Developing a Supportive Organisational Culture for Continuous Improvement in Manufacturing Firms in Saudi Arabia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Relationship Between Organisational Culture and Continuous Improvement

2.2. Continuous Improvement in Saudi Manufacturing Firms

2.3. Gap Analysis and Research Objective

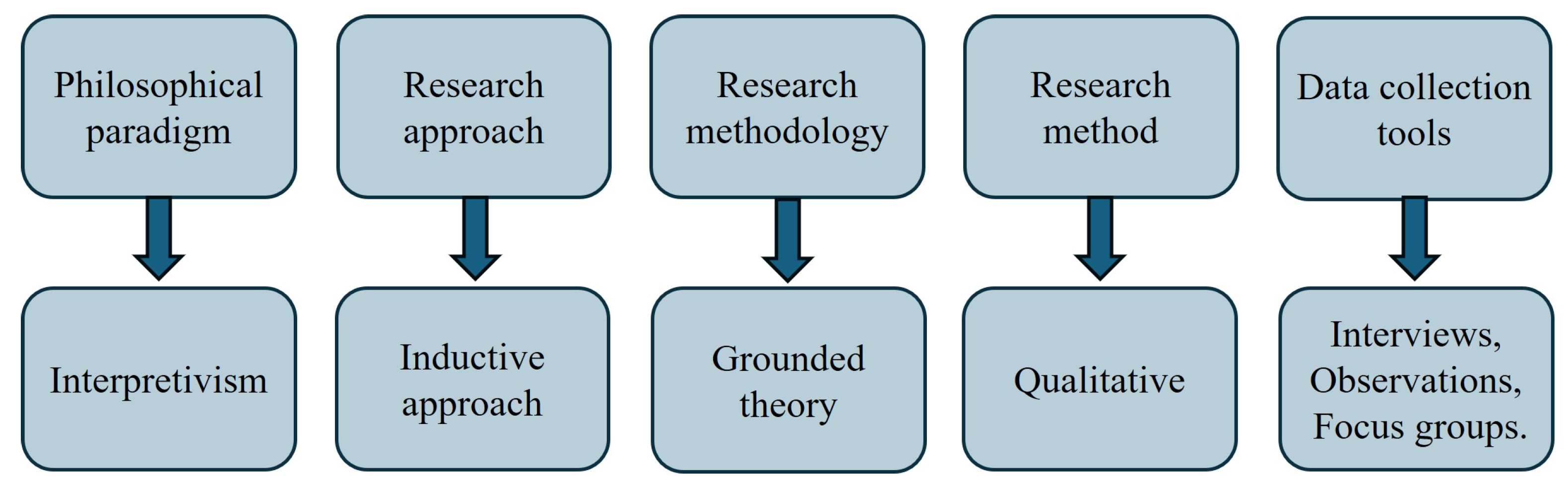

3. Methodology

4. Data Gathering and Analysis

4.1. Data Gathering

4.1.1. Participant Description

4.1.2. Pilot Study

4.1.3. Main Interviews Phase

4.2. Data Analysis

4.2.1. Data Analysis Procedure (Stage One)

- Enhancing communication for employee collaboration was considered vital for continuous improvement. It enhances information sharing, productivity, and collaboration.

- Cooperation towards formulation of new ideas leads to innovation through diverse perspectives and an environment conducive to exchanging and implementing ideas.

- Problem identification involves seeking out issues, taking corrective actions, and educating operators to prevent recurrence. It contributes to effective problem-solving through soft skills like active listening, respectful communication, and cultural awareness.

- Fostering positive social relationships within the organisation develops CI by facilitating collaboration, communication, and innovation for efficiency. These connections enhance collaboration, innovation, open communication channels, mutual support and trust.

- Facilitating collaborative team research fuelled innovation, collaboration, and learning, with teams exploring new ideas and seeking enhancements. It leads to a sense of collective ownership and is a driving force for improvement.

- Prioritising employee well-being includes ensuring access to physical and mental health resources, promoting work-life balance, and cultivating an inclusive culture. It increases employee engagement, productivity, collaboration, creativity, and problem-solving capacity.

- Maximising employees’ efficiency maintains effective performance through ongoing skill development in employees and a culture centred around efficiency, innovation and problem-solving.

- Cultivating employee motivation for CI mostly utilises methods like meetings and feedback channels. It enhances commitment to the organisation and to CI initiatives.

- Employees’ resistance to change is a significant hurdle in the path of continuous improvement. Fostering an open, transparent, and trusting culture is essential to overcoming these barriers.

- Establishing effective training programs for trainees insures investing in comprehensive support, learning, and skill-building opportunities. It provides the bedrock of operational excellence and innovation through increased efficiency and adaptability.

- Embracing flexibility in work conditions to foster improvement allows many different perspectives and skills to enhance problem-solving, creativity, and innovation. It maintains employee focus and efficiency while accommodating personal needs.

- The risk of expertise loss within the organisation is a significant obstacle to continuous improvement. Strategies must be implemented to retain and transfer knowledge to mitigate the risks.

- Shortage of workforce presents a considerable challenge to CI efforts in operations. Focusing on flexibility, collaboration, and a learning-oriented approach helps overcome workforce limitations.

- Implementing regular evaluation of organisational activities is a key driver for CI in operations. It maintains a focus on goals and process optimisation.

- Strengthening employee relations is fundamental to driving CI in manufacturing environments. Healthy interactions enhance motivation, performance, and contribution to improvement initiatives.

- Embracing employee diversity for improvement significantly contributes to CI through enhanced collaboration, teamwork, decision-making and innovative solutions.

- Promoting employee engagement in CI initiatives empowers employees to address challenges head-on and encourages experimentation and innovation.

- Creating a supportive work environment prioritises employee well-being, growth, and success, enabling open expression and innovation without fear.

- Addressing customer complaints as improvement opportunities reflects an organisation’s commitment to excellence and customer satisfaction. It instils responsibility and responsiveness in employees.

- Implementing supplier engagement policies for collaborative improvement efforts enhances product quality, efficiency, innovation and mutually beneficial relationships.

- Establishing effective employee monitoring mechanisms aligns employee performance with organisational goals and drives CI.

- Lack of moral incentives can lead to a decline in employee motivation and stagnation in improvement efforts.

- Ensuring fair employee salary structures promotes motivation, job satisfaction and dedication to the company’s success.

- Promoting ethical behaviour guides employees to make wise decisions and adhere to ethical standards, maintaining integrity and progress.

- Top management support for improvement initiatives shapes the environment and culture of a company, fostering innovation and long-term success.

- Encouraging employee independence in improvement processes gives employees the independence to exercise decision-making, take responsibility, and contribute significantly to improvement efforts.

- Ensuring high-quality standards in organisational processes drives a culture of excellence and CI through responsibility, attention to detail and accountability.

- Incorporating staff opinions in decision-making promotes inclusivity, empowerment and innovation.

- Implementing effective employee performance management strategies ensures operations are aligned with organisational goals.

- Establishing clear goal setting for improvement gives employees precise objectives that direct efforts towards key organisational objectives.

- Cultivating a healthy work environment to enhance CI efforts encompasses physical safety, work-life balance and positive relationships, fostering innovation and productivity.

- Supporting risk-taking for innovation encourages employees to challenge the status quo and provide novel solutions, fostering experimentation and learning.

- Implementing a comprehensive system for tracking work progress from initiation to completion ensures every phase is accountable, promoting transparency, efficiency, and timely decisions.

- Conducting regular staff meetings to facilitate facilitates communication, collaboration, problem-solving and a shared purpose.

- Promoting effective planning strategies to support CI is recognised as essential for operational optimisation.

- Poor supplier relationships can lead to delays and increased costs, hindering collaboration, innovation, best practice sharing.

- An internal violation committee maintains integrity by investigating and addressing policy or ethics breaches.

- Promoting continuous learning within an organisation keeps employees current on trends and advances knowledge and skills.

- Emphasising data-driven decision-making for CI facilitates systematic process improvements by identifying inefficiencies or quality issues.

4.2.2. Data Analysis Procedure (Stage Two)

4.2.3. Comparison with Other Studies

4.2.4. A Tool for Assessing the Proximity of Companies to an Ideal CI Culture State Across These Themes

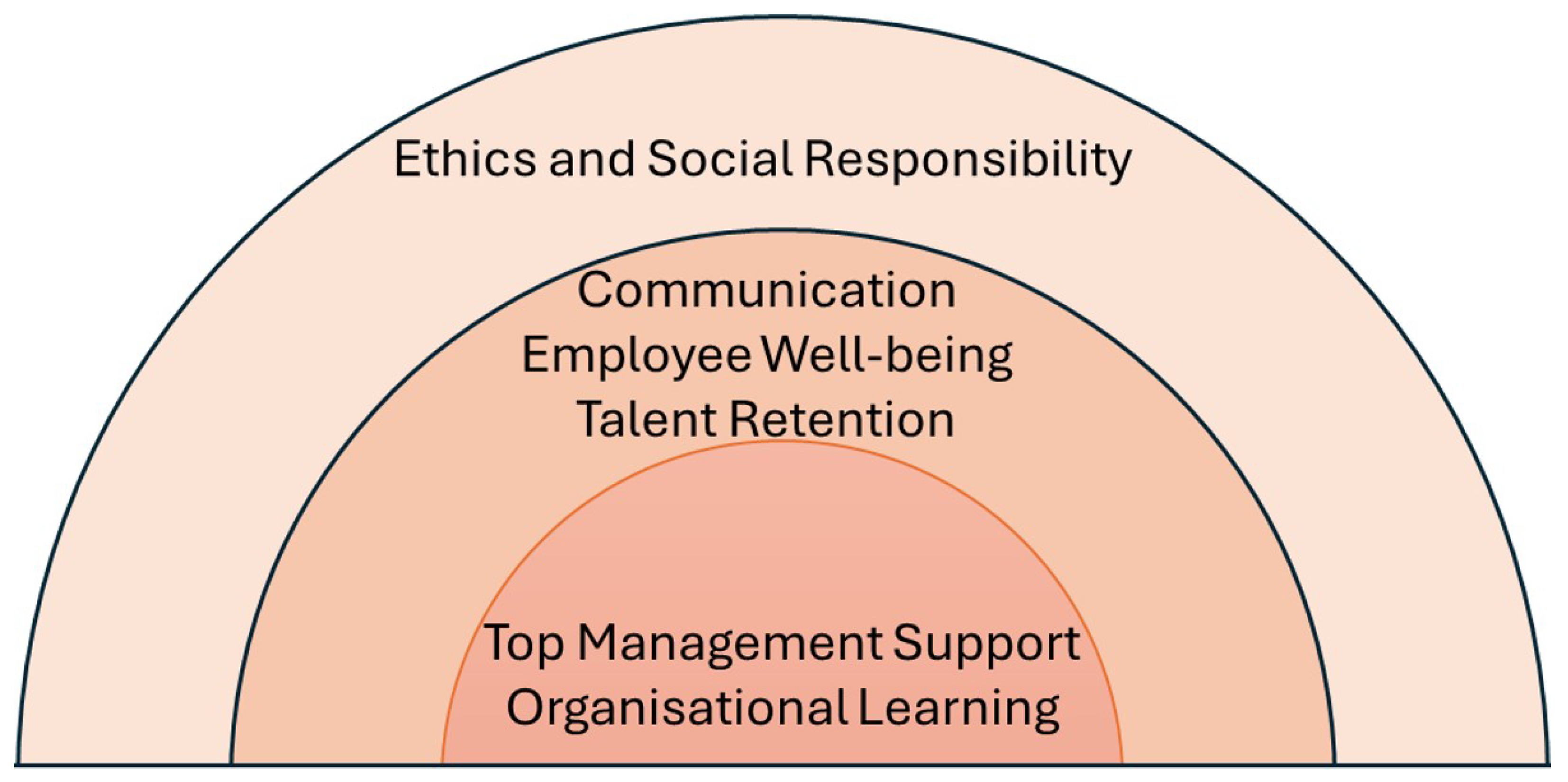

5. Results

5.1. Key Extracted Themes

5.1.1. Theme 1: Enhancing Communication and Collaboration

5.1.2. Theme 2: Employee Well-Being and Performance Optimisation

5.1.3. Theme 3: Talent Acquisition and Retention

5.1.4. Theme 4: Ethical and Social Responsibility

5.1.5. Theme 5: Top Management Support and Employee Empowerment

5.1.6. Theme 6: Organisational Learning and Development

5.1.7. Theme 7: Compliance with Industry Standards and Internal Improvement

5.2. Conceptual Modelling

- Enhancing Communication and Collaboration is foundational, influencing both Employee Well-being and Top Management Support.

- Employee Well-being directly supports Talent Acquisition and Retention, which in turn feeds into Organisational Learning and Development.

- Ethical and Social Responsibility underpins Compliance, ensuring integrity and alignment with standards.

- Top Management Support and Organisational Learning are central nodes, acting as bridges across multiple themes.

6. Discussion

6.1. Theoretical Positioning

6.2. Novelty and Contribution to Knowledge

6.3. Theoretical and Practical Implications of CI Cultural Dynamics

6.4. Repositioning the Assessment Tool and Researcher Reflexivity

6.5. Generalisability and Trustworthiness

6.6. Limitations

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CI | Continuous Improvement |

| GCC | Gulf Cooperation Council |

| SME | Small and Medium Enterprises |

References

- Albliwi, S. A., Antony, J., Arshed, N., & Ghadge, A. (2017). Implementation of Lean Six Sigma in Saudi Arabian organisations: Findings from a survey. International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management, 34(4), 508–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Halal, T. (2017, November 13–16). Blue print of local talent acquisition, development and retention. Abu Dhabi International Petroleum Exhibition & Conference, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A. J., Al-Aali, A., & Al-Owaihan, A. (2013). Islamic perspectives on profit maximization. Journal of Business Ethics, 117, 467–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljuaid, A. A., Masood, S. A., & Tipu, J. A. (2024). Integrating Industry 4.0 for sustainable localized manufacturing to support Saudi Vision 2030: An assessment of the Saudi Arabian automotive industry model. Sustainability, 16(12), 5096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhoraif, A., & McLaughlin, P. (2018). Lean implementation within manufacturing SMEs in Saudi Arabia: Organizational culture aspects. Journal of King Saud University-Engineering Sciences, 30(3), 232–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alotaibi, H. S., & Campbell, N. (2022). Organizational culture towards Saudi Arabia’s vision 2030: Evidence from national water company. Businesses, 2(4), 562–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alotaibi, M. S., McLaughlin, P., & Al-Ashaab, A. (2019). Organizational cultural factors influencing continuous improvement in Saudi universities. Journal of Organizational Management Studies, 2019, 408194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwagfi, A. A., Aljawarneh, N. M., & Alomari, K. A. (2020). Work ethics and social responsibility: Actual and aspiration. Journal of Management Research, 12(1), 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastassiu, M., & Santos, G. (2020, December 1–4). Resistance to change in software process improvement-an investigation of causes, effects and conducts. The XIX Brazilian Symposium on Software Quality (pp. 1–11), São Luís, Brazil. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariawaty, R. R. N. (2020). Improve employee performance through organizational culture and employee commitments. Jurnal Aplikasi Manajemen, 18(2), 318–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessant, J., Caffyn, S., & Gallagher, M. (2001). An evolutionary model of continuous improvement behaviour. Technovation, 21(2), 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessant, J., Caffyn, S., Gilbert, J., Harding, R., & Webb, S. (1994). Rediscovering continuous improvement. Technovation, 14(1), 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuiyan, N., & Baghel, A. (2005). An overview of continuous improvement: From the past to the present. Management Decision, 43(5), 761–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikshapathi, V. (2020). Total quality management for corporate social responsibility in small & medium enterprises. International Journal of Environmental Economics, Commerce and Educational Management, 7(5), 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruscaglioni, L. (2016). Theorizing in grounded theory and creative abduction. Quality & Quantity, 50(5), 2009–2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bubshait, F. A. (2022). Factors influencing the intention of saudi gen-y talent to stay in the saudi mining industry. University of Portsmouth. [Google Scholar]

- Chanani, U. L., & Wibowo, U. B. (2019). A learning culture and continuous learning for a learning organization. KnE Social Sciences, 591–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. SAGE Publications. Available online: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=v1qP1KbXz1AC (accessed on 23 June 2023).

- Chauhan, C., Kaur, P., Arrawatia, R., Ractham, P., & Dhir, A. (2022). Supply chain collaboration and sustainable development goals (SDGs). Teamwork makes achieving SDGs dream work. Journal of Business Research, 147, 290–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coghlan, D. (2021). Edgar Schein on change: Insights into the creation of a model. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 57(1), 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbin, J. M., & Strauss, A. (1990). Grounded theory research: Procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. Qualitative Sociology, 13(1), 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dettori, J. R., & Norvell, D. C. (2020). Kappa and beyond: Is there agreement? Global Spine Journal, 10(4), 499–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elabd, A. A. (2022). Developing and maintaining organizational culture for nuclear sites. In Fundamental issues critical to the success of nuclear projects (pp. 345–362). Elsevier. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faisal, S., & Naushad, M. (2020). An overview of green HRM practices among SMEs in Saudi Arabia. Entrepreneurship and Sustainability Issues, 8(2), 1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finfgeld, D. L. (1999). Courage as a process of pushing beyond the struggle. Qualitative Health Research, 9(6), 803–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, C. J., Schallert, D. L., Williams, K. M., Williamson, Z. H., Warner, J. R., Lin, S., & Kim, Y. W. (2018). When feedback signals failure but offers hope for improvement: A process model of constructive criticism. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 30, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Alcaraz, J. L., Oropesa-Vento, M., & Maldonado-Macías, A. A. (2017). Literature review. In Kaizen planning, implementing and controlling (pp. 23–31). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glawe, L., & Wagner, H. (2020). The middle-income trap 2.0: The increasing role of human capital in the age of automation and implications for developing Asia. Asian Economic Papers, 19(3), 40–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorzelany, J., Gorzelany-Dziadkowiec, M., Luty, L., Firlej, K., Gaisch, M., Dudziak, O., & Scott, C. (2021). Finding links between organisation’s culture and innovation. The impact of organisational culture on university innovativeness. PLoS ONE, 16(10), e0257962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Górny, A. (2018). Safety in ensuring the quality of production-the role and tasks of standards requirements. In Matec web of conferences (Vol. 183, p. 01005). EDP Sciences. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhalgh, T., Thorne, S., & Malterud, K. (2018). Time to challenge the spurious hierarchy of systematic over narrative reviews? European Journal of Clinical Investigation, 48(6), e12931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guba, E. G., & Lincoln, Y. S. (1994). Competing paradigms in qualitative research (Vol. 2, pp. 163–194). Sage Publications, Inc. Available online: https://miguelangelmartinez.net/IMG/pdf/1994_Guba_Lincoln_Paradigms_Quali_Research_chapter.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Guest, G., Bunce, A., & Johnson, L. (2006). How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods, 18(1), 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwet, K. (2001). Handbook of inter-rater reliability. STATAXIS Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Gwet, K. (2008). Computing inter-rater reliability and its variance in the presence of high agreement. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology, 61(1), 29–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habbash, M. (2015). Corporate governance, ownership, company structure and environmental disclosure: Evidence from Saudi Arabia. Journal of Governance and Regulation, 4(4), 460–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagaman, A. K., & Wutich, A. (2017). How many interviews are enough to identify metathemes in multisited and cross-cultural research? Another perspective on Guest, Bunce, and Johnson’s (2006) landmark study. Field Methods, 29(1), 23–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardcopf, R., Liu, G. J., & Shah, R. (2021). Lean production and operational performance: The influence of organizational culture. International Journal of Production Economics, 235, 108060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartnell, C. A., Ou, A. Y., & Kinicki, A. (2011). Organizational culture and organizational effectiveness: A meta-analytic investigation of the competing values framework’s theoretical suppositions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(4), 677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasnat, R., & Philbin, S. P. (2021). Understanding the communication and collaboration challenges encountered by technology managers. International Journal of Knowledge Management Studies, 12(1), 80–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henao-Hernández, I., Solano-Charris, E. L., Muñoz-Villamizar, A., Santos, J., & Henríquez-Machado, R. (2019). Control and monitoring for sustainable manufacturing in the Industry 4.0: A literature review. IFAC-PapersOnLine, 52(10), 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyden, M. L., Fourné, S. P., Koene, B. A., Werkman, R., & Ansari, S. (2017). Rethinking ‘top-down’and ‘bottom-up’roles of top and middle managers in organizational change: Implications for employee support. Journal of Management Studies, 54(7), 961–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirzel, A.-K., Leyer, M., & Moormann, J. (2017). The role of employee empowerment in the implementation of continuous improvement: Evidence from a case study of a financial services provider. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 37(10), 1563–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. (2011). Dimensionalizing cultures: The Hofstede model in context. Online Readings in Psychology and Culture, 2(1), 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollingworth, D., & Valentine, S. (2014). Corporate social responsibility, continuous process improvement orientation, organizational commitment and turnover intentions. International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management, 31(6), 629–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, A., Murphy, K., Grealish, A., Casey, D., & Keady, J. (2011). Navigating the grounded theory terrain. Part 2. Nurse Researcher, 19(1), 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyland, P. W., Mellor, R., & Sloan, T. (2007). Performance measurement and continuous improvement: Are they linked to manufacturing strategy? International Journal of Technology Management, 37(3–4), 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, L. R., Demaree, R. G., & Wolf, G. (1984). Estimating within-group interrater reliability with and without response bias. Journal of Applied Psychology, 69(1), 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimoh, R., Oyewobi, L., Isa, R., & Waziri, I. (2019). Total quality management practices and organizational performance: The mediating roles of strategies for continuous improvement. International Journal of Construction Management, 19(2), 162–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karolak, M., & Allam, N. (2020). Gulf cooperation council culture and identities in the new millennium: Resilience, transformation, (re)creation and diffusion. Springer Nature. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S. A., Kaviani, M. A., J. Galli, B., & Ishtiaq, P. (2019). Application of continuous improvement techniques to improve organization performance: A case study. International Journal of Lean Six Sigma, 10(2), 542–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knol, W. H., Lauche, K., Schouteten, R., & Slomp, J. (2019). The duality of lean: Organizational learning for sustained development. In Academy of management proceedings (Vol. 2019, p. 10594). Academy of Management. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotter, J. (1996). Leading. Harvard Business School Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lau, K. W., Lee, P. Y., & Chung, Y. Y. (2019). A collective organizational learning model for organizational development. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 40(1), 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maware, C., Okwu, M. O., & Adetunji, O. (2022). A systematic literature review of lean manufacturing implementation in manufacturing-based sectors of the developing and developed countries. International Journal of Lean Six Sigma, 13(3), 521–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mays, N., & Pope, C. (1995). Qualitative research: Observational methods in health care settings. BMJ, 311(6998), 182–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mburu, L. N. (2020). Examining how employee characteristics, workplace conditions and management practices all combine to support creativity, efficiency and effectiveness. International Journal of Business Management, Entrepreneurship and Innovation, 2(1), 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, N., Schoenebeck, S., & Forte, A. (2019). Reliability and inter-rater reliability in qualitative research: Norms and guidelines for CSCW and HCI practice. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 3(CSCW), 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHugh, M. L. (2012). Interrater reliability: The kappa statistic. Biochemia Medica, 22(3), 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S., & Dey, A. K. (2022). Understanding and identifying ‘themes’ in qualitative case study research (No. 3). Sage Publications Sage India. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munshi, J. (2014). A method for constructing likert scales. SSRN. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narmadha, M. P., & Vanithamani, D. M. R. (2018). A study on future talent acquisition with reference to e-recruitment practices followed in it and ITeS companies. International Journal of Trend in Scientific Research and Development, 2(4), 1721–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolic, D., Castronovo, F., & Leicht, R. (2021). Teaching BIM as a collaborative information management process through a continuous improvement assessment lens: A case study. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management, 28(8), 2248–2269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, D. M. d. C., Sousa, P. S., & Moreira, M. R. (2018). The relationship between leadership style and the success of Lean management implementation. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 39(6), 807–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohiwerei, F. O., & Onimawo, J. (2016). Effects of strike on the academic performance of business education students in Nigerian universities. International Journal of Academic Research in Progressive Education and Development, 5(3), 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ollila, S., & Yström, A. (2020). Action research for innovation management: Three benefits, three challenges, and three spaces. R&d Management, 50(3), 396–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paarlberg, L. E., & Perry, J. L. (2007). Values management: Aligning employee values and organization goals. The American Review of Public Administration, 37(4), 387–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panuwatwanich, K., & Nguyen, T. T. (2017). Influence of organisational culture on total quality management implementation and firm performance: Evidence from the Vietnamese construction industry. Management and Production Engineering Review, 8, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitoyo, D., Yuniarsih, T., Ahman, E., & Suparno, S. (2019). Model of employee empowerment and organizational performance at National Strategic Manufacturing Companies in West Java. In 1st international conference on economics, business, entrepreneurship, and finance (ICEBEF 2018) (pp. 201–205). Atlantis Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, R. K., & Hati, L. (2022). The measurement of employee well-being: Development and validation of a scale. Global Business Review, 23(2), 385–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, M., & Oppenheim, R. (2019). Ishikawa diagrams and Bayesian belief networks for continuous improvement applications. The TQM Journal, 31(3), 294–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sackmann, S. A. (1991). Uncovering culture in organizations. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 27(3), 295–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Ruiz, L., Gomez-Lopez, R., & Blanco Rojo, B. (2022). Key facilitators to continuous improvement: A Spanish insight. Business Process Management Journal, 28(4), 1071–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sande, B. (2019). Collaborative continuous improvement practices. International Journal for Talent Development and Creativity, 7, 79–90. [Google Scholar]

- Sarbah, A., & Xiao, W. (2013). Corporate governance practices in Ghanaian family businesses: A conceptual framework. International Journal of Advancements in Research & Technology, 3, 100–115. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, M., & Lewis, P. (2014). Doing research in business and management: An essential guide to planning your project. Pearson Education Limited. Available online: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=cg2pBwAAQBAJ (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Schreiber, J., & Melonçon, L. (2019). Creating a continuous improvement model for sustaining programs in technical and professional communication. Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, 49(3), 252–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidman, I. (2006). Interviewing as qualitative research: A guide for researchers in education and the social sciences. Teachers College Press. Available online: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=pk1Rmq-Y15QC (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Singh, J., & Singh, H. (2015). Continuous improvement philosophy–literature review and directions. Benchmarking: An International Journal, 22(1), 75–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starks, H., & Brown Trinidad, S. (2007). Choose your method: A comparison of phenomenology, discourse analysis, and grounded theory. Qualitative Health Research, 17(10), 1372–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stativă, G.-A., & Todoran, T. A. (2022). Learning practices as a continuum. In Proceedings of the international conference on business excellence (Vol. 16, pp. 943–952). Sciendo. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamayo-Torres, J., Gutierrez-Gutierrez, L., & Ruiz-Moreno, A. (2014). The relationship between exploration and exploitation strategies, manufacturing flexibility and organizational learning: An empirical comparison between Non-ISO and ISO certified firms. European Journal of Operational Research, 232(1), 72–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavana, M., Shaabani, A., & Valaei, N. (2021). An integrated fuzzy framework for analyzing barriers to the implementation of continuous improvement in manufacturing. International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management, 38(1), 116–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teherani, A., Martimianakis, T., Stenfors-Hayes, T., Wadhwa, A., & Varpio, L. (2015). Choosing a qualitative research approach. Journal of Graduate Medical Education, 7(4), 669–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terra, J. D. R., Berssaneti, F. T., & Quintanilha, J. A. (2021). Challenges and barriers to connecting World Class Manufacturing and continuous improvement processes to Industry 4.0 paradigms. Engineering Management in Production and Services, 13(4), 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thürer, M., Tomašević, I., & Stevenson, M. (2017). On the meaning of ‘waste’: Review and definition. Production Planning & Control, 28(3), 244–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tie, Y. C., Birks, M., & Francis, K. (2019). Grounded theory research: A design framework for novice researchers. SAGE Open Medicine, 7, 2050312118822927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaismoradi, M., Jones, J., Turunen, H., & Snelgrove, S. (2016). Theme development in qualitative content analysis and thematic analysis. Journal of Nursing Education and Practice, 6(5), 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinodh, S., Antony, J., Agrawal, R., & Douglas, J. A. (2021). Integration of continuous improvement strategies with Industry 4.0: A systematic review and agenda for further research. The TQM Journal, 33(2), 441–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahyuningsih, S. H., Sudiro, A., Troena, E. A., & Irawanto, D. (2019). Analysis of organizational culture with Denison’s model approach for international business competitiveness. Problems and Perspectives in Management, 17(1), 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, M. (1978). Economy and society: An outline of interpretive sociology (Vol. 1). University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Weick, K. E., & Weick, K. E. (1995). Sensemaking in organizations (Vol. 3). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Wieneke, K. C., Egginton, J. S., Jenkins, S. M., Kruse, G. C., Lopez-Jimenez, F., Mungo, M. M., Riley, B. A., & Limburg, P. J. (2019). Well-being champion impact on employee engagement, staff satisfaction, and employee well-being. Mayo Clinic Proceedings: Innovations, Quality & Outcomes, 3(2), 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. (2025). Manufacturing, value added (% of gdp)—Saudi Arabia. World Bank Data. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NV.IND.MANF.ZS?locations=SA (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Zhang, D., Linderman, K., & Schroeder, R. G. (2012). The moderating role of contextual factors on quality management practices. Journal of Operations Management, 30(1–2), 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Company Name | Numbers of Employees | Organisation Size | Turnover Million ($) |

|---|---|---|---|

| The National Agricultural Development Co. Nadec | 4175 employees | Large | 95.5 m |

| National Food Company | 1000 employees | Large | 92.2 m |

| Saudi Modern Foods Factory | 111 employees | SME | 4 m |

| Al-Taif National Dairy Factory | 100–200 employees | SME | 25 m |

| National Food Industries Company (Luna) | 1000–5000 employees | Large | 521 m |

| Position | No | Interviewees Experience | Interviewees Education |

|---|---|---|---|

| Senior Director of Operations | 5 | 10–15 years | Higher education (Master’s degree) |

| Team Leaders | 4 | 8–10 years | Bachelor |

| Quality Control Managers | 3 | 5–10 years | Bachelor |

| Process Supervisors | 11 | 3–8 years | Bachelor |

| Production Supervisors | 5 | 4–6 years | Bachelor |

| # | Aspects | Rater 1 | Rater 2 | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Enhancing communication for employee collaboration | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 2 | Cooperation towards formulation of new ideas | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 3 | Problem identification | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 4 | Fostering positive social relationships within the organisation | 0 | 1 | −1 |

| 5 | Facilitating collaborative team research | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 6 | Prioritising employee well-being | 0 | 1 | −1 |

| 7 | Maximising employees’ efficiency | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 8 | Cultivating employee motivation for continuous improvement | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 9 | Employees’ resistance to change | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 10 | Establishing effective training programs for trainees | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 11 | Embracing flexibility in work conditions to foster improvement | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 12 | The risk of expertise loss within the organisation | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 13 | Shortage of workforce | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 14 | Implementing regular evaluation of organisational activities | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 15 | Strengthening employee relations | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 16 | Embracing employee diversity for improvement | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 17 | Promoting employee engagement in CI initiatives | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 18 | Creating a supportive work environment | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 19 | Addressing customer complaints as improvement opportunities | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 20 | Implementing supplier engagement policies for collaborative improvement efforts | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 21 | Establishing effective employee monitoring mechanisms | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 22 | Lack of moral incentives | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 23 | Ensuring fair employee salary structures | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 24 | Promoting ethical behaviour | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 25 | Top management support for improvement initiatives | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 26 | Encouraging employee independence in improvement processes | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 27 | Ensuring high-quality standards in organisational processes | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 28 | Incorporating staff opinions in decision making | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 29 | Implementing effective employee performance management strategies | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 30 | Establishing clear goal setting for improvement | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 31 | Cultivating a healthy work environment to enhance CI efforts | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 32 | Supporting risk-taking for innovation | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 33 | Implementing a comprehensive system for tracking work progress from initiation to completion | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 34 | Conducting regular staff meetings to facilitate communication | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 35 | Promoting effective planning strategies to support continuous improvement | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 36 | Poor supplier relationships | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 37 | Internal violation committee | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 38 | Promoting continuous learning | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 39 | Empowering employees to implement improvement initiatives | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 40 | Emphasising data-driven decision-making for continuous improvement | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Number of zeros | 37 | |||

| Number of aspects | 40 | |||

| Percentage agreement | 92.5% |

| Rater 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Correct | Incorrect | ||

| Rater 1 | |||

| Correct | A = 37 | B = 1 | |

| Incorrect | C = 1 | D = 1 |

| Level of Agreement | Number |

|---|---|

| Number of aspects approved by both raters | 37 |

| Number of aspects excluded by both raters | 1 |

| Number of aspects approved by only the first rater | 1 |

| Number of aspects approved by only the second rater | 1 |

| Cohen’s kappa results | % of agreement: 92.5% Cohen’s K: 0.9254447 almost perfect agreement |

| Focus Group | Number of Participants | Job Titles | Years of Experience | Length of Time (h) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Session 1 | 6 | Senior Director of Operations | 12 | 4 |

| Quality Control Manager | 10 | |||

| Process Supervisor | 8 | |||

| Process Supervisor | 6 | |||

| Production Supervisor | 6 | |||

| Production Supervisor | 4 | |||

| Session 2 | 6 | 5 |

| Theme | Codes Incorporated within the Theme |

|---|---|

| Enhancing Communication and Collaboration |

|

| Employee Well-being and Performance Optimisation |

|

| Ethical and Social Responsibility |

|

| Talent Acquisition and Retention |

|

| Top Management Support and Employee Empowerment |

|

| Organisational Learning and Development |

|

| Compliance with industry standards and internal improvement |

|

| Theme | Description |

|---|---|

| Enhancing Communication and Collaboration | This theme encompasses strategies and practices aimed at improving the exchange of information, fostering teamwork, and building positive relationships among employees within the organisation to facilitate continuous improvement efforts. |

| Employee Well-being and Performance Optimisation | This theme focuses on creating a supportive and healthy work environment, boosting employee motivation, and implementing flexible work conditions to maximise individual and collective efficiency and drive continuous improvement initiatives. |

| Ethical and Social Responsibility | This theme highlights the importance of promoting ethical conduct, addressing customer concerns, engaging with suppliers responsibly, ensuring high-quality standards, setting clear goals, providing moral incentives, and valuing employee diversity in the pursuit of organisational improvement. |

| Talent Acquisition and Retention | This theme addresses the challenges related to potential loss of expertise, workforce shortages, and the necessity of establishing fair salary structures to attract and retain skilled employees crucial for sustained improvement. |

| Top Management Support and Employee Empowerment | This theme underscores the critical role of leadership in empowering employees to take ownership of improvement initiatives, encouraging their autonomy, implementing effective monitoring and performance management, valuing their input in decision-making, and providing overall support for continuous improvement endeavours. |

| Organisational Learning and Development | This theme focuses on establishing mechanisms for regular communication, tracking work progress effectively, conducting periodic evaluations, promoting a culture of continuous learning, implementing sound planning strategies, and encouraging risk-taking to foster innovation and improvement. |

| Compliance with industry standards and internal improvement | This theme emphasises the significance of creating a supportive work environment, basing decisions on data, addressing internal violations, fostering positive supplier relationships, and actively involving employees in organisational improvement initiatives to meet external requirements and enhance internal processes. |

| Themes | Supportive Literature |

|---|---|

| Enhancing Communication and Collaboration | Hasnat and Philbin (2021); Nikolic et al. (2021); Sande (2019); Schreiber and Melonçon (2019); Tavana et al. (2021); Terra et al. (2021) |

| Employee Well-being and Performance Optimisation | Ariawaty (2020); Khan et al. (2019); Pradhan and Hati (2022); Wieneke et al. (2019) |

| Talent Acquisition and Retention | Al-Halal (2017); Bubshait (2022); Fong et al. (2018); Narmadha and Vanithamani (2018) |

| Ethical and Social Responsibility | Ali et al. (2013); Alwagfi et al. (2020); Bikshapathi (2020); Habbash (2015); Hollingworth and Valentine (2014) |

| Top Management Support and Employee Empowerment | Alwagfi et al. (2020); Heyden et al. (2017); Hirzel et al. (2017); Pitoyo et al. (2019) |

| Organisational Learning and Development | Knol et al. (2019); Lau et al. (2019); Stativă and Todoran (2022); Tamayo-Torres et al. (2014) |

| Compliance with industry standards and internal improvement | Górny (2018); Henao-Hernández et al. (2019); Khan et al. (2019); Mburu (2020) |

| Theme | Average Score |

|---|---|

| Enhancing communication and collaboration | 6.4 |

| Employee well-being and performance optimisation | 6.0 |

| Organisational learning and development | 6.0 |

| Talent acquisition and retention | 5.9 |

| Ethical and social responsibility | 5.7 |

| Compliance with industry standards and internal improvement | 5.3 |

| Top management support and employee empowerment | 4.9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Algethami, A.; Assad, F.; Patsavellas, J.; Salonitis, K. Developing a Supportive Organisational Culture for Continuous Improvement in Manufacturing Firms in Saudi Arabia. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 241. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15070241

Algethami A, Assad F, Patsavellas J, Salonitis K. Developing a Supportive Organisational Culture for Continuous Improvement in Manufacturing Firms in Saudi Arabia. Administrative Sciences. 2025; 15(7):241. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15070241

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlgethami, Adel, Fadi Assad, John Patsavellas, and Konstantinos Salonitis. 2025. "Developing a Supportive Organisational Culture for Continuous Improvement in Manufacturing Firms in Saudi Arabia" Administrative Sciences 15, no. 7: 241. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15070241

APA StyleAlgethami, A., Assad, F., Patsavellas, J., & Salonitis, K. (2025). Developing a Supportive Organisational Culture for Continuous Improvement in Manufacturing Firms in Saudi Arabia. Administrative Sciences, 15(7), 241. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15070241