Trusting the Virtual, Traveling the Real: How Destination Trust in Video Games Shapes Real-World Travel Willingness Through Player Type Differences

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Video Game-Induced Tourism

2.2. Trust Transfer Theory in Marketing and Tourism

2.3. Player Types and Their Role in Consumer Behavior

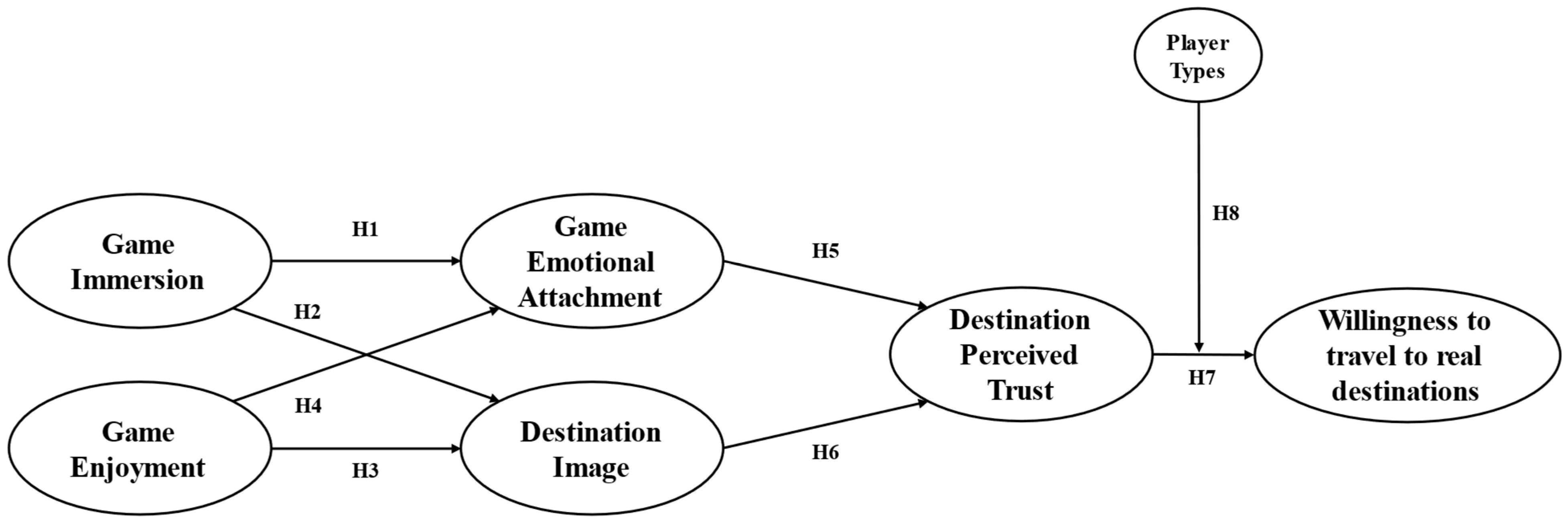

2.4. Hypothesis Development

2.4.1. Game Immersion and Game Emotional Attachment

2.4.2. Game Immersion and Destination Image

2.4.3. Game Enjoyment and Destination Image

2.4.4. Game Enjoyment and Game Emotional Attachment

2.4.5. Game Emotional Attachment and Perceived Destination Trust

2.4.6. Destination Image and Perceived Destination Trust

2.4.7. Perceived Destination Trust and Willingness to Travel to Real Destinations

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Data Collection and Ethical Considerations

3.2.1. Sampling Strategy

3.2.2. Ethical Considerations

3.3. Measurement Scales

3.4. Data Analyses

4. Results

4.1. Sample Characteristics

4.2. Assessment of the Measurement Model

4.3. Assessment of the Structural Model

4.4. Hypothesis Testing

5. Discussion

5.1. Interpretation of Key Findings

5.2. Theoretical Contributions

5.3. Practical Implications

6. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abubakar, A. M. (2016). Does eWOM influence destination trust and travel intention: A medical tourism perspective. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja, 29(1), 598–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakar, A. M., & Ilkan, M. (2016). Impact of online WOM on destination trust and intention to travel: A medical tourism perspective. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 5(3), 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakar, A. M., Ilkan, M., Al-Tal, R. M., & Eluwole, K. K. (2017). EWOM, revisit intention, destination trust and gender. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 31, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S., Zulkurnain, N. N. A., & Khairushalimi, F. I. (2016). Assessing the validity and reliability of a measurement model in structural equation modeling (SEM). British Journal of Mathematics & Computer Science, 15(3), 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akrout, F. (2010). Les méthodes des équations structurelles. Available online: https://www.bibliotheque.nat.tn/BNT/doc/SYRACUSE/1673994/les-methodes-des-equations-structurelles?_lg=fr-FR (accessed on 7 May 2024).

- Al-Ansi, A., & Han, H. (2019). Role of halal-friendly destination performances, value, satisfaction, and trust in generating destination image and loyalty. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 13, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcindor, M., Jackson, D., & Alcindor-Huelva, P. (2022). Heritage places as the settings for virtual playgrounds: Perceived realism in videogames, as a tool for the re-localisation of physical places. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 28(7), 865–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alyahya, M., & McLean, G. (2021). Examining tourism consumers’ attitudes and the role of sensory information in virtual reality experiences of a tourist destination. Journal of Travel Research, 61(7), 1666–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artigas, E. M., Yrigoyen, C. C., Moraga, E. T., & Villalón, C. B. (2017). Determinants of trust towards tourist destinations. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 6(4), 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartle, R. (1995). Hearts, clubs, diamonds, spades: Players who suit MUDs. Journal of MUD Research, 1(1), 19. Available online: https://mud.co.uk/richard/hcds.htm (accessed on 7 May 2024).

- Bi, Y., Yin, J., & Kim, I. (2021). Fostering a young audience’s media-induced travel intentions: The role of parasocial interactions. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 47, 398–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodzin, A., Junior, R. A., Hammond, T., & Anastasio, D. (2020, June 21–25). An immersive virtual reality game designed to promote learning engagement and flow. 2020 6th International Conference of the Immersive Learning Research Network (iLRN) (pp. 193–198), San Luis Obispo, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Bojanowska, A. B., & Surowiec, A. (2022). Effects of brand experience: The case of the witcher brand in the eyes of polish customers. Sustainability, 14(21), 14274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouzaabia, O., Arbia, M. B., Varón, D. J. J., & Chui, K. T. (2024). The consequences of gamification in mobile commerce platform applications. International Journal on Semantic Web and Information Systems, 20(1), 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, N. D., Ahn, S. J., & Kollar, L. M. M. (2020). The paradox of interactive media: The potential for video games and virtual reality as tools for violence prevention. Frontiers in Communication, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, N. D., Oliver, M. B., Rogers, R., Sherrick, B., Woolley, J., & Chung, M. (2016). In control or in their shoes? How character attachment differentially influences video game enjoyment and appreciation. Journal of Gaming & Virtual Worlds, 8(1), 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, N. D., Vandewalle, A., Daneels, R., Lee, Y., & Chen, S. (2023). Animating a plausible past: Perceived realism and sense of place influence entertainment of and tourism intentions from historical video games. Games and Culture, 19(3), 286–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brühlmann, F., Baumgartner, P., Wallner, G., Kriglstein, S., & Mekler, E. D. (2020). Motivational profiling of league of legends players. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calleja, G. (2012). In-game: From immersion to incorporation. Choice Reviews Online, 49(5), 49-2483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, L., Estevão, C., Fernandes, C., & Alves, H. (2017). Film induced tourism: A systematic literature review. Tourism & Management Studies, 13(3), 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, B. H. M., Bertozzi, G. G. C., & Correa, C. (2019). Video games generating tourist demand: Italy and the Assassin’s Creed Series. In Sustainable tourism development (pp. 305–326). Apple Academic Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caselli, S., Polato, F., & Salvador, M. (2021). Journeying to the actual world through digital games: The urban histories reloaded project. Mutual Images Journal, 10, 271–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H. (2024). Comparative analysis of storytelling in virtual reality games vs. traditional games. Journal of Education, Humanities and Social Sciences, 30, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H., Zuo, Y., Law, R., & Zhang, M. (2021). Improving the Tourist’s perception of the tourist destinations image: An analysis of Chinese Kung Fu film and television. Sustainability, 13(7), 3875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X., Huang, Q., Davison, R. M., & Hua, Z. (2015). What drives trust transfer? The moderating roles of seller-specific and general institutional mechanisms. International Journal of Electronic Commerce, 20(2), 261–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coble, K., Ratican, J., & Hutson, J. (2024). Beyond the pixelated mirror: Understanding avatar identity and its impact on in-game advertising and consumer behavior. Metaverse, 4(2), 2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E. L. (2013). What makes good games go viral? The role of technology use, efficacy, emotion and enjoyment in players’ decision to share a prosocial digital game. Computers in Human Behavior, 33, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulson, M., Barnett, J., Ferguson, C. J., & Gould, R. L. (2012). Real feelings for virtual people: Emotional attachments and interpersonal attraction in video games. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 1(3), 176–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csontos, B., & Heckl, I. (2025). The evolution of video game accessibility on Xbox consoles in the Far Cry game series. Universal Access in the Information Society, 24(3), 2447–2466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y., Li, X., Li, J., Wang, H., & Chen, X. (2022). A survey of sampling method for social media embeddedness relationship. ACM Computing Surveys, 55(4), 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuny, C., Fornerino, M., & Helme-Guizon, A. (2015). Can music improve e-behavioral intentions by enhancing consumers’ immersion and experience? Information & Management, 52(8), 1025–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, N. (2013). The psychology of immersion and development of a quantitative measure of immersive response in games (p. 415). Available online: https://cora.ucc.ie/bitstream/10468/1102/2/CurranN_PhD2013PartialRestriction.pdf (accessed on 7 May 2024).

- Çağlar, Ş., & Kocadere, S. A. (2016, July 4–6). Possibility of motivating different type of players in gamified learning environments. International Conference on Education and New Learning Technologies, Barcelona, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, F., Wang, D., & Kirillova, K. (2022). Travel inspiration in tourist decision making. Tourism Management, 90, 104484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lima, E. S., Neggers, M. M. E., Casanova, M. A., & Furtado, A. L. (2025). From images to stories: Exploring player-driven narratives in games. In Communications in computer and information science (pp. 228–242). Springer Nature. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Mascio, D. (2020). Architecture, narrative and interaction in the cityscapes of the Assassin’s Creed series: A preliminary analysis of the design of selected historical cities. In A new perspective of cultural DNA (pp. 125–143). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez-Azcue, J., Almeida-García, F., Pérez-Tapia, G., & Cestino-González, E. (2021). Films and destinations—Towards a film destination: A review. Information, 12(1), 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J. (2021). How video games induce us to travel? Examining the influence of presence and nostalgia on visit intention: Imagination proclivity as a moderator. Available online: https://atrium.lib.uoguelph.ca/xmlui/handle/10214/25685 (accessed on 7 May 2024).

- Dong, J., Dubois, L., Joppe, M., & Foti, L. (2021). How do video games induce us to travel?: Exploring the drivers, mechanisms, and limits of video game-induced tourism. In Audiovisual Tourism Promotion (pp. 153–172). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, L., & Gibbs, C. (2018). Video game–induced tourism: A new frontier for destination marketers. Tourism Review, 73(2), 186–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, L., Griffin, T., Gibbs, C., & Guttentag, D. (2020). The impact of video games on destination image. Current Issues in Tourism, 24(4), 554–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erümit, S. F., Şılbır, L., Erümit, A. K., & Karal, H. (2020). Determination of player types according to digital game playing preferences: Scale development and validation study. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction, 37(11), 991–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folmer, A., Haartsen, T., & Huigen, P. P. P. (2013). Explaining emotional attachment to a protected area by visitors’ perceived importance of seeing wildlife, behavioral connections with nature, and sociodemographics. Human Dimensions of Wildlife, 18(6), 435–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, F., Su, R., & Yu, S. (2008). EGameFlow: A scale to measure learners’ enjoyment of e-learning games. Computers & Education, 52(1), 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuß, C., Steuer, T., Noll, K., & Miede, A. (2014). Teaching the achiever, explorer, socializer, and killer—Gamification in university education. In International conference on serious games (pp. 92–99). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Globa, A., Beza, B. B., & Wang, R. (2022). Towards multi-sensory design: Placemaking through immersive environments—Evaluation of the approach. Expert Systems with Applications, 204, 117614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunderman, H. C. (2024). Cosy video games as digital third places for emotional well-being: Case studies of stardew valley, coffee talk episode 2 and kinder world. Journal of Gaming & Virtual Worlds, 16(3), 333–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, M. R. A., Sami, W., & Sidek, M. H. M. (2017). Discriminant validity assessment: Use of Fornell & Larcker criterion versus HTMT criterion. Journal of Physics Conference Series, 890, 012163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H., Meng, B., Chua, B., Ryu, H. B., & Kim, W. (2019). International volunteer tourism and youth travelers—An emerging tourism trend. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 36(5), 549–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J., Zhang, G., Xu, S., Law, R., & Zhang, M. (2022). Seeing destinations through short-form videos: Implications for leveraging audience involvement to increase travel intention. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1024286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handique, K., & Sarkar, S. (2024). The impact of brand love on customer loyalty: Exploring emotional connection and consumer behaviour. International Research Journal of Multidisciplinary Scope, 05(04), 1104–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homsud, N. (2024). The effect of destination image, travel experience, and media exposure on tourism intentions. Journal of Economics, Business and Management, 318–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y. (2024). From virtual journeys to real travels: Exploring the impact of Chinese-themed digital games on international players’ tourism intentions. Modern Economics & Management Forum, 5(5), 910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y., Backman, S. J., Backman, K. F., & Moore, D. (2012). Exploring user acceptance of 3D virtual worlds in travel and tourism marketing. Tourism Management, 36, 490–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z., Zhu, Y., Hao, A., & Deng, J. (2022). How social presence influences consumer purchase intention in live video com-merce: The mediating role of immersive experience and the moderating role of positive emotions. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 17(4), 493–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, S., Matson-Barkat, S., Pallamin, N., & Jegou, G. (2018). With or without you? Interaction and immersion in a virtual reality experience. Journal of Business Research, 100, 459–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isbister, K. (2016). How games move us. The MIT Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jebbouri, A., Zhang, H., Imran, Z., Iqbal, J., & Bouchiba, N. (2022). Impact of destination image formation on tourist trust: Mediating role of tourist satisfaction. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 845538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junko, Y., Hsu, C., & Liu, T. (2022). Video games as a media for tourism experience. In Information and communication technologies in tourism (pp. 67–71). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juškelytė, D. (2016). Film induced tourism: Destination image formation and development. Regional Formation and Development Studies, 19(2), 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H., & Chen, J. S. (2015). Destination image formation process. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 22(2), 154–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M. J., Lee, C., & Jung, T. (2018). Exploring consumer behavior in virtual reality tourism using an extended stimulus-organism-response model. Journal of Travel Research, 59(1), 69–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchner-Krath, J., Altmeyer, M., Schürmann, L., Kordyaka, B., Morschheuser, B., Klock, A. C. T., Nacke, L., Hamari, J., & von Korflesch, H. F. (2024). Uncovering the theoretical basis of user types: An empirical analysis and critical discussion of user typologies in research on tailored gameful design. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 190, 103314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocadere, S. A., & Çaglar, S. (2018). Gamification from player type perspective: A case study. Educational Technology & Society, 21(3), 12–22. Available online: https://dblp.uni-trier.de/db/journals/ets/ets21.html#KocadereC18 (accessed on 7 May 2024).

- Kock, F., Josiassen, A., & Assaf, A. G. (2016). Advancing destination image: The destination content model. Annals of Tourism Research, 61, 28–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacic, S., & Sagovnovic, I. (2022). Exploring the relationship between tourists’ emotional experience, destination personality perception, satisfaction and behavioral intentions. Psihologija, 56(3), 371–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krappala, K., Kemppinen, L., & Kemppinen, E. (2024). Achievers, explorers, wanderers, and intellectuals: Educational interaction in a Minecraft open-world action-adventure game. Computers and Education Open, 6, 100172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamerichs, N. (2018). Hunters, climbers, flâneurs (pp. 161–169). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavuri, R., & Akram, U. (2023). Role of virtual reality authentic experience on affective responses: Moderating role virtual reality attachment. Journal of Ecotourism, 23(3), 347–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J., & Eden, A. (2023). How motivation and digital affordances shape user behavior in a virtual world. Media Psychology, 26(5), 551–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. I., Dirks, K. T., & Campagna, R. L. (2022). At the heart of trust: Understanding the integral relationship between emotion and trust. Group & Organization Management, 48(2), 546–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y., Kim, S., Lee, C., & Kim, S. (2014). The impact of a mega event on visitors’ attitude toward hosting destination: Using trust transfer theory. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 31(4), 507–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leuze, C., & Leuze, M. (2021, March 27–April 1). Shared augmented reality experience between a Microsoft flight simulator user and a user in the real world. 2021 IEEE Conference on Virtual Reality and 3D User Interfaces Abstracts and Workshops (VRW), Lisbon, Portugal. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C., & Liu, C. (2020). The effects of empathy and persuasion of storytelling via tourism micro-movies on travel willingness. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 25(4), 382–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, T., Chen, M., Yu, C., & Xu, J. (2024). Research on the influence of tourism destination embedding in online games on players’ travel intentions. Journal of Management Analytics, 11(4), 601–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, T., & Yu, C. (2019). Impacts of online images of a tourist destination on tourist travel decision. Tourism Geographies, 21(4), 635–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, W. M. (2024). What is quantitative research? An overview and guidelines. Australasian Marketing Journal, 33(3), 325–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J., Wang, C., Fang, S., & Zhang, T. (2019). Scale development for tourist trust toward a tourism destination. Tourism Management Perspectives, 31, 383–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, S. M. C., Ruediger, K. H., & Demetris, V. (2012). Brand emotional connection and loyalty. Journal of Brand Management, 20(1), 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luong, T. (2024). The moderating role of e-word of mouth in the relationships between destination source credibility, awareness, attachment, travel motivation, and travel intention: A case study of Vietnamese film tourism. International Journal of Tourism Research, 26(4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, X., & Wu, A. (2021). The role of extraordinary sensory experiences in shaping destination brand love: An empirical study. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 38(2), 179–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchiori, E., & Önder, I. (2014). Reframing the image of a destination: A Pre-Post study on social media exposure. In Information and communication technologies in tourism (pp. 335–347). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellecker, R., Lyons, E. J., & Baranowski, T. (2013). Disentangling fun and enjoyment in exergames using an expanded design, play, experience framework: A narrative review. Games for Health Journal, 2(3), 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michopoulou, E., Siurnicka, A., & Moisa, D. G. (2021). Experiencing the story. In Advances in hospitality, tourism and the services industry (AHTSI) book series (pp. 240–256). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mochocki, M. (2021). Heritage sites and video games: Questions of authenticity and immersion. Games and Culture, 16(8), 951–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, K. (2015). Painting the town blue and green: Curating street art through urban mobile gaming. M/C Journal, 18(4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, M., Aliabadi, K., AhmadAbadi, M. R. N., Ardakani, S. P., & Nasab, Y. M. (2020). Investigating the components of educational game design based on explorer player style: A systematic literature review. DOAJ (DOAJ: Directory of Open Access Journals), 11, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moura, F. T., Gnoth, J., & Deans, K. R. (2014). Localizing cultural values on tourism destination websites. Journal of Travel Research, 54(4), 528–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolaou, A. I., & Masoner, M. M. (2013). Sample size requirements in structural equation models under standard conditions. International Journal of Accounting Information Systems, 14(4), 256–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oleksy, T., & Wnuk, A. (2017). Catch them all and increase your place attachment! The role of location-based augmented reality games in changing people—Place relations. Computers in Human Behavior, 76, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, M. B., & Bartsch, A. (2009). Appreciation as audience response: Exploring entertainment gratifications beyond hedonism. Human Communication Research, 36(1), 53–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, M. B., Bowman, N. D., Woolley, J. K., Rogers, R., Sherrick, B. I., & Chung, M. (2015). Video games as meaningful entertainment experiences. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 5(4), 390–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, Z., Gursoy, D., & Sharma, B. (2017). Role of trust, emotions and event attachment on residents’ attitudes toward tourism. Tourism Management, 63, 426–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomba, A. (2018). Virtual perceived emotional intelligence: How high brand loyalty video game players evaluate their own video game play experiences to repair or regulate emotions. Computers in Human Behavior, 85, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S., & Hsu, C. H. C. (2014). Framing tourism destination image: Extension of stereotypes in and by travel media. In Travel journalism: Exploring production, impact and culture (pp. 60–80). Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passos, A., Costa, L. V., & Zagalo, N. (2024). “Looking up the camera to play right”: An interview study of the implications of cinematic storytelling in game design. In Communications in computer and information science (pp. 86–100). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrino, A. (2024). Experience at the core: Digital customer experience and customer satisfaction. In Decoding digital consumer behavior: Bridging theory and practice (pp. 141–149). Springer Nature. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y., & Ke, D. (2015). Consumer trust in 3D virtual worlds and its impact on real world purchase intention. Nankai Business Review International, 6(4), 381–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peri, J. (2024). Video gaming industry in the US. International Journal of Science and Research Archive, 11(1), 1257–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y., Han, R., & Dong, Y. (2023). An attachment-based management framework of destination attributes: Drawing on the appraisal theories of emotion. Journal of Travel Research, 63(1), 234–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rainoldi, M., Van Den Winckel, A., Yu, J., & Neuhofer, B. (2022). Video game experiential marketing in tourism: Designing for experiences. In Information and communication technologies in tourism (pp. 3–15). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, M. P. M. (2018). Film induced tourism model-A qualitative research study. Asian Journal of Research in Marketing, 7(2), 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Moreno, C., & Leorke, D. (2020). Promoting Yokosuka through videogame tourism (pp. 38–63). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapp, A. (2021). Time, engagement and video games: How game design elements shape the temporalities of play in massively multiplayer online role-playing games. Information Systems Journal, 32(1), 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rativa, A. S., Postma, M., & Van Zaanen, M. (2020). The influence of game character appearance on empathy and immersion: Virtual non-robotic versus robotic animals. Simulation & Gaming, 51(5), 685–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reijnders, S., Martens, E., Castro, D., Póvoa, D., Nanjangud, A., & Schiavone, R. (2024). Media, place and tourism. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, R., Woolley, J., Sherrick, B., Bowman, N. D., & Oliver, M. B. (2016). Fun versus meaningful video game experiences: A qualitative analysis of user responses. The Computer Games Journal, 6(1–2), 63–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryoo, J. (2015). The influence of brand experience and positive emotion on consumer-brand relationship -Focusing on smartphone brand. Journal of the Korea Contents Association, 15(10), 495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmond, M., & Salmond, J. (2016). The gamer as tourist (pp. 151–163). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, Y., Buchanan-Oliver, M., & Fam, K. (2015). Advancing research on computer game consumption: A future research agenda. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 14(6), 353–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sezgin, S. (2020). Digital player typologies in gamification and game-based learning: A meta-synthesis. Bartın University Journal of Faculty of Education, 9(1), 49–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S., Stylidis, D., & Woosnam, K. M. (2022). From virtual to actual destinations: Do interactions with others, emotional solidarity, and destination image in online games influence willingness to travel? Current Issues in Tourism, 26(9), 1427–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shreffler, J., & Huecker, M. R. (2021). Hypothesis testing, P values, confidence intervals, and significance. StatPearls. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32491353/ (accessed on 7 May 2024).

- Shuhua, Y., Tianyi, C., & Chengcai, T. (2024). The impact of tourism destination factors in video games on players’ intention to visit. Journal of Resources and Ecology, 15(2), 474–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sifonis, C. M. (2017, October 15–18). Attributes of ingress gaming locations contributing to players’ place attachment. CHI PLAY ‘17 Extended Abstracts: Extended Abstracts Publication of the Annual Symposium on Computer-Human Interaction in Play (pp. 569–575), Amsterdam, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, R., & Correia, A. (2016). Places and tourists: Ties that reinforce behavioural intentions. Anatolia, 28(1), 14–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjöblom, M., & Hamari, J. (2016). Why do people watch others play video games? An empirical study on the motivations of Twitch users. Computers in Human Behavior, 75, 985–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobaih, A. E. E., & Elshaer, I. A. (2022). Personal traits and digital entrepreneurship: A mediation model using SmartPLS data analysis. Mathematics, 10(21), 3926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, K. J. (2003). Trust transfer on the world wide web. Organization Science, 14(1), 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stratton, S. J. (2021). Population research: Convenience sampling strategies. Prehospital and Disaster Medicine, 36(4), 373–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L., Lian, Q., & Huang, Y. (2019). How do tourists’ attribution of destination social responsibility motives impact trust and intention to visit? The moderating role of destination reputation. Tourism Management, 77, 103970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L., Yang, Q., Swanson, S. R., & Chen, N. C. (2021). The impact of online reviews on destination trust and travel intention: The moderating role of online review trustworthiness. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 28(4), 406–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasci, A. D., Uslu, A., Stylidis, D., & Woosnam, K. M. (2021). Place-oriented or people-oriented concepts for destination loyalty: Destination image and place attachment versus perceived distances and emotional solidarity. Journal of Travel Research, 61(2), 430–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, T., & Liu, J. (2007). Consumer trust in e-commerce in the United States, Singapore and China. Omega, 35(1), 22–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toh, W. (2022). The player experience and design implications of narrative games. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction, 39(13), 2742–2769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomlinson, C. (2025). Agency, consent and trauma: How narrative shapes player experiences in Baldur’s Gate 3. Journal of Gaming & Virtual Worlds, 17(1), 73–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, C., Tunggal, J., & Brown, S. (2022). Character immersion in video games as a form of acting. Psychology of Popular Media, 12(4), 405–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzanelli, R. (2019). Unpopular culture: Ecological dissonance and sustainable futures in media-induced tourism. The Journal of Popular Culture, 52(6), 1250–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Nuenen, T. (2023). Traveling through video games. Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veasna, S., Wu, W., & Huang, C. (2012). The impact of destination source credibility on destination satisfaction: The mediating effects of destination attachment and destination image. Tourism Management, 36, 511–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H., Gao, Z., Zhang, X., Du, J., Xu, Y., & Wang, Z. (2024). Gamifying cultural heritage: Exploring the potential of immersive virtual exhibitions. Telematics and Informatics Reports, 15, 100150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, J. (2017). Designing engaging experiences with location-based augmented reality games for urban tourism environments. Available online: http://eprints.bournemouth.ac.uk/27176/ (accessed on 7 May 2024).

- Wills, J. (2021). “Ain’t the American dream grand”: Satirical play in rockstar’s grand theft auto V. European Journal of American Studies, 16(3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woosnam, K. M., Stylidis, D., & Ivkov, M. (2020). Explaining conative destination image through cognitive and affective destination image and emotional solidarity with residents. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 28(6), 917–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F., Tian, F., Buhalis, D., Weber, J., & Zhang, H. (2021). Tourists as Mobile Gamers: Gamification for tourism marketing (pp. 96–114). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y. (2021). Video games and tourism—Tourism motivations of Chinese video game players [Doctoral dissertation, Open Access Te Herenga Waka-Victoria University of Wellington]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yersüren, S., & Özel, Ç. H. (2023). The effect of virtual reality experience quality on destination visit intention and virtual reality travel intention. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Technology, 15(1), 70–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, T., Tang, J., Ye, S., Tan, X., & Wei, W. (2021). Virtual reality in destination marketing: Telepresence, social presence, and tourists’ visit intentions. Journal of Travel Research, 61(8), 1738–1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J. (2018). Trust transfer in the sharing economy—A survey-based approach. Junior Management Science, 3(2), 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X., Obst, P. L., White, K. M., O’Connor, E. L., & Longman, H. (2021). Network analysis among World of Warcraft players’ social support variables: A two-way approach. Journal of Gaming & Virtual Worlds, 13(3), 249–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolkifly, I. A., Yao, D. N. L., Theng, L. C., Sin, C. Z., An, H. Z., Jarad, M. I. Q. B., Hatta, N. M. H. B. M., & Muniandy, V. A. (2023). Leveraging Platform-Based games to propel virtual tourism. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 13(8), 897–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żemła, M., & Bielak, M. (2024). Video game-induced tourism as a pathway for improving the tourist experience (pp. 160–172). Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Constructs | Measurement Items | Cronbach’s Alphas | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Game Immersion | GI1: The video game created a virtual environment that fully immersed me in its world. | 0.892 | 0.91 | 0.64 |

| GI2: At times, I was so engaged in the game that I lost awareness of my real surroundings. | ||||

| GI3: While playing, my body was in the room, but my mind was fully inside the game world. | ||||

| GI4: The game experience made me temporarily forget the reality of the outside world. | ||||

| GI5: During gameplay, I was so absorbed that I forgot about events before or after my session. | ||||

| GI6: The game world was so immersive that I lost awareness of my immediate physical surroundings. | ||||

| Game Enjoyment | GE1: When I play games featuring real-world destinations, I have a great time. | 0.812 | 0.82 | 0.73 |

| GE2: When I play games that include real-world locations, I find the experience highly entertaining. | ||||

| GE3: Playing games with realistic destinations is enjoyable and fun for me. | ||||

| Game Emotional Attachment | GEA1: I feel very attached to the virtual destinations I explore in the video game. | 0.871 | 0.88 | 0.73 |

| GEA2: The video games locations I visit mean a lot to me. | ||||

| GEA3: I feel at home in the virtual environments created by the game. | ||||

| GEA4: I would like to spend more time exploring these video game destinations. | ||||

| Destination Image | DI1: Overall, traveling to a destination I see in a video game is: Bad (1)–Good (5) | 0.861 | 0.87 | 0.71 |

| DI2: Overall, traveling to a destination I see in a video game is: Negative (1)–Positive (5) | ||||

| DI3: Overall, traveling to a destination I see in a video game is: Unfavorable (1)–Favorable (5) | ||||

| DI4: Overall, traveling to a destination I see in a video game is: Not worthwhile (1)–Worthwhile (5) | ||||

| Destination Perceived Trust | DPT1: The real-world destination depicted in the video game is trustworthy. | 0.756 | 0.77 | 0.51 |

| DPT2: The information presented about the destination in the video game is reliable. | ||||

| DPT3: The destination portrayed in the video game keeps promises and commitments related to its representation. | ||||

| DPT4: The destination in the video game reflects my best interests and expectations for real-world visits. | ||||

| DPT5: The portrayal of the destination in the video game meets my expectations of its real-world counterpart. | ||||

| Willingness to travel to real destinations | WTD1: After exploring the virtual representation of a destination in a video game, I want to visit that real-world destination. | 0.85 | 0.86 | 0.77 |

| WTD2: I am interested in traveling to the real-world destination I encountered in the game. | ||||

| WTD3: I would recommend visiting the real-world destination portrayed in the game to others. | ||||

| Players Types | The Bartle Test classifies players of multiplayer online games into categories based on Bartle’s taxonomy of player types |

| Demographic | Total Number | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 198 | 75.6% |

| Female | 64 | 24.4% |

| Age (years) | ||

| ≤18 | 15 | 5.7% |

| 18–24 | 158 | 60.3% |

| 25–34 | 66 | 25.2% |

| 35–44 | 16 | 6.1% |

| 45–54 | 7 | 2.7% |

| 55+ | 7 | 2.7% |

| Gaming Frequency | ||

| Daily | 132 | 50.5% |

| Several times a week | 47 | 18% |

| Weekly | 37 | 14% |

| A few times a month | 24 | 9% |

| Rarely | 22 | 8.5% |

| Destination Image | Game Emotional Attachment | Destination Perceived Trust | Type Player | Willingness to Travel to Real Destinations | Game Enjoyment | Game Immersion | Type Player × Trust | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Destination Image | ||||||||

| Game Emotional Attachment | 0.404 | |||||||

| Destination Perceived Trust | 0.526 | 0.700 | ||||||

| Type Player | 0.308 | 0.104 | 0.304 | |||||

| Willingness to travel to real destinations | 0.825 | 0.360 | 0.726 | 0.475 | ||||

| Game Enjoyment | 0.397 | 0.488 | 0.684 | 0.181 | 0.583 | |||

| Game Immersion | 0.319 | 0.675 | 0.683 | 0.115 | 0.303 | 0.494 | ||

| Type Player × Trust | 0.283 | 0.147 | 0.079 | 0.216 | 0.361 | 0.122 | 0.058 |

| Destination Image | Game Emotional Attachment | Destination Perceived Trust | Type Player | Willingness to Travel to Real Destinations | Game Enjoyment | Game Immersion | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Destination Image | 0.839 | ||||||

| Game Emotional Attachment | 0.352 | 0.852 | |||||

| Destination Perceived Trust | 0.433 | 0.551 | 0.712 | ||||

| Type Player | 0.287 | 0.097 | 0.274 | 1.000 | |||

| Willingness to travel to real destinations | 0.708 | 0.312 | 0.609 | 0.436 | 0.877 | ||

| Game Enjoyment | 0.337 | 0.413 | 0.540 | 0.163 | 0.485 | 0.853 | |

| Game Immersion | 0.318 | 0.623 | 0.576 | 0.088 | 0.283 | 0.428 | 0.801 |

| Original_Sample | T_Statistics | p_Values | |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1: Game_Immersion -> Game_Emotional_Attachment | 0.546 | 9642 | 0.000 |

| H2: Game_Immersion -> Destination Image | 0.212 | 3170 | 0.002 |

| H3: Game_Enjoyment -> Destination_Image | 0.246 | 3553 | 0.000 |

| H4: Game Enjoyment -> Game Emotional Attachment | 0.179 | 2660 | 0.008 |

| H5: Game_Emotional_Attachment -> Destination_Perceived Trust | 0.455 | 8262 | 0.000 |

| H6: Destination_Image -> Destination_Perceived_Trust | 0.273 | 4834 | 0.000 |

| H7: Destination_Perceived_Trust -> Willingnes_to_travel_to_real_destinations | 0.527 | 12,400 | 0.000 |

| H8: Player_Types × Destination_Perceived_Trust -> Willingnes_to_travel_to_real_destinations | 0.273 | 6402 | 0.000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ben Arbia, M.; Bouzaabia, R.; Beck, M. Trusting the Virtual, Traveling the Real: How Destination Trust in Video Games Shapes Real-World Travel Willingness Through Player Type Differences. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 470. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15120470

Ben Arbia M, Bouzaabia R, Beck M. Trusting the Virtual, Traveling the Real: How Destination Trust in Video Games Shapes Real-World Travel Willingness Through Player Type Differences. Administrative Sciences. 2025; 15(12):470. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15120470

Chicago/Turabian StyleBen Arbia, Mohamed, Rym Bouzaabia, and Marie Beck. 2025. "Trusting the Virtual, Traveling the Real: How Destination Trust in Video Games Shapes Real-World Travel Willingness Through Player Type Differences" Administrative Sciences 15, no. 12: 470. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15120470

APA StyleBen Arbia, M., Bouzaabia, R., & Beck, M. (2025). Trusting the Virtual, Traveling the Real: How Destination Trust in Video Games Shapes Real-World Travel Willingness Through Player Type Differences. Administrative Sciences, 15(12), 470. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15120470