From Effectuation to Empowerment: Unveiling the Impact of Women Entrepreneurs on Small and Medium Enterprises’ Performance—Evidence from Indonesia

Abstract

1. Introduction

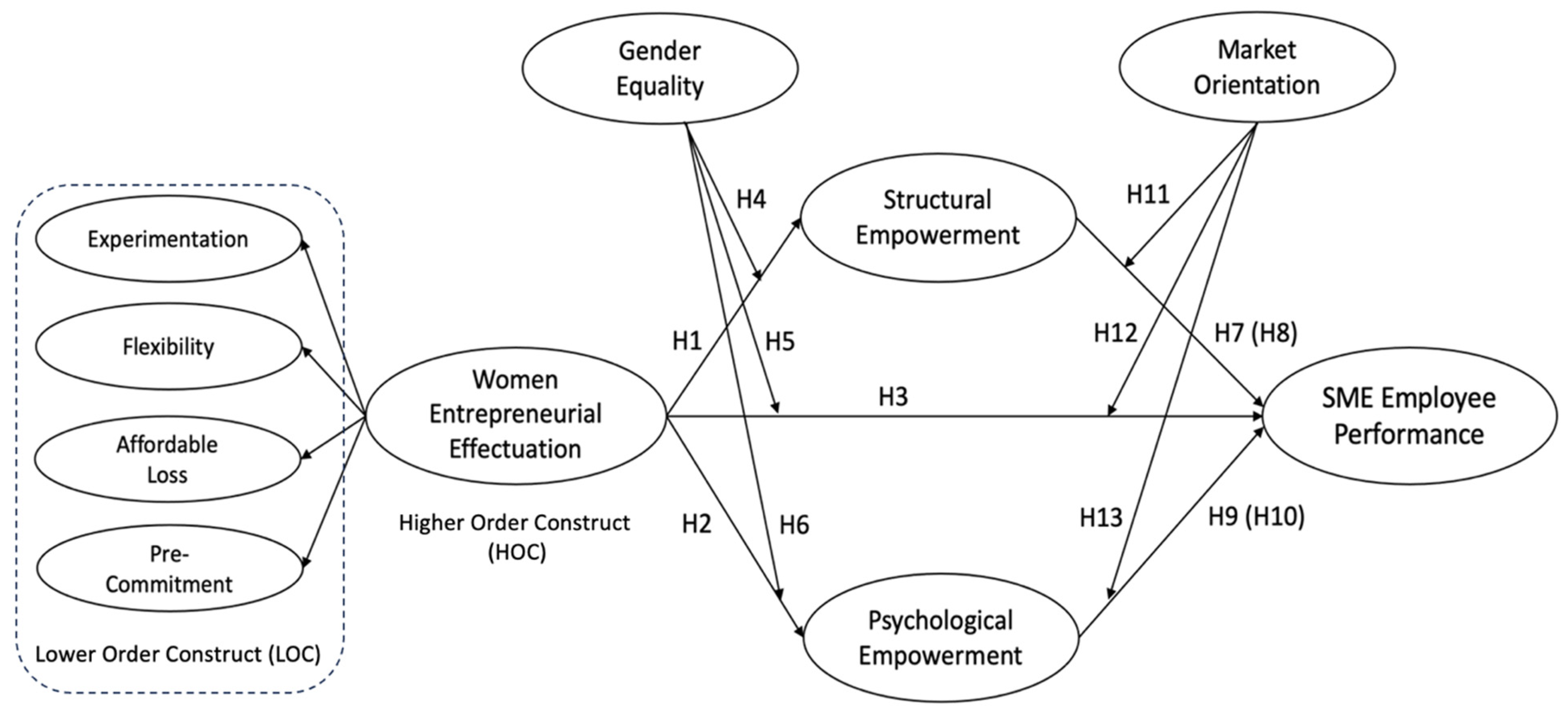

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses’ Development

3. Methods

4. Results

4.1. Respondents

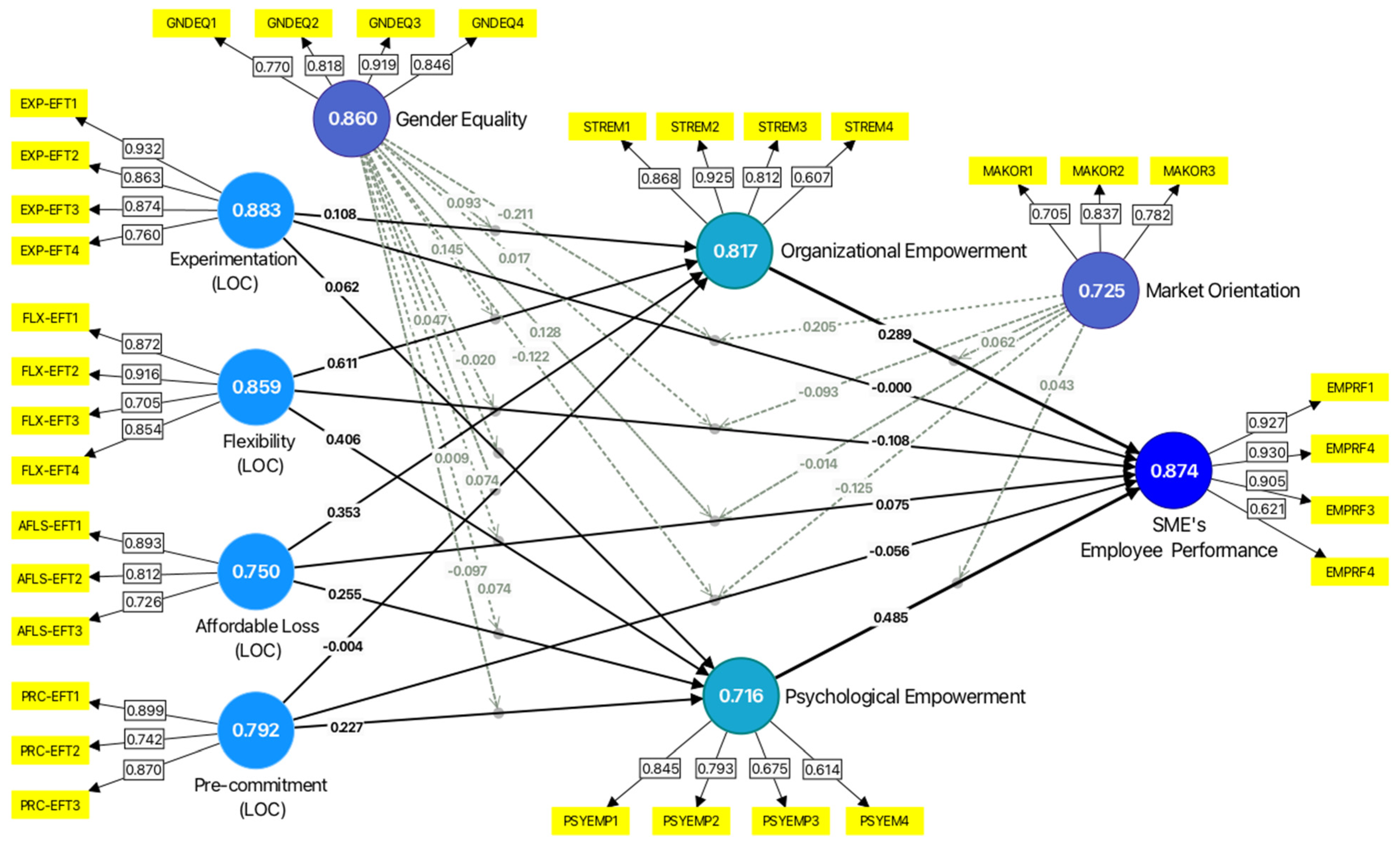

4.2. Measurement Model (Outer Model)

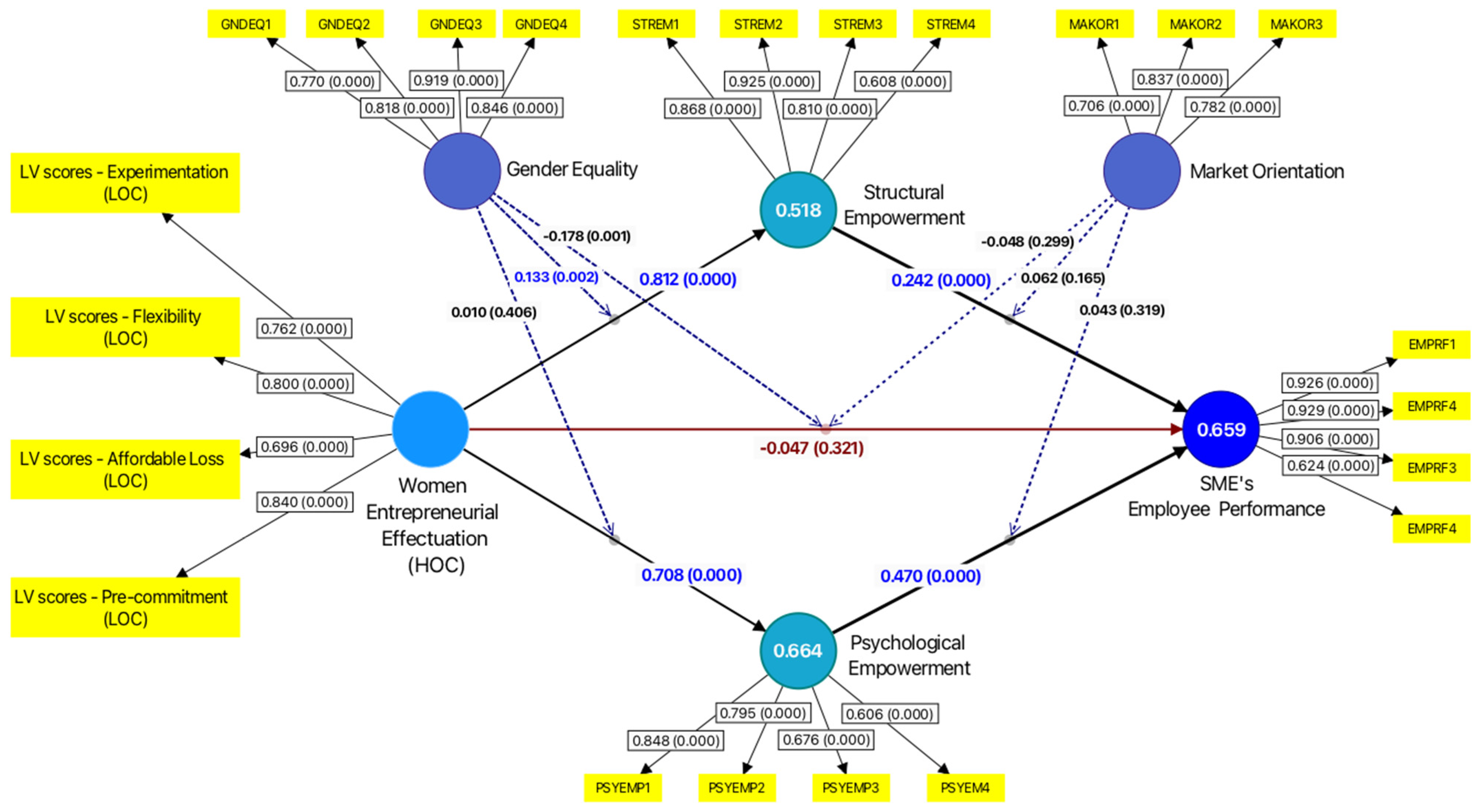

4.3. Structural Model (Inner Model)

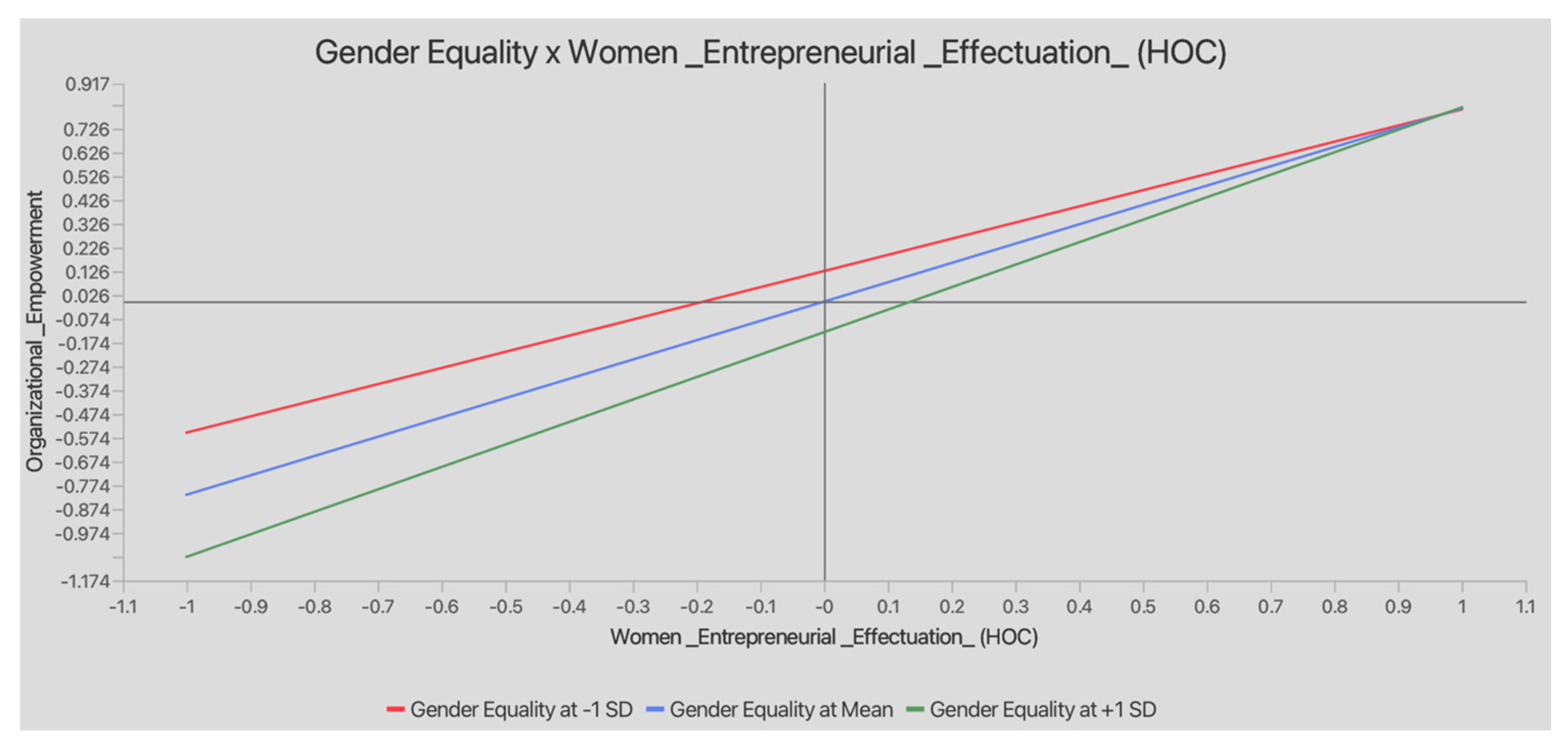

4.4. Structural Model (Inner Model)

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Acker, J. (1990). Hierarchies, jobs, bodies: A theory of gendered organizations. Gender & Society, 4(2), 139–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, A., Dhaliwal, R. S., & Nobi, K. (2018). Impact of structural empowerment on organizational commitment: The mediating role of women’s psychological empowerment. Vision: The Journal of Business Perspective, 22(3), 284–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N., Ullah, Z., Arshad, M. Z., Kamran, H. w., Scholz, M., & Han, H. (2021). Relationship between corporate social responsibility at the micro-level and environmental performance: The mediating role of employee pro-environmental behavior and the moderating role of gender. Sustainable Production and Consumption, 27, 1138–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amer, H. F., El-Naggar, N., & Osman, A. (2021). Women supporting women in Egypt’s digital entrepreneurship space. In Women, entrepreneurship, and development in the middle east (pp. 262–279). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, S. (2011). International entrepreneurship, born globals and the theory of effectuation. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 18(3), 627–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avolio, B. J., Zhu, W., Koh, W., & Bhatia, P. (2004). Transformational leadership and organizational commitment: Mediating role of psychological empowerment and moderating role of structural distance. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 25(8), 951–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azis, I. J. (2024). Listen and design. Springer Nature. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastian, B. L., Wood, B. P., & Ng, P. Y. (2023). The role of strong ties in empowering women entrepreneurs in collectivist contexts. International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship, 15(1), 122–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, J.-M., Cheah, J.-H., Gholamzade, R., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2023). PLS-SEM’s most wanted guidance. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 35(1), 321–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begum, S., Xia, E., Mehmood, K., Iftikhar, Y., & Li, Y. (2020). The impact of CEOs’ transformational leadership on sustainable organizational innovation in SMEs: A three-wave mediating role of organizational learning and psychological empowerment. Sustainability, 12(20), 862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berard, C., & Fréchet, M. (2020). Organizational antecedents of exploration and exploitation in SMEs. European Business Review, 32(2), 211–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bérard, C., & Cloutier, L. M. (2023). External information seeking and organizational ambidexterity in SMEs: Does empowerment climate matter? European Management Review, 21(2), 408–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brush, C., Edelman, L. F., Manolova, T., & Welter, F. (2018). A gendered look at entrepreneurship ecosystems. Small Business Economics, 53(2), 393–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brush, C. G., de Bruin, A., & Welter, F. (2009). A gender-aware framework for women’s entrepreneurship. International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship, 1(1), 8–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullough, A., Guelich, U., Manolova, T. S., & Schjoedt, L. (2021). Women’s entrepreneurship and culture: Gender role expectations and identities, societal culture, and the entrepreneurial environment. Small Business Economics, 58(2), 985–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacciolatti, L., & Lee, S. H. (2016). Revisiting the relationship between marketing capabilities and firm performance: The moderating role of Market Orientation, marketing strategy, and organisational power. Journal of Business Research, 69(12), 5597–5610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J. A. (2021). The moderating effect of gender equality and other factors on Pisa and education policy. Education Sciences, 11(1), 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandler, G. N., DeTienne, D. R., McKelvie, A., & Mumford, T. V. (2011). Causation and effectuation processes: A validation study. Journal of Business Venturing, 26(3), 375–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandna, V., & Salimath, M. S. (2020). When technology shapes community in the cultural and craft industries: Understanding virtual entrepreneurship in online ecosystems. Technovation, 92–93, 102042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charina, A., Kurnia, G., Mulyana, A., & Mizuno, K. (2022). The impacts of traditional culture on small industries longevity and sustainability: A case on Sundanese in Indonesia. Sustainability, 14(21), 14445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheema, F.-A., Zarif, T., & Nisa, A. (2016). Leadership styles of women entrepreneurs: An exploratory study at SME Sector at Karachi. Pakistan Journal of Applied Social Sciences, 4(1), 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J., & Liu, L. (2022). Effectuation, SME service innovation, and business customers’ value perception. The Service Industries Journal, 44(15–16), 1145–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coron, C. (2020). What does “gender equality” mean? Social representations of gender equality in the workplace among French workers. Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal, 39(8), 825–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, J. B., & Eberle, T. S. (2017). The process of empowerment: A study of empowerment in small and medium-sized enterprises. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- De Bruin, A., Brush, C. G., & Welter, F. (2006). Introduction to the special issue: Towards building cumulative knowledge on women’s entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 30(5), 585–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bruin, A., Shaw, E., & Lewis, K. V. (2017). The collaborative dynamic in social entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 29(7–8), 575–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vita, L., Mari, M., & Poggesi, S. (2014). Women entrepreneurs in and from developing countries: Evidences from the literature. European Management Journal, 32(3), 451–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dew, N., Read, S., Sarasvathy, S. D., & Wiltbank, R. (2009). Effectual versus predictive logics in entrepreneurial decision-making: Differences between experts and novices. Journal of Business Venturing, 24(4), 287–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dew, N., Read, S., Sarasvathy, S. D., & Wiltbank, R. (2010). On the entrepreneurial genesis of new markets: Effectual transformations versus causal search and selection. Journal of Evolutionary Economics, 21(2), 231–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolan, S. L., Bejarano, A., & Tzafrir, S. (2011). Exploring the moderating effect of gender in the relationship between individuals’ aspirations and career success among engineers in Peru. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 22(15), 3146–3167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drucker, P., & Maciariello, J. (2014). Innovation and entrepreneurship. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Echebiri, C., Amundsen, S., & Engen, M. (2020). Linking structural empowerment to employee-driven innovation: The mediating role of psychological empowerment. Administrative Sciences, 10(3), 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, G. (2012). Effectuation, causation, and bricolage: A behavioral comparison of emerging theories in entrepreneurship research. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 36(5), 1019–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, G., Stevenson, R., Neubert, E., Burnell, D., & Kuratko, D. F. (2020). Entrepreneurial hustle: Navigating uncertainty and enrolling venture stakeholders through urgent and unorthodox action. Journal of Management Studies, 57(5), 1002–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzke, S., Wu, J., Froese, F. J., & Chan, Z. X. (2022). Female entrepreneurship in Asia: A critical review and future directions. Asian Business & Management, 21(3), 343–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerhart, B., & Feng, J. (2021). The resource-based view of the firm, Human Resources, and human capital: Progress and prospects. Journal of Management, 47(7), 1796–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V. K., Chiles, T. H., & McMullen, J. S. (2016). A process perspective on evaluating and conducting effectual entrepreneurship research. Academy of Management Review, 41(3), 540–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2022). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Harini, S., Pranitasari, D., Said, M., & Endri, E. (2023). Determinants of SME performance: Evidence from Indonesia. Problems and Perspectives in Management, 21(1), 471–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, L. C. (2002). Measuring market orientation: Exploring a market oriented approach. Journal of Market-Focused Management, 5(3), 239–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauser, A., Eggers, F., & Güldenberg, S. (2019). Strategic decision-making in SMES: Effectuation, causation, and the absence of strategy. Small Business Economics, 54(3), 775–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hechavarria, D., Bullough, A., Brush, C., & Edelman, L. (2018). High-growth women’s entrepreneurship: Fueling social and economic development. Journal of Small Business Management, 57(1), 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendratmi, A., & Sukmaningrum, P. S. (2018). Role of government support and incubator organization to the success behaviour of women entrepreneurs: Indonesia women Entrepreneur Association. Polish Journal of Management Studies, 17(1), 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoque, M. S., & Islam, N. (2022). Leadership behaviors of women entrepreneurs in the SME sector of Bangladesh. Businesses, 2(2), 228–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J. (2017). The relationship between employee psychological empowerment and proactive behavior: Self-efficacy as mediator. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 45(7), 1157–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, M., & von Scheve, C. (2019). Power through empowerment? The managerial discourse on employee empowerment. Organization, 27(6), 777–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A. K., Srivastava, S., & Cubico, S. (2018). Women entrepreneurship in India: A work-life balance perspective. In Studies on entrepreneurship, structural change and industrial dynamics (pp. 301–311). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y., & Rüling, C.-C. (2017). Opening the black box of effectuation processes: Characteristics and dominant types. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 43(1), 171–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabeer, N. (2021). Gender equality, inclusive growth, and labour markets. In Women’s economic empowerment (pp. 13–48). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kafetzopoulos, D. (2020). Performance management of SMEs: A systematic literature review for antecedents and moderators. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 71(1), 289–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karri, R., & Goel, S. (2008). Effectuation and over–trust: Response to Sarasvathy and Dew. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 32(4), 739–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushik, N., Sharma, A., & Kumar Kaushik, V. (2014). Equality in the workplace: A study of gender issues in Indian organisations. Journal of Management Development, 33(2), 90–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N. (2015). Common method bias in PLS-SEM. International Journal of E-Collaboration, 11(4), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laschinger, H. K. S., Finegan, J., Shamian, J., & Wilk, P. (2001). Impact of structural and psychological empowerment on job strain in nursing work settings. JONA: The Journal of Nursing Administration, 31(5), 260–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, T.-J. (2015). Clusters, technological knowledge spillovers, and performance: The moderating roles of local ownership ties and a local market orientation. Management Decision, 53, 469–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, L. L., Hee, O. C., Kowang, T. O., Fei, T. H. C., Chuin, T. P., Patrick, Z., & Wu, C.-H. (2023). Psychological empowerment and job satisfaction on organizational commitment among SME employees. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 13(3), 190–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X., Zhu, Z., Liu, Z., & Fu, C. (2020). The influence of leader empowerment behaviour on employee creativity. Management Decision, 58(12), 2681–2703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, M. A., Ahmad, S., & Poespowidjojo, D. A. (2021). Psychological empowerment and individual performance: The mediating effect of intrapreneurial behaviour. European Journal of Innovation Management, 25(5), 1388–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, M. A., Blankson, C., Owusu-Frimpong, N., Nwankwo, S., & Trang, T. P. (2016). Market orientation, learning orientation and business performance. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 34(5), 623–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, F., Karoui Zouaoui, S., & Bel Haj Mohamed, A. (2024). The entrepreneurial support and the performance of New Venture Creation: The Mediation Effect of the acquisition of skills and the learning of novice entrepreneurs. Cogent Social Sciences, 10(1), 2330142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monje-Amor, A., Abeal Vázquez, J. P., & Faíña, J. A. (2020). Transformational leadership and work engagement: Exploring the mediating role of structural empowerment. European Management Journal, 38(1), 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozumdar, L., Materia, V. C., Hagelaar, G., Islam, M. A., Velde, G. v., & Omta, S. W. (2022). Contextuality of entrepreneurial orientation and business performance: The case of women entrepreneurs in Bangladesh. Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation in Emerging Economies, 8(1), 94–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muneer, S., Singh, A., Choudhary, M. H., & Alshammari, A. S. (2024). The mediating role of PSYCHOLOGICAL empowerment on the relationship between digital transformation, innovative work behavior, and organizational financial performance. Behavioral Sciences, 15(1), 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narver, J. C., & Slater, S. F. (1990). The effect of a market orientation on business profitability. Journal of Marketing, 54(4), 20–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickel, V., Leifeld, L., & Zehrer, A. (2023). 24 internalizing gender equality: Narratives of family business entrepreneurs. In De gruyter handbook of SME entrepreneurship (pp. 543–558). De Gruyte. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyoni, M., & Moos, M. (2022). The relationship between small business owners’ practice of effectuation and business growth in Gauteng townships. The Southern African Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business Management, 14(1), 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2023). Recent SME developments and forthcoming challenges. SME and Entrepreneurship Outlook (63). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osiyevskyy, O., Shirokova, G., & Ehsani, M. (2023). The role of effectuation and causation for SME survival amidst economic crisis. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior &Research, 29(7), 1664–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, R. K., & Jena, L. K. (2016). Employee performance at workplace: Conceptual model and empirical validation. Business Perspectives and Research, 5(1), 69–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pudjowati, J., Suman, A., Sakti, R. K., & Adi, P. M. (2018). The influence of SME empowerment towards sustainability of batik business: A study of handmade mangrove batik SME at Surabaya, Indonesia. Russian Journal of Agricultural and Socio-Economic Sciences, 76(4), 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Read, S., Dew, N., Sarasvathy, S. D., Song, M., & Wiltbank, R. (2009a). Marketing under uncertainty: The logic of an effectual approach. Journal of Marketing, 73(3), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Read, S., Sarasvathy, S., Dew, N., & Wiltbank, R. (2016). Effectual entrepreneurship. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Read, S., Song, M., & Smit, W. (2009b). A meta-analytic review of effectuation and venture performance. Journal of Business Venturing, 24(6), 573–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reymen, I., Berends, H., Oudehand, R., & Stultiëns, R. (2016). Decision making for business model development: A process study of effectuation and causation in new technology-based ventures. R&D Management, 47(4), 595–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaz, U., & Chaudhry, M. O. (2021). Role of small and Medium Enterprises (SME) in women empowerment and poverty alleviation in Punjab, Pakistan. International Journal of Agricultural Extension, 9(3), 439–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2016). Gain more insight from your PLS-SEM results. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 116(9), 1865–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C. M., Wende, S., & Becker, J.-M. (2022). SmartPLS 4. Oststeinbek: SmartPLS. Available online: https://www.smartpls.com (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Saifurrahman, A., & Kassim, S. H. (2023). Regulatory issues inhibiting the financial inclusion: A case study among Islamic banks and MSMES in Indonesia. Qualitative Research in Financial Markets, 16(4), 589–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarasvathy, S., & Dew, N. (2008). Effectuation and over–trust: Debating Goel and Karri. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 32(4), 727–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarasvathy, S. D. (2001). Causation and effectuation: Toward a theoretical shift from economic inevitability to entrepreneurial contingency. Academy of Management Review, 26(2), 243–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarasvathy, S. D. (2008). Competitive Advantages and entrepreneurial opportunities. Effectuation, 8, 171–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarasvathy, S. D. (2022). Relating effectuation to performance. Effectuation, 6, 124–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seibert, S. E., Wang, G., & Courtright, S. H. (2011). Antecedents and consequences of psychological and team empowerment in organizations: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(5), 981–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, P. N., Liengaard, B. D., Hair, J. F., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2022). Predictive model assessment and selection in composite-based modeling using PLS-SEM: Extensions and guidelines for using CVPAT. European Journal of Marketing, 57(6), 1662–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, C., & Shin, D. (2023). Structural empowerment, human capital, and organizational innovation capability. Academy of Management Proceedings, 2023(1), 14329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shmueli, G., Sarstedt, M., Hair, J. F., Cheah, J.-H., Ting, H., Vaithilingam, S., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). Predictive model assessment in PLS-SEM: Guidelines for using PLS_predict. European Journal of Marketing, 53(11), 2322–2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, M., Padmore, J., & Newman, N. (2012). Towards a new model of success and performance in SMEs. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 18(3), 264–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soumena, F. Y., Umaima, U., Nurwahida, N., & Syam, D. R. Y. (2024). The influence of SME funding and non-performing financing on Indonesia’s economic growth in the period 2015–2022. Return: Study of Management, Economic and Business, 3(3), 166–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spreitzer, G. M. (1995). Spreitzer’s psychological empowerment scale. PsycTESTS Dataset. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spreitzer, G. M. (2008). Taking stock: A review of more than twenty years of research on empowerment at work. In J. Barling, & C. L. Cooper (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of organizational behavior: Volume one: Micro approaches (pp. 54–72). SAGE Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Tanoto, S. R., & Tahalele, N. P. (2024). Assessing the influence of information technology on female entrepreneur empowerment in Indonesia: The role of social and psychological capitals. Indonesian Journal of Business and Entrepreneurship, 10, 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D. J. (2020). Hand in glove: Open innovation and the dynamic capabilities framework. Strategic Management Review, 1(2), 233–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teoh, W. M.-Y., Chong, C. W., Yuen, Y. Y., & Chong, S. C. (2021). Exploring SME women entrepreneurs’ work–family conflict in Malaysia. Entrepreneurial Activity in Malaysia, 157–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Berg, J., Alblas, A., Blanc, P. L., & Romme, A. G. (2021). How structural empowerment boosts organizational resilience: A case study in the Dutch Home Care Industry. Organization Studies, 43(9), 1425–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, S. V., & Ravikiran, A. R. (2012). Women entrepreneurs—Opportunities and challenges. Global Journal for Research Analysis, 3(8), 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuong, Q., Nguyen, H. T., Ho, M., & Nguyen, M. (2021). Adopting open access in an emerging country: Is gender inequality a barrier in humanities and social sciences? Learned Publishing, 34(4), 487–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wernerfelt, B. (2013). Small forces and large firms: Foundations of the RBV. Strategic Management Journal, 34(6), 635–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, V., & Unni, J. (2016). Women entrepreneurship: Research review and future directions. Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research, 6, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasir, M., Majid, A., Yousaf, Z., Nassani, A. A., & Haffar, M. (2021). An integrative framework of innovative work behavior for employees in SMEs linking knowledge sharing, functional flexibility and psychological empowerment. European Journal of Innovation Management, 26(2), 289–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yitshaki, R., Kropp, F., & Honig, B. (2021). The role of compassion in shaping social entrepreneurs’ prosocial opportunity recognition. Journal of Business Ethics, 179(2), 617–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X., Zhao, W., Wang, X., Ma, X., & Cao, G. (2024). Striking the balance: Configurations of causation and effectuation principles for SME performance. PLoS ONE, 19(6), e0302700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuniarty, Y., Prabowo, H., & Abdinagoro, S. B. (2021). The role of Effectual Reasoning in shaping the relationship between managerial-operational capability and innovation performance. Management Science Letters, 11(1), 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S., & Chen, R. (2019). Using education to enhance gender equality in the workplaces in China. Open Journal of Social Sciences, 7(9), 259–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, M. A. (2000). Empowerment theory: Psychological, organizational and community levels of analysis. In J. Rappaport, & E. Seidman (Eds.), Handbook of community psychology (pp. 43–63). Plenum Press. [Google Scholar]

| Description | Category | Number (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 18–24 | 41 | 19 |

| 25–29 | 61 | 28 | |

| 30–34 | 40 | 18 | |

| 35–39 | 37 | 17 | |

| 40–44 | 18 | 8 | |

| >45 | 21 | 10 | |

| Total | 218 | 100 | |

| Education | Junior high school | 63 | 29 |

| High school/similar level | 107 | 49 | |

| Under graduates/bachelor | 27 | 12 | |

| Others | 21 | 10 | |

| Total | 218 | 100 | |

| Length of work period at SME (years) | 1–2 | 63 | 29 |

| 3–5 | 45 | 21 | |

| 6–10 | 26 | 12 | |

| 11–15 | 24 | 11 | |

| >15 | 2 | 1 | |

| Total | 171 | 78 | |

| Marital status | Not yet married | 54 | 25 |

| Married | 143 | 66 | |

| Others | 21 | 10 | |

| Total | 218 | 100 | |

| Types of SMEs | Clothes/garments | 18 | 8 |

| Fashion accessories | 29 | 13 | |

| Packaged snacks | 19 | 9 | |

| Handicrafts | 42 | 19 | |

| Culinary | 72 | 33 | |

| Service | 21 | 10 | |

| Others | 17 | 8 | |

| Total | 218 | 100 | |

| Variable | Code | Indicator | OL |

|---|---|---|---|

| Affordable Loss (LOC) | AFLS-EFT1 | The woman leader in this SME is careful in managing investments according to the limits of the funds owned by this SME. | 0.893 |

| AFLS-EFT2 | The women leader in this SME manages the risk of costs incurred with careful calculations so that it does not become a hassle if something happens. | 0.812 | |

| AFLS-EFT3 | The woman leader in this SME calculates costs within the reserve fund limits that this SME can still afford. | 0.726 | |

| Mean = 3.839, CA = 0.750, Rho_a= 0.814, Rho_c = 0.853, AVE = 0.661 | |||

| Experimentation (LOC) | EXP-EFT1 | The woman leader in this SME encourages employees to develop new products that are different from existing ones. | 0.932 |

| EXP-EFT2 | The woman leader in this SME makes the current products different from their old products. | 0.863 | |

| EXP-EFT3 | The woman leader in this SME is trying to create a new product that is different from the initial concept. | 0.874 | |

| EXP-EFT4 | This female leader in this SME makes changes business processes to find more effective methods. | 0.760 | |

| Mean = 4.053, CA = 0.883, Rho_a = 0.927, Rho_c = 0.918, AVE = 0.739 | |||

| Flexibility (LOC) | FLX-EFT1 | The woman leader in this SME can adapt the organization’s activities to capture new opportunities that exist. | 0.872 |

| FLX-EFT2 | The woman leader in this SME tries to avoid rigid ways of working to move towards the changes needed. | 0.916 | |

| FLX-EFT3 | The woman leader in this SME is flexible and able to seize new opportunities in business. | 0.705 | |

| FLX-EFT4 | This SME was developed by a woman leader who can adapt to changes in the resources she has. | 0.854 | |

| Mean = 4.205, CA = 0.859, Rho_a = 0.880, Rho_c = 0.905, AVE = 0.707 | |||

| Pre-commitment (LOC) | PRC-EFT1 | The woman leader in this SME makes cooperation agreements with business partners as soon as possible. | 0.899 |

| PRC-EFT2 | The woman leader in this SME establishes cooperative ties with external parties such as suppliers to reduce uncertainty. | 0.742 | |

| PRC-EFT3 | The women leader in this SME seeks mutually beneficial cooperation agreements with other organizations earlier. | 0.870 | |

| Mean = 3.843, CA = 0.792, Rho_a = 0.846, Rho_c = 0.877, AVE = 0.706 | |||

| Structural Empowerment | STREM1 | Like others, I got the opportunity to develop my skills in this UKM. | 0.868 |

| STREM2 | In this SME, I can easily ask about the rules that apply in the workplace. | 0.925 | |

| STREM3 | In this SME, there is openness to discussing solving problems that occur in the workplace. | 0.812 | |

| STREM4 | I receive support if I need help in carrying out assignments in this SME. | 0.607 | |

| Mean = 3.908, CA = 0.817, Rho_a = 0.825, Rho_c = 0.883, AVE = 0.659 | |||

| Psychological Empowerment | PSYEMP1 | I am convinced that the work I do in this SME is important for my life. | 0.845 |

| PSYEMP2 | I believe that the work activities I do in this SME will bring prosperity to me in the future. | 0.793 | |

| PSYEMP3 | I am encouraged to be confident in doing my job well in this SME. | 0.675 | |

| PSYEMP4 | I am supported to have adequate skills to carry out the tasks given. | 0.614 | |

| Mean = 3.252, CA = 0.716, Rho_a = 0.758, Rho_c = 0.824, AVE = 0.544 | |||

| Employee Performance | EMPRF1 | I can usually complete the work that is my responsibility on time. | 0.927 |

| EMPRF2 | I usually work according to the standards set by the leaders in this SME. | 0.905 | |

| EMPRF4 | I can do my assignments well consistently and as is expected from time to time. | 0.930 | |

| EMPRF4 | I can still work well even under the pressure of work deadlines. | 0.621 | |

| Mean = 3.471, CA = 0.874, Rho_a = 0.929, Rho_c = 0.914, AVE = 0.732 | |||

| Gender Equality | GNDEQ1 | Wages for female workers are given without distinction of gender. | 0.770 |

| GNDEQ2 | Incentives are given regardless of the gender of workers in this SME. | 0.818 | |

| GNDEQ3 | Women are included in decision making when working in this UKM. | 0.919 | |

| GNDEQ4 | In my opinion, female workers in this SME have fair rights. | 0.846 | |

| Mean = 3.830, CA = 0.860, Rho_a = 0.875, Rho_c = 0.905, AVE = 0.706 | |||

| Market Orientation | MAKOR1 | The SMEs I work with seem to understand what today’s consumers want. | 0.705 |

| MAKOR2 | The SMEs where I work focus on efforts to increase consumer satisfaction. | 0.837 | |

| MAKOR3 | The SMEs where I work are able to adapt their products to new trends that consumers are interested in. | 0.782 | |

| Mean = 3.937, CA = 0.725, Rho_a = 0.822, Rho_c = 0.820, AVE = 0.603 | |||

| Path | HTMT Ratio | Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5.0% | 95.0% | ||

| Market Orientation <-> Gender Equality | 0.808 | 0.729 | 0.883 |

| Organizational Empowerment <-> Gender Equality | 0.529 | 0.427 | 0.623 |

| Organizational Empowerment <-> Market Orientation | 0.526 | 0.428 | 0.639 |

| Psychological Empowerment <-> Gender Equality | 0.813 | 0.741 | 0.882 |

| Psychological Empowerment <-> Market Orientation | 0.682 | 0.587 | 0.785 |

| Psychological Empowerment <-> Organizational Empowerment | 0.727 | 0.630 | 0.821 |

| Employee Performance <-> Gender Equality | 0.697 | 0.623 | 0.767 |

| Employee Performance <-> Market Orientation | 0.578 | 0.475 | 0.678 |

| Employee Performance <-> Organizational Empowerment | 0.673 | 0.593 | 0.749 |

| Employee Performance <-> Psychological Empowerment | 0.888 | 0.833 | 0.947 |

| Entrepreneurial Effectuation (HOC) <-> Gender Equality | 0.887 | 0.825 | 0.942 |

| Entrepreneurial Effectuation (HOC) <-> Market Orientation | 0.832 | 0.758 | 0.900 |

| Entrepreneurial Effectuation (HOC) <-> Organizational Empowerment | 0.872 | 0.811 | 0.934 |

| Entrepreneurial Effectuation (HOC) <-> Psychological Empowerment | 0.858 | 0.808 | 0.813 |

| Entrepreneurial Effectuation (HOC) <-> SME’s Employee Performance | 0.836 | 0.776 | 0.891 |

| Hypotheses | Std. Coefficient | p-Values | Confidence Interval | Result | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.0% | 95.0% | |||||

| H1 | WEE (HOC) -> STREM | 0.812 | 0.000 | 0.709 | 0.906 | Hypothesis supported |

| H2 | WEE (HOC) -> PSYEM | 0.708 | 0.000 | 0.605 | 0.813 | Hypothesis supported |

| H3 | WEE (HOC) -> SME’s Employee Performance | −0.047 | 0.321 | −0.211 | 0.117 | Hypothesis not supported |

| H4 | Gender Equality × WEE (HOC) -> STREM | 0.133 | 0.002 | 0.060 | 0.212 | Hypothesis supported |

| H5 | Gender Equality × WEE (HOC) -> SME’s Employee Performance | −0.178 | 0.001 | −0.274 | −0.079 | Hypothesis not supported |

| H6 | Gender Equality × WEE (HOC) -> PSYEM | 0.010 | 0.406 | −0.059 | 0.076 | Hypothesis not supported |

| H7 | STREM -> SME’s Employee Performance | 0.242 | 0.000 | 0.152 | 0.325 | Hypothesis supported |

| H8 | WEE (HOC) -> STREM -> SME’s Employee Performance | 0.196 | 0.000 | 0.122 | 0.269 | Hypothesis supported |

| H9 | PSYEM -> SME’s Employee Performance | 0.470 | 0.000 | 0.355 | 0.599 | Hypothesis supported |

| H10 | WEE (HOC) -> PSYEM -> SME’s Employee Performance | 0.333 | 0.000 | 0.247 | 0.438 | Hypothesis supported |

| H11 | MARKO × STREM-> SME’s Employee Performance | 0.062 | 0.165 | −0.050 | 0.161 | Hypothesis not supported |

| H12 | MARKO × WEE (HOC) -> SME’s Employee Performance | −0.048 | 0.299 | −0.195 | 0.099 | Hypothesis not supported |

| H13 | MARKO × PSYEM -> SME’s Employee Performance | 0.043 | 0.319 | −0.103 | 0.195 | Hypothesis not supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Theresia, S.; Sihombing, S.O.; Antonio, F. From Effectuation to Empowerment: Unveiling the Impact of Women Entrepreneurs on Small and Medium Enterprises’ Performance—Evidence from Indonesia. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 198. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15060198

Theresia S, Sihombing SO, Antonio F. From Effectuation to Empowerment: Unveiling the Impact of Women Entrepreneurs on Small and Medium Enterprises’ Performance—Evidence from Indonesia. Administrative Sciences. 2025; 15(6):198. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15060198

Chicago/Turabian StyleTheresia, Sherly, Sabrina Oktaria Sihombing, and Ferdi Antonio. 2025. "From Effectuation to Empowerment: Unveiling the Impact of Women Entrepreneurs on Small and Medium Enterprises’ Performance—Evidence from Indonesia" Administrative Sciences 15, no. 6: 198. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15060198

APA StyleTheresia, S., Sihombing, S. O., & Antonio, F. (2025). From Effectuation to Empowerment: Unveiling the Impact of Women Entrepreneurs on Small and Medium Enterprises’ Performance—Evidence from Indonesia. Administrative Sciences, 15(6), 198. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15060198