Gender, Culture, and Social Media: Exploring Women’s Adoption of Social Media Entrepreneurship in Qatari Society

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Social Media Adoption by Entrepreneurs

2.2. Women Entrepreneurship in the Middle East

2.3. Social Media and Women Entrepreneurship in the Middle East

2.4. Case Study: Qatar

3. Theoretical Background and Hypothesis Development

3.1. Theoretical Background

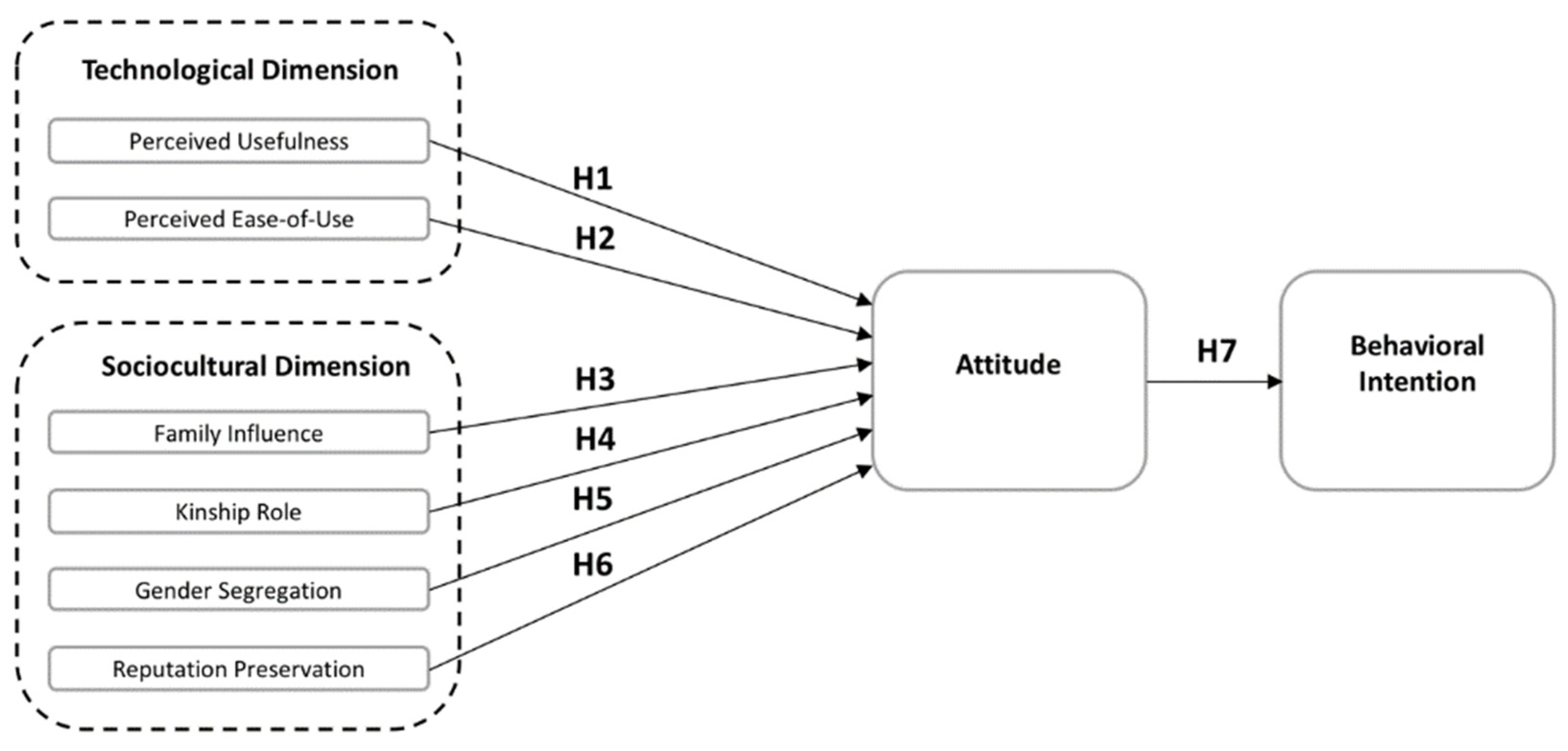

3.2. Conceptual Model and Hypotheses

3.3. Research Hypothesis

3.3.1. Perceived Usefulness

3.3.2. Perceived Ease of Use

3.3.3. Family Influence

3.3.4. Kinship Role

3.3.5. Gender Segregation

3.3.6. Reputation Preservation

3.3.7. Attitude

4. Methodology

4.1. Research Design

4.2. Study Population and Sampling

4.3. Data Collection

4.4. Development and Validation of Survey Instrument

4.5. Data Analysis

4.6. Ethical Considerations

5. Results

5.1. Descriptive Analysis

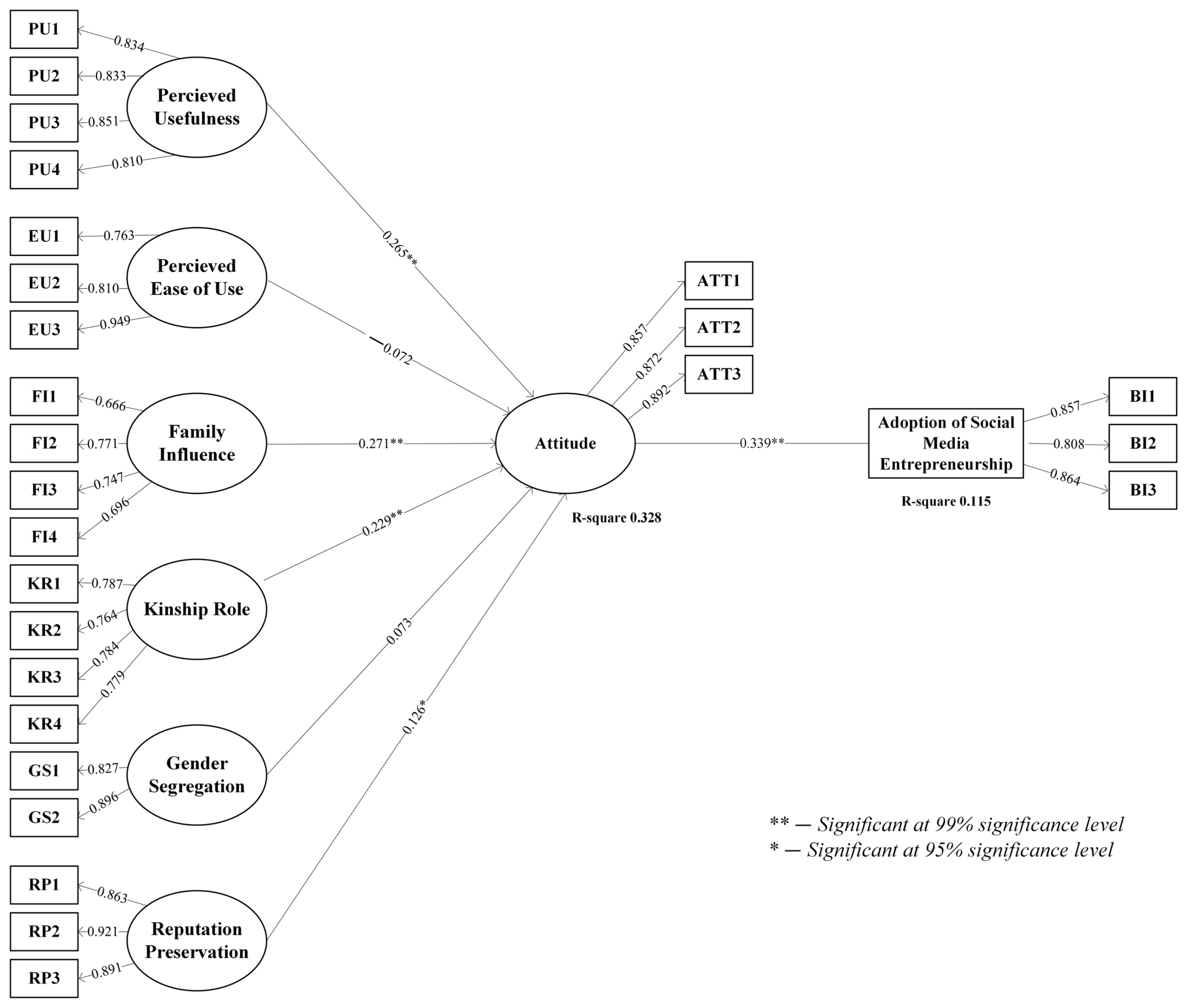

5.2. Measurement Model

5.3. Structural Model and Hypothesis Testing

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

7.1. Contribution and Implication

7.2. Limitations and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abed, S. S. (2020). Social commerce adoption using TOE framework: An empirical investigation of Saudi Arabian SMEs. International Journal of Information Management, 53, 102118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S. Z. (2011). Businesswomen in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: Characteristic, growth patterns and progression in a regional context. Equality, Diversity and Inclusion, 30(7), 610–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghaith, S. (2016). Understanding Kuwaiti women entrepreneurs and their adoption of social media: A study of gender, diffusion, and culture in the Middle East [Doctoral dissertation, Colorado State University]. [Google Scholar]

- Alghamdi, H. M. (2021). A study of Instagram as a technological enabler for Saudi women entrepreneurs. Multi-Knowledge Electronic Comprehensive Journal for Education and Science Publications, 44. Available online: https://mountainscholar.org/items/624d7c46-fcb5-465f-bb39-8a8c6e3c27f5 (accessed on 3 March 2024).

- Al-Ghanim, K. (2019). Perceptions of women’s roles between traditionalism and modernity in Qatar. Journal of Arabian Studies, 9(1), 52–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Harthi, A. S. A. (2017). Understanding entrepreneurship through the experiences of Omani entrepreneurs: Implications for entrepreneurship education. Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship, 22(1), 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, H. (2022). Education: An instrument to women empowerment in the state of Qatar. International Journal of Advanced Academic Studies, 4(3), 182–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mohannadi, A. S., & Furlan, R. (2022). The syntax of the Qatari traditional house: Privacy, gender segregation and hospitality constructing Qatar architectural identity. Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering, 21(2), 263–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Omoush, K., & Shaqrah, A. (2010). An empirical study of household Internet continuance adoption among Jordanian users. International Journal of Computer Science and Network Security, 10(1), 32–44. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Qahtani, M., Zguir, M., Al-Fagih, L., & Koç, M. (2022). Women Entrepreneurship for Sustainability: Investigations on Status, Challenges, Drivers, and Potentials in Qatar. Sustainability, 14(7), 4091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alreshoodi, S. A., Rehman, A. U., Alshammari, S. A., Khan, T. N., & Moid, S. (2022). Women entrepreneurs in Saudi Arabia: A portrait of progress in the context of their drivers and inhibitors. Journal of Enterprising Culture, 30(3), 375–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, H., Sakbani, K., & Tok, E. (2024). State aspirations for social and cultural transformations in Qatar. Social Sciences, 13(7), 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, S. Y., & Han, J. H. (2020). Considering cultural consonance in trustworthiness of online hotel reviews among Generation Y for sustainable tourism: An extended TAM model. Sustainability, 12(7), 2942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barragan, S., Erogul, M. S., & Essers, C. (2018). Strategic (dis)obedience’: Female entrepreneurs reflecting on and acting upon patriarchal practices. Gender, Work and Organization, 25(5), 575–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, D. (2022). Kinship is a network tracking social technology, not an evolutionary phenomenon. arXiv, arXiv:2204.02336. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2204.02336v1 (accessed on 3 March 2024).

- Bilge Johnson, S. A. (2023). Extended maternal roles in Middle Eastern families and cultures. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 62(10), S9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojadjiev, M., Mileva, I., Tomovska, M., & Vaneva, M. (2023). Entrepreneurship addendums on Hofstede’s dimensions of national culture. The European Journal of Applied Economics, 20(1), 122–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boshmaf, H. (2023). Jordanian women entrepreneurs and the role of social media: The road to empowerment. Dirasat: Human and Social Sciences, 50(3), 1396–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brush, C. G., de Bruin, A., & Welter, F. (2009). A gender-aware framework for women’s entrepreneurship. International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship, 1(1), 8–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho, S., & Barrios, A. (2021). Social commerce affordances for female entrepreneurship: The case of Facebook. Electronic Markets, 32(3), 1145–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W. (1998). Issues and opinion on structural equation modeling. MIS Quarterly, 22(1), vii–xvi. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, J., & Pita, M. (2020). Appraising entrepreneurship in Qatar under a gender perspective. International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship, 12(3), 233–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, D. J. (2018). Research design qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly: Management Information Systems, 13(3), 319–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Stefano, G., Ruggieri, S., Bonfanti, R. C., & Faraci, P. (2023). Entrepreneurship on social networking sites: The roles of attitude and perceived usefulness. Behavioral Sciences, 13(4), 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doha International Family Institute. (2019). Work-family balance: Challenges, experiences and implications for families in Qatar. Doha International Family Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Elshantaly, A., & Moussa, M. (2022). The role of social media in women’s entrepreneurship in the UAE: Implications for gender development and equality. University of Sharjah Journal for Humanities & Social Sciences, 19(3), 588–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ennis, C. A. (2019). The gendered complexities of promoting female entrepreneurship in the Gulf. New Political Economy, 24(3), 365–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erogul, M. S., Rod, M., & Barragan, S. (2019). Contextualizing Arab female entrepreneurship in the United Arab Emirates. Culture and Organization, 25(5), 317–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, M., Qalati, S. A., Khan, M. A. S., Shah, S. M. M., Ramzan, M., & Khan, R. S. (2021). Effects of entrepreneurial orientation on social media adoption and SME performance: The moderating role of innovation capabilities. PLoS ONE, 16(4), e0247320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fauzi, F. R., & Noer, H. A. (2024). Birr al-wālidayn: Studi Komparatif Penafsiran Surah al-Isrā’ 23–24 Perspektif Ibn Kathīr dan M. Quraish Shihab. Journal of Islamic Scriptures in Non-Arabic Societies, 1(2), 152–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouad, N. (2018). Women empowerment in Qatar [Master’s thesis, Qatar University]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, N., & Mirchandani, A. (2018). Investigating entrepreneurial success factors of women-owned SMEs in UAE. Management Decision, 56(1), 219–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., Sarstedt, M., Danks, N. P., & Ray, S. (2021). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) using R. Springer Nature. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harkness, G. (2019). Hijab micropractices: The strategic and situational use of clothing by Qatari women. Sociological Forum, 34(1), 71–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatoum, H. (2021, September 29–30). Investigating the effects of societal perceived gender differences on female entrepreneurship—Case of Bahrain. 2021 International Conference on Innovation and Intelligence for Informatics, Computing, and Technologies (pp. 757–763), Zallaq, Bahrain. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayton, J. C., & Cacciotti, G. (2013). Is there an entrepreneurial culture? A review of empirical research. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 25(9–10), 708–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M., & Rahman, M. F. (2018). Social media and the creation of entrepreneurial opportunity for women. Management, 8(4), 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huarng, K. H., Mas-Tur, A., & Yu, T. H. K. (2012). Factors affecting the success of women entrepreneurs. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 8(4), 487–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humaid, A. B., & Sabri, Y. (2019). The Examination of factors influencing Saudi small businesses’ social media adoption, by using UTAUT model. International Journal of Business Administration, 10(2), 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Itani, H., Sidani, Y. M., & Baalbaki, I. (2011). United Arab Emirates female entrepreneurs: Motivations and frustrations. Equality, Diversity and Inclusion, 30(5), 409–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemppainen, R. P. (2019). Saudi female innovators as entrepreneurs—Theoretical underpinnings. International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship, 11(2), 166–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A. G., Hasan, N., & Ali, M. R. (2023). Unmasking the behavioural intention of social commerce in developing countries: Integrating technology acceptance model. Global Business Review. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H. (2019). Contextualizing gender inequality in division of household labor contextualizing gender inequality in division of household labor and family life: A cross-national. Available online: https://repository.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/4887 (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Lakens, D. (2022). Sample size justification. Collabra: Psychology, 8(1), 33267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalonde, J. F. (2013). Cultural determinants of Arab entrepreneurship: An ethnographic perspective. Journal of Enterprising Communities, 7(3), 213–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madbouly, A., Al Khayyal, H., Mourssi, A., & Al Wakeel, W. (2021). Determinants of GCC women entrepreneurs performance: Are they different from men? Journal of Asian Business Strategy, 11(2), 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, D. (2012). Extending UTAUT to explain social media adoption by microbusinesses. International Journal of Managing Information Technology, 4(4), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, V. (2019). Women entrepreneurship in Gulf region: Challenges and strategies in GCC. International Journal of Asian Business and Information Management, 10(1), 94–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAdam, M., Crowley, C., & Harrison, R. T. (2020). Digital girl: Cyberfeminism and the emancipatory potential of digital entrepreneurship in emerging economies. Small Business Economics, 554, 1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, C., Holtschlag, C., Masuda, A. D., & Marquina, P. (2019). In which cultural contexts do individual values explain entrepreneurship? An integrative values framework using Schwartz’s theories. International Small Business Journal, 37(3), 241–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naguib, R. (2015). Female entrepreneurship in the UAE: A multi-level integrative lens. Gender in Management: An International Journal, 30(2), 135–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Planning Council. (2024). Labor force sample survey. National Planning Council. [Google Scholar]

- Nawi, N. B. C., Al Mamun, A., Nasir, N. A. B. M., Shokery, N. M. A. H., Raston, N. B. A., & Fazal, S. A. (2017). Acceptance and usage of social media as a platform among student entrepreneurs. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 24(2), 375–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumeyer, X., Santos, S. C., Caetano, A., & Kalbfleisch, P. (2019). Entrepreneurship ecosystems and women entrepreneurs: A social capital and network approach. Small Business Economics, 53(2), 475–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olanrewaju, A. S. T., Hossain, M. A., Whiteside, N., & Mercieca, P. (2020). Social media and entrepreneurship research: A literature review. International Journal of Information Management, 50, 90–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qatar Development Bank. (2020). Home-based businesses in Qatar study (Issue April). Available online: https://ossform.qdb.qa/ar/Documents/QDB_Home-Based%20Businesses%20in%20Qatar%20Study%202020_Arabic_Web-compressed.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2024).

- Qatar World Bank Gender Data Portal. (2023). Available online: https://genderdata.worldbank.org/en/economies/qatar (accessed on 20 January 2024).

- Qi, X. (2017). Reconstructing the concept of face in cultural sociology: In Goffman’s footsteps, following the Chinese case. Journal of Chinese Sociology, 4(1), 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabri, M. S., & Thomas, K. (2019). Psycho-attitudinal features: A study of female entrepreneurs in Saudi Arabia. International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship, 11, 459–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, G., & Bhamboo, U. (2023). Social commerce for success: Evaluating its effectiveness in empowering the next generation of entrepreneurs. International Journal for Multidisciplinary Research, 5(3), 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Salahshour Rad, M., Nilashi, M., & Mohamed Dahlan, H. (2018). Information technology adoption: A review of the literature and classification. Universal Access in the Information Society, 17(2), 361–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, R., & Yount, K. M. (2019). Structural accommodations of patriarchy: Women and workplace gender segregation in Qatar. Gender, Work and Organization, 26(4), 501–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setyawati, M. B., Parsons, A. P. J., Laing, B., Lynch, A., Habiburahman, I. L., & Izza, F. N. (2024). The family caregiving; A Rogerian concept analysis of Muslim perspective and Islamic sources. Heliyon, 10(3), e25415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shachak, A., Kuziemsky, C., & Petersen, C. (2019). Beyond TAM and UTAUT: Future directions for HIT implementation research. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 100, 103315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarek, H. (2019). Entrepreneurship, ICT and innovation: State of Qatar transformation to a knowledge-based economy. Political, Economic and Social Issues, 191, 192–438. [Google Scholar]

- Tripopsakul, S. (2018). Social media adoption as a business platform: An integrated tam-toe framework. Polish Journal of Management Studies, 18(2), 350–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turan, M., & Kara, A. (2018). Online social media usage behavior of entrepreneurs in an emerging market: Reasons, expected benefits and intentions. Journal of Research in Marketing and Entrepreneurship, 20(2), 273–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valliere, D. (2019). Refining national culture and entrepreneurship: The role of subcultural variation. Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research, 9(1), 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatanasakdakul, S., Aoun, C., & Defiandry, F. (2023). Social commerce adoption: A consumer’s perspective to an emergent frontier. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies, 2023(1), 3239491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V., Thong, J. Y. L., & Xu, X. (2012). Consumer acceptance and use of information technology: Extending the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology. MIS Quarterly: Management Information Systems, 36(1), 157–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsh, D. H. B., Kaciak, E., Mehtap, S., Pellegrini, M. M., Caputo, A., & Ahmed, S. (2021). The door swings in and out: The impact of family support and country stability on success of women entrepreneurs in the Arab world. International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship, 39(7), 619–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Research Construct | Measurement Items | References |

| Perceived usefulness (PU) | PU1: Using social media to do business is useful. PU2: Using social media to do business improves my business performance. PU3: Using social media to do business increases my productivity. PU4: Using social media to do business makes it easier to operate my business. | Adapted from Davis (1989) |

| Perceived ease of use (EU) | EU1: I find it easy to use social media to do business. EU2: Social media sites allow flexible interaction for doing business. EU3: Learning to operate a business using social media sites is easy for me. | Adapted from Davis (1989) |

| Family influence (FI) | FI1: My family approves of me doing business on social media. | Derived from literature (Al-Harthi, 2017; Ennis, 2019; Welsh et al., 2021) |

| FI2: My family is supportive of my social media business. | ||

| FI3: My family believe that doing business on social media is good for me. | ||

| FI4: My family is proud of me for running a business on social media. | ||

| Kinship role (KR) | KR1: As a woman, I feel that having my own business on social media allows me to meet my responsibilities towards my family. | Derived from literature (Al-Ghanim, 2019; Barragan et al., 2018; Brush et al., 2009) |

| KR2: As a woman, I feel that having my own business on social media gives me flexibility in managing my family time. | ||

| KR3: As a woman, I feel that having my own business on social media allows me to manage my household duties more efficiently. | ||

| KR4: As a woman, I feel that having my own business on social media allows me to participate more in extended family events and affairs that I am expected to be involved in. | ||

| Gender segregation (GS) | GS1: As a business woman in Qatar, social media allows me to have an appropriate channel of interaction with men for business purposes. | Derived from literature (Kemppainen, 2019; Mathew, 2019; Salem & Yount, 2019) |

| GS2: As a business woman in Qatar, social media allows me to develop business connections with stakeholders regardless of their gender. | ||

| GS3: As a business woman in Qatar, social media allows me to overcome in-person communication barriers with men. | ||

| Reputation preservation (RP) | RP1: I am doing online business on social media platforms because I am apprehensive about engaging in face-to-face business dealings as I fear it may tarnish my reputation. | Derived from literature (Al-Harthi, 2017; Gupta & Mirchandani, 2018; Itani et al., 2011) |

| RP2: I am doing online business on social media platforms because I pay a lot of attention to how others see me. | ||

| RP3: I am doing online business on social media platforms because I am concerned with protecting the pride of my family and their social status. | ||

| RP4: I am doing online business on social media platforms because I feel ashamed about losing face from potential failure. | ||

| Attitude (ATT) | ATT1: Using social media for business is a good idea. | Adapted from Davis (1989) |

| ATT2: I am favorable towards social media business. | ||

| ATT3: I am positive about social media for conducting business. | ||

| Behavioral intention (BI) | BI1: I intend to continue using social media sites for business purposes in the future. | Adapted from Venkatesh et al. (2012) |

| BI2: I predict that I will remain on social media for business in the future. | ||

| BI3: I plan to continue to use social media for business frequently. |

| Construct | Item | PLS Loadings | Cronbach’s Alpha | Composite Reliability | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PU | PU1 | 0.834 | 0.853 | 0.900 | 0.692 |

| PU2 | 0.833 | ||||

| PU3 | 0.851 | ||||

| PU4 | 0.810 | ||||

| EU | EU1 | 0.763 | 0.836 | 0.881 | 0.713 |

| EU2 | 0.810 | ||||

| EU3 | 0.949 | ||||

| FI | FI1 | 0.666 | 0.694 | 0.812 | 0.520 |

| FI2 | 0.771 | ||||

| FI3 | 0.747 | ||||

| FI4 | 0.696 | ||||

| KR | KR1 | 0.787 | 0.785 | 0.860 | 0.607 |

| KR2 | 0.764 | ||||

| KR3 | 0.784 | ||||

| KR4 | 0.779 | ||||

| GS | GS1 | 0.827 | 0.658 | 0.852 | 0.743 |

| GS2 | 0.896 | ||||

| GS3 | 0.342 | ||||

| RP | RP1 | 0.863 | 0.873 | 0.921 | 0.795 |

| RP2 | 0.921 | ||||

| RP3 | 0.891 | ||||

| RP4 | 0.290 | ||||

| ATT | ATT1 | 0.857 | 0.845 | 0.906 | 0.763 |

| ATT2 | 0.872 | ||||

| ATT3 | 0.892 | ||||

| BI | BI1 | 0.875 | 0.811 | 0.886 | 0.721 |

| BI2 | 0.808 | ||||

| BI3 | 0.864 |

| Paths | Actual Effect | Path Coefficient | Standard Deviation | T Statistics | Significance Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PU → ATT | + | 0.265 | 0.064 | 4.725 | 99% |

| EU → ATT | − | −0.072 | 0.073 | 1.112 | Not significant |

| FI → ATT | + | 0.271 | 0.059 | 5.271 | 99% |

| KR → ATT | + | 0.229 | 0.052 | 4.402 | 99% |

| GS → ATT | + | 0.073 | 0.055 | 1.317 | Not significant |

| RP → ATT | + | 0.126 | 0.060 | 2.105 | 95% |

| ATT → BI | + | 0.339 | 0.064 | 3.726 | 99% |

| Variable | Research Hypothesis | Results |

|---|---|---|

| Perceived usefulness (PU) | H1: Perceived usefulness positively affects women entrepreneurs’ attitude towards social media entrepreneurship in Qatar. | Accepted |

| Perceived ease of use (EU) | H2: Perceived ease of use positively affects women entrepreneurs’ attitude towards social media entrepreneurship in Qatar. | Rejected |

| Family influence (FI) | H3: Family influence positively affects women entrepreneurs’ attitude towards social media entrepreneurship in Qatar. | Accepted |

| Kinship role (KR) | H4: Kinship role positively affects women entrepreneurs’ attitude towards social media entrepreneurship in Qatar. | Accepted |

| Gender segregation (GS) | H5: Gender segregation positively affects women entrepreneurs’ attitude towards social media entrepreneurship in Qatar. | Rejected |

| Reputation preservation (RP) | H6: Reputation preservation positively affects women entrepreneurs’ attitude towards social media entrepreneurship in Qatar. | Accepted |

| Attitude (ATT) | H7: Attitude towards social media entrepreneurship positively affects women entrepreneurs’ behavioral intention to adopt it in Qatar. | Accepted |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Al-Boinin, H.; Vatanasakdakul, S.; Zaghouani, W. Gender, Culture, and Social Media: Exploring Women’s Adoption of Social Media Entrepreneurship in Qatari Society. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15030089

Al-Boinin H, Vatanasakdakul S, Zaghouani W. Gender, Culture, and Social Media: Exploring Women’s Adoption of Social Media Entrepreneurship in Qatari Society. Administrative Sciences. 2025; 15(3):89. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15030089

Chicago/Turabian StyleAl-Boinin, Hamda, Savanid Vatanasakdakul, and Wajdi Zaghouani. 2025. "Gender, Culture, and Social Media: Exploring Women’s Adoption of Social Media Entrepreneurship in Qatari Society" Administrative Sciences 15, no. 3: 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15030089

APA StyleAl-Boinin, H., Vatanasakdakul, S., & Zaghouani, W. (2025). Gender, Culture, and Social Media: Exploring Women’s Adoption of Social Media Entrepreneurship in Qatari Society. Administrative Sciences, 15(3), 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15030089