Systematic Bibliometric Analysis of Entrepreneurial Intention and Behavior Research

Abstract

1. Introduction

- RQ1. How has entrepreneurial intention and behavior research evolved in volume?

- RQ2. What patterns emerge in co-authorship (authors/institutions/countries) and co-citation (journals/references/authors)?

- RQ3. What factors directly influence entrepreneurial intention and behavior, and what factors serve as moderating roles in the transition from entrepreneurial intention to behavior?

- RQ4. How does the strength of entrepreneurial intention and behavior relationships change across different time intervals?

- RQ5. Which theoretical frameworks dominate current research, and where do gaps persist?

- RQ6. What are future research opportunities?

2. Methods

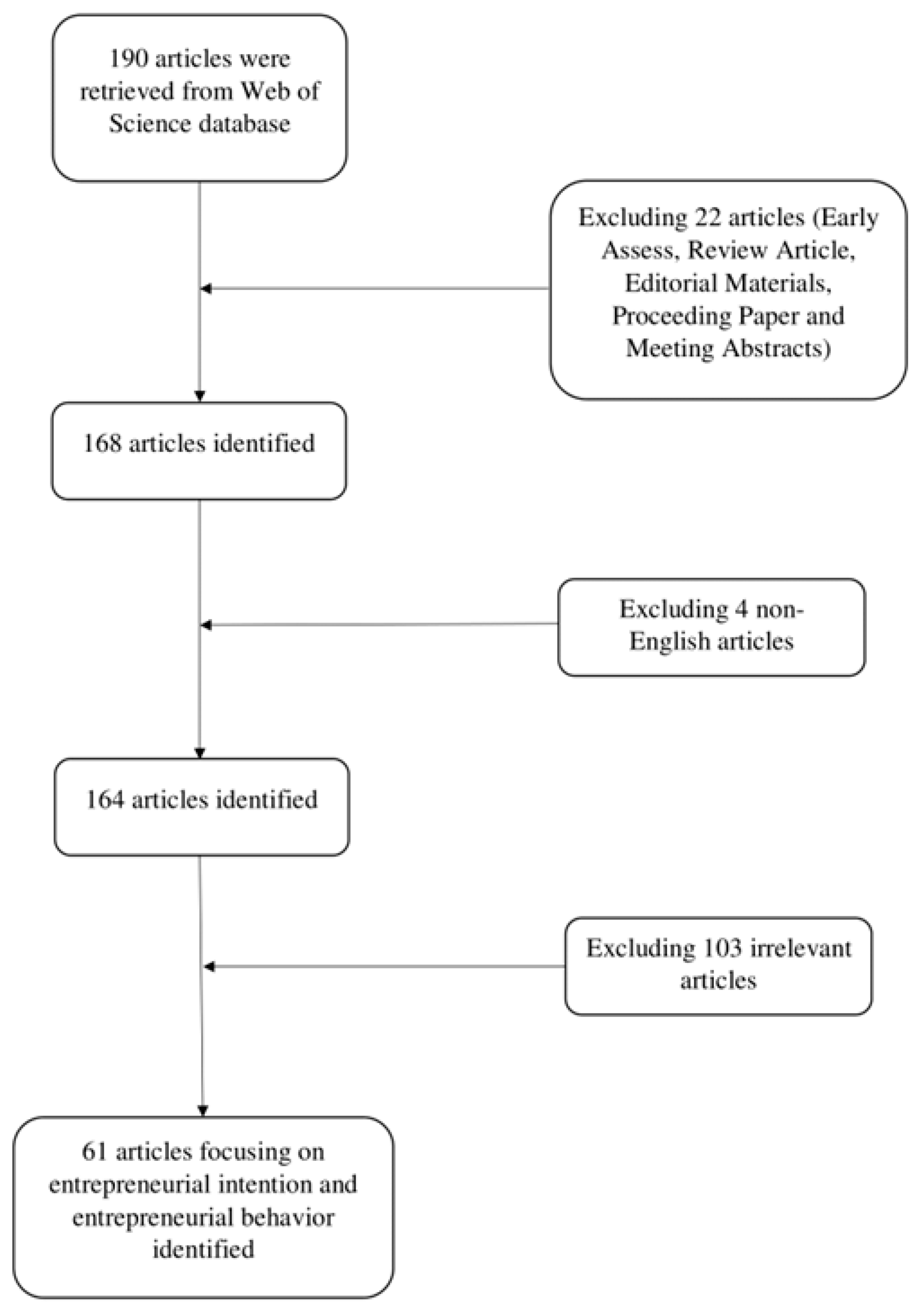

2.1. Data Source and Search Procedure

2.2. Research Method

3. Results and Discussion

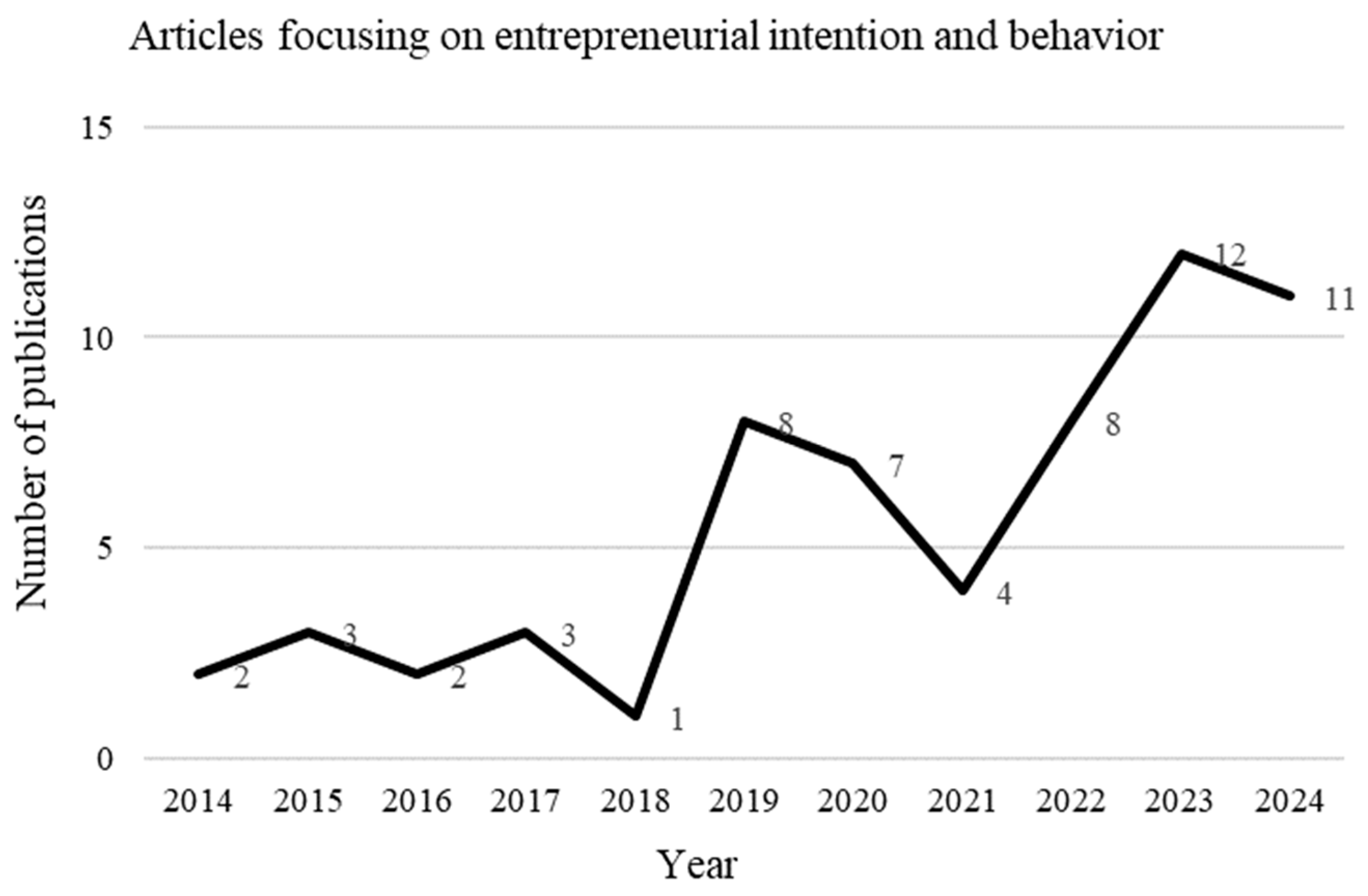

3.1. Publication Trends

3.2. The Co-Authorship Analysis

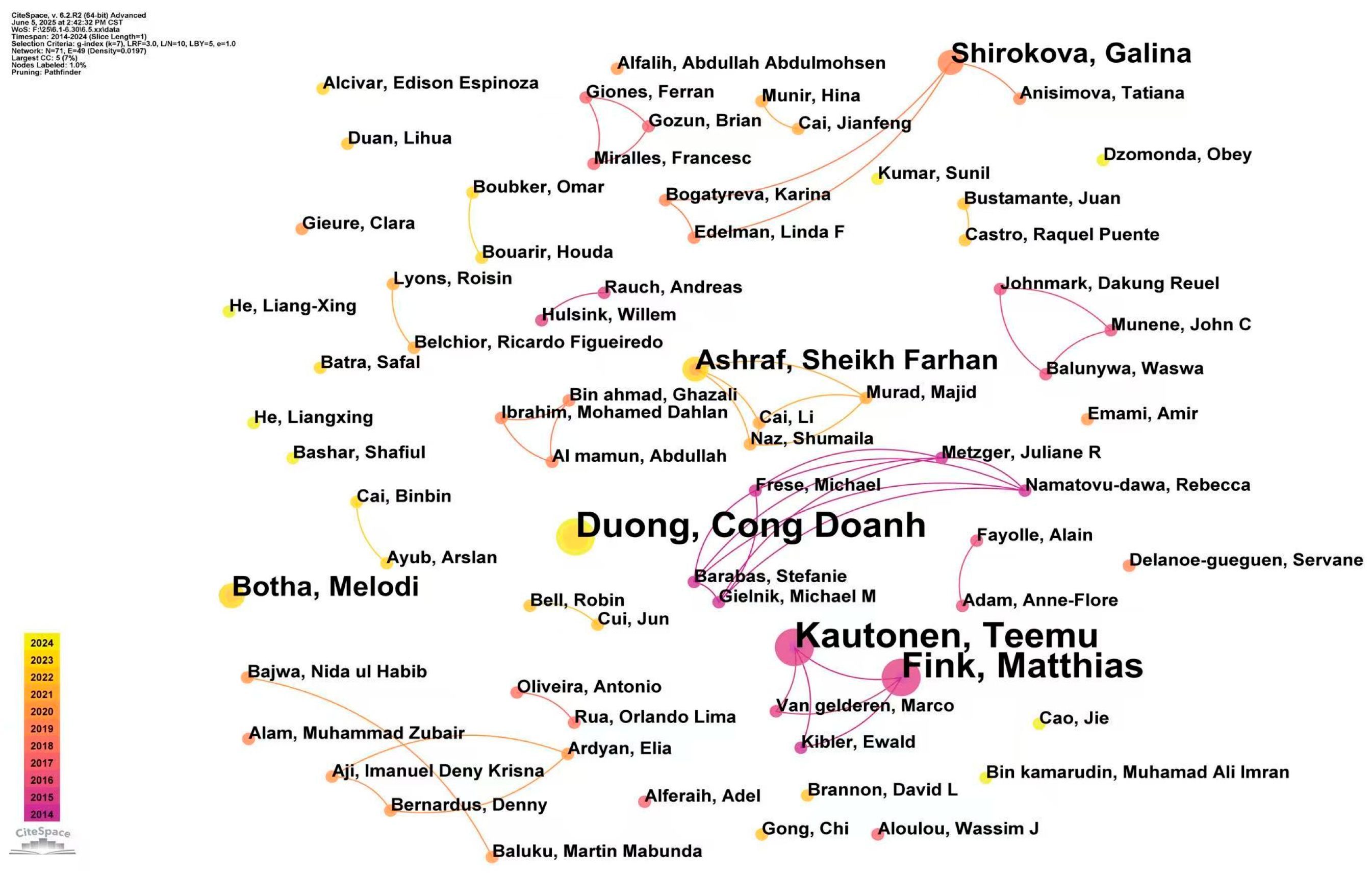

3.2.1. Analysis of Author Contribution

3.2.2. Analysis of Institution Contribution

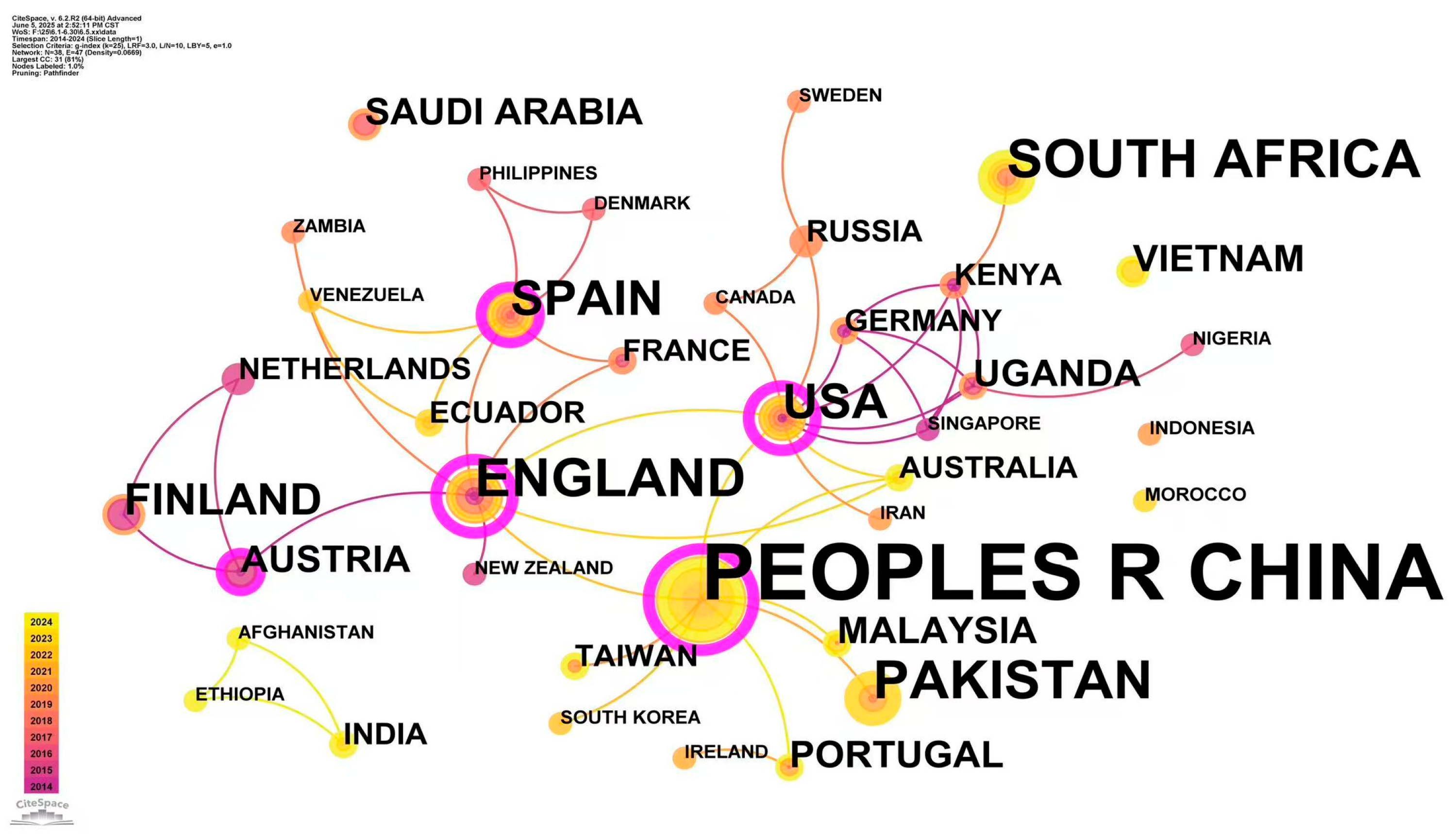

3.2.3. Analysis of Country Contribution

3.3. Co-Citation Analysis

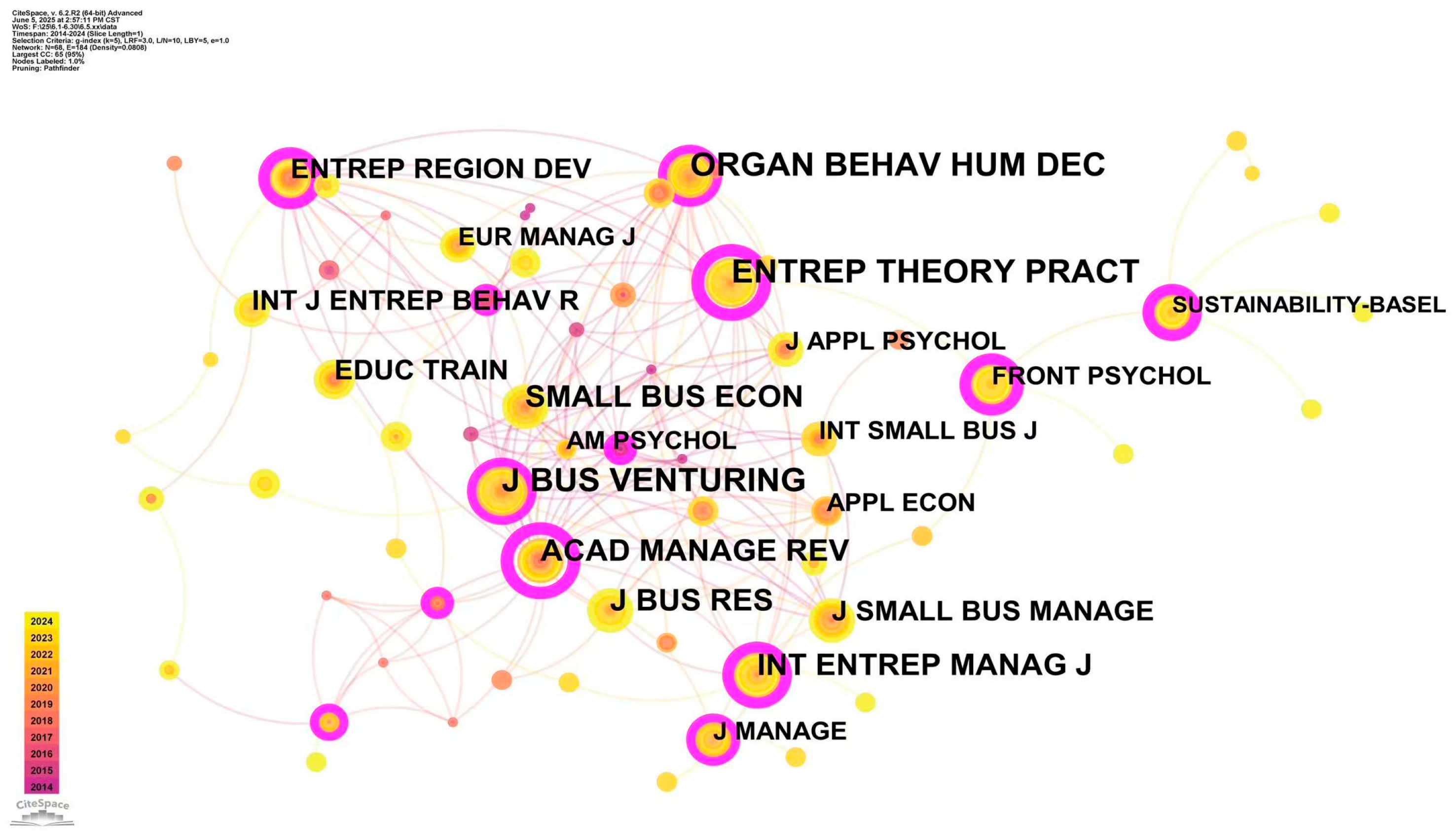

3.3.1. Analysis of Co-Cited Journals

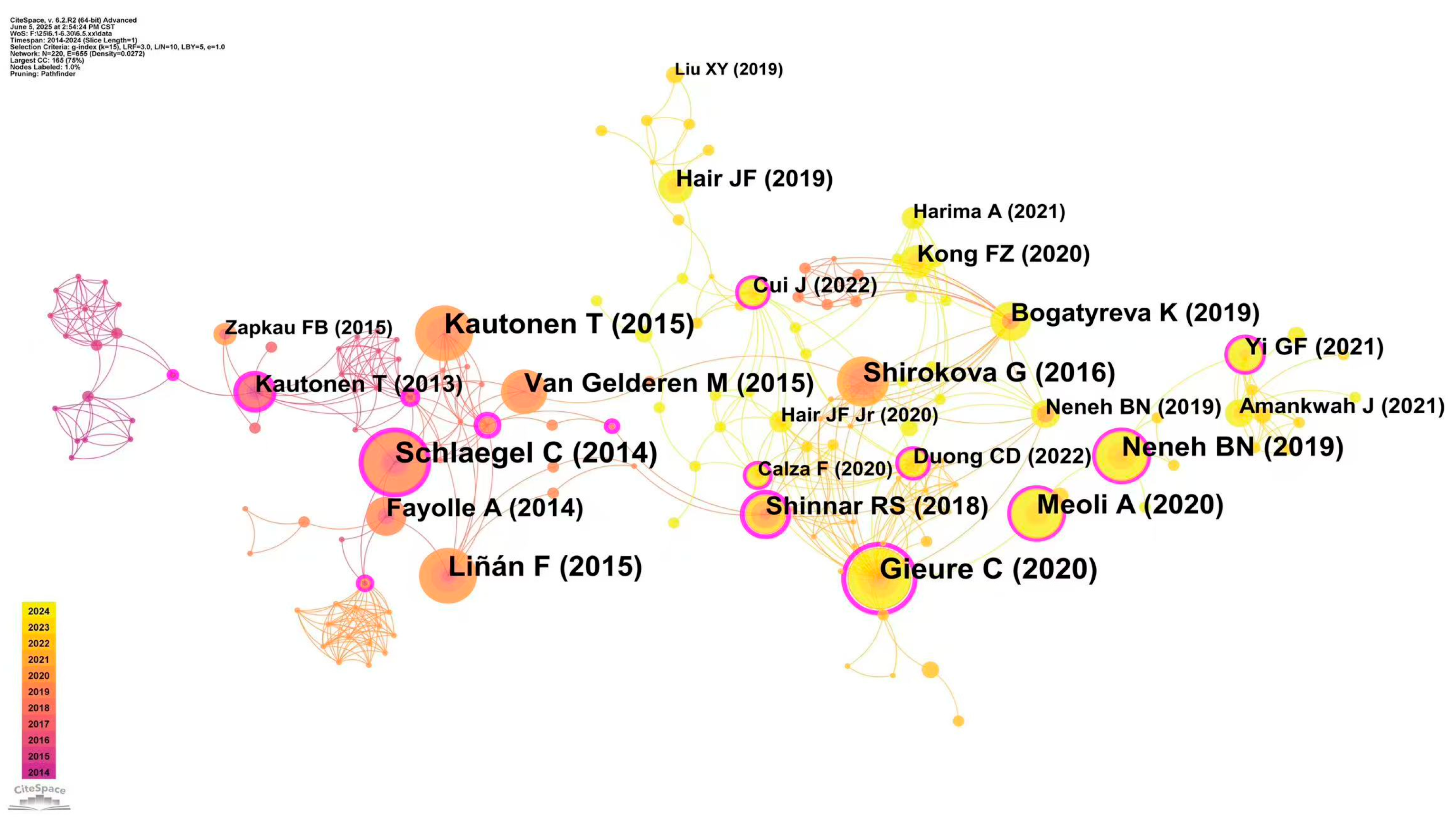

3.3.2. Analysis of Co-Cited References

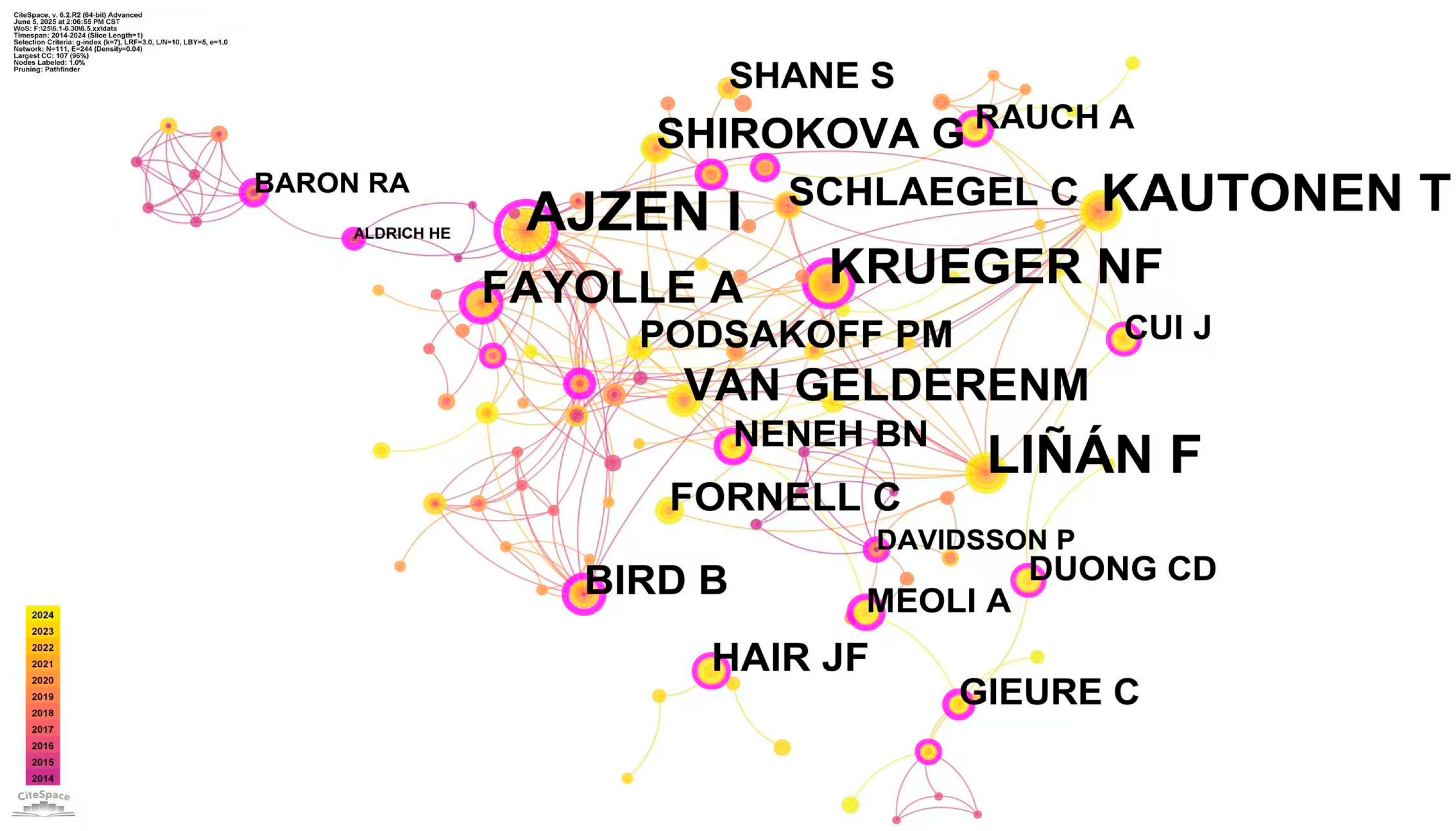

3.3.3. Analysis of Co-Cited Authors

3.4. Analysis of Research Hotspots

3.4.1. Keyword Co-Occurrence Analysis

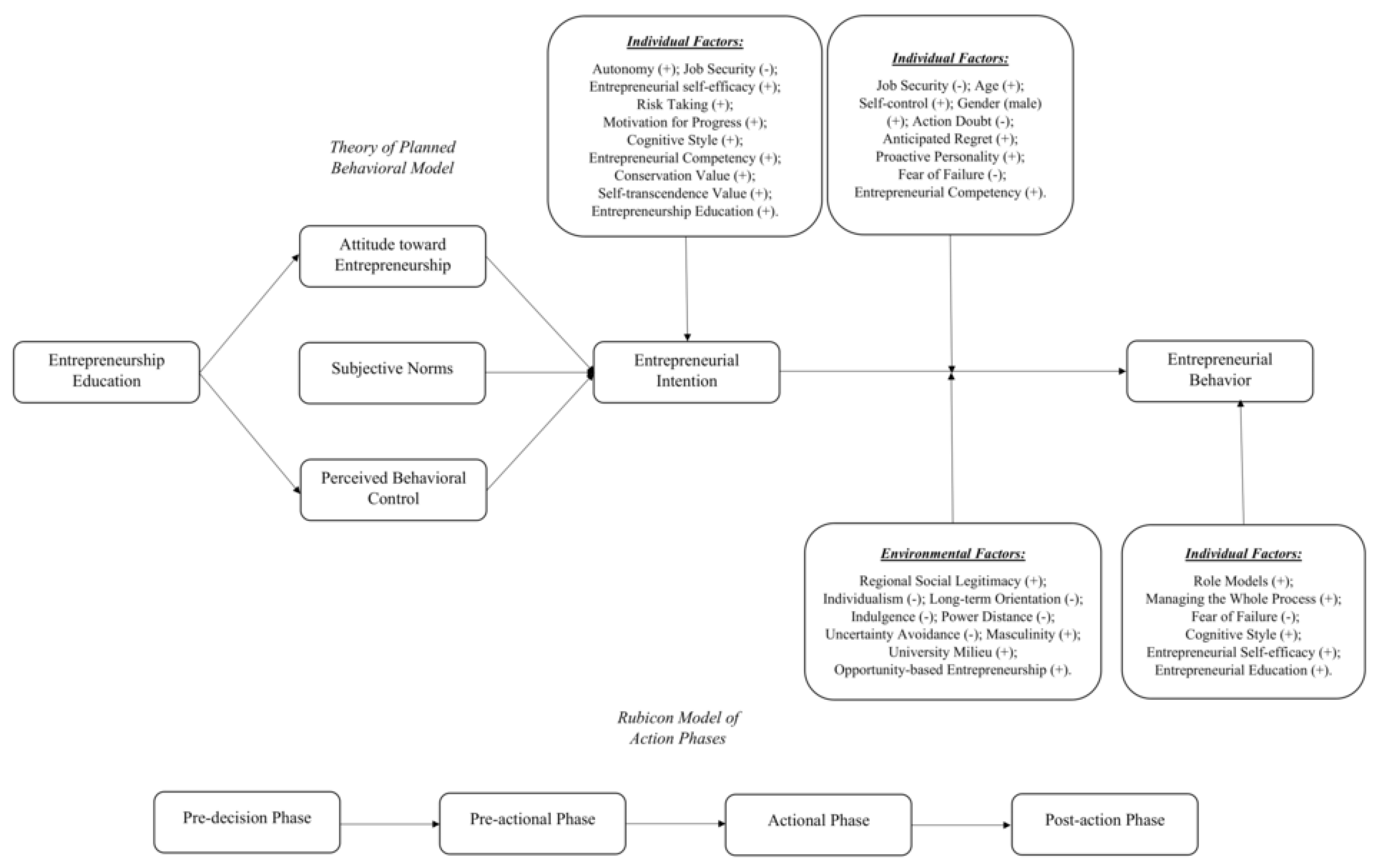

3.4.2. The Analysis of Research Hotspots by an Analytical Framework

The Direct Effects on Entrepreneurial Intention and Behavior

Moderating Effects Between Entrepreneurial Intention and Behavior

Longitudinal Surveys with Different Data Waves and the Correlation of Transition

- (1)

- Short-cycle studies (3–6 months):

- Van Gelderen et al. (2018): Swedish population (N = 422), 6-month interval;

- Baluku et al. (2020): Student cohort (N = 149), 4-month interval.

- (2)

- Annual-cycle studies:

- Kibler et al. (2014): Finnish (N = 732) & Austrian (N = 252) samples, 1-year interval;

- Van Gelderen et al. (2015): Two-wave survey (2011–2012; 1-year interval), Finnish adults (N = 703).

- (3)

- Multi-year longitudinal studies:

- Liñán and Rodríguez-Cohard (2015): Three waves spanning 2004–2007;

- Delanoë-Gueguen and Liñán (2019): Two-wave study with 5-year interval (N = 155);

- Santos et al. (2021): Decadal tracking (2010–2019, N = 593).

- (4)

- Temporal Decay in Predictive Strength (notes: *: p-value < 0.05; **: p-value < 0.01; ***: p-value < 0.001.)

- The EI-EB correlation remains significant but attenuates over time (Shinnar et al., 2018):Short-term: 0.66 ** (1 semester) → 0.97 ** (6 months);Long-term: 0.78 * (3 years).

- Similar decay observed by Joensuu-Salo et al. (2020):0.727 *** (1–3 years after graduation) vs. 0.605 * (6–8 years after graduation).

The Models and Theories Adopted in Entrepreneurial Intention and Behavior Research

4. Conclusions and Implications

4.1. Theoretical Implications

4.2. Practical Implications

4.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Rank | Count | Centrality | Year | Authors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3 | 0 | 2014 | Fink, Matthias |

| 2 | 3 | 0 | 2014 | Kautonen, Teemu |

| 3 | 3 | 0 | 2023 | Duong, Cong Doanh |

| 4 | 2 | 0 | 2021 | Ashraf, Sheikh Farhan |

| 5 | 2 | 0 | 2019 | Shirokova, Galina |

| 6 | 2 | 0 | 2022 | Botha, Melodi |

| 7 | 1 | 0 | 2019 | Anisimova, Tatiana |

| 8 | 1 | 0 | 2014 | Namatovu-dawa, Rebecca |

| 9 | 1 | 0 | 2017 | Giones, Ferran |

| 10 | 1 | 0 | 2024 | Bashar, Shafiul |

| Ranking | Count | Centrality | Year of First Release | Institutions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3 | 0.01 | 2014 | Anglia Ruskin University |

| 2 | 3 | 0.01 | 2014 | Aalto University |

| 3 | 3 | 0 | 2014 | Johannes Kepler University Linz |

| 4 | 3 | 0 | 2014 | Makerere University |

| 5 | 2 | 0 | 2019 | Saint Petersburg State University |

| 6 | 2 | 0 | 2023 | National Economics University—Vietnam |

| 7 | 2 | 0 | 2024 | Shanghai University of Finance & Economics |

| 8 | 2 | 0 | 2014 | Philipps University Marburg |

| 9 | 2 | 0 | 2024 | Nankai University |

| 10 | 2 | 0 | 2024 | Nanjing University of Finance & Economics |

| Ranking | Count | Centrality | Year of First Release | Countries |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 19 | 0.47 | 2020 | China |

| 2 | 6 | 0 | 2019 | South Africa |

| 3 | 6 | 0.74 | 2014 | England |

| 4 | 6 | 0 | 2019 | Pakistan |

| 5 | 5 | 0.32 | 2017 | Spain |

| 6 | 5 | 0.68 | 2014 | USA |

| 7 | 4 | 0 | 2014 | Finland |

| 8 | 3 | 0 | 2023 | Vietnam |

| 9 | 3 | 0.17 | 2014 | Austria |

| 10 | 3 | 0.09 | 2018 | Portugal |

| Ranking | Freq | Centrality | Year | Cited Journals | IF in 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 56 | 0.48 | 2015 | Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice | 7.8 |

| 2 | 56 | 0.11 | 2014 | Journal of Business Venturing | 7.7 |

| 3 | 48 | 0.17 | 2015 | Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes | 3.4 |

| 4 | 44 | 0.09 | 2017 | Journal of Business Research | 10.5 |

| 5 | 41 | 0.25 | 2017 | International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal | 6.2 |

| 6 | 35 | 0.65 | 2014 | Academy of Management Review | 19.3 |

| 7 | 35 | 0.01 | 2014 | Small Business Economics | 6.2 |

| 8 | 33 | 0.05 | 2014 | Journal of Small Business Management | 5.3 |

| 9 | 30 | 0.1 | 2017 | International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research | 4.5 |

| 10 | 25 | 0.34 | 2015 | Entrepreneurship & Regional Development | 3.3 |

| Ranking | Counts | Centrality | Year | Cited References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 11 | 0.71 | 2020 | Gieure et al. (2020) |

| 2 | 11 | 0.27 | 2014 | Schlaegel and Koenig (2014) |

| 3 | 10 | 0 | 2015 | Kautonen et al. (2015) |

| 4 | 10 | 0.05 | 2015 | Liñán and Fayolle (2015) |

| 5 | 9 | 0.19 | 2020 | Meoli et al. (2020) |

| 6 | 9 | 0.05 | 2016 | Shirokova et al. (2016) |

| 7 | 9 | 0.17 | 2019 | Neneh (2019b) |

| 8 | 8 | 0.04 | 2015 | Van Gelderen et al. (2015) |

| 9 | 7 | 0.09 | 2019 | Bogatyreva et al. (2019) |

| 10 | 7 | 0.05 | 2014 | Fayolle and Liñán (2014) |

| Rank | Count | Centrality | Year | Cited Authors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 51 | 0.63 | 2014 | Ajzen I |

| 2 | 42 | 0.05 | 2016 | Liñán F |

| 3 | 38 | 0.05 | 2015 | Kautonen T |

| 4 | 33 | 0.23 | 2015 | Krueger NF |

| 5 | 22 | 0.47 | 2016 | Fayolle A |

| 6 | 22 | 0 | 2019 | Van Gelderenm |

| 7 | 18 | 0.04 | 2019 | Shirokova G |

| 8 | 16 | 0.42 | 2015 | Bird B |

| 9 | 15 | 0 | 2020 | Fornell C |

| 10 | 15 | 0.04 | 2017 | Schlaegel C |

References

- Abbasianchavari, A., & Moritz, A. (2021). The impact of role models on entrepreneurial intentions and behavior: A review of the literature. Management Review Quarterly, 71, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ataei, P., Ghadermarzi, H., Karimi, H., & Norouzi, A. (2021). The process of adopting entrepreneurial behaviour: Evidence from agriculture students in Iran. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 58(3), 340–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baluku, M. M., Kikooma, J. F., Otto, K., König, C. J., & Bajwa, N. U. H. (2020). Positive psychological attributes and entrepreneurial intention and action: The moderating role of perceived family support. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 546745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belchior, R. F., & Lyons, R. (2021). Explaining entrepreneurial intentions, nascent entrepreneurial behavior and new business creation with social cognitive career theory—A 5-year longitudinal analysis. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 17(4), 1945–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogatyreva, K., Edelman, L. F., Manolova, T. S., Osiyevskyy, O., & Shirokova, G. (2019). When do entrepreneurial intentions lead to actions? The role of national culture. Journal of Business Research, 96, 309–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C. (2006). CiteSpace II: Detecting and visualizing emerging trends and transient patterns in scientific literature. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 57(3), 359–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delanoë-Gueguen, S., & Liñán, F. (2019). A longitudinal analysis of the influence of career motivations on entrepreneurial intention and action. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences/Revue Canadienne des Sciences de l’Administration, 36(4), 527–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delle, E., & Amadu, I. M. (2016). Proactive personality and entrepreneurial intention: Employment status and student level as moderators. Journal of Advance Management and Accounting Research, 3(7), 69–81. [Google Scholar]

- Dolhey, S. (2019). A bibliometric analysis of research on entrepreneurial intentions from 2000 to 2018. Journal of Research in Marketing and Entrepreneurship, 21(2), 180–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayolle, A., & Liñán, F. (2014). The future of research on entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Business Research, 67(5), 663–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1973). Attribution of responsibility: A theoretical note. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 9(2), 148–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, B., Liu, Y., Bajaba, S., Marler, L. E., & Pratt, J. (2018). Examining how the personality, self-efficacy, and anticipatory cognitions of potential entrepreneurs shape their entrepreneurial intentions. Personality and Individual Differences, 125, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibb, A., & Hannon, P. (2006). Towards the entrepreneurial university. International Journal of Entrepreneurship Education, 4(1), 73–110. [Google Scholar]

- Gieure, C., del Mar Benavides-Espinosa, M., & Roig-Dobón, S. (2020). The entrepreneurial process: The link between intentions and behavior. Journal of Business Research, 112, 541–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-López, M. J., Pérez-López, M. C., & Rodríguez-Ariza, L. (2021). From potential to early nascent entrepreneurship: The role of entrepreneurial competencies. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 17(3), 1387–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L. X., & Li, T. (2024). How entrepreneurial implementation intention moves toward subsequent actions: Affordable loss and environmental uncertainty. Chinese Management Studies, 18(3), 734–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y., & Hui, S. C. (2002). Mining a web citation database for author co-citation analysis. Information Processing & Management, 38(4), 491–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hechavarría, D. M. (2016). The impact of culture on national prevalence rates of social and commercial entrepreneurship. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 12(4), 1025–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, D. K., Wiklund, J., Anderson, S. E., & Coffey, B. S. (2016). Entrepreneurial exit intentions and the business-family interface. Journal of Business Venturing, 31(6), 613–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joensuu-Salo, S., Viljamaa, A., & Varamäki, E. (2020). Do intentions ever die? The temporal stability of entrepreneurial intention and link to behavior. Education + Training, 62(3), 325–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Justo, R., DeTienne, D. R., & Sieger, P. (2015). Failure or voluntary exit? Reassessing the female underperformance hypothesis. Journal of Business Venturing, 30(6), 775–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kautonen, T., Van Gelderen, M., & Fink, M. (2015). Robustness of the theory of planned behavior in predicting entrepreneurial intentions and actions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 39(3), 655–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kautonen, T., Van Gelderen, M., & Tornikoski, E. T. (2013). Predicting entrepreneurial behaviour: A test of the theory of planned behaviour. Applied Economics, 45(6), 697–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibler, E., Kautonen, T., & Fink, M. (2014). Regional social legitimacy of entrepreneurship: Implications for entrepreneurial intention and start-up behaviour. Regional Studies, 48(6), 995–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, F., Zhao, L., & Tsai, C.-H. (2020). The relationship between entrepreneurial intention and action: The effects of fear of failure and role model. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krueger, N. (1993). The impact of prior entrepreneurial exposure on perceptions of new venture feasibility and desirability. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 18(1), 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lent, R. W., & Brown, S. D. (2017). Social cognitive career theory in a diverse world: Guest editors’ introduction. Journal of Career Assessment, 25(1), 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C., Murad, M., Shahzad, F., Khan, M. A. S., Ashraf, S. F., & Dogbe, C. S. K. (2020). Entrepreneurial passion to entrepreneurial behavior: Role of entrepreneurial alertness, entrepreneurial self-efficacy and proactive personality. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liñán, F., & Fayolle, A. (2015). A systematic literature review on entrepreneurial intentions: Citation, thematic analyses, and research agenda. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 11(4), 907–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liñán, F., & Rodríguez-Cohard, J. C. (2015). Assessing the stability of graduates’ entrepreneurial intention and exploring its predictive capacity. Academia Revista Latinoamericana de Administración, 28(1), 77–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCain, K. W. (1991). Mapping economics through the journal literature: An experiment in journal cocitation analysis. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 42(4), 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, H., Ma, Z., Zhan, Z., Ning, W., Zuo, H., Wang, J., & Huang, Y. (2022). University students’ successive development from entrepreneurial intention to behavior: The mediating role of commitment and moderating role of family support. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 859210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meoli, A., Fini, R., Sobrero, M., & Wiklund, J. (2020). How entrepreneurial intentions influence entrepreneurial career choices: The moderating influence of social context. Journal of Business Venturing, 35(3), 105982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mothibi, N. H., Malebana, M. J., & Rankhumise, E. M. (2024). Munificent environment factors influencing entrepreneurial intention and behaviour: The moderating role of risk-taking propensity. Administrative Sciences, 14(9), 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murad, M., Othman, S. B., & Kamarudin, M. A. I. B. (2024). Entrepreneurial university support and entrepreneurial career: The directions for university policy to influence students’ entrepreneurial intention and behavior. Journal of Entrepreneurship and Public Policy, 13(3), 441–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neneh, B. N. (2019a). From entrepreneurial alertness to entrepreneurial behavior: The role of trait competitiveness and proactive personality. Personality and Individual Differences, 138, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neneh, B. N. (2019b). From entrepreneurial intentions to behavior: The role of anticipated regret and proactive personality. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 112, 311–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieters, R., & Zeelenberg, M. (2007). A theory of regret regulation 1.1. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 17(1), 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauch, A., & Hulsink, W. (2015). Putting entrepreneurship education where the intention to act lies: An investigation into the impact of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial behavior. Academy of Mmanagement Learning & Education, 14(2), 187–204. [Google Scholar]

- Rohanaraj, T. T. A. (2023). A systematic literature review on the transformation of entrepreneurial intention to entrepreneurial action. Economics-Innovative and Economics Research Journal, 11(S1), 121–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, S. C., Neumeyer, X., Caetano, A., & Liñán, F. (2021). Understanding how and when personal values foster entrepreneurial behavior: A humane perspective. Journal of Small Business Management, 59(3), 373–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlaegel, C., & Koenig, M. (2014). Determinants of entrepreneurial intent: A meta–analytic test and integration of competing models. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 38(2), 291–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapero, A., & Sokol, L. (1982). The social dimensions of entrepreneurship. In D. L. Kent, K. H. Sexton, & C. A. Vesper (Eds.), Encyclopedia of entrepreneurship (pp. 72–90). Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Shinnar, R. S., Hsu, D. K., Powell, B. C., & Zhou, H. (2018). Entrepreneurial intentions and start-ups: Are women or men more likely to enact their intentions? International Small Business Journal, 36(1), 60–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirokova, G., Osiyevskyy, O., & Bogatyreva, K. (2016). Exploring the intention–behavior link in student entrepreneurship: Moderating effects of individual and environmental characteristics. European Management Journal, 34(4), 386–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, H. (1973). Co-citation in the scientific literature: A new measure of the relationship between two documents. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 24(4), 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchman, M. C. (1995). Managing legitimacy: Strategic and institutional approaches. Academy of Management Review, 20(3), 571–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsou, E., Steel, P., & Osiyevskyy, O. (2023). The relationship between entrepreneurial intention and behavior: A meta-analytic review. The International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Gelderen, M., Kautonen, T., & Fink, M. (2015). From entrepreneurial intentions to actions: Self-control and action-related doubt, fear, and aversion. Journal of Business Venturing, 30(5), 655–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Gelderen, M., Kautonen, T., Wincent, J., & Biniari, M. (2018). Implementation intentions in the entrepreneurial process: Concept, empirical findings, and research agenda. Small Business Economics, 51(4), 923–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H., Seibert, S. E., & Hills, G. E. (2005). The mediating role of self-efficacy in the development of entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(6), 1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuang, J., & Sun, H. (2023a). Factors influencing Hong Kong youths’ migration entrepreneurial intention in China’s Greater Bay Area. European Journal of Studies in Management & Business, 27, 40–57. [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang, J., & Sun, H. (2023b). Impact of institutional environment on entrepreneurial intention: The moderating role of entrepreneurship education. The International Journal of Management Education, 21(3), 100863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, J., & Sun, H. (2024). Perceived institutional environment and entrepreneurial behavior: The mediating role of risk-taking propensity and moderating role of human capital factors. Sage Open, 14(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, J., Xiong, R., & Sun, H. (2022). Impact of personality traits on start-up preparation of Hong Kong youths. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 994814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhuang, J.; Sun, H. Systematic Bibliometric Analysis of Entrepreneurial Intention and Behavior Research. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 290. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15080290

Zhuang J, Sun H. Systematic Bibliometric Analysis of Entrepreneurial Intention and Behavior Research. Administrative Sciences. 2025; 15(8):290. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15080290

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhuang, Jiahao, and Hongyi Sun. 2025. "Systematic Bibliometric Analysis of Entrepreneurial Intention and Behavior Research" Administrative Sciences 15, no. 8: 290. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15080290

APA StyleZhuang, J., & Sun, H. (2025). Systematic Bibliometric Analysis of Entrepreneurial Intention and Behavior Research. Administrative Sciences, 15(8), 290. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15080290