The Old, the New, and the Used One—Assessing Legacy in Family Firms

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Methodology

3.1. Selecting Cases and Collecting Data

- They must be at least 150–200 years old (spanning at least three generations);

- A descendant of the founder must manage them;

- The family must still own the company or be the majority shareholder;

- The companies must be financially healthy.

3.2. Analyzing Data

4. Results and Discussions

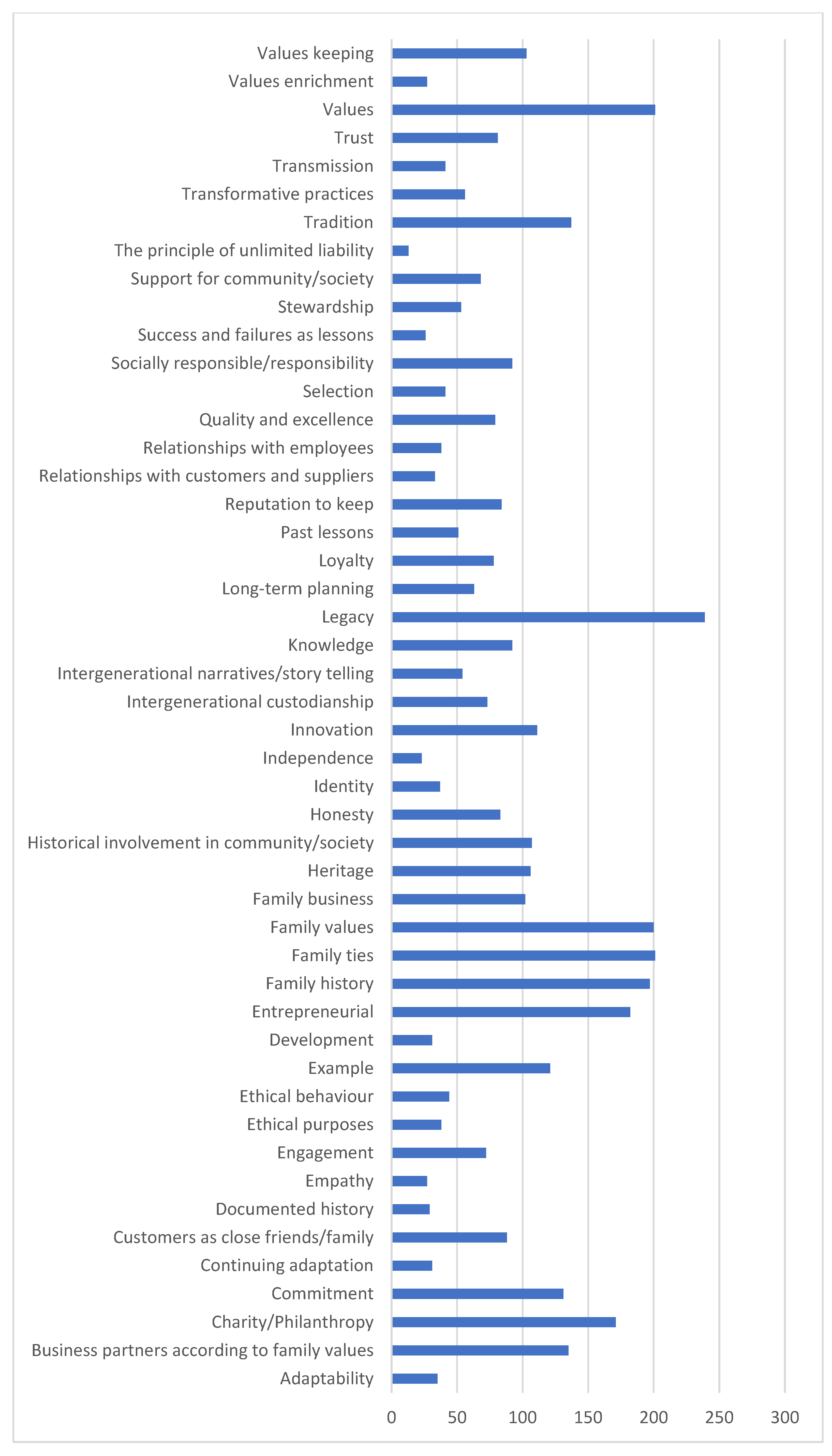

4.1. Legacy in Family Business: Important Elements

4.1.1. Legacy of Knowledge

4.1.2. Legacy of Values

4.1.3. Legacy of Relationships

4.1.4. Legacy of Contribution to Society

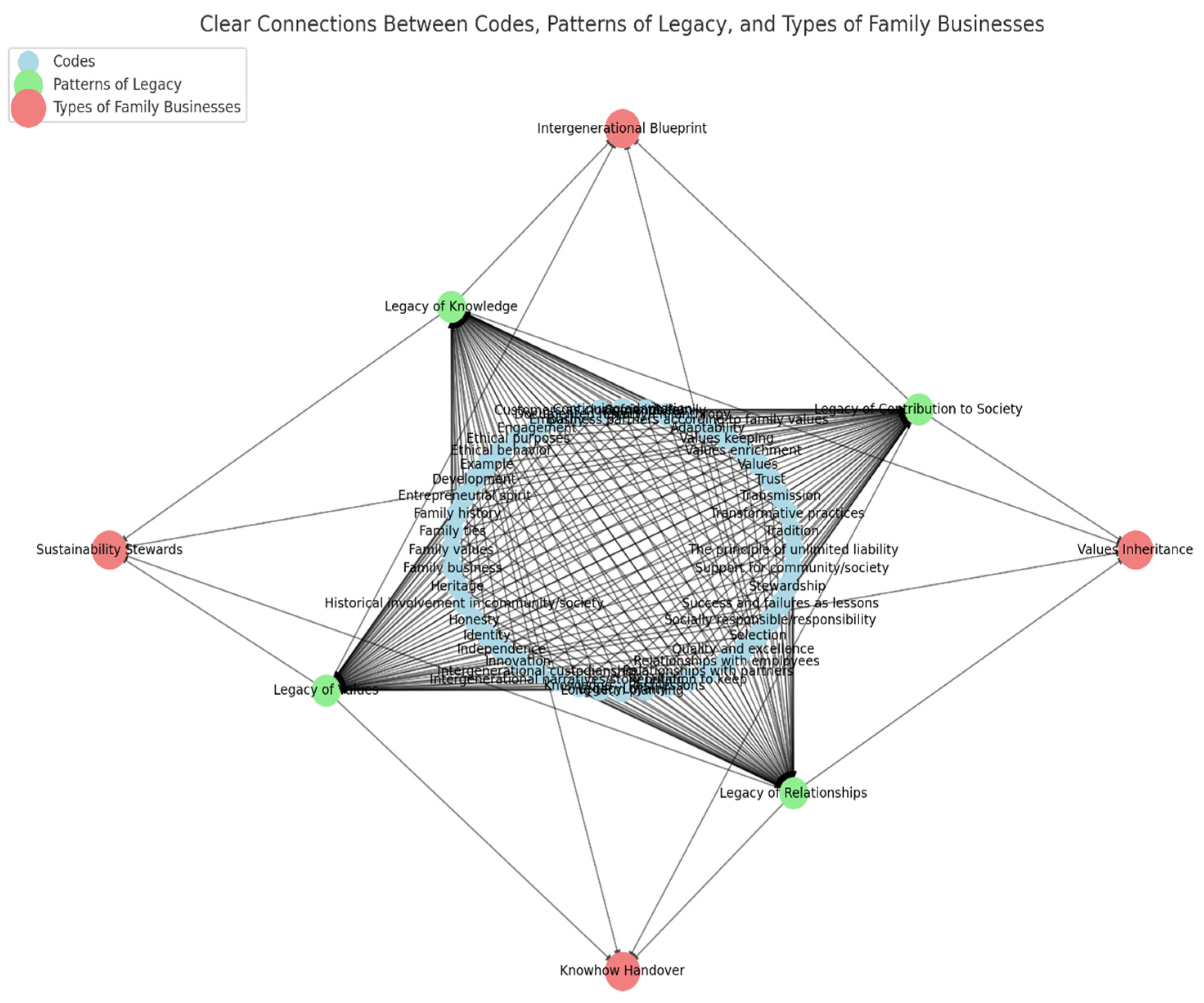

4.2. The Role of Legacy in Doing Family Business: From Patterns of Legacy to Type of Business

- (1)

- Sustainability Stewards

- (2)

- Values Inheritance

- (3)

- Knowhow Handover

- (4)

- Intergenerational Blueprint

- Regularly share and discuss business and family stories with the younger generation. This ensures the legacy is understood, appreciated, and carried forward. Encourage intergenerational dialogue and involve younger family members in business operations when possible.

- Create a workplace environment that promotes respect, gratitude, and open communication. Regularly solicit feedback from employees and involve them in decision-making processes, such as through design meetings. Ensure they feel valued and integral to the business’s success.

- While it is essential to honor and preserve traditional practices, always stay open to new ideas and technologies. Collaborate with external talents, be they artists or technologists, to bring fresh perspectives and innovative solutions to the business.

- When considering new projects or investments, always weigh the potential benefits against the risks. Ensure that even in the event of a setback, the company’s foundation remains intact.

- The foundation of any business, especially those that are family-owned, lies in the values imparted and the attitude towards risk. In a business where decisions can have significant personal financial implications, understanding and mitigating risks becomes crucial. This means running the business from a long-term perspective and ensuring that all parties involved have a correct attitude toward risk.

- Drawing examples from the history of the business can be instrumental in understanding their current way of operating. The successes and failures of the past can serve as valuable lessons and can help in making informed decisions.

- Viewing the business as something that needs to be handed down in better shape to the next generation is vital. This requires a long-term vision and understanding that one’s role is not just about immediate profit but ensuring the business thrives for future generations.

- Even if a business has a rich history, it is essential to adapt to changing times and innovate constantly. Staying in sync with customer expectations and evolving accordingly ensures the business remains relevant and sustainable.

- Ethics and values should be the underpinnings of any business decision. This not only ensures the trust of customers but also aligns the business with broader societal goals. Whether it is about being good bankers or good citizens, having a clear purpose and staying true to it is crucial.

- To build a long-lasting relationship with clients and create loyalty, quality plays a pivotal role. Trust is built over time and through the consistent delivery of quality products or services. This trust becomes the foundation of a successful, long-term relationship with the client.

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| 1st-Order Concept Codes | 2nd-Order Concepts Patterns of Legacy 2nd Research Question | Aggregate Dimensions Type of Family Business 3rd Research Question |

|---|---|---|

| Adaptability | Legacy of knowledge | Knowhow Handover |

| Business partners according to family values | Legacy of values Legacy of relationships | Values Inheritance Intergenerational Blueprint |

| Charity/philanthropy | Legacy of contribution to society Legacy of values | Sustainability Stewards Values Inheritance |

| Commitment | Legacy of contribution to society Legacy of knowledge Legacy of values | Sustainability Stewards Knowhow Handover Values Inheritance |

| Continuing adaptation | Legacy of knowledge Legacy of values | Knowhow Handover Values inheritance |

| Customers as close friends/family | Legacy of values Legacy of relationships | Values Inheritance Intergenerational Blueprint |

| Documented history | Legacy of relationships Legacy of knowledge | Intergenerational Blueprint Knowhow Handover |

| Empathy | Legacy of contribution to society Legacy of values | Sustainability Stewards Values Inheritance |

| Engagement | Legacy of contribution to society Legacy of relationships Legacy of knowledge | Sustainability Stewards Intergenerational Blueprint Knowhow Handover |

| Ethical purposes | Legacy of contribution to society Legacy of values Legacy of relationships | Sustainability Stewards Values Inheritance Intergenerational Blueprint |

| Ethical behavior | Legacy of contribution to society Legacy of values Legacy of relationships | Sustainability Stewards Values Inheritance Intergenerational Blueprint |

| Example | Legacy of values Legacy of contribution to society Legacy of knowledge | Values Inheritance Sustainability Stewards Knowhow Handover |

| Development | Legacy of values Legacy of knowledge | Values Inheritance Knowhow Handover |

| Entrepreneurial spirit | Legacy of knowledge Legacy of values | Knowhow Handover Values Inheritance |

| Family history | Legacy of relationships Legacy of values | Intergenerational Blueprint Values Inheritance |

| Family ties | Legacy of relationships Legacy of values | Intergenerational Blueprint Values Inheritance |

| Family values | Legacy of relationships Legacy of values | Intergenerational Blueprint Values Inheritance |

| Family business | Legacy of relationships Legacy of contribution to society | Intergenerational Blueprint Sustainability Stewards |

| Heritage | Legacy of relationships Legacy of values | Intergenerational Blueprint Values Inheritance |

| Historical involvement in community/society | Legacy of contribution to society Legacy of values | Sustainability Stewards Values Inheritance |

| Honesty | Legacy of values Legacy of relationships | Values Inheritance Intergenerational Blueprint |

| Identity | Legacy of values Legacy of relationships | Values Inheritance Intergenerational Blueprint |

| Independence | Legacy of values | Values Inheritance |

| Innovation | Legacy of knowledge | Knowhow Handover |

| Intergenerational custodianship | Legacy of values Legacy of relationships | Values Inheritance Intergenerational Blueprint |

| Intergenerational narratives/storytelling | Legacy of relationships Legacy of values | Intergenerational Blueprint Values Inheritance |

| Knowledge | Legacy of knowledge | Knowhow Handover |

| Legacy | Legacy of relationships Legacy of values | Intergenerational Blueprint Values Inheritance |

| Long-term planning | Legacy of knowledge Legacy of values | Knowhow Handover Values Inheritance |

| Loyalty | Legacy of values Legacy of relationships | Values Inheritance Intergenerational Blueprint |

| Past lessons | Legacy of knowledge | Knowhow Handover |

| Reputation to keep | Legacy of values Legacy of relationships | Values Inheritance Intergenerational Blueprint |

| Relationships with partners | Legacy of relationships Legacy of values | Intergenerational Blueprint Values Inheritance |

| Relationships with employees | Legacy of relationships Legacy of values | Intergenerational Blueprint Values Inheritance |

| Quality and excellence | Legacy of values Legacy of knowledge | Values Inheritance Knowhow Handover |

| Selection | Legacy of knowledge | Knowhow Handover |

| Socially responsible/responsibility | Legacy of contribution to society Legacy of values | Sustainability Stewards Values Inheritance |

| Success and failures as lessons | Legacy of knowledge | Knowhow Handover |

| Stewardship | Legacy of contribution to society Legacy of values | Sustainability Stewards Values Inheritance |

| Support for community/society | Legacy of contribution to society Legacy of values | Sustainability Stewards Values Inheritance |

| The principle of unlimited liability | Legacy of values Legacy of contribution to society | Values Inheritance Sustainability Stewards |

| Tradition | Legacy of values Legacy of relationships | Values Inheritance Intergenerational Blueprint |

| Transformative practices | Legacy of knowledge Legacy of relationships | Knowhow Handover Intergenerational Blueprint |

| Transmission | Legacy of relationships | Intergenerational Blueprint |

| Trust | Legacy of values Legacy of relationships | Values Inheritance Intergenerational Blueprint |

| Values | Legacy of values | Values Inheritance |

| Values enrichment | Legacy of values | Values Inheritance |

| Values keeping | Legacy of values | Values Inheritance |

References

- Alderson, K. (2015). Conflict management and resolution in family-owned businesses. Journal of Family Business Management, 5, 140–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arditto, L., Cambra-Fierro, J. J., Fuentes-Blasco, M., Jaraba, A. O., & Vázquez-Carrasco, R. (2020). How does customer perception of salespeople influence the relationship? A study in an emerging economy. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 54, 101952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardyan, E., Sutrisno, T. F. C. W., & Padmawidjaja, L. (2023). New value creation and family business sustainability: Identification of an intergenerational conflict resolution strategy. Heliyon, 9(5), e15634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arjona, J. R. (2008). Ethical capital: Tool for competitive advantage in SMEs. Journal of Business & Economics Research, 6(1). [Google Scholar]

- Aronoff, C. E., & Ward, J. L. (2000). Family business values: How to assure a legacy of continuity and success. Business Owner Resources. [Google Scholar]

- Austin, J. L. (1962). How to do things with words. Harvard Univ. Press. [Google Scholar]

- Baltazar, J. R., Fernandes, C. I., Ramadani, V., & Hughes, M. (2023). Family business succession and innovation: A systematic literature review. Review of Managerial Science, 17, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barad, K. (2003). Posthumanist performativity: Toward an understanding of how matter comes to matter. Signs, 28(3), 801–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbera, F., Stamm, I., & DeWitt, R.-L. (2018). The development of an entrepreneurial legacy: Exploring the role of anticipated futures in transgenerational entrepreneurship. Family Business Review, 31(3), 352–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basco, R. (2014). Exploring the influence of the family upon firm performance: Does strategic behaviour matter? International Small Business Journal, 32, 967–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baù, M., Hellerstedt, K., Nordqvist, M., & Wennberg, K. (2013). Succession in Family Firms. In The landscape of family business. Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergfeld, A. F., & Bergfeld, M. M. (2022). Next-generation entrepreneurial identity in family business systems: The influence of role changing events on the understanding of legacy, individual identity, and transgenerational entrepreneurship of next-generation family business principals. Thunderbird International Business Review, 65(4), 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrone, P., Cruz, C., & Gomez-Mejia, L. R. (2012). Socioemotional wealth in family firms: Theoretical dimensions, assessment approaches, and agenda for future research. Family Business Review, 25(3), 258–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, B., Welsch, H., Astrachan, J., & Pistrui, D. (2002). Family business research: The evolution of an academic field. Family Business Review, 15, 337–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, B., Royer, S., Pei, R., & Zhang, X. (2015). Knowledge transfer in family business successions. Journal of Family Business Management, 5, 17–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera-Suárez, K., Saá-Pérez, P., & García-Almeida, D. (2001). The succession process from a resource-and knowledge-based view of the family firm. Family Business Review, 14(1), 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camisón-Zornoza, C., Forés-Julián, B., Puig-Denia, A., & Camisón-Haba, S. (2020). Effects of ownership structure and corporate and family governance on dynamic capabilities in family firms. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 16(4), 1393–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlock, R. S., & Ward, J. L. (2001). Strategic planning for the family business: Parallel planning to unite the family and business. Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Carney, M. (2005). Corporate governance and competitive advantage in family-controlled firms. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 29(3), 249–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceja, L., Agulles, R., & Tàpies, J. (2010). The importance of values in family-owned firms. SSRN Electronic Journal, 875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, S., Dhir, A., Ferraris, A., & Bertoldi, B. (2021). Trust and reputation in family businesses: A systematic literature review of past achievements and future promises. Journal of Business Research, 137, 143–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirico, F., & Salvato, C. (2008). Knowledge integration and dynamic organizational adaptation in family firms. Family Business Review, 21(2), 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrisman, J. J., Chua, J. H., & Litz, R. A. (2003). A unified systems perspective of family firm performance: An extension and integration. Family Business Review, 16(4), 211–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrisman, J. J., Chua, J. H., Sharma, P., & Yoder, T. R. (2005). Trends and directions in the development of a strategic management theory of the family firm. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 29(5), 555–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, V., & Braun, V. (2017). Thematic analysis. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 12(3), 297–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conz, E., Denicolai, S., & De Massis, A. (2023). Preserving the longevity of long-lasting family businesses: A multilevel model. Journal of Management and Governance, 28, 707–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F., Francis Gnanasekar, M. B., & Parayitam, S. (2021). Trust and product as moderators in online shopping behavior: Evidence from India. South Asian Journal of Marketing, 2(1), 28–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Carmen García Arroyo, L., Márquez, M. G., Fuentes, M. P. Q., & Pérez, M. G. (2020). The successor training as a success factor in the management and continuity of the family business. European Scientific Journal ESJ, 16(31), 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgosha, M. S., Hajiheydari, N., & Talafidaryani, M. (2022). Discovering IoT implications in business and management: A computational thematic analysis. Technovation, 118, 102236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, B. (1999). The family factor: The impact of family relationship dynamics on business-owning families during transitions. Family Business Review, 12(1), 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyer, J. H., & Singh, H. (1998). The relational view: Cooperative strategy and sources of interorganizational competitive advantage. Academy of Management Review, 23(4), 660–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faßbender, K., Wiebe, A., & Bates, T. C. (2019). Physical and cultural inheritance enhance agency, but what are the origins of this concern to establish a legacy? A nationally representative twin study of Erikson’s concept of generativity. Behavior Genetics, 49(2), 244–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J. J., Fernandes, C. I., Schiavone, F., & Mahto, R. V. (2021). Sustainability in family business—A bibliometric study and a research agenda. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 173, 121077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, M., Tost, L. P., & Wade-Benzoni, K. A. (2010). The legacy motive: A catalyst for sustainable decision making in organizations. Business Ethics Quarterly, 20(2), 153–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fries, A., Kammerlander, N., & Leitterstorf, M. (2021). Leadership styles and leadership behaviors in family firms: A systematic literature review. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 12(1), 100374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gersick, K. E., Davis, J. A., McCollom Hampton, M., & Lansberg, I. (1997). Generation to generation: Life cycles of the family business. Harvard Business School Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gioia, D. A., Corley, K. G., & Hamilton, A. L. (2013). Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research: Notes on the Gioia methodology. Organizational Research Methods, 16(1), 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Mejía, L. R., Cruz, C., Berrone, P., & Castro, J. (2015). The bind that ties: Socioemotional wealth preservation in family firms. The Academy of Management Annals, 8(1), 141–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habbershon, T. G., & Williams, M. L. (1999). A resource-based framework for assessing the strategic advantages of family firms. Family Business Review, 12(1), 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handler, W. C. (1994). Succession in family businesses: A review of the research. Family Business Review, 7(2), 133–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, S. K., Hessel, H. M., & Danes, S. M. (2019). Relational processes in family entrepreneurial culture and resilience across generations. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 10(3), 100263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heino, N., Tuominen, P., & Jussila, I. (2020). Listed family firm stakeholder orientations: The critical role of value-creating family factors. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 11(4), 100376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humble, N., & Mozelius, P. (2022, May). Content analysis or thematic analysis: Similarities, differences and applications in qualitative research. In European conference on research methodology for business and management studies (Vol. 21, No. 1, pp. 76–81). Academic Conferences International Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Jaskiewicz, P., Combs, J. G., & Rau, S. B. (2015). Entrepreneurial legacy: Toward a theory of how some family firms nurture transgenerational entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Venturing, 30(1), 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaskiewicz, P., Neubaum, D. O., De Massis, A., & Holt, D. T. (2020). The adulthood of family business research through inbound and outbound theorizing. Family Business Review, 33(1), 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Josselson, R., & Lieblich, A. (Eds.). (1995). Interpreting experience: The narrative study of lives (Vol. 3). Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Kenyon-Rouvinez, D. (2001). Patterns in serial business families: Theory building through global case study research. Family Business Review, 14(3), 175–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Breton-Miller, I., & Miller, D. (2016). Family firms and practices of sustainability: A contingency view. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 7(1), 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Breton-Miller, I., Miller, D., & Steier, L. P. (2004). Toward an integrative model of FOB succession. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 28(4), 305–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Les Hénokiens. (2023). Les Hénokiens—Association internationale d’entreprises familiales au moins bicentenaires. Hénokiens. Available online: http://www.henokiens.com (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Letonja, M., Duh, M., & Zenko, Z. (2021). Knowledge transfer for innovativeness in family businesses. Serbian Journal of Management, 16, 181–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnani, G., & Gioia, D. (2023). Using the Gioia Methodology in international business and entrepreneurship research. International Business Review, 32(2), 102097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magrelli, V., Rovelli, P., Benedetti, C., Überbacher, R., & Massis, A. (2022). Generations in family business: A multifield review and future research agenda. Family Business Review, 35(1), 15–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manelli, L., Magrelli, V., Kotlar, J., Petruzzelli, A. M., & Frattini, F. (2023). Building an outward-oriented social family legacy: Rhetorical history in family business foundations. Family Business Review, 36(1), 143–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, P., Presas, P., & Simon, A. (2014). The heterogeneity of family firms in CSR engagement: The role of values. Family Business Review, 27(3), 206–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massis, A., & Rondi, E. (2020). COVID-19 and the future of family business research. Journal of Management Studies, 57(8), 1727–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D., & Le Breton-Miller, I. (2005). Managing for the long run: Lessons in competitive advantage from great family businesses. Harvard Business Press. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, D., Le Breton-Miller, I., & Scholnick, B. (2008). Stewardship vs. stagnation: An empirical comparison of small family and non-family businesses. Journal of Management Studies, 45(1), 51–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S., & Dey, A. K. (2022). Understanding and identifying ‘themes’ in qualitative case study research. South Asian Journal of Business and Management Cases, 11(3), 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Menéndez, A. M., & Casillas, J. C. (2021). How do family businesses grow? Differences in growth patterns between family and non-family firms. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 12(3), 100420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahapiet, J., & Ghoshal, S. (1998). Social capital, intellectual capital, and the organizational advantage. Academy of Management Review, 23(2), 242–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neubaum, D. O., & Payne, G. T. (2021). The centrality of family. Family Business Review, 34(1), 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pipatanantakurn, K., & Ractham, V. V. (2022). The Role of Knowledge Creation and Transfer in Family Firm Succession. Sustainability, 14(10), 5845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radu-Lefebvre, M., Davis, J. H., & Gartner, W. B. (2024). Legacy in family business: A systematic literature review and future research agenda. Family Business Review, 37(1), 18–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radu-Lefebvre, M., Ronteau, S., Lefebvre, V., & McAdam, M. (2022). Entrepreneuring as emancipation in family business succession: A story of agony and ecstasy. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 34(7–8), 582–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadani, V., Ademi, L., Ratten, V., Palalic, R., & Krueger, N. (2018). Knowledge creation and relationship marketing in family businesses: A case-study approach. In Contributions to management science (pp. 123–157). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royer, S., Simons, R., Boyd, B., & Rafferty, A. (2008). Promoting family: A contingency model of family business succession. Family Business Review, 21, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Röström, A., & Liedholm, E. (2023). Unveiling the influence of organizational culture on innovation in family businesses lessons from Sweden and Italy (p. 86). Spring. Available online: https://umu.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1772463/FULLTEXT01.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Sageder, M., Mitter, C., & Feldbauer-Durstmüller, B. (2018). Image and reputation of family firms: A systematic literature review of the state of research. Review of Managerial Science, 12(1), 335–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, X., & Muehlfeld, K. (2017). What’s so special about intergenerational knowledge transfer? Identifying challenges of intergenerational knowledge transfer. Management Revue, 28(4), 375–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweiger, N., Matzler, K., Hautz, J., & de Massis, A. (2023). Family businesses and strategic change: The role of family ownership. Review of Managerial Science, 18(10), 2981–3005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P. (2004). An overview of the field of family business studies: Current status and directions for the future. Family Business Review, 17(1), 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, D. A., & Patzelt, H. (2017). Researching at the intersection of family business and entrepreneurship. In D. A. Shepherd, & H. Patzelt (Eds.), Trailblazing in entrepreneurship: Creating new paths for understanding the field (pp. 181–208). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utami, C. W., Bernardus, D., & Sintha, G. (2017). The pattern analysis of family business succession: A study on medium scale family business in Indonesia. European Research Studies Journal, 20, 461–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegner, D. M. (1987). Transactive memory: A contemporary analysis of the group mind. In B. Mullen, & G. R. Goethals (Eds.), Theories of group behavior (pp. 185–208). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Yezza, H., Chabaud, D., & Calabrò, A. (2021). Conflict dynamics and emotional dissonance during the family business succession process: Evidence from the Tunisian context. Entrepreneurship Research Journal, 11(3), 219–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zellweger, T. M., Eddleston, K. A., & Kellermanns, F. W. (2010). Exploring the concept of familiness: Introducing family firm identity. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 1(1), 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zellweger, T. M., Kellermanns, F. W., Eddleston, K. A., & Memili, E. (2012a). Building a family firm image: How family firms capitalize on their family ties. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 3(4), 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zellweger, T. M., Nason, R., & Nordqvist, M. (2012b). From longevity of firms to transgenerational entrepreneurship of families: Introducing family entrepreneurial orientation. Family Business Review, 25, 136–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Company 1 | Beretta | 15th generations | 3388+ employees | Firearms manufacturing company |

| Company 2 | Anonym Company | 8th generations | 5300 employees | Private bank and financial services |

| Company 3 | Champagne Billecart-Salmon | 7th generations | 87 employees | Champagne houses and makers |

| Company 4 | C. Hoare & Co. | 12th generations | 201–500 employees | Banking and financial services |

| Company 5 | Anonym Company | 6th generations | around 800 employees | Jewelry makers and sellers |

| Company 1 | “And so, they pass on the passion of gun manufacturing. Only knowledgeable people like the people that work here can make those special projects come true.” |

| Company 2 | “The constant acquisition of knowledge, paired with a long-term mindset, has been key to unlocking new opportunities and strategies.” |

| Company 3 | “The first thing is: who is the family business owned and run [by]? Our family members that run the business are [only] three members out of 130 people. So, one of the key things is having the most talented people, some of them can be family members, but don’t limit yourself only to family members. And ultimately choose those that are taking a superior interest in your company…” |

| Company 4 | “You have to keep the spirit, what make an entrepreneur to go forward. Look for innovation, for transformative practices.” |

| Company 5 | “Another legacy is the vast knowledge and competence handed down from the previous generation. Of course, there’s also a certain style or way of doing things, which is shaped by individual preferences.” |

| Company 1 | “Quality Without Compromise. This core value of total commitment to quality was established by Bartolomeo Beretta almost five centuries ago and continues to be the bedrock of our Company today. As a crucial part of our Mission, it remains the unchanging key to Beretta’s worldwide success.” |

| Company 2 | “Our guiding principles are independence, long-term thinking, partnership, responsibility, and entrepreneurial spirit.” |

| Company 3 | “But for us quality, quality, quality is the key and we strongly believe that. We believe that the best way to create a trustful relationship with our clients in creating loyalty is this one.” |

| Company 4 | “So, values and attitude to risk are critical. What we see is two things, one is that we, around the values, have defined the bank’s purpose, which is to be both good bankers and good citizens. The second thing is that around values we’re looking for family members who are displaying honesty, excellence, empathy, and social responsibility.” |

| Company 5 | “Well, of course, we do have values. Let’s say we’ve chosen these values over many, many generations, and each generation learns from the one before.” “Commitment, responsibility, ethical behavior, these guide us for generation.” |

| Company 1 | “There were difficult moments, but thanks to the unity of the family and common intentions they were overcome.” |

| Company 2 | “Treating your customers, employees, supllier, anyway, your partners as family, this enrich your business, create an unique conncetion btween your family and your business. And you pass to the next generation the tradition of relationships.” |

| Company 3 | “I think the best example for us is the tasting committee where you have three generations of people. And especially the technicians. We taste the wine, and we agree on certain things, so it shapes it. The fact that we have all the members of the families gathered at this round table, all of them are shaping the wine. And in our case shaping the wine is shaping the business.” |

| Company 4 | “I think the way that relationships and who is considered a family member that might need to be brought into the business or can be considered to be brought into the business is a very important part of it.” “So those 50 partners through time have worked for the bank for nearly 1600 years, so each partner has worked for the bank for over thirty years and that’s the collective work of the family, making sure that the bank can continue to run, operate, and thrive is the exciting part and the legacy that we’re creating.” |

| Company 5 | “Being born into a particular society or community, maintaining friendships and relationships across generations—this kind of legacy is crucial in our line of business.” “And of course, in our business, the strength of the family is crucial. This unity helps transmit values from one generation to another.” |

| Company 1 | “Ethical behavior, involvment in society, these are part of the legacy, also.” |

| Company 2 | “Our guiding principles are independence, long-term thinking, partnership, responsibility, and entrepreneurial spirit.” |

| Company 3 | “We can talk about transmission in our case if we do not talk about our vineyards you cannot talk about our vineyards without talking about nature, and you cannot talk about nature if you don’t respect it.” |

| Company 4 | “So, I think philanthropy is a big tool that we use to link those historical things that the family has done to what it means to be part of the family right now.” |

| Company 5 | “Charity and philanthropy is part of our name, which our business name.” |

| Company 5 | “To be responsible, to act a steward for the society is a way of doing byusiness, is a business and it is our family business, our legacy we have to pass it onto the next generation, hoping that they will do the same thing.” |

| Company 4 | “In the early 1700s, we were involved with setting up Westminster (and other hospitals). It seems that family businesses have a very strong link to philanthropy and being sustainable.” |

| Company 3 | “Sustainability means, I was going to say it means everything […] That is because if we do not have nature, we do not have grapes, therefore we don’t have wine, and therefore we would not have any business. What I’m trying to say here is that for me sustainability […] is what we do, it is what we must do, and it is what we always needed to do.” |

| Company 2 | “Like many family businesses, we are faced with the question of how to demonstrate a credible commitment to sustainability and social responsibility while avoiding greenwashing. To emphasize its credibility, the second company’s charitable foundation which receives a significant portion of the Group’s profit each year—focuses principally on the themes of water and nutrition.” |

| Company 1 | “We have to be an example in innovation and in ethical behavior.” |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pauceanu, A.M.; Zaharia, R.M.; Benchis, M.P. The Old, the New, and the Used One—Assessing Legacy in Family Firms. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 106. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15030106

Pauceanu AM, Zaharia RM, Benchis MP. The Old, the New, and the Used One—Assessing Legacy in Family Firms. Administrative Sciences. 2025; 15(3):106. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15030106

Chicago/Turabian StylePauceanu, Alexandrina Maria, Rodica Milena Zaharia, and Melisa Petra Benchis. 2025. "The Old, the New, and the Used One—Assessing Legacy in Family Firms" Administrative Sciences 15, no. 3: 106. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15030106

APA StylePauceanu, A. M., Zaharia, R. M., & Benchis, M. P. (2025). The Old, the New, and the Used One—Assessing Legacy in Family Firms. Administrative Sciences, 15(3), 106. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15030106