Abstract

The aim of the study was to investigate the impact of entrepreneurship education on the social entrepreneurial intentions of undergraduate tourism students at a Greek university. Using a qualitative diary-based research tool, the study examined how different educational practices shape students’ learning experiences, emotional involvement, and intentions to become social entrepreneurs. In total, 64 participants voluntarily decided to participate in the diary research, and they recorded their views on a weekly basis regarding their experience of and feelings on a variety of educational activities. The findings indicate that experiential and team-based methods greatly improved students’ knowledge of and enthusiasm for social entrepreneurship. Interactive videos of real-life examples boosted their sensitivity and critical thinking, while team activities such as the creation of business canvases and idea development and presentation enhanced their collaboration and practical application of concepts. Emotional engagement through team collaboration and the creation of business canvases on their personal entrepreneurial ideas were identified as major factors in boosting social entrepreneurial intention. This study emphasizes the significant impact of entrepreneurship education on promoting social entrepreneurial mindsets among tourism students, offering practical implications for designing impactful educational strategies in higher education and integrating experiential learning methods into entrepreneurship curricula.

1. Introduction

The literature recognizes entrepreneurship education as a key factor that shapes entrepreneurial skills and mindsets (Westhead & Solesvik, 2016), influencing students’ intentions to pursue various entrepreneurial paths, including social entrepreneurship. Social entrepreneurship combines business creation with social impact, and it is considered as a growing field that addresses societal challenges through innovative business models. Various studies have shown that entrepreneurial learning through different courses and teaching styles significantly influences students’ intentions to pursue entrepreneurship and equips them with the necessary skills and motivation to develop enterprises focused on social value creation (Westhead & Solesvik, 2016). For instance, Sultan et al. (2016) found that entrepreneurial education positively affects students’ intentions, and they recommend that universities and business schools offer such courses to inspire innovation and community contribution. Moreover, according to Liñán and Chen (2009), Shirokova et al. (2016), and Kefis and Xanthopoulou (2015), entrepreneurial intention has a significant role in forecasting entrepreneurial behaviors. Entrepreneurship education helps students develop the skills necessary to launch enterprises and motivates them to pursue entrepreneurship as a career (Astiana et al., 2022; Bae et al., 2014; Haddoud et al., 2022; Lv et al., 2021; Vodă & Florea, 2019). This instruction fosters an entrepreneurial mindset and raises awareness of entrepreneurship (Shahid & Ahsen, 2021). While entrepreneurship education fosters entrepreneurial mindsets, it is essential to explore how such education fosters social entrepreneurial intentions (SEIs). Social entrepreneurs leverage business skills to address social issues, making it imperative to examine how educational practices influence their motivations and aspirations.

Taking these arguments into consideration, it becomes important to investigate and evaluate the determinants of social entrepreneurial intention in students, as social entrepreneurship is successful in many areas globally (such as education, culture, health, and finance) and during crises (economic or social), highlighting the need for social entrepreneurs everywhere (Al-Qudah et al., 2022; Storr et al., 2022). Social entrepreneurship not only changes current markets but also creates new ones through initiatives such as fair trade and microfinance. Social entrepreneurs have brought about significant changes to society by focusing on social issues (Zeyen et al., 2013). However, according to Tiwari et al. (2017), although social entrepreneurship benefits welfare and economic growth, its growth rate remains low. This leads to an important question for scholars and policymakers regarding how to encourage the faster and stronger growth of social entrepreneurship. Understanding the factors that affect people’s thinking is essential for supporting and encouraging social entrepreneurs (Tiwari et al., 2017). Prior research on entrepreneurial intention (Ip et al., 2017; Liñán & Fayolle, 2015) has primarily examined five key areas: theory, personal characteristics, entrepreneurship-related education, situational factors such as social needs and market conditions, and the connection between intention and action; thus, the inquiry that results from this is “What influences students’ desire to become social entrepreneurs?”. In the context of social entrepreneurship, these factors play a crucial role. For example, education on social entrepreneurship fosters a focus on social impact and business viability. As these ventures strive toward the primary organizational goal of generating social value, they base their operations on commercial principles (Ahmad & Bajwa, 2023).

The aim of this study was to explore the impact of entrepreneurship education on students’ social entrepreneurial intention (SEI) through the implementation of different educational activities each week. Thus, the research question (RQ) adopted was as follows:

RQ: “How do participants in Entrepreneurship Education Programs (EEPs) experience and perceive changes in their Social Entrepreneurial Intention (SEI) through their participation in different educational techniques over time?”

The specific aim of this study was to investigate how undergraduate students develop their social entrepreneurial intention following a thirteen-week course called “Entrepreneurship and Innovation.” Activities on the course included making business canvases for their own business concepts and watching videos about social entrepreneurship. Investigating how these activities affected students’ aspirations to engage in social entrepreneurship and collecting their feedback throughout the semester were the objectives. The unique approach of this study, in particular the use of reflective diaries as the main instrument to track students’ entrepreneurial goals through time, is what makes it distinctive. By documenting their evolving entrepreneurial intentions, students gain deeper self-awareness and critical thinking skills, which can enhance curriculum design by incorporating more experiential and reflective practices that encourage long-term engagement in social entrepreneurship. This methodology distinguishes this study from previous research on entrepreneurship education, which includes few long-term qualitative studies (Brüne & Lutz, 2020; Ndofirepi & Rambe, 2018). Similar methods have only been employed in a small number of entrepreneurial education studies, such as Hägg (2022) and Heinonen (2007). Because they force students to record their ideas, reflections, and experiences throughout the semester, reflective diaries yield rich data. This method allows for the identification of changes, trends, and significant moments, offering a detailed view of the development of students’ entrepreneurial identities and goals (Morrison, 2006). Thus, the innovative application of reflective diaries in this study contributes to the existing literature by introducing new insights into entrepreneurial intention (EI) development and by providing a framework for future research in entrepreneurship education and related fields.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Social Entrepreneurship (SE) and Social Entrepreneurial Intention (SEI)

Social entrepreneurship (SE) is considered a sub discipline of the entrepreneurship field (Steyaert, 2007). In the 1970s, Davis (1973) presented a variety of perspectives on entrepreneurship by discussing the social responsibilities of enterprises, which gave rise to the concept of social entrepreneurship. Young (1998) highlighted the innovative ways in which nonprofit entrepreneurs and managers address social issues. Waddock and Post (1991) defined social entrepreneurs as leaders in the business sector who brought about changes in public priorities and public understanding of social issues. A significant change occurred in the late 1990s as scholars such as Wallace (1999), Fowler (2000), and Johnson (2000) attempted to elevate social entrepreneurship to the same degree of academic attention as traditional entrepreneurship. According to Zahra et al. (2009), mainstream entrepreneurship researchers remain hesitant to consider social entrepreneurship. Hirsch and Levin (1999) refer to social entrepreneurship as an “emerging excitement”, and it is currently attracting interest as a new field of study. However, there are two significant scholarly obstacles in this field. First, there is no clear theoretical framework or consensus regarding the definition of social entrepreneurship because it is frequently viewed as a component of more general concepts, such as social innovation and entrepreneurship. Second, the field is caught between the constraints of its theoretical underpinnings and the requirements for practical relevance (Mair & Martí, 2006).

Consequently, the key to understanding SE is to include it in entrepreneurship research (Chell, 2007). Zahra et al. (2009) define social entrepreneurship as the search for opportunities to enhance social wealth by starting new companies or managing existing organizations in innovative ways. Although there are many definitions and explanations, social entrepreneurship is widely believed to be a process that starts with the formation of social concepts, recognizing potentials solutions for sustainable social development. Social entrepreneurship’s primary goal is to address social challenges or create social value through innovative solutions; in fact, this is what sets social businesses apart from other business models (Muñoz & Kimmitt, 2019). According to Tran and Von Korflesch (2016), the clear and core goal of SE is to create social value or address social challenges through creative solutions; this is what sets SE apart from other types of entrepreneurship. Almost all definitions of social entrepreneurship place more emphasis on environmental or social goals than on maximizing profits or other tactical factors. Innovation is another unique feature. Innovation can take many forms, such as brand-new goods and services, creative answers to societal problems, or completely different organizational structures and procedures. Innovation models are often integrated into social entrepreneurship projects. Social entrepreneurs scale their ventures to various contexts through partnerships and spread their socially innovative models through performance-driven and market-oriented actions to achieve broader and longer-lasting outcomes (Kimakwa et al., 2023). However, one major issue for researchers is the difference between social entrepreneurship and innovation. Phillips et al. (2015) pointed out that, while social innovation reallocates resources for social change, social entrepreneurship uses market demand to ensure financial sustainability while tackling social problems. Social innovation covers a wide range of activities aimed at meeting uncovered social needs, typically through businesses that focus on social improvement (Mulgan, 2006). On the other hand, social entrepreneurship is a more specific part of entrepreneurship (Defourny & Nyssens, 2010). This overlap exists because social entrepreneurship tries to balance business goals with social growth objectives (Prabhu, 1999). Social innovation, a broader concept, requires teamwork and systematic approaches, indicating that social enterprises and entrepreneurs function within larger social innovation systems (Phillips et al., 2015).

Entrepreneurial intention (EI) was defined by Thompson (2009) as a self-acknowledged conviction by a person who intends to set up a new business venture in the future. Entrepreneurial intention (EI) is also described as an individual’s desire to engage in entrepreneurial activities, such as starting a new firm or working for themselves (Dohse & Walter, 2010). In a simpler form, entrepreneurial intention is defined as a person’s will and desire to start a new business (P. Xanthopoulou & Sahinidis, 2024). Similarly, in the context of SE, social entrepreneurial intention (SEI) can be understood as the belief, desire, and determination of a person to set up a new social enterprise (Tiwari et al., 2017).

Numerous factors, referred to as “motivators”, are identified in the literature as influencing a person’s decision to start their own business. These comprise psychological characteristics, attitudes, values, and social and demographic factors such family background, gender, and education (Jovičić-Vuković et al., 2020). Research indicates that people’s surroundings have an impact on their entrepreneurial behavior. Additionally, the literature emphasizes the characteristics, psychological attributes, and individual abilities of entrepreneurs and the external factors affecting them (Reissová et al., 2020). These factors also affect people’s plans to launch their own companies (Tleuberdinova et al., 2021). On the other hand, prior research (e.g., Autio et al., 2001; Esfandiar et al., 2019) suggests that pressure from peers, family, and friends have little to no impact on people’s decision to start their own enterprises. Gurel et al. (2010) discovered a strong correlation between creativity, risk-taking behavior, having an entrepreneurial family history, and entrepreneurial intention in relation to tourism students. The positive impact of entrepreneurship education on tourism students’ business aspirations was validated by Zhang et al. (2020). Others, like Ayikoru et al. (2009), assert that entrepreneurship education creates an entrepreneurial learning environment and effectively utilizes students’ skills.

2.2. Entrepreneurship Education, Pedagogical Aspects, and Entrepreneurial Intention

Entrepreneurship education is considered important for boosting individuals’ intention to start a business. Studies reveal that people with more formal education tend to pursue entrepreneurial opportunities (Neneh, 2014; Wilson et al., 2007). In addition to encouraging people to start their own enterprises, entrepreneurship education also helps them do so. Entrepreneurship education has been shown to be an effective means of encouraging entrepreneurial behavior (Bischoff et al., 2018; Raposo & Do Paço, 2011; Sahinidis et al., 2019; P. I. Xanthopoulou & Sahinidis, 2022). Developing skills, integrating theory into real-world experiences, and increasing awareness of entrepreneurship are some of the vital advantages of entrepreneurship education. According to Bae (2022) and Haddoud et al. (2022), it also presents entrepreneurship as a feasible career choice. Ahmed et al. (2020) emphasized the importance of beginning entrepreneurship education early, as it is vital for young entrepreneurs to learn how to manage their businesses and build skills for a global economy.

Despite advancements, the execution and outcomes of entrepreneurship education programs (EEPs) vary by country and field of study. For instance, business and economics departments tend to have comprehensive EEPs, while other disciplines often provide merely optional entrepreneurship courses (Papagiannis, 2018). It is also worth mentioning that different teaching methods also result in varied outcomes, since the quality and focus of education can differ by region and institution (Haase & Lautenschläger, 2011). This variation has led to debates on whether EEPs can effectively overcome personal characteristics, such as openness to experience, and external factors, such as family or social background (Liñán, 2004). Furthermore, beliefs and intentions regarding entrepreneurship evolve over time and are influenced by education, available opportunities, and obstacles (Lee & Wong, 2004). Overall, empirical studies have shown that EEPs have a positive effect on entrepreneurial intention (EI) and related aspects, like personal attitude (PA) and perceived behavioral control (PBC) (Ajzen, 2005; Hassan et al., 2020; López-Meri et al., 2021). EEPs encourage learning and motivation, which in turn influence factors linked to EI. Beyond the creation of new businesses, there is a need for more ways to assess entrepreneurial intent and effectiveness (Fayolle & Gailly, 2009; Oosterbeek et al., 2010; Raposo & Do Paço, 2011). Despite the clear benefits of EEPs, several challenges remain. The absence of common teaching materials and methods hampers the consistent delivery of entrepreneurship education (Matlay, 2005). Research emphasizes the need for innovative teaching strategies, such as reflective practices, role-playing, success stories, and interactive group activities, to enhance students’ confidence and intention to pursue entrepreneurship (Asghar et al., 2016). At the same time, they also learn entrepreneurial skills. Knowledge and skills help to improve self-efficacy and the perceived attractiveness of entrepreneurship (Ojogbo et al., 2016; Puni et al., 2018). However, there are still issues related to education. Higher education institutions do not prepare students well enough for self-employment, resulting in a loss of potential entrepreneurs (Marire et al., 2017).

Innovative pedagogical strategies, such as reflective diaries, collaborative projects, and simulations, have been shown to significantly enhance the effectiveness of EE (P. Xanthopoulou et al., 2024a). Diary-based research conducted over a semester revealed that students who engaged in hands-on entrepreneurial tasks reported greater clarity in their entrepreneurial goals and an increased sense of self-efficacy (P. Xanthopoulou et al., 2024b). Similarly, Heinonen’s approach to teaching entrepreneurship emphasized experiential learning, which fosters critical thinking and problem-solving skills (Heinonen, 2007). Students can develop an entrepreneurial mindset by working in groups to construct mock business models. According to P. Xanthopoulou et al. (2024a), these tasks improve technical skills and teamwork, both of which are essential for success in business. Entrepreneurial intention (EI) also depends on how instructional strategies match students’ career goals, especially in sectors like tourism (P. I. Xanthopoulou & Sahinidis, 2022; Sahinidis et al., 2019). Simulations and case studies are common components of experiential learning in tourist education, which empowers students to address real-world problems and come up with creative solutions. This promotes the economic growth of areas that rely on tourism in addition to helping students find employment (Kefis & Xanthopoulou, 2015; P. I. Xanthopoulou & Sahinidis, 2022).

Peers and teachers can also help increase interest in entrepreneurship. Effective teaching strategies, such as group projects and games, can boost students’ self-esteem and enthusiasm for launching their own ventures (Li & Wu, 2019). Collaborating in groups and receiving encouragement from enthusiastic educators can help link entrepreneurial education to outcomes like enthusiasm and confidence (Li & Wu, 2019). To boost entrepreneurship success and go from intention to action, innovative teaching strategies, practical exercises, and university assistance are required. It is overall accepted that entrepreneurship education has a good effect on people’s desire and intention to be entrepreneurs, especially when combined with practical activities and thinking (Kavoura & Andersson, 2016; Sahinidis et al., 2019). Students who take part in these activities are more likely to launch their own businesses (P. I. Xanthopoulou & Sahinidis, 2022). To improve the benefits of entrepreneurship education programs (EEPs), schools should focus on hands-on learning, work with entrepreneurial organizations, and create innovative teaching methods. These approaches will help build entrepreneurial intentions and success by connecting school learning with real-world business activities.

3. Materials and Methods

This study was initially presented at an international conference, where it was honored with the Best Paper Award. The paper was titled “How Stable Are Students’ Intentions to Be Self-Employed? A Qualitative Study of Students’ Entrepreneurial Intention Change”. This preliminary research functioned as a pilot study, focusing on a different sample size of 140 university students who had recently completed an entrepreneurship course. Although the collection of qualitative diary data is the main emphasis of this study, references to the quantitative aspects of the pilot project are included to contextualize the findings. Although it is used as a comparison benchmark, the quantitative dataset is not a fundamental part of this study.

Through structured interviews, this study examined the evolution of social entrepreneurial intentions over time, identifying influential factors such as the attractiveness of entrepreneurial ideas, team dynamics, pedagogical approaches, university support mechanisms, and individual personality traits. Building on the findings of the pilot study, and addressing the limited availability of longitudinal studies in this research area, the authors published a subsequent paper titled “Shifting Mindsets: Changes in Entrepreneurial Intention Among University Students” (P. Xanthopoulou et al., 2024b), published in Administrative Sciences Journal.

3.1. Research Design and Data Collection

Notably, this study represents the first diary study to investigate the impact of entrepreneurship education on the formation of social entrepreneurial intentions. This methodological approach allowed for a more thorough analysis of the persistence and evolution of social entrepreneurial intentions over an extended period of time after the completion of an entrepreneurship course.

For qualitative data analysis, NVivo12 software was used, as in the pilot study. The results are intended to shed more light on the important variables that influence changes in students’ aspirations to pursue entrepreneurship. By looking at dynamics seen over a longer period of time and with a larger sample, this extension and continuation of the pilot study not only confirms the original findings but also contributes to scholarly conversation. Crucially, this study aimed to provide useful information to educational institutions and politicians who want to encourage and maintain students’ entrepreneurial mindsets. The research timeline was organized as shown in Table 1 below.

Table 1.

Weekly Activity Table.

3.2. Sampling Strategy and Participant Characterization

Second-year undergraduate students who participated in a “Entrepreneurship and Innovation” course at the Department of Tourism Management of a Greek public university were the subjects of the current study, which was conducted during the academic year 2024–2025. The study sample consisted of 64 second-year undergraduate students enrolled in the Entrepreneurship and Innovation course at a Greek public university. Given their weekly exposure to entrepreneurship and corporate social responsibility courses, it was acknowledged that their behaviors and attitudes toward social entrepreneurship would be influenced. This study specifically examined whether learning activities further shaped their social entrepreneurial intention. The research sample participated in 12 weeks of instruction, which included theory classes and weekly activities. This cohort was chosen due to the lack of research on the development of social entrepreneurial intention (SEI) during this crucial period of education, as noted by Nabi et al. (2018). The idea that students’ entrepreneurial aspirations and mental growth are greatly impacted by the entrepreneurship education they receive and the activities they engage in provides support for this choice. Students’ thoughts on different teaching methods and their developing social entrepreneurial goals were documented in the diaries.

This study recognizes social entrepreneurial intention (SEI) as a subjective, dynamic socio-cognitive construct via the prism of social constructivism. According to Leitch and Harrison (2016), entrepreneurial intention is inherently unstable. This perspective served as the foundation for the study’s qualitative methodological approach, which involved the use of reflective diaries to collect different perspectives on students’ goals of becoming entrepreneurs. Data were collected by using Google Forms to ask the participants identical questions each week after completing the weekly activities throughout the semester. The primary data were examined using QSR NVivo12 software and Microsoft Excel. Students were told that participation was voluntary and that their lack of involvement would not have any detrimental effects on their academic performance. The study included sixty-four participants. To offer a structured approach to self-assessment and reflection on their business experience, these diaries used the “What So What Now What” critical reflection paradigm. With a primary focus on the development of their intention to be self-employed, this model facilitated the exploration of their experiences during the course (‘What’); their feelings, thoughts, and understanding of the implications of what they’d learned after attending each week of the course (‘So What’); and their potential entrepreneurial actions in response to these reflections (‘Now What’). The purpose of this reflection exercise was to help students better understand how their business objectives and identity formation relate to academic and personal development. As a type of support, the research team provided participants with any guidance they needed.

3.3. Data Analysis and NVivo Utilization

NVivo 12 software was used to conduct thematic analysis of the diary entries. The analysis followed specific key steps. Firstly, Data Coding and Categorization involved coding the responses into predefined and emerging themes related to social entrepreneurial intention and social entrepreneurship. Secondly, during the step of Category Definition, the primary categories used in the analysis included the following: Social Entrepreneurial Intention (which refers to the expressions of intent to start a social enterprise), Emotional Engagement (which means the feelings of motivation and self-efficacy), Experiential Learning Impact (including the influence of team-based and reflective activities), Barriers to Entrepreneurship (which refers to the specific challenges perceived by students in pursuing social ventures), and Interpretation and Validation (including indicative quotes that were selected to support the thematic findings and their reliability).

4. Results

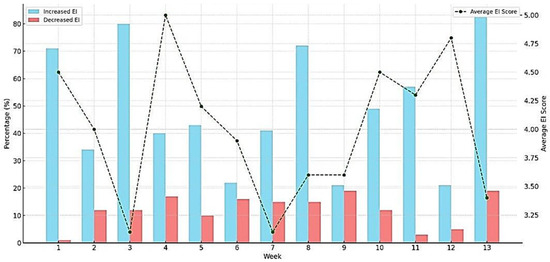

To represent the findings, Table 2 shows how students’ social entrepreneurial intention (SEI) changed over the 13-week course. To determine the percentage of increased or decreased SEI, the number of entries showing change was divided by the total number of weekly entries and then multiplied by 100. Table 2 displays the weekly changes in EI as students worked on specific learning goals and activities. Each week’s topic and method had different effects on the students. Table 2 also includes direct quotes from the students to provide qualitative insights into their thoughts and feelings. These quotes help explain the statistics and highlight the factors that influence students’ SEI. Conversely, Weeks 1 and 8 had the highest increases in SEI, at 71% and 72%, respectively. Week 1 kicked off the course on team formation and basic activities, boosting initial excitement and confidence. Week 8 focused on social entrepreneurship and sustainability, greatly engaging students and motivating them to think about tackling social issues through entrepreneurial efforts.

Table 2.

Thirteen-Week Social Entrepreneurial Intention with Weekly Activities.

To assess the overall effect of the course activities, an “Average SEI Score” was created to track students’ entrepreneurial intention weekly. This score, based on a Likert scale from 1 (lowest intention) to 5 (highest intention), was calculated using students’ expressions of SEI in their diary entries. Each week, the total score was divided by the number of students to obtain the average score. The factors affecting the score included students’ self-evaluated readiness, enthusiasm, and commitment, as well as other measures of entrepreneurial attitude. The Average SEI Score showed more trends in students’ SEI. Scores started high at an average of 4.5 in Week 1 but showed slight shifts throughout the course. A drop occurred in Weeks 6 and 7, which were linked to difficult topics. However, the score bounced back to 3.6 in Week 8 as students engaged with socially relevant entrepreneurial ideas. The course ended with scores stabilizing at an average of around 4.3 to 4.8 in Weeks 11 and 12, showing a solid entrepreneurial mindset. These results highlight the changing nature of entrepreneurial intention and the important impact of tailored educational methods in encouraging and maintaining the entrepreneurial drive. In conclusion, the findings indicate that although tough subjects might temporarily lower entrepreneurial intention, activities that focus on collaboration, innovation, and social impact consistently improve students’ willingness to pursue entrepreneurial projects. The mix of experiential, reflective, and practical methods was essential and played an important role in encouraging business development during the course.

Table 2 provides valuable insights on how various teaching methods affect students’ social entrepreneurial intentions (SEIs). Weekly activities aimed at enhancing entrepreneurial skills and mindsets were assessed for their effect on students’ desire to pursue entrepreneurship, both favorable and unfavorable. Each week, students thought about whether their entrepreneurial intention had increased because of the learning approaches used. For example, in Week 1, activities for forming teams and an overview of entrepreneurship led to 20% of the students noting an increase in SEI. In Week 2, brainstorming and generating ideas increased this to 25%. By Week 8, the impact peaked at 70%, as students participated in discussions about social entrepreneurship and sustainability, which inspired a large number of them. Some activities caused a drop in entrepreneurial intention. In Week 7, which focused on entrepreneurship challenges, such as legal issues and risk management, 10% of students felt less motivated. The complexity of these topics caused them to doubt their chances of success as entrepreneurs. However, in most weeks, only a few students (often under 5%) reported a decrease in SEI.

To determine the net impact for each week, the percentage of students with decreased SEI was subtracted from those for whom it increased. This provided a better understanding of the overall effects of the weekly activities. Weeks with active, hands-on tasks, such as brainstorming (Week 2), teamwork (Week 5), and pitching (Week 9), showed strong positive impacts. In contrast, weeks that introduced problems (such as Week 7) or theoretical parts (such as Week 3) had less or negative net impacts. Quotes from the students’ diary entries highlight changes in their SEI. In Week 5, one student said, ‘Ideas are buzzing; feeling incredibly inspired to innovate’, showing their excitement following teamwork. In Week 6, another student mentioned, “The guest lecture made me think about how much support I need to start a venture”, showing a reflective but cautious view of entrepreneurship. The effect on SEI varied based on the weekly focus and activities. Earlier weeks stressed basic skills, such as understanding entrepreneurial concepts and forming teams, establishing a positive starting point for SEI. In the middle weeks, students engaged in collaborative and practical learning, such as preparing business canvases and addressing sustainability issues, thus significantly boosting SEI. Later weeks included reflective tasks and presentations that reinforced students’ intentions to pursue social entrepreneurship.

The data show a consistent rise in entrepreneurial intention, with increases in the net impact as the course moved forward. The most effective activities involved active participation, such as brainstorming, teamwork, and practical workshops. However, tasks introducing challenges or theoretical issues, such as legal discussions or self-evaluations, sometimes temporarily lowered enthusiasm. This analysis highlights that teaching methods focusing on experiential and collaborative learning are particularly successful in developing entrepreneurial intentions. However, reflective and challenge-based elements are also important as they encourage students to think critically about their readiness for entrepreneurship. Figure 1 below visualizes the weekly changes in entrepreneurial intention.

Figure 1.

Weekly Shifts in Social Entrepreneurial Intention.

Figure 1 shows how weekly educational activities affected students’ desire to start their own businesses. The bar chart displays the percentage of students whose entrepreneurial interest increased or decreased throughout the course. For example, in Week 1, which dealt with team building and basic entrepreneurial ideas, there was a notable rise in interest (71%) and only a small drop (1%). This implies that the initial activities that encouraged enthusiasm and teamwork have a strong effect on motivation. Similarly, Week 8, which focused on social entrepreneurship and sustainability, also triggered a high percentage of SEI increase (72%), showing that engaging in topics with social importance is impactful. However, steady growth was not observed every week. Weeks 6 and 7, which covered financial planning, laws, and entrepreneurial challenges, revealed a clear decline in interest and then a rise in interest. These weeks presented ideas that, although important, seemed overwhelming or less appealing to students. Nevertheless, the average social entrepreneurial intention (SEI) score, shown in the line chart, remained quite high, with small decreases during difficult weeks. The highest scores were observed following reflective or collaborative activities, such as those undertaken in Week 10 (workshops on entrepreneurial frameworks) and Week 12 (final presentations), underscoring the effectiveness of hands-on and result-oriented approaches.

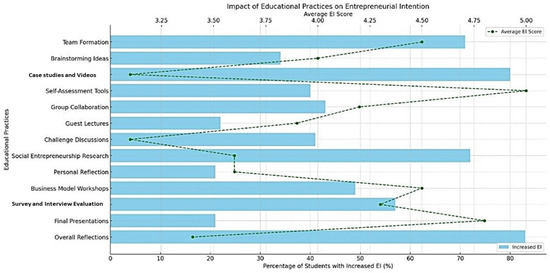

In addition, Figure 2 shows how some teaching methods relate to improving entrepreneurial intention.

Figure 2.

Impact of Educational Practices on Social Entrepreneurial Intention.

The horizontal bars indicate the percentage of students whose social entrepreneurial intention increased for each method, whereas the line graph shows the average social entrepreneurial intention (SEI) score linked to these methods. The findings indicate that hands-on and group activities, such as team formation (71%), brainstorming ideas (34%), and research on social entrepreneurship (72%), were effective in boosting entrepreneurial intention. Activities that involved students’ active participation, such as business model workshops and final presentations, also had high average SEI scores (4.5 and 4.8, respectively). These approaches likely equip students with real-world skills and confidence in their entrepreneurial potential. On the other hand, methods like guest lectures (22%) and discussions about challenges (41%) saw lower increases in entrepreneurial intention. This might be due to their focus on theory or the complexity of subjects such as legal and financial planning. Nevertheless, these activities are important for helping students understand real entrepreneurial challenges, as shown by their moderate SEI scores. Overall, Figure 2 highlights the need for a well-rounded teaching strategy. Learning experiences that encourage cooperation, creativity, and social impact lead to notable growth regarding entrepreneurial intention. Simultaneously, reflective and challenge-based practices assist in preparing students for the complexities of entrepreneurship, contributing to a complete and thorough educational experience.

5. Discussion

This study shows that entrepreneurship education (EE) is very important for influencing students’ social entrepreneurial intentions (SEIs) confirming the findings of the literature. However, by looking at how different teaching methods worked during a 13-week course, this research provides useful and original information on how experiential, reflective, and collaborative learning helps develop entrepreneurial mindsets. These results match earlier studies that talk about how EE can boost entrepreneurial ambitions (Vodă & Florea, 2019). Experiential learning was key to improving SEI. In Weeks 1 and 5, team-based activities like team formation and brainstorming increased SEI for 71% and 43% of students, respectively. This is consistent with the findings of Heinonen (2007) and P. Xanthopoulou et al. (2024a), who noted that working together improves entrepreneurial skills like problem-solving and teamwork. In Weeks 10 and 11, practical workshops on entrepreneurial frameworks also raised SEI by giving students the tools to turn theory into action. Students felt “ready to pitch ideas confidently”, highlighting the importance of these practical exercises (Fayolle & Gailly, 2009; Raposo & Do Paço, 2011). Reflective practices in Week 9 helped boost critical thinking and self-assessment. Students reported feeling more motivated and clear about their entrepreneurial goals, echoing the work of Hägg (2022) and Morrison (2006), who showed that reflective diaries help track entrepreneurial progress. These activities aided in narrowing the intention–action gap by helping students connect their entrepreneurial goals with growing skills (Ajzen, 2005; Autio et al., 2001).

This study sheds light on the methods that have the most significant impact on developing SEI, offering practical implications for educators seeking to design effective EE programs. One important finding is that experiential learning has a significant impact on entrepreneurial intention. Experiential learning, which involves students taking part in practical activities, helped increase their SEI. In particular, activities that involved working in teams at the beginning of the course, such as forming teams and brainstorming, positively affected the SEI of many students. For instance, in Week 1, SEI increased in 71% of students, and by Week 5, it improved in 43%. This percentage increase was calculated as the proportion of students who reported a rise in their entrepreneurial intention each week compared to the total number of participants. For instance, in Week 1, students expressed increased SEI, which means that 71% of the 64 participants recorded higher SEI in their diaries. Similarly, in Week 5, the percentage was 43%, reflecting a relative shift based on participants’ self-reported motivation levels.

These outcomes support earlier work by Heinonen (2007) and P. Xanthopoulou et al. (2024a), who pointed out that teamwork is key in developing entrepreneurial skills, such as problem-solving. Sahinidis et al. (2019) also noted that team activities in entrepreneurship education promote vital skills that help students deal with business uncertainties. By letting students experience entrepreneurship through structured team tasks, they developed a better grasp of how to tackle challenges, work together, and think creatively. Working on entrepreneurial tasks seems to encourage risk taking and creativity, which are important for successful entrepreneurship (Sahinidis et al., 2019). This study reaffirms the idea that hands-on learning is an effective way to build social entrepreneurial intention, as suggested by Kolb (2014) and Fayolle (2018). Davidsson and Honig (2003) argue that being actively involved in the entrepreneurial process builds self-efficacy, which is vital for fostering an entrepreneurial mindset. In addition to team activities, practical workshops aimed at entrepreneurial frameworks and ideas have been influential in boosting students’ SEI. During Weeks 10 and 11, these workshops equipped students with tools to transform theory into practical action. Many students said they felt “ready to pitch ideas confidently”, showing that these sessions improved both their theoretical knowledge and preparedness for real-world efforts. This aligns with the findings of Raposo and Do Paço (2011) and Fayolle and Gailly (2009), who highlighted that experiential education, especially practical exercises, helps connect academic knowledge with practical skills. This supports the arguments put forth by Lorz (2011), who stated that using theory in real-world contexts is crucial for developing key entrepreneurial skills. These results indicate that more tangible learning experiences lead to greater confidence in students’ abilities to act toward their entrepreneurial goals. A hands-on learning approach empowers students, especially when applying theoretical concepts to real business scenarios or pitching ideas to others. This idea aligns with Fayolle and Gailly (2009), who maintain that the practical application of entrepreneurial knowledge boosts students’ motivation to engage in entrepreneurial activities.

The reflective aspect of the course, which occurred in Week 9, played a key role in enhancing students’ critical thinking and self-evaluation skills. Students participated in reflective activities, such as journaling and self-assessment, to look closely at their personal goals and progress during the course. Consequently, many students felt more motivated and had a clearer understanding of their social entrepreneurial goals. These results align with those of Hägg (2022) and Morrison (2006), who stress the importance of reflective practices, which are important for tracking growth in entrepreneurship and aiding individuals in better understanding their motivations and abilities. Reflective practices play a vital role in learning from mistakes, which is a key part of being an entrepreneur (Mitchell et al., 2002). By reviewing their entrepreneurial experiences, students could relate their personal values to their skills, which helped close the intention–action gap (Ajzen, 2005; Autio et al., 2001). In simple terms, reflection allowed students to go beyond knowing about entrepreneurship toward having a clearer direction on how to act on their own intentions. Cope (2005) noted that reflection assists people in solidifying their entrepreneurial identity, giving them the necessary cognitive clarity to set actionable goals. This supports the finding that reflection is essential for building an entrepreneurial identity and commitment (Hägg, 2022).

The research also noted that some weeks that focused on financial and legal topics (Weeks 6 and 7) resulted in temporary decreases in entrepreneurial intention (EI), with 16% and 15% of students showing lower intentions. This corresponds to Farooq (2018) and Wang (2020), who pointed out that introducing students to entrepreneurship challenges might initially dampen their motivation. However, this exposure is crucial for preparing students to face real-world entrepreneurial obstacles. Adding supportive elements, such as mentorship or case studies, could help ease the negative impact of these discussions (Kanwal et al., 2019). The largest jumps in SEI were seen in Week 8, focusing on social entrepreneurship and sustainability, where 72% of students showed an increase in intent. This aligns with the findings of Tiwari et al. (2017) and Zahra et al. (2009), who found that addressing social issues resonates with younger individuals. Research projects and practical examples of social enterprises have enhanced students’ understanding of value creation beyond mere profit, supporting Tran and Von Korflesch (2016).

Furthermore, the study highlights the significance of emotional engagement and social backing. Weeks with team activities (such as Week 5) foster team spirit and motivation, which are critical for sustaining the entrepreneurial drive (Davidsson & Honig, 2003; P. I. Xanthopoulou & Sahinidis, 2022). This finding aligns with studies indicating that team dynamics and peer support significantly influence entrepreneurial intent (Bogatyreva & Shirokova, 2017; de Sousa-Filho et al., 2020). In summary, this study supports previous research by demonstrating that a blend of reflective, experiential, and collaborative learning methods effectively promotes entrepreneurial drives. The results highlight the need to combine cognitive, emotional, and social elements to shape entrepreneurial intentions. Integrating hands-on experiences, critical reflection, and teamwork in entrepreneurship education programs can cultivate an atmosphere where students are motivated not just to chase social entrepreneurship but also to have the tools and support necessary to make their intentions a reality. This study offers practical insights for educators and policymakers seeking to enhance entrepreneurship education and to nurture future social entrepreneurs.

6. Conclusions

This study offers comprehensive insights into the impact of entrepreneurship education (EE) on students’ social entrepreneurial intentions (SEIs), providing evidence that a well-structured, hands-on, and reflective approach significantly shapes students’ motivation to pursue social entrepreneurial ventures. By analyzing the effects of various weekly activities on a 13-week entrepreneurship course, the research underscores the importance of diverse pedagogical methods in influencing students’ entrepreneurial mindset and decisions.

The study emphasizes that experiential learning activities, such as teamwork, brainstorming, and practical workshops, are key drivers in boosting social entrepreneurial intention. Specifically, the activities in Weeks 1, 5, 10, and 11, which focused on team formation, idea generation, and business frameworks, were associated with notable increases in EI. These results align with existing research highlighting the importance of practical engagement in entrepreneurship education. Team-based learning and hands-on exercises foster essential skills such as problem-solving, creativity, and resilience, which are integral to entrepreneurial success. Furthermore, students felt more equipped to act on their entrepreneurial ambitions after applying theoretical knowledge in workshops, reinforcing the idea that EE should bridge the gap between theory and practice.

Reflective practices, particularly diary entries in Week 9, provided an opportunity for students to assess their progress and evaluate their evolving entrepreneurial intention. This self-reflection boosted their confidence and clarified their goals. Reflective learning plays a critical role in reinforcing students’ self-awareness, helping them to identify their strengths and weaknesses as aspiring entrepreneurs. By reflecting on their experiences and growth, students are better able to connect their intentions with concrete actions, which is crucial for overcoming the intention–action gap in entrepreneurship.

The study found that the greatest surge in SEI occurred during Week 8, when the focus was on social entrepreneurship and sustainability. This thematic focus on societal impact resonated strongly with students, with 72% reporting increased entrepreneurial intention. This suggests that incorporating social impact into entrepreneurship education can significantly enhance students’ motivation to pursue entrepreneurial ventures that address societal challenges. The connection between social entrepreneurship and students’ values is particularly significant, as it aligns with growing global interest in businesses that prioritize social good alongside profit.

Weeks 6 and 7, which centered on legal and financial planning topics, were associated with temporary declines in SEI, with 16% and 15% of students, respectively, reporting reduced intention. These findings suggest that while students recognize the importance of these topics, they can also be intimidating and discouraging, especially for those with limited exposure to such complex aspects of entrepreneurship. As noted in the study, such challenges are inevitable in the entrepreneurial journey, but they should be accompanied by adequate support systems, such as mentorship and case studies, to mitigate the negative impact on student motivation. Including these topics in the curriculum is essential, but finding ways to deliver them in a less overwhelming and more engaging manner is critical for maintaining students’ enthusiasm.

The findings underline the importance of social and emotional factors in shaping entrepreneurial intentions. Activities undertaken in Weeks 1 and 5, which involved team-based work, not only enhanced students’ entrepreneurial skills but also fostered a sense of community and support among peers. These team dynamics are vital for maintaining motivation throughout the course, as students often rely on emotional encouragement and shared experiences to overcome challenges. The sense of belonging and collective effort created during these weeks reinforced students’ commitment to entrepreneurship and highlighted the importance of peer support in sustaining long-term entrepreneurial aspirations.

Overall, the study reinforces the idea that entrepreneurship education should be a holistic experience, integrating a variety of learning methods. The most successful weeks involved a blend of experiential, reflective, and collaborative activities, which contributed to positive shifts in entrepreneurial intentions. However, the research also highlights that students’ emotional responses and the challenges they face must be carefully considered. Difficult topics, such as legal and financial planning, can temporarily reduce motivation, but they also serve as essential components of entrepreneurship education that help students develop a realistic understanding of the complexities of starting and managing a business. Therefore, it is crucial to provide adequate support structures during these challenging periods, ensuring that students remain engaged and do not become discouraged.

While this study provides valuable insights into the impact of different teaching methods on SEI, it also suggests avenues for further research. Future studies should explore the long-term effects of entrepreneurship education by tracking students’ entrepreneurial actions after completing the course, helping to understand the translation of intention into practice. Additionally, research involving diverse student populations and learning environments could provide a broader understanding of how EE affects entrepreneurial intention across different contexts. Investigating the role of institutional support systems, such as incubators and accelerators, could further enhance our understanding of how to sustain entrepreneurial goals after the formal educational experience has concluded. Finally, extra elements that can affect social entrepreneurial intention (SEI), such as gender disparities and other personal traits, could be taken into account to further enhance the analysis. A more thorough participant segmentation could be used in future studies to further explore this issue. While this study confirms the effectiveness of reflective diaries in tracking social entrepreneurial intention development, future research should explore how this method compares to other pedagogical tools. A comparative analysis of various EE techniques—such as simulations, business incubators, and mentorship programs—could provide deeper insights into the most impactful strategies for fostering social entrepreneurship.

In conclusion, this study provides strong evidence that entrepreneurship education can significantly influence students’ social entrepreneurial intentions, particularly when it involves a mix of experiential, reflective, and collaborative learning methods. The findings highlight the effectiveness of hands-on activities, social entrepreneurship, and reflective practices in cultivating a strong entrepreneurial mindset. While challenging topics such as financial and legal planning can temporarily reduce enthusiasm, they remain essential for providing students with a realistic understanding of the entrepreneurial process. By balancing challenging content with supportive teaching strategies, universities can better prepare students for the realities of entrepreneurship and inspire the next generation of innovative social business leaders.

Finally, while the present study confirms the impact of EE on fostering SEI, it also highlights areas for further development. First, educators should place emphasis on experiential learning through real social enterprise projects, mentorship initiatives, and visits to social enterprises. Second, reflective learning practices, such as the use of diaries, should be integrated into entrepreneurship courses to help students track their thoughts, emotions, and intentions or motivations. Lastly, universities should enhance the institutional support for social entrepreneurship initiatives through incubators, funding opportunities, and collaborations. The implementation of such strategies will foster a new generation of social entrepreneurs properly equipped to meet global challenges.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.X. and A.S.; methodology, P.X.; software, P.X.; validation, P.X. and A.S.; formal analysis, P.X. and A.S.; investigation, P.X.; resources, P.X. and A.S.; data curation, P.X.; writing—original draft preparation, P.X. and A.S.; writing—review and editing, A.S.; visualization, P.X.; supervision, A.S.; project administration, P.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This research was conducted as part of a postdoctoral study and was approved in accordance with the regulations of the Department of Business Administration at the University of West Attica. Ethical oversight was provided by the department’s internal convention, which adheres to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The specific approval details are maintained by the department, as the study did not require formal approval by an external Institutional Review Board.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ahmad, S., & Bajwa, I. A. (2023). The role of social entrepreneurship in socio-economic development: A meta-analysis of the nascent field. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies, 15(1), 133–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, T., Chandran, V. G. R., Klobas, J. E., Liñán, F., & Kokkalis, P. (2020). Entrepreneurship education programmes: How learning, inspiration, and resources affect intentions for new venture creation in a developing economy. The International Journal of Management Education, 18(1), 100327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. (2005). Attitudes, personality, and behaviour. Open University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Qudah, A. A., Al-Okaily, M., & Alqudah, H. (2022). The relationship between social entrepreneurship and sustainable development from an economic growth perspective: 15 ‘RCEP’ countries. Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment, 12(1), 44–61. [Google Scholar]

- Asghar, M. Z., Seitamaa-Hakkarainen, P., & Nada, N. (2016). An analysis of the relationship between the components of entrepreneurship education and the antecedents of theory of planned behavior. Pakistan Journal of Commerce and Social Sciences, 10(1), 45–68. [Google Scholar]

- Astiana, M., Malinda, M., Nurbasari, A., & Margaretha, M. (2022). Entrepreneurship education increases entrepreneurial intention among undergraduate students. European Journal of Educational Research, 11(2), 995–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autio, E., Keeley, R. H., Klofsten, M., Parker, G. C., & Hay, M. (2001). Entrepreneurial intent among students in Scandinavia and in the USA. Enterprise and Innovation Management Studies, 2(2), 145–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayikoru, M., Tribe, J., & Airey, D. (2009). Reading tourism education: Neoliberalism unveiled. Annals of Tourism Research, 36(2), 191–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, B. Y. (2022). A study on entrepreneurship and the effects of entrepreneurship education program on entrepreneurship intention and entrepreneurship behavior of university students. Asia-Pacific Journal of Business Venturing and Entrepreneurship, 17(4), 115–125. [Google Scholar]

- Bae, T. J., Qian, S., Miao, C., & Fiet, J. O. (2014). The relationship between entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intentions: A meta–analytic review. Entrepreneurship theory and practice, 38(2), 217–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bischoff, K., Volkmann, C. K., & Audretsch, D. B. (2018). Stakeholder collaboration in entrepreneurship education: An analysis of the entrepreneurial ecosystems of European higher educational institutions. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 43, 20–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogatyreva, K., & Shirokova, G. (2017). From entrepreneurial aspirations to founding a business: The case of Russian students. Фoрсайт, 11(3 (eng)), 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brüne, N., & Lutz, E. (2020). The effect of entrepreneurship education in schools on entrepreneurial outcomes: A systematic review. Management Review Quarterly, 70(2), 275–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chell, E. (2007). Social enterprise and entrepreneurship: Towards a convergent theory of the entrepreneurial process. International Small Business Journal, 25(1), 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cope, J. (2005). Toward a dynamic learning perspective of entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 29(4), 373–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidsson, P., & Honig, B. (2003). The role of social and human capital among nascent entrepreneurs. Journal of Business Venturing, 18(3), 301–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, K. (1973). The case for and against business assumption of social responsibilities. Academy of Management Journal, 16, 312–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defourny, J., & Nyssens, M. (2010). Conceptions of social enterprise and social entrepreneurship in Europe and the United States: Convergences and divergences. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, 1(1), 32–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sousa-Filho, J. M., Matos, S., da Silva Trajano, S., & de Souza Lessa, B. (2020). Determinants of social entrepreneurial intentions in a developing country context. Journal of Business Venturing Insights, 14, e00207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dohse, D., & Walter, S. G. (2010). The role of entrepreneurship education and regional context in forming entrepreneurial intentions. Document de Treball de l’IEB, 2010/18. Institut d’Economia de Barcelona (IEB). [Google Scholar]

- Esfandiar, K., Sharifi-Tehrani, M., Pratt, S., & Altinay, L. (2019). Understanding entrepreneurial intentions: A developed integrated structural model approach. Journal of Business Research, 94, 172–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, M. S. (2018). Modelling the significance of social support and entrepreneurial skills for determining entrepreneurial behaviour of individuals: A structural equation modelling approach. World Journal of Entrepreneurship, Management and Sustainable Development, 14(3), 242–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayolle, A. (2018). Personal views on the future of entrepreneurship education. In A research agenda for entrepreneurship education (pp. 127–138). Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Fayolle, A., & Gailly, B. (2009). Assessing the impact of entrepreneurship education: A methodology and three experiments from French engineering schools. In Handbook of university-wide entrepreneurship education. Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Fowler, A. (2000). NGDOs as a moment in history: Beyond aid to social entrepreneurship or civic innovation? Third World Quarterly, 21(4), 637–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurel, E., Altinay, L., & Daniele, R. (2010). Tourism students’ entrepreneurial intentions. Annals of Tourism Research, 37(3), 646–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haase, H., & Lautenschläger, A. (2011). The ‘teachability dilemma’ of entrepreneurship. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 7, 145–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddoud, M. Y., Onjewu, A. K. E., Al-Azab, M. R., & Elbaz, A. M. (2022). The psychological drivers of entrepreneurial resilience in the tourism sector. Journal of Business Research, 141, 702–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, H., Sade, A. B., & Rahman, M. S. (2020). Shaping entrepreneurial intention among youngsters in Malaysia. Journal of Humanities and Applied Social Sciences, 2(3), 235–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hägg, G. (2022). Prudent entrepreneurial graduates that take intelligent action. In How to develop entrepreneurial graduates, ideas and ventures (pp. 15–24). Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Heinonen, J. (2007). An entrepreneurial-directed approach to teaching corporate entrepreneurship at university level. Education + Training, 49(4), 310–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, P. M., & Levin, D. Z. (1999). Umbrella advocates versus validity police: A life-cycle model. Organization Science, 10(2), 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ip, C. Y., Wu, S. C., Liu, H. C., & Liang, C. (2017). Revisiting the antecedents of social entrepreneurial intentions in Hong Kong. International Journal of Educational Psychology, 6(3), 301–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S. (2000). Literature review on social entrepreneurship. Canadian Centre for Social Entrepreneurship, 16(23), 96–106. [Google Scholar]

- Jovičić-Vuković, A., Jošanov-Vrgović, I., Jovin, S., & Papić-Blagojević, N. (2020). Socio-demographic characteristics and students’ entrepreneurial intentions. Stanovnistvo, 58(2), 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanwal, S., Pitafi, A. H., Pitafi, A., Nadeem, M. A., Younis, A., & Chong, R. (2019). China–Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) development projects and entrepreneurial potential of locals. Journal of Public Affairs, 19(4), e1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavoura, A., & Andersson, T. (2016). Applying Delphi method for strategic design of social entrepreneurship. Library Review, 65(3), 185–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kefis, V., & Xanthopoulou, P. (2015). Teaching entrepreneurship through e-learning: The implementation in schools of social sciences and humanities in Greece. International Journal of Sciences, 4(8), 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kimakwa, S., Gonzalez, J. A., & Kaynak, H. (2023). Social entrepreneur servant leadership and social venture performance: How are they related? Journal of Business Ethics, 182(1), 95–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, D. A. (2014). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. FT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S. H., & Wong, P. K. (2004). An exploratory study of technopreneurial intentions: A career anchor perspective. Journal of Business Venturing, 19(1), 7–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitch, C. M., & Harrison, R. T. (2016). Identity, identity formation and identity work in entrepreneurship: Conceptual developments and empirical applications. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 28(3-4), 177–190. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L., & Wu, D. (2019). Entrepreneurial education and students’ entrepreneurial intention: Does team cooperation matter? Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research, 9(1), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liñán, F. (2004). Intention-based models of entrepreneurship education. Piccola Impresa/Small Business, 3(1), 11–35. [Google Scholar]

- Liñán, F., & Chen, Y. W. (2009). Development and cross–cultural application of a specific instrument to measure entrepreneurial intentions. Entrepreneurship theory and practice, 33(3), 593–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liñán, F., & Fayolle, A. (2015). A systematic literature review on entrepreneurial intentions: Citation, thematic analyses, and research agenda. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 11, 907–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Meri, A., Alonso-Muñoz, L., & Casero-Ripollés, A. (2021). What is behind the entrepreneurship intention in journalism? Entrepreneur typologies based on student perceptions. Journalism Practice, 15(3), 402–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorz, M. (2011). The impact of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial intention [Ph.D. Thesis, University of St. Gallen]. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, Y., Chen, Y., Sha, Y., Wang, J., An, L., Chen, T., Huang, X., Huang, Y., & Huang, L. (2021). How entrepreneurship education at universities influences entrepreneurial intention: Mediating effect based on entrepreneurial competence. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 655868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mair, J., & Martí, I. (2006). Social entrepreneurship research: A source of explanation, prediction, and delight. Journal of World Business, 41(1), 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marire, E., Mafini, C., & Dhurup, M. (2017). Drivers of entrepreneurial intentions amongst generation Y students in Zimbabwe. International Journal of Business and Management Studies, 9(2), 17–34. [Google Scholar]

- Matlay, H. (2005). Entrepreneurship education in UK business schools: Conceptual, contextual, and policy considerations. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 12(4), 627–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, R. K., Busenitz, L., Lant, T., McDougall, P. P., Morse, E. A., & Smith, J. B. (2002). Toward a theory of entrepreneurial cognition: Rethinking the people side of entrepreneurship research. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 27(2), 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, A. (2006). A contextualization of entrepreneurship. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 12(4), 192–209. [Google Scholar]

- Mulgan, G. (2006). Cultivating the other invisible hand of social entrepreneurship: Comparative advantage, public policy, and future research priorities. In Social entrepreneurship: New models of sustainable social change (pp. 74–96). Oxford Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz, P., & Kimmitt, J. (2019). Rural entrepreneurship in place: An integrated framework. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 31(9–10), 842–873. [Google Scholar]

- Nabi, G., Walmsley, A., Liñán, F., Akhtar, I., & Neame, C. (2018). Does entrepreneurship education in the first year of higher education develop entrepreneurial intentions? The role of learning and inspiration. Studies in Higher Education, 43(3), 452–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndofirepi, T. M., & Rambe, P. (2018). A qualitative approach to the entrepreneurial education and intentions nexus: A case of Zimbabwean polytechnic students. The Southern African Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business Management, 10(1), a81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neneh, B. N. (2014). An assessment of entrepreneurial intention among university students in Cameroon. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 5(20), 542–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojogbo, L. U., Idemobi, E. I., & Ngige, C. D. (2016). The impact of entrepreneurship education on the development of entrepreneurial career intentions and actions. International Journal of Entrepreneurship, 1(1), 27–49. [Google Scholar]

- Oosterbeek, H., Van Praag, M., & Ijsselstein, A. (2010). The impact of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurship skills and motivation. European Economic Review, 54(3), 442–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papagiannis, G. D. (2018). Entrepreneurship education programs: The contribution of courses, seminars, and competitions to entrepreneurial activity decision and to entrepreneurial spirit and mindset of young people in Greece. Journal of Entrepreneurship Education, 21(1), 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, W., Lee, H., Ghobadian, A., O’regan, N., & James, P. (2015). Social innovation and social entrepreneurship: A systematic review. Group & Organization Management, 40(3), 428–461. [Google Scholar]

- Prabhu, G. N. (1999). Social entrepreneurial leadership. Career Development International, 4(3), 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puni, A., Anlesinya, A., & Korsorku, P. D. A. (2018). Entrepreneurial education, self-efficacy, and intentions in Sub-Saharan Africa. African Journal of Economic and Management Studies, 9(4), 492–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raposo, M., & Do Paço, A. (2011). Entrepreneurship and education—Links between education and entrepreneurial activity. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 7, 143–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reissová, A., Šimsová, J., Sonntag, R., & Kučerová, K. (2020). The influence of personal characteristics on entrepreneurial intentions: International comparison. Entrepreneurial Business and Economics Review, 8(4), 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahinidis, A. G., Polychronopoulos, G., & Kallivokas, D. (2019). Entrepreneurship education impact on entrepreneurial intention among tourism students: A longitudinal study. In Strategic innovative marketing and tourism: 7th ICSIMAT, Athenian Riviera, Greece, 2018 (pp. 1245–1250). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Shahid, M. S., & Ahsen, S. R. (2021). Linking entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intentions: An interactive effect of social and personal factors. International Journal of Learning and Change, 13(1), 14–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirokova, G., Osiyevskyy, O., & Bogatyreva, K. (2016). Exploring the intention–behavior link in student entrepreneurship: Moderating effects of individual and environmental characteristics. European Management Journal, 34(4), 386–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steyaert, C. (2007). ‘Entrepreneuring’ as a conceptual attractor? A review of process theories in 20 years of entrepreneurship studies. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 19(6), 453–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storr, V. H., Haeffele, S., Lofthouse, J. K., & Hobson, A. (2022). Entrepreneurship during a pandemic. European Journal of Law and Economics, 54(1), 83–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sultan, M. F., Maqsood, A., & Sharif, H. M. (2016). Impact of entrepreneurial education on students’ entrepreneurial intentions. KASBIT Business Journal, 9(1), 131–153. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, E. R. (2009). Individual entrepreneurial intent: Construct clarification and development of an internationally reliable metric. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(3), 669–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, P., Bhat, A. K., & Tikoria, J. (2017). Predictors of social entrepreneurial intention: An empirical study. South Asian Journal of Business Studies, 6(1), 53–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tleuberdinova, A., Shayekina, Z., Salauatova, D., & Pratt, S. (2021). Macro-economic factors influencing tourism entrepreneurship: The case of Kazakhstan. The Journal of Entrepreneurship, 30(1), 179–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, A. T., & Von Korflesch, H. (2016). A conceptual model of social entrepreneurial intention based on the social cognitive career theory. Asia Pacific Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 10(1), 17–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vodă, A. I., & Florea, N. (2019). Impact of personality traits and entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial intentions of business and engineering students. Sustainability, 11(4), 1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waddock, S. A., & Post, J. E. (1991). Social entrepreneurs and catalytic change. Public Administration Review, 51(5), 393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, S. L. (1999). Social entrepreneurship: The role of social purpose enterprises in facilitating community economic development. Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship, 4(2), 153. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D. J. (2020). When do return migrants become entrepreneurs? The role of global social networks and institutional distance. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 14(2), 125–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westhead, P., & Solesvik, M. Z. (2016). Entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intention: Do female students benefit? International Small Business Journal, 34(8), 979–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, F., Kickul, J., & Marlino, D. (2007). Gender, entrepreneurial self–efficacy, and entrepreneurial career intentions: Implications for entrepreneurship education. Entrepreneurship theory and practice, 31(3), 387–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xanthopoulou, P., & Sahinidis, A. (2024). Students’ entrepreneurial intention and its influencing factors: A systematic literature review. Administrative Sciences, 14(5), 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xanthopoulou, P., Sahinidis, A., Kavoura, A., & Antoniadis, I. (2024a). Shifting Mindsets: Changes in Entrepreneurial Intention Among University Students. Administrative Sciences, 14(11), 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xanthopoulou, P., Sahinidis, A., & Paganou, S. (2024b, September 26–27). Inside the entrepreneurial mind: A diary research on the evolution of students’ entrepreneurial intentions. 19th European Conference on Innovation and Entrepreneurship, ECIE 2024, Paris, France. [Google Scholar]

- Xanthopoulou, P. I., & Sahinidis, A. G. (2022). Shaping entrepreneurial intentions: The moderating role of entrepreneurship education. Balkan & Near Eastern Journal of Social Sciences, 8, 116–121. [Google Scholar]

- Young, D. R. (1998). Commercialism in nonprofit social service associations: Its character, significance, and rationale. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management: The Journal of the Association for Public Policy Analysis and Management, 17(2), 278–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S. A., Gedajlovic, E., Neubaum, D. O., & Shulman, J. M. (2009). A typology of social entrepreneurs: Motives, search processes, and ethical challenges. Journal of Business Venturing, 24(5), 519–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeyen, A., Beckmann, M., Mueller, S., Dees, J. G., Khanin, D., Krueger, N., Patrick, J., Murphy, F. S., Scarlata, M., Walske, J., & Zacharakis, A. (2013). Social entrepreneurship and broader theories: Shedding new light on the ‘bigger picture’. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, 4(1), 88–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J. A., O’Kane, C., & Chen, G. (2020). Business ties, political ties, and innovation performance in Chinese industrial firms: The role of entrepreneurial orientation and environmental dynamism. Journal of Business Research, 121, 254–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).