Cultural Dynamics and Ambidextrous Innovation: Insights from Saudi Arabia’s Project-Based Organizations—A Thematic–Explorative Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Ambidextrous Innovation

2.2. Organization Culture

2.3. Project Innovation and Culture—Saudi Arabian Context

3. Research Methods

3.1. Interview

- Q1: Tell me about a project you worked on where innovation implementation worked well?

- Q2: Tell me about a project you worked on where innovation implementation did not work well?

- Q3: Tell me about working on your daily project operation and having a new innovative project work well?

- Q4: Tell me about working on your daily project operation and having a new innovative project that did not work well?

3.2. Data Analysis of Interviews

3.3. Descriptive Analysis of Samples: Interviews

3.4. Focus Groups

3.5. Focus Group Participants

4. Collection and Analysis of Data

4.1. Undertaking the Research Context

4.2. Main Interviews

4.2.1. Interviews Data Analysis: Organizational Cultural Aspects

4.2.2. Validation

4.2.3. Results of Data Analysis

4.2.4. Discussion of Aspects

4.3. Focus Group One: Refining the Aspects

4.4. Focus Group Two: Developing the Themes

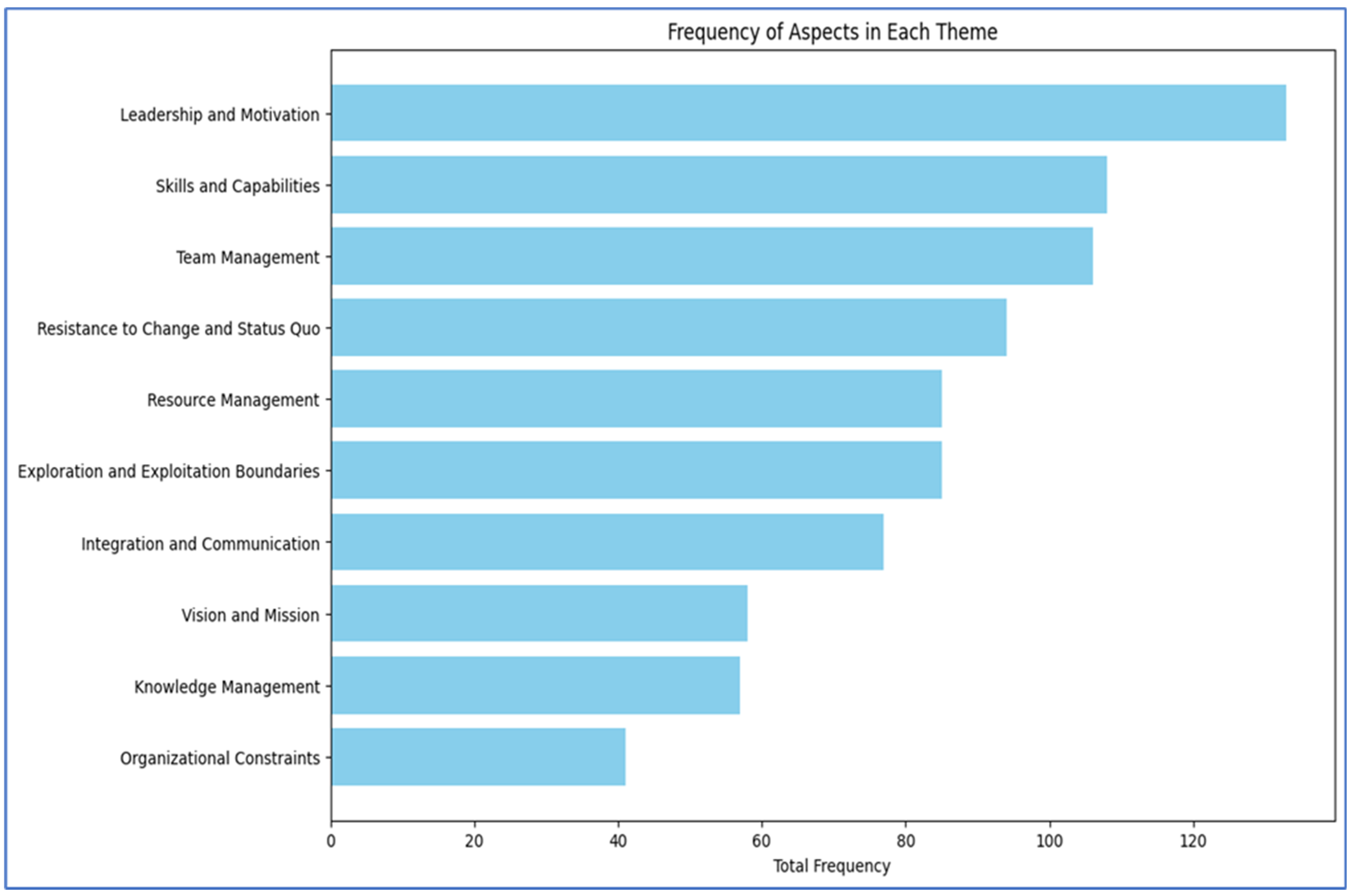

4.5. Frequency Analysis of Aspects into Themes

5. Positioning of Organizational Culture Themes into Ambidexterity

6. Validations

6.1. Reliability

6.2. Confirmability

6.3. Dependability

6.4. Transferability

6.5. Triangulations

6.6. Inter-Rater Reliability

7. Discussion

8. Conclusions

8.1. Limitations of Research

8.2. Future Research Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adeoye-Olatunde, O. A., & Olenik, N. L. (2021). Research and scholarly methods: Semi-structured interviews. Journal of the American College of Clinical Pharmacy, 4(10), 1358–1367. [Google Scholar]

- Ahsan, K., Ho, M., & Khan, S. (2013). Recruiting project managers: A comparative analysis of competencies and recruitment signals from job advertisements. Project Management Journal, 44(5), 36–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akpa, V. O., Asikhia, O. U., & Nneji, N. E. (2021). Organizational culture and organizational performance: A review of literature. International Journal of Advances in Engineering and Management, 3(1), 361–372. [Google Scholar]

- Alaloul, W. S., Alzubi, K. M., Malkawi, A. B., Al Salaheen, M., & Musarat, M. A. (2022). Productivity monitoring in building construction projects: A systematic review. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management, 29(7), 2760–2785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M. (2021). Imitation or innovation: To what extent do exploitative learning and exploratory learning foster imitation strategy and innovation strategy for sustained competitive advantage?✰. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 165, 120527. [Google Scholar]

- AlSaied, M., & McLaughlin, P. (2024a). Ambidextrous innovation in project management: A systematic literature review. Administrative Sciences, 14(7), 151. [Google Scholar]

- AlSaied, M., & McLaughlin, P. (2024b). Organizational Culture enabler and inhibitor factors for ambidextrous innovation. Administrative Sciences, 14(9), 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E. G., Jr., Chandrasekaran, A., Davis-Blake, A., & Parker, G. G. (2018). Managing distributed product development projects: Integration strategies for time-zone and language barriers. Information Systems Research, 29(1), 42–69. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson, R. (1999). Project management: Cost, time and quality, two best guesses and a phenomenon, its time to accept other success criteria. International Journal of Project Management, 17(6), 337–342. [Google Scholar]

- Azeem, M., Salfi, N. A., & Dogar, A. H. (2012). Usage of NVivo software for qualitative data analysis. Academic Research International, 2(1), 262–266. [Google Scholar]

- Babbie, E. R. (2015). The practice of social research. Wadsworth Cengage Learning. [Google Scholar]

- Babu, A. J. G., & Suresh, N. (1996). Project management with time, cost, and quality considerations. European journal of operational research, 88(2), 320–327. [Google Scholar]

- Bagherzadeh, M., Markovic, S., & Bogers, M. (2019). Managing open innovation: A project-level perspective. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 68(1), 301–316. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, J. (2008). First steps in qualitative data analysis: Transcribing. Family practice, 25(2), 127–131. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bans-Akutey, A., & Tiimub, B. M. (2021). Triangulation in research. Academia Letters, 2, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Barjak, F., & Heimsch, F. (2023). Understanding the relationship between organizational culture and inbound open innovation. European Journal of Innovation Management, 26(3), 773–797. [Google Scholar]

- Batra, I. P. P., & Dhir, S. (2022). Organizational ambidexterity from the emerging market perspective: A review and research agenda. Thunderbird International Business Review, 64(5), 559–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battaglia, D., Neirotti, P., & Paolucci, E. (2018). The role of R&D investments and export on SMEs’ growth: A domain ambidexterity perspective. Management Decision, 56(9), 1883–1903. [Google Scholar]

- Bazeley, P. (2009). Analysing qualitative data: More than ‘identifying themes’. Malaysian Journal of Qualitative Research, 2(2), 6–22. [Google Scholar]

- Binci, D., Cerruti, C., Masili, G., & Paternoster, C. (2023). Ambidexterity and Agile project management: An empirical framework. The TQM Journal, 35(5), 1275–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkinshaw, J., Brannen, M. Y., & Tung, R. L. (2011). From a distance and generalizable to up close and grounded: Reclaiming a place for qualitative methods in international business research. Journal of International Business Studies, 42, 573–581. [Google Scholar]

- Birkinshaw, J., Zimmermann, A., & Raisch, S. (2016). How do firms adapt to discontinuous change? Bridging the dynamic capabilities and ambidexterity perspectives. California Management Review, 58(4), 36–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, S. K. (1999). Cross-functional project teams in functionally aligned organizations. Project Management Journal, 30(3), 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond-Barnard, T. J., Fletcher, L., & Steyn, H. (2018). Linking trust and collaboration in project teams to project management success. International Journal of Managing Projects in Business, 11(2), 432–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2012). Thematic analysis. American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2023). Toward good practice in thematic analysis: Avoiding common problems and be (com) ing a knowing researcher. International Journal of Transgender Health, 24(1), 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braunerhjelm, P., & Thulin, P. (2023). Does innovation lead to firm growth? Explorative versus exploitative innovations. Applied Economics Letters, 30(9), 1179–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burford, L. D. (2012). Project management for flat organizations: Cost effective steps to achieving successful results. J. Ross Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Büschgens, T., Bausch, A., & Balkin, D. B. (2013). Organizational culture and innovation: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 30(4), 763–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, C. M., & Suto, M. (2008). Qualitative research for occupational and physical therapists: A practical guide. Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J., Taylor, J. E., & Comu, S. (2017). Assessing task mental workload in construction projects: A novel electroencephalography approach. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, 143(8), 04017053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claes, M. T. (1999). Women, men and management styles. International Labour Review, 138, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, A., & Postel-Vinay, F. (2009). Job security and job protection. Oxford Economic Papers, 61(2), 207–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, I. (1998). Competitive pressures and engineering process plant contracting. Human Resource Management Journal, 8(2), 14–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conforto, E. C., Amaral, D. C., Da Silva, S. L., Di Felippo, A., & Kamikawachi, D. S. L. (2016). The agility construct on project management theory. International Journal of Project Management, 34(4), 660–674. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin, J. M., & Strauss, A. (1990). Grounded theory research: Procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. Qualitative Sociology, 13(1), 3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2015). Basics of qualitative research (Vol. 14). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford, J. K., Cabanis-Brewin, J., Bigelow, D., James, C., & Pennypacker, S. (2004). Project management roles and responsibilities. Center for Business Practices. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford, P., & Bryce, P. (2003). Project monitoring and evaluation: A method for enhancing the efficiency and effectiveness of aid project implementation. International Journal of Project Management, 21(5), 363–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deal, T. E., & Kennedy, A. A. (1983). Culture: A new look through old lenses. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 19(4), 498–505. [Google Scholar]

- Dean, B. P. (2022). Developing and leading ambidextrous teams: A team-centric framework of ambidexterity in volatile environments. Journal of Change Management, 22(2), 120–146. [Google Scholar]

- Decuypere, A., & Schaufeli, W. (2021). Exploring the leadership–engagement nexus: A moderated meta-analysis and review of explaining mechanisms. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(16), 8592. [Google Scholar]

- Do, B. R., Yeh, P. W., & Madsen, J. (2016). Exploring the relationship among human resource flexibility, organizational innovation and adaptability culture. Chinese Management Studies, 10(4), 657–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donate, M. J., & Guadamillas, F. (2010). The effect of organizational culture on knowledge management practices and innovation. Knowledge and Process Management, 17(2), 82–94. [Google Scholar]

- Dulewicz, V., & Higgs, M. (2000). Emotional intelligence—A review and evaluation study. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 15(4), 341–372. [Google Scholar]

- Dunbar, R., & Guillet de Monthoux, P. (1979). Fear of failure in project management. In Surviving failures: Patterns and cases of project mismanagement (pp. 199–217). Proceedings from the Stockholm Symposium on ‘Surviving Faures’. Almqvist & Wiksell International. [Google Scholar]

- Duwe, J. (2022). Success through ambidextrous communication. In Ambidextrous leadership: How leaders unlock innovation through ambidexterity (pp. 19–59). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Eloranta, E., Hameri, A. P., & Lahti, M. (2001). Improved project management through improved document management. Computers in Industry, 45, 231–243. [Google Scholar]

- Ennis, C. D., & Chen, S. (2012). Interviews and focus groups. In Research methods in physical education and youth sport (pp. 217–236). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson, P. E. (2013). Exploration and exploitation in project-based organizations: Development and diffusion of knowledge at different organizational levels in construction companies. International Journal of Project Management, 31(3), 333–341. [Google Scholar]

- Ershadi, M. J., Edrisabadi, R., & Shakouri, A. (2020). Strategic alignment of project management with health, safety and environmental management. Built Environment Project and Asset Management, 10(1), 78–93. [Google Scholar]

- Foreman, K. (1998). Vision and mission. In Strategic management in schools and colleges (pp. 18–31). Paul Chapman Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Francis, F., Zirra, C. T. O., & Mambula, C. J. (2020). Reward system as a strategy to enhance employees performance in an organization. Archives of Business Review, 8(6), 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gertler, P. J., Martinez, S., Premand, P., Rawlings, L. B., & Vermeersch, C. M. (2016). Impact evaluation in practice. World Bank Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Ghiselli, E. E., & Siegel, J. P. (1972). Leadership and managerial success in tall and flat organization structures. Personnel Psychology, 25(4), 617–624. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, C., & Mumford, M. D. (2013). Evaluation, criticism, and creativity: Criticism content and effects on creative problem solving. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 7(4), 314. [Google Scholar]

- Gillard, S. (2009). Soft skills and technical expertise of effective project managers. Issues in Informing Science & Information Technology, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Gisev, N., Bell, J. S., & Chen, T. F. (2013). Interrater agreement and interrater reliability: Key concepts, approaches, and applications. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy, 9(3), 330–338. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B., & Strauss, A. (2017). Discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Golini, R., & Landoni, P. (2014). International development projects by non-governmental organizations: An evaluation of the need for specific project management and appraisal tools. Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal, 32(2), 121–135. [Google Scholar]

- Goulding, C. (1998). Grounded theory: The missing methodology on the interpretivist agenda. Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal, 1(1), 50–57. [Google Scholar]

- Grover, V., Purvis, R. L., & Segars, A. H. (2007). Exploring ambidextrous innovation tendencies in the adoption of telecommunications technologies. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 54(2), 268–285. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, A. K., & Gupta, N. (2019). Innovation and culture as a dynamic capability for firm performance: A study from emerging markets. Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management, 20(4), 323–336. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, D. T., Otazo, K. L., & Hollenbeck, G. P. (1999). Behind closed doors: What really happens in executive coaching. Organizational Dynamics, 27(3), 39–53. [Google Scholar]

- Haverila, M. J., & Haverila, K. C. (2019). Customer centric success measures in project management. International Journal of Business Excellence, 19(2), 203–222. [Google Scholar]

- Heckman, J. J., & Corbin, C. O. (2016). Capabilities and skills. Journal of Human Development and Capabilities, 17(3), 342–359. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Heidhues, P., Kőszegi, B., & Murooka, T. (2016). Exploitative innovation. American Economic Journal: Microeconomics, 8(1), 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Hejna, W. J., & Hosking, J. E. (2004). Five critical strategies for achieving operational efficiency. Journal of Healthcare Management, 49(5), 289–292. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, J. C., & Venkatraman, H. (1999). Strategic alignment: Leveraging information technology for transforming organizations. IBM Systems Journal, 38(2.3), 472–484. [Google Scholar]

- Hennink, M., Hutter, I., & Bailey, A. (2020). Qualitative research methods. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Hisrich, R. D. (1990). Entrepreneurship/intrapreneurship. American Psychologist, 45(2), 209. [Google Scholar]

- Hogan, S. J., & Coote, L. V. (2014). Organizational culture, innovation, and performance: A test of Schein’s model. Journal of Business Research, 67(8), 1609–1621. [Google Scholar]

- Huizingh, E. K. (2011). Open innovation: State of the art and future perspectives. Technovation, 31(1), 2–9. [Google Scholar]

- Ibraimova, S. S., Seisenbaeva, Z. M., Karyakin, A. M., Genkin, E. V., & Velikorossov, V. V. (2019, February 13–15). Teamwork within agile project management technology. International Conference Industrial Technology and Engineering (pp. 235–237), Melbourne, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Jakobsen, B. (2024). Working towards unclear goals: Exploring the concept of social sustainability in a city development project in Oslo, Norway [Master’s Thesis, University of Oslo]. [Google Scholar]

- Jansen, J. J., George, G., Van den Bosch, F. A., & Volberda, H. W. (2008). Senior team attributes and organizational ambidexterity: The moderating role of transformational leadership. Journal of Management Studies, 45(5), 982–1007. [Google Scholar]

- Jansen, J. J., Van den Bosch, F. A., & Volberda, H. W. (2005). Exploratory innovation, exploitative innovation, and ambidexterity: The impact of environmental and organizational antecedents. Schmalenbach Business Review, 57, 351–363. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, R., & Waterfield, J. (2004). Making words count: The value of qualitative research. Physiotherapy Research International, 9(3), 121–131. [Google Scholar]

- Jost, A., Lorenz, T., & Mischke, G. (2005, July 17–21). Modeling the innovation-pipeline. System Dynamics Society Conference, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Sloan School of Management, Cambridge, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, S. J., & Mir, A. A. (2019). Ambidextrous culture, contextual ambidexterity and new product innovations: The role of organizational slack and environmental factors. Business Strategy and the Environment, 28(4), 652–663. [Google Scholar]

- King, N., & Brooks, J. (2018). Thematic analysis in organisational research. In The SAGE handbook of qualitative business and management research methods: Methods and challenges (pp. 219–236). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Kozarkiewicz, A. (2020). General and specific: The impact of digital transformation on project processes and management methods. Foundations of Management, 12(1), 237–248. [Google Scholar]

- Kozcu, G. Y., & Özmen, Ö. (2021). Effects of transformational leadership on organizational change management and organizational ambidexterity. Global Journal of Economics and Business Studies, 10(20), 15–25. [Google Scholar]

- Kraus, S., Jones, P., Kailer, N., Weinmann, A., Chaparro-Banegas, N., & Roig-Tierno, N. (2021). Digital transformation: An overview of the current state of the art of research. Sage Open, 11(3), 21582440211047576. [Google Scholar]

- Laframboise, D., Nelson, R. L., & Schmaltz, J. (2002). Managing resistance to change in workplace accommodation projects. Journal of Facilities Management, 1(4), 306–321. [Google Scholar]

- Larsson, L., & Larsson, J. (2018). Sustainable development in project-based industries–supporting the realization of explorative innovation. Sustainability, 10(3), 683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, P. B. (2023). Determinants of frugal innovation for firms in emerging markets: The roles of leadership, knowledge sharing and collaborative culture. International Journal of Emerging Markets, 18(9), 3334–3353. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C. Y., & Johnson, A. L. (2013). Operational efficiency. In Handbook of industrial and systems engineering, second edition industrial innovation (pp. 17–44). John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Legge, K., & Legge, K. (1995). What is human resource management? (pp. 62–95) Macmillan Education UK. [Google Scholar]

- Lewicki, R. J. (2000). Trust, trust development, and trust repair. In M. Deutsch, & P. T. Coleman (Eds.), The handbook of conflict resolution: Theory and practice (pp. 86–107). Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C., & Chang, C. C. (2015). A patent-based study of the relationships among technological portfolio, ambidextrous innovation, and firm performance. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 27(10), 1193–1211. [Google Scholar]

- Locke, K. (2001). Grounded theory in management research. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, J., Zhou, X., Chen, R., & Dong, X. (2019). Does ambidextrous leadership motivate work crafting? International Journal of Hospitality Management, 77, 159–168. [Google Scholar]

- Majid, M. A. A., Othman, M., Mohamad, S. F., Lim, S. A. H., & Yusof, A. (2017). Piloting for interviews in qualitative research: Operationalization and lessons learnt. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 7(4), 1073–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mårtensson, M. (2000). A critical review of knowledge management as a management tool. Journal of Knowledge Management, 4(3), 204–216. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M. B. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook (Version 2). SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Mohiya, M., & Sulphey, M. M. (2021). Do Saudi Arabian leaders exhibit ambidextrous leadership: A qualitative examination. Sage Open, 11(4), 21582440211054496. [Google Scholar]

- Montes-Guerra, M. I., Gimena, F. N., Pérez-Ezcurdia, M. A., & Díez-Silva, H. M. (2014). The influence of monitoring and control on project management success. International Journal of Construction Project Management, 6(2), 163–184. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, D. L. (1996). Focus groups. Annual Review of Sociology, 22(1), 129–152. [Google Scholar]

- Mrugalska, B., & Ahmed, J. (2021). Organizational agility in industry 4.0: A systematic literature review. Sustainability, 13(15), 8272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, F., Ikram, A., Jafri, S. K., & Naveed, K. (2020). Product innovations through ambidextrous organizational culture with mediating effect of contextual ambidexterity: An empirical study of it and telecom firms. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 7(1), 9. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, C. E. (2009). Diffusion of innovation theory: Abridge for the research-practice gap in counseling. Journal of Counseling & Development, 87(1), 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, R., & Turner, J. R. (2007). Matching the project manager’s leadership style to project type. International Journal of Project Management, 25, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nauman, S., Khan, A. M., & Ehsan, N. (2010). Patterns of empowerment and leadership style in project environment. International Journal of Project Management, 28(7), 638–649. [Google Scholar]

- Nedbal, D., Auinger, A., & Hochmeier, A. (2013). Addressing transparency, communication and participation in Enterprise 2.0 projects. Procedia Technology, 9, 676–686. [Google Scholar]

- Nemanich, L. A., & Vera, D. (2009). Transformational leadership and ambidexterity in the context of an acquisition. The Leadership Quarterly, 20(1), 19–33. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, A., Donohue, R., & Eva, N. (2017). Psychological safety: A systematic review of the literature. Human Resource Management Review, 27(3), 521–535. [Google Scholar]

- Obradovic, V., Jovanovic, P., Petrovic, D., Mihic, M., & Mitrovic, Z. (2013). Project managers’ emotional intelligence–a ticket to success. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 74, 274–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’connor, G. C. (1998). Market learning and radical innovation: A cross case comparison of eight radical innovation projects. Journal of Product Innovation Management: An International Publication of the Product Development & Management Association, 15(2), 151–166. [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell, A. B., Lutfey, K. E., Marceau, L. D., & McKinlay, J. B. (2007). Using focus groups to improve the validity of cross-national survey research: A study of physician decision making. Qualitative Health Research, 17(7), 971–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogbu, J. U. (1992). Understanding cultural diversity and learning. Educational Researcher, 21(8), 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’reilly, C. A., III, & Tushman, M. L. (2008). Ambidexterity as a dynamic capability: Resolving the innovator’s dilemma. Research in Organizational Behavior, 28, 185–206. [Google Scholar]

- Ouchi, W. G., & Wilkins, A. L. (1985). Organizational culture. Annual review of Sociology, 11(1), 457–483. [Google Scholar]

- Özlen, M. K., & Handzic, M. (2020). Ambidextrous organisations from the perspective of employed knowledge management strategies: Evidence from Turkey. Journal of Information & Knowledge Management, 19(2), 2050003. [Google Scholar]

- Padgett, D. K. (2013). Qualitative research. In Encyclopedia of social work. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J., & Park, D. H. (2019). A sustainable project management strategy against multitasking situations from the viewpoints of cognitive mechanism and motivational belief. Sustainability, 11(24), 6912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, S. K., & Skitmore, M. (2005). Project management turnover: Causes and effects on project performance. International Journal of Project Management, 23(3), 205–214. [Google Scholar]

- Pathiranage, Y. L., Jayatilake, L. V., & Abeysekera, R. (2020). A literature review on organizational culture towards corporate performance. International Journal of Management, Accounting & Economics, 7(9), 522–544. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, H. (2019). Organizational ambidexterity in public non-profit organizations: Interest and limits. Management Decision, 57(1), 248–261. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, V., Temouri, Y., Arslan, A., Degbey, W. Y., & Tarba, S. (2022). Ambidextrous organizations in and from emerging markets—Editors’ special issue introduction. Thunderbird International Business Review, 64(5), 101762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pindek, S., & Spector, P. E. (2016). Organizational constraints: A meta-analysis of a major stressor. Work & Stress, 30(1), 7–25. [Google Scholar]

- Pisello, A. L., Pigliautile, I., Andargie, M., Berger, C., Bluyssen, P. M., Carlucci, S., Chinazzo, G., Belafi, Z. D., Dong, B., Favero, M., & Ghahramani, A. (2021). Test rooms to study human comfort in buildings: A review of controlled experiments and facilities. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 149, 111359. [Google Scholar]

- Pollack-Johnson, B., & Liberatore, M. J. (2006). Incorporating quality considerations into project time/cost tradeoff analysis and decision making. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 53(4), 534–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popadiuk, S., Luz, A. R. S., & Kretschmer, C. (2018). Dynamic capabilities and ambidexterity: How are these concepts related? Revista de Administração Contemporânea, 22(5), 639–660. [Google Scholar]

- Powell, R. A., & Single, H. M. (1996). Focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 8(5), 499–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raith, F., Richter, I., & Lindermeier, R. (2017, July 12–14). How project-management-tools are used in agile practice: Benefits, drawbacks and potentials. Proceedings of the 21st International Database Engineering & Applications Symposium (pp. 30–39), Bristol, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Rappaport, A. (2005). The economics of short-term performance obsession. Financial Analysts Journal, 61(3), 65–79. [Google Scholar]

- Rashid, H. (2010). Human factors effects in helicopter maintenance: Proactive monitoring and controlling techniques. Cranfield University. [Google Scholar]

- Rialti, R., Marzi, G., Caputo, A., & Mayah, K. A. (2020). Achieving strategic flexibility in the era of big data: The importance of knowledge management and ambidexterity. Management Decision, 58(8), 1585–1600. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, M., Festa, G., Fiano, F., & Giacobbe, R. (2020). To invest or to harvest? Corporate venture capital ambidexterity for exploiting/exploring innovation in technological business. Business Process Management Journal, 26(5), 1157–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roßnagel, C. S. (2017). Leadership and motivation. In Leadership today: Practices for personal and professional performance (pp. 217–228). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Russo, A., & Vurro, C. (2010). Cross-boundary ambidexterity: Balancing exploration and exploitation in the fuel cell industry. European Management Review, 7(1), 30–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sackmann, S. A. (1991). Uncovering culture in organizations. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 27(3), 295–317. [Google Scholar]

- Salmasnia, A., Mokhtari, H., & Nakhai Kamal Abadi, I. (2012). A robust scheduling of projects with time, cost, and quality considerations. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology, 60, 631–642. [Google Scholar]

- Santoro, G., Thrassou, A., Bresciani, S., & Del Giudice, M. (2019). Do knowledge management and dynamic capabilities affect ambidextrous entrepreneurial intensity and firms’ performance? IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 68(2), 378–386. [Google Scholar]

- Schein, E. H. (2010). Organizational culture and leadership (Vol. 2). John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, C. (2004). The analysis of semi-structured interviews. In A companion to qualitative research (p. 253). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Scott-Young, C., & Samson, D. (2008). Project success and project team management: Evidence from capital projects in the process industries. Journal of Operations Management, 26(6), 749–766. [Google Scholar]

- Selden, L., & MacMillan, I. C. (2006). Manage customer-centric innovation-systematically. Harvard Business Review, 84(4), 108. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shaout, A., & Yousif, M. K. (2014). Performance evaluation–Methods and techniques survey. International Journal of Computer and Information Technology, 3(5), 966–979. [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan, M., Garavan, T. N., & Morley, M. J. (2023). The microfoundations of dynamic capabilities for incremental and radical innovation in knowledge-intensive businesses. British Journal of Management, 34(1), 220–240. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Y., Tuuli, M. M., Xia, B., Koh, T. Y., & Rowlinson, S. (2015). Toward a model for forming psychological safety climate in construction project management. International Journal of Project Management, 33(1), 223–235. [Google Scholar]

- Shenhar, A. J. (1998). From theory to practice: Toward a typology of project-management styles. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 45(1), 33–48. [Google Scholar]

- Shenhar, A. J. (2004). Strategic Project Leadership® Toward a strategic approach to project management. R&D Management, 34(5), 569–578. [Google Scholar]

- Sijbom, R. B., Janssen, O., & Van Yperen, N. W. (2016). Leaders’ achievement goals and their integrative management of creative ideas voiced by subordinates or superiors. European Journal of Social Psychology, 46(6), 732–745. [Google Scholar]

- Silver, W. S., & Mitchell, T. R. (1990). The status quo tendency in decision making. Organizational Dynamics, 18(4), 34–46. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman, D. (2006). Interpreting qualitative data: Methods for analyzing talk, text and interaction. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Simeoni, F., Brunetti, F., Mion, G., & Baratta, R. (2020). Ambidextrous organizations for sustainable development: The case of fair-trade systems. Journal of Business Research, 112, 549–560. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, B. G. (2012). Communication integration: An analysis of context and conditions. Public Relations Review, 38(4), 600–608. [Google Scholar]

- Stokes, D., & Bergin, R. (2006). Methodology or “methodolatry”? An evaluation of focus groups and depth interviews. Qualitative market research: An international Journal, 9(1), 26–37. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, A. (1987). Qualitative analysis for social scientists. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research: Procedures and technique for developing grounded theory. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Tampoe, M., & Thurloway, L. (1993). Project management: The use and abuse of techniques and teams (reflections from a motivation and environment study). International Journal of Project Management, 11(4), 245–250. [Google Scholar]

- Tavakol, M., & Dennick, R. (2011). Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. International Journal of Medical Education, 2, 53. [Google Scholar]

- Terzieva, M. (2014). Project knowledge management: How organizations learn from experience. Procedia Technology, 16, 1086–1095. [Google Scholar]

- Tobin, G. A., & Begley, C. M. (2004). Methodological rigour within a qualitative framework. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 48(4), 388–396. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tsai, M. C., & Wang, C. (2017). Linking service innovation to firm performance: The roles of ambidextrous innovation and market orientation capability. Chinese Management Studies, 11(4), 730–750. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, M., & Lingard, H. (2016). Improving workers’ health in project-based work: Job security considerations. International Journal of Managing Projects in Business, 9(3), 606–623. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, N., Maylor, H., & Swart, J. (2015). Ambidexterity in projects: An intellectual capital perspective. International Journal of Project Management, 33(1), 177–188. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, N., Swart, J., Maylor, H., & Antonacopoulou, E. (2016). Making it happen: How managerial actions enable project-based ambidexterity. Management Learning, 47(2), 199–222. [Google Scholar]

- Vygotsky, L. (2011). Interaction between learning and development (pp. 79–91). Linköpings Universitet. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, D., & Myrick, F. (2006). Grounded theory: An exploration of process and procedure. Qualitative Health Research, 16(4), 547–559. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C. L., & Rafiq, M. (2014). Ambidextrous organizational culture, Contextual ambidexterity and new product innovation: A comparative study of UK and Chinese high-tech Firms. British Journal of Management, 25(1), 58–76. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S., & Noe, R. A. (2010). Knowledge sharing: A review and directions for future research. Human Resource Management Review, 20(2), 115–131. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y., Farag, H., & Ahmad, W. (2021). Corporate culture and innovation: A tale from an emerging market. British Journal of Management, 32(4), 1121–1140. [Google Scholar]

- Wassmer, U., Li, S., & Madhok, A. (2017). Resource ambidexterity through alliance portfolios and firm performance. Strategic Management Journal, 38(2), 384–394. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, G. (1971). Resistance to change. American Behavioral Scientist, 14(5), 745–766. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, M. (2023). Bureaucracy. In Social theory re-wired (pp. 271–276). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Weston, C., Gandell, T., Beauchamp, J., McAlpine, L., Wiseman, C., & Beauchamp, C. (2001). Analyzing interview data: The development and evolution of a coding system. Qualitative Sociology, 24, 381–400. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, X., & Wang, H. (2021). How to bridge the gap between innovation niches and exploratory and exploitative innovations in open innovation ecosystems? Journal of Business Research, 124, 299–311. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, M., Wang, J., & Zhang, X. (2021). Boundary-spanning search and sustainable competitive advantage: The mediating roles of exploratory and exploitative innovations. Journal of Business Research, 127, 290–299. [Google Scholar]

- Zein, O. (2016). Culture and project management: Managing diversity in multicultural projects. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W., Zeng, X., Liang, H., Xue, Y., & Cao, X. (2023). Understanding how organizational culture affects innovation performance: A management context perspective. Sustainability, 15(8), 6644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X., Le, Y., Liu, Y., & Chen, X. (2021). Fostering ambidextrous innovation strategies in large infrastructure projects: A team heterogeneity perspective. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 70, 2257–2267. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z., & Luo, T. (2020). Network capital, exploitative and exploratory innovations—From the perspective of network dynamics. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 152, 119910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K., Hua, J., Yan, L., Zhang, Q., Xu, H., & Yang, C. (2019, August 4–8). A unified framework for marketing budget allocation. Proceedings of the 25th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining (pp. 1820–1830), Anchorage, AK, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z., Zang, Y., Luo, X., Lan, Y., & Xue, X. (2013). Technology innovation development strategy on agricultural aviation industry for plant protection in China. Transactions of the Chinese Society of Agricultural Engineering, 29(24), 1–10. [Google Scholar]

| No | Designation | Sample |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Executives Directors/CEO | 5 |

| 2. | Project Managers | 19 |

| 3. | Project team members | 12 |

| S.No | Type of Organizations | Type of Ownership | Size |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Government authorities | State-Owned | Small |

| 2. | Industrial and manufacturing | State-Owned | Large |

| 3. | Construction | State-Owned | Large |

| 4. | Consulting services | Semi-Government | Small |

| 5. | Energy | State-Owned | Large |

| 6. | University | State-Owned/Semi-Government | Small |

| 7. | Information Technology | Semi-Government | Large |

| No | Designation | Number | Organizations |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | CEO/Director | 2 | Public Sector Organizations |

| 2. | Project Managers/Directors | 4 | Public and Semi-Government |

| 3. | Academic expert | 1 | University–Public Sector |

| Metric | Value |

|---|---|

| Total Observations | 100 |

| Observed Agreements | 93 |

| Expected Agreements | 75.86 |

| Disagreements | 7 |

| Observed Agreement Rate | 93% |

| Cohen’s Kappa | 0.71 |

| Expected Agreement Rate | 76% |

| No | Aspects | Participant’s Point of View | Theoretical Definitions |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Allocated Budget | To operate projects effectively, a sizable budget must be allotted. Without it, workers frequently feel constrained in their ability to consider alternatives or put creative ideas into practice. Additionally, an adequate budget can demonstrate management’s dedication to the mission. | The allocated budget can be defined as the amount of financial, human, and other resources that are allocated to a particular project in a firm (Zhao et al., 2019). |

| 2 | Adequate Project Time | In order to achieve high-quality results, projects need time. Rushing and completing tasks before the required time can cause overlooking important information, which results in errors. | The maximum time for the entire project deliverables to be completed, as agreed upon between the client and project organization (Babu & Suresh, 1996). |

| 3 | Effective Time management | Time management skills are essential, particularly for initiatives with a lot of pressure. Employees can better balance their workload, maintain their attention, and prevent work from being completed at the last minute, which reduces its quality. | Effective time management refers to utilizing time in order to enhance the overall efficiency and effectiveness of teams (Atkinson, 1999). |

| 4 | Experimental Space | Creativity and innovation are greatly enhanced by having a dedicated area or space for idea experimentation. Such a dedicated space can motivate employees, and employees may attempt new things without worrying about failing, which can inspire them to be more adventurous and creative. | A space dedicated to discussing, sharing, and refining new ideas and converting these ideas into actual products and services (Pisello et al., 2021). |

| 5 | Lack of Knowledge and Experience | Employees may feel apprehensive if they lack sufficient expertise or experience in certain fields or areas. This frequently slows down the process and might be annoying. To close these gaps, organizations can focus on various things, such as training and development. | The knowledge, skills, and expertise required to make changes to existing products or develop completely new products that help firms to bring and sustain their competitive advantage (Terzieva, 2014). |

| 6 | Expertise Support | Having experts in the team who can easily be approached and consulted has a significant positive impact. Their advice increases confidence in their choices and expedites the process of resolving issues. It is comforting to have such assistance. | The support that various teams in an organization require in order to solve complex problems (Gillard, 2009). |

| 7 | Language Barriers | Effective communication can occasionally be hampered by language barriers. Misunderstandings occur and have an impact on teamwork. It would be really beneficial if employees could get better support or enhance their language abilities. | The inability of the team and its members to communicate in the language of the communication at the organization (Anderson et al., 2018). |

| 8 | Past Attitudes Reflection | The ability to respond to novel and important internal and external events and circumstances is heavily influenced by the ability to reflect on past behavior and attitudes. If employees do not reflect, it may be the case that teams are being held back by outdated views, particularly when they are unfavorable to the organization’s progress. | The ability of teams and members of an organization to reflect on the various behavioral patterns, which are both predictors of success and failure in the organization (Hall et al., 1999). |

| 9 | Sensitivity to Criticism | It can be difficult to accept criticism, particularly when it is unhelpful. It might feel personal at times, which lowers morale. It would be difficult to progress with employees feeling disheartened at the workplace. | The inability of the team to listen to and incorporate critical feedback received from members of the team, including both senior and junior levels (Gibson & Mumford, 2013). |

| 10 | Fear of Failure | People frequently refrain from trying new things because they are afraid of failing. Employees are concerned about what will happen if things do not work out. It would be very beneficial to have a culture that views failure as a teaching opportunity. | The behavior, which can be defined as risk-averse, occurs when teams and members of the organization are unwilling to test new ideas out of fear that the new idea will fail and members of such teams will be held responsible (Dunbar & Guillet de Monthoux, 1979). |

| 11 | Infrastructure and Tools | Having the proper infrastructure and equipment is crucial to performing the tasks effectively. Organizations and teams cannot perform effectively in the absence of these tools. | The physical infrastructure, which includes both hardware and software, is necessary for streamlining various activities, which results in varying kinds of innovations (Raith et al., 2017). |

| 12 | Empowerment from Leadership | Employees’ confidence and readiness to take the initiative are increased when they feel empowered by the leadership. Teams and employees are more committed to a project’s success when leaders have faith in their ability to make judgments. | The motivation and autonomy provided by leaders and managers encourage employees to seek out new ideas for both exploration and exploitation (Nauman et al., 2010). |

| 13 | Expertise Utilization | There has to be a proper system of approaching experts and utilizing their expertise at the right time and in the right situation. Such expertise utilization is significantly important in that it directly contributes to innovations. | The ability and willingness of teams and members to utilize their skills for both exploration and exploitation (Gillard, 2009). |

| 14 | Psychological Safety in Teams | For teams and organizations to freely exchange ideas, they must feel psychologically secure. Teams are more inclined to actively participate when teams are assured that they will not be condemned. Teams are always strengthened by such safety. | Psychological safety in teams refers to an environment where members feel safe to take risks, express their thoughts, and share ideas without the fear of negative consequences (Newman et al., 2017). |

| 15 | Evaluation Impact | Instead of concentrating only on the procedure, it is critical to assess how the team’s efforts affect the business. Being aware of the results of our work gives a sense of accomplishment and aids in strategy improvement. | Evaluation impact refers to the effects that assessments, feedback, or performance evaluations have on individuals, teams, or organizations (Gertler et al., 2016). |

| 16 | Emotional Intelligence of Managers | A better work atmosphere is produced by managers who possess emotional intelligence. They communicate in a helpful manner and are aware of employees’ difficulties. This facilitates managing stress at work. | Emotional intelligence is the ability of managers to effectively regulate their emotions by understanding, using, and managing their own emotions, as well as the emotions of others (Dulewicz & Higgs, 2000). |

| 17 | Job Security | Concentrating on the work without worrying about being laid off at any time gives employees and teams the confidence to complete their tasks effectively. When people are worried about losing their jobs, it becomes more and more difficult to think creatively and innovate. Having a stable job provides employees with drive and peace of mind. | Job security can be defined as the likelihood that an employee will keep their job and not be laid off or fired under any circumstances (A. Clark & Postel-Vinay, 2009). |

| 18 | Management Styles | The ability to collaborate is impacted by various management philosophies. An authoritarian management style might inhibit innovation, whereas a collaborative or democratic style promotes cooperation. When managers modify their approach to fit the demands of the team, it is beneficial. | The management style is defined as the approach of a leader or manager in an organization to guide a team toward shared goals (Claes, 1999). |

| 19 | Juniors’ Ideas Ignored | When suggestions, ideas, and input from younger and junior team members are disregarded without thought, it is frustrating. Sometimes, the solution to an issue requires new viewpoints. Juniors need to be appreciated and can contribute to fresh ideas when they are given a voice. | The behavior in the teams where ideas presented by junior members of teams are not given proper attention (Sijbom et al., 2016). |

| 20 | Motivation for Creativity and Development | The teams stay motivated when they are encouraged to be innovative and advance in their positions. It is simpler to remain involved and contribute fresh ideas when the team appreciates and encourages employee growth. | The internal drive of members of a team to search for new ideas that can be used for both exploration and exploitation (Ma et al., 2019). |

| 21 | Change Resistance | Because change is unsettling and unpredictable, employees frequently oppose it. It is easy to feel overburdened in the absence of adequate assistance. This resistance is lessened during changes when there is clear communication and direction. | The willingness of team members to resist any sort or kind of change within teams and organizations (Laframboise et al., 2002). |

| 22 | Theoretical vs. Practical Disconnect | There are instances when theory and practice diverge, which can cause misunderstandings. To make the work seem more relevant to actual circumstances, it would be beneficial if we could figure out how to close this gap. | The perceived gap between theories or concepts of innovation and their effective application in real-world situations, which can result in challenges in implementation and understanding (Murray, 2009). |

| 23 | Policy Barriers | Effective work completion and innovation are often hampered by the policies of organizations. These policies may seem out of date or restrictive. Such policies need to be adjusted to respond to the demands of the increasing evolution within the organization. | The official rules and regulations of the organization that make it very difficult to acquire new knowledge and experiment with ideas for both improving existing and developing new products and services (Shenhar, 2004). |

| 24 | Bureaucracy | Bureaucratic procedures and policies always cause needless delays and impediments. Overly lengthy processes are annoying and reduce productivity. Efficiency might be significantly improved by cutting back on bureaucracy. | A system of administration characterized by strict rules, hierarchical organization, and standardized procedures, typically used in large institutions or government bodies to ensure efficiency and accountability (Weber, 2023) |

| 25 | Leadership Engagement | Active engagement by leaders demonstrates their concern for the project. It helps employees to stay focused and provides appropriate direction for various things, such as creativity and innovations. Additionally, their participation gives employees the impression that their jobs, work, and creativity are valued. | The active involvement and commitment of leaders in guiding, motivating, and influencing their teams or organizations, fostering collaboration and alignment toward shared goals (Decuypere & Schaufeli, 2021). |

| 26 | Documentation System | A well-structured documentation system is necessary to monitor the team and organization’s activity. Incomplete or difficult-to-locate records are annoying. Various aspects of operations would be easier, and time would be saved with a more efficient system. | A structured approach for creating, managing, and storing documents and records, ensuring accessibility, consistency, and compliance within an organization (Eloranta et al., 2001). |

| 27 | Clear Deliverables and Metrics | Teams can better grasp expectations if they have well-defined objectives and measurements. It is difficult to gauge progress when objectives are unclear. Having specific goals helps the organization’s members stay motivated and in sync to achieve them. | Specific, measurable outcomes and criteria established to evaluate the success of a project or initiative, providing clarity on expectations and enabling effective performance assessment (Müller & Turner, 2007). |

| 28 | Unclear Objectives and Goals | Employees and teams can become confused and move more slowly when the overall goals are unclear. In the end, teams will waste time attempting to determine the priorities rather than doing actual work. | Unclear objectives and goals can be defined as vague or poorly defined targets that hinder understanding of desired outcomes, making it difficult for individuals or teams to align their efforts and measure success effectively (Jakobsen, 2024). |

| 29 | Evaluation Performance Review system | The efforts of teams and individuals should be fairly evaluated by an appropriate and effective performance evaluation system. It is discouraging when assessments and performance evaluation systems are highly inconsistent with employees’ and teams’ efforts. | A structured process for assessing employee performance and productivity, typically involving regular feedback, goal setting, and documentation to facilitate development, accountability, and organizational growth (Shaout & Yousif, 2014). |

| 30 | Operational Efficiency | Everyone’s work is made easier by increasing operational efficiency. It saves time and cuts down on redundancy. Without wasting resources, a more efficient procedure would enable the employees to produce superior outcomes. | Operational efficiency is defined as the ability of a team to deliver products or services in the most cost-effective and efficient manner while at the same time maximizing productivity (Lee & Johnson, 2013). |

| 31 | Emphasis on Time Over Quality | Sometimes, employees have to compromise on quality in order to meet timelines. It seems like a compromise that could lessen the effect of employees’ and teams’ efforts. | The willingness of the team to sacrifice quality of products and services by producing them in a shorter time (Salmasnia et al., 2012). |

| 32 | Workload Pressure | Stress and burnout are caused by heavy workloads. Having too much work on the employee’s schedule can significantly diminish motivation. | Workload pressure is defined as excessive tasks assigned to the team and its members that are beyond their capacity (Chen et al., 2017). |

| 33 | Tension Between Exploration and Exploitation | For sustained ambidextrous innovation, it is significantly important that the organization ought to have a balance between exploration and exploitation activities of innovations. | The paradox of innovation in which organizations must find a way to balance improvements in existing products and services while at the same time creating new products and services (AlSaied & McLaughlin, 2024a, 2024b). |

| 34 | Radical Innovation Momentum | For an organization to stay ahead of its competitors, radical invention is needed. However, this can also have some drawbacks, such as taking risks that may lead to various losses, both financial and non-financial. | The quest of the organization/firm to undertake radical and new innovations that can help it develop a competitive advantage (O’connor, 1998). |

| 35 | Pressure to Keep Up with Competitors | The current competitive environment in the market creates pressure to keep up with the market trends. One of the key strategies for success is continuous and successful innovation in the market. | Market pressure which pushes teams to match their competitors through various tactics and strategies, such as pricing, supply chain, and products and services (I. Clark, 1998). |

| 36 | Turnover and Instability | Projects are slowed down, and team stability is impacted by high turnover. Building momentum is difficult when team members are always changing. Establishing a steady workplace might increase our output. | A higher ratio of new employees leaving the organization after joining. Such a higher ratio may create an unstable organizational environment (Parker & Skitmore, 2005). |

| 37 | Flat Organizational Structure | Cross-level communication and idea-sharing are facilitated by a flat organizational structure. Employees and teams can feel more appreciated and less threatened. However, occasionally, a little more hierarchy might aid in clarity. | Type of organizational structure that is characterized by fewer hierarchical levels (Ghiselli & Siegel, 1972). |

| 38 | Roles and Responsibilities | Roles and duties that are well-defined help to avoid misunderstandings. It is easier to work together when employees and teams are aware of their precise responsibilities and it helps to avoid overlap. | A role is a person’s position or job title within a company or team, while responsibilities are the specific tasks and duties associated with that role (J. K. Crawford et al., 2004). |

| 39 | Knowledge Share | Employees may learn from one another when teams share expertise and knowledge. It expedites problem-solving and fosters a sense of teamwork. | The activity within the organization in which team members share their knowledge, expertise, and skill with other members routinely (S. Wang & Noe, 2010). |

| 40 | Short-Term Focus | The teams’ and employees’ capacity to make future plans may be hampered by short-term emphasis and orientations. Therefore, teams must find a balance between short-term outcomes and long-term objectives. | The strategy and type of organization that tends to focus on short-term gains while sacrificing long-term goals and objectives (Rappaport, 2005). |

| 41 | Teamwork and Leadership Attitude | A healthy work culture is fostered when leaders encourage cooperation. Knowing that efforts are appreciated is encouraging. Collaboration among the team is also strengthened by effective leadership. | Teamwork refers to the collaborative efforts in which members leverage skills and knowledge to achieve goals, while a positive leadership attitude inspires and guides the team, characterized by traits like empathy, decisiveness, and accountability (Ibraimova et al., 2019). |

| 42 | Productivity Monitoring | Employees may be held accountable through productivity tracking and monitoring, but occasionally, it comes off as micromanagement. It would be better to have a system that relies on employees to deliver while providing direction as required. | Productivity monitoring can be referred to as the systematic approach of tracking and monitoring the performance of both individuals and teams performance (Alaloul et al., 2022). |

| 43 | Project Testing and Monitoring | Project testing and monitoring initiatives aid in the early detection of problems. They make employees more confident about the finished tasks and outcomes. Employees could satisfy requirements and cut down on mistakes with more regular monitoring. | Project testing and monitoring can be defined as structured activities that are necessary for ensuring that projects are being completed on time, within budget, and according to stakeholder requirements (P. Crawford & Bryce, 2003). |

| 44 | Trust Development | Although it takes time, developing trust among the team is crucial for productive cooperation. Team members can collaborate more freely when they have mutual trust. Progress would be aided by further team-building exercises. | Trust development can be defined as the activities undertaken by the members of an organization to develop trust among themselves through various formal and informal channels of communication (Lewicki, 2000). |

| 45 | Innovation Development–Innovation Interests | It is inspiring to have freedom and room to pursue interests in innovation. When the company fosters such interest, it is fantastic and encouraging for individuals to be creative by contributing to the original ideas. | Innovation development can be defined as the structured process of generating, refining, and implementing new ideas for the development of products, services, and processes that create value and competitive advantage (Zhou et al., 2013). |

| 46 | Cross-Functional Collaboration | Working together across departments gives a variety of knowledge and expertise. It results in more thorough solutions to a variety of complex problems. To encourage this, teams would benefit from more organized cross-team projects. | The ability of various and different team members to collaborate cross-functionally within the organization with the aim of bringing new ideas for exploration and exploitation (Bishop, 1999). |

| 47 | Cultural Diversity | Cultural diversity in teams encourages creativity and broadens perspectives. Collaborating with individuals from diverse backgrounds is motivating. Employees had a pleasant experience because of the respect and open-mindedness. | The ability and willingness of teams and organizations to appreciate the different cultures of various team members and to create a values system that celebrates diversity (Ogbu, 1992). |

| 48 | Entrepreneurship | For innovation and success over a longer period of time, it is necessary that employees have an entrepreneurial mindset. It is necessary because an entrepreneurial mindset inculcates the spirit of developing new ideas, taking risks, and other innovative actions. | Entrepreneurship encouragement is defined as the empowerment and motivation within an organization to become entrepreneurial (Hisrich, 1990). |

| 49 | Reward Systems | A system of rewards encourages employees to work harder. When effort is rewarded, it is uplifting. To preserve systemic trust, rewards must be equitable and constant. | The system of compensation in which employees are rewarded based on various key performance metrics such as target accomplishment, sales and revenue increases, and others (Francis et al., 2020). |

| 50 | Innovation Pipeline | An innovation pipeline guarantees that new ideas are taken into consideration and keeps them flowing. Seeing a methodical approach to concept development is encouraging. Employees can monitor the development of concepts from ideation to execution with the aid of a well-defined pipeline. | The innovation pipeline refers to an organization’s plan for undertaking various innovations within a specified time period (Jost et al., 2005). |

| 51 | Customer-Centric Innovation | Employees may provide pertinent products by concentrating on the demands of the customers. Knowing that innovation efforts directly affect consumers’ feelings and level of satisfaction, it is better to always gather data and information on consumers as input. | The type of innovation in which customer inputs, needs, and demands take center-stage in developing new products and services (Selden & MacMillan, 2006). |

| 52 | Open Innovation | Open innovation introduces new viewpoints from outside the company, and it can result in organizations becoming and remaining both innovative and competitive. Employees would have a more comprehensive understanding of industry trends as a result of open innovations. | Open innovation can be defined as a strategy that encourages teams to use internal and external resources, ideas, and technologies to develop their products and services (Huizingh, 2011). |

| 53 | Digital Transformation | Digital transformation might be difficult, but it is essential to remain relevant. It takes time to learn new tools, such as GenAI and others. Employees could adjust more readily if we had support during these changes. | Digital transformation can be defined as the process of using digital technologies to change business operations, which includes customer handling (Kraus et al., 2021). |

| 54 | Learning and Development | Learning and development opportunities keep teams and organizations more interested and competent in various key areas. The company’s investment in learning and development through training can demonstrate its importance for employees. Frequent training would enable them to stay abreast of developments in the industry. | Learning and development can be defined as the systematic approach of enhancing the skills, knowledge, and competencies of the teams within an organization, enabling them to carry out innovation (Vygotsky, 2011). |

| 55 | Organizational Agility | Being flexible enables employees to react swiftly to obstacles and changes. When a company can adjust effectively, it is inspiring. The capacity to respond to evolving needs would be improved with more process flexibility. | The organization’s ability to rapidly adapt and change according to the changing landscape of the external environment (Mrugalska & Ahmed, 2021). |

| 56 | Strategic Alignment | Being in line with the organization’s plan helps employees and teams feel like they have some real purpose. Knowing that employees’ aims contribute to the larger picture makes achieving them simpler. Frequent strategy updates help them stay motivated and focused. | Strategic alignment is the process of ensuring that an organization’s resources, activities, and initiatives are in sync with its overall goals and objectives (Henderson & Venkatraman, 1999). |

| No | Aspects | Literature | Frequency (Respondents) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Allocated Budget | (Zhao et al., 2019) | 10 |

| 2 | Adequate Project Time | (Babu & Suresh, 1996) | 12 |

| 3 | Tight Timeline Constraints | (Pollack-Johnson & Liberatore, 2006) | 13 |

| 4 | Effective Time Management | (Atkinson, 1999) | 13 |

| 5 | Experimental Space | (Pisello et al., 2021) | 11 |

| 6 | Lack of Knowledge and Experience | (Terzieva, 2014) | 7 |

| 7 | Expertise Support | (Gillard, 2009) | 18 |

| 8 | Language Barriers | (Anderson et al., 2018) | 8 |

| 9 | Past Attitudes Reflection | (Hall et al., 1999) | 12 |

| 10 | Sensitivity to Criticism | (Gibson & Mumford, 2013) | 14 |

| 11 | Fear of Failure | (Dunbar & Guillet de Monthoux, 1979) | 10 |

| 12 | Infrastructure and Tools | (Raith et al., 2017) | 10 |

| 13 | Empowerment from Leadership | (Nauman et al., 2010) | 30 |

| 14 | Expertise Utilization | (Gillard, 2009) | 16 |

| 15 | Psychological Safety in Teams | (Shen et al., 2015) | 28 |

| 16 | Feedback Transparency | (Nedbal et al., 2013) | 15 |

| 17 | Evaluation Impact | (Golini & Landoni, 2014) | 17 |

| 18 | Emotional Intelligence of Managers | (Obradovic et al., 2013) | 26 |

| 19 | Job Security | (M. Turner & Lingard, 2016) | 16 |

| 20 | Management Styles | (Shenhar, 1998) | 19 |

| 21 | Contentment with Status Quo | (Silver & Mitchell, 1990) | 14 |

| 22 | Juniors’ Ideas Ignored | (Sijbom et al., 2016) | 13 |

| 23 | Motivation for Creativity and Development | (Tampoe & Thurloway, 1993) | 29 |

| 24 | Change Resistance | (Laframboise et al., 2002) | 17 |

| 25 | Theoretical vs. Practical Disconnect | (Murray, 2009) | 12 |

| 26 | Policy Barriers | (Shenhar, 2004) | 11 |

| 27 | Bureaucracy | (Shenhar, 2004) | 9 |

| 28 | Leadership Engagement | (Nauman et al., 2010) | 27 |

| 29 | Documentation System | (Eloranta et al., 2001) | 8 |

| 30 | Clear Deliverables and Metrics | (Müller & Turner, 2007) | 22 |

| 31 | Unclear Objectives and Goals | (Müller & Turner, 2007) | 12 |

| 32 | Evaluation Performance Review System | (Golini & Landoni, 2014) | 15 |

| 33 | Operational Efficiency | (Hejna & Hosking, 2004) | 12 |

| 34 | Emphasis on Time Over Quality | (Salmasnia et al., 2012) | 11 |

| 35 | Workload Pressure | (Chen et al., 2017) | 9 |

| 36 | Tension Between Exploration and Exploitation | (N. Turner et al., 2015) | 18 |

| 37 | Radical Innovation Momentum | (O’connor, 1998) | 17 |

| 38 | Pressure to Keep Up with Competitors | (I. Clark, 1998) | 13 |

| 39 | Turnover and Instability | (Parker & Skitmore, 2005) | 9 |

| 40 | Flat Organizational Structure | (Burford, 2012) | 8 |

| 41 | Roles and Responsibilities | (J. K. Crawford et al., 2004) | 14 |

| 42 | Knowledge Share | (Terzieva, 2014) | 20 |

| 43 | Short-Term Focus | Not Found | 13 |

| 44 | Recruitment Process | (Ahsan et al., 2013) | 14 |

| 45 | Ineffective Multi-Tasking | (Park & Park, 2019) | 11 |

| 46 | Teamwork and Leadership Attitude | (Ibraimova et al., 2019) | 29 |

| 47 | Productivity Monitoring | (Alaloul et al., 2022) | 15 |

| 48 | Project Testing and Monitoring | (Montes-Guerra et al., 2014) | 10 |

| 49 | Trust Development | (Bond-Barnard et al., 2018) | 28 |

| 50 | Innovation Development–Innovation Interest | (O’connor, 1998) | 18 |

| 51 | Cross-Functional Collaboration | (Bishop, 1999) | 26 |

| 52 | Cultural Diversity | (Zein, 2016) | 15 |

| 53 | Adaptability to Change | (Conforto et al., 2016) | 26 |

| 54 | Reward Systems | (Ahsan et al., 2013) | 21 |

| 55 | Innovation Pipeline | (O’connor, 1998) | 19 |

| 56 | Customer-Centric Innovation | (Haverila & Haverila, 2019) | 16 |

| 57 | Open Innovation | (Bagherzadeh et al., 2019) | 14 |

| 58 | Digital Transformation | (Kozarkiewicz, 2020) | 11 |

| 59 | Learning and Development | (Terzieva, 2014) | 19 |

| 60 | Organizational Agility | (Conforto et al., 2016) | 18 |

| 61 | Intrapreneurship Encouragement | Not Found | 20 |

| 62 | Strategic Alignment | (Ershadi et al., 2020) | 24 |

| Theme | Aspects | Definition | Participant’s Perspective |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resource Management: | Allocated Budget, Adequate Project Time, Effective Time Management, Infrastructure and Tools, Documentation System, Operational Efficiency, Emphasis on Time Over Quality, Workload Pressure | Resource management refers to effectively and efficiently managing existing resources with the aim of creating value for their customers. Resource management has various key aspects that are related to both physical or hard resources and soft resources, such as skills, motivation, and attitudes (Legge & Legge, 1995). | The foundation of employee and organizational productivity is effective resource management. We (employees) need to feel prepared to do things without worrying about the appropriate amount of resources, such as equipment, time, and financial resources. An organization can perform at its best when there is a well-structured system that strikes a balance between timelines and quality standards. If an organization does not achieve such balance, it can risk burnout and losing out on strategic opportunities. |

| Skills and Capabilities | Lack of Knowledge and Experience, Expertise Support, Expertise Utilization, Knowledge Share, Learning and Development, Trust Development | The skills and capabilities, which are dynamic in nature, refer to various key aspects, such as knowledge, skills, and expertise, required to undertake innovation in general and ambidextrous innovation in specific (Heckman & Corbin, 2016). | The organization’s ability to contribute to new innovation and adjust to the changing market environment is determined by a set of critical skills and capabilities. Therefore, having access to support networks for sharing knowledge and gaining skills is very important for such a set of skills and capabilities. The organization needs to become more confident and involved in roles that provide an opportunity for growth in skills and capabilities. Thus, by consistently enhancing skills, the organization not only becomes better but also creates and retains a strategic competitive advantage for the longer term. |

| Leadership and Motivation | Empowerment from Leadership, Emotional Intelligence of Managers, Motivation for Creativity and Development, Leadership Engagement, Reward Systems | The themes of leadership and motivation are defined as behavioral and inner derives that push teams to seek new ideas for ambidextrous innovations (Roßnagel, 2017). | Leaders who are emotionally intelligent and supportive have a discernible impact on the productivity of employees. The employees become more motivated and dedicated when leaders empower employees and genuinely appreciate their work. We, as employees, feel proud and motivated when our efforts are valued. This encouraging atmosphere is further reinforced by a compensation structure that is in line with employees’ efforts and motivates them to go above and beyond their normal responsibilities. |

| Resistance to Change and Status Quo—(Change management and behavior patterns) | Change Resistance, Adaptability to Change, Cultural Diversity, Roles and Responsibilities, Short-Term Focus, Bureaucracy | Resistance to change and maintenance of the status quo refers to behaviors and attitudes that restrict any change, as such change is perceived to be very difficult to implement, and it can significantly threaten the status quo and the authorities of concerned people (Watson, 1971). | Although resistance to change is common, it is necessary for development and adaptability in the fast-paced world of today. Although short-term objectives and bureaucracy might occasionally impede our (employees) development, many viewpoints within the team help us in the ability to adjust to change. This shift can be facilitated by clearly defined roles and duties that offer a solid foundation. When the company helps employees at every stage, embracing change becomes easier to handle. |

| Vision and Mission | Vision and Mission, Strategic Alignment, Clear Deliverables and Metrics, Unclear Objectives and Goals | The vision and mission refer to the strategic management of the teams and organizations that tend to develop long-term competitive positions in the competitive market and such positions’ relevancy for the strategic innovation of ambidexterity (Foreman, 1998). | A strong feeling of purpose always comes from aligning ourselves with the organization’s vision and mission. The employees become more motivated and involved when they see their jobs and work are related to the bigger mission and vision. However, an ambiguous and unclear mission and vision cause misunderstandings, which may lead to inefficiency. Employees can contribute more effectively when they stay focused and communicate the company’s vision and strategic goals on a regular basis. |

| Organizational constraints | Organizational Constraints, Policy Barriers, Flat Organizational Structure, Turnover and Instability, Pressure to Keep Up with Competitors | The organization constraints theme refers to the various hurdles and constraints that members of teams have to face in order to carry out innovation. These constraints can be strategic (such as lack of vision, mission, bureaucracy, and others) and tactical (such as lack of operation efficiency, etc.) (Pindek & Spector, 2016). | The organization’s efficiency and effectiveness may be hampered by organizational constraints such as strict policies, intricate systems, and others. Employees, once they start feeling constrained by rules, may be perceived as infuriating. Thus, it causes instability in the organization, leading to higher turnover in the organization. Resolving these problems could result in a more steady, concentrated workplace where employees can give their full effort to their tasks. |

| Exploration and Exploitation Boundaries | Exploration and Exploitation Boundaries, Tension Between Exploration and Exploitation, Radical Innovation Momentum, Innovation Pipeline, Customer-Centric Innovation, Open Innovation | Ambidextrous innovation refers to paradoxical, in which both exploration and exploitation are considered opposites but complementary to each other. In the current themes, we tend to explore the way in which boundaries for each activity, i.e., exploration and exploitation, can be fixed so that it is possible to separate them while still allowing for overlapping activities (Russo & Vurro, 2010). | Sustainable and strategic innovation in the organization requires striking a balance between developing new concepts and improving the current methods. Our (employees) job feels exciting and forward-thinking when we have room to investigate customer-focused solutions and make bold proposals. However, it is crucial to have precise rules about when and how we can take these innovative opportunities. Employees could maintain competitiveness and alignment with objectives by striking a balance between radical innovation and operational effectiveness. |

| Team Management | Team Management, Psychological Safety in Teams, Juniors’ Ideas Ignored, Teamwork and Leadership Attitude, Project Testing and Monitoring, Cross-Functional Collaboration | Effective team management refers to the development, integration, and cohesiveness of the teams to carry out new and radical innovations that can help a firm achieve a strategic position in the market (Scott-Young & Samson, 2008). | Team management and dynamics have a big impact on how employees work together and fulfill the stakeholders’ demands. Prioritizing psychological safety allows the employees to express their thoughts and concerns without worrying about being judged. Even for junior team members, effective leadership that encourages teamwork and values everyone’s opinions makes a big impact. The project runs more smoothly and inclusively when cross-functional cooperation and open feedback channels are used. |

| Integration and Communication | Integration and Communication, Sensitivity to Criticism, Past Attitudes Reflection, Language Barriers, Evaluation Impact, Evaluation Performance Review System, Digital Transformation | The communication and integration themes refer to the development and integration of various systems, such as customer management systems, information systems, and others, so that team members can easily access, share, and transfer necessary and critical information for innovation (Smith, 2012). | The team in an organization working on either explorative or exploitative innovation would remain cohesive and focused through both effective integration and communication. In order to avoid misunderstandings, it is necessary to address communication barriers, including language and others. Further, it is also necessary to improve with the support of regular, constructive criticism that helps employees understand how they are performing and appreciate juniors’ ideas. By ensuring that everyone is in agreement, a clear communication mechanism fosters a more harmonious and effective team atmosphere. |

| Knowledge management | Knowledge Management, Innovation Development, Innovation Reset | The theme of knowledge management refers to the acquisition, sharing, and applying knowledge for various key tasks of innovation (Mårtensson, 2000). | Knowledge management promotes both individual and team growth by assisting in capturing and expanding a set of new skills and experiences. This would help employees to propose novel concepts and ideas for effective explorative and exploitive innovation and growth. Employees can gain knowledge from prior failures, successes, and experiences by reviewing and improving earlier initiatives. The organization stays competitive and evolving when employees are allowed to experiment and expand their expertise. |

| Theme | Position | |

|---|---|---|

| Exploitive Innovation | Exploratory Innovations | |

| Resource Management | Effective utilization of existing resources is an important aspect of exploitive innovation in which such existing resources are tactically deployed to continuously improve the current products and services. | Exploratory innovation, as a long-term venture of the firm, needs to be supported by resources at an efficient and effective level. Resources, both financial and non-financial, provide the necessary means to support activities, such as the acquisition of knowledge and technology, and experiment with these to develop highly innovative and radical products and services. |

| Skills and Capabilities | For exploitative innovation, firms quickly and continuously employ the existing stock of skills and other capabilities, such as the robustness of various systems like information that can enhance the existing products and services. | One of the key elements in a radical level of innovation is the ability to develop new ideas and experiment with them to innovate the products and services. Such abilities and skills have to be dynamic and unlimitable in nature, which a firm usually acquires over a period of time. |