Reimagining Public Service Delivery: Digitalising Initiatives for Accountability and Efficiency

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. South Africa’s Digital Transformation Context and Challenges

1.2. Theoretical Framework

2. Methodology

2.1. Design

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Selection Criteria

2.4. Study Selection Process

2.5. Data Extraction and Synthesis

2.6. Thematic Analysis and Coding Process

2.7. Quality Assessment and Limitations

3. Results

3.1. Description of Studies

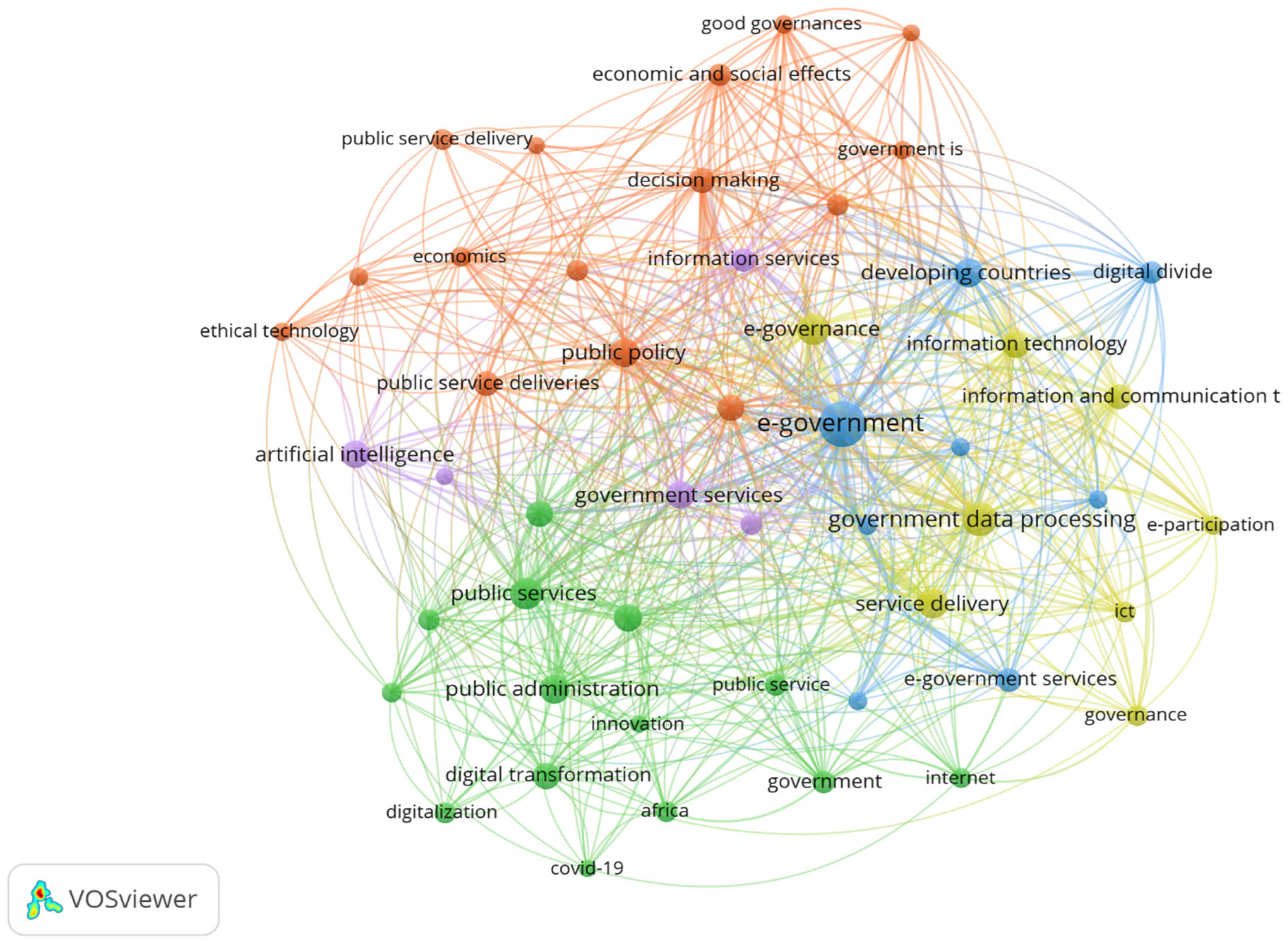

3.2. Keyword Co-Occurrence and Themes with VOSviewer

3.3. Current State of Digital Governance in South Africa

3.4. Leadership and Governance Issues

3.5. Institutional and Administrative Challenges

3.6. Public Management Reforms

3.7. Citizen Engagement and Public Trust

3.8. Ethical Frameworks and Values

3.9. Digital Transformation Initiatives

4. Discussion

5. Recommendations and Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Conclusions

5.3. Future Research Directions

5.4. Emerging Thought

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| S/N | References (APA) | Study Design/Theories Used | Emerging Themes | Findings/Discussion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | (Dlamini et al., 2022) Dlamini, D., Worku, Z., & Muchie, M. (2022). Improving service delivery in the South African public sector. International Journal of Applied Science and Research, 5(6), 153–161. | Framework: Bao et al. (2013) & Pretorius and Schurink (2007) leadership model. Method: Qualitative, theoretical model development. | Leadership, Values, and Institutional Processes | The study proposes an integrated model combining leadership, core values, and institutional processes to improve service delivery. The findings suggest that contextual adaptation of this model can enhance public sector performance. The discussion emphasises its utility as a management tool but highlights challenges in implementation due to bureaucratic resistance. |

| 2 | (Ndebele & Lavhelani, 2017) Ndebele, C., & Lavhelani, P. N. (2017). Local government and quality service delivery: An evaluation of municipal service delivery in a local municipality in Limpopo Province. Journal of Public Administration, 52(2), 340–358. | Method: Qualitative questionnaires (open-ended). Sample: 25 participants (municipal staff and community). | Financial Constraints, Revenue Generation | Financial dependency on national grants severely limits service delivery. The study finds that municipalities lack sustainable revenue streams, leading to service backlogs. The discussion advocates local revenue generation strategies, such as public–private partnerships, to reduce reliance on central funding and improve fiscal autonomy. |

| 3 | (Ngoepe, 2014) Ngoepe, M. (2014). Records management models in the public sector in South Africa: Is there a flicker of light at the end of the dark tunnel? Information Development, 32(3), 1–12. | Method: Quantitative questionnaires to record practitioners. | Records Management, Institutional Efficiency | Poor record management systems contribute to inefficiencies in public service delivery. The findings reveal a lack of standardised models, leading to disorganisation. The discussion proposes a customisable record management framework to enhance transparency and accountability, arguing that proper documentation is critical for governance and service delivery audits. |

| 4 | (Qobo & Nyathi, 2016) Qobo, M., & Nyathi, N. (2016). Ubuntu, public policy ethics and tensions in South Africa’s foreign policy. South African Journal of International Affairs, 23(4), 421–436. | Method: Qualitative policy analysis. | Ubuntu Ethics, Policy–Practice Dissonance | While Ubuntu is rhetorically championed, its application in policy is inconsistent. The findings highlight a gap between ethical ideals and practical implementation. The discussion calls for institutionalising Ubuntu in governance frameworks to align policy actions with communal values, fostering trust and equity in service delivery. |

| 5 | (Reddy, 2016) Reddy, P. S. (2016). The politics of service delivery in South Africa: The local government sphere in context. Journal of Transdisciplinary Research in Southern Africa, 12(1), 1–10. | Method: Qualitative literature review. | Politicisation, Bureaucratic Inefficiency | The politicisation of local government undermines administrative efficiency. The findings indicate that political interference disrupts service delivery planning. The discussion advocates depoliticising municipal administrations to ensure merit-based decision-making, emphasising the need for a clear separation between political and administrative roles. |

| 6 | (Smoke, 2015) Smoke, P. (2015). Rethinking decentralisation: Assessing challenges to a popular public sector reform. Public Administration and Development, 35(4), 263–278. | Method: Theoretical review. | Decentralisation Challenges, Governance Gaps | Decentralisation often fails due to poor design and a lack of local capacity. The findings show that without adequate resources, decentralised governance leads to inefficiencies. The discussion recommends context-specific decentralisation models, stressing the need for capacity-building and fiscal support to empower local governments. |

| 7 | (Moyo, 2015) Moyo, S. (2015). Creating a framework for sustainable service delivery: An analysis of North West Province, South Africa municipalities. North-West University (PhD Thesis). | Method: Mixed methods (quantitative and qualitative). Sample: 340 participants. | Resource Scarcity, Skills Shortages | Municipalities face severe resource and skills shortages, hindering service delivery. The findings reveal systemic governance failures and financial mismanagement. The discussion proposes capacity-building programs and economic development initiatives to create sustainable service delivery frameworks, emphasising the need for skilled leadership. |

| 8 | (Munzhedzi, 2016) Munzhedzi, P. H. (2016). South African public sector procurement and corruption: Inseparable twins? Journal of Transport and Supply Chain Management, 10(1), 1–8. | Method: Qualitative policy analysis. | Corruption, Procurement Malpractices | Corruption in public procurement diverts resources from service delivery. The findings link the weak enforcement of PFMA/MFMA to fraudulent practices. The discussion calls for stricter oversight, transparent tender processes, and harsh offender penalties to restore public trust and ensure equitable resource allocation. |

| 9 | (Masiya et al., 2019) Masiya, T., Davids, Y. D., & Mangai, M. S. (2019). Assessing service delivery: Public perception of municipal service delivery in South Africa. Theoretical and Empirical Researches in Urban Management, 14(2), 20–40. | Method: Quantitative survey (Social Attitude Survey). | Citizen Dissatisfaction, Inequality | Public dissatisfaction stems from unfulfilled promises and unequal service access. The findings correlate protests with perceived deprivation. The discussion urges municipalities to prioritise equitable distribution and community engagement to address historical disparities and improve service delivery outcomes. |

| 10 | (Maloba, 2015) Maloba, D. M. (2015). Monitoring good governance in South African local government and its implications for institutional development and service delivery. University of the Western Cape (PhD Thesis). | Method: Case study (City of Cape Town). | Accountability, Institutional Weaknesses | Weak accountability mechanisms compromise governance. The findings highlight poor oversight and financial mismanagement. The discussion recommends strengthening audit systems and stakeholder engagement to enhance transparency and service delivery efficiency. |

| 11 | (Hofisi & Pooe, 2017) Hofisi, C., & Pooe, T. (2017). New Public Management Issues in South Africa. In New Public Management in Africa (pp. 23–45). Routledge. | Method: A literature review. | NPM Reforms, Implementation Gaps | NPM reforms improved financial management but face adoption challenges. The findings reveal disparities in implementation across sectors. The discussion suggests tailoring NPM to South Africa’s context, emphasising performance-based accountability and skills development. |

| 12 | (Maramura, 2016) Maramura, T. C. (2016). Towards the implementation of Public–Private Partnerships (PPPS) for efficient service delivery in public institutions in South Africa. Journal of Human Ecology, 54(2), 119–123. | Method: Qualitative, secondary data analysis. | PPPs, Service Delivery Innovation | PPPs can mitigate service delivery gaps, but this requires robust regulation. The findings show that successful PPPs enhance infrastructure development. The discussion advocates clear legal frameworks to govern partnerships and ensure mutual accountability. |

| 13 | (Ajam & Fourie, 2016) Ajam, T., & Fourie, D. J. (2016). Public financial management reform in South African provincial basic education departments. Public Administration & Development, 36(4), 263–282. | Method: Quantitative PFM index analysis. | PFM Reforms, Leadership Stability | PFMA improved financial governance, but provincial disparities persist. The findings link progress to stable leadership and skilled personnel. The discussion underscores the need for continuous training and audit compliance to sustain reforms. |

| 14 | (Díaz Fuentes et al., 2014) Díaz Fuentes, D., Clifton, J., & Alonso, J. M. (2014). Did New Public Management Matter? An empirical analysis of the effects of outsourcing and decentralisation on public sector size. Public Management Review, 17(5), 643–660. | Method: Quantitative, cross-country analysis. | NPM Effectiveness, Decentralisation Impact | Decentralisation reduced the public sector’s size, but outsourcing did not. The findings question NPM’s universal applicability. The discussion highlights the need for context-specific reforms aligned with local governance structures. |

| 15 | (Nkoana et al., 2024) Nkoana, I., Selelo, M. E., & Mashamaite, K. A. (2024). Public administration and public service delivery in South Africa: A sacrifice of effective service delivery to political interests. African Journal of Public Administration and Environmental Studies, 3(1). | Method: Systematic literature review. | Political Interference, Cadre Deployment | Political appointments undermine service delivery. The findings reveal corruption and inefficiency due to patronage. The discussion calls for anti-corruption measures, merit-based hiring, and enhanced transparency to restore governance integrity. |

| 16 | (Masuku & Jili, 2022) Masuku, M. M., & Jili, N. N. (2022). Public service delivery in South Africa: The political influence at the local government level. Academic Paper. | Method: Qualitative case study. | Meritocracy vs. Patronage | The politicisation of administration breeds inefficiency. The findings show that favouritism hampers equitable service delivery. The discussion advocates depoliticising municipal appointments and adopting performance-based evaluations to improve governance. |

| 17 | (Mkhize et al., 2024) Mkhize, N. E., Kayembe, C., & Thusi, X. (2024). South Africa’s service delivery in the 4IR era: The need for responsible leadership. Africa’s Public Service Delivery & Performance Review, 12(1), a767. https://doi.org/10.4102/apsdpr.v12i1.767 | Method: Qualitative literature review. Theoretical Lens: Responsible leadership. | 4IR Technologies, Ethical Leadership, Public Sector Ethics | The findings indicate that poor leadership exacerbates service delivery failures. The discussion advocates ethical frameworks to guide 4IR integration, ensuring that technology benefits are equitably distributed. |

| 18 | (Mbandlwa, 2023) Mbandlwa, Z. (2023). Professionalisation of public service delivery in the Southern African region. Sustainable Development Goals Journal, 11(10). https://doi.org/10.55908/sdgs.v11i10.1797 | Method: Secondary data analysis. | Professionalisation, Anti-Corruption, Citizen-Centric Services | The study reveals that political interference undermines professionalism. Recommendations include training programs and accountability mechanisms to restore public trust. |

| 19 | (Ruwanika & Maramura, 2024) Ruwanika, J. M., & Maramura, T. C. (2024). Role of service providers in ensuring effective service delivery in Mangaung Metropolitan Municipality. Cogent Business & Management, 11(1), 2315695. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2024.2315695 | Method: Qualitative case study (semi-structured interviews). | Supply Chain Management, Corruption Mitigation, Capacity-Building | The findings show that corruption in procurement hampers efficiency. The discussion recommends stricter oversight and training for SCM personnel to enhance accountability. |

| 20 | (Thusi & Selepe, 2023) Thusi, X., & Selepe, M. M. (2023). The impact of poor governance on public service delivery: A case study of the South African local government. International Journal of Social Science Research and Review, 6(4), 688–697. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/370402760_The_Impact_of_Poor_Governance_on_Public_Service_Delivery_A_Case_Study_of_the_South_African_Local_Government | Method: Case study, qualitative. | Accountability Deficiencies, Financial Mismanagement, Community Protests | Poor financial management (only 41/257 clean audits) fuels public discontent. The study calls for enhanced oversight and participatory governance. |

| 21 | (Akinboade et al., 2014) Akinboade, O. A., Mokwena, M. P., & Kinfack, E. C. (2014). Protesting for improved public service delivery in South Africa’s Sedibeng District. Social Indicators Research, 119(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-013-0377-9 | Method: Quantitative (Social Attitude Survey). | Citizen Dissatisfaction, Inequality, Post-Apartheid Legacies | High dissatisfaction stems from uneven access to services. The discussion urges equitable resource allocation and community engagement. |

| 22 | (Masuku et al., 2022) Masuku, M. M., Mlambo, V. H., & Ndlovu, C. (2022). Service delivery, governance and citizen satisfaction: Reflections from South Africa. Journal of Governance and Development, 11(1), 1–20. DOI:10.14666/2194-7759-11-1-6 | Method: Secondary data (StatsSA reports). Theory: New Public Service. | Trust Deficits, Inequitable Development, Informal Settlements | Despite policy efforts, citizen trust remains low. Recommendations include holistic development plans to bridge service gaps. |

| 23 | (Gegana & Phahlane, 2024) Gegana, S., & Phahlane, M. (2024). Techniques for effective government service delivery. South African Journal of Information Management, 26(1), a1782. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajim.v26i1.1782 | Method: Qualitative case study (interviews). Theory: Institutional theory. | E-Participation, Open Government, ICT Policy Gaps | The lack of ICT policies hinders e-governance. The study recommends apps for real-time feedback to improve transparency. |

| 24 | (Shibambu & Ngoepe, 2024) Shibambu, A., & Ngoepe, M. (2024). Enhancing service delivery through digital transformation in the public sector in South Africa. Global Knowledge, Memory and Communication, 74(11). | Method: Qualitative (interviews with CIOs). | Digital Transformation, Legislative Gaps, Strategic Implementation—Identifies inconsistent digital adoption due to weak legislation and strategy. | The findings reveal ad hoc digital initiatives. Practical implications include standardised frameworks for nationwide rollout. |

| 25 | (Nkgapele, 2024) Nkgapele, S. M. (2024). The usability of e-government as a mechanism to enhance public service delivery in the South African government. International Journal of Social Science Research, 3(1). | Method: Qualitative (secondary data). | Digital Divide, ICT Skills Shortages, Resistance to Change—Examines barriers to e-government (e.g., literacy, infrastructure) and suggests corrective measures. | Progress is evident, but rural areas lag behind. The study calls for infrastructure investment and digital literacy programs. |

| 26 | (Galushi & Malatji, 2022) Galushi, L. T., & Malatji, T. L. (2022). Digital public administration and inclusive governance at the South African local government. African Journal of Information Systems, 11(6). https://doi.org/10.36941/ajis-2022-0154 | Method: Empirical study. | 4IR Adaptation, Rural Exclusion, Ethical E-Governance—Highlights risks of excluding poor communities from digital services during COVID-19. | E-governance benefits are urban-centric. Recommendations include subsidised rural ICT access. |

| 27 | (Kariuki et al., 2019) Kariuki, P., Ofusori, L. O., & Goyayi, M. (2019). E-government and citizen experiences in South Africa: Ethekwini Metropolitan case study. Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Theory and Practice of Electronic Governance, 1–8. DOI:10.1145/3326365.3326432 | Method: Mixed methods (interviews + surveys). | Political Will, Internet Accessibility, Socioeconomic Barriers—Attributes low e-government priority to lack of leadership and infrastructure. | Citizens face access challenges. The study urges metro-wide digital inclusion strategies. |

| 28 | (Malomane, 2021) Malomane, A. P. (2021). The role of e-governance as an alternative service delivery mechanism in local government [Master’s thesis]. University of Johannesburg. https://hdl.handle.net/10210/501114 | Method: Qualitative (conceptual analysis). | 24/7 Service Availability, Digital Literacy, Infrastructure Gaps—Proposes ICT-enabled ASD to overcome service delivery bottlenecks. | E-governance success hinges on accessibility and literacy. Libraries/schools should serve as ICT hubs. |

| 29 | (Mohale, 2024) Mohale, C. (2024). The role of e-government in promoting municipal service delivery in South Africa. International Journal of Social Science Research and Review, 7(3). https://doi.org/10.47814/ijssrr.v7i3.1992 | Method: Qualitative (secondary data). | Rural ICT Deficits, Multilingual Content, 4IR Readiness—Advocates localised digital solutions to bridge urban–rural divides. | Poor communities lack ICT access. The study recommends multilingual platforms and infrastructure grants. |

| 30 | (Mohlala, 2023) Mohlala, L. T. (2023). The factors hindering the successful implementation of e-government within the City of Johannesburg [Master’s thesis]. University of Johannesburg. https://hdl.handle.net/10210/505233 | Method: Qualitative (case study). | Digital Illiteracy, Corruption, and Institutional Weaknesses—Identifies political and socioeconomic barriers to e-governance in metros. | Corruption and illiteracy impede implementation. Solutions include anti-fraud systems and adult education programs. |

| 31 | (Koma & Tshiyoyo, 2015) Koma, S. B., & Tshiyoyo, M. M. (2015). Improving public service delivery in South Africa: A case of administrative reform. University of Pretoria Institutional Repository. http://hdl.handle.net/2263/52466 | Method: Document review, literature review. | Administrative Reform, Presidential Initiatives, Institutional Blockages | Findings reveal structural inefficiencies in policy implementation. The discussion calls for depoliticised reforms to enhance accountability and service quality. |

| 32 | (Nkoana et al., 2024) Nkoana, I., Selelo, M. E., & Mashamaite, K. A. (2024). Public administration and public service delivery in South Africa: A sacrifice of effective service delivery to political interests. African Journal of Public Administration and Environmental Studies, 3(1). https://hdl.handle.net/10520/ejc-aa_ajopaes_v3_n1_a4 | Method: Systematic literature review. | Political Interference, Cadre Deployment, Governance Failures | Political appointments lead to inefficiency and corruption. Recommendations include anti-corruption measures and merit-based hiring to restore public trust. |

| 33 | (Mlambo, 2019) Mlambo, D. N. (2019). Governance and service delivery in the public sector: The case of South Africa under Jacob Zuma (2009–2018). African Renaissance, 16(3). https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC-1834727f56 | Method: Qualitative, historical analysis. | Corruption, ANC Governance, Elite Capture | Elite enrichment exacerbates poverty. The study urges institutional reforms to break patronage networks. |

| 34 | (Sebake & Sebola, 2014) Sebake, B. K., & Sebola, M. P. (2014). Growing trends and tendencies of corruption in the South African public service: Negative contribution to service delivery. Journal of Public Administration, 49(3). https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC164774 | Method: Qualitative policy analysis. | Supply Chain Corruption, Nepotism, Accountability Deficits | Corruption in procurement worsens service backlogs. Recommendations include transparent bidding and stricter enforcement of PFMA/MFMA. |

| 35 | (Manyaka & Sebola, 2012) Manyaka, R. K., & Sebola, M. P. (2012). Impact of performance management on service delivery in the South African public service. Journal of Public Administration, 47(si-1). https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC121939 | Method: Policy review. | Performance Management, Employee Productivity, Legislative Frameworks | Poor performance management persists despite legislative frameworks. The study calls for continuous skills development and monitoring. |

| 36 | (Maramura et al., 2019) Maramura, T. C., Nzewi, O. I., & Tirivangasi, H. M. (2019). Mandelafying the public service in South Africa: Towards a new theory. Journal of Public Affairs, 19(4), e1982. https://doi.org/10.1002/pa.1982 | Method: Theoretical analysis. | Ethical Leadership, Ubuntu, Public Trust | Service delivery protests reflect eroded trust—the discussion advocates values-driven governance reforms. |

| 37 | (Biljohn & Lues, 2020) Biljohn, M. I. M., & Lues, L. (2020). Citizen participation, social innovation, and local government service delivery governance: Findings from South Africa. International Journal of Public Administration, 43(3), 229–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/01900692.2019.1628052 | Method: A case study. | Social Innovation, Participatory Governance, Open Systems—Explores how citizen engagement can co-create solutions for service delivery. | Top–down approaches fail. The study highlights the need for inclusive, community-driven innovation. |

| 38 | (Sindane & Nambalirwa, 2012) Sindane, A. M., & Nambalirwa, S. (2012). Governance and public leadership: The missing links in service delivery in South Africa. Journal of Public Administration, 47(3). https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC129628 | Method: Qualitative literature review. | Leadership Vacuum, Protest Governance, Multistakeholder Solutions—These attributes are attributed to weak leadership and fragmented governance. | Protests demand holistic solutions. Recommendations include collaborative forums for community–government dialogue. |

| 39 | (Akinboade et al., 2014) Akinboade, O. A., Mokwena, M. P., & Kinfack, E. C. (2014). Protesting for improved public service delivery in South Africa’s Sedibeng District. Social Indicators Research, 119(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-014-0781-9 | Method: Mixed methods (survey + interviews). | Service Satisfaction, Age/Regional Disparities, Municipal Governance—Links low satisfaction to governance gaps and unmet promises. | Youth and rural areas are the most dissatisfied. The study urges tailored service delivery and accountability mechanisms. |

| 40 | (Muthien, 2014) Muthien, Y. (2014). Public service reform: Key challenges of execution. Strategic Review for Southern Africa, 36(2), 137–140. | Method: Policy analysis. | Skills Deficit, Semi-Privatisation, Integrated Models—Critiques NPM’s uneven success and calls for coherent administrative models. | Fragmented reforms hinder delivery. The study proposes a re-engineered public service with standardised skills audits. |

| 41 | (Madumo, 2016) Madumo, O. S. (2016). De-politicisation of service delivery in local government: Prospects for development in South Africa. African Journal of Public Affairs, 9(3). http://hdl.handle.net/2263/58220 | Method: Conceptual analysis. | Depoliticisation, Professionalisation, Administrative Autonomy—Advocates separating politics from administration to improve services. | Political interference breeds inefficiency. Recommendations include merit-based appointments and clear role demarcation. |

| 42 | (Koelble & LiPuma, 2010) Koelble, T. A., & LiPuma, E. (2010). Institutional obstacles to service delivery in South Africa. Social Dynamics, 36(3), 565–589. https://doi.org/10.1080/02533952.2010.518002 | Method: Institutional analysis. | Skills Shortages, Policy Incoherence, Rural–Urban Divides | Rural municipalities struggle with implementation. The study calls for targeted skills development and enforcement of financial controls. |

| 43 | (Van Eeden & Khaba, 2016) Van Eeden, E. S., & Khaba, B. (2016). Politicising service delivery in South Africa: A reflection on the history, reality and fiction of Bekkersdal, 1949–2015. Journal for Contemporary History, 41(2). https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC-4fb2b2dba | Method: Historical analysis, interviews. | Historical Legacies, Mining Communities, Protest Narratives | Protests reflect unresolved historical grievances. The discussion emphasises inclusive development planning. |

| 44 | (Gumede & Dipholo, 2014) Gumede, N., & Dipholo, K. B. (2014). Governance, restructuring and the New Public Management reform: South African perspectives. Journal of Educational and Social Research, 4(6), 43–52. https://doi.org/10.5901/jesr.2014.v4n6p43 | Method: Theoretical review. | NPM Hybridization, Colonial Legacies, Fiscal Reforms | NPM faces unique hurdles in SA. The study recommends context-sensitive reforms. |

| 45 | (Molobela & Uwizeyimana, 2023) Molobela, T. T., & Uwizeyimana, D. E. (2023). New public management and post-new public management paradigms: Deconstruction and reconfiguration of the South African public administration. International Journal of Research in Business and Social Science, 12(8), 327–334. https://doi.org/10.20525/ijrbs.v12i8.2941 | Method: Qualitative, secondary data. | Post-NPM, Paradigm Shifts, Hybrid Governance | SA’s public administration needs adaptive models. The study suggests integrating NPM with developmental state principles. |

| 46 | (Munzhedzi, 2020) Munzhedzi, P. H. (2020). An evaluation of the application of the new public management principles in the South African municipalities. Journal of Public Affairs, 20(3), e2132. https://doi.org/10.1002/pa.2132 | Method: A literature review. | NPM Implementation, Decentralisation Challenges, Municipal Capacity | NPM principles are poorly applied. Recommendations include capacity-building and anti-corruption measures. |

| 47 | (Mamokhere, 2022) Mamokhere, J. (2022). Understanding the Complex Interplay of Governance, Systematic, and Structural Factors Affecting Service Delivery in South African Municipalities. Commonwealth Youth and Development, 20(2). https://hdl.handle.net/10520/ejc-cydev-v20-n2-a2 | Qualitative research using document analysis: New Public Management and Public Choice Theories | Governance Failures, Structural Constraints, Systemic Inequalities | The study reveals how corruption, political interference, and apartheid legacies combine to undermine service delivery. It recommends strengthening governance, citizen participation, and intergovernmental collaboration to address multifaceted challenges. |

| 48 | (Zerihun & Mashigo, 2022) Zerihun, M.F. & Mashigo, M.P. (2022). The quest for service delivery: The case of a rural district municipality in Mpumalanga. Africa’s Public Service Delivery and Performance Review, 10(1). https://hdl.handle.net/10520/ejc-apsdpr_v10_i1_a512 | Mixed methods (survey of 120 respondents); Social Contract Theory | Rural Service Gaps, Payment Willingness, IDP Implementation | The study finds that residents are dissatisfied but willing to pay for improved services. It highlights the disconnect between municipal plans and implementation, recommending better IDP alignment with community needs. |

| 49 | (Maramura & Thakhathi, 2016) Maramura, T. C. & Thakhathi, D. R. (2016). Analysing e-governance policies in South Africa. Journal of Communication, 7(2), 241–245. | Descriptive policy analysis | E-Governance frameworks, Legislative Alignment, Digital Transformation | The study shows that post-1994 policies support e-governance, but implementation lags. It concludes that successful digital governance requires stronger legislative enforcement and institutional coordination. |

| 50 | (Sing, 2012) Sing, D. (2012). Building a unified public administration system in South Africa. Public Personnel Management, 41(3). https://doi.org/10.1177/009102601204100309 | Policy analysis | Integrated Governance, Developmental State, Cross-sector Collaboration | The study argues for a coordinated three-tier government approach to service delivery. It highlights the 2008 Public Administration Management Bill as the key framework needing implementation support. |

| 51 | (Swart, 2013) Swart, I. (2013). South Africa’s service-delivery crisis: From contextual understanding to diaconal response. HTS Theological Studies, 69(2). https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC138610 | Theological-practical analysis | Crisis Framing, Faith-Based Responses, Social Justice | The study compares the service delivery crisis to apartheid-era struggles. It proposes that faith-based organisations play a greater role in addressing systemic inequalities through community empowerment. |

| 52 | (Okafor, 2018) Okafor, C. (2018). Dysfunctional public administration in the era of rising expectations. Journal of Nation-building & Policy Studies, 2(1). https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC-134be1c8a7 | Content/descriptive analysis | Administrative Dysfunction, Reform Fatigue, Nation-Building | The study links service failures to weak institutions and unfulfilled reforms. It recommends depoliticised administration and merit-based appointments to restore public trust. |

| 53 | (F. Cloete, 2012) Cloete, F. (2012). e-Government lessons from South Africa 2001–2011. African Journal of Information and Communication, 12. https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC134065 | Institutional assessment using Rorissa model | Digital Governance lag, Policy Stagnation, Measurement Frameworks | The study analyses why SA fell behind peers in e-government adoption. It identifies weak institutional arrangements and recommends improved e-barometer metrics for tracking progress. |

| 54 | (Twum-Darko et al., 2023) Twum-Darko, M., Ncede, N., & Tengeh, R. (2023). Stakeholder engagement in public sector strategy. International Journal of Research in Business & Social Science, 12(3), 109. https://doi.org/10.20525/ijrbs.v12i3.2361 | Mixed-methods case study (WCED); Actor Network Theory | Participatory Governance, Network Alignment, Continuous Engagement | Structured stakeholder engagement improves service delivery. The study proposes ongoing community–government dialogue forums to align expectations and implementation. |

| 55 | (Franks, 2015) Franks, P. E. (2015). Training senior public servants in South Africa. Journal of Public Administration, 50(2). https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC183284 | Policy review | Skills Deficit, Cadre Deployment, NDP Alignment | The study highlights the tension between political appointments and technical competence. It recommends NDP-guided training programs to professionalise bureaucracy amid political pressures. |

| 56 | (Mbandlwa et al., 2020) Mbandlwa, Z., Dorasamy, N., & Fagbadebo, O. (2020). Ethical leadership and service delivery challenges. Test Engineering & Management, 83, 24986–24998. | Theoretical discourse | Leadership Ethics, Corruption Linkage, Accountability | The study establishes a direct correlation between unethical leadership and poor service delivery. It calls for ethics training and stronger accountability mechanisms in public sector. |

| 57 | (Naidoo, 2012) Naidoo, G. (2012). Need for ethical leadership to curb corruption. Journal of Public Administration, 47(3). https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC129630 | Literature review | Ethical Governance, Anti-Corruption Measures, Leadership Modelling | The study identifies procurement fraud as a major challenge. It advocates leaders to model ethical behaviour and strengthen oversight systems to restore public trust. |

| 58 | (Balkaran, 2018) Balkaran, S. (2018). Fourth Industrial Revolution Impact on the Public Sector. Walter Sisulu University. | Socio-evolution theory | Technological Disruption, Skills Transition, Digital Inequality | The study warns of 4IR exacerbating inequalities without proactive human capital investments. It recommends balanced technology adoption with social protection policies. |

| 59 | (Zondi & Reddy, 2016) Zondi & Reddy (2016). Constitutional mandate for participation. Administratio Publica, 24(3). https://journals.co.za/doi/10.10520/ejc-adminpub-v24-n3-a3 | Mixed methods (iLembe District) | Participatory Governance, IDP Effectiveness, Protest Reduction | The study shows that proper public participation decreases service protests. It proposes a model for meaningful community engagement in municipal planning processes. |

| 60 | (Twala, 2014) Twala, C. (2014). Causes/impact of Service Delivery Protests. Cumhuriyet Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi, 39(2), 159. | Political analysis | Protest Politics, Basic Needs Backlogs, Accountability Deficits | The study links protests to the unfulfilled post-apartheid social contract. It argues that national–local government coordination is required to address structural inequalities. |

| 61 | (Matloga et al., 2024) Matloga, S. T., Mahole, E., & Nekhavhambe, M. M. (2024). Public participation challenges in Vhembe District. Journal of Local Government Research, 5(1). https://hdl.handle.net/10520/ejc-jolgri_v5_n1_a160 | Mixed methods (15 participants) | Participation Fatigue, Trust Deficits, Capacity Gaps | The study finds communities disengaged due to broken promises. It recommends skills development for officials and traditional leaders to rebuild engagement. |

| 62 | (Rulashe & Ijeoma, 2022) Rulashe & Ijeoma (2022). Accountability in Buffalo City Metro. Africa’s Public Service Delivery, 10(1). https://hdl.handle.net/10520/ejc-apsdpr_v10_i1_a535 | Mixed methods (47 participants) | Accountability Mechanisms, Communication Gaps, Implementation Failures | The study reveals a disconnect between policy and practice in accountability systems. It suggests strengthening Public Participation Units and community oversight structures. |

| 63 | (Nzimakwe, 2023) Nzimakwe, T. I. (2023). SOE procurement and service delivery. African Journal of Public Affairs, 14(1). https://hdl.handle.net/10520/ejc-ajpa_v14_n1_a2 | Literature review | State Capture, Procurement Maladministration, Governance Failures | The study exposes how corruption in SOEs undermines economic development. It calls for transparent procurement systems insulated from political interference. |

| 64 | (Kumalo & Scheepers, 2021) Kumalo & Scheepers (2021). Leadership in public sector turnarounds. Journal of Organisational Change Management, 34(1). | Qualitative (11 executive interviews) | Crisis Leadership, Turnaround Phases, Authentic Leadership | The study identifies four critical turnaround phases requiring different leadership approaches. It emphasises the need for strong individual leadership during the initial crisis stages. |

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| Peer-reviewed journal articles, conference proceedings, and book chapters | Non-peer-reviewed literature, opinion pieces, and editorials |

| Studies focusing on digitalisation in public service delivery | Studies focusing solely on technology without a public service application |

| Empirical research (quantitative, qualitative, or mixed methods) | Purely theoretical papers without empirical evidence |

| Studies examining cases from South Africa | Studies not specifying geographical context |

| Publications in English | Publications in languages other than English |

| Studies published between January 2010 and March 2025 | Studies published before 2010 |

| Research examining institutional, technological, or social dimensions of digital service delivery | Research focusing exclusively on technical specifications |

| Studies addressing accountability, efficiency, or inclusivity aspects | Studies without clear governance implications |

References

- Ajam, T., & Fourie, D. J. (2016). Public financial management reform in South African provincial basic education departments. Public Administration & Development, 36(4), 263–282. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Akinboade, O. A., Mokwena, M. P., & Kinfack, E. C. (2014). Protesting for improved public service delivery in South Africa’s Sedibeng district. Social Indicators Research, 119(1), 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailur, S. (2007). Stakeholders and e-government: Involving citizens in the implementation of e-government initiatives (Working Paper No. 109). Indian Institute of Management Bangalore (IIMB). [Google Scholar]

- Balkaran, S. (2018). Fourth industrial revolution impact on the public sector. Walter Sisulu University. [Google Scholar]

- Bao, G., Wang, X., Larsen, G. L., & Morgan, D. F. (2013). Beyond new public governance: A value-based global framework for performance management, governance, and leadership. Administration & Society, 45(4), 443–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biljohn, M. I. M., & Lues, L. (2020). Citizen participation, social innovation, and the governance of local government service delivery: Findings from South Africa. International Journal of Public Administration, 43(3), 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chipkin, I., & Lipietz, B. (2012). Transforming South Africa’s racial bureaucracy: New public management and public sector reform in contemporary South Africa (PARI Long Essays No. 1). Public Affairs Research Institute. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Transforming-South-Africa%27s-racial-bureaucracy%3A-New-Chipkin-Lipietz/92fe8874193b222f4df047b427bfd3f7672994f3 (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Cloete, F. (2012). E-government lessons from South Africa 2001–2011. African Journal of Information and Communication, 12, 128–142. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC134065 (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Cloete, H. C. A. (2023). Towards evidence-based human resource development for South African local government. Africa’s Public Service Delivery & Performance Review, 11(1), a689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz Fuentes, D., Clifton, J., & Alonso, J. M. (2014). Did new public management matter? An empirical analysis of the effects of outsourcing and decentralisation on public sector size. Public Management Review, 17(5), 643–660. [Google Scholar]

- Dlamini, D., Worku, Z., & Muchie, M. (2022). Improving service delivery in the South African public sector. International Journal of Applied Science and Research, 5(6), 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunleavy, P., & Hood, C. (1994). From old public administration to new public management. Public Money & Management, 14(3), 9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Dunleavy, P., Margetts, H., Bastow, S., & Tinkler, J. (2006). New public management is dead—Long live digital-era governance. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 16(3), 467–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franks, P. E. (2015). Training senior public servants in South Africa. Journal of Public Administration, 50(2), 234–248. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC183284 (accessed on 17 May 2025).

- Galushi, L. T., & Malatji, T. L. (2022). Digital public administration and inclusive governance at the South African local government, in depth analysis of e-government and service delivery in Musina local municipality. Academic Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies, 11(6), 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gegana, S., & Phahlane, M. (2024). Techniques for effective government service delivery. South African Journal of Information Management, 26(1), a1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gherghin, C. A. (2025). Public policies for digitalising public services in the European Union: From foundations to contemporary challenges. The Technium Social Sciences Journal, 67, 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumede, N., & Dipholo, K. B. (2014). Governance, restructuring and the New Public Management reform: South African perspectives. Journal of Educational and Social Research, 4(6), 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heeks, R. (2001). Reinventing government in the information age: International practice in it-enabled public sector reform. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hofisi, C., & Pooe, T. (2017). New public management issues in South Africa. In New public management in Africa (pp. 23–45). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, Q. N., Fàbregues, S., Bartlett, G., Boardman, F., Cargo, M., Dagenais, P., Gagnon, M.-P., Griffiths, F., Nicolau, B., O’Cathain, A., Rousseau, M.-C., Vedel, I., & Pluye, P. (2018). The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Education for Information, 34(4), 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hood, C. (1991). A public management for all seasons? Public Administration, 69(1), 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, T., Baron, A., & Vieyra, J. C. (2018). Digital technologies for transparency in public investment: New tools to empower citizens and governments (IDB Discussion Paper No. 634) (pp. 1–47). Inter-American Development Bank. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kariuki, P., Ofusori, L. O., & Goyayi, M. (2019, April 3–5). E-government and citizen experiences in South Africa: Ethekwini metropolitan case study. 12th International Conference on Theory and Practice of Electronic Governance (pp. 1–8), Melbourne, Australia. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitchenham, B., & Charters, S. (2007). Guidelines for performing systematic literature reviews in software engineering (EBSE Technical Report EBSE-2007-01, Version 2.3, July 9 2007). School of Computer Science & Mathematics, Keele University and Department of Computer Science, University of Durham. [Google Scholar]

- Koelble, T. A., & LiPuma, E. (2010). Institutional obstacles to service delivery in South Africa. Social Dynamics, 36(3), 565–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koma, S. B., & Tshiyoyo, M. M. (2015). Improving public service delivery in South Africa: A case of administrative reform. African Journal of Public Affairs, 8, 30–42. [Google Scholar]

- Kumalo, M., & Scheepers, C. B. (2021). Leadership of change in South Africa public sector turnarounds. Journal of Organisational Change Management, 34(1), 137–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madumo, O. S. (2016). De-politicisation of local government service delivery: Prospects for South Africa’s development. African Journal of Public Affairs, 9(3), 81–94. [Google Scholar]

- Maloba, D. M. (2015). Monitoring good governance in South African local government and its implications for institutional development and service delivery [Ph.D. thesis, University of the Western Cape]. [Google Scholar]

- Malomane, A. P. (2021). The role of e-governance as an alternative service delivery mechanism in local government [Master’s thesis, University of Johannesburg]. [Google Scholar]

- Mamokhere, J. (2022). Understanding the complex interplay of governance, systematic, and structural factors affecting service delivery in South African Municipalities. Commonwealth Youth and Development, 20(2), 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manda, M. I., & Dhaou, S. B. (2019, April). Responding to the challenges and opportunities in the 4th Industrial Revolution in developing countries. In Proceedings of the 12th international conference on theory and practice of electronic governance (ICEGOV 2019) (pp. 244–253). Association for Computing Machinery. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantzaris, E. A., & Pillay, P. (2019). Monitoring, evaluation and accountability against corruption: A South African case study. Journal of Reviews on Global Economics, 8(1), 521–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manyaka, R. K., & Sebola, M. P. (2012). Impact of performance management on service delivery in the South African public service. Journal of Public Administration, 47(1-1), 299–310. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC121939 (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Maramura, T. C. (2016). Towards the implementation of public-private partnerships (PPPS) for efficient service delivery in public institutions in South Africa. Journal of Human Ecology, 54(2), 119–123. [Google Scholar]

- Maramura, T. C., Nzewi, O. I., & Tirivangasi, H. M. (2019). Mandelafying the public service in South Africa: Towards a new theory. Journal of Public Affairs, 19(4), e1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maramura, T. C., & Thakhathi, D. R. (2016). Analysing E-governance policies in South Africa. Journal of Communication, 7(2), 241–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margetts, H. (2009). The internet and public policy. Policy & Internet, 1(1), 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masiya, T., Davids, Y. D., & Mangai, M. S. (2019). Assessing service delivery: Public perception of municipal service delivery in South Africa. Theoretical and Empirical Researches in Urban Management, 14(2), 20–40. [Google Scholar]

- Masuku, M. M., & Jili, N. N. (2022). Public service delivery in South Africa: The political influence at the local government level. Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Masuku, M. M., Mlambo, V. H., & Ndlovu, C. (2022). Service delivery, governance and citizen satisfaction: Reflections from South Africa. Journal of Governance and Development, 11(1), 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matloga, S. T., Mahole, E., & Nekhavhambe, M. M. (2024). Public participation challenges in Vhembe district. Journal of Local Government Research, 5(1), a160. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10520/ejc-jolgri_v5_n1_a160 (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Mbandlwa, Z. (2023). Professionalisation of public service delivery in the Southern African region. Sustainable Development Goals Journal, 11(10), e1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbandlwa, Z., Dorasamy, N., & Fagbadebo, O. (2020). Ethical leadership and the challenge of service delivery in South Africa: A discourse. TEST Engineering & Management Magazine, 83, 24986–24998. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/342992609_Ethical_Leadership_and_the_Challenge_of_Service_Delivery_in_South_Africa_A_Discourse (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Meijer, A., & Bolívar, M. P. R. (2020). The governance of smart cities. Analysis of the Smart Urban Governance Literature. Government Information Quarterly, 37(3), 101416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mergel, I. (2013). Social media in the public sector: A guide to participation, collaboration, and transparency in the networked world. Jossey-Bass. ISBN 978-1-118-10994-6. [Google Scholar]

- Mkhize, N. E., Kayembe, C., & Thusi, X. (2024). South Africa’s service delivery in the 4IR era: The need for responsible leadership. Africa’s Public Service Delivery & Performance Review, 12(1), a767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mlambo, D. N. (2019). Governance and service delivery in the public sector: The case of South Africa under Jacob Zuma (2009–2018). African Renaissance, 16(3), 203–220. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC-1834727f56 (accessed on 20 May 2025). [CrossRef]

- Mohale, C. (2024). The role of e-government in promoting municipal service delivery in South Africa. International Journal of Social Science Research and Review, 7(3), 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohlala, L. T. (2023). The factors hindering the successful implementation of E-government within the City of Johannesburg [Master’s thesis, University of Johannesburg]. [Google Scholar]

- Molobela, T. T., & Uwizeyimana, D. E. (2023). New public management and post-new public management paradigms: Deconstruction and reconfiguration of the South African public administration. International Journal of Research in Business and Social Science, 12(8), 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyo, S. (2015). Creating a framework for sustainable service delivery: An analysis of municipalities in the North West Province, South Africa [Ph.D. thesis, North-West University]. [Google Scholar]

- Munzhedzi, P. H. (2016). South African public sector procurement and corruption: Inseparable twins? Journal of Transport and Supply Chain Management, 10(1), 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munzhedzi, P. H. (2020). An evaluation of the application of the new public management principles in the South African municipalities. Journal of Public Affairs, 20(3), e2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthien, Y. (2014). Public service reform: Key challenges of execution. Strategic Review for Southern Africa, 36(2), 137–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutula, S. M., & Mostert, B. J. (2022). African Ubuntu and Sustainable Development Goals: Seeking human mutual relations and service in development. Third World Quarterly, 43(10), 2294–2314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naidoo, G. (2012). There is a need for ethical leadership to curb corruption. Journal of Public Administration, 47(3), 656–683. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC129630 (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Ndebele, C., & Lavhelani, P. N. (2017). Local government and quality service delivery: An evaluation of municipal service delivery in a local municipality in Limpopo Province. Journal of Public Administration, 52(2), 340–358. [Google Scholar]

- Ngcamu, B., & Mantzaris, E. (2021). The effects of COVID-19 on vulnerable groups: A reflection on South African informal urban settlements. Africa’s Public Service Delivery and Performance Review, 9(1), a483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngoepe, M. (2014). Records management models in the public sector in South Africa: Is there a flicker of light at the end of the dark tunnel? Information Development, 32(3), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkgapele, S. M. (2024). The usability of e-government as a mechanism to enhance public service delivery in the South African government. International Journal of Social Science Research, 3(1), 116–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkoana, I., Selelo, M. E., & Mashamaite, K. A. (2024). Public administration and public service delivery in South Africa: A sacrifice of effective service delivery to political interests. African Journal of Public Administration and Environmental Studies, 3(1), 79–103. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10520/ejc-aa_ajopaes_v3_n1_a4 (accessed on 20 June 2025). [CrossRef]

- Nyahodza, L., & Higgs, R. (2017). Towards bridging the digital divide in post-apartheid South Africa: A case of a historically disadvantaged university in Cape Town. South African Journal of Libraries and Information Science, 83(1), 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nzimakwe, T. I. (2023). SOE procurement and service delivery. African Journal of Public Affairs, 14(1), 1–18. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10520/ejc-ajpa_v14_n1_a2 (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- Okafor, C. (2018). Dysfunctional public administration in the era of rising expectations. Journal of Nation-building & Policy Studies, 2(1), 5–24. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC-134be1c8a7 (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Osborne, D., & Gaebler, T. (1992). Reinventing government: How the entrepreneurial spirit is transforming the public sector. Addison-Wesley. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollitt, C., & Bouckaert, G. (2017). Public management reform: A comparative analysis. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pretorius, D., & Schurink, W. (2007). Enhancing service delivery in local government: The case of a district municipality. SA Journal of Human Resource Management, 5(3), 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Qobo, M., & Nyathi, N. (2016). Ubuntu, public policy ethics and tensions in South Africa’s foreign policy. South African Journal of International Affairs, 23(4), 421–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, P. S. (2016). The politics of service delivery in South Africa: The local government sphere in context. Journal of Transdisciplinary Research in Southern Africa, 12(1), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Republic of South Africa. (2012). White paper on transforming public service delivery (Batho Pele). Department of Public Service and Administration. Available online: https://www.gov.za/documents/white-papers/transforming-public-service-delivery-white-paper-batho-pele-white-paper-01 (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Rulashe, T., & Ijeoma, E. O. C. (2022). Accountability in buffalo city metro. Africa’s Public Service Delivery, 10(1), 535. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10520/ejc-apsdpr_v10_i1_a535 (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Ruwanika, J. M., & Maramura, T. C. (2024). Role of service providers in ensuring effective service delivery in mangaung metropolitan municipality. Cogent Business & Management, 11(1), 2315695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebake, B. K., & Sebola, M. P. (2014). Growing trends and tendencies of corruption in the South African public service: Negative contribution to service delivery. Journal of Public Administration, 49(3), 744–755. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC164774 (accessed on 7 June 2025).

- Shibambu, A., & Ngoepe, M. (2024). Enhancing service delivery through digital transformation in the public sector in South Africa. Global Knowledge, Memory and Communication, 74(11), 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sindane, A. M., & Nambalirwa, S. (2012). Governance and public leadership: The missing links in service delivery in South Africa. Journal of Public Administration, 47(3), 695–705. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC129628 (accessed on 27 May 2025).

- Sing, D. (2012). Building a unified public administration system in South Africa. Public Personnel Management, 41(3), 549–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smoke, P. (2015). Rethinking decentralisation: Assessing challenges to a widespread public sector reform. Public Administration and Development, 35(4), 263–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- South African Revenue Service. (2023). Annual report 2022/23 (pp. 57–58). Available online: https://www.sars.gov.za/wp-content/uploads/Docs/StratAnnualPerfplans/SARS-AR-28-%E2%80%93-Annual-Report-2022-2023.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Statistics South Africa. (2023a). Annual report 2022/23—Book 1: Performance information and governance. Statistics South Africa. Available online: https://www.statssa.gov.za/?page_id=368 (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Statistics South Africa. (2023b). Annual report 2022/23—Book 2: Annual financial statements. Statistics South Africa. Available online: https://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/AnnualReport/StatisticsSouthAfricaAnnualReport20223_Book2.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Statistics South Africa. (2023c). Gender series volume X: Gender disparities in access to and use of ICT in South Africa, 2016–2022 (Report No. 03-10-27). Statistics South Africa. Available online: https://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/Report-03-10-27/Report-03-10-272022.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Swart, I. (2013). South Africa’s service-delivery crisis: From contextual understanding to diaconal response. HTS Theological Studies, 69(2), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thusi, X., & Selepe, M. M. (2023). The impact of poor governance on public service delivery: A case study of the South African local government. International Journal of Social Science Research and Review, 6(4), 688–697. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/370402760_The_Impact_of_Poor_Governance_on_Public_Service_Delivery_A_Case_Study_of_the_South_African_Local_Government (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Twala, C. (2014). Causes/impact of service delivery protests. Cumhuriyet Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi, 39(2), 159. [Google Scholar]

- Twum-Darko, M., Ncede, N., & Tengeh, R. (2023). Stakeholder engagement in public sector strategy. International Journal of Research in Business & Social Science, 12(3), 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Waldt, G. (2020). Towards project management maturity: The case of the South African government. Africa’s Public Service Delivery & Performance Review, 8(1), a407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eeden, E. S., & Khaba, B. (2016). Politicising service delivery in South Africa: A reflection on the history, reality and fiction of Bekkersdal, 1949–2015. Journal for Contemporary History, 41(2), 120–143. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC-4fb2b2dba (accessed on 25 June 2025). [CrossRef]

- Zerihun, M. F., & Mashigo, M. P. (2022). The quest for service delivery: The case of a rural district municipality in Mpumalanga. Africa’s Public Service Delivery and Performance Review, 10(1), a512. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10520/ejc-apsdpr_v10_i1_a512 (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- Zondi, S. I., & Reddy, P. S. (2016). The constitutional mandate as a participatory instrument for service delivery in South Africa. Administratio Publica, 24(3), 27–37. Available online: https://journals.co.za/doi/10.10520/ejc-adminpub-v24-n3-a3 (accessed on 11 June 2025).

| CASP Assessment Criteria | Studies Meeting Criterion (n = 64) | Percentage (%) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clear statement of aims | 60 | 93.8% | Assessed whether the study had focused research objectives |

| Appropriate methodology | 59 | 92.2% | Evaluated if the research design matched the research aims |

| Research design is clearly explained | 56 | 87.5% | Considered the clarity of the study design and justification |

| Recruitment strategy appropriate | 53 | 82.8% | Looked at whether the sample was suitable for the research |

| Data collection is rigorously described | 57 | 89.1% | Considered the appropriateness and detail of data collection methods |

| Reflexivity of researchers is considered | 48 | 75.0% | Assessed if researchers discussed their potential bias and positioning |

| Ethical issues addressed | 58 | 90.6% | Checked for ethical approval and informed consent procedures |

| Data analysis is sufficiently rigorous | 55 | 85.9% | Examined the depth and transparency of analysis |

| Findings are presented and supported by evidence | 61 | 95.3% | Assessed clarity and evidence backing conclusions |

| The value of the research is clearly stated | 52 | 81.3% | Considered the implications and contributions of the study |

| Met minimum quality threshold (≥7 of 10 criteria) | 64 | 100% | Studies scoring at least seven were included in the final review |

| MMAT Quality Dimension | Studies Meeting Criterion | % of Included Studies (n = 64) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clarity of research questions | 64 | 100% | Research questions were clearly stated and well defined |

| Appropriateness of methodology | 61 | 95.3% | Methodological approach matched the study’s aim and design |

| Rigour of data collection | 59 | 92.2% | Data collection was thorough, systematic, and well documented |

| Soundness of data analysis | 57 | 89.1% | Analysis procedures were logically structured and justified |

| Coherence of findings with research questions | 62 | 96.9% | Study findings were consistent and aligned with the stated objectives |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mangai, M.S.; Ayodele, A.A. Reimagining Public Service Delivery: Digitalising Initiatives for Accountability and Efficiency. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 477. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15120477

Mangai MS, Ayodele AA. Reimagining Public Service Delivery: Digitalising Initiatives for Accountability and Efficiency. Administrative Sciences. 2025; 15(12):477. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15120477

Chicago/Turabian StyleMangai, Mary S., and Austin A. Ayodele. 2025. "Reimagining Public Service Delivery: Digitalising Initiatives for Accountability and Efficiency" Administrative Sciences 15, no. 12: 477. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15120477

APA StyleMangai, M. S., & Ayodele, A. A. (2025). Reimagining Public Service Delivery: Digitalising Initiatives for Accountability and Efficiency. Administrative Sciences, 15(12), 477. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15120477