User Experience Dimensions in Digital Peer-to-Peer Platforms: A Grounded Theory Study of Airbnb Online Experiences

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

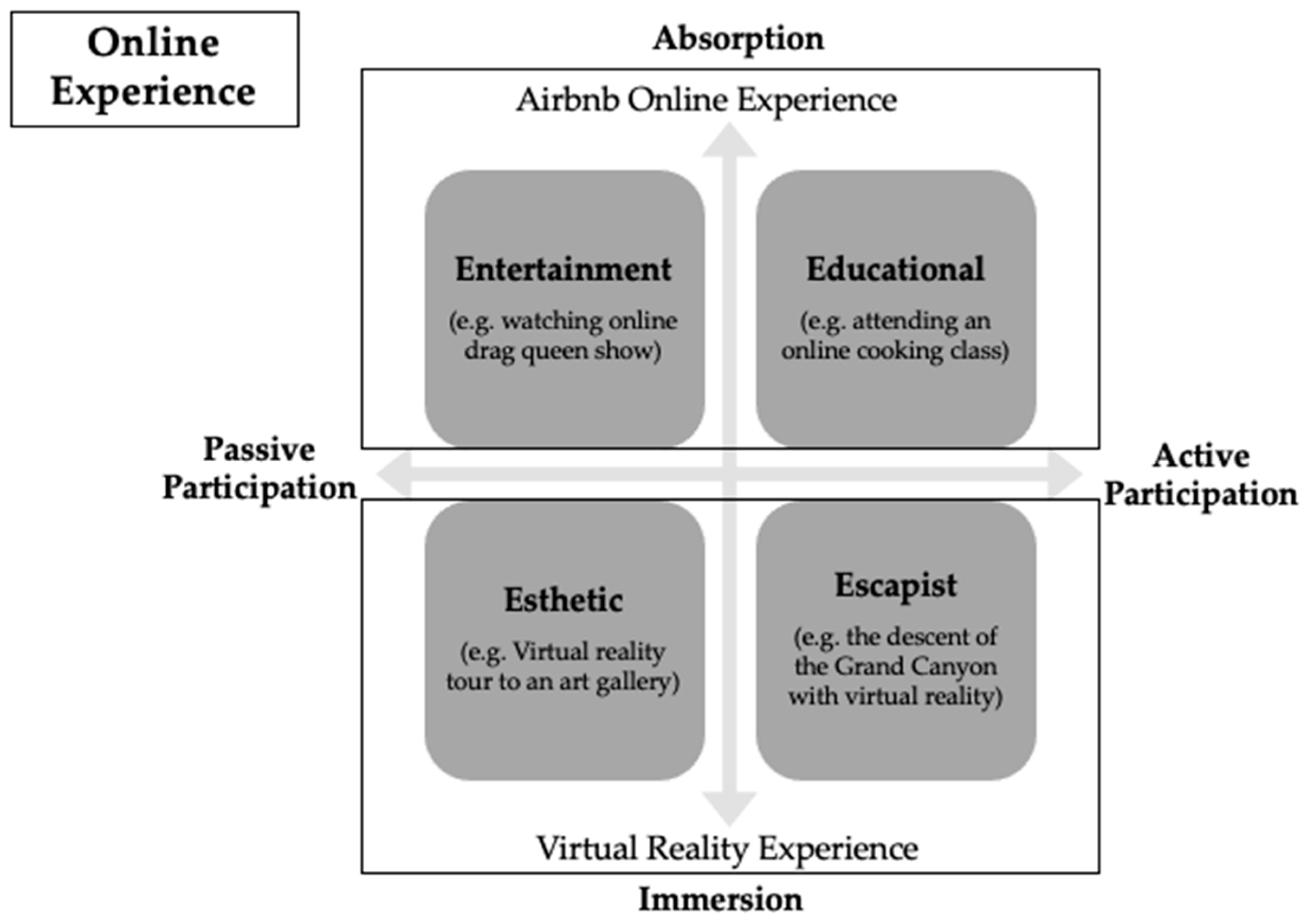

2.1. The Realms of Online Experience

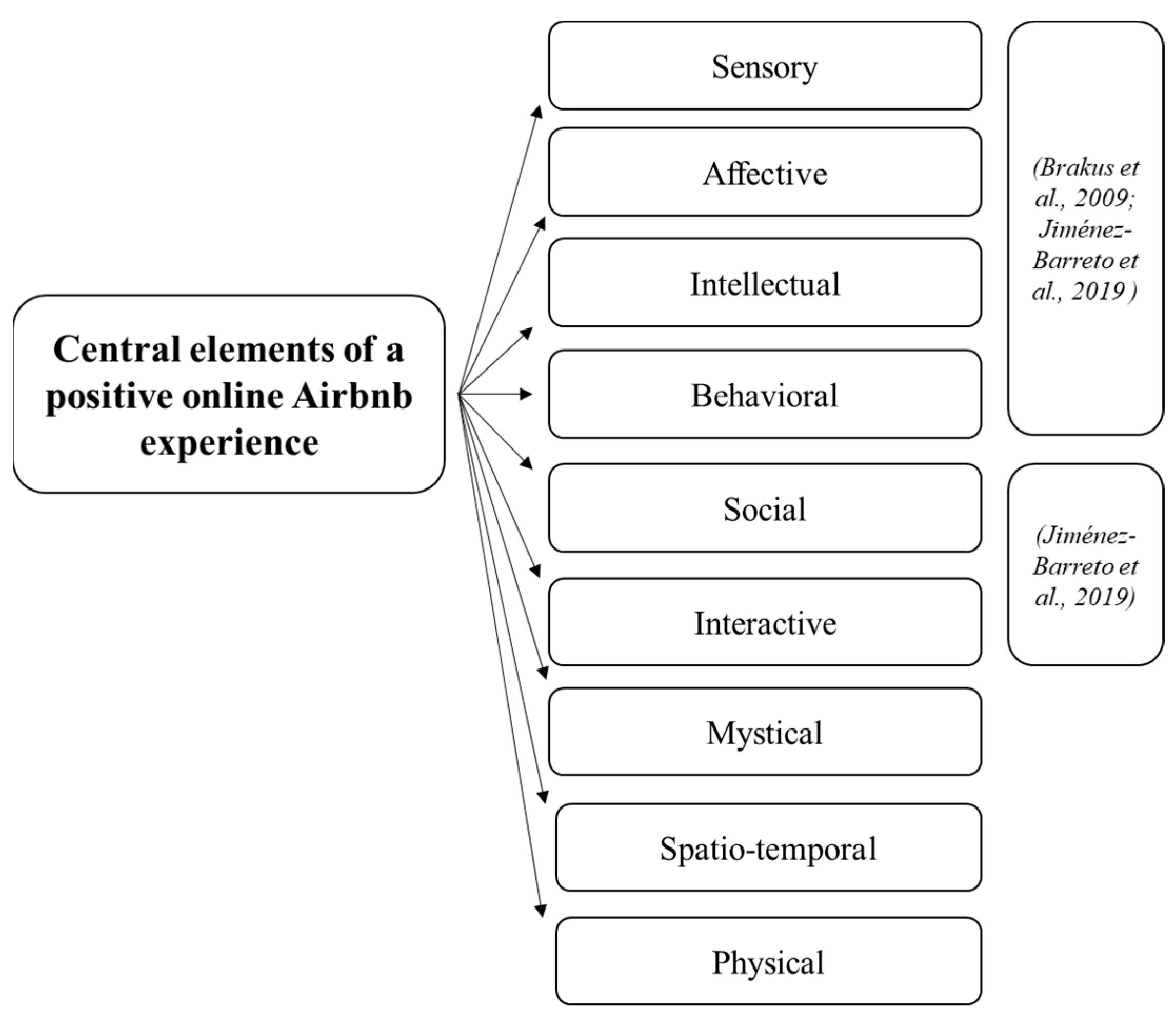

2.2. Dimensions of Online Experience

2.3. Virtual Authenticity in Digital Tourism

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

4.1. First Part—Contextual Motivation

4.2. Second Part—Dimensions

4.2.1. Sensory Dimension

4.2.2. Affective Dimension

4.2.3. Intellectual Dimension

4.2.4. Behavioral Dimension

4.2.5. Social Dimension

4.2.6. Interactive Dimension

4.2.7. Mystical Dimension

4.2.8. Spatio-Temporal Dimension

4.2.9. Physical Dimension

5. Discussion

6. Managerial Implications

7. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aldiabat, K. M., & Navenec, C. L. (2018). Data saturation: The mysterious step in Grounded Theory methodology. The Qualitative Report, 23(1), 245–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnhold, U. (2010). User generated branding: Integrating user generated content into brand management. Springer Science & Business Media. [Google Scholar]

- Backman, K., & Kyngäs, H. A. (1999). Challenges of the grounded theory approach to a novice researcher. Nursing & Health Sciences, 1(3), 147–153. [Google Scholar]

- Barbour, R. S. (2001). Checklists for improving rigour in qualitative research: A case of the tail wagging the dog? BMJ, 322(7294), 1115–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnes, S. J., Mattsson, J., & Sorensen, F. (2014). Destination brand experience and visitor behaviour: Testing a scale in tourism context. Annals of Tourism Research, 48, 121–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, L. F., & Russell, J. A. (2015). The psychological construction of emotion. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Binkhorst, E., & Den Dekker, T. (2009). Agenda for co-creation tourism experience research. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 18(2–3), 311–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birks, M., & Mills, J. (2015). Grounded theory: A practical guide (2nd ed.). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Bitner, M. J. (1992). Servicescapes: The impact of physical surroundings on customers and employees. Journal of Marketing, 56(2), 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blascovich, J., Loomis, J., Beall, A. C., Swinth, K. R., Hoyt, C. L., & Bailenson, J. N. (2002). Immersive virtual environment technology as a methodological tool for social psychology. Psychological Inquiry, 13(2), 103–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleier, A., Harmeling, C. M., & Palmatier, R. W. (2019). Creating effective online customer experiences. Journal of Marketing, 83(2), 98–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brakus, J. J., Schmitt, B. H., & Zarantonello, L. (2009). Brand experience: What is it? How is it measured? Does it affect loyalty? Journal of Marketing, 73(3), 52–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burmann, C. (2010). A call for ‘user-generated branding’. Journal of Brand Management, 18, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burmann, C., & Arnhold, U. (2008). User generated branding: State of the art of research. USB Cologne (EcoSocSci). [Google Scholar]

- Bustamante, J. C., & Rubio, N. (2017). Measuring customer experience in physical retail environments. Journal of Service Management, 28(5), 884–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructing grounded theory (2nd ed.). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Chekembayeva, G., & Garaus, M. (2024). Authenticity matters: Investigating virtual tours’ impact on curiosity and museum visit intentions. Journal of Services Marketing, 38(7), 941–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2015). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (4th ed.). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J. W., Hanson, W. E., Clark Plano, V. L., & Morales, A. (2007). Qualitative research designs: Selection and implementation. The counseling psychologist, 35(2), 236–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J. L. (2019). Authenticity, digital media, and person identity verification. In Identities in everyday life (pp. 93–111). Oxford University. [Google Scholar]

- Ewing, M. T., Wagstaff, P. E., & Powell, I. H. (2013). Brand rivalry and community conflict. Journal of Business Research, 66(1), 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagerstrøm, A., Pawar, S., Sigurdsson, V., Foxall, G. R., & Yani-de-Soriano, M. (2017). That personal profile image might jeopardize your rental opportunity! On the relative impact of the seller’s facial expressions upon buying behavior on Airbnb™. Computers in Human Behavior, 72, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, D. X., Hsu, C. H., & Lin, B. (2020). Tourists’ experiential value co-creation through online social contacts: Customer-dominant logic perspective. Journal of Business Research, 108, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X., Chen, P., Wang, M., & Wang, S. (2025). Examining the role of compression in influencing AI-generated image authenticity. Scientific Reports, 15, 12192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, B. W., Li, Y., Bu, N., & Zhu, C. Z. G. (2025). Beyond authenticity: Scale development and validation for virtual authenticity. Current Issues in Tourism, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, B. W., Zhu, C., Song, H., & Dempsey, I. M. B. (2022). Interpreting the perceptions of authenticity in virtual reality tourism through postmodernist approach. Information Technology & Tourism, 24(1), 31–55. [Google Scholar]

- Gefen, D., & Straub, D. (2003). Managing user trust in B2C e-services. E-Service Journal, 2(2), 7–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, B. G. (1978). Theoretical sensitivity. The Sociology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Aldine. [Google Scholar]

- Goulding, C. (2002). Grounded theory: A practical guide for management, business and market researchers. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Guest, G., Bunce, A., & Johnson, L. (2006). How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods, 18(1), 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guttentag, D., Smith, S., Potwarka, L., & Havitz, M. (2018). Why tourists choose Airbnb: A motivation-based segmentation study. Journal of Travel Research, 57(3), 342–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, L., & James, E. L. (1998). Interactivity reexamined: A baseline analysis of early business web sites. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 42(4), 457–474. [Google Scholar]

- Harry, B., Sturges, K. M., & Klingner, J. K. (2005). Mapping the process: An exemplar of process and challenge in grounded theory analysis. Educational Researcher, 34(2), 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatchuel, A. (2005). Towards an epistemology of collective action: Management research as a responsive and actionable discipline. European Management Review, 2(1), 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennink, M. M., Kaiser, B. N., & Marconi, V. C. (2017). Code saturation versus meaning saturation: How many interviews are enough? Qualitative Health Research, 27(4), 591–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias, J. A., Angelov, P., Ledezma, A., & Sanchis, A. (2011). Creating evolving user behavior profiles automatically. IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering, 24(5), 854–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y., Ramkissoon, H., Mavondo, F. T., & Feng, S. (2017). Authenticity: The link between destination image and place attachment. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 26(2), 105–124. [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez-Barreto, J., Sthapit, E., Rubio, N., & Campo, S. (2019). Exploring the dimensions of online destination brand experience: Spanish and North American tourists’ perspectives. Tourism Management Perspectives, 31, 348–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, A. G., & Neuhofer, B. (2017). Airbnb–an exploration of value co-creation experiences in Jamaica. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 29(9), 2361–2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J., Suh, Y., & Lee, H. (2022). Authenticity of virtual tourism in open-world video games: A case study on The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild. Information Technology & Tourism, 24(3), 369–391. [Google Scholar]

- Kirby, D. (2014). Fantasy and belief: Alternative religions, popular narratives, and digital cultures. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kokalitcheva, K. (2016, November 17). Airbnb wants to go beyond home-sharing with debut of “Experiences”. Fortune. [Google Scholar]

- Kozinets, R. V. (2015). Netnography: Redefined. Sage Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Köchling, A. (2020). ‘Dream now, travel later’: Pre-travel online destination experiences on destination websites. Journal of Qualitative Research in Tourism, 1(1), 51–72. [Google Scholar]

- Krishna, A., & Schwarz, N. (2014). Sensory marketing, embodiment, and grounded cognition: A review and introduction. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 24(2), 159–168. [Google Scholar]

- Kuijt-Evers, L. F., Groenesteijn, L., de Looze, M. P., & Vink, P. (2004). Identifying factors of comfort in using hand tools. Applied ergonomics, 35(5), 453–458. [Google Scholar]

- Kvale, S., & Brinkmann, S. (2009). Interviews: Learning the craft of qualitative research interviewing (2nd ed.). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Lalicic, L., & Weismayer, C. (2017). The role of authenticity in Airbnb experiences. In R. Schegg, & B. Stangl (Eds.), Information and communication technologies in tourism 2017 (pp. 781–794). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X., & Wang, C. (2023). Understanding the relationship between tourists’ perceptions of the authenticity of traditional village cultural landscapes and behavioural intentions, mediated by memorable tourism experiences and place attachment. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 28(3), 254–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., & Shrum, L. J. (2002). What is interactivity and is it always such a good thing? Implications of definition, person, and situation for the influence of interactivity on advertising effectiveness. Journal of Advertising, 31(4), 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano-Blasco, R., Mira-Aladrén, M., & Gil-Lamata, M. (2023). Social media influence on young people and children: Analysis on Instagram, Twitter and YouTube. Comunicar: Media Education Research Journal, 31(74), 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano-Blasco, R., Quílez-Robres, A., Delgado-Bujedo, D., & Latorre-Martínez, M. P. (2021). YouTube’s growth in use among children 0–5 during COVID-19: The Occidental European case. Technology in Society, 66, 101648. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-López, F. J., Anaya-Sánchez, R., Aguilar-Illescas, R., & Molinillo, S. (2016). Online brand communities. Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, C. (2022). How modern witches enchant TikTok: Intersections of digital, consumer, and material culture(s) on #WitchTok. Religions, 13(2), 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mody, M., Hanks, L., & Dogru, T. (2019). Parallel pathways to brand loyalty: Mapping the consequences of authentic consumption experiences for hotels and Airbnb. Tourism Management, 74, 65–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollen, A., & Wilson, H. (2010). Engagement, telepresence and interactivity in online consumer experience: Reconciling scholastic and managerial perspectives. Journal of Business Research, 63(9–10), 919–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molz, J. G. (2013). Social networking technologies and the moral economy of alternative tourism: The case of couchsurfing.org. Annals of Tourism Research, 43, 210–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mou, Y., Fan, J., Ding, Z., & Khan, I. (2024). Impact of virtual reality immersion on customer experience: Moderating effect of cross-sensory compensation and social interaction. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 36(1), 26–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mura, P., Tavakoli, R., & Pahlevan Sharif, S. (2017). Authentic but not too much: Exploring perceptions of authenticity of virtual tourism. Information Technology & Tourism, 17(2), 145–159. [Google Scholar]

- Nam, K., Dutt, C. S., & Baker, J. (2023). Authenticity in objects and activities: Determinants of satisfaction with virtual reality experiences of heritage and non-heritage tourism sites. Information Systems Frontiers, 25(3), 1219–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Näsi, M., Räsänen, P., & Lehdonvirta, V. (2011). Identification with online offline communities: Understanding ICT disparities in Finland. Technology in Society, 33(1–2), 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuhofer, B., Buhalis, D., & Ladkin, A. (2014). A typology of technology-enhanced tourism experiences. International Journal of Tourism Research, 16(4), 340–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nnindini, S. I., Zakari, B., Akolaa, A. A., & Kantanka, A. S. (2024). Trading salespersons for social media tools: A critical examination in SMEs. Cogent Business & Management, 12(1), 2438944. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor, C., & Joffe, H. (2020). Intercoder reliability in qualitative research: Debates and practical guidelines. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osler, L. (2024). Belonging online: Rituals, sacred objects, and mediated interactions. In L. Dolezal, & D. Petherbridge (Eds.), Feelings of belonging. SUNY Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pine, B. J., & Gilmore, J. H. (1998). Welcome to the experience economy. Harvard Business Review, 76, 97–105. [Google Scholar]

- Purohit, S., Hollebeek, L. D., Das, M., & Sigurdsson, V. (2023). The effect of customers’ brand experience on brand evangelism: The case of luxury hotels. Tourism Management Perspectives, 46, 101092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakshit, S., Jeyaraj, A., Paul, T., & Mondal, S. (2025). Social networking technologies in SMEs: A bibliometric analysis. Journal of Computer Information Systems, 65(2), 141–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadania, R., Reswari, R. A., Rahmawati, R., Rosyadi, R., Purmono, B. B., & Afifi, M. Z. (2025). City identity in tourist intention: Mediating role of city branding and tourism city value resonance. Cogent Business & Management, 12(1), 2474270. [Google Scholar]

- Rather, R. A., Hollebeek, L. D., Vo-Thanh, T., Ramkissoon, H., Leppiman, A., & Smith, D. (2022). Shaping customer brand loyalty during the pandemic: The role of brand credibility, value congruence, experience, identification, and engagement. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 21(5), 1175–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldaña, J. (2013). The coding manual for qualitative researchers (2nd ed.). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Saleem, T., Ishaq, M. I., Raza, A., & Junaid, M. (2024). Exploring the effect of telepresence and escapism on consumer post-purchase intention in an immersive virtual reality environment. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 81, 104014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandelowski, M., & Barroso, J. (2007). Handbook for synthesizing qualitative research. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, B. (1999). Experiential marketing. Journal of Marketing Management, 15(1–3), 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, B. (2000). Creating and managing brand experiences on the internet. Design Management Journal (Former Series), 11(4), 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyfi, S., & Hall, C. M. (2022). Applying grounded theory in hospitality and tourism research: Critical reflections. In Contemporary research methods in hospitality and tourism (pp. 253–268). Emerald Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Shamim, N., Gupta, S., & Shin, M. M. (2024). Evaluating user engagement via metaverse environment through immersive experience for travel and tourism websites. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 37(4), 1132–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K., & Biley, F. (1997). Understanding grounded theory: Principles and evaluation. Nurse Researcher, 4(3), 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sthapit, E., Björk, P., Coudounaris, D. N., & Stone, M. J. (2022). A new conceptual framework for memorable Airbnb experiences: Guests’ perspectives. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 16(1), 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sthapit, E., & Jimenez-Barreto, J. (2018). Exploring tourists’ memorable hospitality experiences: An Airbnb perspective. Tourism Management Perspectives, 28, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1999). Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Tussyadiah, I. P., Wang, D., Jung, T. H., & tom Dieck, M. C. (2018). Virtual reality, presence, and attitude change: Empirical evidence from tourism. Tourism Management, 66, 140–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volo, S. (2010). Bloggers’ reported tourist experiences: Their utility as a tourism data source and their effect on prospective tourists. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 16(4), 297–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welthagen, L. C. (2025). Technology-enhanced tourist experiences. In Tourism and hospitality for sustainable development: Volume three: Implications for customers and employees of tourism businesses (pp. 67–79). Springer Nature Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- Whitty, M. T., & Quigley, L. L. (2008). Emotional and sexual infidelity offline and in cyberspace. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 34(4), 461–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, L. E., & Poehlman, T. A. (2017). Conceptualizing consciousness in consumer research. Journal of Consumer Research, 44(2), 231–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, I. A., Lu, M. V., Lin, S., & Lin, Z. (2023). The transformative virtual experience paradigm: The case of Airbnb’s online experience. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 35(4), 1398–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yannopoulou, N., Moufahim, M., & Bian, X. (2013). User-generated brands and social media: Couchsurfing and Airbnb. Contemporary Management Research, 9(1), 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, D., & Youn, S. (2016). Brand experience on the website: Its mediating role between perceived interactivity and relationship quality. Journal of Interactive Advertising, 16(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanger, V., Meißner, M., & Rauschnabel, P. A. (2022). Beyond the gimmick: How affective responses drive brand attitudes and intentions in augmented reality marketing. Psychology & Marketing, 39(7), 1285–1301. [Google Scholar]

- Zha, D., Foroudi, P., Jin, Z., & Melewar, T. C. (2022). Making sense of sensory brand experience: Constructing an integrative framework for future research. International Journal of Management Reviews, 24(1), 130–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, D., Melewar, T. C., Foroudi, P., & Jin, Z. (2020). An assessment of brand experience knowledge literature: Using bibliometric data to identify future research direction. International Journal of Management Reviews, 22, 287–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G., So, K. K. F., & Hudson, S. (2017). Inside the sharing economy: Understanding consumer motivations behind the adoption of mobile applications. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 29(9), 2218–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J., Cheng, M., & Wang, Y. (2024). What makes people recommend Airbnb Online Experiences: The moderating effect of host. Current Issues in Tourism, 27(14), 2250–2267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Experiences | Name of the Experience | Type of Experience |

|---|---|---|

| Experience 1 | Remote Rescue Goats (https://www.airbnb.es/experiences/1655931, accessed on 1 April 2020) | Animal lovers |

| Experience 2 | Creative drawing with an illustrator—(now it’s called Drawing session—https://www.airbnb.mx/experiences/1655210?source=p2, accessed on 1 April 2020) | Artistic |

| Experience 3 | Turkish coffee and divination (now it’s a physical experience called Turkish coffee and good fortune—https://www.airbnb.es/experiences/500361, accessed on 1 April 2020) | Esoteric |

| Experience 4 | Follow a plague doctor through Prague (https://www.airbnb.es/experiences/1658926, accessed on 1 April 2020) | Touristic-cultural |

| Experience 5 | Sangria and secrets with drag queens (now it is not available on airbnb and they manage it independently and it is a physical experience—https://dragtaste.com/, accessed on 1 April 2020) | Entertaiment |

| Experience 6 | Meditation with a Buddhist monk (https://www.airbnb.es/experiences/1654801, accessed on 1 April 2020) | Wellness |

| Experience 7 | The best coffee experience in the world (https://www.airbnb.es/experiences/1655017, accessed on 1 April 2020) | Gastronomic |

| Study’s Narratives | Participants’ Narratives (Extracted Examples) | Open Coding (Line-by-Line Coding) |

|---|---|---|

| Experience 1 | “My daughter (9) really enjoyed it, especially entertaining for those who love animals” | Enjoying for kids and animal lovers |

| Experience 2 | “He then proceeded to lead a highly informative and interactive sketching session” | The instructor lead made the session informative and interactive |

| Experience 3 | “My friend and I had a blast learning about our perceived futures” | They learnt about our perceived futures |

| Experience 4 | “Learned a lot about the history of Prague”. | Lots of learning about the history of the destination |

| Experience 5 | “They truly made us all feel so special, they were engaging, entertaining, and really did it up!” | The instructors made the participants feel so special |

| Experience 6 | “Very interesting meditation with nice people” | The participant appreciates the meditation with nice people |

| Experience 7 | “I had a great time learning about coffee with Ricardo” | The participant had a great experience learning about coffee |

| Open Coding (Line-by-Line Coding) | Subthemes (Axial Coding) | Main Themes (Selective Themes) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Contextual Motivation | “Amazing knowledge”, “The experience was fun, educational and Meagan is very passionate! oved seeing and learning about the different goats!”, “Very enjoyable and we learned a lot.” | Educational experiences | Educational and entertainment experiences take part of the contextual motivation of a positive Airbnb online experience. |

| “The experience was fun, educational and Meagan is very passionate! Very enjoyable and we learned a lot. My daughter (9) really enjoyed it and loved meeting all the goats!” | Entertaiment experiences | ||

| Dimensions | “It’s very pleasant to see the goats…” “Kids would enjoy this experience—getting to see so many goats up close!.” | Sensory experience | The sensory, affective, intellectual, social, behavioral, interactive, and spatio-temporal dimensions are the central elements of the positive online Airbnb experience |

| “This is a fun and educational experience for all ages and especially entertaining for those who love animals”, “My daughter (9) really enjoyed it and loved meeting all the goats!”, “This was a lovely experience, It’s very pleasant to see the goats.” | Affective experience | ||

| “The experience was fun, educational”, “She’s very knowledgeable”, “Very enjoyable and we learned a lot.” | Intellectual experience | ||

| “Can’t wait to visit in person one day soon.”, “Wonderful experience short of being there in person!” | Behavioral experience | ||

| “Absolutely recommend this experience to connect with Meagan and her playful goats!” | Social experience | ||

| “Meagan was welcoming and encouraged participation.”, “My kids loved it and was able to ask questions about them.” | Interactive experience | ||

| “Mentally transported to another place for an hour. A great escape.”, “A great activity for when you’re stuck in doors but would rather be petting super cute goats.”, “A lovely escape! Perfect getaway with goats!” | Spatio-temporal experience | ||

| Codes indicating the significance of Contextual Motivation and Experience Dimensions from Online Destination Experience 2 (Creative drawing with an illustration). | |||

| Open Coding (Line-by-Line Coding) | Subthemes (Axial Coding) | Main Themes (Selective Themes) | |

| Contextual Motivation | “Thank you for teaching us a great new technique”, “My kids and I learned in a very special way to make some faces!”, “Learned a lot in a short amount of time!” | Educational experiences | Educational and entertainment experiences take part of the contextual motivation of a positive Airbnb online experience. |

| “Super fun experience!”, “It’s a fun experience to do with family and friends while sharping your drawing skills!”, “I had such a fun time!” | Entertaiment experiences | ||

| Dimensions | “In such a short time Gabriel taught us the basics of creating a face with gestures and colors.”, “The video and audio quality were excellent.”, “it was so lovely to see the drawings others in the group created.” | Sensory experience | The sensory, affective, intellectual, social, behavioral, interactive, spatio-temporal, and physical dimensions are the central elements of the positive online Airbnb experience |

| “…the instructor has a kind and great personality and makes everyone feel welcome.”, “He is very warm and teaches how to love drawing for any level.”, “I felt very inspired!”, “You could feel his warmth and authenticity coming through the screen.”, “Although I was embarrassed initially with my drawings, he didn’t make me feel dumb about them and was incredibly encouraging.”, “keep us feeling encouraged.” | Affective experience | ||

| “I loved learning about the proportions and the shading”, “He then proceeded to lead a highly informative and interactive sketching session.”, “Learned a lot in a short amount of time!”, “The user learned some new techniques.” | Intellectual experience | ||

| “He is very warm and teaches how to love drawing for any level.”, “I can finally draw a face!”, “We discussed technique and design and completed a few round of sketches.”, “It was so lovely to see the drawings others in the group created.” | Behavioral experience | ||

| “What a great way to interact with other humans”, “This was really a wonderful way to start the day and connect with others.”, “It’s a fun experience to do with family and friends while sharping your drawing skills!”, “He really made an effort to relate with each one of us in the class (there were 6 of us) and keep us feeling encouraged.” | Social experience | ||

| “He then proceeded to lead a highly informative and interactive sketching session.”, “What a great way to interact with other humans.”, “Great interaction and communication.”, “Good instructions and helpful advice to complete the art assignments.” | Interactive experience | ||

| “The instructor has a kind and great personality and makes everyone feel welcome.”, “I felt full of energy and excitement after exploring my creativity with you and other guests.”, “I loved learning about the proportions and the shading, all from the comforts of my own home”,“I never would have taken the time to stop, relax and get creative if it wasn’t for this experience: | Physical | ||

| Codes indicating the significance of Contextual Motivation and Experience Dimensions from Online Destination Experience 3 (Turkish coffee and divination). | |||

| Open Coding (Line-by-Line Coding) | Subthemes (Axial Coding) | Main Themes (Selective Themes) | |

| Contextual Motivation | “My friend and I had a blast learning about our perceived futures.”, “…learn something new through the host and his passion for Turkish coffee fortune reading.” | Educational experiences | Educational and entertainment experiences take part of the contextual motivation of a positive Airbnb online experience. |

| “…uluç kept the entire group on their toes with his highly entertaining reading style.”, “What a super fun date night during COVID.”, “…it was very fun.” | Entertaiment experiences | ||

| Dimensions | “…I loved hearing everyone else’s reading…”, “Each reading was personal and insightful, and it was fun and fascinating to listen to others’ fortunes”. | Sensory experience | The sensory, affective, intellectual, social, mystical, interactive, spatio-temporal, and physical dimensions are the central elements of the positive online Airbnb experience |

| “… I left full of hope.”, “Uluc is a natural-born story teller and made us all feel connected to one another.”, “… while simultaneously ensuring everyone involved feels seen, welcomed and participates.”, “Uluc was so personable and made sure each and every one of us was comfortable and fully engaged.”, “…my personal fortune brought tears to my eyes …”, “It really is a joy to not only participate and receive a reading from such an insightful host but also to witness how Uluc uses this traditional method to connect people with each other and with the deeper aspects of themselves…”, “… this experience and the warmth and incredible knowledge of the host, make it unique and hopeful…” | Affective experience | ||

| “…this experience and the warmth and incredible knowledge of the host …”, “…and learn something new through the host …”, “My friend and I had a blast learning about our perceived futures …”, “It was great getting to learn about him, and his culture …” | Intellectual experience | ||

| “his online experience was a really great way to meet up with new people”, “Uluc is able to effortlessly connect with each person in the group…”, “…and getting to know other members in our group!”, “…and made us all feel connected to one another “, “…this traditional method to connect people with each other and with the deeper aspects of themselves…”, “… I loved hearing everyone else’s reading. Great to do with friends!” | Social experience | ||

| “The whole process is interactive, engaging and inspiring.”, “Great interaction for an online experience…”, “…while simultaneously ensuring everyone involved feels seen, welcomed and participates.”, “…Uluc uses this traditional method to connect people with each other and with the deeper aspects of themselves.” | Interactive experience | ||

| “It is a very beautiful and mystical experience …”, “It was truly magical …” | Mystical experience | ||

| “…for the first time in a long time, it took my mind off of what’s going in the world”. | Spatio-temporal | ||

| “ You instantly feel comfortable and welcome in his presence…”, “Uluc was so personable and made sure each and every one of us was comfortable and fully engaged.”, “I love his energy he made me feel better in this situation.” | Physical | ||

| Codes indicating the significance of Contextual Motivation and Experience Dimensions from Online Destination Experience 4 (Follow a plague doctor through Prague). | |||

| Open Coding (Line-by-Line Coding) | Subthemes (Axial Coding) | Main Themes (Selective Themes) | |

| Contextual Motivation | “Learned a lot about the history of Prague.”, “It was fascinating to learn the history”, “I learn a lot, thank you, Lucie!”, “…and I learned SO MUCH!”, “A great deal of fun while being educational!” | Educational experiences | Educational and entertainment experiences take part of the contextual motivation of a positive Airbnb online experience. |

| “…really enjoyed it.”, “It was a whole new experience and a lot of fun.”, “Very interesting and entertaining…”, “A great deal of fun while being educational!” | Entertaiment experiences | ||

| “…and walk in the shoes of a plague doctor!”, “A great way to view Old Town Prague WITHOUT PEOPLE…” | Sensory experience | The sensory, affective, intellectual, social, behavioral, spatio-temporal, and physical dimensions are the central elements of the positive online Airbnb experience. | |

| “David was awesome!…”, “My 8 yo son loved this Airbnb experience…”, “I loved this experience…”, “…I loved the way it was filmed and I learned SO MUCH!…” | Affective experience | ||

| “Learned a lot about the history of Prague.”, “… David was highly knowledgable about both Prague and the plague.”, “…I loved the way it was filmed and I learned SO MUCH!.”, “It was fascinating to learn the history” | Intellectual experience | ||

| “Lovely night stroll through the legendary streets of Prague. Once quarantine is over, we must go!”, “…I really would like to join the REAL tour some day!” | Behavioral experience | ||

| “My 8 yo son loved this Airbnb experience, despite being only with adults.”, “Thank you was great to connect and be with others” | Social experience | ||

| “…Like a TRUE journey back in time!…”, “…Nice to ‘virtual travel’ to a different era and a different place.”, “…we’re time traveling into the past from the comfort of our couches…”, “I forgot for a while that I was quarantined at home…” | Spatio-temporal experience | ||

| “The future is here—we’re time traveling into the past from the comfort of our couches.” | Physical experience | ||

| Codes indicating the significance of Contextual Motivation and Experience Dimensions from Online Destination Experience 5 (Sangria and secrets with drag queens). | |||

| Open Coding (Line-by-Line Coding) | Subthemes (Axial Coding) | Main Themes (Selective Themes) | |

| Contextual Motivation | “Great interactive experience that made me laugh and learn.”, “I learned a new recipe for sangria and have been enjoying the “fruits” of my labor for days!”, “Loved learning about Sangria and it’s place in Portuguese culture”. | Educational experiences | Educational and entertainment experiences take part of the contextual motivation of a positive Airbnb online experience. |

| “Really fun!”, “This was so fun and unique…”, “…seriously it’s legit and so much fun.”, “so much fun…” | Entertaiment experiences | ||

| Dimensions | “…watch an awesome show…”, “…enjoyed a delicious sangria.”, “Plus the Sangria tastes great!” | Sensory experience | The sensory, affective, intellectual, social, behavioral, interactive, spatio-temporal, and physical dimensions are the central elements of the positive online Airbnb experience. |

| “This event made their 21st birthday one of the most memorable birthdays of their lives.”, “…They truly made us all feel so special…”, “…I was impressed with how many different countries were represented by the participants and I loved how everyone was there to just have a good time”, “Loved feeling connected to all attendees from around the world.”, “…made me feel so special to have my friends celebrating with me!” | Affective experience | ||

| “Pedro and his team bring such energy, knowledge, and personality to the experience.”, “Loved learning about Sangria and it’s place in Portuguese culture.”, “Great interactive experience that made me laugh and learn”. | Intellectual experience | ||

| “when none of us can got out of the house to do anything close to this fun!”, “Can’t wait to come to Lisbon and get to meet you all in person!! “, “It was such a fun event to make sangria with them and it was amazing! Could not recommend more”, “… we had a blast making sangria…”, “Cannot wait to visit! Do this now!!!”, “We cannot wait to come visit in the future!!!”, “I will definitely be making this killer sangria on repeat.” | Behavioral experience | ||

| “…A bunch of my friends popped on for my partners birthday, and what a perfect choice it was!…”, “My husband and I book this experience to celebrate our anniversary and we are glad that we did!!!! The host and his friends made it a point to interact with all participants numerous times and there was lots of laughs and entertainment….”, “I was impressed with how many different countries were represented by the participants and I loved how everyone was there to just have a good time.”, “It’s such a fun way to virtually connect with people during the pandemic. They made it a special way to connect with people all over the world! ”, “Booked this event with several friends across the country.”, “It worked really well for my bookclub friends to join in so that we were there as a “group”.”, “I could keep doing this every week with my friends”, “Loved feeling connected to all attendees from around the world.” | Social experience | ||

| “They handled the large zoom group very well, making sure to check in with each participant multiple times so we all felt like participants and not just observers.”, “Great interactive experience that made me laugh and learn.”, “There were other groups there as well and that led to some very nice interaction with Pedro and Babaya.”, “Pedro was really engaging too by enticing guest to interact and sharing attention with all participants!”, “We highly recommend this experience if you want to interact with some fun people and make something great to drink!”, “I loved how all the guests participated and there were a lot of cooking tips thrown in.” | Interactive experience | ||

| “It was a great way to get “out” without leaving the house” | Spatio-temporal experience | ||

| “The girls made us feel sooo comfortable during the entire time.”, “Pedro and his team bring such energy…” | Physical experience | ||

| Codes indicating the significance of Contextual Motivation and Experience Dimensions from Online Destination Experience 6 (Meditation with a Buddhist monk). | |||

| Open Coding (Line-by-Line Coding) | Subthemes (Axial Coding) | Main Themes (Selective Themes) | |

| Contextual Motivation | “…and explains the practice in an easy method to follow.”, “…kuniatsu introduces some new techniques and really helps focus your mind.” | Educational experiences | Educational and entertainment experiences take part of the contextual motivation of a positive Airbnb online experience. |

| “I enjoyed being with Kuniatsu.”, “A fun experience…” | Entertaiment experiences | ||

| Dimensions | “I enjoyed listening to his stories.” | Sensory experience | The sensory, affective, intellectual, social, behavioral, spatio-temporal, and physical dimensions are the central elements of the positive online Airbnb experience |

| “Kuniatsu is very warm and welcoming.”, “I got relax and happy”, “…Beautiful kind hearted host. …”, “…Kuniatsu-san radiates joy.” | Affective experience | ||

| “…kuniatsu introduces some new techniques and really helps focus your mind.”, “…explains the practice in an easy method to follow.”, “Really enjoyed his meditation lecture & exercises.” | Intellectual experience | ||

| “Would definitely do it again and recommend to a friend.”, “Would love to do it again and maybe even try a different type of course led by Kuniatsu” | Behavioral experience | ||

| “Very interesting meditation with nice people…” | Social experience | ||

| “A brief escape and forced me outside of my comfort zone.” | Spatio-temporal experience | ||

| “The meditation session was immersive and refreshing.”, “Felt refreshed and calm after”, “I got relax and happy”, “It was calming and relaxing.”, “Came out of the meditation session feeling relaxed and calm for the whole day.”, “Suzuki has a great energy” | Physical experience | ||

| Codes indicating the significance of Contextual Motivation and Experience Dimensions from Online Destination Experience 7 (The best coffee experience in the world). | |||

| Open Coding (Line-by-Line Coding) | Subthemes (Axial Coding) | Main Themes (Selective Themes) | |

| Contextual Motivation | “Would recommend Ricardo to anyone who wants to learn about coffee.”, “Ricardo was a great host and teacher.”, “I had a great time learning about coffee with Ricardo.”, “I learned a lot during our hour together.” | Educational experiences | Educational and entertainment experiences take part of the contextual motivation of a positive Airbnb online experience. |

| “This class was fun!”, “Ricardo is a wealth of knowledge and is very entertaining and engaging.” | Entertaiment experiences | ||

| Dimensions | “Really cool to see Ricardo’s house and street view even on Zoom.”, “Very good intro to different flavour profiles and great tips to try at home to improve coffee flavour.”, “Ricardo helped us fine-tune our coffee tasting experience at home.” | Sensory experience | The sensory, affective, intellectual, and behavioral, dimensions are the central elements of the positive online Airbnb experience |

| “I love coffee and I think I will be able to make a better cup.”, “Ricardo’s knowledge was excellent and his personality and passion was apparent during the class.”, “Ricardo was lovely” | Affective experience | ||

| “Would recommend Ricardo to anyone who wants to learn about coffee.”, “…I learned a lot during our hour together.”, “A very nice experience in how to make a tasty cup of coffe.”, “and will give you some solid basics in coffee making.”, “Left with enough knowledge to start experimenting.”, “I am going to look for more Airbnb experiences.” | Intellectual experience | ||

| “A very nice experience in how to make a tasty cup of coffe.”, “Now I can make better coffee”, “I think I will be able to make a better cup.” | Behavioral experience | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cerdá-Mansilla, E.; Lozano-Blasco, R.; Rubio, N. User Experience Dimensions in Digital Peer-to-Peer Platforms: A Grounded Theory Study of Airbnb Online Experiences. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 169. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15050169

Cerdá-Mansilla E, Lozano-Blasco R, Rubio N. User Experience Dimensions in Digital Peer-to-Peer Platforms: A Grounded Theory Study of Airbnb Online Experiences. Administrative Sciences. 2025; 15(5):169. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15050169

Chicago/Turabian StyleCerdá-Mansilla, Elena, Raquel Lozano-Blasco, and Natalia Rubio. 2025. "User Experience Dimensions in Digital Peer-to-Peer Platforms: A Grounded Theory Study of Airbnb Online Experiences" Administrative Sciences 15, no. 5: 169. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15050169

APA StyleCerdá-Mansilla, E., Lozano-Blasco, R., & Rubio, N. (2025). User Experience Dimensions in Digital Peer-to-Peer Platforms: A Grounded Theory Study of Airbnb Online Experiences. Administrative Sciences, 15(5), 169. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15050169