The Impact of Digital Transformation Job Autonomy on Lawyers’ Support for Law Firms’ Digital Initiatives: The Mediating Role of Cognitive Adjustment and the Moderating Effect of Leaders’ Empathy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theory and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Job Demands–Resources Model

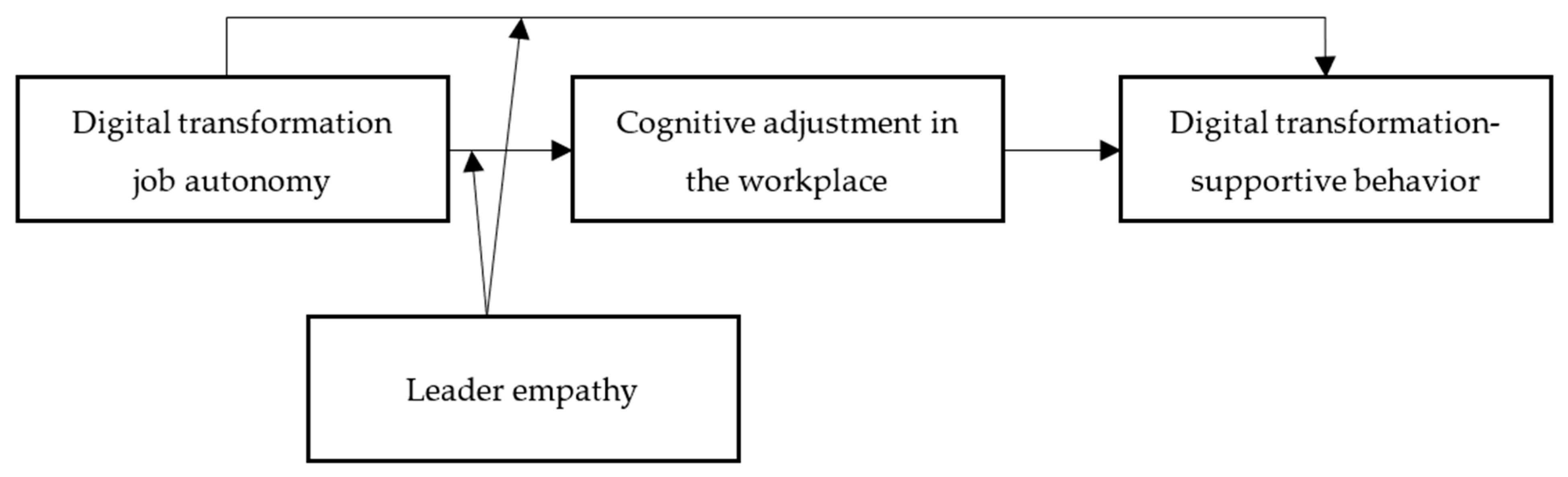

2.2. Digital Transformation Job Autonomy and Digital Transformation-Supportive Behavior

2.3. The Mediating Role of Cognitive Adjustment in the Workplace Linking Digital Transformation Job Autonomy and Supportive Behavior

2.4. The Moderating Role of Leader Empathy

3. Method

3.1. Samples and Procedures

3.2. Measurements

3.2.1. Digital Transformation Job Autonomy

3.2.2. Cognitive Adjustment in the Workplace

3.2.3. Leader Empathy

3.2.4. Digital Transformation-Supportive Behavior

3.2.5. Control Variables

4. Results

4.1. Preliminary Analyses

4.2. Hypotheses Test

4.2.1. Test of Main Effects

4.2.2. Test of Mediation Effects

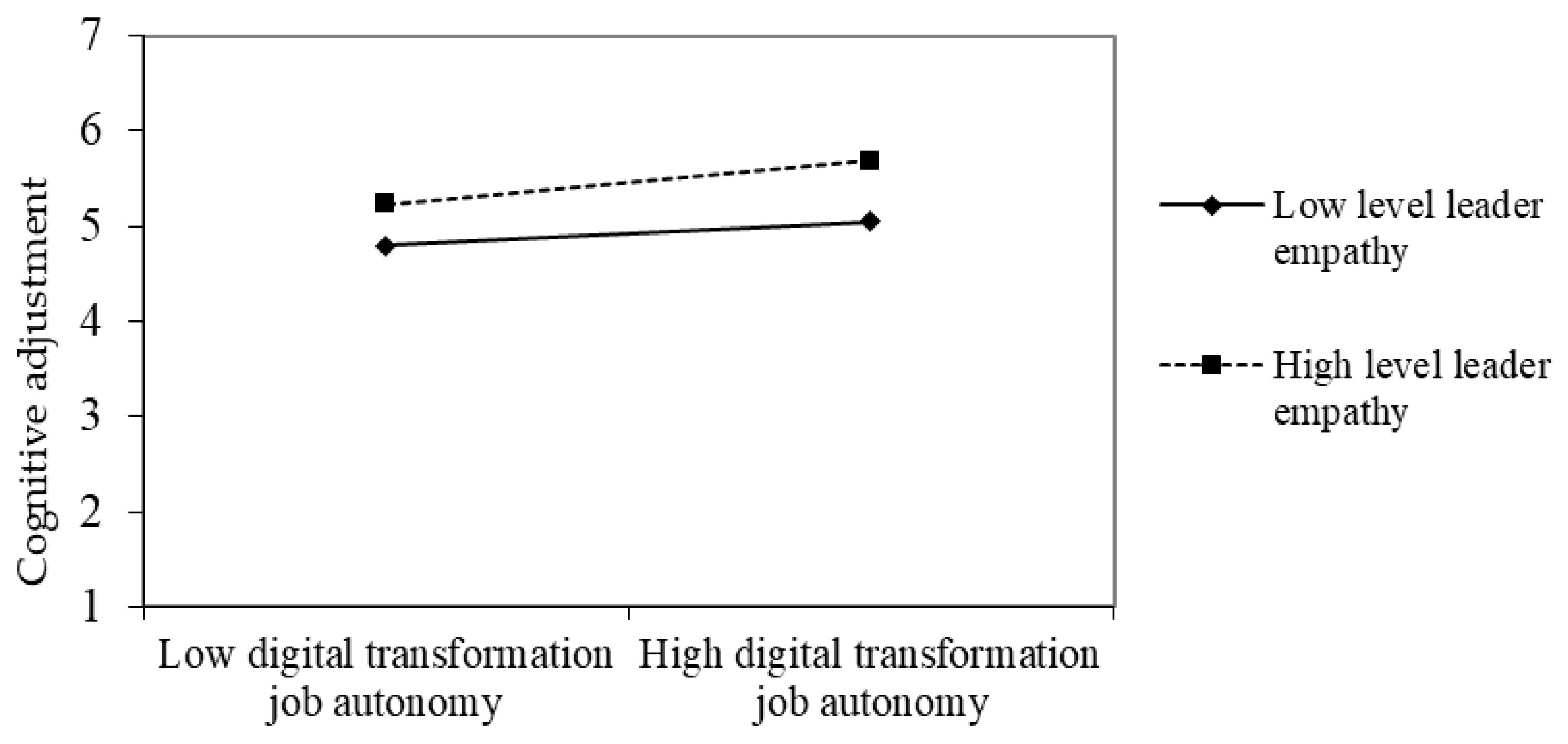

4.2.3. Test of Moderation Effects

4.2.4. Test of Moderated Mediation Effects

4.3. Fuzzy-Set Qualitative Comparative Analysis

4.3.1. Calibration

4.3.2. Analysis of Necessary Conditions

4.3.3. Analysis of Sufficient Conditions

4.3.4. Robustness Analysis

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aiken, L. S., West, S. G., & Reno, R. R. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Armour, J., Parnham, R., & Sako, M. (2022). Augmented lawyering. University of Illinois Law Review, 71, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2017). Job demands–resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22(3), 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Sanz-Vergel, A. (2023). Job demands–resources theory: Ten years later. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 10(1), 25–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A. B., Hakanen, J. J., Demerouti, E., & Xanthopoulou, D. (2007). Job resources boost work engagement, particularly when job demands are high. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99(2), 274–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Başer, M. Y., Büyükbeşe, T., & Ivanov, S. (2025). The effect of STARA awareness on hotel employees’ turnover intention and work engagement: The mediating role of perceived organisational support. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights, 8(2), 532–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bošković, A. (2021). Employee autonomy and engagement in the digital age: The moderating role of remote working. Ekonomski horizonti, 23(3), 231–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozkus, K. (2023). Organizational culture change and technology: Navigating the digital transformation. In M. Sarfraz, & W. U. H. Shah (Eds.), Organizational culture & change (Vol. 16, pp. 3–24). IntechOpen. [Google Scholar]

- Brislin, R. W. (1986). The wording and translation of research instruments. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, W., Khapova, S., Bossink, B., Lysova, E., & Yuan, J. (2020). Optimizing employee creativity in the digital era: Uncovering the interactional effects of abilities, motivations, and opportunities. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(3), 1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, U., Verma, B., & Mittal, A. (2025). Unveiling barriers to O2O technology platform adoption among small retailers in India: Insights into the role of digital ecosystem. Information Discovery and Delivery, 53(2), 248–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N., Zhao, X., & Wang, L. (2024). The effect of job skill demands under artificial intelligence embeddedness on employees’ job performance: A moderated double-edged sword model. Behavioral Sciences, 14(10), 974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, B., Lin, H., & Kong, Y. (2023). Challenge or hindrance? How and when organizational artificial intelligence adoption influences employee job crafting. Journal of Business Research, 164, 113987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clausen, T., Pedersen, L. R. M., Andersen, M. F., Theorell, T., & Madsen, I. E. (2022). Job autonomy and psychological well-being: A linear or a non-linear association? European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 31(3), 395–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, P., West, S. G., & Aiken, L. S. (2003). Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences (3rd ed.). Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Cornelis, I., Van Hiel, A., De Cremer, D., & Mayer, D. M. (2013). When leaders choose to be fair: Follower belongingness needs and leader empathy influences leaders’ adherence to procedural fairness rules. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 49, 605–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E. L., Ryan, R. M., Gagné, M., Leone, D. R., Usunov, J., & Kornazheva, B. P. (2001). Need satisfaction, motivation, and well-being in the work organizations of a former eastern bloc country: A cross-cultural study of self-determination. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27(8), 930–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dettmers, J., & Bredehöft, F. (2020). The ambivalence of job autonomy and the role of job design demands. Scandinavian Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 5(1), 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, J., & Kleinlogel, E. P. (2014). Wage cuts and managers’ empathy: How a positive emotion can contribute to positive organizational ethics in difficult times. Journal of Business Ethics, 119(4), 461–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J. R., & Lambert, L. S. (2007). Methods for integrating moderation and mediation: A general analytical framework using moderated path analysis. Psychological Methods, 12(1), 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiss, P. C. (2011). Building better causal theories: A fuzzy set approach to typologies in organization research. The Academy of Management Journal, 54(2), 393–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanti, T., Guidetti, G., Mazzei, E., Zappalà, S., & Toscano, F. (2021). Work from home during the COVID-19 outbreak: The impact on employees’ remote work productivity, engagement, and stress. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 63, e426–e432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, D. G. (2020). The importance of being resilient: Psychological well-being, job autonomy, and self-esteem of organization managers. Personality and Individual Differences, 155, 109731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebauer, H., Paiola, M., Saccani, N., & Rapaccini, M. (2021). Digital servitization: Crossing the perspectives of digitization and servitization. Industrial Marketing Management, 93, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gfrerer, A., Hutter, K., Füller, J., & Ströhle, T. (2021). Ready or not: Managers’ and employees’ different perceptions of digital readiness. California Management Review, 63, 23–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halbesleben, J. R. (2010). A meta-analysis of work engagement: Relationships with burnout, demands, resources, and consequences. Work Engagement: A Handbook of Essential Theory and Research, 8, 102–117. [Google Scholar]

- Holopainen, M., Saunila, M., & Ukko, J. (2023). Value creation paths of organizations undergoing digital transformation. Knowledge and Process Management, 30(2), 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höyng, M., & Lau, A. (2023). Being ready for digital transformation: How to enhance employees’ intentional digital readiness. Computers in Human Behavior Reports, 11, 100314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huu, P. T. (2023). Impact of employee digital competence on the relationship between digital autonomy and innovative work behavior: A systematic review. Artificial Intelligence Review, 56(12), 14193–14222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T. G., Hornung, S., & Rousseau, D. M. (2011). Change-supportive employee behavior: Antecedents and the moderating Role of time. Journal of Management, 37(6), 1664–1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, S. P., Spieth, P., & Söllner, M. (2024). Employee acceptance of digital transformation strategies: A paradox perspective. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 41(5), 999–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N., Mayfield, M., Mayfield, J., Sexton, S., & De La Garza, L. M. (2019). Empathetic leadership: How leader emotional support and understanding influences follower performance. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 26(2), 217–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, T. D., Rhemtulla, M., Gibson, K., & Schoemann, A. M. (2013). Why the items versus parcels controversy needn’t be one. Psychological Methods, 18(3), 285–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, K. J., Boer, D., & Voelpel, S. C. (2017). From listening to leading: Toward an understanding of supervisor listening within the framework of leader-member exchange theory. International Journal of Business Communication, 54(4), 431–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malo, M., Tremblay, I., & Brunet, L. (2016). Cognitive adjustment as an indicator of psychological health at work: Development and validation of a measure. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 92, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, A., Borg, V., & Clausen, T. (2019). Enhancing the social capital in industrial workplaces: Developing workplace interventions using intervention mapping. Evaluation and Program Planning, 72, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meske, C., & Junglas, I. (2021). Investigating the elicitation of employees’ support towards digital workplace transformation. Behaviour & Information Technology, 40(11), 1120–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montani, F., Setti, I., Sommovigo, V., Courcy, F., & Giorgi, G. (2020). Who responds creatively to role conflict? Evidence for a curvilinear relationship mediated by cognitive adjustment at work and moderated by mindfulness. Journal of Business and Psychology, 35(5), 621–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgeson, F. P., & Humphrey, S. E. (2006). The work design questionnaire (WDQ): Developing and validating a comprehensive measure for assessing job design and the nature of work. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(6), 1321–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muss, C., Tüxen, D., & Fürstenau, B. (2025). Empathy in leadership: A systematic literature review on the effects of empathetic leaders in organizations. Management Review Quarterly. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2012). Mplus version 7 user’s guide. Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Ni, D., Zheng, X., & Liang, L. H. (2023). How and when leader mindfulness influences team member interpersonal behavior: Evidence from a quasi-field experiment and a field survey. Human Relations, 76(12), 1940–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, X., Guo, J., & Wu, T. (2025). How ambivalence toward digital–AI transformation affects taking-charge behavior: A threat–rigidity theoretical perspective. Behavioral Sciences, 15(3), 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peschl, A., & Schüth, N. J. (2022). Facing digital transformation with resilience–operational measures to strengthen the openness towards change. Procedia Computer Science, 200, 1237–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P. M., Podsakoff, N. P., Williams, L. J., Huang, C., & Yang, J. (2024). Common method bias: It’s bad, it’s complex, it’s widespread, and it’s not easy to fix. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 11, 17–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poláková-Kersten, M., Khanagha, S., van den Hooff, B., & Khapova, S. N. (2023). Digital transformation in high-reliability organizations: A longitudinal study of the micro-foundations of failure. The Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 32(1), 101756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragin, C. C. (2006). Set relations in social research: Evaluating their consistency and coverage. Political Analysis, 14(3), 291–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragin, C. C. (2009). Redesigning social inquiry: Fuzzy sets and beyond. University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers, I., Armour, J., & Sako, M. (2023). How technology is (or is not) transforming law firms. Annual Review of Law and Social Science, 19, 299–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salovey, P., & Mayer, J. D. (1990). Emotional intelligence. Imagination, Cognition and Personality, 9, 185–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W. B., & Bakker, A. B. (2004). Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: A multi-sample study. Journal of Organizational Behavior: The International Journal of Industrial, Occupational and Organizational Psychology and Behavior, 25, 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, P., & Sting, F. J. (2020). Employees’ perspectives on digitalization-induced change: Exploring frames of industry 4.0. Academy of Management Discoveries, 6(3), 406–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selimović, J., Pilav-Velić, A., & Krndžija, L. (2021). Digital workplace transformation in the financial service sector: Investigating the relationship between employees’ expectations and intentions. Technology in Society, 66, 101640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakina, E., Parshakov, P., & Alsufiev, A. (2021). Rethinking the corporate digital divide: The complementarity of technologies and the demand for digital skills. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 162, 120405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A., & Hess, T. (2017). How chief digital officers promote the digital transformation of their companies. MIS Quarterly Executive, 16, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Skaaning, S. (2011). Assessing the robustness of crisp-set and fuzzy-set QCA results. Sociological Methods & Research, 40(2), 391–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spagnoli, P., & Molinaro, D. (2020). Negative (workaholic) emotions and emotional exhaustion: Might job autonomy have played a strategic role in workers with responsibility during the COVID-19 crisis lockdown? Behavioral Sciences, 10(12), 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spreitzer, G. M. (1995). Psychological empowerment in the workplace: Dimensions, measurement, and validation. The Academy of Management Journal, 38(5), 1442–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenkamp, H., & Dhanesh, G. S. (2023). Care-based relationship management during remote work in a crisis: Empathy, purpose, and diversity climate as emergent employee-organization relational maintenance strategies. Public Relations Review, 49(4), 102371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Q., & Robertson, J. L. (2019). How and when does perceived CSR affect employees’ engagement in voluntary pro-environmental behavior? Journal of Business Ethics, 155(2), 399–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valtonen, A., & Holopainen, M. (2025). Mitigating employee resistance and achieving well-being in digital transformation. Information Technology & People, 38(8), 42–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, M., & Shan, J. (2020). COVID-19 has accelerated digital transformation, but may have made it harder not easier. MIS Quarterly Executive, 19(3), 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, E., Büttgen, M., & Bartsch, S. (2022). How to take employees on the digital transformation journey: An experimental study on complementary leadership behaviors in managing organizational change. Journal of Business Research, 143, 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, L. J., Vandenberg, R. J., & Edwards, J. R. (2009). 12 structural equation modeling in management research: A guide for improved analysis. Academy of Management Annals, 3, 543–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y., Hu, X., Wei, J., & Marinova, D. (2023). The effects of attitudes toward knowledge sharing, perceived social norms and job autonomy on employees’ knowledge-sharing intentions. Journal of Knowledge Management, 27(7), 1889–1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X., Liao, T., Wang, Y., Ren, L., & Zeng, J. (2024). The association between digital addiction and interpersonal relationships: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 114, 102501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y., Shamim, S., De Massis, A., & Gao, D. (2025). Defensive routines as coping mechanisms against technostress: Roles of digital leadership and employee goal orientation. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, C. A., Men, L. R., & Ferguson, M. A. (2021). Examining the effects of internal communication and emotional culture on employees’ organizational identification. International Journal of Business Communication, 58(2), 169–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, C. A., Thelen, P. D., & Walden, J. (2023). How empathetic leadership communication mitigates employees’ turnover intention during COVID-19-related organizational change. Management Decision, 61(5), 1413–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S., Zhang, L., Peng, L., Zhou, H., & Hu, F. (2024). Enterprise pollution reduction through digital transformation? Evidence from Chinese manufacturing enterprises. Technology in Society, 77, 102520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, E. (2020). The “too-much-of-a-good-thing” effect of job autonomy and its explanation mechanism. Psychology, 11, 299–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q., & Shi, X. (2025). How does platform leadership promote employee commitment to digital transformation?—A moderated serial mediation model from the stress perspective. International Journal of Information Management, 83, 102900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q., Zang, L., & Fu, F. (2024). Influence of employee impact on their evaluation of enterprise digital capability: A mediated moderation model. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 11(1), 1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.57 | 0.50 | -- | ||||||||

| 1.70 | 0.68 | −0.08 | -- | |||||||

| 3.85 | 0.76 | 0.04 | −0.20 *** | -- | ||||||

| 2.01 | 0.92 | −0.13 ** | 0.14 ** | 0.09 | -- | |||||

| 6.12 | 4.18 | −0.12 * | 0.63 *** | −0.26 *** | 0.13 ** | -- | ||||

| 5.48 | 0.92 | −0.04 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.31 *** | 0.06 | 0.84 | |||

| 5.74 | 0.56 | −0.02 | 0.09 | 0.12 * | 0.21 *** | 0.09 | 0.50 *** | 0.89 | ||

| 5.24 | 1.05 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.13 ** | 0.03 | 0.44 *** | 0.62 *** | 0.95 | |

| 5.15 | 0.98 | 0.07 | −0.04 | 0.10 * | 0.13 ** | 0.03 | 0.35 *** | 0.51 *** | 0.60 *** | 0.85 |

| Variables | Cognitive Adjustment in the Workplace | Digital Transformation-Supportive Behavior | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | LLCI | ULCI | β | SE | LLCI | ULCI | |

| Constant | 3.47 *** | 0.22 | [3.04, | 3.90] | −0.36 | 0.48 | [−1.31, | 0.58] |

| Control variables | ||||||||

| Gender | 0.01 | 0.05 | [−0.09, | 0.10] | 0.16 * | 0.08 | [0.00, | 0.33] |

| Age | 0.08 | 0.04 | [0.00, | 0.17] | −0.16 * | 0.08 | [−0.31, | −0.01] |

| Educational background | 0.11 ** | 0.03 | [0.04, | 0.17] | 0.06 | 0.06 | [−0.06, | 0.17] |

| Professional rank | 0.02 | 0.03 | [−0.04, | 0.07] | 0.01 | 0.05 | [−0.08, | 0.10] |

| Tenure | 0.00 | 0.01 | [−0.01, | 0.02] | 0.02 | 0.01 | [−0.01, | 0.04] |

| Independent variable | ||||||||

| Digital transformation job autonomy | 0.30 *** | 0.03 | [0.25, | 0.35] | 0.13 * | 0.05 | [0.03, | 0.24] |

| Mediator | ||||||||

| Cognitive adjustment in the workplace | 0.78 *** | 0.09 | [0.61, | 0.94] | ||||

| Variables | Cognitive Adjustment in the Workplace | Digital Transformation-Supportive Behavior | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | LLCI | ULCI | β | SE | LLCI | ULCI | |

| Constant | 5.19 *** | 0.15 | [4.90, | 5.47] | 2.90 *** | 0.54 | [1.83, | 3.96] |

| Control variables | ||||||||

| Gender | 0.00 | 0.04 | [−0.08, | 0.08] | 0.15 * | 0.07 | [0.00, | 0.30] |

| Age | 0.05 | 0.04 | [−0.03, | 0.12] | −0.18 ** | 0.07 | [−0.32, | −0.04] |

| Educational background | 0.10 ** | 0.03 | [0.04, | 0.15] | 0.09 | 0.05 | [−0.01, | 0.19] |

| Professional rank | 0.02 | 0.02 | [−0.02, | 0.07] | 0.03 | 0.04 | [−0.05, | 0.12] |

| Tenure | 0.01 | 0.01 | [−0.01, | 0.02] | 0.02 | 0.01 | [0.00, | 0.04] |

| Independent variable | ||||||||

| Digital transformation job autonomy | 0.18 *** | 0.03 | [0.13, | 0.23] | 0.09 | 0.05 | [−0.01, | 0.19] |

| Mediator | ||||||||

| Cognitive adjustment in the workplace | 0.30 *** | 0.09 | [0.12, | 0.48] | ||||

| Moderator | ||||||||

| Leader empathy | 0.27 *** | 0.02 | [0.23, | 0.31] | 0.45 *** | 0.05 | [0.36, | 0.54] |

| Interaction term | ||||||||

| Digital transformation level job autonomy × Leader empathy | 0.05 * | 0.02 | [0.01, | 0.08] | 0.10 ** | 0.04 | [0.03, | 0.17] |

| Variables | High-Level Digital Transformation-Supportive Behavior | Non-High-Level Digital Transformation-Supportive Behavior | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consistency | Coverage | Consistency | Coverage | |

| Digital transformation job autonomy | 0.742 | 0.773 | 0.627 | 0.567 |

| ~ Digital transformation job autonomy | 0.584 | 0.643 | 0.749 | 0.716 |

| Cognitive adjustment in the workplace | 0.777 | 0.792 | 0.599 | 0.530 |

| ~ Cognitive adjustment in the workplace | 0.539 | 0.608 | 0.766 | 0.749 |

| Leader empathy | 0.809 | 0.822 | 0.595 | 0.525 |

| ~ Leader empathy | 0.532 | 0.602 | 0.798 | 0.784 |

| Variables | High-Level Digital Transformation-Supportive Behavior | Non-High-Level Digital Transformation-Supportive Behavior | |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | H2 | NH1 | |

| Digital transformation job autonomy | ● | ⊗ | |

| Cognitive adjustment in the workplace | ● | ⊗ | |

| Leader empathy | ● | ● | ⊗ |

| Consistency | 0.893 | 0.878 | 0.847 |

| Raw coverage | 0.676 | 0.704 | 0.574 |

| Unique coverage | 0.058 | 0.086 | 0.574 |

| Overall solution coverage | 0.762 | 0.574 | |

| Overall solution consistency | 0.861 | 0.847 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, B.; Cheng, S.; Zhou, Q.; Shi, X. The Impact of Digital Transformation Job Autonomy on Lawyers’ Support for Law Firms’ Digital Initiatives: The Mediating Role of Cognitive Adjustment and the Moderating Effect of Leaders’ Empathy. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 260. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15070260

Liu B, Cheng S, Zhou Q, Shi X. The Impact of Digital Transformation Job Autonomy on Lawyers’ Support for Law Firms’ Digital Initiatives: The Mediating Role of Cognitive Adjustment and the Moderating Effect of Leaders’ Empathy. Administrative Sciences. 2025; 15(7):260. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15070260

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Bowei, Shuang Cheng, Qiwei Zhou, and Xueting Shi. 2025. "The Impact of Digital Transformation Job Autonomy on Lawyers’ Support for Law Firms’ Digital Initiatives: The Mediating Role of Cognitive Adjustment and the Moderating Effect of Leaders’ Empathy" Administrative Sciences 15, no. 7: 260. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15070260

APA StyleLiu, B., Cheng, S., Zhou, Q., & Shi, X. (2025). The Impact of Digital Transformation Job Autonomy on Lawyers’ Support for Law Firms’ Digital Initiatives: The Mediating Role of Cognitive Adjustment and the Moderating Effect of Leaders’ Empathy. Administrative Sciences, 15(7), 260. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15070260