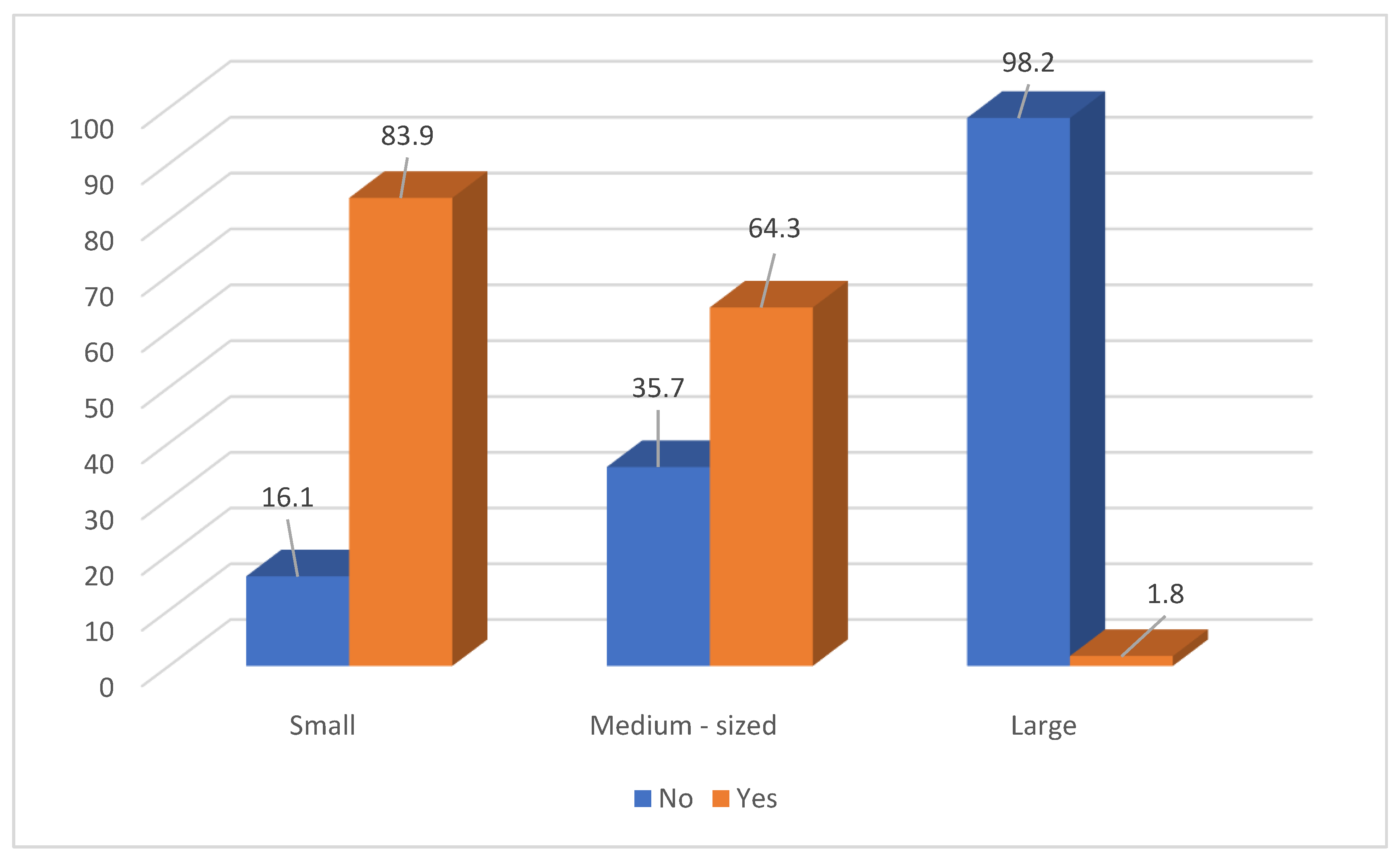

According to the data in

Figure 4, 83.9% of the participants believe that small businesses will benefit from the integration of gastronomic culture into tourism activities. Furthermore, 64.3% of the respondents argue that medium-sized businesses will also benefit, while only 1.8% think that large businesses would benefit.

According to

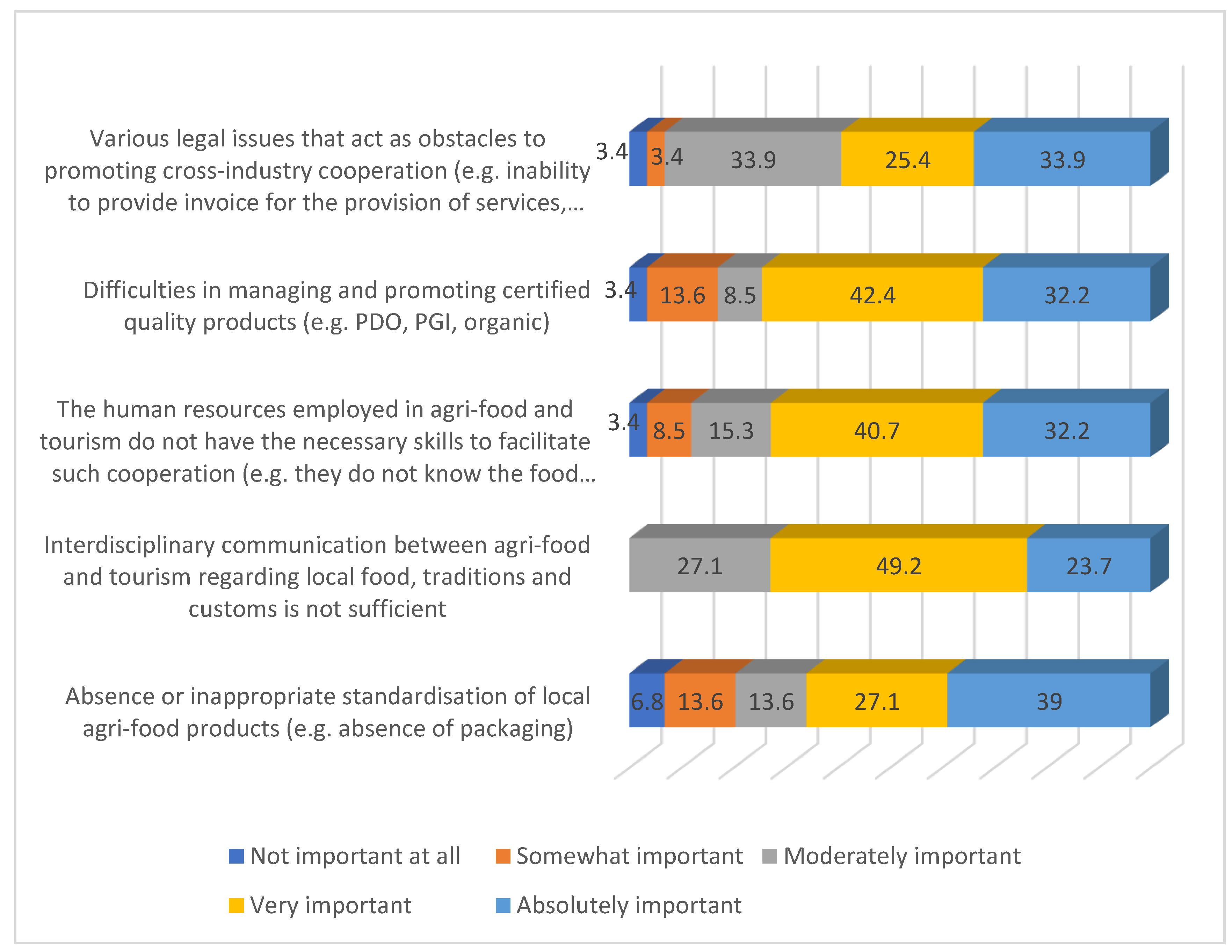

Figure 5, 74.6% of the participants believe that the potential of food culture has not been sufficiently exploited. They assert that numerous potential business opportunities have gone unexploited due to the challenges associated with managing and promoting certified quality products. Furthermore, 72.9% of the respondents highlight that the human resources employed in the agri-food and tourism sectors lack the necessary skills to facilitate effective collaboration. Additionally, 66.1% of the participants regard the deficiency in proper standardization of local agri-food products as a significant barrier while 59.3% express concern about various legal issues that hinder cross-sector collaboration.

According to

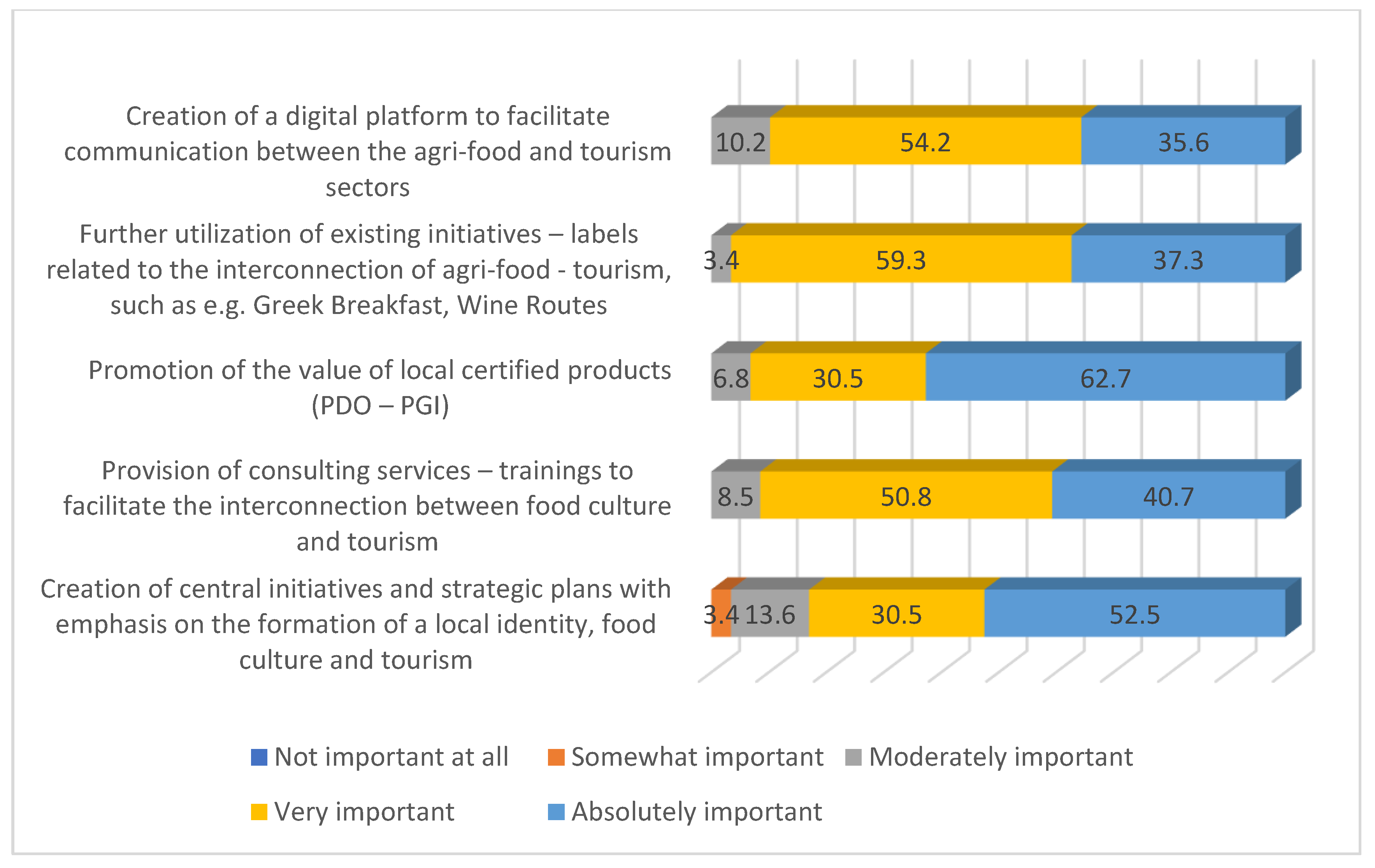

Figure 6, 96.6% of the participants argue that the further leveraging existing initiatives—such as the Greek Breakfast and the Wine Roads, which promote the interconnection between agri-food and tourism—would significantly enhance the development of gastronomic culture in these sectors. Furthermore, 93.2% of the respondents stressed the crucial importance of promoting the value of local certified products. Furthermore, 91.5% highlighted the necessity of providing advisory services and training to facilitate the integration of gastronomic culture and tourism. Furthermore, 89.8% recommended the creation of a digital platform to facilitate communication between the agri-food and tourism sectors. Finally, 83.0% of the participants underlined the need to create central initiatives and strategic plans that will prioritize the cultivation of local identity, gastronomic culture, and tourism.

According to

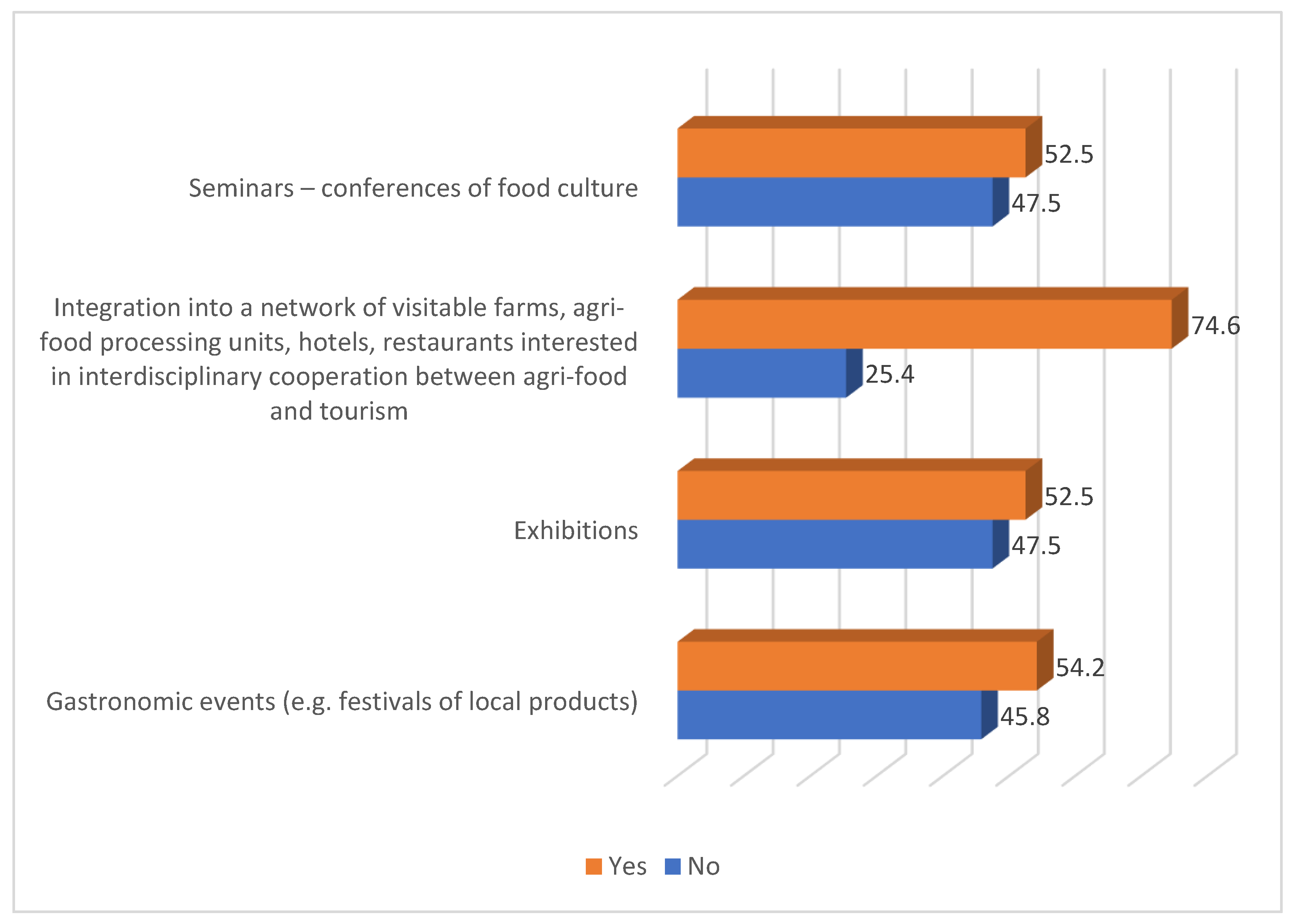

Figure 7, 74.6% of the participants showed a willingness to participate in initiatives related to the integration of visitable farms, agri-food processing units, hotels, and restaurants, which seek interdisciplinary cooperation between the agri-food sector and tourism. In addition, 52.5% of the respondents expressed interest in attending exhibitions or seminars and conferences focusing on food culture, while 54.2% emphasized their interest in gastronomic events.

According to

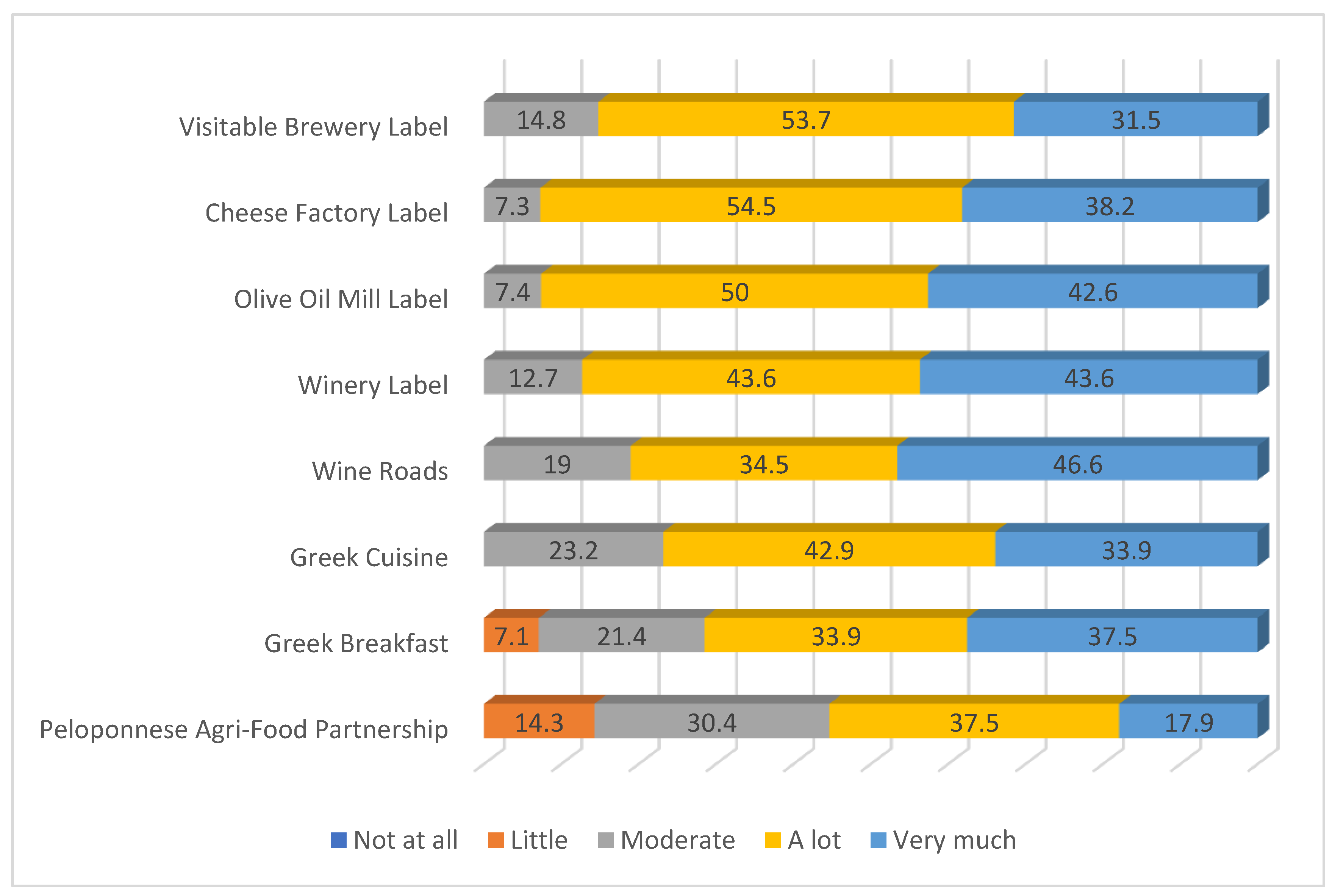

Figure 8, the vast majority of the participants assessed the effectiveness of different business initiatives as follows: 92.7% recognized the value of the cheese factory label, 92.6% recognized the olive oil mill label, 87.2% recognized the winery label as beneficial, and 85.2% considered the visitable brewery label useful. Furthermore, 81.1% of the participants considered the concept of wine roads advantageous, while 76.8% appreciated the importance of Greek cuisine. Additionally, 71.4% of the respondents recognized the importance of the Greek breakfast and 55.4% recognized the role of the Peloponnese Agri-Food Partnership in promoting local products.

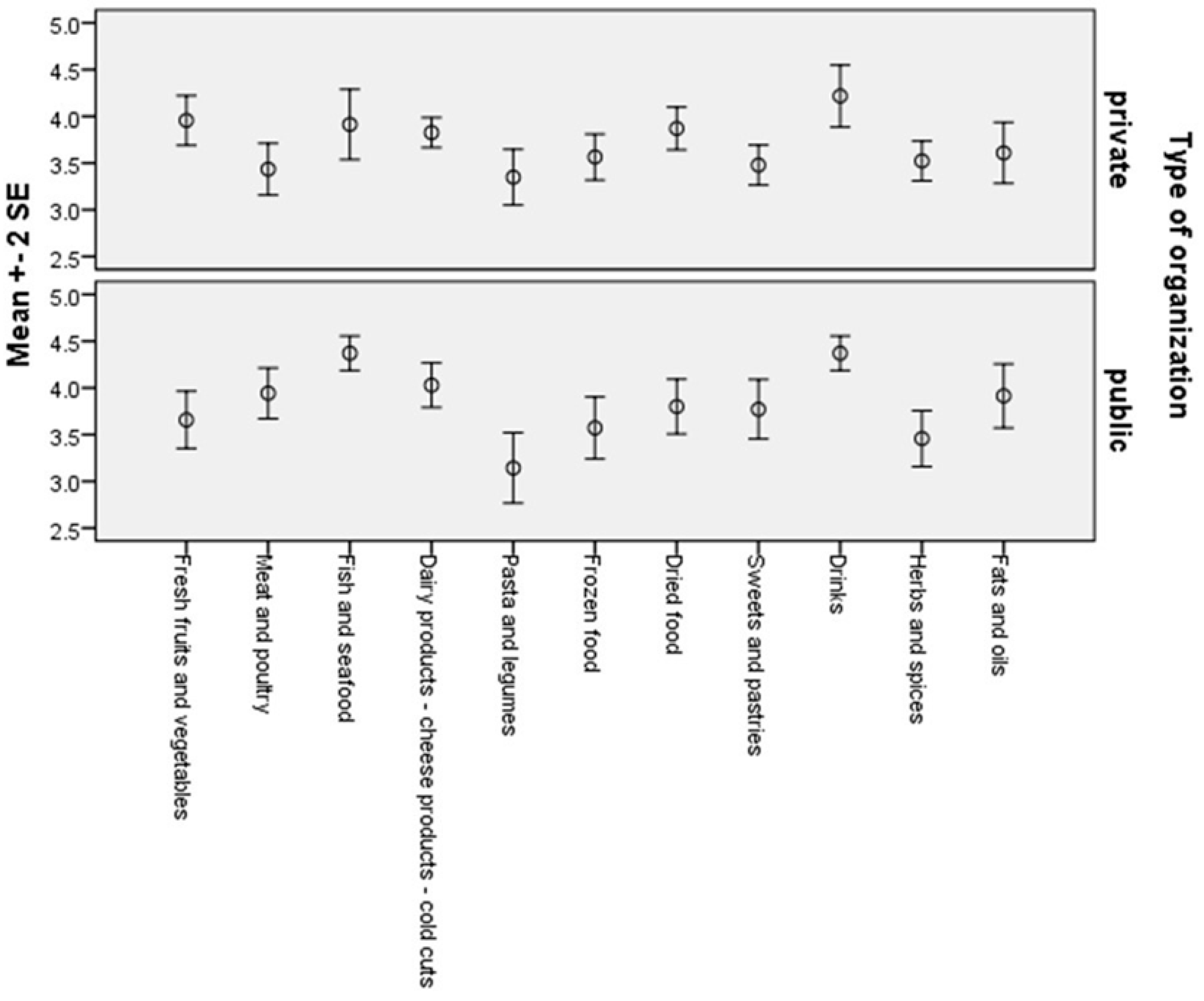

Figure 9 presents the results of the Mann–Whitney test, indicating that the normality assumption is not met according to the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test (

p < 0.05) (see

Table 2). The findings reveal that private organizations rate fish and seafood prices significantly higher than their public counterparts, with average scores of 4.4 for private organizations compared to 3.5 for public organizations (

p < 0.05). Furthermore, regarding herbs and spices, private organizations received an average score of 3.6, while public organizations gave an average score of 3.0 (

p < 0.05). For fats and oils, the average score for private organizations was 4.2, as opposed to 3.7 for public organizations (

p < 0.05).

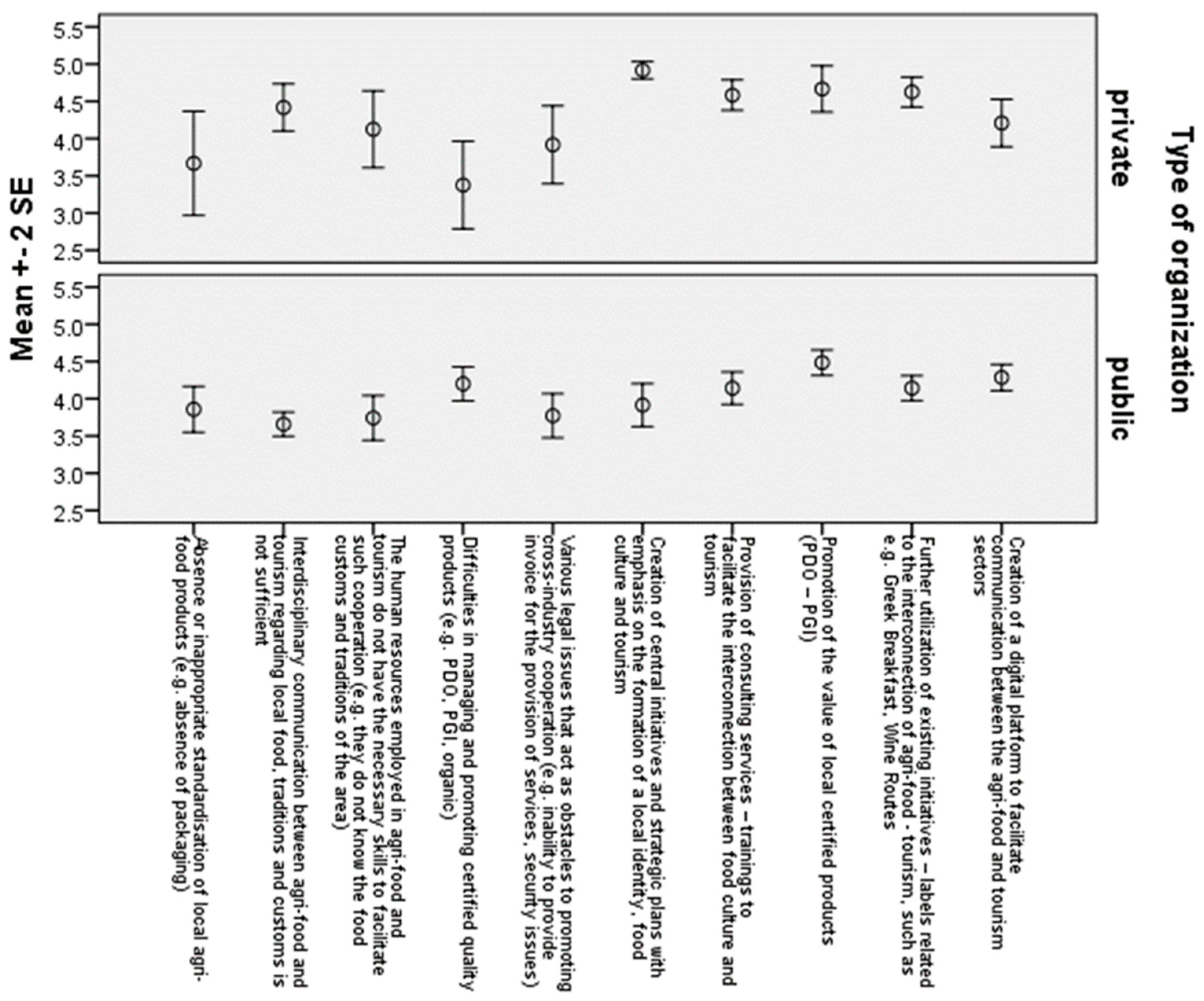

The findings from the Mann–Whitney tests, as depicted in

Figure 10 and described in

Table 3, reveal significant differences in the perceptions of private and public organizations regarding the integration of gastronomic culture in the agri-food and tourism sectors. Private organizations demonstrated a consistently higher assessment of the factors contributing to the underexploitation of gastronomic culture and related business opportunities compared to their public counterparts, indicating a clear divergence in opinions.

A significant divergence was observed in the perceptions of interdisciplinary communication between the agri-food and tourism sectors regarding local foods, traditions, and customs. Private organizations rated this communication with Mpriv = 4.4, while public organizations gave it a lower value of Mpub = 3.7, with the Mann–Whitney U statistic reported as U = 185,000 (p < 0.01). Furthermore, private organizations identified a more pronounced lack of basic skills among human resources in these areas that could facilitate improved collaboration, as indicated by scores of Mpriv = 4.1 versus Mpub = 3.7 (U = 291,500, p < 0.05).

In the context of factors leading to gastronomic culture development, private organizations demonstrated a more favorable attitude towards the formulation of central initiatives and strategic plans aimed at strengthening local identity and promoting gastronomic tourism. They reported average scores of Mpriv = 4.9 compared to Mpub = 3.9 (U = 133,000, p < 0.01). In addition, there was a recognized need for the provision of advisory services and training to enhance the integration of gastronomic culture with tourism, with scores of Mpriv = 4.6 and Mpub = 4.1 (U = 270,000, p < 0.01).

Both sectors recognized the importance of promoting local certified products, such as those falling under the Protected Designation of Origin (PDO) and Protected Geographical Indication (PGI) categories. However, the private sector gave a marginally higher score in this regard (Mpriv = 4.7 vs. Mpub = 4.5, U = 310,000, p < 0.05). Finally, private organizations emphasized the necessity of leveraging existing initiatives and labels related to agri-food and tourism, such as Greek Breakfast and Wine Roads, with reported scores of Mpriv = 4.6 compared to Mpub = 3.1 (U = 232,500, p < 0.01).

In

Figure 11, the results of the chi-square test show that there is no statistically significant relationship between the type of organization (private vs. public) and the frequency with which the organization has organized or participated in events related to food culture. The statistical findings are expressed as follows: χ

2(1) = 0.326,

p = 0.568.

In

Table 4, the data illustrate the willingness of organizations to participate in the integration of gastronomic culture into tourism activities. For those reporting a low level of integration, 71.4% of private organizations expressed a willingness to participate, in contrast to 52.9% of public organizations. It is worth noting that this difference is not statistically significant, as determined by the χ

2 test (χ

2(1) = 0.697,

p = 0.404).

In scenarios involving a high level of integration, the willingness to participate increases to 100% among private organizations, while 81.8% of public organizations similarly express a willingness to participate. However, this difference lacks statistical significance, as confirmed by the results of the χ2 test (χ2(1) = 2.010, p = 0.156).

When examining the combined responses for both high and low levels of integration, it is evident that 88.2% of private organizations tend to participate, compared to 64.3% of public organizations. This difference, however, is statistically significant at the 10% significance level, as indicated by the χ2 test (χ2(1) = 3.103, p = 0.078).

Based on the data analysis, we are forced to reject the research hypothesis “H0: There is no difference in operators’ perceptions of obstacles and opportunities affecting the development of food culture in agri-food and tourism at the business level”. This conclusion is supported by findings showing that private organizations rated the reasons for the insufficient exploitation of gastronomic culture higher than their public counterparts. It seems that business opportunities have been hindered due to the lack of interdisciplinary communication between the agri-food and tourism sectors. Furthermore, private organizations identified a greater number of factors that could enhance the development of gastronomic culture in agri-food and tourism. These factors include the creation of central initiatives and strategic plans that emphasize the formation of a local identity, the promotion of gastronomic culture and tourism, the provision of advisory services, and training to facilitate the interconnection between gastronomic culture and tourism, as well as the promotion of the value of local certified products (PDO—PGI) and the strengthening of existing initiatives and labels related to the integration of agri-food culture and tourism.

In relation to the research hypothesis “H0: There is no difference in operators’ perceptions of the impact of integrating food culture into tourism activities in order to develop business networks, regardless of the degree of integration (high or low)” a statistical difference was observed at a significance level of 10%. Although these differences do not reach statistical significance at the 5% and 1% levels, there is a strong indication of a difference in the perceptions of the actors regarding the impact of integrating gastronomic culture into tourism activities in order to develop business networks, regardless of the levels of integration. It is worth noting that, among organizations integrating food culture into tourism activities to varying degrees of, 88.2% of the private organizations showed a willingness to participate in a network of visitable farms, agri-food processing units, hotels, and restaurants interested in interdisciplinary cooperation between agri-food products and tourism, while 64.3% of the public organizations expressed a similar willingness.

Conversely, we accept the research hypothesis “H0: There is no difference in the perceptions between public and private collective bodies regarding the impact of integrating food culture in tourism activities to develop business networks”.

5. Discussion

The findings of this research indicate that the quality of food and beverages is the primary factor influencing the integration of agri-food products into the tourism sector. This claim is supported by numerous studies that emphasize the significance of high-quality agri-food products as a vital resource for enhancing the overall experience and authenticity of gastronomic tourism (

Armesto López & Martín, 2006;

Montanari & Staniscia, 2014;

Zhang et al., 2019). This quality is an integral part of strengthening tourist loyalty and contributes to promoting regional development. The participants in this study recognize the significant benefits associated with food quality, identifying it as a vital element in the relationship between agri-food products and tourism. Almost equal importance is given by the research participants to the above factor, to the extent of creating a network of cooperation with businesses in the primary and secondary sectors, regarding the integration of agriculture into tourism.

Petrou et al. (

2007) report that business networks facilitate cooperation between various businesses, allowing them to share resources, information, and even customers, strengthening the tourism product as a whole. The creation of economic benefits was highlighted as another critical factor in integrating agriculture and tourism (

Vourdoubas, 2020).

However, this integration is often hindered by various obstacles, such as the challenges of collaborating with local agri-food suppliers, as highlighted in the study results. Typically, supply chains are characterized by complexity, as they often have strict requirements regarding product processing, packaging, and delivery times, which can prevent small-scale farmers from collaborating with the tourism industry (

Boys & Fraser, 2019).

Most participants assessed agricultural products as being expensive, identifying beverages as the most prominent category (89.9%). A large percentage also consider fish and seafood (81%), dairy products and cold cuts (79.7%), and dried products (76.3%) to be expensive. As for fats and oils, they are considered less costly than the categories above; nevertheless, a significant concern remains here (66.1%). The Peloponnese has a long tradition of viticulture, which is part of the Peloponnese Wine Routes. These wines are often sold at high prices, as a symbol of their high quality and added value. This probably justifies the assessment of the survey participants regarding the price of the region’s drinks (

Valamoti et al., 2020;

Simeone et al., 2023). Accordingly, this region is surrounded by the sea, which favors the development of fishing. At the same time, there is a large number of aquaculture farms that significantly contribute to the local fish supply. Small-scale fishing, such as that developed in the Peloponnese, faces various challenges, including the organization of value chains, which considerably limits the pricing ability of small fishermen. As a result, they often cannot capitalize on the intrinsic value of fish, such as its freshness. The increased demand in the summer months, due to higher tourist flows and the region’s limited supply, may lead to a price increase for this specific food category (

Arnason, 2007). Similarly, dairy product prices are determined by supply and demand and production costs. A high price acts as a signal that higher quality products are being produced (

Kalita et al., 2004;

Donnellan et al., 2009).

From the above results, it can be seen that there is a general perception that a wide range of foods are expensive, which may affect the pricing strategies applied. The results on the integration of these products in tourism reveal that fats and oils (74.6%) and fish and seafood (69.0%) are considered well integrated, suggesting that these products could serve as essential attractions in the tourism sector. As the majority consider fresh fruits and vegetables (67.8%) and sweets and pastries (66.1%) to be integrated, there is potential for more dynamic promotion of these products in tourism. Dairy products, while regarded sufficiently integrated by 57.7%, may represent an area for improvement in their positioning in tourism, given their lower perceived integration compared to other categories. Pricing concerns could prevent some hospitality operators from adequately integrating specific food categories (

Van Huylenbroeck et al., 2006;

Wang et al., 2023).

The results of the survey show that less than half of the survey participants (45.8%) perceive food culture to be a primary factor in choosing a travel destination. From the above, we can conclude that there is an underestimation of food culture in attracting tourists even though the existing literature classifies food culture as an essential motivator (

Su et al., 2020).

And while as noted above a modest number of participants consider food culture a priority in selecting travel decisions, a significant percentage (76.3%) are interested in developing food culture experiences that incorporate local foods and drinks as well as the related traditions. This discrepancy lies in the fact that, although food culture is not considered a primary factor in choosing a trip, there seems to be a curiosity at the local level to try something like this.

More than half of the participants reported that their organizations have participated in food culture events only once, with a smaller proportion participating more regularly (with 40.7% participating two or more times a year). From the above data, it is evident that there is no consistent engagement with food culture activities. Perhaps increasing these activities or further promoting them would enhance their impact.

According to the participants’ views, this study suggests that there is a recognized need for collaboration among stakeholders, including farmers and tourism businesses, to develop food culture experiences. Various case studies suggest that collaborative schemes can enhance food culture initiatives, increasing tourism engagement and providing valuable insights for the strategic development of cooperative networks, thereby leveraging food culture as a tourist attraction (

Đurkin Badurina et al., 2023;

Massacesi et al., 2025).

The study’s results indicate that there is significant potential for improvement in perceptions and the implementation of actions related to food culture. More specifically, it appears that there is a gap between the recognition of the benefits of food culture and engagement with related activities.

The high percentage (77.9%) of respondents recognizing the benefits of partnerships and networking suggests that collaboration is considered essential for the development of food culture at the level of business cooperation in the tourism industry. The significant recognition (76.3%) of the creation of added value suggests a widespread understanding that integrating gastronomic culture into tourism enriches the region both economically and culturally. At the same time, perceptions of boosting sales (62.7%) and profit margins (42.4%) indicate a more conservative view of the direct economic benefits. The firm belief (83.9% for small businesses and 64.3% for medium-sized companies) that these entities will benefit from food culture highlights the potential of local businesses in such a business venture. Small companies typically prioritize local well-being. Developing strong business–community relationships, leveraging food culture, can increase business performance and community support (

Suutari et al., 2023).

The finding that 74.6% of the participants believe that the potential of food culture is not being fully exploited indicates missed opportunities. This can be attributed to several challenges mentioned above, indicating a need for improved collaborative frameworks to leverage local food culture better. The significant concern (72.9%) regarding human resource skills in the agri-food and tourism sectors indicates a critical area for development. Likewise, issues such as insufficient standardization of local products and regulatory obstacles were highlighted by a majority of respondents, underscoring that both quality control and policy environment need attention in order to fully capitalize on food culture.

The overwhelming support (96.6%) for further leveraging existing initiatives such as the Greek Breakfast and the Wine Roads reflects a strong desire for the stronger promotion of regional food culture. It appears that participants value structured programs that link agriculture and tourism. The emphasis (93.2%) on promoting local certified products reflects the recognition of the importance of authenticity and quality in attracting tourists and enhancing the food and cultural experience (

Zhang et al., 2019).

With 91.5% highlighting the need for education and advisory services, findings point to a clear need for action to equip stakeholders with the necessary knowledge and tools required to effectively integrate food culture into tourism (

Stone et al., 2022;

Horng & Tsai, 2012).

The high percentage (89.8%) recommending a digital communication platform indicates recognition of the importance of technology in terms of facilitating interactions and promoting synergies between sectors. Furthermore, the 83.0% supporting central initiatives and strategic plans suggests the need for organized, community-based approaches to strengthen local identity and tourism. A large percentage (74.6%) of the survey participants are open to participating in initiatives that aim to integrate farms, agri-food processing units, hotels, and restaurants. This indicates a strong interest in collaborations that could strengthen interdisciplinary efforts. One of the research participants said, “Closed cross-sector partnerships can mobilize interested entrepreneurs so that full-fledged collaborations can be created.”

There is a significant difference between private and public organizations in terms of pricing fish, seafood (p < 0.05), and other products, with private organizations valuing them significantly higher. This is likely due to the fact that private businesses are the ones that are involved in the daily marketing of such products. As a result, the pricing of food and beverages has a greater impact on their economic viability. In this context, there are several practical implications. The public sector should evaluate pricing strategies if it aims to support local fisheries or encourage the consumption of local seafood. If pricing is aligned with the way private actors perceive quality, then the incorporation of specific local products into businesses could increase. At a theoretical level, the differences between private and public actors support the exploration of theories related to the functioning of the agri-food sector in different institutional settings. Furthermore, they highlights the way in which public and private actors influence consumers’ perceptions of the prices of local food and beverages.

The findings suggest that there is a lack of interdisciplinary communication between the agri-food and tourism sectors. Both sectors recognize the need for enhanced collaboration; however, private organizations perceive the importance and need for it more strongly than public organizations. Both sectors acknowledge that existing human resources lack the necessary skills to facilitate collaboration (p < 0.05). Private organizations have a more favorable view of the factors that contribute to the development of gastronomic culture, including the value of strategic planning and consulting services, which suggests that they may be more receptive to such actions. The differences between private and public actors highlight the importance of developing interdisciplinary theories of collaboration, which enhance our understanding of the various interactions. Furthermore, this knowledge could contribute to the literature on rural and cultural economics. Of particular importance is the assessment of the economic value associated with the preservation of gastronomic and cultural heritage in tourism contexts.

The χ2 test does not show a statistically significant difference between private and public organizations in terms of their experience or participation in gastronomic culture events. This suggests that participation may depend more on factors other than the type of organization. Although private organizations show higher participation rates than public organizations at both levels of integration (low and high), these differences are not statistically significant. This means that although private organizations appear to be more willing, this trend is not verified with statistical reliability. Regarding the combined participation indicators (low and high integration), 88.2% of private organizations show willingness to participate compared to 64.3% of public organizations. This difference is statistically significant, suggesting that a trend worth further examination may exist.

After discussing the main results of the study, it is appropriate to propose a set of policy and management recommendations that would facilitate collaboration between tourism and agri-food businesses, with a focus on food culture, as follows:

To better align the quality of agricultural products with the objectives of tourism businesses, it is recommended that policymakers implement comprehensive quality assurance programs on a broader scale. These programs should prioritize sustainability and local sourcing of food and beverages, thereby promoting closer integration between the two sectors.

To strengthen business networks, local governments and tourism organizations should consider developing collaborative platforms that connect small food producers with hospitality businesses. Such platforms would facilitate the sharing of resources and the coordination of promotional activities. In addition, existing initiatives, such as wine routes, could be reimagined by incorporating a focus on food culture.

The creation of targeted training programs for small and medium-sized agri-food enterprises will include guidance on integrated supply chain management, entrepreneurship, and the provision of advisory services with a focus on developing partnerships. In addition, the implementation of financial incentives for infrastructure investments in small, traditional food processing units will serve as a complementary measure. In addition, the reduction in bureaucratic constraints for small agri-food enterprises is likely to enhance cooperation with tourism enterprises.

Policymakers can develop pricing strategies that favor local producers while providing incentives for tourism operators to choose local food and beverage options. To enhance this initiative, implementing price stabilization programs, along with establishing wholesale agricultural purchase agreements, could create a synergistic effect that benefits the local economy.

However, our study has certain limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. First, this survey only recorded the views of collective organizations from agri-food and tourism sectors and may not accurately reflect the opinions of individual entrepreneurs. Secondly, the views expressed by participants may significantly vary depending on their unique experiences, financial situation, and personal interests in cultural issues. Consequently, the findings may be influenced to some extent by subjective views. Third, the timing of the study may also influence the results of the research. Seasonal factors, such as fluctuations in tourism and climatic conditions, have the potential to influence perceptions of the quality and pricing of agricultural products. Fourth, the cultural value attributed to these products may differ between regions or communities. Finally, since the present research focuses on the Peloponnese, its results may not be generalizable to other geographical locations. Thus, to enhance the validity and generalizability of research findings, it is recommended to incorporate a greater degree of geographical diversity, increase the sample size, and conduct longitudinal studies to monitor potential changes in participants’ perspectives over time.

6. Conclusions

Food culture can enhance collaborative entrepreneurship between agri-food and tourism businesses. However, to achieve this, stakeholders in both sectors need to be aware of the value and benefits that can arise from leveraging food culture at a business level. In this way, businesses will be more inclined to engage in more activities related to local food and beverage culture. Issues such as pricing local food products, human resource capabilities in promoting local food culture, and the development of networks and better communication between the various stakeholders should be taken seriously. Further research is needed, involving the participation of agri-food and tourism businesses themselves, to create larger samples and encompass a broader range of geographical areas, to fully clarify the role of food culture in collaborative entrepreneurship.

The findings of this research can significantly contribute to the headline targets outlined in the European Green Deal and the Farm to Fork Strategy, which highlight the importance of sustainable food production and consumption. Sustainability is essentially based on three main dimensions: the economic, social, and environmental. The results of this study have the potential to encourage local agri-food and tourism businesses to pursue collaborative entrepreneurship by exploiting traditional foods and recipes within the context of food culture. This initiative can foster the development of economically resilient businesses that responsibly manage local resources, thus ensuring their long-term sustainability. Furthermore, a key objective of the European Union is to mitigate its carbon footprint, an objective that can be promoted through the insights provided by this study. By supporting the consumption of local food produced in their respective regions, we can significantly reduce transport distances, thereby reducing harmful emissions. Promoting cooperation between stakeholders in both the agri-food and tourism sectors, while supporting the sustainability of small and medium-sized enterprises, can strengthen social cohesion and address social inequalities. At the same time, this study creates important theoretical implications, such as further theory development regarding collaborative entrepreneurship, identifying the exploitation of local gastronomy in combination with culture as a specific cooperation strategy. Thus, these findings create opportunities to explore the influence of local food culture on business ecosystems and rural development. The need for better communication between various stakeholders can lead to new theories and the improved management of networks, with local food serving as a fundamental pillar that has emerged from tradition and culture. This study also has practical implications: agri-food and tourism businesses can improve their human resources through educational programs and workshops to further develop their skills in entrepreneurial exploitation and promotion of food culture. Additionally, new products or services, such as thematic tourist packages related to food culture, can be created. Finally, the findings of this study have a significant social impact, as strengthening food culture could enhance the social fabric of the region, fostering cooperation between residents and businesses. The promotion of local food and drinks can contribute to the preservation of cultural heritage, strengthening the unique identity of the place, and fostering community pride. Visitors, or tourists in the region, will be more aware of the local food culture and are likely to become more responsible in their consumer choices.

In the future, it would be beneficial to conduct additional studies in the broader field of food culture. Such research should aim to address critical research questions related to the formulation of effective strategies for the effective integration of Geographical Indication (GI) products into the agri-food and tourism cooperation network, as well as to assess the economic benefits that may arise from this effort. In addition, additional research could focus on identifying the optimal network structures between the sectors under investigation and on identifying policy measures that could facilitate this cooperation. Conducting interviews to collect both qualitative and quantitative data from business owners and policymakers would provide valuable information on these issues.