Greening Sustainable Supply Chain Performance: The Moderating and Mediating Influence of Green Value Co-Creation and Green Innovation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Natural Resource-Based View (NRBV)

2.2. Green Innovation (GInv)

2.3. Green Supply Chain Integration (GSCI)

2.4. Green Value Co-Creation (GVCc)

2.5. Sustainable Supply Chain Performance

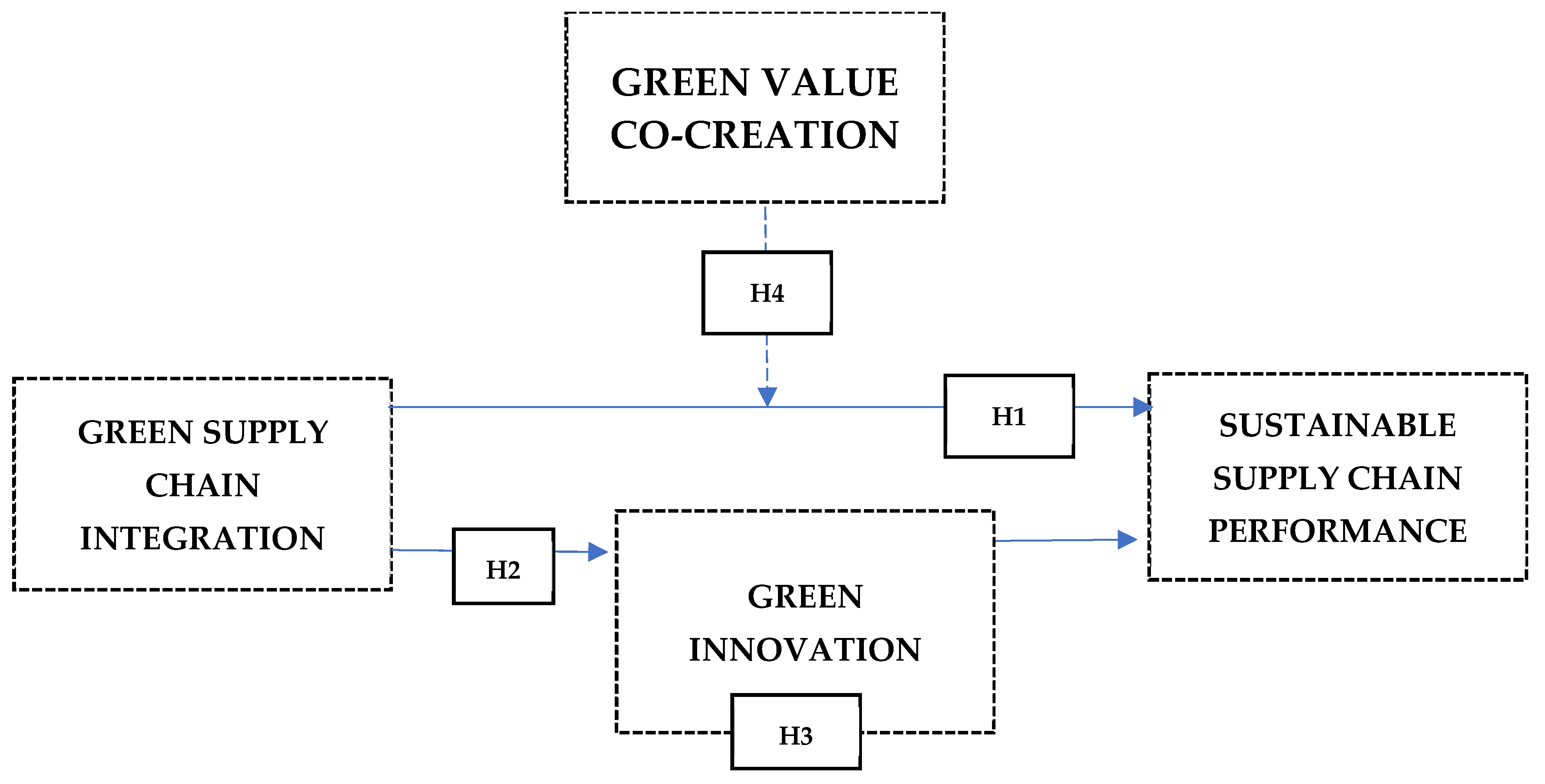

2.6. Green Supply Chain Integration and Sustainable Supply Chain Performance

2.7. Green Supply Chain Integration, Green Innovation, and Sustainable Supply Chain Performance

2.8. Moderating Role of Green Value Co-Creation

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. The Participants and Sampling Procedures

3.2. Ethical Considerations

3.3. Measures and Analysis

4. Results

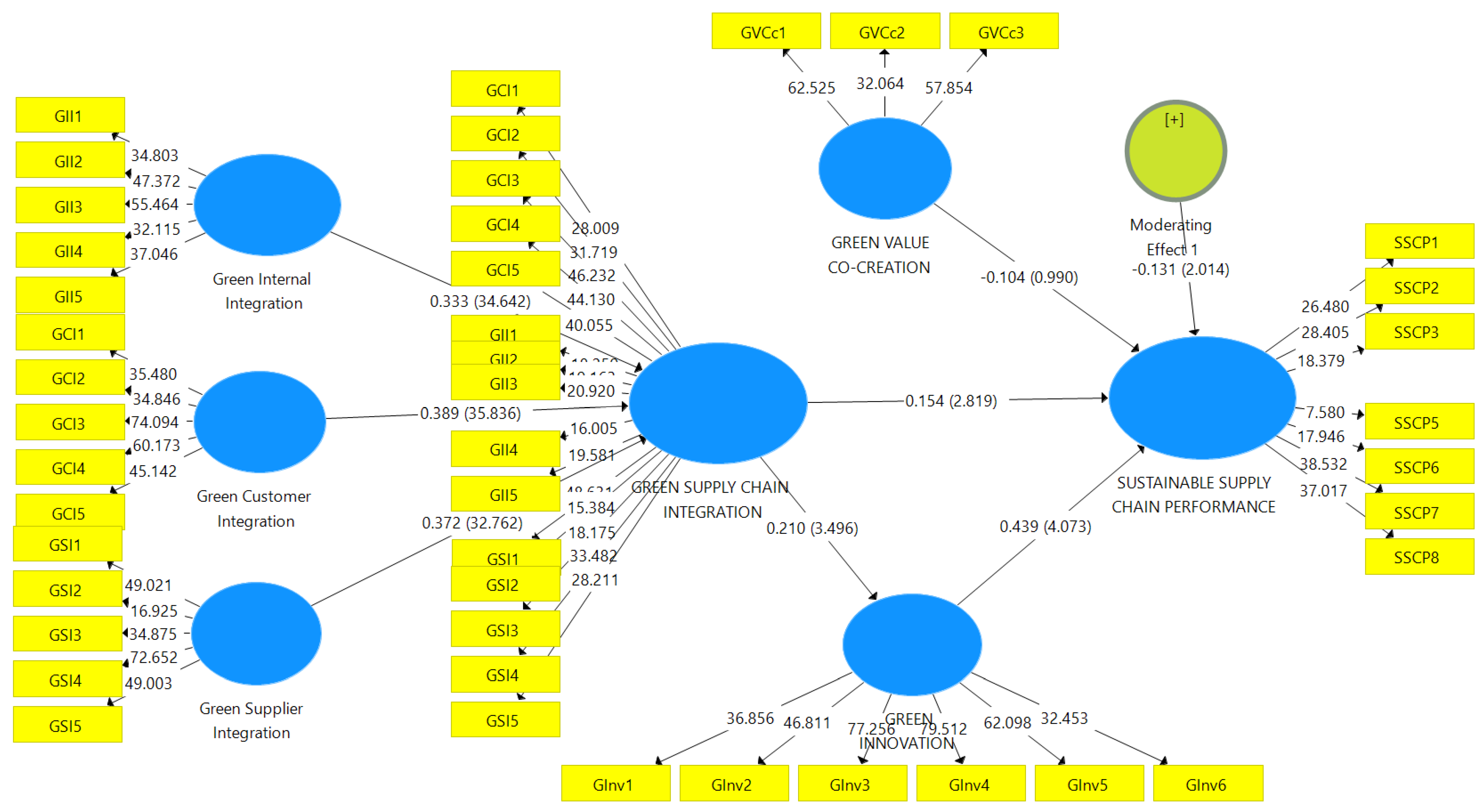

Structural Model Evaluation

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Measurement Items

Appendix A.1. Green Supply Chain Integration (GSCI)

- Green internal integration.

- GII1:

- Cross-functional cooperation for environmental improvements.

- GII2:

- Environmental issues are well communicated among departments.

- GII3:

- Environmental knowledge is accumulated and shared across departments.

- GII4:

- An environmental management system exists.

- Green customer integration

- GCI1:

- Achieving environmental goals through joint planning with major customers.

- GCI2:

- Cooperating with major customers to reduce the environmental impact of our products.

- GCI3:

- Cooperating with major customers for cleaner production, green packaging, or other environmental activities.

- GCI4:

- Collaborating with major customers to implement the environmental management system.

- GCI5:

- Implementing environmental audit for major customers’ internal management.

- Green supplier integration

- GSI1:

- Collaborating with a major supplier to set up environmental goals.

- GSI2:

- Implementing environmental audit for major supplier’s internal management.

- GSI3:

- Providing major suppliers with environmental design requirements related to design specifications and cleaner production technology.

- GSI4:

- Requiring major suppliers to implement environmental management or obtain third-party certification of environmental management system.

- GSI5:

- Selecting suppliers according to environmental criteria.

Appendix A.2. Green Value Co-Creation (GVCc)

- Our organization facilitates the customer deciding how they want to receive the service/product offering.

- The customer has many options to choose how they experience the service/product offering.

- It is easy for the customer to receive the service/product offering when, where, and how they wants it.

Appendix A.3. Green Innovation (GInv)

- Our organization chooses the materials of the product that produce the least amount of pollution for conducting the product development or design.

- Our organization uses the least amount of materials to comprise the product for conducting the product development or design.

- Our organization would circumspectly deliberate whether the product is easy to recycle, reuse, and decompose for conducting the product development or design.

- The manufacturing process of the organization reduces the consumption of water, electricity, coal, or oil.

- The manufacturing process of the organization effectively reduces the emission of hazardous substances or waste.

- The manufacturing process of the organization reduces the use of raw material.

Appendix A.4. Sustainable Supply Chain Performance (SSCP)

- Our organization has visibility of supply chain dynamics in the network.

- Risks in the supply network are managed proactively by our organization.

- Our organization has proper control over supply chain costs.

- Wastages in our supply chain network have been reduced significantly.

- Our organization’s primary supply chain can supply final customers with timely complete orders.

- Our organization can adhere to environmental standards as per customer requirement.

- Our organization has minimized buffer stocks at all levels throughout the supply chain.

- Our organization’s supply chain can respond faster than competitors in a volatile business environment.

References

- Abbas, A., Luo, X., Wattoo, M. U., & Hu, R. (2022). Organizational behavior in green supply chain integration: Nexus between information technology capability, green innovation, and organizational performance. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 874639. [Google Scholar]

- Afum, E., Osei-Ahenkan, V. Y., Agyabeng-Mensah, Y., Amponsah Owusu, J., Kusi, L. Y., & Ankomah, J. (2020). Green manufacturing practices and sustainable performance among Ghanaian manufacturing SMEs: The explanatory link of green supply chain integration. Management of Environmental Quality: An International Journal, 31(6), 1457–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albinsson, P. A., Perera, B. Y., & Sautter, P. T. (2016). DART scale development: Diagnosing a firm’s readiness for strategic value co-creation. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 24(1), 42–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appannan, J. S., Said, R. M., & Senik, R. (2020). Environmental proactivity on environmental performance: An extension of natural resource-based view theory (NRBV). International Journal of Industrial Management, 5, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arfi, W. B., Hikkerova, L., & Sahut, J. M. (2018). External knowledge sources, green innovation, and performance. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 129, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aribaba, F. O., Ahmodu, O. A., Olaleye, B. R., & Yusuff, S. A. (2019). Ownership structure and organizational performance in selected listed manufacturing companies, Nigeria. Journal of Business Studies and Management Review, 3(1), 9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Astrachan, C. B., Patel, V. K., & Wanzenried, G. (2014). A comparative study of CBSEM and PLS-SEM for theory development in family firm research. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 5(1), 116–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydiner, A. S., Acar, M. F., Zaim, S., & Delen, D. (2020). Supply chain orientation, ERP usage, and knowledge management in supply chain. In International symposium for production research 2019 (pp. 580–590). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Bag, S., Wood, L. C., Xu, L., Dhamija, P., & Kayikci, Y. (2020). Big data analytics as an operational excellence approach to enhance sustainable supply chain performance. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 153, 104559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, S. (1991). Environmental regulation for competitive advantage. Business Strategy Review, 2(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, B., & Batt, P. J. (2014). Re-assessing value (co)-creation and cooperative advantage in international networks. Industrial Marketing Management, 43, 538–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J., Cheng, J., Shi, H., & Feng, T. (2020). The impact of organizational conflict on green supplier integration: The moderating role of governance mechanism. International Journal of Logistics Research and Applications, 25, 143–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cepeda-Carrion, G., Cegarra-Navarro, J. G., & Cillo, V. (2019). Tips to use partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) in knowledge management. Journal of Knowledge Management, 23(1), 67–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y., Chang, S., Choi, J., & Seong, Y. (2018). The partnership network scopes of social enterprises and their social value creation. International Journal of Entrepreneurship, 22(1), 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Dangelico, R. M. (2016). Green product innovation: Where we are and where we are going. Business Strategy and the Environment, 25, 560–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, L., Zhang, Z., & Feng, T. (2018). Linking green customer and supplier integration with green innovation performance: The role of internal integration. Business Strategy and the Environment, 27, 1583–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Effendi, M. I., Widjanarko, H., & Sugandini, D. (2021). Green supply chain integration and technology innovation performance in SMEs: A case study in Indonesia. The Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business, 8, 909–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Kassar, A. N., & Singh, S. K. (2019). Green innovation and organizational performance: The influence of big data and the moderating role of management commitment and HR practices. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 144, 483–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauzi, M. A. (2022). Partial least square structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM) in knowledge management studies: Knowledge sharing in virtual communities. Knowledge Management & E-Learning, 14(1), 103–124. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golicic, S. L., & Smith, C. D. (2013). A meta-analysis of environmentally sustainable supply chain management practices and firm performance. Journal of Supply Chain Management, 49(2), 78–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, K. W., Zelbst, P. J., Meacham, J., & Bhadauria, V. S. (2012). Green supply chain management practices: Impact on performance. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, 17, 290–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gummesson, E., Nenonen, S., & Storbacka, K. (2010). Business model design: Conceptualizing networked value co-creation. International Journal of Quality and Service Sciences, 2, 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunasekaran, A., Subramanian, N., & Rahman, S. (2017). Improving supply chain performance through management capabilities. Production Planning & Control, 28(6–8), 473–477. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J. F., Jr., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., Sarstedt, M., Danks, N. P., & Ray, S. (2021). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) using R: A workbook. Springer Nature. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Z., & Huo, B. (2020). The impact of green supply chain integration on sustainable performance. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 120(4), 657–674. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, S. L. (1995). A natural-resource-based view of the firm. Academy of Management Review, 20(4), 986–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J. W., & Li, Y. H. (2017). Green innovation and performance: The view of organizational capability and social reciprocity. Journal of Business Ethics, 145, 309–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein Zolait, A., Razak Ibrahim, A., Chandran, V. G. R., & Pandiyan Kaliani Sundram, V. (2010). Supply chain integration: An empirical study on manufacturing industry in Malaysia. Journal of Systems and Information Technology, 12(3), 210–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jawaad, M., & Zafar, S. (2020). Improving sustainable development and firm performance in emerging economies by implementing green supply chain activities. Sustainable Development, 28(1), 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamalahmadi, M., & Parast, M. M. (2016). A review of the literature on the principles of enterprise and supply chain resilience: Major findings and directions for future research. International Journal of Production Economics, 171, 116–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M. (2018). Supply chain integration and its impact on sustainability. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 118(9), 1749–1765. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, T., Feng, T., Huang, Y., & Cai, J. (2020). How to convert green supply chain integration efforts into green innovation: A perspective of knowledge-based view. Sustainable Development, 28, 1106–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, T., Feng, T., & Huo, B. (2021). Green supply chain integration and financial performance: A social contagion and information sharing perspective. Business Strategy and the Environment, 30(5), 2255–2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T. T., Nhu, Q. P. V., Bao, T. B. N., Thao, L. V. N., & Pereira, V. (2024). Digitalisation driving sustainable corporate performance: The mediation of green innovation and green supply chain management. Journal of Cleaner Production, 446, 141290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S., Jayaraman, V., Paulraj, A., & Shang, K. C. (2016). Proactive environmental strategies and performance: Role of green supply chain processes and green product design in the Chinese high-tech industry. International Journal of Production Research, 54(7), 2136–2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S., Qiao, J., Cui, H., & Wang, S. (2020). Realizing the environmental benefits of proactive environmental strategy: The roles of green supply chain integration and relational capability. Sustainability, 12, 2907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y. H., & Chen, Y. S. (2017). Determinants of green competitive advantage: The roles of green knowledge sharing, green dynamic capabilities, and green service innovation. Quality & Quantity, 51, 1663–1685. [Google Scholar]

- Lo, S. M. (2015). Impact of greening attitude and buyer power on supplier environmental management strategy. International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology, 12, 3145–3160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, S. M., & Shiah, Y. A. (2016). Associating the motivation with the practices of firms going green: The moderator role of environmental uncertainty. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, 21(4), 485–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, S. M., Zhang, S., Wang, Z., & Zhao, X. (2018). The impact of relationship quality and supplier development on green supply chain integration: A mediation and moderation analysis. Journal of Cleaner Production, 202, 524–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z., Shu, G., Wang, Q., & Wang, L. (2022). Sustainable governance and green innovation: A perspective from gender diversity in China’s listed companies. Sustainability, 14(11), 6403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, S. Y., Cao, Y., Mughal, Y. H., Kundi, G. M., Mughal, M. H., & Ramayah, T. (2020). Pathways towards sustainability in organizations: Empirical evidence on the role of green human resource management practices and green intellectual capital. Sustainability, 12(8), 3228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Z., Li, X., & Zhang, S. (2017). Low carbon supply chain firm integration and firm performance in China. Journal of Cleaner Production, 153, 354–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathivathanan, D., Govindan, K., & Haq, A. N. (2017). Exploring the impact of dynamic capabilities on sustainable supply chain firm’s performance using Grey-Analytical Hierarchy Process. Journal of Cleaner Production, 147, 637–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDougall, N. (2018). Explicating natural-resource-based view capabilities: A dynamic framework for innovative sustainable supply chain management in UK agri-food [Doctoral dissertation, University of Strathclyde]. [Google Scholar]

- Melander, L., & Pazirandeh, A. (2019). Collaboration beyond the supply network for green innovation: Insight from 11 cases. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, 24(4), 509–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, P., & Yadav, M. (2021). Environmental capabilities, proactive environmental strategy, and competitive advantage: A natural-resource-based view of firms operating in India. Journal of Cleaner Production, 291, 125249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murfield, M. L., & Tate, W. L. (2017). Buyer and supplier perspectives on environmental initiatives: Potential implications for supply chain relationships. The International Journal of Logistics Management, 28(4), 1319–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novitasari, M., & Agustia, D. (2023). Competitive advantage as a mediating effect in the impact of green innovation and firm performance. Business: Theory and Practice, 24(1), 216–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurmilaakso, J. M. (2008). Adoption of e-business functions and migration from EDI-based to XML-based e-business frameworks in supply chain integration. International Journal of Production Economics, 113(2), 721–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaleye, B. R. (2023). Influence of eco-product innovation and firm reputation on corporate social responsibility and competitive advantage: A mediation-moderation analysis. Journal of Public Affairs, 23(4), e2878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaleye, B. R., Abdurrashid, I., & Mustapha, B. (2023). Organizational sustainability and TQM practices in hospitality industry: Employee-employer perception. The TQM Journal, 36(7), 1936–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaleye, B. R., Fapetu, O., Asaolu, A. A., & Bojuwon, M. (2021). Nexus between authentic leadership, organizational culture, and job performance: Mediating role of bullying. FUOYE Journal of Finance and Contemporary Issues, 1(1), 38–48. [Google Scholar]

- Olaleye, B. R., Lekunze, J. N., & Sekhampu, T. J. (2024). Examining structural relationships between innovation capability, knowledge sharing, environmental turbulence, and organizational sustainability. Cogent Business & Management, 11(1), 2393738. [Google Scholar]

- Omara, H. A. M. B. B., Alia, M. A., & Bin, A. A. (2019). Green supply chain integrations and corporate sustainability. Uncertain Supply Chain Management, 7, 713–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulraj, A., Chen, I. J., & Blome, C. (2017). Motives and performance outcomes of sustainable supply chain management practices: A multi-theoretical perspective. Journal of Business Ethics, 145, 239–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjan, K. R., & Read, S. (2016). Value co-creation: Concept and measurement. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 44, 290–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqi, R. A., Codini, A. P., Ishaq, M. I., Jamali, D. R., & Raza, A. (2025). Sustainable supply chain, dynamic capabilities, eco-innovation, and environmental performance in an emerging economy. Business Strategy and the Environment, 34(1), 338–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, W. H., Guarnieri, P., Carvalho, J. M., Farias, J. S., & Reis, S. A. D. (2019). Sustainable supply chain management: Analyzing the past to determine a research agenda. Logistics, 3(2), 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soewarno, N., Tjahjadi, B., & Fithrianti, F. (2019). Green innovation strategy and green innovation: The roles of green organizational identity and environmental organizational legitimacy. Management Decision, 57(11), 3061–3078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W., & Yu, H. (2018). Green innovation strategy and green innovation: The roles of green creativity and green organizational identity. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 25(2), 135–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y., Cai, J., & Feng, T. (2017). The influence of green supply chain integration on firm performance: A contingency and configuration perspective. Sustainability, 9(5), 763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suheil, C. S. (2015). The relationship between green supply chain integration and sustainable performance [Doctoral dissertation, Universiti Utara Malaysia]. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, M., Walsh, G., Lerner, D., Fitza, M. A., & Li, Q. (2018). Green innovation, managerial concern, and firm performance: An empirical study. Business Strategy and the Environment, 27(1), 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tantayanubutr, M., & Panjakajornsak, V. (2017). Impact of green innovation on the sustainable performance of Thai food industry. Business and Economic Horizons, 13(2), 192–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, A., Badir, Y., & Chonglerttham, S. (2019). Green innovation and performance: Moderation analyses from Thailand. European Journal of Innovation Management, 22(3), 446–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walley, N., & Whitehead, B. (1994). It’s not easy being green. Reader in Business and the Environment, 36(81), 4. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C. H. (2019). How organizational green culture influences green performance and competitive advantage: The mediating role of green innovation. Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management, 30, 666–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, J. (2011). Sustainable supply chain management integration: A qualitative analysis of the German manufacturing industry. Journal of Business Ethics, 102, 221–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C. W. Y., Lai, K., Shang, K. C., Lu, C. S., & Leung, T. (2012). Green operations and the moderating role of environmental management capability of suppliers on manufacturing firm performance. International Journal of Production Economics, 140(1), 283–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C. W. Y., Wong, C. Y., & Boon-itt, S. (2018). How does sustainable development of supply chains make firms lean, green, and profitable? A resource orchestration perspective. Business Strategy and the Environment, 27(3), 375–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C. Y., Wong, C. W. Y., & Boon-itt, S. (2020). Effects of green supply chain integration and green innovation on environmental and cost performance. International Journal of Production Research, 58(15), 4589–4609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G. C. (2013). The influence of green supply chain integration and environmental uncertainty on green innovation in Taiwan’s IT industry. Supply Chain Management: International Journal, 18, 539–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F., Yuan, H., & Yi, N. (2022). Natural resources, environment and the sustainable development. Urban Climate, 42, 101111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiz Çankaya, S., & Sezen, B. (2019). Effects of green supply chain management practices on sustainability performance. Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management, 30(1), 98–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousaf, Z. (2021). Go for green: Green innovation through green dynamic capabilities: Accessing the mediating role of green practices and green value co-creation. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 28(39), 54863–54875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W., Chavez, R., Feng, M., & Wiengarten, F. (2014). Integrated green supply chain management and operational performance. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, 19(5/6), 683–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W., Jacobs, M. A., Salisbury, W. D., & Enns, H. (2013). The effects of supply chain integration on customer satisfaction and financial performance: An organizational learning perspective. International Journal of Production Economics, 146, 346–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaid, A. A., Jaaron, A. A., & Bon, A. T. (2018). The impact of green human resource management and green supply chain management practices on sustainable performance: An empirical study. Journal of Cleaner Production, 204, 965–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B., Zhao, S., Fan, X., Wang, S., & Shao, D. (2022). Green supply chain integration, supply chain agility and green innovation performance: Evidence from Chinese manufacturing enterprises. Frontiers in Environmental Science, 10, 1045414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H., & Yang, F. (2016). On the drivers and performance outcomes of green practices adoption an empirical study in China. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 116(9), 2011–2034. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, L., Li, L., Song, Y., Li, C., & Wu, Y. (2018). Research on pricing and coordination strategy of a sustainable green supply chain with a capital-constrained retailer. Complexity, 2018(1), 6845970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C., Xia, W., Feng, T., Jiang, J., & He, Q. (2020). How environmental orientation influences firm performance: The missing link of green supply chain integration. Sustainable Development, 28(4), 685–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q., Sarkis, J., & Lai, K. H. (2012). Examining the effects of green supply chain management practices and their mediations on performance improvements. International Journal of Production Research, 50(5), 1377–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Measures | Items | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 198 | 62.5 |

| Female | 119 | 37.5 | |

| Age | 18–30 | 29 | 9.1 |

| 31–40 | 68 | 21.5 | |

| 41–50 | 121 | 38.2 | |

| 50 and above | 99 | 31.2 | |

| Education | Diploma | 91 | 28.7 |

| University degree | 194 | 61.2 | |

| Postgraduate degree | 32 | 10.1 | |

| Job Tenure | Less than a year | 24 | 7.6 |

| 1–3 years | 40 | 12.6 | |

| 4–6 years | 147 | 46.4 | |

| Over 6 years | 106 | 33.4 |

| Latent Variables | Loadings (λ) | CA | rho_A | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GREEN INNOVATION | GInv | 0.949 | 0.954 | 0.959 | 0.798 |

| GInv1 | 0.865 *** | ||||

| GInv2 | 0.894 *** | ||||

| GInv3 | 0.926 *** | ||||

| GInv4 | 0.925 *** | ||||

| GInv5 | 0.899 *** | ||||

| GInv6 | 0.848 *** | ||||

| GREEN SUPPLY CHAIN INTEGRATION | GSCI | 0.956 | 0.958 | 0.961 | 0.623 |

| Green Internal Integration | GII | 0.905 | 0.907 | 0.930 | 0.725 |

| GI1 | 0.837 *** | ||||

| GI2 | 0.869 *** | ||||

| GI3 | 0.890 *** | ||||

| GI4 | 0.826 *** | ||||

| GI5 | 0.835 *** | ||||

| Green Customer Integration | GCI | 0.926 | 0.928 | 0.944 | 0.773 |

| GCI1 | 0.818 *** | ||||

| GCI2 | 0.869 *** | ||||

| GCI3 | 0.920 *** | ||||

| GCI4 | 0.902 *** | ||||

| GCI5 | 0.883 *** | ||||

| Green Supplier Integration | GCI | 0.914 | 0.919 | 0.936 | 0.746 |

| GSI1 | 0.874 *** | ||||

| GSI2 | 0.750 *** | ||||

| GSI3 | 0.884 *** | ||||

| GSI4 | 0.912 *** | ||||

| GSI5 | 0.889 *** | ||||

| GREEN VALUE CO-CREATION | GVCc | 0.908 | 0.939 | 0.941 | 0.842 |

| GVCc1 | 0.940 *** | ||||

| GVCc2 | 0.892 *** | ||||

| GVCc3 | 0.920 *** | ||||

| SUSTAINABLE SUPPLY CHAIN PERFORMANCE | SSCP | 0.938 | 0.943 | 0.950 | 0.733 |

| SSCP1 | 0.918 *** | ||||

| SSCP2 | 0.900 *** | ||||

| SSCP3 | 0.854 *** | ||||

| SSCP4 | - | ||||

| SSCP5 | 0.727 *** | ||||

| SSCP6 | 0.765 *** | ||||

| SSCP7 | 0.901 *** | ||||

| SSCP8 | 0.908 *** |

| Constructs | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Green Innovation (GInv) | 0.893 | |||

| 2. Green Supply Chain Integration (GSCI) | 0.210 | 0.789 | ||

| 3. Green Value Co-creation (GVCc) | 0.809 | 0.199 | 0.917 | |

| 4. Sustainable Supply Chain Performance (SSCP) | 0.404 | 0.210 | 0.300 | 0.856 |

| Constructs | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Green Innovation (GInv) | ||||

| 2. Green Supply Chain Integration (GSCI) | 0.220 | |||

| 3. Green Value Co-creation (GVCc) | 0.880 | 0.211 | ||

| 4. Sustainable Supply Chain Performance (SSCP) | 0.421 | 0.220 | 0.312 |

| Parameters | β | SE | t-Value | p-Value | R2 | F2 | Decision | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct effects | ||||||||

| H1 | GSCI → SSCP | 0.154 | 0.055 | 2.819 | 0.005 | 0.202 | 0.028 | S |

| H2 | GSCI → GInv | 0.210 | 0.060 | 3.496 | 0.001 | 0.344 | 0.046 | S |

| Indirect effects | ||||||||

| H3 | GSCI → GInv → SSCP | 0.092 | 0.037 | 2.480 | 0.013 | PM | S | |

| H4 | GVCc _MOD_GSCI → SSCP | −0.131 | 0.065 | 2.014 | 0.045 | 0.026 | S | |

| Path | 95% Confidence Interval | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indirect Effect | SE | Lower | Upper | Direct Effect | |

| GSCI → GInv → SSCP | 0.092 | 0.037 | 0.058 | 0.266 | 0.246 *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Olaleye, B.R.; Mosleh, S.F. Greening Sustainable Supply Chain Performance: The Moderating and Mediating Influence of Green Value Co-Creation and Green Innovation. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 183. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15050183

Olaleye BR, Mosleh SF. Greening Sustainable Supply Chain Performance: The Moderating and Mediating Influence of Green Value Co-Creation and Green Innovation. Administrative Sciences. 2025; 15(5):183. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15050183

Chicago/Turabian StyleOlaleye, Banji Rildwan, and Sara Faysal Mosleh. 2025. "Greening Sustainable Supply Chain Performance: The Moderating and Mediating Influence of Green Value Co-Creation and Green Innovation" Administrative Sciences 15, no. 5: 183. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15050183

APA StyleOlaleye, B. R., & Mosleh, S. F. (2025). Greening Sustainable Supply Chain Performance: The Moderating and Mediating Influence of Green Value Co-Creation and Green Innovation. Administrative Sciences, 15(5), 183. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15050183