Abstract

The increasing integration of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) practices into corporate strategy has raised important questions about their financial implications. This study examines the relationship between ESG performance and financial outcomes in the tourism industry, an industry that is both highly visible and environmentally sensitive. To achieve this, this study analyzes the impact of the three ESG dimensions on financial performance, measured by Return on Assets (ROA). Using panel data econometric techniques, this study examines a balanced panel dataset of 154 listed tourism services firms between 2017 and 2021 to assess how each ESG pillar influences profitability. ESG data were sourced from Refinitiv Eikon, a widely validated provider in ESG-financial research. The analysis employs panel data econometric techniques with firm size and leverage as control variables. Our findings indicate that the Environmental, Social, and Governance scores each have a statistically significant negative effect on ROA, while the ESG controversies score is not statistically significant. These results suggest that despite the reputational value of ESG engagement, its short-term financial impact may be limited or negative in capital-intensive service sectors, such as tourism. This study contributes to the literature by providing sector-specific, post-crisis empirical evidence and highlights the need for a nuanced understanding of ESG–financial dynamics across industries.

1. Introduction

With the rising awareness of the climate crisis as well as concerns about income inequality and geopolitical issues, sustainability has become a corporate emerging imperative in various industries (Zhou et al., 2023; Skordoulis et al., 2020; Skordoulis et al., 2022).

Prior to this study, researchers have addressed the link between corporate financial performance and ESG scores. From a risk perspective, ESG practices increase firms’ value by mitigating the potential risks of inadequate governance (Oikonomou et al., 2012). In accordance with Dhaliwal et al. (2011) from an information perspective, firms attract more investors due the transparency and abundance of publicly available information on their ESG initiatives. From a strategic point of view, firms implement responsible ESG practices to gain the trust of stakeholders. By acquiring tangible and intangible resources through these practices, they gain competitive advantage and increase their profitability (Taliento et al., 2019).

Sustainability policies and initiatives have progressed significantly due to the intensifying impacts from climate change and the growing recognition from stakeholders about the importance of effectively addressing these risks and impacts. Sustainable business and reporting practices are some of the key elements that drive, along with the Sustainable Development Goals and the Paris Agreement, countries to include them around the world. Following these new transition pathways, the goal of business perspectives shifted from focusing on only generating shareholder value to creating long-term stakeholder value and sustained growth that takes into consideration the Environmental, Social, and Governance performance of firms. All the above conclude with the construction of a certain structured framework for evaluating performance criteria called ESG.

The global tourism industry, accounting for 7.6% of global GDP in 2022, has rebounded significantly post-COVID-19, underscoring both its resilience and global economic significance (World Travel & Tourism Council (WTTC), 2022). Tourism firms were supposed to flourish, but in 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak had a negative impact on the whole industry. In 2020, there was a 62% decline in the global travel and tourism market value, with cascading effects on affiliated industries. The development of the tourism industry varied in the years under investigation, and global demand for travel and tourism increased by 43% in 2021 because of the industry’s recovery from the restrictions imposed during the COVID-19 pandemic and the sharp increase in travel products offered by online travel intermediaries as customers booked their trips after nearly two years of restrictions.

The tourism industry’s reliance on environmental assets (e.g., natural landscapes, biodiversity), human resources (e.g., hospitality workers), and global mobility makes it particularly vulnerable to ESG risks, including climate change, carbon emissions, labor practices, and governance failures (Drosos & Skordoulis, 2018; Khan et al., 2023; Hassan & Meyer, 2022; Zhao et al., 2023; Voumik et al., 2024). These issues not only affect local communities but also global perceptions of tourism brands. Governance practices, such as transparency and ethical management, are especially critical in this highly interconnected and customer-facing industry (Bae, 2022).

Given these dynamics, understanding how sustainability strategies, such as ESG, contribute to financial outcomes in tourism has become increasingly important. The integration of ESG criteria into corporate strategy has garnered significant attention from investors, regulators, and academics. A comprehensive meta-analysis by Friede et al. (2015) reviewed over 2000 empirical studies and found that approximately 90% reported a non-negative relationship between ESG performance and corporate financial performance, with the majority indicating positive correlations. Despite this, the tourism industry remains underrepresented in the ESG-related financial performance research. Font et al. (2016) highlighted that small tourism enterprises often engage in sustainability practices driven by ethical considerations rather than economic gains. Furthermore, ESG measurement in the tourism industry is still developing, particularly lacking perspectives from developing countries. Moreover, empirical studies suggest ESG policies improve innovation, value creation, and access to capital, supporting long-term financial performance (H. Ahmad et al., 2023; Zahid et al., 2023; Cheng et al., 2014). However, recent research on ESG has focused on the direct link between ESG and firm performance, specifically in different industries, emerging, or developed nations (Junius et al., 2020; Makhdalena et al., 2023; Alareeni & Hamdan, 2020; Velte, 2017).

This study aims to fill this gap by empirically analyzing the relationship between ESG scores and financial performance, measured by Return on Assets (ROA), in listed tourism industry firms from 2017 to 2021. Employing a panel data methodology, this research examines how Environmental, Social, Governance, and controversies scores influence financial outcomes, while controlling firm size and leverage ratio. To achieve this aim, this study sets out the following specific research objectives:

- Estimation of the impact of the environmental dimension on financial performance.

- Evaluation of the effect of the social dimension on financial performance.

- Investigation of the relationship between the governance dimension and financial performance.

To address the aim and the objectives outlined above, we employed panel data techniques. Specifically, we analyzed the relationship between the three pillars of ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance scores) and the financial performance of listed tourism services firms, measured by Return on Assets (ROA).

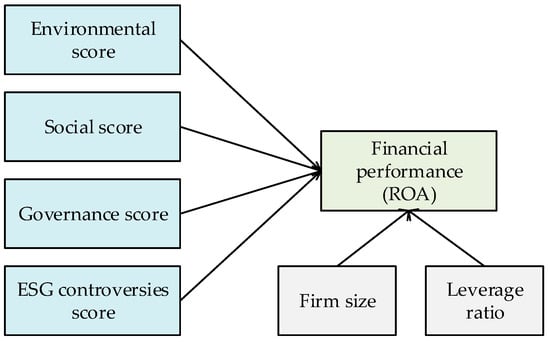

Figure 1 presents the conceptual framework for this study. The model hypothesizes that the Environmental, Social, Governance, and ESG controversies scores affect financial performance, measured by Return on Assets (ROA). Firm size and leverage ratio are included as control variables to account for structural differences across firms that may influence financial outcomes independently of ESG performance.

Figure 1.

Conceptual research framework.

2. Literature Review

2.1. ESG Reporting and Sustainability Policy Frameworks

The Sustainable Development Agenda, its 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), and 169 sub-goals, were adopted at the 70th United Nations General Assembly on 25 September 2015 (United Nations, 2015).

The Non-Financial Reporting Directive, known as the NFRD, was adopted in 2014 by the European Union, requiring large public entities (listed, credit institutions and insurance firms) with more than 500 employees to publish a non-financial report on their ESG performance. Firms in scope, according to the Directive 2014/95/EU (European Union, 2014), were encouraged to develop a responsible approach regarding the three sub-indicators of ESG sustainability reports referred to as Environmental, Social, and Governance. The NFRD implementation requires non-financial information on environmental matters, social and employee issues, anti-bribery and anti-corruption issues, diversity, and respect for human rights. Firms outline their risks accordingly with the previous issues and all the resulting policies to mitigate these risks and address the corporate social responsibility. The impact of the implementation of non-financial information on the comparability of listed European firms was the aim of the research of Breijer and Orij (2022). The results revealed that the introduction of the directive resulted in a rise in the use of investor-oriented NFR frameworks (e.g., the SASB); meanwhile, frameworks aimed at a broad range of stakeholders (e.g., GRI) were mostly employed by voluntary adopters.

According to the Directive, the reports were to include details about the firm’s commitments and accomplishments on a range of Environmental, Social, and Governance-related issues that are relevant to—or rather, “material”—to each firm’s operations. In what is commonly referred to as the “double-materiality” principle of non-financial reporting, firms are required by the NFRD to disclose how sustainability issues affect both their performance and development (the “outside–in” perspective) and their impact on people and the environment (the “inside–out” perspective). This “double-materiality concept” encompasses both perspectives: one of which focuses on how external ESG factors affect the firm and the other on how the firm impacts external ESG factors (Baumüller & Sopp, 2022).

The NFRD has also, for the first time, established a standard for how reports must be written in accordance with the frameworks (such as the Global Reporting Initiative (2017) [GRI] Standards). This is performed to establish a thorough and comprehensive reporting process as well as to make the reports comparable and measurable based on this type of qualitative data (Cicchiello et al., 2023). However, the NFRD primarily operates on a “comply or explain” basis, allowing firms to decide whether to implement the rules and conduct the necessary due diligence required by the regulations (Dolmans et al., 2021). According to the European Commission, the reported information based on NFRD was insufficient. In particular, important information for investors and stakeholders was often omitted, and the information provided was difficult to compare due to the different approaches and standards used. This “accountability gap” was also cited by the European Commission as the reason for proposing the CSRD (European Union, 2022). The goal of the new disclosure was created mainly to determine and provide data to investors regarding a firm’s sustainability.

The CSRD came into force on 5 January 2023. The new directive has been applied since 2024 by a larger range of firms for reports published in 2025. The Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive will be mandatory for at least 50,000 EU-based firms as of 2024. Firms are required by law to report on Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) issues that are “material” to their industry and to their stakeholders following the European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS) framework and ten topical Environmental, Social, and Governance standards. SMEs that are not on the list, despite being an essential component of the European economy, will nevertheless be required to provide this non-financial information voluntarily. Non-financial information is frequently provided by European SMEs due to pressure from suppliers, clients, and providers. They also require it in order to apply for financial resources, or even because they follow the lead or imitate large firms to set themselves apart from their competitors (Ortiz-Martínez & Marín-Hernández, 2024). It follows that enhancing completeness, comparability, and dependability is the EU Commission’s primary objectives. Nevertheless, a lot of the newly proposed standards are excessively complicated and raise important problems about what constitutes an appropriate administrative cost for firms as well as the essential theoretical basis of a reporting framework (Baumüller & Grbenic, 2021).

2.2. Environmental Pillar and Financial Performance in Tourism

Tourism relies heavily on environmental quality, both natural and man-made. However, the link between tourism and the environment is complicated. It includes a variety of actions that may have a negative impact on the environment. Many of these effects are related to the building of general infrastructure, like roads and airports, as well as tourism amenities, like resorts, hotels, restaurants, shops, golf courses, and marinas. The negative effects of tourist development can eventually deplete the environmental resources on which it relies (Sunlu, 2003).

Ionescu et al. (2019) examined the influence of environmental score on market value of firms and the related findings were mixed. In more detail, in European countries, the highest and most positive effect of market capitalization due to environmental score was observed; in Asian firms there was a positive, but weak correlation, and finally American firms had a high negative effect. They concluded that investors appear to view the expenses of environmental programs as having no apparent value for the firms under analysis; therefore, it appears that financial consequences are more important than anything else. In line with the negative influence of environmental scores on the market value are the findings of Hassel et al. (2005), indicating that investors do not place a high value on firms with excellent environmental ratings. According to Moneva et al. (2020), considering that it has no effect on their profitability, tourism firms should adopt more sustainable, corporate, environmental performance strategies.

However, studies apart from those in the selected industry have found that improving environmental performance has a beneficial impact on financial performance. The empirical results of Carnini Pulino et al. (2022) emphasize that higher investment in sustainable environmental projects enhances a firm’s performance measured by EBIT. Similarly, Buallay’s (2019) results indicate that the environmental practices positively affect the ROA and TQ.

ESG scores increasingly serve as proxies for firms’ commitment to sustainable and environmentally responsible practices. In particular, the environmental component of ESG reflects operational decisions related to energy efficiency, emissions control, resource use, and innovation in green technologies (Cheng et al., 2014). High ESG ratings are often associated with structured sustainability initiatives, regulatory compliance, and voluntary environmental disclosures, which together signal the firm’s alignment with green strategic objectives. In this context, ESG metrics not only inform investors but also guide internal strategic priorities, making them a credible indicator of a firm’s broader environmental and sustainability stance.

Recent research underscores the complexity of the relationship between environmental performance and firm profitability, especially in industries directly exposed to environmental risks. In the tourism industry, where environmental quality is a core attribute, green certifications and environmental transparency have been linked to higher customer satisfaction and loyalty (Filimonau et al., 2022; Skordoulis et al., 2024b). For example, hotels with eco-labels often experience higher occupancy rates and revenue per available room, especially in environmentally conscious markets (Arbelo et al., 2025). Moreover, firms that proactively report their carbon reduction strategies are increasingly favored by institutional investors who assess climate risk exposure in asset pricing (Skordoulis et al., 2022). These benefits suggest that environmental efforts, when communicated effectively, may translate into long-term financial value, even if short-term costs are incurred. This perspective aligns with Porter and van der Linde’s (1995) hypothesis that environmental innovation can lead to competitive advantages. However, these benefits depend heavily on consumer awareness and regional regulatory environments, reinforcing the need for context-specific analysis within tourism.

2.3. Social Pillar and Financial Performance in Tourism

While the environmental aspect of ESG may be the most well-known, the social and governance pillars are less familiar. Social refers to an organization’s principles, policies, and practices on human rights, corporate ethics, diversity and inclusion, supply chain management, and the social effect of its activities. The underlying question behind social is how a corporation handles the essential connections with its personnel and the society in which it works. Though all aspects of ESG are interconnected, social pillar is critical for investors who want to avoid firms with bad human rights issues, transgressions, or dubious political connections. Therefore, organizations with a high social performance may increase their total ESG score and will allow investors to trust that goodwill is involved, risks will be avoided, and mutual values are prioritized.

Regarding the influence of the social factor on the market value of the firms from the travel and tourism industry, Ionescu et al. (2019) found a negative relationship for the entire world analyzed, but with varying levels of significance from one region to another. Accordingly, Moneva et al. (2020), identified the neutral impact of the tourism firms’ social performance on financial performance following with two exceptions: (i) a negative influence of firms’ social performance on firms’ Tobin’s Q in the hotel, motel, and cruise line industries; and (ii) a negative impact of firms’ social performance on firms’ ROA in restaurants. These findings are not consistent with the instrumental stakeholder theory, which predicts that financial gains will be generated by implementing social practices (e.g., connecting with local communities, promoting human rights, addressing diversity, and offering improved job quality).

Other lines of study have shown that social pillar can improve a firm’s performance and have claimed a positive impact. For example, Makhdalena et al. (2023), studied the effect of ESG information on firm performance in ASEAN developing countries. They concluded that carrying out social-related activities and disclosing them is proven to improve firm and market performance.

Within the tourism industry, social sustainability initiatives, such as fair labor practices, community engagement, and cultural preservation, have shown mixed but potentially valuable impacts on brand equity and financial results. For example, studies have found that tourism firms promoting local hiring and training programs often report improved employee retention and guest satisfaction (Baum et al., 2016; Skordoulis et al., 2024a). Moreover, social initiatives tied to community-based tourism can lead to positive media exposure and stakeholder support, which in turn enhance revenue and resilience (Oklevik et al., 2020). From an investor perspective, socially proactive firms may attract ESG-oriented capital, especially from millennial investors increasingly concerned with corporate values (Luu & Rubio, 2024; Skordoulis et al., 2025). However, the absence of industry-specific social indicators and the intangibility of “S” impacts complicate measurement and valuation (Yoon & Chung, 2018). This underscores the importance of industry-focused models that account for the diffuse yet reputationally significant effects of social practices in tourism.

2.4. Governance Pillar and Financial Performance in Tourism

Using best practices in corporate governance expands the organization’s primary strategic initiatives to better meet the needs of its stakeholders and ensures that the board oversees the firm effectively. Moneva et al. (2020) employed the instrumental stakeholder theory as well as the slack resources approach to examine the reciprocal relationships between the financial success of tourism-related firms and their CSR performance. The sample, covering enterprises in the tourism industry from 24 countries, was observed between 2004 and 2017. The results show a negative impact of the sub-dimension governance on ROA for the whole sample. Furthermore, the results reveal that corporate governance performance and financial performance in the hotel industry are independent of each other. However, a negative effect of casinos and gaming firms’ corporate governance performance on their Tobin’s q was found. This argument could stem from the idea that CSR is not consistent with the procedures of gaming and casinos. This is not in line with Ionescu et al. (2019), who found mixed effects of the governance factor depending on regions under investigation. A modified version of Ohlson’s (1995) model, based on 73 listed firms, worldwide, grouped by country of origin in three regions, Europe, the United States, and Asia, for a time period of six years, starting from 2010 to 2015, was the relevant research sample of Ionescu et al. (2019). The aim was to investigate the individual impact of the Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) factor and firm market value for the firms in the travel and tourism industry. According to Ionescu et al. (2019), of the ESG factors, the governance factor seems to have the most important influence on the market value of the selected firms, regardless of their geographic region. A positive influence of the governance score on the market value could be identified, in the case of US-based firms; on the other hand, the influence of the governance factor on market value proved to be negative for firms originating in Europe and Asia.

While governance is often framed as the most quantifiable ESG pillar, its link to financial performance in tourism remains complex. Strong governance structures, such as independent boards, anti-corruption policies, and clear stakeholder disclosure, are linked to reduced operational risk and improved capital access (Isnurhadi et al., 2020; Delegkos et al., 2022). In hospitality and travel firms, transparency and ethical oversight are particularly important in managing franchise operations, cross-border compliance, and crisis responses (Leopizzi et al., 2021). Recent studies also highlight the moderating role of governance in mitigating reputational damage from environmental or social controversies (Aouadi & Marsat, 2018). In this sense, governance can act as a strategic enabler that boosts investor confidence and reduces volatility. However, there is evidence that overly formalized governance systems may impede innovation or agility in service industries, potentially explaining mixed financial results (Stavropoulos & Zounta, 2025). Therefore, governance in tourism should be evaluated not just by compliance, but by its adaptability and alignment with firm-specific strategies.

2.5. Effect of ESG Controversies on Financial Performance

Despite the growing literature and research on the benefits that sustainability practices can bring to a firm’s performance, along with the value created for several stakeholders, and even if it seems logical for firms to implement related actions, they do not always comply with this framework. On the contrary, scandals and controversies place a firm’s reputation at risk, leading to a negative impact. According to Aouadi and Marsat (2018), ESG controversies can be defined as corporate ESG “news stories such as suspicious social behavior and product-harm scandals that place a firm under the media spotlight and, by extension, grab investors’ attention”.

According to (Li et al., 2019) when a firm engages in behaviors or events that have the potential to negatively affect its stakeholders and the environment, controversies arise. Corporate scandals can have enormous financial consequences and can involve anything from bribery and corruption to workplace discrimination and environmental catastrophes. These incidents also harm the reputation of the firms’ stockholders and the corporations themselves. The reputation of a firm is frequently put in danger by conflicts, which necessitate appropriate action on the part of the firm to alleviate their negative impacts. In such situations, firms are inclined to participate in CSR as a way to recover their damaged reputation (Becker-Olsen et al., 2006). Nirino et al. (2021) aimed to explore the impact of corporate controversies on financial performance. Linear regression models confirmed a negative and substantial association between corporate disputes and financial performance using a database of 356 European listed firms. However, the beneficial moderating effect of ESG policies on the association between scandals and financial performance could not be verified.

Dogru et al. (2022) analyzed 118 publicly owned travel firms divided into categories such as casino hotels, resorts, restaurants, and leisure enterprises included in the Russell 3000 index. The study examines the extent to which issues relevant to ESG affect tourism firms’ profits by applying a technique based on the reactions of the market to noteworthy events. Their findings revealed that, although certain incidents linked to ESG issues of corporations exhibited a negative impact on firm value, investors mostly disregarded this information. Further investigation revealed that the frequency of news about ESG problems resulted in negative effects on firms’ value, which have substantially increased since the COVID-19 outbreak. As a result of the COVID-19 epidemic, shareholders in tourist firms have been more alert to news about ESG concerns. This finding implies that, even though most problems can be dismissed in normal circumstances, ESG risk is given more weight by shareholders in the case of a pandemic.

Researchers are confronted with related theories, of which the following two are contradictory, in their attempt to determine whether a sustainable society is priced in financial markets and whether responsible practices have an impact on firm value. Firstly, according to the shareholder theory (Friedman, 1970), expenditures related to ESG practices allocate funds that can be used to improve enterprises’ primary economic activities and increase shareholder value. Freeman’s (1984) stakeholder theory, on the other hand, contends that meeting the environmental and social concerns of stakeholders is just as vital as achieving the income objectives of shareholders.

In this context, according to the stakeholder theory, unfavorable ESG-related news exposes enterprises to ESG risk and reduces corporate value (Dogru et al., 2022). Controversial ESG news promotes stakeholder suspicion about corporations’ existing ESG efforts and generates worries among stakeholders (Godfrey et al., 2009). Friedman (1970) argues based on the shareholder theory that ESG news with controversial impacts has no effect on firms’ value since it is inappropriate to link shareholders’ main purpose—maximizing their wealth—with ESG concerns.

2.6. Effect of Overall ESG Combined Score on Financial Performance

Aydoğmuş et al. (2022) examined the impact of ESG performance on firm value and profitability, selecting the largest 5000 publicly listed firms from 2013 to 2021. Their results indicate that the overall ESG combined score is positively and strongly linked with firm value. Although social and governance individual ESG scores have highly significant positive relationships with firm value, environment has no relationship with firm value. Extending the relationship between corporate financial performance, measured by ESG scores, Dorfleitner et al. (2020) analyze the ESG combined score of an average of 2500 firms between 2002 and 2018, by examining the five-factor risk-adjusted performance of positively screened best and worst portfolios. Their dataset includes all Thomson Reuters scores, controversies, and combined scores for the European, US, and global markets. The findings suggest a significant outperformance for equally weighted worst-ESG portfolios and best controversies strategies, whereas value-weighted strategies do not demonstrate substantial abnormal returns. Similarly, Kocherlakota et al. (2023) aimed to identify which factor of ESG influences financial performance during a pandemic by selecting data from BRICS nations. The results suggest that the ESG factors influence the financial performance and, more specifically, the combined ESG score positively influences the financial performance measured on the Return on Sales (ROS) in contradiction with the controversies score, which has a negative influence.

The listed travel and leisure firms were the research sample of Rodríguez-Fernández et al. (2019) contributing to the objective of developing ESGC indicators and researching their impact on financial performance. As verified in their analysis, the corporate financial performance measured through the ROA and ROE variables exhibited a direct and positive relationship with the governance indicator. However, no significant relationship was found between the ESGC indicator and the financial variable influenced by the market, measured using Tobin’s Q.

Despite the numerous studies that have been carried out on the relationship between ESG indicators and the financial performance of firms, the research approach in the field of tourism and, in particular, of globally listed firms of hotel industry and entertainment services with the available ESG combined score, retrieved from Refinitiv Eikon, is not thoroughly developed.

Following the above research topics, concerning the association of ESG components with financial performance, this research extends the research field by acknowledging the role of controversies in influencing the outcome of the ESG index in the tourism industry in the years under investigation.

3. Methodology

3.1. Data and Sample

A quantitative methodology was chosen for this study, building on its use in previous related research that explored similar cases (Chen et al., 2023; Rodríguez-Fernández et al., 2019; Rahman et al., 2023)

The data were obtained from Refinitiv Eikon, a database that provides essential economic and financial data, as well as information on ESG components related to sustainability indexes. Moreover, Refinitiv Eikon is a globally recognized and academically validated ESG data provider. This source has been widely employed in the empirical research investigating the relationship between ESG and firm performance (Velte, 2017; Buallay, 2019; Alareeni & Hamdan, 2020; Dorfleitner et al., 2020; Naeem et al., 2022). The study covers a five-year period (2017–2021) and includes a balanced panel of publicly listed tourism services firms. Similar sample periods and scopes have been successfully used in ESG-related panel data analyses across different industries (Makhdalena et al., 2023). The use of Return on Assets (ROA) as a proxy for financial performance is also well-supported in the literature, particularly in service sectors, due to its ability to reflect operational efficiency without being overly sensitive to leverage effects. The inclusion of firm size and leverage as control variables further enhances the model’s explanatory power and adjusts for potential firm-level heterogeneity. These methodological choices align with the established practices in the ESG-financial performance research, thereby supporting the robustness and generalizability of the inferences drawn from the analysis.

The final sample of 154 listed tourism firms provides a sufficient basis for robust statistical inference. The countries included in the sample are shown in Table 1. Accordingly, the largest proportion of firms in the sample is in the US, followed by the UK and Austria, countries with strong and developed economies. In total, the sample consisted of a total of 154 countries. According to Hair et al. (2010), panel data analyses typically require a minimum of 100–150 cross-sectional units to yield reliable estimates, especially when controlling for multiple variables. Our dataset not only meets but exceeds this threshold. Moreover, the panel spans five years, resulting in a total of 770 firm-year observations, which further increases the statistical power and validity of the regression results. Prior studies on ESG and financial performance in emerging sectors (Velte, 2017; Alareeni & Hamdan, 2020) have successfully employed similarly sized samples, supporting the methodological soundness of our approach.

Table 1.

Origin and number of the examined firms by country.

Building on this validated dataset and appropriately sized sample, we proceeded with the empirical analysis to examine the hypothesized relationships between ESG dimensions and financial performance. OLS regression analyses were conducted to examine the effect of the independent ESG variables on the dependent variable, financial performance, measured through ROA. After identifying all independent factors predicting the dependent variable, the data were used to create a precise estimation of the influence they had on the outcome variable. Heterogeneity tests were performed since the sample consisted of different countries with varying economic magnitudes, making it important to assess how the independent variables varied in 2017–2021.

Additionally, the analysis was supported by descriptive statistical analyses, robustness tests were executed to ensure the validity and reliability of the results, and the Durbin–Watson test was conducted to detect autocorrelation issues. The empirical analysis was performed using SPSS v.26 and Gretl released 2025a.

3.2. Variable Definitions and Model

3.2.1. Dependent Variable

In our study, we used Return on Assets (ROA) as the dependent variable, as a representative accounting-based performance indicator that more accurately measures resource allocation efficiency than other accounting metrics (Zabri et al., 2016). Furthermore, ROA captures the fundamentals of firm performance in a holistic manner, overcoming potential vulnerability present in widely used financial engineering indicators (e.g., debt leverage). Many previous studies have used ROA to measure firm performance (Fu & Li, 2023; Nirino et al., 2021; Makhdalena et al., 2023; Igbinovia & Agbadua, 2023).

ROA reflects the amount of earnings generated by invested capital assets (Epps & Cereola, 2008). Additionally, it measures how efficiently and profitably a firm utilizes its total assets in its operations and production processes to generate revenues, thereby indicating its operational performance. According to Lewellen (2004), ROA is the most important ratio for management to assess asset performance in relation to its strategic objectives, independent of its competitors. The use of ROA is advantageous in financial performance analysis due to its degrees of comparability, as it does not account for financing and leverage levels, unlike ROE. At the same time, stock market valuation indicators, such as Tobin’s Q, were excluded from this research due to their susceptibility to external factors. Specifically, in cases where a firm is underinvested, capital expenditure remains limited, and its market valuation remains high. Unlike market-based ratios, such as Tobin’s Q, which can be influenced by investor expectations and market fluctuations, ROA provides a more stable assessment of operational efficiency and profitability.

3.2.2. Explanatory Variable (ESG)

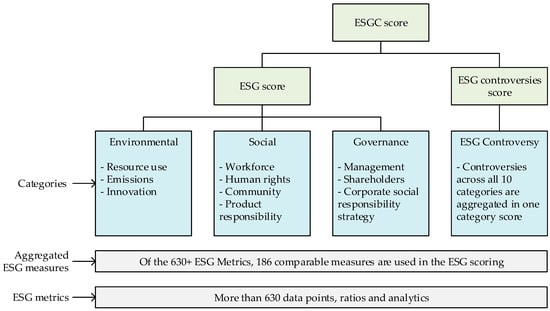

In this study, the independent variables are the three pillars of the ESG score—Environmental, Social, and Governance—along with the ESG controversies score, which is the most recent pillar of ESG. Additionally, this study includes the ESG combined score, which incorporates controversies into the ESG assessment. The Environment, Social, and Governance pillars are grouped into 10 categories with 186 comparable metrics. Figure 2 illustrates the structure and components of the ESGC scoring framework used in this analysis, as defined by LSEG (https://www.lseg.com/en/investor-relations/annual-reports/2024 accessed on 24 May 2025). It visualizes how each ESG pillar and the controversies score are organized, weighted, and ultimately integrated into a combined ESG score.

Figure 2.

Structure and components of ESGC scoring framework. Source: LSEG, December 2023.

In particular, the environmental pillar (score) is the weighted sum of resource use, emissions, and innovation. Weightings reflect the diversity in the materiality level of different industries and are based on the importance of each metric for the specific industry on a scale from 1 to 10.

Similarly, the social pillar (score) represents the weighted sum of factors related to workforce, human rights, community, and product responsibility. More specifically, it indicates the firm’s effectiveness in upholding human rights, promoting diversity, ensuring equal opportunities, and protecting public health, among others.

The governance pillar (score) considers factors related to the firm’s impact on management, shareholders, and corporate social responsibility strategy. In this context, the management score measures the commitment to and effectiveness of complying with the best corporate governance practices. The shareholders’ score reflects the equal treatment of shareholders and the mechanisms to prevent takeovers. Finally, the CSR strategy score represents the transparency of ESG reporting and the adoption of policies that integrate economic, social, and environmental dimensions into corporate governance processes.

The ESG controversies score reflects a firm’s involvement in scandals and actions that negatively impact the 10 categories of the ESG pillars. Controversies represent a new category in the ESG score methodology, as they encompass negative, publicly available information related to ESG pillars and are classified into 23 controversy topics, benchmarked against corresponding industry-specific metrics. Firms without reported controversies received a score of 100. Since large-cap firms attract more media attention, the Refinitiv methodology applies different severity weights to mitigate market-cap bias.

The ESG combined score is a variable that, according to the methodology, is influenced by the controversies score. There are two methods of calculation based on the relationship between the ESG score and the ESG controversies score. In case the controversies score is greater than or equal to the ESG score, then the ESG combined score is equal to the ESG score. However, if the ESG controversies score is lower than the ESG score, then the ESG combined score is calculated as the average of the two.

3.2.3. Control Variables

In line with Wang and Wang (2022); Habib and Mourad (2024); and Demiraj et al. (2023), we employed the following control variables in order to assess their impact on the dependent variable.

Firm size. On the one hand, larger firms have the financial capacity to disclose and, in many cases, implement more ESG-related practices. On the other hand, the size of firms often requires them to disclose a wide range of information to have a positive impact on stakeholders and to demonstrate compliance with their country’s regulations as well as international practices. For these reasons, we used the size of the firm as a control variable in terms of the logarithm of total assets at the end of the period.

Leverage ratio. The choice of this variable is also based on the research by Ghosh (2013), which argues that directors tend to reveal more ESG data when debt levels increase, due to greater pressure from financial institutions. On the contrary, firms with higher debt ratios do not have the same capacity to allocate funds to ESG-related practices. For these reasons, we evaluated the leverage ratio by dividing firms’ debts by their shareholders’ equity.

3.2.4. Model

In this model, we used ROA as the dependent variable to measure financial performance (Bodhanwala & Bodhanwala, 2022). The independent variables’ ESG pillars, ESG controversies, and ESG combined, were introduced to different models to investigate their individual and overall effects on financial performance. In all model equations, the control variables were included to account for order-influencing factors. We used the following models:

4. Results and Discussion

To evaluate our data, we first conducted normality tests and analyzed the frequency distribution of values using statistical tools. In particular, the variable-frequency command for all variables indicated a p-value close to zero, and subsequently the normality test (Jarque–Bera) was used, confirming that both the independent and dependent variables did not follow a normal distribution. These tests form the basis for selecting the appropriate statistical method (regression analysis) to ensure result validity and avoid using models that assume normality in the sample (e.g., OLS regression).

Additionally, all variables were checked for outliers to assess their potential impact on the analysis. Using the IQR (interquartile range) and boxplots, we found that the variables’ ESG controversies score and ROA have outliers. At this stage of the analysis, and to better represent the data, we proceed with descriptive statistics.

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics, including the mean, median, standard deviation, and minimum/maximum values, for the variables ROA, ESG combined score, environmental pillar score, social pillar score, governance pillar score, and ESG controversies score.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics.

For all variables, we can observe a large standard deviation, indicating a high variance of the sample values. The exception is the independent variable ESG controversies score, which exhibits the most symmetric distribution with high values mostly close to 100. In contrast, the dependent variable, ROA, shows significant asymmetry (min. −1.8843). The large variations in the variables reflect differences in Environmental, Social, and Economic indicators, which depend on the geographical areas considered, the economic conditions of the countries, and their governance systems. The observed heterogeneity of the tourism industry aligns with the objectives of this research, as maintaining these characteristics reflects the diversity in the structure of firms within the industry. Contrary to other studies (Demiraj et al., 2023), neither minorizing the variables nor the removal of outliers was applied.

Based on the above analysis, we proceed with non-parametric tests to determine whether the variables are correlated. The choice of the non-parametric method was based on the argument that data standardization was not necessary. Specifically, the independent ESG variables were assessed on the same scale (1–100), and normalization would not enhance their comparability further. Ensuring that no independent variable exerts a disproportionate influence on the model, the results of the pairwise tests on Spearman’s rho are shown in the table below.

According to Table 3, there is a very-strong positive correlation between the ESG combined score and the environmental and social pillar scores (0.9056 and 0.9228, respectively), in contrast with the ESG controversies score, which exhibits a weak, negative correlation with the other ESG indicators. This suggests that as controversies increase, both the ESG combined score and the other ESG pillars tend to decrease.

Table 3.

Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients.

ROA exhibits a weak, positive correlation with the individual ESG pillars, with the social pillar showing the highest correlation. The value of the control variable leverage (−0.3405) reflects the low Return on Assets, showing a negative correlation with ROA, which suggests that high leverage and borrowing costs do not translate into a corresponding increase in returns and net profitability in the tourism industry.

Our research data consist of cross-sectional data from 154 firms in the tourism industry, combined with time-series data spanning the period from 2017 to 2021. These panel data were initially analyzed using the pooled OLS method to assess their predictive ability, followed by diagnostic tests. The initial results of the linear regression analysis are presented in Table 4 below.

Table 4.

Pooled OLS regression analysis.

We conducted tests for heteroskedasticity, autocorrelation, and normality of residuals. The findings provide evidence of a non-normal distribution of residuals along with autocorrelation, violating the basic assumptions of this model. Nevertheless, the p-value from the White test indicates that the residuals exhibit stable variance. Consequently, the coefficients of the OLS model and the dependent variable can be correctly interpreted. However, given that the residuals are autocorrelated—violating their independence and potentially depending on prior values—we proceeded with the Hausman test to determine whether a random-effects or fixed-effects model would be more appropriate.

The results of the Hausman test show that the random effects model does not ensure the reliability of the parameter estimates. Specifically, the p-value < 0.05 in the null hypothesis, which favors the random-effects model, led us to choose the fixed-effects model as a more appropriate approach.

The results of the statistical test indicate that there are unobserved characteristics in the sample that are correlated with ESG performance, highlighting the necessity of using the fixed-effects model. However, since our objective is to examine the effect of ESG practices on the financial performance of tourism firms, it is essential to isolate unobserved characteristics that may bias the results, such as geographical region and corporate culture. The fixed-effects model allows for the isolation of these characteristics, focusing exclusively on variations within the firms themselves, thus enabling a more accurate assessment of the impact of ESG practices.

The results of the statistics analysis are presented in Table 5 estimating the impact of each independent variable—ESG pillars, ESG controversies, and the ESG combined score—on ROA, as shown in Model 1a, Model 1b, Model 1c, Model 2, and Model 3.

Table 5.

Panel fixed-effects regression results.

According to Table 5, we first observe that the constant term (const) in all models is positive and statistically significant, indicating a baseline relationship between the financial performance and the dependent variable, regardless of the values of the ESG independent variables. An inverse relationship is observed between the control variables’ firm size and leverage and the financial performance of tourism firms, as both exhibit a negative and statistically significant association with Return on Assets (ROA). Increased reliance on debt capital does not appear to yield higher profits in 2017–2021, while firm size does not contribute to financial growth. In Models 1a, 1b, and 1c, which focus on ESG pillars, a negative and statistically significant relationship is observed, explaining 7.9–10% of the variance in ROA after removing the impact of fixed effects.

The effect of the ESG controversies score on ROA (model 2) is positive and statistically significant. According to Refinitiv’s methodology, firms with no reported controversies receive the maximum score of 100, while any negative published information reduces the score accordingly. The observed positive impact on firm performance is likely driven by increased sales and/or lower financing costs for firms without Environmental, Social, or Governance scandals, as these firms tend to adopt long-term sustainable growth strategies.

According to the signaling theory (Spence, 1973), credible ESG performance serves as a signal of quality and differentiation, enhancing a firm’s reputation. The absence of corporate scandals fosters trust among both society and investors, leading to a greater acceptance of the firm and its services. This trust contributes to stability and reduced stock volatility. Conversely, ESG controversies undermine investment efficiency, ultimately diminishing profitability (Ahmadi, 2024).

Finally, the ESG combined score exhibits a significantly negative relationship with ROA (model 3), with only a slight increase in explanatory power for the variance of the dependent variable. This result aggregates the individual negative correlations of the ESG pillars—except for ESG controversies—and indicates that, in the tourism industry during the examined period, a higher ESG combined score is not associated with increased profitability.

5. Conclusions

This research mainly delves into the impact of ESG pillars and controversies on the financial performance of the tourism industry. We explore each individual ESG dimension and the effect of the ESG combined score on the profitability of the hotel industry and entertainment services in the period from 2017 to 2021. After performing statistical tests, we argue that the most appropriate and reliable method for estimating the impact is the use of the fixed-effects model on panel data. The contribution of this research is to extend the existing literature on the tourism industry and its firms globally, as well as to provide a theoretical framework for empirical findings that have not been sufficiently studied, particularly regarding the impact of controversies on financial performance and their inclusion in the overall ESG combined score.

The results of this study indicate the existence of a statistically significant impact of ESG controversies and the immediate effects of incidents that are inconsistent with Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) principles on the financial performance of the sample firms. This result is comparable to that of Nirino et al. (2021), who aimed to explore the consequences of controversies using a database of European listed firms. They conclude that negative events reported in the media have a significant negative impact on firms’ performance, despite the presence of sustainability practices. On the contrary, the results of the present study show that each individual ESG dimension –apart from controversies—is inversely related to a firm’s economic growth. This is likely due to the investment of significant resources in sustainability practices that do not yield immediate benefits. The findings align with those of Demiraj et al. (2023), who found negative relationship between ESG factors and financial performance based on the data from 258 firms in the European tourism industry spanning the period from 2010 to 2019.

It is worth mentioning that during the years under study, the global economy experienced significant fluctuations. In particular, the tourism industry, along with the trade industry, suffered a 9% contraction of GDP in 2020 due to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Thus, the negative correlation between ESG practices and profitability was further affected by excessively high operational costs and staff retention efforts, which were reflected in the increase in the ESG social score. According to Al Amosh and Khatib (2023), firms tend to comply with ethical behaviors during crises, increasing their ESG performance.

In addition, compliance with the NFRD directives, both in terms of governance transparency and social issues, especially in environmentally sensitive industries, such as tourism, contributed to the increase in the individual pillar scores, causing a decrease in ROA in the early years of implementation. These results are consistent with those of Cerciello et al. (2023), as both studies found that sustainability requirements imposed by the legal framework reduced profitability.

The results of this research should be of concern to stakeholders, customers, consumers, institutional investors, employees, suppliers, regulators, and legislators (N. Ahmad et al., 2021). In particular, the positive impact of ESG controversies on financial performance is a finding that requires further investigation to determine whether it reflects genuine initiatives supporting the 17 Sustainable Development Goals or whether it represents firms’ engagement in greenwashing practices. According to Ma et al. (2024), firms often participate in ESG initiatives for publicity and marketing purposes rather than investing in long-term sustainable development strategies, prioritizing short-term economic gain instead. Therefore, it is essential to consider that each analysis is influenced not only by the weight given to each ESG category, but also by the firm’s strategic adaptation to evolving circumstances and future benefits.

In the tourism industry, with a specific focus on the firms analyzed in this research, namely hotels and entertainment services, it is proposed that sustainability consultancy projects be subsidized, as they would have a positive impact on firms’ environmental footprint. At the same time, a measurable reduction in their environmental footprint, especially for firms that voluntarily publish such information, can serve as a criterion for public subsidies or the certification of their sustainability efforts. Furthermore, strengthening international certifications, such as LEED, and linking them to tax and financial incentives for firms can encourage the adoption of ESG practices. Additionally, integrating initiatives like Green Key into government subsidy policies would enhance hotels’ environmental performance. This would also bolster their long-term economic resilience by reducing operational costs and increasing their attractiveness to environmentally conscious consumers.

In summary, within the sample of firms, 47% are based in the U.S., and the study period includes the U.S.–China trade war (2018–2020). This major disruption has led to a reduction in investment in ESG-related investments due to declining economic growth. The non-mandatory application of the CSRD in countries outside the European Union was a limitation of this research. Nevertheless, in countries that do not implement the European Directive, both the legislative framework and external pressures from investors and activists encourage firms to disclose data through sustainability reports. This restrictive condition presents a potential avenue for future research, particularly regarding global efforts to establish a standardized legislative framework. In this regard, the European Financial Reporting Advisory Group (EFRAG) established the European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS) to promote transparency and enhance non-financial reporting across Europe, while also having the potential for a global impact.

While this study provides valuable insights into the ESG–financial performance relationship within the global tourism industry, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the measure of financial performance used in the analysis is limited to Return on Assets (ROA), which captures accounting-based profitability, but does not reflect market valuation or investor sentiment. The absence of market-based indicators, such as Tobin’s Q or the Market-to-Book Ratio, may constrain the scope of our conclusions regarding the financial value creation. Second, although the dataset comprises a balanced panel of 154 firms over five years (yielding 770 firm-year observations), which exceeds the recommended minimum for panel regression (Hair et al., 2010), it may not fully capture the breadth of ESG adoption across the wider tourism industry available in commercial databases, like Refinitiv. Third, our control variables include firm size and leverage, two of the most-used firm-level financial indicators. However, other relevant controls, such as firm age, capital intensity, ownership structure, or regional factors, can add nuance and help mitigate potential omitted variable bias.

Future research should address the limitations outlined above by incorporating alternative financial performance metrics that include both accounting and market-based measures. Expanding the dependent variable set to include Tobin’s Q or stock returns would allow for a more comprehensive evaluation of how ESG activities are perceived and valued by capital markets. Additionally, future studies should consider larger and more heterogeneous samples of tourism-related firms, including small- and medium-sized enterprises or firms operating in specific regions. This would improve the generalizability and capture a broader spectrum of ESG engagement practices. Methodologically, incorporating further control variables, such as firm age, R&D intensity, capital expenditures, or board diversity (Sotiropoulos et al., 2023), could enhance model precision and isolate ESG effects more clearly. Finally, longitudinal analyses extending beyond 2021 would help evaluate the lasting impact of ESG behavior post-COVID-19 and consider the recently implemented CSRD regulatory framework.

Moreover, it would be of significant research interest to explore how compliance with new regulatory standards affects the sustainable development and economic performance of tourism enterprises. Specifically, future research should investigate how the adoption of such standards influences corporate reputation and consumer trust, as well as whether changes in the regulatory framework lead to improved or diminished economic performance. Furthermore, it would be valuable to assess, through a global sample of tourism-related firms, how tax incentives and subsidies impact the adoption of sustainable practices. Additionally, sustainability certifications (e.g., LEED, Green Key) could be categorized based on their economic impact, considering the mediating role of government subsidies in facilitating their adoption.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.M. and A.P.; methodology, M.S.; software, C.M.; validation, M.S., A.P. and P.K.; formal analysis, C.M.; investigation, C.M.; resources, P.K.; data curation, C.M.; writing—original draft preparation, C.M.; writing—review and editing, M.S.; visualization, M.S.; supervision, P.K.; project administration, A.P.; funding acquisition, P.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ahmad, H., Yaqub, M., & Lee, S. H. (2023). Environmental-, social-, and governance-related factors for business investment and sustainability: A scientometric review of global trends. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 26(2), 2965–2987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, N., Mobarek, A., & Roni, N. N. (2021). Revisiting the impact of ESG on financial performance of FTSE350 UK firms: Static and dynamic panel data analysis. Cogent Business & Management, 8(1), 1900500. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmadi, A. (2024). The effect of ESG controversies on the sustainable investment. Energy Research Letters, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Amosh, H., & Khatib, S. F. A. (2023). ESG performance in the time of COVID-19 pandemic: Cross-country evidence. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 30(14), 39978–39993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alareeni, B. A., & Hamdan, A. (2020). ESG impact on performance of US S&P 500-listed firms. Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society, 20(7), 1409–1428. [Google Scholar]

- Aouadi, A., & Marsat, S. (2018). Do ESG controversies matter for firm value? Evidence from international data. Journal of Business Ethics, 151, 1027–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbelo, A., Arbelo-Pérez, M., De Vera, V., & Bilgihan, A. (2025). Green premiums: Assessing the revenue impact of eco-certification in the hospitality sector. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 37(13), 64–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydoğmuş, M., Gülay, G., & Ergun, K. (2022). Impact of ESG performance on firm value and profitability. Borsa Istanbul Review, 22, S119–S127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, J.-H. (2022). Developing ESG evaluation guidelines for the tourism sector: With a focus on the hotel industry. Sustainability, 14(24), 16474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, T., Cheung, C., Kong, H., Kralj, A., Mooney, S., Nguyễn Thị Thanh, H., Ramachandran, S., Dropulić Ružić, M., & Siow, M. L. (2016). Sustainability and the tourism and hospitality workforce: A thematic analysis. Sustainability, 8(8), 809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumüller, J., & Grbenic, S. (2021). Moving from non-financial to sustainability reporting: Analyzing the EU Commission’s proposal for a Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD). Facta Universitatis, Series: Economics and Organization, 18(4), 369–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumüller, J., & Sopp, K. (2022). Double materiality and the shift from non-financial to European sustainability reporting: Review, outlook and implications. Journal of Applied Accounting Research, 23(1), 8–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker-Olsen, K. L., Cudmore, B. A., & Hill, R. P. (2006). The impact of perceived corporate social responsibility on consumer behavior. Journal of Business Research, 59(1), 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodhanwala, S., & Bodhanwala, R. (2022). Exploring relationship between sustainability and firm performance in travel and tourism industry: A global evidence. Social Responsibility Journal, 18(7), 1251–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breijer, R., & Orij, R. P. (2022). The comparability of non-financial information: An exploration of the impact of the non-financial reporting directive (NFRD, 2014/95/EU). Accounting in Europe, 19(2), 332–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buallay, A. (2019). Is sustainability reporting (ESG) associated with performance? Evidence from the European banking sector. Management of Environmental Quality: An International Journal, 30(1), 98–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnini Pulino, S., Ciaburri, M., Magnanelli, B. S., & Nasta, L. (2022). Does ESG disclosure influence firm performance? Sustainability, 14(13), 7595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerciello, M., Busato, F., & Taddeo, S. (2023). The effect of sustainable business practices on profitability. Accounting for strategic disclosure. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 30(2), 802–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S., Song, Y., & Gao, P. (2023). Environmental, social, and governance (ESG) performance and financial outcomes: Analyzing the impact of ESG on financial performance. Journal of Environmental Management, 345, 118829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, B., Ioannou, I., & Serafeim, G. (2014). Corporate social responsibility and access to finance. Strategic Management Journal, 35(1), 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicchiello, A. F., Marrazza, F., & Perdichizzi, S. (2023). Non-financial disclosure regulation and environmental, social, and governance (ESG) performance: The case of EU and US firms. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 30(3), 1121–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delegkos, A. E., Skordoulis, M., Kalantonis, P., & Xanthopoulou, A. (2022). Integrated reporting and value relevance in the energy sector: The case of European listed firms. Energies, 15(22), 8435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demiraj, R., Dsouza, S., & Demıraj, E. (2023). ESG scores relationship with firm performance: Panel data evidence from the European tourism industry. PressAcademia Procedia, 16(1), 116–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhaliwal, D. S., Li, O. Z., Tsang, A., & Yang, Y. G. (2011). Voluntary nonfinancial disclosure and the cost of equity capital: The initiation of corporate social responsibility reporting. The Accounting Review, 86(1), 59–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogru, T., Akyildirim, E., Cepni, O., Ozdemir, O., Sharma, A., & Yilmaz, M. H. (2022). The effect of environmental, social and governance risks. Annals of Tourism Research, 95, 103432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolmans, M., Bourguignon, G., Cibrario Assereto, C., & Dictus, T. (2021). From ‘non-financial’ to ‘sustainability’ reporting. Cleary Gottlieb. Available online: https://www.clearygottlieb.com/-/media/files/alert-memos-2021/the-corporate-sustainability-reporting-directive.pdf (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Dorfleitner, G., Kreuzer, C., & Sparrer, C. (2020). ESG controversies and controversial ESG: About silent saints and small sinners. Journal of Asset Management, 21(5), 393–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drosos, D., & Skordoulis, M. (2018). The role of environmental responsibility in tourism. Journal for International Business and Entrepreneurship Development, 11(1), 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epps, R. W., & Cereola, S. J. (2008). Do institutional shareholder services (ISS) corporate governance ratings reflect a company’s operating performance? Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 19(8), 1135–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union. (2014). Directive 2014/95/EU as regards disclosure of non-financial and diversity information by certain large undertakings and groups. Official Journal of the European Union. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:32014L0095&from=EN (accessed on 8 February 2025).

- European Union. (2022). Directive 2022/2464 as regards corporate sustainability reporting. Official Journal of the European Union. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:32022L2464 (accessed on 8 February 2025).

- Filimonau, V., Matute, J., Mika, M., Kubal-Czerwińska, M., Krzesiwo, K., & Pawłowska-Legwand, A. (2022). Predictors of patronage intentions towards ‘green’ hotels in an emerging tourism market. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 103, 103221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Font, X., Garay, L., & Jones, S. (2016). Sustainability motivations and practices in small tourism enterprises in European protected areas. Journal of Cleaner Production, 137, 1439–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R. E. (1984). Strategic management: A stakeholder approach. Pitman. [Google Scholar]

- Friede, G., Busch, T., & Bassen, A. (2015). ESG and financial performance: Aggregated evidence from more than 2000 empirical studies. Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment, 5(4), 210–233. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, M. (1970, September 13). The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits. New York Times Magazine. 122–126. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, T., & Li, J. (2023). An empirical analysis of the impact of ESG on financial performance: The moderating role of digital transformation. Frontiers in Environmental Science, 11, 1256052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A. (2013). Corporate sustainability and corporate financial performance: The Indian context (Working paper no. 721). Indian Institute of Management Calcutta. [Google Scholar]

- Godfrey, P. C., Merrill, C. B., & Hansen, J. M. (2009). The relationship between corporate social responsibility and shareholder value: An empirical test of the risk management hypothesis. Strategic Management Journal, 30(4), 425–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, A. M., & Mourad, N. (2024). The influence of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) practices on US firms’ performance: Evidence from the coronavirus crisis. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 15(1), 2549–2570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, A. S., & Meyer, D. F. (2022). Does countries’ environmental, social and governance (ESG) risk rating influence international tourism demand? A case of the Visegrád Four. Journal of Tourism Futures, 11(1), 62–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassel, L., Nilsson, H., & Nyquist, S. (2005). The value relevance of environmental performance. European Accounting Review, 14(1), 41–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igbinovia, I. M., & Agbadua, B. O. (2023). Environmental, social, and governance (ESG) reporting and firm value in Nigeria manufacturing firms: The moderating role of firm advantage. Jurnal Dinamika Akuntansi Dan Bisnis, 10(2), 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ionescu, G. H., Firoiu, D., Pirvu, R., & Vilag, R. D. (2019). The impact of ESG factors on market value of companies from travel and tourism industry. Technological and Economic Development of Economy, 25(5), 820–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isnurhadi, I., Oktarini, K. W., Meutia, I., & Mukhtaruddin, M. (2020). Effects of stakeholder engagement and corporate governance on integrated reporting disclosure. Indonesian Journal of Sustainability Accounting and Management, 4(2), 164–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junius, D., Adisurjo, A., Rijanto, Y. A., & Adelina, Y. E. (2020). The impact of ESG performance to firm performance and market value. Jurnal Aplikasi Akuntansi, 5(1), 21–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A., Bibi, S., Li, H., Fubing, X., Jiang, S., & Hussain, S. (2023). Does the tourism and travel industry really matter to economic growth and environmental degradation in the US: A sustainable policy development approach. Frontiers in Environmental Science, 11, 1147504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocherlakota, S., Aruna, C., & Sirisha Reddy, R. D. (2023). Do ESG had influence on return on investments of BRICS listed stock exchanges: An empirical study. European Journal of Military Studies, 13(2), 6000–6011. [Google Scholar]

- Leopizzi, R., Pizzi, S., & D’Addario, F. (2021). The relationship among family business, corporate governance, and firm performance: An empirical assessment in the tourism sector. Administrative Sciences, 11(1), 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewellen, J. (2004). Predicting returns with financial ratios. Journal of Financial Economics, 74(2), 209–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J., Haider, Z. A., Jin, X., & Yuan, W. (2019). Corporate controversy, social responsibility and market performance: International evidence. Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money, 60, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luu, E., & Rubio, S. (2024). Millennial managers. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 32(4), 732–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y., Feng, G. F., Yin, Z. J., & Chang, C. P. (2024). ESG disclosures, green innovation, and greenwashing: All for sustainable development? Sustainable Development, 33(2), 1797–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhdalena, M., Zulvina, D., Zulvina, Y., Amelia, R. W., & Wicaksono, A. P. (2023). ESG and firm performance in developing countries: Evidence from ASEAN. Etikonomi, 22(1), 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moneva, J. M., Bonilla-Priego, M. J., & Ortas, E. (2020). Corporate social responsibility and organisational performance in the tourism sector. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 28(6), 853–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, N., Cankaya, S., & Bildik, R. (2022). Does ESG performance affect the financial performance of environmentally sensitive industries? A comparison between emerging and developed markets. Borsa Istanbul Review, 22, S128–S140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nirino, N., Santoro, G., Miglietta, N., & Quaglia, R. (2021). Corporate controversies and company’s financial performance: Exploring the moderating role of ESG practices. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 162, 120341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohlson, J. A. (1995). Earnings, book values, and dividends in equity valuation. Contemporary Accounting Research, 11(2), 661–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oikonomou, I., Brooks, C., & Pavelin, S. (2012). The impact of corporate social performance on financial risk and utility: A longitudinal analysis. Financial Management, 41(2), 483–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oklevik, O., Gössling, S., Hall, C. M., Jacobsen, J. K. S., Grøtte, I. P., & McCabe, S. (2020). Overtourism, optimisation, and destination performance indicators: A case study of activities in Fjord Norway. In Tourism and degrowth (pp. 60–80). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz-Martínez, E., & Marín-Hernández, S. (2024). Sustainability information in European small-and medium-sized enterprises. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 15(2), 7497–7522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M. E., & van der Linde, C. (1995). Toward a new conception of the environment-competitiveness relationship. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 9(4), 97–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, H. U., Zahid, M., & Al-Faryan, M. A. S. (2023). ESG and firm performance: The rarely explored moderation of sustainability strategy and top management commitment. Journal of Cleaner Production, 404, 136859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Fernández, M., Sánchez-Teba, E. M., López-Toro, A. A., & Borrego-Domínguez, S. (2019). Influence of ESGC indicators on financial performance of listed travel and leisure companies. Sustainability, 11(19), 5529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skordoulis, M., Kavoura, A., Stavropoulos, A. S., Zikas, A., & Kalantonis, P. (2025). Financial stability and environmental sentiment among millennials: A cross-cultural analysis of Greece and the Netherlands. International Journal of Financial Studies, 13(2), 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skordoulis, M., Kyriakopoulos, G., Ntanos, S., Galatsidas, S., Arabatzis, G., Chalikias, M., & Kalantonis, P. (2022). The mediating role of firm strategy in the relationship between green entrepreneurship, green innovation, and competitive advantage: The case of medium and large-sized firms in Greece. Sustainability, 14(6), 3286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skordoulis, M., Ntanos, S., Kyriakopoulos, G. L., Arabatzis, G., Galatsidas, S., & Chalikias, M. (2020). Environmental innovation, open innovation dynamics and competitive advantage of medium and large-sized firms. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 6(4), 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skordoulis, M., Patsatzi, O., Kalogiannidis, S., Patitsa, C., & Papagrigoriou, A. (2024a). Strategic management of multiculturalism for social sustainability in hospitality services: The case of hotels in Athens. Tourism and Hospitality, 5(4), 977–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skordoulis, M., Stavropoulos, A. S., Papagrigoriou, A., & Kalantonis, P. (2024b). The strategic impact of service quality and environmental sustainability on financial performance: A case study of 5-star hotels in Athens. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 17(10), 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotiropoulos, M., Skordoulis, M., Kalantonis, P., & Papagrigoriou, A. (2023). The impact of board diversity on firms’ performance: The case of retail industry in Europe. In The international conference on strategic innovative marketing and tourism (pp. 787–795). Springer Nature. [Google Scholar]

- Spence, M. (1973). Job Market Signaling. The Quarterly Journal Of Economics, 87(3), 355–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavropoulos, A. S., & Zounta, S. (2025). Cash conversion cycle and profitability: Evidence from Greek service firms. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(4), 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunlu, U. (2003). Environmental impacts of tourism. In D. Camarda, & L. Grassini (Eds.), Local resources and global trades: Environments and agriculture in the Mediterranean region (pp. 263–270). CIHEAM. [Google Scholar]

- Taliento, M., Favino, C., & Netti, A. (2019). Impact of environmental, social, and governance information on economic performance: Evidence of a corporate ‘sustainability advantage’ from Europe. Sustainability, 11(6), 1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. (2015). Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development. Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 14 April 2024).

- Velte, P. (2017). Does ESG performance have an impact on financial performance? Evidence from Germany. Journal of Global Responsibility, 8(2), 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voumik, L. C., Islam, M. A., & Nafi, S. M. (2024). Does tourism have an impact on carbon emissions in Asia? An application of fresh panel methodology. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 26(4), 9481–9499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S., & Wang, D. (2022). Exploring the relationship between ESG performance and green bond issuance. Frontiers in Public Health, 10, 897577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Travel & Tourism Council (WTTC). (2022). Travel & tourism economic impact. Available online: https://wttc.org/research/economic-impact (accessed on 21 April 2024).

- Yoon, B., & Chung, Y. (2018). The effects of corporate social responsibility on firm performance: A stakeholder approach. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 37, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabri, S. M., Ahmad, K., & Wah, K. K. (2016). Corporate governance practices and firm performance: Evidence from top 100 public listed companies in Malaysia. Procedia Economics and Finance, 35, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahid, R. A., Saleem, A., & Maqsood, U. S. (2023). ESG performance, capital financing decisions, and audit quality: Empirical evidence from Chinese state-owned enterprises. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 30(15), 44086–44099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J., Yang, D., Zhao, X., & Lei, M. (2023). Tourism industry and employment generation in emerging seven economies: Evidence from novel panel methods. Economic Research, 36(3), 2206471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y., Li, X., & Yuen, K. F. (2023). Sustainable shipping: A critical review for a unified framework and future research agenda. Marine Policy, 148, 105478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]