KPIs for Digital Accelerators: A Critical Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

- How do digital accelerators impact startup economic and operational performance?

- Which economic and client-focused KPIs can effectively measure digital accelerator impact on startup success?

2. Theoretical Framework

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Exclusion Criteria

3.2. Search Strategies

4. Evaluate Accelerators

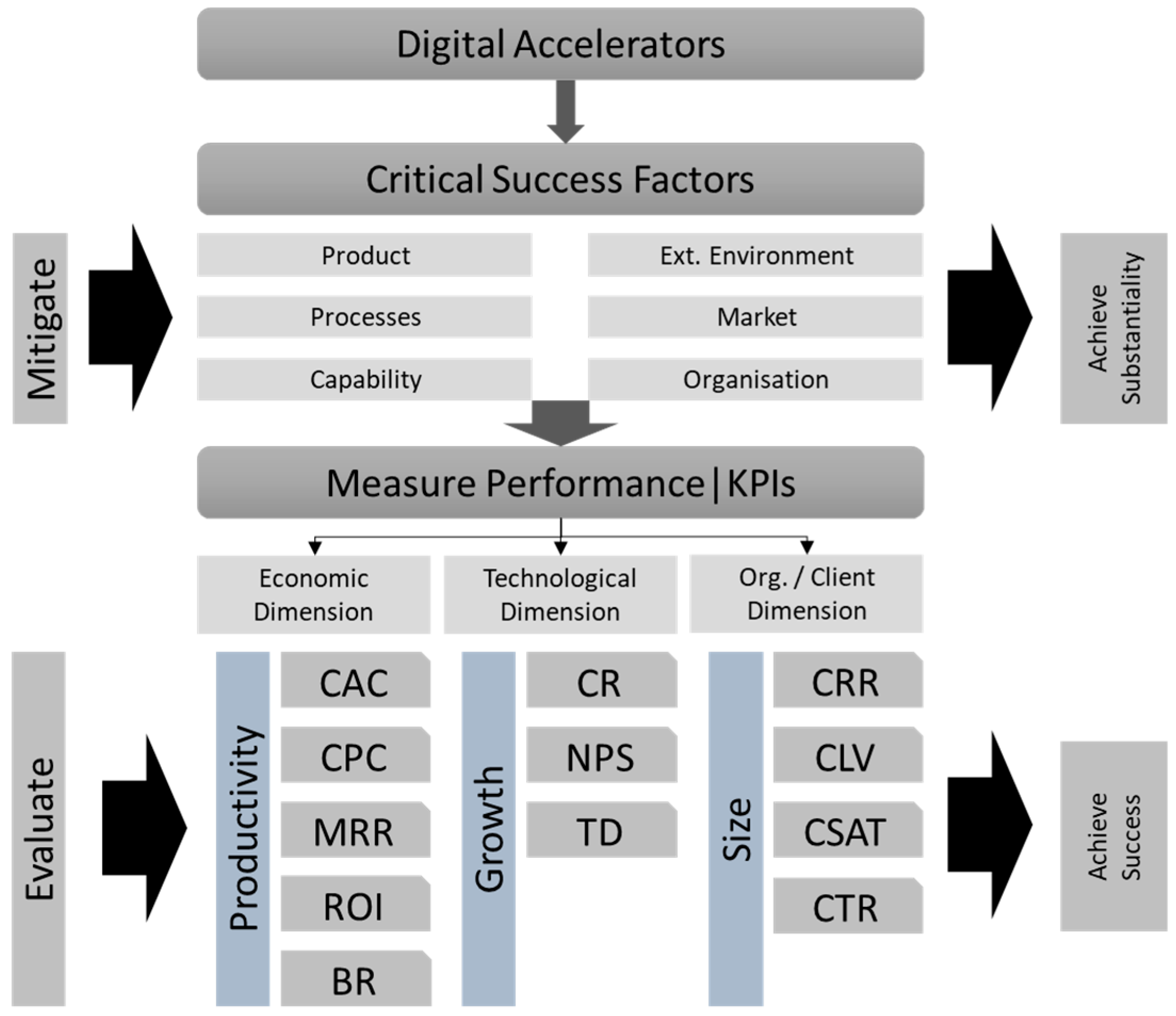

4.1. Metrics and Indicators

- (a)

- Productivity and profitability categories comprise metrics measuring the efficiency of resource utilization and operational effectiveness, like Customer Acquisition Cost (CAC), Cost Per Conversion (CPC), and burn rate efficiency. So, the relationship is clear in relation to the economic dimensions, as the metrics are primarily economic indicators that assess resource optimization.

- (b)

- Growth category aggregates metrics to track expansion and development over time, like Monthly Recurring Revenue (MRR) growth, Network Expansion Rate, Innovation Pipeline strength. This category spans all dimensions, measuring progressive improvement.

- (c)

- Size category comprises metrics indicating the scale and reach of operations like Customer Retention Rate (CRR), Total Active Users, and market share. So, the relationship is clear towards organizational dimension as the metrics are primarily organizational/client-focused, measuring operational scale.

4.2. Critical Success Factors and KPIs

- What resources does a target startup still need to ensure success?

- Given the size of the potential market, what is the ratio between the cost of those additional resources and the potential revenue over time?

- How quickly will we be able to tell if things are going off track?

- How soon will we reach a confidence level high enough to trigger further investment?

- At what points will this company be more valuable as a private company, a public company, or an acquisition target?

5. Conceptual Framework

5.1. Economical Dimension

5.2. Organizational/Client Dimension

5.3. Technological Dimension

6. Conclusions

7. Future Research Directions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ang, L., & Buttle, F. (2006). Customer retention management processes. European Journal of Marketing, 40(1/2), 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assenova, V., & Amit, R. H. (2022). Poised for growth: Cohorts’ knowledge and its effects on post-acceleration startup growth. SSRN Electronic Journal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audretsch, D. B. (2012). Determinants of high-growth entrepreneurship. Report Prepared for the OECD/DBA International Workshop on High-Growth Firms: Local Policies and Local Determinants. OECD. [Google Scholar]

- Avgeriou, P., Kruchten, P., Ozkaya, I., & Seaman, C. (2016). Managing technical debt in software engineering (dagstuhl seminar 16162). Dagstuhl Reports, 6(4), 110–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, C., & Pistrang, N. (2005). Quality criteria under methodological pluralism: Implications for conducting and evaluating research. American Journal of Community Psychology, 35(3–4), 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, M., Hong, N. P. C., Katz, D. S., Lamprecht, A., Martinez-Ortiz, C., Psomopoulos, F., Harrow, J., Castro, L. J., Gruenpeter, M., Martinez, P. A., & Honeyman, T. (2022). Introducing the FAIR Principles for research software. Scientific Data, 9(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, T., & Utikal, H. (2021). How to support startups in developing a sustainable business model: The case of an European social impact accelerator. Sustainability, 13(6), 3337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blank, S. G., & Dorf, B. (2012). The startup owner’s manual: The step-by-step guide for building a great company. K & S Ranch. [Google Scholar]

- Cánovas-Saiz, L., March-Chordà, I., & Yagüe-Perales, R. M. (2020). New evidence on accelerator performance based on funding and location. European Journal of Management and Business Economics, 29(3), 217–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, B. K. (2019). A General framework for studying the evolution of the digital innovation ecosystem: The case of big data. International Journal Infrastructure Management, 45, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J., Reilly, R. R., & Lynn, G. S. (2005). The Impacts of speed-to-market on new product success: The moderating effects of uncertainty. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 52, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chorev, S., & Anderson, A. R. (2006). Success in Israeli high-tech startups; Critical factors and process. Technovation, 26(2), 162–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coad, A., Segarra, A., & Teruel, M. (2016). Innovation and firm growth: Does firm age play a role? Research Policy, 45(2), 387–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S., & Hochberg, Y. V. (2014). Accelerating startups: The seed accelerator phenomenon. Elsevier BV. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, R. G. (2021). Accelerating innovation: Some lessons from the pandemic (J. Spanjol, & C. H. Noble, Eds.). Wiley. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotter, S. (2002). Taking the measure of e-marketing success: Don’t just cross your fingers and hope your e-marketing initiatives are paying off, measure the payoff. (Strategic Metrics). Journal of Business Strategy, 23(2), 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalmarco, G., Hulsink, W., & Zawislak, P. A. (2019). New perspectives on university-industry relations: An analysis of the knowledge flow within two sectors and two countries. Technology Analysis and Strategic Management, 31(11), 1314–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damm, R., & Rodríguez Monroy, C. (2011). A review of the customer lifetime value as a customer profitability measure in the context of customer relationship management. Intangible Capital, 7(2), 261–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fried, H. O., & Tauer, L. W. (2015). An entrepreneur performance index. Journal of Productivity Analysis, 44(1), 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, N. (2009). ‘Do you know what I mean?’: The use of a pluralistic narrative analysis approach in the interpretation of an interview. Qualitative Research, 9(1), 9–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, A., & Unwin, L. (2005). Older and wiser?: Workplace learning from the perspective of experienced employees. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 24, 21–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gali. (2021). Does acceleration work? Five years of evidence from the global accelerator learning initiative. Available online: https://www.galidata.org/assets/report/pdf/Does%20Acceleration%20Work_EN.pdf (accessed on 23 February 2025).

- Geissbauer, R., Schrauf, S., & Morr, J. (2019). Digital product development 2025: Agile, collaborative, AI driven and customer centric. Available online: https://www.pwc.de/de/digitale-transformation/pwc-studie-digital-product-development-2025.pdf (accessed on 23 February 2025).

- Gov.UK. (2019). The impact of business accelerators and incubators in the UK. BEIS research paper number: 2019/009. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-impact-of-business-accelerators-and-incubators-in-the-uk (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Grant, M., & Booth, A. (2009). A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information and Libraries Journal, 26(2), 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, A. (2002). Product development cycle time for business-to-business products. Industrial Marketing Management, 31(4), 291–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griva, A., Kotsopoulos, D., Karagiannaki, A., & Zamani, E. D. (2023). What do growing early-stage digital startups look like? A mixed-methods approach. International Journal of Information Management, 69, 102427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinings, B., Gegenhuber, T., & Greenwood, R. (2018). Digital innovation and transformation: An institutional perspective. Elsevier BV. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyett, N., Kenny, A., & Dickson-Swift, V. (2014). Methodology or method? A critical review of qualitative case study reports. Informa UK Limited. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ickin, S., Ahmed, J., Johnsson, A., & Gustafsson, J. (2019, June 5–7). On network performance indicators for network promoter score estimation. 2019 Eleventh International Conference on Quality of Multimedia Experience (QoMEX), Berlin, Germany. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasek, P., Vrana, L., Sperkova, L., Smutny, Z., & Kobulsky, M. (2018). Modeling and application of customer lifetime value in online retail. Informatics, 5(1), 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen, B. (2018, April 21–24). Agile stage gate at Danfoss. GEMBA Innovation Conference, Copenhagen, Denmark. [Google Scholar]

- Kirchmer, M., & Franz, P. (2020). Process reference models: Accelerator for digital transformation. In Lecture notes in business information processing (pp. 20–37). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konyuhov, V. Y., Gladkih, A. M., & Zott, R. S. (2020). Accelerator as an effective replacement of a business incubator in the Irkutsk region. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 1582(1), 012045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristin, D. M., Chandra, Y. U., & Masrek, M. N. (2022, August 26–28). Critical success factor of digital startup business to achieve sustainability: A systematic literature review. 2022 International Conference on Information Management and Technology (ICIMTech), Chengdu, China. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupp, M., Marval, M., & Borchers, P. (2017). Corporate accelerators: Fostering innovation while bringing together startups and large firms. Journal of Business Strategy, 38(6), 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laitinen, E. K. (2017). Profitability Ratios in the Early Stages of a Startup. The Journal of Entrepreneurial Finance, 19(2), 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langerak, F. (2010). Accelerated product development. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livne, G., Simpson, A., & Talmor, E. (2011). Do customer acquisition cost, retention and usage matter to firm performance and valuation? Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, 38(3–4), 334–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lofsten, H. (2016). New technology-based firms and their survival: The importance of businessnetworks, and entrepreneurial business behaviour and competition. The Journal of the Local Economy Policy Unit, 31(3), 393–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markus, M. L., & Loebbecke, C. (2013). Commoditized digital processes and business community platforms: New opportunities and challenges for digital business strategies. MIS Quarterly: Management Information Systems, 37(2), 649–654. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/43825930 (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Marr, B. (2012). Key performance indicators (KPI): The 75 measures every manager needs to know. Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Márquez, E. (2022). Developments and global trends in the education and business sectors in the post-COVID-19 period. In J. Saiz-Alvarez (Ed.), Handbook of research on emerging business models and the new world economic order (pp. 304–325). IGI Global. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migliaccio, G., & Pavone, P. (2020). Italian innovative startup cohorts: An empirical survey on profitability. In New metropolitan perspectives (pp. 834–843). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, M. E., Østergaard Madsen, C., & Lungu, M. F. (2020). Technical debt management: A systematic literature review and research agenda for digital government. In Lecture notes in computer science (pp. 121–137). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onesti, G., Monaco, E., & Palumbo, R. (2022). Assessing the Italian innovative startups performance with a composite index. Administrative Sciences, 12(4), 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J., Kuo, T., & Bretholt, A. (2010). Developing a new key performance index for measuring service quality. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 110(6), 823–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmenter, D. (2015). Key performance indicators: Developing, implementing, and using winning KPIs. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Patil, P., Deshpande, Y., Tomos, F., Kumar, N., Clifton, N., & Hyams-Ssekasi, D. (2019). Women entrepreneurship: A journey begins. In F. Tomos, N. Kumar, N. Clifton, & D. Hyams-Ssekasi (Eds.), Women entrepreneurs and strategic decision making in the global economy (pp. 99–118). IGI Global. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichheld, F. F. (2003). The one number you need to grow. Harvard Business Review, 81(12), 46–124. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rios, N., Mendonça Neto, M. G. D., & Spínola, R. O. (2018). A tertiary study on technical debt: Types, management strategies, research trends, and base information for practitioners. Information and Software Technology, 102, 117–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ripsas, S., Schaper, B., & Tröger, S. (2018). A startup cockpit for the proof-of-concept. In Handbuch entrepreneurship (pp. 263–279). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roche, P. (2006). Strengthening relationships through key performance indicators. Paper and Packaging, 47(5), 19–48. [Google Scholar]

- Saura, J. R., Palos-Sánchez, P., & Cerdá Suárez, L. M. (2017). Understanding the Digital Marketing Environment with KPIs and Web Analytics. Future Internet, 9(4), 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setijono, D., & Dahlgaard, J. J. (2007). Customer value as a key performance indicator (KPI) and a key improvement indicator (KII). Measuring Business Excellence, 11(2), 44–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S. K., & Meyer, K. E. (2019). Industrializing innovation—The next revolution. Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva Júnior, C. R., Siluk, J. C. M., Neuenfeldt Júnior, A., Francescatto, M., & Michelin, C. (2022). A competitiveness measurement system of Brazilian startups. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 72(10), 2919–2948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slávik, Š., Hanák, R., Mišúnová-Hudáková, I., & Mišún, J. (2022). Impact of strategy on business performance of startup. Polish Journal of Management Studies, 26(2), 341–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smetanková, J., Krajníková, K., Mésároš, P., & Behúnová, A. (2020). Analysis of customer acquisition cost and innovation performance cost After BIM technology implementation. In EAI/Springer innovations in communication and computing. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K. A., Willis, R. J., & Brooks, M. (2000). An analysis of customer retention and insurance claim patterns using data mining: A case study. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 51(5), 532–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toor, S.-R., & Ogunlana, S. O. (2010). Beyond the ‘iron triangle’: Stakeholder perception of key performance indicators (KPIs) for large-scale public sector development projects. International Journal of Project Management, 28(3), 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tritoasmoro, I. I., Ciptomulyono, U., Dhewanto, W., & Taufik, T. A. (2022). Determinant factors of lean startup-based incubation metrics on post-incubation startup viability: Case-based study. Journal of Science and Technology Policy Management, 15(1), 178–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unterkalmsteiner, M., Abrahamsson, P., Wang, X. F., Nguyen-Duc, A., Shah, S., Bajwa, S. S., Baltes, G. H., Conboy, K., Cullina, E., Dennehy, D., Edison, H., Fernandez-Sanchez, C., Garbajosa, J., Gorschek, T., Klotins, E., Hokkanen, L., Kon, F., Lunesu, I., Marchesi, M., … Yagüe, A. (2016). Software startups—A research agenda. e-Informatica Software Engineering Journal, 10(1), 89–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela-Fernández, L., Nicolas, C., Gil-Lafuente, J., & Merigó, J. M. (2016). Fuzzy indicators for customer retention. International Journal of Engineering Business Management, 8, 184797901667052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyas, R., Prasad, B. G. M., Vamshidhar, H. K., & Kumar, S. (2018, December 19–21). Predicting inactiveness in telecom (prepaid) sector: A complex bigdata application. 2018 International Conference on Information Technology (ICIT), Bhubaneswar, India. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. (2025). How business accelerators can boost startup growth. Available online: https://www.ifc.org/en/insights-reports/2025/how-business-accelerators-can-boost-startup-growth (accessed on 23 February 2025).

- Yun, S., Choi, J., de Oliveira, D. P., & Mulva, S. P. (2016). Development of performance metrics for phase-based capital project benchmarking. International Journal of Project Management, 34(3), 389–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dimension/Categories | Indicator/Measurement |

|---|---|

| Profitability | EBITDA |

| EBITDA/sales | |

| Return on asset (ROA) | |

| Return on investment (ROI) | |

| Return on sale (ROS) | |

| Revenue generated | |

| Return on equity (ROE) | |

| Growth | Turnover |

| Number of successful exits | |

| Customer acquisition | |

| Profit | |

| Resources | |

| Capabilities | |

| Productivity | Turnover per employee |

| Value added per employee | |

| Turnover/staff costs | |

| Size | Production value |

| Revenues from sales of goods and services |

| Latent Variable | Critical Factor |

|---|---|

| Product | Digitalization |

| Novelty/innovativeness | |

| Product-oriented | |

| Value creation of product | |

| Functionality of product | |

| Profitable | |

| System quality | |

| Efficiency of digital product | |

| Effectiveness of digital product | |

| Platform | |

| Pricing | |

| Product benefit | |

| Scope | |

| Service quality | |

| Usability of mobile application | |

| The value proposition of the product | |

| External | Network |

| Economic impact | |

| Environment impact | |

| Business ecosystem impact | |

| Cognition | |

| Competitor | |

| External pressure | |

| Process | Learning |

| Accelerator/incubator capability | |

| Accelerator/incubator | |

| Business process | |

| Incubation process | |

| Mentoring | |

| Market | Market-oriented |

| User satisfaction | |

| Marketing and promotion | |

| Customer loyalty | |

| User experience | |

| Capability | Skill and experience |

| Resources | |

| Self-efficacy | |

| Behavioral intention | |

| Organizational | Funding |

| Internal management | |

| Risk assessment | |

| Employee satisfaction |

| CSF | Linked KPIs | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Product CSF | Technical debt (TD), conversion rate (CR), innovation adoption rate. | Product quality directly impacts user experience and market acceptance. |

| External CSF | Funding success rate, network diversity index, partnership formation rate. | External relationships provide essential resources and opportunities. |

| Process CSF | Time-to-prototype, idea-to-implementation ratio, operational efficiency metrics. | Process optimization affects speed and quality of deliverables. |

| Market CSF | Customer satisfaction (CSAT), net promoter score (NPS), market share growth. | Market understanding drives customer-centric performance. |

| Capability CSF | Skill Development Assessment Score, Mentor Satisfaction Score, R&D Productivity. | Organizational capabilities determine execution effectiveness. |

| Organizational CSF | Employee Engagement, Retention Rates, cultural assessment scores. | Internal organizational health affects overall performance. |

| Dimension | KPI/Metric | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Economic/Organizational | Profit and sales | Jørgensen (2018) Silva Júnior et al. (2022) Langerak (2010) Tritoasmoro et al. (2022) Slávik et al. (2022) |

| Mean sales growth and mean yearly sales | ||

| Development costs | ||

| Cycle time and product quality | ||

| Innovative profile | ||

| Intellectual property protection | ||

| R&D | ||

| Available resources | ||

| Absorptive capacity | ||

| Financial capability | ||

| Technological capacity | ||

| Dynamic capacity | ||

| Value creation | ||

| Competitive strategies | ||

| Organization quality | ||

| Organization culture | ||

| MVP | ||

| PS fit | ||

| Business model attractiveness | ||

| Team agility | ||

| Pivoting ability | ||

| Early adopter | ||

| Technological/Industry 4.0 Technologies | Simulation | Silva Júnior et al. (2022) |

| Big data and analytics | ||

| Internet of Things | ||

| Cloud computing | ||

| Cyber–physical systems | ||

| Cybersecurity | ||

| Collaborative robotics | ||

| Augmented reality | ||

| Additive manufacturing | ||

| Systems integration | ||

| Cultural/Human | Employee’s education level | Silva Júnior et al. (2022) |

| Founder characteristics | ||

| Employee’s satisfaction | ||

| Capital invested by the entrepreneur | ||

| Founding team experience | ||

| Employee’s commitment |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rodrigues, N.J.P. KPIs for Digital Accelerators: A Critical Review. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 258. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15070258

Rodrigues NJP. KPIs for Digital Accelerators: A Critical Review. Administrative Sciences. 2025; 15(7):258. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15070258

Chicago/Turabian StyleRodrigues, Nuno J. P. 2025. "KPIs for Digital Accelerators: A Critical Review" Administrative Sciences 15, no. 7: 258. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15070258

APA StyleRodrigues, N. J. P. (2025). KPIs for Digital Accelerators: A Critical Review. Administrative Sciences, 15(7), 258. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15070258