1. Introduction

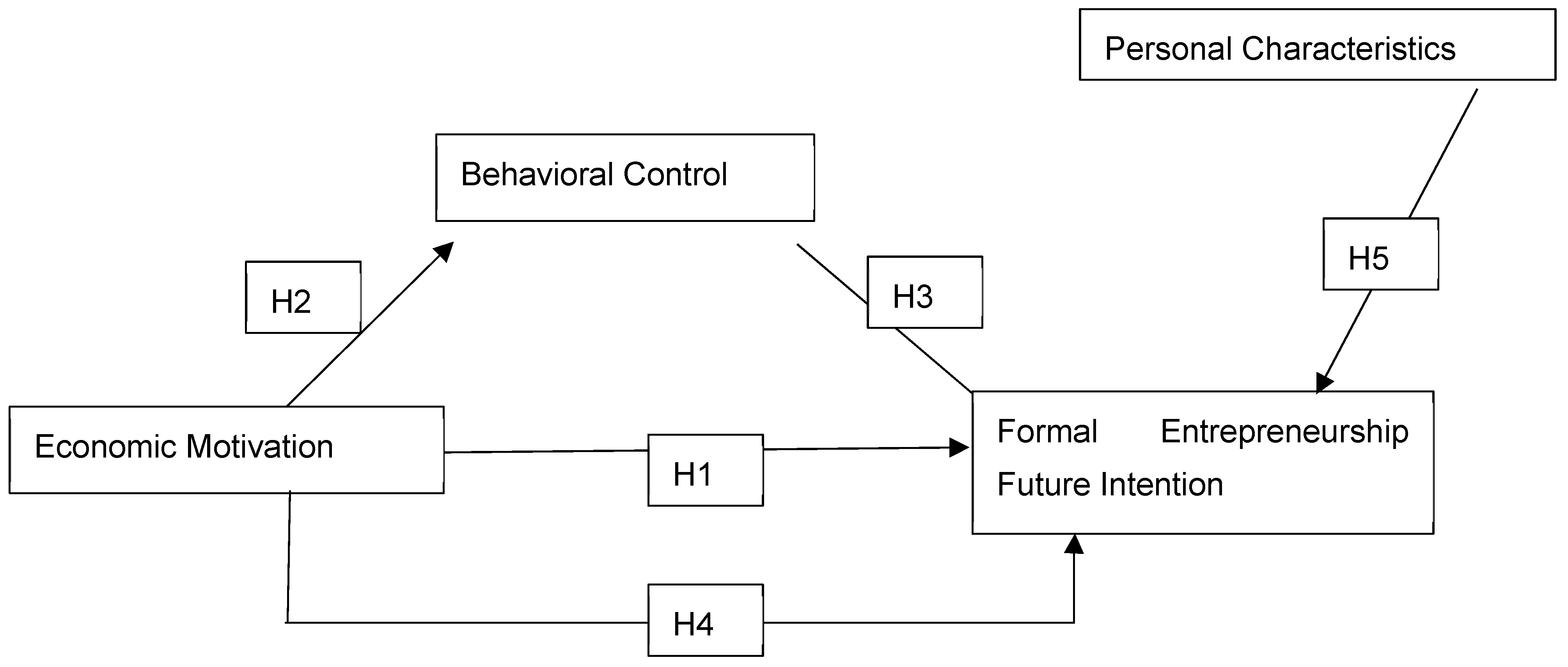

The transformative potential of entrepreneurship for economic development is widely acknowledged. However, in many developing nations, a significant portion of this activity occurs within the informal economy, a sector characterised by operations outside the formal structures of registration, taxation, and legal protection (

Williams & Shahid, 2016). Stated that in Nigeria, one of Africa’s largest economies, the informal sector is estimated to be a dominant force, yet its potential remains locked in a cycle of limited growth and vulnerability. Comprehending the factors that facilitate the transition of informal enterprises into the formal sector is not merely an academic endeavour but an essential requirement for promoting inclusive and sustainable economic development. This study focuses explicitly on this transition process within the Nigerian context and investigates the psychological mechanisms that underpin an informal entrepreneur’s decision to formalise his or her business.

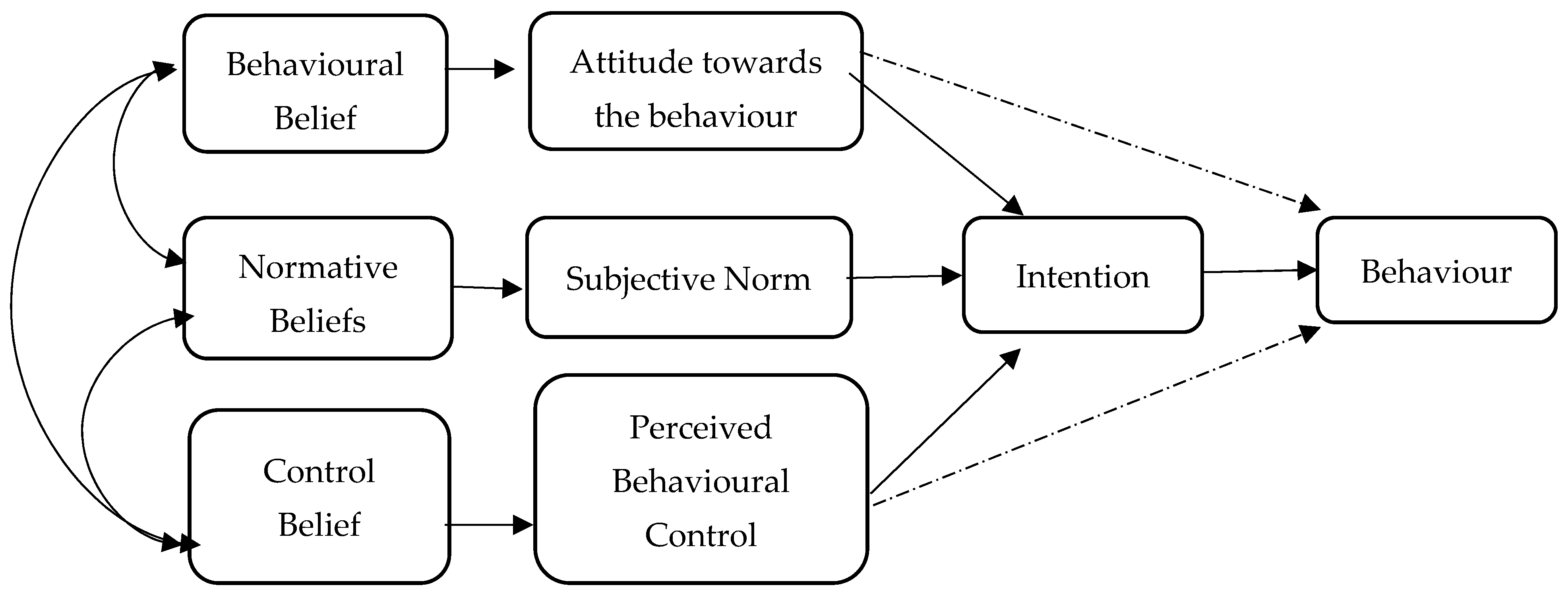

A dominant framework for understanding entrepreneurial behaviour is the theory of planned behaviour (TPB), which posits that intention, a precursor to behaviour, is shaped by attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control (

Ajzen, 1991). While this model has been extensively validated in predicting general entrepreneurial intentions (

Haddoud et al., 2024), its application to the formalised intentions of existing informal entrepreneurs remains limited. A critical puzzle persists on the notion that despite clear economic motivations for formalisation, such as access to credit and new markets (

A. A. W. Ayeni, 2025), many entrepreneurs remain hesitant. In this study, it is argued that this gap between motivation and action can be explained by a missing psychological element: behavioural control. This study adapts the TPB’s concept of perceived behavioural control to capture an informal entrepreneur’s conviction in their ability to navigate the formalisation process successfully. Consequently, this research addresses a clear gap in the literature by asking: To what extent does behavioural control mediate the relationship between economic motivation and formalisation intentions among informal entrepreneurs? This study aims to fill this gap by proposing and testing a mediation model within the TPB framework. The study employs a quantitative survey methodology, focusing on the informal electronics sector in South-West Nigeria, a vibrant and sizable region of entrepreneurial activities. Data collected from a sample of informal entrepreneurs was analysed using Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) to test the hypothesis that behavioural control is the critical mechanism through which economic motivation translates into formalisation intentions.

The relevance of this inquiry is twofold. For theory, it refines the TPB by testing its applicability in the distinct context of entrepreneurial transition. For policy, it moves the discourse beyond purely financial incentives, emphasising that there must be interventions that build entrepreneurial capability and self-efficacy. This article offers three key contributions. Theoretically, it extends the TPB by introducing and testing a mediation model that explains the psychological process of formalisation. Methodologically, it demonstrates the adaptation of TPB scales to the specific behaviour of formalisation. Practically, its findings will inform the design of targeted support programmes for informal entrepreneurs. The paper is structured as follows:

Section 1 presents the introductory aspect of the study,

Section 2 presents the literature review and hypothesis development;

Section 3 outlines the methodology;

Section 4 details the results; and

Section 5 discusses the findings, implications, limitations, and conclusions.

3. Methodology

This study employs a quantitative research design based on the secondary analysis of a pre-existing dataset. The data were originally collected by

Adebanji et al. (

2018) and subsequently extended and analyzed by

A. W. Ayeni et al. (

2021) in their investigation of social motivations for informal entrepreneurship. This study repurposes this robust dataset to specifically investigate the mediating role of behavioral control between economic motivation and formalization intentions (see

Appendix A). The use of secondary data is justified as it provides access to a large, carefully collected sample of a hard-to-reach population (informal entrepreneurs) and allows for the efficient testing of new hypotheses on existing data (

Smith, 2020). The data were drawn from a cross-sectional survey of informal electronics entrepreneurs operating in six major marketplaces across South-West Nigeria. Due to the absence of a formal sampling frame for this population, the original researchers employed a multi-stage sampling procedure. Therefore, the study established a sampling frame by mapping six major electronics markets, creating an estimated population of over 5000 entrepreneurs.

This region represents a significant hub for informal entrepreneurial activity. The target population was informal electronics entrepreneurs and was defined as business owners operating without formal registration, taxation, or legal protection in selected markets. A definitive sampling frame was unavailable due to the transient and unregistered nature of this population. Therefore, the original researchers (

Adebanji et al., 2018) established a sampling frame by first conducting a comprehensive mapping of the six major electronics markets: Osun’s Fagbese Adenle Market (estimated N = 427), Ogun’s Okelewo Market (N = 672), Ekiti’s Ayo Fayose Market (N = 334), Oyo’s Bola Ige International Market (N = 1136), Ondo’s Olukayode Complex (N = 474), and Lagos’ Computer Village (N = 2255), creating a total estimated population of over 6000 entrepreneurs. Given the absence of a formal list, a multi-stage sampling procedure was employed. As earlier identified, the six markets were purposively selected as they are the largest and most representative electronics hubs in the region.

Within each market, a combination of quota sampling and link-tracing (snowball) sampling was used. From the study of

Adebanji et al. (

2018), the researcher assistant initially engaged with market gatekeepers (e.g., union leaders) to identify and recruit an initial quota of participants from different sections of the market. Subsequently, these participants were asked to refer other eligible informal entrepreneurs in their network. Using a formula for infinite populations (

Kumar, 2012) with a 95% confidence level and a 5% margin of error, a minimum sample size of 385 was calculated. To account for potential non-response and ensure robust subgroup analysis, a target sample of 600 was set. Trained research assistants administered structured questionnaires in person. A total of 544 usable questionnaires were retrieved, yielding a response rate of approximately 90.7%. All constructs were measured using reflective indicators on a five-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly Disagree to 5 = Strongly Agree), unless otherwise specified.

The economic Motivation was measured with seven items adapted from

Schneider and Williams (

2013), assessing the drive to formalize based on financial benefits (e.g., “I intend to formalize my business to access bank loans”). The behavioral control was measured with four items adapted from

Ajzen (

2020), capturing the perceived capability to formalize (e.g., “I have the necessary skills to complete the business registration process”). On the parameter of the future Formalization Intention, measurement was done with items from

Williams and Nadin (

2010), assessing the strength of the entrepreneur’s plan to formalize (e.g., “I have a concrete plan to register my business in the near future”). The control variables, having items covering the personal characteristics as formative controls, such as age of Business (ordinal categories), educational qualification (nominal categories), and primary reason for business setup (nominal categories: additional income, survival, etc.), were operationalized as per

A. W. Ayeni et al. (

2021).

The data were analyzed using Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) with SmartPLS 4 software. PLS-SEM was deemed appropriate as it is well-suited for predictive research models that include mediating effects and formative constructs (

Hair et al., 2019). The analysis followed a two-step approach: assessment of the measurement model and assessment of the structural model. The provision of this stems from the commencement of the reliability and validity of the reflective constructs, being evaluated by examining internal consistency (Composite Reliability), indicator loadings, convergent validity (Average Variance Extracted), and discriminant validity (Fornell–Larcker Criterion). This was followed by the hypothesized relationships, being tested by examining the path coefficients, their significance levels, and the coefficient of determination (R

2). The significance of the direct and mediating effects (H4) was assessed using a bootstrapping procedure with 5000 subsamples to generate t-statistics and confidence intervals.

4. Results

As outlined in the methodology

Section 3 of this write-up, Smart PLS-SEM was employed to analyse the collected data from various locations, assessing the study’s proposed hypotheses. The following tables present the results, highlighting the distribution of respondents’ demographic characteristics. The reflective latent variables in the structural models have been examined before using regression analysis of truth; a measurement model with low reliability and validity can lead to constructs that are difficult to interpret and may result in misleading correlations. On this note,

Table 1 presents a set of commonly used metrics for evaluating PLS-SEM measurement models, which include behavioural control (BC), Economic Motivation (EM) and Future Intention to transition into Formal Entrepreneurship (FI).

To evaluate the reliability of a reflective factor solution, this research adopted the commonly used three key indicators: Average Variance Extracted (AVE), Cronbach’s alpha, and composite reliability. AVE reflects how much of the variance in the indicators was captured by the underlying latent variable, and it should ideally be greater than 0.50. Cronbach’s alpha checks how consistent the indicators are with each other. Values above 0.70 are acceptable (

Malhotra, 2010, p. 287). Composite reliability, which assesses internal consistency like Cronbach’s alpha but is not influenced by the number of indicators, should be at least 0.80 for models with around five to eight items (

Netemeyer et al., 2003). In this study, all three measures exceeded their respective thresholds for each latent variable, indicating that the measurement model has strong reliability. In alignment with this, it can be seen that the behavioral control, economic motivation and future intention achieved a Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.898, 0.829 and 0.815. The Composite Reliability (CR (rho_a)) was deemed to be 0.902, 0.854 and 0.833 for the behavioral control, economic motivation and future intention, while the AVE had 0.767, 0.497 and 0.730, respectively. Thus, all constructs successfully met the AVE criterion, with values greater than 0.5 except the economic motivation, demonstrating strong convergent validity. Additionally, the Cronbach’s Alpha values for all constructs were above the 0.7 threshold, highlighting excellent internal reliability. The validation of other construct criteria made them viable for use in this research.

The Fornell–Larcker criterion (

Fornell & Larcker, 1981) approach is widely accepted for its role in assessing discriminant validity. This idea means a concept is truly distinct if its AVE is higher than how much it overlaps with any other concept. In plain terms, a construct should, of necessity, relate more closely to its measures than to those of other constructs in the model.

Table 2 presents the bivariate correlation coefficients between pairs of constructs in the off-diagonal cells, while the diagonal entries represent the square roots of the AVEs, reflecting the average correlations between each construct and its indicators.

Table 3 illustrates this evaluation with the square roots of the Average Variance Extracted (AVE), bolded along the diagonal. The values listed are checked against the correlations between constructs presented below the diagonal. The results show that each construct’s AVE square root is higher than its correlations with other constructs. This further confirms that the model has good discriminant validity, meaning the indicators clearly set the constructs apart.

The HTMT ratio presents another way to check discriminant validity by comparing average correlations between different constructs and within the same one. Values below 0.85 (or 0.90 for a less strict view) suggest the validity is acceptable. In the context of this study, all HTMT values were found to be below the 0.85 benchmark, indicating that the constructs are sufficiently distinct from one another. This finding provides additional support for the presence of discriminant validity (see

Table 2). This outcome affirms that the model demonstrates satisfactory discriminant validity, indicating that the indicators meaningfully distinguish between the constructs. Given that the diagonal values surpass the off-diagonal correlations, discriminant validity is supported. Following this validation, the next stage of analysis involves the presentation and interpretation of regression weights within the inner model, linking latent constructs to their respective observed variables.

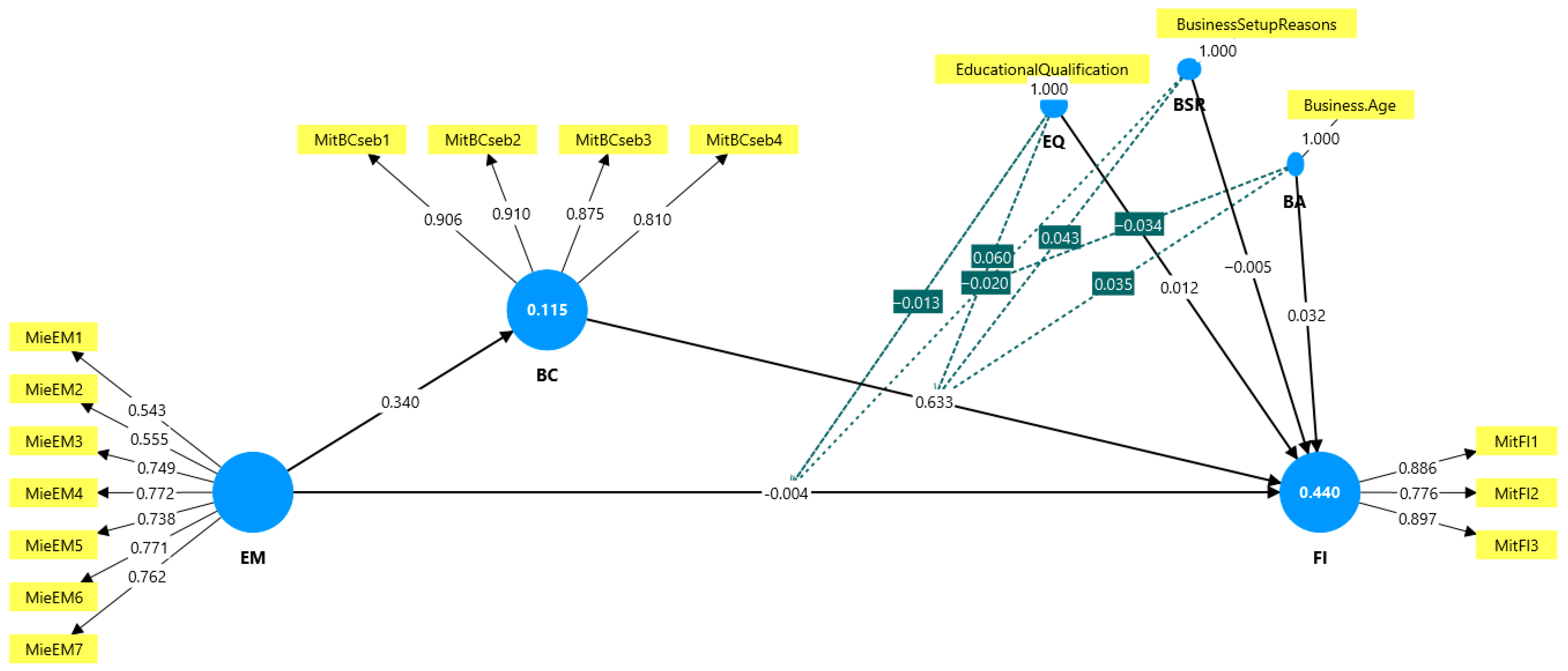

Figure 1 illustrates the standardized regression weights and coefficients of determination (R

2) for the full sample.

The Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) value of 0.058 (see

Table 3) is well below the commonly accepted threshold of 0.08, indicating only a minimal discrepancy between the observed and predicted correlations. This result suggests a satisfactory overall model fit and lends further support to the reliability and adequacy of the structural equation model.

4.1. Structural Model Outcome and Test of Hypothesis

The economic motivation constructs (EM), which include profiting through informality, family-focused income, informality boosts livelihood and shared success through affiliation, did not significantly affect the informal entrepreneurs to transition into formal entrepreneurs in South-West Nigeria (β = 0.032, p = 0.335, H1 not supported). This may be attributed to many informal entrepreneurs perceiving the formal sector as entangled with bureaucracy, regulatory burdens, and inflexible tax regimes that might offset or even outweigh any promised financial benefits. The behavioral control construct (BC), which includes entrepreneurial growth ambition, elevating professional identity and liberation through entrepreneurship, had a positive significant impact on the economic motivation (β = 0.340, p = 0.000, H2 supported). This means that financial drive is often a real goal that makes an entrepreneur feel more in charge of the results of their business. The perception that economic needs can be met through planning and strategic action enhances individuals’ sense of behavioral control, reinforcing their belief in their ability to achieve financially rewarding outcomes. Furthermore, behavioral control positively influences future intention, which includes constructs such as formal business aspirations, ten-year formal business vision and dream of formal entrepreneurship, which was seen to have a positive significance on future intention (β = 0.633, p = 0.000, H3 supported). The results indicate that when informal entrepreneurs possess a robust sense of behavioral control over their capacity to engage in entrepreneurial acts, they are more inclined to have definitive and committed intentions to become formal entrepreneurs in the future. This encompasses ambitions to establish a registered enterprise, a long-term vision (such as a decade-long strategy), inside the official economy.

The study demonstrated that behavioral control strongly mediates the link between economic motivation and future intention, evidenced by a positive and statistically significant indirect impact (β = 0.115,

p = 0.000), thus corroborating hypothesis H4. In terms of explanatory power,

Figure 3 demonstrates that the behavioural control (BC) construct accounts for 11.5% of the model’s variance (R

2 = 0.115), reflecting a moderate level of predictive accuracy. This indicates that the exogenous variables in the model collectively explain 11.5% of the variance in behavioural control. While this highlights the model’s relevance, it also suggests that there are additional, unmeasured factors that may influence entrepreneurs’ intentions. For the future intention (FI) construct, the model explains 43.9% of its variance (R

2 = 0.439), representing a strong level of predictive accuracy. This result implies that more than half of the variance in loyalty is effectively explained by antecedent variables, particularly the behavioral construct. The high R

2 value for future intention (FI) underscores the model’s ability to capture the critical factors driving the informal entrepreneurs’ intentions to transition. (see

Table 4 and

Table 5 for details). This outcome indicates that economically driven people are more inclined to establish robust future intentions for formal entrepreneurship when they perceive a feeling of control over their activities. Behavioral control functions as a conduit; individuals who see themselves as capable of managing formal business needs are more inclined to convert their financial aspirations into tangible plans.

Personal Characteristics, which include constructs such as educational qualification, business set up reasons, and business age, did not significantly moderate the behavioural control mediation relationship between the economic motivation and future intention (β = 0.012, −0.005 and 0.032;

p = 0.750, 0.887 and 0.335; H5 not supported). This means that, regardless of these individual differences, the way behavioral control mediates the link between economic motivation and the intention to formalize a business remains consistent across groups. In other words, the identified personal background factors did not meaningfully alter how economic drive translates into future entrepreneurial plans through perceived behavioral control (see

Figure 3 and

Table 5).

4.2. The Robust Mediating Mechanism: The Non-Significant Moderating Role of Personal Characteristics

The test of H5, which proposed that personal characteristics (educational qualification, business setup reason, and business age) moderate the mediated relationship, was not supported and thus rejected. The path coefficients for these specific interaction effects were statistically insignificant (e.g., Education × Behavioral Control × Future Intention: β = 0.012,

p = 0.750; Business Age × Behavioral Control: β = 0.032,

p = 0.335). This finding is theoretically significant. It indicates that the core psychological mechanism of the model, whereby behavioral control mediates the effect of economic motivation on formalization intention, is remarkably robust. The process holds true regardless of an entrepreneur’s level of education, their reason for starting the business, or the business’s age. This challenges a common assumption in entrepreneurship research that such demographic and experiential factors are primary determinants of behavioral outcomes (e.g.,

C. D. Duong, 2021). Instead, our results suggest that the perception of control is a universal driver. While education or experience may contribute to forming one’s behavioral control, they do not, in themselves, alter the fundamental function of this control as the critical mediator. This insight greatly enhances the generalizability and potential impact of our model, suggesting that interventions aimed at boosting behavioral control can be effectively applied across a highly diverse population of informal entrepreneurs.

5. Discussion

This research aimed to elucidate the psychological determinants of formalization among informal entrepreneurs in Nigeria, developing and evaluating a mediation model based on the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB). The results validate the concept, elucidating a complex story about the formation of intents. The analysis produced several pivotal findings: a substantial positive correlation between economic motivation and future intention (H1), a robust direct influence of behavioral control on intention (H3), and, most importantly, the validation of behavioral control as a significant mediator between economic motivation and intention (H4). Conversely, the control variables about personal traits exerted minimal influence on the model (H5). The next discourse analyzes these results by juxtaposing them with the existing literature.

The backing for H1 validates that economic incentive is a pertinent, if inadequate, catalyst for formalization purposes; yet its comparatively limited direct impact challenges a fundamental presumption within policy discussions (

International Labour Office, 2013;

Omri, 2020). This finding corroborates and expands upon the research conducted by

Williams and Shahid (

2016), which asserts that informal entrepreneurs function under a unique logical framework. The research enhances this debate by actually demonstrating that the economic arithmetic transcends a mere cost–benefit analysis, being significantly influenced by perceived risk. For the informal entrepreneur, the possible long-term benefits of formalization are evaluated against immediate and concrete risks: regulatory complications, less operational freedom, and heightened scrutiny. Consequently, the study’s results indicate that policies based only on financial incentives are tackling just one aspect of a multifaceted problem. To make the economic rewards seem both possible and less hazardous, this must be done together with attempts to minimize ambiguity in the process and develop trust. This corresponds with traditional entrepreneurial frameworks but contests their dominance in informal settings, reflecting

Williams and Shahid’s (

2016) claim that informal rationality favors immediate stability over ambiguous long-term benefits.

The primary contribution of this study is the empirical validation of behavioral control. This provides robust support for H3 and considerable mediation in H4, highlighting the essential function of behavioral control as the key psychological process that converts economic desire into intention. Although the significance of Perceived Behavioral Control (PBC) in general entrepreneurial intention is well-documented (

Ajzen, 1991;

Haddoud et al., 2024), its role within the particular framework of formalization remains inadequately understood. The research tackles this deficiency. The research expands the Theory of Planned Behavior by clarifying that in significant transitions such as formalization, perceived control functions not just as a direct precursor but as the critical mechanism via which economic aspirations are transformed into definitive intents. This was shown via the perspectives of informal entrepreneurs, using critical inquiries such as “Do I desire the economic advantages?” and, more essentially, “Do I believe I can effectively manage the formalization process and prosper subsequently?” This study refines the TPB model for high-stakes behavioral transitions, indicating that PBC serves as the crucial link, rendering motivation an unactivated potential in its absence. An informal entrepreneur must want the advantages of formality and have confidence in their abilities to get them. This offers a comprehensive elucidation of the enduring “motivation–intention gap” inside the informal sector.

This corresponds with recent research by

Cuong (

2024) and offers a comprehensive theoretical elucidation for the enduring “motivation–intention” gap seen in the informal sector. This process has a strong similarity in recent studies on gig employment. It illustrate that practical engagement with digital gig platforms enhances the entrepreneurial self-efficacy and resource networks of female entrepreneurs, thereby influencing their future entrepreneurial aspirations. This research posits that for informal entrepreneurship, the perceived possession of equivalent capabilities (e.g., skills, resources, knowledge) encapsulated by behavioral control enables informal entrepreneurs to transform economic motive into a formalization strategy. Both settings underscore that experience mastery and the consequent self-efficacy are essential prerequisites to entrepreneurial activity.

An unexpected yet revealing discovery was that personal attributes (education, business age, start-up reason) for H5 testing indicated that personal characteristics, such as education and business age, did not significantly modify the fundamental mediation model of the psychological mechanism identified. This contradicts research that emphasizes demographics as key differentiators (e.g.,

C. D. Duong, 2021) and instead underscores the universal and significant influence of perceived skill. This does not make these things unimportant; it only means that their effects are probably felt via behavioral control. For example, the advantage of schooling may be actualized alone if it concretely bolsters an entrepreneur’s confidence in navigating official processes. This discovery has significant practical consequences as it endorses treatments that may be effectively directed towards individuals exhibiting poor levels of behavioral control, rather than being exclusively customized for certain demographic profiles. Empowerment measures that concentrate on enhancing skills and streamlining processes are expected to be successful across the varied informal sector, making policy interventions both more scalable and more equal. For clarity’s sake, this insight is powerful for policymakers. It suggests that interventions aimed at boosting perceived control, like easier registration processes, targeted training, and mentorship, can work well across a wide range of informal sectors, making them more scalable and fairer.

6. Conclusions

This research posits that the move from informal to formal entrepreneurship is a significant behavioral transformation, primarily influenced by psychological empowerment rather than only by economic considerations. By substantiating a paradigm in which behavioral control mediates the impact of economic incentive, it offers a more refined and effective framework for comprehension and promotes this transformation. Additionally, the research expands the Theory of Planned Behavior to the realm of entrepreneurial transition, positing and evidencing that Perceived Behavioral Control functions as the essential mediating variable between motivation and intention. This study offers two primary theoretical contributions. First, it effectively expands the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) into the realm of entrepreneurial transition, transcending its conventional focus on intentions to start a firm. Second, and more significantly, it theorizes and substantiates a mediation model, establishing behavioral control as the essential psychological process that elucidates the conversion of economic incentive into formalization intention. This fills an important theoretical gap by giving us a better understanding of how decisions are made in the informal sector, which is more dynamic and process-oriented.

The research also presents a validated questionnaire for assessing formalization goals and their causes, serving as a resource for future investigations in other situations. The research was able to question the policy dogma of focusing financial incentives, presenting evidence for a paradigm change towards “empowerment-based formalization” that promotes skills, knowledge, and entrepreneurial agency. The research demonstrated a transition from isolated incentives to cohesive initiatives that streamline processes, enhance information accessibility, and cultivate business capabilities. In this light, programs must combine financial incentives with efforts to create capability. This includes making registration systems that are easy to use, setting up company development clinics that are easy to get to, and using successful, established entrepreneurs as mentors to help others feel more confident by showing them how to do things. Interventions should be included to directly improve behavioral control. This might include small consulting tasks, toolkits for understanding rules, and peer-support networks that act like the “ripple effect” of experience learning in gig economies to develop confidence. Additionally, this research indicates the need to create curriculum and mentoring initiatives specifically designed to address the literacy deficiencies of informal entrepreneurs, emphasizing legal, financial, and strategic competencies. To achieve this, it is essential to create a non-formal, practical curriculum that targets the unique literacy deficiencies of informal businesses, emphasizing legal compliance, financial management, and strategic planning. Universities may serve as impartial centers for mentoring and education. Researchers are encouraged to expand upon this model via longitudinal and cross-cultural studies, examining the function of institutional trust as a possible moderator. In conclusion, this research puts behavioral control at the core of the formalization process, presenting a more humane and successful approach to promoting sustainable economic growth.

5–9 years

10–14 years

15 years and above

survival

Employee

Others, please specify………….

SSCEOND/NCE

HND/BSc.MSc/MBA/M.Ed.

Others

No formal education