Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has significantly altered consumer habits, particularly in relation to food choices. In this context, plant-based diets have gained prominence, driven by health, environmental, and ethical considerations. This study investigates the primary motivational and inhibitory factors influencing the consumption of plant-based foods among residents of the Galicia–Northern Portugal Euroregion. Utilizing the Theory of Reasoned Action, an extended model was proposed and tested through a quantitative survey. A total of 214 valid responses were collected via an online questionnaire distributed in Portuguese and Spanish. Linear regression analysis revealed that health awareness, animal welfare, and environmental concern significantly shape positive attitudes, which subsequently affect the intention to consume plant-based foods. Additionally, perceived barriers—such as lack of taste and insufficient information—were found to negatively influence intention. These findings contribute to the consumer behavior literature and provide strategic insights for stakeholders aiming to promote more sustainable dietary patterns in culturally connected cross-border regions.

1. Introduction

The transition to sustainable food systems constitutes a critical global imperative, demanding that individuals reconcile personal preferences with ethical, environmental, and health considerations. Although plant-based diets have emerged as a promising pathway toward more responsible consumption, the psychosocial processes underlying their adoption remain inadequately understood, particularly in regions where culinary traditions constitute a core aspect of cultural identity (Kapelari et al., 2020). Traditional behavioural models, notably the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA; Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980), explain how attitudes and subjective norms shape intentions, yet they fail to capture the complex trade-offs among ethical values, ecological concerns, and identity negotiations inherent in sustainable food choices (Sheeran & Webb, 2016). This limitation is underscored by the persistent intention–behavior gap in sustainable consumption, which highlights the necessity of extending cognitive frameworks to integrate contextual inhibitors and value-based antecedents (Ajzen, 1991; Dorce et al., 2021).

Cultural identity’s role in dietary change remains contested. Whereas conventional scholarship often portrays food heritage as an obstacle to innovation, emerging evidence indicates that culinary traditions can catalyze sustainability when reframed as adaptable cultural assets (Kapelari et al., 2020). The COVID-19 pandemic has further disrupted consumption patterns and heightened health consciousness, offering a unique opportunity to examine how ethical, environmental, and health motivations interact with cultural narratives and practical constraints to influence plant-based food adoption (Zwanka & Buff, 2020).

The human population, especially in developed and so-called Western societies, lives in a fast-processing mode, increasingly online, where the time to make choices about a product, service, or brand is increasingly limited (Scholz et al., 2018). Consumption has moved from a paradigm of having many purchasing options to having too many, which is associated with a higher level of stress and a clear reduction in focus and attention when making decisions (Mick et al., 2004). The COVID-19 pandemic has led to a reconfiguration of consumer priorities, placing health, sustainability, and ethical concerns at the forefront of decision-making (Bausch et al., 2021; Sheth, 2020). Several studies (Casas et al., 2022; Sachdeva et al., 2013; Harris et al., 2023) show that consumers have shifted to healthier diets, including an increase in the consumption of fruits and vegetables. This change presents an opportunity to analyze the adoption of plant-based diets as a manifestation of this new responsible consumption.

This study addresses these theoretical and empirical lacunae by examining plant-based food consumption in the Galicia–Northern Portugal Euroregion through an extended TRA framework. We integrate value-based antecedents of attitude (health consciousness, environmental concern, and animal welfare) and contextual barriers of price, taste, information, availability, and cultural aspects to explain behavioural intentions. The Euroregion’s shared Atlantic Diet heritage and cross-border cultural proximity provide a natural laboratory for exploring the co-evolution of food heritage and dietary innovation (Lorenzo et al., 2022). Our contributions are threefold: we extend the TRA by incorporating ethical and environmental antecedents to reflect the multidimensional nature of sustainable food choices; we theorize cultural identity as both a potential barrier and facilitator of dietary change; and we offer empirical insights into post-pandemic consumption patterns in a culturally rich European region, with implications for theory and practice.

The relevance of this research lies in its cross-border approach, addressing a culturally similar yet administratively distinct population. The originality stems from applying the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) to a Euroregion context during a post-pandemic period, extending the model with specific barriers and ethical drivers.

The target of this research is the population living in the Euroregion Galicia–Northern Portugal. This European region is located in the northwest of the Iberian Peninsula and is made up of two regions in two countries: Galicia (Spain) and the northern region of Portugal. The territory formed by the two regions covers a total area of 51,000 km2 (Galicia 29,575 and Northern Portugal 21,284), has a population of 6.4 million inhabitants (Galicia 2,796,089 and Northern Portugal 3,745,439), and is made up of the provinces of A Coruña, Lugo, Ourense, and Pontevedra on the Galician side and the sub-regions of Minho-Lima, Cávado, Ave, Grande Porto, Tâmega, Entre Douro e Vouga, Douro and Trás-os-Montes, and Alto Douro on the Portuguese side (Cardoso et al., 2023). In addition to the convenience factor and the plurinational perspective of this study, another reason for choosing this region is the strong cultural connection between the Galician and Portuguese people, specifically when commonalities are found in food such as the Atlantic Diet (Lorenzo et al., 2022). According to Lorenzo et al. (2022), the Atlantic Diet is very similar to the Mediterranean diet, which is very popular in southern European countries. Both are based mainly on plant products and include healthy ingredients of animal origin, such as fresh fish, lean meats, eggs, and dairy products. However, the Atlantic Diet focuses on the sea and recommends a moderate consumption of lean meat once a week and fish or seafood four times a week.

This article is structured in five sections. The first section introduces the topic, contextualizes the global paradigm of plant-based food consumption, with a special emphasis on the Galicia–Northern Portugal Euroregion, and addresses the process, methodology, relevance, objectives, and structure. The second section provides a theoretical framework on plant-based foods, types of diets, concepts and theories on attitude, consumer behavior, the purchasing decision process, as well as all the variables and respective hypotheses envisaged in this research. The third section focuses on the methodology, beginning with the conceptual model and hypotheses, followed by a detailed explanation of the quantitative method chosen for data collection. The fourth section presents the analysis and a discussion of the results, and finally, the fifth outlines the main conclusions and implications of this study.

2. Theoretical Background

This section seeks to describe the basic theoretical notions of this research. The starting point is the definition of the concept of plant-based foods, which then allows us to explain the various consumer typologies categorized by the type of diet. In order to frame the variable under study, “attitude towards the consumption of plant-based foods and consequent purchase intention”, the concepts of attitude, consumer behavior, the purchase decision process, and the theoretical foundation based on the Theory of Reasoned Action are reviewed. The attitudes and barriers to consumption are also explored as variables of the topic under study, and they are associated with the respective hypotheses individually. For the purposes of this research, plant-based foods are defined as exclusively plant-based foods that do not contain any ingredient of animal origin, including honey, eggs, milk, or derivatives. For further visual identification, it is important to mention that in the EU, all packaged plant-based foods, which are vegan in essence, are certified and therefore display the VLabel symbol.

2.1. Plant-Based Foods

Plant-based foods are ones that can be classified (Fardet, 2017) as follows: fruits, vegetables, legumes, grains, nuts, and seeds; processed foods such as breads, pasta, breakfast cereals, and cooked and fermented vegetables; fruit purees, juices, and jellies; and derived ingredients such as vegetable oils, sugars, and some herbs and spices. In recent years, plant-based foods have become very popular, not to make up an exclusively plant-based diet, but as substitutes for meat, butter, milk, and eggs (Jensen, 2020). The concept of a substitute or alternative to meat as a source of protein has origins dating back to China during the Han Dynasty (206 BC–220 AD), and among the most traditional options are tempeh, tofu, and seitan (Bakhsh et al., 2021). As for milk, cheese, and yogurt substitutes, the most common are made from almonds, soy, coconut, rice, oats, or tofu (Grasso et al., 2021). It is clear that in today’s globalized world, more so in Europe and throughout its history, new types of foods, food ingredients, or ways of producing food from all corners of the world have been introduced into the diets of the European population.

2.2. Types of Consumers

A vegan is a person who does not consume animal products, which includes meat, fish, dairy products, eggs, and honey (Appleby et al., 1999). Vegetarianism is, according to the Portuguese Vegetarian Association (APV), a plant-based eating style that excludes meat and fish and may or may not include derivatives of animal origin such as dairy products, eggs, and honey, depending on the type of vegetarianism (Allès et al., 2017). During the literature review of the main variable in this study, in regard to attitudes towards consumption in a food context, other concepts emerged that should be “put on the table”: attitude as a fundamental element of consumer behavior, purchase intention as a consequence of attitude, and associations of the main variables that build attitudes towards plant-based foods. There are many definitions and interpretations of the concept “attitude”. The term has multiple purposes in Western culture. It is not uncommon to hear “The players in the national team have no attitude”, or “What is the government’s attitude towards unemployment?”, or even “It’s more than that, it’s a question of attitude”. Solomon (2010) describes attitude as a generalized and lasting evaluation of people (including oneself), objects, subjects, or situations. In psychology, attitude can be defined as the general feeling that an individual has in favor of or against some stimulus object (Fishbein, 1963). Thus, anything towards which one has an attitude is called the attitude object (Ao) (Solomon, 2020). The feeling, or attitude, can be characterized as positive or negative in relation to the object, for example, a product, person, or problem, among others (Newhouse, 2010). One of the most relevant theories in this area of psychology that can explain how attitudes facilitate social behavior is the functional theory of attitudes (Katz, 1960), according to which attitudes exist because they serve some function for the person and can vary from person to person (Katz, 1960; Schlosser, 1998). In addition to addressing the functions of attitude, its composition has also been the subject of research. Most researchers agree that an attitude has three components: affect, behavior, and cognition (Ngugi et al., 2020). Having analyzed the functions and components of attitude, it is not too difficult to agree that consumers form attitudes in different ways. From the above, it can be seen that a starting point is the function of the attitude: utilitarian, ego-defensive, expression of values, and knowledge. In addition, attitudes can also originate from a fixed sequence: first, beliefs (cognitions) are formed about an attitude object, then the object is evaluated (affect), and consequently, some action is taken (behavior). However, the sequence is not always this orderly, as it depends on the consumer’s level of involvement and the circumstances, and so attitudes can also be formed by hierarchies of effects: high or low involvement and experiential. The review of this topic brings to the surface the notorious and profound relationship between attitude and behavior, also addressed by Fishbein (1963) and Solomon (2020). Briefly, and in the context of food consumption, this relationship is notorious when the consumer forms attitudes towards a plant-based food, which in turn shape their behavior in such a way that it manifests itself or not in the intention and/or actual purchase.

2.3. Variables of Attitude Towards the Consumption of Plant-Based Foods

To study attitude, three different variables were selected, which can facilitate the attitude towards the consumption in question. These are health awareness, animal welfare, and environmental protection, which are described in more detail below:

- -

- Variable Health Consciousness: Health consciousness is simply an individual’s concern for their own health (Teng & Lu, 2016). Health consciousness induces consumers to adhere to behaviors that improve or maintain their health (Wardle & Steptoe, 2003). According to some studies, it is possible to prove that a diet exclusively based on plant-based foods prevents many types of diseases (Lea & Worsley, 2001), and that consumers of plant-based foods usually have low cholesterol and blood pressure levels, which reduces the risk of cardiovascular diseases (Craig, 2009). In addition to the health evidence cited, other studies support that a diet made up of plant-based foods is healthier than a diet made up of foods of animal origin, with processed meats often containing toxins, carcinogens, antibiotics, and growth hormones (Springmann et al., 2016).

- -

- Variable Animal Welfare: According to data from the United Nations, it is estimated that by 2100, the world’s population will exceed 11 billion, which will lead to a significant increase in the demand for proteins. Consumers in general have a respect for animals and are concerned about their feelings and living conditions (Greenebaum, 2018). Concern for animal welfare and disapproval of the act of killing them for protein is the main reason for avoiding eating meat in the Western world (Lea & Worsley, 2001).

- -

- Environmental Concern: Environmental concern is related to awareness of environmental issues and effort and willingness to contribute to solving them (Cruz, 2017; Franzen & Vogl, 2013). Environmental concern refers to “the degree to which people are aware of environmental problems and support efforts to solve them and/or indicate a willingness to personally contribute to their resolution” (Dunlap & Jones, 2012). It has been proven that up to 73% of a person’s carbon footprint can be reduced by cutting meat and dairy products from the diet, which produces environmental benefits (McCabe et al., 2017; Willett et al., 2019). Consumers who care about the environment are more likely to opt for an environmentally friendly lifestyle (Konuk et al., 2015).

2.4. Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA)

One of the most widely used theories in consumer attitude evaluation studies is the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA), created by Martin Fishbein and Icek Ajzen in 1967 (Petrovici et al., 2008). This theory is based on the Fishbein Model, which links beliefs about an object and the attitude towards that same object (Fishbein, 1963). TRA posits that behavior is predicted by behavioural intention, which in turn is influenced by attitude toward the behavior and subjective norms. This framework is especially suitable for food-related behaviors, as it captures both personal evaluations and perceived social influences. Solomon (2020) addresses this model by identifying it as the most influential of the multi-attribute models of attitude. This type of model assumes that the consumer’s attitude towards an attitude object (Ao) depends on the beliefs the consumer has about the various attributes of the attitude object, holding that it is possible to identify and combine these specific beliefs to obtain a measure of the consumer’s general attitude (Fishbein, 1963). The basic model that relates consumer behavioral intention, which is closely related to behavior, is influenced by a consumer’s attitude and subjective norm. These two factors are independent of each other, and if they are both positive, behavioral intention, or more objectively purchase intention, increases (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980).

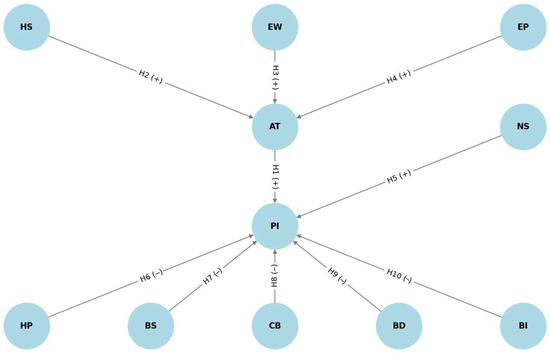

For Myresten et al. (2015), in the case of the intention to buy organic food, the group of people who can influence an individual can be divided into three categories: friends, family, and work/school colleagues. These three categories make up the subjective norm. If people are in favor of a certain action (in this case, buying plant-based foods), and if this opinion is important to the consumer, then this positively influences behavioral intention. The studies of consumer attitudes in Sweden (Myresten et al., 2015) are two references in this expansion of TAR. According to both, the authors decided to include what are known as barriers to consumption. During the data research for this investigation, there were many indicators of the existence of barriers to the consumption of plant-based foods (Fehér et al., 2020; Giacalone et al., 2022). According to Gebhardt (2021), barriers such as high prices, lack of information, and lack of taste are the ones that most put consumers off ABVs. In Spain, another study also validated the high price, lack of information, and lack of supply and availability of ABVs as barriers to consumption (Proveg, 2022). Still others describe the cultural barrier imposed by deep-rooted local gastronomies, such as that already mentioned in relation to the Atlantic Diet in Galicia and Northern Portugal. Returning to the TRA, it can be seen that these barriers are not taken into account, even though the consumer’s final behavior is indeed influenced. Thus, once again, based on the proposal by researchers (Mousel & Tang, 2016), other variables, called barriers, which are not included in the two factors attitude and subjective norm, are included between intention and behavior. The conceptual model presented is based on the TRA and establishes attitude (AT) and subjective norm (NS), made up of the influence of friends (NSA), the influence of family (NSF), and the influence of work/school colleagues (NSC), as the two antecedent variables of purchase intention (PI), the latter being the manifestation of the behavioral intention that results in the purchase of plant-based foods. To extend the explanatory power of TRA, we integrate antecedents of attitude—health consciousness, animal welfare, and environmental concern—which shape favorable attitudes towards plant-based consumption. These are supported by the literature linking these values with pro-environmental and ethical consumption behaviors. Furthermore, to account for external inhibitors, five barriers are included: high price, lack of taste, cultural aspects, low availability, and lack of information. These barriers are expected to moderate the relationship between intention and actual behavior. Finally, it was decided to include the purchase recommendation (CR) between the intention to buy and the actual purchase. The reason for this inclusion is that recommendation also plays an influential role in the decision-making process, specifically at the information-seeking stage.

The variables are treated as latent constructs, operationalized through multiple items measured on five-point Likert scales. A detailed description of items per construct is included in the Methods section.

In the context of food consumption, it is at this stage that it is common to consider the advice of services, products, or companies (Ngugi et al., 2020), recommendations which in turn can have a positive or negative influence on the purchase of plant-based foods. According to the model, and based on the above theoretical framework, various hypotheses were established, as follows:

H1.

Attitude (AT) towards the consumption of plant-based foods has a positive influence on the purchase intention (PI) of plant-based foods.

This hypothesis is directly grounded in the TRA (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980), which proposes that individuals are more likely to intend to perform a behavior when they have a favorable attitude toward it. In food contexts, multiple studies confirm this relationship (Petrovici et al., 2008; Beverland, 2014).

H2.

Health consciousness (HC) has a positive influence on attitude (AT) towards the consumption of plant-based foods.

Health consciousness is known to motivate individuals to adopt behaviors perceived as beneficial for their well-being. Studies show a positive association between health awareness and favorable attitudes towards plant-based diets (Teng & Lu, 2016; Lea & Worsley, 2001; Tuso et al., 2013).

H3.

Animal welfare (AW) has a positive influence on attitude (AT) towards the consumption of plant-based foods.

Concern for animal welfare is a strong driver of ethical food choices. The literature indicates that compassion towards animals and opposition to animal suffering correlate with positive attitudes toward plant-based foods (Greenebaum, 2018; Key et al., 2006; Hopwood et al., 2020; Rosenfeld & Burrow, 2017).

H4.

Environmental concern (EC) has a positive influence on attitude (AT) towards the consumption of plant-based foods.

Environmental motives are increasingly relevant in consumer behavior. Studies confirm that individuals with high environmental concern tend to develop positive attitudes towards sustainable dietary practices, including plant-based consumption (Cruz, 2017; Franzen & Vogl, 2013; Dunlap & Jones, 2012).

H5.

Subjective norm (SN) has a positive influence on the purchase intention (PI) of plant-based foods.

According to TRA, subjective norms—such as perceived social pressure—significantly affect behavioural intentions. Prior research demonstrates that family, friends, and peers influence individuals’ intentions to engage in sustainable food behaviors (Myresten et al., 2015; Mousel & Tang, 2016).

H6.

High prices have a negative influence on the purchase intention (PI) of plant-based foods.

H7.

Lack of taste has a negative influence on the purchase intention (PI) of plant-based foods.

H8.

Cultural aspects have a negative influence on the purchase intention (PI) of plant-based foods.

H9.

Poor availability has a negative influence on the purchase intention (PI) of plant-based foods.

H10.

Lack of information has a negative influence on the purchase intention (PI) of plant-based foods.

Hypotheses 6–10 are based on extensions to the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) proposed in recent literature, which argue that contextual barriers moderate or interfere with the translation of attitudes and norms into intentions or behaviour (Fehér et al., 2020; Giacalone et al., 2022). Price sensitivity, taste expectations, and lack of information have consistently been identified as inhibitors of plant-based food adoption (Gebhardt, 2021; Röös et al., 2022). Cultural factors are also significant, especially in regions with strong culinary traditions (Röös et al., 2022), while limited availability constrains access, influencing purchasing decisions (Wansink et al., 2005). Attitude (AT) towards the consumption of plant-based foods has a positive influence on the purchase intention (PI) of plant-based foods.

Figure 1 illustrates a conceptual model scheme of the relationship between hypotheses.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model: Factors influencing purchase intention of plant-based foods.

3. Methods

The aim of this study is to identify the greatest facilitators and barriers to the consumption of plant-based foods for residents of the Galicia–North Euroregion of Portugal. With this objective in mind, and in order to obtain a large amount of data, a quantitative study was carried out using a deductive approach, which should be adopted when a theory or hypothesis is to be tested. The choice of the quantitative method is also due to its focus on objectivity, since the data collected and the results can be extrapolated to the population under study, using statistical methods and treatment (Fonseca, 2002). To collect the data, a questionnaire survey was conducted of the sample population. This was inspired by the work of Myresten et al. (2015) and Mousel and Tang (2016), who used the expanded TAR model to investigate the behavior of the Swedish population towards organic food and substitute foods.

3.1. The Instrument

The data was collected through a structured online questionnaire composed of 15 mandatory questions. The questionnaire included multiple-choice questions and Likert-scale items, covering three main areas: sociodemographic and economic information (e.g., age, gender, education, income, household composition), dietary habits and consumption patterns (e.g., type of diet, weekly food expenditure, frequency of plant-based and animal-based food consumption), and attitudinal measures regarding plant-based food (e.g., personal beliefs, social influences, purchase intentions). Likert-scale questions were used to assess the level of agreement with statements related to health, environmental concerns, animal welfare, social norms, and perceived barriers to consuming plant-based foods. Detailed information about the questionnaire can be found in Ribeiro (2023). The constructs were operationalized using multi-item Likert scales adapted from validated instruments in the previous literature. Table 1 provides a summary of the items and sources used for each variable.

Table 1.

Measurement items by construct.

3.2. The Methods

Descriptive statistical analyses were conducted to summarize the main characteristics of the sample and to provide an overview of the distribution of responses. Frequencies and percentages were calculated for categorical variables, while central tendency (mean, median) and dispersion measures (standard deviation) were used for quantitative items derived from Likert scales. In addition, graphical representations such as bar charts and histograms were employed to visually interpret the data patterns and identify trends in dietary habits and attitudes toward plant-based food consumption.

To assess the internal consistency of the Likert-scale items used in the questionnaire, a reliability analysis was performed using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. This method allowed for the evaluation of the coherence among items within each conceptual construct (e.g., health motivations, environmental beliefs, social influence, purchase intention). A Cronbach’s alpha value equal to or greater than 0.70 was considered acceptable, indicating that the items reliably measured the intended latent constructs.

To examine the relationship between participants’ attitudes, social influences, perceived barriers, and their intention to purchase plant-based foods, linear regression analysis was conducted. Independent variables included the composite scores derived from Likert-scale items reflecting health, environmental, ethical, and social motivations, as well as perceived obstacles such as price and availability. The dependent variable was the stated intention to purchase plant-based food. The regression model enabled the identification of significant predictors and the extent to which these variables explained the variance in purchasing intentions. Prior to conducting regression analysis, the assumptions of normality, linearity, and homoscedasticity were tested. A normality test, with Kolmogorov–Smirnov for regression analysis, was performed to assess the normality of the residuals, giving a p-value less than 0.05. The linearity and homoscedasticity of residuals were evaluated through residual plots and found to meet the required assumptions. Multicollinearity was assessed through the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF), with all values below 5, confirming the absence of multicollinearity. Moreover, the adequacy of the data for factor analysis was verified through the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) test and Bartlett’s test of sphericity. The overall KMO was 0.812, and Bartlett’s test was significant (p < 0.001), supporting the use of principal component analysis and the internal validity of the constructs. These tests confirm the statistical adequacy of the data and support the reliability of the subsequent regression analysis.

3.3. Procedures

Residents in the Galicia–North Euroregion of Portugal number 6.4 million. Since the population is so large, there is a need to draw a sample by selecting elements from the same population, in a technique called non-probability convenience sampling (Saunders et al., 2009). Data collection took place between 28 October and 29 November 2022. Initially, a pre-test was carried out with 20 respondents, 10 from each language. The aim of the pre-test was to check that all the questions were understood and to obtain suggestions for improvement. In the questionnaire survey, a sample of 222 respondents was obtained, of which of which 117 were in Portuguese and 105 in Spanish. Taking into account that there were 8 invalid responses (7 in Portugal and 1 in Spain), because the respondents were not resident in the region under study, 214 surveys were validated, which constitutes the actual sample of the study in force. There were no omissions in all the validated questionnaires, as the online questions were mandatory. It was also ensured, through Jotform’s IP tracking feature, that it was not possible to fill in the questionnaire again using the same device (smartphone, computer, etc.). Filling in the questionnaire took an average of 3 to 5 min. The data was imported from the aforementioned Excel sheet and processed statistically using IBM SPSS v.28 software. The sample size of 214 respondents was considered adequate for the statistical procedures employed. According to Hair et al. (2012), for regression analysis with 10 independent variables, a minimum of 10–15 observations per variable is recommended. This corresponds to a required sample size between 100 and 150 participants. Our sample exceeds this threshold, providing sufficient statistical power for the analyses conducted. Although a non-probability convenience sampling method was used due to feasibility constraints, care was taken to ensure linguistic and regional diversity across the Euroregion. The sample is thus appropriate for exploratory purposes and for identifying preliminary patterns in attitudes and intentions related to plant-based food consumption.

3.4. Characterization of the Sample

The sample of 214 respondents is characterized, in general, and also divided by language type. This division is not made by nationality, but by language (PT: Portuguese and ES: Castilian) of the survey answered, since responses were obtained from cross-border residents, those who live in Portugal but are Spanish and vice versa. The characterization is based on the following socioeconomic factors: area of residence, gender, age, professional situation, educational qualifications, monthly income, and household. The distribution of respondents between Galicia (52.8%) and the north of Portugal (47.2%) is nearly equal.

According to Table 2, the gender distribution highlights a predominance of female respondents across both language groups. In terms of age, the study sample is predominantly middle-aged (41–60 years), with a minor presence of younger respondents, particularly among Spanish speakers. The slight overrepresentation of younger Portuguese respondents in the 21–25 age range suggests a potential difference in generational engagement with the study topic. These demographic insights are essential for understanding the potential influences of age and gender on the study’s findings.

Table 2.

Sociodemographic profile: Gender and age.

Table 3 shows that the employment distribution is relatively balanced between the two language groups, with slight variations in unemployment, student-worker status, and domestic work. Regarding education, Portuguese respondents tend to have higher levels of education, particularly at the master’s and doctoral levels, whereas Spanish respondents have a larger representation in secondary education and lower educational categories. These differences in educational attainment may have implications for socioeconomic trends and professional engagement within the sample population.

Table 3.

Sociodemographic profile: Employment status and educational qualifications.

Table 4 suggests that the income distribution suggests that a significant portion of respondents belong to higher-income brackets, with slight variations between Portuguese and Spanish respondents. Portuguese respondents show a greater presence in the lower-income brackets, while Spanish respondents report slightly higher earnings in the mid-to-upper range. In terms of household composition, both groups predominantly consist of couples with children, though Portuguese respondents demonstrate a greater tendency to reside with parents. The overall distribution highlights minor regional differences in living arrangements and economic conditions, which may influence broader lifestyle and consumption patterns within these groups.

Table 4.

Sociodemographic profile: Monthly income and household composition.

4. Analysis and Discussion of the Results

4.1. Food Consumption Habits

This section analyzes the data on the food consumption habits of the 214 individuals in the sample. The questions asked, corresponding to questions Q2 to Q5 of the questionnaire survey, allowed for a single selection from several options and focused on the type of diet, spending on food, and frequency of purchase of both animal and plant-based foods.

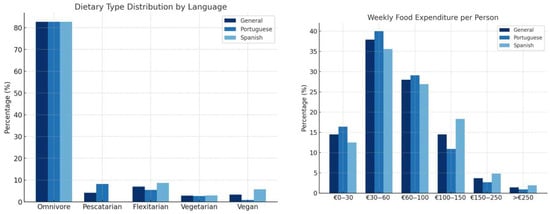

According to Figure 2, the analysis of dietary habits among respondents indicates that the majority follow an omnivorous diet (82.7%), with minimal variation between Portuguese- (82.7%) and Spanish (82.7%)-language respondents. Flexitarianism accounts for 7.0% of the sample, with a slightly higher prevalence among Spanish respondents (8.7%) compared to Portuguese respondents (5.5%). Vegetarianism and veganism represent a small proportion of the population, with 2.8% identifying as vegetarians and 3.3% as vegans. Notably, veganism is more prevalent among Spanish respondents (5.8%) compared to Portuguese respondents (0.9%). Conversely, pescatarianism is exclusive to Portuguese respondents (8.2%), with no Spanish respondents adhering to this dietary choice. These results suggest a shared preference for omnivorous diets across both groups while highlighting minor regional differences in alternative dietary choices.

Figure 2.

Dietary type and weekly food expenditure per person.

The data on weekly food expenditure per person reveal that the majority of respondents (37.9%) spend between EUR 30 and EUR 60 on food. Portuguese respondents report slightly higher expenditures in this range (40.0%) than their Spanish counterparts (35.6%). The second most common expenditure range is EUR 60 to EUR 100, reported by 28.0% of respondents, with similar proportions between Portuguese (29.1%) and Spanish (26.9%) groups. A smaller proportion (14.5%) spends between EUR 100 and EUR 150 per week, with Spanish respondents (18.3%) more likely to report this expenditure compared to Portuguese respondents (10.9%). Higher expenditures exceeding EUR 150 per week are relatively uncommon, representing only 5.1% of the sample. Conversely, 14.5% of respondents report spending less than EUR 30 weekly, with Portuguese respondents (16.4%) being more likely to fall into this category than Spanish respondents (12.5%). These findings indicate a general alignment in food expenditure patterns between the two groups, with a slight tendency for Portuguese respondents to report both higher and lower expenditure extremes.

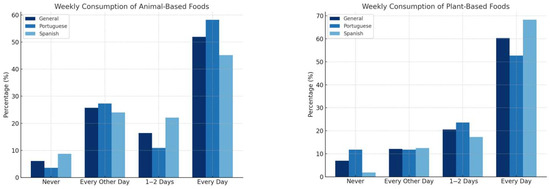

Regarding the consumption habits, Figure 3 shows that the majority of respondents (51.9%) consume animal-based foods daily, with a higher proportion among Portuguese respondents (58.2%) compared to Spanish respondents (45.2%). A quarter of the respondents (25.7%) consume these foods every other day, while 16.4% report consuming them one to two times per week. Only 6.1% of respondents abstain entirely from animal-based foods, with a higher percentage among Spanish respondents (8.7%) than Portuguese respondents (3.6%). Plant-based food consumption is highest among Spanish respondents, with 68.3% consuming these foods daily compared to 52.7% of Portuguese respondents. Around 20.6% of the total sample report consuming plant-based foods one to two times per week, while 12.1% consume them every other day. A small proportion (7.0%) never consume plant-based foods, with this percentage being higher among Portuguese respondents (11.8%) than Spanish respondents (1.9%).

Figure 3.

Weekly consumption of animal-based and plant-based food.

4.2. Intention, Recommendation, and Barriers

With a clearer idea of the socioeconomic and food consumption profile of the respondents, the analysis begins with the opinion they expressed regarding their attitude towards the consumption of plant-based foods, the subjective norm, as well as the variables associated with the purchase of plant-based foods and which are projected in the conceptual model: intention, recommendation, and barriers.

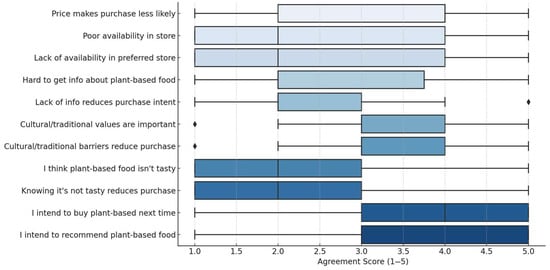

The results of these sentences about intention, recommendation, and barriers are in Figure 4. The boxplots illustrate the distribution of responses to statements assessing participants’ intentions and perceived barriers regarding the purchase of plant-based foods.

Figure 4.

Barriers, intention, and recommendation.

Overall, purchase and recommendation intentions exhibited high median values and narrow interquartile ranges, suggesting a generally favorable disposition and a strong consensus among respondents toward engaging in future plant-based food consumption behaviors. In contrast, items related to perceived barriers—such as negative taste perceptions and cultural or traditional resistance—displayed a greater dispersion and lower central tendency, indicating more variability in belief patterns across the sample. These findings suggest that while the overall intent to adopt and promote plant-based diets is strong, specific perceptual barriers remain salient for a subset of the population. Tailored interventions addressing these concerns may be beneficial in further promoting behavioral change.

The internal consistency of the items related to perceived barriers and purchase intention was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha. The resulting value was α = 0.71, indicating an acceptable level of reliability. This suggests that the items within this section are sufficiently correlated to be considered part of a coherent scale, though they likely reflect multiple sub-dimensions.

4.3. Regression Analysis for the Hypothesis

Ten hypotheses were tested to evaluate the psychological and structural determinants of purchase intention toward plant-based foods. Linear regression models were used to test the relationships between constructs, and Table 5 summarizes the regression results for each hypothesis, including coefficients and significance levels.

Table 5.

Regression analysis.

The regression analysis supported hypotheses H1 through H5: health consciousness, animal welfare concern, and environmental concern emerged as significant predictors of attitude, while attitude and subjective norm significantly influenced purchase intention. The model accounted for approximately 30% of the variance in intention. Among the perceived barriers, lack of taste (H7) and lack of information (H10) exerted statistically significant negative effects on intention. A high price (H6) and low availability (H9) did not have a meaningful impact. Cultural aspects (H8), contrary to the initial hypothesis, displayed a positive relationship with purchase intention. This unexpected result may stem from a reinterpretation of local gastronomic traditions as being compatible with plant-based consumption. These results are consistent with the previous literature but also introduce relevant theoretical and empirical contributions. The incorporation of ethical and environmental drivers into the Theory of Reasoned Action enhances its explanatory value in the context of sustainable food consumption. Additionally, the unexpected positive influence of cultural aspects suggests that local food identity may, in some cases, support rather than hinder dietary innovation. Overall, the findings indicate that psychological constructs such as attitude, health consciousness, and ethical concerns (environmental and animal welfare) play a pivotal role—either directly or indirectly—in shaping the intention to consume plant-based foods. Conversely, perceived barriers related to taste and information significantly hinder this intention, reinforcing their relevance within predictive behavioural models. The lack of significant effects from price and availability suggests that, at least in this sample, structural constraints are less influential than personal values. The positive coefficient for cultural aspects also highlights the importance of considering contextual and interpretative dimensions when analyzing consumer behavior in culturally rich regions.

4.4. Sociodemographic Effects on Intention and Perceived Barriers

The statistical analysis conducted to explore the relationship between sociodemographic variables and the main constructs of the model encompassed correlation, regression, moderation, and subgroup comparison techniques. Pearson correlation analysis indicated a negative, though not statistically significant, association between income level and perceived price barrier (r = −0.37, p = 0.29), suggesting that participants with higher incomes tended to perceive price as less of a barrier to purchasing plant-based foods. However, this trend was not robust, as confirmed by linear regression (β = −0.0015, p = 0.292), indicating that income alone does not substantially account for variations in price sensitivity within the sample.

Further, moderation analysis was performed to examine whether educational attainment influenced the relationship between animal welfare concern and overall attitude toward plant-based foods. The results revealed no significant moderating effect (interaction β = 0.077, p = 0.644), implying that the impact of ethical concern on attitude is consistent regardless of educational background.

Subgroup analyses using one-way ANOVA demonstrated no significant differences in perceived price barriers across income brackets (F(4, 209) = 1.65, p = 0.231) or in composite attitude scores across age groups (F(5, 208) = 0.86, p = 0.489). Additionally, an independent-samples t-test confirmed the absence of significant gender differences in purchase intention (t(212) = 1.27, p = 0.207).

Collectively, these findings indicate that, within this sample, sociodemographic variables such as income, age, gender, and education exert only a marginal influence on perceived barriers, attitudes, and purchase intentions related to plant-based foods. Instead, the results reinforce the centrality of value-based antecedents—namely health consciousness, environmental concern, and animal welfare—in shaping consumer intentions. This pattern suggests that intrinsic motivations and ethical considerations are more decisive than demographic characteristics in explaining the propensity to adopt plant-based diets in the Galicia–Northern Portugal Euroregion. These insights highlight the importance of focusing on motivational and attitudinal drivers when designing interventions and communication strategies aimed at promoting sustainable dietary transitions, as demographic segmentation alone may not capture the most salient determinants of consumer behavior in this context.

4.5. Discussion

The results obtained reinforce the theoretical assumptions proposed and offer new insights into the specificities of the Galicia–Northern Portugal Euroregion. The fact that attitude is a strong and direct predictor of purchase intention is fully aligned with the central tenets of the Theory of Reasoned Action (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980). This confirms that, in the context of food consumption, when consumers perceive plant-based diets as compatible with their values and beliefs, their intention to adopt these diets strengthens accordingly.

The three antecedents of attitude—health consciousness, animal welfare, and environmental concern—demonstrated significant positive effects, underscoring their importance as motivational drivers. Health consciousness, in particular, reflects a growing trend, especially in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic. As highlighted by national and regional studies, the pandemic appears to have heightened public awareness of the connection between diet and well-being, fostering a more deliberate approach to food choices. This shift is evident in our data, where individuals with greater health concerns are notably more receptive to plant-based alternatives.

The influence of animal welfare and environmental concern demonstrates the relevance of ethical and ecological values in shaping attitudes, which is consistent with what was described previously (Cruz, 2017; Dunlap & Jones, 2012). In these cases, the consumer is not only motivated by personal benefit but also by a sense of moral responsibility and collective impact. This moral engagement is particularly significant in the context of food, as decisions made at the individual level are perceived to have tangible consequences for animal lives and the environment.

The role of subjective norms, although not the strongest predictor, also contributed positively to purchase intentions. This confirms that social influence—whether from friends, family, or colleagues—can help consolidate behavioural intentions, particularly when those around the consumer validate or encourage sustainable food choices (Myresten et al., 2015; Mousel & Tang, 2016). However, the relatively modest impact of subjective norms suggests that, in this region, personal conviction may weigh more heavily than social conformity. This could reflect the cultural characteristics of the Euroregion, where individual decision-making is shaped by deeply internalized values.

A particularly noteworthy contribution of this study is the unexpected positive effect of cultural aspects on purchase intention. This finding contradicts the initial assumption that local food culture would act as a barrier to adopting plant-based diets. On the contrary, the results suggest that traditional gastronomy—far from being a static and conservative structure—can evolve and integrate new dietary practices. Thus, what was initially considered a constraint may, in fact, be a valuable lever for transformation, especially if the cultural narrative is framed in a way that embraces both heritage and innovation.

These findings are consistent with recent empirical contributions that underscore the pivotal role of internal motivations—such as health awareness, ethical concerns, and environmental values—in shaping sustainable food behaviors. As noted by Viroli et al. (2023), although plant-based diets are increasingly associated with significant health and ecological benefits, their widespread adoption remains constrained by factors such as cultural acceptability and perceived affordability. These observations suggest that the mere availability of plant-based options does not suffice to ensure behavioural change unless such motivations are deeply embedded in consumers’ value systems.

In terms of barriers, Rickerby and Green (2024), in a comprehensive systematic review focused on high-income countries, identify several recurring obstacles that inhibit the transition to plant-based eating. These include limited product availability, insufficient culinary variety, economic considerations, concerns about nutritional adequacy, and low levels of social endorsement. Their work highlights that even in socioeconomically privileged contexts, structural and perceptual constraints continue to undermine intentions to adopt more sustainable dietary patterns.

Furthermore, the social dimension of food choice should not be underestimated. Malila et al. (2025) provide compelling evidence that individuals who engage in plant-based eating are frequently subject to social stigma. Although often perceived as morally conscious and competent, they may simultaneously evoke feelings of resentment or discomfort among meat-eaters. This ambivalence contributes to a social environment in which plant-based choices are not always perceived as socially normative or desirable, thus hindering broader acceptance.

In our study, lack of taste and lack of information were also confirmed as significant barriers, inhibiting the intention to consume plant-based foods. These perceptions have also been highlighted in previous studies (Fehér et al., 2020; Gebhardt, 2021) and appear to persist despite growing market availability. In this sense, it is clear that availability alone is not sufficient—consumers need to be confident that plant-based products are appealing and know how to integrate them into their routines. This reinforces the need for education and communication strategies focused on culinary knowledge, flavor variety, and ease of preparation.

Conversely, price and availability, although often cited as key obstacles in the literature, did not show statistically significant effects in this study. This may indicate that, in this specific sample, these factors are no longer perceived as decisive—possibly because the market has already adapted to consumer expectations in these aspects or because intrinsic motivations (health, ethics, environment) are now more influential than logistical or financial considerations.

The additional statistical analyses conducted on sociodemographic variables reinforce this interpretation. Despite exploring correlations, regressions, moderations, and subgroup comparisons, no statistically significant relationships were found between income, gender, age, or educational level and the key constructs of the model, including purchase intention and perceived barriers. This suggests that plant-based food consumption in the Galicia–Northern Portugal Euroregion is not predominantly shaped by demographic attributes, but rather by internalized motivational factors such as health consciousness, environmental concern, and ethical commitment to animal welfare. These findings align with recent behavioural research advocating a shift from demographic segmentation to psychographic and value-based approaches in designing interventions to promote sustainable consumption (Dorce et al., 2021; Fehér et al., 2020). In this context, targeting shared ethical motivations may be more effective than stratifying audiences by age or income.

Taken together, these insights reinforce the relevance of expanding the Theory of Reasoned Action by integrating contextual, social, and ethical variables. Constructs such as perceived affordability, cultural compatibility, and moral salience appear increasingly necessary to explain consumers’ intentions and behaviors in complex food environments. As suggested by Dorce et al. (2021), contemporary models of consumer behavior must account for these multidimensional influences if they are to capture the full complexity of sustainable food decision-making. In the specific case of the Galicia–Northern Portugal Euroregion, this expansion proves especially pertinent given the strong interplay between tradition, identity, and innovation.

The finding that cultural factors exert a positive influence on the intention to consume plant-based foods directly challenges the prevailing assumption that culinary heritage functions solely as a barrier to dietary innovation. Rather than treating this result as an anomaly, it should be understood as indicative of a broader paradigm in which food heritage serves as a catalyst for sustainability (Kapelari et al., 2020). When consumers perceive plant-based options as a coherent extension of the Atlantic Diet, a dietary tradition rich in vegetables and legumes, they experience cultural compatibility that reinforces continuity rather than disruption (Lorenzo et al., 2022). Moreover, the concept of rooted innovation, as articulated by Graham (2014), illuminates how heritage recipes (for example, legume-based stews) can be reinterpreted with plant-based ingredients, allowing culinary evolution without eroding the underlying cultural narratives. Finally, frameworks of symbolic mobilization elucidate how plant-based consumption can become a performative act of communal care, transforming food choices into expressions of regional identity and collective responsibility, as observed by Di Pietro et al. (2018). Taken together, these mechanisms underscore the potential of cultural identity to function as a lever, rather than a constraint, in the promotion of sustainable dietary change.

5. Conclusions and Implications

This study set out to understand the main drivers and barriers influencing consumer attitudes and intentions towards plant-based food consumption in the Galicia–Northern Portugal Euroregion, a territory marked by cultural proximity, shared gastronomic traditions, and increasing awareness of health and environmental concerns. Framed within the post-pandemic context, the research responds to a timely and socially relevant question: To what extent are consumers in this region open to changing their eating habits in favor of more sustainable options, and what factors facilitate or hinder that process?

The data collected and analyzed allow us to conclude that the objective of this study was successfully met. Personal values—particularly those linked to health awareness, concern for animal welfare, and environmental responsibility—were confirmed as the strongest and most consistent predictors of favorable attitudes towards plant-based food consumption. These attitudes, in turn, have a robust effect on purchase intention, reinforcing the assumption that behavioural change is largely grounded in internal convictions and beliefs. Although the subjective norm also contributes to intention, its impact is less pronounced, suggesting that, in this context, the decision to adopt a more plant-based diet tends to be more individual and value-driven than socially imposed.

The analysis of perceived barriers revealed interesting nuances. While lack of taste and lack of information emerged as significant inhibitors—confirming that sensory expectations and uncertainty about product use are still critical obstacles—other commonly cited barriers, such as high price and limited availability, did not have significant effects. This may point to a shift in how consumers perceive these issues, possibly due to a wider and more accessible range of plant-based products now available on the market. Notably, cultural aspects showed an unexpected positive relationship with intention. Rather than acting as a constraint, local culinary identity seems to coexist with—and even support—the openness to new, more sustainable food practices. This finding challenges the often-assumed dichotomy between tradition and innovation and suggests that, in regions like this one, food culture may play an enabling rather than limiting role in dietary change.

From a theoretical perspective, this study offers a meaningful contribution to the development of the Theory of Reasoned Action. By incorporating ethical and environmental dimensions as antecedents of attitude, and by integrating perceived barriers into the model, the research presents an expanded framework that more accurately reflects the complexity of consumer behavior in the domain of food sustainability. The results show that individual values are key to intention formation, but also that their influence can be either amplified or undermined by more pragmatic considerations, such as taste and knowledge. The model thus benefits from the inclusion of both motivational and contextual variables, enhancing its explanatory capacity and aligning it more closely with contemporary realities.

The practical implications of these findings are particularly relevant for brands, policymakers, and other stakeholders involved in promoting sustainable food transitions. For food companies and brands, the message is clear: health, environmental, and ethical benefits are compelling arguments that resonate with consumers and should be central to communication strategies. However, these benefits must be supported by tangible product quality, especially in terms of flavor, texture, and culinary versatility. Investing in research and development to improve the sensory profile of plant-based foods is not a luxury but a strategic necessity. Equally important is addressing the informational gap. Many consumers report not knowing how to cook plant-based meals, how to combine ingredients, or whether these products meet nutritional needs. Developing informative and engaging content—through packaging, digital media, in-store communication, or partnerships with chefs and nutritionists—can help demystify these products and reduce resistance to trials.

Policymakers can also draw important lessons from this study. In a context where plant-based diets are aligned with public health and sustainability goals, public institutions have both the responsibility and the opportunity to lead by example. Educational campaigns that focus on the benefits of plant-based eating, when adapted to different age groups and sociocultural profiles, can increase awareness and stimulate change. Institutional catering—in schools, hospitals, universities, or public administration—should include high-quality plant-based options, not only to make them available but also to make them visible, normalized, and appealing. Public support for innovation in the plant-based sector, whether through fiscal incentives or support for SMEs developing such products, can accelerate the transformation of the food system.

At a broader social level, the positive role of cultural identity in this study opens up new opportunities for integrating plant-based diets into regional narratives. In the Galicia–Northern Portugal Euroregion, traditional diets such as the Atlantic Diet already prioritize vegetables, pulses, cereals, and olive oil. Rather than opposing plant-based consumption, this culinary heritage offers a valuable entry point for reframing it as an expression of continuity, care, and belonging. Promoting this reinterpretation—through gastronomy festivals, regional branding, or educational materials—can foster pride in food traditions while adapting them to new ecological and health imperatives.

In short, this study demonstrates that the adoption of plant-based diets in the Euroregion is not only a realistic possibility but also a trend already underway, supported by deeply held personal values and a cultural context that, rather than resisting change, may be ready to embrace it. The intention to consume plant-based foods grows stronger when consumers perceive these choices as aligned with their convictions and their cultural identity, and it weakens when they feel unsure about flavor or product use. Stimulating this type of consumption will require a coordinated effort among brands, public institutions, and civil society, capable of reinforcing motivations while simultaneously eliminating perceived barriers.

Our findings also underscore the limited role of sociodemographic factors in predicting plant-based food consumption behaviors in this cross-border context. Although variables such as income, education, gender, and age were tested using multiple statistical techniques, none demonstrated significant associations with consumer attitudes or intentions. This reinforces the conclusion that internalized value systems, particularly those related to health, environmental responsibility, and animal welfare, constitute the primary drivers of behavior. Consequently, public policy, marketing, and educational strategies should not rely exclusively on demographic targeting. Instead, interventions should be framed around shared ethical and sustainability concerns, which appear to exert a more consistent and influential role in shaping dietary change across different population segments.

Investing in this transition is not only desirable from a sustainability standpoint but also strategic for responding to a growing segment of consumers who are looking for products that are not just nutritionally adequate, but ethically and environmentally coherent. As such, the findings of this study can support more informed decisions at the level of marketing, product development, public policy, and education, contributing to healthier, more sustainable, and culturally meaningful food systems.

In addition to these conclusions, the findings contribute to a broader theoretical reflection on the applicability and adaptability of behavioural models, particularly the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA), in culturally hybrid and cross-border contexts. While TRA assumes that intention is primarily shaped by attitudes and subjective norms, our results suggest that these constructs may operate differently depending on sociocultural configurations, even within a geographically cohesive area. The differentiated weight of subjective norms in Galicia and personal attitudes in Northern Portugal challenges the presumed universality of motivational hierarchies and invites a more nuanced interpretation of intention formation across regional boundaries. This highlights the importance of incorporating cultural, historical, and identity-related variables into behavioural models, especially in areas where food practices are deeply connected to local traditions and collective memory.

These insights suggest the need for theoretical refinements of the TRA model, recognizing that ethical, emotional, and symbolic factors such as environmental responsibility, concern for animal welfare, and cultural belonging may function as key antecedents of attitudes and norms. Rather than treating these dimensions as peripheral, the present study proposes that they should be considered central elements in the formation of sustainable consumption intentions. This perspective supports a more contextualized understanding of rational choice, one that reflects the complex layering of personal beliefs, social expectations, and cultural meanings.

From a practical standpoint, the study also offers insights that are valuable for organizations and policymakers beyond the Euroregion. It demonstrates that aligning plant-based food promotion with cultural values and established culinary traditions can be more effective than positioning these diets as a break from the past. Framing plant-based options as compatible with regional heritage increases the likelihood of public engagement and sustained behavioural change. This approach can serve as a reference for other territories with strong food identities, helping to avoid resistance while encouraging a sense of continuity and pride.

The findings also support the development of place-based public policies that take into account local attitudes, food imaginaries, and symbolic attachments. Educational and health institutions can play a decisive role by incorporating plant-based choices into public catering in ways that promote familiarity, visibility, and cultural coherence. In parallel, communication campaigns should present these diets not only as nutritionally beneficial but also as ethically responsible and culturally meaningful. In this framework, food becomes a means of ecological expression, allowing individuals to articulate values related to sustainability, identity, and belonging.

Ultimately, the contribution of this study lies not only in its empirical findings but also in the integrated perspective it offers on the interplay between values, identity, and consumption. In a time shaped by environmental urgency and social transition, understanding how individuals negotiate dietary change within culturally rich settings is essential. By showing that cultural identity can serve as a source of mobilization rather than a barrier, this research points to new ways of designing interventions that are both socially embedded and ethically robust.

Building on these insights, we propose a multidimensional behavioural framework in which value-based antecedents of attitude (health consciousness, environmental concern, and animal welfare) interact with subjective norms and contextual inhibitors to shape intentions. This model is augmented by integrating perceived behavioural control and differentiating between injunctive and descriptive norms from the Theory of Planned Behavior (Ajzen, 1991), thereby refining the role of social influence. Cultural identity is reconceptualized as an antecedent of attitude with mobilizing potential, rather than solely an inhibitor. Finally, “recommendation” is positioned as a mediating variable that operationalizes the intention–behavior gap through information-seeking processes (Ngugi et al., 2020). This enriched framework offers a blueprint for future theoretical refinements in sustainable consumption research, aligning with calls for hybrid behavioural theories and transdisciplinary approaches to food system sustainability.

5.1. Practical Implications

Our findings indicate that taste and information deficits constitute the principal barriers to plant-based food adoption and that health, environmental, and ethical motivations serve as primary drivers. Food companies should therefore prioritize consumer-centric sensory research, employing flavor profiling and texture mapping, to optimize product organoleptic qualities and utilize emerging fermentation technologies to enrich umami notes and eliminate undesirable off-flavors. In tandem, brands must develop educational communication strategies that directly address informational gaps: concise, visually engaging recipe tutorials and nutritional infographics should be deployed across digital platforms and packaging to enhance cooking self-efficacy and demystify plant-based meal preparation (Giacalone et al., 2022). Marketing narratives must foreground authentic testimonials that link plant-based consumption to tangible health improvements, such as reductions in cholesterol and blood pressure, and to ethical concerns regarding animal welfare, thereby reinforcing consumer motivations through emotionally resonant storytelling.

In terms of communication, brands should adopt explanatory messages that directly address the principal barriers identified, flavor and lack of information, through clear labeling and digital storytelling campaigns. Trials in online supermarkets indicate that brief explanations of sustainability and health benefits, accompanied by practical cooking instructions, increase consumers’ perceived self-efficacy without eliciting “green skepticism”. Such a strategy must articulate health-related claims (supported by clinical data on reductions in cholesterol and blood pressure) with user testimonials illustrating concrete well-being gains, thus crafting authentic and emotionally engaging narratives that reinforce both ethical and health motivations.

Public health authorities and policymakers have a strategic role in reframing plant-based eating not as a restrictive alternative, but as a positive extension of local food identity. Institutional campaigns should highlight overlaps between traditional food patterns (e.g., the Atlantic Diet) and plant-based principles. This can be achieved through public communication initiatives that adapt iconic regional dishes into plant-based formats or through partnerships with culinary schools and tourism boards. Fiscal incentives for SMEs developing regional plant-based products, pilot programs in public catering (schools, hospitals), and supportive procurement policies can normalize these options in everyday settings.

Educational institutions can operationalize these insights by integrating plant-based food education into curricula. Beyond dietary instruction, this includes cultural narratives about food, environmental literacy, and hands-on learning. Offering regionally inspired plant-based meals in schools and universities, accompanied by materials explaining their nutritional and cultural value, can promote early acceptance. Involving students in planning, tasting sessions, or gardening projects strengthens ownership and reduces resistance. At the university level, sustainability modules in marketing, health, and gastronomy can prepare professionals to integrate these concerns into future practices.

5.2. Limitations and Future Research

This study presents several limitations that should be acknowledged and that open up avenues for future research. Firstly, the conceptual model used, although theoretically robust, was based on an structure adapted from previous studies, which necessarily constrained the formulation of the questionnaire items. In particular, some constructs were operationalized through simplified or restrictive formats, notably in questions Q6 to Q8, where respondents were asked to express a general opinion followed by a weighting or prioritization. This repetition and structure may have introduced ambiguity or respondent fatigue, potentially influencing the reliability of the data collected.

Secondly, the use of a non-probabilistic convenience sampling technique, while practical and suited to exploratory objectives, limits the generalizability of the results. Although care was taken to ensure a linguistic and regional balance between respondents in Galicia and Northern Portugal, the sample cannot be considered statistically representative of the broader Euroregional population. Moreover, given the growing but still relatively niche status of plant-based diets, it is possible that the sample overrepresents individuals with a predisposition towards sustainable or health-conscious consumption.

Thirdly, while the quantitative approach adopted allows for the testing of relationships between variables and hypothesis validation through regression analysis, it does not capture the richness and complexity of subjective perceptions related to food culture, ethical values, or resistance to change. These dimensions are particularly relevant in contexts where traditional gastronomy plays a strong identity role, as is the case in the studied Euroregion.

Considering these limitations, future research should consider several directions to deepen and broaden the understanding of plant-based food consumption in culturally rich and evolving contexts. From a methodological standpoint, it is recommended that future studies revise and expand the conceptual model to allow for more flexible and contextually sensitive item development. Incorporating qualitative methods—such as focus groups or in-depth interviews—would enable researchers to explore how consumers interpret plant-based diets, how they reconcile them with local culinary traditions, and how they perceive social influences, media narratives, or prejudices related to vegetarianism and veganism.

It is also advisable to conduct studies using probabilistic sampling methods to enhance representativeness and obtain more reliable generalizations across different demographic segments of the population. Longitudinal studies could add further value by tracking attitudinal and behavioural changes over time, particularly in response to market developments, policy interventions, or cultural shifts.

Beyond the Galicia–Northern Portugal Euroregion, comparative research across other regions or countries would offer insights into how cultural, economic, and policy differences shape attitudes and intentions regarding plant-based food consumption. Such research is increasingly relevant in the context of global efforts to promote sustainable and healthy diets and can inform strategies adopted by both policymakers and the food industry.

Ultimately, future studies that integrate these methodological and conceptual refinements will contribute to a more comprehensive and nuanced understanding of consumer behavior in the context of sustainable food transitions. They will also support the development of more effective marketing strategies, public communication campaigns, and food policies aimed at accelerating the adoption of plant-based diets and advancing sustainability goals at regional and global levels.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.J.S.d.F., M.P.R. and B.B.S.; methodology, M.P.R. and H.S.R.; validation, M.J.S.d.F., H.S.R. and B.B.S.; formal analysis, M.J.S.d.F.; investigation, H.S.R. and M.P.R.; resources, M.J.S.d.F.; data curation, H.S.R.; writing—original draft preparation, M.J.S.d.F. and B.B.S.; writing—review and editing, M.J.S.d.F.; visualization, M.P.R.; supervision, B.B.S.; project administration, M.J.S.d.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the use of anonymized survey data collected with informed consent, with no personal or sensitive data being processed. The study was carried out in accordance with the ethical and legal principles governing the preparation of master’s dissertations in Marketing at the School of Business Sciences of the Polytechnic Institute of Viana do Castelo, as approved by the Scientific and Technical Council.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions but are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the participants in this study and the reviewers for their valuable contributions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1980). Understanding attitudes and predicting social behaviour. Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Allès, B., Baudry, J., Méjean, C., Touvier, M., Péneau, S., Hercberg, S., & Kesse Guyot, E. (2017). Comparison of sociodemographic and nutritional characteristics between self-reported vegetarians, vegans, and meat-eaters from the nutrinet-santé study. Nutrients, 9, 1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appleby, P. N., Thorogood, M., Mann, J. I., & Key, T. J. A. (1999). The oxford vegetarian study: An overview. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 70(3), 525s–531s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakhsh, A., Lee, S.-J., Lee, E.-Y., Hwang, Y.-H., & Joo, S.-T. (2021). Traditional plant-based meat alternatives, current, and future perspective: A review. Journal of Agriculture & Life Science, 55(1), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bausch, C. L., Milan, G. S., Graciola, A. P., Eberle, L., & Bebber, S. (2021). The COVID-19 pandemic and the changes in consumer habits and behavior. Revista Gestão e Desenvolvimento, 18(3), 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beverland, M. B. (2014). Sustainable eating: Mainstreaming plant-based diets in developed economies. Journal of Macromarketing, 34(3), 369–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, D., Sousa, B., Liberato, D., Liberato, P., Lopes, E., Gonçalves, F., & Figueira, V. (2023). Digital communication and the crisis management in hotel management: A perspective in the Euroregion North of Portugal and Galicia (ERNPG). Administrative Sciences, 13(8), 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casas, R., Raidó-Quintana, B., Ruiz-León, A. M., Castro-Barquero, S., Bertomeu, I., Gonzalez-Juste, J., Campolier, M., & Estruch, R. (2022). Changes in Spanish lifestyle and dietary habits during the COVID-19 lockdown. European Journal of Nutrition, 61, 2417–2434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, A. D. (2009). How do you feel—Now? The anterior insula and human awareness. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 10(1), 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, S. M. (2017). The relationships of political ideology and party affiliation with environmental concern: A meta-analysis. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 53, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Pietro, L., Guglielmetti Mugion, R., & Renzi, M. F. (2018). Heritage and identity: Technology, values and visitor experiences. Journal of Heritage Tourism, 13(2), 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorce, L. C., da Silva, M. C., Mauad, J. R. C., de Faria Domingues, C. H., & Borges, J. A. R. (2021). Extending the theory of planned behavior to understand consumer purchase behavior for organic vegetables in Brazil: The role of perceived health benefits, perceived sustainability benefits and perceived price. Food Quality and Preference, 91, 104191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlap, R. E., & Jones, R. E. (2012). Environmental concern: Conceptual and measurement issues. In R. E. Dunlap, & A. M. Michelson (Eds.), Handbook of environmental sociology (Vol. 3, pp. 482–524). Greenwood Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fardet, A. (2017). New concepts and paradigms for the protective effects of plant based food components in relation to food complexity. In Vegetarian and plant based diets in health and disease prevention (pp. 293–312). Academic Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehér, A., Gazdecki, M., Véha, M., Szakály, M., & Szakály, Z. (2020). A comprehensive review of the benefits of and the barriers to the switch to a plant-based diet. Sustainability, 12, 4136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]