Key Drivers of ERP Implementation in Digital Transformation: Evidence from Austro-Ecuadorian

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Critical Success Factors (CSFs) for the Implementation of ERP in SMEs

- Top management support: The active backing and support of an organization’s top management for the implementation of an ERP system or project (Rahayu & Juliana Dillak, 2018).

- Effective project management: It involves the application of techniques, tools, and skills to plan, execute, and control projects efficiently to achieve their ERP objectives (Al-Fawaz et al., 2008).

- Change management: Any ERP implementation process requires managing and controlling organizational changes in a planned and structured way to minimize resistance and maximize adoption (Shaul & Tauber, 2013).

- Communication: It consists of the effective transmission of information, ideas, and opinions among the different stakeholders of a project or system (Dezdar & Ainin, 2011).

- Implementation strategy: A detailed plan that guides the implementation of a system or project, including the necessary activities, resources, and timelines (Saade & Nijher, 2016).

- User training and education: In the end, end-users can be provided with the training and education necessary to effectively use a new system or technology (Shaul & Tauber, 2013).

2.2. Highlights for Implementing ERP in SMEs

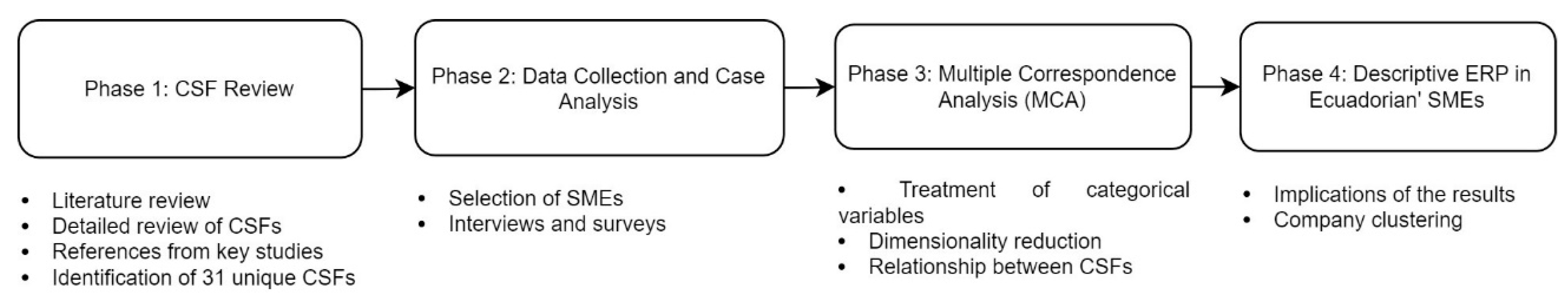

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Phase 1: CSF Review

3.2. Phase 2: Data Collection and Case Analysis

3.3. Phase 3: Multiple Correspondence Analysis (MCA)

3.4. Phase 4: Descriptive ERP in Ecuadorian SMEs

4. Results

4.1. Statistical Analysis of the Samples

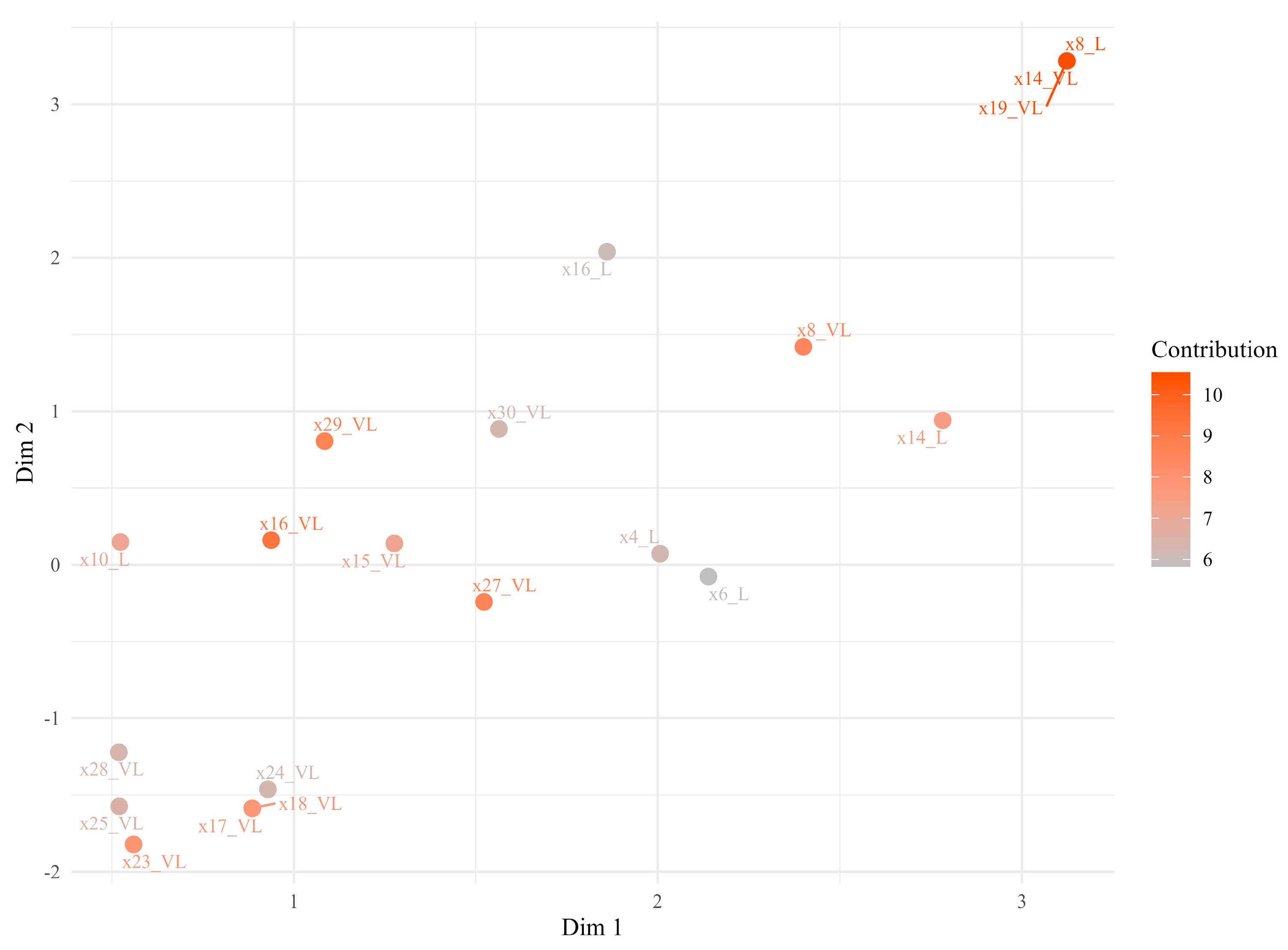

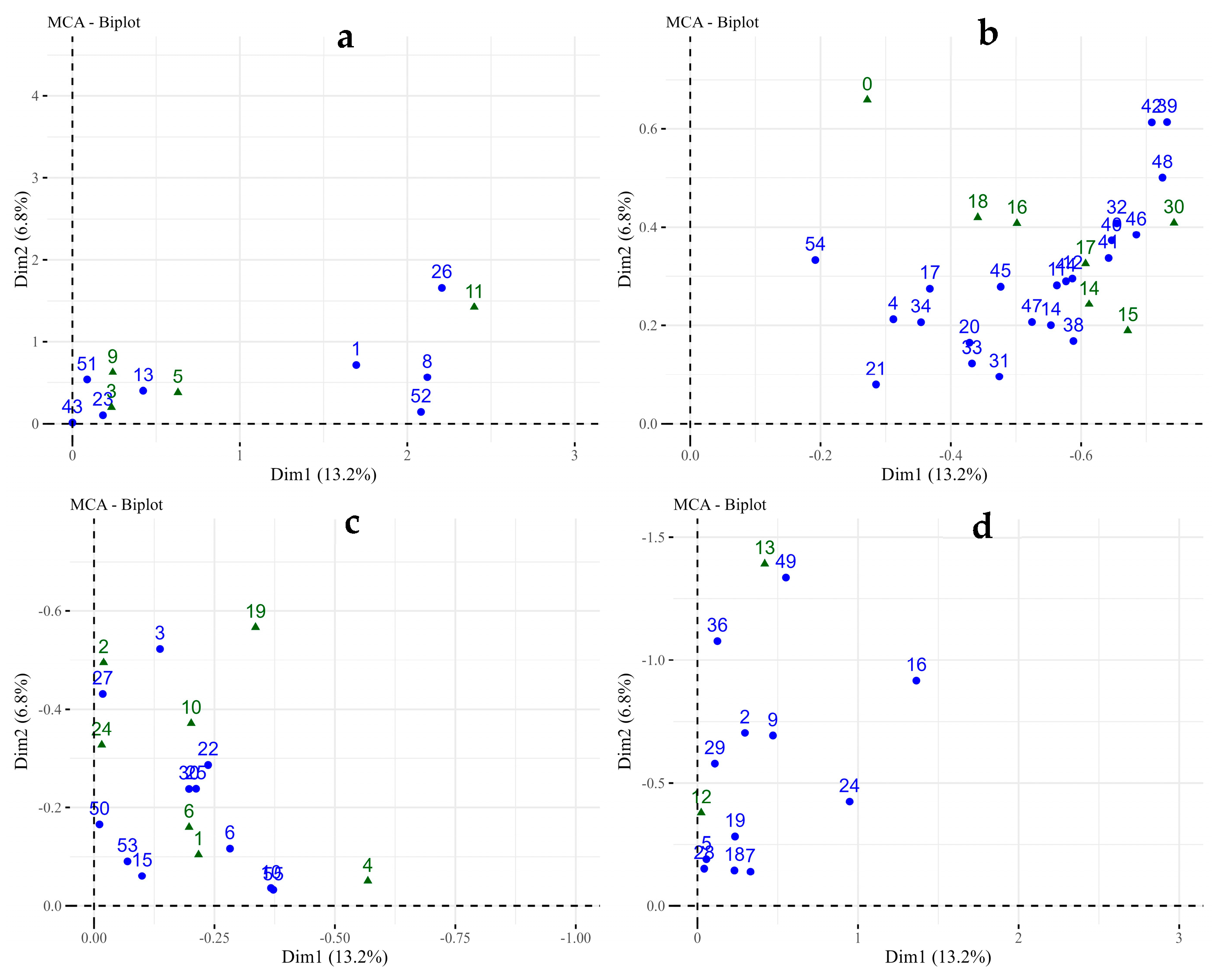

4.2. Development of the MCA Method

Quadrant Analysis

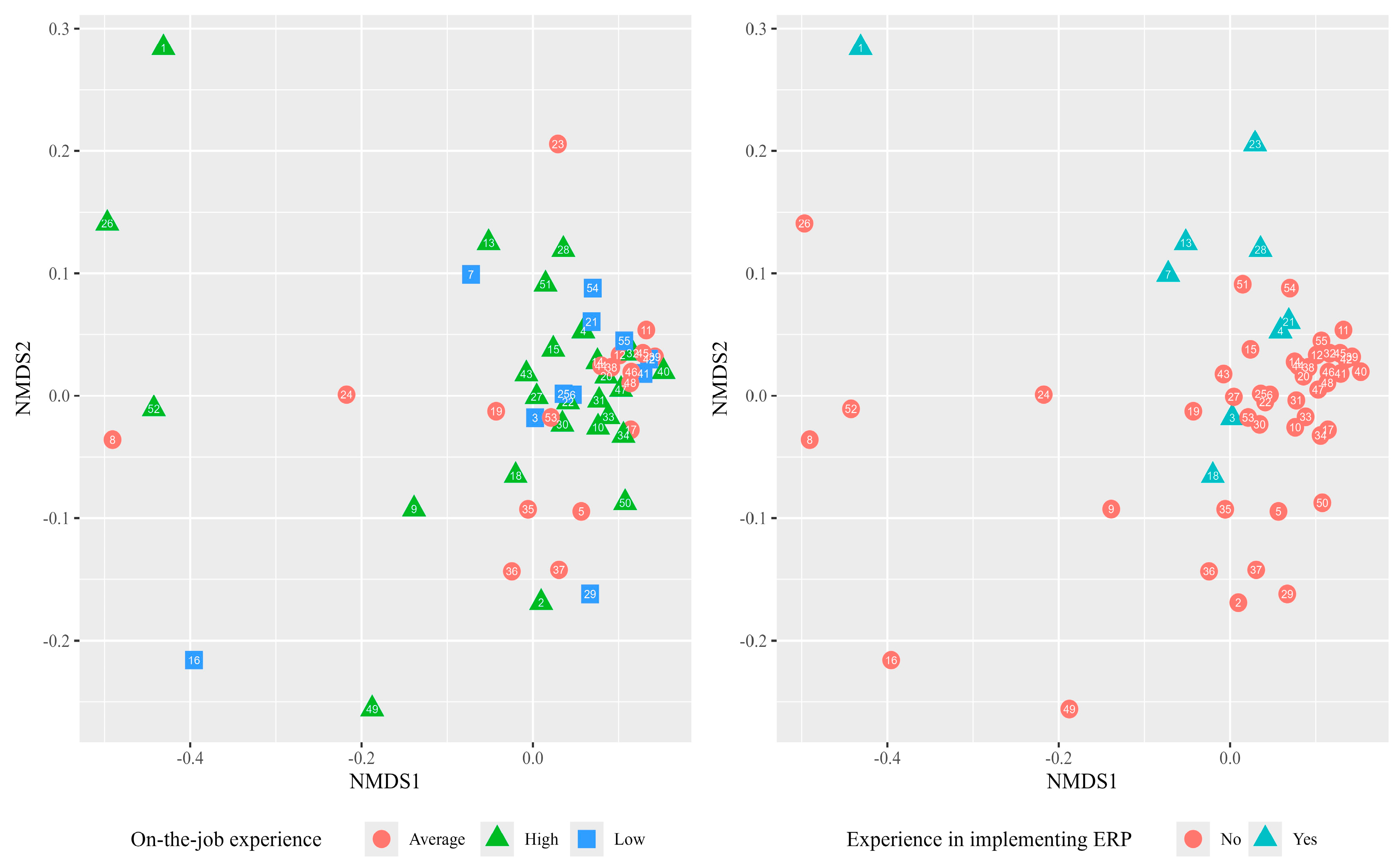

4.3. Analysis of the CSF with Supplementary Variables

Cluster Analysis

5. Discussion

5.1. Common Patterns and Strategic Differences

5.2. ERP Implementation Profiles

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Achanga, P., Shehab, E., Roy, R., & Nelder, G. (2006). Critical success factors for lean implementation within SMEs. Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management, 17(4), 460–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aini, S., Lubis, M., Witjaksono, R. W., & Hanifatul Azizah, A. (2020, June 25–27). Analysis of critical success factors on ERP implementation in PT. Toyota astra motor using extended information system success model. 2020 3rd International Conference on Mechanical, Electronics, Computer, and Industrial Technology (MECnIT) (pp. 370–375), Medan, Indonesia. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alba, P., & Rojas, A. (2020). Propuesta metodológica de preparación para la implementación de un ERP en PYMES. Available online: https://repository.udistrital.edu.co/bitstream/handle/11349/29834/AlbaPaolaRojasAndrea2020.pdf?sequence=2&isAllowed=y (accessed on 12 June 2024).

- Al-Fawaz, K., Al-Salti, Z., & Eldabi, T. (2008). Critical success factors in ERP implementation: A review. European and Mediterranean Conference on Information Systems. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Mudimigh, A., Zairi, M., & Al-Mashari, M. (2001). ERP software implementation: An integrative framework. European Journal of Information Systems, 10(4), 216–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsharari, N. M., Al-Shboul, M., & Alteneiji, S. (2020). Implementation of cloud ERP in the SME: Evidence from UAE. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 27(2), 299–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anaya, L., Flak, L., & Abushakra, A. (2023). Realizing sustainable value from ERP systems implementation. Sustainability, 15(7), 5783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archana, M., Varadarajan, D. V., & Medicherla, S. S. (2022). Study on the ERP implementation methodologies on SAP, oracle netsuite, and Microsoft dynamics 365: A review. arXiv, arXiv:2205.02584v2. [Google Scholar]

- Asprion, P. M., Schneider, B., & Grimberg, F. (2018). ERP systems towards digital transformation. In Studies in systems, decision and control (Vol. 141, pp. 15–29). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baki, C. B., Wellens, J., Traoré, F., Palé, S., Djaby, B., Bambara, A., Thao, N. T. T., Hié, M., & Tychon, B. (2022). Assessment of Hydro-Agricultural Infrastructures in Burkina Faso by Using Multiple Correspondence Analysis Approach. Sustainability, 14(20), 13303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal, R., & Jadan, D. (2020). Identificación y análisis de factores críticos de éxito en la implementación de sistemas ERP en Pymes: Caso provincia del Azuay. Available online: http://dspace.ucuenca.edu.ec/handle/123456789/33984 (accessed on 10 June 2024).

- Chabert, M. (2018). Constraint programming models for conceptual clustering: Application to an ERP configuration problem. Available online: https://theses.hal.science/tel-01963693 (accessed on 6 June 2024).

- Chen, C. C., Law, C., & Yang, S. C. (2009). Managing ERP implementation failure: A project management perspective. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 56(1), 157–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dezdar, S., & Ainin, S. (2011). The influence of organizational factors on successful ERP implementation. Management Decision, 49(6), 911–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Sawah, S., Abd El Fattah Tharwat, A., & Hassan Rasmy, M. (2008). A quantitative model to predict the Egyptian ERP implementation success index. Business Process Management Journal, 14(3), 288–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteves, J., & Pastor, J. (2000, November 1–2). Towards the unification of critical success factors for ERP implementations. 10th Annual Business Information Technology (BIT) 2000 Conference, Manchester, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Faizan, A., & Mehmood, A. (2022). The effect of ERP on supply chain management performance: An investigation of small to medium-sized enterprises in Pakistan. Journal for Business Education and Management, 2, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Françoise, O., Bourgault, M., & Pellerin, R. (2009). ERP implementation through critical success factors’ management. Business Process Management Journal, 15(3), 371–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fui-Hoon Nah, F., Lee-Shang Lau, J., & Kuang, J. (2001). Critical factors for successful implementation of enterprise systems. Business Process Management Journal, 7(3), 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gessa, A., Jiménez, A., & Sancha, P. (2023). Exploring ERP systems adoption in challenging times. Insights of SMEs stories. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 195, 122795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes Ferri, A. (2024). Sistemas ERP: Importancia, ventajas y desafíos de la implementación en las organizaciones. CERN (European Organization for Nuclear Research). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govea Souza, J. A. (2021). Sistema de planificación de recursos empresariales (ERP) y su influencia en los procesos de negocio de empresas distribuidoras de productos de consumo masivo en Lima Metropolitana en el 2019. Industrial Data, 24(1), 201–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandón, E. E., Ramírez-Correa, P. E., & Rojas, K. P. (2018). Uso de la teoría business process change (BPC) para examinar la adopción de enterprise resource planning (ERP) en Chile. Interciencia, 43(10), 716–722. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/docview/2123610087?sourcetype=Scholarly%20Journals (accessed on 10 June 2024).

- Greenacre, M. (2008). La práctica del análisis de correspondencias. Fundación BBVA. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood, B. N., Ganju, K. K., & Angst, C. M. (2019). How does the implementation of enterprise information systems affect a professional’s mobility? An empirical study. Information Systems Research, 30(2), 563–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero Luzuriaga, A., Marín Guamán, M., & Bonilla Jurado, D. (2018). ERP como alternativa de eficiencia en la gestión financiera de las empresas. Revista Lasallista de Investigación, 15(2), 182–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunasekaran, A., Patel, C., & Tirtiroglu, E. (2001). Performance measures and metrics in a supply chain environment. International Journal of Operations and Production Management, 21(1–2), 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddara, M. (2022). ERP systems selection in multinational enterprises: A practical guide. International Journal of Information Systems and Project Management, 6(1), 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harun, S., Dorasamy, M., & Ahmad, A. A. B. (2022). Effect of ERP implementation on organizational performance: Manager’s dilemma. International Journal of Technology, 13(5), 1064–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasibuan, Z., & Dantes, G. (2012). Priority of key success factors (KSFS) on enterprise resource planning (ERP) system implementation life cycle. Journal of Enterprise Resource Planning Studies, 2012, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juniawan, M. A., Ashari, N., Prastiti, R. T., Inayah, S., Gunawan, F., & Putra, P. H. (2022, July 27–28). Exploring critical success factors for enterprise resource planning implementation: A telecommunication company viewpoint. 2022 1st International Conference on Information System and Information Technology, ICISIT 2022 (pp. 1–6), Yogyakarta, Indonesia. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalling, T. (2003). ERP systems and the strategic management processes that lead to competitive advantage. Information Resources Management Journal, 16(4), 46–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Katerattanakul, P., Lee, J. J., & Hong, S. (2014). Effect of business characteristics and ERP implementation on business outcomes: An exploratory study of Korean manufacturing firms. Management Research Review, 37(2), 186–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, T. (2015). Geschäftsmodelle in Industrie 4.0 und dem Internet der dinge. Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kautsar, F., & Budi, I. (2020, September 7–8). Analysis of success factors in the implementation of ERP system in state owned enterprise case study PT. XYZ. 2020 6th International Conference on Science and Technology (ICST) (pp. 1–6), Yogyakarta, Indonesia. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodithuwakku, K., & Madhavika, N. (2023). Critical success factors of remote ERP implementation: From system users’ perspective. Global Journal of Computer Science and Technology Interdisciplinary Global Journal of Computer Science and Technology: G, 23(1), 27–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kronbichler, S. A., Ostermann, H., & Staudinger, R. (2009). A review of critical success factors for ERP-projects. The Open Information Systems Journal, 3(1), 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusumawardhana, R. H., Eitiveni, I., Yaziji, W., & Adriani, Z. A. (2024). Identifying critical success factors (CSF) in ERP implementation using AHP: A case study of a social insurance company in Indonesia. Journal of Cases on Information Technology, 26(1), 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara-Pérez, J. A., Canibe-Cruz, F., & Duréndez, A. (2024). How the interaction of innovation and ERP systems on business intelligence affects the performance of Mexican manufacturing companies. Information Technology and People, 38(3), 1403–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyh, C. (2014, August 7–9). Which factors influence ERP implementation projects in small and medium-sized enterprises? Americas Conference on Information Systems, Savannah, GA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X., Lowry, P. B., & Lai, F. (2024). The influence of ERP-vendor contract compliance and transaction-specific investment on vendee trust: A signaling theory perspective. Information and Management, 61(2), 103923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, T. C., & Koh, S. C. L. (2004). Critical elements for a successful enterprise resource planning implementation in small-and medium-sized enterprises. International Journal of Production Research, 42(17), 3433–3455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Rivas, S. L., Ayup González, J., & Méndez Wong, A. (2021). Marco TOE para diferenciar la asimilación del ERP en franquicias y empresas familiares mexicanas. Revistas Cuadernos de Trabajo de Estudios Regionales En Economía, Población y Desarrollo, 11(65), 3–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, M. O., & Khan, N. (2021). Analysis of ERP implementation to develop a strategy for its success in developing countries. Production Planning & Control, 32(12), 1020–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menz, M., Kunisch, S., Birkinshaw, J., Collis, D. J., Foss, N. J., Hoskisson, R. E., & Prescott, J. E. (2021). Corporate strategy and the theory of the firm in the digital age. Journal of Management Studies, 58(7), 1695–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milligan, G. W., & Cooper, M. C. (1987). Methodology review: Clustering methods. Applied Psychological Measurement, 11(4), 329–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mojena, R. (1977). Hierarchical grouping methods and stopping rules: An evaluation. The Computer Journal, 20(4), 359–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motwani, J., Subramanian, R., & Gopalakrishna, P. (2005). Critical factors for successful ERP implementation: Exploratory findings from four case studies. Computers in Industry, 56(6), 529–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagpal, S., Kumar, A., & Khatri, S. K. (2017). Modeling interrelationships between CSF in ERP implementations: Total ISM and MICMAC approach. International Journal of System Assurance Engineering and Management, 8(4), 782–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nah, F. F.-H., Zuckweiler, K. M., & Lee-Shang Lau, J. (2003). ERP implementation: Chief information officers’ perceptions of critical success factors. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, 16(1), 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikitović, M. (2012). Critical success factors aspects of the enterprise resource planning implementation. Journal of Information and Organizational Sciences, 36(2), 135–146. [Google Scholar]

- Noudoostbeni, A., Azina Ismail, N., Jenatabadi, H. S., & Mohd Yasin, N. (2010). An effective end-user knowledge concern training method in enterprise resource planning (ERP) based on Critical Factors (CFs) in Malaysian SMEs. International Journal of Business and Management, 5(7), 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panji Wicaksono, M. G., Aditya, I. E., Putra, P. E., Putu Angga Pranindhana, I. B., & Hadi Putra, P. O. (2022, September 13–14). Critical success factor analysis ERP project implementation using analytical hierarchy process in consumer goods company. 2022 5th International Conference of Computer and Informatics Engineering (IC2IE) (pp. 41–46), Jakarta, Indonesia. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pino, C., Felzensztein, C., & Chetty, S. (2021). Institutional knowledge in Latin American SMEs. Journal of Small Business Management, 59(4), 648–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raharjo, S. T., & Perdhana, M. S. (2015, August 13–14). SMEs competitive advantage and enterprise resource planning implementation: Finding from central Java. International Conference on Entrepreneurship, Business and Social Science, Yogyakarta, Indonesia. [Google Scholar]

- Rahayu, S., & Juliana Dillak, V. (2018). Key success factor for successful ERP implementation in state owned enterprises. International Journal of Engineering & Technology, 4(38), 916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjan, S., Jha, V. K., & Pal, P. (2018). Critical success factors in ERP implementation in Indian manufacturing enterprises: An exploratory analysis. International Journal of Business Information Systems, 28(4), 404–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reel, J. S. (1999). Critical success factors in software projects. IEEE Software, 16(3), 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remus, U. (2007). Critical success factors for implementing enterprise portals: A comparison with ERP implementations. Business Process Management Journal, 13(4), 538–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribbers, P. M. A., & Schoo, K.-C. (2002). Program management and complexity of ERP implementations. Engineering Management Journal, 14(2), 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, A., Vargas, R., & Bohorquez, L. (2018). Implementation of enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems in organizations since coevolution. Solidar, 14(24), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez Aldana, M. L., & Fong Reynoso, C. (2020). Análisis bibliométrico de los factores críticos de éxito para la gestión estratégica de las PyMES. Nova Scientia, 12(24), 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saade, R. G., & Nijher, H. (2016). Critical success factors in enterprise resource planning implementation: A review of case studies. Journal of Enterprise Information Management, 29(1), 72–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, S., Nigam, S., & Misra, S. C. (2013). Identifying success factors for implementation of ERP at Indian SMEs: A comparative study with Indian large organizations and the global trend. Journal of Modelling in Management, 8(1), 103–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schniederjans, D., & Yadav, S. (2014). Successful ERP implementation: An integrative model. Business Process Management Journal, 19, 364–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J. E. (2000). Implementing enterprise resource planning systems: The role of learning from failure. Information Systems Frontiers, 2(2), 213–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaul, L., & Tauber, D. (2013). Critical success factors in enterprise resource planning systems. ACM Computing Surveys (CSUR), 45(4), 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somers, T. M., & Nelson, K. G. (2004). A taxonomy of players and activities across the ERP project life cycle. Information & Management, 41(3), 257–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syaifuddin, N. M., Zaini, A., Suriansyah, M., & Widodo, A. P. (2024). Saran implementasi sistem ERP berdasarkan keuntungan dan tantangan: Literature review: Suggestions for ERP system implementation based on benefits and challenges: Literature review. Technomedia Journal, 8(3), 434–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velastegui, L. (2021). Enterprise resource planning (ERP) effect on organizational management and user satisfaction in Riobamba, Ecuador. Available online: https://www.scielo.cl/scielo.php?pid=S0718-07642021000500101&script=sci_arttext (accessed on 2 April 2024).

- Vera, Á. B. (2006). Implementación de sistemas ERP, su impacto en la gestión de la empresa e integración con otras TIC. Capic Review, 4, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Vicedo, P., Gil, H., Oltra-Badenes, R., & Merigó, J. M. (2020). Critical success factors on ERP implementations: A bibliometric analysis. In J. C. Ferrer-Comalat, S. Linares-Mustarós, J. M. Merigó, & J. Kacprzyk (Eds.), Modelling and simulation in management sciences (pp. 169–181). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrecl, N., & Sternad Zabukovšek, S. (2022, May 16–20). Issues of the implementation of ERP in manufacturing companies. 6th FEB International Scientific Conference: Challenges in Economics and Business in the Post-COVID Times (pp. 343–352), Maribor, Slovenia. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendt, M. C., & Weinrich, R. (2023). Consumer segmentation for pesticide-free food products in Germany. Sustainable Production and Consumption, 42, 309–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y., Allen, C., & Ali, M. (2022). Critical success factor based resource allocation in ERP implementation: A nonlinear programming model. Heliyon, 8(8), e10044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabala, R. M., Granja, L. G., Calderón, H. A., & Velasteguí, L. E. (2021). Efecto en la gestión organizacional y la satisfacción de los usuarios de un sistema informático de planificación de recursos empresariales (ERP) en Riobamba, Ecuador. Información Tecnológica, 32(5), 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamzeer, M., Alshamaileh, Y., Alsawalqah, H. I., Hassan, M. A., Fannas, E. J. A., & Almubideen, S. S. (2020). Determinants of cloud ERP adoption in Jordan: An exploratory study. International Journal of Business Information Systems, 34(2), 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y., Xu, G., Minshall, T., & Liu, P. (2015). How do public demonstration projects promote green-manufacturing technologies? A case study from China. Sustainable Development, 23(4), 217–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Description |

|---|---|

| x1 | Support and involvement of top management |

| x2 | Project management |

| x3 | User training |

| x4 | Change management |

| x5 | Balanced project team |

| x6 | Communication |

| x7 | Clear goals and objectives |

| x8 | Business process re-engineering (BPR) |

| x9 | ERP organizational fit |

| x10 | End user and stakeholder involvement |

| x11 | External consultants |

| x12 | ERP system configuration |

| x13 | Relationship with vendors and support |

| x14 | IT structure and legacy systems |

| x15 | Project champion (mediator) |

| x16 | Skills, knowledge, and experience |

| x17 | Project team leadership/empowered decision-makers |

| x18 | Available resources |

| x19 | Monitoring/performance measurement |

| x20 | ERP system acceptance/resistance |

| x21 | Vendor tools and implementation methods |

| x22 | Data accuracy |

| x23 | Organizational culture |

| x24 | ERP system testing |

| x25 | Environment (national culture and language) |

| x26 | Problem-solving |

| x27 | Organizational structure |

| x28 | Interdepartmental cooperation |

| x29 | Knowledge management |

| x30 | Company strategy/adjustment strategy |

| x31 | Use of steering committee |

| Method | Dunn’s Indicator |

|---|---|

| Hierarchical | 0.5372 |

| CLARA | 0.2040 |

| PAM | 0.2040 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Llivisaca-Villazhañay, J.; Flores-Siguenza, P.; Guamán, R.; Urdiales, C.; Gento-Municio, Á.M. Key Drivers of ERP Implementation in Digital Transformation: Evidence from Austro-Ecuadorian. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 196. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15060196

Llivisaca-Villazhañay J, Flores-Siguenza P, Guamán R, Urdiales C, Gento-Municio ÁM. Key Drivers of ERP Implementation in Digital Transformation: Evidence from Austro-Ecuadorian. Administrative Sciences. 2025; 15(6):196. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15060196

Chicago/Turabian StyleLlivisaca-Villazhañay, Juan, Pablo Flores-Siguenza, Rodrigo Guamán, Cristian Urdiales, and Ángel M. Gento-Municio. 2025. "Key Drivers of ERP Implementation in Digital Transformation: Evidence from Austro-Ecuadorian" Administrative Sciences 15, no. 6: 196. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15060196

APA StyleLlivisaca-Villazhañay, J., Flores-Siguenza, P., Guamán, R., Urdiales, C., & Gento-Municio, Á. M. (2025). Key Drivers of ERP Implementation in Digital Transformation: Evidence from Austro-Ecuadorian. Administrative Sciences, 15(6), 196. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15060196