Unlocking a Pathway to Fashion Circularity: Insights into Fashion Rental Consumption and Business Practices

Abstract

1. Introduction

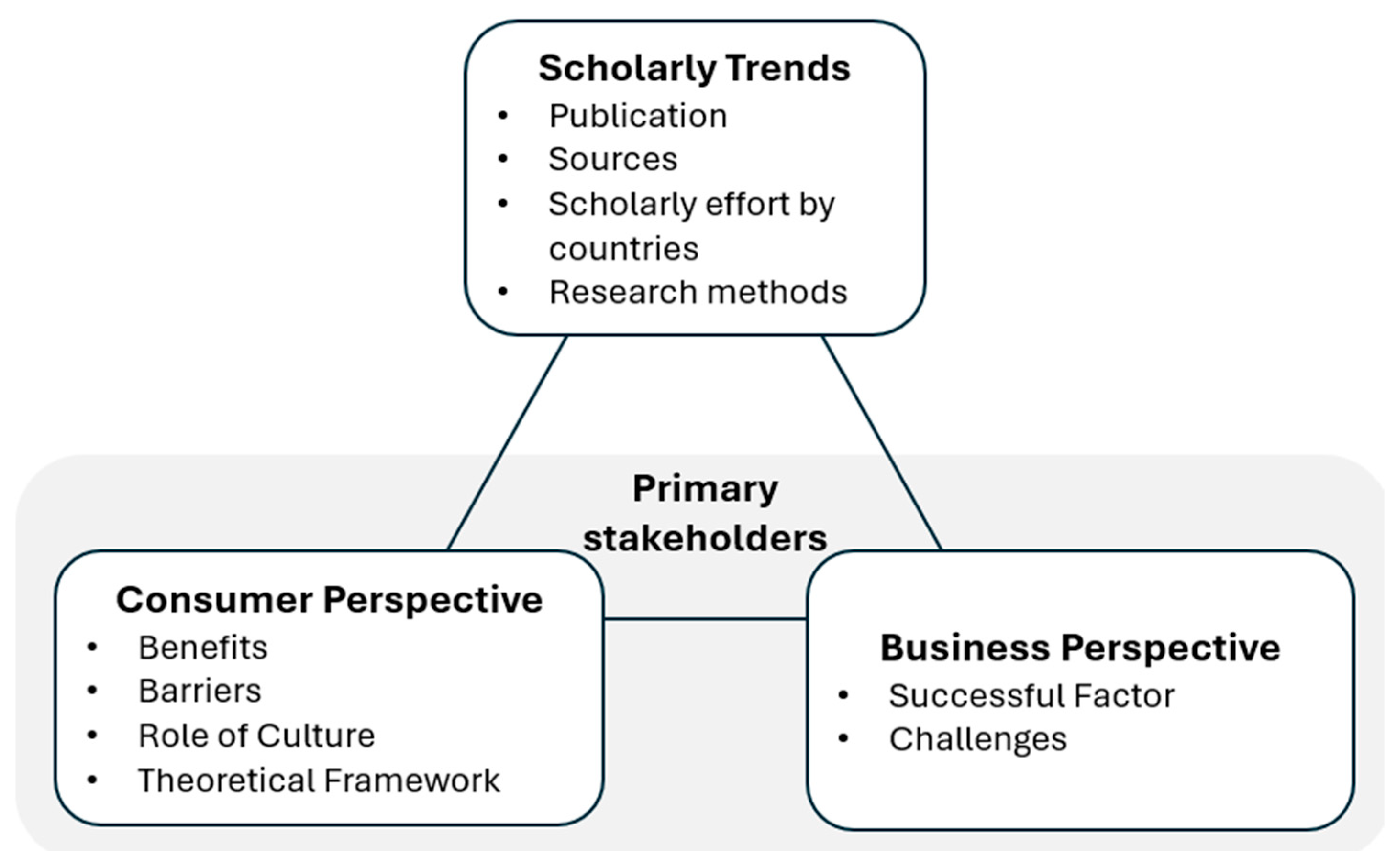

- To synthesize existing research on fashion renting by focusing on

- (a)

- publication trends and scholarly interest, including research focus, journal sources, cultural contexts, research methodologies, and commonly used keywords;

- (b)

- benefits and barriers experienced by consumers engaging in fashion renting and examining how theoretical frameworks shape these behaviors;

- (c)

- challenges and opportunities faced by fashion rental businesses, with attention to market trends, business success factors, and operational difficulties.

- To propose avenues for future scholarly exploration in this field.

2. Fashion Renting

3. Materials and Methods

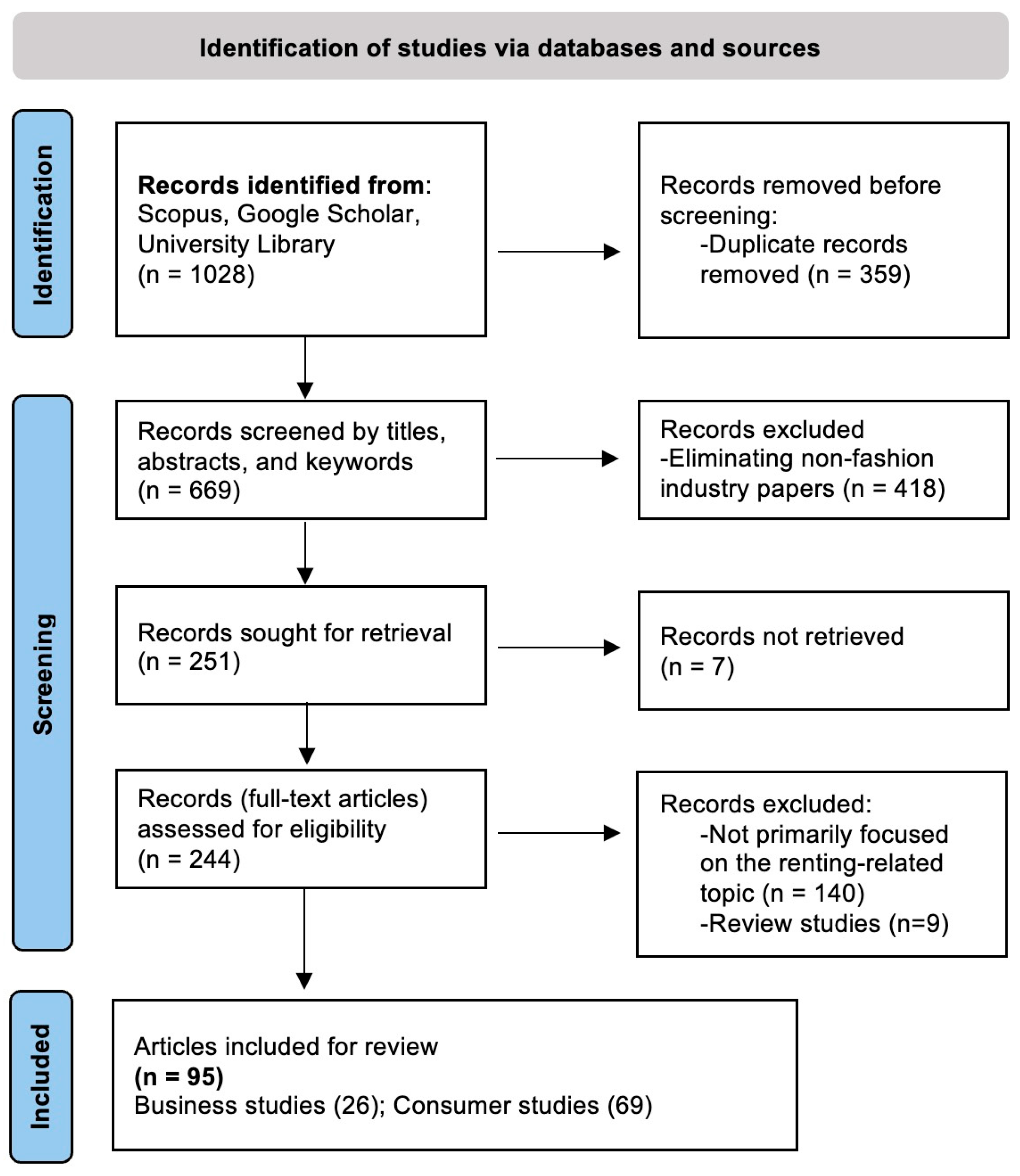

3.1. Literature Collection Procedure

3.2. Dada Analysis

4. Findings

4.1. Descriptive Analysis

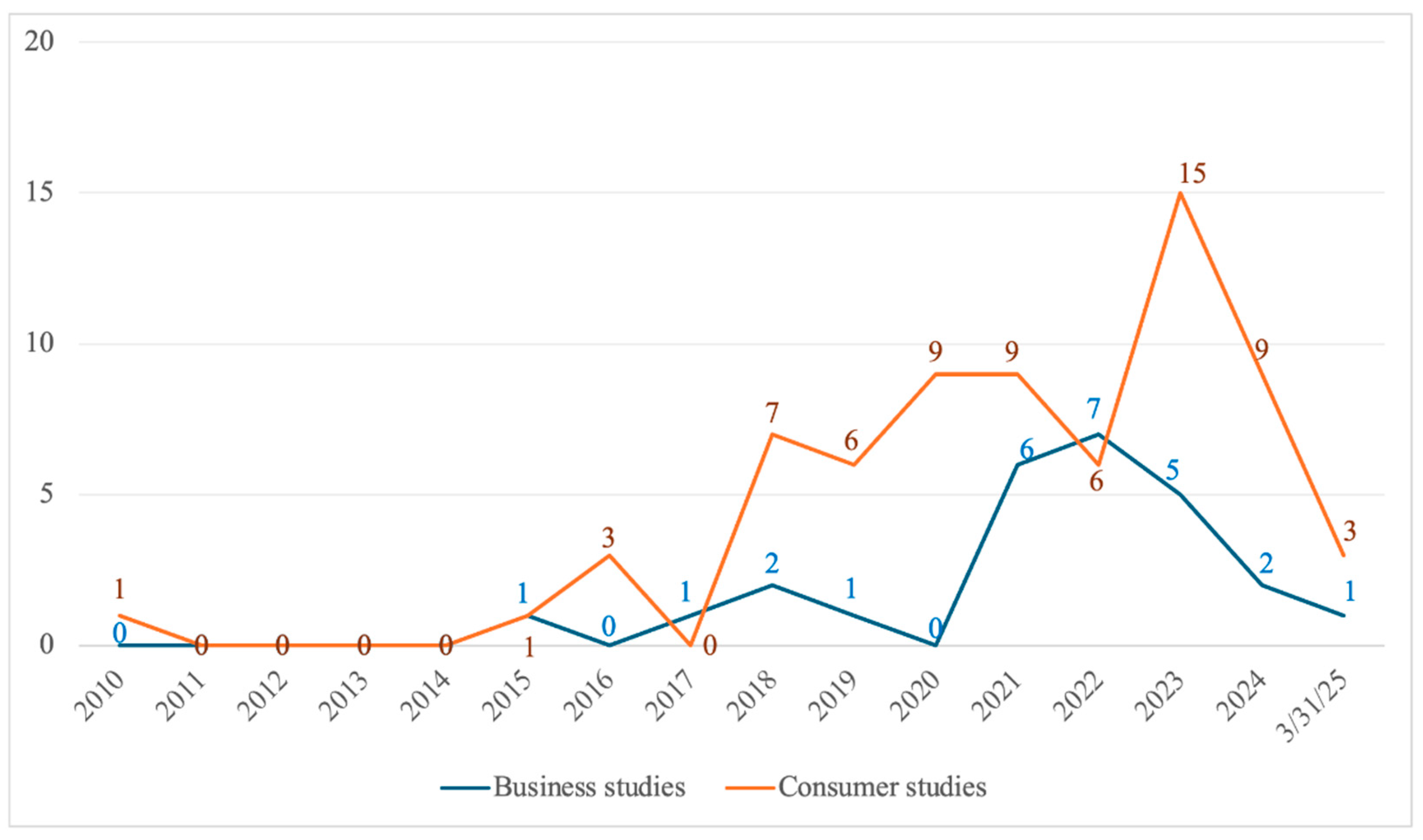

4.1.1. Publication Trend Analysis

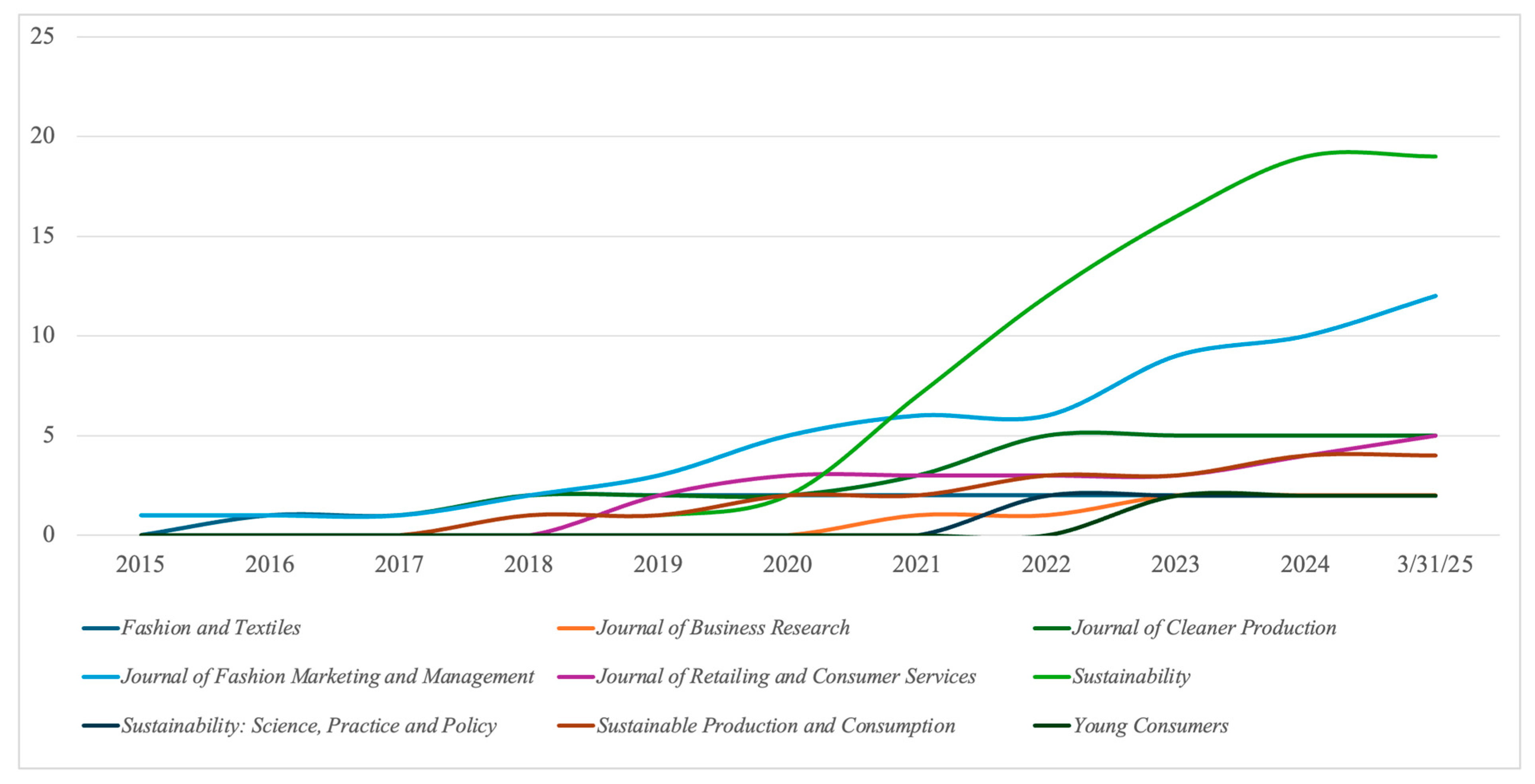

4.1.2. Source Analysis

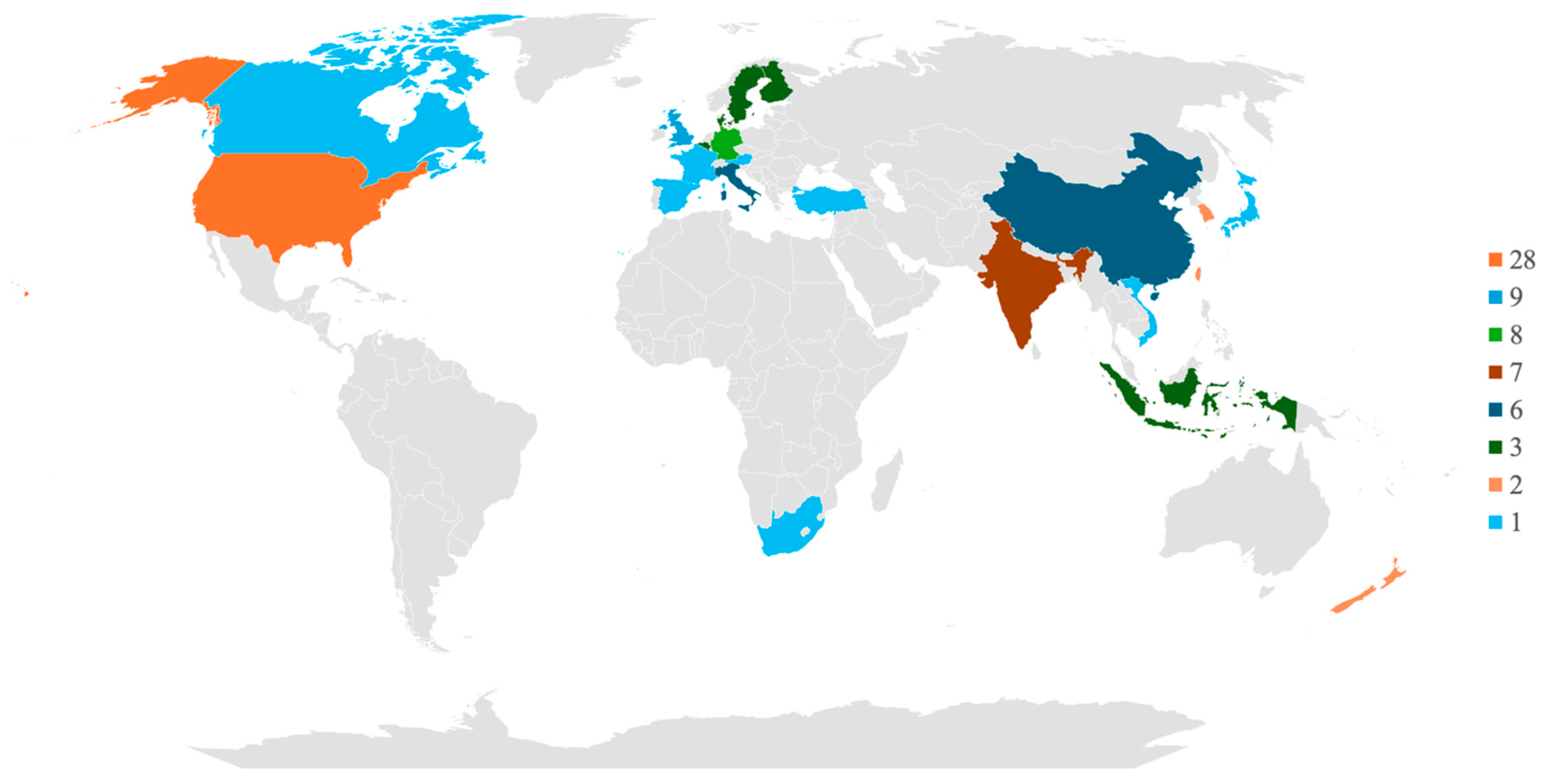

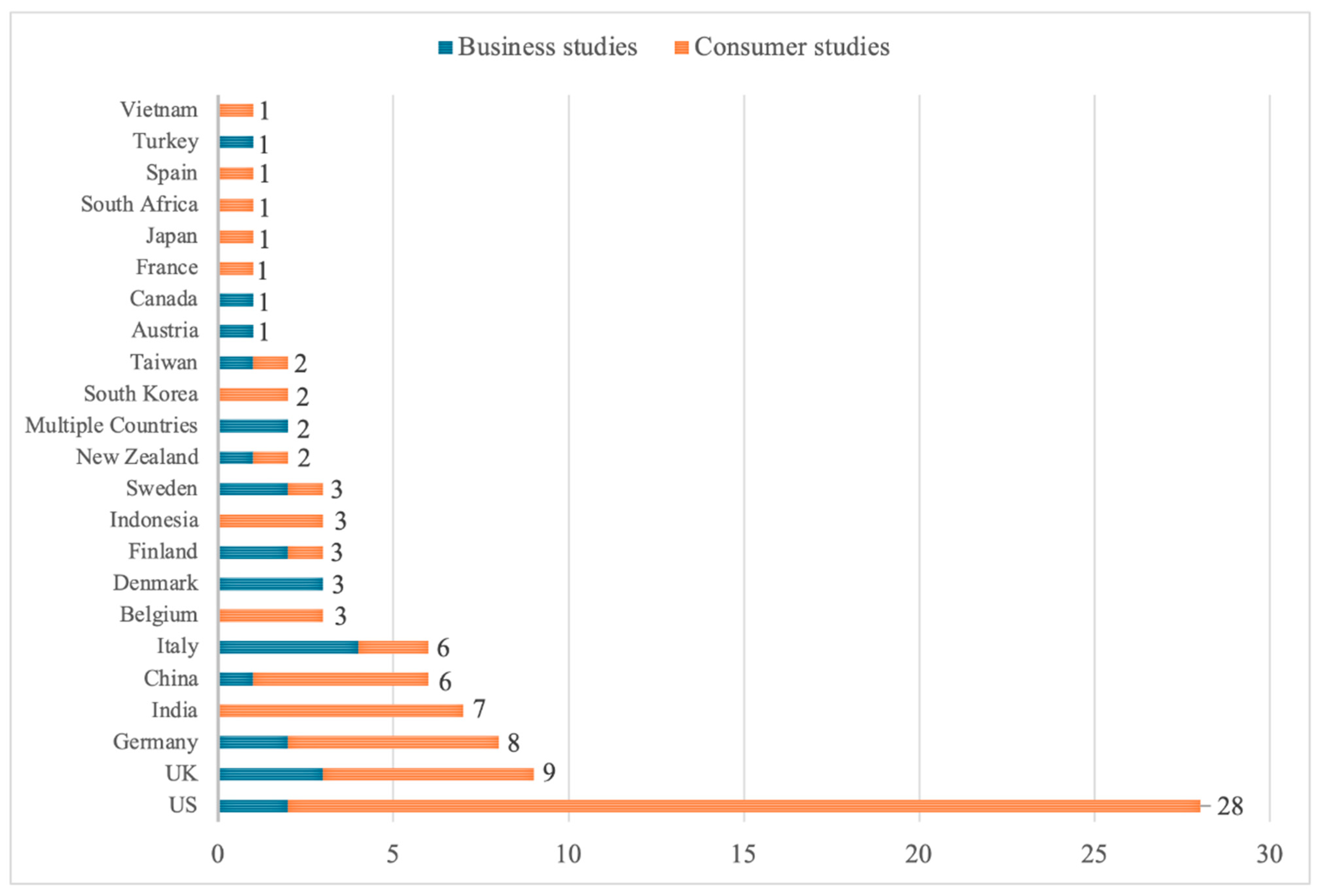

4.1.3. Scientific Coverage by Country

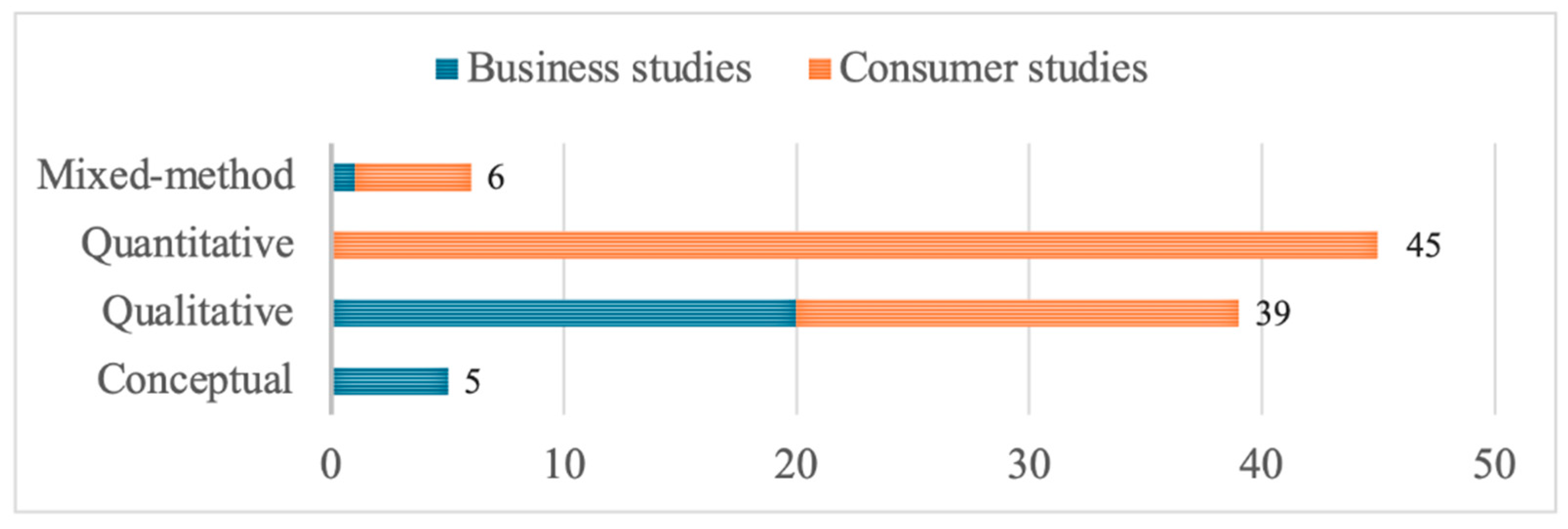

4.1.4. Research Methods

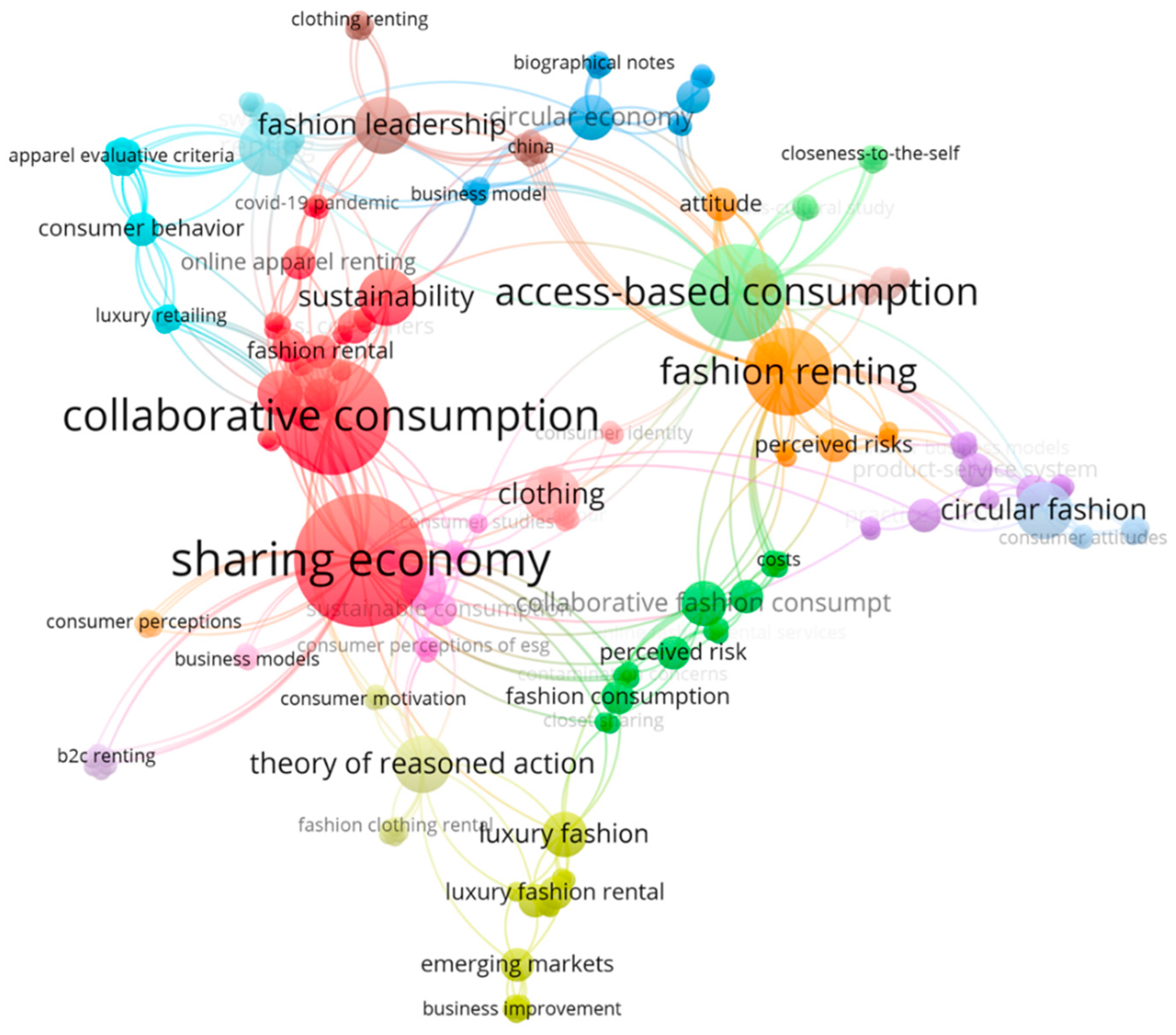

4.1.5. Keywords Analysis

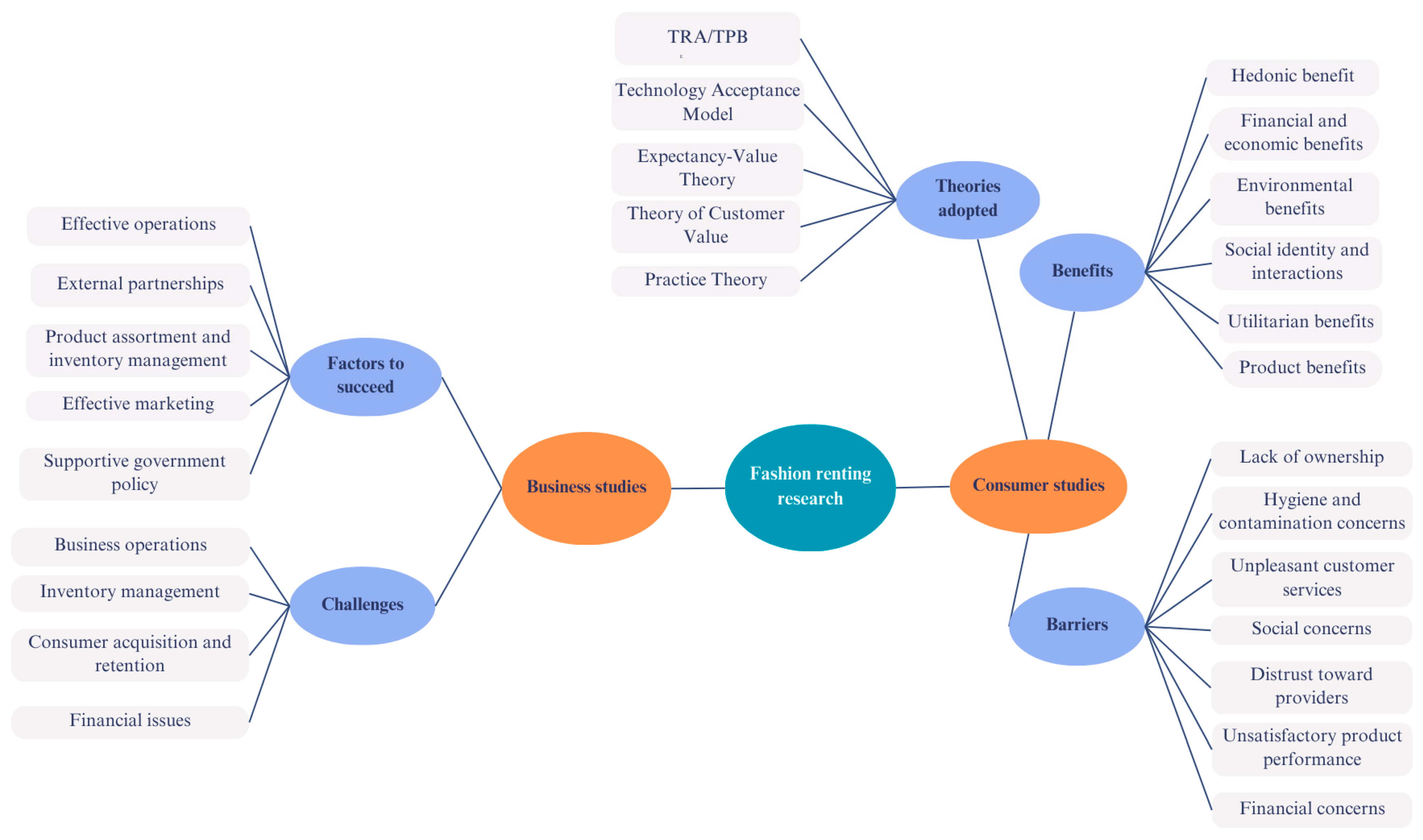

4.2. Thematic Analysis of Consumer Studies

4.2.1. Benefits of Fashion Renting

4.2.2. Barriers to Fashion Renting

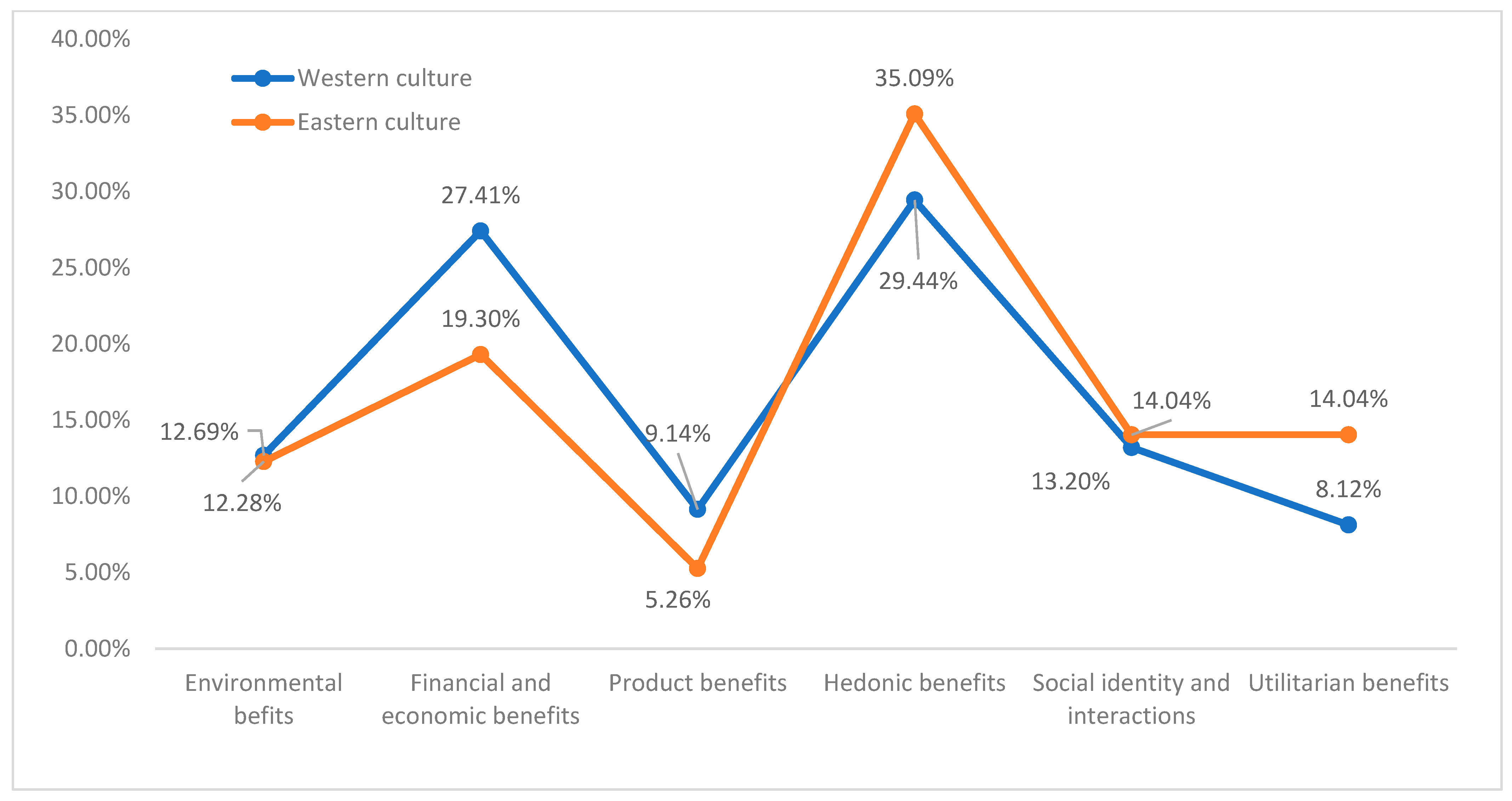

4.2.3. Role of Culture in Fashion Renting

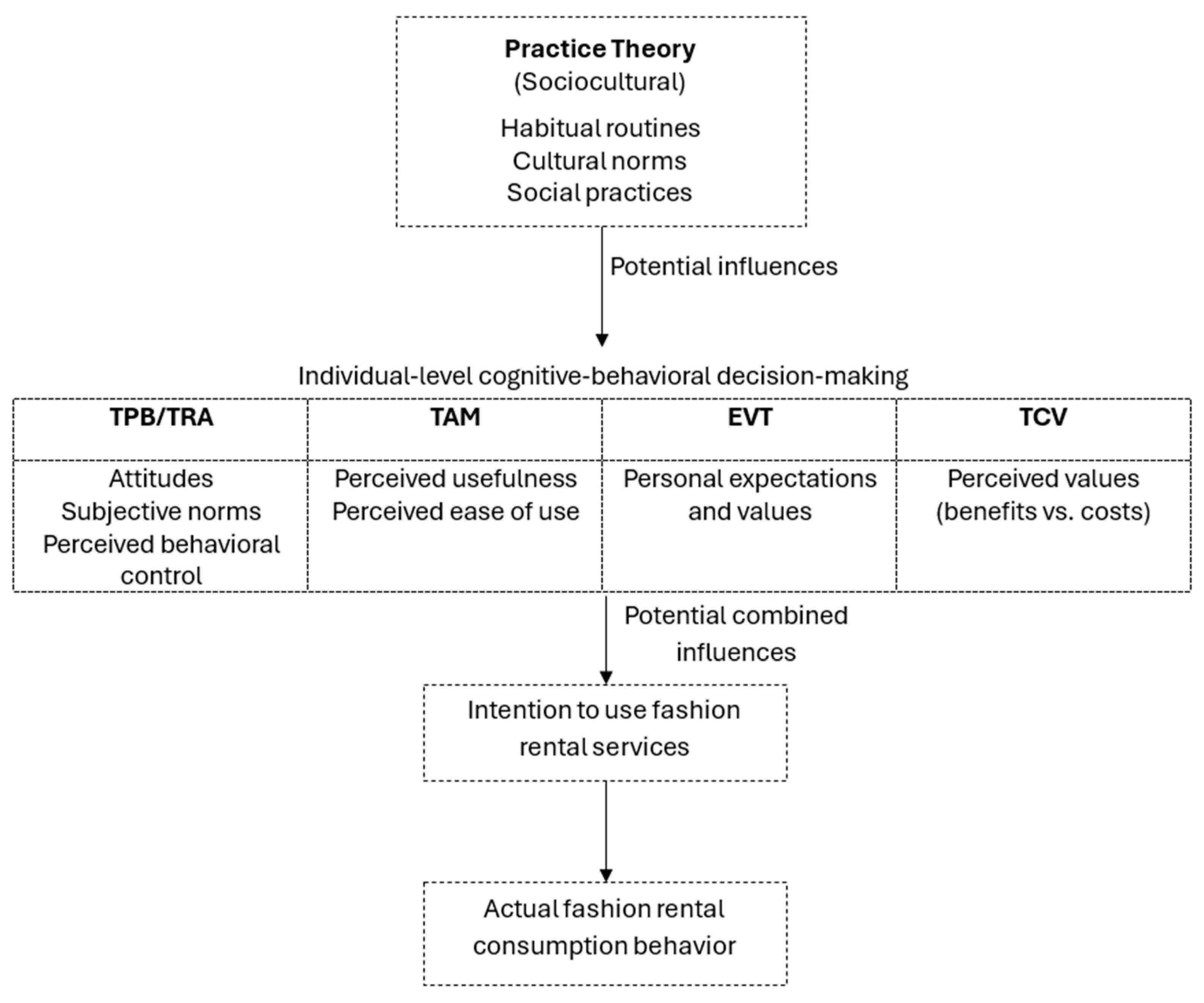

4.2.4. Theoretical Underpinnings of Fashion Renting Consumption

4.3. Thematic Analysis of Fashion Rental Business Studies

4.3.1. The Fashion Rental Market

4.3.2. Success Factors for Fashion Rental Businesses

4.3.3. Challenges Faced by Fashion Rental Businesses

5. Discussion and Implications

6. Conclusions and Limitations

6.1. Research Gaps and Future Trends

6.2. Limitations

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adam, M., Strähle, J., & Freise, M. (2018). Dynamic capabilities of early-stage firms: Exploring the business of renting fashion. Journal of Small Business, 28(2), 49–67. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, B., El-Gohary, H., Khan, R., Gul, M. A., Hussain, A., & Shah, S. M. A. (2024). The influence of behavioral and ESG drivers on consumer intentions for online fashion renting: A pathway toward sustainable consumption in China’s fashion industry. Sustainability, 16(22), 9723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1980). Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Alcayaga, A., Geyerlechner, H., & Hansen, E. G. (2021). IoT-driven reuse business models: The case of Salesianer textile rental services. In Business models for sustainability transitions (pp. 251–271). Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Amasawa, E., Brydges, T., Henninger, C. E., & Kimita, K. (2023). Can rental platforms contribute to more sustainable fashion consumption? Evidence from a mixed-method study. Cleaner and Responsible Consumption, 8, 100103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amasawa, E., Kimita, K., Yoshida, T., & Hirao, M. (2025). Exploring different product-service combinations for sustainable clothing rental service based on consumer preferences and climate change impacts. Scientific Reports, 15(1), 10555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, C. M. J., Kang, J., & Lang, C. (2018). Clothing style confidence: The development and validation of a multidimensional scale to explore product longevity. Journal of Consumer Behavior, 17(1), 553–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, C. M. J., Niinimäki, K., Kujala, S., Karell, E., & Lang, C. (2015). Sustainable product-service systems for clothing: Exploring consumer perceptions of consumption alternatives in Finland. Journal of Cleaner Production, 97, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, C. M. J., Niinimäki, K., Lang, C., & Kujala, S. (2016). A use-oriented clothing economy? Preliminary affirmation for sustainable clothing consumption alternatives. Sustainable Development, 24(1), 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrigo, E. (2021). Digital platforms in fashion rental: A business model analysis. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 26(1), 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrigo, E. (2023). Fashion rental as a new and innovative channel alongside fashion retail. Italian Journal of Management, 41(1), 127–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arruda, H., Silva, E. R., Lessa, M., Proença, D., Jr., & Bartholo, R. (2022). VOSviewer and bibliometrix. Journal of the Medical Library Association, 110(3), 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baek, E., & Oh, G. G. (2021). Diverse values of fashion rental service and contamination concern of consumers. Journal of Business Research, 123, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baek, E., Park, E., & Oh, G.-E. (2023). Understanding the relationship between the material self, belief in brand essence and luxury fashion rental. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 29(1), 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardhi, F., & Eckhardt, G. M. (2017). Liquid consumption. Journal of Consumer Research, 44(3), 582–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battle, A., Ryding, D., & Henninger, C. E. (2018). Access-based consumption: A new business model for luxury and secondhand fashion business? In Vintage luxury fashion (pp. 29–44). Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker-Leifhold, C. V. (2018). The role of values in collaborative fashion consumption—A critical investigation through the lenses of the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Cleaner Production, 199, 781–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker-Leifhold, C. V., & Iran, S. (2018). Collaborative fashion consumption-drivers, barriers and future pathways. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 22(2), 189–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibi, S., Khan, A., Fubing, X., Jianfeng, H., Hussain, S., & Khan, A. N. (2024). Impact of environmental policies, regulations, technologies, and renewable energy on environmental sustainability in China’s textile and fashion industry. Frontiers in Environmental Science, 12, 1496454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodenheimer, M., Schuler, J., & Wilkening, T. (2022). Drivers and barriers to fashion rental for everyday garments: An empirical analysis of a former fashion-rental company. Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy, 18(1), 344–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, S., Jacobs, B., & Taljaard-Swart, H. (2023). I rent, swap or buy second-hand—Comparing antecedents for online collaborative clothing consumption models. International Journal of Fashion Design, Technology and Education, 16(3), 275–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, T., Adesanya, O., Liu, H., Anderson, R., & Zhao, Z. (2023a). Renting than buying apparel: U.S. consumer collaborative consumption for sustainability. Sustainability, 15(6), 4926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, T., Gonzalez, V., Janke, J., Phan, M., & Wojdyla, W. (2023b). Unveiling the soaring trend of fashion rental services: A U.S. consumer perspective. Sustainability, 15(19), 14338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, R. (2021). Fast fashion’s carbon footprint. Carbon literacy project. Available online: https://carbonliteracy.com/fast-fashions-carbon-footprint/ (accessed on 4 May 2025).

- Clube, R. K. M., & Tennant, M. (2020). Exploring garment rental as a sustainable business model in the fashion industry: Does contamination impact the consumption experience? Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 19(4), 359–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coscieme, L., Manshoven, S., Gillabel, J., Grossi, F., & Mortensen, L. F. (2022). A framework of circular business models for fashion and textiles: The role of business-model, technical, and social innovation. Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy, 18(1), 451–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y., & Bai, Y. (2019). Empirical study of Chinese consumers perception-attitude-behavior in clothes rental platform. Journal of Fashion Business, 23(6), 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dovalienė, A., & Salciute, L. (2024). An Investigation of circular fashion: Antecedents of consumer willingness to rent clothes online. Sustainability, 16(9), 3862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, J. S., & Wigfield, A. (2002). Motivational beliefs, values, and goals. Annual Review of Psychology, 53, 109–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Addison-Wesley. [Google Scholar]

- Grilló-Méndez, A. J., Marzo-Navarro, M., & Pedraja-Iglesias, M. (2024). Risks associated by consumers with clothing rental: Barriers to being adopted. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 28(6), 1135–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzzetti, A., Crespi, R., & Belvedere, V. (2021). “Please don’t buy!”: Consumers attitude to alternative luxury consumption. Strategic Change, 30(1), 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyde, C., & McNeill, L. S. (2021). Fashion rental: Smart business or ethical folly? Sustainability, 13(16), 8888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helinski, C., & Schewe, G. (2022). The influence of consumer preferences and perceived benefits in the context of B2C fashion renting intentions of young women. Sustainability, 14(15), 9407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henninger, C. E., Amasawa, E., Brydges, T., & Piontek, F. M. (2022). My wardrobe in the cloud—An international comparison of fashion rental. In Handbook of research on the platform economy and the evolution of E-commerce (pp. 153–175). IGI Global. [Google Scholar]

- Herold, P. I., & Prokop, D. (2023). Is fast fashion finally out of season? Rental clothing schemes as a sustainable and affordable alternative to fast fashion. Geoforum, 146, 103873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture’s consequences. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, S., Henninger, C. E., Boardman, R., & Ryding, D. (2019). Challenging current fashion business models: Entrepreneurship through access-based consumption in the second-hand luxury garment sector within a circular economy. In Sustainable luxury: Cases on circular economy and entrepreneurship (pp. 39–54). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z. H., Li, Q., Chen, X. J., & Wang, Y. F. (2014). Sustainable rent-based closed-loop supply chain for fashion products. Sustainability, 6(10), 7063–7088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iran, S., & Schrader, U. (2017). Collaborative fashion consumption and its environmental effects. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 21(4), 468–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, R., Jain, K., Behl, A., Pereira, V., Del Giudice, M., & Vrontis, D. (2022). Mainstreaming fashion rental consumption: A systematic and thematic review of literature. Journal of Business Research, 139, 1525–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, R., Singh, G., Jain, S., & Jain, K. (2023). Gen Xers: Perceived barriers and motivators to fashion renting from the Indian cultural context. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 22(5), 1128–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jham, V., Mishra, S., & Jain, S. (2023). Hedonic value and collaborative luxury consumption: A moderated mediation model. Paradigm: A Management Research Journal, 27(2), 136–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, E., & Plepys, A. (2021). Product-service systems and sustainability: Analysing the environmental impacts of rental clothing. Sustainability, 13(4), 2118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kala, D., & Chaubey, D. S. (2024). Exploring the determinants of fashion clothing rental consumption among young Indians using the extended theory of reasoned action. Global Knowledge, Memory and Communication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpova, E. E., Jestratijevic, I., Lee, J., & Wu, J. (2022). An ethnographic study of collaborative fashion consumption: The case of temporary clothing swapping. Sustainability, 14(5), 2499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khitous, F., Urbinati, A., & Verleye, K. (2022). Product-service systems: A customer engagement perspective in the fashion industry. Journal of Cleaner Production, 336, 130394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J., Yang, K., & Kim, B. (2013). Online retailer reputation and consumer response: Examining cross-cultural differences. International Journal of Retail and Distribution Management, 41(9), 688–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, N. L., & Jin, B. E. (2020). Addressing the contamination issue in collaborative consumption of fashion: Does ownership type of shared goods matter? Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 25(2), 242–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirezli, Ö., & Tuzcu, M. (2024). A touch of circular economy on luxury fashion industry: Analyzing the second-hand luxury fashion rental platform in Turkey. In Transition to the circular economy model (pp. 57–74). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laitala, K., & Klepp, I. G. K. (2018). Motivations for and against second-hand clothing acquisition. Clothing Cultures, 5(2), 247–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, C. (2018). Perceived risks and enjoyment of access-based consumption: Identifying barriers and motivations to fashion renting. Fashion and Textiles, 5(1), 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, C., Armstrong, C. M., & Liu, C. (2016). Creativity and sustainable apparel retail models: Does consumers’ tendency for creative choice counter-conformity matter in sustainability? Fashion and Textiles, 3(1), 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, C., & Joyner Armstrong, C. M. (2018a). Collaborative consumption: The influence of fashion leadership, need for uniqueness, and materialism on female consumers’ adoption of clothing renting and swapping. Sustainable Production and Consumption, 13, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, C., & Joyner Armstrong, C. M. (2018b). Fashion leadership and intention toward clothing product-service retail models. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 22(4), 571–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, C., Li, M., & Zhao, L. (2020). Understanding consumers’ online fashion renting experiences: A text-mining approach. Sustainable Production and Consumption, 21, 132–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, C., Seo, S., & Liu, C. (2019). Motivations and obstacles for fashion renting: A cross-cultural comparison. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 23(4), 519–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, C., & Wei, B. (2019). Convert one outfit to more looks: Factors influencing young female college consumers’ intention to purchase transformable apparel. Fashion and Textiles, 6(1), 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, C., & Zhang, R. (2024). Motivators of circular fashion: The antecedents of Chinese consumers’ fashion renting intentions. Sustainability, 16(5), 2184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laudien, S. M., Martínez, J. M. G., & Martín, J. M. M. (2023). Business models based on sharing fashion and accessories: Qualitative-empirical insights into a new type of sharing economy business models. Journal of Business Research, 157, 113636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laukkanen, M., & Tura, N. (2022). Sustainable value propositions and customer perceived value: Clothing library case. Journal of Cleaner Production, 378, 134321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, S. J., Gleim, M. R., Perren, R., & Hwang, J. (2016). Freedom from ownership: An exploration of access-based consumption. Journal of Business Research, 69(8), 2615–2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, O., Lee, Y., & Lee, H. (2021). Investigation of fashion sharing platform for sustainable economy—Korean and international fashion websites before and after COVID-19. Sustainability, 13(17), 9782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S. E., Jung, H. J., & Lee, K.-H. (2021). Motivating collaborative consumption in fashion: Consumer benefits, perceived risks, service trust, and usage intention of online fashion rental services. Sustainability, 13(4), 1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S. H., & Huang, R. (2020a). Consumer responses to online fashion renting: Exploring the role of cultural differences. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 49(2), 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S. H., & Huang, R. (2020b). Exploring the motives for online fashion renting: Insights from social retailing to sustainability. Sustainability, 12(18), 7610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S. H. N., & Chow, P.-S. (2020). Investigating consumer attitudes and intentions toward online fashion renting retailing. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 52, 101892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCoy, L., & Chi, T. (2022). Collaborative consumption: A study of sustainability presentation in fashion rental platforms. Sustainability, 14(14), 8537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCoy, L., Wang, Y.-T., & Chi, T. (2021). Why is collaborative apparel consumption gaining popularity? An empirical study of US Gen Z consumers. Sustainability, 13(15), 8360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGowan, K., & Conlan, E. (2023). Exploring the current and future potential of fashion rental and resale in the UK: A case study on ACS Clothing. In Pioneering new perspectives in the fashion industry: Disruption, diversity and sustainable innovation. Emerald Insight. [Google Scholar]

- McKinney, E., & Shin, E. (2016). Exploring criteria consumers use in evaluating their online formal wear rental experience. Clothing and Textiles Research Journal, 34(4), 272–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeill, L., & Venter, B. (2019). Identity, self-concept and young women’s engagement with collaborative, sustainable fashion consumption models. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 43(4), 368–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWilliam, A., & Siegel, D. S. (2011). Creating and capturing value: Strategic corporate social responsibility, resource-based theory, and sustainable competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 37(5), 1480–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S., Jain, S., & Jham, V. (2020). Luxury rental purchase intention among millennials—A cross-national study. Thunderbird International Business Review, 63(4), 503–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mordor Intelligence. (2025). Online clothing rental market size–Industry report on share, growth trends & forecasts analysis (2025–2030). Available online: https://www.mordorintelligence.com/industry-reports/online-clothing-rental-market (accessed on 31 March 2025).

- Moeller, S., & Wittkowski, K. (2010). The burdens of ownership: Reasons for preferring renting. Managing Service Quality: An International Journal, 20(2), 176–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, X., & Li, C. (2021). Research on clothing rental model under sharing economy. E3S Web of Conferences, 253, 01075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukendi, A., & Henninger, C. E. (2020). Exploring the spectrum of fashion rental. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 24(3), 455–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Multala, B., Wagner, J., & Wang, Y. (2022). Durability standards and clothing libraries for strengthening sustainable clothing markets. Ecological Economics, 194, 107358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muylaert, C., & Maréchal, K. (2022). Understanding consumer lock-in mechanisms towards clothing libraries: A practice-based analysis coupled with the multi-level perspective. Sustainable Production and Consumption, 34, 342–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muylaert, C., Tunn, V. S. C., & Maréchal, K. (2024). On the attractiveness of clothing libraries for women: Investigating the adoption of product-service systems from a practice-based perspective. Sustainable Production and Consumption, 45, 359–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myin, M. T., Su, J., Wu, H., & Shen, H. (2022). Investigating the determinants of using clothing subscription rental services: A perspective from Chinese young consumers. Young Consumers, 24(1), 95–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neerattiparambil, N. N., & Belli, S. M. (2020). Why rent a dress?: A Study on renting intention for fashion clothing products. Indian Journal of Marketing, 50(2), 20–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niinimäki, K. (2010). Eco-clothing, consumer identity and ideology. Sustainable Development, 18(3), 150–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noe, H., & Hyun, J. (2023). Why do and why don’t consumers use fashion rental services? A consumption value perspective. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 28(3), 566–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omri, A., Frikha, M. A., & Bouraoui, M. A. (2015). An empirical investigation of factors affecting small business success. Journal of Management Development, 34(9), 1073–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantano, E., & Stylos, N. (2020). The Cinderella moment: Exploring consumers’ motivations to engage with renting as collaborative luxury consumption mode. Psychology & Marketing, 37(5), 740–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H., & Joyner Armstrong, C. M. (2019a). Is money the biggest driver? Uncovering motives for engaging in online collaborative consumption retail models for apparel. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 51, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H., & Joyner Armstrong, C. M. (2019b). Will “no-ownership” work for apparel?: Implications for apparel retailers. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 47, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H., & Lee, M.-Y. (2022). The two-sided effect of the COVID-19 Pandemic on online apparel renting. Sustainability, 14(24), 16771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattberg, T. J. (2009). The East-West dichotomy: The conceptual contrast between Eastern and Western cultures. LoD Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen, E. R. G., & Netter, S. (2015). Collaborative consumption: Business model opportunities and barriers for fashion libraries. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 19(3), 258–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perren, R., & Grauerholz, L. (2015). Collaborative consumption. International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, 4(2), 139–144. [Google Scholar]

- Petänen, P., Tuovila, H., & Heikkilä, P. (2024). Strategic marketing of sustainable fashion: Exploring approaches and contradictions in the positioning of fashion rental. Cleaner Production Letters, 7, 100075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, T. B., & Riisberg, V. (2017). Cultivating user-ship? Developing a circular system for the acquisition and use of baby clothing. Fashion Practice, 9(2), 214–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, H. T., Hoang, K. T., Nguyen, T. T., Do, P. H., & Mar, M. T. C. (2021). Sharing economy: Generation Z’s intention toward online fashion rental in Vietnam. Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business, 8(3), 997–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramtiyal, B., Johari, S., Vijayvargy, L., & Prakash, S. (2023). The impact of marketing mix on the adoption of clothes rental and swapping in collaborative consumption. Journal of Global Operations and Strategic Sourcing, 17(1), 28–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rese, A., & Baier, D. (2025). Rental clothing box subscription: The importance of sustainable fashion labels. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 83, 104153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricchiardi, A., & Bugnotto, G. (2019). Customized servitization as an innovative approach for renting service in the fashion industry. CERN Idea Square Journal of Experimental Innovation, 3(1), 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritch, E. L., & Siddiqui, N. (2023). Fashioning the circular economy with disruptive marketing tactics mimicking fast fashion’s exploitation of social capital: A case study exploring the innovative fashion rental business model “wardrobe”. Sustainability, 15(19), 14532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, L. M., Weijo, H. A., Kerkelä, I., Price, L. L., Giesler, M., & Arsel, Z. (2023). Consumer desires and the fluctuating balance between liquid and solid consumption: The case of Finnish clothing libraries. Journal of Consumer Research, 50(4), 826–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, Y., Xu, Y., & Lee, H. (2022). Consumer motivations for luxury fashion rental: A second-order factor analysis approach. Sustainability, 14(12), 7475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savelli, E., Francioni, B., Curina, I., & Cioppi, M. (2024). Promoting access-based consumption practices through fashion renting: Evidence from Italy. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 41(1), 61–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefers, T., Lawson, S. J., & Kukar-Kinney, M. (2016). How the burdens of ownership promote consumer usage of access-based services. Marketing Letters, 27(3), 569–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, S., Watchravesringkan, K., Swamy, U., & Lang, C. (2023). Investigating expectancy values in online apparel rental during and after the COVID-19 Pandemic: Moderating effects of fashion leadership. Sustainability, 15(17), 12892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setiawan, M., Setiawan, S., Darisman, A., & Rahmah, R. (2022, December 8–9). Motivation and drivers for online fashion rental: Study by social networking sites in Indonesia. 2022 Seventh International Conference on Informatics and Computing (ICIC) (pp. 1–6), Denpasar, Bali, Indonesia. [Google Scholar]

- Shrivastava, A., Jain, G., Kamble, S. S., & Belhadi, A. (2021). Sustainability through online renting clothing: Circular fashion fueled by Instagram micro-celebrities. Journal of Cleaner Production, 278, 123772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J., & Bansal, S. (2024). The impact of the fashion industry on the climate and ecology. World Journal of Advanced Research and Reviews, 21(1), 210–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S., & Wu, J. (2024). Comparing material and experiential framing in access-based fashion consumption and its influence on consumer happiness. Journal of Marketing Management, 40(9–10), 743–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sörum, N., & Gianneschi, M. (2023). The role of access-based apparel in processes of consumer identity construction. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 27(1), 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. (2024). Fashion-worldwide. Available online: https://www.statista.com/outlook/emo/fashion/worldwide (accessed on 5 April 2025).

- Themadjaja, T. L., & Gunadi, W. (2023). Factors influencing Indonesian consumers’ behaviour in fashion renting. European Journal of Business and Management Research, 8(5), 122–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tri, B. W., Imam, S. A., & Irman, H. (2021). Factors affecting the intention to use fashion-renting platform. Russian Journal of Agricultural and Socio-Economic Sciences, 110(2), 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, J.-C., & Hu, C.-L. (2018). A study on the factors affecting consumers’ willingness to accept clothing rentals. Sustainability, 10(11), 4139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, I., Cacho-Elizondob, S., Damayc, C., & Loussaïef, L. (2024). A practice theory perspective on apparel sharing consumption models exploring new paths of consumption in France and Mexico. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 77, 103626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, R. L., & Gaur, S. S. (2021). Luxury for hire: Motivations to use closet sharing. Australasian Marketing Journal, 29(4), 306–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VOSviewer. (2025). VOSviewer manual. Available online: https://www.vosviewer.com/getting-started (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Wänström, A. A., Hjelmgren, D., Landqvist, M., & Lind, F. (2025). Exploring renting models for clothing items—Resource interaction for value creation. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X., & Wang, C. (2024). Contamination concerns and face consciousness in fashion-sharing services. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 29(2), 269–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerberg, C., & Martinez, L. F. (2023). Young German consumers’ perspectives of rental fashion platforms. Young Consumers, 24(3), 309–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V. A. (1988). Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: A means-end model and synthesis of evidence. Journal of Marketing, 52(3), 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., & Liou, S. (2021, December 16–17). Wardrobe rentals: A study of the fashion industry under sharing economy. 2021 9th International Conference on Orange Technology (ICOT) (pp. 1–4), Tainan, Taiwan. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lang, C.; Seo, S.; Liu, S. Unlocking a Pathway to Fashion Circularity: Insights into Fashion Rental Consumption and Business Practices. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 288. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15080288

Lang C, Seo S, Liu S. Unlocking a Pathway to Fashion Circularity: Insights into Fashion Rental Consumption and Business Practices. Administrative Sciences. 2025; 15(8):288. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15080288

Chicago/Turabian StyleLang, Chunmin, Sukyung Seo, and Sujun Liu. 2025. "Unlocking a Pathway to Fashion Circularity: Insights into Fashion Rental Consumption and Business Practices" Administrative Sciences 15, no. 8: 288. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15080288

APA StyleLang, C., Seo, S., & Liu, S. (2025). Unlocking a Pathway to Fashion Circularity: Insights into Fashion Rental Consumption and Business Practices. Administrative Sciences, 15(8), 288. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15080288